Introduction: When One of Europe's Largest Universities Goes Dark

It started like any other Tuesday morning at La Sapienza University of Rome. Then, without warning, the digital backbone of one of Europe's largest educational institutions simply vanished offline.

For three days straight, 120,000 students couldn't access grades, course materials, or registration systems. Faculty members stared at blank screens. Administrative staff scrambled to find paper-based alternatives to decades of digital workflows. Email systems ground to a halt. The website displaying the institution's academic reputation became an error page.

This wasn't a power outage or a server upgrade. This was a ransomware attack, and it exposed something uncomfortable about how vulnerable even the largest, most prestigious institutions have become in our connected world.

The incident, attributed to a previously unknown hacking group called "Femwar 02," used Bab Lock malware (also known as Rorschach) to encrypt systems and demand payment within 72 hours. But what makes this attack significant isn't just the disruption it caused. It's what it reveals about the cybersecurity crisis facing universities across Europe and the United States.

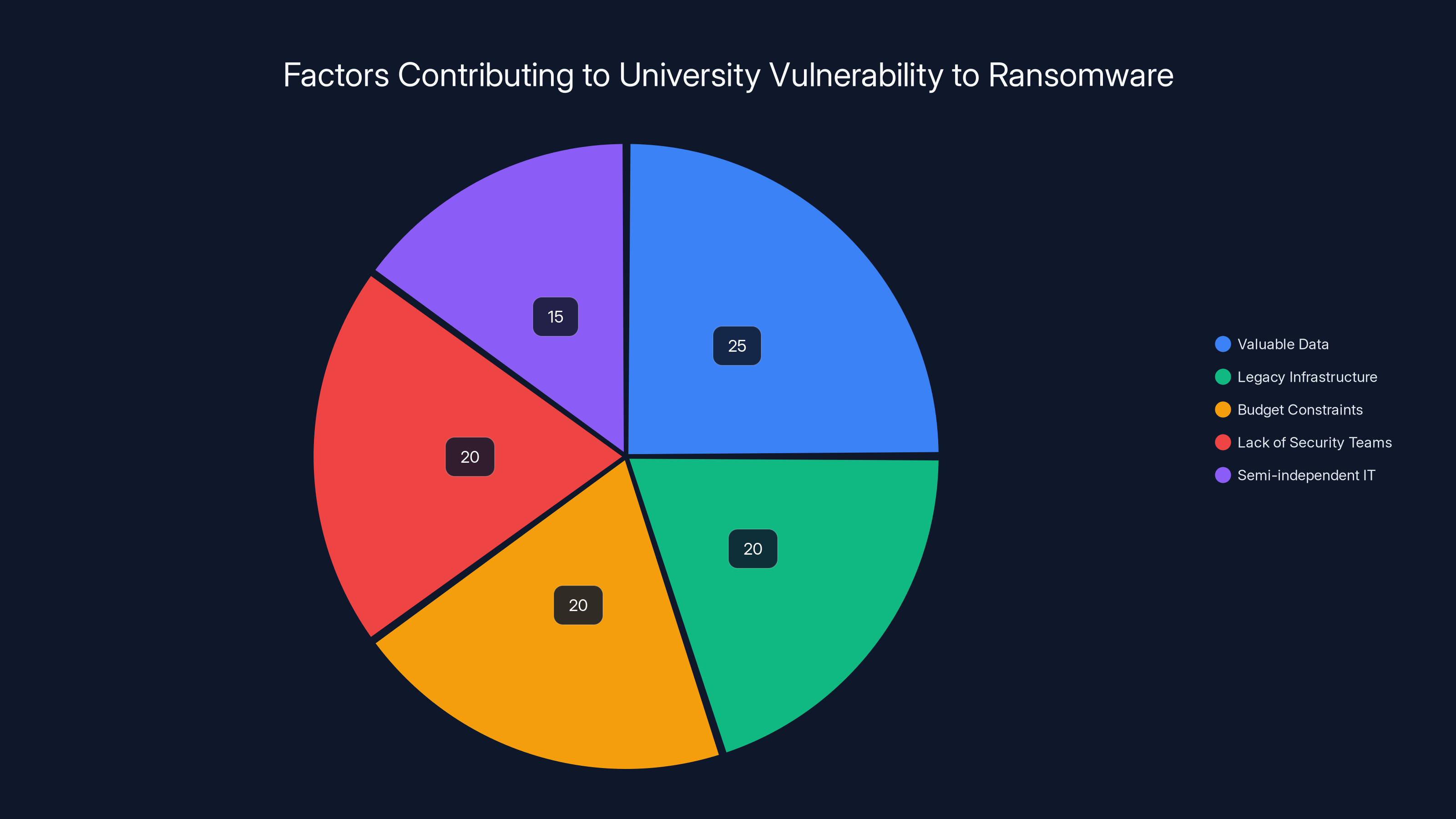

Universities have become attractive targets for cybercriminals for a specific reason: they sit at the intersection of massive value and minimal security. They house sensitive research data, store personal information on hundreds of thousands of students, manage financial systems processing millions in funding, and operate with infrastructure that's often decades old. They're also led by academics, not security professionals. And unlike banks or government agencies, they rarely have the budgets to match their threat exposure.

This article dives deep into what happened at Sapienza, why universities have become prime targets, and what the incident tells us about the future of cybersecurity in higher education.

TL; DR

- La Sapienza University of Rome, one of Europe's largest institutions with 120,000 students, was knocked offline for three days by a ransomware attack

- The attack used Bab Lock malware (Rorschach variant) deployed by previously unknown hacking group Femwar 02

- The attackers sent a ransom demand with a 72-hour countdown timer, though the university's response remains undisclosed

- Universities have become high-value targets because they combine sensitive data with aging infrastructure and limited cybersecurity resources

- Italy's Agenzia per la Cybersicurezza Nazionale (ACN) is investigating the incident as part of broader European cybersecurity concerns

- Institutions must implement zero-trust security, regular backups tested for integrity, and security-first hiring practices to prevent similar attacks

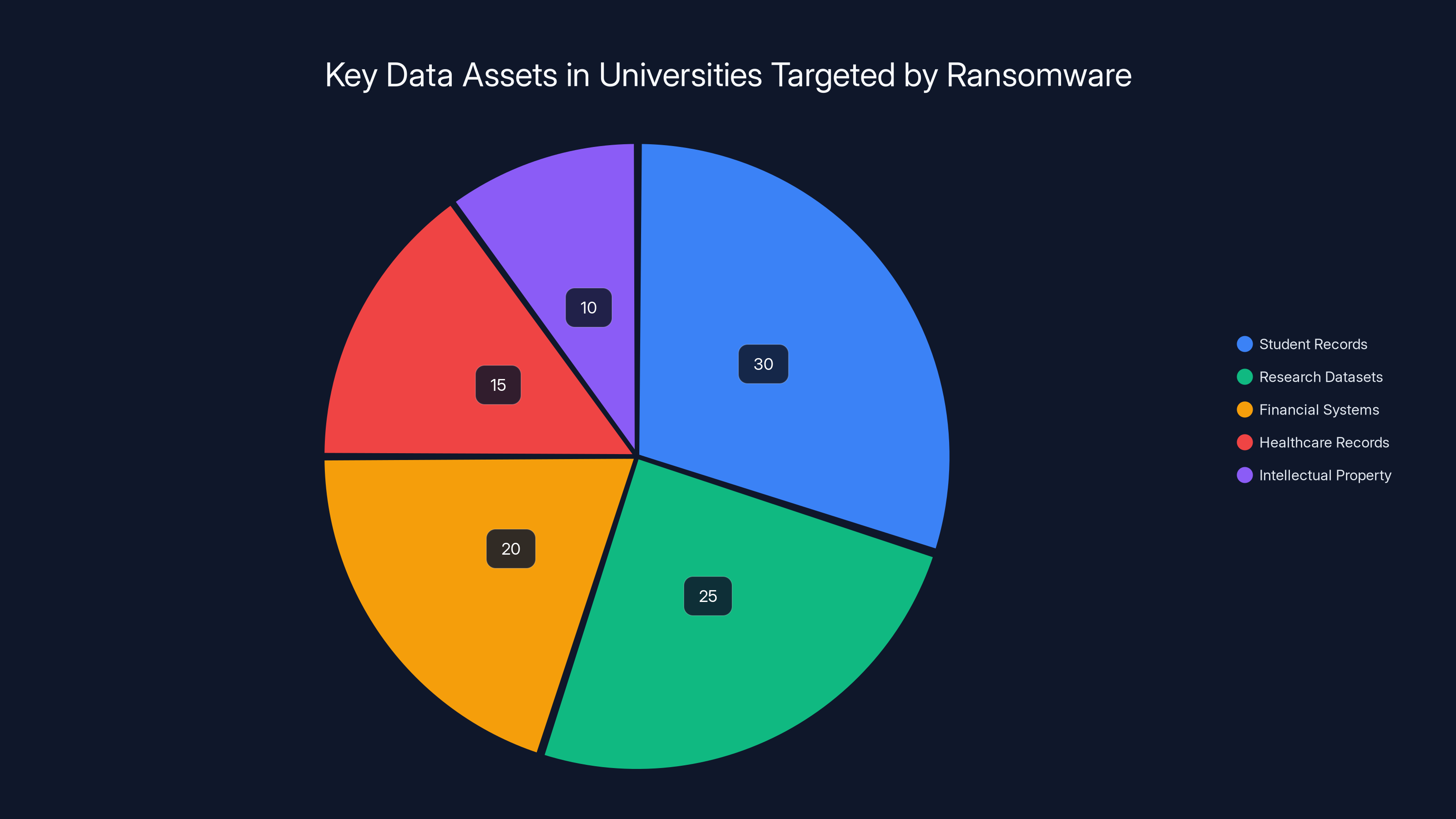

Universities hold diverse data assets, with student records and research datasets comprising the largest shares. Estimated data.

The Anatomy of the Sapienza Attack: What Actually Happened

The Initial Breach and Detection

The timeline of the Sapienza attack follows a pattern increasingly common in ransomware incidents. On a day that hasn't been publicly disclosed, threat actors gained initial access to the university's network. This access likely came through one of several vectors: a phishing email, a compromised credential, an unpatched vulnerability, or an exposed remote access service.

Once inside, the attackers didn't immediately encrypt everything. That would be foolish. Instead, they spent time moving laterally through the network, escalating privileges, and identifying which systems mattered most. They looked for backup infrastructure to disable it. They searched for databases containing valuable information. They located financial systems and administrative controls.

This reconnaissance phase is critical to understanding the sophistication of modern ransomware operations. It's not a smash-and-grab theft anymore. It's an intelligence operation followed by a calculated extortion scheme.

La Sapienza's IT team detected something amiss, likely through unusual network activity or system behavior monitoring. The university then made a critical decision: shut everything down proactively rather than let the encryption spread. This decision prevented total data loss but confirmed what was happening. On Tuesday, the institution posted to Instagram—because their official communications systems were offline—acknowledging the attack.

The Malware: Bab Lock and Its Evolution

The malware used in this attack, Bab Lock (tracked under the alias "Rorschach"), emerged in 2023 and represents a newer generation of ransomware designed to be difficult to detect and analyze. Unlike earlier ransomware variants that relied on distinctive signatures, Bab Lock employs obfuscation techniques that change its appearance with each infection.

Bab Lock's functionality includes several dangerous capabilities. It encrypts files using strong encryption algorithms, making recovery without the decryption key virtually impossible. It identifies and disables backup systems and recovery options, a crucial step that forces victims to choose between paying or losing data. It avoids triggering security alerts by moving slowly through networks and using legitimate Windows administration tools.

What distinguishes Bab Lock from earlier ransomware is its modular design. The attackers can customize the malware for specific targets, disabling certain functions or adding new capabilities. For an institution like Sapienza with mixed network environments and hybrid cloud infrastructure, this flexibility made the malware particularly effective.

The fact that Sapienza's backups weren't affected suggests the university had implemented at least basic backup separation—a practice that many institutions still neglect. However, the malware's ability to propagate across most of the network indicated that lateral movement wasn't restricted, a serious security gap.

The Ransom Demand and Negotiation Tactics

This is where the Sapienza attack took on characteristics that reveal the sophistication of modern ransomware-as-a-service operations. The attackers sent the university a link to a ransom page, not just a simple note. This page contained:

- A countdown timer set for 72 hours

- An amount requested (unreported by the university)

- "Proof" in the form of sample encrypted files

- A message emphasizing urgency and the consequences of non-payment

The 72-hour timer only starts once the link is clicked, a psychological trick. By making the victim click the link, the attackers create proof of contact and begin a negotiation process. They're banking on the fact that once a deadline is established, panic often overrides careful decision-making.

The university never publicly stated whether it paid the ransom or how the negotiations proceeded. This silence is intentional—law enforcement agencies recommend against paying, but some institutions do it anyway as the fastest path to recovery.

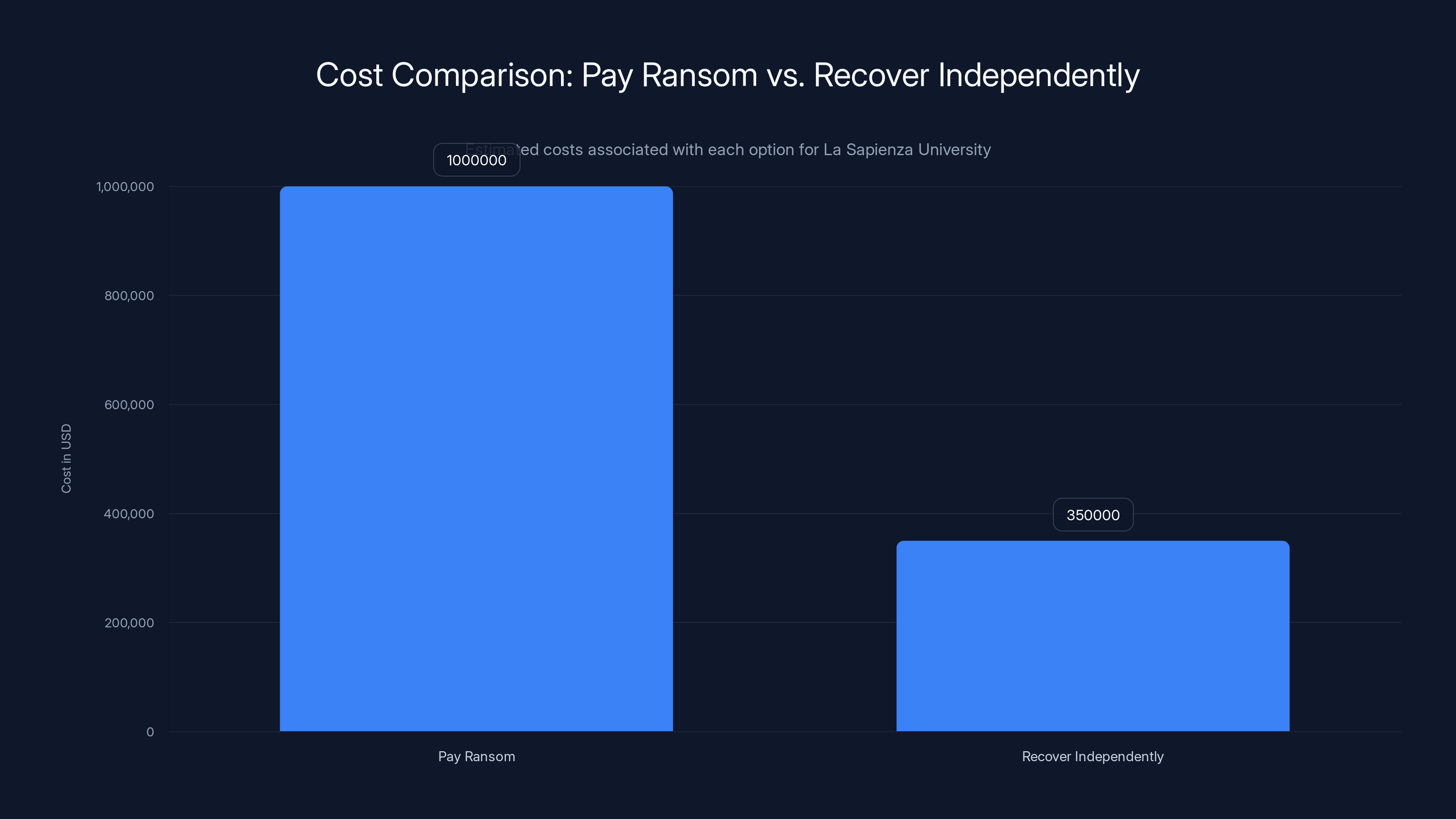

Paying the ransom could cost La Sapienza University approximately

Why Universities Are Becoming Ransomware Goldmines

The Perfect Storm: Data Value Meets Legacy Infrastructure

Universities occupy a unique position in the cybersecurity landscape. They're attacked more frequently than many private companies, yet they operate with security budgets that would make any Fortune 500 CISO weep.

Consider what a university like Sapienza actually contains. There are 120,000 active student records, each including names, addresses, identification numbers, financial information, academic history, and sometimes health data. There are faculty research datasets worth hundreds of millions in potential intellectual property. There are financial systems processing endowment funds, government grants, and student tuition. There are healthcare records if the institution operates a teaching hospital. There are intellectual property secrets that could be valuable to competitors or nation-states.

All of this sits behind infrastructure that's often 10 to 20 years old. Why? University budgets are allocated to education, research, and facilities. IT infrastructure is seen as a cost center, not a revenue generator. A new physics lab gets funding. A network security overhaul does not.

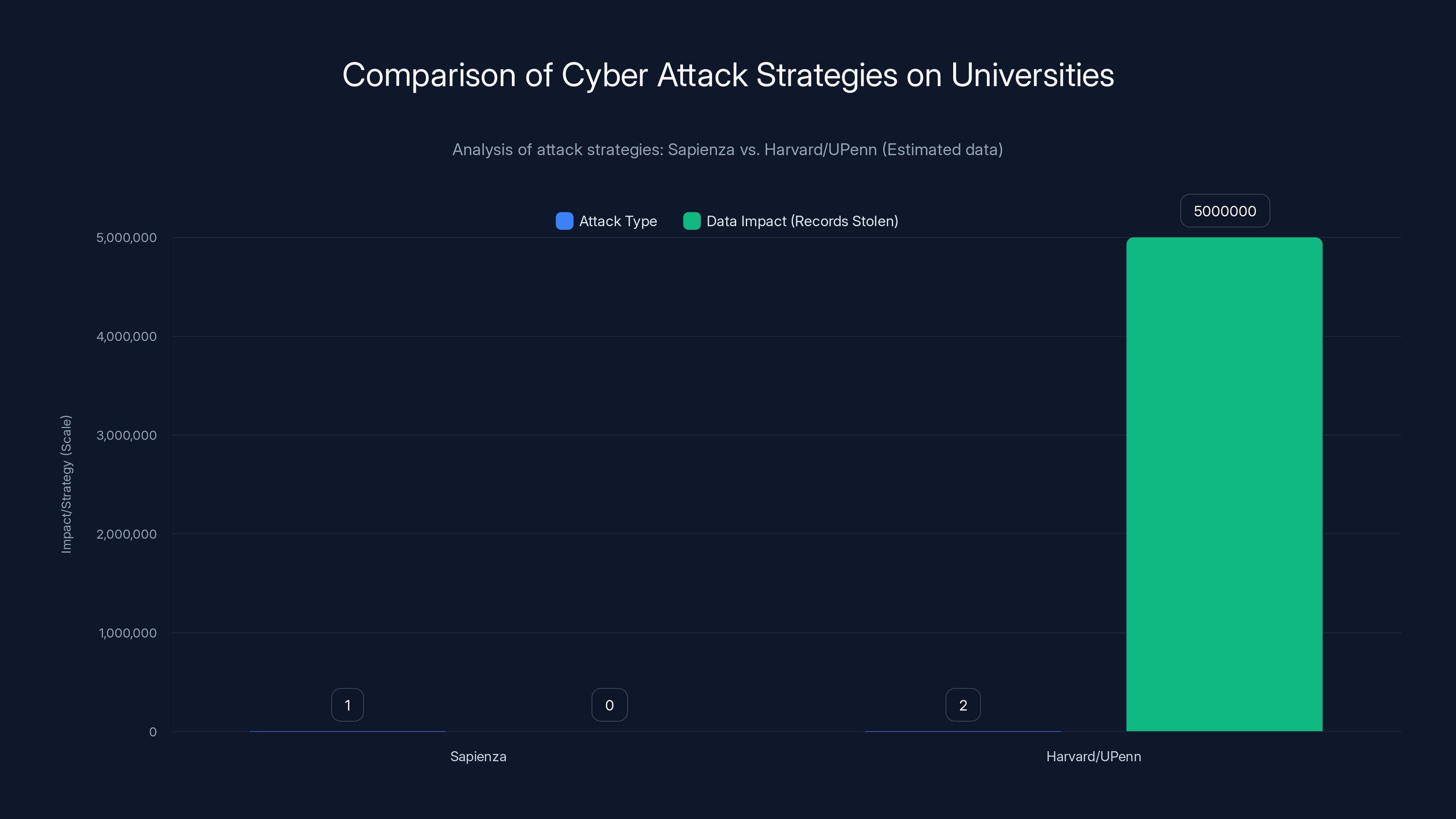

Large state universities in the United States face similar dynamics. SUNY and UC system institutions have experienced major ransomware attacks. Harvard University and University of Pennsylvania were targeted by Shiny Hunters, which stole data without even deploying ransomware. The attackers simply exfiltrated information and threatened to sell it unless paid.

The response from universities has been inconsistent. Some refuse to pay on principle and endure lengthy downtime. Others pay quickly, which reinforces the attackers' business model. There's no perfect choice here—it's a lose-lose proposition.

Attack Economics: Why Ransomware Groups Target Higher Education

Let's talk about the financial incentive structure that makes universities attractive targets.

A typical small company might negotiate a ransomware payment of

Universities operate in a sweet spot. They have significant assets (endowments, research funding, student tuition), but they lack the sophisticated security infrastructure of major corporations. A ransomware group can reasonably demand

Furthermore, universities often negotiate. They're led by administrators, not security professionals. They're vulnerable to emotional appeals about student hardship and research delays. Ransomware groups have learned to exploit this by combining demands with threats to leak sensitive data, knowing that a university will face massive embarrassment if student records become public.

The math works out for attackers. If Femwar 02 successfully extorts 10 universities per year at an average of

The Role of Italy's Cybersecurity Agency and National Response

ACN's Investigation and Limitations

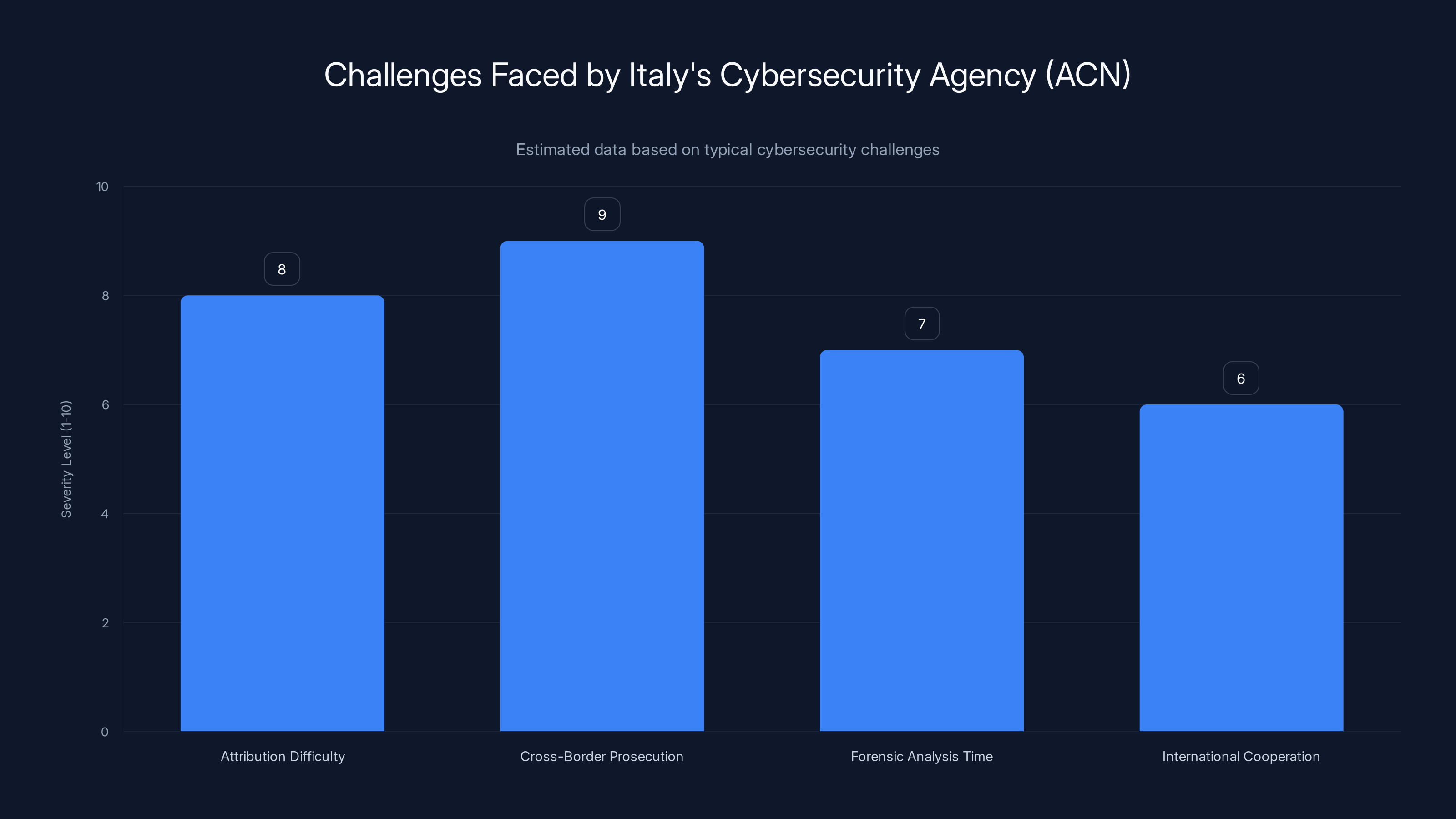

Italy's Agenzia per la Cybersicurezza Nazionale (National Cybersecurity Agency), or ACN, activated immediately after the Sapienza attack became public. This agency, established to coordinate national cybersecurity defense, faced the same challenge that cybersecurity agencies worldwide encounter: attribution is hard, and prosecution across borders is even harder.

ACN's role in the investigation includes several components. First, they're working to understand exactly which systems were compromised and what data was accessed. This requires forensic analysis of the victim's infrastructure, a process that can take weeks or months. Second, they're tracking Femwar 02 to understand the group's origin, motivation, and past activities. This involves analyzing malware samples, tracking cryptocurrency transactions if ransom was paid, and monitoring the criminal underground for mentions of the attack.

Third, and most importantly for future defense, ACN is identifying how the initial breach occurred. Was it a spear-phishing email? A vulnerability in a public-facing application? Compromised VPN credentials? These answers help other Italian institutions strengthen their defenses.

However, ACN faces structural limitations. Even with international cooperation, cybercriminals operating from countries without extradition treaties with Italy face minimal consequences. Femwar 02 may be based in Eastern Europe, Russia, or even operate as an international consortium. Prosecuting them would require cooperation from multiple nations, a process that's slow and often futile.

Italian Higher Education as a Collective Target

The Sapienza attack isn't an isolated incident in Italy. Italian universities have faced increasing cyber threats as the country becomes more visible in the international ransomware landscape. Several factors make Italian institutions particularly vulnerable:

Legacy Systems: Many Italian universities were built in the 1960s-1980s and modernized in ad-hoc ways. Their IT infrastructure reflects these haphazard upgrades, creating security blind spots.

Budget Constraints: Italian public universities operate with tight government budgets, and cybersecurity isn't prioritized in budget discussions.

Coordination Challenges: Unlike countries with more centralized higher education systems, Italian universities operate semi-independently, making it difficult to implement unified security standards.

Linguistic Isolation: Some Italian institutions operate primarily in Italian, making it harder for them to access global cybersecurity resources and threat intelligence that's primarily in English.

ACN's response to the broader threat has included issuing guidance to universities about incident response, backup strategies, and vulnerability management. However, guidance without funding is largely aspirational.

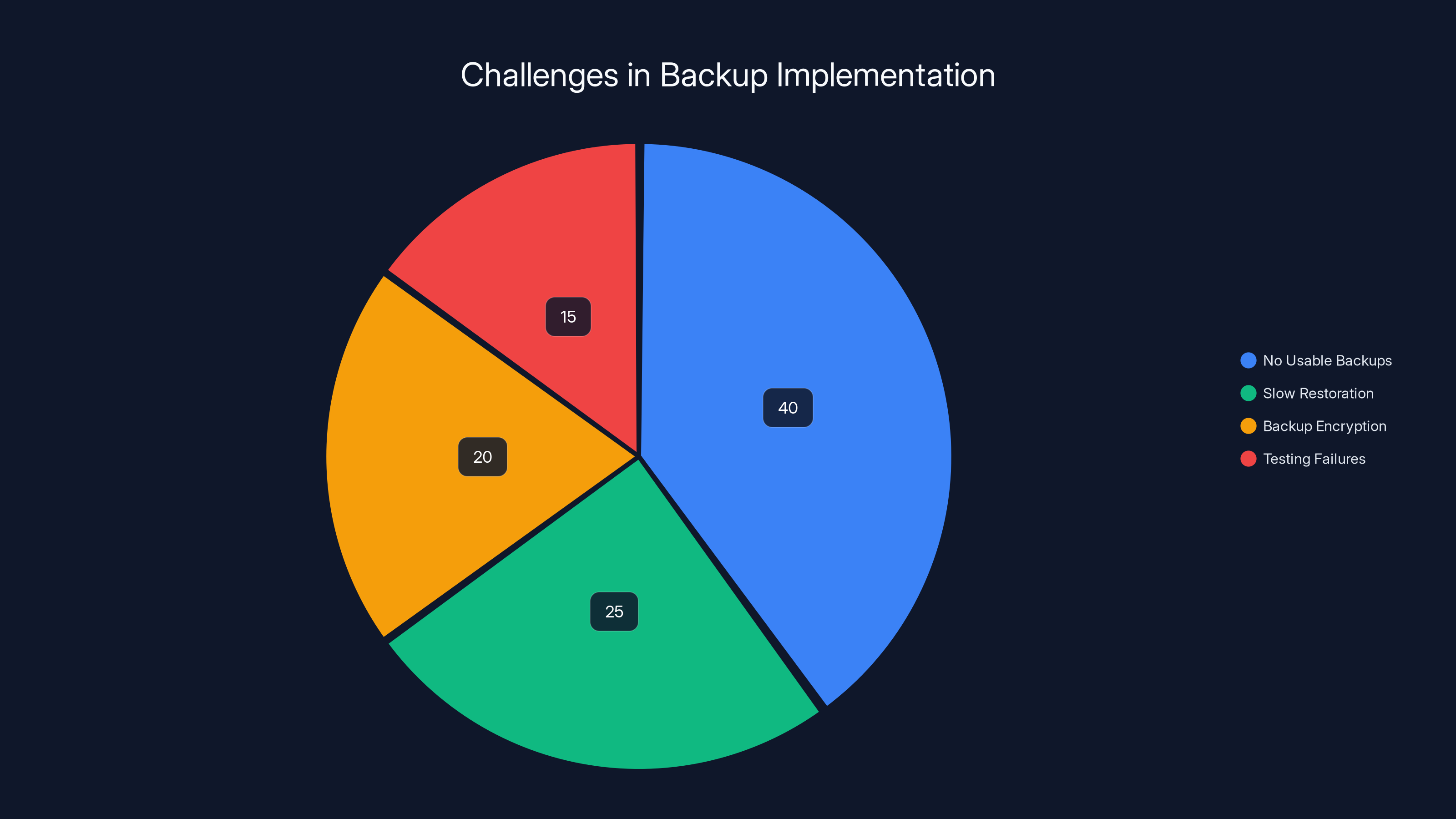

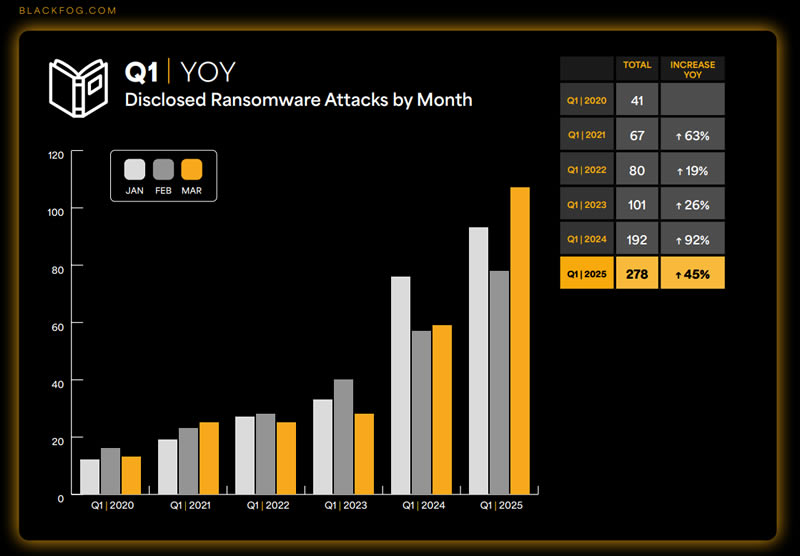

A 2024 survey found that over 40% of organizations hit by ransomware lacked usable backups, highlighting the critical need for effective backup strategies.

Femwar 02: A New Threat Actor Emerges

Limited Intelligence on an Unknown Group

Femwar 02 represents something unusual in the ransomware landscape: a group that emerged with a high-profile attack without prior known activity. This can mean several things.

First, it could be an established group operating under a new name. Ransomware groups frequently rebrand themselves after successful attacks attract law enforcement attention. The Bab Lock malware they used was discovered in 2023, but Femwar 02 may be deploying it differently or with modifications that made attribution difficult.

Second, it could be a splinter group breaking away from a larger ransomware-as-a-service operation. Larger criminal organizations often franchises their malware and attack infrastructure, allowing smaller groups to participate in attacks while paying a percentage of ransom payments.

Third, it could genuinely be a new entrant with technical expertise and capital enough to fund a sophisticated attack. The ransomware landscape has low barriers to entry if you have coding skills and access to initial network penetration tools.

What makes Femwar 02 interesting from an intelligence perspective is their choice of target. La Sapienza is prestigious, large, and Italian. Choosing an Italian institution suggests either a geographic preference or knowledge of the target's security posture. Ransomware groups increasingly specialize by region or industry because local knowledge helps them navigate negotiation dynamics.

Tactics and Technical Sophistication

The technical execution of the Sapienza attack reveals several interesting details about Femwar 02's capabilities.

The use of Bab Lock malware suggests they either developed it themselves or acquired access through a ransomware-as-a-service platform. The malware's obfuscation abilities indicate they're not amateur operators. The lateral movement across the network and ability to reach and disable backup systems shows they employed reconnaissance and exploitation techniques beyond basic script-kiddie capabilities.

However, the fact that Sapienza's backups survived the attack suggests Femwar 02 didn't have complete network visibility. A more sophisticated group might have discovered and disabled the backup infrastructure before deploying encryption. This limitation suggests Femwar 02 is competent but not elite-tier.

Their use of a countdown timer and a web-based ransom interface shows they're following current best practices in extortion psychology. They're not trying to be scary; they're trying to be businesslike and professional, which research shows is more effective at extracting ransom payments.

The Backup Lesson: Why Separation Matters

Why Sapienza's Backup Strategy Worked

Amid the chaos of the Sapienza attack, one crucial security practice saved the institution from complete disaster: backup separation. The university's backups were not affected by the ransomware, meaning recovery was possible without paying ransom or living with permanent data loss.

This wasn't accidental. Someone at some point had made the deliberate choice to store backups separately from production systems. This decision, sometimes called the "3-2-1 backup rule" (three copies of data, on two different media types, with one copy offsite), prevented what could have been a catastrophic loss.

How does backup separation work? The principle is simple but often poorly executed. Your primary data lives on your main systems. Your first backup exists on different physical hardware, preferably in a different data center. Your second backup is completely isolated—either offline or on a system that doesn't share network connectivity with your production environment.

When ransomware deploys, it searches for backup systems to encrypt or delete them. If those backups are truly isolated—not accessible through normal network pathways—the malware can't reach them. Sapienza's IT team had implemented this correctly, which is why recovery was possible.

The Backup Mythology Problem

Here's what's frustrating: backups aren't actually that hard to implement, but institutions consistently fail at them. A 2024 cybersecurity survey found that over 40% of organizations experiencing ransomware attacks either didn't have usable backups or couldn't restore from them quickly.

The problems manifest in several ways:

Backup Encryption: Attackers search for backup systems and encrypt them along with production systems. If your backup system uses the same credentials as your production environment, ransomware can access it.

Backup Testing Failures: Organizations back up their data religiously but never test whether those backups actually restore. When they try to recover, they discover the backups are corrupted, incomplete, or in a format they can't read.

Centralized Backup Systems: Some organizations store all backups on a single network-attached storage system. Ransomware that gains administrative access to that system can delete or encrypt everything.

Retention Gaps: Ransomware sometimes sits dormant in a network for weeks or months before activating encryption. By then, the incremental backups have been overwritten, and the oldest full backup is also encrypted.

Sapienza appears to have avoided most of these pitfalls, which is why the incident, while severe, didn't result in permanent data loss.

Universities are vulnerable to ransomware due to a combination of valuable data, legacy systems, budget constraints, lack of dedicated security teams, and semi-independent IT departments. Estimated data.

The Broader Context: Universities Under Siege

The Harvard and University of Pennsylvania Incidents

The Sapienza attack didn't occur in isolation. It's part of a trend of increasing cybercriminal targeting of major academic institutions.

In late 2024, the hacking group Shiny Hunters breached both Harvard University and the University of Pennsylvania simultaneously. Unlike the Sapienza attack, Shiny Hunters didn't deploy ransomware. Instead, they employed a data exfiltration strategy, stealing millions of records from student information systems, staff databases, and research repositories.

Shiny Hunters then demanded ransom from both institutions, threatening to publicly release the stolen data. This attack vector is particularly effective against universities because the threat isn't just about operational downtime—it's about privacy violations affecting hundreds of thousands of current and former students.

Both Harvard and UPenn initially refused to pay. Shiny Hunters eventually published portions of the stolen data to make good on their threats, affecting administrators, faculty, and students at both institutions. This incident revealed something uncomfortable: even elite institutions with strong endowments and resources weren't adequately prepared for modern cyber threats.

The difference between Sapienza's incident and the Harvard/UPenn incidents highlights an important distinction in ransomware strategy. Encryption-based ransomware (like the Sapienza attack) aims to make systems unusable, forcing payment to regain access. Data exfiltration attacks (like Shiny Hunters) don't need to encrypt anything—they steal data and use privacy concerns as leverage.

The Economics of University Ransomware

Why would ransomware groups focus on universities when so many other targets might seem more lucrative? Let's break down the economics.

A typical hospital ransomware attack might demand $4-8 million because patient care disruption is life-threatening and hospitals have deep pockets. However, hospitals have gotten better at defending themselves, making successful attacks harder.

A typical corporate ransomware attack might demand $1-3 million, but large corporations employ security teams that can detect and stop infections early.

A university attack demands

When you calculate expected value—success probability times average payout—universities become attractive targets despite the lower individual payouts.

Technical Infrastructure Vulnerabilities in Educational Institutions

The Network Segmentation Problem

One lesson from the Sapienza attack is that network segmentation—dividing a network into isolated zones that require special permissions to cross—is critical but often missing in universities.

Universities typically operate networks that are relatively open by design. Researchers need to access computational resources. Students need to access library databases from anywhere on campus. Administrative staff need to access systems from multiple buildings. This openness, while convenient, means that a single compromised account or workstation can often reach systems that should have been restricted.

Contrast this with a bank's network, where tellers have access to exactly the systems they need, and nothing more. A teller's computer can't access the loan origination system or the fraud detection database. But a university faculty member with a compromised computer might be able to reach student records, faculty payroll systems, and research databases from a single infected machine.

Sapienza's lateral movement challenges suggest they lacked tight network segmentation. A more segmented network would have forced Femwar 02 to compromise additional credentials or exploit additional vulnerabilities to propagate from the initial entry point across the entire institution.

The Supply Chain Vulnerability

Many ransomware attacks against large institutions don't target the institution directly. Instead, they target vendors and service providers that have trusted access.

Universities depend on a vast ecosystem of vendors: library services, student information systems, email providers, research collaboration platforms, and more. Each vendor relationship creates a potential entry point. If a vendor's security is weak, attackers can use that vendor as a stepping stone to reach the university.

Some of the most damaging ransomware campaigns in the last three years have exploited vendor vulnerabilities. The MOVEit vulnerability, for instance, affected hundreds of organizations through a single compromised file transfer service.

Sapienza likely depends on multiple external vendors for critical services. If any of those vendors were the entry point for this attack, it highlights a vulnerability that's difficult to solve without vendor cooperation.

The Remote Access Infrastructure Gap

COVID-19 forced universities to enable remote access rapidly. Many institutions deployed VPN services, cloud-based collaboration tools, and remote desktop infrastructure without the security hardening that should accompany such expansions.

Now, even as campuses have returned to in-person operations, much of that remote infrastructure remains. Attackers know this. They probe university networks specifically looking for exposed VPNs, unpatched remote desktop services, and other remote access mechanisms with weak authentication.

If the Sapienza attack originated through remote access—a common initial access vector for ransomware—it suggests their remote infrastructure lacked multi-factor authentication or other modern security controls.

The Sapienza attack used encryption-based ransomware, while Harvard/UPenn faced data exfiltration, resulting in millions of records stolen. Estimated data highlights the strategic differences.

Incident Response: The Three-Day Recovery Challenge

What Happened During the Shutdown

When La Sapienza's IT leadership made the decision to shut down systems to prevent further encryption, they initiated a complex incident response process that unfolded over three days.

Day One would have involved shutting down critical systems, isolating compromised servers, and beginning forensic analysis. The team would have assessed which systems were encrypted, which were untouched, and what data might have been exfiltrated.

Day Two would have involved formulating a recovery plan. IT leaders would have determined which backups to restore, in what order. They'd want to restore critical systems first (email, authentication services, core databases) before less critical systems (websites, publishing platforms, development environments).

Day Three would have involved actual restoration and validation. Each restored system would need testing to ensure it worked properly and wasn't reinfected with malware.

The fact that systems came back online after exactly three days suggests the IT team had a practiced incident response plan, working backups, and sufficient technical resources. Smaller universities with weaker IT departments might have taken weeks to recover.

The Communication Challenge

During the shutdown, Sapienza faced a communication challenge: their normal channels (email, website, social media management tools) were offline. They improvised by posting directly to Instagram, using stories to update the university community on status.

This is smart crisis communication, but it also reveals how dependent modern institutions are on digital systems. Instagram works when your official communications infrastructure doesn't. It's an indictment of how concentrated institutional digital presence has become.

The university's measured, professional tone in its communications—acknowledging the problem, explaining the investigation, providing updates—likely helped prevent panic among students and faculty. Many ransomware incidents are mishandled because leadership tries to hide problems rather than communicate transparently.

Why Recovery Took Exactly Three Days

The timeline is worth analyzing. Three days is relatively fast for recovering from a ransomware attack affecting 120,000 people. This suggests several things about Sapienza's incident response:

-

Pre-incident planning existed: The IT team knew what to do because they'd practiced or planned for this scenario.

-

Automated recovery tooling was in place: They likely had scripts and processes to rebuild systems quickly rather than doing everything manually.

-

Backup integrity was verified: They could restore with confidence because they'd tested backups previously.

-

Executive support was strong: Recovery operations require significant resources. If executives had delayed decision-making, recovery would have taken longer.

Comparison: institutions that take weeks or months to recover usually lack one or more of these elements.

The Cost Calculus: To Pay or Not to Pay

The Economics of Ransom Payment

La Sapienza never publicly stated whether it paid the ransom, but understanding the economics of that decision is crucial.

Assume the attackers demanded $1 million. The university faces this calculation:

Option A: Pay the ransom

- Cost: $1 million

- Timeline: 24-48 hours after payment to receive decryption key (assuming attackers deliver)

- Risk: No guarantee the key works; no guarantee attackers delete stolen data

- Moral hazard: Encourages future attacks

Option B: Refuse and recover from backups

- Cost: IT staff overtime for 1-2 weeks, equipment replacement, external forensics consulting (500,000 total)

- Timeline: 1-2 weeks

- Risk: Uncertainty about whether recovery is complete; data might be lost if backups are incomplete

- Principle: Doesn't fund criminal operations

Sapienza appeared to choose Option B, given that systems came back online within three days without any public indication of ransom payment. If they had paid, attackers would likely have confirmed this (since they need to maintain their reputation in criminal circles).

The reputational cost of paying should also be considered. A university that's known to pay ransoms becomes a target for future attacks. Once word spreads in the criminal underground that an institution will negotiate, the targeting increases.

Why Ransom Payments Persist

Despite law enforcement's strong recommendation against paying, approximately 40% of organizations hit by ransomware still pay. Why?

The primary reason is time pressure. A hospital can't have its systems down for two weeks. A financial institution can't tolerate that disruption. A university might be able to, but the leadership faces daily pressure from students, faculty, and staff.

The second reason is incomplete backups. An organization believes its backups are complete, attempts recovery, and discovers critical systems are missing or corrupted. Facing the choice between paying for immediate recovery or dealing with months of data loss, they choose to pay.

The third reason is ego and embarrassment. Some organizations pay to avoid the public relations impact of admitting they were compromised. They'd rather lose money than lose credibility.

The fourth reason is insurance. Some cyber insurance policies actually cover ransom payments, making the net cost to the organization zero. This creates a perverse incentive where paying the ransom is financially optimal from the organization's perspective, even if it's bad for society overall.

The ACN faces significant challenges, particularly in attribution and cross-border prosecution, with severity levels estimated between 6 and 9. Estimated data.

The Malware Landscape: Bab Lock and Beyond

Understanding Bab Lock's Technical Capabilities

Bab Lock emerged in 2023 as a relatively sophisticated ransomware variant. Understanding its technical capabilities provides insight into what Sapienza faced.

Bab Lock uses AES-256 encryption for file encryption, which is mathematically impossible to break without the decryption key. It also employs RSA-2048 for securing the encryption keys themselves, meaning even if you had tremendous computing power, you couldn't decrypt the AES keys without the RSA private key that only the attackers possess.

The malware has several operational modes. In stealth mode, it encrypts files slowly, trying to avoid triggering security alerts. In aggressive mode (which might have been used against Sapienza), it encrypts rapidly and aims to maximize impact before detection.

Bab Lock also includes persistence mechanisms—code designed to survive system reboots and reinfection attempts. This means even if an institution kills a Bab Lock process, the malware might automatically restart.

Moreover, Bab Lock has anti-analysis capabilities. It detects when it's running in a virtual machine or sandbox environment (used by security researchers for analysis) and changes its behavior to avoid revealing its true capabilities. This makes understanding and studying the malware significantly harder.

The Rorschach Variant and Mutation

Bab Lock is also known as Rorschach, named after the psychological test where subjects interpret ambiguous inkblots. The name refers to the malware's ability to appear different to different analysis tools, almost like it's "interpreted" differently depending on how you look at it.

This polymorphic nature is achieved through code obfuscation and code packing techniques. Each sample of Rorschach might look different even though it performs the same function. This makes signature-based detection (where security tools look for specific patterns) largely ineffective.

Rorschach samples have been found in the wild with different capabilities. Some variants focus purely on encryption and extortion. Others include data exfiltration components, stealing files before encrypting them. This modularity allows the attackers to customize the malware for specific targets.

The Ransomware-as-a-Service Model

Bab Lock's availability to Femwar 02 raises questions about the ransomware-as-a-service (RaaS) ecosystem. Most modern ransomware isn't developed by lone actors. Instead, it's developed by specialized malware developers who then lease it to operators.

The RaaS model works like this: a developer creates malware and hosts it along with infrastructure for managing payments, distributing decryption keys, and negotiating with victims. They then recruit operators (criminals without advanced coding skills) who use the malware to attack targets. The developer takes 20-40% of ransom payments; the operators keep the rest.

This business model has created a commoditized ransomware market. The barrier to entry for new operators is low—you don't need to understand the malware's code, just how to deploy it. This has proliferated attacks.

Femwar 02's use of Bab Lock suggests they might be operators within a RaaS ecosystem rather than independent developers. This is typical for most ransomware attacks.

European Cybersecurity Policy Response

The NIS2 Directive and Higher Education

Europe is tightening cybersecurity requirements through regulatory frameworks, most notably the NIS2 Directive (Network and Information Security Directive 2), which updates the original NIS Directive from 2016.

NIS2 expands the definition of "critical infrastructure" to include education. This means large universities and research institutions are now subject to mandatory cybersecurity requirements. They must implement:

- Risk management programs with regular assessments

- Security-by-design principles in system architecture

- Incident reporting requirements to authorities within 24 hours of detection

- Board-level cybersecurity oversight requiring university leadership to take responsibility

- Regular security audits by independent assessors

- Zero-trust architecture principles in network design

The Sapienza incident likely triggered NIS2 compliance reviews across Italian higher education. Universities now have obligations they might not have had before.

NIS2 also introduces requirements for supply chain security, meaning universities must vet their vendors' cybersecurity practices and contractually require minimum security standards.

GDPR and Data Breach Notification

Beyond NIS2, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) creates obligations for universities handling European data (essentially all of them). GDPR requires:

- Notification of data breaches to authorities within 72 hours of discovery

- Individual notification to affected persons if a breach presents high risk

- Documentation of security measures and their effectiveness

- Data protection impact assessments before deploying new technologies

If Femwar 02 exfiltrated data during the Sapienza attack, the university faces GDPR notification obligations. This adds legal and financial consequences beyond just the operational disruption.

European Cybersecurity Agency Coordination

The European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA) has been increasing coordination among member states on ransomware response. They've issued guidance on:

- Ransomware negotiation protocols (coordinate with law enforcement before paying)

- Incident response playbooks customized for different sectors

- Threat intelligence sharing mechanisms to coordinate response to campaigns like Femwar 02

Enforcement of these frameworks remains inconsistent. Some countries (like Germany and France) have strong cybersecurity agencies with significant resources. Others, including Italy historically, have had less well-resourced cybersecurity operations. However, NIS2 will drive convergence toward higher minimum standards.

Lessons for Universities: Building a Resilient Posture

Zero-Trust Architecture for Educational Networks

The traditional network security model assumes a clear boundary: inside (trusted) versus outside (untrusted). Users on campus are trusted; anyone outside is suspect. But modern attacks happen because insider threats are real, and compromised credentials work from anywhere.

Zero-trust architecture reverses this assumption. Every user, every device, every service is assumed to be potentially compromised. Access is granted only after verification.

For universities, implementing zero-trust means:

-

Eliminate implicit trust in the campus network. Being on campus WiFi doesn't grant unrestricted access.

-

Implement strong identity verification. Multi-factor authentication for all systems, especially administrative access.

-

Segment networks microscopically. A student's computer shouldn't be able to reach the faculty payroll database just because they're connected to campus WiFi.

-

Monitor and authenticate lateral movement. Even once inside the network, each system must authenticate for access to sensitive resources.

-

Default to deny. Access is only granted when explicitly approved, not granted by default.

Implementing zero-trust in a university environment is complex because universities prioritize openness and ease of access. But the Sapienza incident demonstrates the cost of that openness.

Incident Response Planning and Tabletop Exercises

Sapienza's relatively quick recovery suggests they had incident response capabilities. Other universities should emulate this through:

Tabletop exercises: Quarterly simulations where leadership walks through a ransomware attack scenario. What would we do? How would we communicate? What are our constraints?

Incident response playbooks: Written plans for different scenarios. A ransomware attack has different requirements than a data breach or a DDoS attack.

Defined roles and escalation: Who decides whether to pay ransom? Who communicates with law enforcement? Who manages student communications? These decisions need to be made before the crisis.

Regular drills: Test backup restore procedures. Test incident communication plans. Test law enforcement coordination.

Security-First Hiring and Training

Much of the Sapienza attack's success likely hinged on compromised credentials. Whether through phishing, credential stuffing, or exploited vulnerabilities, the attackers gained initial access through a user account.

Defending against this requires:

Mandatory security training: All staff should understand phishing, social engineering, and basic security hygiene. Annual training is insufficient; quarterly training is better.

Credential hygiene: Passwords should be strong and unique. Shared accounts should be eliminated. Service accounts should use machine-generated, regularly rotated secrets.

Security culture: The institution should normalize reporting suspicious activity. If a staff member reports a phishing email or unusual account access, they should be thanked, not punished.

Privileged access management: Accounts with elevated permissions should have additional protections, including hardware security keys, more frequent rotation, and additional monitoring.

The Future: What's Next for University Cybersecurity?

Emerging Threats: AI-Assisted Attacks

The next evolution in ransomware will likely involve artificial intelligence. Attackers are already experimenting with AI to:

- Personalize phishing emails based on social media research and employee data

- Identify high-value targets within networks more efficiently

- Adapt malware behavior in real-time based on defensive responses

- Automate negotiation through chatbots that engage victims

Universities' AI research activities make them particularly interesting targets for threat actors who want to understand AI capabilities and limitations.

The Critical Infrastructure Designation Impact

With NIS2 classifying universities as critical infrastructure, the regulatory landscape will tighten. Expect:

- Mandatory security certifications for IT staff

- Third-party security audits becoming routine

- Cyber insurance requirements with minimum coverage levels

- Public breach disclosure becoming the norm

These changes, while creating compliance burden, should also drive improvements in actual security posture.

The Consolidation of Ransomware Operations

Unlike the early days of ransomware when hundreds of groups operated, we're seeing consolidation. Larger, more sophisticated groups are acquiring or absorbing smaller ones. This means fewer but more capable threat actors.

Femwar 02's emergence might represent this consolidation—a rebranding or split from an existing operation. Universities should prepare for increasingly sophisticated, patient attackers rather than opportunistic ones.

Institutional Resilience: Beyond Technology

The Human Element

Technology alone won't prevent ransomware attacks. The human element remains crucial.

Much of security depends on people making good decisions: IT staff maintaining systems properly, administrators responding quickly to incidents, leaders making difficult choices about ransom negotiation, and users reporting suspicious activity.

Sapienza's quick recovery depended on people, not just backups. Someone had to make the decision to shut down systems. Someone had to validate that backups were usable. Someone had to orchestrate a complex restoration process across hundreds of systems.

Building this human capacity means investing in IT staff salaries and training, ensuring decision-makers understand cybersecurity, and creating a culture where security isn't a box to check but a foundational principle.

The Economic Reality

Universities operate under budget constraints that often pit cybersecurity against other priorities. A new research facility might generate prestige and funding. Cybersecurity investments generate cost avoidance, which doesn't show on the balance sheet.

This economic misalignment is the root cause of vulnerability. Until universities genuinely prioritize security investment, they'll remain attractive targets.

The Sapienza incident should shift this calculus. The cost of recovery, lost research time, reputational damage, and regulatory fines likely exceeds what a robust security program would have cost.

FAQ

What is La Sapienza University and why was it targeted?

La Sapienza University of Rome is one of Europe's largest institutions with approximately 120,000 students. It was targeted because universities combine valuable data assets with legacy infrastructure and limited security resources, making them attractive targets for ransomware operators seeking ransom payments and data exfiltration opportunities.

How does Bab Lock malware work and what makes it dangerous?

Bab Lock (also called Rorschach) uses AES-256 encryption to encrypt files and RSA-2048 to secure the encryption keys, making decryption impossible without the attackers' private key. Its polymorphic nature allows it to appear different to security analysis tools, making detection difficult. The malware includes anti-analysis capabilities to avoid detection in virtual environments and can disable backup systems before deployment.

What is the Femwar 02 threat actor group?

Femwar 02 is a previously unknown ransomware operator who claimed responsibility for the Sapienza attack using Bab Lock malware. Limited intelligence suggests they may be operators within a ransomware-as-a-service (RaaS) ecosystem rather than independent developers, indicating they likely license malware from specialized developers rather than creating it themselves.

Why are universities particularly vulnerable to ransomware attacks?

Universities combine multiple risk factors: they hold valuable data (student records, research, financial information), operate legacy infrastructure built over decades, work under tight budgets that prioritize education over security, lack dedicated security teams, and employ semi-independent IT departments. This combination makes them attractive targets with high success rates and reasonable ransom demands.

How can universities prevent ransomware attacks similar to Sapienza's?

Key prevention strategies include implementing zero-trust architecture that verifies all users and devices, conducting regular incident response tabletop exercises, maintaining tested and isolated backups, deploying multi-factor authentication for all systems, implementing network segmentation to restrict lateral movement, conducting mandatory security awareness training, and establishing board-level cybersecurity oversight.

What does the NIS2 Directive require of universities?

The NIS2 Directive classifies large universities as critical infrastructure, requiring them to implement risk management programs, security-by-design principles, incident reporting to authorities within 24 hours, board-level cybersecurity oversight, regular security audits, zero-trust architecture principles, and supply chain security vetting. These requirements will drive significant changes in how universities approach cybersecurity governance.

Should institutions pay ransomware demands?

Law enforcement agencies recommend against payment, as it funds criminal operations and increases targeting of the organization. However, payment may be necessary if backups are incomplete or non-functional. Decisions should be made in consultation with law enforcement, legal counsel, and cyber insurance providers, not under the pressure of artificial countdown timers that are almost always negotiable.

How did Sapienza recover systems so quickly?

The three-day recovery timeline suggests Sapienza had pre-incident planning including documented recovery procedures, tested backup systems stored separately from production systems, automated recovery tooling, sufficient IT staff resources, and strong executive support. Many organizations take weeks or months because they lack one or more of these elements.

What are the financial incentives for ransomware attacks on universities?

Universities represent optimal ransom targets: they have assets in the

What should universities do about vendor and supply chain security?

Universities depend on numerous vendors with trusted network access. NIS2 now requires contractual security requirements for vendors, regular audits of vendor security practices, monitoring of vendor vulnerabilities, and incident response plans that account for vendor compromise. Many recent attacks exploit vendor vulnerabilities, making supply chain security as important as internal security.

Conclusion: A Wake-Up Call for Higher Education

The Sapienza University ransomware attack is important not because it was unprecedented—universities have been hit before—but because it happened to one of Europe's largest and most prestigious institutions and because it captures perfectly the collision between institutional complacency and threat actor sophistication.

For seventy-two hours, 120,000 students lost access to their academic lives. Research projects stalled. Faculty couldn't access their work. Administrative processes ground to a halt. The disruption was complete and compounded by the inability to communicate through normal institutional channels. The university was forced to turn to Instagram to tell its community what was happening.

Yet Sapienza was lucky. Its backups weren't encrypted. Its IT team had practiced incident response or at least planned for it. Three days is a remarkable recovery timeline. Many institutions would have taken weeks. Some might still be recovering.

What makes the Sapienza incident particularly significant is what it reveals about systemic vulnerabilities in European higher education. These aren't unique to Sapienza. They're replicated across hundreds of universities: legacy infrastructure maintained on shoestring budgets, IT staff stretched thin, cybersecurity relegated to compliance checkboxes rather than strategic priorities, networks designed for openness rather than security, and leadership that doesn't understand the threat landscape.

The Italian Agenzia per la Cybersicurezza Nazionale is investigating. The institution is recovering. But the broader question remains: will this incident catalyze real change, or will it be treated as an isolated incident while the underlying vulnerabilities persist?

The regulatory framework is shifting. NIS2 will force universities to take security seriously. But regulation alone won't prevent ransomware. What's needed is a fundamental reorientation where security is not a cost center but a foundational investment in institutional resilience.

For universities worldwide, the Sapienza incident should serve as a catalyst. The threat is real. The vulnerability is systemic. The time to act is now, before the next major institution is knocked offline.

Key Takeaways

- La Sapienza University's three-day ransomware attack demonstrates how vulnerable large institutions can be to sophisticated cyber threats despite their prestige and resources

- Universities have become optimal ransomware targets because they combine valuable data assets with aging infrastructure and limited security resources while facing pressure to recover quickly

- BabLock malware (Rorschach variant) used in the attack includes advanced polymorphic capabilities, anti-analysis features, and lateral movement tools that make detection and analysis difficult

- Proper backup separation, where backups are isolated from production systems, prevented total data loss at Sapienza and enabled recovery within three days

- The NIS2 Directive now classifies universities as critical infrastructure, requiring robust security controls, incident reporting, and board-level oversight that will fundamentally change how institutions approach cybersecurity

- Zero-trust architecture, network segmentation, and multi-factor authentication are essential defensive strategies to prevent the lateral movement and credential exploitation that enabled the Sapienza attack

Related Articles

- Conduent Data Breach 2025: What Millions of Americans Need to Know [2026]

- Substack Data Breach: What Happened & How to Protect Yourself [2025]

- Substack Data Breach [2025]: What Happened & How to Protect Yourself

- Harvard and UPenn Data Breaches: What You Need to Know [2025]

- Password Security Guide: Why Strong Credentials Matter in 2025

- Bulletproof Hosting & Ransomware: How Cybercriminals Exploit Virtual Machines [2025]

![Sapienza University Ransomware Attack: Europe's Largest Cyberincident [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/sapienza-university-ransomware-attack-europe-s-largest-cyber/image-1-1770320511258.jpg)