Here's what happened: a developer installs a library to interact with a decentralized exchange. Looks legitimate. Comes from the official repository. Works fine for weeks.

Then one morning, their wallet is empty.

This isn't hypothetical. It's what unfolded when malicious packages targeting the dYdX cryptocurrency exchange hit npm and PyPI in early 2025. The attack wasn't sophisticated in the traditional sense, but it was devastatingly effective because it exploited the deepest trust relationships in software development: the package repositories we rely on daily.

What's worse? This is the third time dYdX has been targeted in as many years.

The incident reveals something uncomfortable about how we build software today. We install hundreds of packages without reading them. We trust that major repositories do basic verification. We assume official accounts can't be compromised. And when all those assumptions break, the damage spreads instantly across thousands of projects.

Let's walk through exactly what happened, why it matters, and how developers and organizations can protect themselves from similar attacks.

TL; DR

- The Attack: Malicious npm and PyPI packages for dYdX stole wallet credentials and installed remote access trojans (RATs) on developer machines and production systems

- The Reach: Both npm (@dydxprotocol/v4-client-js) and PyPI (dydx-v4-client) packages were compromised, affecting all applications using these libraries

- The Pattern: This is the third attack on dYdX in three years, indicating a persistent threat pattern and repeated security lapses

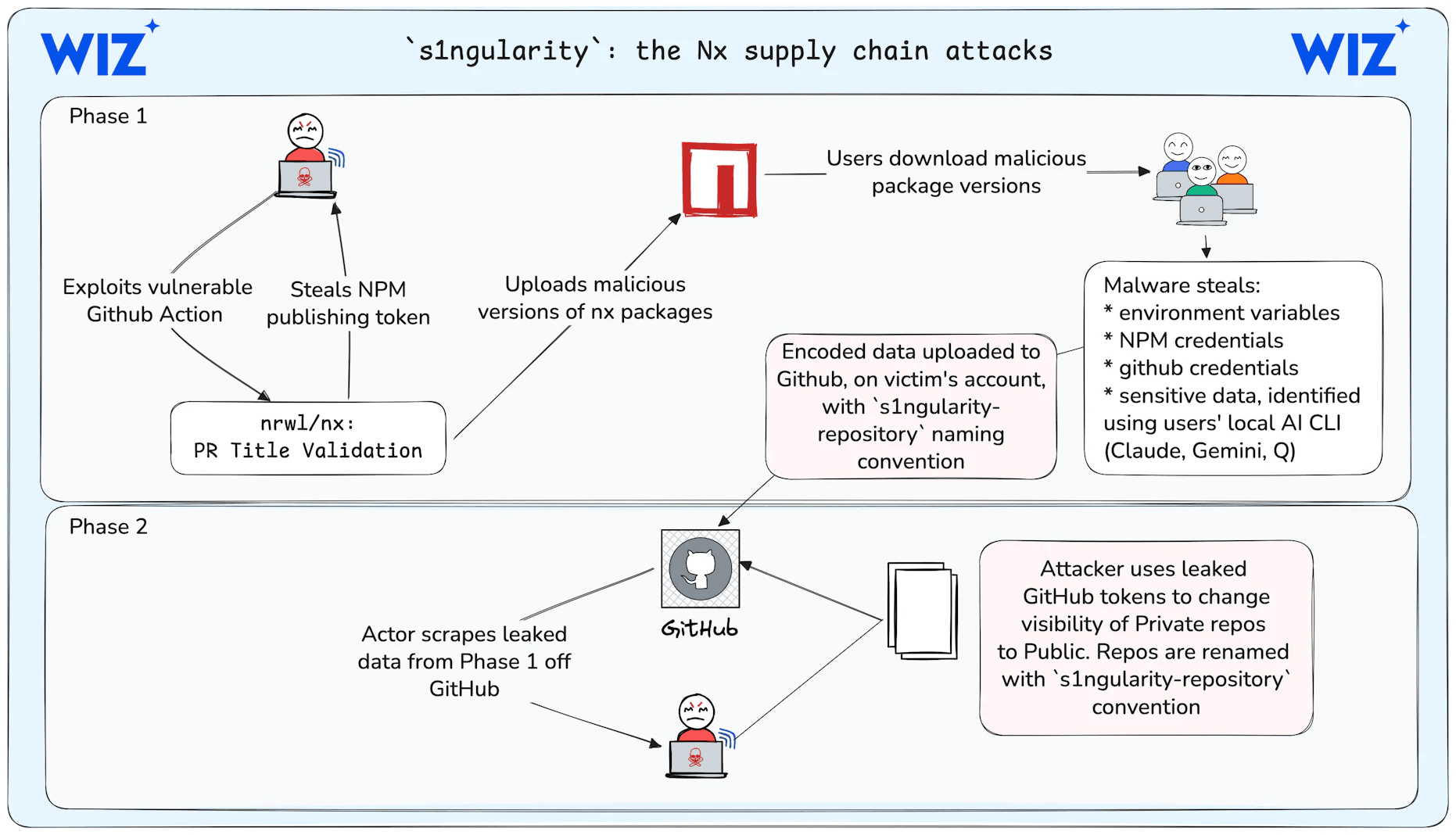

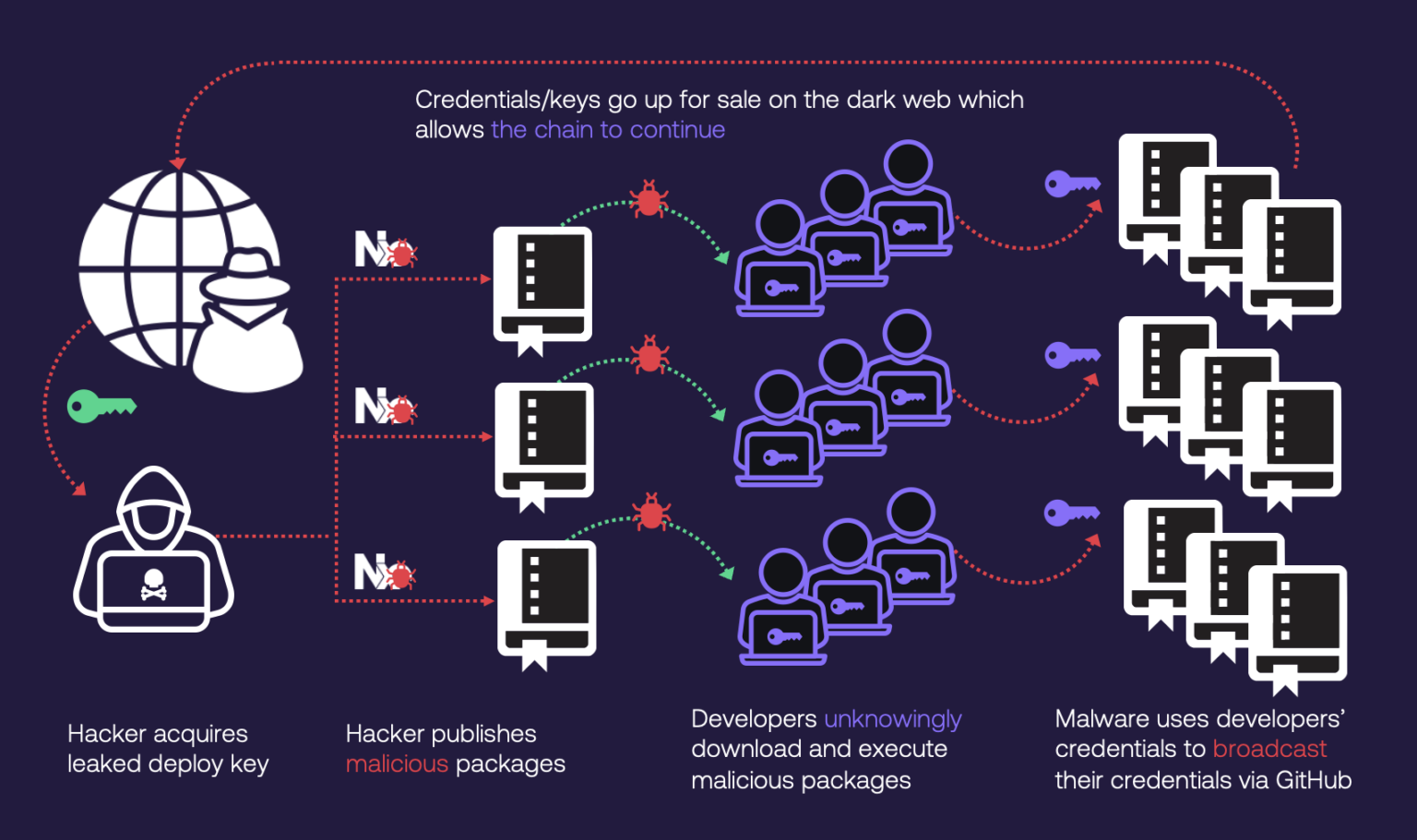

- The Mechanism: Attackers compromised official dYdX accounts, then published malicious versions using typosquatted command and control domains

- The Solution: Comprehensive supply chain security practices, dependency auditing, and credential isolation are now essential, not optional

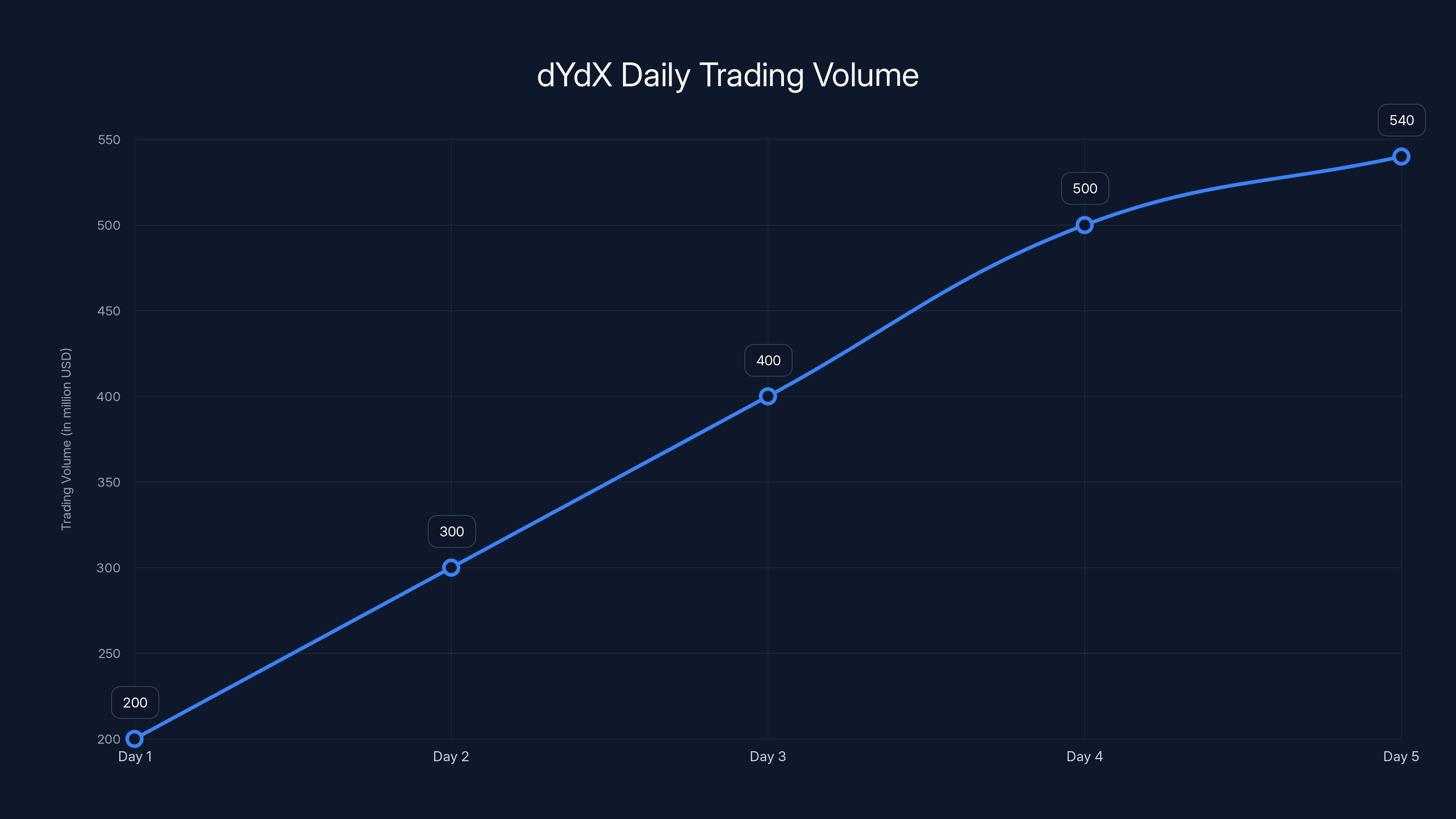

The dYdX exchange handles between

The dYdX Ecosystem: Billions at Stake

dYdX operates as a decentralized derivatives exchange, meaning it's not run by a central company but rather by a distributed network of validators and smart contracts on the blockchain. The exchange handles perpetual trading, which allows users to bet on whether cryptocurrency prices will rise or fall using leverage and derivatives.

The scale is massive. Over its lifetime, dYdX has processed more than

To facilitate this trading, dYdX publishes client libraries in multiple programming languages. Developers use these libraries to build trading bots, automated strategies, or backend services that connect to the exchange. These libraries need to handle something called mnemonics or private keys, which are essentially the cryptographic secrets that prove you own cryptocurrency and allow you to move it.

This is where the attack vector exists. Any library that touches private keys or seed phrases becomes a high-value target. Compromise it once, and you compromise every application built on top of it.

How the Malicious Packages Worked

The technical implementation of this attack was remarkably straightforward, which is precisely why it was so effective.

The npm Package Attack

On npm, the malicious version of @dydxprotocol/v4-client-js included legitimate functionality alongside hidden malicious code. When the package processed a seed phrase, a concealed function would immediately exfiltrate that seed phrase to an attacker-controlled server.

But the attackers went further. They also extracted a device fingerprint, which is essentially a unique identifier for the computer running the code. This fingerprint served a critical purpose: it allowed threat actors to correlate stolen credentials with specific devices and track victims across multiple potential compromises.

The receiving endpoint for these stolen seeds was dydx.priceoracle.site, a domain designed to mimic the legitimate dYdX service at dydx.xyz. This is called typosquatting, where attackers register domain names that closely resemble legitimate ones, gambling that some portion of traffic will mistakenly reach the malicious domain.

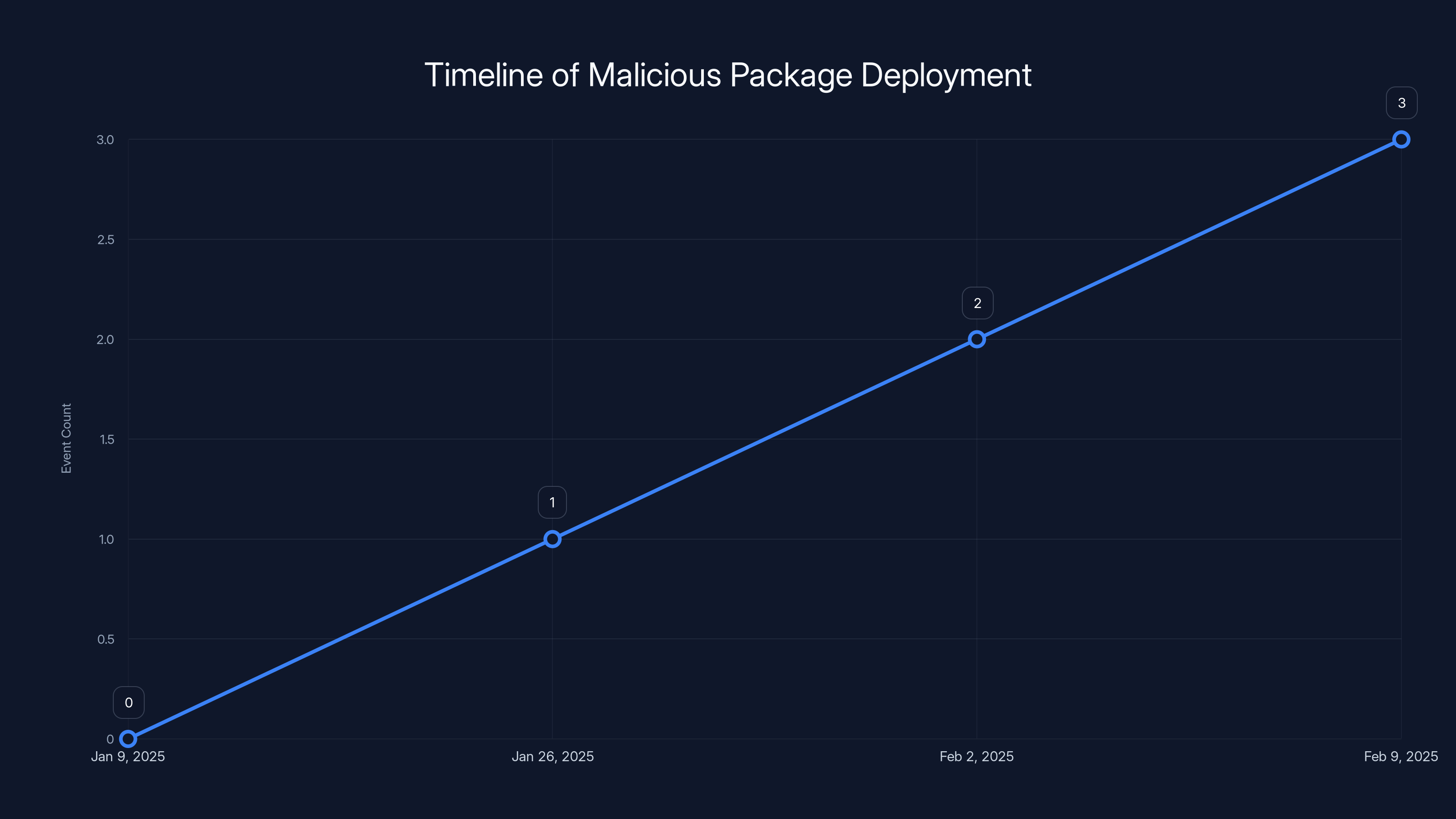

In this case, the domain was registered on January 9, 2025. The malicious package appeared on PyPI just 17 days later.

The PyPI Package Attack

The PyPI version (dydx-v4-client) included the same credential theft function but went significantly further by implementing a Remote Access Trojan (RAT). This is where the attack shifted from theft to active system compromise.

Once installed, this RAT operated as a background daemon thread. Every 10 seconds, it contacted the same C2 (command and control) server at dydx.priceoracle.site. The server could send Python code to the infected machine, which would execute in an isolated subprocess with no visible output to the user.

The authorization token used for this communication was hardcoded: 490CD9DAD3FAE1F59521C27A96B32F5D677DD41BF1F706A0BF85E69CA6EBFE75. This token appears to be a SHA-256 hash, suggesting the attacker used a consistent mechanism for command authentication.

With this level of access, threat actors could:

- Execute arbitrary Python code with user privileges

- Steal SSH keys, API credentials, and source code repositories

- Install additional persistent backdoors on the system

- Exfiltrate any sensitive files accessible to the user

- Monitor user activity and keystrokes

- Modify critical files to maintain persistence

- Pivot laterally to other systems on the network

This goes beyond stealing cryptocurrency. This is full system compromise.

The timeline shows key events: domain registration on Jan 9, 2025, followed by the appearance of malicious packages 17 days later, indicating a coordinated attack strategy. (Estimated data)

The Account Compromise: How Official Packages Became Weapons

The packages were published using official dYdX accounts on both npm and PyPI. This detail is crucial because it represents the deepest level of trust being violated.

This wasn't a case of typosquatting where attackers register a domain like dydx-client and hope someone makes a typo. This was the real thing. The official account. The correct package name. No red flags to trigger warning bells.

How did official accounts get compromised? The public report doesn't provide details, but the likely vectors include:

Credential Compromise: Someone with access to the dYdX npm/PyPI account credentials had their password stolen or their personal device compromised. This could be a developer, a DevOps engineer, or someone with access to shared credentials.

Session Hijacking: An attacker could have stolen a valid session token from an authenticated user, allowing them to publish packages without the original credential.

Social Engineering: Someone at dYdX could have been manipulated into sharing credentials or installing malware.

Insider Threat: While less likely, someone with legitimate access could have intentionally published malicious code.

Regardless of the initial attack vector, the result was the same: an official account that thousands of developers trust was turned into a weapon.

The Pattern: Third Time's Not the Charm

What makes this attack significant isn't just what happened, but the context of what came before.

This is the third documented attack on dYdX or dYdX-related infrastructure in roughly three years.

September 2022: Malicious code was uploaded to the npm repository. The details are sparse in public discourse, but the pattern is identical: supply chain compromise targeting the dYdX developer ecosystem.

2024: The dYdX v3 website was compromised through DNS hijacking. Attackers redirected users to a malicious site that prompted them to sign transactions. Users, thinking they were interacting with the legitimate dYdX interface, unknowingly approved transactions that drained their wallets. This attack didn't steal credentials or install malware. It exploited trust and user confusion.

January 2025: The npm and PyPI packages were compromised, combining credential theft with system compromise.

That's three major incidents in three years. For a crypto exchange handling $1.5 trillion in lifetime volume, this pattern suggests either ongoing targeting by sophisticated threat actors, persistent vulnerabilities in how dYdX manages its infrastructure, or a combination of both.

From an attacker's perspective, the progression makes sense. Each attack learns from the previous one. Each attack targets a different attack surface. And each attack is increasingly stealthy and persistent.

Supply Chain Security: The Weakest Link

This incident exemplifies a broader problem in software development: we've built a trust model that doesn't scale to modern threats.

When you install a package from npm or PyPI, you're not just installing code from a repository. You're executing code from a specific user account, running in your development environment with your credentials, potentially with access to your SSH keys, API tokens, and private repositories.

The repository does perform basic checks. npm scans for known malware signatures. PyPI has policies against intentionally malicious code. But these are reactive defenses. They look for patterns from known malware. They check for obvious red flags.

What they can't detect is legitimate-looking code that does something subtle and malicious. What they can't prevent is account compromise, where the official publisher themselves distributes malicious code.

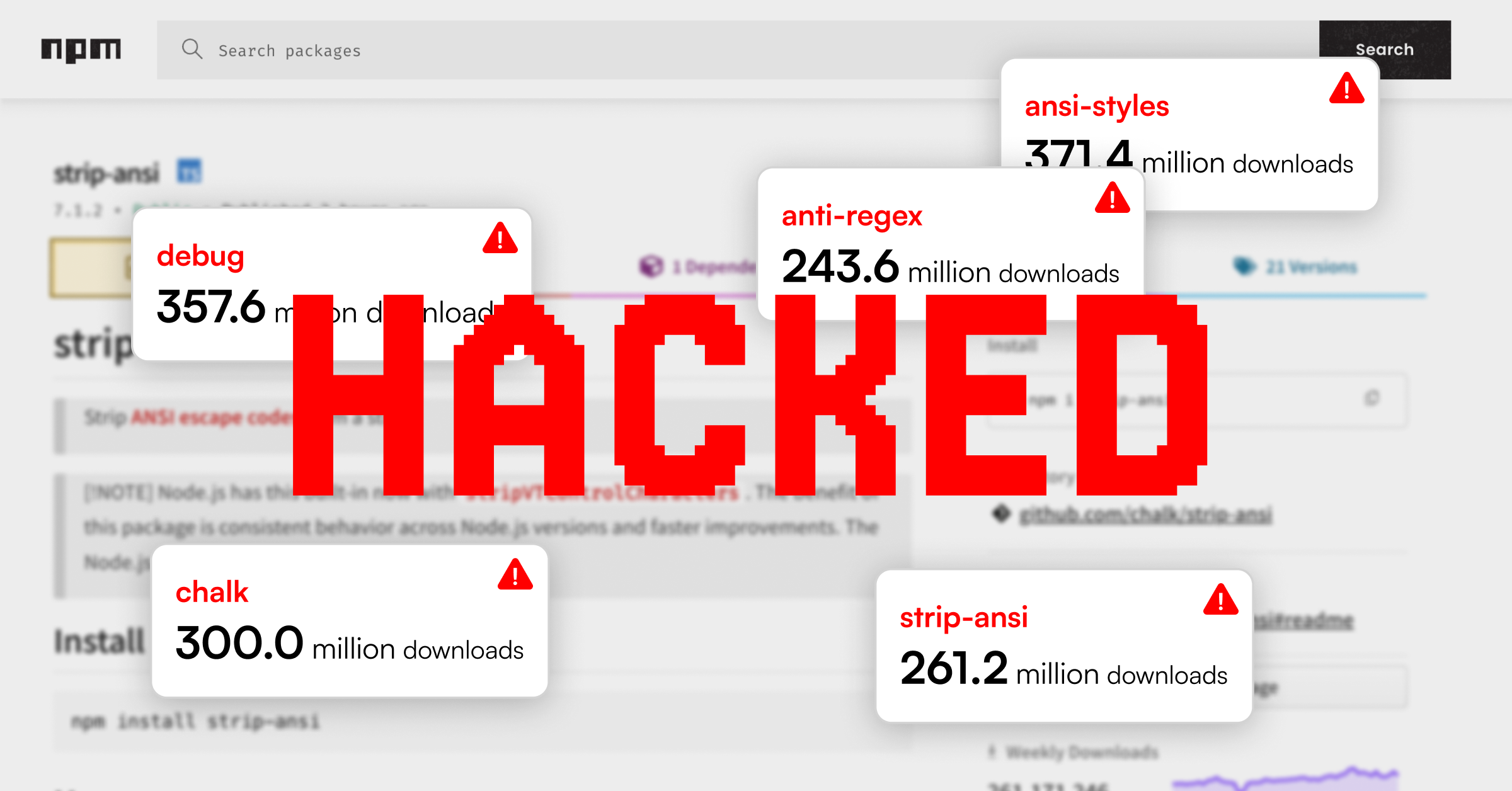

The scale of the problem is staggering. The average JavaScript application depends on hundreds of npm packages. Some applications depend on thousands. Each dependency is another attack surface. Each transitive dependency (dependencies of dependencies) is another point of failure.

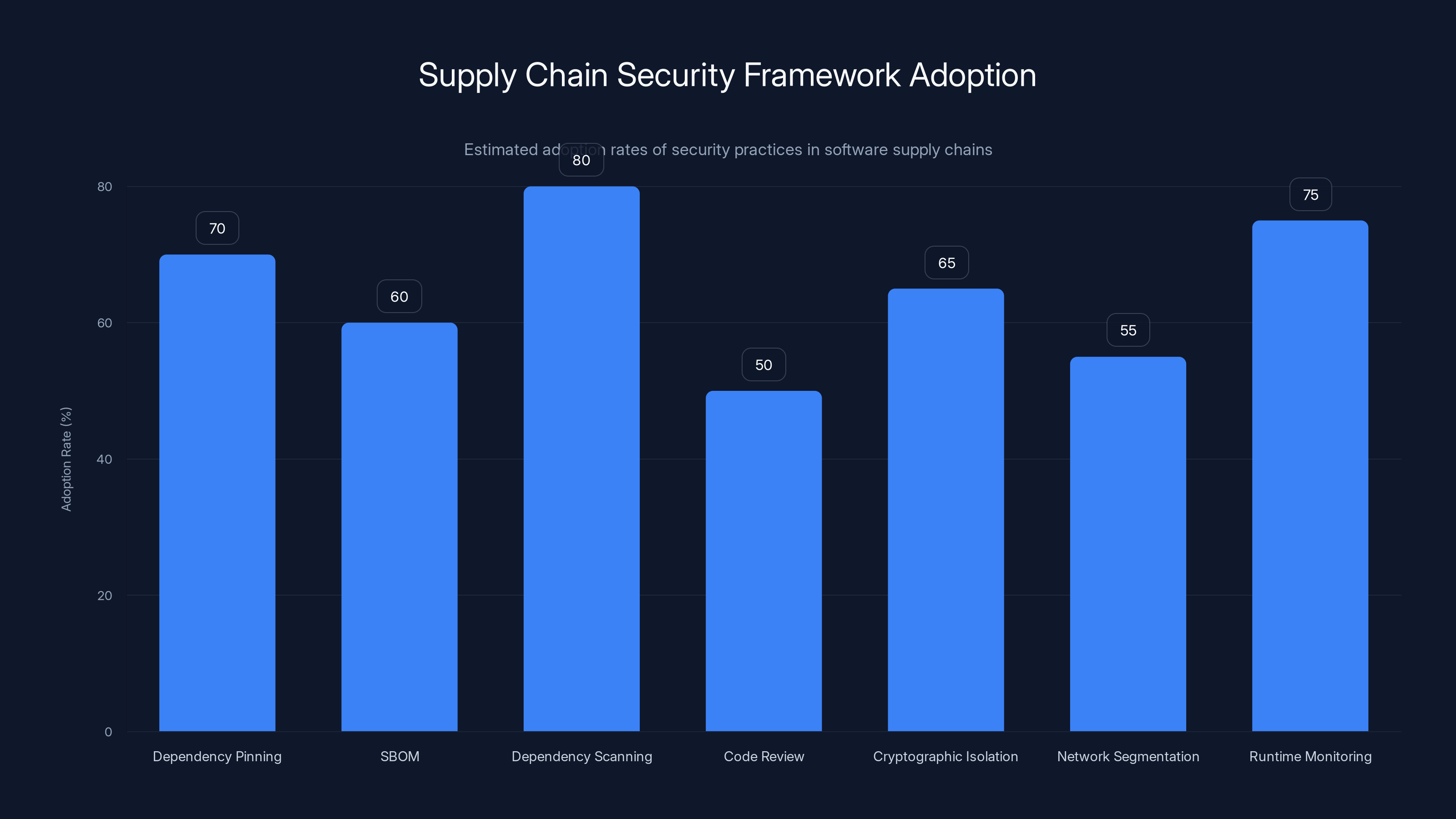

Estimated data shows that dependency scanning is the most widely adopted practice, while code reviews for critical dependencies have the lowest adoption rate. Estimated data.

The Cryptography of Theft: How Seeds Get Exfiltrated

Understanding what was stolen helps understand why this attack was so damaging.

When you create a cryptocurrency wallet, you're given a seed phrase. This is typically a sequence of 12 or 24 words, like "abandon ability able about above absent absorb abstract abuse access accident account accuse."

This seed phrase is not a password. It's not a username. It's a deterministic key generator. If you have the seed phrase, you can mathematically derive every private key for every address in that wallet. If you have the private keys, you own the cryptocurrency.

Moreover, there's no concept of "password reset" in cryptocurrency. You can't call a support team and prove your identity to regain access. Whoever has the seed phrase owns the assets. Period.

When the malicious npm package exfiltrated seed phrases to dydx.priceoracle.site, it captured the complete ability to move funds. The attackers didn't need to wait for users to log in. They didn't need to monitor transactions. They could immediately move every asset in every wallet to their own addresses.

The device fingerprint that was also exfiltrated serves a different purpose. It helps attackers correlate which developer owns which wallet. In a real scenario, an attacker might compromise multiple developers. By comparing device fingerprints, they can map out which ones are the most valuable targets (e.g., someone with access to large trading accounts or significant account balances).

Who Got Hit and How to Know If You're Affected

The compromised packages were:

- npm: @dydxprotocol/v4-client-js

- PyPI: dydx-v4-client

If your project directly imported either of these packages, you're potentially affected. But "potentially" is doing a lot of work here.

You're affected if:

- You installed the malicious version during the window it was available

- Your application or backend processes wallet credentials, seed phrases, or private keys

- The malicious code actually executed in your environment

You might not be affected if:

- You installed these packages but never actually used the functions that trigger the malicious code

- Your environment has network segmentation that prevents outbound connections to attacker domains

- You detected the suspicious activity and removed the packages before the code executed

The challenge is that most developers won't know. The packages appeared legitimate. They had the right names. They came from the right accounts. Unless you were actively monitoring your dependencies or received a security alert, you wouldn't have noticed.

The Damage Assessment: What We Know and Don't Know

Publicly available reports don't specify how many users were actually compromised or how much cryptocurrency was stolen. This is typical for these incidents. Victims often don't want to disclose the extent of their losses for legal, insurance, or privacy reasons.

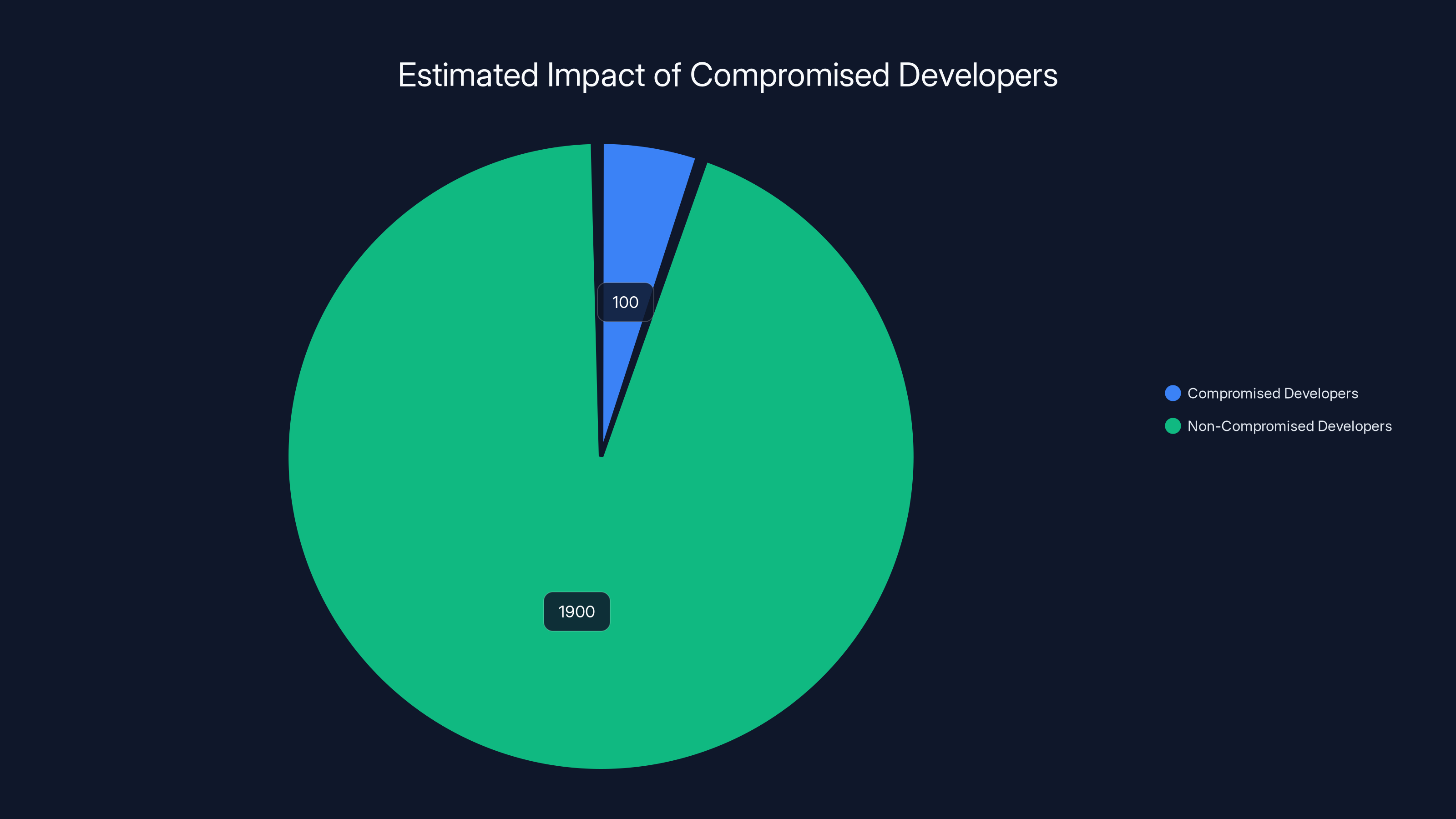

But we can make some educated estimates.

The packages were published to both npm and PyPI, suggesting they were targeting both JavaScript and Python developers. If we assume even a modest adoption rate of, say, 5% of dYdX-using developers, we're talking about potentially hundreds of developers with access to production systems, trading accounts, or personal funds.

For a decentralized exchange handling hundreds of millions daily, even a small percentage of compromised developers could mean significant losses. A developer with API access to a trading account could see balances drained. A backend system with live wallets could have its reserves stolen.

The fact that this is the third attack in three years suggests the attackers are persistent, organized, and potentially successful enough to justify continuing their efforts.

The chart illustrates a pattern of increasing security incidents targeting dYdX over three years, highlighting the evolving nature of attacks.

Technical Indicators of Compromise

If you're trying to determine whether you were affected, here are some technical indicators to check for:

Network Logs: Look for outbound connections to dydx.priceoracle.site during the time period when malicious packages were installed. This is a strong indicator of compromise.

Process Analysis: On Linux/Mac, check for Python daemon processes running in the background. The RAT runs as a background thread, so you might see unusual Python processes with network connectivity.

File System Changes: Check for modified SSH configuration files or new SSH keys added to your authorized_keys. The RAT could have installed persistent backdoors.

Source Code Access: If your source code repositories are accessible from the compromised machine, check git logs for suspicious commits or changes.

Cryptocurrency Account History: If you have wallets or exchange accounts connected to the compromised machine, review transaction history for unauthorized withdrawals.

Terminal History: On Linux/Mac, check .bash_history or .zsh_history for suspicious commands that you don't remember running.

If you find any of these indicators, you have a more serious problem than just stolen seed phrases. You have active system compromise.

Immediate Actions for Developers and Teams

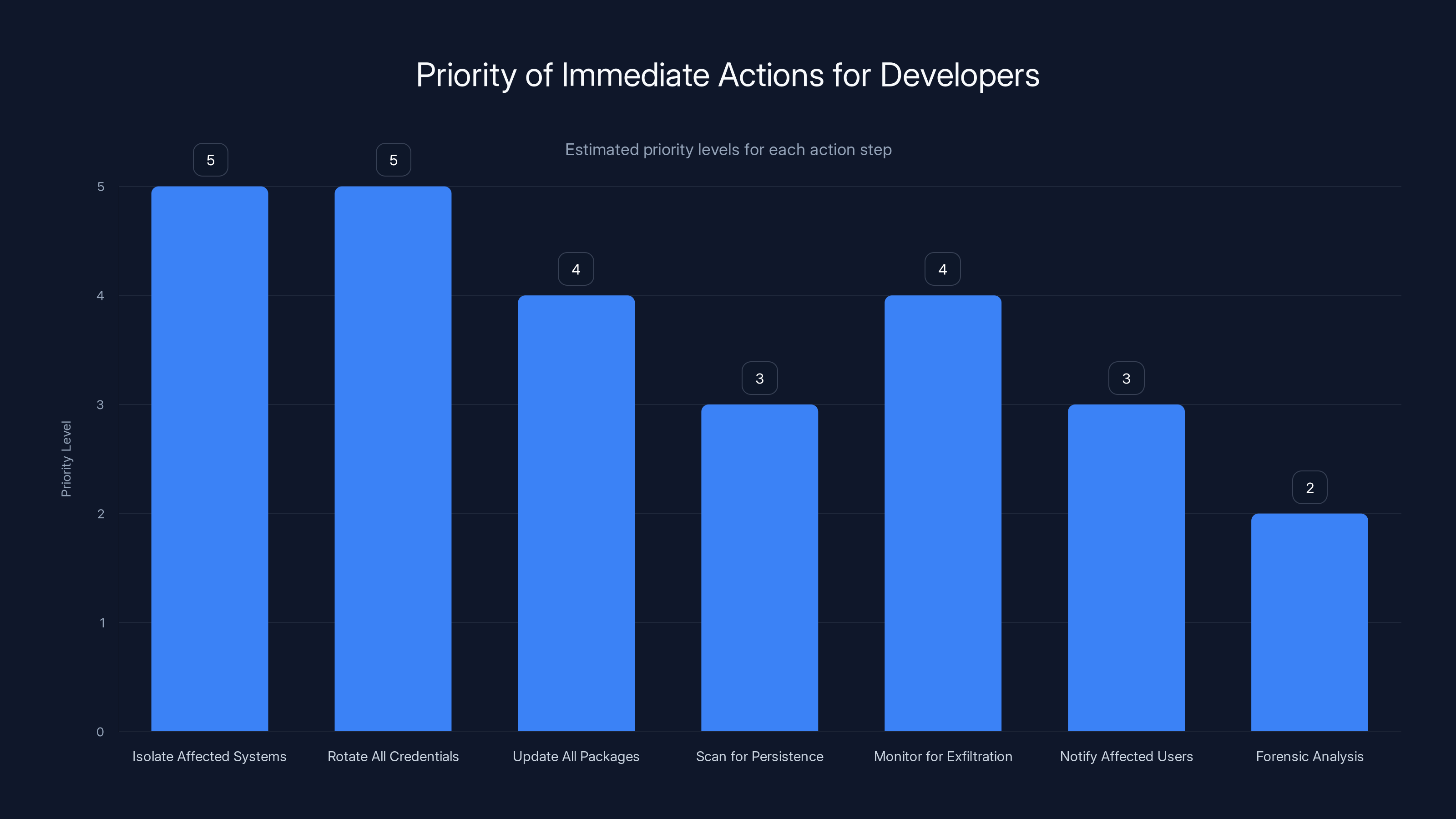

If you used either of these packages, here's what you should do, in order:

Step 1: Isolate Affected Systems If you know a development machine or server installed the malicious package, disconnect it from the network immediately. Don't shut it down yet, as that might destroy evidence. Just disconnect.

Step 2: Rotate All Credentials Assuming the worst, assume every credential that existed on that machine is compromised. This includes:

- SSH keys

- API tokens and API keys

- Database passwords

- Private repository credentials

- Cryptocurrency wallet credentials

- Any other secrets stored on the machine

Generate new credentials and deploy them to all affected systems.

Step 3: Update All Packages Update to the latest, safe versions of the dYdX client libraries from npm and PyPI. Verify that the version number has been incremented past the malicious versions.

Step 4: Scan for Persistence Run a full malware scan on affected systems. Standard antivirus tools might not catch sophisticated RATs, so consider using a security firm if you suspect serious compromise.

Step 5: Monitor for Exfiltration If you believe seed phrases or credentials were stolen, assume they've been exfiltrated. Move any cryptocurrency or assets to newly generated wallets. This is the only way to guarantee attackers can't access funds.

Step 6: Notify Affected Users If you operate a service affected by this, notify your users. Be transparent about what happened and what they should do.

Step 7: Forensic Analysis Once you've isolated systems, consider bringing in a forensics firm to analyze what happened, when it happened, and what data was accessed. This information is crucial for insurance claims and regulatory requirements.

Long-Term Defense: Supply Chain Security Framework

This incident is a wake-up call about the fragility of our software supply chain. Long-term protection requires multiple layers of defense.

Dependency Pinning and Lock Files Always use lock files (package-lock.json for npm, poetry.lock for Python) to pin exact versions of dependencies. Never rely on version ranges like "^1.0.0" in production environments. This prevents unexpected updates from introducing malicious code.

Software Bill of Materials (SBOM) Maintain a detailed inventory of every dependency in your project. Tools like CycloneDX or SPDX can generate these automatically. Review them regularly for new dependencies and unexpected changes.

Dependency Scanning

Use automated tools to scan your dependencies for known vulnerabilities. npm has built-in vulnerability scanning with npm audit. Python projects can use tools like Safety or Bandit. But remember, these only catch known vulnerabilities, not zero-days.

Code Review for Critical Dependencies For dependencies that handle sensitive data (like cryptographic libraries or authentication code), consider doing code reviews on major version updates. This is time-consuming but justified for high-risk code.

Cryptographic Isolation For applications that handle wallet credentials, private keys, or sensitive secrets, use cryptographic isolation. Store secrets in dedicated secret management systems (like HashiCorp Vault, AWS Secrets Manager, or Azure Key Vault). Never store secrets in environment variables or source code.

Network Segmentation If a development machine is compromised, it shouldn't have access to production systems. Use network segmentation to limit lateral movement. Development machines might not need outbound internet access to all domains, which could have prevented exfiltration in this case.

Runtime Monitoring Instrument your applications and systems to detect suspicious activity at runtime. Monitor network connections, file access, and process execution. If you see unexpected outbound connections or unusual system calls, alert immediately.

Threat Modeling Think through where your critical data lives and who can access it. For cryptocurrency applications, this means asking: "What if a developer's machine is compromised? What's the blast radius?" The answer to that question should inform your security architecture.

Estimated data suggests that out of 2000 developers, around 100 could be compromised, highlighting the potential risk to significant funds. Estimated data.

The Broader Context: Package Manager Security

This isn't an npm-specific problem or a Python-specific problem. Every package manager has similar vulnerabilities.

npm is the largest package registry by far, with over 2.5 million packages. npm has been hit by high-profile supply chain attacks before, including the incident where the "left-pad" package was removed and then restored, breaking countless applications that depended on it.

PyPI has seen similar attacks, most notably the "torrent-client" package which tried to mine cryptocurrency on users' machines.

Ruby Gems, Maven, NuGet, and others all have the same fundamental problem: they facilitate distributed package installation with limited verification.

The package managers themselves have improved their security posture. npm now requires two-factor authentication for accounts publishing highly-downloaded packages. PyPI has improved its security policies. But the fundamental model remains unchanged.

What's changed is the sophistication and prevalence of attacks. As organizations have moved to software-defined infrastructure and cloud-native applications, the value of compromising dependencies has skyrocketed.

Cryptocurrency-Specific Risks

Cryptocurrency applications face unique risks because the value proposition of successful attacks is so clear: direct theft of financial assets.

When you compromise a fitness tracking app or a weather service, you might steal personal data. The attacker has to monetize that data somehow. But when you compromise cryptocurrency wallet software, the attacker can immediately move funds to their own accounts.

This economic incentive creates an asymmetry. Attackers will invest significant resources into compromising high-value targets. They'll adapt their tactics based on what works. They'll be persistent.

For dYdX specifically, the repeated targeting is likely a combination of factors:

- High financial incentive: The exchange handles billions in volume

- Developer access to live wallets: dYdX applications often handle real credentials

- Public attack surface: The libraries are open source and widely used

- Apparent vulnerability pattern: Three attacks in three years suggests some developers at dYdX might not be following security best practices

The Human Element

Technical controls matter, but this attack also highlights the human elements of security.

Developers trust official packages. They assume that if something comes from an official npm account, it's safe. This assumption is usually correct, but when it's wrong, the consequences are massive.

Developers don't typically read the code they install. How many of us have actually looked at the source code for packages we depend on? Most people haven't. We trust the package manager, we trust the community, and we assume that malicious code would be caught.

But the packages in this attack were designed to be stealthy. They did their malicious work in functions that might only be called under certain conditions. They didn't crash. They didn't create obvious side effects. They just silently stole credentials.

There's also a trust problem with multi-person teams. If a senior engineer says, "Yes, we use this package, it's safe," other team members usually don't question it. Authority and experience create trust, which creates risk.

Improving security at scale requires changing these human behaviors. It means:

- Transparency: Making dependency choices transparent across teams

- Accountability: Clear ownership of dependency decisions

- Training: Helping developers understand supply chain risks

- Culture: Creating an environment where questioning security decisions is expected and valued

Isolating affected systems and rotating credentials are top priorities, followed by updating packages and monitoring for exfiltration. Estimated data.

Lessons for Other Exchanges and Applications

If you operate a cryptocurrency exchange, trading platform, or financial application, this incident should inform your security strategy.

Assume dependencies will be compromised. It's not a question of if, but when. Your security architecture should be designed with this assumption in mind.

Isolate secrets from development environments. Developers shouldn't have access to production wallet credentials. Use separate, highly-secured systems for production operations. Use role-based access control to limit who can access what.

Implement defense in depth. If a dependency is compromised, it shouldn't be enough to steal user funds. Require multiple factors (geolocation checks, time delays, manual approvals) for large transactions.

Monitor your supply chain. Know what's in your dependencies. Track when they're updated. Have a process for evaluating updates before deploying them.

Segment your network. Development machines shouldn't have direct access to production systems. Use network segmentation, VPN, and other controls to prevent lateral movement.

Test your incident response. If you were hit by an attack like this tomorrow, do you know what you'd do? Have you practiced? Can you recover quickly?

These practices are more tedious than just pulling in the latest version of a package and shipping it. But the cost of not doing them is potentially catastrophic.

The Path Forward for dYdX

For dYdX specifically, the repeated attacks raise questions about their security posture.

One attack could be bad luck. Two attacks might be a pattern. Three attacks suggest systemic issues.

They need to:

- Conduct a comprehensive security audit of their entire development and deployment pipeline

- Implement strict access controls for publishing packages

- Require two-factor authentication for all developer accounts

- Separate sensitive credentials from development environments

- Implement continuous monitoring of their package repositories

- Create incident response playbooks for supply chain compromises

- Communicate transparently with users about what happened and how they're fixing it

The cryptocurrency community is watching. Another attack would be devastating for user trust.

Prevention at Scale: Building Resilient Systems

The ultimate lesson here is that we need to move beyond reactive security to proactive resilience.

Reactive security asks: "How do we prevent attacks?" The answer involves firewalls, antivirus, intrusion detection, and access controls. All important. All insufficient.

Resilient security asks: "How do we minimize damage when attacks succeed?" The answer involves compartmentalization, redundancy, monitoring, and rapid recovery.

For developers building applications that handle sensitive data, the implications are clear.

You cannot trust external code completely. You should assume that at some point, code you depend on will be compromised. The question is whether your system can survive that compromise.

If you're building a trading bot, don't give it credentials with access to your entire portfolio. Give it access to a small trading account with limited funds.

If you're building a backend system that processes user transactions, require multiple signatures for large transactions. Use time-locks that prevent immediate execution. Implement monitoring that alerts when unusual patterns occur.

These practices are borrowed from traditional finance because traditional finance learned through experience that trusting a single system or a single person is dangerous.

Software development is starting to learn the same lesson.

FAQ

What exactly is a seed phrase and why is it so valuable to attackers?

A seed phrase is a sequence of 12 or 24 words that serves as the master key for a cryptocurrency wallet. It's not encrypted by default, and anyone with the seed phrase can derive every private key associated with that wallet. Unlike a password, there's no recovery mechanism or fraud reversal in cryptocurrency. If someone has your seed phrase, they own your funds, and there's nothing you can do to reverse it. This makes seed phrases extremely valuable to attackers, and exfiltrating them is functionally equivalent to stealing all associated cryptocurrency.

How can developers know if their systems were compromised by these malicious packages?

Developers should check their package-lock.json (for npm) or poetry.lock (for Python) files to see what versions they installed. They should then compare these versions to the npm or PyPI package history to determine if they installed a malicious version during the window it was available. Additional indicators of compromise include outbound network connections to dydx.priceoracle.site in network logs, unexpected Python daemon processes running in the background, or unauthorized SSH keys in their authorized_keys file.

Why is it so difficult for package repositories to prevent these types of attacks?

Package repositories like npm and PyPI face a fundamental tension between security and usability. If they were overly restrictive, they'd prevent legitimate developers from publishing code. Instead, they rely on account security, which can be compromised if a developer's credentials are stolen or their machine is compromised. Additionally, detecting malicious code automatically is extremely difficult because malicious code can be written to look like legitimate code and might only activate under certain conditions that are hard to detect programmatically.

What's the difference between the npm attack and the PyPI attack in this incident?

Both attacks included credential theft, but the PyPI version included an additional Remote Access Trojan (RAT) that allowed attackers to execute arbitrary Python code on infected systems. The RAT could install persistent backdoors, steal SSH keys and API credentials, exfiltrate source code, and pivot to other systems on the network. This made the PyPI attack more severe because it wasn't just about stealing cryptocurrency credentials, but about gaining full system compromise.

Should cryptocurrency exchanges stop using open-source libraries from npm and PyPI?

Completely avoiding public package repositories isn't practical in modern software development, but it's a reasonable approach for certain high-security scenarios. The better approach is to assume that dependencies will eventually be compromised and design systems accordingly. Use cryptographic isolation so that compromising a dependency isn't sufficient to steal funds. Implement network segmentation to limit lateral movement. Use runtime monitoring to detect suspicious activity. Require multiple factors for critical operations. These practices create resilience even if dependencies are compromised.

How do developers balance using modern packages with security concerns?

This is one of the hardest problems in modern development. Developers need to use external packages for productivity and to avoid reinventing the wheel. But every dependency introduces risk. The solution is a combination of practices: carefully evaluate dependencies before using them, use lock files to pin exact versions, implement dependency scanning tools, monitor dependencies for updates, and most importantly, design your system assuming dependencies will eventually be compromised. For critical applications handling sensitive data, it might be worth reducing dependencies and implementing core functionality in-house.

What's the difference between this attack and traditional malware?

Traditional malware is typically distributed through phishing emails, compromised websites, or drive-by downloads. This attack was distributed through legitimate package repositories using compromised official accounts. This is more insidious because users had no reason to distrust the source. Additionally, this attack leveraged the trust relationships in modern software development, where developers routinely install code from third parties without reviewing it.

Is two-factor authentication enough to prevent account compromise?

Two-factor authentication significantly raises the bar for account compromise, but it's not foolproof. Attackers can compromise it through phishing (stealing both password and one-time codes), SIM swapping (convincing a phone carrier to transfer a phone number to a device controlled by the attacker), or by gaining physical access to hardware keys. For high-security applications, two-factor authentication is essential, but it should be combined with other security measures like IP whitelisting, unusual activity detection, and hardware security keys instead of SMS-based authentication.

What should organizations do if they discover they were affected by these attacks?

The immediate priority is to isolate affected systems from the network to prevent further damage or data exfiltration. Next, rotate all credentials that could have been exposed, including SSH keys, API tokens, and cryptocurrency wallet credentials. Move any cryptocurrency to newly generated wallets. Update to clean versions of the affected packages. Then conduct a forensic analysis to determine what was accessed, when it was accessed, and what damage occurred. Finally, if you operate a service used by others, notify affected users transparently about what happened.

How does this incident affect the broader cryptocurrency ecosystem?

This incident demonstrates that the cryptocurrency ecosystem is an attractive target for sophisticated attackers due to the direct financial incentive and the irreversible nature of transactions. It also highlights that distributed systems are not automatically more secure than centralized systems. While dYdX is technically decentralized, its development and tooling are more centralized. The repeated attacks on dYdX also suggest that some organizations in the cryptocurrency space might not be implementing sufficient security controls, which could encourage continued targeting.

Key Takeaways

The dYdX supply chain attack reveals critical vulnerabilities in how modern software is developed and distributed. Here are the essential lessons:

Security is a supply chain problem. Your application is only as secure as your weakest dependency. Assume that external code will eventually be compromised and design accordingly.

Trust is a liability. Official accounts can be compromised. Well-known packages can be malicious. Legitimate-looking code can be malicious. Design your systems assuming bad actors can introduce code anywhere in your dependency chain.

Cryptography requires isolation. Applications that handle sensitive cryptographic material (like wallet seeds or private keys) should isolate that data from general-purpose code. Use dedicated systems with limited attack surface for cryptographic operations.

Patterns indicate systemic problems. Three attacks on dYdX in three years isn't random bad luck. It indicates either particularly valuable targets (which it is) or persistent security gaps in their development processes.

Defense requires multiple layers. No single security control will prevent all attacks. Require defense in depth: network segmentation, runtime monitoring, cryptographic isolation, credential rotation, and rapid response capabilities.

Incident response matters more than prevention. You cannot prevent all attacks. But you can design systems to survive them. Have playbooks. Test them. Be prepared to recover quickly.

The cryptocurrency industry is starting to understand these lessons. The question is whether the broader software development community will learn them before suffering similar attacks.

Looking Forward: Building Trustless Systems

One of the ironies of this incident is that cryptocurrency was supposed to create trustless systems. The whole point of blockchain technology is that you don't need to trust a central authority. You trust mathematics and cryptography instead.

But the tools and libraries used to interact with these trustless systems are deeply trust-dependent. You have to trust the developers who write the libraries. You have to trust the security of the package repositories. You have to trust the machines where you run the code.

The long-term solution isn't to trust fewer things. It's to design systems where trust failures are compartmentalized and where the impact of any single compromise is limited.

For cryptocurrency applications, this means:

- Hardware wallets for storing large amounts of cryptocurrency, so that even if software is compromised, funds can't be moved without physical approval

- Multisignature wallets that require multiple people or systems to approve transactions

- Timelock mechanisms that prevent immediate transactions, giving time to detect compromise

- Geolocation checks that alert if funds are being accessed from unusual locations

- Spending limits on accounts to reduce the damage from a single compromise

For software development, this means:

- Open-source code that can be audited by the community

- Code signing so that you can verify code comes from who you think it does

- Reproducible builds so that you can verify the binary matches the source code

- Sandboxed execution so that code runs in a limited environment

- Capability-based security where code only has access to what it needs

We're not there yet. Most software doesn't have these protections. But incidents like the dYdX attack are pushing the industry in that direction.

The developers and organizations that implement these practices now will be the ones that survive the inevitable attacks of the future. Those that don't will learn the hard way.

Related Articles

- Notepad++ China Hack: What Happened & How to Protect Yourself [2025]

- OpenClaw AI Assistant Security Threats: How Hackers Exploit Skills to Steal Data [2025]

- DNS Malware Detour Dog: How 30K+ Sites Harbor Hidden Threats [2025]

- Why America's $12B Mineral Stockpile Proves the Future Is Electric [2025]

- NGINX Server Hijacking: Global Traffic Redirect Campaign [2025]

- Password Security Guide: Why Strong Credentials Matter in 2025

![dYdX Supply Chain Attack: How Malicious NPM Packages Emptied Wallets [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/dydx-supply-chain-attack-how-malicious-npm-packages-emptied-/image-1-1770417366732.jpg)