Dell Zero-Day Vulnerability: Hardcoded Credentials Exploited for 2 Years [2025]

It's one of those security stories that makes you wonder how nobody caught it sooner. A major vulnerability in Dell's Recover Point for Virtual Machines sat unpatched for almost two years, quietly being exploited by Chinese state-sponsored hackers while the company had no idea it was happening.

We're talking about hardcoded credentials. Not some complex zero-day exploit. Just credentials baked directly into the code—the cybersecurity equivalent of leaving your house keys under the doormat.

Here's what happened, why it matters, and what you need to do about it right now.

TL; DR

- The Vulnerability: Dell Recover Point versions before 6.0.3.1 HF1 contained hardcoded credentials allowing unauthenticated remote access

- Time Window: Exploited as a zero-day by Chinese group UNC6201 since mid-2024 (nearly 2 years undetected)

- The Threat: New Grimbolt backdoor deployed, plus "Ghost NICs" technique for lateral movement and persistence

- Impact Level: Critical severity—root-level access to underlying operating systems

- Your Action: Patch immediately to Recover Point 6.0.3.1 HF1 or later if you're running affected versions

- Bottom Line: This is a reminder that even enterprise vendors make embarrassing mistakes, and hackers are patient enough to exploit them for years

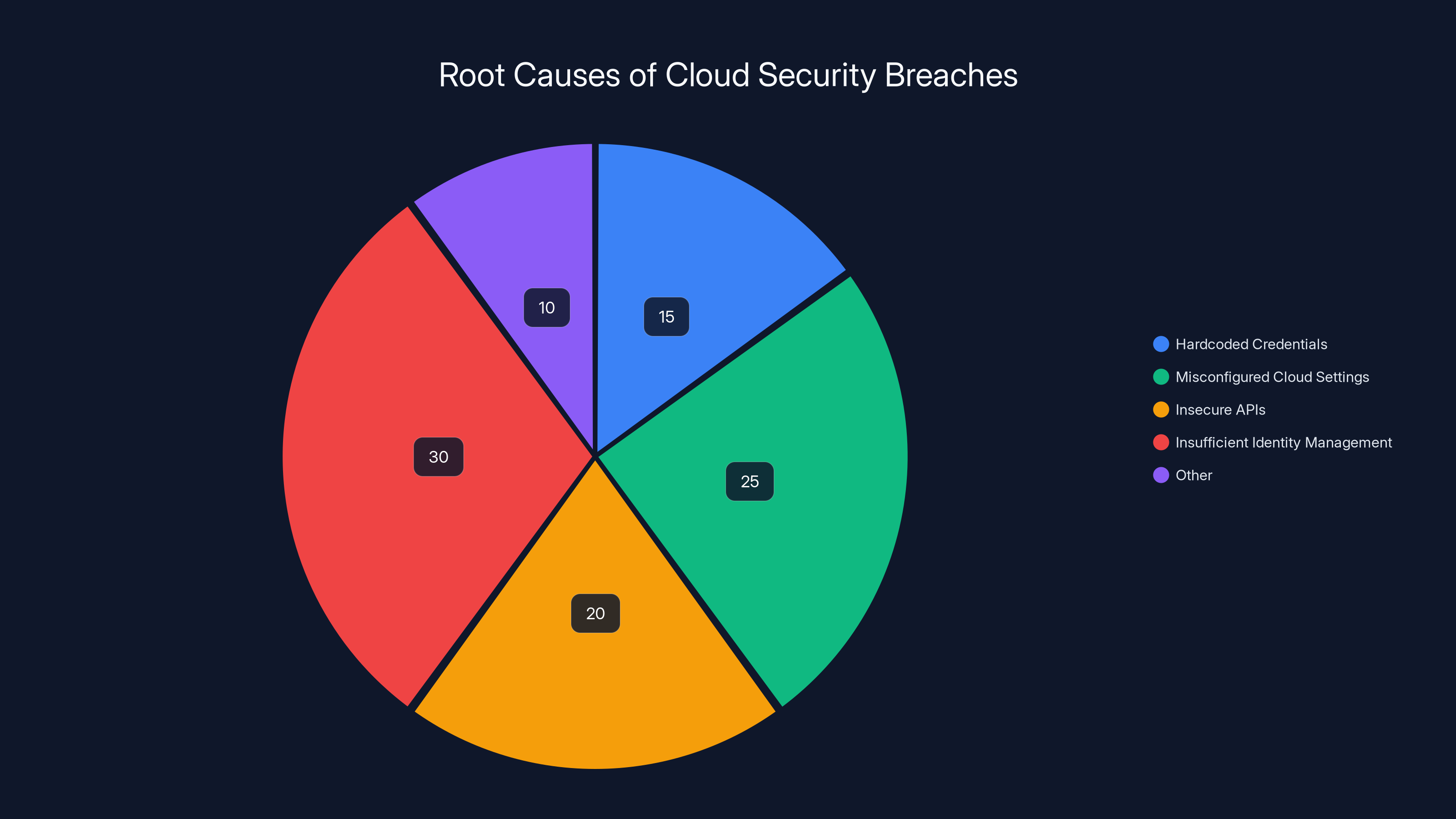

Hardcoded credentials account for 15% of cloud security breaches, highlighting the critical need for secure credential management.

The Basic Problem: Hardcoded Credentials in Production Code

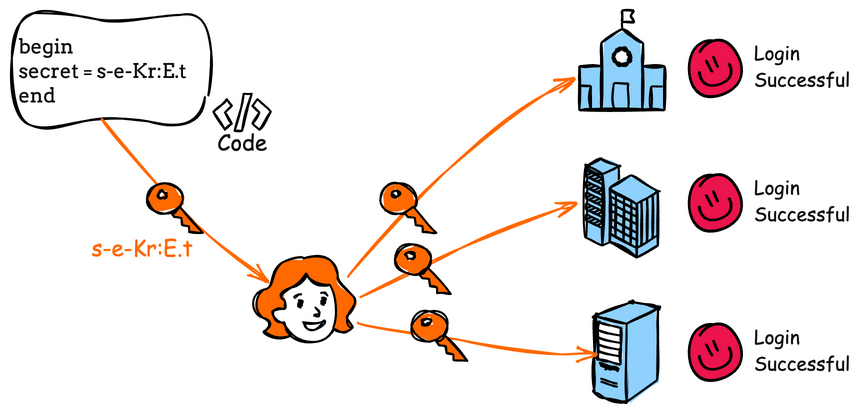

Let's start with the fundamental issue. Hardcoded credentials are one of the oldest, most well-known security mistakes in software development. Every security framework, every developer training program, every compliance standard warns against it.

And yet it happens constantly.

When you hardcode credentials—usernames, passwords, API keys, tokens—you're essentially printing your front door code on the back of the product box. Anyone with access to the binary, anyone running a simple string search, anyone with the patience to decompile the code can find it.

In Dell's case, the Recover Point for Virtual Machines product shipped with hardcoded credentials baked into the application itself. This wasn't a weak password. This wasn't poor default configuration. This was a credential that worked for anyone who knew to look for it, and worse, it granted elevated access to the underlying operating system.

The scariest part? This wasn't a recent mistake. This vulnerability existed in all versions prior to 6.0.3.1 HF1. That means potentially years of releases, each one shipping with the same hardcoded credentials.

Dell's vulnerability is catalogued as CVE-2024-50423. It has a CVSS score of 9.8 out of 10—that's critical territory. An unauthenticated remote attacker with nothing more than knowledge of the hardcoded credential could potentially:

- Gain unauthorized access to the system

- Achieve root-level persistence

- Deploy malware

- Establish backdoors

- Move laterally through your network

- Steal sensitive data

All of that from a single hardcoded string.

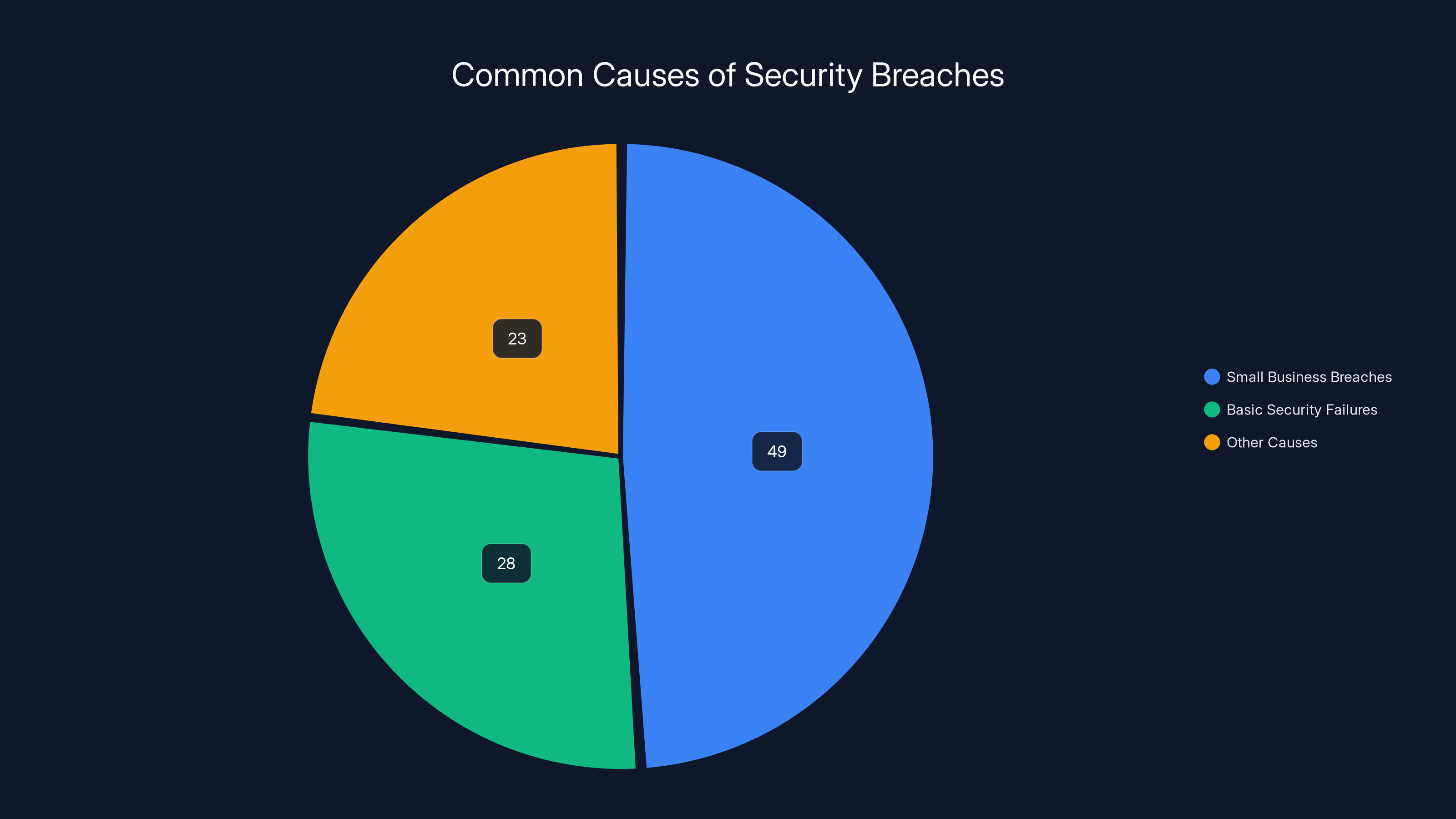

Nearly half of security breaches involved small businesses, with 28% due to basic security failures like default credentials or unpatched systems.

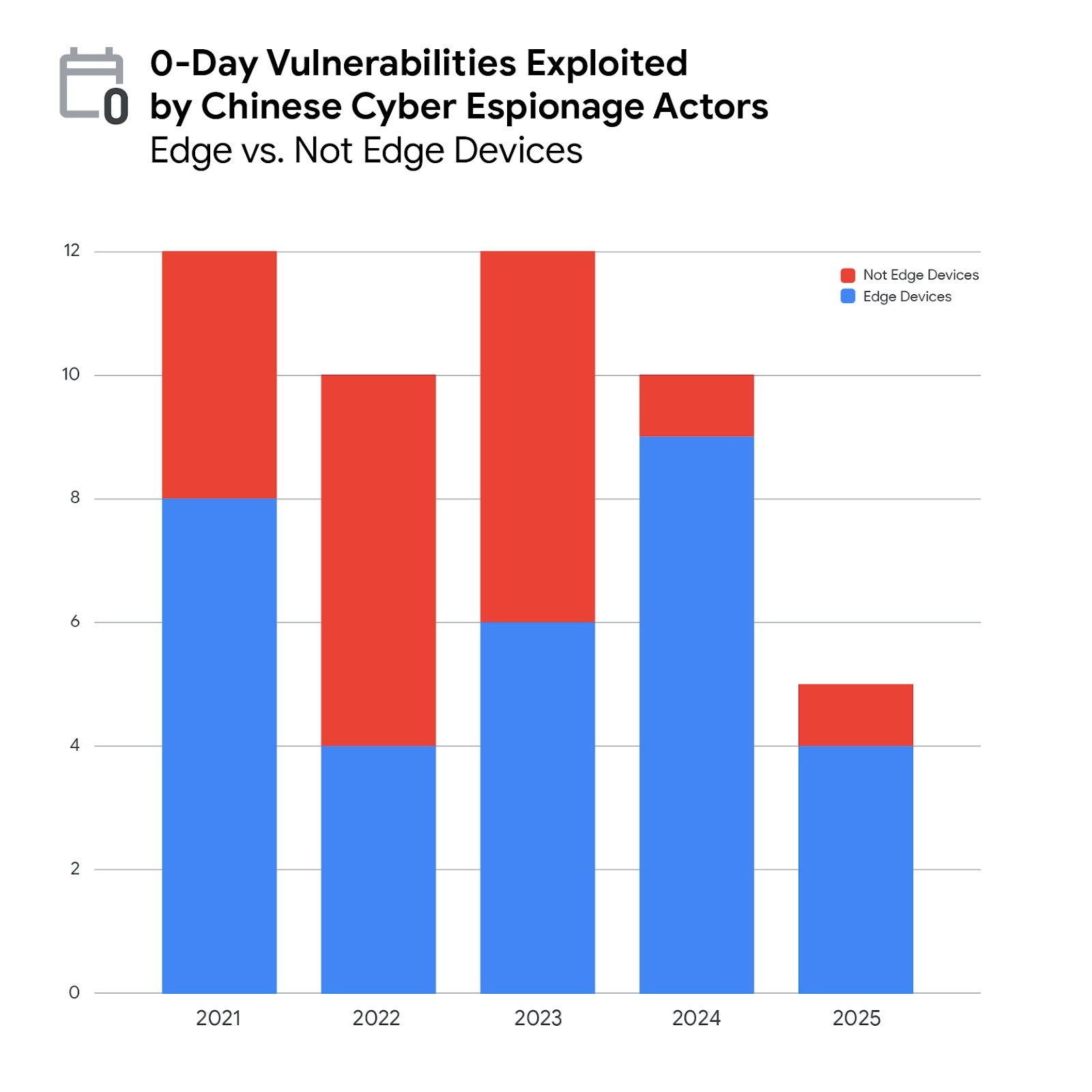

The Chinese State Hackers: UNC6201 and Why They Matter

Now here's where the story gets darker. It's not that this vulnerability existed. It's that someone was actively exploiting it for nearly two years before anyone noticed.

The group responsible is tracked as UNC6201. You might not have heard of them, unlike more famous threat actors like APT41 or Silk Typhoon, but that doesn't make them less dangerous. In fact, their low profile might be exactly why they were able to operate undetected for so long.

According to security researchers from Google and Mandiant, UNC6201 has been exploiting this vulnerability as a zero-day since mid-2024. That's not a typo. We're talking about continuous exploitation for more than a year and a half.

The researchers documented active exploitation, which means this wasn't theoretical. Real-world hacks. Real targets. Real persistence.

What makes UNC6201's campaign particularly noteworthy is the sophistication of their deployment. They didn't just gain access and move on. They deployed multiple malware payloads, including a previously unknown backdoor called Grimbolt.

Grimbolt was built in C#, using compilation techniques that made it faster and harder to reverse-engineer than UNC6201's previous tools. This suggests evolution. This suggests a team learning from their past work and improving their tradecraft.

They also deployed techniques for lateral movement and stealth that researchers had never documented before. Specifically, they used temporary virtual network ports—what security researchers call "Ghost NICs"—to pivot from compromised VMs into internal networks or SaaS environments.

That's not random. That's targeted. That's a group that understands virtualized infrastructure and knows exactly how to move through it.

What's particularly clever about UNC6201's approach is that they understand the gaps in security monitoring. Dell Recover Point instances often run in virtualized environments without traditional EDR deployed—not because organizations are careless, but because appliances typically run stripped-down operating systems with limited agent support.

UNC6201 exploits that gap.

The connection to earlier BRICKSTORM campaigns suggests this isn't a one-off group. They appear to be part of a larger ecosystem of Chinese state-sponsored threat actors, using similar techniques, targeting similar infrastructure, possibly even sharing intelligence.

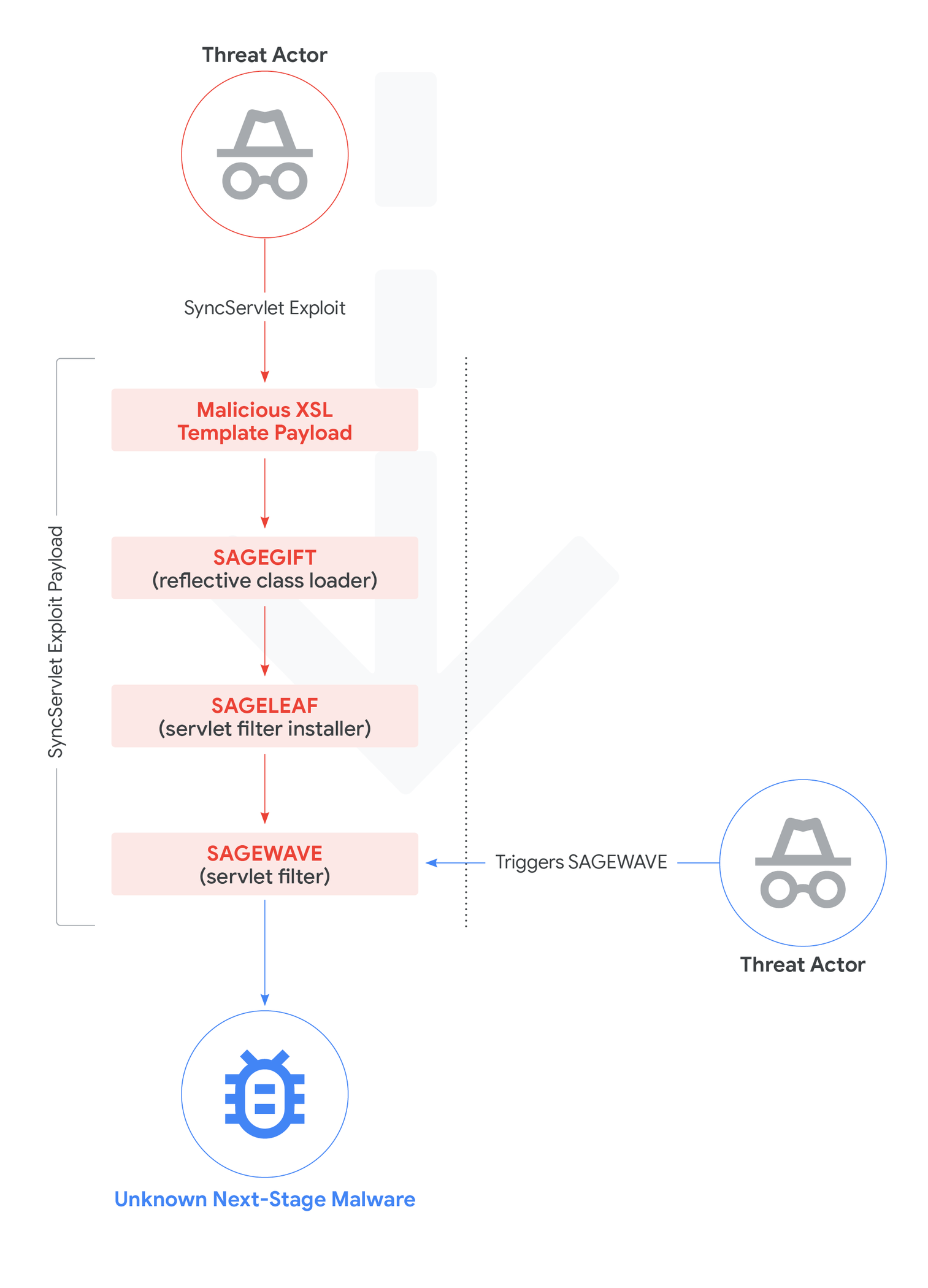

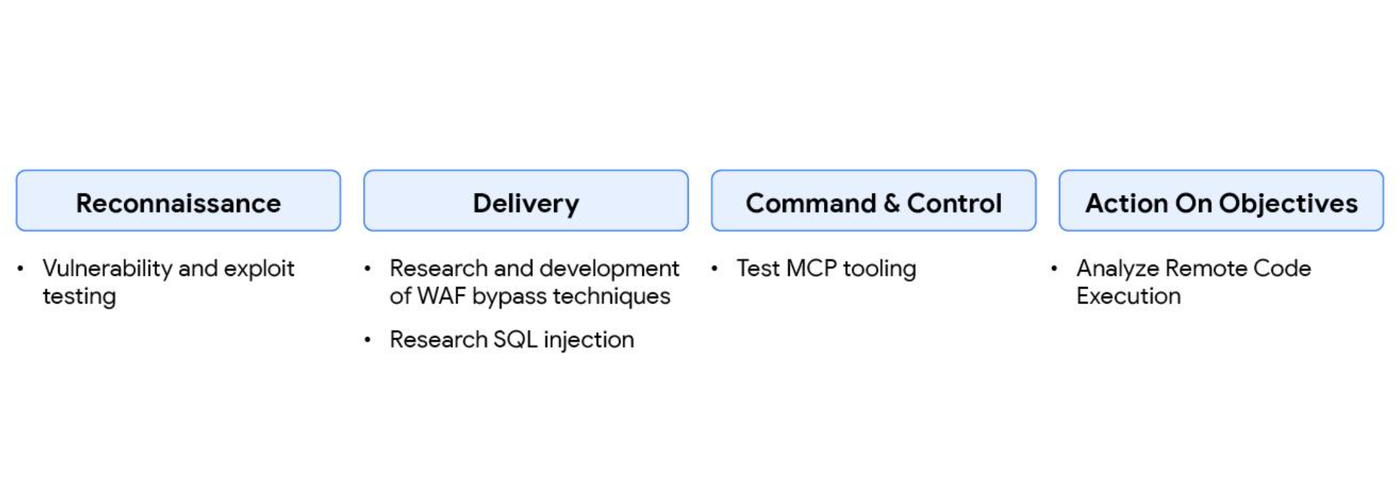

How the Attack Actually Works: The Technical Exploitation Chain

Understanding how this vulnerability gets exploited matters, because it helps you understand why it's so dangerous.

Step one: An attacker identifies a Dell Recover Point instance connected to the network. Recover Point is disaster recovery software, so it's often exposed to some degree of network access—it needs to communicate with other systems.

Step two: The attacker attempts to authenticate using the hardcoded credential. They don't need to guess it. They don't need to brute force it. The credential is literally embedded in the software. Anyone who has the software binary can extract it.

Step three: Authentication succeeds. The attacker now has valid credentials. They're inside.

Step four: Because these hardcoded credentials grant elevated privileges—potentially root-level access—the attacker can immediately begin installing backdoors, creating new accounts, modifying system configurations, or pivoting to other systems.

Step five: They deploy Grimbolt or other malware payloads. At this point, they've achieved persistence. Even if someone reboots the system, the malware survives.

Step six: They use Ghost NICs to move laterally. Virtual NICs are temporary network interfaces. They're often not monitored as closely as physical interfaces. By creating temporary virtual network ports, they can traffic data, communicate with command-and-control servers, or move between systems without triggering alerts.

The whole attack chain is terrifyingly simple. No exploit code needed. No vulnerability in the exploit itself. Just a credential sitting in the code, waiting to be found.

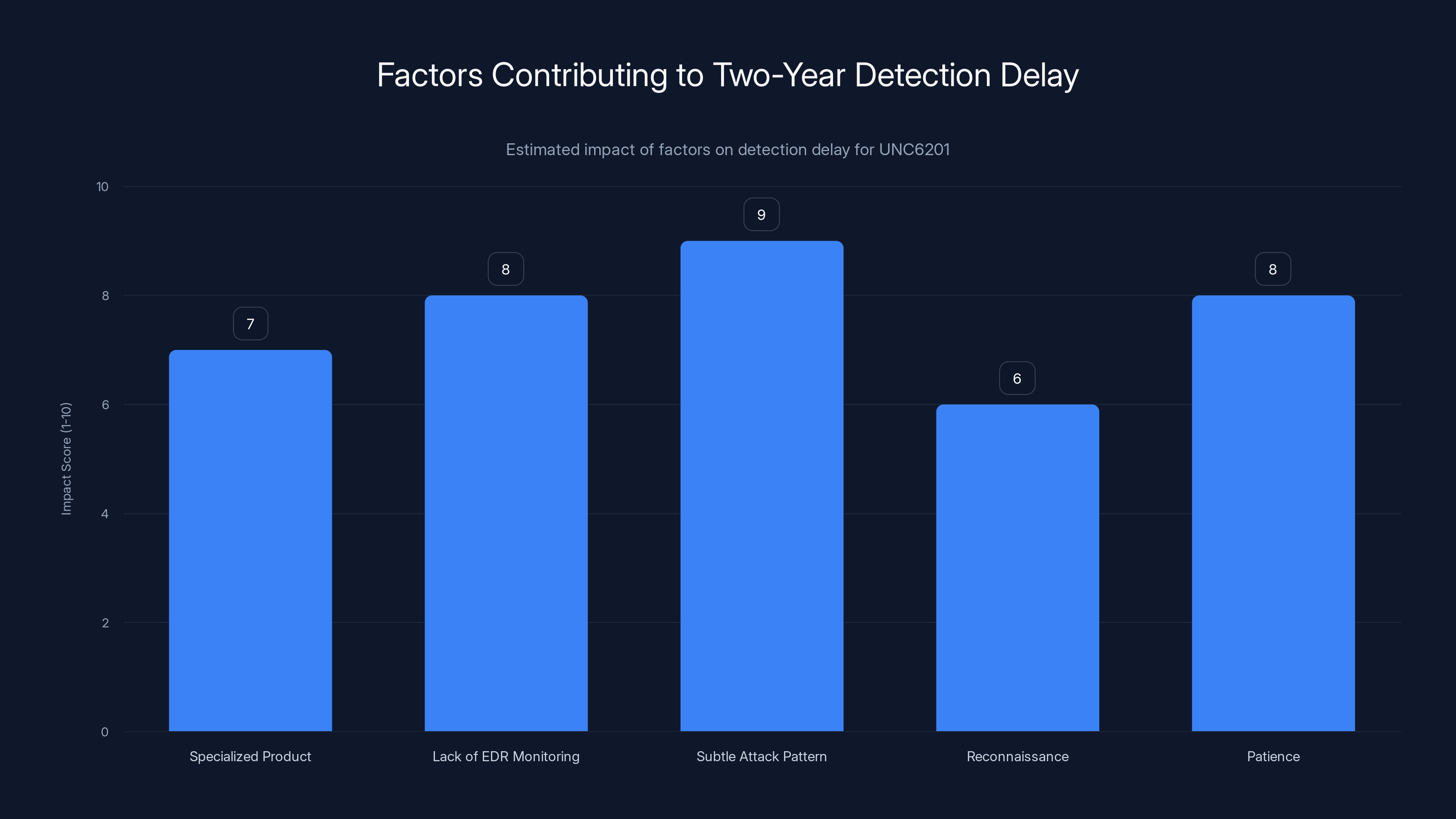

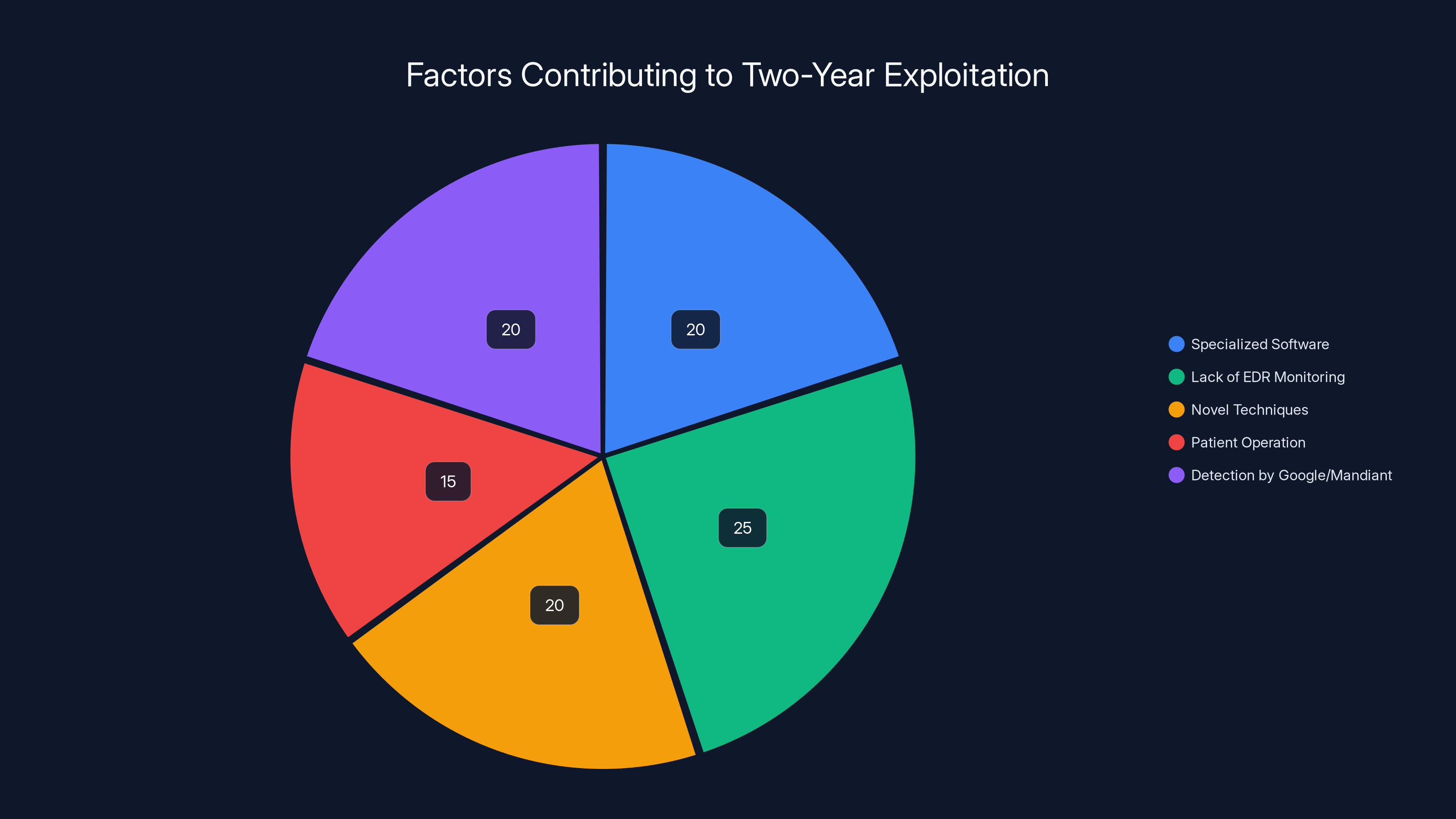

The subtle attack pattern and lack of EDR monitoring were the most significant factors contributing to the two-year detection delay of UNC6201. (Estimated data)

Why This Took Two Years to Detect

This is the question that keeps security professionals awake at night: How did this go undetected for two years?

There are several factors at play.

First, Recover Point is a specialized product. It's disaster recovery software used primarily by enterprises with significant infrastructure. It's not as widely deployed as, say, Windows or Exchange. That means there are fewer researchers poking at it, fewer security tools instrumenting it, fewer eyeballs on the code.

Second, UNC6201 specifically targeted instances that lacked EDR monitoring. Most EDR solutions aren't deployed on appliance-based recovery software. The OS is often minimal. The vendor doesn't support traditional agents. So the usual detection mechanisms don't apply.

Third, the attack pattern was subtle. Using temporary virtual NICs for lateral movement is clever because it doesn't leave the typical breadcrumb trails. Traditional network monitoring tools watch persistent network interfaces. Temporary ones fly under the radar.

Fourth, reconnaissance. UNC6201 didn't just blindly exploit everything. They researched their targets. They identified which systems had Recover Point. They verified the versions. They understood the network topology. They moved carefully.

Fifth, patience. Threat actors often have a longer timeline than defenders. They can afford to move slowly, avoid obvious patterns, and wait for the right moment to extract data or cause damage. A two-year campaign isn't rushed. It's patient.

Dell itself likely didn't discover this vulnerability through security research. It was probably reported to them by Google or Mandiant after those organizations detected the active exploitation and traced it back to the root cause.

That's both good and bad. Good because responsible disclosure means Dell had time to prepare a fix. Bad because it means a critical vulnerability in a major enterprise product was actively exploited in the wild before the vendor even knew it existed.

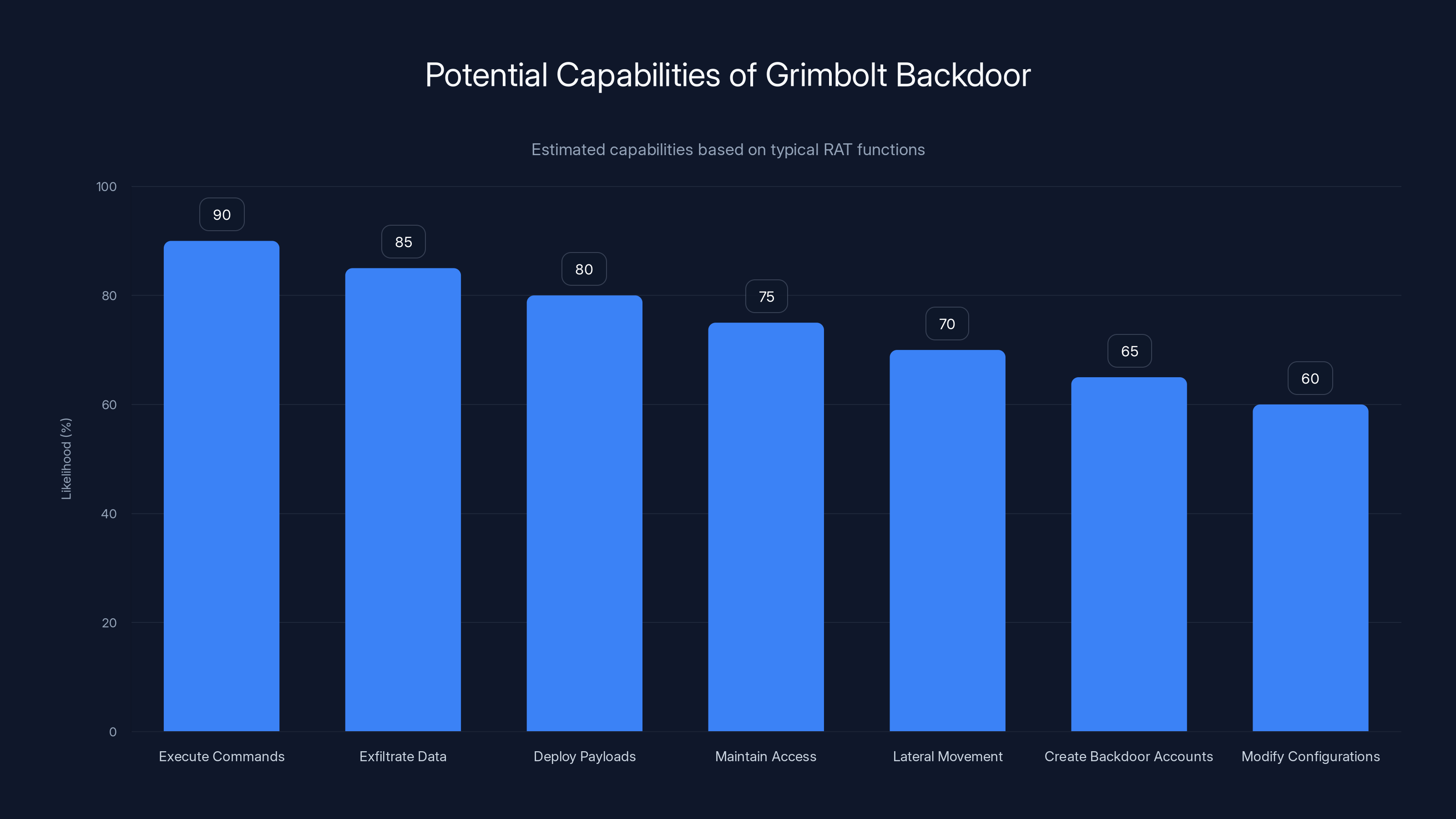

The Grimbolt Backdoor: A New Threat

While the hardcoded credential is the vulnerability, Grimbolt is the payload. Understanding what Grimbolt does helps you understand what UNC6201 was actually trying to accomplish on compromised systems.

Grimbolt is a previously unknown backdoor written in C#. This is significant for several reasons.

C# is a higher-level language than what's traditionally used for malware. It's easier to read, easier to modify, easier to compile on different platforms. That suggests the team building Grimbolt might be prioritizing flexibility and deployability over raw performance.

More importantly, the researchers noted that Grimbolt uses new compilation techniques that make it harder to reverse-engineer. This is an active arms race. Security researchers develop better tools for analyzing malware, so malware developers develop better tools for hiding themselves.

Grimbolt appears to be UNC6201's answer to that arms race.

While specifics about Grimbolt's capabilities haven't been widely published, based on the context of its deployment, it likely functions as a remote access tool (RAT). That means UNC6201 could:

- Execute arbitrary commands on the compromised system

- Exfiltrate data

- Deploy additional payloads

- Maintain persistent access even after system reboots

- Move laterally through the network

- Create backdoor accounts

- Modify system configurations

The fact that Grimbolt was purpose-built for this campaign suggests UNC6201 invested significant resources. They didn't just repurpose old malware. They built something new specifically for exploiting Dell Recover Point.

That's the marker of a sophisticated threat actor with funding, expertise, and long-term objectives.

Grimbolt likely has multiple capabilities typical of remote access tools, with high likelihood of executing commands and exfiltrating data. Estimated data based on typical RAT functionalities.

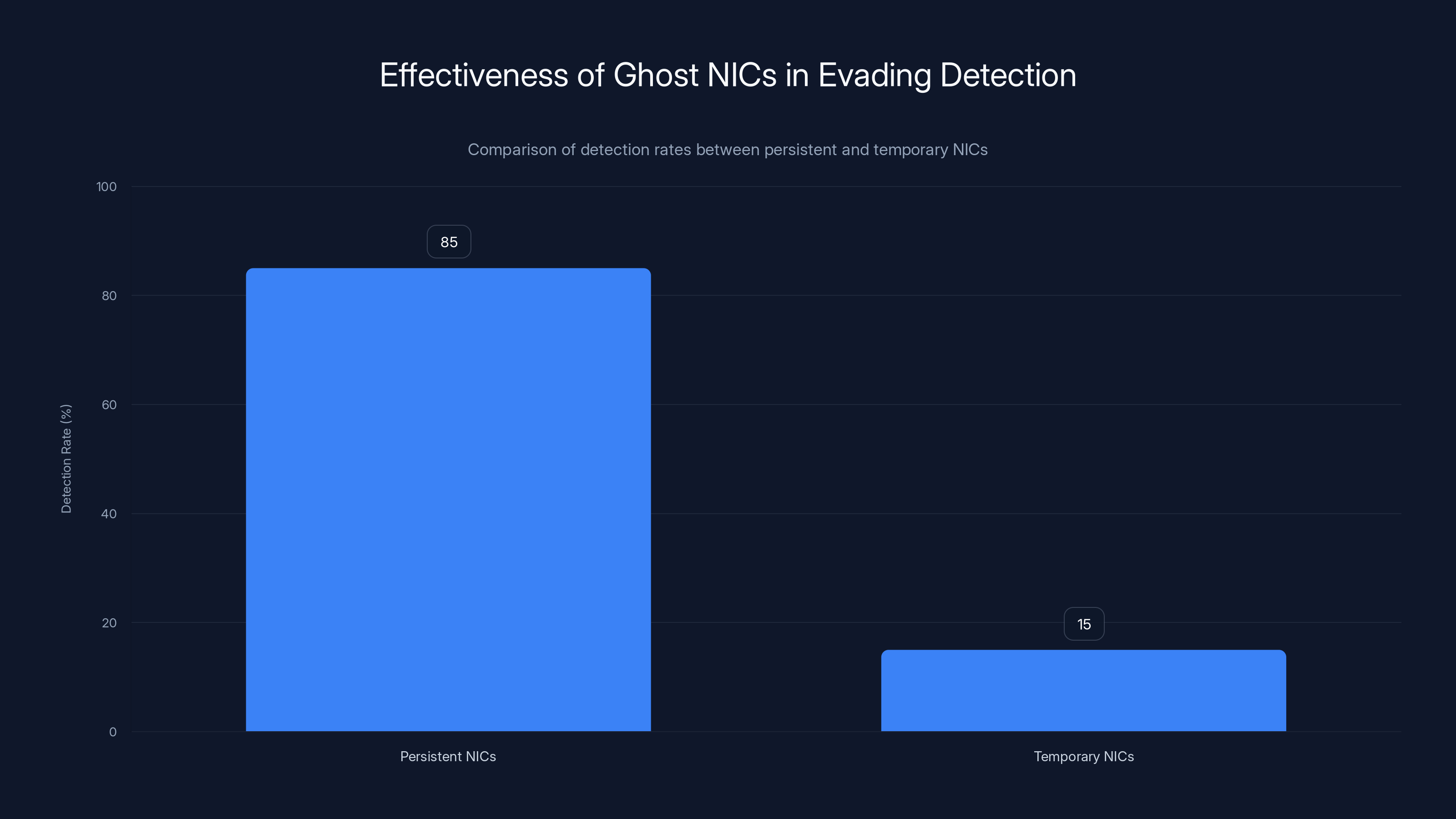

Ghost NICs: A Novel Lateral Movement Technique

One of the most interesting aspects of this campaign is the use of Ghost NICs—temporary virtual network interfaces for lateral movement.

This technique is worth understanding in detail because it reveals how sophisticated the attack chain is and why traditional network monitoring might miss it.

When you run a virtual machine, the guest operating system communicates with the physical network through virtual network adapters. These are software constructs that appear to the VM as network interfaces but are actually managed by the hypervisor.

Normally, network adapters are persistent. They're configured during system setup and remain active until an administrator changes the configuration. That makes them easy to monitor.

But virtual NICs can be created and destroyed on the fly. UNC6201 exploited this by creating temporary virtual network interfaces specifically to facilitate lateral movement between systems.

Here's how it works conceptually:

- Attacker gains initial access to VMs through the hardcoded credential

- Attacker deploys Grimbolt backdoor on those systems

- Using the backdoor, attacker creates a temporary virtual NIC

- Traffic flows through the temporary NIC to communicate with other systems or exfiltrate data

- The temporary NIC is destroyed, leaving minimal trace

- Detection tools that monitor persistent network interfaces don't see the temporary one

This is clever because it leverages the inherent characteristics of virtual infrastructure to hide malicious activity.

Most security monitoring focuses on persistent network interfaces because those are where normal traffic flows. Nobody expects legitimate traffic to use temporary, ephemeral network adapters. So when they do, it flies under the radar.

Researchers noted this was a technique they hadn't observed in previous UNC6201 investigations, which suggests it was either developed recently or previously used in other campaigns that haven't been publicly disclosed.

The fact that Mandiant highlighted it as novel says a lot. Mandiant investigates hundreds of breaches per year. For them to call something a new technique means it genuinely hasn't been widely documented or deployed before.

That means defenders need to be thinking about monitoring for this specifically. Traditional network monitoring isn't enough. You need tools that can detect creation of temporary virtual network interfaces, monitor ephemeral network connections, and alert on unusual network adapter activity.

The Discovery Process: How Google and Mandiant Found This

You might wonder how a two-year-old vulnerability finally got discovered. The answer involves sophisticated threat intelligence work.

Neither Google nor Mandiant randomly found this vulnerability by testing Dell Recover Point. Instead, they were conducting threat intelligence investigations into UNC6201's broader activities. As they traced attack patterns, gathered forensic evidence, and analyzed indicators of compromise, they eventually discovered that the common thread was exploitation of this specific Dell vulnerability.

Once they had that insight, they reverse-engineered the exploitation method and identified the root cause: hardcoded credentials.

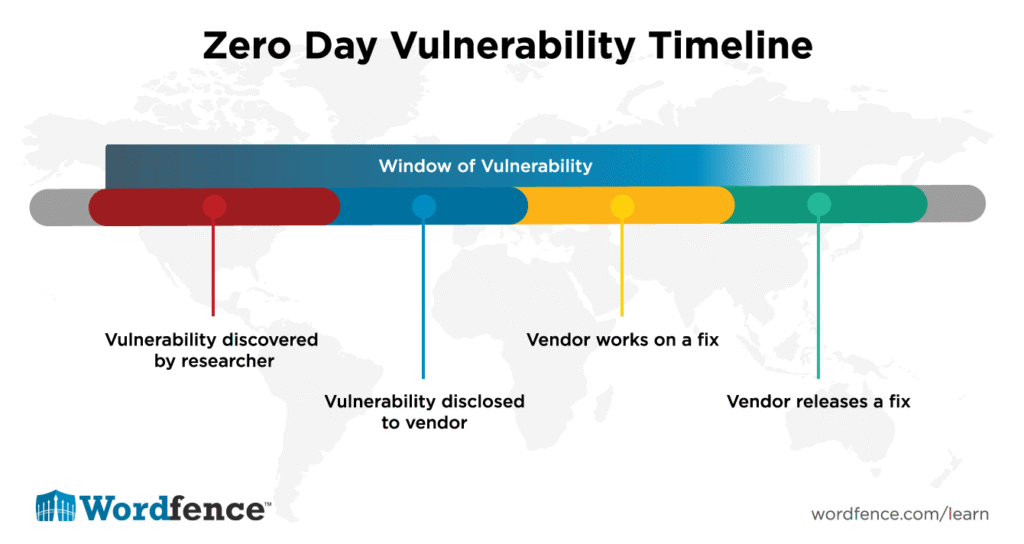

This is typical of how zero-days get discovered. It's rarely through random fuzzing or code review. It's through incident response. A breach gets detected, investigators trace the attack chain, and eventually they find the vulnerability the attacker was exploiting.

The timeline matters here. UNC6201 started exploiting this in mid-2024. Google and Mandiant detected it, investigated it, and reported it to Dell. Dell then worked on a patch. The patch was released, and the advisory was published.

The entire process from exploitation discovery to patch deployment probably took weeks or months. Meanwhile, the vulnerability was actively being exploited in the wild.

Ghost NICs significantly reduce detection rates compared to persistent NICs, making them an effective tool for evading network monitoring. Estimated data.

Why Hardcoded Credentials Keep Happening

The existence of hardcoded credentials in production code is baffling to anyone who's spent five minutes reading security best practices. Yet they keep appearing.

There are legitimate reasons why this happens, even in well-resourced organizations.

First, development velocity. When you're building software quickly, it's easier to hardcode a credential temporarily while you figure out proper credential management. Then you deploy to production, intending to fix it later, and it never happens.

Second, legacy code. Older software was often built before modern secrets management practices existed. That code might be running in production twenty years later, still containing credentials from the 1990s.

Third, configuration complexity. Proper secrets management requires infrastructure—key vaults, credential rotation, audit logging. Not all organizations have that infrastructure in place, especially for specialized appliances.

Fourth, developer behavior. Many developers don't fully internalize the risk of hardcoded credentials. They understand SQL injection. They understand buffer overflows. But a hardcoded password feels like a configuration issue, not a security issue. That mental model is wrong, but it's common.

Fifth, testing and debugging. During development, developers often need credentials to test functionality. Hardcoding them is quick and easy. Swapping them out before production is a step that gets forgotten.

For organizations managing affected systems, the lesson is clear: assume that any legacy appliance software might contain hardcoded credentials. This isn't just a Dell problem. This is an industry problem.

Assessing Your Risk: Do You Run Affected Versions?

If you're an organization running Dell Recover Point, here's what you need to know:

All versions prior to 6.0.3.1 HF1 are vulnerable. That's a broad statement that covers potentially hundreds of deployments.

Recover Point is typically deployed in enterprise environments where disaster recovery is critical. It's not a consumer product. If you work for a mid-sized or larger organization, there's a reasonable chance you're running it.

The exposure is real. The vulnerability was actively exploited. The attackers had specific targets and demonstrated significant sophistication.

Your risk assessment should include:

Network Exposure: Is your Recover Point instance accessible from the internet or from untrusted networks? The more exposed it is, the higher your risk. Ideally, Recover Point should only be accessible from trusted internal networks or through properly configured VPN access.

Detection Capabilities: Do you have monitoring in place to detect unusual access patterns or lateral movement from your Recover Point instances? If you don't, you wouldn't have detected this attack even if it happened to you.

Data Sensitivity: What data does your Recover Point protect? If it's handling sensitive information—financial records, customer data, intellectual property—the impact of a breach is higher.

Patch Feasibility: Can you upgrade to 6.0.3.1 HF1 or later without major downtime? Recover Point is critical infrastructure, so patching requires careful planning.

Historical Access Logs: Can you review logs to see if anyone accessed your Recover Point instances using unusual credentials or from unexpected locations? This would indicate if you were already compromised.

The two-year delay in discovering the hardcoded credential exploitation was due to a combination of factors, including the specialized nature of the software and the attacker's use of novel techniques. Estimated data.

Patching Strategy: How to Upgrade Safely

The fix is straightforward: upgrade to Recover Point 6.0.3.1 HF1 or later. Dell has published the patch, and it's available through normal channels.

But patching appliance software isn't always simple. Recover Point is a critical component of many disaster recovery strategies. Downtime during patching means your disaster recovery capability is offline.

Here's a reasonable patching strategy:

Step 1: Assess Your Environment Document which Recover Point versions you're running, how many instances you have, and what systems depend on them. This gives you a baseline to work from.

Step 2: Test in Non-Production If possible, test the patch in a lab environment first. Verify that functionality works as expected. Look for any compatibility issues with your backup systems or applications.

Step 3: Plan Downtime Determine when you can afford to take Recover Point offline. This is probably outside of business hours or during a scheduled maintenance window. Plan for the upgrade to take longer than expected—this is enterprise software.

Step 4: Backup Configuration Before patching, back up your Recover Point configuration. If something goes wrong, you want to be able to recover your settings without rebuilding from scratch.

Step 5: Execute Patch Follow Dell's patch instructions precisely. Don't skip steps. Test functionality after patching.

Step 6: Verify and Monitor After patching, verify that Recover Point is functioning normally. Monitor logs for any errors. Watch for unusual activity in the weeks following patching.

Step 7: Conduct Forensics (If Indicated) If you suspect you may have been compromised before patching, conduct a forensic investigation. Look for signs of Grimbolt, evidence of Ghost NICs, or other indicators of compromise.

Detecting Prior Compromise: Forensic Indicators

Patching fixes the vulnerability, but it doesn't necessarily reveal if you were already compromised.

If UNC6201 or another threat actor exploited this vulnerability on your systems, they likely deployed malware, created backdoor accounts, or established persistence mechanisms.

Looking for evidence of compromise should include:

Account Anomalies: Review user accounts on your Recover Point instances. Look for unexpected accounts that might have been created by attackers. Check when they were created and what permissions they have.

File System Changes: Compare the current file system against known good baselines if you have them. Look for unexpected files, especially in system directories or startup locations.

Process Analysis: Review running processes and startup scripts for anything unusual. Grimbolt would need to run as a process, and it would need to start automatically after reboots.

Network Connections: Check logs for outbound connections to unfamiliar IP addresses. UNC6201 would need command-and-control communication. Look for patterns of data exfiltration.

System Logs: Review security logs, application logs, and syslog for evidence of unusual activity. Failed authentication attempts followed by successful access might indicate exploitation.

Memory Analysis: If you can take systems offline, perform memory forensics. Malware in memory might not be detected by file system scans.

Virtual Network Adapters: Look for temporary or unusual virtual network adapters. Document when they were created and what traffic flowed through them.

This forensic work is complex. If you suspect compromise but lack in-house expertise, this is a situation where hiring incident response specialists is justified.

Broader Security Implications: What This Tells Us

This vulnerability isn't just about Dell or Recover Point. It reveals several important patterns in the broader security landscape.

First, Appliance Software Is Often Overlooked Appliances—specialized pieces of infrastructure like backup systems, firewalls, load balancers—often get less security scrutiny than traditional server or client software. They're assumed to be secure because they're from enterprise vendors. This vulnerability demonstrates that assumption is dangerous.

Second, State-Sponsored Actors Play the Long Game UNC6201's two-year campaign shows that threat actors with government backing don't need to rush. They have patience. They can maintain access quietly, gather intelligence, and wait for the right moment to act. This means your threat model needs to account for attackers who think in terms of years, not days.

Third, Detection Gaps Are a Reality This vulnerability was actively exploited for two years without detection. That should humble every organization. No matter how good your security is, there are probably gaps. The goal is to shrink those gaps, not to eliminate them entirely.

Fourth, Novel Techniques Keep Emerging Ghost NICs were new to researchers at Mandiant. That means threat actors are continuously innovating, adapting to defensive measures, and developing new techniques. Your security posture needs to account for threats that haven't been publicly documented yet.

Fifth, Open Communication About Vulnerabilities Matters Google and Mandiant discovered this vulnerability through threat intelligence work and responsibly disclosed it to Dell. Dell worked on a patch. The vulnerability was published with guidance. This process, while imperfect, is important. It beats the alternative: attackers quietly exploiting vulnerabilities for years while organizations remain in the dark.

Broader Recommendations for Appliance Security

Beyond just patching Dell Recover Point, there are broader lessons for how organizations should approach appliance security.

Inventory Everything You can't secure what you don't know about. Many organizations have old appliances running somewhere in the data center that nobody remembers who manages. Start with a complete inventory of all appliance-type software.

Monitor Aggressively Appliances without EDR still generate logs. Monitor those logs. Watch for unexpected authentication, unusual network patterns, and suspicious processes. Use SIEM tools to correlate events across appliances.

Assume Minimal Patching Appliance vendors often move slowly on patches because they need to maintain backward compatibility and stability. Assume you won't get patched as quickly as you'd like. Design your network assuming older versions will be running.

Segment Networks Don't let appliances have unfettered access to your entire network. Use network segmentation to limit what an appliance can reach even if it's compromised. If Recover Point is compromised, it shouldn't be able to directly access your active directory servers or financial systems.

Require Strong Authentication Hardcoded credentials in code is bad, but weak default credentials are almost as bad. Require strong authentication for accessing appliances. Use multi-factor authentication where possible.

Regular Security Assessments Bring in external security firms to assess your appliance security periodically. They might find issues that internal teams would miss.

What Dell Should Have Done Differently

It's worth examining what Dell's process failures were, because understanding them helps you avoid similar issues.

Code Review: The most obvious failure is that code review didn't catch the hardcoded credential. Even basic code review processes would flag this. Either Dell didn't have code review, or the review was insufficient, or reviewers weren't trained to look for hardcoded credentials.

Security Testing: Specialized security testing tools can detect hardcoded credentials automatically. If Dell had run such tools during development, this would have been caught before release.

Credential Rotation: Even if credentials had been hardcoded initially, a proper credential rotation process would have required changing them before release. It's possible the credentials in the shipping version were changed at some point, but clearly something in the process failed.

Penetration Testing: External security testers should have found this immediately. The vulnerability is trivial to exploit once you know what you're looking for. If Dell wasn't conducting regular penetration testing of Recover Point, that's a process failure.

Inventory of Hardcoded Values: A simple static analysis tool comparing current code to a registry of known hard-coded values would flag this. This is basic security tooling.

The fact that this got through all those gates suggests either a significant process breakdown or insufficient prioritization of security in the development process.

The Incident Response Lessons

For organizations that were affected by this vulnerability, the incident response process likely looked something like this:

Detection: Google and Mandiant detected UNC6201's activity through threat intelligence work. Organizations affected probably never detected it themselves—they were notified by Dell after the advisory was published.

Containment: Once the vulnerability was publicly known, organizations needed to urgently patch or isolate affected systems. Organizations without rapid patch deployment processes probably had to take systems offline.

Eradication: If compromise was suspected, organizations needed to investigate their systems for signs of Grimbolt or other malware. This required forensic expertise.

Recovery: After eradicating malware, systems needed to be verified as clean before bringing them back into production.

Post-Incident Analysis: Organizations should have reviewed how this happened—how did UNC6201 gain access? What would have detected them? What additional security controls are needed?

This incident response cycle takes time, resources, and expertise. It's expensive. And it's preventable with proper patching and monitoring.

Looking Forward: Future Threats and Proactive Defense

This vulnerability is specific to Dell Recover Point, but the patterns it reveals are universal.

Expect more vulnerabilities like this. As organizations shift infrastructure to clouds and virtualization, the attack surface expands. Appliances and specialized software become more common, not less. The opportunity for hardcoded credentials, configuration errors, and logic bugs increases.

Threat actors will continue exploiting these for as long as they remain exploitable.

Proactive defense means:

1. Assume Compromise: Design your security posture assuming that some systems are already compromised. Use network segmentation, monitoring, and detection to limit damage.

2. Continuous Patching: Make patching a routine process, not an emergency response. The faster you can deploy patches, the smaller the window of exploitation.

3. Threat Intelligence: Subscribe to threat intelligence feeds that track vulnerabilities and exploits relevant to your infrastructure. Know about threats before they affect you.

4. Incident Response Readiness: Have an incident response process in place. Know who to call when something goes wrong. Have forensic expertise available either internally or through retained contractors.

5. Security Culture: Build security into how your organization thinks about software and infrastructure, not as an afterthought. This includes architecture decisions, design reviews, code review, testing, and operational monitoring.

FAQ

What exactly is a hardcoded credential?

A hardcoded credential is a username, password, API key, or other authentication token that's embedded directly in source code or compiled binaries. Rather than being stored securely in a configuration file or secrets management system, the credential is literally written into the code. This means anyone with access to the code—through reverse engineering, binary analysis, or source code access—can extract the credential. Hardcoded credentials are one of the most dangerous security anti-patterns because they can't be rotated without rebuilding and redeploying the software.

How did the attacker use the hardcoded credential?

Once UNC6201 obtained a copy of the Dell Recover Point software, they reverse-engineered or decompiled it to extract the hardcoded credentials. They then used these credentials to authenticate to Recover Point instances exposed on their target networks. Since the credentials were embedded in the software distributed to all customers, they worked on every instance. The attacker gained immediate access without needing to exploit any additional vulnerabilities or guess passwords.

Why did this take two years to discover?

Several factors contributed to the two-year exploitation window. First, Recover Point is specialized disaster recovery software used primarily in enterprise environments, so there are fewer researchers examining it. Second, UNC6201 specifically targeted instances without EDR monitoring, reducing the likelihood of detection through security tools. Third, they used novel techniques like Ghost NICs that didn't leave obvious traces in traditional network monitoring. Fourth, they operated patiently and carefully, avoiding obvious patterns that might trigger alerts. Finally, the vulnerability was likely only discovered when Google and Mandiant detected UNC6201's activity and traced it back to the root cause.

What is Grimbolt and how dangerous is it?

Grimbolt is a previously unknown remote access trojan (RAT) written in C# that UNC6201 deployed on compromised Recover Point instances. RATs allow attackers to execute arbitrary commands on compromised systems, exfiltrate data, deploy additional malware, establish persistent access, and move laterally through networks. The fact that Grimbolt was purpose-built using new compilation techniques suggests it was specifically designed to evade reverse engineering and security analysis. The presence of Grimbolt on a system indicates deep compromise and the need for comprehensive incident response.

What are Ghost NICs and why are they a problem?

Ghost NICs are temporary virtual network interfaces created by attackers on virtual machines. Unlike normal network adapters that persist and can be monitored, Ghost NICs are ephemeral—they're created, used to traffic data or communicate with command-and-control servers, and then destroyed. This technique is effective at evading detection because traditional network monitoring focuses on persistent network adapters. It's particularly dangerous in virtualized environments where lateral movement between VMs is possible. Detecting Ghost NICs requires specialized monitoring that most organizations don't have in place.

Do I need to patch if I don't run Dell Recover Point?

If you don't use Dell Recover Point, this specific vulnerability doesn't directly affect you. However, the patterns in this vulnerability apply broadly. Other appliance software likely contains similar hardcoded credentials or other critical vulnerabilities. You should assume that any appliance-based software in your environment might contain similar issues and should be monitored, segmented, and patched aggressively. Additionally, if you use other Dell products, it's worth checking whether they contain similar hardcoded credential issues.

How can I detect if my Recover Point instance was compromised?

Detecting prior compromise requires examining multiple indicators: reviewing user accounts for unexpected ones that may have been created by attackers, searching the file system for malware files or modifications, checking process lists for suspicious activities, reviewing network logs for unusual outbound connections or data exfiltration patterns, examining system logs for evidence of failed authentication followed by successful access, analyzing virtual network adapters for temporary ones that shouldn't exist, and potentially conducting memory forensics. This is complex work that often requires specialized incident response expertise. If you suspect compromise, engage a professional incident response firm.

What should I do if I discover Grimbolt on my system?

If you discover evidence of Grimbolt or other malware on your Recover Point instance, immediately isolate the system from your network to prevent further lateral movement. Do not reboot unless necessary, as rebooting can destroy forensic evidence. Engage incident response specialists to conduct a thorough investigation of what the malware accessed, how long it was present, and whether it spread to other systems. Consider all data handled by that system compromised until you can verify otherwise. Rebuild the system from clean media after forensics are complete. Review backup systems—if this compromised system accessed your backups, they may also be compromised.

Will patching remove malware if I was already compromised?

No. Patching the operating system vulnerability simply closes the door that the attacker used to get in. It doesn't remove any malware already deployed, doesn't close backdoor accounts, and doesn't undo any system modifications made by the attacker. If your system was compromised before patching, you need to detect and remove the malware separately through incident response processes. This is why forensic investigation after patching is critical—you need to know whether you were compromised while the vulnerability was exploitable.

What's the best way to secure my Recover Point instances?

A comprehensive approach includes: ensuring Recover Point is not exposed to untrusted networks, using network segmentation to limit what compromised Recover Point could access, implementing strong authentication (including multi-factor authentication if possible), deploying monitoring and logging that tracks access and network connections, maintaining regular backups separate from Recover Point itself, conducting regular security assessments, and keeping the software patched promptly. Most importantly, assume that any appliance in your environment might be compromised at some point and design your security to limit the damage it could cause rather than relying entirely on preventing compromise.

Summary: The Key Takeaways

The Dell Recover Point vulnerability is a stark reminder of how fundamental security mistakes can persist in production systems for years while being actively exploited. Hardcoded credentials are preventable, yet they continue to appear in enterprise software. Sophisticated threat actors are patient, targeting specific infrastructure and moving carefully to avoid detection.

The good news is that fixes exist. Patching to version 6.0.3.1 HF1 or later closes the initial vulnerability. Network segmentation, monitoring, and incident response capabilities reduce the impact if you were compromised.

The harder truth is that this vulnerability is symptomatic of broader issues in how appliance software is developed, secured, and maintained. Organizations need to assume that similar vulnerabilities exist in their current infrastructure and should be actively searching for and remediating them.

For immediate action: check your Recover Point versions, patch if you're vulnerable, and monitor for signs of compromise. For longer-term strategy: reassess how you approach appliance security across your entire infrastructure.

Security isn't about preventing every breach. It's about assuming breaches will happen and being prepared to detect and respond to them quickly. This vulnerability, unfortunate as it is, is an opportunity to strengthen your security posture.

Key Takeaways

- Dell RecoverPoint versions before 6.0.3.1 HF1 contained hardcoded credentials allowing unauthenticated root access (CVSS 9.8 critical)

- Chinese state-sponsored group UNC6201 exploited this zero-day for two years starting in mid-2024 before detection

- Attackers deployed new Grimbolt backdoor and used novel Ghost NICs technique for lateral movement and stealth

- Hardcoded credentials are preventable through code review, security testing, and proper secrets management practices

- Organizations need aggressive monitoring, network segmentation, and incident response readiness to detect and contain such threats

Related Articles

- TP-Link Texas Lawsuit: Chinese Hackers, Security Lies, and What It Means [2025]

- Japanese Hotel Chain Hit by Ransomware: What You Need to Know [2025]

- YouTube Outage February 2025: Complete Timeline & What Went Wrong [2025]

- Netgear Nighthawk M7 5G Router Review [2025]

- Machine Credentials: The Ransomware Playbook Gap [2025]

- X Platform Outage: What Happened, Why It Matters, and How to Stay Connected [2025]

![Dell Zero-Day Vulnerability: Hardcoded Credentials Exploited for 2 Years [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/dell-zero-day-vulnerability-hardcoded-credentials-exploited-/image-1-1771425494019.jpg)