Why Your Password Game Needs a Complete Overhaul Right Now

Last week, McDonald's did something unexpected. They launched a campaign warning people to stop using burger-related passwords like "bigmac," "happymeal," and "mcnuggets." The humorous posters and videos went viral because they hit on something uncomfortable: millions of people are still protecting their most sensitive accounts with passwords tied to their lunch order. According to TechRadar, this campaign was driven by the prevalence of these passwords in data breaches.

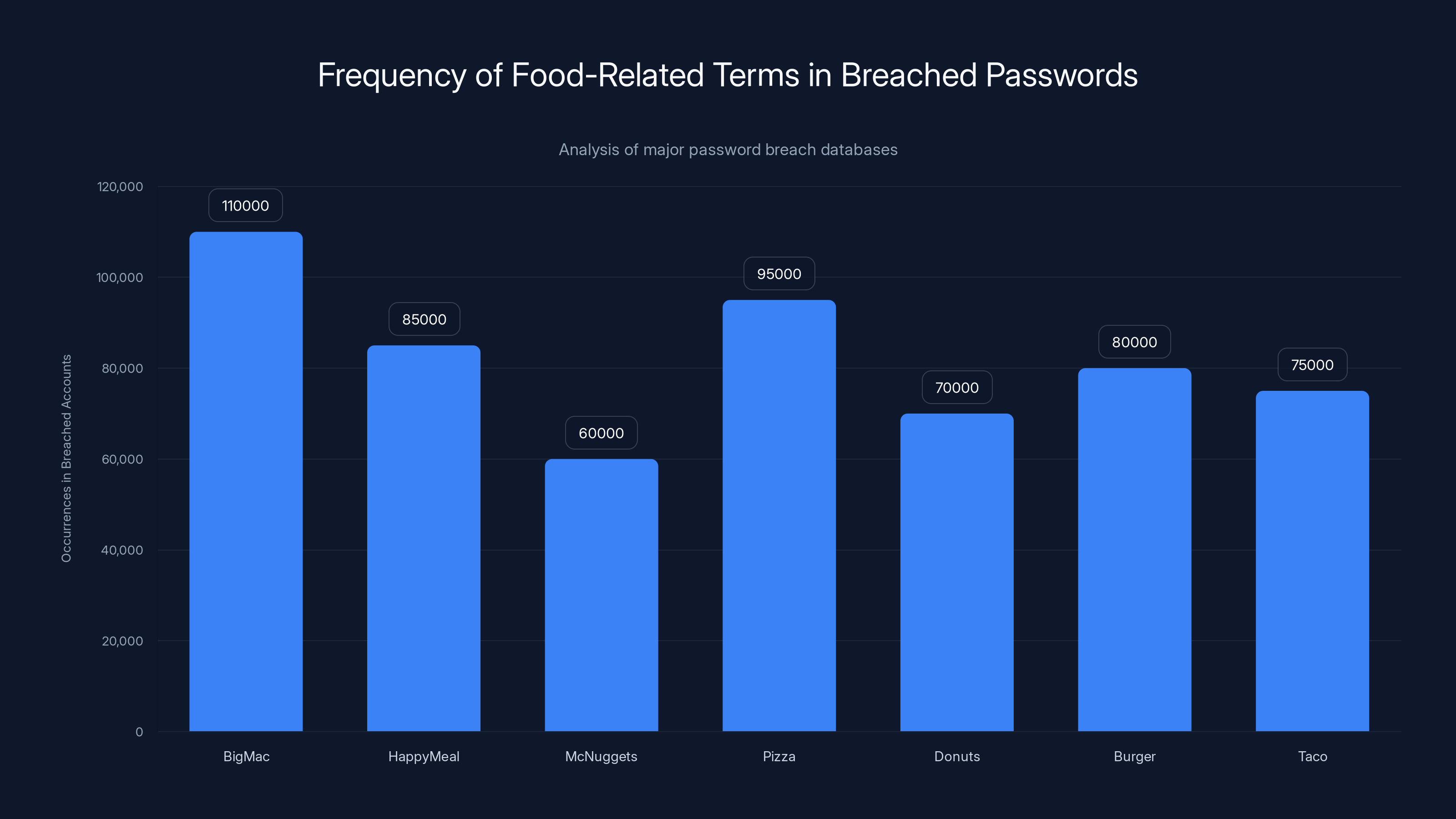

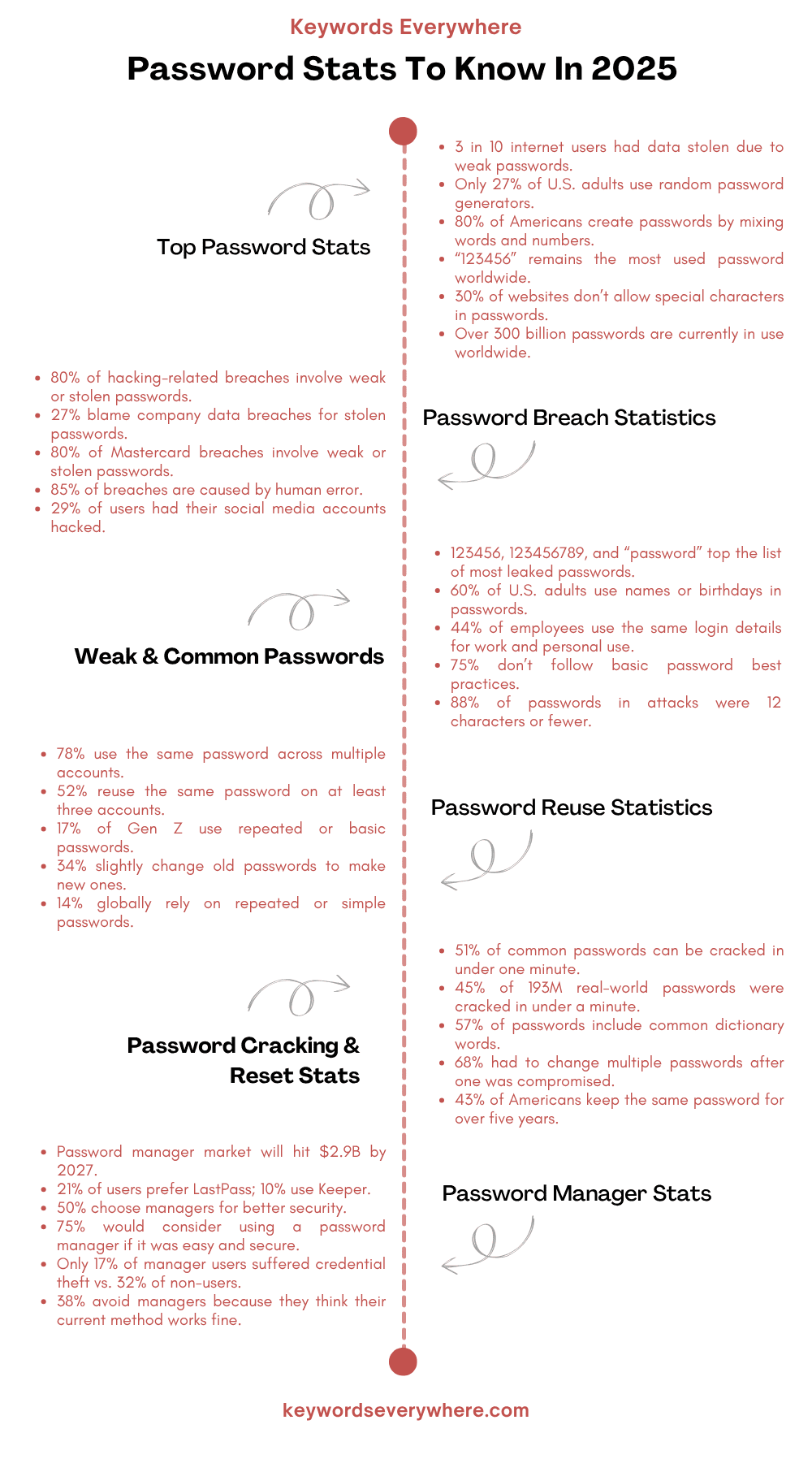

Here's the thing that should keep you up at night: these passwords aren't just common among casual internet users. They showed up in over 110,000 compromised accounts according to data from major breach databases. That's not a rounding error. That's a pattern.

You might think you're safe because your password uses creative substitutions, like "B1g M@c" instead of "bigmac." You'd be wrong. Modern cracking tools already account for predictable character replacements. When attackers run brute-force attempts, they test these variations automatically. The "complexity" you added? It slows them down by maybe a second.

The uncomfortable truth is this: decades of password advice has failed to change behavior. Password managers exist. Multi-factor authentication exists. Strong credential hygiene is well-documented. Yet people continue to build passwords around familiar words because memorization still feels safer than management.

This article digs into why weak passwords persist, how they fail in real breaches, what actually stops attackers, and the practical systems that finally work. You'll see specific examples of compromised credentials, understand the math behind password cracking, and get a clear roadmap for protecting your accounts without sacrificing convenience.

By the end, you'll understand why McDonald's felt compelled to launch this campaign in the first place, and why the stakes are higher than most people realize.

TL; DR

- 110,000+ breaches involved food-related passwords: Terms like "bigmac" and "happymeal" appear in major data breaches, proving weak credentials remain a critical vulnerability.

- Character substitutions no longer provide security: Modern cracking tools routinely test "L33t speak" variations, making "P@ssw0rd" nearly as weak as "password."

- Weak passwords cost enterprises millions: A single compromised admin account can lead to lateral movement, ransomware deployment, and data theft affecting thousands of users.

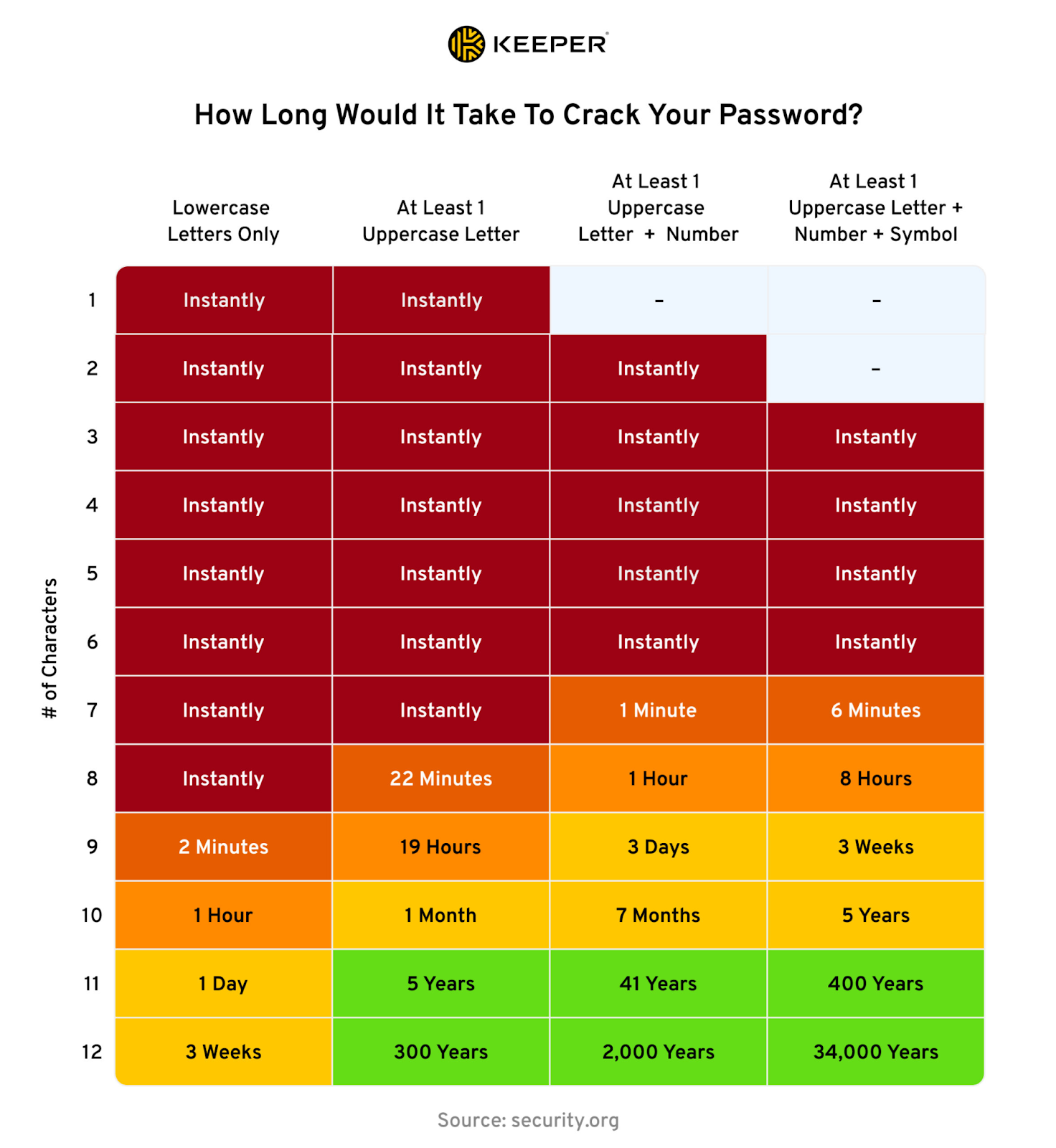

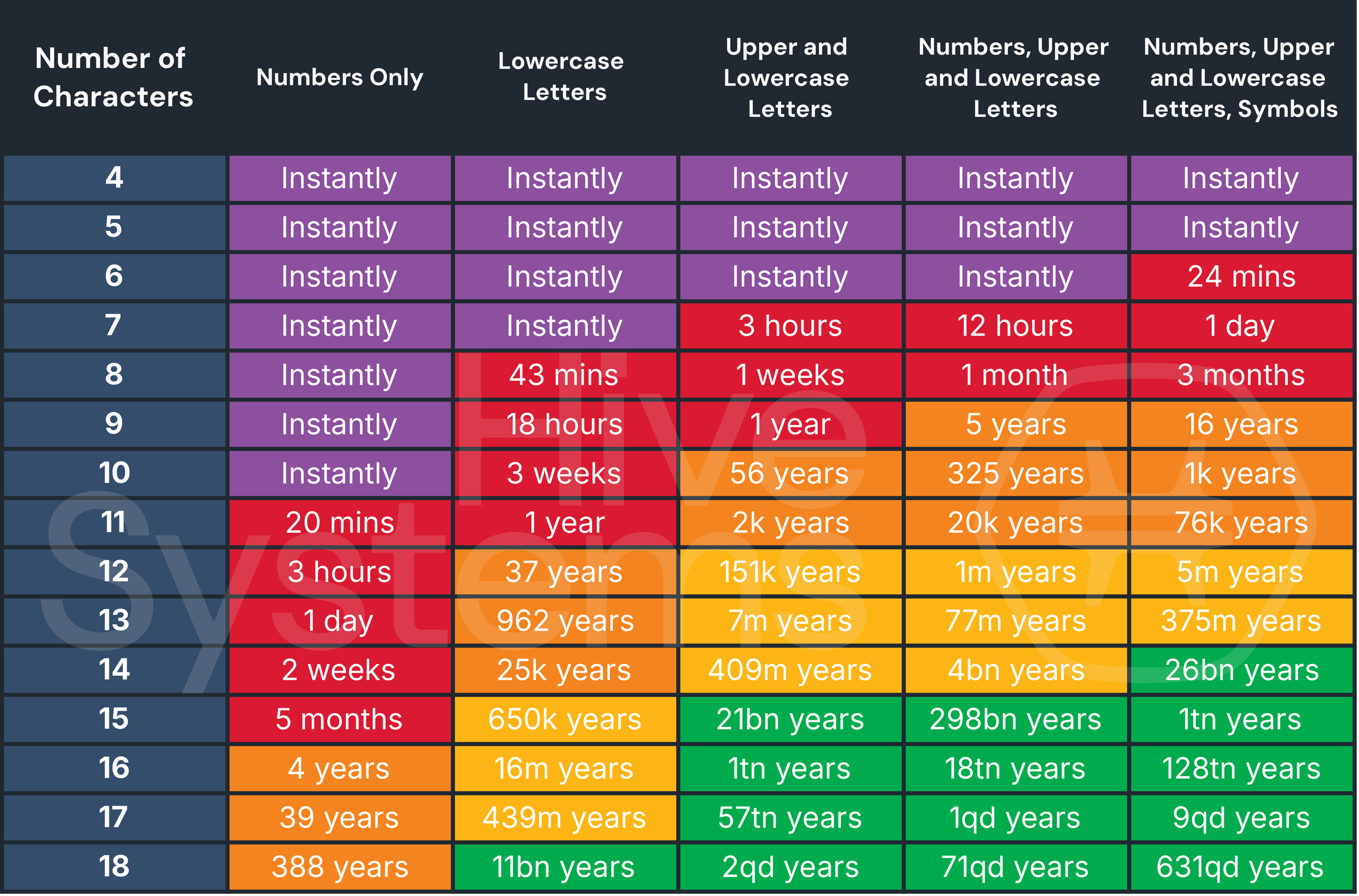

- Password length matters more than complexity: A 15-character random string beats a 12-character "complex" password with mixed cases and symbols by orders of magnitude.

- Password managers are non-negotiable: The only practical way to maintain unique, strong passwords across 100+ accounts without reuse or memorization.

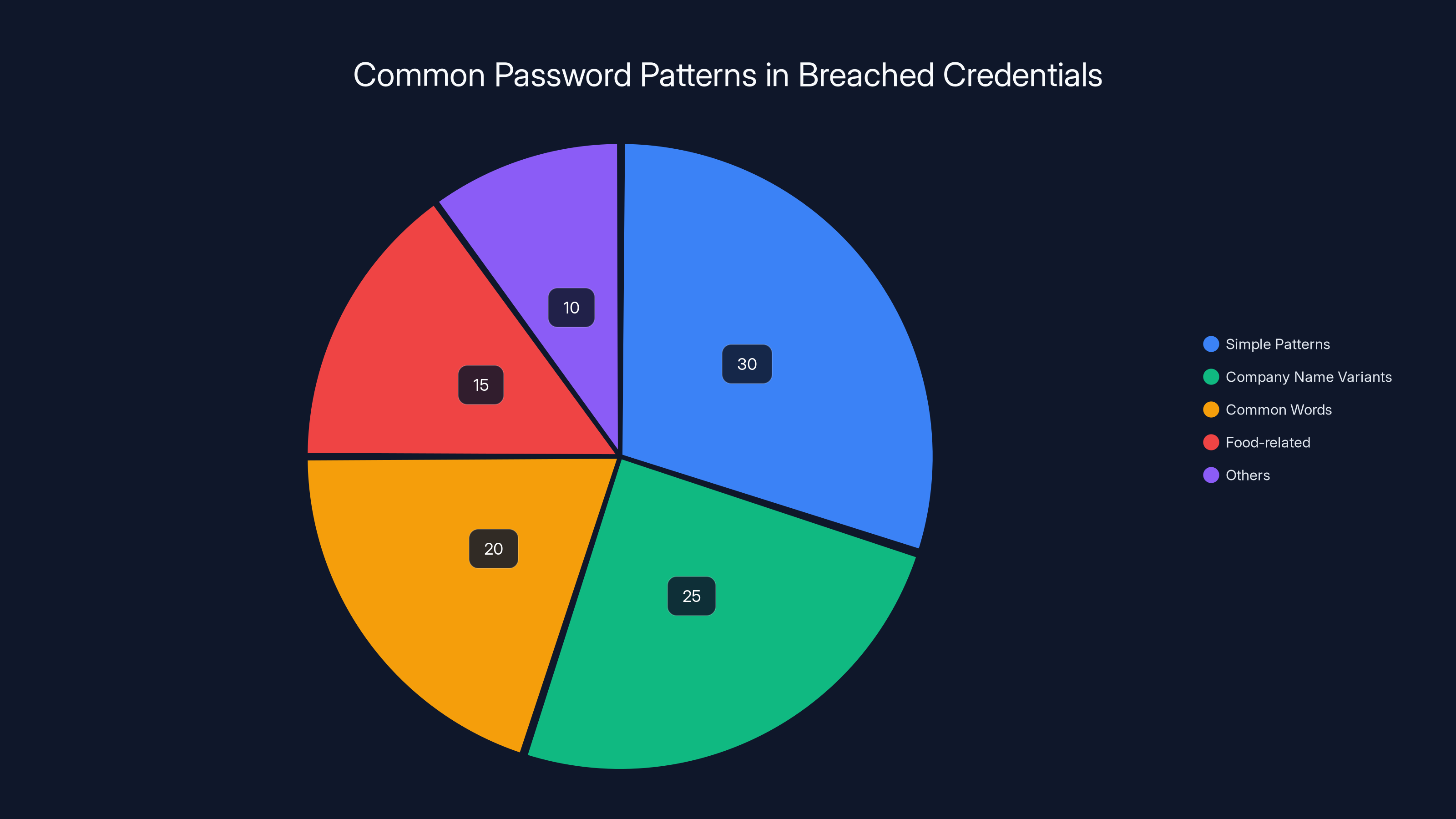

Estimated data shows that simple patterns and company name variants are the most common in breached credentials, highlighting the risk of predictable passwords.

The Scale of the Problem: Why McDonald's Campaign Exists

McDonald's didn't launch this campaign out of boredom. They did it because the data was impossible to ignore.

When security researchers analyzed compromised password databases, they found food-related terms appearing thousands of times. Not hundreds. Thousands. "Big Mac" and variations appeared in over 110,000 breached accounts. "Happy Meal" showed up frequently. Lesser-known items like "mcnuggets" proved popular too. The pattern extended beyond McDonald's: "pizza," "donuts," "burger," and "taco" all appeared repeatedly in password breach databases.

What makes this particularly damaging is that these aren't obscure breaches. We're talking about incidents that affected major consumer platforms, email providers, social networks, and financial services. If someone used "bigmac" as their Netflix password in 2019, and Netflix got breached, that credential could have been sitting in attacker databases for years. When that person reuses the same password on their bank account, email, or work system, one old breach cascades into multiple current vulnerabilities.

The numbers get worse when you factor in password variation. Adding "123" to the end ("bigmac123") or substituting "4" for "a" ("bigm4c") doesn't create new security. These variations appear in pre-built cracking dictionaries. Modern password-cracking tools don't try passwords one at a time anymore. They run through entire lists of known passwords and known variations simultaneously.

What's particularly revealing is that this weakness crosses every demographic. Younger users who grew up with technology. Older users less comfortable online. Enterprise employees with security training. Government workers with access to sensitive systems. Education administrators managing student data. All of them appear in these breach databases using weak, memorable passwords as their primary defense.

McDonald's campaign succeeded because it didn't lecture. It didn't guilt. It used humor to make an uncomfortable point: if McDonald's thinks your password is bad, your password is definitely bad.

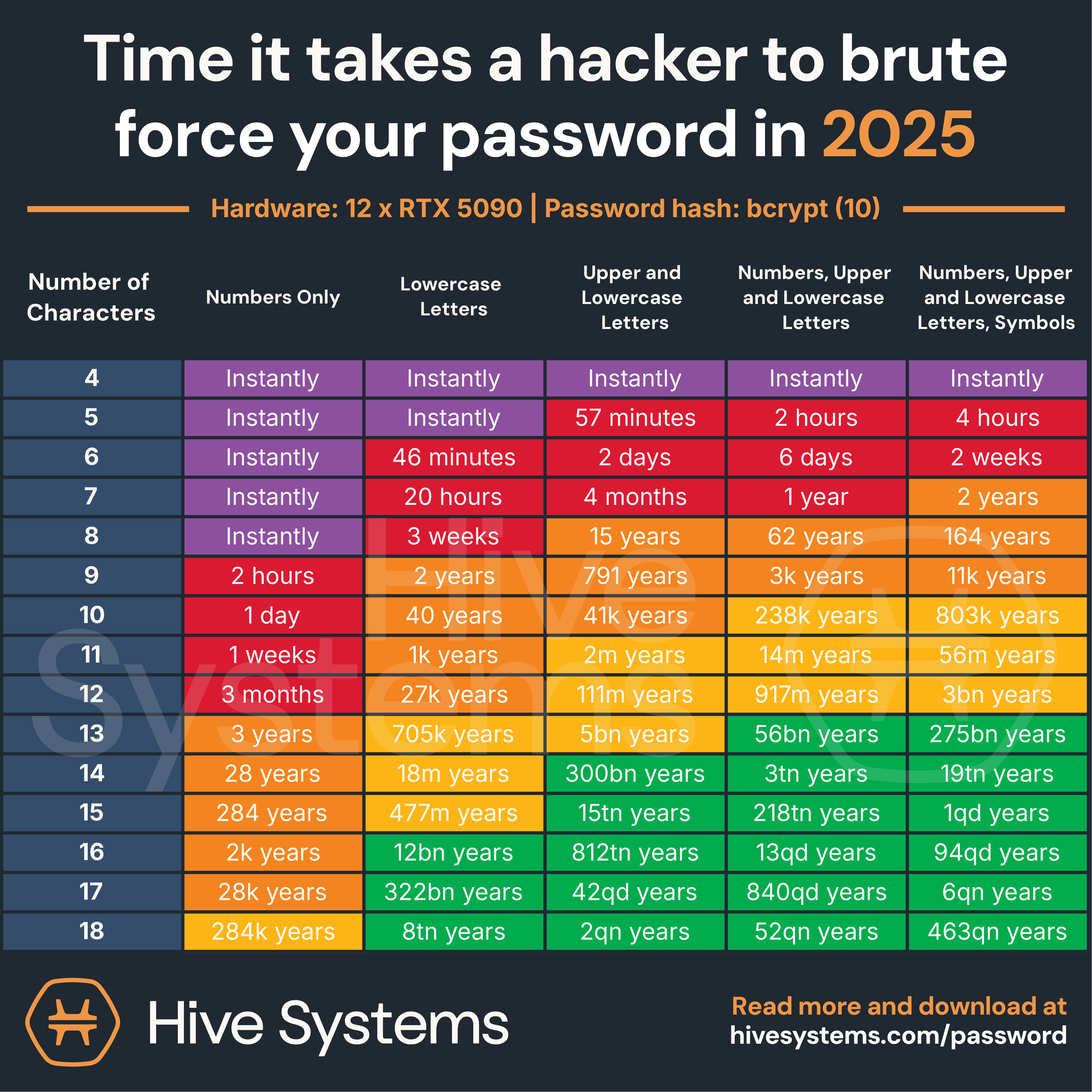

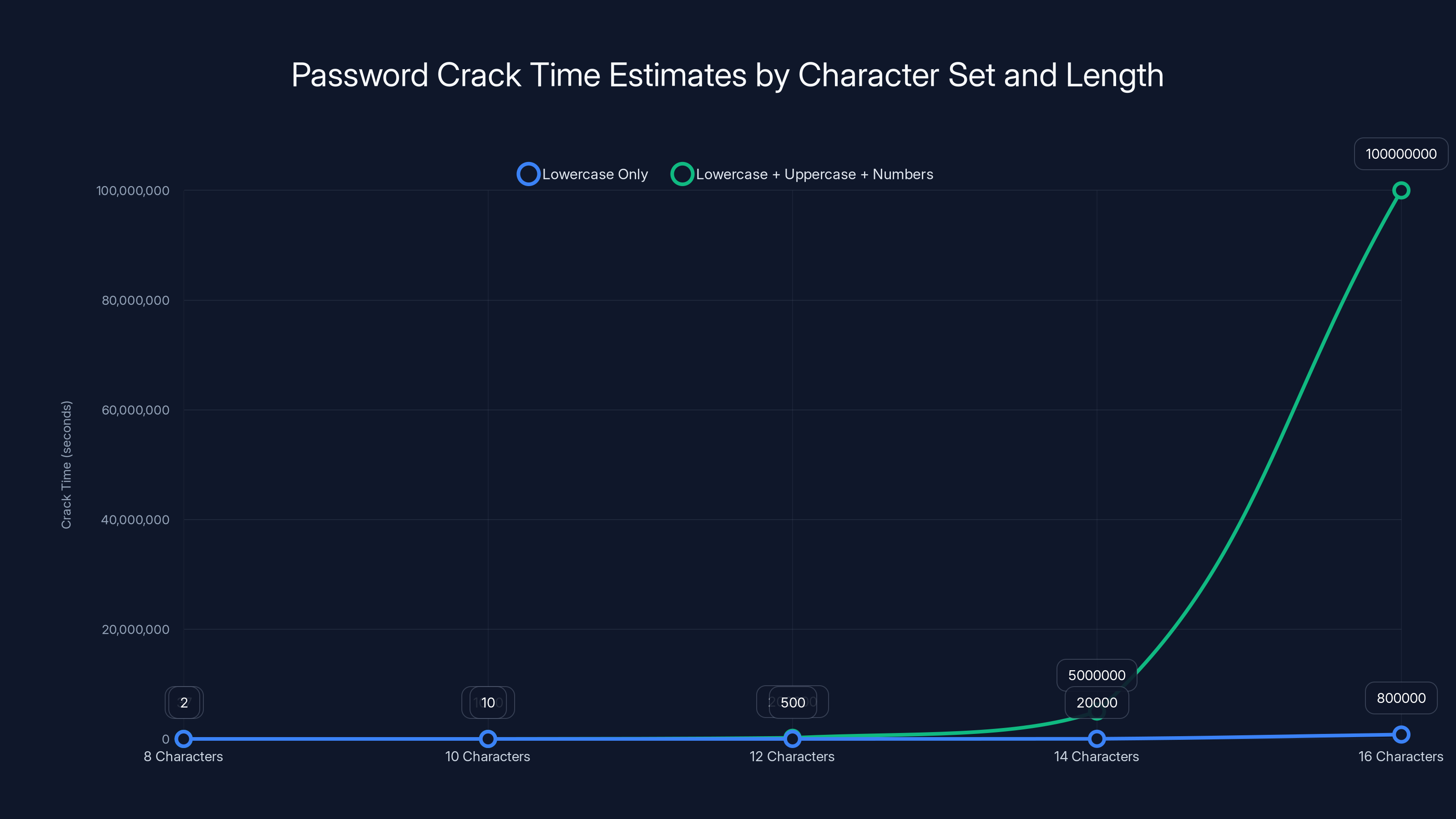

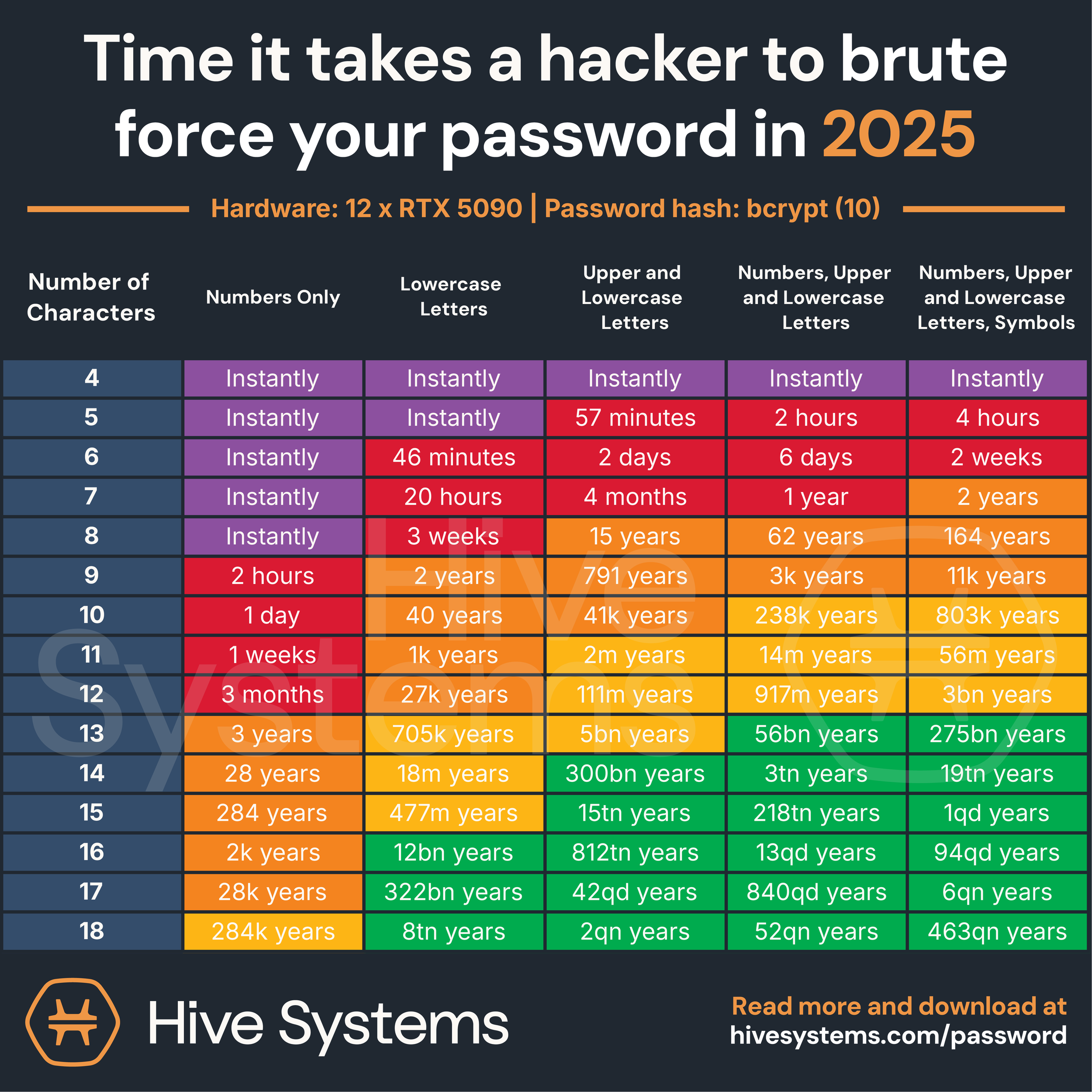

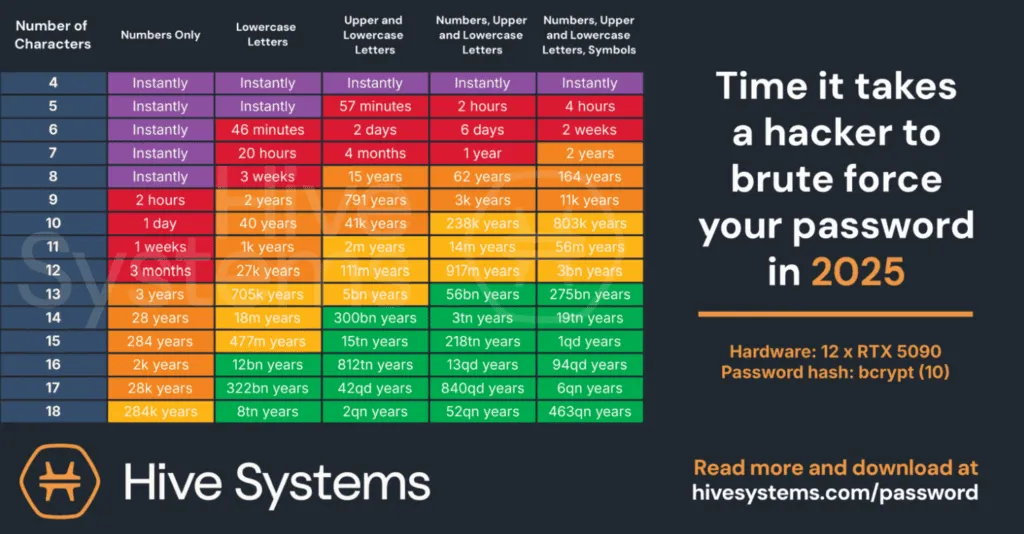

Estimated data shows that increasing password complexity significantly increases crack time, especially when using a combination of character types.

How Password Cracking Actually Works: The Technical Reality

To understand why weak passwords fail, you need to understand how attackers actually crack them. It's not mystical. It's math, and it's brutal.

Brute Force Attacks: The Sledgehammer Method

The simplest cracking method is brute force: trying every possible combination until one works. This sounds incredibly slow, and for short passwords, it is. But modern hardware changes everything.

A single modern GPU can test approximately 100 billion password combinations per second depending on the hashing algorithm used. If a password database uses weak hashing (like MD5, which many legacy systems still do), that speed multiplies by factors of 10 or more.

Let's do the math on a simple eight-character password using only lowercase letters:

At 100 billion guesses per second, a GPU cracks this in roughly 2 seconds.

Now add numbers and uppercase letters to that same eight characters:

This takes about 37 minutes. Progress, but not exactly Fort Knox.

Extend it to 12 characters:

Now we're talking years, not hours. But here's where real attackers laugh at this calculation.

Dictionary Attacks: The Smart Method

Brute force is the nuclear option. Most attackers use something smarter: dictionary attacks.

Instead of testing every possible combination, they start with known words. English dictionaries have roughly 470,000 common words. Tests with the "rockyou" password database from a 2009 breach showed that dictionary words appeared in over 90% of user-created passwords. That means testing 470,000 options instead of 95 quadrillion.

Better yet, attackers combine dictionary words. Concatenating two common words creates a much larger possibility space, but one that's still dramatically smaller than purely random combinations. "Correct horse battery staple" (a now-famous example of good password design) can be cracked in hours if attackers know it comes from words.

But here's the killer: attackers don't start with English dictionaries. They start with password breach databases. When one company gets hacked, the attacker databases grow. They now have millions of real passwords people actually used. When someone tries variations of "bigmac," attackers test them faster because they've already seen similar patterns in previous breaches.

Rainbow Tables and Lookup Attacks

Rainbow tables are pre-computed databases of passwords and their hashes. Instead of computing hashes on the fly, attackers check if the stolen hash matches something in a pre-existing table.

For weak passwords, these tables are incredibly effective. A comprehensive rainbow table for 14-character passwords using uppercase, lowercase, numbers, and symbols would require about 100 terabytes of storage. Expensive, but not impossible for serious attackers. For eight-character passwords? The table fits on a standard hard drive.

This is why password "salting" (adding random data before hashing) became standard. It defeats rainbow tables because each password gets a unique salt, making pre-computed tables useless. But salt only helps if the original password was strong. Salting "bigmac" still leaves "bigmac" relatively easy to crack through targeted dictionary testing.

The Substitution Myth

Here's where the McDonald's campaign directly addresses a widespread misconception. Many people believe that replacing letters with numbers and symbols makes their password secure. "P@ssw0rd" instead of "password."

This belief persists because it worked... in 1997. Modern password crackers have rule sets built in. When they see "password" in a dictionary, they automatically generate variations: "p@ssw0rd," "pa55w0rd," "p@55w0rd," "Password," "PASSWORD," "pASSWORD," and dozens more. Each variation gets tested automatically without slowing the attack meaningfully.

Attackers don't even need to know your specific rule. Rule generators based on patterns found in leaked password databases produce the most common substitutions automatically. When one million passwords used "@" for "a," the cracking tool now knows this is a high-probability substitution and tests it first.

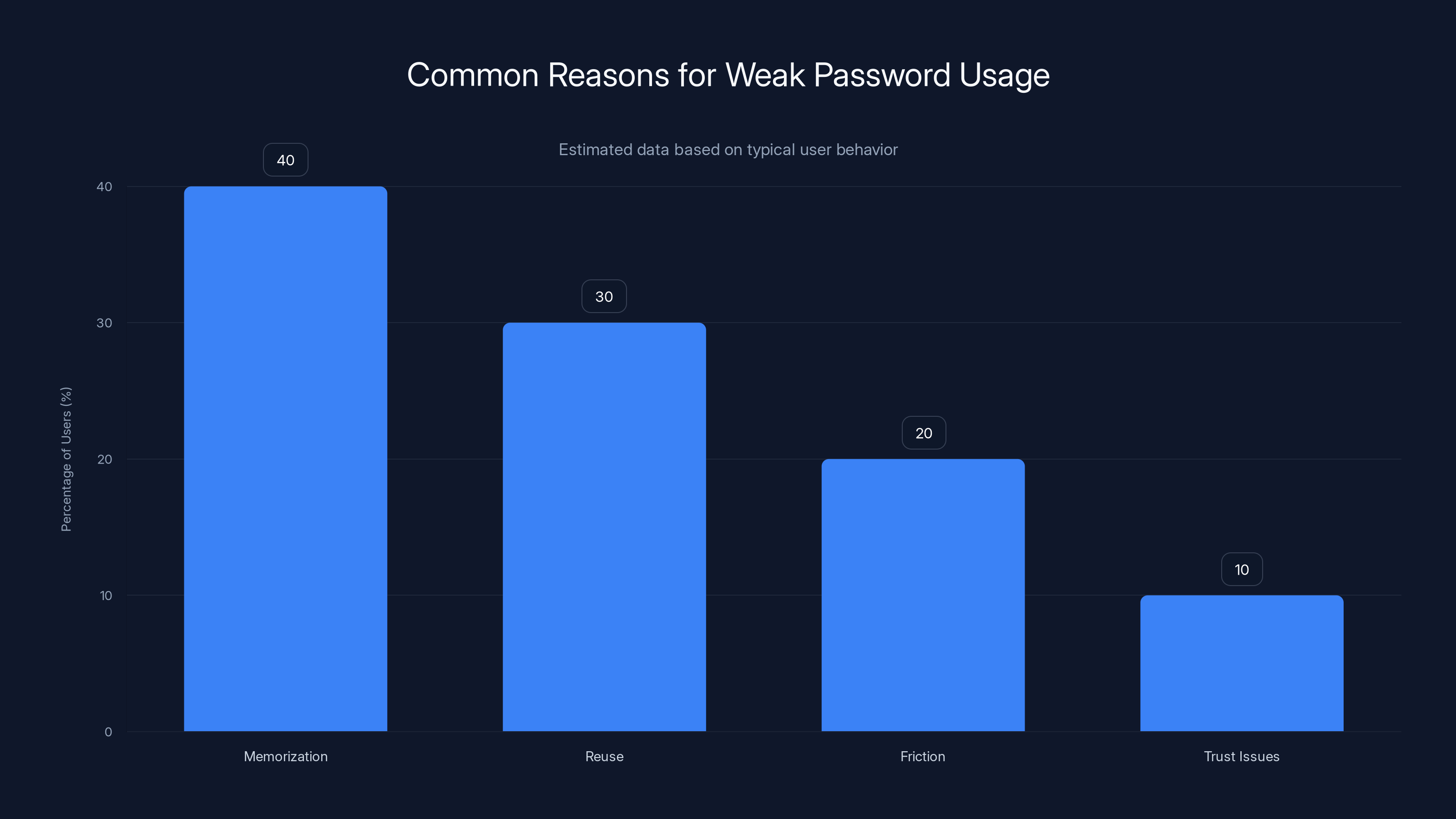

Why We Keep Using Weak Passwords Despite Knowing Better

This is the uncomfortable part. Security experts have been saying the same thing for 20 years. Use strong passwords. Don't reuse them. Use a password manager. Yet millions still choose "bigmac" as their defense.

It's not stupidity. It's human behavior.

The Memorization Trap

Our brains evolved to remember important information. Passwords feel important. So we create something memorable: a name, a pet, a food, a birth year. This feels secure because we can recall it instantly without external tools.

The problem is that memorable equals predictable. Attackers know this. They test birth years first (1980-2010 covers most adult users). They test pet names. They test favorite foods. They've built word lists specifically from things people consider memorable.

A password manager solves this by removing the memorization requirement. But it introduces a new friction point: downloading software, learning an interface, trusting a third party with encrypted credentials. For someone balancing dozens of competing tasks, the friction sometimes wins.

The Reuse Cascade

The second vulnerability pattern is even more dangerous: reuse.

The average internet user now has accounts on 200+ services according to industry surveys. Creating unique, strong passwords for each one is impossible without a password manager. So people do what feels logical: create one good password and use it everywhere, with minor variations on a few accounts.

When any one of those services gets breached, attackers have a username/password combination. They immediately test it on major services: Gmail, Microsoft, Apple, Amazon, LinkedIn, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram. If you used the same password across multiple platforms, one breach compromises your entire digital life.

This is called credential stuffing, and it works with terrifying efficiency. Automated tools test stolen credentials against thousands of login pages simultaneously. If your email uses the same password as your bank account, attackers gain access to both in seconds.

The tragic part is that credential stuffing doesn't require sophisticated hacking. It doesn't require zero-day exploits or social engineering. It just requires someone to have reused a password across platforms. One old breach. Multiple current compromises.

The Complexity Paradox

Organizations compound this by mandating complex passwords. Mix uppercase, lowercase, numbers, symbols. Change every 90 days. Minimum 12 characters. These policies feel secure but create perverse incentives.

When users face impossible demands, they solve it with predictable systems. "Mycompany!2025" for a company account. Add a number for each password change: "Mycompany!2025" becomes "Mycompany!2026" next quarter. Write the password on a sticky note because memory can't handle 47 complex passwords. Reuse the same base across accounts because variation demands exceed human capacity.

Research from Microsoft and university security groups found that complex password policies increased the total security risk compared to enforcing longer passwords with no complexity requirements. Users found workarounds. They wrote passwords down. They reused them. The friction of complex policies made them less secure, not more.

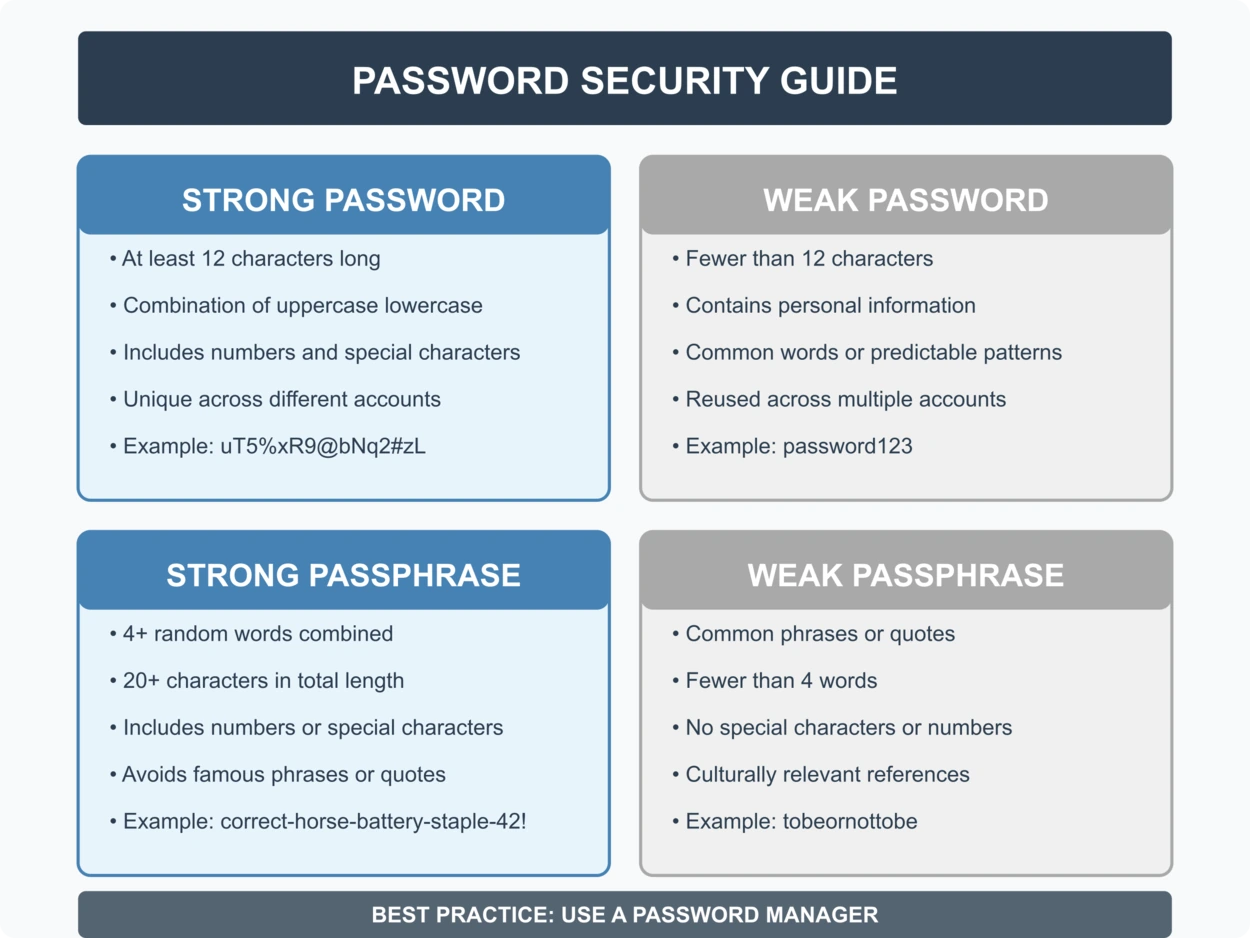

Passphrases offer higher entropy and longer crack times compared to complex passwords, making them a more secure choice. Estimated data for enhanced passphrase.

Real-World Breach Patterns: What Actually Happens When Weak Passwords Fail

Understanding password cracking in theory is one thing. Seeing it in action during actual breaches is something else entirely.

The Anatomy of a Typical Employee Breach

Consider this scenario, which plays out hundreds of times per year at organizations of all sizes:

A company's email system gets breached. The attacker gains access to 50,000 employee credentials. Among them: dozens of employees using passwords like "Welcome123," "Company2024," "Password123," and yes, food-related passwords.

The attacker doesn't sell this list publicly yet. Instead, they test these credentials against other common systems. VPN access. Cloud storage. Project management tools. Admin panels. Within hours, they've identified accounts with valid credentials that still work. Most people reuse passwords across platforms.

For an administrator account using "bigmac123," the attacker now has access to the server infrastructure. They explore what's available. Databases. File shares. Email archives. They install persistent access mechanisms (backdoors) so that even if the company discovers the breach and changes the admin password, the attacker remains inside.

The organization might not notice the breach for weeks or months. During that time, the attacker exfiltrates customer data, intellectual property, or financial information. They might deploy ransomware that encrypts critical systems, forcing the company to choose between paying a ransom or restoring from backups (if backups exist).

A single weak password used by one administrator. That's the entire attack chain. No sophisticated exploit. No zero-day vulnerability. Just password reuse and weak credentials doing exactly what security experts warned they would do.

The Enterprise Admin Lesson

This specific vulnerability is why enterprises now enforce strict admin account rules: admins must use unique, strong passwords stored in credential vaults. Not because enterprises distrust admins, but because admin accounts are the skeleton key. One weak admin password exposes everything.

Yet even with formal policies, enforcement remains a challenge. A privileged account management survey found that 34% of organizations had admins using the same password across multiple systems. Not deliberately. Through habit. Through the same human factors that make "bigmac" appealing.

The Financial Services Nightmare

In financial services, weak passwords become directly measurable disasters.

A bank employee with access to customer accounts uses "birthday1987" (their birth year plus a number) as their password. An attacker compromises this account through a phishing email. They gain access to customer account information, wire transfer systems, and perhaps even trading accounts.

The employee might notice unauthorized access eventually. Or customers might report missing money. By then, wire transfers have cleared to international accounts. The damage is quantified in hundreds of thousands of dollars, plus the regulatory fines that follow a security breach involving weak credentials.

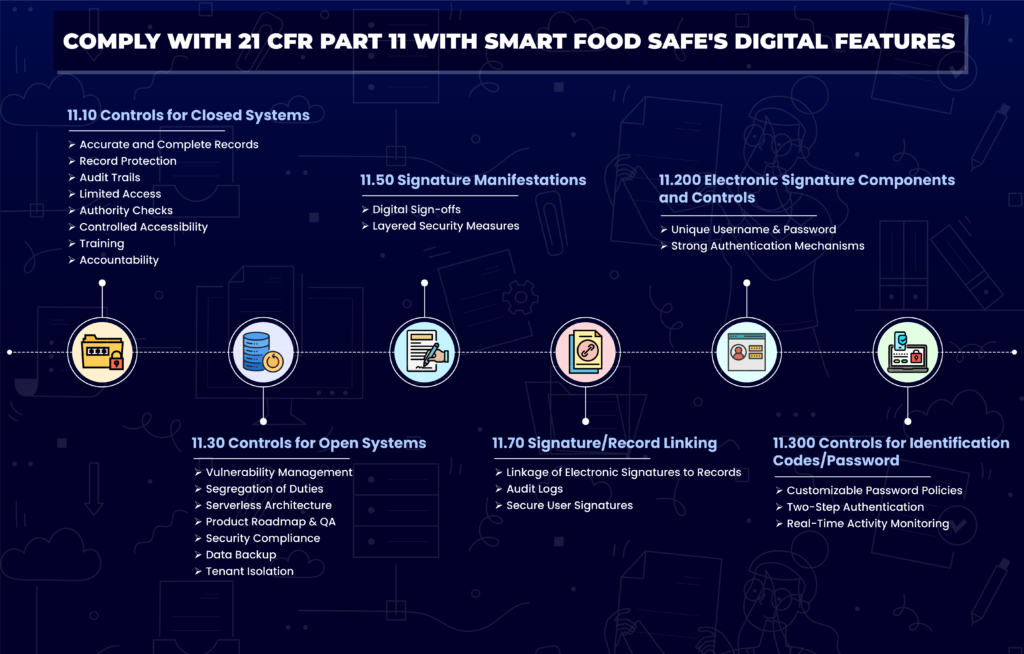

Financial regulations like PCI-DSS and SOX now require password policies specifically because of these scenarios. But requirements are meaningless without proper tools and enforcement.

The Password Manager Revolution: Finally Solving the Problem

For decades, password security involved a fundamental trade-off: security or convenience. You could have one, but not both.

Password managers solved this by making strong, unique passwords convenient.

How Password Managers Work

A password manager is essentially a secure vault. You remember one password (the master password) to unlock the vault. Inside, the system stores your account credentials for hundreds or thousands of sites.

When you visit a website, the password manager (usually as a browser extension) recognizes the login form and offers to fill in your credentials automatically. You don't type the password. The manager does. You don't memorize it. The manager stores it encrypted.

The encryption uses strong algorithms. Your stored passwords remain encrypted even from the company running the password manager. They have the encrypted vault but cannot decrypt it without your master password.

This solves the core problem: you can now use a unique, strong, completely random password for every single site. "7

Most importantly: if one site gets breached, only that one password is compromised. The attacker gains access to your account on that specific service, but nothing more. Your email remains secure. Your bank remains secure. Your social media remains secure.

Enterprise Password Management

For organizations, password managers scale into vault systems. Instead of each employee maintaining their own vault, the organization runs a centralized system. Employees authenticate to the vault and retrieve credentials for systems they're authorized to access.

This provides several advantages:

Centralized Control: Administrators can enforce password policies. Enforce minimum length. Require character complexity. Set rotation schedules. If someone leaves the company, their access to all stored credentials can be revoked instantly.

Audit Trails: Every access to a stored credential gets logged. Who accessed which account and when. This compliance requirement alone justifies the cost for regulated industries.

Rotation Automation: The system can automatically change passwords on connected systems at scheduled intervals. Instead of administrators manually updating 500 system passwords, the vault does it automatically.

Reduced Reuse: Since credentials are managed centrally, there's no incentive to reuse passwords across systems. Each system gets a unique credential.

Breach Containment: If an employee's vault access is compromised, the damage is limited to systems they actually accessed. Compare this to an environment where users memorize and reuse the same password: a single compromise breaks everything.

Major organizations now dedicate significant resources to password vault implementation because the ROI is obvious. Reduced breach costs. Reduced compliance violations. Reduced incident response complexity.

Memorization and reuse are the top reasons users continue using weak passwords, affecting 70% of users. Estimated data.

Multi-Factor Authentication: The Second Line of Defense

Password managers eliminate the weak password problem. But they introduce a new risk: if someone steals your master password, they access everything.

This is where multi-factor authentication (MFA) enters the picture. MFA means proving your identity through multiple methods, not just something you know (your password).

Authentication Factors Explained

Security experts categorize authentication methods into three categories:

Something You Know: A password, PIN, or security question. Easy to use but vulnerable to theft.

Something You Have: A physical device. A smartphone. A hardware security key. A smartcard. Much harder to steal because it requires physical access.

Something You Are: Biometric data. Fingerprint. Face. Iris scan. Theoretically hardest to fake, though spoofing attacks exist.

Multi-factor authentication requires at least two of these three categories.

The most common implementation combines something you know (password) with something you have (smartphone). You enter your password, and the service sends a verification code to your phone. You enter the code to complete authentication.

If an attacker steals your password, they cannot log in without your phone. If someone steals your phone, they cannot log in without your password. This makes compromise dramatically harder.

MFA Vulnerabilities and Improvements

The original MFA implementation, SMS-based codes, had a vulnerability: attackers could redirect your phone number. This is called SIM swapping. An attacker calls your mobile provider, claims they've lost their phone, and requests the number be transferred to a new SIM card in their possession. SMS codes now go to their phone, not yours.

SIM swapping attacks compromised high-profile accounts, including cryptocurrency wallets worth millions. SMS-based MFA provided security against password theft but not against SIM swapping.

Modern MFA uses hardware security keys instead. These are small USB devices that generate cryptographic proofs specific to the website you're logging into. The key doesn't contain any secrets. Instead, it performs calculations that prove possession of the physical device.

Hardware keys cannot be remotely redirected. They cannot be compromised through SIM swapping. They cannot be stolen through phishing because they're not transmitted or stored anywhere. If a site gets breached, the hardware key remains secure.

The trade-off is convenience. Hardware keys cost $20-50 each and require physical carrying. SMS codes, while less secure, are more convenient because everyone carries a phone anyway.

Passphrase Strategy: A Human-Friendly Alternative

Not everyone wants to use a password manager. Some people prefer memorized passwords, even if fewer of them. For these users, passphrases offer a better approach than traditional complex passwords.

Why Passphrases Beat Complex Passwords

The famous "Correct Horse Battery Staple" example illustrated something counterintuitive: a long passphrase is more secure than a short complex password, even though it looks simpler.

"Correct Horse Battery Staple" is 25 characters. It contains mixed case and spaces (sometimes). From a human perspective, it's easy to remember because the words form a mental image.

From a security perspective, it has dramatically more entropy than "P@ssw0rd!"

Entropy measures uncertainty. How many guesses would an attacker need to crack the password with 50% probability?

For "P@ssw0rd!":

- Nine characters, uppercase, lowercase, numbers, and symbols

- Entropy ≈ 52 bits

- Crack time (at 100 billion guesses per second): seconds

For "Correct Horse Battery Staple" (assuming an attacker knows it's four common English words):

- Dictionary contains roughly 470,000 common words

- Number of ways to choose 4 words from 470,000:

- Entropy ≈ 63 bits

- Crack time: hours to days

Add an uncommon word or punctuation, and entropy climbs to 80+ bits. This requires centuries of cracking even at modern speeds.

Building Secure Passphrases

The key is randomness. "Correct Horse Battery Staple" works as an example because it's random word combinations, not a memorable phrase. "I love my dog Bella and her puppies" is not random; it's a memorable phrase using predictable vocabulary. Attackers will test sentences before random word combinations.

To create a strong passphrase:

- Choose 5-6 random words from a dictionary

- Concatenate them without predictable patterns

- Add a number or symbol for good measure

- Do not use famous phrases, song lyrics, or movie quotes (attackers have these databases)

Example secure passphrases:

- "Turquoise Unicorn Breadcrumb Wednesday Ninja 42"

- "Volcano Spoon Octopus Glitter! Tuesday Pickle"

- "Satellite Chocolate Palace Thornbush@1997 Pyramid"

These passphrases are:

- Long (40+ characters)

- Random (no dictionary patterns)

- Memorable (you can recall the word list)

- Secure (entropy too high for practical cracking)

The trade-off is that you must remember multiple passphrases if you use this approach without a password manager. Most people cap out around 3-5 memorable passphrases before resorting to reuse.

Food-related terms like 'BigMac' and 'Pizza' appear frequently in breached password databases, with 'BigMac' alone found in over 110,000 accounts. Estimated data highlights the scale of the issue.

Organization-Wide Password Security: Policy and Enforcement

Individual password management is important, but organizations face larger challenges. How do you enforce password security across hundreds or thousands of employees?

The Obsolescence of 90-Day Password Changes

For decades, organizations mandated password changes every 90 days. The thinking was simple: even if someone got compromised, frequent changes limit the exposure window.

Research from Microsoft and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) eventually proved this counterproductive. Here's why:

Frequent forced changes encourage predictable patterns. "Mycompany2024" becomes "Mycompany2025" when the quarter changes. Users write down passwords rather than memorizing new ones. Employees reuse passwords across systems because memorizing new complex passwords is impossible under 90-day rotations.

Moreover, if a password is compromised today, it doesn't matter if you change it in 90 days. The attacker already has access. If it's not compromised, changing it provides no benefit.

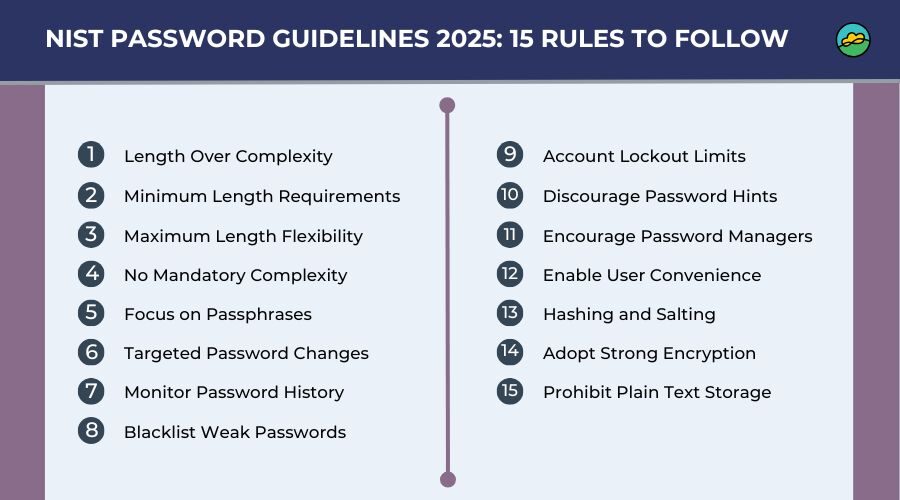

NIST's revised guidance now recommends against mandatory rotation for strong passwords with no evidence of compromise. Instead, organizations should rotate passwords only when breach indicators appear.

This shift reduces password fatigue while improving actual security. Employees create stronger passwords when they're not changed constantly. They're less likely to write them down. They're more likely to use unique passwords because the burden decreases.

The Shift to Passwordless Authentication

Where possible, forward-thinking organizations are moving beyond passwords entirely.

Passwordless authentication uses biometrics (fingerprint, face) combined with device ownership. You unlock your phone with your fingerprint, and the phone proves to applications that you're authenticated. No password is ever typed or transmitted.

Microsoft has been pushing this shift aggressively. Their Windows Hello system uses facial recognition or fingerprint authentication tied to your device. Azure Active Directory authentication supports passwordless sign-in through the Microsoft Authenticator app.

The advantages over traditional passwords:

- No passwords to crack or phish

- No credentials to steal from databases

- Faster authentication (biometrics are quick)

- Better audit trails (which device authenticated, exact time)

The disadvantages:

- Requires updated infrastructure

- Biometric authentication can be spoofed (though this is difficult)

- Less flexible for users who cannot provide biometrics (disability, injury)

Threat Intelligence Integration

Modern organizations integrate threat intelligence into password systems. If your password appears in a breach database, the system alerts you immediately.

Services like "Have I Been Pwned" track compromised credentials from hundreds of major breaches. Organizations subscribe to this data and check their users' passwords against it. If an employee's password appears in any breach, the system forces a password change immediately, even if that breach was at a different company.

This catches a specific vulnerability: employees reusing passwords from old breaches. If you used a password at Company A five years ago, and Company A got breached last year, your password now sits in an attacker database. If you still use it at Company B (your current employer), you're vulnerable.

Automated threat intelligence checks prevent this by detecting the reused compromised password before attackers exploit it.

The Psychology of Password Creation

Why do people use "bigmac" as a password in the first place? Understanding the psychology helps organizations design better security policies.

Cognitive Load and Decision Fatigue

Password creation feels trivial, but it's actually a complex decision. The user must:

- Understand the security requirements

- Create something memorable

- Make it complex enough to be secure

- Ensure it's not reused

- Decide how to store it

For the average person managing 200+ accounts, this decision fatigue becomes overwhelming. Creating a unique, strong password for each account requires constant decision-making. The easier option is memorization-based creation: pick something you already remember (like "bigmac") and use that everywhere.

This isn't laziness. It's rational resource allocation. The person consciously decides that the mental effort of password management exceeds the perceived risk of weak passwords. They've likely never experienced a breach caused by weak credentials, so the abstract risk feels lower than the concrete effort required to manage strong passwords.

Trust in Obscurity

People often believe their passwords are secure because they're unique to them. "Nobody else will think to use my dog's name and my birth year." This is the trust-in-obscurity fallacy.

Attackers specifically test these patterns because they know humans think this way. Passwords based on personal information (pets, birthdays, favorite foods, sports teams) appear in attack dictionaries built from psychology research, not random guessing.

The illusion of uniqueness provides false confidence. The password feels secure because the person created it themselves, even though it follows predictable human patterns.

Competing Priorities

For most employees, password security ranks far below their primary job responsibilities. A salesperson's priority is closing deals, not managing credentials. A developer's priority is writing code. An administrator's priority is keeping systems running.

Password management becomes a friction point. It gets in the way. When friction becomes too high, people find workarounds: sticky notes, password reuse, simple memorable passwords.

Systems that reduce friction (password managers, single sign-on, passwordless authentication) see better adoption precisely because they align security with convenience rather than competing with it.

Estimated data shows that passwordless authentication is the most effective, followed by policies with no mandatory rotation, while 90-day rotations are less effective.

Industry Standards and Compliance Requirements

Organizations in regulated industries can't treat password security as optional. Compliance requirements mandate specific password policies.

PCI-DSS for Payment Systems

The Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard requires:

- Minimum 8-character passwords

- Passwords containing numbers, letters, and symbols

- Password changes at least every 90 days

- Not reusing the last four passwords

- Account lockout after six failed login attempts

- Password changed on first login

These requirements are outdated relative to current security research, but they represent the baseline for any organization processing credit card payments. Failure to meet PCI-DSS requirements results in fines, loss of payment processing ability, and potential liability for fraud.

HIPAA for Healthcare

Healthcare organizations must comply with HIPAA, which requires:

- Unique user IDs for all accounts

- Emergency access procedures

- Periodic password changes

- Automatic logoff after inactivity

- Encryption of passwords during transmission and storage

Healthcare breaches expose medical records, which contain not just health information but often social security numbers, addresses, and payment information. The penalties for HIPAA violations reach into millions of dollars per breach.

SOX for Financial Institutions

The Sarbanes-Oxley Act requires financial institutions to maintain strong internal controls, including access controls and password management. The standard is vague by design, but enforcement through regulatory audits is strict.

GDPR for European Privacy

The General Data Protection Regulation doesn't mandate specific password policies but requires organizations to implement "appropriate technical measures" to protect personal data. Strong password practices and multi-factor authentication fall under this requirement.

Organizations violating GDPR through weak password security leading to data breaches face fines up to 4% of global annual revenue. For a large company, this is billions of dollars.

Password Security in Cloud Services

Cloud providers (AWS, Azure, Google Cloud) handle authentication differently because they operate at scale and need to manage enterprise security.

Identity and Access Management (IAM)

Cloud providers implement IAM systems where passwords are just one part of authentication. AWS Identity and Access Management, Azure AD, and Google Cloud IAM all use:

- Multi-factor authentication

- Temporary credentials (expiring after hours)

- Federated identity (single sign-on)

- Passwordless authentication

- Detailed audit logs

A user authenticates once, and the cloud provider issues a temporary token. The user's application uses this token rather than repeatedly entering credentials. When the token expires, the user must reauthenticate.

This architecture prevents credentials from being stored in application code or configuration files. Even if a developer accidentally commits credentials to GitHub, the tokens are temporary and automatically revoke after a set period.

Secrets Management

Cloud services often need to authenticate to other services (a database server, an external API). Traditional approaches required hardcoding credentials into application code.

Secrets management systems like AWS Secrets Manager, Azure Key Vault, and HashiCorp Vault store these credentials separately from code. The application requests a secret at runtime, authenticates through IAM, and receives a temporary credential. The application uses the credential and discards it.

If a developer leaves, their access is revoked, but the hardcoded credentials never existed. If source code is stolen, the credentials aren't in the code.

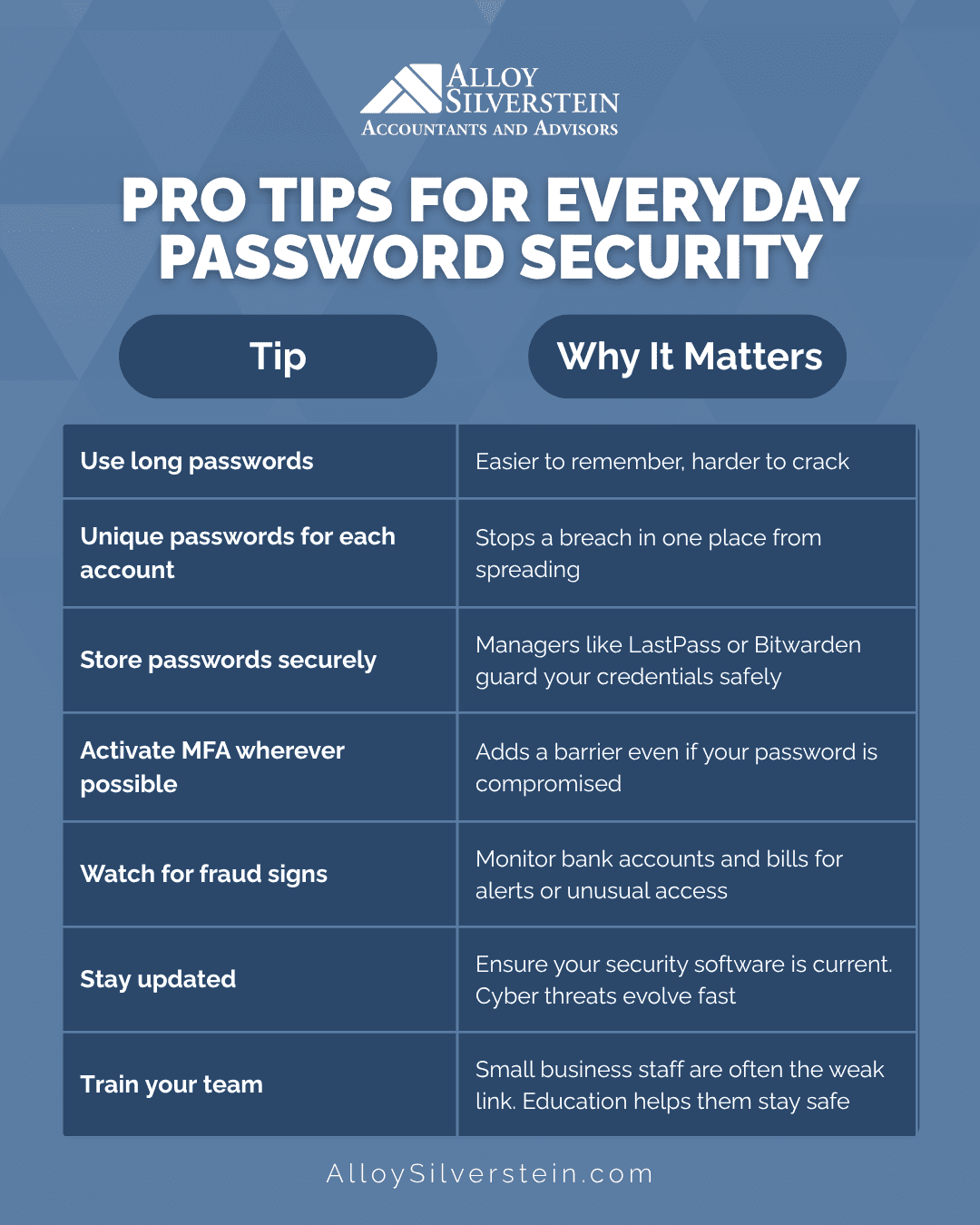

What You Should Do Right Now: Practical Implementation

Enough theory. Here are specific steps to improve your password security today.

For Individual Users

Step 1: Audit your passwords Visit "Have I Been Pwned" and check if your email appears in any breach database. If it does, your passwords from that service are compromised. Change them immediately.

Step 2: Identify critical accounts List your most important accounts: email, banking, investment accounts, health records, social media. These are your priority.

Step 3: Enable multi-factor authentication For your critical accounts, enable MFA. Use hardware keys if you're concerned about sophisticated attacks. Use authenticator apps if you want convenience. Use SMS codes as a last resort.

Step 4: Choose a password manager Select one (Bitwarden, 1Password, LastPass, Dashlane, whatever fits your needs) and migrate your passwords into it. This is a one-time project that takes a few hours and pays dividends for years.

Step 5: Create unique, strong passwords For all accounts, let your password manager generate 16+ character random passwords. You never memorize them. The manager stores them encrypted.

Step 6: Never reuse passwords Ever. Even if a password is complex, reusing it across services means a single breach compromises multiple accounts.

For Organizations

Step 1: Inventory your current password practices Audit what password policies exist, which systems enforce them, and where enforcement gaps exist.

Step 2: Deploy a password manager or vault Choose an enterprise solution (Microsoft Entra ID, Okta, CyberArk, HashiCorp Vault) and deploy it. Start with critical accounts (admin access, service accounts) before expanding to all employees.

Step 3: Implement multi-factor authentication Require MFA for all remote access and all admin accounts immediately. Roll out to other accounts over time.

Step 4: Integrate threat intelligence Subscribe to breach notification services and check employee passwords against compromised credential databases. Force password changes when matches are found.

Step 5: Eliminate password rotation requirements Remove the 90-day forced password change policy. Replace it with event-driven changes (when breach indicators appear) and passwordless authentication where possible.

Step 6: Provide security awareness training Teach employees why passwords matter and how to use the tools you've provided. Make security training specific and actionable, not generic.

The Future of Authentication

Where is password security heading? Several trends are emerging.

Biometric Authentication at Scale

Biometric authentication (fingerprint, face) is becoming standard on consumer devices. As these systems improve, they'll likely replace passwords for most consumer applications. A website will verify your identity through your device's biometric system rather than asking you to type anything.

The security improvement is substantial: biometric authentication is specific to you and your device. It can't be phished, reset remotely, or stolen through breaches. It will take decades to fully replace passwords, but the trend is clear.

Passkeys and WebAuthn

A passkey is a new standard that uses cryptography instead of passwords. You verify your identity through your device's biometric or PIN, and the device generates a cryptographic proof. The website verifies the proof.

Unlike passwords, passkeys are impossible to phish. You can't accidentally reveal a passkey to a fake website because the key is never transmitted. The proof is specific to the legitimate domain. A fake website gets a different proof that the browser rejects.

Major platforms (Apple, Google, Microsoft) are implementing passkeys. They're becoming the standard authentication method for consumer applications. They'll eventually move to enterprise systems.

Decentralized Identity

Blockchain-based identity systems are being developed to let individuals control their credentials without relying on service providers. Instead of asking your email provider for authentication, you authenticate through a decentralized identity system you control.

This is still experimental, but it represents a philosophical shift: moving from passwords stored by service providers to cryptographic credentials you personally control.

Why McDonald's Campaign Matters More Than You Think

Circling back to the original campaign: why did McDonald's invest in this?

McDonald's operates globally and processes millions of payment transactions daily. Their systems have login pages. Their employees have accounts. Their partner restaurants access their ordering systems. If someone uses "bigmac" as their password and that account gets compromised, attackers might access systems that handle financial transactions or payment data.

Moreover, McDonald's customers trust them with personal information. If a customer breach exposes credit card data, part of the blame falls on weak internal password security. The company has financial incentive to ensure their own employees and systems aren't compromised through password weaknesses.

The campaign is partially self-interest: protect their systems by encouraging customers (who might be employees or partners) to use better passwords. But it's also recognition that weak passwords are a collective problem. When millions of people use "bigmac" as a password, it normalizes weak credential practices across the internet.

When one person uses "bigmac" as their password, it affects only them. When millions do, it signals to the broader culture that weak passwords are acceptable. It makes password education harder. It makes security professionals' jobs harder.

By publicly mocking food-based passwords, McDonald's is using their platform to counter that normalization. The humor is disarming. It doesn't make you feel stupid for using a weak password. It makes you feel like you're in on the joke.

That's actually effective security communication. It acknowledges human behavior without shaming it. It provides a laugh while delivering the message. And crucially, it plants doubt: "Maybe I should check my passwords."

Making Password Security Stick: Long-Term Behavior Change

Knowing you should use strong passwords and actually doing it are different things. Here's how to make password security a permanent habit.

Remove Friction Points

The single biggest factor in password security adoption is friction. If using strong passwords is harder than using weak ones, people choose weak passwords.

Password managers eliminate this friction. They auto-fill credentials faster than you can type them. They generate passwords so you don't have to remember anything. The security behavior becomes the path of least resistance.

Make It Social

Behavior change is easier when it's social. If your workplace implements password managers and MFA, others adopt them faster. If your friends use hardware security keys, you become curious.

McDonald's understood this. The campaign went viral because it was funny and because it created a social conversation about passwords. People shared the posters. They joked about the messaging. The humor made the security advice shareable in a way traditional security warnings never are.

Focus on the Outcome, Not the Process

Don't tell people to use 15-character random passwords. Tell them that password managers let you use unique passwords for every account with zero memorization required. The outcome (security without effort) is appealing. The process (using a password manager) is the implementation detail.

Personalize the Risk

Abstract risk ("breaches happen to lots of people") doesn't motivate behavior change. Concrete risk does.

If an employee has experienced a credential theft or account compromise, password security becomes real. They've felt the consequences. They change their behavior.

For employees who haven't experienced compromise, the risk feels theoretical. Behavior change is harder. Organizations can bridge this by:

- Sharing incidents from other companies in their industry

- Running simulated phishing campaigns to show how credential theft works

- Providing concrete examples of what compromised credentials can access

The Role of AI and Machine Learning in Password Security

Artificial intelligence is starting to play a role in password security, both for protection and for attacks.

AI-Enhanced Password Cracking

Machine learning models can learn patterns from leaked password databases and generate more intelligent password guesses. Instead of testing every possible combination or every dictionary word, AI models learn which characters are likely to appear in certain positions, what common patterns users follow, and what substitutions they prefer.

This makes password cracking faster. Traditional dictionary attacks might test a million variations. AI-enhanced attacks can prioritize the most probable variations first.

The security implication is clear: weak passwords become crackable even faster. But strong, random passwords remain uncrackable regardless of how smart the cracking algorithm becomes.

AI for Security Monitoring

On the defensive side, AI can detect suspicious login patterns. If your account usually logs in from your office between 9 AM and 5 PM, but suddenly someone logs in from a different country at 3 AM, AI systems flag this as suspicious.

Some systems require additional authentication (MFA) for unusual login patterns. This adds a security layer: even if an attacker steals your password, they need to complete an additional authentication challenge that you're alerted to.

More advanced systems use behavioral biometrics: how fast you type, the rhythm of your keystrokes, how you move your mouse. These characteristics are hard to fake. If someone else is using your account, their typing patterns won't match yours.

Final Thoughts: Taking Control of Your Digital Security

Password security might seem like a boring technical topic, but it's foundational to your digital life. Every account you have, every service you trust with personal information, every financial transaction relies on the strength of your credentials.

The McDonald's campaign isn't just a funny marketing stunt. It's a reminder that weak passwords remain surprisingly common despite decades of security warnings. It's evidence that the problem hasn't been solved through awareness alone.

The good news: solving the password problem is actually straightforward. Use a password manager. Enable multi-factor authentication. Stop reusing passwords. These three practices eliminate the vast majority of credential-based vulnerabilities.

The challenge is making these practices habitual. It requires initial effort. It requires adopting new tools. It requires changing how you think about passwords.

But once you've made the switch, the daily experience improves. You authenticate faster through biometric methods or hardware keys. You never have to remember passwords. You never stress about breached accounts because you used a unique password.

This is where the security industry is heading: authentication that's both more secure and more convenient than passwords. The transition from passwords to passkeys and passwordless authentication is happening right now.

Your job is to not get left behind. Start with the practical steps outlined in this article. Audit your passwords. Deploy a password manager. Enable MFA. Build the habit.

Don't be the person whose account is compromised because they used "bigmac" as their password. Be the person who laughs at the McDonald's campaign and knows they're already protected.

FAQ

What is a password manager and how does it work?

A password manager is an encrypted digital vault that stores your account credentials. You create one master password to unlock the vault, and the manager stores all your other passwords encrypted inside. When you visit a website, the password manager recognizes the login form and auto-fills your username and password, eliminating the need to remember individual credentials. The encryption uses strong algorithms, so even the password manager company cannot decrypt your stored passwords without your master password.

How strong does a password need to be to be secure?

Modern security guidance recommends passwords of at least 12-16 characters, preferably 16 or longer. For memorized passwords, a long passphrase of 5-6 random words (like "Turquoise Unicorn Breadcrumb Wednesday") provides excellent security. For generated passwords, completely random 16+ character strings combining uppercase, lowercase, numbers, and symbols are effectively uncrackable with current technology. The key is length and randomness, not complexity markers like special characters.

Why is password reuse dangerous?

Password reuse means that if any one service you use gets breached, attackers gain access to your account on every service where you used that password. This is called credential stuffing, and automated tools test stolen credentials against thousands of websites simultaneously. A single breach can compromise your email, banking, social media, and work accounts if you reused the same password across them.

What is multi-factor authentication and why do I need it?

Multi-factor authentication (MFA) requires two or more authentication methods to verify your identity. Typically, you enter your password (something you know) and then provide a code from your phone or hardware key (something you have). If someone steals your password, they still cannot log in without access to your second factor. MFA is particularly important for critical accounts like email and banking because it prevents password theft from leading to account compromise.

How do I know if my password has been compromised in a breach?

You can check if your passwords appear in known breaches by visiting haveibeenpwned.com and entering your email address. The website searches compromised password databases and tells you which breaches exposed your account. If your password was compromised in any breach, even at a service you no longer use, you should change it immediately because attackers have it in their databases and may test it on other services where you reused it.

What should I do if I discover I've been using weak passwords across multiple accounts?

Immediately change your passwords on critical accounts (email, banking, health records) to strong, unique passwords. For your email account specifically, change it first because email is the keys to your other accounts. Then either enable password manager and change all remaining passwords gradually to unique strong passwords, or at minimum change passwords on any accounts where you reused the same weak password. Enable multi-factor authentication on all critical accounts. Set a calendar reminder to revisit less-critical accounts over the next month and update them as well.

Can I safely use the same password if I add different numbers to the end?

No. Automated password cracking tools already account for this pattern. When attackers have a password like "password123" from one breach, they automatically test variations like "password124," "password125," etc. Adding numbers to the end of a password doesn't provide meaningful additional security. You need completely different, random passwords for each account.

What's the difference between a password manager and a password vault?

A password manager typically refers to consumer products that store passwords locally or in a cloud service you control (like Bitwarden or 1Password). A password vault usually refers to enterprise systems that organizations deploy to manage credentials across their company (like CyberArk or HashiCorp Vault). Functionally, they're similar: encrypted storage of credentials with access controls and audit logs. The difference is scale and deployment model.

Is it safe to use password managers if they get hacked?

Yes, because password managers use encryption that keeps your passwords safe even if the company is breached. Even if attackers steal the encrypted vault, they cannot decrypt it without your master password. Your password manager company never has access to your unencrypted passwords. This is different from a traditional website breach where the company stores passwords (even hashed ones). With a good password manager, a breach of the company's systems doesn't compromise your passwords.

Should I write down my master password somewhere safe?

Writes down your master password is a security risk, but some security experts argue that losing access to your master password is also a risk (you lose access to all stored passwords). A reasonable compromise is to store your master password in a secure location accessed only by you: a safety deposit box, a safe at home, or perhaps given to a trusted family member in a sealed envelope only to be opened if you die or become incapacitated. Never store your master password on your computer or phone.

Key Takeaways

- Food-related passwords like 'bigmac' appeared in 110,000+ breached accounts, proving weak credentials remain dangerously common

- Character substitutions ('P@ssw0rd' vs 'password') provide minimal security because modern cracking tools automatically test variations

- Password length matters exponentially more than complexity: 16 random characters beats 12-character 'complex' passwords by orders of magnitude

- Password reuse is the primary vulnerability exploited in credential-based attacks; one breach compromises all reused accounts through credential stuffing

- Password managers solve the impossible trade-off between security and convenience, enabling unique strong passwords for every account without memorization

Related Articles

- 8.7 Billion Records Exposed: Inside the Massive Chinese Data Breach [2025]

- Harvard & UPenn Data Breaches: Inside ShinyHunters' Attack [2025]

- Infostealer Malware Now Targets Mac as Threats Expand [2025]

- Minecraft Server Security Guide: Keep Your Server Safe [2025]

- OpenClaw AI Security Risks: How Malicious Extensions Threaten Users [2025]

- Microsoft's Security Leadership Shift: What Gallot's Return Means [2025]