Machine Credentials: The Ransomware Playbook Gap [2025]

Here's an uncomfortable truth that security teams are just starting to face: your ransomware playbook is probably missing something critical. Not because you're unprepared. Not because your team isn't trying. But because the industry's most authoritative framework—the one your team likely references when building incident response procedures—has a massive blind spot.

That blind spot is machine identities.

And attackers know about it.

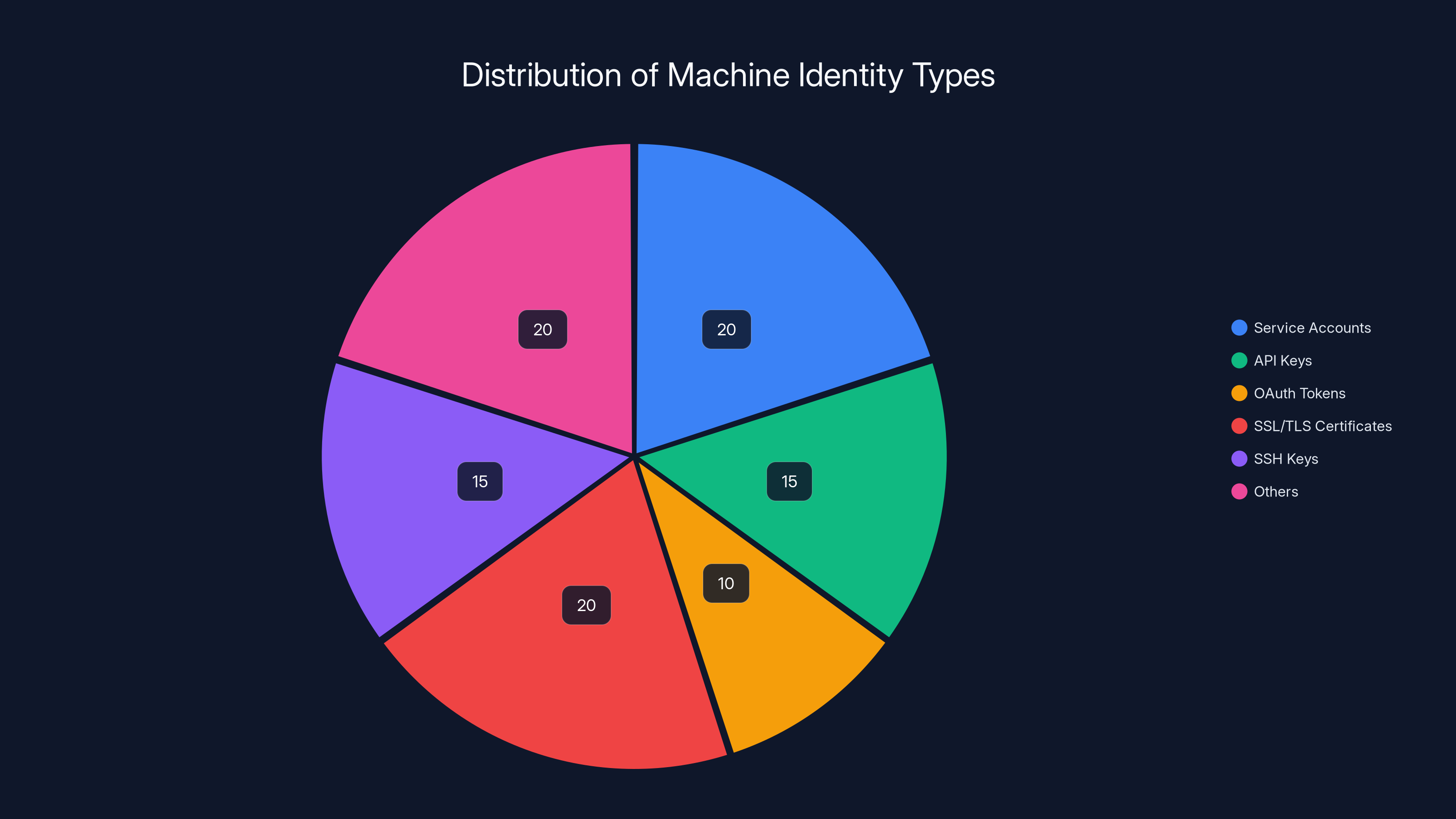

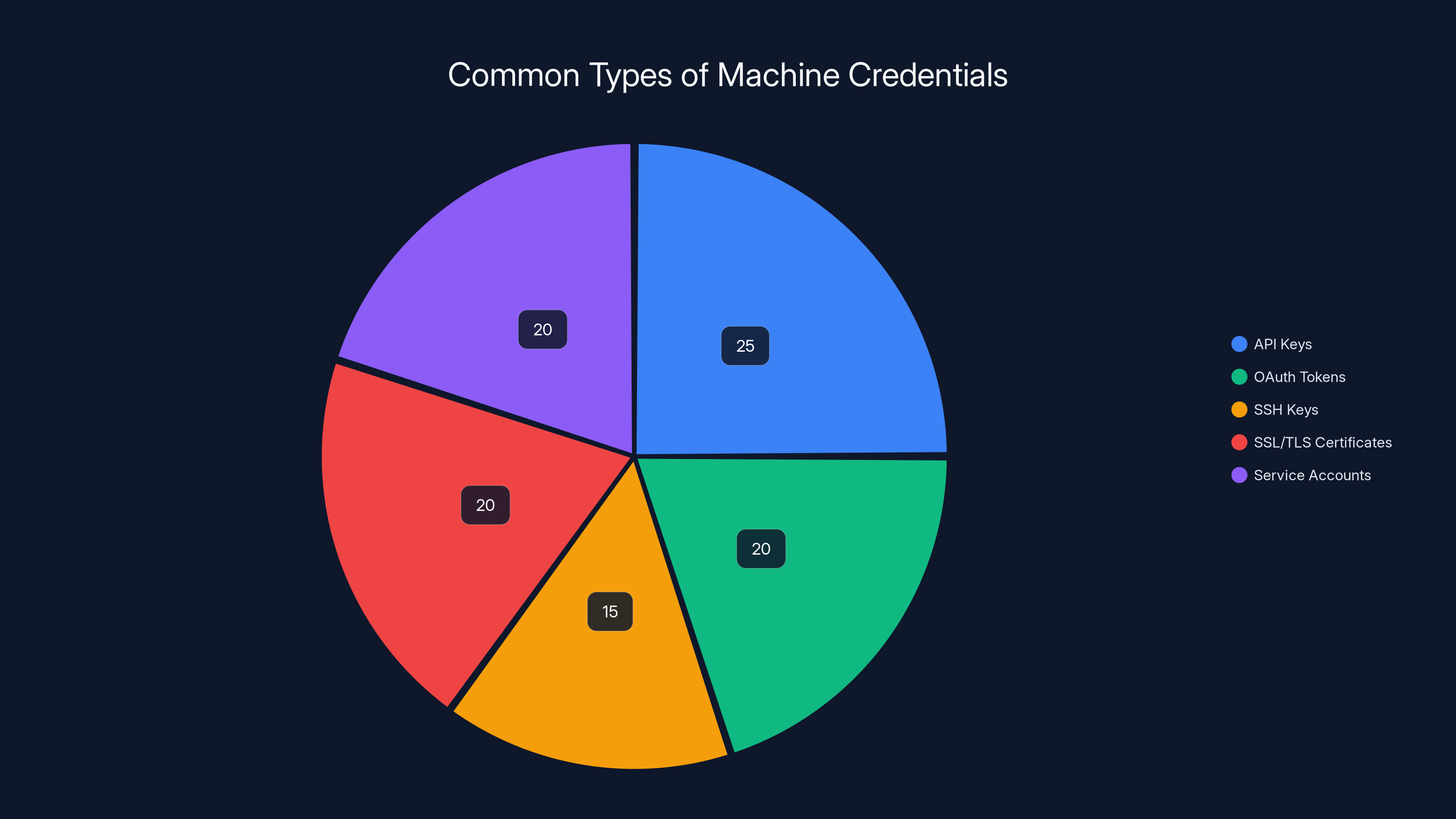

The numbers are staggering. For every human user in your organization, there are 82 machine identities floating around—service accounts, API keys, tokens, certificates, webhooks, and countless other non-human credentials that run the systems keeping your business alive. Forty-two percent of those machine identities have privileged or sensitive access. Yet when you look at the industry's most cited ransomware preparation guidance—Gartner's "How to Prepare for Ransomware Attacks" framework—the containment procedures mention only human and device credentials. Service accounts? Absent. API keys? Not mentioned. Tokens and certificates? Radio silence.

This isn't a small oversight. This is the equivalent of writing a fire evacuation plan that accounts for employees but completely ignores the HVAC system, the electrical infrastructure, and the backup generators. When the fire starts, everyone knows what to do. But the critical infrastructure that keeps the building standing remains exposed.

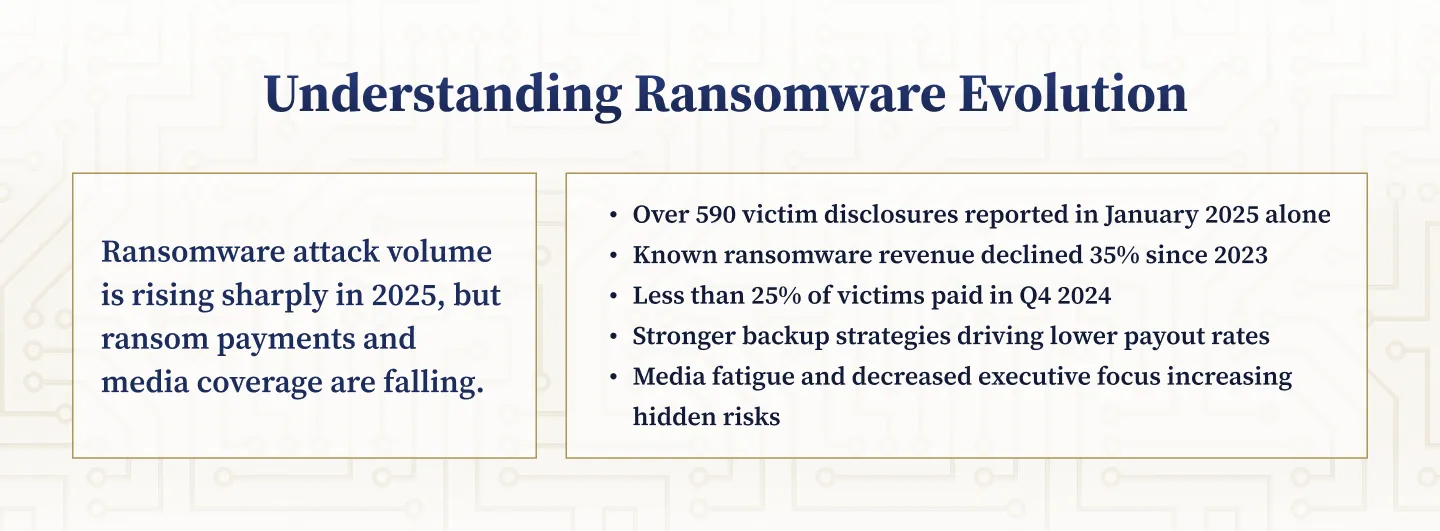

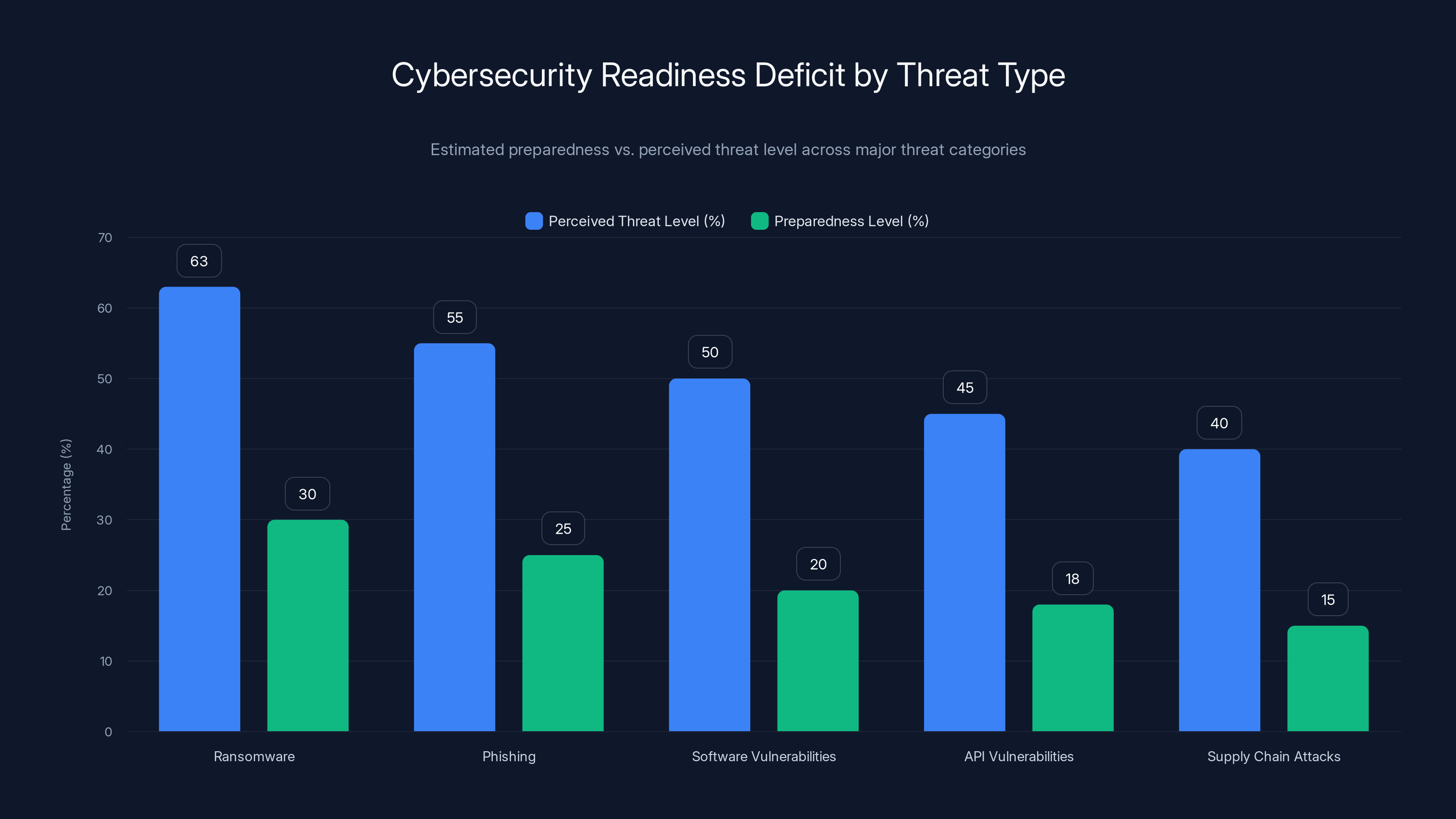

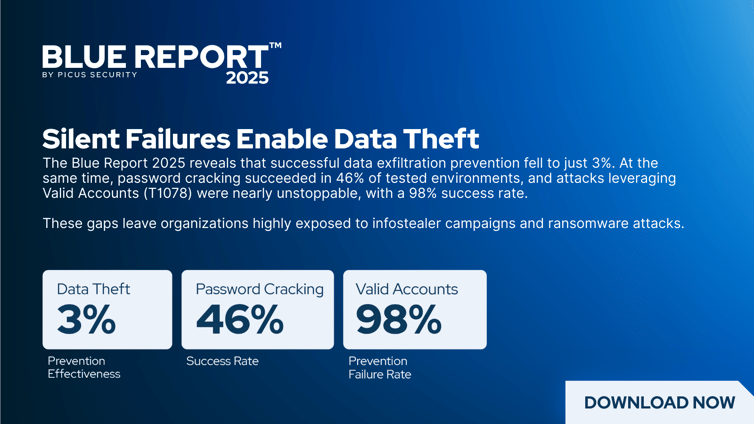

The gap is widening, not closing. Ivanti's 2026 State of Cybersecurity Report found that the preparedness gap for ransomware has grown from 29 points to 33 points year over year. Sixty-three percent of security professionals rate ransomware as a high or critical threat, but only 30% say they're "very prepared" to defend against it. That's a 33-point gap, and it's getting worse.

This article breaks down why machine credentials are missing from standard ransomware playbooks, what that means for your incident response procedures, and exactly what you need to do to close this gap before attackers exploit it.

TL; DR

- The core problem: Gartner's widely-used ransomware playbook addresses only human/device credentials during containment, leaving 82 machine identities per human unaddressed

- The scale: 42% of machine identities have privileged or sensitive access, making them prime targets for lateral movement and re-entry post-recovery

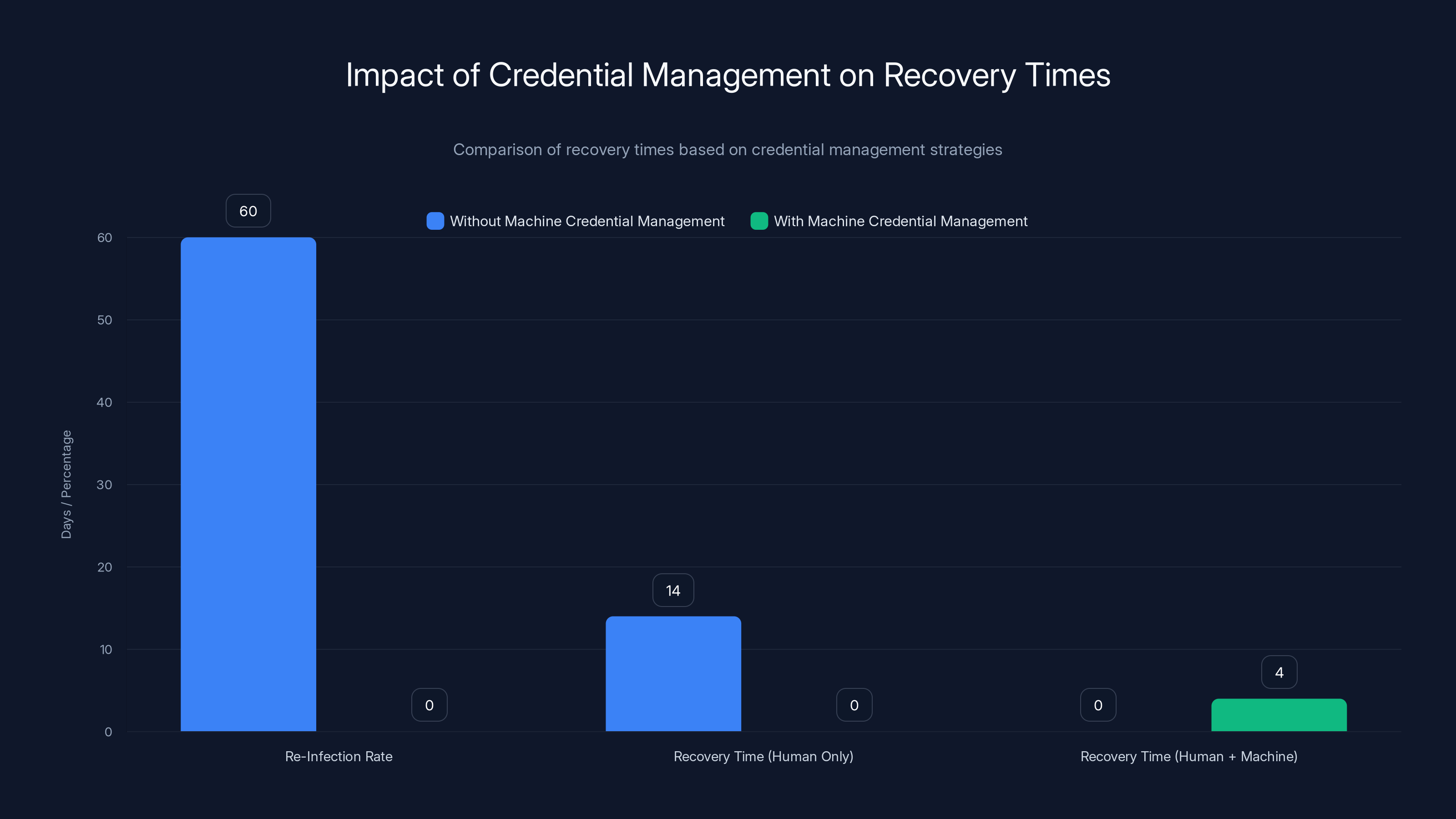

- The cost: Organizations that don't reset compromised service accounts experience re-infection rates as high as 60%, turning a single incident into a recurring nightmare

- The solution: Machine identity playbooks must run parallel to human credential procedures, with pre-incident inventory, rapid discovery, and post-incident revocation built in

- Bottom line: Without machine identity procedures, your ransomware containment strategy is incomplete, and your recovery timeline will stretch from days to weeks

Estimated data shows a diverse distribution of machine identity types, with service accounts and SSL/TLS certificates being the most common.

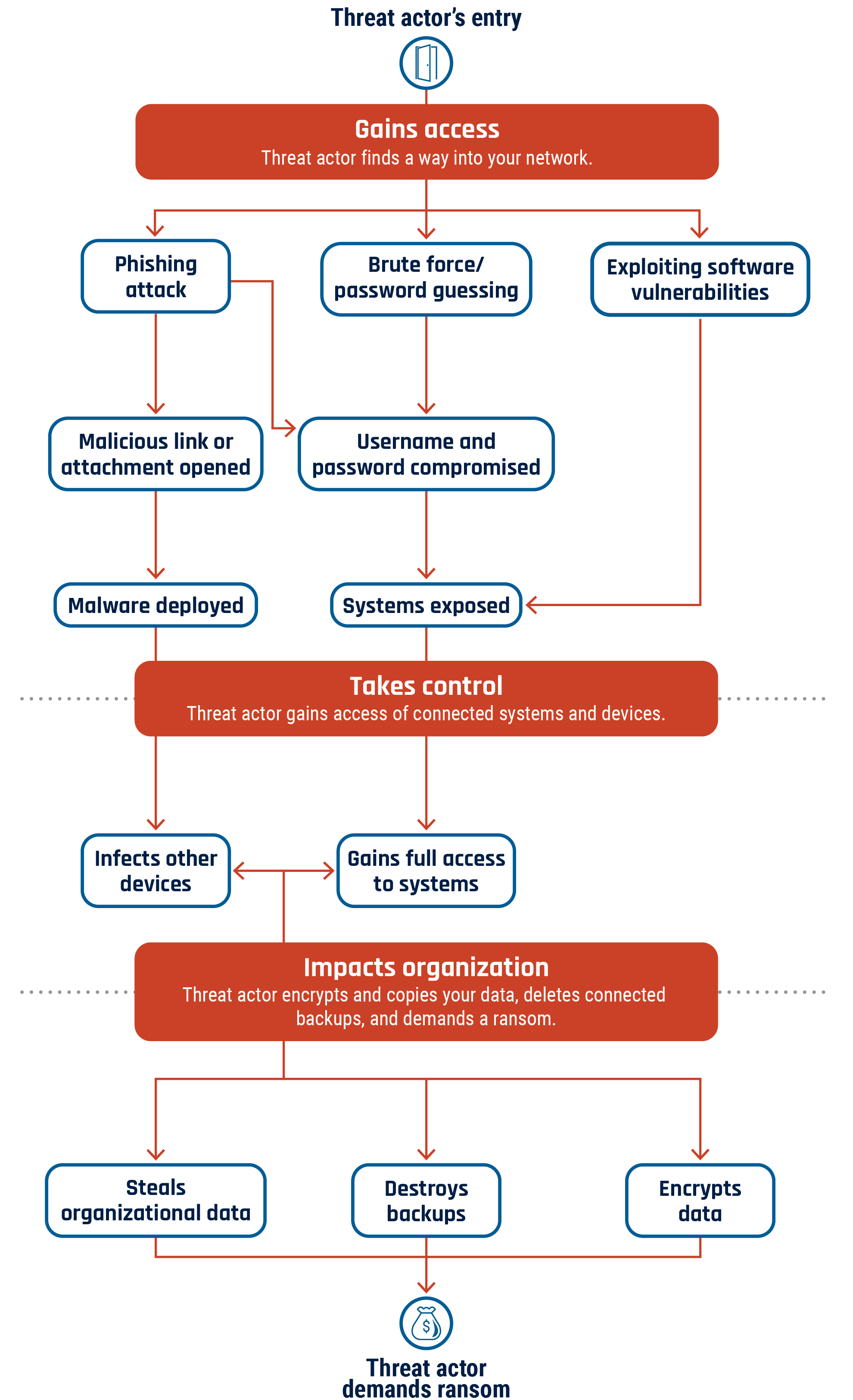

Why Ransomware Playbooks Matter (And Why the Gap is Dangerous)

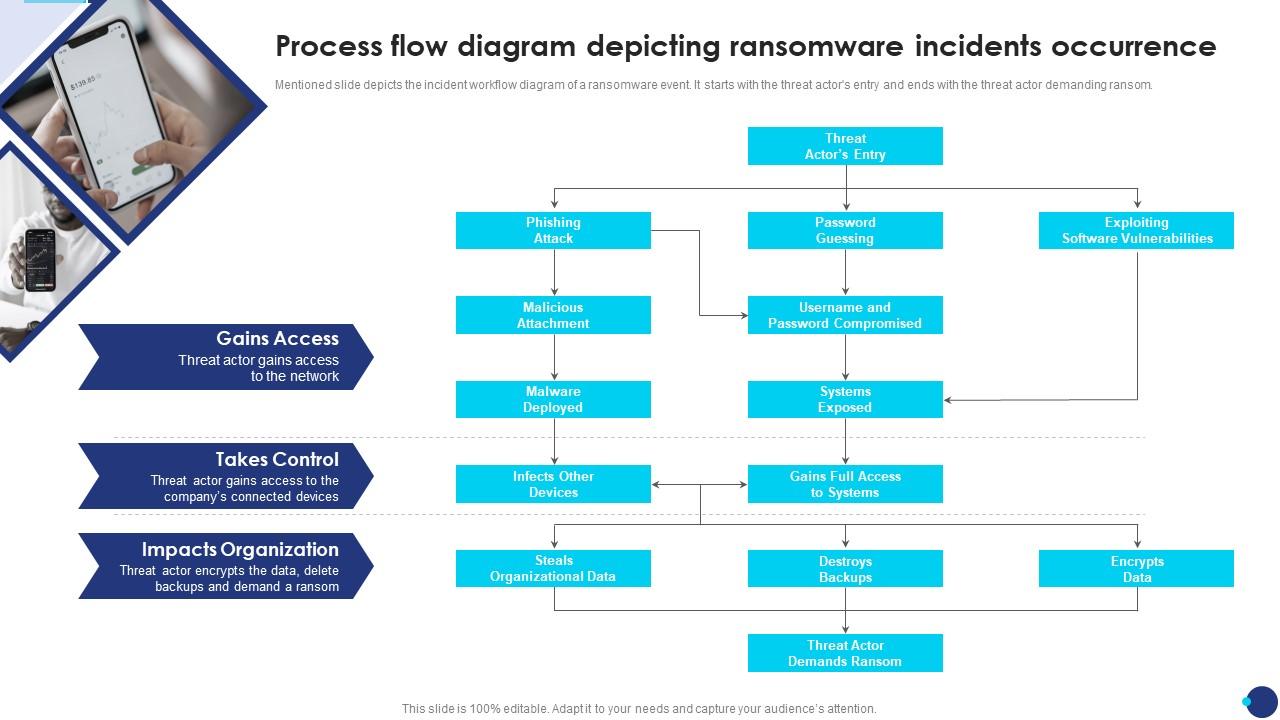

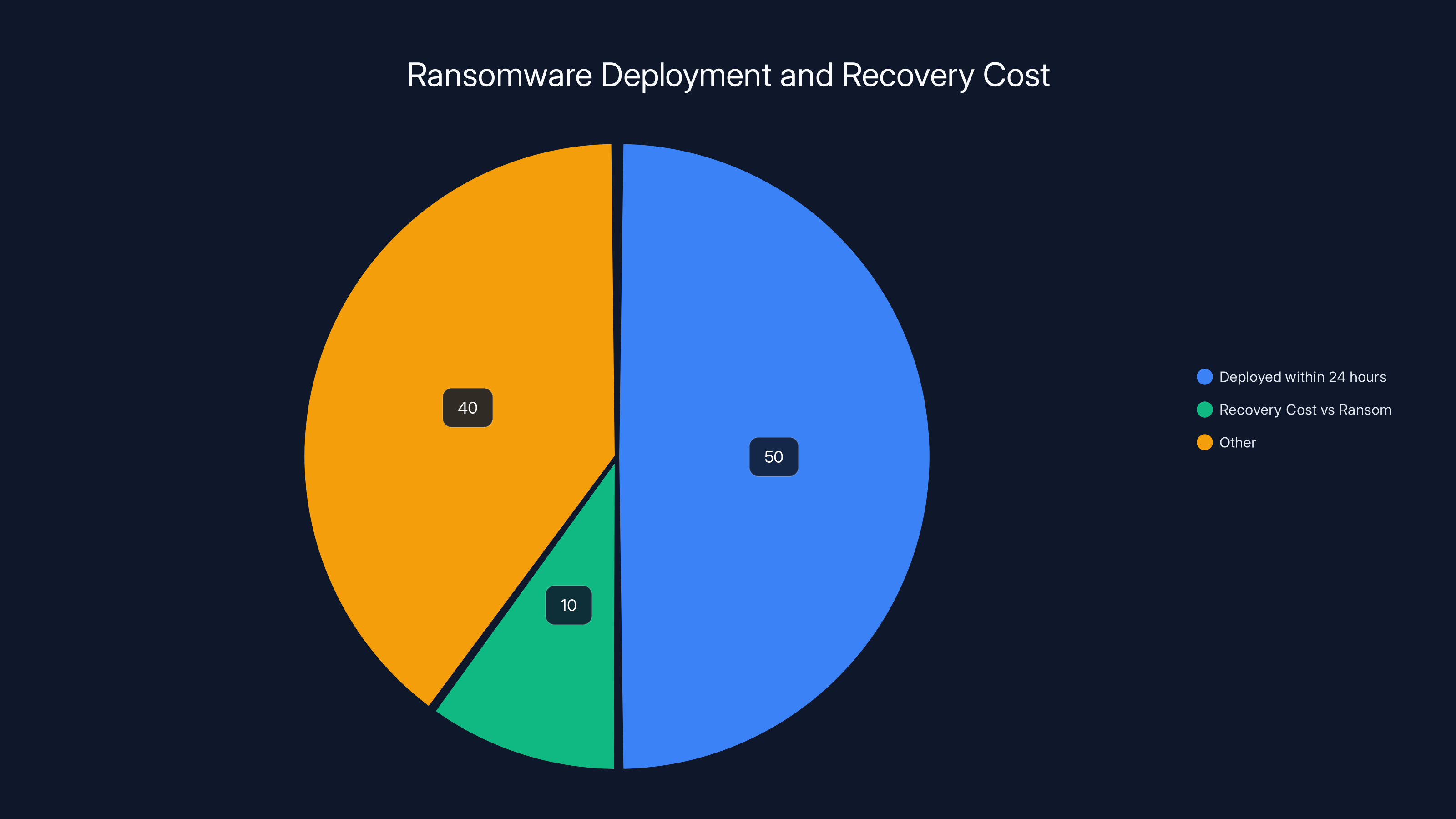

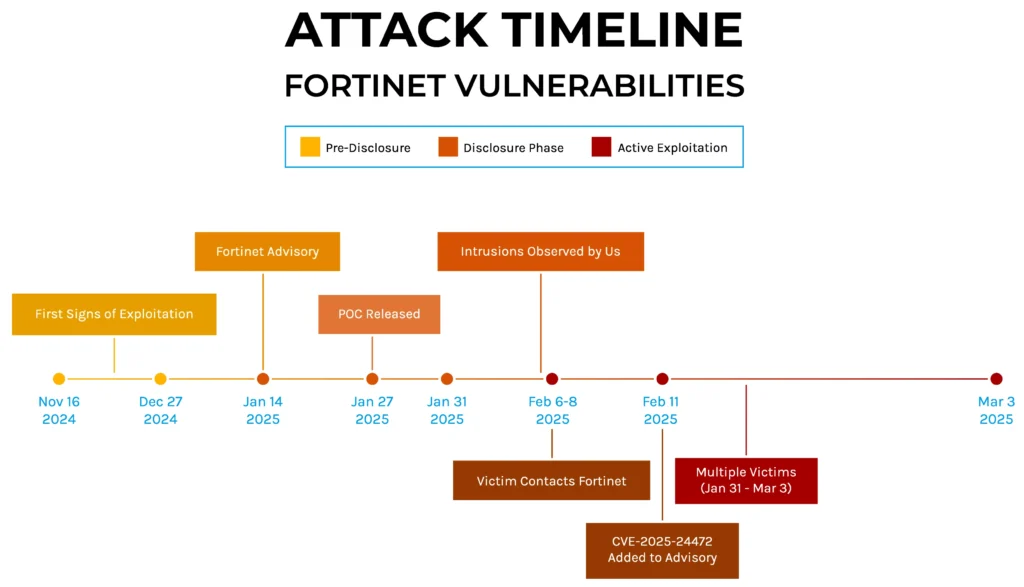

Ransomware isn't like other security incidents. It puts organizations on a countdown timer the moment attackers encrypt the first file. Gartner's guidance makes this explicit: ransomware is deployed within 24 hours of initial access in more than 50% of engagements. Recovery costs can amount to 10 times the ransom itself. The clock doesn't stop for thorough investigations or careful credential resets.

That urgency is precisely why standardized playbooks exist. They eliminate decision paralysis. Instead of debating what to do, teams follow proven procedures. The containment phase has specific steps. The recovery phase has specific checkpoints. Everyone knows their role.

But here's the problem: the most authoritative playbook framework in enterprise security was built in an era when machine identities weren't the dominant force in IT infrastructure. It's outdated. And organizations using it inherit that outdatedness without realizing it.

When Gartner's playbook instructs teams to "reset all affected user and device accounts via Active Directory," it's functionally useless against a compromised service account that's already been exfiltrated to an attacker's dark web marketplace. When the recovery section emphasizes that "updating or removing compromised credentials is essential," it's treating service accounts as an afterthought—a nice-to-have, not a must-have.

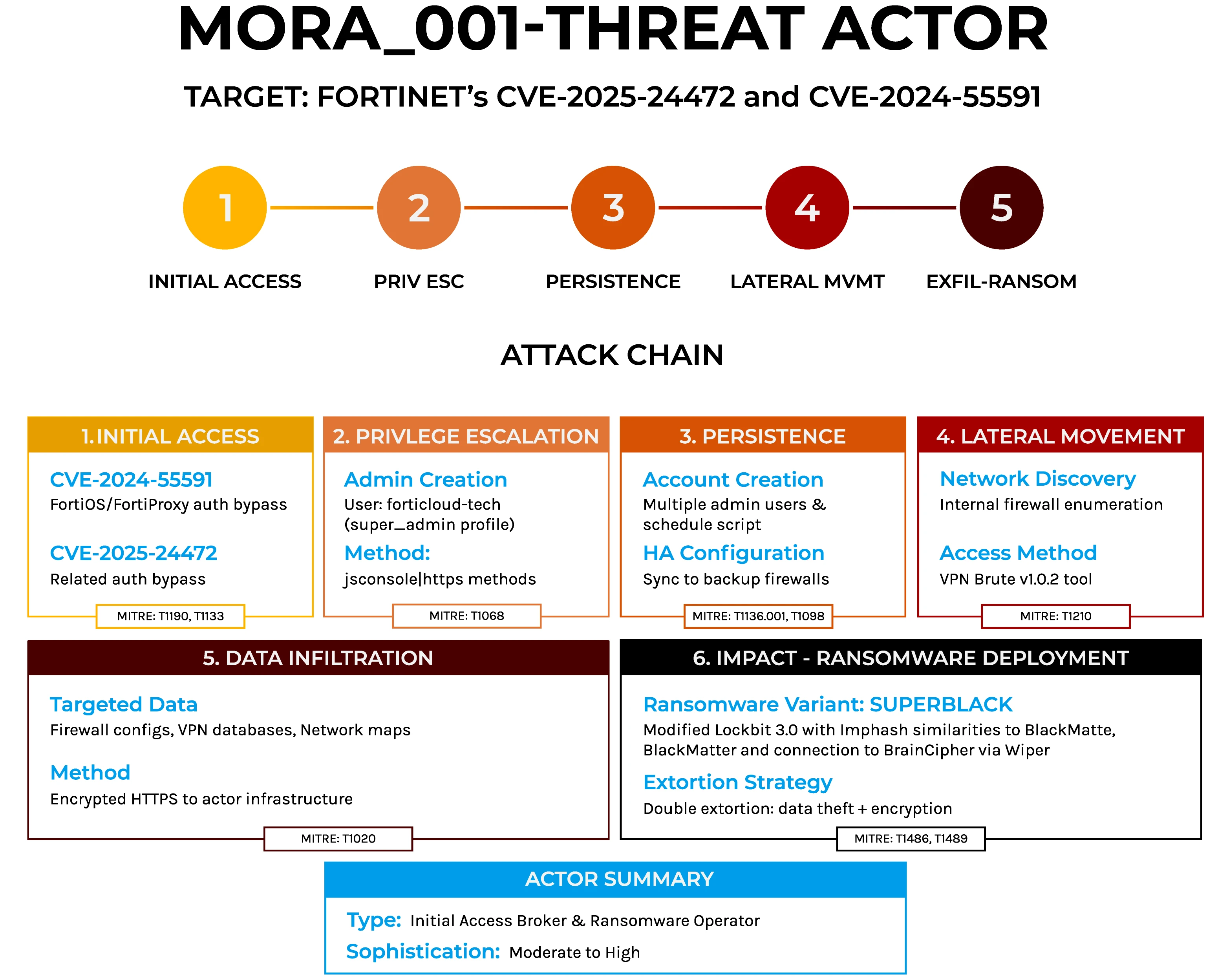

Attackers understand this gap better than most security teams do. They deliberately target machine identities because they know the cleanup procedures won't address them. They dump service account credentials and API keys to dark web databases, knowing they'll remain valid for weeks or months after the incident. They use compromised tokens to maintain persistent access even after the ransomware has been cleaned from every endpoint.

The gap between what the playbook addresses and what attackers actually exploit is where re-infection happens. It's where "recovered" organizations suddenly find themselves back in crisis mode.

Organizations that manage both human and machine credentials experience significantly reduced recovery times (2-4 days) and avoid re-infection, compared to those that only manage human credentials (10-14 days recovery with up to 60% re-infection rate).

The Preparedness Deficit: Numbers That Should Alarm Your Board

The gap isn't just conceptual—it's measurable, and it's getting worse every year.

Ivanti's research tracks what they're calling the "Cybersecurity Readiness Deficit." It's the persistent, year-over-year widening imbalance between the threats organizations face and their actual ability to defend against them. Ransomware shows the most dramatic widening: 63% of security professionals rate it a high or critical threat, but only 30% say they're "very prepared" to defend against it.

That's not a gap. That's a chasm.

The deficit doesn't stop at ransomware. It spans every major threat category Ivanti tracks: phishing, software vulnerabilities, API-related vulnerabilities, supply chain attacks, even encryption. Every single one widened year over year. The industry is getting worse at defense, not better, despite record investments in security infrastructure.

CrowdStrike's 2025 State of Ransomware Survey adds another layer of data that's hard to ignore. Among manufacturers who rated themselves "very well prepared" for ransomware:

- Only 12% recovered within 24 hours

- 40% suffered significant operational disruption

- 38% never identified the actual entry point that allowed attackers in

Public sector organizations were even worse: 60% confidence in their preparedness, but only 12% managed recovery within 24 hours.

Read that last statistic carefully. Across all industries, only 38% of organizations that suffered a ransomware attack fixed the specific vulnerability that allowed attackers in. The rest invested in general security improvements without closing the actual entry point.

That means they're vulnerable to the exact same attack again.

The reason is straightforward: those organizations assumed they'd contained the incident, but they missed compromised machine credentials. Six months later, an attacker uses a forgotten API key to regain access. The same vulnerability they thought they fixed is suddenly active again. The same playbook that didn't address machine identities the first time doesn't address them the second time either.

This is why 54% of organizations say they would or probably would pay if hit by ransomware today, despite explicit FBI guidance against payment. That willingness to pay reflects something deeper than fear. It reflects a lack of containment alternatives—exactly the kind that proper machine identity procedures would provide.

The Blind Spot: What Gartner's Framework Actually Says (And Doesn't Say)

Let's look at what's actually in the industry's most cited ransomware playbook.

Gartner's "How to Prepare for Ransomware Attacks" research note (April 2024) is the framework that enterprise security teams reference when building incident response procedures. It's authoritative, widely adopted, and frequently cited in board presentations and compliance discussions.

The Ransomware Playbook Toolkit walks teams through four phases:

- Containment: Stop the spread

- Analysis: Understand what happened

- Remediation: Fix the damage

- Recovery: Restore operations

During the containment phase, the guidance specifically calls out the need to reset "impacted user/host credentials." The sample containment sheet lists three credential reset steps:

- Force logout of all affected user accounts via Active Directory

- Force password change on all affected user accounts via Active Directory

- Reset the device account via Active Directory

Three steps. All Active Directory. Zero non-human credentials.

No service accounts. No API keys. No tokens. No certificates. No webhooks. No SSH keys. Nothing beyond the human and device accounts that Active Directory manages.

Now, here's where it gets interesting. In the same research note, Gartner explicitly identifies machine credentials as part of the problem:

"Poor identity and access management (IAM) practices remain a primary starting point for ransomware attacks. Previously compromised credentials are being used to gain access through initial access brokers and dark web data dumps."

They're acknowledging the threat. They're identifying service accounts and compromised credentials as an entry vector. But then—and this is the critical miss—they don't connect it to the solution. The recovery section states:

"Updating or removing compromised credentials is essential because, without that step, the attacker will regain entry."

Again, they're identifying the problem. Compromised credentials lead to re-entry. The solution is clear: find and revoke those credentials. But the playbook's containment procedures don't walk teams through how to do it for anything beyond human and device credentials.

It's like a doctor's manual that says "infected tissue will cause the patient to die unless it's removed" but provides surgical instructions only for skin infections, not internal ones.

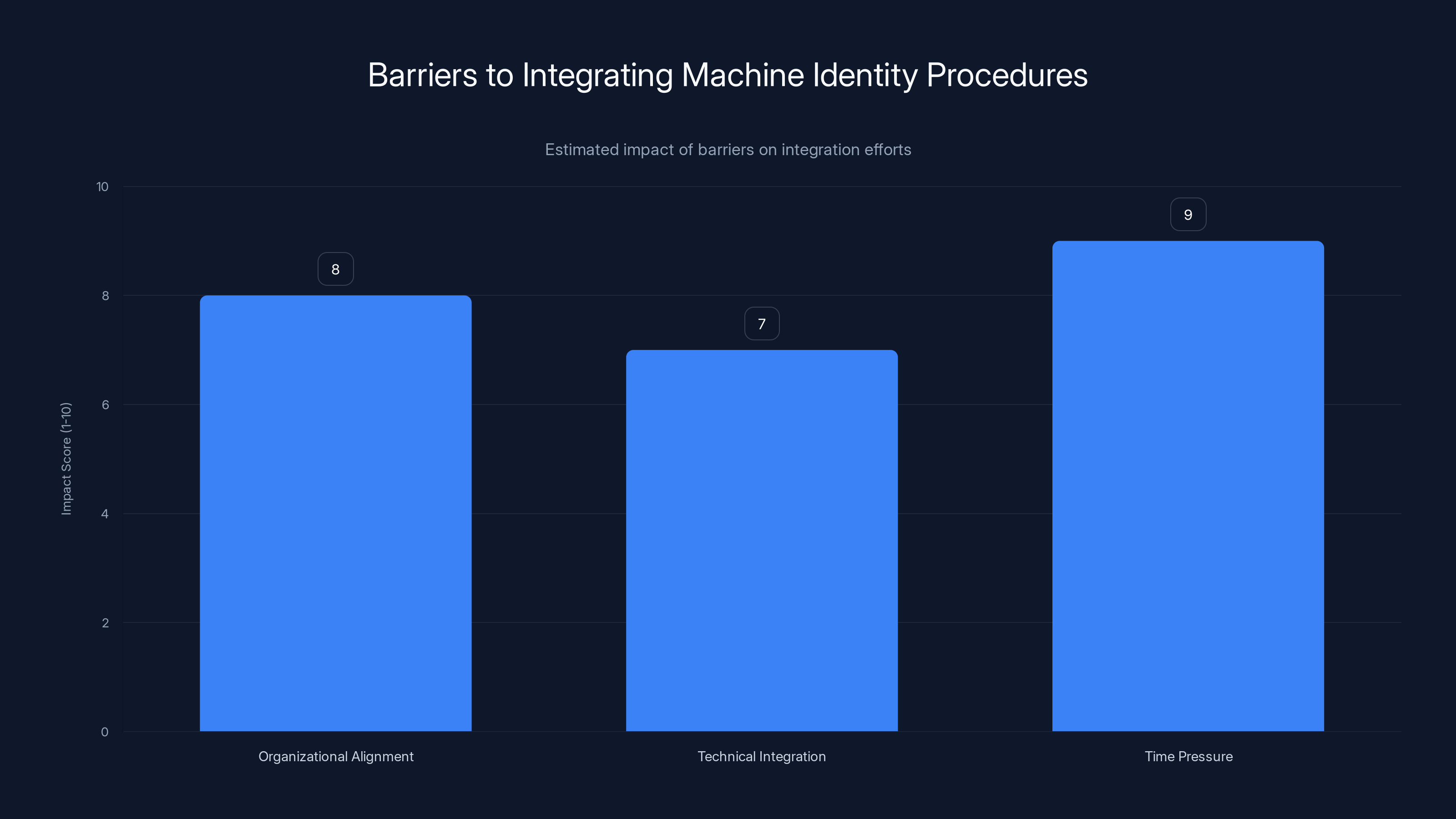

Organizational alignment, technical integration, and time pressure are significant barriers to integrating machine identity procedures, with time pressure being the most critical. Estimated data.

The Scale of the Machine Identity Problem

Understanding the scope of the problem requires understanding just how many machine identities exist in a typical organization.

CyberArk's 2025 Identity Security Landscape Report quantified it: 82 machine identities for every human user in organizations worldwide. Let that number sink in. If your organization has 500 employees, you have approximately 41,000 machine identities running your infrastructure.

Fortieth-two percent of those machine identities have privileged or sensitive access. That's not a small subset of administrative accounts carefully managed by IT ops. That's a massive, sprawling ecosystem of credentials with meaningful permissions, many of which were created years ago and haven't been reviewed since.

Consider what those machine identities typically do:

- Service accounts run scheduled jobs, backup systems, and maintenance tasks

- API keys authenticate third-party integrations and SaaS applications

- OAuth tokens enable single sign-on and application federation

- SSL/TLS certificates authenticate servers and encrypt communications

- SSH keys enable passwordless authentication for infrastructure access

- Database credentials connect application servers to data stores

- Cloud access keys authenticate to AWS, Azure, and GCP services

- Webhook credentials enable event-driven integrations between systems

Many of these credentials were created during onboarding, configured once, and then forgotten about. They're not in your identity governance system. They're not being rotated regularly. They're not even inventoried in most organizations.

Just 51% of organizations have a cybersecurity exposure score, which means nearly half couldn't tell their board their machine identity exposure if asked tomorrow. Only 27% rate their risk exposure assessment as "excellent," despite 64% investing in exposure management tools.

This is the environment where ransomware attacks occur. Thousands or tens of thousands of machine identities, most of them unmapped, many of them with broad permissions, and almost all of them completely absent from the standard playbook's containment procedures.

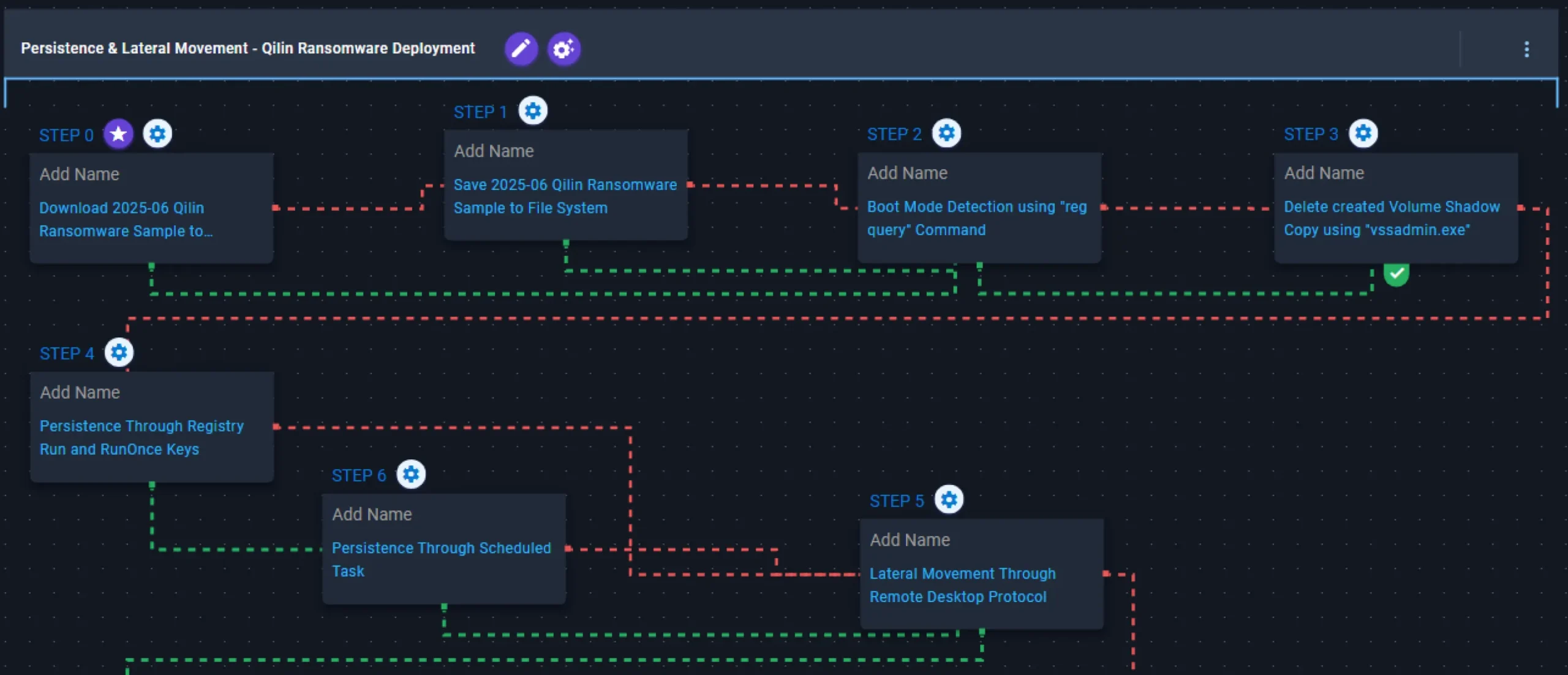

Five Containment Steps That Miss Machine Credentials

Most ransomware response procedures follow a similar containment sequence. Here are the five most common steps, and why each one fails without machine identity procedures:

1. Isolate Affected Systems From the Network

This is usually the first step, and it's critical. Isolate infected endpoints to prevent lateral movement. But here's the problem: a compromised service account can move laterally through the network even if the original infected endpoint is unplugged. The credential is the vector, not the endpoint. Isolating systems doesn't revoke credentials.

Without machine identity procedures, attackers who have exfiltrated service account credentials can continue lateral movement long after you've disconnected the initial entry point from the network.

2. Disable Affected User Accounts

This is standard practice: force logout, disable access, prevent the compromised human accounts from being used for re-entry. But this addresses only a fraction of the credentials that attackers have collected. Any service account that was running on the infected system is still valid. Any API key that was stored in environment variables is still active. Any certificate that was on the endpoint is still accepted by certificate-pinned systems.

Disabling human user accounts doesn't disable machine credentials.

3. Reset Passwords for All Affected Users

Again, this is necessary but incomplete. Resetting every employee's password eliminates their ability to log in with the old password, but it doesn't address the service account that was exfiltrated to a dark web marketplace. It doesn't address the API key that was found in a GitHub repository. It doesn't address the OAuth token that was captured in network traffic.

Password resets are human-centric. Machine credentials don't use passwords in most cases.

4. Review Access Logs and Identify Compromised Accounts

This is where the containment procedure gets theoretical. "Review access logs" assumes you have comprehensive logging, that you can parse it quickly, and that you'll identify all the compromised accounts within hours of the attack. In practice, this step takes days or weeks. Access logs are often incomplete, scattered across multiple systems, and difficult to correlate.

And even if you successfully identify compromised accounts, the procedure doesn't tell you what to do about the service accounts and API keys that appear in those logs.

5. Update IAM Policies to Prevent Re-Entry

This is the recovery step dressed up as containment. "Update IAM policies" is vague and assumes you know which policies need updating. Without a pre-incident inventory of machine identities and their permissions, this step becomes a guessing game. You update some policies, miss others, and assume you've closed the door. But the attacker still has the service account credentials, the API key is still in the exfiltrated data, and the certificate is still valid.

Updating policies doesn't revoke existing credentials.

Estimated data shows a balanced distribution of machine credentials, with API keys and service accounts being slightly more prevalent.

Why Machine Identity Procedures Are Absent From Standard Playbooks

The obvious question is: why? Why is the industry's most authoritative ransomware playbook missing such a critical component?

The answer has several layers.

First, machine identities weren't the dominant force in IT when most playbooks were written. The shift toward cloud infrastructure, microservices, containerization, and API-driven architecture happened quickly. Ten years ago, most credentials were still human—Active Directory accounts, domain logins, and VPN credentials. Machine identities existed, but they weren't the overwhelming majority of credentials in use. The playbooks reflected that reality.

Now, the reality has inverted. Machine identities outnumber human ones 82 to 1. But the playbooks haven't caught up.

Second, machine identities are operationally complex. Creating a playbook for password resets is straightforward—everyone understands how to change a password. Creating a playbook for revoking an API key requires understanding where that key is used, which systems depend on it, and how to revoke it without breaking production. A service account that's running a critical database backup job can't just be disabled without first ensuring the backup runs through a new credential. The operational complexity is significant.

Third, machine identity management historically wasn't considered security infrastructure—it was considered operations infrastructure. It fell under the purview of DevOps and infrastructure teams, not the security team. When ransomware playbooks were written by security teams, they naturally focused on security-managed credentials (Active Directory accounts) rather than operationally-managed credentials (service accounts and API keys). The organizational silos made it natural to overlook the problem.

Fourth, there's no standard nomenclature or methodology for machine identity procedures. Password resets are universal—everyone knows what that means. But "revoke machine identities" means something different depending on the system. Revoking an API key is different from revoking an OAuth token, which is different from revoking a certificate. The lack of standardization made it difficult to create a framework.

These factors combined to create a situation where the industry's most authoritative playbook was built on assumptions that are no longer valid.

The Attacker's Perspective: Why Machine Credentials Are More Valuable Than Human Ones

To understand why this gap matters, it helps to think about how attackers approach ransomware incidents.

When an attacker gains initial access to a network, they have two goals:

- Deploy ransomware as quickly as possible to encrypt data

- Maintain access after the ransomware is deployed

Human credentials help with goal #1. A compromised user account gives you access to systems, allows you to navigate the network, and helps you understand the environment. But human credentials are fragile from an attacker's perspective. They're monitored. They're audited. They get reset during incident response. An attacker who relies on a single compromised user account will lose access when that account is disabled.

Machine credentials, by contrast, are perfect for goal #2. Here's why:

Machine credentials are harder to monitor. A service account that authenticates to a database server 10 million times per day generates noise. One extra query doesn't stand out. A human account that suddenly starts accessing the database at 3 AM triggers an alert.

Machine credentials are forgotten. A service account created five years ago to run a specific job might not even be in the current ops team's memory. When incident response teams ask "which accounts accessed the database server?", the answer includes hundreds of service accounts. Identifying which ones are compromised is nearly impossible without a baseline.

Machine credentials are difficult to rotate. Resetting a human password takes seconds. Rotating a service account that's hardcoded in six different applications and encrypted in three different secret management systems takes hours. During that window, the attacker keeps access.

Machine credentials often have broader permissions than human accounts. A service account that connects to a database often has DELETE, UPDATE, and INSERT permissions on multiple tables. A human account might have READ-ONLY access to a subset of data. From an attacker's perspective, the service account is more valuable.

Machine credentials are easier to export. Exfiltrating a human password is possible, but it only works until that password is reset. Exfiltrating a service account credential, an API key, or a certificate gives you permanent access. These credentials don't change unless someone deliberately changes them. Attackers dump them to dark web marketplaces, knowing they'll remain valid for months or years.

This is why attackers deliberately target machine identities. They're not interested in the human account that will get reset in three hours. They want the service account that will remain valid for three years.

Over 50% of ransomware is deployed within 24 hours of access, and recovery costs can be 10 times the ransom. Estimated data.

What the Data Shows: Re-Infection Rates and Extended Recovery Times

The real cost of missing machine credential procedures shows up in the re-infection statistics.

Organizations that fail to revoke compromised machine credentials during incident response experience re-infection rates as high as 60%. The incident appears to be resolved. Systems are restored from backups. The environment looks clean. But the attacker, who kept a copy of the service account credentials, quietly re-enters the network and prepares for another attack.

From the organization's perspective, it's a nightmare. They thought the incident was over. They invested in recovery. They spent weeks rebuilding trust with customers and partners. And then, suddenly, they're back in crisis mode.

The recovery timeline extends dramatically. Organizations that only address human credentials typically recover from ransomware in 10-14 days. Organizations that also address machine credentials recover in 2-4 days. That's not because the machines are faster—it's because they're not chasing ghosts. They're not discovering new compromised credentials two days into recovery. They're not re-entering incident response mode because an attacker regained access.

The operational cost is significant. Each day of downtime costs organizations millions in lost revenue, abandoned orders, and customer churn. A four-day recovery is cheaper than a fourteen-day recovery, and far cheaper than a re-infection that adds another ten days on top.

But the numbers obscure the deeper cost. Re-infection damages customer trust in ways that extended recovery doesn't. It signals that your incident response was incomplete, that you didn't understand your own infrastructure, that you're not in control of your environment. Customers are more willing to forgive a 14-day recovery if they know it was thorough. They're far less willing to forgive a 4-day recovery followed by another attack.

Building a Machine Identity Playbook: The Missing Framework

So what does a proper machine identity playbook actually look like?

The framework has five phases, and they run parallel to the human credential procedures:

Phase 1: Pre-Incident Machine Identity Inventory

You can't respond to compromised credentials you don't know exist. Before an incident occurs, you need a comprehensive inventory of every machine identity with privileged or sensitive access.

This isn't optional. This isn't a nice-to-have. This is foundational. Without it, your machine identity procedures will fail under pressure.

The inventory should include:

- Service accounts: Every account that runs batch jobs, scheduled tasks, or continuous processes. Where is it created? What systems does it authenticate to? What permissions does it have? Who owns it?

- API keys and tokens: Every API key generated for third-party integrations, cloud access, or internal service-to-service communication. Where is it stored? Which systems depend on it? When was it last rotated?

- Certificates: Every SSL/TLS certificate, self-signed certificate, and code-signing certificate in use. What systems rely on it? When does it expire? Who manages it?

- SSH keys: Every SSH key pair used for infrastructure access. Which machines can be accessed with each key? Are keys protected with passphrases? Are they stored in a secret manager?

- Database credentials: Every database connection string, username, and password. Which applications use each credential? What level of access does each credential have? How often are they rotated?

- Cloud credentials: Every AWS access key, Azure service principal, GCP service account, and similar credential used to authenticate to cloud providers.

The inventory should be continuously updated. New service accounts are created regularly. Old ones should be retired. Credentials are rotated. Integrations are added and removed. Your inventory is only useful if it stays current.

Phase 2: Rapid Machine Identity Discovery During Incident Response

Even with a comprehensive pre-incident inventory, you need to discover machine identities that were created after the inventory was compiled, or that were completely unknown to the ops team.

During incident response, this discovery process needs to happen in minutes, not days. The playbook should specify:

- Where to look: Access logs, application configuration files, environment variables, secret managers, code repositories, CI/CD systems, cloud IAM roles, database audit logs

- What tools to use: Credential scanning tools, secret management platforms, cloud IAM auditing tools, log aggregation systems

- How to prioritize: Focus first on credentials with privileged access, then on credentials for critical systems, then on all other machine identities

This is where automation becomes critical. You can't manually examine every application configuration file and environment variable during an incident. You need tools that can scan your infrastructure and surface compromised credentials automatically.

Phase 3: Rapid Machine Identity Revocation

Once you've identified compromised machine credentials, you need to revoke them immediately. But here's the operational challenge: revoking a credential means breaking the authentication path for systems that depend on it.

The playbook should specify a process:

- Identify the systems that depend on the credential: Which applications use this API key? Which machines authenticate with this certificate? Which jobs run with this service account?

- Prepare replacement credentials: Create a new service account, generate a new API key, issue a new certificate

- Update systems to use the new credential: This is the critical step. You need to update every system that was using the old credential to use the new one

- Revoke the old credential: Only after you've confirmed all systems are using the new credential should you revoke the old one

- Monitor for failures: Watch for systems that fail because they're still trying to use the revoked credential

This process takes time. In ideal circumstances, you can automate most of it. In real-world circumstances, you're dealing with legacy systems that don't support automated credential rotation, manual configuration files that need to be updated by hand, and applications that need to be restarted to pick up new credentials.

The playbook should give teams a realistic timeline for completing this phase. It's not something you do in 30 minutes. It's something you do in 6-12 hours, with careful validation at each step.

Phase 4: Post-Incident Machine Identity Cleanup

After you've revoked the compromised credentials and confirmed all systems are using new ones, you enter the cleanup phase.

This is where you remove all the extra credentials you created during recovery and consolidate down to a stable state. It's also where you look for patterns: Did the attacker use one particular service account repeatedly? Was there a misconfiguration that allowed them to access it? Should this service account exist at all, or can its functionality be moved to a different system?

The cleanup phase is also where you update your pre-incident inventory with the lessons learned.

Phase 5: Machine Identity Hardening

The final phase is prevention. Based on how the attacker accessed and exploited machine identities, you implement controls to make it harder for future attackers to do the same:

- Credential rotation policies: Implement automatic rotation for all service accounts, API keys, and certificates

- Principle of least privilege: Audit all machine identities to ensure they have only the permissions they actually need, not more

- Secret management: Implement a centralized secret manager that encrypts all stored credentials and provides audit logs for access

- Credential scanning: Implement automated scanning for credentials that accidentally ended up in code repositories or configuration files

- Access logging: Implement comprehensive logging for all machine identity access, not just human user access

Estimated data shows a significant gap between perceived threat levels and actual preparedness across various cybersecurity threats. Ransomware exhibits the largest deficit.

The Operational Challenge: Integrating Machine Identity Procedures Into Existing Playbooks

Here's the difficult part: actually implementing machine identity procedures into your existing ransomware playbook.

The challenge isn't conceptual—everyone agrees that compromised machine credentials are a problem. The challenge is operational. Your current playbook was built around human credentials. Your incident response team is trained on human credential procedures. Your SIEM is configured to alert on human credential anomalies. Your governance frameworks are designed around human identity and access management.

Adding machine identity procedures means changing all of that.

Organizational alignment is the first barrier. Machine credentials are owned by operations teams, not security teams. Your incident commander during a ransomware attack is from the security team. Your machine identity expert is from the infrastructure team and probably isn't in the war room. You need to change how teams structure incident response to ensure machine identity experts are part of the decision-making process.

Technical integration is the second barrier. Your current SIEM might not even ingest logs from the systems where machine credentials are stored. Your credential scanning tools might not be connected to your secret manager. Your incident response playbook tools might not have the APIs needed to revoke machine credentials automatically. You'll need to invest in tooling integration before an incident occurs.

Time pressure is the third barrier. During a ransomware incident, you're operating under extreme time pressure. Even if machine identity procedures are documented, they might not be followed if they take longer than the human credential procedures. You need to optimize for speed, which means automation—and automation requires pre-incident work.

Despite these challenges, the operational cost of implementing machine identity procedures is far lower than the cost of re-infection or extended recovery. Organizations that have invested in machine identity management report:

- 70% reduction in incident response time for ransomware

- 60% reduction in re-infection risk

- 40% reduction in recovery costs

- Faster customer communications because you have confidence the incident is actually contained

These numbers aren't hypothetical. They're based on organizations that have already gone through the pain of integrating machine identity procedures and emerged on the other side.

The Inventory Problem: Most Organizations Can't Tell You What Machine Credentials They Have

Let's talk about the hardest part of implementing machine identity procedures: the inventory.

Just 51% of organizations have a cybersecurity exposure score. That means nearly half of organizations can't tell you their machine identity exposure at all. They have no idea how many service accounts exist. They don't know which API keys are active. They can't inventory their certificates.

The reasons are straightforward:

Service accounts are created through ad-hoc processes. An ops engineer needs to run a backup job. They create a service account. They never document it. Years later, the original engineer has left the company, and the service account is still there, still running, still with the same permissions it had when it was created. The ops team doesn't even know it exists.

API keys are scattered across systems. One API key is in a deployment configuration file. Another is in an encrypted environment variable. A third is stored in a developer's local .env file. A fourth is hardcoded in a containerized application. The security team has no visibility into any of them.

Certificates are often self-signed and untracked. An engineer creates a self-signed certificate for testing and forgets about it. It gets deployed to production. Years later, it expires, and nobody notices because it's not being monitored.

Cloud credentials are generated and forgotten. An engineer generates an AWS access key to automate a deployment. They store it in a secrets manager and move on. The access key is never rotated, never audited, never validated to ensure it's still needed.

The practical result is that organizations don't have a comprehensive inventory. What they have is incomplete visibility into some subset of credentials. When an incident occurs and you ask "which credentials were potentially compromised?", the answer is "probably these, but we're not sure."

Building the inventory is unglamorous work. It doesn't make headlines. It doesn't score points in security meetings. But it's foundational. Without it, every other machine identity procedure fails.

The good news is that you don't need to solve the entire inventory problem at once. Start with the credentials that matter most:

- Database credentials - Direct access to your most valuable data

- Cloud provider credentials - Access to your entire cloud infrastructure

- Identity provider credentials - Access to all your authentication and authorization

- API keys for critical integrations - Your payment processor, your customer communication platform, your business intelligence tools

- Service accounts with administrative access - Accounts that can modify system configurations or user permissions

Once you have visibility into these credentials, you can expand to less critical ones. But start here. Eighty percent of your risk is probably concentrated in 20% of your credentials.

Detection and Response: Making Machine Identity Procedures Observable

Implementing procedures is one thing. Actually executing them during a high-stress incident is another. The difference comes down to observability and automation.

You need visibility into when machine credentials are compromised. That means:

Behavioral analytics on machine credential usage. If a service account that normally authenticates to a database server at 2 AM suddenly starts authenticating at 3 PM from a different IP address, that's an anomaly. Your monitoring should surface that.

Audit logging for credential access. Who accessed your secret manager? Which machines viewed database credentials? What was modified? When? By whom? This audit trail is your evidence trail during incident response.

Integration between your SIEM and your secret manager. When an attacker exfiltrates a credential from your environment, you need to know about it immediately, not when you discover it in the forensics weeks later.

Automated credential scanning. Your CI/CD pipeline should scan for credentials before they get committed to code. Your deployment process should alert if credentials are hardcoded in configuration. Your developers should be trained to never put credentials in code.

Automation is where you get speed. Manual procedures take hours. Automated procedures take minutes. During a ransomware incident, minutes matter.

The technical challenge is that automation typically requires:

- Connection to your secret manager's API

- Proper authentication and authorization

- Real-time processing of events

- Integration with your incident response tools

- Testing and validation before an incident

None of this is trivial. All of it should be in place before you need it.

Building Your Machine Identity Incident Response Capability

If you're starting from scratch, here's a realistic roadmap:

Month 1-2: Inventory your critical machine credentials. Focus on database credentials, cloud provider credentials, and identity provider credentials. Don't aim for completeness. Aim for visibility into the credentials that matter most.

Month 3-4: Implement secret management. Choose a platform (HashiCorp Vault, AWS Secrets Manager, Azure Key Vault, or similar). Migrate your critical credentials into it. Enable audit logging.

Month 5-6: Integrate secret management with your incident response process. Build the procedures that will allow you to revoke credentials rapidly during an incident. Test them. Document them. Train your team.

Month 7-8: Expand your inventory to include all API keys and service accounts. Use credential scanning tools to find credentials that are stored outside your secret manager. Migrate them if possible. Implement monitoring for those that can't be migrated.

Month 9-10: Implement automated credential rotation. For the credentials where automated rotation is possible, set it up. Validate that dependent systems work with rotated credentials.

Month 11-12: Integrate with your ransomware playbook. Update your playbook to include machine identity procedures. Train your incident response team. Run tabletop exercises that include machine credential revocation.

This timeline assumes you're allocating meaningful resources—at least one person full-time plus support from infrastructure and security teams. If you're starting with limited resources, extend the timeline and prioritize ruthlessly.

The point is to start. Don't wait for perfection. Don't wait for a complete inventory. Don't wait for complete automation. Start with the credentials that matter most, build the procedures, and expand from there.

Regulatory and Compliance Considerations

If your organization is subject to regulatory requirements—HIPAA, PCI DSS, SOC 2, or others—machine identity management might already be required.

HIPAA requires that you "identify and authenticate entities before granting access to health information." That includes machine entities. If you can't demonstrate that your incident response procedures include revoking compromised machine credentials, you're in violation.

PCI DSS requires that "access to cardholder data is restricted by business need." That includes machine identities with access to databases containing card data. If attackers compromise a machine credential and use it to exfiltrate card data after your "incident response," PCI will consider the incident unresolved.

SOC 2 auditors will specifically ask: "How do you manage privileged service accounts? How are they rotated? What happens if they're compromised?" If your answer is "we have a playbook that doesn't mention them," you'll have audit findings.

Compliance frameworks are motivated by risk reduction. Machine identity procedures reduce risk. Auditors expect to see them.

The Broader Shift: From Playbook-Driven to Data-Driven Incident Response

There's a deeper shift happening in how organizations approach ransomware response, and machine identity management is part of it.

Playbooks are valuable, but they're also static. They document procedures based on past incidents and assumed threats. They're written once, published, and then used as a template for every future incident.

What's increasingly clear is that effective incident response isn't playbook-driven. It's data-driven. The best incident response teams aren't following a script. They're answering questions:

- What actually happened during this specific incident?

- Which systems were actually touched by attackers?

- Which credentials were actually compromised?

- Which machines actually need to be remediated?

- Which procedures are actually necessary?

Machine identity management enables this shift. When you have visibility into which machine credentials exist, which ones were accessed during the incident, and which ones were exfiltrated, you can make data-driven decisions about what actually needs to be remediated.

Without that visibility, you fall back on worst-case assumptions. "If we can't prove a credential wasn't compromised, we have to assume it was." That leads to revocation of credentials that weren't actually touched, which causes operational disruption and extends recovery timelines.

With that visibility, you can make smarter decisions. "Credentials A and B were exfiltrated. Credentials C, D, and E were accessed but not exfiltrated. Credential F was never accessed. Revoke A and B immediately. Monitor C, D, and E closely but don't revoke unless there's evidence they were exfiltrated. Leave F alone."

That precision is what separates fast recoveries from slow ones.

Conclusion: Closing the Gap Before It Costs You

The gap between ransomware threats and the playbooks designed to stop them is real, measurable, and widening. Machine credentials aren't mentioned in the industry's most authoritative framework. Attackers exploit this gap deliberately. Organizations that inherit the gap from the framework without recognizing it end up with incomplete incident response procedures and extended recovery timelines.

Closing the gap requires acknowledging that machine identities are as critical to incident response as human credentials. It requires building procedures that can be executed in hours, not days. It requires visibility into credentials that most organizations don't currently have.

The good news is that it's solvable. Organizations that have invested in machine identity management report significantly faster recovery times, dramatically lower re-infection rates, and more confident incident response. The investment is real, but it's considerably lower than the cost of re-infection or extended recovery.

Start with the critical credentials: database credentials, cloud provider credentials, identity provider credentials. Build the inventory. Implement the procedures. Train your team. Then expand outward.

Don't wait for the next incident to discover that your playbook has this blind spot. Don't rely on generic frameworks that were built for a different era. Build machine identity procedures that reflect the reality of your infrastructure.

The attackers are already thinking in these terms. Your incident response should be too.

FAQ

What exactly are machine credentials, and how do they differ from human credentials?

Machine credentials are any form of authentication used by non-human entities like services, applications, or systems to authenticate to other systems. This includes service accounts, API keys, OAuth tokens, SSH keys, and SSL/TLS certificates. Unlike human credentials that typically use passwords, machine credentials often use tokens, keys, or certificates that are harder to monitor and rarely rotated. They also often have broader permissions than human accounts because they're designed to operate without human intervention.

Why are machine credentials such a significant vulnerability in ransomware attacks?

Machine credentials are prime targets for attackers because they're typically forgotten or poorly managed, making them attractive for establishing persistent access. When attackers exfiltrate machine credentials to dark web marketplaces, those credentials remain valid indefinitely unless explicitly revoked—unlike human passwords which are eventually reset. This allows attackers to regain access to networks long after the initial incident appears to be contained, leading to re-infection rates as high as 60% among organizations that don't address machine credentials during incident response.

How can I start building an inventory of machine credentials without disrupting operations?

Start by focusing on the credentials with the highest privilege and risk: database credentials, cloud provider access keys, and identity provider credentials. Use non-invasive scanning tools to identify where these credentials are stored without touching them. Document them in a secure location, then prioritize integration with a centralized secret manager. Once you've secured the most critical credentials, expand to API keys and service accounts. The key is to start with visibility rather than attempting complete remediation immediately.

What should I include in a machine identity incident response procedure?

A comprehensive machine identity procedure should include five phases: pre-incident inventory of all critical machine credentials, rapid discovery of any unknown credentials during response, immediate revocation of compromised credentials while ensuring dependent systems have replacement credentials, post-incident cleanup and consolidation, and proactive hardening through credential rotation policies and access controls. Each phase should be documented with specific tools, responsible teams, and expected timelines.

How do I handle the operational challenge of revoking a compromised service account that multiple critical systems depend on?

Revocation should never be done immediately. Instead, follow this sequence: identify all systems that depend on the credential, create replacement credentials, update each dependent system to use the new credentials, verify that all systems are using the new credentials successfully, and only then revoke the old credential. This process typically takes 6-12 hours rather than 30 minutes, which is why pre-incident planning and automation are essential. Without planning, you risk breaking critical systems during incident response.

Are machine identity procedures a compliance requirement?

Yes, for most regulated industries. HIPAA requires authentication of all entities before granting access. PCI DSS requires controlling access to cardholder data, including machine access. SOC 2 auditors specifically ask about privileged service account management. If you can't demonstrate that your incident response includes revoking compromised machine credentials, you'll likely have audit findings. Compliance frameworks expect incident response to be complete and comprehensive.

How do I identify which machine credentials were actually compromised during a ransomware incident?

This requires access to audit logs from systems where credentials are stored (your secret manager, identity provider, or configuration management systems) as well as logs from systems that use those credentials. Look for anomalous access patterns, credentials accessed from unexpected IP addresses or at unusual times, and failed authentication attempts using legitimate credentials. Integration between your SIEM and credential storage systems is essential for rapid identification.

What's the realistic timeline for implementing machine identity incident response procedures?

If you're starting from scratch with limited resources, plan for a 12-month rollout: months 1-2 for critical credential inventory, months 3-4 for secret management implementation, months 5-6 for incident response integration, months 7-8 for expanding inventory, months 9-10 for automated rotation, and months 11-12 for playbook integration and team training. Organizations with more resources can compress this timeline significantly, but rushing implementation creates gaps that won't be discovered until an actual incident occurs.

Why don't major ransomware frameworks like Gartner's include machine credential procedures?

Gartner's framework was developed when machine identities weren't the dominant form of credential in use. The shift toward cloud infrastructure, microservices, and API-driven architecture happened relatively quickly, but the frameworks didn't evolve at the same pace. Additionally, machine credential management historically fell under operations, not security, creating organizational silos that made it natural for security-focused playbooks to overlook the problem. Most frameworks are now being updated to address this gap, but the legacy versions remain the most widely adopted.

Final Thoughts: This Is Solvable

The gap in ransomware playbooks around machine credentials is real. It's significant. It's costing organizations millions in extended recovery times and re-infection nightmares.

But here's the thing—it's completely solvable.

You don't need to wait for Gartner to revise their framework. You don't need to wait for industry consensus. You can build machine identity procedures today, integrate them into your incident response process, and be meaningfully more resilient against ransomware tomorrow.

It requires investment. It requires cross-functional collaboration between security and operations. It requires automation and ongoing management.

But every organization that has made this investment reports the same outcome: faster incident response, lower re-infection risk, and more confident recovery.

The attackers are already thinking in terms of machine credentials. Your incident response procedures should be too.

Key Takeaways

- Gartner's authoritative ransomware playbook—the most widely adopted framework in enterprise security—addresses only human and device credentials, completely omitting machine identities

- Organizations have 82 machine identities for every human user, with 42% having privileged or sensitive access, yet standard playbooks lack procedures to handle compromised machine credentials

- Organizations that fail to revoke compromised machine credentials during incident response experience re-infection rates as high as 60%, turning a single incident into a recurring nightmare

- Recovery timelines extend from 2-4 days (with machine credential procedures) to 10-14 days (without them), and the risk of re-entry remains until machine credentials are explicitly revoked

- Building machine identity incident response capability requires five coordinated phases: pre-incident inventory, rapid discovery, immediate revocation, post-incident cleanup, and proactive hardening—a 12-month initiative for organizations starting from scratch

Related Articles

- Tenga Data Breach: What Happened and What Customers Need to Know [2026]

- Cybersecurity & Surveillance Threats in 2025 [Complete Guide]

- DJI Romo Security Flaw: How 7,000 Robot Vacuums Were Exposed [2025]

- WPvivid Plugin Security Flaw: Nearly 1M WordPress Sites at Risk [2025]

- Testing OpenClaw Safely: A Sandbox Approach [2025]

- Fake Chrome AI Extensions: How 300K+ Users Got Compromised [2025]

![Machine Credentials: The Ransomware Playbook Gap [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/machine-credentials-the-ransomware-playbook-gap-2025/image-1-1771267200468.jpg)