When Politics Overshadows Science in the Courtroom

Something unsettling happened in early 2025, and most people didn't notice. A document that's been helping judges navigate complex scientific cases for decades got quietly gutted. Not because the science was wrong. Not because new evidence contradicted it. But because a group of Republican state attorneys complained about it.

The Reference Manual on Scientific Evidence, published by the Federal Judicial Center, is supposed to be the judiciary's north star when cases get scientifically complicated. Judges lean on it when they're deciding patent disputes, environmental lawsuits, medical malpractice claims, anything involving expert witnesses and technical complexity. It's nearly 2,000 pages of guidance written by actual scientists and legal experts.

Then came the climate chapter. Written by researchers from Columbia University, it summarized what science has known for years: humans are driving climate change. That claim, backed by the overwhelming consensus of peer-reviewed research, apparently crossed a line for some state attorneys general.

This isn't just a footnote in the culture wars. It's a moment that reveals something deeper about how science, law, and politics are colliding in ways that could reshape the American legal system. And it raises uncomfortable questions about what happens when courts stop listening to experts.

Understanding the Reference Manual on Scientific Evidence

Before we talk about what was taken out, it helps to understand why this document matters so much. Courts deal with science constantly. A pharmaceutical company sues another over patent claims. The FDA disputes health claims on a supplement bottle. Someone gets injured and wants damages from a manufacturer. In every case, judges have to figure out what's real and what's junk science.

That's harder than it sounds. A judge isn't trained as a physicist or biologist. They went to law school. They know courtroom procedure, contract law, maybe constitutional history. But when an expert witness starts talking about molecular biology or climate modeling, the judge is essentially at the mercy of whoever's presenting more convincing testimony.

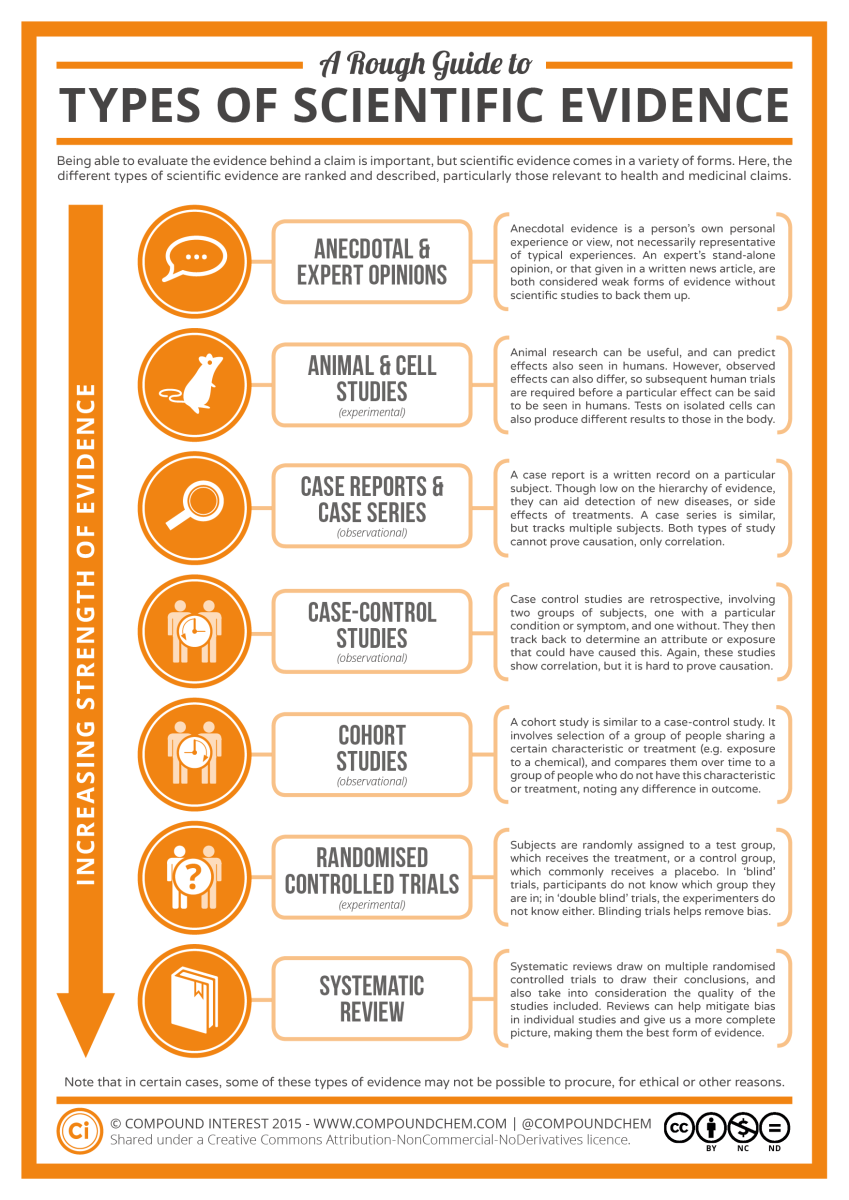

The Reference Manual tries to fix this problem. It's a guide, not a rulebook. It helps judges understand what constitutes legitimate scientific evidence versus what's been debunked or never proven. It explains how peer review works, what statistical significance actually means, and when expert testimony should be trusted.

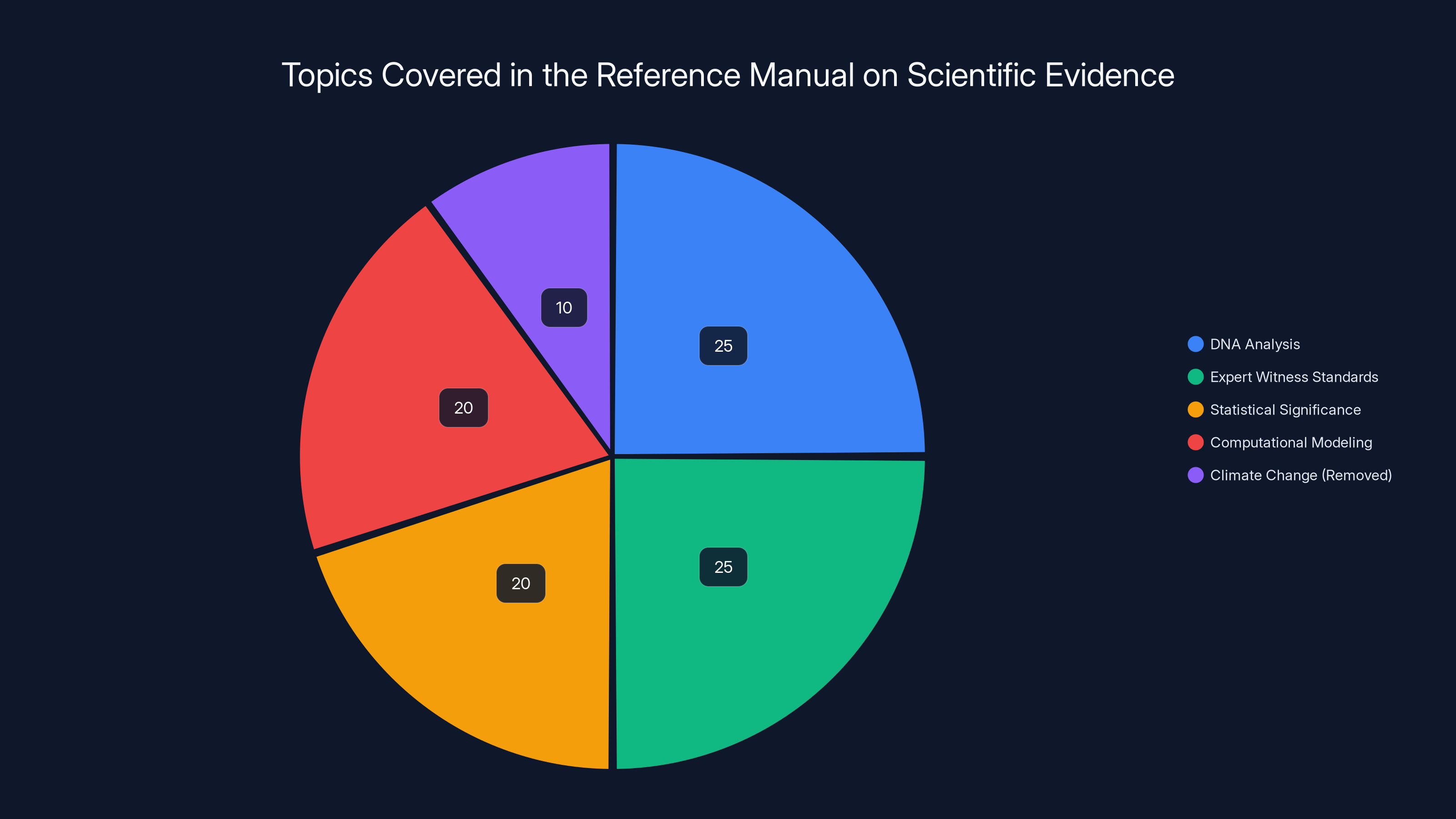

First published in 1994, the manual gets updated periodically as science advances. It's not a partisan document. It covers DNA analysis, expert witness standards, computational modeling, and dozens of other topics. The goal is straightforward: give judges the tools to recognize solid science from pseudoscience.

The manual was written by scientists and legal experts who spent time actually researching their topics. For the climate chapter specifically, Columbia University researchers reviewed the peer-reviewed literature, consulted with climate scientists, and synthesized what we know about anthropogenic climate change. The conclusion they reached wasn't controversial in scientific circles—it's mainstream climate science.

But in political circles? That's a different story.

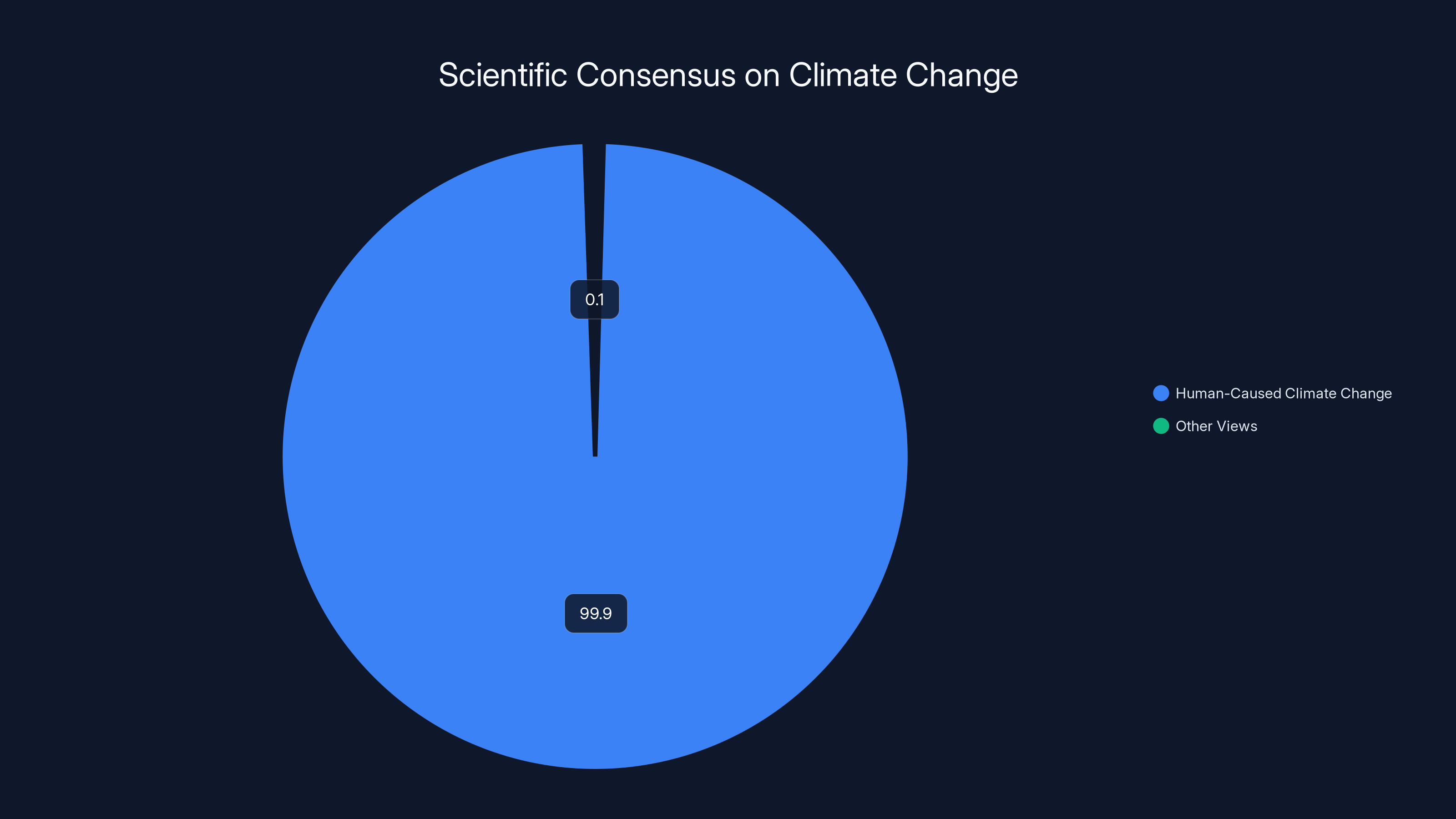

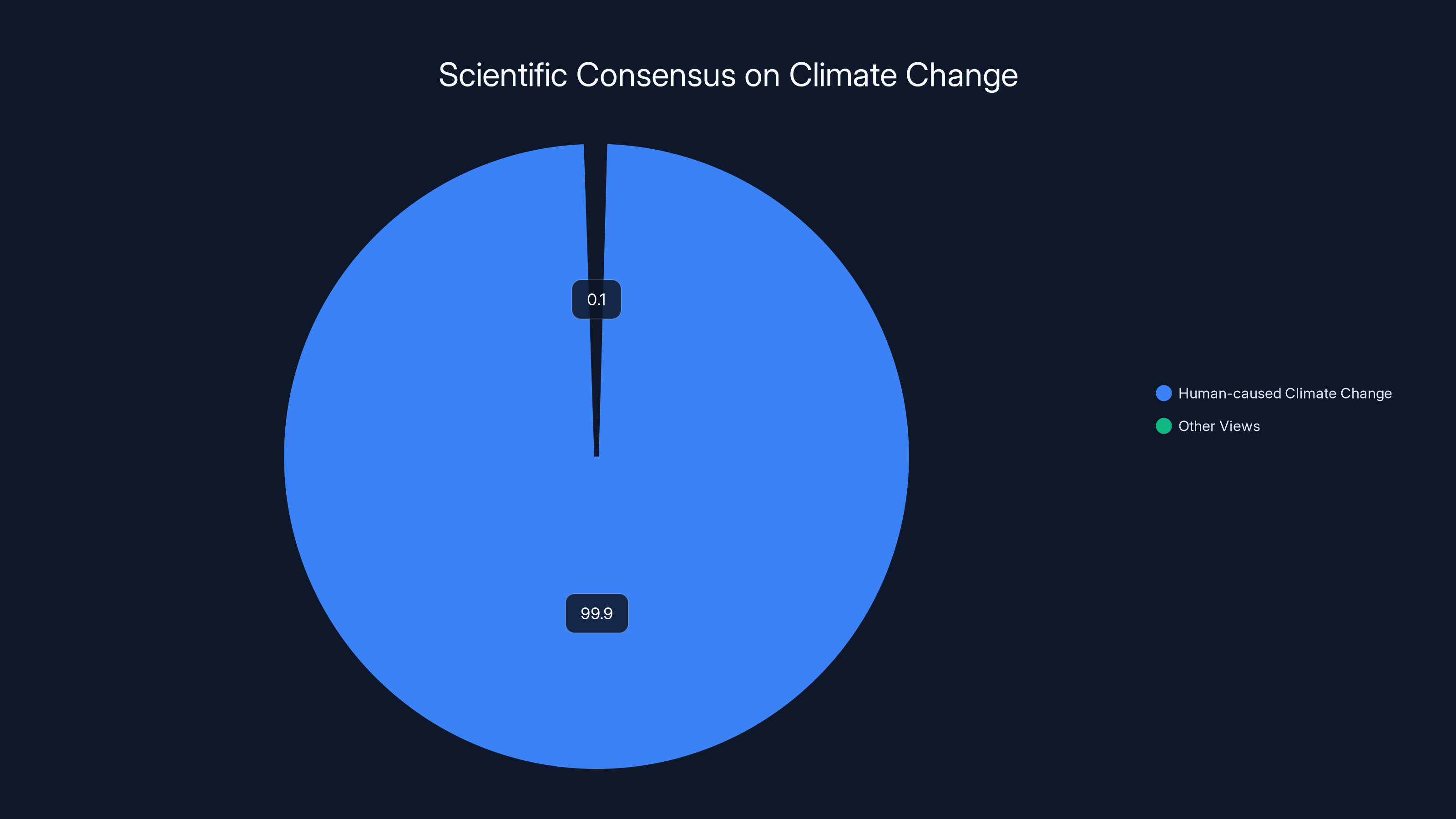

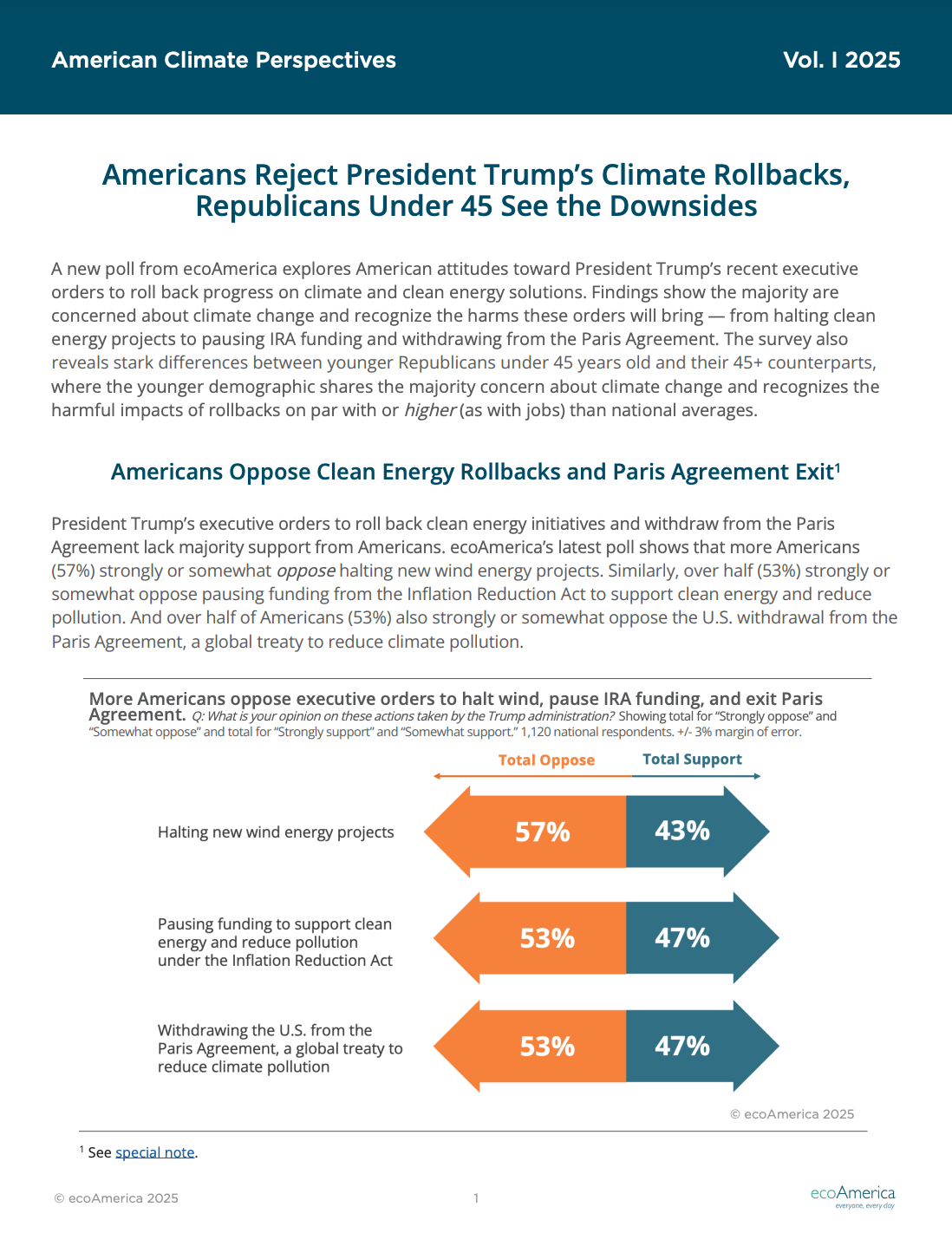

Over 99.9% of peer-reviewed scientific papers agree that climate change is real and human-caused, highlighting a near-universal consensus among experts.

The Letter That Changed Everything

In February 2025, judges across the United States received a revised version of the Reference Manual on Scientific Evidence. The climate chapter was gone. Completely removed. Supreme Court Justice Elena Kagan's introduction still referenced it, creating an odd ghost reference to a section that no longer existed.

The reason for this deletion came down to a letter. A group of Republican state attorneys general wrote to the Federal Judicial Center to lodge a formal complaint about the climate chapter. Their complaint focused on specific language that acknowledged climate change as human-caused and referenced the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change as an authoritative source.

Think about that for a moment. A legal document that synthesizes peer-reviewed scientific consensus got removed because politicians didn't like one of its conclusions. The attorneys general didn't argue the science was wrong. They didn't present contradictory evidence. They essentially said, "We don't like that your document represents the mainstream scientific view, so get rid of it."

Their letter specifically objected to passages suggesting that climate change is driven by human activity. They also took issue with the manual referring to the IPCC as an authoritative body. According to their reasoning, describing mainstream science as "authoritative" somehow violated principles of judicial independence and impartiality.

Here's what's wild about that complaint: the 2,000-page manual declares preferred views on numerous scientific subjects. It discusses DNA analysis, expert witness standards, statistical significance, and computational modeling. Judges consult it to understand what's legitimate science across dozens of fields. But the state attorneys general didn't complain about any of that. Just the climate part.

The attorneys general didn't ask for revisions. They didn't request the chapter be reframed. According to reporting by Ars Technica, they demanded the entire chapter be removed. And the Federal Judicial Center capitulated. No chapter, no alternative guidance, no replacement text. Just deletion.

What the Science Actually Says

To understand why this matters, you need to know what the scientific consensus actually is. And it's not subtle or contested among people who actually study climate.

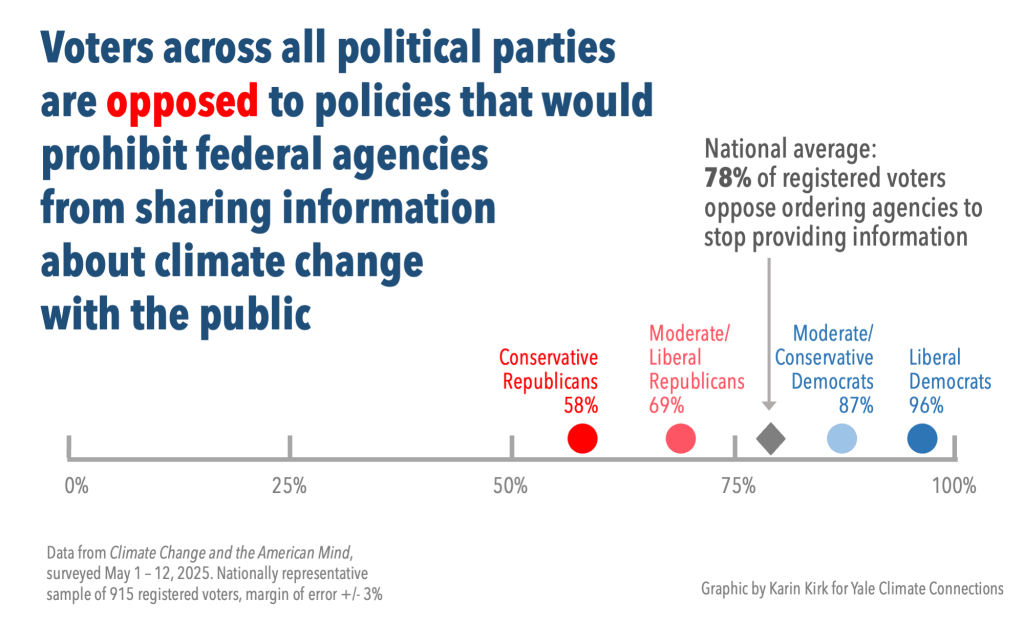

More than 99.9 percent of peer-reviewed scientific papers published on climate change conclude that climate change is real and caused by humans. That's not a political statement. That's a statistical fact about what the scientific literature says. If you surveyed geophysicists, climatologists, and atmospheric scientists, the agreement would be even higher.

The IPCC, which the state attorneys general complained about, represents the work of thousands of scientists from around the world. When they publish their assessment reports every few years, they're synthesizing decades of research into a comprehensive picture of what we know about climate. These aren't fringe scientists or activists. They're professors, researchers, and experts from dozens of countries, many of them politically conservative, working from the same data.

The Columbia University researchers who wrote the climate chapter for the Reference Manual were simply describing this scientific consensus. They weren't inventing anything. They weren't being partisan. They were distilling what the broader scientific community has concluded.

Now, you can disagree with climate science. People do. But a federal document designed to help judges understand scientific evidence isn't the place for that disagreement to override the overwhelming consensus. The purpose of the Reference Manual isn't to settle political debates. It's to help judges recognize legitimate science from illegitimate science.

When a document meant to guide judges in distinguishing good science from bad science gets edited specifically because it presents the scientific consensus on a topic, you've crossed a line. You're no longer having a conversation about what the evidence says. You're having a conversation about suppressing evidence because you don't like the conclusion.

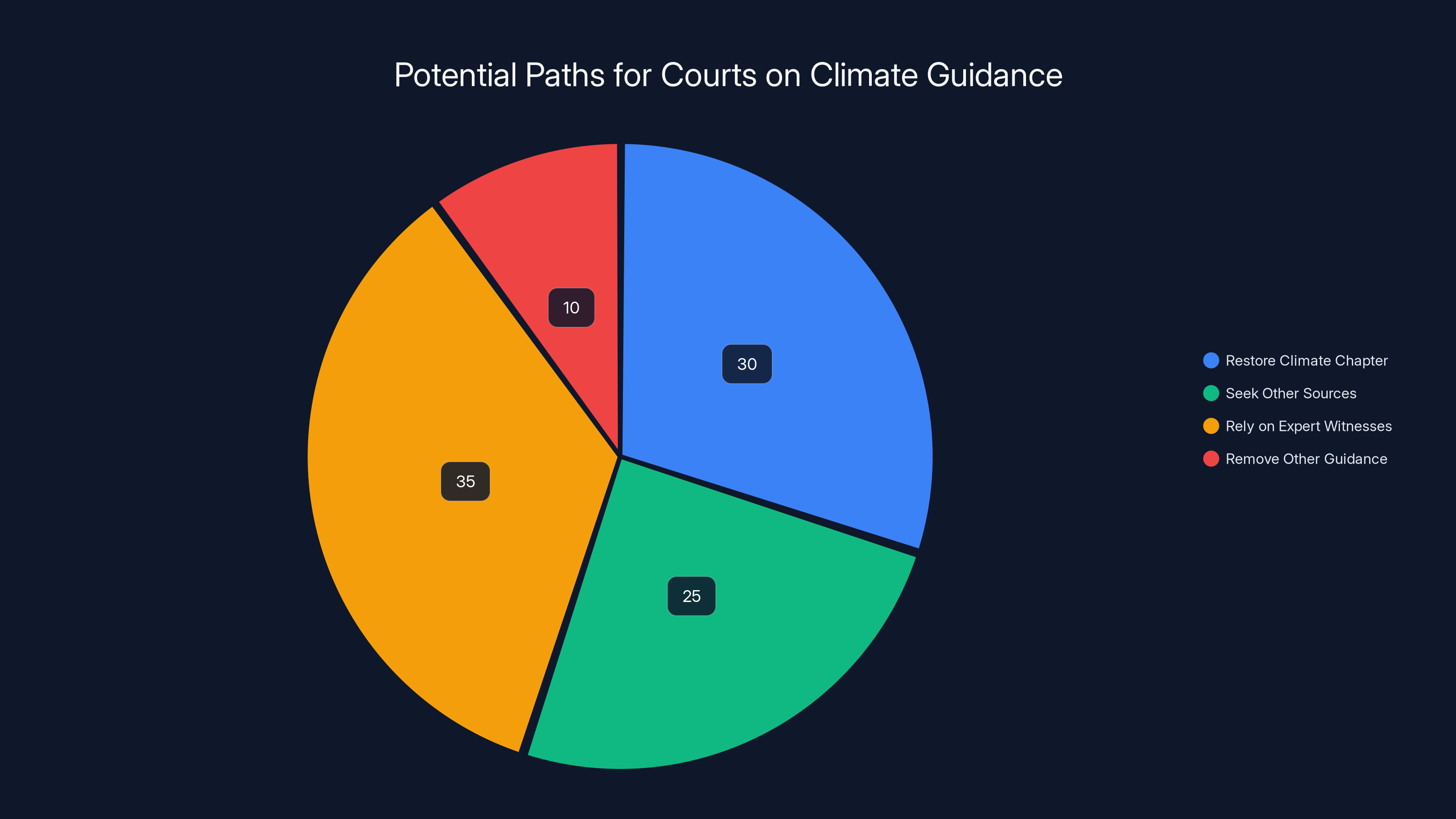

Estimated data suggests that courts are most likely to rely on expert witnesses, with a moderate chance of restoring the climate chapter or seeking other sources for guidance.

The Problem With Removing Scientific Guidance

Here's what happens now when judges face climate-related cases without the Reference Manual's guidance. They're on their own. No expert guidance. No distillation of scientific consensus. Just whatever expert witnesses show up to testify.

Imagine a case about property damage allegedly caused by climate-related extreme weather. An insurance company denies a claim, saying the damage was from an act of nature unrelated to climate trends. The homeowner argues it's connected to broader climate patterns. Both sides bring expert witnesses. One says climate change wasn't a factor. One says it was.

Without the Reference Manual, the judge has to figure out which expert is more credible based on... what? Gut feeling? Courtroom presentation skills? The ability to cite studies without context?

The Reference Manual would have provided a framework. It would have explained how climate science works, what the peer-reviewed evidence shows, and how to evaluate expert testimony on the subject. It would have given judges the tools to distinguish legitimate climate science from industry-funded denial.

Now that it's gone, the playing field tilts toward whoever can afford the slickest expert witness. And historically, that's been the side with deep industry funding and less concern for accuracy.

There's also a practical problem. If judges lack baseline guidance on what the scientific consensus is, they might give equal weight to fringe views and mainstream science. This is called false equivalence. A judge might think, "Well, one expert says climate change caused this damage, and one expert says it didn't. They cancel each other out." But that's not how science works. If 99.9 percent of peer-reviewed papers agree on something, and 0.1 percent disagree, those two positions aren't equally valid.

The Reference Manual would have helped judges understand that distinction. Now it won't.

How This Happened: Political Pressure on Judicial Independence

The Federal Judicial Center isn't supposed to be political. It's an independent agency created by Congress to help the judiciary function better. Its mission is improving the federal courts, not advancing partisan agendas.

But somewhere along the way, political pressure worked. State attorneys general complained about language they didn't like, and it got removed. The question is: why did the Federal Judicial Center cave?

One possibility is that removing the chapter felt easier than defending it. The Center didn't want to get dragged into a political fight. Maybe they calculated that avoiding controversy was worth sacrificing the accuracy of their guidance. That's a reasonable institutional calculation. It's also a catastrophic one if you care about judicial independence or scientific literacy.

Another possibility is that there's genuine uncertainty about how much judicial guidance should reflect scientific consensus versus remaining "neutral" on contested questions. Some might argue that judges shouldn't be told what science says, because that amounts to judges being instructed how to think about cases.

But that misses the point. The Reference Manual isn't telling judges how to rule. It's telling judges what constitutes legitimate evidence. There's a difference. A judge can understand that climate science is mainstream and still rule in favor of a defendant in a climate-related case, if the law and facts support that outcome. Understanding science doesn't dictate outcomes.

What's really happening here is that by removing the chapter, the Federal Judicial Center is arguably making judges less capable of doing their jobs. Judges need to understand what science says to fairly evaluate expert testimony. When a political pressure campaign causes them to lose that guidance, they're worse at their jobs, not better protected from bias.

Climate Cases and the Courtroom: What's at Stake

Climate-related litigation is exploding. Not climate litigation like the Sierra Club suing the government over environmental policy. But litigation where climate change is relevant to the case. Property damage cases. Insurance disputes. Corporate liability cases. Shareholder lawsuits. And it's only going to grow.

Consider some examples that are already in the courts or will be soon. A homeowner sues their insurance company for denying coverage on flood damage, arguing the flood was made worse by climate change. A coastal real estate investor sues a developer for misrepresenting climate risks. An energy company sues for damages from an extreme weather event, claiming it was unforeseeable. Shareholders sue a corporation for not adequately disclosing climate risks.

In every one of these cases, understanding climate science is relevant. Not controlling, but relevant. And judges need a baseline understanding of what the scientific consensus actually is.

Without the Reference Manual, judges will have less structured guidance on how to evaluate climate expert testimony. That creates opportunities for junk science to get equal standing with mainstream research. It opens doors for industry-funded experts to claim they're just as credible as university researchers, even when the evidence clearly shows otherwise.

Over time, this could distort how courts handle climate-related cases. Not through judges being explicitly biased, but through a simple lack of baseline knowledge about how climate science actually works.

An overwhelming 99.9% of peer-reviewed scientific papers agree that climate change is real and human-caused, highlighting a strong scientific consensus.

The Broader Implications for Judicial Independence

This situation raises a troubling question about judicial independence. If state attorneys general can pressure the Federal Judicial Center into removing guidance they don't like, what's next?

Could they pressure the Center to remove chapters on vaccine science? On election security? On genetic evidence in criminal cases? Once you establish that political pressure can result in censoring judicial guidance, where does it stop?

Judicial independence traditionally means judges can rule based on the evidence and law without political pressure. But that only works if judges have the information they need to make informed decisions. When political pressure is used to suppress that information, judicial independence is compromised.

The Federal Judicial Center made a choice. They could have stood by the Reference Manual and defended it as an educational document meant to improve judicial decision-making. They could have explained why removing a chapter on scientific consensus undermines the purpose of having the manual at all. They could have suggested revisions that addressed legitimate concerns while keeping the substance intact.

Instead, they removed the chapter. That sets a precedent. It says that if enough politicians complain about scientific guidance, the courts will fold.

What Other Scientific Bodies Are Saying

The broader scientific community took notice. The removal of the climate chapter prompted statements from scientific organizations that don't usually weigh in on judicial matters.

Scientific societies exist to maintain standards in their fields and to speak on behalf of their members when important issues come up. When a court system removes guidance about what science actually says, that's an important issue.

These organizations stressed that removing the chapter doesn't change what the science shows. It just means judges won't have expert guidance anymore. The climate change facts remain what they were. The peer-reviewed literature still overwhelmingly supports human-caused climate change. The IPCC is still the most comprehensive assessment of climate science available.

The removal of the chapter is a political action, not a scientific one. It's judges deciding to operate without scientific guidance, not scientists changing their conclusions.

One implicit message from this situation is worth noting: if you want to suppress scientific guidance, you can apparently do it through political pressure. You don't need better science. You don't need evidence. You just need enough political leverage to make the discomfort go away.

That's a dangerous precedent. It means that any sufficiently organized political group can potentially pressure courts into operating without scientific guidance on topics they care about. It means justice isn't about finding truth anymore. It's about whose political pressure is strongest.

The Role of Expert Witnesses in Climate Cases

Expert witnesses are how science enters the courtroom. When a case involves technical or scientific questions, parties call experts to explain it to the judge and jury. Those experts have credentials, research, publications, and experience.

But here's the problem: not all experts are equally credible. An industry-funded researcher who's published in questionable journals can look a lot like a tenured university professor who's published in top peer-reviewed journals, especially if both are testifying in court.

The Reference Manual would have helped judges distinguish between them. It would have explained how peer review works, what it means when someone's research hasn't been peer-reviewed, and how to evaluate whether an expert is mainstream or fringe.

Without that guidance, judges have to make these distinctions on their own. They have to figure out whether an expert is credible based on examining their CV, their testimony, and cross-examination. That's a lot harder when you don't have a baseline understanding of how legitimate research in that field actually works.

For climate cases specifically, this is a huge problem. The fossil fuel industry has a track record of funding researchers and institutions that produce studies claiming climate change is less serious than mainstream science says. Some of these researchers are credentialed. Some have published papers. But they're not representative of what the actual scientific community believes.

A judge without guidance might think, "Well, this expert says climate change is mainly natural variation, and this expert says it's mainly human-caused. They both seem credible. I'll give them equal weight." But that's not accurate. One position represents the overwhelming scientific consensus. The other represents a fringe view.

Estimated data shows the distribution of topics in the manual. Climate change, once a part of the manual, was removed, highlighting the impact of political influence on scientific documentation.

How This Compares to Other Scientific Denial Efforts

Removing scientific guidance from judicial documents isn't new in American history. But it's unusual for it to happen this transparently and this overtly.

During the tobacco wars of the 1990s, the tobacco industry funded research and researchers that cast doubt on the dangers of smoking. They didn't persuade the scientific community. But they did persuade some judges and juries that the evidence was more contested than it actually was.

Similarly, the fossil fuel industry has spent decades funding climate denial research. Again, they didn't persuade the scientific community. But they did persuade segments of the public and parts of the political system that climate change was more uncertain than it actually is.

What's different about this situation is the mechanism. Rather than trying to persuade people that the science is uncertain, the state attorneys general took the direct approach: just remove the guidance that tells judges what the science actually says.

It's a more efficient strategy, in a way. Instead of arguing about the science, just eliminate the document that summarizes the science. Problem solved.

Except it's not solved. The science doesn't change. Climate change is still real and human-caused. Judges still need to make decisions in climate-related cases. And now they'll do it with less information.

The Reaction From the Scientific and Legal Communities

The removal of the climate chapter generated significant response from both scientists and legal scholars. There was surprise that this could happen, frustration that it did, and concern about the precedent it sets.

Legal scholars noted that a Reference Manual is supposed to reflect current scientific understanding, not political preferences. If courts are going to have guidance documents, those documents should be accurate and evidence-based. Removing a chapter because politicians don't like its conclusions is incompatible with that principle.

Scientists noted that removing the chapter doesn't change the facts. It just means judges won't have expert guidance anymore. From a science perspective, it's irrelevant what courts decide about climate. The climate will keep changing based on physics, not judicial opinions.

But from a legal perspective, it matters tremendously. If courts can't accurately understand scientific evidence about climate, they'll make worse decisions in climate-related cases.

There was also discussion about whether the Supreme Court would intervene. Justice Kagan, who wrote the introduction to the Reference Manual, presumably noticed that her introduction references a deleted chapter. Whether that will lead to any action remains to be seen.

Implications for Other Science-Based Legal Guidance

Once you establish that judicial guidance can be removed based on political pressure, other scientific areas become vulnerable. What if state attorneys general who oppose vaccine mandates pressure courts to remove guidance on vaccine science? What if those skeptical of DNA evidence pressure courts to remove guidance on genetic evidence?

The principle is the same. If it's acceptable to remove scientific guidance because politicians don't like it, then any scientific guidance is at risk.

This is what's called the slippery slope problem. Once you've allowed the removal of judicial guidance on one scientific topic due to political pressure, you've created a precedent that makes it easier to do the same thing on other topics.

Some legal scholars worry this could eventually undermine the entire reference manual. If chapters can be removed whenever they're politically controversial, what's the point of having the manual at all?

Others argue that the scientific and legal communities need to be more proactive about defending evidence-based guidance. Don't wait for pressure to build. Explain why accurate scientific guidance is necessary for fair courts.

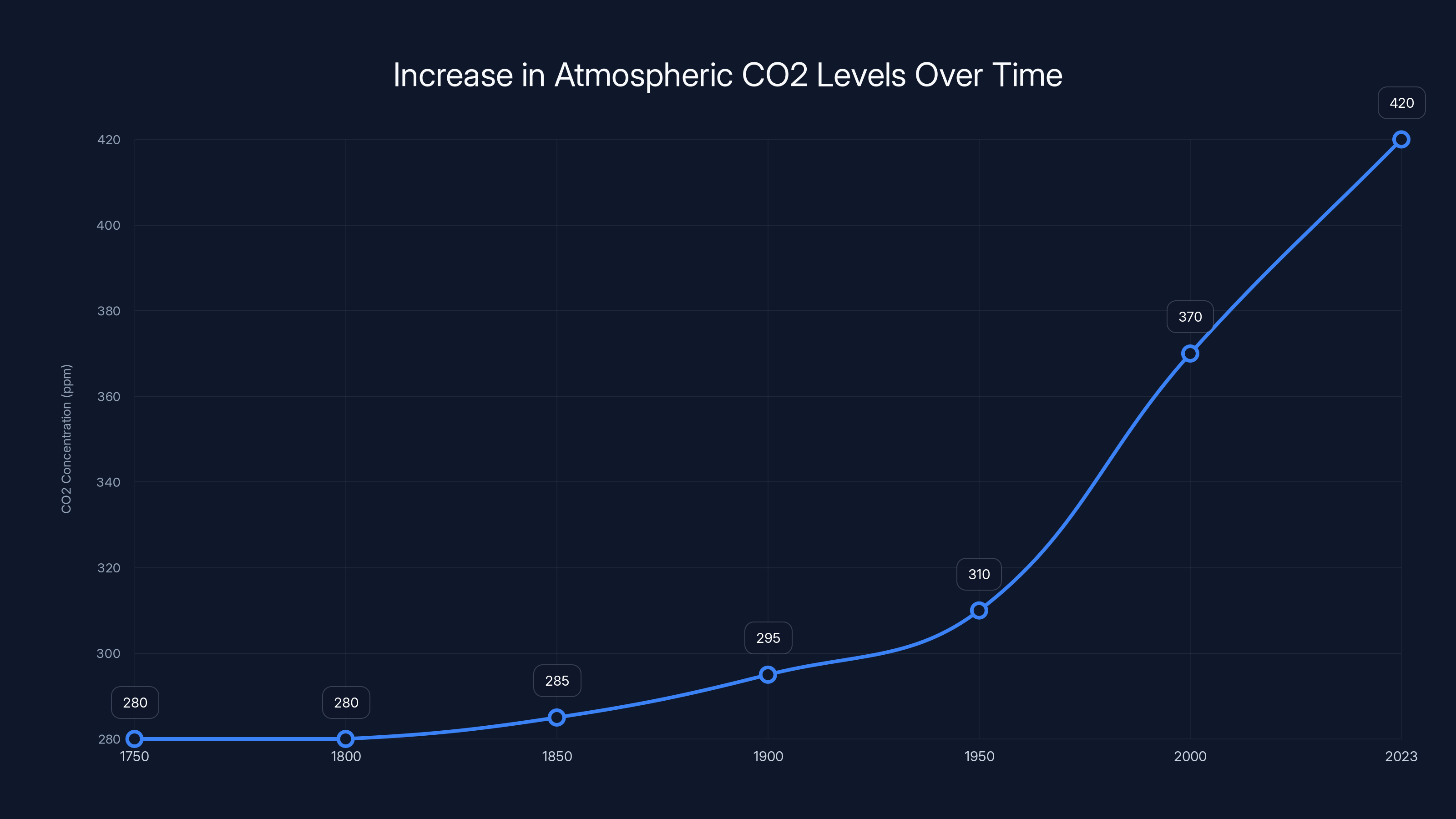

Atmospheric CO2 levels have risen from about 280 ppm in the pre-Industrial era to over 420 ppm today, illustrating the impact of fossil fuel combustion. Estimated data for early years.

What Judges Actually Need to Know About Climate Science

For judges who no longer have the Reference Manual's guidance, here's what they really need to understand about climate science.

First, the basic physics is not controversial among physicists. Carbon dioxide is a greenhouse gas. This was understood in the 1800s. When you increase the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, you trap more heat. This is physics, not politics.

Second, we've increased atmospheric CO2 from about 280 parts per million before the Industrial Revolution to over 420 ppm today. This is a measured fact. We know it happened because we can measure it now, and we can measure it in ice cores from centuries ago.

Third, that increase comes from burning fossil fuels. We can prove this through isotopic analysis of the carbon in atmospheric CO2. The carbon signatures show it comes from fossil sources, not natural variation.

Fourth, the warming we've observed matches what we'd predict based on increased greenhouse gas concentrations. We haven't just seen temperature go up. We've seen ice sheets shrink, sea levels rise, and weather patterns shift in ways consistent with climate change.

Fifth, alternative explanations have been tested and rejected. Solar variation? Doesn't explain the warming pattern. Volcanic activity? Doesn't fit the observations. Natural cycles? Not at this speed.

Sixth, the uncertainties in climate science are not about whether climate change is happening or whether humans are causing it. Those are settled. The uncertainties are about details: How sensitive is the climate to additional CO2? How much warming will we see by 2100? How will precipitation patterns change in specific regions?

These are important details for policy makers. But they're not relevant to whether judges should acknowledge that climate change is real and human-caused. That part is settled science.

The Path Forward for Courts and Scientific Guidance

So what happens now? Courts in the United States are operating without expert guidance on climate science. Climate-related litigation will continue to come before them. Judges will have to make decisions without the Reference Manual's help.

One possibility is that the Federal Judicial Center will eventually restore the climate chapter, either because of pressure to do so or because they realize removing it was a mistake. The introduction by Justice Kagan, which still references the deleted chapter, creates a kind of standing embarrassment.

Another possibility is that judges will seek guidance from other sources. There are textbooks on climate science. There are peer-reviewed journals. There are assessment reports from the IPCC and from the National Academy of Sciences. Judges could read these directly, though that's more time-consuming and less accessible than the Reference Manual.

A third possibility is that judges will just do the best they can without expert guidance, making decisions in climate cases based on the expert witnesses that appear before them and their own judgment about credibility.

What shouldn't happen, but might, is that the decision to remove the climate chapter becomes a template for removing other scientific guidance that's politically controversial. That would be a disaster for judicial decision-making.

The Federal Judicial Center should consider whether it wants to be a source of evidence-based judicial guidance or a source of politically acceptable guidance. It can't really be both. And if it chooses the latter, it has to accept that its guidance will become less useful over time.

Looking at the Bigger Picture: Science and Politics in America

This incident is part of a broader pattern in American politics where scientific consensus becomes treated as just another opinion to be debated.

We see this on climate change. We see it on vaccines. We see it on election security. Whenever there's scientific consensus that contradicts what some political actors want to believe, those actors start attacking the science.

Now, reasonable people can disagree about policy. Should we implement carbon taxes? Should we use nuclear power? Should we focus on adaptation or mitigation? These are legitimate policy debates, and people can hold different views based on different values.

But when the debate shifts from policy to facts, something's gone wrong. When people start claiming that the scientific consensus doesn't really exist, or that it's all political, they're adding a layer of denial on top of the policy disagreement.

Removing the climate chapter from the Reference Manual is a form of fact denial. It's saying, "We don't like what the science shows, so we're going to remove the document that tells judges what the science shows."

It won't change what the science actually shows. Climate change is still real. It's still human-caused. The peer-reviewed evidence still supports that overwhelmingly. Removing a chapter from a judicial reference manual doesn't change any of that.

But it does change how courts operate. It means judges have less expertise available to them when they're making decisions. And in the long run, that could mean worse decisions.

Estimated data suggests that political influence is a significant factor in judicial decisions on scientific cases, potentially overshadowing scientific evidence.

Practical Implications for Climate Litigation

If you're involved in climate-related litigation, either as a lawyer, judge, or litigant, here's what you need to know.

You can't rely on the Reference Manual for guidance on climate science anymore. That might actually be fine, depending on your case. Many climate-related cases involve straightforward questions about damages or causation that don't require deep climate science knowledge.

But if your case involves understanding whether climate change caused or contributed to something, you're going to need expert witnesses. And you're going to have to work harder to help the court understand which experts are credible.

If you're the party arguing that climate change played a role in damages, you'll probably call experts from universities or from organizations like the National Center for Atmospheric Research. These experts can cite the peer-reviewed literature showing the mainstream scientific consensus.

If you're the opposing party, you might call industry-friendly experts who claim the role of climate change is uncertain. Without the Reference Manual to help judges understand how to evaluate expert testimony, these experts might seem more credible than they actually are.

The solution is to be explicit in your questioning about how the expert's views compare to the broader scientific literature. Help the judge understand what mainstream climate science says and how your expert aligns with or diverges from that mainstream.

Make it clear that this isn't opinion. It's based on peer-reviewed research, multiple independent lines of evidence, and the consensus of scientists worldwide.

The International Dimension

It's worth noting that removing scientific guidance from courts based on political pressure is not standard practice in other democracies. In the EU, courts work with scientific guidance that reflects the consensus of the scientific community. Same in Canada, Australia, and other developed democracies.

The US is somewhat unique in the degree to which courts have become political battlegrounds. The federal judiciary is appointed for life, which in theory makes judges independent of politics. But increasingly, the selection of judges has become partisan, and the decisions judges make have become predictable based on their political preferences.

When you add to that the willingness to remove scientific guidance based on political pressure, you're looking at a system where courts are increasingly unlikely to make decisions based on evidence.

From an international perspective, this looks like the US judicial system is becoming less functional, not more. Countries that have strong rule of law tend to have courts that respect expert guidance and scientific evidence.

What Would a Solution Look Like?

Ideally, the Federal Judicial Center would restore the climate chapter to the Reference Manual. They could do this with a note explaining that the chapter reflects the current scientific consensus and that judges are expected to understand that consensus when evaluating expert testimony.

Alternatively, they could create a supplementary document specifically for judges handling climate-related cases. Something that explains the basics of climate science in a way that judges can understand.

Or they could update the Reference Manual with a new chapter that responds to the concerns raised by the state attorneys general while still maintaining accuracy about what science shows. Something like: "Here's what the scientific consensus is. Here are the outlier views that exist. Here's how to evaluate expert testimony on these topics."

They could also be more proactive about defending the Reference Manual. When political pressure comes, explain why evidence-based guidance is important for courts. Don't just fold.

But the core principle should be that judicial guidance documents reflect the actual state of scientific knowledge, not the political preferences of whoever happens to be in power.

Without that commitment, courts become less capable of making good decisions in cases involving technical or scientific questions. And society as a whole suffers when courts make bad decisions based on incomplete information.

The Chilling Effect on Scientific Guidance

One of the subtler consequences of removing the climate chapter is the chilling effect it has on scientific guidance more broadly.

The Federal Judicial Center's mission is to help the federal judiciary function better. That includes creating guidance documents. But now judges and staff at the Center know that if a guidance document becomes politically controversial, there's a risk it will be removed.

That might make them more cautious about documenting what science actually says. It might lead them to soften language, hedge findings, or avoid controversial topics altogether.

Over time, this could result in judicial guidance that's less informative and less useful. Documents might start reflecting political compromise rather than scientific accuracy.

That's a long-term threat to the quality of judicial guidance. Once you've established that political pressure can result in removal, you've incentivized creating less controversial (and often less accurate) guidance.

Scientific integrity depends on the ability to follow evidence wherever it leads, without fear that conclusions will be suppressed if they're inconvenient. That principle should apply to judicial guidance just as much as it applies to scientific research.

Lessons From History

Historically, suppressing scientific guidance or evidence has not gone well.

The tobacco industry's efforts to cast doubt on the dangers of smoking delayed public health action for decades. People died from lung cancer who might have lived if the scientific consensus had been taken seriously earlier.

The fossil fuel industry's efforts to cast doubt on climate change have delayed climate action for decades. We've now locked in warming that could have been avoided if we'd acted on the scientific consensus earlier.

When you suppress scientific guidance or evidence, you don't change the facts. You change decisions. And often, you change them for the worse.

Removal of the climate chapter from the Reference Manual isn't going to change the climate or the science. But it will likely lead to worse decisions in climate-related litigation. It will allow fringe views to seem as credible as mainstream science. It will make it easier for parties with resources to manufacture doubt.

This is what happens when courts operate without expert guidance on scientific matters. Justice suffers. Truth suffers. And over time, the legitimacy of the entire system suffers.

What Courts Can Do Going Forward

Even without the Reference Manual's guidance on climate, courts can take steps to make better decisions in climate-related cases.

Judges can educate themselves about climate science through reading peer-reviewed literature, attending seminars, or consulting with scientific experts outside of litigation. The information is available. It just requires effort.

When evaluating expert testimony, judges can ask experts how their views compare to the broader scientific literature. Do they publish in mainstream peer-reviewed journals? Are their views consistent with major scientific institutions like the National Academy of Sciences or the IPCC?

Judges can also be transparent about the limitations of their knowledge. If you don't understand climate science, say so. Call an expert to explain it. Don't pretend to understand when you don't.

And judges can resist pressure to decide cases based on political convenience rather than evidence. That's the whole point of having an independent judiciary. If judges start making decisions based on what politicians want, the judicial system stops serving justice.

The Broader Conversation About Science and Policy

This incident is ultimately about something bigger than climate litigation. It's about how society makes decisions in the face of scientific evidence.

Science can't tell you what values to prioritize. It can't tell you whether you should prioritize economic growth over environmental protection, or immediate development over long-term sustainability. Those are value judgments that involve politics and culture.

But science can tell you what the evidence shows about cause and effect. And when courts are deciding cases, they need to understand that evidence.

You can believe, for whatever reason, that we shouldn't do much about climate change. You can think the economic costs of climate action are too high. You can prioritize other concerns. Those are legitimate positions.

But they're not positions that should be based on denying what the science shows. They should be based on honest disagreement about values and priorities, given an accurate understanding of the facts.

Removing the climate chapter from the Reference Manual pushes courts toward the opposite approach. It encourages them to make decisions while misunderstanding or ignoring what the science actually says.

That's bad for courts. It's bad for justice. And it's bad for society.

Restoring Integrity to Judicial Guidance

If the Federal Judicial Center is going to maintain credibility as a source of expert guidance for courts, it needs to restore the climate chapter or explain why it's not doing so.

The introduction by Justice Kagan still references the deleted chapter. That creates an implicit acknowledgment that something's wrong. The introduction should either be updated to remove the reference, or the chapter should be restored so the reference makes sense.

Beyond that, the Center needs to establish clear principles for how decisions about guidance documents are made. If scientific accuracy is the standard, then politically motivated complaints shouldn't be sufficient grounds for removal. If political acceptability is the standard, then the Center should be honest about that.

Courts depend on having access to expert guidance. That guidance needs to be accurate and evidence-based. When courts lose access to that guidance, they become less capable of making good decisions.

The removal of the climate chapter is a step backward for the American legal system. The question now is whether the system will move forward again or whether this becomes a new normal where scientific guidance can be suppressed based on political pressure.

Final Thoughts: The Stakes

The removal of the climate chapter from the Reference Manual might seem like a minor bureaucratic decision. A document updated, a chapter deleted, judges notified. Nothing dramatic.

But it's actually a significant moment. It's an example of political pressure successfully suppressing scientific guidance from courts. And it sets a precedent that this is acceptable.

In a well-functioning democracy with a strong rule of law, this wouldn't happen. Courts would maintain their independence and courts would be guided by evidence. But we live in a system where political pressure can result in the removal of expert guidance.

That has implications beyond climate litigation. It affects how courts make decisions in any case involving scientific evidence. And it affects the legitimacy of the courts in the eyes of people who care about evidence-based decision-making.

The courts are supposed to be a place where truth matters. Where evidence is weighed. Where justice is based on facts, not politics. When courts start suppressing guidance about what the facts show, they undermine that fundamental purpose.

The climate chapter removal is a warning. It shows that the independence of the judiciary and the commitment to evidence-based decision-making can be compromised by political pressure. The question now is whether that precedent will stand or whether it will be reversed. The answer to that question matters a lot more than it might initially appear.

FAQ

What is the Reference Manual on Scientific Evidence?

The Reference Manual on Scientific Evidence is a comprehensive guide published by the Federal Judicial Center to help judges understand and evaluate scientific evidence in legal cases. It's nearly 2,000 pages long and covers topics ranging from expert witness standards to statistical significance to specific scientific fields like climate science. The manual helps judges make informed decisions when cases involve complex technical or scientific matters.

Why did the Federal Judicial Center remove the climate chapter?

The Federal Judicial Center removed the climate chapter after receiving a complaint letter from Republican state attorneys general who objected to language describing climate change as human-caused and referring to the IPCC as an authoritative scientific body. Rather than revising the chapter or defending its accuracy, the Center chose to remove it entirely. The exact reasons for this decision weren't publicly detailed, though institutional reluctance to engage in political controversy likely played a role.

What does the scientific consensus say about climate change?

More than 99.9 percent of peer-reviewed scientific papers agree that climate change is real and caused by humans. This consensus is supported by major scientific institutions worldwide, including the National Academy of Sciences, NASA, and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. The science has been established through multiple independent lines of evidence: atmospheric measurements, ice core data, observations of melting ice sheets, sea level rise, and measurements of human carbon dioxide emissions.

How will the removal of the climate chapter affect climate litigation?

Without the Reference Manual's guidance on climate science, judges will lack expert guidance when evaluating expert testimony in climate-related cases. This could lead to false balance between mainstream scientific views and fringe views. Judges will have to rely more heavily on expert witnesses who appear before them and may be more vulnerable to industry-funded experts who deny or minimize climate change risks.

Can the climate chapter be restored?

Yes, it's possible. The Federal Judicial Center could restore the chapter, issue a supplementary document on climate science for judges, or create a new version that addresses concerns while maintaining scientific accuracy. There's no permanent policy preventing restoration. Several legal scholars and scientific organizations have suggested that restoration would be appropriate.

What would an ideal judicial guidance document on climate science look like?

An ideal document would explain the basics of climate science in accessible language for judges, describe the peer-reviewed research consensus, explain how to evaluate expert testimony on climate topics, and discuss the distinction between settled scientific questions (like whether climate change is happening and whether humans are causing it) and unsettled questions (like precise regional impacts). It would help judges distinguish credible experts from those representing fringe views.

Are other countries' courts removing climate guidance?

No. In other developed democracies like Canada, the EU, and Australia, courts continue to rely on scientific guidance that reflects the consensus of the scientific community. The removal of guidance based on political pressure is not standard practice in other functional democracies and would be seen as a threat to rule of law.

What can judges do without the Reference Manual's guidance?

Judges can educate themselves independently by reading peer-reviewed literature, attending seminars on climate science, or consulting with scientific experts outside of litigation. When evaluating expert testimony, judges can ask about the expert's publication record, whether their work appears in mainstream peer-reviewed journals, and how their views compare to major scientific assessments like the IPCC reports.

Does removing the chapter change what the science shows?

No. The science doesn't change because a judicial document is removed. Climate change is still real, still human-caused, and still supported by overwhelming evidence. Removing the chapter just means judges won't have expert guidance to help them understand that evidence.

What's the broader significance of this decision?

The removal of the climate chapter sets a precedent that political pressure can result in the suppression of scientific guidance from judicial documents. This threatens the long-term integrity of the judicial system's ability to make evidence-based decisions. It also creates uncertainty about whether other scientific guidance might be vulnerable to similar pressure campaigns based on political disagreement with scientific findings.

Key Takeaways

- The Federal Judicial Center removed its climate science guidance chapter from the Reference Manual after Republican state attorneys general complained about its description of human-caused climate change

- Over 99.9 percent of peer-reviewed scientific papers agree climate change is real and human-caused, making the removal a suppression of established scientific consensus

- Without judicial guidance on climate science, judges lack expert resources when evaluating expert testimony in climate-related litigation cases

- This sets a dangerous precedent that political pressure can result in removing scientific guidance from court documents, threatening judicial decision-making across multiple fields

- Courts in other developed democracies maintain evidence-based guidance documents, making the US approach unusual and concerning for rule of law and judicial independence

Related Articles

- Climate Science Removed From Judicial Advisory: What Happened [2025]

- COVID-19 Cleared Skies but Supercharged Methane: The Atmospheric Paradox [2025]

- 2026 Winter Olympics Environmental Impact: Snowpack Loss and Climate Crisis [2025]

- AI Data Centers Drive Historic Gas Power Surge [2025]

- Data Centers & The Natural Gas Boom: AI's Hidden Energy Crisis [2025]

- Doomsday Clock at 85 Seconds to Midnight: What It Means [2025]

![Judicial Body Removes Climate Research Paper After Republican Pressure [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/judicial-body-removes-climate-research-paper-after-republica/image-1-1770743331239.png)