Silicon Valley's Political Power: Why Tech Leaders Must Act [2025]

There's a moment every powerful person faces. It's quiet. Nobody's watching. And they have to decide whether their principles are worth more than their comfort.

For Silicon Valley CEOs, that moment keeps getting louder.

When Reid Hoffman, one of tech's most respected voices and co-founder of LinkedIn, published his urgent call to action, he wasn't mincing words. The tech industry's biggest leaders were doing something worse than opposing government actions—they were legitimizing them through selective silence and strategic distance.

This isn't a story about partisan politics. It's a story about power, responsibility, and the gap between what tech leaders say and what they actually do.

Let me explain why this moment matters more than you probably think, and what it reveals about how Silicon Valley actually works.

TL; DR

- The Contradiction: Tech CEOs condemn specific government actions but distance themselves from the administration, hoping to stay neutral

- Hoffman's Challenge: Real neutrality doesn't exist—silence and inaction are themselves choices that enable harmful policies

- The Business Reality: Tech companies depend heavily on federal contracts, regulation, and policy decisions, making their political passivity actually a liability

- The Worker Revolt: Tech employees increasingly demand their companies take ethical stands, not just internal memos

- The Real Question: Can Silicon Valley wield its genuine power responsibly, or will it continue choosing profits over principles?

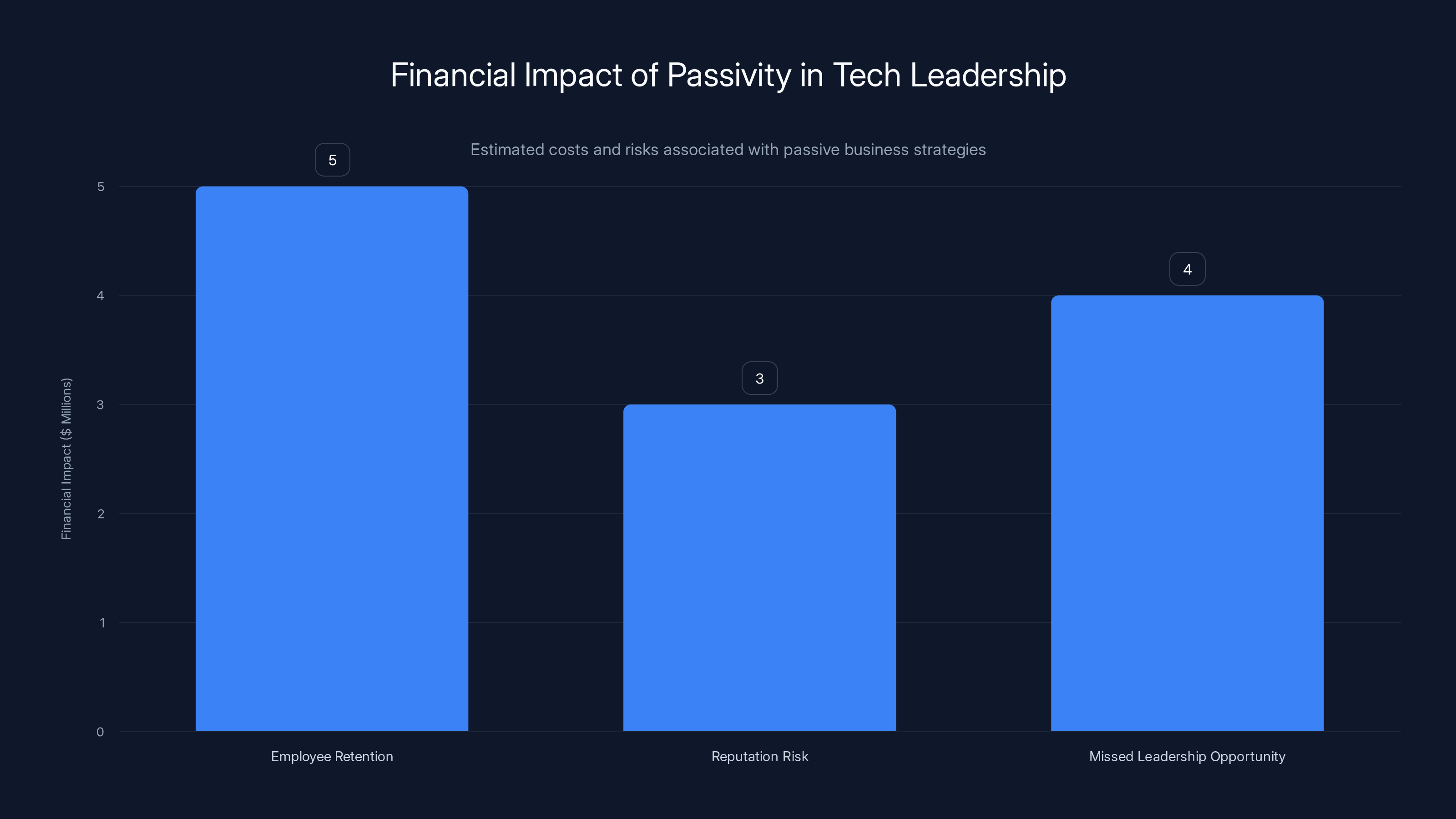

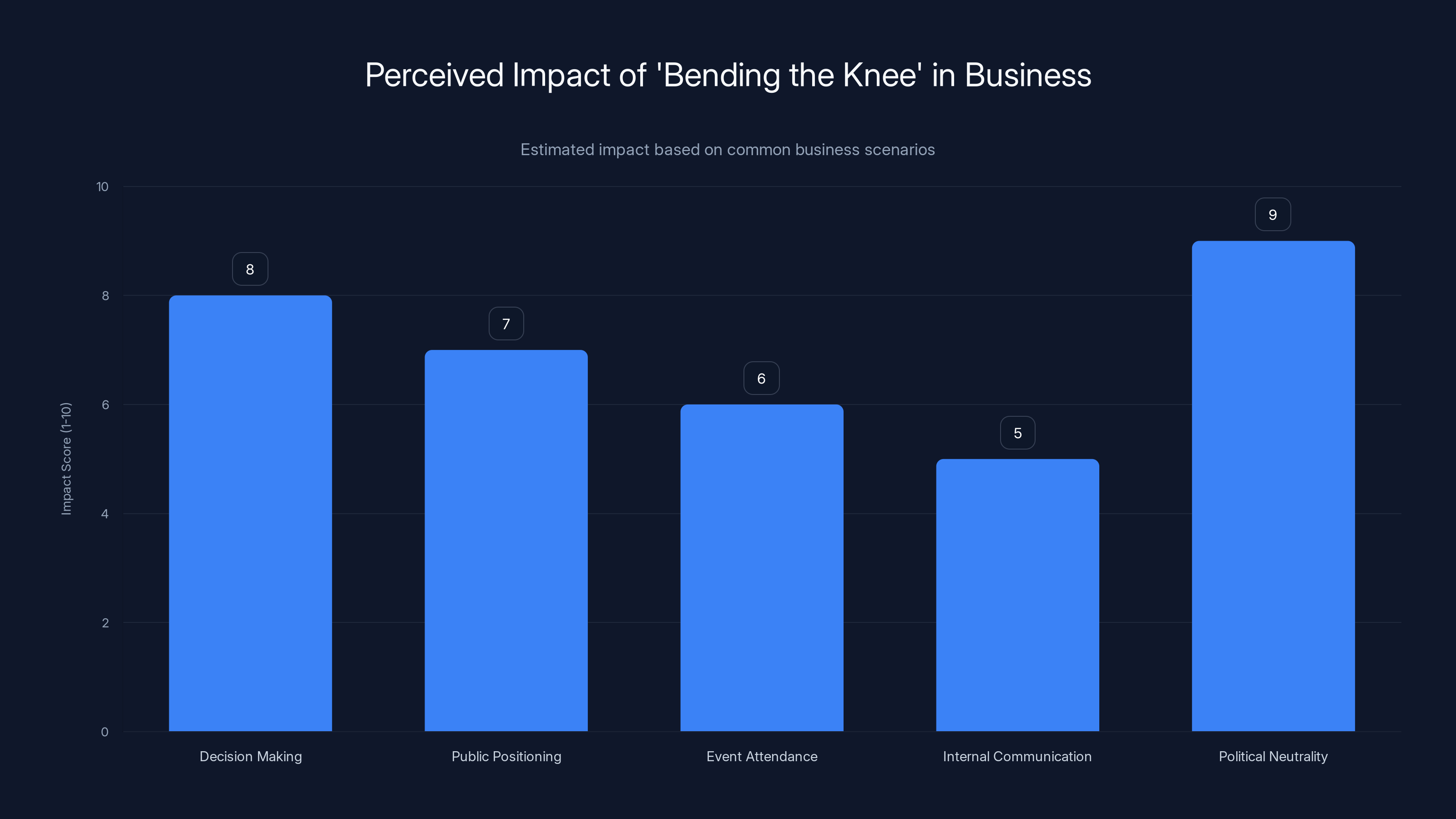

Estimated data shows that passivity in tech leadership can lead to significant financial impacts, particularly in employee retention and missed leadership opportunities.

The Gap Between Words and Actions: When Condemnation Isn't Enough

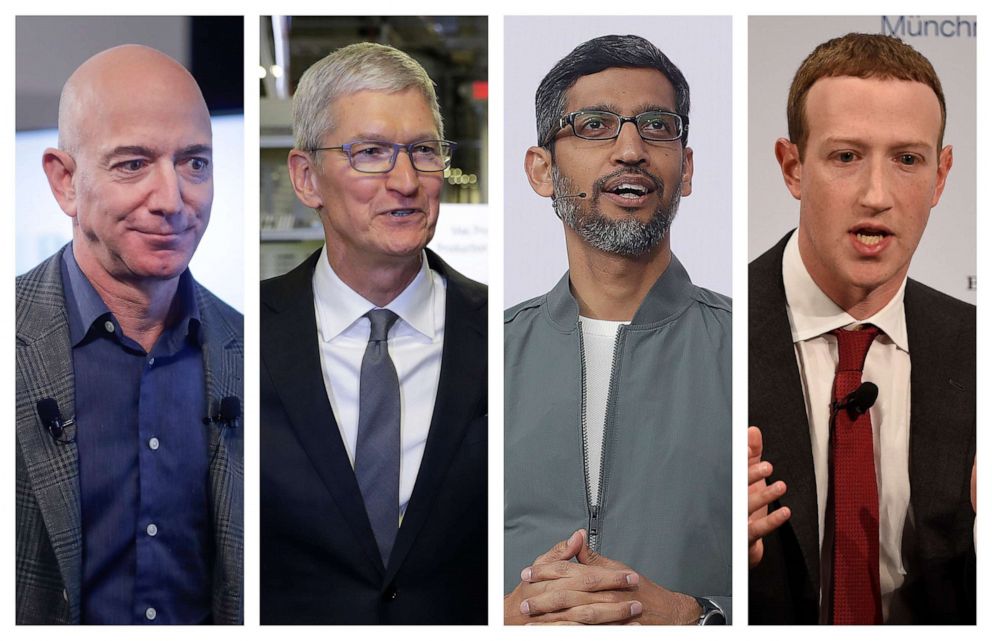

Let's start with what actually happened. In early 2025, Border Patrol agents killed two American citizens. The incidents sparked rare public criticism from some of tech's most powerful figures.

OpenAI CEO Sam Altman expressed concern. Apple CEO Tim Cook called the situation "heartbreaking." Even Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei voiced concern through internal channels.

But here's where it gets messy.

They were careful. Cautious. They condemned the specific incidents while maintaining strategic distance from the broader administration. Some used leaked internal memos rather than public statements. Others paired their criticism with other actions that seemed to undermine it.

Take Tim Cook. Hours after the ICE shooting, he attended an exclusive screening of Melania Trump's documentary. The timing alone sent a message: business as usual.

This is the pattern Hoffman identified. Tech leaders aren't being neutral. They're performing neutrality while their actions tell a different story.

Neutrality, Hoffman argues in his X posts and San Francisco Standard opinion column, is actually a choice. When you have power—real, economic, political power—and you choose not to use it, that's not neutrality. That's complicity.

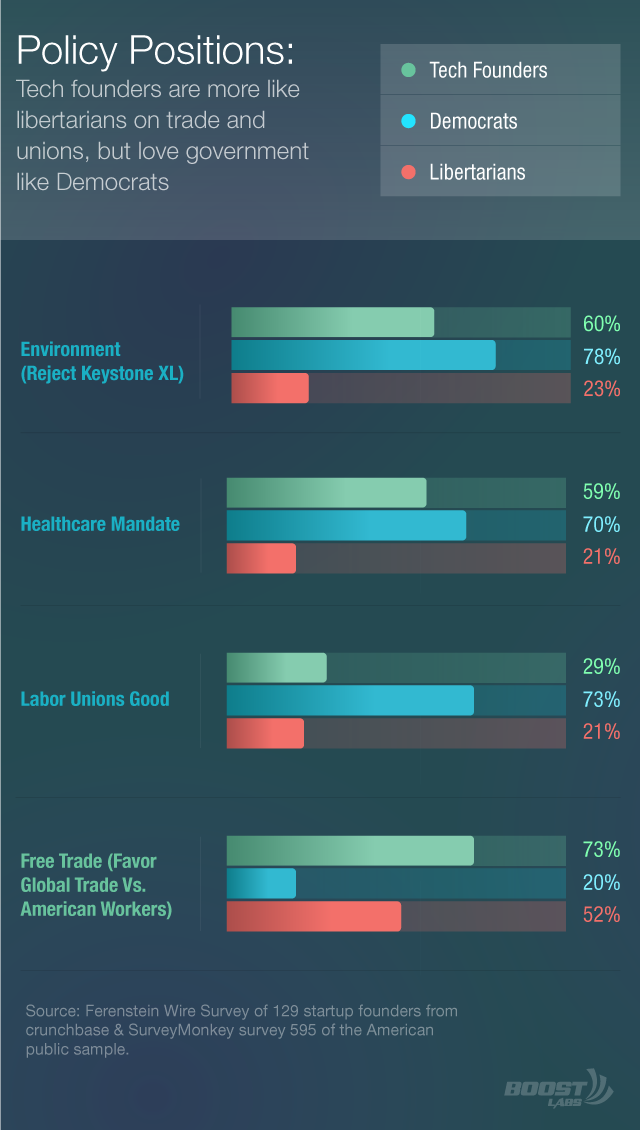

Understanding Silicon Valley's Real Political Power

Here's what most people miss: Silicon Valley's power isn't theoretical. It's structural. It's built into how modern government actually functions.

Think about what tech companies control:

- Regulation: Tech companies don't just face government regulation. They shape it through lobbying, expertise, and influence. When the federal government wants to understand AI policy, they call Sam Altman, not a congressman.

- Infrastructure: The U.S. government runs on tech infrastructure. Cloud computing, data systems, communication platforms—they're not optional. They're foundational. That gives tech companies leverage most industries can't even dream of.

- Talent and Expertise: Want to build an AI system? You need people who work at OpenAI, Google, Meta. The government needs them more than they need any single government contract.

- Public Trust: When Elon Musk says something about AI, millions listen. When Sam Altman testifies before Congress, people pay attention. That's cultural power.

- Economic Impact: Tech companies employ hundreds of thousands of people. A single large tech company can reshape local economies. That's political power.

This isn't subtle. This isn't hidden. This is how the modern U.S. economy actually works.

But here's the problem: Silicon Valley leadership has convinced itself that having power and using power are two different things. That they can be powerful but not activists. That they can influence everything but take responsibility for nothing.

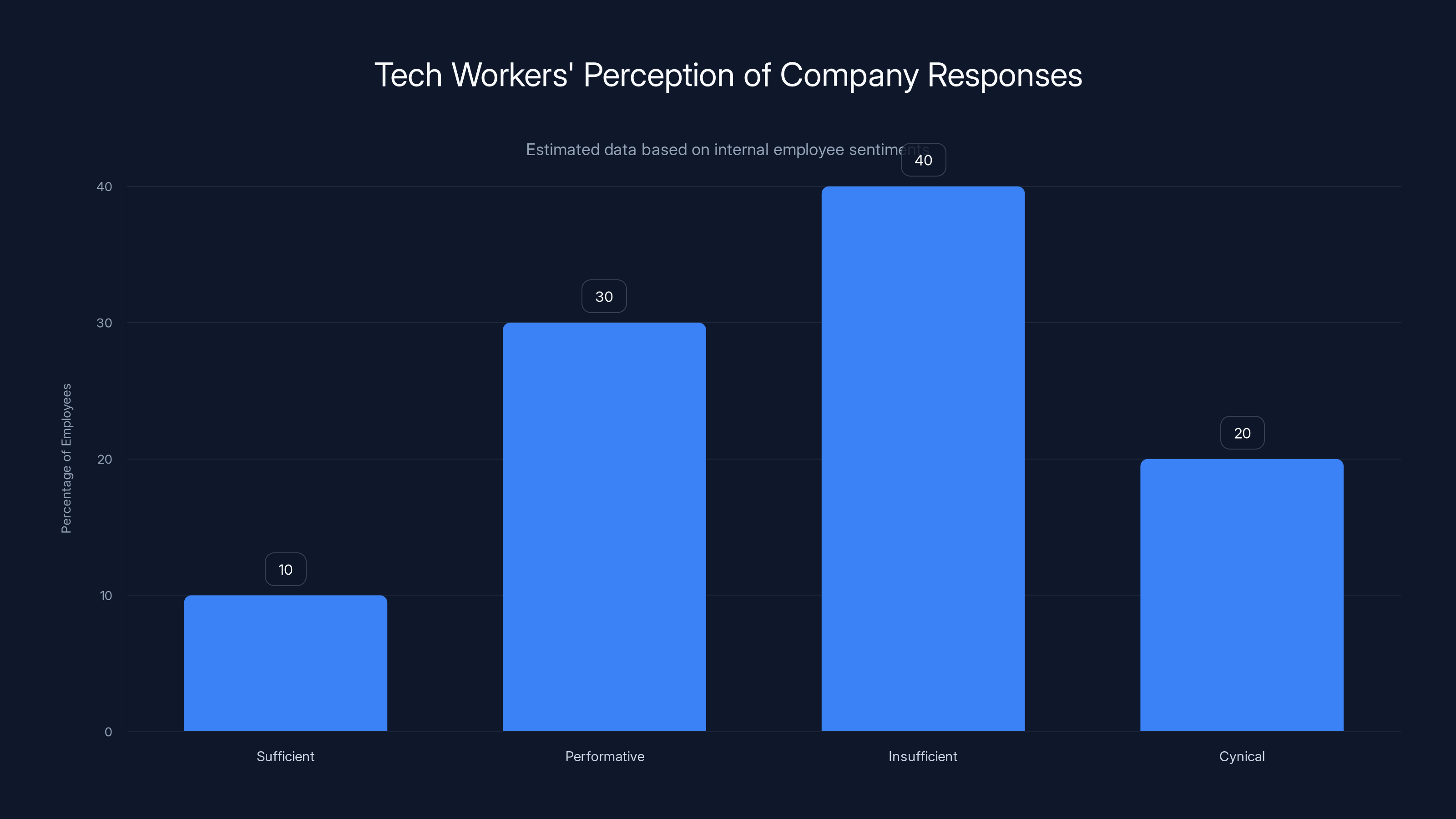

Estimated data suggests a significant portion of tech workers view company responses as insufficient or performative, indicating a potential risk to employee satisfaction and retention.

Why Tech CEOs Are Walking a Tightrope

Okay, so why don't tech leaders just speak up? Why the careful distance? Why the strategic silence?

The answer is actually understandable, even if it's not defensible.

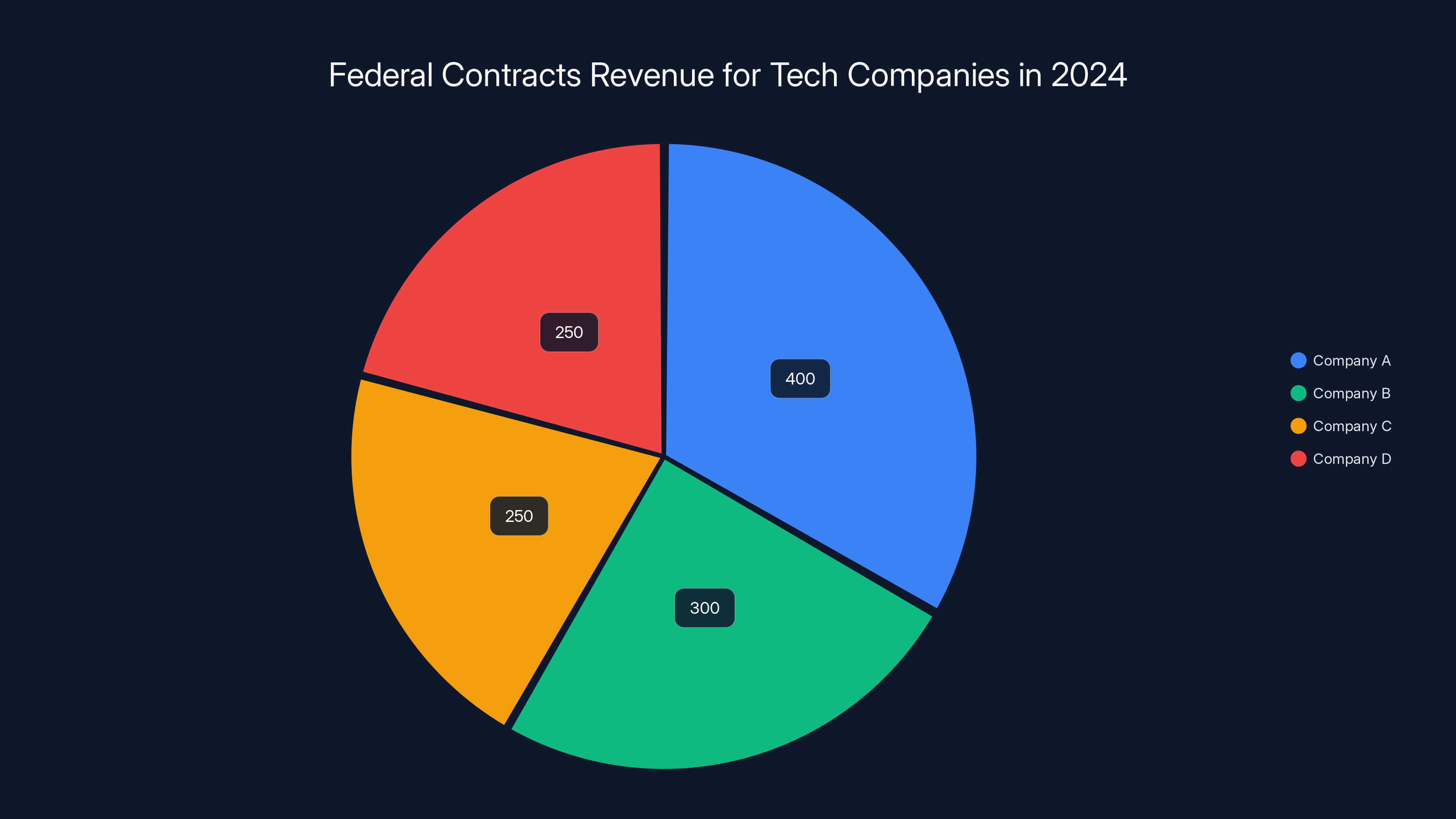

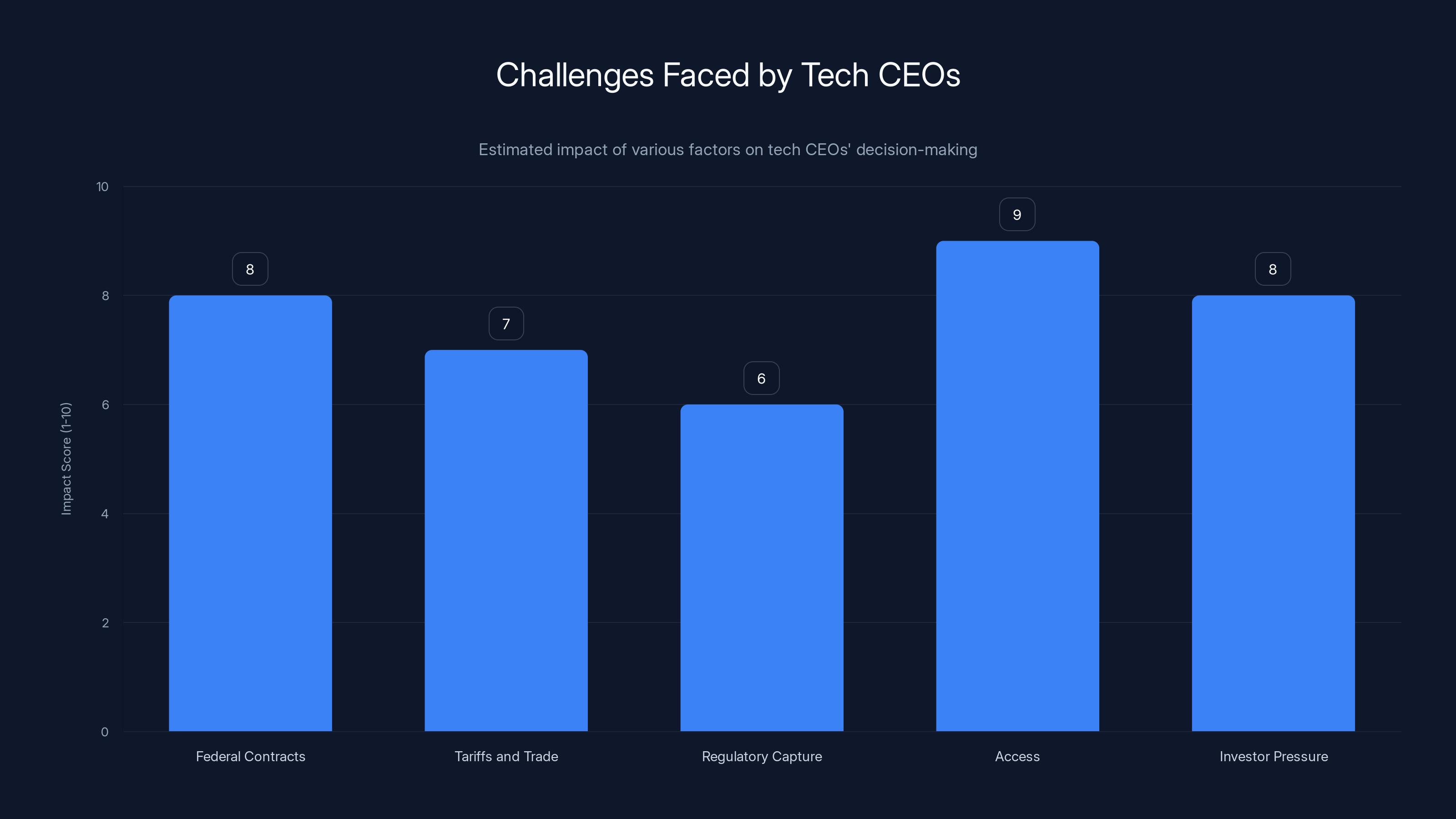

Federal Contracts: Major tech companies depend on government contracts. Amazon Web Services handles sensitive government data. Google Cloud competes for defense contracts. OpenAI itself has AI-related government work in the pipeline. Antagonizing the administration could cost billions.

Tariffs and Trade: Tech companies are vulnerable to tariff threats. The administration has already threatened tariffs on multiple fronts. A CEO who speaks too loudly could wake up to new import duties on crucial components.

Regulatory Capture: Here's the irony. Tech companies want favorable regulation, but they also want the government to not actually regulate them too aggressively. Speaking out against the administration could accelerate regulation they don't want.

Access: Political access is currency in Washington. A CEO who's controversial loses access. No meetings. No calls returned. No influence on policy direction. That's a real cost.

Investor Pressure: Shareholders care about stock price. Political controversy can tank stock price. Boards will push back against executives who create risk.

All of this is rational from a business perspective. From a human perspective, it looks like cowardice dressed up as pragmatism.

Hoffman's point is exactly this: you're not facing an impossible choice. You're facing a comfortable choice. The discomfort you feel isn't evidence you should stay silent. It's evidence you should act.

The Employee Revolt: When Workers Demand More From Leaders

There's something happening inside tech companies that executives are underestimating.

Thousands of tech workers have signed a petition demanding their companies:

- Call the White House and demand ICE leave U.S. cities

- Cancel all contracts with ICE

- Publicly speak out against government violence

This isn't a fringe position. This is coming from inside Google, Meta, Apple, OpenAI. From engineers, designers, product managers. From the talent that actually makes these companies valuable.

Why does this matter?

Because tech talent is mobile. Expensive. Hard to replace. If you're a brilliant engineer at Google and your company is silent on issues you care about, you can go work at 15 other companies tomorrow. Your skills are valuable everywhere.

This creates real pressure on leadership. Not just moral pressure. Economic pressure. Retention pressure.

And here's what's interesting: some tech leaders are slowly recognizing this. The internal memos from OpenAI, Apple, and Anthropic weren't leaked because the leaders wanted to hide their concerns. They were leaked because employees wanted public action, and when they didn't get it, they made the memos public.

That's employees overruling their CEOs. That's a problem for executive credibility.

The Elon Musk and Keith Rabois Exception: When Tech Leaders Go All In

Of course, there's another part of this story.

Some tech leaders are making the opposite choice entirely.

Elon Musk has gone all-in on political alignment with the Trump administration. He's not walking a tightrope. He's taken a clear position and is fully invested in that relationship.

Keith Rabois of Khosla Ventures has been vocal in supporting the administration's direction.

What's interesting is that they've made a choice. A clear, consistent choice. They're not trying to be neutral. They're not pretending. They're aligned.

You can disagree with that choice, but at least it's honest.

That's actually Hoffman's broader point. The dishonesty is worse than the alignment. If you support the administration, say so. If you oppose specific policies, say so. But don't pretend you're neutral while your actions tell a different story.

That's what destroys credibility.

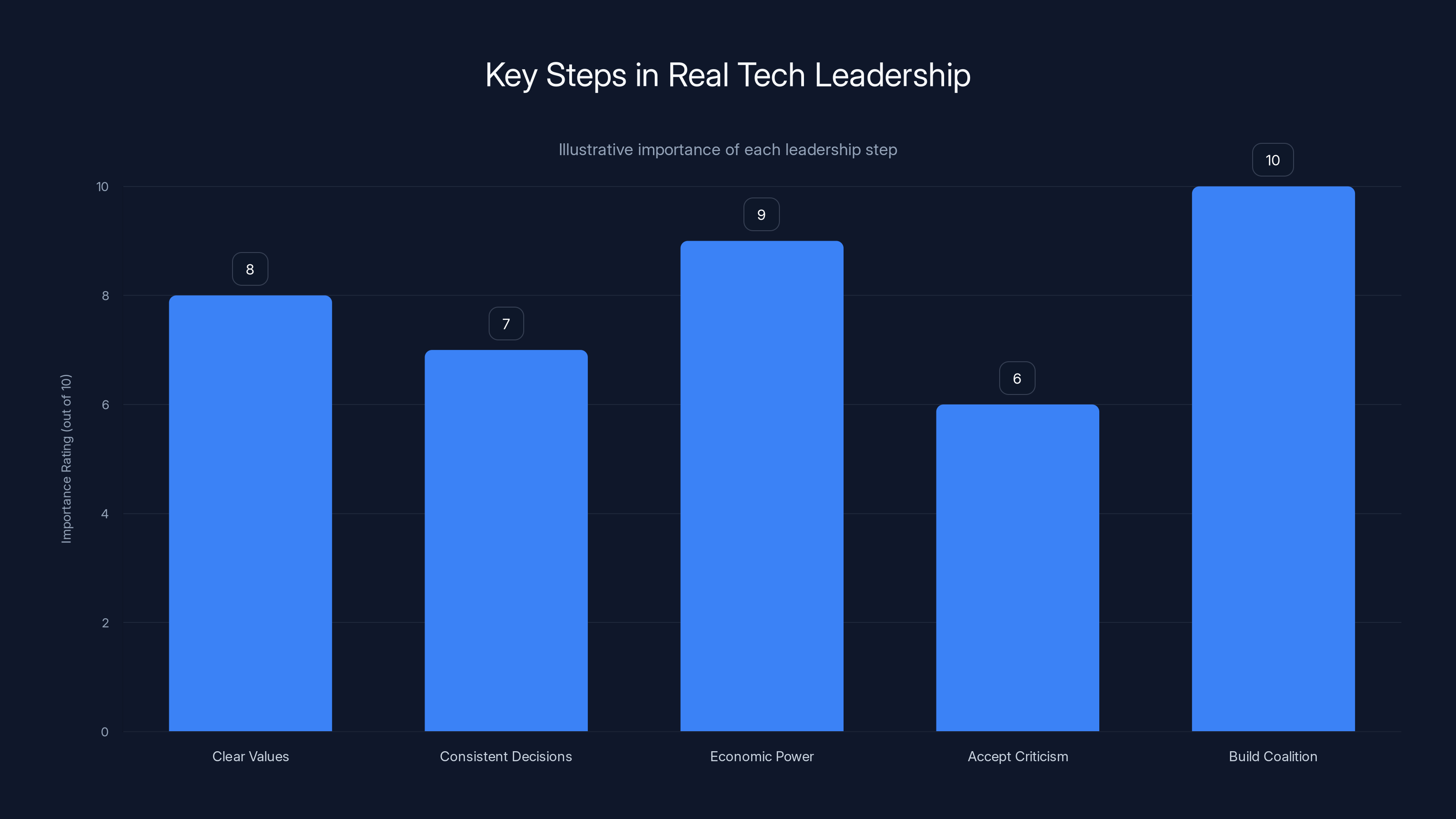

Building coalitions is rated as the most crucial step in achieving real tech leadership, emphasizing the power of collective action. Estimated data.

What "Bending the Knee" Actually Means

Hoffman's phrase "bending the knee" has generated criticism. Some say it's melodramatic. Others say it's overreaching.

But think about what it actually describes:

- Making business decisions based on political fear rather than business logic

- Avoiding public positions on issues your employees care about

- Attending events that send political signals counter to your stated values

- Using internal memos instead of public statements to avoid controversy

- Positioning yourself as politically neutral when that's not actually possible

That's not leadership. That's appeasement.

Here's the thing about appeasement: it never works. History is full of powerful people who tried to stay on the good side of stronger forces by going along. It doesn't prevent pressure. It invites more pressure.

Someone makes a demand. You comply. Now they know you'll comply. They make a bigger demand. And so on.

That's the dynamic Hoffman is warning about.

If tech leaders want to maintain real independence and real power, they can't do it by appeasement. They have to do it by setting clear boundaries. Being clear about their values. Being willing to accept consequences for those values.

That's what actually preserves power. Not bending the knee. Standing firm.

The Business Case Against Passivity

Here's something that doesn't get discussed enough: passivity is actually bad business.

Let's think about this from a pure business strategy perspective, setting aside all moral arguments for a moment.

If you're a tech leader and you're staying quiet because you don't want to antagonize the government, you're making an economic miscalculation. Here's why:

Mistake 1: Assuming the Government Needs You Less Than You Need It

This is backwards. The government needs tech companies for national security, infrastructure, economic growth. A tech CEO can survive without a government contract. The government can't function without tech infrastructure. The leverage is more balanced than tech leaders think.

Mistake 2: Confusing Political Opinion With Business Criticism

You can be neutral on whether someone's administration is good while being critical about specific policies. "Border Patrol violence is wrong" isn't a political opinion. It's a factual statement. Allowing violence isn't a policy disagreement. It's a human rights issue. You can state facts without being partisan.

Mistake 3: Underestimating Employee Retention Costs

Silicon Valley talent is expensive. Replacing a senior engineer costs $500K+ in recruiting and training. Losing 5% of your workforce costs millions. If your stance on values is losing talent, that's not a moral problem. It's a financial problem.

Mistake 4: Ignoring Reputation Risk

If you're seen as complicit in government overreach, customers eventually notice. Investors eventually notice. Partners eventually notice. The credibility damage from looking powerless is real.

Mistake 5: Missing the Opportunity for Principled Leadership

This is the biggest one. Right now, there's a gap in the market. There's no major tech leader who's clearly standing for principles while maintaining business success. That's an opportunity. The first CEO to clearly position themselves as principled while remaining pragmatic will have enormous brand value, employee loyalty, and customer goodwill.

The Specific Critique: Tim Cook and Apple

Let's use Tim Cook as a specific example because he illustrates Hoffman's point perfectly.

Cook is known for taking ethical stances. Apple's privacy focus. Sustainability commitments. Diversity initiatives. These are real. Cook believes in them.

So when the Border Patrol incidents happened, Cook issued an internal memo calling them "heartbreaking" and urging "de-escalation."

So far so good. That's the bare minimum of leadership.

But then, hours later, he attended an exclusive screening of the First Lady's documentary.

What message does that send?

That attending the First Lady's event is more important than his stated values? That his ethics have an expiration date of a few hours? That he's fine working with the administration even when they do things he finds heartbreaking?

It's incoherent.

And that incoherence is exactly what Hoffman is identifying. Cook has the power to be clear. He's choosing not to use it. Instead, he's trying to have it both ways, and doing neither effectively.

If Cook wants to work with the Trump administration, that's a valid business choice. But then don't issue memos about being heartbroken. Be clear about the decision.

If Cook wants to oppose the Border Patrol incidents, then don't attend events that signal alignment with the administration. Be clear about the values.

What you can't do, sustainably, is both. And that's the actual problem.

In 2024, tech companies received significant federal contracts, with Company A leading at an estimated $400 million. Estimated data.

Vinod Khosla's Different Approach: When VC Goes Harder

On the flip side, look at Vinod Khosla of Khosla Ventures.

Khosla has been the most vocally critical tech voice on the government response, characterizing the White House and administration as "a conscious-less administration."

That's strong language. Unambiguous. Clear.

Now, Khosla's a venture capitalist, not a CEO of a company that depends on federal contracts. That gives him more freedom. But it also means his criticism has real weight because it comes from a position of less dependence.

What's interesting about Khosla's position is that it demonstrates you can be vocal and still be taken seriously in business. His firm hasn't lost government relationships because he's been critical. If anything, it's strengthened his position by making clear where he stands.

The contrast with other tech leaders is instructive. Khosla chose clarity. Others chose ambiguity. Guess who's more credible?

The Broader Silicon Valley Culture Problem

This isn't really about any individual CEO. It's about a culture problem in Silicon Valley.

There's a narrative that tech leaders are these bold, visionary figures who challenge the status quo. They disrupt industries. They change the world. They push boundaries.

Except, apparently, when doing so would be inconvenient.

When it comes to actual power and actually using it, suddenly they're cautious. Careful. They're worried about relationships. They're thinking about contracts. They're hedging positions.

It's the same contradiction you see with many billionaires. They'll disrupt every industry except their own interests. They'll challenge authority except when it affects them directly.

Hoffman is calling out that contradiction. And he's right to.

If tech leaders want to claim they're visionary and courageous, they have to actually be those things in moments that matter. Not just in safe moments. Not just in moments that make good marketing copy.

In moments where standing up costs something.

That's when courage is actually courage, not just positioning.

What Real Tech Leadership Would Look Like

Let's imagine what Hoffman's vision of actual tech leadership would look like:

Step 1: Be Clear About Values

Publicly articulate what your company stands for. Not in marketing materials. In actual, specific terms. "We believe in X. We oppose Y." Clear enough that employees understand. Clear enough that customers understand.

Step 2: Make Business Decisions Consistent With Those Values

If you oppose government violence, don't attend events with officials who enable it. If you support rule of law, don't participate in arrangements that undermine it. If you believe in transparency, don't use internal memos to hide positions.

Step 3: Use Economic Power Explicitly

Tell the government: "We want to work with you. We want good relationships. But here are our red lines. Cross them and we can't be partners."

This isn't threats. It's clarity. Business deals this way all the time. Why not government relationships?

Step 4: Accept That Some People Won't Like It

Real leadership means accepting criticism. Accepting that some constituencies will be unhappy. Accepting that power has a cost.

Step 5: Build Coalition

If you're the only tech leader taking a stand, it's risky. But if five CEOs stand together? If ten? If it becomes the norm in tech leadership? Suddenly the risk is distributed.

That's what Hoffman is calling for. Not individual heroics. Coalition. Unity. Collective action.

Tech CEOs face significant challenges, with political access and federal contracts being the most impactful. Estimated data.

The Employee Perspective: Why This Matters Inside Companies

Let's zoom in on what this actually feels like for tech workers.

Imagine you work at Google. You care about human rights. You care about ethics. That's partly why you work at Google—the company has a stated mission around doing good.

Then something terrible happens. Government agents kill people unjustly.

You expect your company to respond. To make a statement. To take a stand.

Instead, you get a leaked internal memo from leadership that's vague, careful, and mostly about protecting the company.

How does that feel?

It feels like betrayal. Not because the memo isn't sympathetic. But because it's insufficiently bold. It's protective rather than principled.

Now multiply that feeling across hundreds of thousands of tech workers. They're not getting what they need from leadership: clarity. Courage. Commitment.

They're getting careful language instead.

This is actually eroding tech company cultures. It's making employees cynical about leadership. It's making them question whether the companies really believe what they say they believe.

And cynical employees are expensive. They're less productive. They're more likely to leave. They're harder to recruit for.

So from a pure business perspective, the lack of clear leadership is already costly. Hoffman's just pointing out that the cost is higher than executives realize.

Can Tech Companies Actually Change This?

Here's the hard question: can the culture actually shift?

There are reasons to be skeptical.

First, the incentives are real. Government contracts are billions of dollars. Tariffs matter. Regulation matters. The financial incentives to stay quiet are enormous.

Second, the precedent is set. If you're Google and you've stayed quiet on X issue, it's now much harder to speak up on the next one without looking inconsistent. The first silence creates a trap.

Third, boards and shareholders will resist. They'll see political activism as risk. They'll prefer the cautious approach. It takes a genuinely visionary board to support bold leadership on controversial issues.

But there are also reasons for optimism.

Employee pressure is real. Younger workers especially are less willing to work for companies they see as complicit in harm. Over time, this becomes a retention issue that shows up in financial statements.

Reputational advantage is real. The first major tech company to take a genuine principled stand while remaining pragmatic will have massive brand value. That's economically valuable.

Coalition effects are powerful. If it becomes normal for tech leaders to push back, the risk for any individual leader drops dramatically.

And here's the thing: some tech leaders actually do believe this stuff. They're not all cynical. They're just trapped by the infrastructure of incentives.

Change the incentives slightly—make it clear that employees will leave if they don't see real values, make it clear that customers prefer principled companies—and behavior shifts fast.

The Hoffman Thesis: Power and Responsibility Are Inseparable

Let's come back to Hoffman's core argument, because it's worth understanding precisely.

He's not saying tech leaders should be activists. He's not saying they should be partisan. He's saying something more fundamental:

If you have power, you have responsibility for how that power is used.

Silence is a choice. Inaction is a choice. Staying neutral is a choice.

And if you're making choices about how to use your power, you're already in the game. You're already being a participant. You're just not being honest about it.

The intellectually honest position is:

Either acknowledge that you have power and make active choices about how to use it. And be public about those choices. Or admit that you're choosing to stay out of politics and fully divest from political relationships.

But you can't have it both ways. You can't claim neutrality while maintaining government relationships, attending political events, and participating in policy conversations. That's not neutrality. That's dishonesty.

This is actually a more sophisticated version of the argument than just "speak up more." It's an argument about consistency. About honesty. About whether power implies accountability.

It's a question that extends well beyond tech.

Estimated data suggests that 'bending the knee' significantly impacts political neutrality and decision making, potentially undermining leadership effectiveness.

What Happens If Tech Leaders Don't Listen?

Here's the interesting question Hoffman doesn't fully explore: what if tech leaders largely ignore this call?

What if they continue walking the tightrope? Careful. Measured. Distanced?

Historically, when power centers avoid taking stands on fundamental questions, two things happen:

First, external pressure increases. If tech companies won't regulate themselves and won't take stands on ethics, then legislatures will do it for them. That's actually worse for business. Federal regulation is blunt. Internal ethics are nuanced.

Second, talent moves. Young people increasingly care about working for companies that align with their values. If you're seen as complicit, you lose that talent. To countries with less regulation, to smaller companies with clearer values, to fields with less moral ambiguity.

So ignoring this call isn't actually safe. It just creates different risks.

The real question is whether tech leaders will move proactively or whether they'll wait until regulation and talent loss force them. Usually, they wait. That's usually the pattern.

But Hoffman's argument is that waiting is a mistake. That acting first, acting clearly, acting principally is actually the smarter business move.

History will tell us whether he's right.

The Parallels to Previous Tech Accountability Moments

This isn't the first time the tech industry has faced a reckoning about power and responsibility.

Remember the Cambridge Analytica scandal? Tech companies claimed they didn't know their platforms were being used for political manipulation. Later, it became clear they did know. They just hadn't acted.

Remember the content moderation debates? Tech companies tried to be neutral arbiters. They failed. Because neutrality on platform speech isn't actually possible. Every moderation choice is a choice.

Remember the antitrust investigations? Tech leaders were surprised that their market dominance was being questioned. They hadn't realized that power invites scrutiny.

The pattern is always the same: tech leaders overestimate their ability to stay above the fray. They underestimate how their power makes them political actors whether they acknowledge it or not.

And they pay a price for that miscalculation.

Hoffman's argument is that the current moment is similar. Tech leaders are trying to stay above the fray on government overreach. But their power makes them actors in this drama. Pretending otherwise doesn't work.

Either lead. Or get led.

The International Dimension: Tech Power Across Borders

There's something else happening that makes this moment crucial.

Tech companies aren't just American. They operate globally. The choices they make about whether to stand up to government pressure in the U.S. sends signals to authoritarian regimes worldwide.

If the most powerful tech companies in the most free country on Earth are willing to compromise their values for business convenience, what message does that send to tech companies operating in China, Russia, or other authoritarian contexts?

It sends: your values are negotiable. Your principles have a price.

That's actually dangerous for global tech governance.

Conversely, if American tech companies establish a clear norm that certain boundaries aren't negotiable, that creates a stronger global standard.

This isn't just about U.S. politics. It's about what kind of global tech ecosystem we're building.

Hoffman understands this, even if he doesn't explicitly focus on it. The Silicon Valley choices today set precedent for tech companies worldwide tomorrow.

Can This Actually Shift? The Path Forward

So what would actually need to happen for tech leadership to change?

First: Board-level commitment

Boards would need to affirm that ethical positions on serious issues aren't liabilities. They're assets. They're how you build long-term value.

Second: Investor recognition

Major investors would need to signal that they value principled leadership. Right now, they mostly signal the opposite—they want risk minimization and safe choices.

Third: Coalition formation

Tech leaders would need to coordinate. It's much easier to take a stand if you're doing it with peers. One CEO standing alone looks reckless. Five CEOs standing together looks like leadership.

Fourth: Employee activism

Employees would need to keep pushing. The internal memos and petition signing are the right moves. That pressure actually works.

Fifth: Customer choice

Customers would need to actively prefer companies that take clear positions. Voting with your wallet is real power.

None of these are impossible. Some might actually happen. But it requires coordination and courage that tech leadership hasn't historically demonstrated.

What This Reveals About Silicon Valley Culture

Underlying all of this is a deeper cultural question about Silicon Valley itself.

Silicon Valley mythology says it's full of rebels. Visionaries. People who challenge the status quo. Who disrupt. Who think differently.

But when actual disruption would be costly, suddenly that's not the move. Suddenly it's careful. Conventional. Risk-averse.

It suggests that Silicon Valley's nonconformity is selective. It applies to industries and markets. It doesn't apply to power. It doesn't apply to authority.

That's actually a pretty damning insight about tech culture. You're only a rebel when rebellion is profitable.

Hoffman's call is essentially a challenge to that. If you really believe in what Silicon Valley is supposed to stand for, then this is the moment to prove it.

Not the easy moments. The hard moments.

The Stakes for Democracy and Tech

Let's zoom out. Why does this actually matter for democracy?

Because technology is infrastructure now. It's not separate from government. It's foundational to how government functions.

If the people who control that infrastructure won't use their power to defend democratic norms, then those norms erode.

That's not speculation. That's how institutions fail. The people with power choose convenience over principle. Institutions weaken. Abuses increase. Then people wonder how we got here.

Hoffman's argument is that this is the inflection point. This is the moment where choices matter.

Not because of any single issue, but because of the precedent being set.

Where This Goes From Here

So what happens next?

Most likely: things continue mostly as they are. Tech leaders make careful statements. They attend events. They maintain relationships. They try to have it both ways.

Most of the time, that works. Most of the time, you can maintain that balance.

But eventually, something breaks. The contradictions become too obvious. The pressure becomes too great. The precedent becomes too damaging.

Then change happens. Usually too late. Usually under pressure rather than proactively.

Hoffman's thesis is that tech leaders could avoid that if they just moved first. Made clear choices. Accepted the costs. Built coalition.

Whether they will is an open question.

But what's clear is that the current approach of ambiguity and strategic distance isn't actually working. It's just delaying the inevitable while eroding credibility in the meantime.

Lessons for Leaders Outside Tech

Actually, this applies beyond tech.

Any leader of a powerful organization faces similar questions.

Do I use my power explicitly and accept the costs? Or do I try to stay above the fray and hope for the best?

Do I stand for something or stand for nothing?

Do I lead or do I manage?

The tech example is just specific. The dynamic is universal.

Leadership is fundamentally about making choices. Choices about values. Choices about power. Choices about whether your organization stands for something or just chases profit.

Hoffman's argument is just: be honest about the choice you're making. Don't pretend neutrality is possible when it isn't.

That's actually sound wisdom for any leader in any industry.

FAQ

What exactly is Reid Hoffman's central argument?

Hoffman's argument is that Silicon Valley tech leaders cannot maintain true neutrality while possessing enormous economic and political power. He contends that silence and inaction are themselves choices, and that leaders who condemn specific government actions while maintaining strategic distance from the administration are being intellectually dishonest. He calls for tech leaders to explicitly wield their power to oppose harmful policies, rather than hope the problems resolve themselves without action.

Why should tech companies care about this if they face real financial risks?

While federal contracts and government relationships carry real financial weight, Hoffman argues that the long-term business case actually favors principled leadership. Tech companies face talent retention risks if employees feel their companies lack genuine values, potential regulatory backlash if industries self-regulate poorly, and reputational advantages if they lead on ethics authentically. Additionally, the business risk of appearing complicit in government overreach may ultimately exceed the financial risks of taking a clear stance.

How do tech workers view their companies' current responses to government overreach?

Internal employee petitions and leaked memos suggest tech workers view current company responses as insufficient and performative. Employees expect more than internal memos when companies publicly claim to support human rights and ethical governance. The disconnect between stated values and cautious political behavior is driving cynicism, affecting retention, and forcing leadership to grapple with credibility issues among the workforce that actually creates the company's value.

What does "bending the knee" specifically mean in practice?

Hoffman uses this phrase to describe specific behaviors like attending events that signal political alignment while simultaneously claiming to oppose the administration's actions, using internal memos to avoid public accountability, maintaining strategic distance from positions while still engaging with the administration on contracts, and avoiding public stands on fundamental issues in order to preserve government relationships and federal contracts.

Could tech companies actually coordinate on this issue without violating antitrust law?

Tech companies can legally coordinate on issues of public policy, government accountability, and ethical standards without violating antitrust law. Antitrust concerns primarily arise around competitive practices, pricing, and market allocation. Joint positions on government overreach or ethical standards constitute protected advocacy and public discourse, making coalition-building legally safe while creating practical power through unified positioning.

What's the difference between Elon Musk's approach and Tim Cook's approach?

Musk made an explicit, transparent choice to align closely with the Trump administration, which is politically controversial but intellectually coherent. Cook issued statements opposing specific government actions while simultaneously attending administration events, creating incoherence between his stated values and his actions. Hoffman's critique isn't necessarily that Musk's position is right, but that it's at least honest, whereas Cook's position is contradictory and therefore lacks credibility.

Does this argument apply to other industries or just tech?

The fundamental principle applies universally to any industry with significant economic power and influence. Any company with structural power faces similar questions about whether that power implies responsibility for its use. Hospitals, financial institutions, pharmaceutical companies, and energy companies all face analogous versions of this dilemma when power intersects with public welfare issues.

What concrete actions could tech leaders take if they actually heeded Hoffman's call?

Specific actions could include: publicly stating clear ethical positions on human rights issues, declining to attend events that signal support for administrations they've criticized, conditioning federal contracts on government adherence to humanitarian standards, building public coalitions with other tech leaders, actively supporting employee activism around ethics, conducting regular audits of government partnerships for ethical alignment, and communicating transparently with stakeholders about political decisions rather than hiding them in internal memos.

Why is this moment historically significant for tech leadership and governance?

This moment is significant because technology infrastructure is now foundational to government operations and democracy. The decisions tech leaders make about whether to exercise their power now establish precedent for how tech governance works globally and how technology companies interact with authoritarian regimes. If the most powerful companies in the freest country choose convenience over principle, it signals to tech companies everywhere that values are negotiable, which shapes the entire trajectory of tech governance.

What happens if tech leaders continue ignoring this call for clearer positions?

If tech leaders continue the current pattern of ambiguity, external pressure from legislatures will likely increase, leading to blunter regulatory tools that constrain business more severely than self-regulation would. Additionally, talent flight to companies with clearer values, reduced employee productivity from cultural cynicism, and erosion of customer trust will create financial consequences that eventually force change anyway, but under less favorable circumstances.

Conclusion: The Test of Silicon Valley's Character

Reid Hoffman's call to action is ultimately about character. Not his character—the character of Silicon Valley's leadership.

And that character is being tested right now.

Not in some abstract philosophical sense. In concrete, practical, high-stakes ways.

Will tech leaders use their power explicitly and accept the costs? Or will they continue the careful dance of appearing to care while protecting their interests?

Will they lead? Or will they manage?

Will they be honest about the choices they're making? Or will they hide behind the mythology that neutrality is possible?

These questions matter because the answer determines what kind of relationship technology and power have. Not just in the United States, but globally.

History suggests tech leaders will mostly stick with the status quo. That they'll continue the careful distance. That they'll hope the problems resolve themselves.

History also suggests that eventually, that won't work. That pressure will build. That change will come, but uglier and more disruptive than it needed to be.

But the possibility exists for something different. For tech leadership to move first. To be clear. To build coalition. To accept that power implies responsibility.

It's not the most comfortable choice. It's not the safest choice.

But it might be the smartest choice. Both for business and for democracy.

That's what Hoffman is arguing. And whether tech leadership actually listens will tell us a lot about their character, their judgment, and their future.

Key Takeaways

- Tech leaders aren't actually neutral—silence and inaction are choices that require accountability just like active positions do

- Federal contracts create real financial incentives to avoid political controversy, but this approach ultimately increases long-term business risk

- Employee activism is creating unprecedented pressure from within tech companies, threatening retention of top talent that actually creates company value

- The contradiction between stated values and political ambiguity is eroding leadership credibility faster than clear positions would, even controversial ones

- This moment sets global precedent for how tech companies interact with government power, influencing governance worldwide

Related Articles

- Warren Demands OpenAI Bailout Guarantee: What's Really at Stake [2025]

- Melania Documentary Cost Controversy: What the $75M Price Tag Really Reveals [2025]

- Slopagandists: How Nick Shirley and Digital Propaganda Work [2025]

- Face Recognition Surveillance: How ICE Deploys Facial ID Technology [2025]

- Big Tech's $7.8B Fine Problem: How Much They Actually Care [2025]

- Tech CEOs on ICE Violence, Democracy, and Trump [2025]