DNS Malware Detour Dog: How 30,000+ Legitimate Websites Are Being Weaponized [2025]

You've probably visited thousands of websites without thinking twice about it. The site loads, you click around, maybe buy something, and move on. What if I told you that tens of thousands of those "safe" websites are quietly committing cybercrimes behind the scenes, and neither you nor most security tools would ever notice?

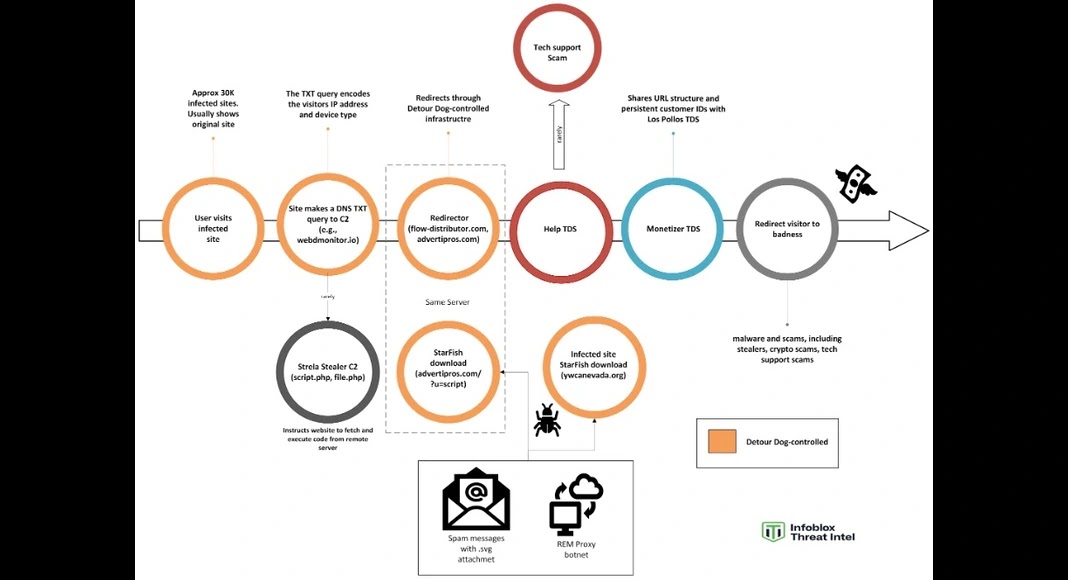

This is the reality of Detour Dog, one of the most insidious malware operations discovered in recent years. Unlike flashy ransomware attacks that announce themselves with ransom notes and encrypted files, Detour Dog operates in the shadows. It hijacks legitimate websites, weaponizes the DNS protocol that literally powers the internet, and uses them as distribution channels for information-stealing malware like Strela Stealer. The operation is so stealthy that infected sites can remain compromised for over a year without detection.

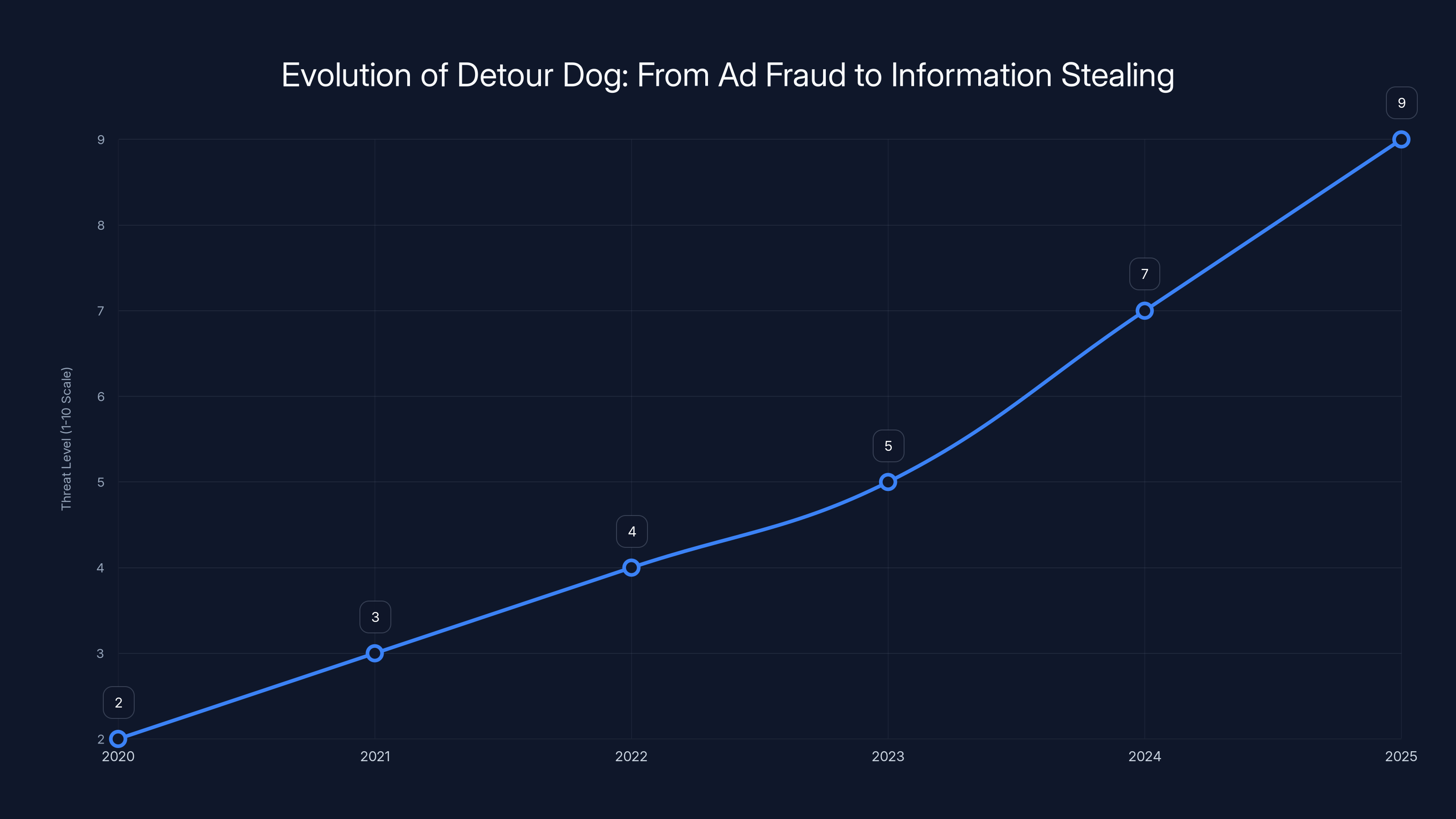

What makes this threat particularly dangerous is how it's evolved. When Detour Dog first emerged, researchers thought they were chasing a simple ad-fraud scheme. But by late 2024, the operation had morphed into something far more sinister: a malware distribution platform that could steal browser credentials, harvest sensitive data, and execute remote commands through nothing more than a website visit or a malicious email attachment.

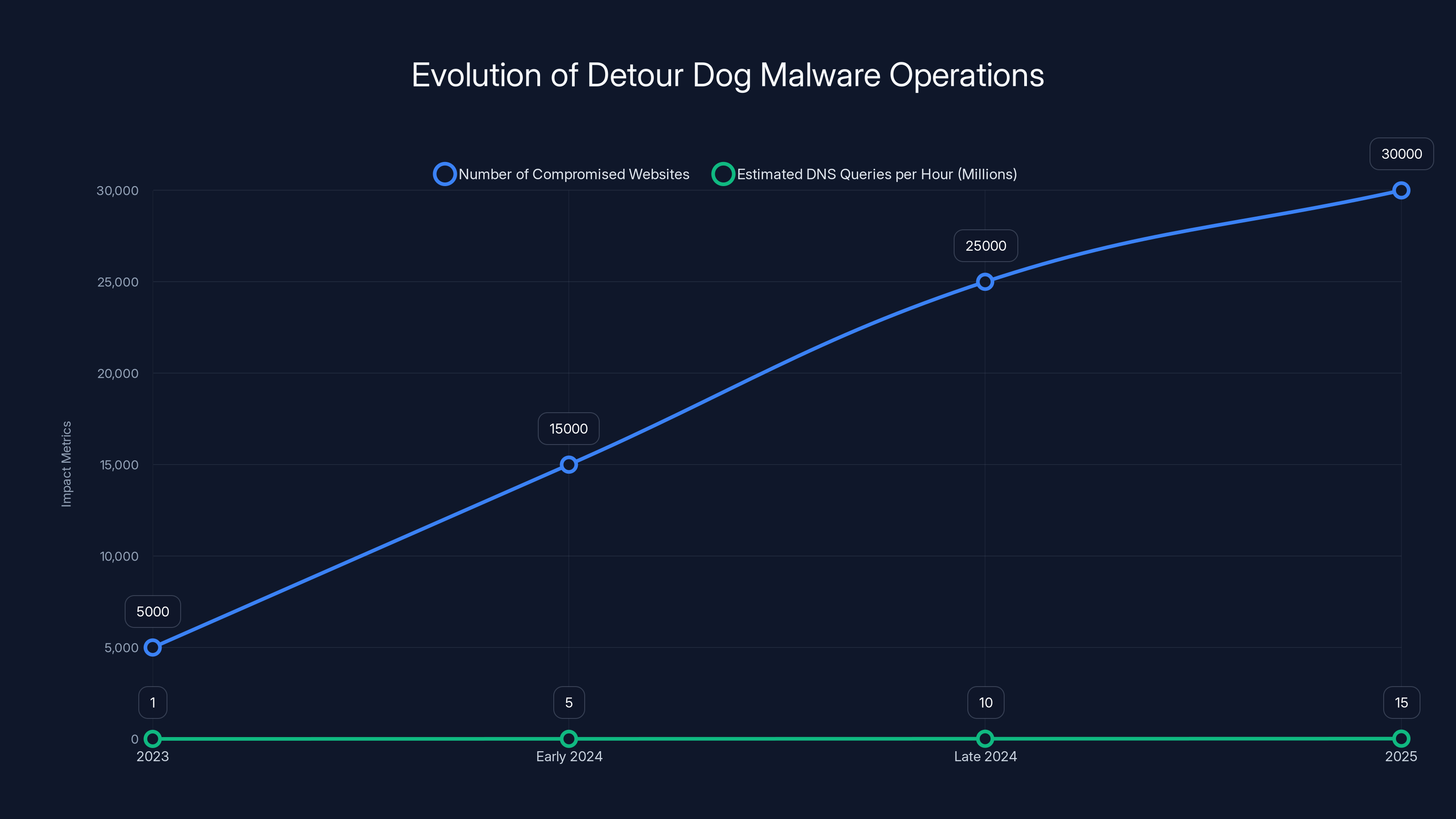

The numbers are staggering. More than 30,000 compromised websites are collectively generating millions of DNS queries every hour. Each query is a potential execution order for a cyber attack. And because the malicious logic runs entirely on the web server itself, it leaves zero footprint on victims' machines. Traditional antivirus software? Useless. Network monitoring tools? Blind. Endpoint detection? Missing the attack entirely.

This isn't just a technical problem for IT departments. It's a fundamental breakdown in how we trust the internet. If a website can silently compromise your data without you knowing, without security tools detecting it, and without leaving any evidence on your machine, then what does "safe browsing" even mean anymore?

In this comprehensive guide, we'll dissect how Detour Dog works, why it's so effective at evading detection, what its evolution from ad fraud to malware distribution tells us about the future of cyber threats, and most importantly, how to protect yourself and your organization from becoming another statistic.

TL; DR

- Detour Dog compromises 30,000+ websites using DNS manipulation to hide malware distribution and remain undetected for 12+ months

- DNS weaponization is the key trick: The malware uses DNS TXT records as a covert command channel, making attacks invisible to traditional security tools

- Evolution to info-stealing: The campaign evolved from ad-fraud scams to distributing Strela Stealer malware through email attachments and website compromises

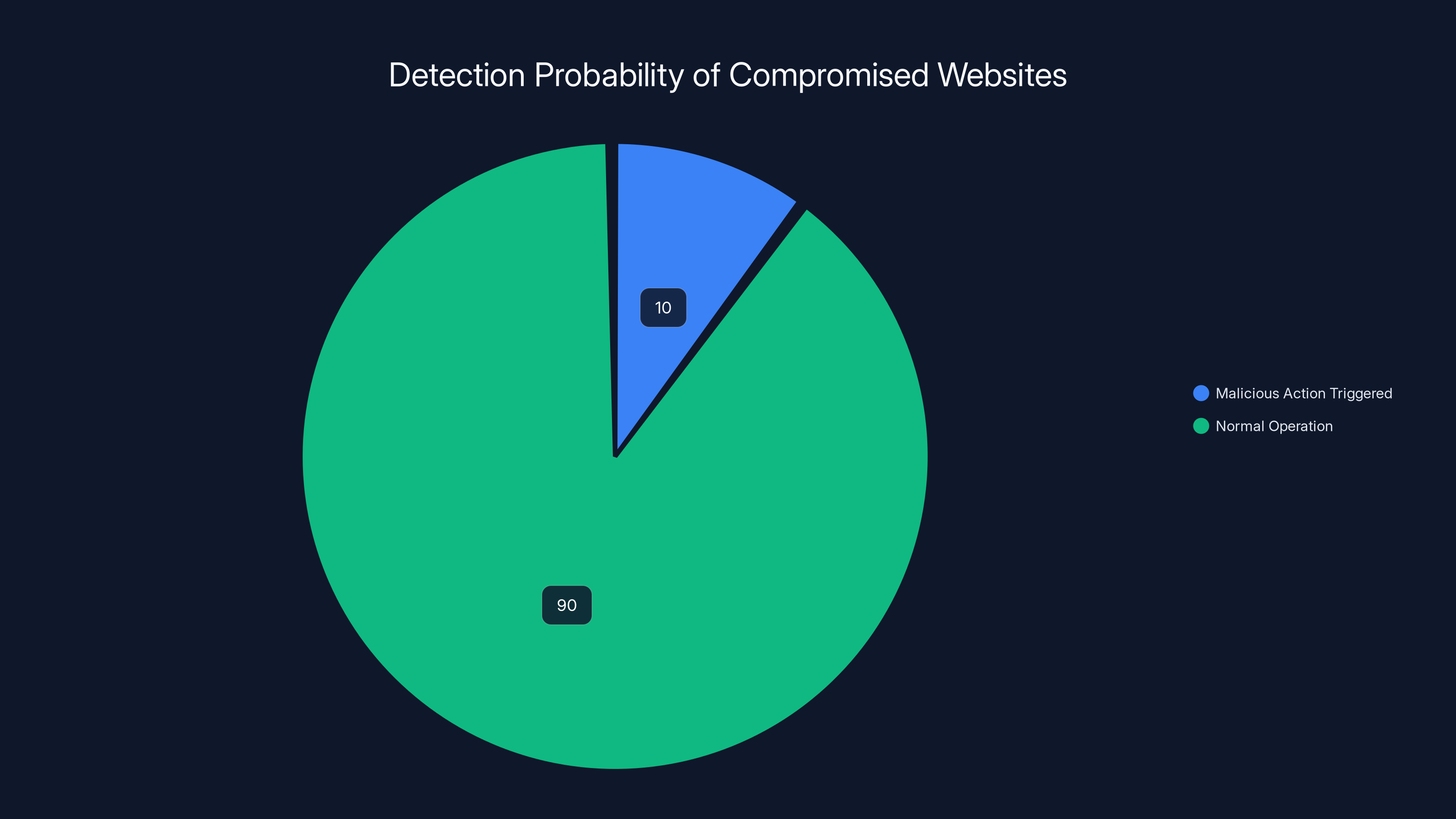

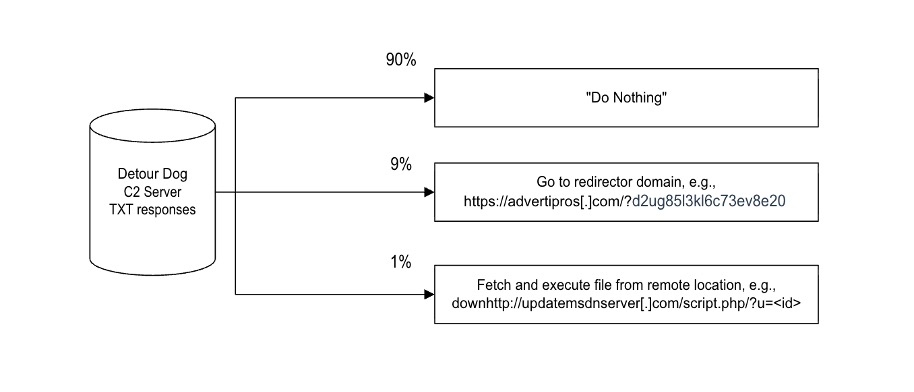

- Only ~10% of visits trigger malicious action, making reproduction and detection extraordinarily difficult for security researchers

- No machine-level traces exist, so antivirus software, endpoint detection, and traditional firewalls are ineffective against this attack vector

- Email remains the initial infection vector, with malicious attachments triggering the hidden DNS channel to fetch and execute payloads

Estimated data shows that only 10% of visits to compromised websites trigger malicious actions, making detection challenging.

What Is Detour Dog and Why Should You Care?

Detour Dog isn't a ransomware gang posting on dark web forums or a nation-state dropping zero-days. It's a sophisticated malware operation that discovered a loophole in how the modern internet works, then weaponized it with surgical precision. The name itself—given by security researchers—perfectly captures what the attack does: it hijacks legitimate websites to redirect users elsewhere, or worse, to silently steal their data.

At its core, Detour Dog represents a category of cyber threat that most organizations aren't prepared to defend against. It's not flashy. It doesn't announce itself. It doesn't encrypt your files or demand ransom. Instead, it quietly persists on infected sites, follows hidden commands transmitted through DNS, and systematically exfiltrates valuable data without ever needing to touch the victim's machine directly.

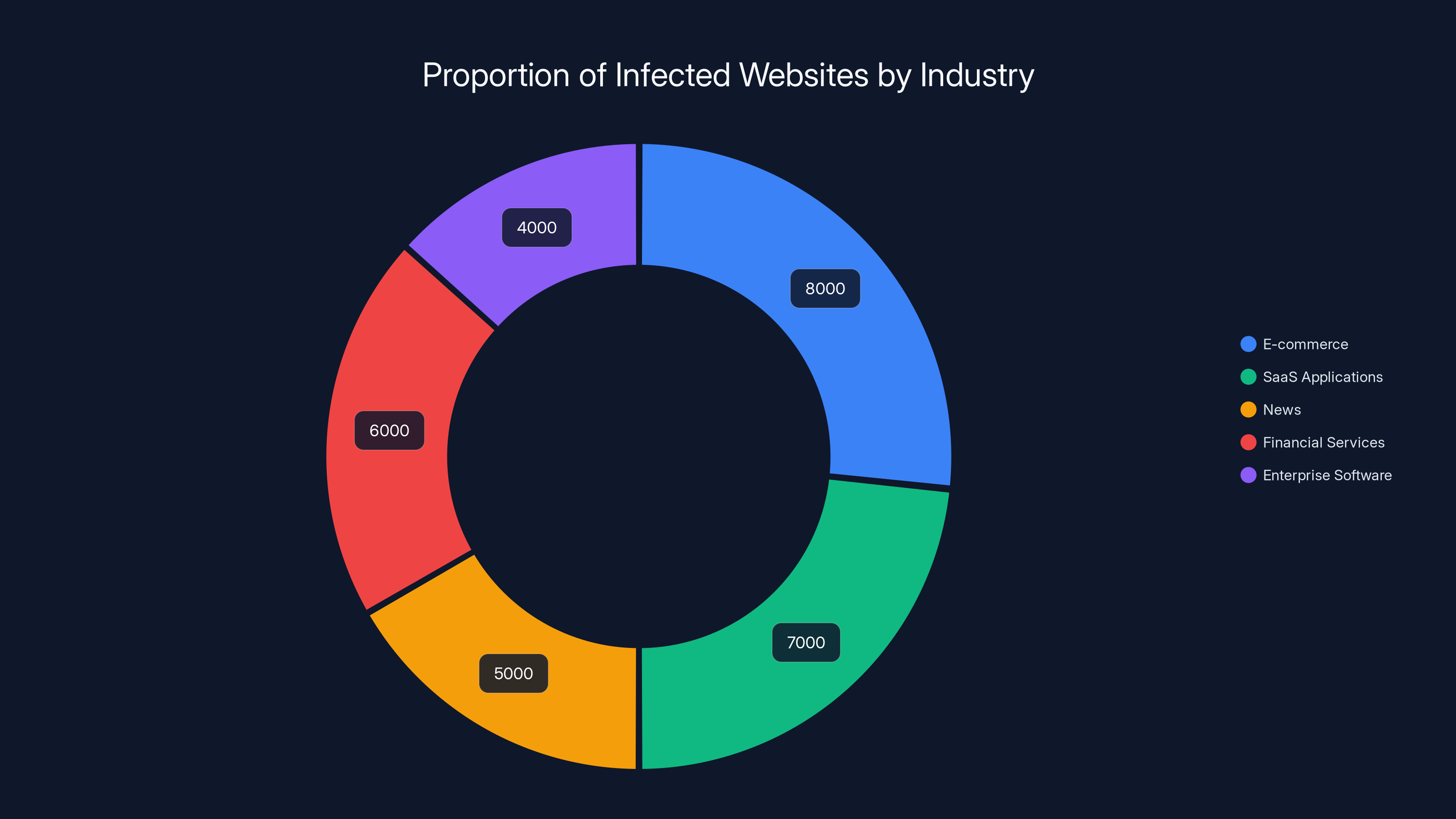

The operation has been documented infecting websites across multiple continents and industries. The list of compromised domains reads like a directory of normal, legitimate businesses: e-commerce platforms, SaaS applications, news websites, financial services sites, and enterprise software providers. Many of these site owners have no idea their infrastructure has been converted into a malware distribution point.

What makes Detour Dog matter isn't just its scale or stealth. It's what it represents about the evolving threat landscape. Attackers are increasingly moving away from obvious attacks that trigger security alerts and generate incident response incidents. Instead, they're discovering new ways to hide attacks in plain sight, leveraging legitimate infrastructure, and abusing fundamental internet protocols that we've trusted since the early 1990s.

For enterprises, this threat means that your firewall logs might show normal DNS traffic that's actually delivering malware. Your web proxy might be transparently passing along infected requests. Your endpoint protection team is staring at machines showing zero signs of infection because the malware never lived there. It's the perfect crime: hide the attack on someone else's infrastructure and let legitimate users unwittingly trigger the infection.

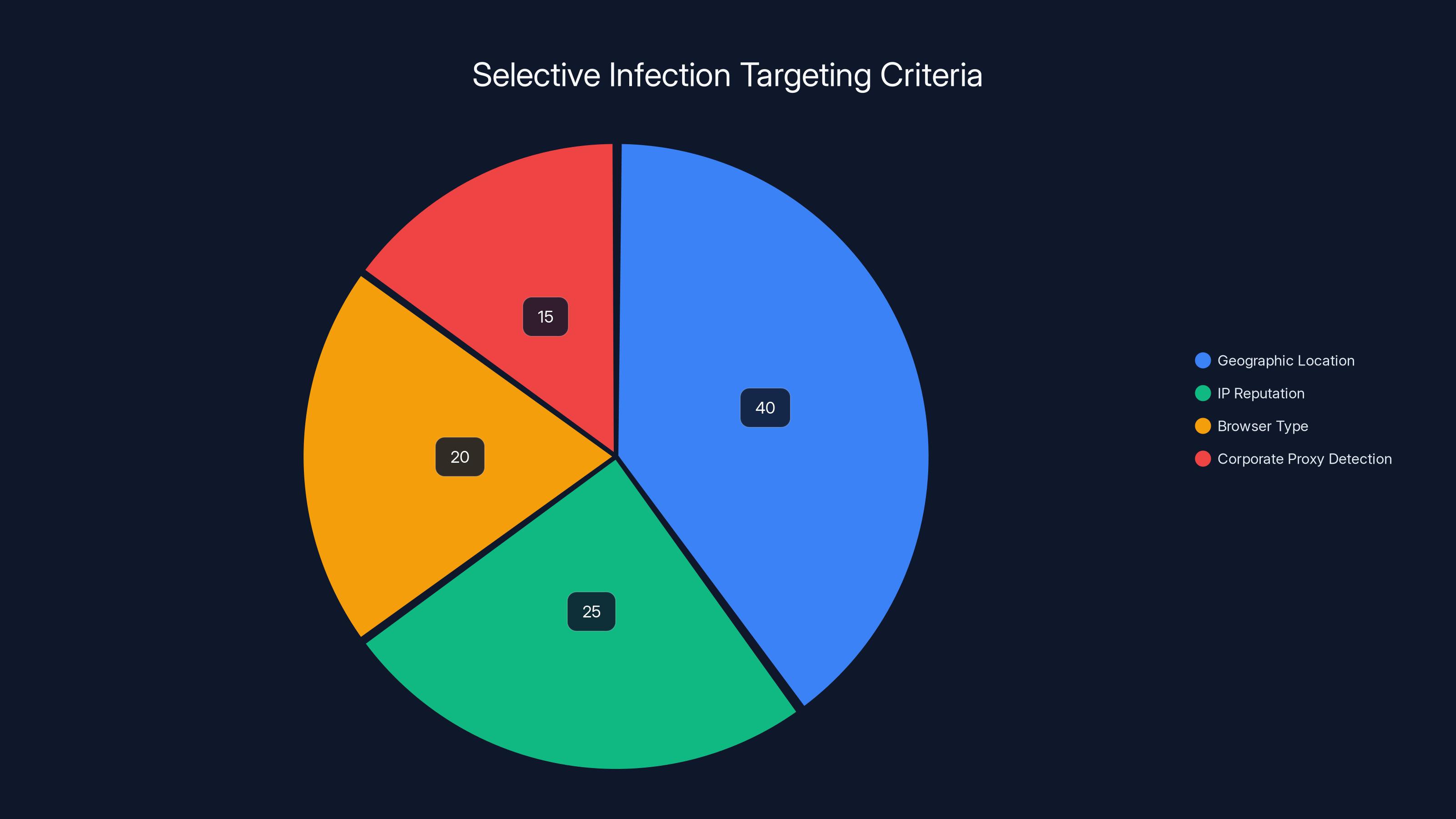

Detour Dog uses a mix of criteria for selective infection, with geographic location being the most significant factor. Estimated data.

How DNS Became a Weapon: The Technical Deep Dive

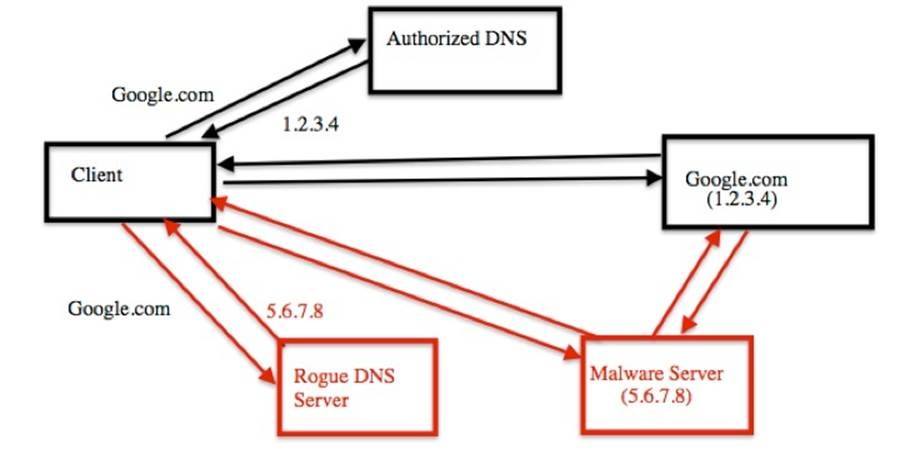

To understand how Detour Dog works, you first need to understand DNS. The Domain Name System is one of the internet's most fundamental protocols. Every time you type a website address into your browser, your computer sends a DNS query to a special server asking: "What's the IP address for this domain?" The DNS server responds with a number like 93.184.216.34, and your browser connects to that IP address to load the website.

DNS is fast, efficient, and everywhere. It's also largely trusted and rarely scrutinized because it seems like boring infrastructure. Most security monitoring ignores DNS queries unless they match known malicious domains. This is where Detour Dog found its opportunity.

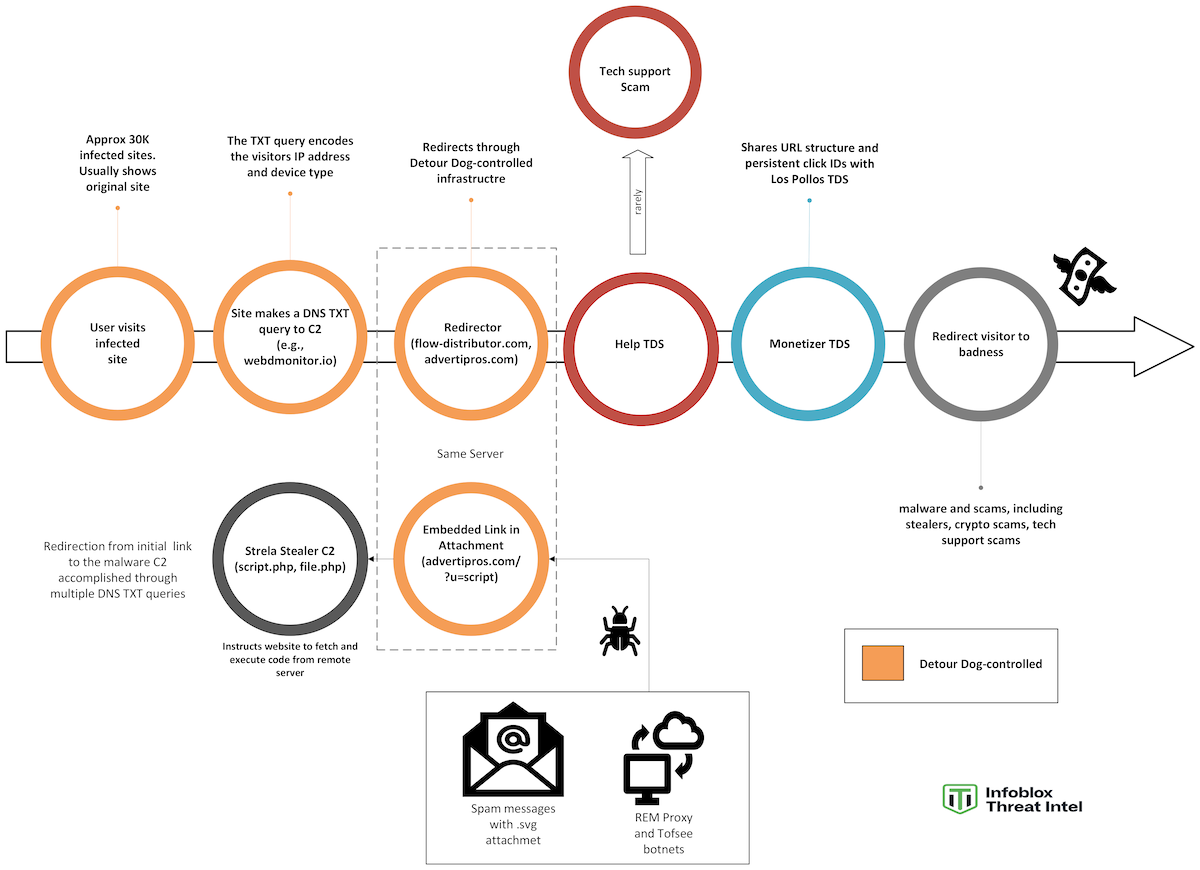

The attack works like this: First, attackers compromise a legitimate web server, typically through stolen credentials, unpatched vulnerabilities, or supply chain attacks. Once inside, they inject malicious code into the web application or server configuration. This injected code isn't typical malware that shows up as a suspicious process or file. Instead, it's a simple script that waits for specific conditions and then performs specific actions.

When those conditions are met (usually based on geographic location, browser type, or referrer data), the compromised web server makes a DNS query to an attacker-controlled nameserver. But instead of asking "what's the IP for this domain," it's actually sending a signal: "I've got a visitor that matches your targeting criteria." The query itself is disguised as a legitimate DNS lookup, perhaps asking to resolve a random subdomain or checking DNS records that any normal website might request.

The attacker's nameserver receives this signal and responds not with an IP address, but with a hidden instruction encoded in a DNS TXT record. TXT records are legitimate DNS entries designed for things like email verification (SPF, DKIM) or domain validation. Attackers abuse this feature by encoding instructions in those records. The code might say "do nothing," "redirect this user to a phishing site," "show them a fake CAPTCHA," or "fetch this payload from that URL."

Because all of this happens server-side, the victim's machine is completely unaware. The browser doesn't see the DNS query. The operating system doesn't log anything unusual. The endpoint detection tool sees only a normal HTTP request to a website that appears legitimate. But behind the scenes, the web server is following attacker commands encoded in DNS responses.

The genius of this technique lies in its invisibility. Traditional malware detection focuses on suspicious files, processes, network connections from victim machines, or obvious C2 (command and control) traffic. But Detour Dog's commands flow through DNS, which is so fundamental to internet operations that blocking or heavily monitoring DNS queries would break normal browsing. It's like trying to detect a secret code hidden in the structure of buildings in a city—the architecture itself becomes the attack vector.

The Evolution From Ad Fraud to Information Stealing

Detour Dog didn't start as the sophisticated malware distribution platform it is today. When researchers first began tracking this operation, it seemed almost mundane by comparison to other cyber threats. The compromised websites were redirecting visitors to various schemes designed to generate ad revenue or harvest clicks on fake CAPTCHAs. It was profitable but crude: trick people into clicking on ads, harvest their interaction data, and monetize the traffic.

For a long time, this is all Detour Dog appeared to do. The operation persisted on infected sites for months, quietly siphoning off traffic and ad revenue while site owners remained oblivious. The scale was impressive—thousands of sites, millions of redirects—but the threat level seemed relatively low compared to ransomware or data breaches.

Then, sometime around late 2024, the operation took a darker turn. The same infrastructure that had been used for ad fraud began accepting payloads from more dangerous threat actors. Researchers observed the delivery of Strela Stealer, an information-stealing malware that targets browser data, saved passwords, cookies, and other sensitive information. The malware was originally spread through phishing emails with malicious attachments, but the Detour Dog infrastructure provided a secondary distribution channel.

What changed wasn't necessarily the operation's leadership or goals. Instead, it appeared that the Detour Dog infrastructure had become valuable enough that other attackers were willing to pay for access to it. It's similar to how spam services evolved: at first, they're used by individual scammers for ad fraud, but eventually, they become a service sold to more sophisticated criminal organizations.

This represents a significant escalation in threat level. Ad fraud is annoying and costly, but information stealing is dangerous. Strela Stealer doesn't just capture what you're doing on a website—it systematically extracts stored browser credentials, meaning that if you've saved passwords in your browser, the malware gets them. It captures cookies, which can provide access to accounts without needing passwords. It collects browser history, bookmarks, and autofill data. For organizations, a successful Strela Stealer infection can be the foot-in-the-door that leads to data breaches, ransomware deployment, or account takeovers.

The shift from ad fraud to malware distribution also shows how criminal operations adapt when pressure increases. Once a particular attack vector becomes well-known and defenders start implementing countermeasures, attackers don't abandon the infrastructure—they find new ways to monetize it. Detour Dog's massive installed base of compromised websites was too valuable to waste on mere ad fraud, especially when more lucrative criminal enterprises were willing to pay for access.

Researchers also observed that the operation appears to be a service rather than a unified actor. The same Detour Dog infrastructure has been used to distribute payloads from different threat groups, including the notorious Hive 0145 gang. This suggests that Detour Dog might be operated as a platform—a malware distribution service that criminals can purchase access to, similar to ransomware-as-a-service or access brokers who sell compromised network credentials on underground forums.

Estimated distribution shows e-commerce and SaaS applications as the most affected industries, highlighting the broad impact of Detour Dog malware. Estimated data.

Why Detection Is Nearly Impossible: The Invisibility Factor

One of Detour Dog's most remarkable features is how difficult it is to detect. A typical malware infection leaves traces everywhere. Files appear on disk. Processes appear in task manager. Network connections to suspicious IPs appear in firewall logs. Antivirus signatures match against known malware. But Detour Dog leaves almost no evidence of infection on victim machines.

This is because the entire attack operates at the server level. The compromised website doesn't need to infect your computer to accomplish its goals. It simply follows instructions from the attacker, and those instructions might tell it to redirect you elsewhere, steal data through your browser, or inject a payload into the page you're viewing. None of this requires installing new software on your machine.

Consider the math: More than 30,000 websites are compromised, collectively generating millions of DNS queries per hour. Researchers estimate that only about 10% of visits to these sites trigger any malicious action. The other 90% see the site operating completely normally. This randomness or selectivity is intentional—it makes it much harder for security researchers to detect and reproduce the attack, and it also helps the attacker avoid triggering automated security monitoring that might flag unusual patterns.

A security researcher visiting an infected site might see nothing suspicious. A malware sandbox analyzing the site's response might see nothing suspicious. An endpoint detection system monitoring for suspicious processes might see nothing suspicious. The researcher would need to visit the same site 10 times, on average, before encountering the malicious behavior—and even then, they might not recognize it as malicious if it's just a redirect or a popup that appears legitimate on first glance.

Traditional antivirus software is essentially useless against this threat. Your antivirus is looking for files on your computer's disk that match known malware signatures. But Detour Dog doesn't create files on your disk. It sends commands through DNS and follows those commands server-side. Your antivirus never sees the attack because the attack is happening on someone else's server.

Network monitoring tools face a similar problem. They can see that a website made a DNS query, but DNS queries are so common and so fundamental to internet operation that flagging every unusual DNS query would create an avalanche of false positives and make the network unusable. How do you distinguish between a legitimate DNS query for a subdomain (which websites do all the time) and a Detour Dog malware command?

Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR) tools, which are designed to catch malware by monitoring suspicious processes and behaviors, also miss this attack entirely. Because the malware is operating on a web server, not on the victim's machine, EDR tools have nothing to monitor. The victim's machine isn't running any new processes. It isn't making suspicious network connections. From the EDR's perspective, the system is completely clean.

This invisibility is what makes Detour Dog so effective and so concerning. It represents a class of threats that traditional security architecture simply isn't designed to defend against. Most security approaches are built around the assumption that malware will try to do something obviously malicious on the target machine: create a file, spawn a process, connect to a suspicious IP. But what if the malware doesn't touch the target machine at all? What if it just uses legitimate website infrastructure to redirect you, inject content, or exfiltrate data through normal-looking HTTP requests?

The Email Attack Vector: How Initial Compromise Happens

While Detour Dog's detection is difficult because it operates server-side, the question remains: how do attackers first compromise these thousands of websites? The answer often lies in email.

In many cases, the attack chain begins with a phishing email. A site administrator receives a message that appears to come from a trusted vendor, service provider, or colleague. The email contains an urgent request or interesting document—maybe a software update, a payment invoice, a security report, or a vendor alert. The administrator opens the attachment or clicks the link, and that's where things go wrong.

The attachment might be a trojanized document that exploits a vulnerability in Microsoft Office, a PDF that triggers code execution through an unpatched reader, or a script disguised as a legitimate installer. Once opened, the malware runs with the privileges of the user who opened it. If that user is a system administrator or web developer, the malware gains access to the very infrastructure it needs to inject itself into the website.

Alternatively, the email might contain credentials—either phishing an administrator for their password, or containing stolen credentials from a previous breach of another service that the administrator reused. The attacker uses these credentials to log into a web hosting control panel, SSH into a server, or access an administrative interface, then injects malicious code directly.

Once inside, the attackers have several options for persistence. They might modify the web server configuration files to inject code into every page served. They might create backdoor accounts with administrative privileges. They might modify the application code directly if it's a managed CMS like WordPress. They might inject code into shared libraries or include files that every page loads. The specific method depends on the type of server and what access the attacker has.

The critical point is that once the website is compromised, the attacker doesn't need to maintain active access every day. They've injected persistent code that runs automatically whenever the web server starts. Even if the original vulnerability is patched, the injected code remains because it's part of the legitimate website code or configuration. The attacker can disappear for weeks or months, and the compromised code will continue running, quietly following orders transmitted through DNS.

This is why Detour Dog can persist on the same domain for over a year without detection. Unlike traditional malware that needs to be actively maintained and updated, Detour Dog's server-side code can lie dormant, checking in occasionally through DNS queries, waiting for instructions. When the attacker decides to activate it, the infrastructure is already in place.

The threat level of Detour Dog evolved significantly from 2020 to 2025, escalating from basic ad fraud to sophisticated information stealing. Estimated data.

The Command and Control Structure: Hidden Infrastructure

For Detour Dog to function at scale, the operation requires significant infrastructure. Thousands of compromised websites need to check in and receive commands. Those commands need to be managed, updated, and logged. Payloads need to be hosted, versioned, and served. All of this needs to happen while remaining invisible to security researchers and defenders.

The attacker's solution is elegant in its simplicity: use DNS infrastructure as the command and control channel. By encoding commands in DNS TXT records and having compromised websites query these records, the attacker creates a communication channel that looks indistinguishable from normal DNS traffic.

When a compromised website receives a visitor, it might generate a query like: query-abc 123-xyz 789.attacker-controlled-domain.com. To anyone monitoring DNS traffic, this looks like the website is trying to resolve a domain, which is completely normal. But the attacker-controlled nameserver for that domain receives the query, logs the timestamp and source IP, and responds with a TXT record containing encoded instructions.

The beauty of this design is that DNS traffic is rarely logged in detail and almost never analyzed for patterns. Your ISP logs DNS queries, but they're not analyzing them for malicious patterns—they're just using them to route traffic. Your corporate DNS server might log queries, but again, logging millions of queries per day creates noise that drowns out any signal. And because DNS responses are cached, the same instruction might be used for thousands of infected sites, making it hard to distinguish which instruction belongs to which attack.

The Detour Dog operation appears to use multiple attacker-controlled nameservers distributed across different hosting providers and geographic locations. This provides redundancy if one server is taken down, and it also makes it harder for defenders to block the operation by simply taking down one domain or IP address.

Commands transmitted through DNS TXT records are typically short—just a few bytes of encoded data. This keeps queries fast and makes them less likely to trigger intrusion detection systems that look for unusually large or malformed DNS packets. The encoding might use simple obfuscation like base 64 or hexadecimal encoding, or it might use more sophisticated methods to disguise the payload.

Interestingly, the command and control structure doesn't need to be highly sophisticated. Unlike traditional botnets that need to manage thousands of machines, handle updates, and avoid being detected by ISPs blocking suspicious outbound connections, Detour Dog's infrastructure only needs to generate DNS responses to legitimate queries. The infected websites do the heavy lifting of interpreting commands and deciding what actions to take.

Geographic Targeting and Selective Infection

One of the most sophisticated aspects of Detour Dog is its targeting logic. The operation doesn't activate on every visit to an infected website. Instead, it selectively chooses which visitors to target based on geographic location, IP reputation, browser type, and other factors.

This selectivity serves multiple purposes. First, it reduces the risk of the malware being detected. If every visitor to an infected site got malicious content, it would be trivial to spot—someone would just visit the site, get attacked, run antivirus, and report the infection. But if only 10% of visitors see the attack, most people will have a normal browsing experience and never realize the site is compromised.

Second, it helps the attacker focus on high-value targets. If the goal is to steal credentials from users in developed countries where corporate workers are more likely to have valuable access and high-privilege accounts, the attacker can focus malicious redirects on IP addresses from those regions. If the goal is to harvest information from specific companies, the attacker can target those company's IP address blocks.

Third, it helps evade automated detection systems. Many corporate networks use web proxies or firewalls that automatically visit websites to check for malicious content. By detecting these proxy requests and serving benign content, the attacker ensures that the corporate security tool sees a clean website and doesn't flag it as dangerous.

The targeting logic runs on the compromised web server itself, analyzing the incoming HTTP request before deciding whether to activate the malicious behavior. The attacker can see the visitor's IP address, user agent (which indicates browser type), HTTP headers (which might contain corporate proxy information), and referrer (which indicates whether the link came from a search engine, social media, or email). Based on these signals, a simple decision tree determines whether to serve normal content or activate the malware.

Researchers investigating Detour Dog found evidence that some variants use geolocation databases to identify visitors' countries and selectively target only visitors from certain regions. Other variants check whether the visitor's IP belongs to known cloud hosting providers (which would indicate an automated scanner or researcher) and serve benign content to those visitors while saving the malicious version for real users.

This targeting logic also explains why reproduction is so difficult. A security researcher in one country might visit the infected website from their office IP and see nothing suspicious. A researcher in another country might visit the same website and trigger the malware. The inconsistency makes it hard to determine whether the website is actually infected or whether the researcher is seeing coincidental behavior.

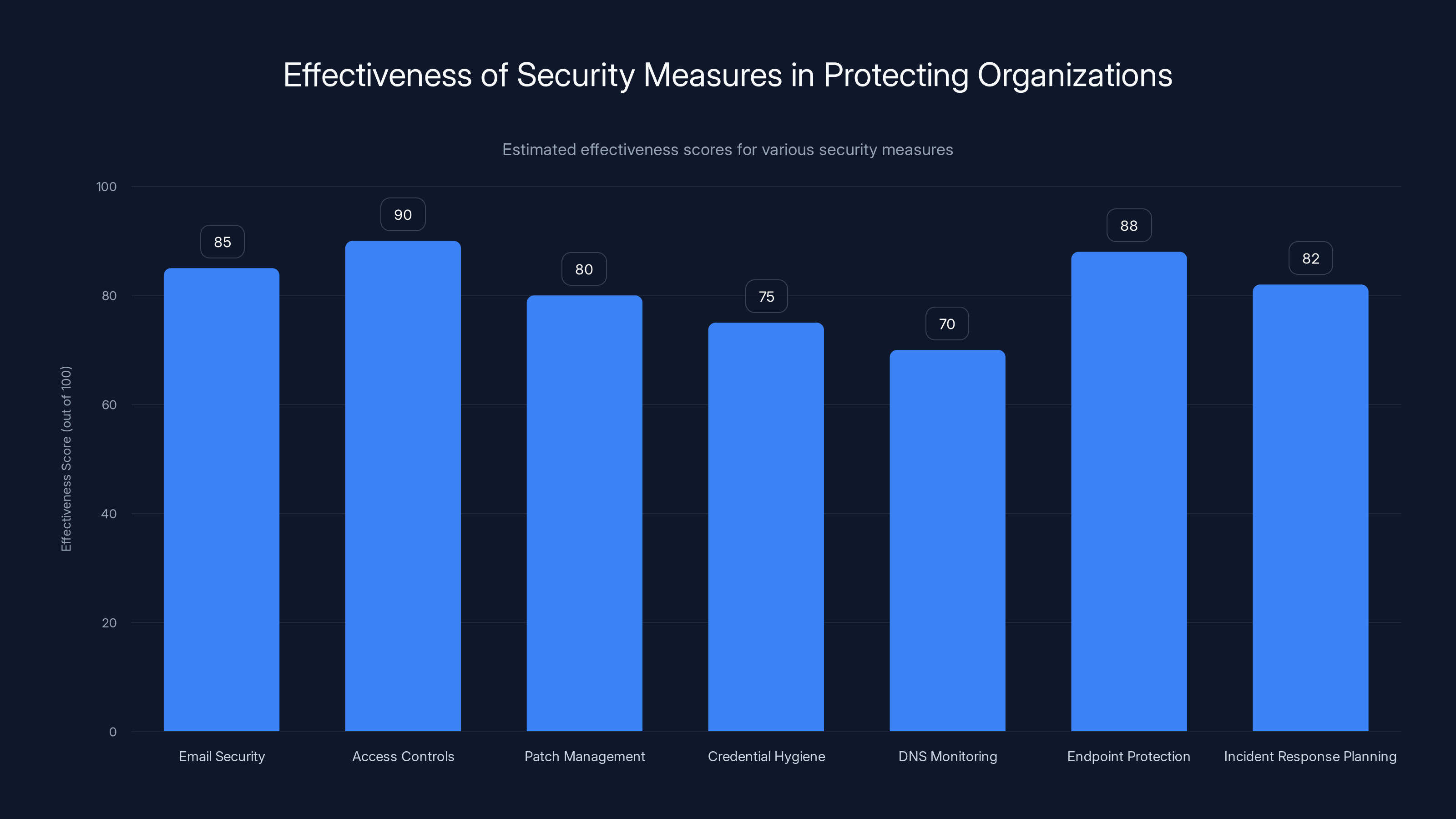

Implementing a multi-layered security approach can significantly enhance an organization's protection against threats. Estimated data suggests access controls and endpoint protection are among the most effective measures.

The Scale of Compromise: 30,000+ Websites and Counting

When security researchers first quantified the scale of Detour Dog, the numbers were shocking: more than 30,000 legitimate websites infected with the malware. That's not a handful of sites. That's not even hundreds of sites. That's tens of thousands of websites, many of them well-established, trusted domains that millions of people visit every day.

To put this in perspective, consider that the total number of websites on the internet is estimated at around 1.8 billion. But only about 200 million of those are actively maintained and regularly visited. If 30,000 of the world's actively used websites are infected with Detour Dog, that means roughly 0.015% of all websites are compromised. For specific geographic regions or industries, that percentage might be much higher.

The infected websites span multiple industries: e-commerce platforms where people shop, SaaS applications where people work, news websites where people get information, financial services sites where people manage money, and enterprise software providers where organizations run critical operations. The diversity of infected sites suggests either that the attacker is not particularly selective (and just compromises whatever sites they can get into) or that the Detour Dog infrastructure is sold as a service to multiple attackers with different targeting priorities.

The operation's reach is global. Researchers have documented infected websites in North America, Europe, Asia, and other regions. This suggests either a well-organized operation with global infrastructure and multiple attack teams, or a malware-as-a-service model where the infrastructure is sold to various threat groups who use it independently.

The scale also has implications for defenders. If 30,000 websites are compromised, and each site receives thousands of visitors per day, then tens of millions of people are potentially passing through Detour Dog-infected websites every day. Even if only 10% of those visitors are targeted and only 10% of those targeted visitors successfully get infected, that's still potentially hundreds of thousands of infections per day.

Moreover, because Detour Dog's initial infection vector often involves email, many of those infected users might not immediately show symptoms. They might receive an email, open a malicious attachment, get silently compromised, and continue working normally for weeks or months while their credentials are stolen. By the time they discover the infection, the attacker already has everything they need.

The Millions of DNS Queries: A Signal in the Noise

One of the pieces of evidence that helped researchers identify the scope of Detour Dog was the volume of DNS queries being generated. The operation was sending millions of DNS TXT record queries per hour, all of them destined for attacker-controlled nameservers.

On the surface, millions of queries might not sound unusual for a large operation. After all, any website with millions of daily visitors will generate millions of HTTP requests. But DNS queries are different. A typical website doesn't generate millions of DNS queries per hour. When a website needs to look something up—check a domain's IP address, fetch email records, verify domain ownership—it does so, but not at that scale or frequency.

Moreover, most of these queries were for subdomains that didn't exist or that didn't correspond to any legitimate purpose. Security researchers could see queries for random-looking subdomains hitting attacker-controlled nameservers. While each individual query looked innocuous, the aggregate pattern was diagnostic of something wrong.

The DNS query volume also had an interesting temporal pattern. Queries would spike during business hours in certain time zones, then drop off during nights and weekends. This suggested that the queries were correlated with legitimate website traffic—more website visitors meant more DNS queries checking in with the attacker's infrastructure. This pattern made it possible to estimate the scale of infection by correlating the DNS query volume with the number of unique visitor IPs.

From a detection perspective, this demonstrates both the power and limitation of analyzing aggregate network traffic patterns. While individual DNS queries from a compromised site might look normal, analyzing millions of queries across thousands of sites can reveal patterns that indicate something anomalous is happening. However, for any individual organization or ISP, the volume of DNS queries might be too small to stand out from the normal background noise.

The Detour Dog malware operation has significantly expanded from 2023 to 2025, with the number of compromised websites growing from 5,000 to over 30,000 and DNS queries reaching 15 million per hour. (Estimated data)

Email Attachment Delivery: The Strela Stealer Connection

While Detour Dog's primary mechanism is the compromised website infrastructure, the delivery of Strela Stealer malware demonstrates how multiple attack vectors can be combined into a single campaign. Strela Stealer is typically distributed through phishing emails containing malicious attachments, but by connecting it to the Detour Dog infrastructure, attackers created a secondary distribution channel and increased the likelihood of successful infections.

The attack flow works like this: A targeted user receives a phishing email that appears to come from a trusted source. The email contains an attachment—perhaps a PDF document, a spreadsheet, a Word document, or a ZIP file containing what appears to be an installer or update. The attachment is designed to exploit a known vulnerability or to use social engineering to convince the user to open it or enable macros.

When the user opens the attachment on a Windows machine, Strela Stealer executes. The malware immediately begins working to hide itself and avoid detection. It disables Windows Defender, removes itself from Task Scheduler, and hides its processes from standard system monitoring tools. It modifies registry keys to disable security warnings and startup scan.

Once established, Strela Stealer begins its primary mission: exfiltrating browser data. It accesses the Chrome, Edge, and Firefox password stores and extracts all saved passwords. It pulls session cookies, which provide access to accounts without needing passwords. It extracts browser history, bookmarks, and autofill data. All of this information is collected and prepared for exfiltration.

But where does the Detour Dog connection come in? In some cases, infected machines are instructed to visit a Detour Dog-compromised website. The malware then uses the compromised website's DNS-based command channel to receive instructions for where to send the stolen data. This creates a multi-hop exfiltration path: compromised computer sends stolen data to legitimate website, legitimate website uses DNS to contact attacker infrastructure, attacker infrastructure provides instructions for final delivery destination.

This approach has advantages for the attacker. First, it obfuscates the final destination of the stolen data. Forensic analysts might see the compromised computer sending data to a legitimate website, which looks normal. They might not realize that the legitimate website is acting as a proxy. Second, it provides flexibility. The attacker can change where data is ultimately sent without needing to update malware on infected machines—just change the DNS response.

For defenders, this combination of attacks is particularly challenging. Email security needs to detect malicious attachments. Endpoint detection needs to catch Strela Stealer. Network monitoring needs to detect exfiltration. But if any single layer fails, the attack succeeds. And because the attack uses legitimate websites and DNS, it's easy for individual layers to miss the complete picture.

The Supply Chain Angle: Malware-as-a-Service

One of the most significant aspects of Detour Dog is evidence that it operates as a service. The same infrastructure has been used to distribute payloads from multiple different threat groups, including the notorious Hive 0145 gang. This suggests that Detour Dog might not be a unified criminal organization executing a single campaign, but rather a platform that's offered to multiple attackers.

This model resembles other malware-as-a-service (MaaS) offerings that have become increasingly common in recent years. Just as ransomware-as-a-service allows criminal groups to launch attacks without building their own infrastructure, Detour Dog-as-a-service allows different attackers to leverage the compromised websites without needing to compromise them themselves.

The economics of this model make sense. Setting up and maintaining a network of 30,000 compromised websites requires significant effort, expertise, and resources. It requires staying current with vulnerability research, developing infection techniques for multiple platforms, and managing the operational security of the infrastructure. For individual criminals, this might not be worthwhile. But if the infrastructure is shared among multiple customers, the costs can be amortized across many attackers.

In this model, the Detour Dog operator acts as an infrastructure provider. They compromise websites and establish persistence through malicious code injection. They set up the DNS command and control infrastructure. They manage payment processing and customer authentication. Their customers—other threat groups—can then use the infrastructure to distribute their own malware, harvest data, or redirect traffic.

This also explains the evolution from ad fraud to information stealing. When the infrastructure was profitable enough with just ad fraud, the operator didn't need to take on additional risk by supporting more serious crimes. But as ad fraud became less profitable or as the risk of continued operation increased, offering the infrastructure to other attackers for higher fees made business sense.

The supply chain angle also has implications for attribution and response. It's much harder to track a single unified campaign when multiple independent threat groups are using the same infrastructure. A breach attributed to one group might actually be traced back to the Detour Dog platform. Shutting down the platform would require coordinated effort from law enforcement and security researchers across multiple countries and jurisdictions.

Detection and Response: Challenges for Defenders

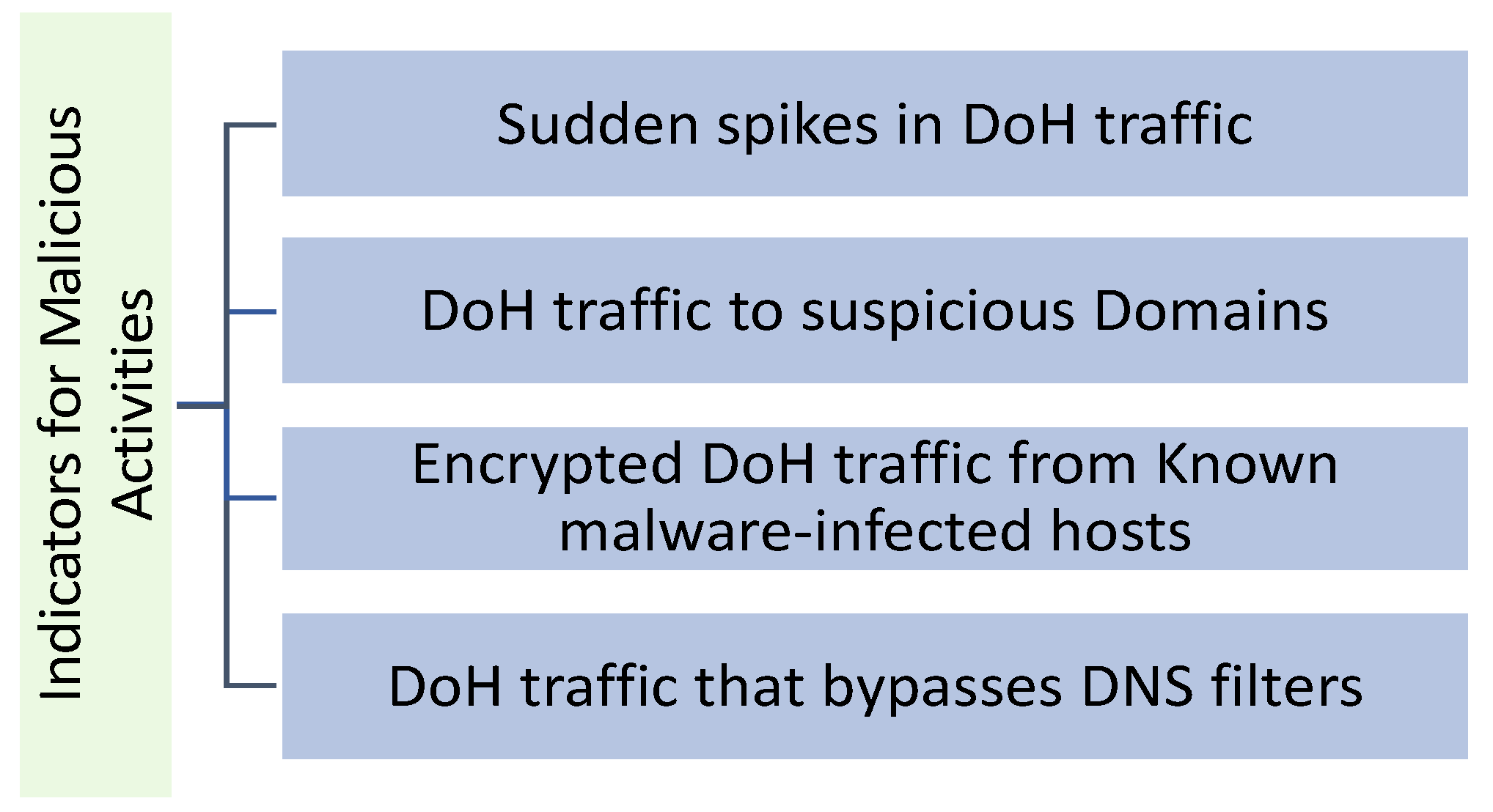

For organizations trying to detect and respond to Detour Dog, the challenges are significant. Traditional security tools aren't designed to catch attacks that operate entirely at the web server level and leave no traces on client machines.

However, defenders do have options. The first is monitoring for DNS query patterns. If you manage a web server, you should be logging all DNS queries made by that server and analyzing them for patterns. Are there queries for subdomains that don't correspond to legitimate purposes? Are there queries to nameservers outside your organization's normal DNS infrastructure? These can be signs of compromise.

The second is integrity monitoring. File integrity monitoring tools like AIDE, Tripwire, or commercial solutions can detect when files on your web server are modified. While Detour Dog's injected code might be added to legitimate files rather than creating new files, it will still change the hash of those files. Regular integrity checks can detect this.

The third is web application firewalls and traffic analysis. Modern WAF solutions can sometimes detect when a web server is making unusual DNS queries or outbound connections. They can also detect anomalous patterns in server behavior that might indicate compromise.

The fourth is threat hunting. Rather than waiting for automated tools to detect the attack, security teams can proactively search for it. This might involve analyzing web server logs for patterns, examining server configuration files for injected code, or reviewing network traffic for signs of DNS exfiltration.

The most critical step, however, is prevention. Ensure that your web servers are kept fully patched and updated. Implement strong access controls for server administration. Use multi-factor authentication for critical administrative accounts. Monitor administrative logins for suspicious activity. Implement email security controls to prevent phishing attacks that lead to server compromises.

What Victims Experience: The Real-World Impact

From the perspective of a regular internet user, a Detour Dog compromise might be virtually undetectable. You visit a website, click around, maybe make a purchase, and everything feels normal. You don't realize you were targeted by an infection attempt. If you opened an email attachment or the malware tried to download a payload and failed (due to having a different browser version, operating system, or being behind a corporate proxy), you might never know you were attacked.

But for users who were successfully compromised, the impact can be severe. A user infected with Strela Stealer might not notice anything immediately. Their computer runs normally. Their applications work normally. But in the background, all of their browser passwords have been exfiltrated to attacker-controlled servers.

Days or weeks later, the first sign of compromise might be fraudulent activity on one of those accounts. A user might notice unauthorized purchases, password changes, or unusual login activity. By that point, weeks of data has already been stolen, and the attacker has had time to use the credentials for more serious attacks.

For businesses, the impact is worse. If an employee's credentials are stolen, the attacker might use them to access corporate systems, steal intellectual property, or install additional malware deeper in the network. An attacker with access to a developer's account might modify source code repositories. An attacker with access to an administrator's account might create backdoor accounts for persistent access.

The financial impact can be severe. A single compromised account for someone with access to sensitive systems might lead to a breach affecting thousands of customers or millions of dollars in fraud. The cost of incident response, notification, regulatory fines, and business interruption can dwarf the initial cost of the infection.

For many users and organizations, the most damaging aspect of Detour Dog is that they won't know they've been compromised until long after the attack has succeeded. Traditional security controls that detect and alert on malware infections won't work here. The user's machine will appear clean. The organization's monitoring systems will see nothing unusual. By the time the compromise is discovered, the damage is done.

Protecting Your Organization: Practical Steps

While Detour Dog represents a sophisticated threat, organizations can take concrete steps to reduce their risk. The approach should be multi-layered, addressing different aspects of the attack chain.

Email Security: Implement advanced email security solutions that can detect and block phishing emails with malicious attachments. Use email authentication (SPF, DKIM, DMARC) to prevent attackers from spoofing your organization's domain. Train employees to recognize phishing attempts and establish a clear process for reporting suspicious emails.

Access Controls: Use multi-factor authentication (MFA) for all critical accounts, especially administrative accounts that can access sensitive systems or deploy software. Implement the principle of least privilege, ensuring that users and systems have only the access they need for their legitimate work.

Patch Management: Keep all systems fully patched and updated. Many initial infections result from known, patched vulnerabilities. Implement a formal patch management process with testing and deployment tracking.

Credential Hygiene: Don't reuse passwords across multiple services. Use a password manager to generate and store unique, complex passwords for each service. Enable credential guard or similar protections on Windows systems to protect stored credentials.

DNS Monitoring: Monitor DNS queries from systems on your network for unusual patterns. Look for queries to unfamiliar nameservers, queries for subdomains that don't correspond to legitimate purposes, or excessive queries for TXT records.

Endpoint Protection: Use modern endpoint detection and response (EDR) tools that can detect malware behavior even when traditional signatures don't match. These tools analyze behavior to identify suspicious activities.

Incident Response Planning: Develop and regularly test an incident response plan. Know what you'll do if you discover a compromise, who you'll notify, and how you'll investigate. Have procedures in place for quickly containing infections and preventing lateral movement.

Threat Intelligence: Subscribe to threat intelligence feeds that provide information about known malicious infrastructure, including information about Detour Dog and similar operations. Use this information to tune your security controls and educate your team.

The Future of DNS-Based Attacks

Detour Dog likely won't be the last malware operation to weaponize DNS or to abuse legitimate website infrastructure as an attack vector. As traditional attack methods become increasingly defended, attackers will continue innovating and finding new ways to hide their activities.

We're likely to see more attacks that abuse fundamental internet protocols. Email has been weaponized extensively, but DNS, NTP, DHCP, and other protocols that are typically trusted and rarely scrutinized represent new frontiers for attacks. We might see attacks that abuse DNSSEC infrastructure, that exploit DNS caching mechanisms, or that leverage DNS rebinding to bypass same-origin policies in web browsers.

We're also likely to see more attacks that distribute the malicious logic across multiple legitimate services and infrastructure. Rather than using a single compromised website, attackers might use a combination of compromised legitimate websites, cloud services, and legitimate APIs to accomplish their goals. This would make it even harder to detect the attack because no single component would be obviously malicious.

The evolution of malware from obvious, noisy attacks to invisible, stealthy attacks is a long-term trend that will continue. Attackers have learned that getting caught is bad for business. Attacks that trigger alerts, that cause damage to reputation, that lead to incident response and law enforcement involvement are ultimately unsuccessful from a business perspective. Attacks that quietly steal data or maintain persistence for long periods, that avoid detection by security tools, and that leverage legitimate infrastructure are far more profitable.

This means that defenders need to evolve their approach. Signature-based detection is becoming increasingly ineffective. Behavior-based detection and threat hunting are becoming essential. The ability to analyze aggregated data across multiple sources and identify patterns that indicate compromise is becoming a critical skill.

Organizations also need to recognize that the threat landscape has changed. The assumption that "if our security tools haven't detected anything, we're safe" is no longer valid. Organizations need to implement processes for proactively searching for compromises, analyzing indicators of compromise from threat intelligence sources, and responding quickly when evidence of compromise is discovered.

The Broader Security Implications: Trust is Eroding

Perhaps the most significant implication of Detour Dog is the erosion of trust in the internet infrastructure. We've always assumed that legitimate websites are, by definition, safer than suspicious websites. If a site has a good reputation, has been around for years, and appears to be properly maintained, we trust it.

But Detour Dog demonstrates that legitimate websites can be compromised and weaponized. A site's history and reputation don't guarantee its safety. The site you think you're visiting might have been secretly infected for months, and you'd never know it.

This has implications for everyone. For users, it means that no website should be absolutely trusted. Even well-known, reputable sites might harbor malware. Basic security practices like keeping systems patched, avoiding opening suspicious attachments, and maintaining separate passwords for different sites become even more critical.

For organizations, it means that security strategies that rely primarily on trusted lists of "safe" sites are inadequate. Advanced threats operate with the assumption that the defender is actively looking for them, and they've adapted accordingly.

For security vendors, it means that traditional antivirus and endpoint protection are insufficient. Users need defense-in-depth approaches that include email security, DNS monitoring, behavioral analysis, and threat hunting.

For internet infrastructure providers and law enforcement, it means that taking down a single malware operation requires coordination and effort proportional to the operation's sophistication and scale. Detour Dog's use of legitimate website infrastructure and DNS protocols means that defenders can't simply block a malicious IP address or take down a C2 server.

The broader lesson is that security is not a destination but an ongoing process. As attackers innovate and discover new ways to hide attacks, defenders need to innovate as well. This requires constant learning, adaptation, and investment in security capabilities.

Conclusion: The New Normal

Detour Dog represents a new chapter in the evolution of cyber attacks. It demonstrates that the most dangerous attacks are often the ones you never see. It shows that legitimate infrastructure can be weaponized against you. It proves that traditional security tools are sometimes useless against modern threats.

But it also demonstrates something important about security: that threats are always evolving, and defenders need to evolve with them. The good news is that while Detour Dog's invisibility makes it difficult to detect, the attack is not impossible to stop. Organizations that implement defense-in-depth approaches, that actively hunt for compromises, and that invest in understanding their own infrastructure have a much better chance of detecting and preventing attacks like this.

The reality is that we're in an era where passive security isn't enough anymore. Simply running antivirus and relying on firewalls to block obviously malicious traffic isn't sufficient. Organizations need to assume that sophisticated attackers are actively trying to compromise their systems and that some attacks will get through. The focus needs to shift from prevention alone to detection and response.

For security practitioners, this is both a challenge and an opportunity. The challenge is that threats continue to evolve and become more sophisticated. The opportunity is that by understanding how attacks like Detour Dog work, we can better prepare our defenses and respond more effectively when we encounter similar threats in the future.

The most important thing individuals and organizations can do right now is awareness. Understand that threats like Detour Dog exist. Understand that your organization might be vulnerable. Understand that even reputable websites might be compromised. Then take action to protect yourselves, monitor for signs of compromise, and respond quickly if you suspect an attack.

Detour Dog won't be the last invisible, sophisticated malware operation. But by learning from it, by understanding how it works, and by implementing proper defenses, we can reduce the impact of similar attacks in the future.

FAQ

What is Detour Dog malware?

Detour Dog is a sophisticated malware operation that compromises legitimate websites and weaponizes the DNS protocol to distribute malware, steal information, and redirect users without leaving traces on their machines. The malware uses DNS TXT records as a covert command channel, allowing attackers to control compromised websites and deliver payloads like Strela Stealer information-stealing malware while remaining invisible to traditional security tools.

How does Detour Dog infect websites?

Detour Dog typically initiates infections through phishing emails containing malicious attachments that exploit vulnerabilities or social engineering to compromise administrative credentials. Once attackers gain access to web servers through stolen credentials or exploited vulnerabilities, they inject persistent malicious code into the server configuration or application files, allowing the code to execute automatically whenever the server runs. This persistence can remain undetected for months or years unless actively discovered through integrity monitoring or code audits.

Why is Detour Dog so difficult to detect?

Detour Dog operates entirely on the compromised web server and uses DNS for command and control, leaving no traces on victim machines. Traditional antivirus software looks for files and processes on your computer, but Detour Dog's attack happens server-side and flows through DNS, which is so fundamental to internet operation that unusual DNS queries are rarely flagged. Only about 10% of website visits trigger malicious behavior, making it extremely difficult for security researchers to reproduce the attack even when visiting infected sites.

What is Strela Stealer and how is it connected to Detour Dog?

Strela Stealer is an information-stealing malware typically distributed through phishing emails with malicious attachments. It extracts browser passwords, cookies, and other sensitive credentials. Detour Dog's infrastructure has been leveraged to distribute Strela Stealer by serving as a secondary delivery platform and using its DNS command channel to relay stolen data through compromised legitimate websites, creating a multi-hop exfiltration path that obscures the final destination of stolen information.

How many websites are infected with Detour Dog?

Researchers documented more than 30,000 legitimate websites compromised by Detour Dog, collectively generating millions of DNS queries per hour. These websites span multiple industries including e-commerce, SaaS applications, news outlets, and financial services. The scale of infection is global, with infected sites identified across North America, Europe, Asia, and other regions.

How can I protect myself from Detour Dog?

Protect yourself by maintaining strong email security practices such as being cautious about opening unexpected attachments, using unique passwords with a password manager, enabling multi-factor authentication on important accounts, and keeping your operating system and applications fully patched. For organizations, implement comprehensive defenses including advanced email security, endpoint detection and response tools, DNS monitoring, file integrity monitoring on web servers, and regular security audits and threat hunting activities.

Is Detour Dog a single organization or a service?

Evidence suggests Detour Dog operates as a malware-as-a-service platform rather than a single unified organization. The same infrastructure has been used to distribute payloads from multiple different threat groups including the Hive 0145 gang, indicating that the Detour Dog operator provides the compromised website infrastructure and DNS command channel to multiple customers who use it independently for their own attacks. This model allows the operator to amortize the costs of maintaining the infrastructure across many attackers.

What DNS records does Detour Dog abuse?

Detour Dog primarily abuses DNS TXT records, which are legitimate DNS entries designed for email authentication (SPF, DKIM, DMARC) and domain verification. Attackers encode hidden commands and instructions in these TXT records, and when compromised websites query the attacker's nameservers, they receive these encoded commands that determine whether to show benign content, redirect the visitor, or fetch a malware payload. This abuse of legitimate DNS record types makes the attack appear as normal DNS traffic.

Can traditional antivirus software detect Detour Dog?

Traditional antivirus software is essentially ineffective against Detour Dog because the malware operates entirely on the compromised web server and never needs to install files or create processes on the victim's machine. Antivirus tools scan files on your computer's disk and monitor processes running locally, but Detour Dog's attack happens server-side at the website infrastructure level. This is why modern endpoint detection and response (EDR) tools and network-level monitoring are more effective than traditional signature-based antivirus.

How does Detour Dog's selective targeting work?

Detour Dog's injected server-side code analyzes incoming HTTP requests to determine which visitors to target, using indicators like geographic location, IP reputation, browser type, and HTTP headers. This selectivity means that only about 10% of website visitors trigger malicious behavior, while the other 90% see completely normal, benign content. The targeting logic also helps the operation avoid automated security tools and research by serving benign content to detected proxies and security scanners while reserving attacks for real users.

Key Takeaways

- Detour Dog compromises 30,000+ legitimate websites to distribute malware and steal data while remaining invisible to traditional security tools

- The malware weaponizes DNS TXT records as a covert command channel, making attacks look like normal internet traffic

- Only ~10% of website visits trigger malicious action, making the attack extraordinarily difficult for security researchers to detect and reproduce

- The operation evolved from ad fraud to distributing Strela Stealer information-stealing malware, suggesting a malware-as-a-service business model

- Server-side operation leaves zero traces on victim machines, rendering antivirus software and endpoint detection tools useless

- Email phishing with malicious attachments remains the primary initial infection vector for website compromise

- Defense requires multi-layered approach including DNS monitoring, file integrity checking, behavioral analysis, and active threat hunting

Related Articles

- Substack Data Breach: What Happened & How to Protect Yourself [2025]

- NGINX Server Hijacking: Global Traffic Redirect Campaign [2025]

- Notepad++ China Hack: What Happened & How to Protect Yourself [2025]

- Zendesk Spam Attack Explained: What's Happening & How to Protect Yourself [2025]

- Sapienza University Ransomware Attack: Europe's Largest Cyberincident [2025]

- Substack Data Breach [2025]: What Happened & How to Protect Yourself

![DNS Malware Detour Dog: How 30K+ Sites Harbor Hidden Threats [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/dns-malware-detour-dog-how-30k-sites-harbor-hidden-threats-2/image-1-1770390529970.jpg)