Space X's Play for Taxpayer Money: Why Starlink Broadband Grants Are Becoming Controversial

Something strange happened in early 2025. Space X, the company that made rockets cool again, sent letters to state broadband offices across America with a simple message: give us grant money, but don't expect us to promise anything in return.

This isn't hyperbole. The letter, obtained by broadband policy advocates, lays out a set of demands so one-sided that it's worth understanding what's actually happening here. Space X is leveraging a massive policy shift by the Trump administration to secure billions in federal broadband funding, yet it's structured its demands in ways that would let the company pocket taxpayer dollars regardless of whether it actually delivers reliable internet to the people those subsidies are meant to serve.

For anyone paying attention to broadband policy, infrastructure spending, or just how private companies work with government, this story reveals something fundamental about how corporate power operates in 2025. It's not that Space X is being unreasonable alone—it's that the entire system has shifted to make demands like this possible.

Let's dig into what Space X actually wants, why it's asking for it, and what it means for rural America's broadband future.

The BEAD Program: How $42 Billion Became a Satellite Company Windfall

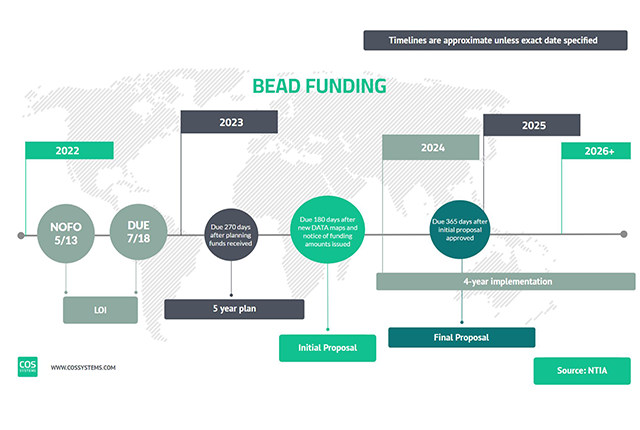

To understand Space X's demands, you need to understand the Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment program, or BEAD. Congress created it in 2021 as part of the infrastructure law, authorizing $42.6 billion to bring modern broadband to areas without it.

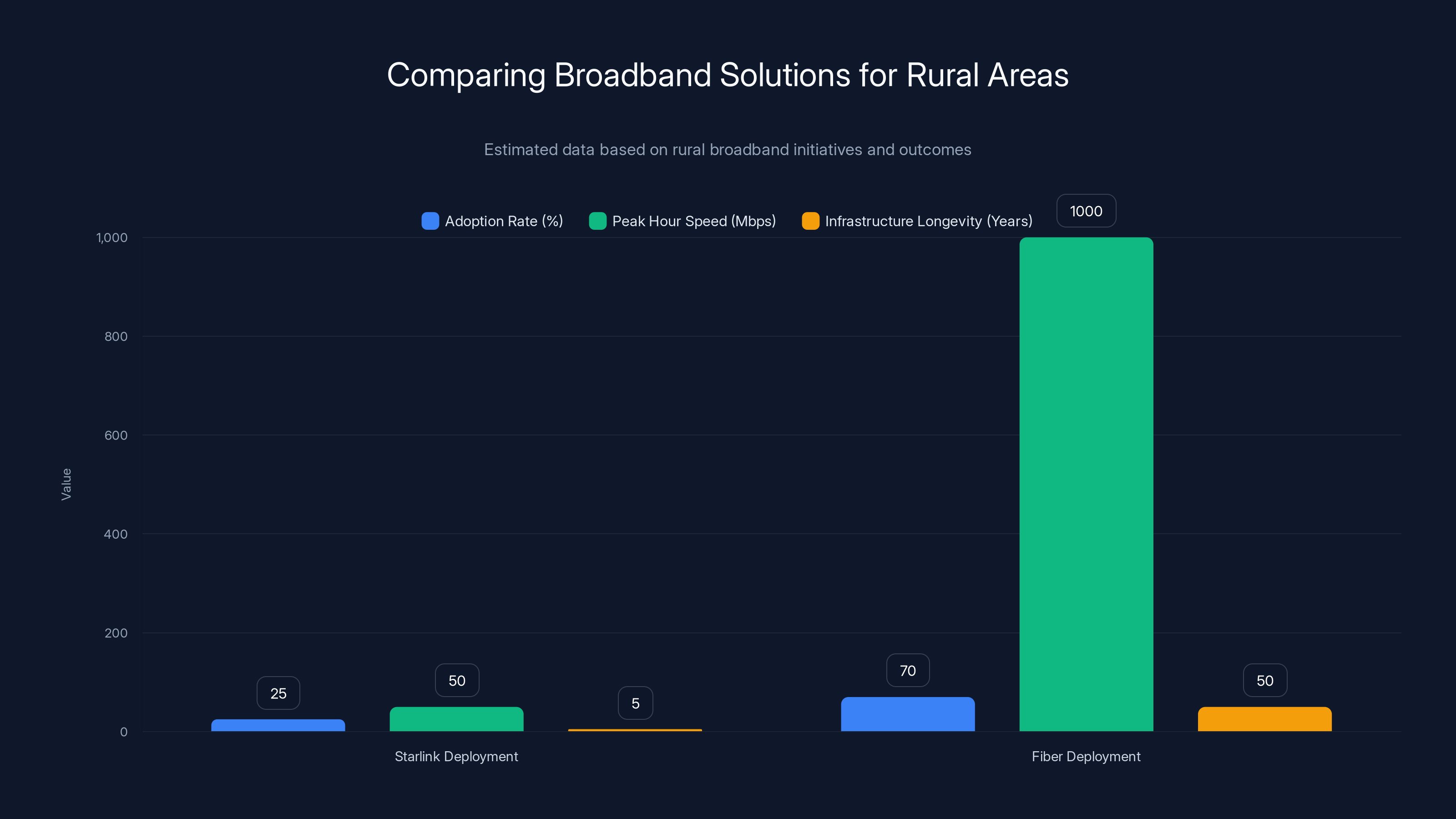

The original Biden-era design was fiber-focused. Fiber networks are physical, permanent infrastructure. They're built into communities, inspected regularly, and generate long-term economic benefits. The program prioritized these deployments because the logic was sound: fiber lasts 20 years or more, supports gigabit speeds, and can't be moved to a different state by corporate whim.

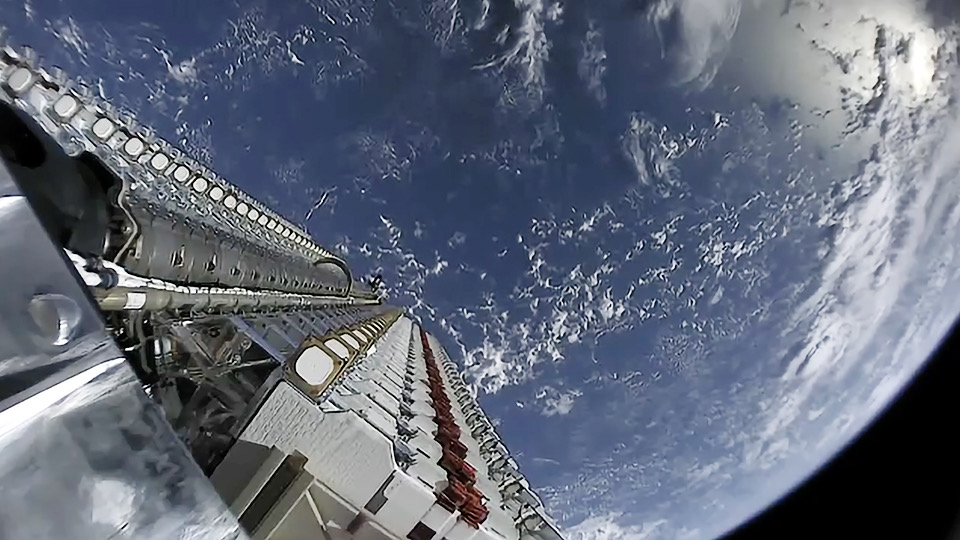

Satellite internet, by contrast, is different. Companies operate satellites in space, beam signals down to ground terminals, and can theoretically serve anyone with a clear view of the sky. No trenching, no local infrastructure, no permanent commitment to any particular location.

When the Trump administration took over in January 2025, it handed BEAD to the National Telecommunications and Information Administration, which quickly rewrote the rules. The result was seismic. The administration cut projected spending from

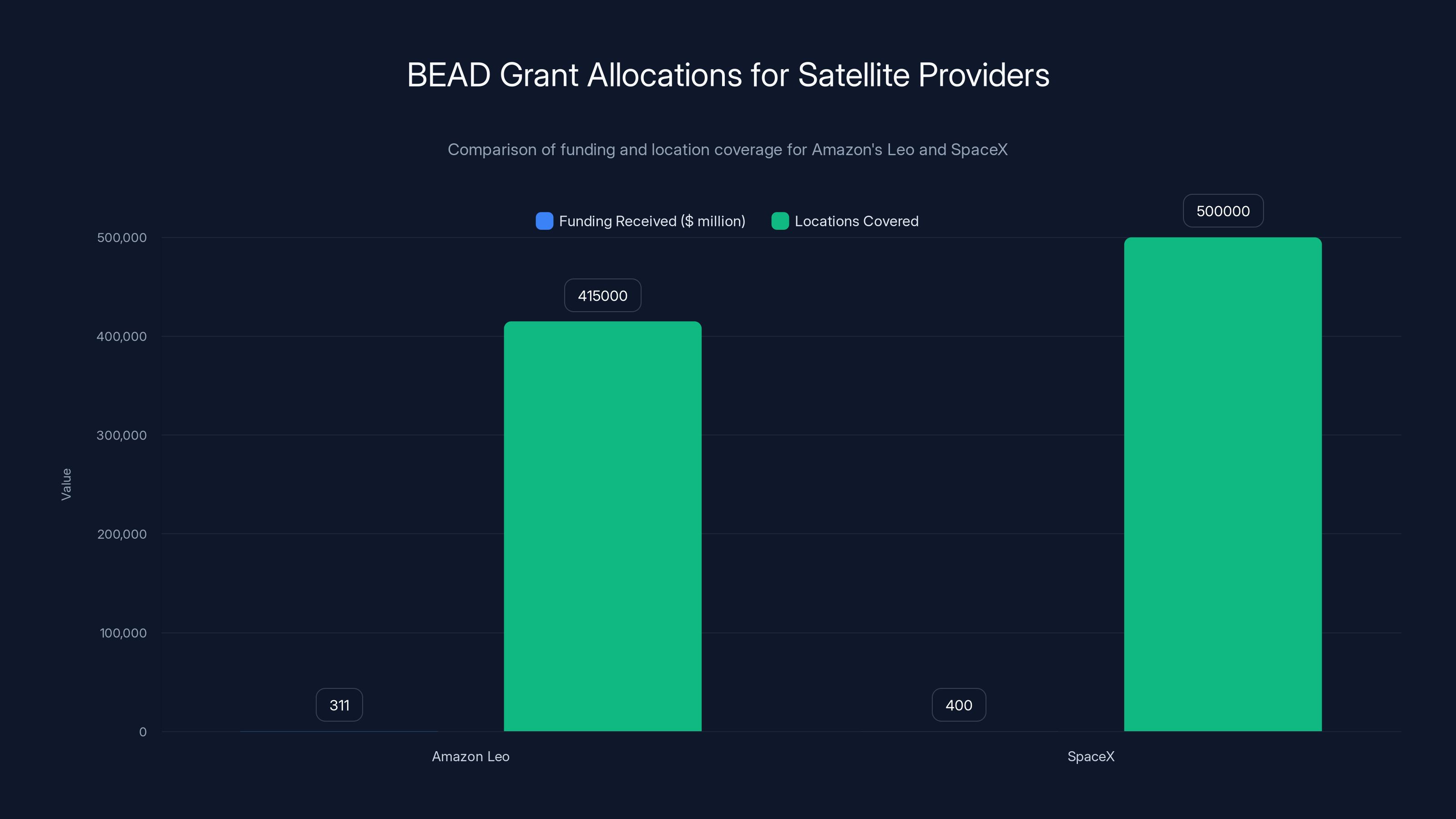

Under the new rules, Space X's Starlink became eligible for massive grants. The company immediately requested billions. States pushed back, negotiating lower amounts. Today, Space X is set to receive $733.5 million for 472,600 locations—making it one of the program's largest beneficiaries.

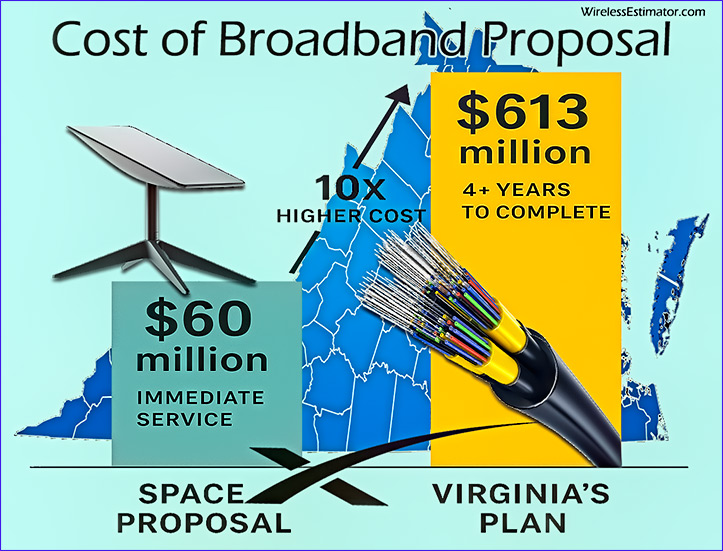

Here's where it gets interesting: Starlink is getting roughly

Because satellite companies don't have to build local infrastructure. They don't install fiber lines, copper cables, or poles. They just activate existing satellites and send ground terminals. From a cost perspective, it looks efficient. From a policy perspective, it creates a weird incentive: the easier a technology is to deploy, the less the government pays per location, even though the outcomes might be less reliable.

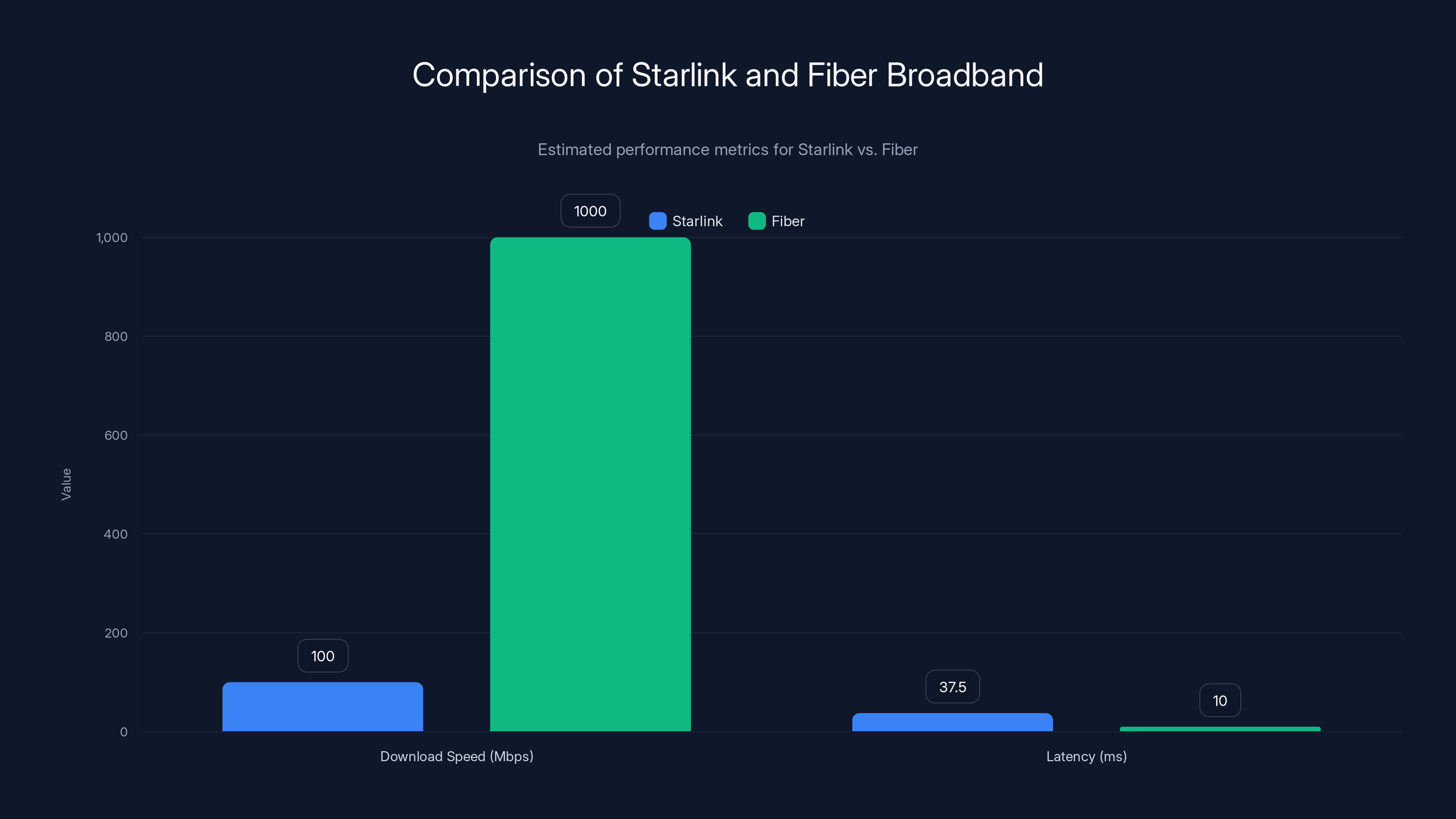

Fiber broadband generally offers higher download speeds and lower latency compared to Starlink, making it more suitable for high-demand applications. Estimated data based on typical performance ranges.

What Space X Actually Wants: The Letter's Explosive Demands

Space X's letter to state broadband offices reads like a masterclass in corporate leverage. The company is essentially saying: we'll take the grant money, but here's what we need in return.

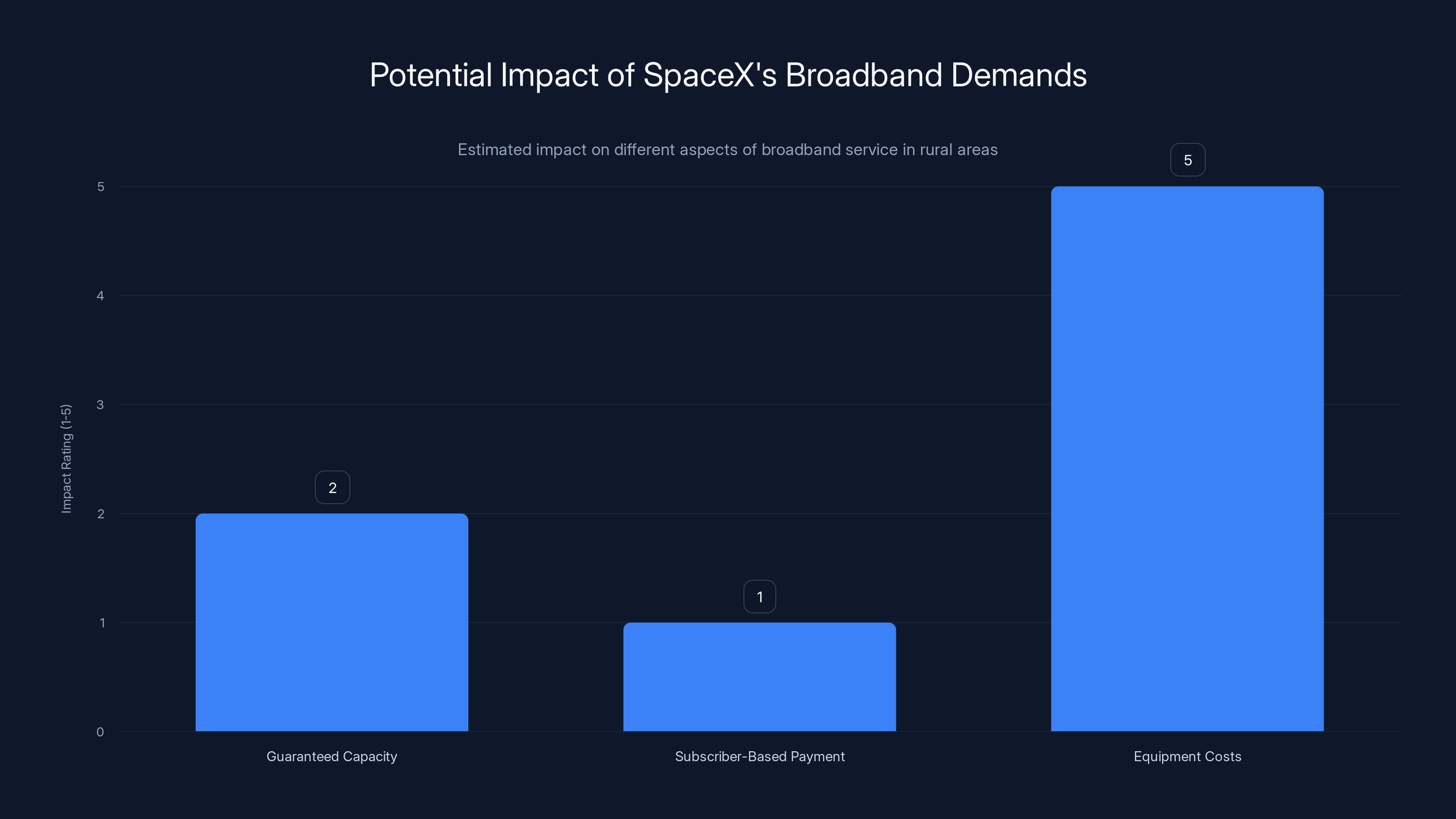

No specific promises on capacity. Space X won't reserve "large portions of capacity" for the subsidized areas. Instead, the company will "dynamically allocate capacity where needed." This sounds efficient in theory. In practice, it means Space X doesn't have to guarantee that your area gets good service during peak hours. If everyone in your state tries to use Starlink at dinner time, and Space X's satellites are congested, too bad.

Think about what this actually means. You're in rural Montana. The government gives Space X $733.5 million to serve your area. But Space X doesn't promise that you'll get a certain download speed, a certain latency, or a certain amount of available bandwidth. It just promises to allocate capacity "where needed"—which could mean allocating it to Los Angeles instead.

No payment based on actual subscribers. This is the really provocative one. Space X says grant payments shouldn't depend on "the independent purchasing decisions of users." In other words: we get paid even if nobody buys the service.

Imagine a scenario. Space X receives

Fiber companies negotiating BEAD grants usually accept performance clawbacks. If they deploy infrastructure but adoption lags, their final payment drops. Space X is saying that shouldn't apply to them.

Equipment costs disappear for customers. Space X pledges to provide all equipment "at no cost to subscribers requesting service." The normal Starlink hardware fee is $599. For low-income households in subsidized areas, this elimination matters. But here's the catch: Space X says installation isn't its responsibility.

Space X won't handle installation. This is arguably the most problematic demand. Space X says it's "not responsible for ensuring that Starlink equipment is installed correctly at each customer location." So the company provides the dish, but someone else handles installation. That someone? Probably the customer. Or maybe the state. Or maybe nobody, and the equipment sits in a box.

Installation matters tremendously for satellite service. Dishes need clear southern sky exposure. They need to be mounted at the correct angle. A misaligned dish can cut speeds by 50%. If installation is the customer's problem, adoption plummets, and the entire program underperforms.

Labor rules don't apply. Space X argues that because there are no "identifiable employees, contractors, or contracts being funded" to support Starlink service in each state, prevailing wage requirements and contractor standards shouldn't apply. The company is essentially saying: this is a space company, not a broadband company, so terrestrial labor rules don't matter.

No reporting requirements. Space X wants to minimize reporting obligations and financial disclosures related to how BEAD funds are used. Traditional infrastructure grants require detailed accounting. Space X is asking for exemptions.

Minimal penalties for non-compliance. The letter asks to "limit... non-compliance penalties, reporting expectations," essentially asking states to be lenient if Space X fails to meet whatever minimal obligations it does accept.

Stripped of corporate language, Space X's position is this: pay us, don't require us to promise specific outcomes, don't penalize us if we underperform, and don't ask us to follow the same rules as terrestrial providers.

The Policy Shift That Made This Possible

Space X didn't invent these demands in a vacuum. The Trump administration's rewrite of BEAD rules created the conditions for them.

Under Biden's version, satellite providers faced significant skepticism. The program's entire architecture was designed around terrestrial networks. Rules required performance metrics, capacity guarantees, and local accountability. Satellites didn't fit neatly into this framework.

The new NTIA rules, implemented in June 2025, changed everything. Satellite providers now get treated more like terrestrial networks, but without the same obligations. The rules were rewritten to be, as one policy expert put it, "LEO-friendly"—LEO stands for low-Earth orbit satellites like Starlink.

Why the shift? The Trump administration viewed fiber deployments as too expensive. Satellite services looked cheaper, faster to deploy, and less tied to traditional construction unions—which aligns with the administration's deregulatory philosophy. The math seemed straightforward: spend less money, deploy internet faster, move more quickly through the grant process.

But speed and cheapness come with trade-offs that the policy doesn't adequately address. Fiber lasts decades. Satellites require continuous service contracts. Fiber can support gigabit speeds indefinitely. Satellites have shared spectrum and congestion issues. Fiber becomes local infrastructure, improving property values and enabling future services. Satellites can disappear if Space X decides to relocate orbital resources.

The policy shifted without fully reckoning with these differences.

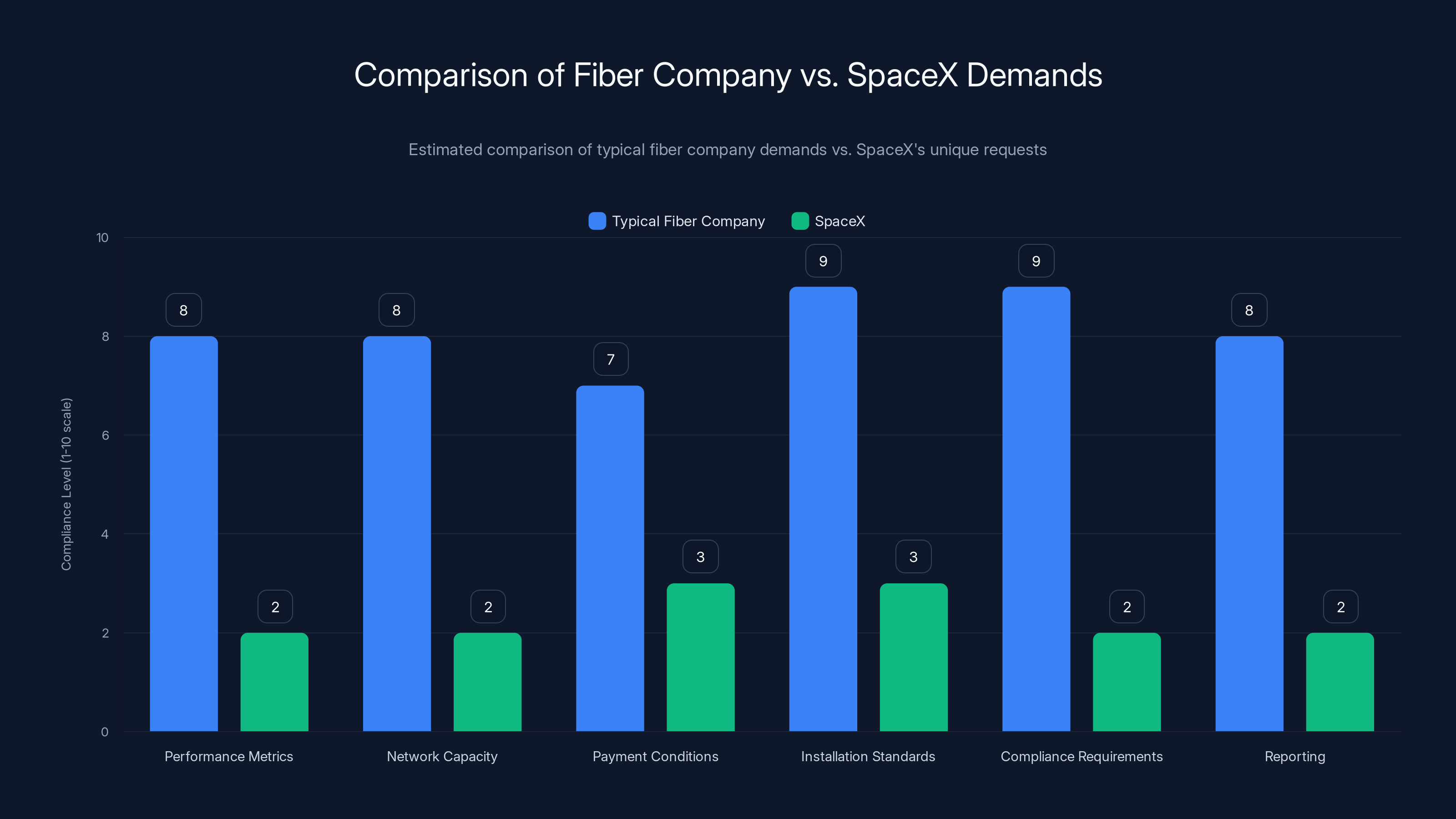

SpaceX's demands could lead to low guaranteed service capacity and payment regardless of subscriber uptake, but eliminate equipment costs for users. Estimated data.

How Much Money Are We Talking About?

Let's quantify the stakes. Space X's total BEAD allocation is $733.5 million for 472,600 locations. That's money extracted from federal coffers to deploy broadband.

Amazon's Leo service will receive

How much is that of the total? While not every state has finalized its plans, preliminary data suggests satellite networks will receive about 5% of total BEAD grant money but serve over 22% of funded locations.

This creates a strange inversion. Satellite companies are serving more locations but getting less money per location than fiber providers. From a taxpayer efficiency standpoint, that looks good. From a quality-of-service standpoint, it's concerning. Those lower payments per location mean lower service guarantees, thinner margins, and less accountability.

The Fiber Company Comparison: Why Space X's Demands Stand Out

To understand how unusual Space X's demands are, compare them to what fiber companies negotiate.

Typical fiber BEAD grants include performance metrics. The provider promises specific download/upload speeds, latency thresholds, and uptime guarantees. If actual performance falls short, final grant payments are clawed back.

Fiber companies typically have to reserve network capacity for subsidized areas. If the grant funds service to 5,000 homes, the company dedicates capacity for those 5,000 connections.

Payment usually includes adoption hurdles. If the provider deploys fiber to 5,000 locations but only 2,000 subscribe within three years, final payment might be 40% lower than contracted.

Installation is either the provider's responsibility or explicitly contracted out with specific standards and penalties for poor work.

Fiber companies have to comply with all prevailing wage laws, apprenticeship requirements, and contractor standards. These rules ensure that broadband deployment creates stable jobs.

Reporting is comprehensive. States and the federal government receive quarterly or annual reports on deployment progress, subscriber counts, service quality, and fund usage.

Space X is asking to sidestep almost all of these.

What This Means for Rural Broadband

Here's what concerns broadband policy experts. The BEAD program was supposed to close the digital divide. Rural America lacks broadband. Cities have it. The federal government decided to spend

If Space X's demands become standard across state agreements, the program's outcome might be degraded. Picture a rural county in Arkansas. Government funds Starlink service. Space X activates satellite beams over the area. But with no capacity guarantees, peak-hour speeds are inconsistent. With no installation support, adoption is lower than projected. With minimal reporting, nobody knows if service is actually improving people's lives.

Fast forward three years. The county has Starlink service, but adoption is 25%, speeds are mediocre, and the commitment is temporary. Meanwhile, the federal government has spent $50 million, and has nothing permanent to show.

Contrast this with a fiber deployment. The same $50 million builds permanent infrastructure serving the same area. It enables gigabit speeds. It attracts technology companies. It increases property values. It works in perpetuity.

This isn't an anti-Space X position. Starlink has legitimate advantages. It reaches areas fiber never will—remote ranches, isolated communities, areas where fiber economics don't work. But the BEAD program is explicitly designed to address underserved areas, and permanent, reliable infrastructure is its goal.

When a company's business model depends on avoiding permanent commitments, and the program's success depends on permanent infrastructure, there's a structural misalignment.

SpaceX's demands are significantly lower across all categories compared to typical fiber companies, highlighting their unique approach. Estimated data based on industry norms.

Labor, Standards, and the Installation Problem

Space X's claim that labor rules don't apply reveals a deeper issue with how satellite deployment differs from terrestrial broadband.

Fiber deployment is labor-intensive. Trenching, splicing, testing, and installation create jobs. BEAD rules require prevailing wages partly to ensure these jobs are good jobs. A fiber technician installing broadband in rural Colorado might make $65,000 annually with benefits.

Starlink deployment is capital-intensive but not labor-intensive. Activating satellites and shipping ground terminals employs relatively few people. The company's argument that labor rules don't apply because there's no local labor is technically true but philosophically dishonest. If the company is claiming federal money to deploy broadband, it's reasonable to ask what that money buys in terms of economic development.

The installation problem is more acute. Satellite equipment is harder to install than fiber. Fiber is mostly automated. Connect fiber to a house, light it up, done. Satellites require customer-side equipment, proper alignment, clear sky exposure, and sometimes electrical work.

Space X says it won't be responsible for installation. Who will be? Options include:

The customer installs it. This is fast and cheap but creates equity problems. Tech-savvy customers succeed. Elderly or disabled customers struggle. Rural customers might lack local contractors familiar with the equipment.

States hire contractors. This is expensive and ties up grant money. Instead of funding network deployment, money goes to installation labor.

ISP partners handle installation. This could work but requires coordination and profit-splitting.

Nobody handles it well. Equipment gets installed poorly, speeds suffer, adoption disappoints.

Fiber companies typically own the installation process. They control quality. They manage the customer experience. This is why fiber BEAD deployments usually include robust adoption rates. Space X avoiding responsibility for installation is a cost-cutting move that likely degrades outcomes.

The Capacity Question: Why Dynamic Allocation Isn't a Guarantee

The claim about "dynamic capacity allocation" sounds reasonable until you think through what it means operationally.

Starlink operates a constellation of satellites in low-Earth orbit. These satellites have finite bandwidth. As more users connect to the same satellites, available bandwidth per user decreases. This is basic orbital mechanics and spectrum physics.

Dynamic allocation means Space X will direct bandwidth to where it's most needed. During peak hours in New York City, traffic might get priority over traffic in rural Montana. This maximizes overall system efficiency.

But BEAD grants are supposed to guarantee service to specific locations. If Montana residents can't count on capacity being available for their subsidized service, the grant's purpose erodes.

Fiber doesn't have this problem. Fiber capacity can be reserved for specific areas. Oversubscribe the network in urban areas, but oversell Montana's allocation, and Montana customers get their promised speeds regardless.

This distinction matters enormously for service reliability, and it's one reason fiber companies can make specific performance promises while Space X resists them.

Political Context: Why the Trump Administration Enabled This

Understanding why the Trump administration rewrote BEAD rules requires understanding its policy philosophy.

The administration views broadband as important but fiber-heavy deployments as bloated. It wants faster, cheaper deployments using commercial technology. Satellite internet delivers on both fronts—deployment is rapid, costs are lower.

The administration is also friendly to Space X generally. Elon Musk has political relationships within the Trump orbit. The company operates government contracts for national security launches. There's political alignment.

Deregulatory philosophy reinforces this. The original BEAD rules imposed extensive requirements—performance metrics, labor standards, reporting, local accountability. These are the kind of regulations the Trump administration views as burdensome.

Satellite deployment, by its nature, requires fewer of these regulations. Satellites operate in space, not subject to traditional terrestrial rules. This became a feature, not a bug, in the policy rewrite.

The administration also calculated that cheaper broadband deployments free up federal money for other priorities. The

None of this is unusual in the context of political administrations. Each new administration rewrites infrastructure rules to match its philosophy. But the speed and extent of the BEAD rewrite surprised many policy observers.

Fiber deployment offers higher adoption rates, faster speeds, and longer-lasting infrastructure compared to Starlink in rural areas. Estimated data.

What States Are Actually Doing: Are They Accepting Space X's Terms?

Space X's letter is a proposal, not law. States have the authority to reject its terms or negotiate modifications.

So far, states have been receptive but cautious. The company's $733.5 million allocation suggests states have accepted some version of these terms, since that's the amount Space X was awarded. But state BEAD plans aren't public enough to know exactly what terms are in each contract.

Some states are presumably more resistant. States with strong broadband policy expertise, like Vermont or Washington, might push back harder. States with less infrastructure policy capacity might accept Space X's boilerplate.

The Benton Institute and other advocates are pressuring states to reject Space X's demands. They argue that accepting minimalist commitments defeats BEAD's purpose.

One complication: if states reject Space X's terms too harshly, the company might withdraw. States don't want to lose satellite coverage entirely, especially in areas where fiber deployment is economically infeasible. This gives Space X negotiating leverage.

We don't yet know if any states have rejected Space X's rider outright, or if all of them have accepted some modified version. Contract details often remain confidential.

The Broader Implications: Infrastructure, Accountability, and the Public Interest

Zoom out. Space X's demands reveal a larger tension in how government funds infrastructure in the 21st century.

Traditional infrastructure—bridges, highways, water systems—had to meet specific standards. You didn't give a contractor a billion dollars to build highways "where needed." You specified routes, standards, maintenance requirements, and oversight.

Modern infrastructure, especially involving technology and space, is more complex. Private companies operate in domains (space, spectrum) that government doesn't directly control. This creates asymmetry. Government funds infrastructure, but companies control the underlying resources.

Space X's position is that this asymmetry requires flexibility. The company operates satellites, which the U. S. government doesn't directly control. The company can't promise capacity it doesn't own. The company operates in real-time spectrum conditions that vary unpredictably.

The counterargument is that government funding should buy accountability. If taxpayers are funding a broadband deployment, taxpayers deserve to know whether it works, whether people use it, and whether promised speeds are delivered.

This isn't a dispute unique to Starlink. Amazon, for instance, faces similar questions as it develops Leo satellite service. Future infrastructure programs will face similar tensions.

The resolution probably involves hybrid approaches. Governments fund satellite deployments but impose clearer performance metrics. They allow capacity sharing but require minimum reserves for subsidized areas. They accept that installation might be customer-managed but require training and support programs. They harmonize labor rules creatively rather than exempting satellite companies entirely.

Amazon's Leo Service and Competitive Pressure

Space X isn't alone in pursuing BEAD grants. Amazon's Project Leo (formerly Kuiper) is also in the competition.

Amazon is receiving $311 million for 415,000 locations. The company is similarly seeking favorable contract terms, though its approach has been less publicly aggressive than Space X's.

If Space X's terms become standard, Amazon will expect equivalent treatment. This could create a cascade where both companies operate with minimal performance obligations.

Competition could theoretically drive better service. Two satellite providers competing for customers might improve reliability and speeds to differentiate themselves.

But BEAD deployments aren't market-competitive. The government picks one provider per area based on cost and capability. Once selected, there's no local competition. A rural county doesn't get Starlink and Leo; it gets one or the other.

In this context, competitive dynamics don't discipline poor service. A Starlink customer in Montana has no Amazon Leo alternative. If Starlink's service is mediocre, the customer's recourse is limited.

Amazon's Leo received

What Happens if Space X Underperforms: Legal and Policy Remedies

Suppose Space X receives its $733.5 million, deploys Starlink service to 472,600 locations, but speeds are poor and adoption is low. What recourse do states and the federal government have?

If Space X's contracts include minimal performance guarantees, legal recourse is weak. The company can argue it deployed the service as promised, even if actual performance is disappointing.

Clawback mechanisms are the main enforcement tool. These are contractual provisions that reduce final payment if performance falls short. But Space X is explicitly asking to limit clawbacks.

Lawsuits are theoretically possible but practically difficult. Suing a defense contractor while it holds national security contracts creates political complications.

The most likely scenario is administrative pressure. The NTIA could require better terms in future funding rounds. States could collectively refuse particularly onerous demands. Advocacy groups could pressure Congress to revise BEAD rules again.

But in the near term, if Space X receives its allocation, enforcement is limited without robust contracts.

The Fiber Alternative: Why Some States Are Still Choosing Fiber

Not every state is ceding everything to satellites. Some rural areas are still pursuing fiber deployments, even with BEAD's satellite-friendly rewrite.

The logic is durable infrastructure. Fiber lasts 20+ years. It supports gigabit speeds indefinitely. It enables future services like virtual reality, telemedicine at high definition, and advanced manufacturing technologies that haven't been invented yet.

Satellites are more limited in lifespan. Starlink satellites orbit for about 5 years, then de-orbit. Maintaining service requires continuous satellite replacement and launch costs. This creates ongoing operating expenses.

Fiber is also more competitive. Once fiber exists in an area, multiple companies can lease access. This drives pricing down and service quality up. Satellite service is more monopolistic—if you want Starlink, you buy from Space X.

Some states are hybrid-deploying. Fiber to community centers, schools, and municipal buildings; Starlink to rural homes where fiber doesn't reach. This combines permanent infrastructure with satellite flexibility.

But hybrid approaches require more money and more planning. States facing budget pressure often default to pure satellite solutions because they're cheaper and faster.

International Precedent: How Other Countries Handle Satellite Broadband Grants

Looking beyond the U. S., other countries are grappling with similar questions.

The European Union has been more cautious about satellite-only broadband funding. EU broadband policy emphasizes "very high capacity networks," which traditionally meant fiber but now includes fixed wireless and satellite as complements to terrestrial infrastructure.

EU rules require beneficiary countries to ensure open access to subsidized infrastructure, meaning other ISPs can lease capacity. This prevents monopolistic control.

Canada has funded rural broadband via both fiber and satellite, but with explicit performance guarantees. Providers commit to specific speeds and are penalized if they underperform.

Australia's National Broadband Network, while troubled, included more detailed contracts with service providers specifying deployment timelines, performance standards, and penalty mechanisms.

These international examples suggest that government-funded broadband deployment almost always includes stronger safeguards than Space X is asking for in the U. S. This raises questions about why the Trump administration's BEAD rewrite is more permissive.

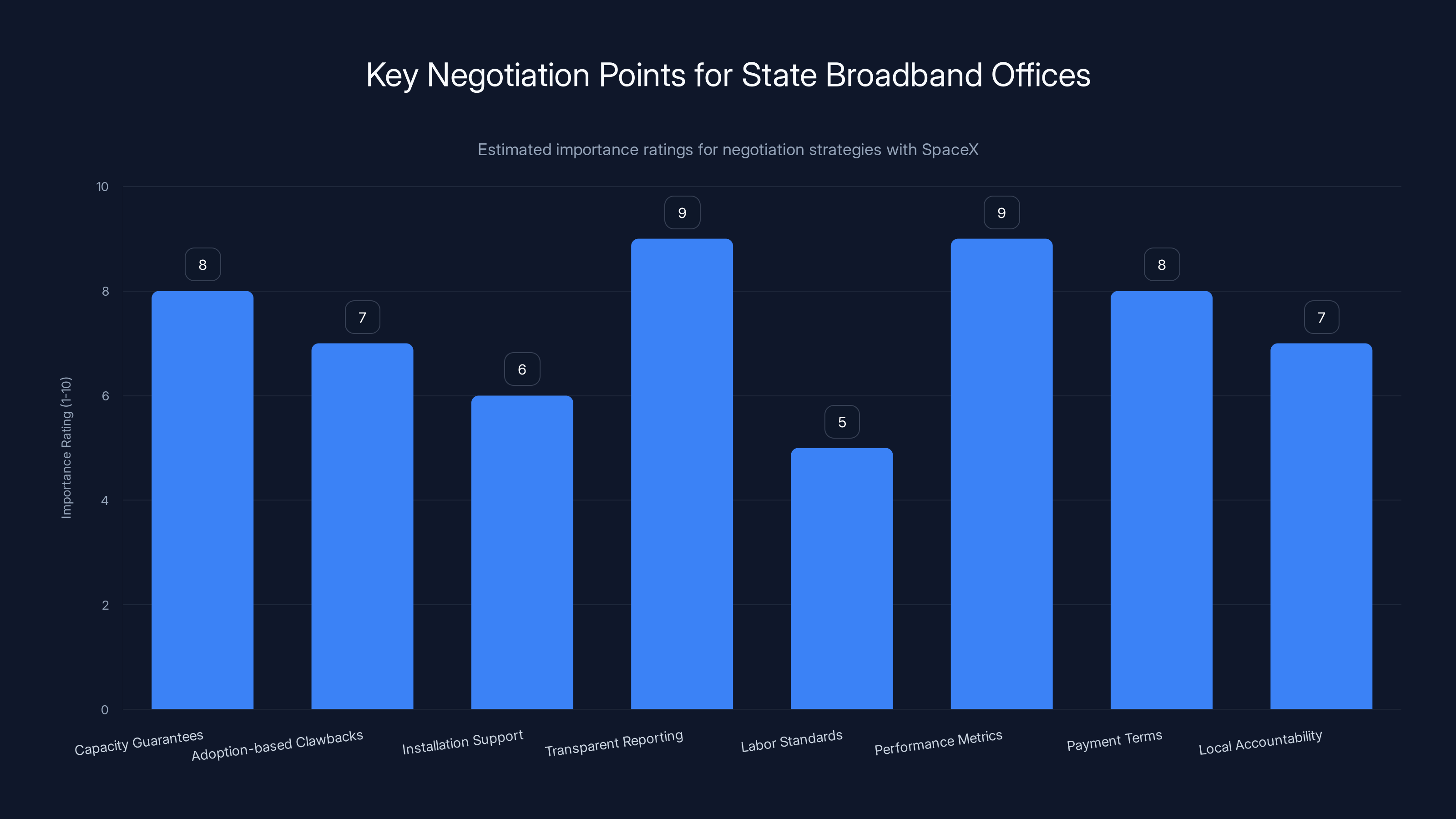

Transparent reporting and performance metrics are rated highest in importance for negotiations with SpaceX, emphasizing accountability and service quality. Estimated data.

The Installation and Customer Service Problem: A Practical Perspective

Here's a concrete example of why installation matters. A rural family in Wyoming signs up for Starlink through a BEAD program. They receive a ground terminal in the mail.

If installation is the customer's responsibility, they have to:

- Find the best mounting location on their home

- Install a pole or bracket without damaging the roof

- Run power and ethernet to the equipment

- Perform initial alignment tests

- Troubleshoot connectivity issues

For a tech-savvy 45-year-old with YouTube and contractor contacts, this is manageable. For a 78-year-old farmer or a family unfamiliar with networking hardware, it's daunting.

If installation is misaligned, speed drops from 50 Mbps to 15 Mbps. The customer might blame their connection when the actual problem is a physical installation error.

Now scale this to 472,600 locations. If installation quality varies wildly, actual service quality varies wildly. Some customers get excellent service. Others get mediocre service despite receiving the same equipment from the same company.

This creates a customer service and reputation problem for both Space X and the government. People blame the broadband provider. But the provider, having no installation responsibility, denies liability.

Fiber companies avoid this by controlling the entire experience. They install fiber to a home, install the modem, test the connection, and guarantee speeds. The customer experience is consistent.

Space X wanting to avoid installation responsibility is understandable from a cost perspective. But it creates exactly the kind of uneven outcomes that make government broadband programs unpopular.

The Reporting and Transparency Question

Space X wants to minimize reporting obligations. This is worth examining because it affects public accountability.

When government funds infrastructure, the public should know:

- How much was spent on what

- How many people actually use it

- Whether promised performance was delivered

- Whether the investment generated economic benefits

Traditional BEAD reporting requires:

- Quarterly deployment progress reports

- Annual subscriber count data

- Service quality metrics (speed, latency, uptime)

- Financial accounting of fund usage

- Economic impact assessments

Space X is asking to minimize these disclosures. The company's rationale is that satellite operations don't fit terrestrial reporting frameworks. The counterargument is that if the government is investing taxpayer money, transparency shouldn't be optional.

Poor reporting also limits learning. If a BEAD-funded satellite deployment works well, other states should know. If it underperforms, states should learn why. Transparent reporting enables evidence-based policymaking. Minimal reporting obscures outcomes.

Advocates like the Benton Institute argue that Space X's reporting minimization requests are among the most problematic of its demands because they prevent oversight.

Prevailing Wage and Labor Standards: Why Space X's Exemption Request Matters

Space X's argument that labor standards don't apply is worth analyzing carefully.

The company correctly notes that Starlink deployment doesn't require large numbers of construction workers, electricians, or fiber technicians. Satellite activation is software-intensive, not labor-intensive.

However, BEAD funding supports broadband deployment more broadly. If Space X uses BEAD grants to fund anything—corporate salaries, equipment procurement, infrastructure operation—the argument that labor standards don't apply becomes weaker.

Moreover, the spirit of BEAD rules is to ensure that federal broadband funding creates economic benefits in the communities it serves. Prevailing wage requirements ensure that whatever labor is required generates family-supporting jobs.

Space X's exemption request essentially says: we'll take federal money for broadband, but we don't think federal labor standards should apply. This is philosophically inconsistent.

Fiber companies accept prevailing wage standards even though their work is becoming increasingly automated. They do this because accepting public funding carries public obligations.

Space X's pushback suggests the company sees public funding as a corporate subsidy, not a public investment. This distinction matters for how we think about government-private partnerships.

The Capacity Dynamics: What Peak-Hour Congestion Might Look Like

To understand Space X's dynamic allocation claim concretely, imagine a scenario:

It's 7 PM on a Saturday. A rural Montana county has 2,000 Starlink subscribers. They're all trying to stream video for dinner-time entertainment. Demand spikes. Starlink's satellites over Montana are at 90% capacity.

Simultaneously, Los Angeles's suburbs have 50,000 Starlink subscribers, and demand there is lower. Those satellites are at 40% capacity.

Space X's system dynamically allocates capacity where it's needed. It prioritizes Los Angeles because more users create more total demand. Montana gets less capacity, speeds drop, streaming buffers.

This is efficient from a network-engineering perspective. It maximizes total throughput. But it violates the principle that BEAD-subsidized service should be reliable.

Fiber providers, by contrast, provision capacity for each service area independently. Montana's fiber has dedicated capacity for Montana customers. Peak hours in Los Angeles don't affect Montana.

This is less efficient from a theoretical network perspective but more reliable for customers. And reliability is what BEAD funding is supposed to guarantee.

Space X's resistance to capacity reservations is rational given satellite physics. But it's fundamentally incompatible with broadband deployment that promises reliable service.

What States Should Do: Negotiating Better Terms

If you're a state broadband office considering Space X's proposals, what should you do?

Push for capacity guarantees. Require that Space X reserve specific capacity for subsidized areas during peak hours. If Space X says this isn't possible, negotiate on percentages—perhaps 80% of promised capacity is reserved, 20% is dynamic.

Include adoption-based clawbacks. If Space X deploys service but adoption is well below projections, final payment should reflect that. This gives the company incentive to ensure actual deployments work well enough that people actually use them.

Require clear installation support. Specify who handles installation, what quality standards apply, and what happens if installation fails. Don't leave this ambiguous.

Demand transparent reporting. Require quarterly reports on deployment progress, subscriber counts, service quality metrics, and fund usage. Make these public. Transparency isn't just good governance; it creates pressure for performance.

Define labor standards. Even if satellite deployment doesn't employ many local workers, clarify expectations. If Space X subcontracts any work, those contractors must follow prevailing wage standards. If Space X uses BEAD funds for any employment, labor standards apply.

Set performance metrics. Specify minimum download/upload speeds, latency requirements, uptime expectations, and consequences for failing to meet them. Performance metrics are standard in broadband grants and Space X shouldn't expect exemptions.

Limit payment terms. Don't prepay. Structure payments to milestone completion and performance verification. This aligns incentives.

Require local accountability. Establish oversight mechanisms. Create a broadband advisory committee including community members. Hold Space X accountable to local stakeholders, not just federal requirements.

These negotiating positions aren't anti-Space X. They're pro-accountability. If Space X is confident in its service, it should accept performance metrics. If the company believes installation is difficult, it should support customers. If satellite deployment is straightforward, reporting should be simple.

The Equity Angle: Who Loses Under Minimal Commitments

Here's who loses if Space X's terms become standard:

Rural elderly. Older people struggle with installation and technology setup. Minimal company support means they either struggle to get online or don't try.

Low-income households. These are the populations BEAD is supposed to serve. Minimal performance guarantees mean they're more likely to experience spotty service and might stop paying if service is unreliable.

Students. Rural students need consistent broadband for homework and online learning. Dynamic capacity allocation might mean slow speeds during peak evening study hours.

Small businesses. Rural entrepreneurs depend on reliable broadband for e-commerce and digital services. Unreliable satellite internet undermines business viability.

Future opportunities. Communities benefit long-term from permanent broadband infrastructure that attracts new residents, businesses, and opportunities. Temporary satellite service doesn't create the same transformative effects.

Equity advocates argue that Space X's demands, while economically efficient from the company's perspective, are socially regressive. They shift risk onto precisely the populations the grant program is meant to help.

Looking Forward: What Comes Next

We're in the early stages of Space X's BEAD participation. The company has been awarded funding but hasn't completed deployment everywhere yet.

Several scenarios are possible:

Scenario 1: Space X's terms become standard. States, facing budget pressure and deployment urgency, accept the company's boilerplate. Other satellite companies follow suit. BEAD deployments deliver broadband but with limited performance guarantees. Outcomes are mixed.

Scenario 2: States negotiate harder terms. State broadband offices, informed by advocates, push back on Space X's demands. The company compromises, accepting some performance metrics and reporting requirements. Deployments include more accountability.

Scenario 3: Congress revises BEAD again. If early-stage satellite deployments prove problematic, Congress might intervene, restoring some performance requirements and capacity guarantees.

Scenario 4: A hybrid approach emerges. States learn to structure satellite deployments with realistic performance expectations, focused on areas where fiber is infeasible, with fiber handling areas where it makes sense.

Most likely, we'll see a combination of these. Some states will accept Space X's terms. Others will negotiate better ones. Congress might eventually tighten rules. Performance will vary widely.

When that happens, the variance will tell us something important about what happened in 2025 when the broadband policy framework shifted radically.

The Bigger Picture: Infrastructure and Corporate Power in 2025

Zoom all the way out. Space X's BEAD demands are a specific example of a broader trend: as government outsources infrastructure to private companies, corporate leverage increases.

Space X isn't unique in seeking favorable terms. Amazon, Microsoft, Google—all technology companies push government contracts and grants toward terms that minimize their obligations and maximize their revenue.

This is business logic. Companies exist to maximize shareholder value. Minimizing obligations and maximizing revenue are how that works.

But it creates a governance problem. Government programs exist to serve public goals: connecting rural America to broadband, for instance. When corporate interests and public interests misalign, government must have leverage.

Lever number one is the ability to say no. If government doesn't need a particular company's technology, it can set tough terms. But if the company has unique assets (like Space X's satellites), government's negotiating position weakens.

Lever number two is accountability. Government can require transparency, performance metrics, and clawbacks if performance fails. But this requires administrative capacity and political will to enforce.

Lever number three is alternatives. If multiple companies can deliver similar services, competition disciplines behavior. But satellite broadband has limited competitors. Space X and Amazon are essentially it.

Space X's BEAD situation reveals that government has been relying too heavily on levers two and three, which are weak. It's not deploying lever one effectively—sometimes saying no to corporate demands that are simply incompatible with public goals.

This is a 2025 problem, but it will persist. As government funds more technology infrastructure, more companies will demand favorable terms. Learning to negotiate effectively will define whether these programs achieve their goals.

FAQ

What exactly does Space X's BEAD grant cover?

Space X's $733.5 million BEAD allocation is supposed to deploy broadband service to approximately 472,600 rural and underserved locations across multiple states. The grant funding covers activating satellite service, providing ground terminals to households, and supporting initial deployment efforts, though the exact scope varies by state agreement. Space X uses these funds to expand Starlink's footprint in areas where broadband infrastructure is currently unavailable or inadequate.

Why did the Trump administration change BEAD rules to favor satellite companies?

The Trump administration viewed the Biden-era BEAD program as overly expensive and fiber-focused. The administration's National Telecommunications and Information Administration rewrote rules to reduce projected spending from

What happens if people don't subscribe to Starlink in BEAD-funded areas?

Under Space X's proposed terms, the company gets paid regardless of subscription rates. This is different from traditional broadband grants where payment depends on actual adoption. Space X argues that grant payments shouldn't depend on "the independent purchasing decisions of users," meaning the company receives its full allocation whether 10% or 80% of eligible residents actually purchase service. This dramatically differs from how fiber providers operate under BEAD, where lower adoption can trigger payment clawbacks.

How does Starlink's service quality compare to fiber broadband?

Starlink typically delivers 50-150 Mbps download speeds with 25-50 milliseconds latency, which is adequate for most internet tasks. Fiber commonly delivers 100-1000 Mbps with latency below 10 milliseconds. Both are functional, but fiber offers higher speeds and lower latency. Starlink's advantage is availability—it reaches remote areas fiber can't economically reach. The disadvantage is that satellite service depends on weather conditions and lacks the capacity guarantees fiber provides. Starlink's "dynamic capacity allocation" means speeds can vary unpredictably during peak hours, whereas fiber networks can reserve capacity for specific areas.

Why does Space X refuse to reserve network capacity for subsidized areas?

Space X argues that its satellite constellation operates as a unified network where capacity must be dynamically allocated where demand is greatest. The company contends that reserving large portions of capacity for specific geographic areas would be inefficient and reduce overall system performance. However, this position conflicts with BEAD's goal of guaranteeing reliable service. When Space X doesn't reserve capacity, subsidized areas might experience congestion during peak hours, undermining the broadband reliability the program is meant to ensure. This is a fundamental tension between satellite network operations and traditional broadband service guarantees.

Who is responsible for installing Starlink equipment in BEAD-funded areas?

This is deliberately ambiguous in Space X's proposed terms. The company says it will provide equipment "at no cost" but explicitly disclaims responsibility for correct installation. This suggests customers will handle installation themselves, which is problematic because proper satellite dish alignment requires technical knowledge and clear southern sky exposure. Poor installations result in significantly reduced speeds. Unlike fiber providers who control the entire customer experience, Space X wants to avoid installation liability, potentially creating uneven service quality across the 472,600 funded locations.

Can states refuse Space X's contract terms?

Yes, states have authority to negotiate modified terms or reject Space X's boilerplate entirely. However, Space X has significant leverage because its satellite service is one of few options for remote areas where fiber is economically infeasible. States face a trade-off: accept Space X's minimal commitments or risk losing satellite coverage for underserved areas. So far, states have largely accepted some version of Space X's terms, since the company's $733.5 million allocation indicates broad state participation. Whether any states have rejected specific demands or negotiated harder terms isn't publicly clear, as contract details typically remain confidential.

What labor standards apply to Space X's BEAD deployments?

Space X argues that prevailing wage requirements and contractor standards shouldn't apply because Starlink deployment doesn't employ large numbers of local construction workers. The company claims there are no "identifiable employees, contractors, or contracts being funded" in each state. This is technically true—satellite deployment is capital-intensive but not labor-intensive. However, advocates argue this logic is flawed: if the company is taking federal broadband funding, federal labor standards should apply. The dispute reflects a broader question about what obligations private companies accepting government funding should accept.

How does Amazon's Leo satellite service compare to Starlink under BEAD?

Amazon's Project Leo (formerly Kuiper) is receiving

What happens if Space X underperforms after receiving BEAD grants?

If Space X's contracts include minimal performance guarantees, as the company proposes, legal recourse for underperformance is limited. Clawback mechanisms—which reduce final payment if service quality falls short—are the primary enforcement tool, but Space X is explicitly asking to limit these. Without strong contracts, states and the federal government have few mechanisms to penalize poor performance beyond administrative pressure or threatened exclusion from future funding rounds. This highlights why contract terms matter: robust performance metrics and penalty provisions are the only leverage ensuring accountability.

Will BEAD-funded Starlink service be temporary or permanent?

Starlink service depends on maintaining the satellite constellation in orbit. Space X's Starlink satellites have a design life of approximately 5 years before de-orbiting. This means BEAD-funded service isn't a permanent infrastructure solution like fiber, which lasts 20+ years. If Space X decided to redeploy satellites to other orbits or geographies, service could change. This isn't a flaw with Starlink per se, but it's a fundamental difference from fiber deployment. Communities investing in permanent infrastructure prefer fiber; communities accepting temporary satellite coverage settle for less durable solutions.

What would happen if Congress reexamined BEAD rules again?

If early BEAD satellite deployments prove problematic—poor adoption, quality issues, lack of accountability—Congress could intervene with new regulations. Potential changes might include mandatory performance metrics, capacity guarantees, reporting requirements, and more stringent contract terms. Congress could also rebalance funding between satellite and terrestrial technologies, de-emphasizing satellite if it underperforms or increase satellite funding if it proves effective. The current rules are only three years old, and policy reversals in infrastructure programs aren't unprecedented, though they're politically difficult.

Key Takeaways

- Space X has requested contract terms that would let the company receive $733.5 million in BEAD funding without guaranteeing specific network capacity, performance standards, or subscriber thresholds

- The Trump administration's rewrite of BEAD rules dramatically favored satellite providers, reducing total program spending from 21 billion while opening eligibility to Space X and Amazon

- Traditional fiber BEAD deployments include robust performance metrics, capacity reservations, and adoption-based clawbacks—Space X is requesting exemptions from most of these

- Space X's refusal to handle installation, reserve capacity, or accept labor standards represents a fundamental philosophical difference about what government funding should require

- If Space X's minimal-commitment terms become standard across states, BEAD outcomes will likely be more unpredictable than intended, potentially disadvantaging the rural and low-income populations the program targets

- States retain authority to negotiate harder terms with Space X, but the company's unique satellite assets give it significant leverage in those negotiations

- The dispute reveals broader questions about corporate power in infrastructure policy: when private companies control essential resources, how can government ensure public accountability?

Related Articles

- Tech CEOs on ICE Violence, Democracy, and Trump [2025]

- Europe's Digital Sovereignty Crisis: Breaking Free From US Tech Dominance [2025]

- Golden Dome Missile Shield: How Trade Wars Block Allied Defense Plans [2025]

- Northwood Space Lands 50M Space Force Contract [2026]

- Palantir's ICE Contract: The Ethics of AI in Immigration Enforcement [2025]

- Tech Workers Demand CEO Action on ICE: Corporate Accountability in Crisis [2025]