FCC Lifeline Fraud Battle: What's Actually Happening With California's Dead Subscribers

Last month, the FCC and California locked into a public fight that sounds absurd on its face: the federal government is accusing California of giving phone subsidies to dead people. The state fired back saying the feds are blowing things out of proportion. And somewhere in between? There's actually a real problem—it's just way more complicated than the headlines suggest.

Let me break down what's happening, why it matters, and what the actual numbers tell us that both sides aren't saying out loud.

TL; DR

- The Dispute: FCC Chair Brendan Carr claims California improperly paid nearly $5 million in Lifeline subsidies to deceased subscribers between 2020 and 2025, as detailed in a Breitbart report.

- California's Defense: Deaths happen while people are enrolled; there's natural lag time between death and account closure.

- The Real Problem: At least 16,774 people were enrolled AFTER they died, though potentially 39,362 if you count uncertain cases, according to New York Post.

- The Money: About 1 billion annual program serving 9 million households.

- What's Changing: FCC proposing stricter nationwide eligibility rules including full SSN collection and federal verification systems, as reported by Light Reading.

- The Politics: Two competing visions of what "fraud" means in a massive social benefit program.

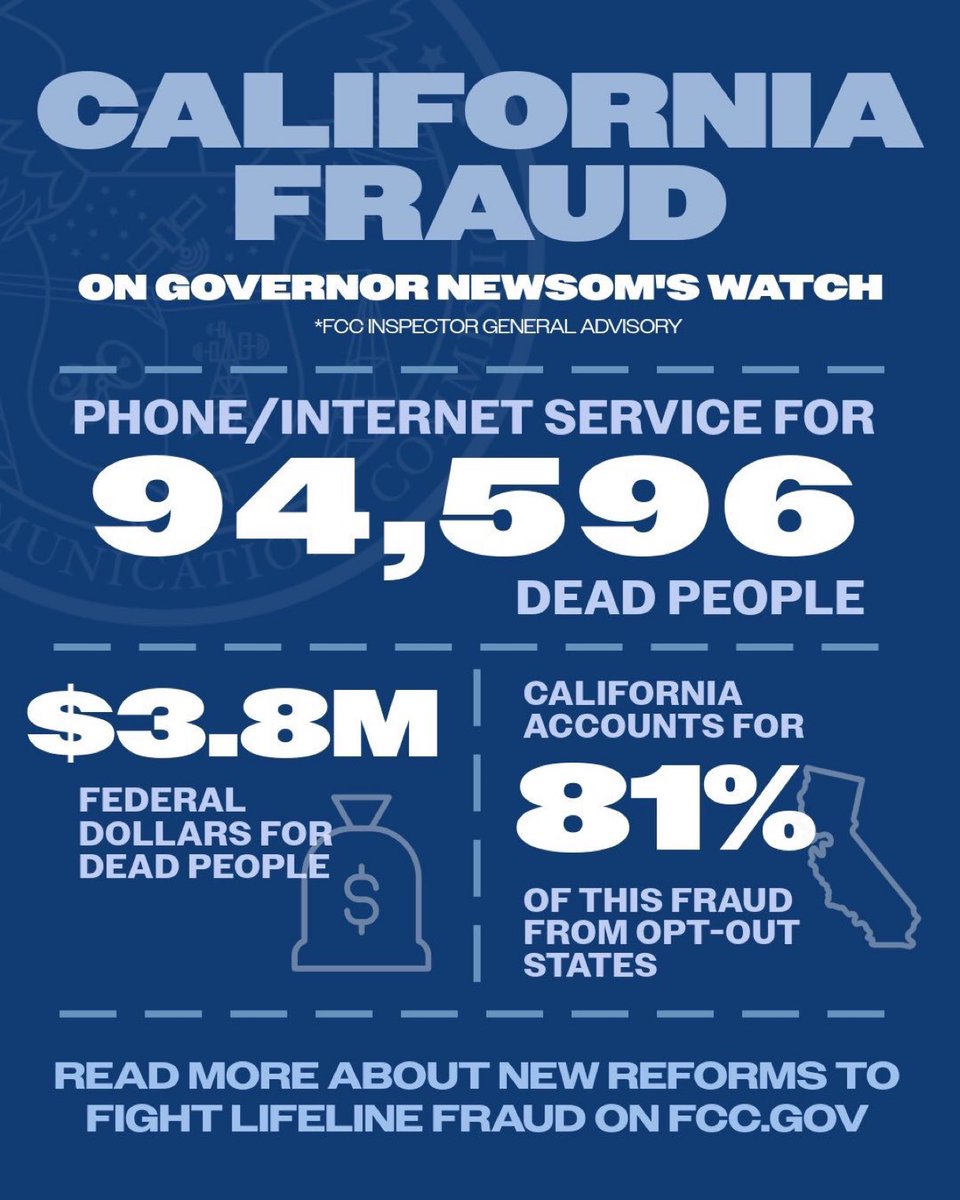

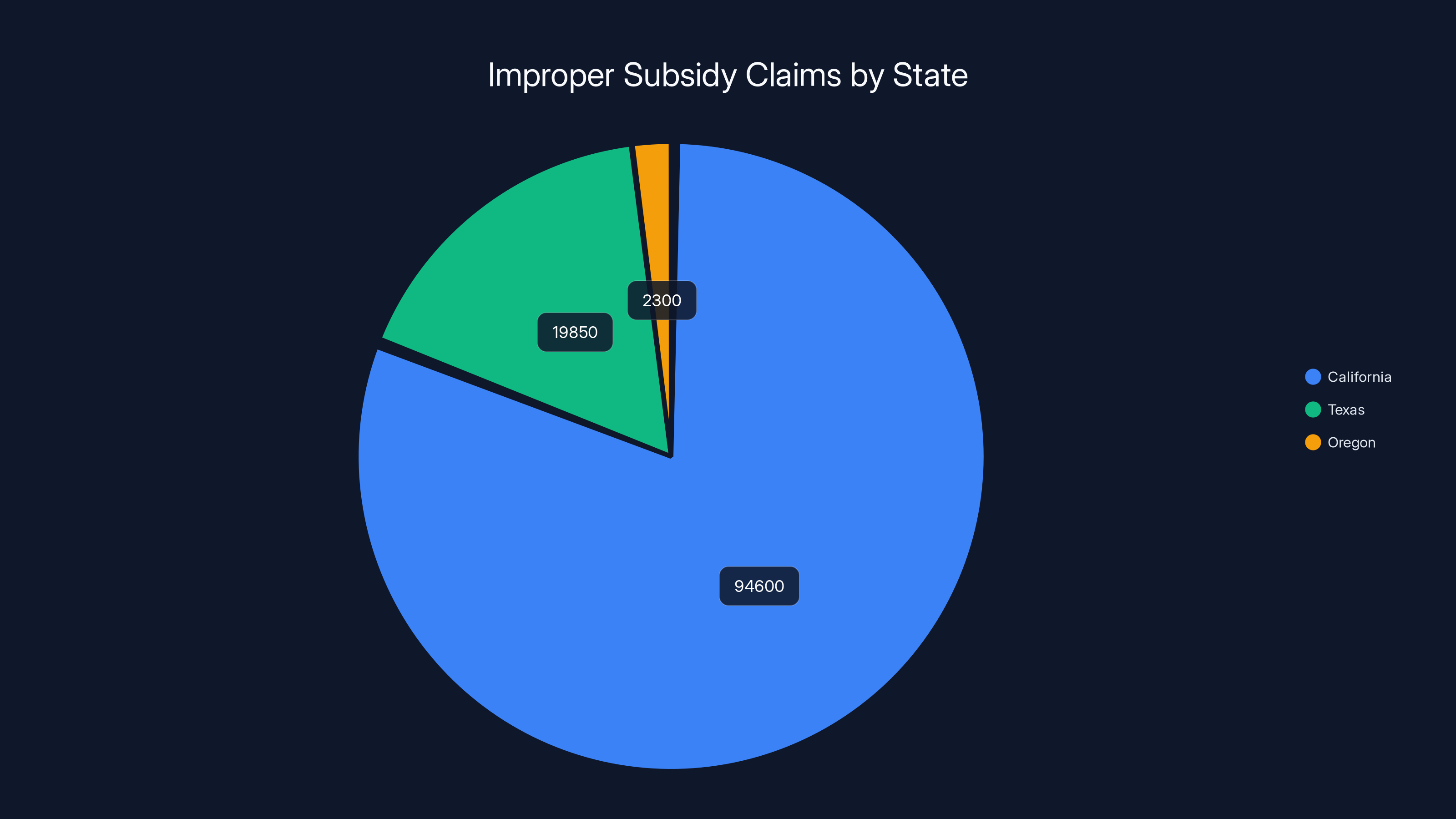

California accounted for 81% of the deceased subscribers receiving Lifeline benefits, highlighting significant oversight issues in the state's verification system.

Understanding the Lifeline Program: Why This Matters

Before you can understand why this fight is happening, you need to know what Lifeline actually is and why it exists.

The Lifeline program is a federal subsidy that helps low-income Americans afford telecommunications services. It's been around since 1985, created during the Reagan administration when someone actually thought poor people should have access to phone service. The program started small—it was literally about landlines back then. But it's evolved.

Today, Lifeline gives eligible households up to

Here's the core issue: the program is means-tested, which means you have to qualify based on income. The federal poverty line sits around 135-200% of the federal poverty level for most states, though some states set it lower. You have to prove you're poor enough to get the subsidy. That's where the verification problem begins.

The FCC created something called the National Lifeline Accountability Database (NLAD) to track who's enrolled and make sure people aren't enrolled in multiple states at once (you can only get one household subsidy). But not all states use it. California, Texas, and Oregon are "opt-out states"—they use their own verification systems instead of the federal database. That's important because it means there's less federal oversight of how these states manage the program.

The Inspector General Report: What the Numbers Actually Show

Let's talk about the evidence that started this whole fight, because the numbers are weird and both sides are interpreting them differently.

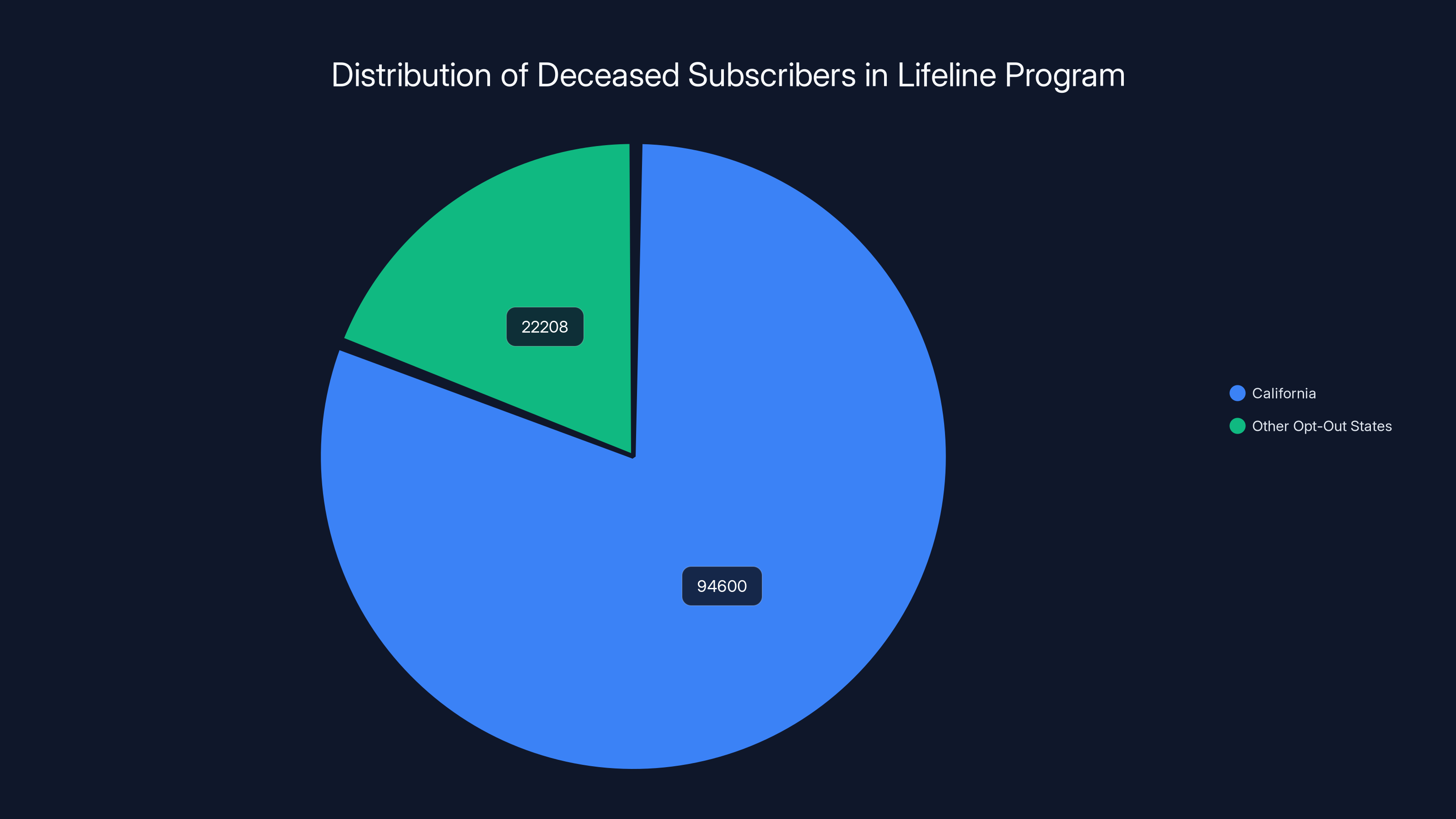

The FCC's Office of Inspector General released a report covering the period from 2020 to 2025. They found that telecommunications providers claimed subsidies for 116,808 deceased subscribers across the three opt-out states. The breakdown:

- California: 81% of cases (about 94,600 people)

- Texas: 17% of cases (about 19,850 people)

- Oregon: 2% of cases (about 2,300 people)

These dead people got about **

But here's where it gets important: when did these people actually enroll?

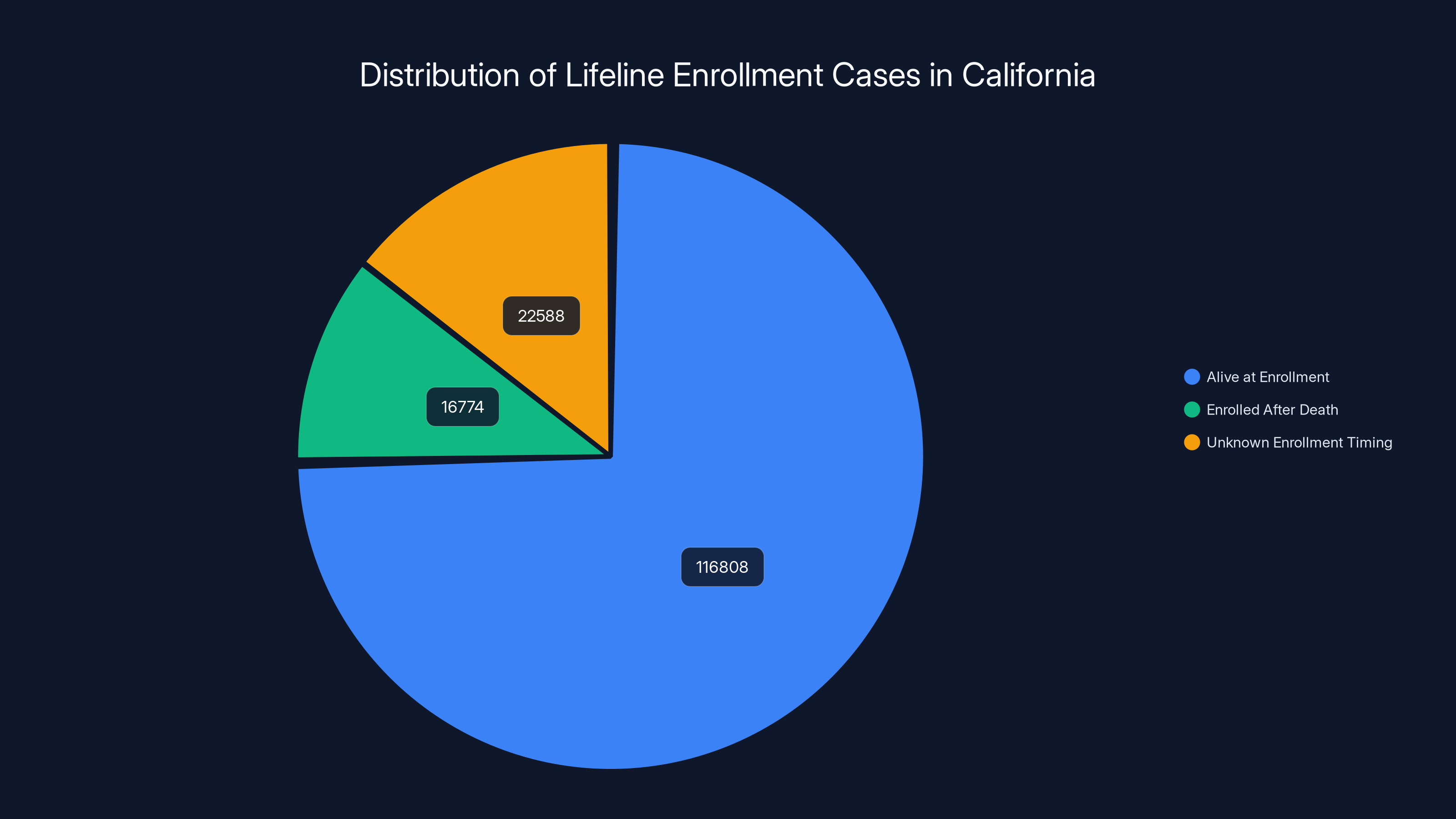

Two-thirds of the 116,808 deceased subscribers (about 77,446 people) had already enrolled while they were alive. They died while on the program, and their accounts kept getting subsidized after death. The providers continued seeking support for an average of 4.4 months after the person died.

The remaining third—somewhere between 16,774 confirmed cases and potentially 39,362 if you count the uncertain ones—were enrolled after they were already dead. That's genuinely suspicious. Someone or something is enrolling dead people in the system and claiming subsidies for them.

How long did these post-mortem enrollments last? The providers kept billing for an average of 3.4 months after the person's death. Some cases went on for up to 54 months (four and a half years). That's not administrative lag. That's systematic non-compliance.

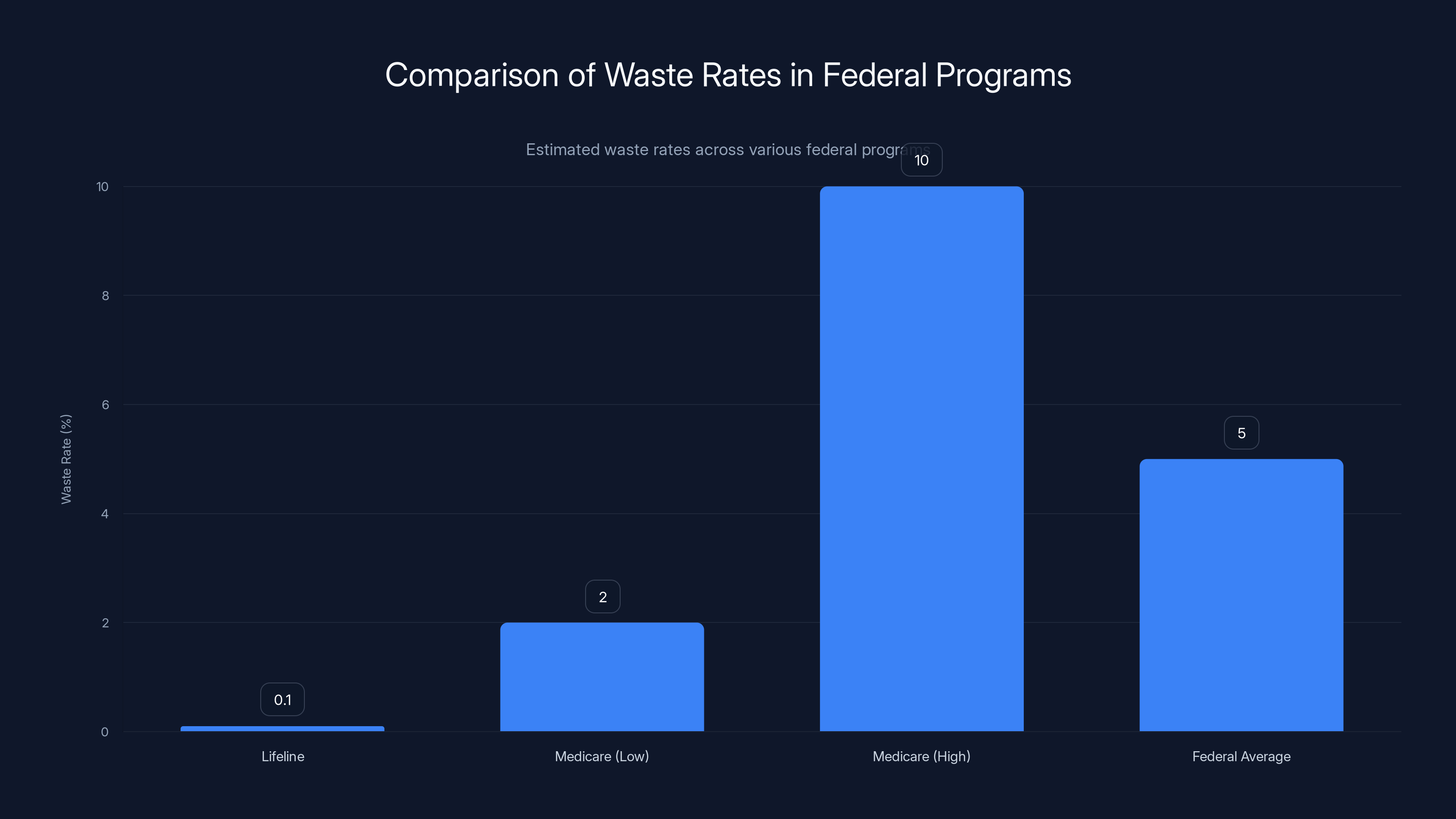

Lifeline's waste rate of 0.1% is significantly lower than Medicare's estimated 2-10% and the federal average of 5%. Estimated data.

Brendan Carr's Argument: Fraud is Fraud

FCC Chair Brendan Carr is not hiding his position. He's been clear and vocal: the government shouldn't be spending taxpayer money on phone service for dead people, period.

Carr's basic argument is straightforward. First, the Inspector General report identified tens of thousands of people who were enrolled after they had already died. That's not administrative lag. That's someone in the system enrolling a dead person and continuing to collect subsidies for them. That's fraud, plain and simple.

Second, Carr points to the fact that even for the people who died while enrolled, providers kept billing for months and months afterward. If California's own system is supposed to verify eligibility, why didn't they catch that people were dead and shut down the accounts immediately?

Third, Carr notes that this problem is massively concentrated in California. While all three opt-out states have the problem, California accounts for 81% of the dead people fraud. That suggests it's not just a nationwide administrative issue—it's something specific to how California manages the program.

Carr's response to California officials has been pointed. When Governor Newsom suggested this is just natural lag time between death and account closure, Carr shot back saying that's "completely unacceptable" and that Newsom is "putting out a lot of misinformation."

Here's Carr's core argument: if you want to collect federal money, you have to follow federal rules. California agreed to those rules when it opted out of the NLAD system. If California can't verify eligibility properly, it shouldn't be allowed to keep that opt-out status. And to make sure this never happens again, the FCC should implement stricter enrollment rules nationwide that require full Social Security numbers and federal verification of citizenship and eligibility.

Carr is a Republican appointee (he was nominated by Trump and retained by Biden). He's made his political reputation on complaints about waste and fraud in federal programs. This isn't just policy to him—it's his wheelhouse.

California's Defense: Death Happens in Large Programs

California's response isn't to deny the dead people. It's to reframe what the numbers actually mean.

The California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) makes a simple point: "People pass away while enrolled in Lifeline. That's not fraud. That's the reality of administering a large public program serving millions of Americans."

Think about it from their perspective. If you have 9 million people in a program, some of them are going to die every year. That's just demographics. The question isn't whether people die—it's whether the state responds appropriately when they do.

California argues that the vast majority of the 116,808 cases involved people who were alive and eligible when they enrolled. The issue is just that there's lag time between when someone dies and when their account gets closed. Death records have to make their way from local vital statistics offices to the state program, then to the providers, and then the providers have to stop billing. In a bureaucracy, that takes time.

California even challenges Carr's math. The Inspector General report could only definitively say that 16,774 people were enrolled after they died. The other 22,588 cases? Nobody knows when they actually enrolled because California's opt-out system doesn't track enrollment dates. Carr is treating those unknown cases as post-mortem fraud, but California says they were probably alive when enrolled too.

Moreover—and this is important—California points out that this isn't unique to them. Yes, California has 81% of the cases. But that's partly because California has way more people in the program than Texas or Oregon. California represents about 37% of all U.S. population, so it makes sense they'd have more everything, including more dead people in government programs.

Governor Newsom's office added a political dig: "This is a nationwide issue, not a California scandal." In other words, every state has the same problem. Carr is singling out California for political reasons.

The Enrollment Problem: When Dead People Get Newly Enrolled

Here's where things get genuinely concerning, and where California's "it's just lag time" argument breaks down.

Remember: between 16,774 and 39,362 people were enrolled in Lifeline after they were already deceased. That's not lag time. That's someone actively enrolling a dead person in the system.

How does that happen? There are a few possibilities:

First, fraud on the provider side. A customer service representative at a telecom company takes money to enroll a fake customer using a dead person's name and Social Security number, then bills Lifeline for it. This is a federal crime, but it happens.

Second, fraud on the enrollment side. An enrollment agent or application processor submits an application for someone who's already dead, either because they didn't check, or because they were paid to look the other way. Again, this is fraud.

Third, identity theft. Someone steals a dead person's identity and enrolls them in Lifeline to collect the subsidy themselves. This is also fraud.

Fourth, bureaucratic failure. The death record hasn't been processed yet, so the system doesn't know the person is dead, and someone legitimately applies for assistance on their behalf (maybe a family member)—and the system processes it before the death record updates. This is the least criminal, but it still shouldn't happen if the system is working.

The Inspector General report doesn't definitively distinguish between these scenarios. That's part of what makes this so complicated. We know post-mortem enrollments are happening. We don't always know why.

But here's the thing: California doesn't have a clear system to prevent it. The opt-out states don't have to use NLAD, which means they're not checking against the national database to see if someone's already dead. They're relying on their own internal verification systems. And apparently, those systems have gaps.

Social Security Administration death records are public information. States have access to them. If you're running a major benefits program, you should be checking applicants against death records before you approve them for enrollment. California apparently isn't doing that systematically, or if it is, the system is failing.

California accounted for the majority (81%) of improper subsidy claims involving deceased subscribers, highlighting a significant issue in that state compared to Texas and Oregon.

The Proposed Solutions: Stricter Rules Nationwide

Carr's NPRM (Notice of Proposed Rulemaking) is his response. He's proposing several specific changes:

First, require full Social Security numbers from applicants. Right now, some states use partial SSNs or other forms of ID. Full SSNs would make it easier to cross-reference against Social Security death records.

Second, use the Citizenship and Immigration Services' Systematic Alien Verification for Entitlements (SAVE) program to verify eligibility. SAVE connects to federal immigration databases. This would ensure people are documented immigrants or U.S. citizens.

Third, eliminate state opt-out authority. Currently, states like California can use their own verification processes instead of the federal NLAD. Carr wants to end that and make everyone use the federal system.

Fourth, other changes to "ensure that Lifeline money goes to only living and lawful Americans" who meet low-income guidelines.

These are not subtle changes. They're a significant federal power grab, taking verification authority away from states and centralizing it in Washington. And that's where the political debate really gets hot.

The Democratic Pushback: Who Pays the Price?

Not everyone on the FCC agrees with Carr's approach. The lone Democratic commissioner, Anna Gomez, has come out swinging against the proposal.

Gomez's argument is that Carr's "cruel and punitive eligibility standards" will hurt the very people the program is designed to help: low-income Americans who actually need the subsidy. She's not defending California's fraud problem. She's questioning whether Carr's solution is proportionate.

Here's the concern: stricter eligibility requirements might prevent fraud, but they'll also prevent eligible people from getting the benefit. If you require full SSNs and federal verification, some people won't be able to provide it. Immigrants, homeless people, and elderly individuals sometimes don't have Social Security numbers readily available. Naturalized citizens might have documentation issues. People with bad credit or financial problems might avoid anything that requires federal verification.

The result could be that you prevent 200 fraudulent claims but also prevent 2,000 legitimate claims. In program administration, that's called a Type II error—rejecting people who should be approved. And it affects the exact population you're trying to help.

Moreover, there's a question about whether the fraud level actually justifies the crackdown. We're talking about

Gomez seems to be arguing that Carr is using a sledgehammer to kill a fly. And she's got a point.

Why California Got Its Opt-Out Status Revoked

This context is important: the FCC already revoked California's opt-out status in November 2025, before even proposing the new nationwide rules.

That was Carr's previous move. He said California has demonstrated it can't manage its own verification process effectively, so it no longer gets to do so. California will have to start using NLAD.

This is a big deal for the state. It means giving up autonomy over how the program is administered. It also means accepting federal oversight that California has avoided for over two decades.

Texas and Oregon still have opt-out status, but they're in the hot seat now too. Carr's implicit message is: clean up your act or we revoke your opt-out status too.

The majority of Lifeline cases in California involved individuals who were alive at enrollment. Only 16,774 were definitively enrolled post-mortem, with 22,588 cases having unknown enrollment timing.

The Bigger Issue: How Many Dead People Are In Federal Programs?

Here's something worth thinking about beyond just Lifeline. The dead people problem isn't unique to this program.

Social Security overpayments happen when someone dies and their benefits keep getting paid. Medicare has the same issue. Medicaid. SNAP. Veterans benefits. Any large federal benefit program has dead people on the rolls. The question is how long it takes to get them off.

The reason this matters is that these programs, collectively, likely leak hundreds of millions of dollars per year to deceased beneficiaries. Social Security itself has estimated that overpayments to deceased individuals amount to millions per year, though the exact number is hard to pin down.

So Carr's argument isn't just about Lifeline. It's about whether the federal government is going to implement modern verification systems across all federal benefit programs, or whether it's going to keep using outdated systems that don't catch dead people until months or years after death.

California's argument is also bigger than Lifeline. It's about whether the federal government should maintain some flexibility for state-level administration of federal programs, or whether everything should be centralized and standardized.

The Numbers in Context: Is 0.1% Waste Really a Scandal?

Let's do some math to figure out if this is actually a big problem or if it's political theater.

Total improper payments over five years:

Per year, that works out to about

For comparison:

- Medicare fraud is estimated at 2-10% of total program spending (900 billion program)

- Improper payments across all federal programs total around $200 billion per year (about 5% of all federal spending)

- The Lifeline waste rate is 0.1%, which is 50 times better than the federal average

So here's the thing: Lifeline's fraud and improper payment problem is actually tiny compared to other federal programs. That doesn't mean it should be ignored. But it does mean the scale of the crisis is debatable.

California looks at these numbers and says, "This is a well-run program with a minor issue." Carr looks at the same numbers and says, "Even one dead person is one too many." Both perspectives are reasonable. The question is which one should drive policy.

The Verification Challenge: How Do You Actually Know Someone's Alive?

Here's something people don't always think about: verifying that someone is alive is actually harder than it sounds.

The Social Security Administration maintains a death master file (technically, it's called the Social Security Death Index, or SSDI). When someone dies, their death is supposed to be reported by states, funeral homes, and family members to Social Security. But there are gaps. Not all deaths are reported immediately. Some death certificates get lost in bureaucracy. Some people die in one state but their records are in another.

The time lag between actual death and when SSA gets the notification can be weeks, months, or even years. So even if a state is checking against the death master file, it won't catch someone who died last week but whose death hasn't been reported yet.

Also, people sometimes have multiple Social Security numbers (usually unintentionally, due to clerical errors). Someone might be alive under one SSN but appear dead under another. The verification systems have to be sophisticated enough to catch that.

Further, some people legitimately don't have Social Security numbers. Undocumented immigrants, some elderly people, and people with religious objections have lived their entire lives without SSNs. If you make SSN a hard requirement for the program, you're automatically excluding those people from benefits.

So California's argument that death verification is complicated and has lag time? That's not wrong. But the solution can't be to just accept that dead people will stay on the rolls for months at a time.

What it should be is a systematic process: check against death records at enrollment, check regularly while someone's on the program, remove people within 30 days of their death being reported. That's not unreasonable, and California hasn't demonstrated it's doing that.

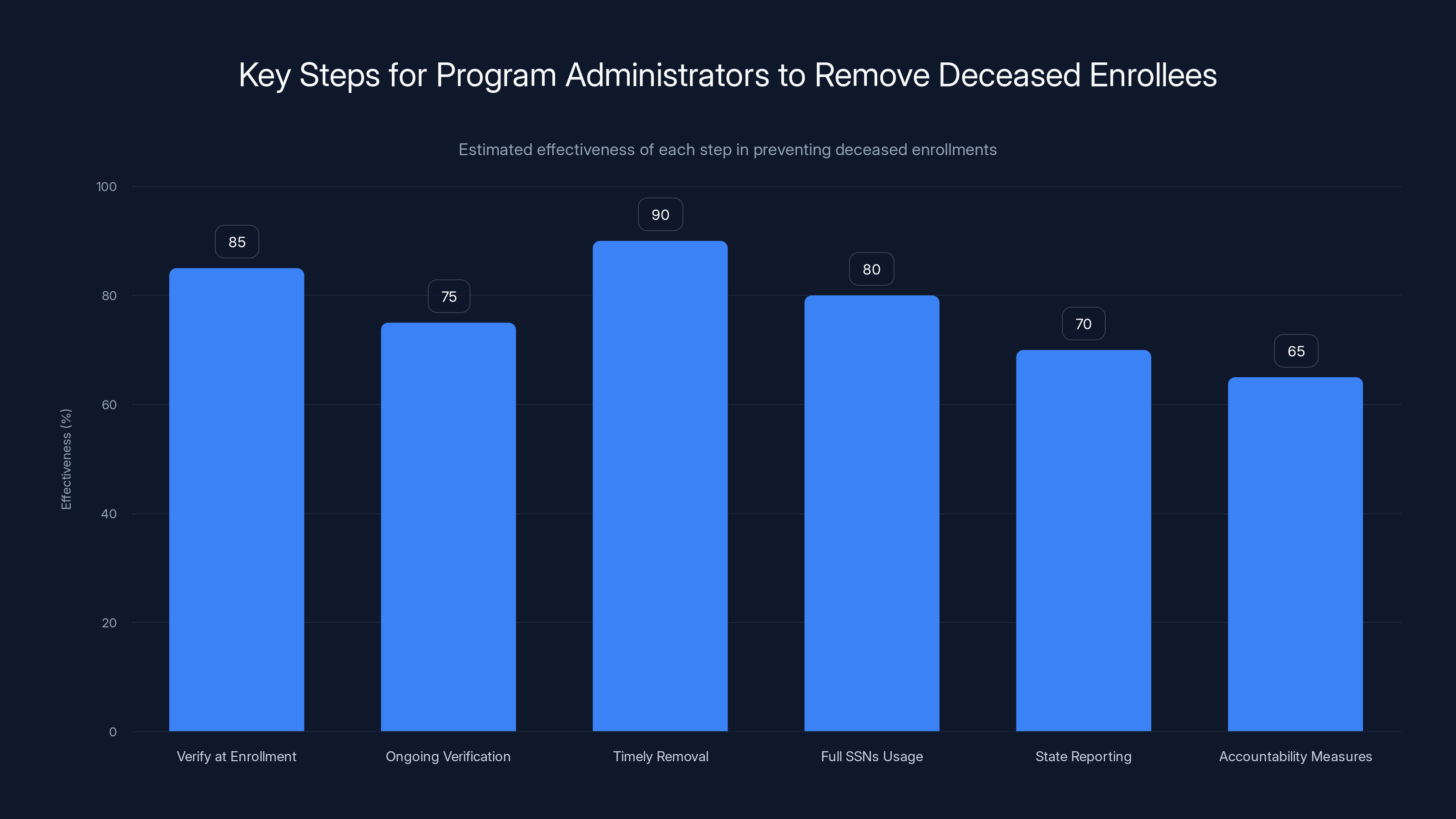

Estimated data shows that timely removal of deceased enrollees is the most effective step, with an estimated effectiveness of 90%. Verification at enrollment and using full SSNs are also crucial with high effectiveness.

Why This Fight Matters: The Precedent

Here's why you should care about FCC infighting over Lifeline verification, even if you don't use the program yourself.

This is about how federal benefit programs will be verified and governed going forward. If Carr's approach wins, the federal government will have more centralized control over eligibility verification for Lifeline and possibly other programs. That could mean faster fraud detection and fewer dead people collecting benefits. It could also mean more people who are actually eligible getting rejected because the federal system is too rigid.

If California's approach wins (or at least survives with modifications), it signals that states can have flexibility in running federal programs, even if that flexibility comes with some inefficiency and minor fraud. That's a different governance model.

The tension between federal and state control over benefit programs is fundamental to American federalism. This fight is just the latest round of it, and the outcome could set precedent for years.

Moreover, if Carr can win on Lifeline verification, he might push for similar changes to other benefit programs. Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, SNAP—all of them have the dead people problem. All of them would benefit from better verification systems. But those changes would be expensive and administratively complex.

The Path Forward: What Happens Next

Carr said the FCC will vote next month on the NPRM. That means public comment period, then potential rule changes. The timeline could be months or years, depending on legal challenges.

California will definitely challenge any rule that strips away its opt-out status entirely. The state will argue that federal overreach violates the Administrative Procedure Act and possibly the Constitution. This could end up in court.

But here's the political reality: Carr controls the FCC right now. He's the chair, and he has leverage. California can't stop him from proposing rules. It can challenge them, but that takes time, and meanwhile, the FCC could be issuing new guidance that tightens the screws.

What's likely to happen? Some middle ground. The FCC probably won't eliminate state opt-out authority entirely—that would be too aggressive and vulnerable to legal challenge. Instead, it might impose stricter standards that states have to meet to keep that authority. States would have to verify full SSNs, check against death records more frequently, and remove dead people within 30 days or lose their opt-out status.

California would have to comply or give up control. Other states would have to make the same choice. Over time, you'd probably see more states opting in to the federal system just because the state-level alternatives become too burdensome.

That's what Carr probably wants anyway. Not a big federal power grab that looks bad, but gradual centralization that happens because states find it easier to comply.

The Real Scandal: Why Nobody's Held Accountable

Here's what both Carr and California are dancing around: someone has to be personally, criminally responsible for enrolling dead people in Lifeline and billing the government.

We know that 16,000+ people were enrolled after they died. That's either incompetence on an massive scale or fraud. Either way, someone did something wrong. Either someone was lazy and didn't check if people were alive, or someone deliberately submitted false applications for dead people.

Yet the conversation is entirely about whether the verification system is good enough. Nobody's talking about investigating individual cases, pressing criminal charges against enrollment agents or teleco reps who submitted false claims, or holding employees personally accountable.

That's the real scandal. Both the FCC and California have the ability to investigate individual fraud cases and refer them for prosecution. Instead, they're arguing about systemic reform.

Maybe California officials don't want to prosecute enrollment agents because they're political appointees or family friends. Maybe the FCC doesn't want to appear vindictive by going after individual workers. Maybe the telecoms paying the enrollment agents have enough political clout that nobody wants to upset them.

But if you want to actually stop fraud, you need both systemic reform AND individual accountability. The fact that the debate is only about systems suggests that neither side wants to actually hold people's feet to the fire.

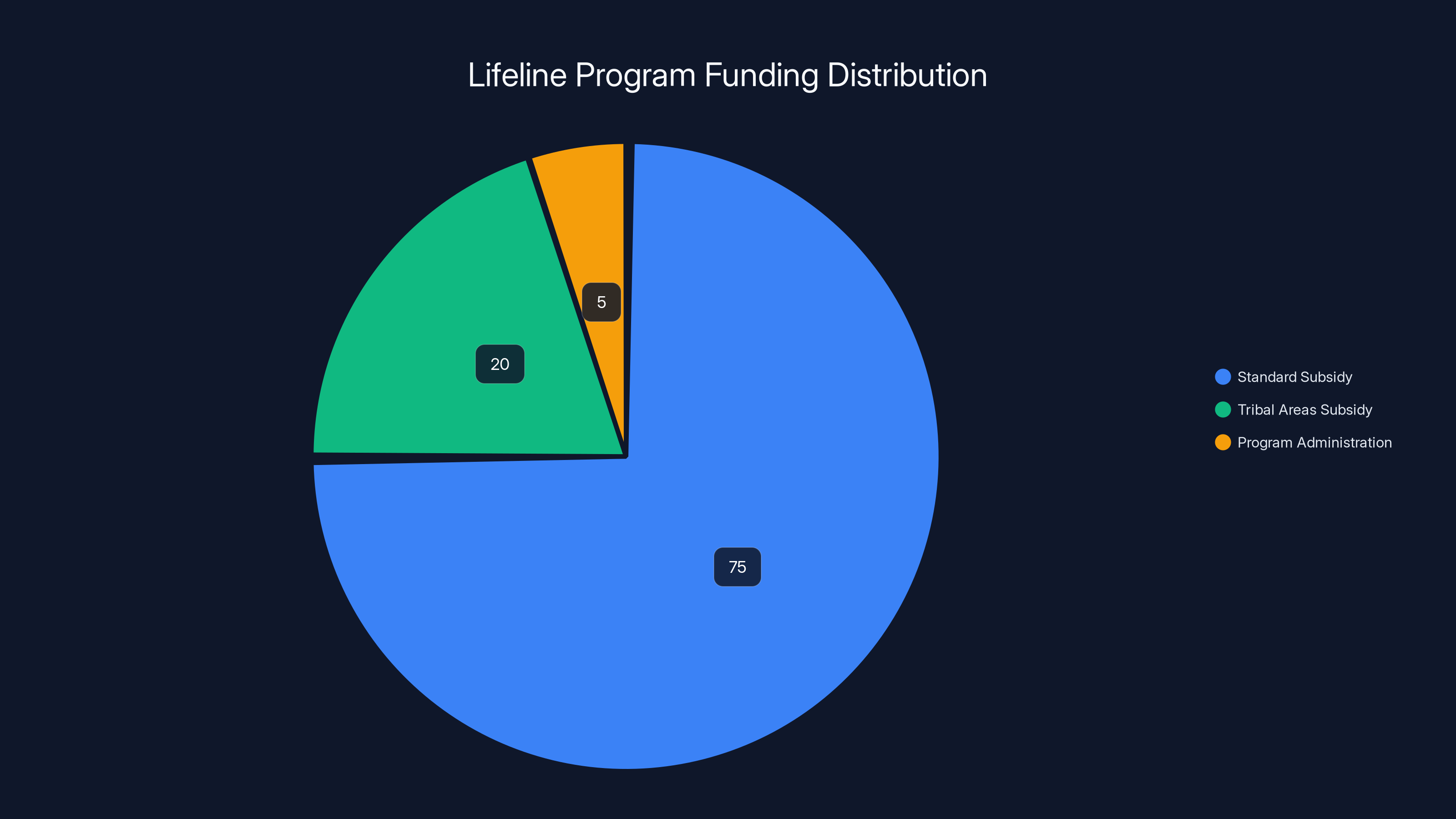

The Lifeline program allocates most of its funding to standard subsidies, with a significant portion dedicated to tribal areas. Estimated data.

Lessons for Program Administrators: How to Actually Fix This

If you're running a government benefit program and you don't want dead people on your rolls, here's what you actually need to do:

First, verify against death records at the point of enrollment. Before someone gets approved for Lifeline, check them against the Social Security Death Index, the state death registry, and any other available source. Yes, there will be lag time. But most people who are applying for benefits today aren't going to have died in the last 72 hours.

Second, do ongoing verification. Don't just check once at enrollment. Check again every 12 months, or every time someone re-certifies, or at least annually. This catches people who died after enrollment.

Third, set a time limit for removing dead people. Once SSA notifies you that someone is dead, you have 30 days to remove them from the program and stop billing. Not 3 months, not 4 months. 30 days. If it's taking longer, your processes are broken.

Fourth, use full Social Security numbers. Partial SSNs don't work reliably with verification systems. You need the full nine digits to cross-reference against death records and other databases.

Fifth, make states report this data to the federal government. Every state should have to report monthly how many people are removed due to death, how long the average removal takes, and what percentage of enrollees are in the system who are deceased. Transparency creates accountability.

Sixth, hold people responsible. If an enrollment agent submitted an application for a dead person, investigate. If someone at a telecom company billed for a dead person, charge them. Prosecution doesn't have to be the default response, but there should be serious consequences.

None of this is revolutionary. Other countries have figured it out. The VA knows how to verify that beneficiaries are alive. Social Security has systems for this (though they're not perfect). It's doable.

The Bigger Picture: Federal vs. State Governance

This fight is really about something deeper than Lifeline fraud. It's about the proper balance between federal and state control over benefit programs.

The federal government's argument: Federal money, federal rules. If you're spending taxpayer dollars, you have to follow federal standards. States can't be trusted to run their own show.

The states' argument: We know our populations better. We can administer programs more efficiently with state control. Federal systems are one-size-fits-all and don't account for local variation.

Both have a point. Federal systems ensure consistency and standardization, but they're inflexible. State systems allow customization, but they create variation and sometimes fraud.

The ideal is probably something in between: federal standards (like, "remove dead people within 30 days") with flexibility in how states meet those standards (whether they use NLAD, their own system, or something else).

But that requires mutual trust between federal and state authorities. And right now, Carr and California's officials clearly don't trust each other.

The Political Dimension: Why Now?

There's a timing question here that's worth asking: why is Carr pushing this now?

The Inspector General's report on Lifeline fraud came out weeks before Carr announced the NPRM. He could have pushed for rule changes any time in the past five years. But he waited until recently.

The answer probably involves Carr's political positioning. He's been a vocal critic of what he calls woke regulation and federal overreach. But that doesn't mean he opposes federal power in all cases. When he can frame federal power as cracking down on fraud and waste, it fits his political brand.

Also, California is a Democratic state, and Carr is a Republican appointee. There's an element of partisan scoring here, whether Carr acknowledges it or not. Pointing out that a blue state is mismanaging a federal program plays well with Republican voters.

Governor Newsom's response—saying this is political and nationwide, not just a California problem—is also partly correct and partly deflection. California does have the fraud problem concentrated there, but Newsom also knows that pushing back on federal encroachment plays well with his voters.

So this is policy and politics mixed together. The fraud is real, but the timing and intensity of the response is political.

International Comparisons: How Other Countries Handle This

Just for context, here's how some other developed countries handle benefit program verification:

Canada has a national benefit registry and requires full Social Insurance Numbers for all benefit programs. They do annual verification for most programs. Death records are checked against SSN holders automatically.

Australia has Centrelink, a centralized benefit system that uses full tax file numbers (equivalent to SSNs). They check deaths against state death registries quarterly.

UK has the Department for Work and Pensions, which centralizes benefit administration. They verify National Insurance numbers and check against death records frequently.

Germany uses a national registry and requires validation of all applicants. Regional authorities administer programs but use federal verification systems.

The pattern in developed countries is: centralized verification, full ID numbers required, frequent cross-checking against death records, rapid removal of deceased people from rolls. Nobody allows dead people to stay in the system for months or years.

So Carr's point that the federal system should be tighter isn't outlandish. It's basically pointing to how every other developed country does it. But the tradeoff is less flexibility for local administration and potentially higher barriers for hard-to-verify people.

The Subscriber Impact: What This Means for People Using Lifeline

If you're actually enrolled in Lifeline right now, how does this affect you?

In the short term, probably not much. Your service continues. Your subsidy keeps flowing. The FCC rule change will take months at minimum to implement.

But if stricter verification rules go into effect, they could affect you in a few ways:

First, re-certification might become harder. If you have to prove your identity more thoroughly and submit full SSNs, that's an extra barrier to staying enrolled.

Second, if the state's opt-out status gets revoked, the program might transition to a federal system. That could mean delays while the transition happens.

Third, if eligibility rules tighten, some people right at the income cutoff might no longer qualify. That's probably not most people, but it could be some.

Fourth, if Lifeline eligibility becomes harder to maintain, more people might drop out or not apply in the first place. That would reduce the program's reach.

For most people already enrolled, the change is probably manageable. For people trying to enroll new, or at the margins of eligibility, the change could matter more.

What the Numbers Actually Mean: The Translation

Let me put this in plain language, cutting through the political spin from both sides:

- Dead people are in California's Lifeline program. That's not debatable. It's in the data.

- Most of them were alive when they enrolled, then died while in the program. That's normal for a program that serves 3+ million Californians.

- Some of them were enrolled after they were already dead. That suggests either fraud or massive system failure. Probably both.

- The money involved is real, but not huge. $1 million per year isn't negligible, but it's also not enough to justify gutting a program that serves millions of people.

- California is right that this is a nationwide problem, not unique to California. But California is also worse at handling it than other states and federal programs.

- Carr is right that the federal government should improve verification systems. But he's probably overselling how much it will cost states or how much it will inconvenience eligible people.

The truth is somewhere in the middle: California should tighten its verification process and remove dead people faster. The FCC should give states the tools to do that without over-federalizing the entire program. Both things can be true.

The Future of Benefit Program Verification

Wherever this Lifeline fight ends up, it's going to influence how federal benefit programs handle verification for years to come.

The momentum seems to be toward more federal control and stricter verification requirements. That's not wrong—there's legitimate fraud to prevent. But the cost is inflexibility and potential exclusion of people who are hard to verify.

We'll probably see a gradual shift where more states opt into the federal NLAD system and fewer maintain independent verification. That centralizes control but also standardizes rules and reduces fraud.

We might also see more federal programs implementing automated death verification, where SSA notifies programs automatically when a beneficiary dies. That's actually a good development—it removes the administrative burden of manual verification.

But we're unlikely to see better accountability for individual cases of fraud unless both federal and state authorities decide to prioritize prosecution over just fixing systems. And that seems unlikely given the political incentives.

FAQ

What exactly is the Lifeline program, and who qualifies?

Lifeline is a federal subsidy that helps low-income Americans afford telecommunications services. It provides eligible households up to

How did dead people end up in California's Lifeline system for so long?

The Inspector General report found that 116,808 deceased subscribers received Lifeline benefits across three opt-out states between 2020-2025, with 81% (about 94,600 people) in California. About two-thirds of these cases involved people who were alive when enrolled and died while still receiving benefits, with their accounts continuing for an average of 4.4 months after death. The remaining one-third to one-half were enrolled after they were already deceased, suggesting systemic failures in death verification or outright fraud. California uses its own verification system instead of the federal National Lifeline Accountability Database (NLAD), which allowed for less oversight.

What is Brendan Carr proposing to fix this problem?

FCC Chair Brendan Carr has proposed a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) with several changes: requiring full Social Security numbers from applicants (instead of partial SSNs), implementing federal death verification through the Citizenship and Immigration Services' Systematic Alien Verification for Entitlements (SAVE) program, eliminating state opt-out authority so all states use the federal NLAD system instead of their own verification processes, and other changes to ensure benefits go "only to living and lawful Americans." The FCC voted to advance these proposals with a public comment period to follow.

Why does California argue this isn't actually a fraud problem?

California's Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) argues that while dead people receiving benefits is unfortunate, it reflects normal administrative lag rather than systematic fraud. They point out that the Inspector General's own report acknowledges that the vast majority of the 116,808 deceased recipients were alive and eligible when they enrolled, and that deaths followed natural demographics of a 9-million-person program. The CPUC argues that removing someone from the system takes time as death records move through bureaucracy from vital statistics offices to state programs to providers. They also point out that similar issues exist in Texas and Oregon (also opt-out states) and that singling out California is politically motivated.

Is 1 billion program?

The numbers matter here.

What would stricter verification rules mean for people already enrolled in Lifeline?

If FCC rule changes take effect, current Lifeline recipients might experience more rigorous re-certification processes, potentially requiring full Social Security numbers and federal verification of eligibility. If California loses its opt-out status (which it partially has already), the program might transition to the federal NLAD system, potentially causing temporary delays or administrative friction. For most people at secure income levels, the impact would likely be minimal. However, for people at the margins of eligibility or those with documentation challenges (immigrants, homeless individuals, or people without readily available SSNs), stricter requirements could create barriers to enrollment or continued participation.

Why is the FCC involved in this if it's a state program?

Lifeline is a federal program administered through the FCC's Universal Service Fund. While states have some latitude in how they verify eligibility, they're ultimately accountable to federal rules and federal money. The FCC has statutory authority to set eligibility standards, verify program compliance, and impose penalties for violations. When the FCC discovered that California (and other opt-out states) were not properly managing federal dollars, it took action first by revoking California's opt-out status in November 2025, and now by proposing nationwide rule changes. The FCC's authority here is rooted in federal telecommunications law and appropriations.

How long does it typically take for someone to be removed from Lifeline after they die?

According to the Inspector General report, providers continued billing for deceased subscribers for an average of 3.4 months after death. In some cases, billing continued for up to 54 months (4.5 years). This lag time occurs because death records have to be reported from local vital statistics offices, processed by state authorities, communicated to providers, and then removed from billing systems. The report indicates that while some lag is inevitable in any large program, months-long delays in California suggest inadequate death verification procedures and potentially non-functional account removal processes.

Could other federal benefit programs have the same dead people problem?

Yes, absolutely. Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, SNAP, and Veterans benefits all face similar issues with deceased beneficiaries remaining on the rolls. The federal government collectively makes improper overpayments to deceased individuals in the billions of dollars annually, though exact figures are difficult to pin down because agencies don't consistently report this data. Carr's push for stricter Lifeline verification could create a model that other agencies and Congress might push to implement across all federal benefit programs. Several developed countries (Canada, Australia, UK, Germany) handle this through centralized systems with automated death notification and verification, which prevents most improper payments within weeks of death notification.

What happens if the FCC's rule changes go into effect?

If approved after the comment period, the new rules would likely be implemented gradually. States would be required to meet stricter verification standards or lose their opt-out authority and be forced to use the federal NLAD system. California, having already lost its opt-out status, would transition fully to federal verification. The FCC could issue guidance on implementation timelines, likely giving states months to comply. Legal challenges from California and potentially other states are expected, which could delay implementation. The practical effect would be tighter eligibility verification, faster removal of deceased people from rolls, and more federal oversight of state-administered programs.

Conclusion: The Bigger Issue Than Fraud

The fight between Brendan Carr and California's officials over dead people in the Lifeline program is superficially about fraud prevention, but it's really about something bigger: how America's federal system balances local autonomy with centralized control.

Carr is arguing for standardization, federal verification systems, and zero tolerance for improper payments. That approach prevents fraud and ensures consistent standards nationwide. But it also takes power away from states and potentially creates barriers for people who are hard to verify.

California is arguing for state flexibility, understanding that administering large programs is messy and that lag time is inevitable. That approach respects federalism and acknowledges complexity. But it also creates vulnerability to fraud and allows standards to vary wildly from state to state.

The dead people in Lifeline are real. The problem is real. But it's also a symptom of a larger governance question that we haven't actually resolved as a country: Who should run federal benefit programs, the feds or the states?

For Lifeline specifically, the outcome will probably be some middle ground. California will have to meet stricter standards or lose control of the program. Other states will face similar pressure. The federal system will gradually centralize, not because Carr forced it, but because states will find it easier to comply than to maintain their own systems.

But the real work—identifying individual fraud, prosecuting bad actors, and holding people accountable—won't happen unless both federal and state authorities decide that's a priority. And right now, it seems like neither side wants to go there. They'd rather argue about systems and blame each other.

So yes, Lifeline has a dead people problem. It should be fixed. But fixing the systemic issues is only half the solution. The other half is accountability for the individual people who made it happen. Until both sides are willing to go there, this will just be another round of federal-state fighting without real consequences for fraud.

The coming months will show whether the FCC's rule changes actually improve the program or just shift the problem around. My guess is they'll help, but they won't be the magic bullet either side is claiming. Fraud and bureaucratic failure are stubborn problems in large government programs. Sometimes you fix the system. Sometimes you prosecute people. Usually you have to do both.

Key Takeaways

- FCC identified 116,808 deceased subscribers receiving Lifeline benefits across three opt-out states, with 81% of cases in California, over five years.

- Approximately $4.9 million in improper payments (0.1% of program spending) went to deceased beneficiaries, averaging 3.4 months of continued billing after death.

- About 16,774 confirmed cases (potentially 39,362 if uncertain cases included) involved people enrolled AFTER they were already deceased, suggesting systemic fraud or massive process failures.

- FCC Chair Brendan Carr proposes stricter nationwide verification rules including full SSN requirements and federal death record checking to eliminate state opt-out authority.

- California argues the problem reflects normal administrative lag in a 9-million-person program and that similar issues exist nationwide, not just in California.

- Democratic FCC Commissioner Anna Gomez warns that stricter eligibility rules could harm legitimate beneficiaries by creating barriers for people harder to verify.

- California already lost its opt-out status in November 2025 and will transition to federal NLAD verification, setting precedent for other states.

- Lifeline's improper payment rate of 0.1% is significantly lower than Medicare fraud estimates (2-10%) and federal program averages (5%), though not negligible.

Related Articles

- SpaceX's Starlink Broadband Grant Demands: What States Need to Know [2025]

- Silicon Valley's Political Power: Why Tech Leaders Must Act [2025]

- Warren Demands OpenAI Bailout Guarantee: What's Really at Stake [2025]

- Face Recognition Surveillance: How ICE Deploys Facial ID Technology [2025]

- FCC Equal-Time Rule & Late-Night Talk Shows Explained [2025]

- DOGE Social Security Data Misuse: What Happened & Why It Matters [2025]

![FCC Lifeline Fraud Battle: California's Dead Subscribers Problem [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/fcc-lifeline-fraud-battle-california-s-dead-subscribers-prob/image-1-1769801833213.jpg)