Iran's Internet Shutdowns: How Regimes Control Information [2025]

When the Iranian government shut down the internet on January 8th, they didn't just flip a switch. They executed a carefully orchestrated plan that had been refined over more than a decade. What followed was the longest internet blackout in Iranian history, a digital darkness that coincided with one of the bloodiest crackdowns in the nation's modern history.

The numbers tell a chilling story. Between 3,000 and 30,000 people were killed during those weeks. Even the lowest estimates, which the Iranian state itself acknowledged, place this among the most severe government-perpetrated violence in recent memory. But here's what haunts researchers and human rights advocates most: the internet shutdown made documenting these crimes exponentially harder. It's not a coincidence. The regime knew exactly what it was doing.

Internet shutdowns aren't crude sledgehammers. They're precision instruments. They're designed to prevent mobilization, stop the spread of video evidence, disrupt coordination among protesters, and create information vacuums that the state can fill with its own narrative. What happened in Iran didn't happen in isolation. It's part of a global trend of digital authoritarianism that's accelerating.

This article dives deep into how internet shutdowns work, why authoritarian governments deploy them, what technology enables them, and how regular people fight back. We'll talk about the history that led to January 8th, the mechanics of how a nation goes dark, the human cost of information blackouts, and the tools and tactics people use to communicate when the internet is gone.

If you're a technologist, a policy person, a journalist, or just someone who cares about what's happening in the world, understanding internet shutdowns matters. They're becoming more common, more sophisticated, and more dangerous.

TL; DR

- Internet shutdowns are weapons: Iran's longest blackout killed thousands while preventing documentation of state violence, showing how digital control enables physical brutality.

- Technology enables authoritarianism: Routers, DNS servers, and fiber optic infrastructure become tools of repression when governments control them.

- Resistance is possible but fragile: VPNs, circumvention tools, and smuggled Starlink terminals allow communication during shutdowns, but they're expensive and risky to use.

- The world is watching: Internet shutdowns in Iran, Myanmar, Sudan, and elsewhere are forcing technologists to build better privacy tools and policymakers to create consequences for digital repression.

- This is accelerating: More countries are adopting internet shutdown capabilities, and the technology is getting cheaper and easier to deploy.

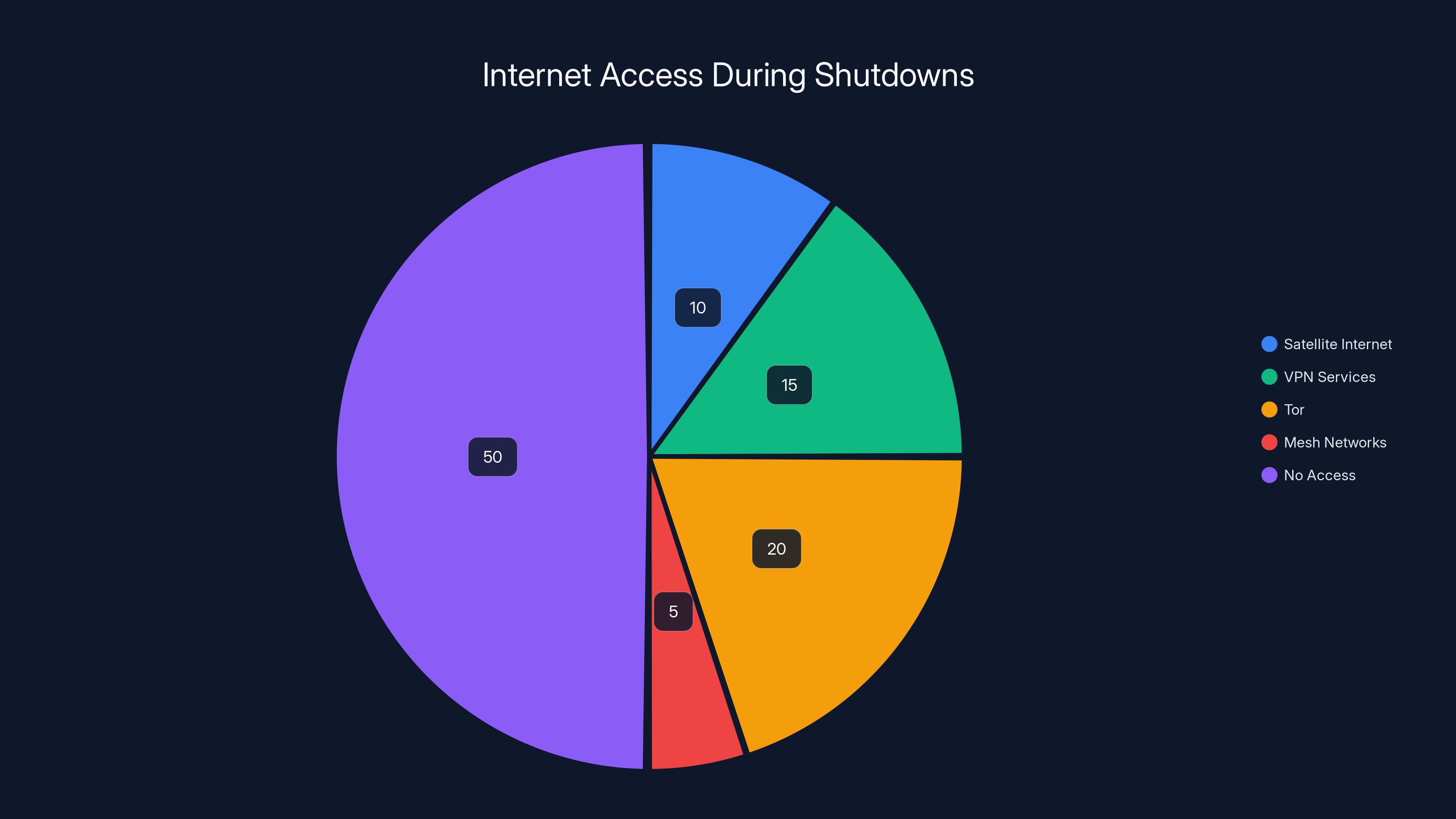

During internet shutdowns, the majority of people (50%) have no access to the internet, while a minority use tools like VPNs, Tor, or satellite internet. Estimated data.

What Is an Internet Shutdown?

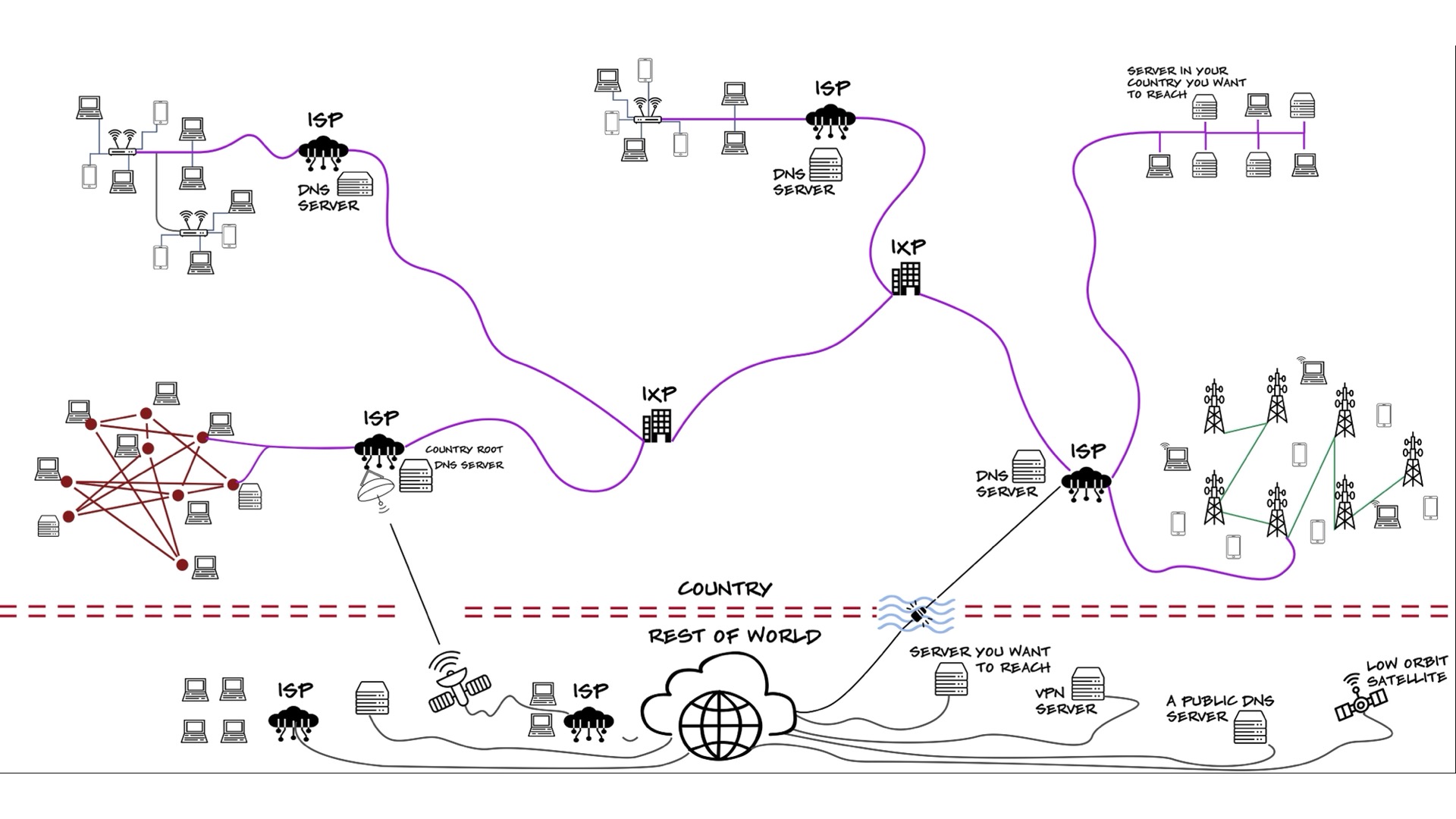

An internet shutdown sounds simple in concept: the government blocks people from accessing the internet. In practice, it's far more complex. It's not like unplugging a cable (though that can be part of it). It's a coordinated attack on multiple layers of internet infrastructure simultaneously.

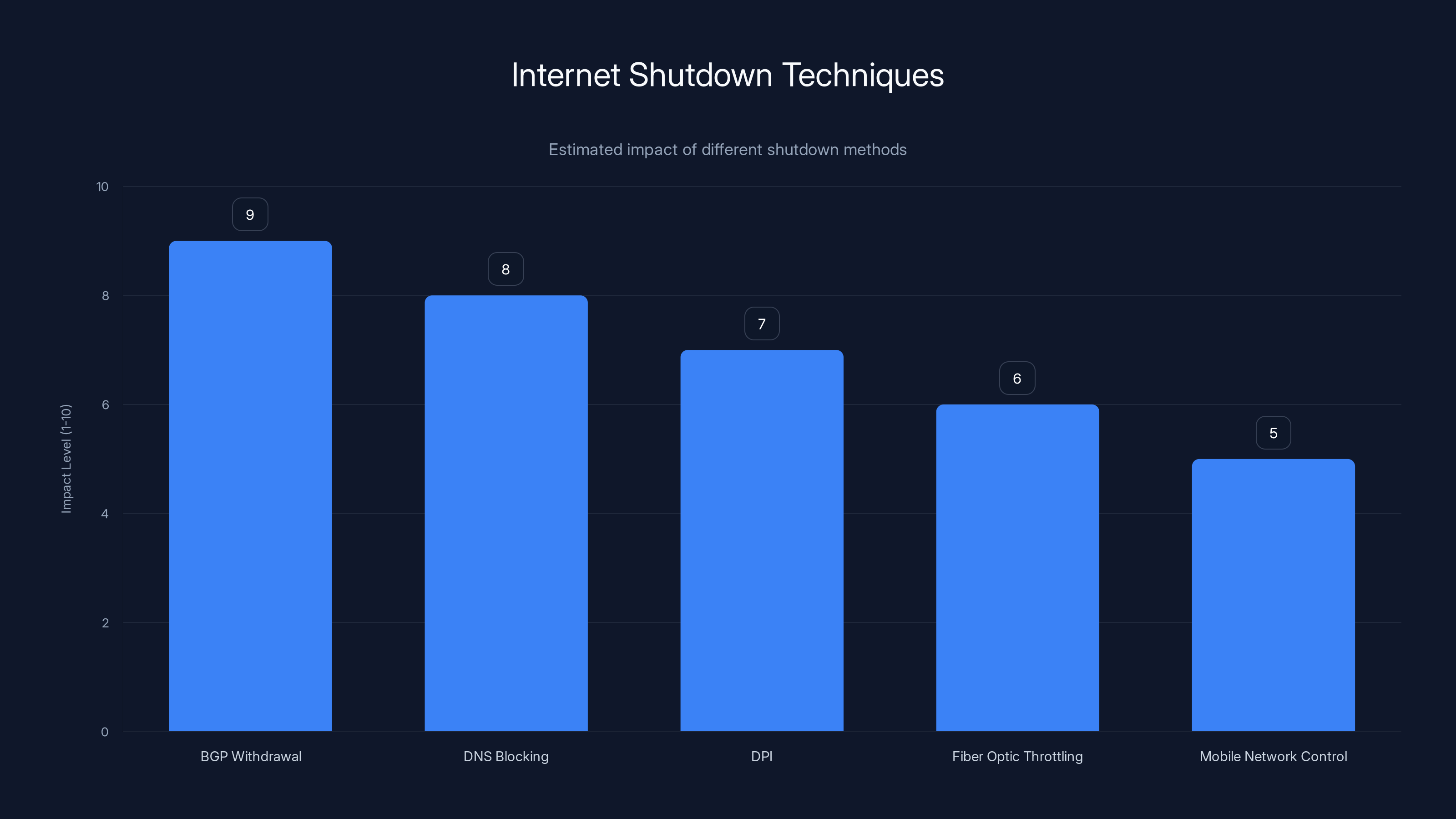

When Iran shut down the internet in January, the government didn't just turn off routers. It blocked BGP (Border Gateway Protocol) announcements, which are the digital instructions that tell the world's internet where Iran's internet is located. It cut off DNS traffic, preventing people from translating website names into IP addresses. It throttled bandwidth on international fiber optic cables. It jammed mobile signals in certain areas. It forced mobile carriers to implement DPI (Deep Packet Inspection), which reads the content of internet traffic to identify and block specific apps.

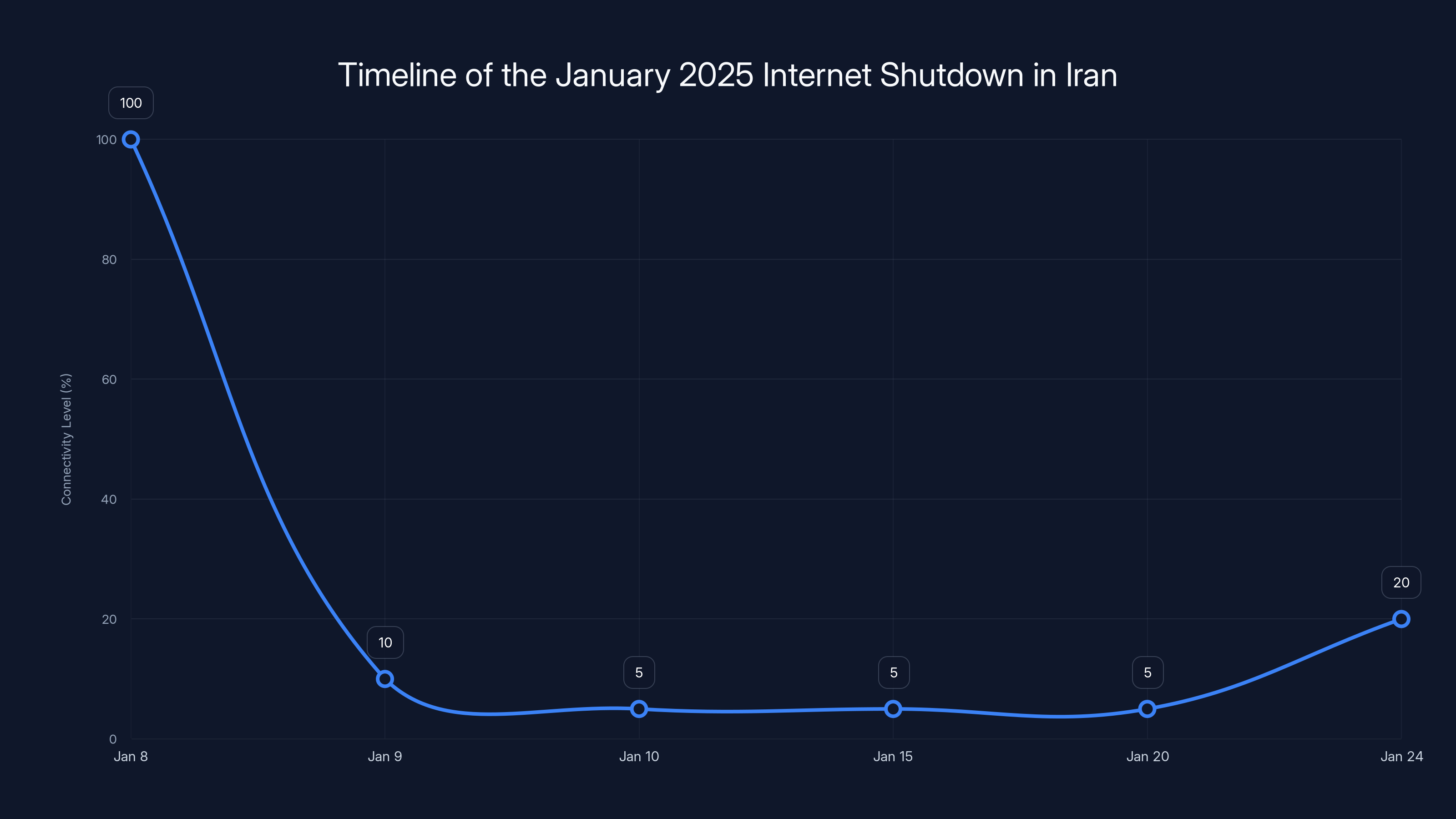

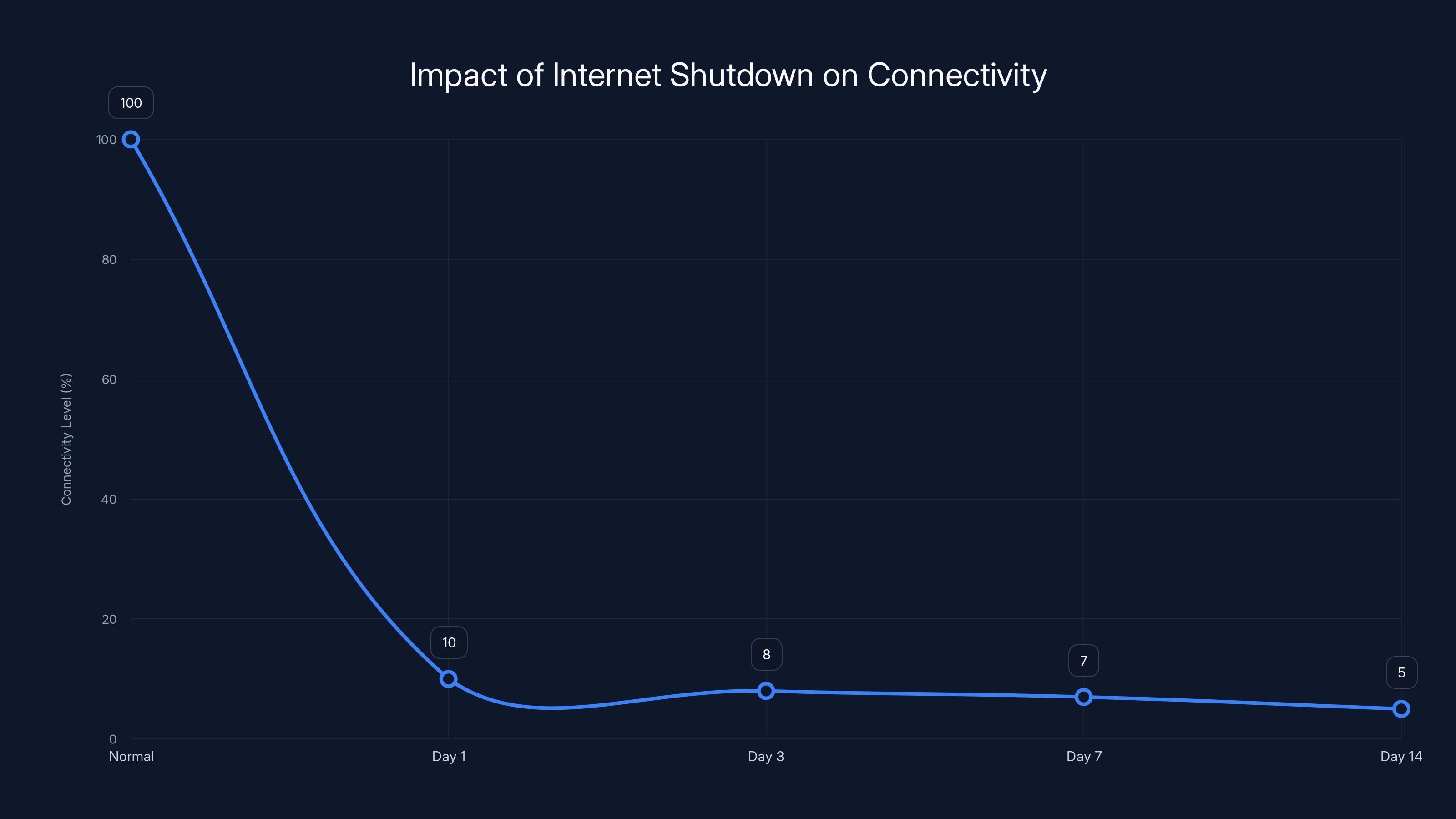

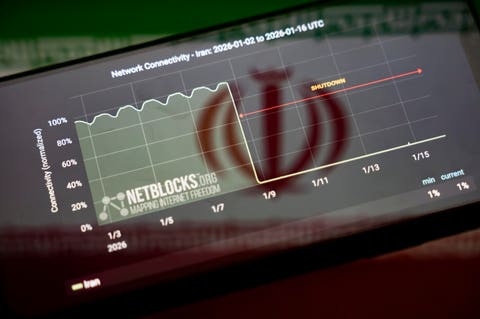

The result isn't complete darkness. Some connectivity typically remains because it's physically difficult to achieve 100% disconnection. But during Iran's January shutdown, connectivity dropped to between 5% and 10% of normal levels. That's enough to cripple most meaningful communication.

The duration matters. A few hours of internet loss can be an accident. A day might be maintenance. But a week-long shutdown is a clear message: we're in control, and we will silence you. Iran's shutdown lasted multiple weeks, making it the longest in the country's history, surpassing even the 2019 shutdown that killed 1,500 people.

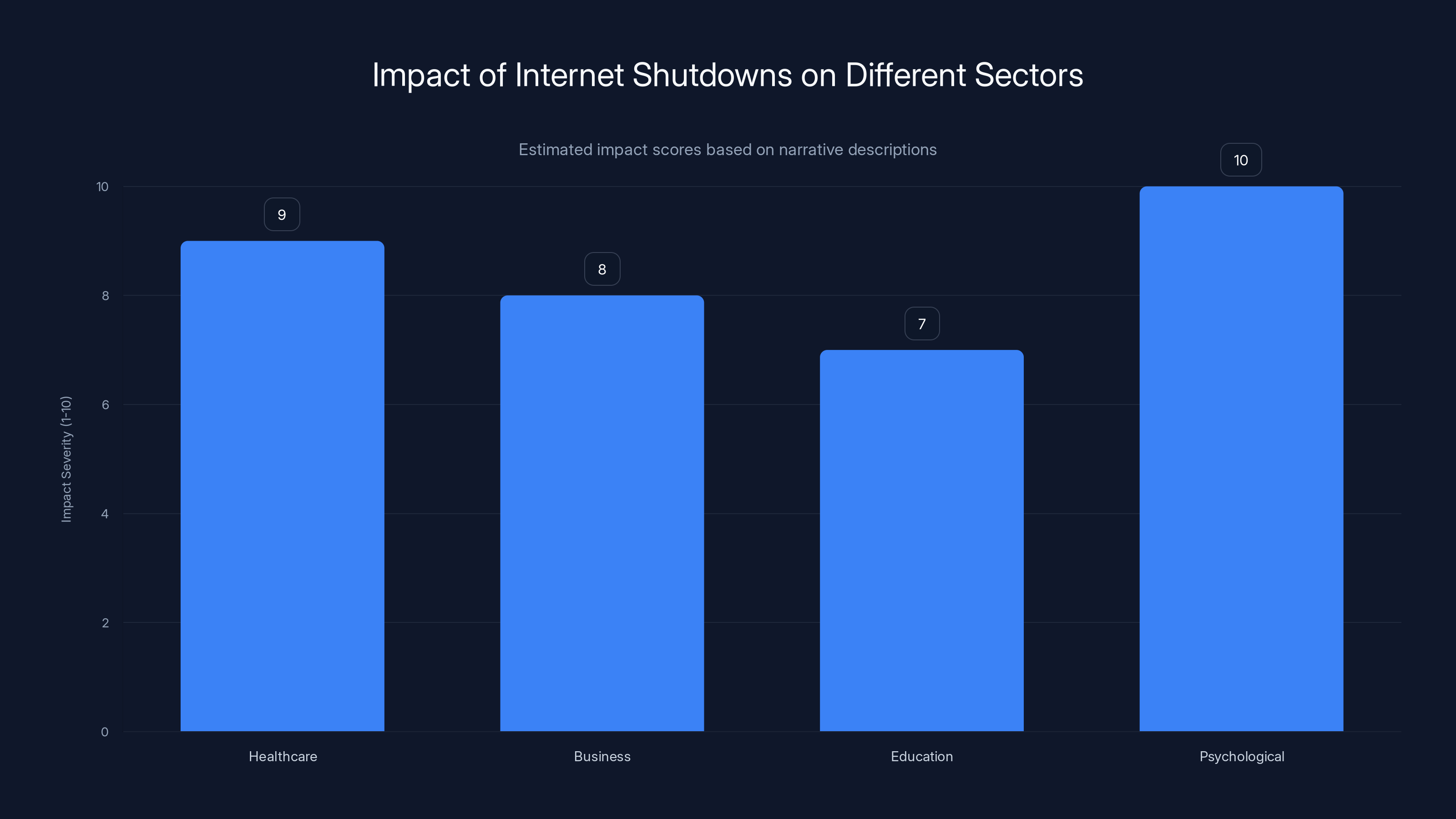

Shutdowns have cascading effects that most people outside the affected country don't fully appreciate. Banks can't process transactions. Hospitals can't access patient records or order medications. Businesses stop operating. Students can't submit assignments. Families separated from each other have no way to communicate. The economic damage is real, measurable, and intentional.

What makes shutdowns particularly effective as tools of repression is their timing. They're almost always deployed precisely when they're most needed: during protests, elections, or other moments of political vulnerability. Governments don't shut down the internet during stable times. They do it when they're afraid.

The History of Digital Control in Iran

Iran didn't wake up one morning and decide to perfect internet shutdowns. This is the result of more than two decades of learning, investment, and technological refinement. Understanding that history is crucial to understanding why the January 2025 shutdown was so devastating.

The relationship between Iran and the internet has always been complicated. When the internet first arrived in Iran in the 1990s, the government recognized both its potential and its threat. It could help Iran participate in the global economy and share Iranian culture with the world. But it could also let Iranians see what was happening outside their borders, share dissenting views, and organize resistance to state authority.

By the early 2000s, Iran had begun building what researchers call a "National Internet," essentially a parallel internet infrastructure that the government could control separately from the global internet. The government required all internet traffic to pass through specific government-controlled chokepoints. This gave them visibility and control over everything flowing in and out of the country.

Then came 2009. During the Green Movement protests, Iranians used the internet to organize, share videos, and broadcast the government's violence to the world. Hundreds of thousands protested. The government's response was violent, but the real lesson they learned wasn't about physical force. It was about the internet. They realized that controlling information flow was as important as controlling physical space.

After 2009, Iran invested heavily in what the government calls "infrastructure independence." The translation is clearer: they wanted to be able to disconnect from the global internet if necessary. They developed domestic alternatives to Whats App, Telegram, and other messaging apps. They built surveillance systems that could monitor internet activity at scale. They trained technologists and security personnel on how to deploy these systems.

The 2019 shutdown was a test run. For seven days during fuel price protests, Iranians experienced near-total internet disconnection. The government's goal was clear: prevent information about the protests from spreading, prevent coordination among protesters, and prevent video evidence from leaving the country. According to estimates, they succeeded in killing 1,500 people during that shutdown.

The trauma of 2019 was profound. People realized that internet access, which had become as essential as electricity, could be taken away. Small communities started experimenting with alternative communication methods. Some families invested in satellite phones. Others started building mesh networks. But most people simply waited, knowing that the shutdown would eventually end and hoping they'd survive until it did.

By January 2025, when protests erupted again, the government had spent six more years perfecting their capabilities. They knew how to shut down the internet faster. They knew how to maintain the shutdown longer. And they knew that shutting it down gave them space to commit violence without documentation.

The January 2025 shutdown in Iran saw a rapid drop in internet connectivity from full access to near-total shutdown within 24 hours, lasting over two weeks with minimal connectivity until January 24th. (Estimated data)

How Internet Shutdowns Actually Work: The Technical Reality

If you want to understand internet shutdowns, you need to understand that the internet isn't a cloud. It's physical infrastructure. Shutdowns target that physical infrastructure at multiple levels simultaneously.

The first layer is BGP, the Border Gateway Protocol. The entire internet is built on a system where networks announce their existence to each other. Iran's internet infrastructure is identified by specific BGP prefixes, essentially digital addresses that say "this is where Iranian internet lives." When the government wants to shut down the internet, one of the first things they do is withdraw those BGP announcements. From the perspective of the rest of the world, Iranian internet ceases to exist.

But that's just the beginning. Inside Iran, people might still be able to communicate locally. So the government moves to the next layer: they block DNS, the system that translates domain names into IP addresses. Without DNS, your browser can't figure out where Google.com is located, even if the connection physically exists. This is sometimes called a "DNS blackhole."

Then comes DPI, Deep Packet Inspection. This technology reads the actual content of internet traffic, not just the addresses. It can identify VPNs by their traffic patterns. It can detect Tor by the distinctive way Tor traffic looks on the network. It can block specific ports and protocols. Some versions are smart enough to detect encryption and block it automatically.

The physical layer is crucial too. International fiber optic cables are the pathways that connect Iran's internet to the rest of the world. These cables are physical objects that can be throttled, blocked, or monitored. During shutdowns, the government can make these international connections so slow that they're essentially useless.

Mobile networks are separate from the fixed internet. So the government controls those separately too. Mobile carriers are government-owned or government-controlled, and they can shut down 3G, 4G, and 5G networks independently of the fixed internet. During the January shutdown, some reports indicated that cellular data was cut off completely in certain areas while partial internet connectivity remained in others.

The sophistication of modern shutdowns means that partial connectivity is often maintained deliberately. Complete total darkness is actually harder to achieve than it sounds. There are redundant systems, backup pathways, and technical complications. By allowing 5-10% connectivity, the government achieves the goal of preventing mass mobilization while making the country seem less completely shut off (which helps with international PR).

What's particularly insidious about modern shutdowns is that they're not crude. They're surgical. The government can target specific geographic regions, specific ISPs, specific types of traffic, or even specific users. They don't have to shut down the entire country. They can shut down just the areas where protests are happening. This is called "surgical blackouts" or "partial shutdowns," and it's becoming more common.

The human cost of these technical measures is enormous. During Iran's shutdown, people couldn't check on family members in other cities. Businesses lost revenue. Hospitals couldn't access records. Schools closed. But none of that was accidental. It's all part of the strategic calculation: the cost of shutting down the internet is worth it if it gives the government space to crack down on dissent without documentation.

Why Authoritarian Regimes Fear the Internet

If you asked an authoritarian leader why they're afraid of the internet, they'd never admit it. They'd talk about security threats, foreign interference, or combating extremism. But researchers who study digital authoritarianism have identified the real reasons, and they're fascinating.

The first reason is documentation. In 1988, Iran executed thousands of political prisoners in what's often called the "Massacre of 1988." It happened without internet, without cell phones, without video. The memory of that massacre was fragmented. People who weren't there didn't fully understand what happened. Peers of researchers working on digital rights in Iran didn't learn about the massacre until they left the country.

Then came the Green Movement in 2009. Suddenly, every smartphone was a potential camera. Every moment of government violence could be recorded, uploaded, and shared with the world before security forces could stop it. The psychological impact was enormous. The Iranian government realized that the days of committing violence in darkness were over. The internet had changed the game.

The second reason is mobilization. The internet doesn't cause revolutions, but it makes organizing them exponentially easier. Before the internet, organizing protests required physical infrastructure: flyers, word of mouth, phone trees, underground meetings. It was slow and vulnerable to infiltration. With the internet, people can coordinate across the entire country in real time. They can share information about where protests are happening, how to respond to police tactics, and where people need help.

The Iranian government isn't stupid. They know that Telegram, Whats App, and other messaging apps are what protesters use to coordinate. They know that Instagram and other platforms are where people share evidence of violence. They know that international platforms are how Iranians outside the country maintain connection with home and pressure foreign governments to take action.

The third reason is harder to quantify but just as important: it's about legitimacy. Authoritarian governments derive authority from the perception that they're in control. When their authority is questioned, they lose power. The internet makes questioning authority trivially easy. You can see what other countries are like. You can read criticism of the government. You can connect with people who share your values but live far away from you. You can find community and strength in numbers, even if that number is digital.

Think about it this way: a government's claim to authority is much stronger when people don't have alternative information sources. If all your information comes from state media, then the state's narrative is the only narrative you know. But if you can access international news, academic papers, and first-person accounts from people experiencing similar oppression, then the state's narrative becomes just one voice among many. That's a threat to regime legitimacy.

The internet also creates what researchers call "structural accountability." When the government commits violence, but people can document it and share it globally, there are consequences. The government's crimes become known. International criticism follows. Sanctions might be imposed. Even if the international community can't directly intervene, the reputational cost is real.

So internet shutdowns aren't irrational fear. They're calculated responses to a real threat. By shutting down the internet, the government creates a information vacuum. Within that vacuum, they can commit violence without documentation. They can control the narrative. They can prevent mobilization. They can restore what they perceive as order.

The tragedy is that this actually works. The 2019 shutdown succeeded in suppressing the protests and killing 1,500 people with minimal international attention. It set a precedent: shutdowns work. So when protests erupted again in January 2025, the government reached for the same tool, confident that it would work again.

The January 2025 Shutdown: What Actually Happened

The timeline is crucial for understanding the January shutdown. On January 8th, protests erupted. Within hours, the government began taking action. By the evening of January 8th, the first internet throttling was noticeable. By January 9th, near-total shutdown was in effect.

The speed was striking. The government had clearly prepared extensively. New equipment had been installed. Personnel had been trained. Protocols had been tested. When the moment came, they executed with precision. Within 24 hours, Iran went from full internet connectivity to near-total darkness.

What made this shutdown different from previous ones was its duration and its sophistication. By the time partial connectivity resumed on January 24th, the shutdown had lasted more than two weeks. That's longer than any previous shutdown in Iranian history. During those weeks, people experienced something that modern people rarely experience: a world without internet.

Reports from inside Iran during the shutdown paint a picture of desperation and creativity. Mobile networks were mostly shut down. Fixed internet was nearly impossible to access. But people found ways to communicate. Landline phones became valuable again. Some neighborhoods experimented with mesh networks using old routers and radio technology. A few people had access to expensive satellite phones that worked with international providers. Some reported that Starlink terminals, smuggled into the country at enormous cost, provided connectivity to small groups.

But here's what's important: these workarounds were available only to a tiny fraction of the population. Most Iranians were simply cut off. They couldn't communicate with family members in other cities. They couldn't access banking services. They couldn't find out what was happening beyond their immediate neighborhood except through word of mouth, rumors, and state media.

While the internet was shut down, the violence continued and escalated. Security forces moved through neighborhoods, arresting protesters. In some cases, the arrests turned into extrajudicial killings. The government later acknowledged 3,000 deaths, but independent estimates suggest the number is far higher, with some researchers putting it at 30,000.

The shutdown created a horrifying asymmetry. The government could see what was happening through its security apparatus and surveillance systems. But the population couldn't see what was happening. Rumors spread. Some people thought the violence was much worse than it actually was (which caused psychological trauma). Others weren't aware of just how bad it was (which made it harder to coordinate resistance).

When partial connectivity began to return on January 24th, the first things people did were predictable: they tried to contact family members to confirm they were alive, they downloaded massive amounts of news and information that had accumulated during the shutdown, and they started uploading video evidence of the violence that had occurred.

But here's the thing that's concerning from a research perspective: the shutdown still worked. Even though communication eventually resumed, the immediate impact of the shutdown was to slow down the spread of information and prevent coordination. The deaths that occurred during those two weeks happened with less documentation than would have occurred if the internet had been accessible. The government achieved its objective, and it paid a price that it considered acceptable.

Internet shutdowns severely impact healthcare, business, education, and cause psychological distress, with psychological impacts rated highest. Estimated data.

The Technology Behind Digital Repression

Internet shutdowns don't happen by accident. They require specific technologies, specific expertise, and specific institutional arrangements. Understanding what those are helps explain why some countries can do shutdowns easily while others struggle.

The first piece of technology is what's called "network architecture." Most countries have redundant internet infrastructure. Multiple companies operate multiple networks. Multiple international cables connect to the country. The internet is designed to be resilient precisely because it's supposed to survive attacks.

But some countries have intentionally designed their internet architecture to be more centralized. Iran is one of them. The government required all international internet traffic to pass through government-controlled gateways. This means that instead of having dozens of independent internet service providers all connecting independently to the global internet, most of Iran's internet traffic flows through a small number of government-controlled chokepoints. This makes shutdowns technically feasible.

China has taken this even further. The Great Firewall isn't a single firewall—it's an entire architecture where the government can monitor and block traffic at multiple points. China's internet is designed from the ground up for government control. But China is unique. Most countries' internet grew organically without government control baked into the foundation.

The second piece of technology is DPI (Deep Packet Inspection) and other traffic analysis tools. These are commercial products that can be purchased from companies like Sandvine or acquired through state intelligence partnerships. DPI systems can identify VPNs, Tor traffic, specific messaging apps, and encrypted communications. They can block traffic based on patterns, not just on explicit rules.

Some DPI systems are sophisticated enough to detect encrypted traffic that's trying to evade them. For example, a smart DPI system can detect VPN traffic by looking at characteristics like timing, packet sizes, and entropy patterns, even if the actual content of the VPN tunnel is encrypted and invisible.

The third piece is the infrastructure for managing these systems. You need network operations centers where engineers monitor internet traffic. You need personnel trained on how to deploy shutdowns and maintain connectivity during a shutdown (governments usually keep certain connections open for government operations). You need coordination between different government agencies and private companies that operate internet infrastructure.

Iran has invested in all of this. The Revolutionary Guards operate their own internet service provider. The Ministry of Information and Communications Technology oversees internet regulation. Various government and intelligence agencies have their own surveillance and control infrastructure. This is a massive government investment, and it's paid off in the form of demonstrated shutdown capability.

What's concerning from a global perspective is that this technology is becoming cheaper and more accessible. Smaller countries that previously lacked the technical expertise to shut down their internet now can purchase turnkey solutions from companies that specialize in this. Some researchers have documented DPI equipment purchases by countries in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East.

There's also evidence that countries are learning from each other. After Iran deployed shutdowns, other countries started doing it too. When Myanmar shut down the internet during political turmoil, they used tactics that closely resembled Iran's approach. When Sudan shut down the internet, the pattern was similar. Countries are sharing technical knowledge about how to implement shutdowns.

One technology that countries are particularly afraid of is Tor. Tor routes internet traffic through multiple nodes, making it extremely difficult to trace or block. A user in Iran using Tor can access the global internet in a way that's much harder for the government to detect or block compared to a conventional VPN. Some countries have started using techniques to detect Tor traffic based on behavioral patterns, but Tor continues to evolve to counter these detection methods.

Starlink and other satellite internet services present a new challenge for governments that want to maintain shutdowns. These services bypass the traditional internet infrastructure that governments can control. They connect directly to satellites. But there's a catch: satellite internet services are expensive, require visible antennas, and can be jammed using RF (radio frequency) jamming equipment. So they're a circumvention tool for people with resources, not a universal solution.

The Human Cost: Lives, Livelihoods, and Psychological Impact

When we talk about internet shutdowns as an abstract policy issue, it's easy to miss the human reality. For people living through a shutdown, it's not a technical problem. It's a crisis.

Consider what a shutdown does to a hospital. Medical records are stored in computers. Pharmacies rely on computer systems to track medications. Labs rely on computer systems to record and communicate test results. When the internet is shut down, these systems either go offline or operate in severely degraded mode. Patients die because of communication failures that wouldn't happen in normal circumstances.

Consider what it does to a business. Most modern businesses rely on internet connectivity. They can't process payments. They can't access their records. They can't communicate with customers or suppliers. A two-week shutdown costs enormous amounts of money. Small businesses sometimes go bankrupt from the cumulative impact of multiple shutdowns.

Consider what it does to education. Students can't submit assignments. Teachers can't access lesson plans. Universities can't process registrations. The ripple effects of an extended shutdown can set back an entire generation's education by weeks or months.

But the most serious impact during the January shutdown was psychological and social. Imagine not being able to contact your family for two weeks. Imagine not knowing if people you care about are alive. Imagine living in a neighborhood where police and security forces are moving through the streets, and you can't get information about what's happening, whether it's safe to go outside, or where help is available.

People experienced this. Reports from inside Iran during the shutdown documented extraordinary anxiety and fear. Some people didn't sleep for days. Some experienced what medical professionals would recognize as acute stress disorder. Families were separated. In some cases, people went for weeks not knowing whether relatives had been arrested or killed.

The government weaponized this anxiety. The psychological impact of the shutdown—the uncertainty, the fear, the isolation—was as much a tool of repression as the physical violence. The shutdown made it psychologically harder for people to resist. It fractured communities. It created despair.

There's also a generational aspect to shutdowns that's worth noting. Younger people have never lived without internet. For them, an internet shutdown isn't just an inconvenience—it's a total rupture of the world as they know it. Some people reported panic attacks during the first few days of the January shutdown. The psychological adaptation to functioning without internet took time for many people.

The economic costs are staggering. Some estimates suggest that the January 2025 shutdown cost Iran's economy somewhere between

But the government calculated that the cost was worth paying if it achieved the objective of suppressing the protests. This is the cold calculus of authoritarian rule: the cost to the population of a shutdown is acceptable if it increases the government's ability to maintain power.

Circumvention Tools: VPNs, Tor, and Other Workarounds

The moment governments started blocking internet access, people started finding ways around it. The arms race between circumvention tools and government blocking technologies is one of the most important technological competitions happening globally.

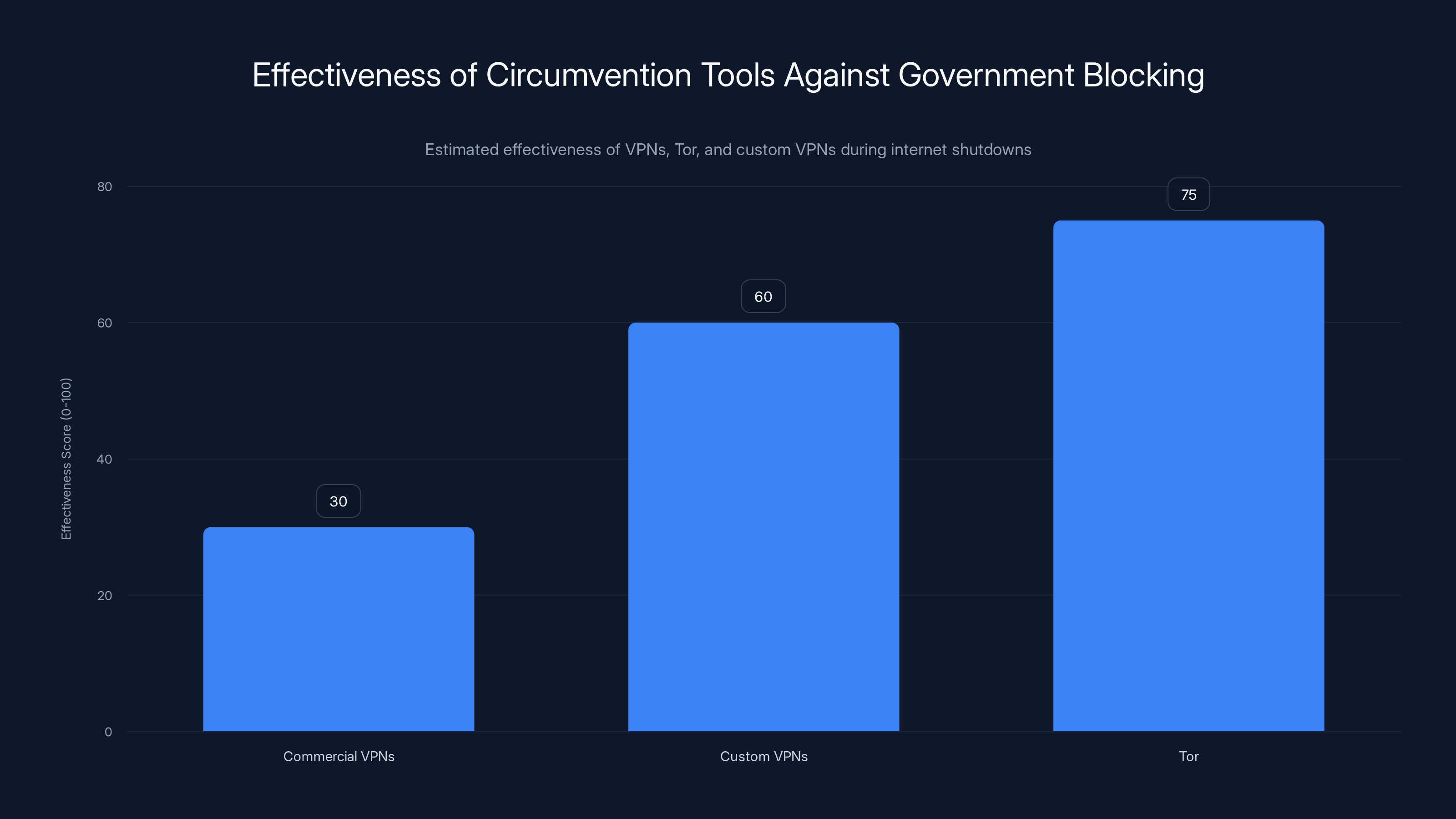

VPNs (Virtual Private Networks) are the most well-known circumvention tool. In normal circumstances, a VPN is a tool for privacy—it encrypts your traffic and routes it through a server operated by the VPN company, so your internet service provider can't see what you're doing. But during a shutdown, a VPN becomes a tool for accessing the internet when your government is blocking it.

Here's why: when you use a VPN, your traffic is encrypted and routed to a VPN server outside the country. From the government's perspective, it just looks like you're connecting to a single IP address (the VPN server), and they can't see what that connection is carrying. If the VPN server is outside the country, the government can't access it to shut it down.

But governments have gotten smarter about blocking VPNs. During the January shutdown, most commercial VPN services stopped working within hours. The government's DPI systems recognized the traffic patterns characteristic of VPNs and blocked them. Some individuals reported that less popular VPN services, particularly custom-configured VPNs, continued working for a few days before being blocked.

Tor is theoretically more resistant to government blocking. Tor splits your traffic among thousands of nodes, making it much harder to block based on traffic patterns alone. But Tor isn't perfect. Detecting Tor requires more sophisticated techniques than detecting VPNs, but it's becoming increasingly possible. Some research suggests that governments can identify Tor traffic with reasonable accuracy by analyzing traffic patterns, even though they can't see the content.

During the January shutdown, some reports suggested that Tor traffic was blocked, though less consistently than VPN traffic. This could mean that the government's systems struggled to identify and block all Tor traffic, or it could mean that the government was being somewhat more lenient with Tor traffic (for reasons not fully clear).

Mesh networks are a different approach. Instead of trying to connect to the internet through the government's infrastructure, people can create their own local networks using Wi-Fi routers and other equipment. These networks can be used to share files, send messages, and coordinate locally without needing to access the global internet.

Some people in Iran during the shutdown tried to set up mesh networks. The challenge is that they require technical expertise and hardware. Most people don't have the knowledge or equipment to set up a functional mesh network. And mesh networks are vulnerable to government intervention: if the government knows about them, they can be dismantled.

Satellite internet is the most reliable circumvention tool, but it's available only to people with significant financial resources. Starlink terminals can provide high-speed internet connectivity regardless of what the government does to terrestrial infrastructure. But a Starlink terminal costs around $600 globally and much more on the black market. That's far beyond what most Iranians can afford.

There's also evidence that governments are preparing countermeasures against satellite internet. RF (radio frequency) jamming equipment can interfere with satellite signals, though jamming is crude and might interfere with other radio services. Some governments are considering regulations that would make possessing satellite internet equipment illegal.

The circumvention arms race is important because it shows that shutdowns aren't absolute. People will always find ways to communicate. But the sophistication of blocking technologies means that circumvention is becoming harder for ordinary people. It's moving toward being something available only to people with technical expertise or financial resources.

Estimated data shows that Tor is generally more effective than commercial VPNs during government-imposed internet shutdowns, with custom VPNs offering moderate success.

International Response and Policy Implications

When Iran shut down the internet in January, the international community was watching, but there was limited ability to directly intervene. Internet shutdowns are a domestic policy issue—they happen within a country's borders, using infrastructure that the country controls.

But there's been growing international attention to internet shutdowns as a human rights issue. The United Nations has issued statements calling internet shutdowns a violation of freedom of expression rights. Human rights organizations have documented shutdowns in dozens of countries. There's increasing conversation about how the international community should respond.

One approach is sanctions. Some countries and international bodies have imposed economic sanctions on countries that conduct shutdowns, including Iran. The logic is that creating a cost for shutdown behavior makes it less attractive. But sanctions are blunt instruments, and they often harm ordinary citizens more than government officials.

Another approach is technology transfer and support for circumvention tools. Western governments and civil society organizations have funded the development of VPN services, Tor nodes, and other circumvention tools that are made available to people in countries with internet restrictions. But this approach has limitations—governments continue to get better at blocking these tools, and there's only so much that circumvention tools can do against determined government blocking.

A third approach is to pressure technology companies. Companies that manufacture DPI equipment or other surveillance tools have been criticized for enabling human rights abuses. Some governments have restricted the export of surveillance technologies to countries with poor human rights records. But enforcement is spotty, and companies sometimes find ways around these restrictions.

A fourth approach is to support independent ISPs and decentralized internet infrastructure. If internet infrastructure were more decentralized—with many independent providers operating independently rather than through government chokepoints—shutdowns would be harder to implement. But governments have strong incentives to maintain control over internet infrastructure, so this approach faces practical obstacles.

Perhaps the most important international response is documentation and accountability. Human rights organizations have been documenting the January shutdown, the violence that occurred during it, and the government's responsibility for both. This documentation serves multiple purposes: it provides evidence for potential future legal proceedings (though jurisdiction issues are complex), it creates a historical record, and it maintains international attention on the issue.

There's also growing conversation about whether companies that provide cloud services, social media platforms, and other internet services have responsibility when their platforms are used by governments to conduct surveillance or to coordinate violence. During the January shutdown, the government used Whats App and Telegram data (from before the shutdown and from the partial connectivity period) to identify protesters. Some argue that technology companies should have responsibility for how their platforms are used in such contexts.

The challenge is that technology companies argue (with some justification) that they can't control how their tools are used by governments. They don't want to be responsible for government actions. But there's increasing pressure on them to consider these questions: Should they provide content about how to use circumvention tools? Should they cooperate with governments that are conducting shutdowns? Should they support the development of tools that make shutdowns harder?

These are difficult questions without clear answers. But they're becoming increasingly important as shutdowns become more common globally.

The 2009 Green Movement: The Precedent

To really understand the January 2025 shutdown, you need to understand what happened in 2009. The Green Movement was Iran's most serious challenge to government authority in decades. Hundreds of thousands of people protested. And the internet played a role.

During 2009, the government did conduct some internet restrictions, but they weren't comprehensive. The internet remained mostly accessible throughout the protests. This allowed information to flow: video of government violence was shared globally, international attention was maintained, and protesters could coordinate.

The government's response was violent—they killed hundreds of people—but from the government's perspective, the result was unsatisfactory. The violence became known internationally. The government's actions were documented. The world was watching. And despite the violence, the protests continued for months.

This was the moment when the Iranian government learned a crucial lesson: the internet was a threat to their ability to maintain control. If they could shut down the internet, they could commit violence without documentation. They could prevent coordination among protesters. They could control the information flow.

So after 2009, the government invested massively in shutting down the internet quickly and maintaining the shutdown for extended periods. The 2019 test shutdown gave them confidence that the approach worked. And by January 2025, they were ready to implement it at scale.

The comparison between 2009 and 2025 is instructive. In 2009, with internet access, protests lasted months. In 2025, with the internet shut down, the government was able to conduct massive violence relatively quickly, and the international attention was significantly lower. The government's strategic calculation appeared to be correct: shutdowns work.

But there's a complication. Even during the 2025 shutdown, some information leaked out. Smuggled Starlink terminals provided some people with internet access. Some international journalists were present and reported what they witnessed. Refugees and diaspora Iranians tried to piece together information from leaked documents and secondhand reports.

Moreover, when the internet came back online, it came back all at once. People started uploading massive amounts of video evidence and documentation. The accumulation of evidence from the shutdown period eventually became available. But the immediate impact of the shutdown—preventing real-time documentation and coordination—succeeded.

The lesson for other authoritarian governments watching Iran is clear: internet shutdowns work if you're willing to pay the cost. The cost in terms of economy impact, international criticism, and domestic resentment is significant, but from the perspective of a government willing to commit large-scale violence, it's an acceptable cost if it achieves the objective of maintaining power.

The Role of Disinformation During Shutdowns

One of the most insidious aspects of internet shutdowns is that they create information vacuums, and nature abhors a vacuum. During the January shutdown, rumors spread. Some were merely false. Some were deliberately planted by the government.

Without internet access, information had to flow through word of mouth, limited media that the government controlled, and whisper networks. In this environment, misinformation thrives. Someone might hear from a friend of a friend that protesters had taken over a government building. That rumor might spread widely even though it was false.

The government actively exploited this. State media reported narratives that served government interests. Because people had limited access to other information sources, these narratives had more credibility than they would have if people could fact-check them against international news sources.

This is an underappreciated aspect of why shutdowns are so effective as tools of repression. It's not just that they prevent coordination and documentation. They also degrade the information environment. People are left with uncertainty, rumor, and government propaganda. This uncertainty itself is a tool of control.

There's also evidence that the government deliberately spread misinformation during the shutdown. For example, there were rumors that the government had given security forces shoot-on-sight orders. Whether those orders actually existed is unclear, but the rumor created fear and discouraged people from protesting or moving through public spaces.

The psychology of information vacuums is important. When people lack information, they fill the gaps with speculation, fear, and assumptions based on their previous experience. If the government has previously used violence, people assume that current government actions are violent. If rumors suggest that the military has been deployed, people assume the worst. The psychological impact of uncertainty can be as severe as the impact of confirmed bad news.

The chart estimates the impact level of different internet shutdown techniques, with BGP withdrawal having the highest impact. Estimated data.

Alternative Communication Methods and Community Organizing

When the internet shut down, people had to find alternative ways to communicate. Some of these methods were high-tech. Others were astonishingly low-tech.

Landline phones remained functional in some areas, though not all. These became precious resources. Families would queue to use a public phone to contact relatives in other cities. Some people rationed their calls because landline service was intermittent and they didn't know when the next opportunity to call would come.

Some neighborhoods organized informal communication networks. Word would spread through trusted messengers about what was happening, where people should avoid, and where help was available. These networks were reminiscent of pre-internet communication methods, adapted to the modern context.

Some people used amateur radio to communicate across long distances. Amateur radio operators in different cities could relay messages. This method was limited in reach but provided a communication pathway that the government couldn't easily shut down.

There were also creative uses of technology. Some people modified old routers to create mesh networks. Some people used battery-powered radios. Some people used cell phones even though cellular data wasn't available, using whatever limited Wi-Fi or landline connectivity remained to send messages.

But here's what's important: these alternative communication methods had severe limitations. They weren't accessible to everyone. They required technical knowledge or access to resources that many people didn't have. They were slower and less reliable than internet-based communication. They weren't well-suited for organizing at scale.

The experience during the January shutdown showed that while alternative communication methods are better than nothing, they're not substitutes for internet connectivity. They can help maintain local communities, but they can't enable national coordination. This is why shutdowns are so effective at suppressing mass movements: they prevent the kind of large-scale coordination that national protests require.

Lessons for Other Countries and Regions

The question that should concern people globally is: will other countries follow Iran's example? The answer appears to be yes, and it's already happening.

Myanmar's military shut down the internet during the coup in February 2021. Sudan shut down the internet during political turmoil. Belarus conducted selective shutdowns during protests in 2020. China has conducted targeted shutdowns in regions where it's suppressing dissent. These cases suggest that shutdowns are becoming a standard tool in the authoritarian playbook.

What's particularly concerning is that the technology and knowledge required to conduct shutdowns is becoming more widely available. Smaller countries that previously lacked the technical capability can now purchase turnkey solutions from surveillance companies. The expertise is being shared through informal networks of authoritarian governments.

But there's also been counter-innovation. Circumvention tool developers have been working on technologies that are harder to block. Projects like Bridgefy (an app that uses mesh networking over Bluetooth and Wi-Fi to maintain communication when internet is unavailable), Signal's server protocol improvements, and various Tor enhancements represent efforts to make communication more resilient to government blocking.

The fundamental question is whether decentralization can outpace centralization. Can technology developers create systems that are fundamentally harder to shut down? Or will government surveillance and control technology continue to advance faster?

The honest answer is that this is an open question. Technology companies are working on the problem, but governments have more resources and more motivation. As shutdowns become more common, the stakes of this competition increase.

For civil society organizations, the lesson is that shutdowns should be anticipated and planned for. Organizations working in countries where shutdowns are possible should develop protocols for how to operate without internet access. They should build redundancy into their communication systems. They should invest in training people to use circumvention tools.

For governments that value human rights and internet freedom, the lesson is that there needs to be a coordinated international response to shutdowns. This might include sanctions, restrictions on surveillance technology exports, support for circumvention tools, and documentation efforts to create accountability.

The Future of Digital Repression and Resistance

Looking forward, several trends seem likely to shape the future of internet shutdowns and circumvention.

First, shutdowns will probably become more common. As governments see that shutdowns work (or at least, that the benefits outweigh the costs), more governments will adopt this tool. Shutdowns are becoming normalized as a response to political instability.

Second, shutdowns will become more sophisticated. Governments are learning from each other. Future shutdowns might be more precisely targeted (affecting only specific geographic areas or specific apps), more quickly deployed (shutting down the internet in hours rather than days), and harder to circumvent (using improved DPI and other blocking technologies).

Third, the balance of power between governments and circumvention tools will likely continue to shift. Right now, governments are somewhat ahead—most commercial VPNs can be blocked relatively easily. But circumvention tool developers are working on more sophisticated approaches. Decentralized networks, steganography (hiding information within other data), and other advanced techniques might make circumvention harder for governments to block.

Fourth, satellite internet will become more important. As more people have access to Starlink and similar services, governments will face a new challenge: terrestrial shutdowns won't work if people have satellite connectivity. Some governments are already preparing countermeasures (like RF jamming), but these countermeasures have limitations.

Fifth, there will be more international attention to the issue. The documentation of shutdowns in Iran, Myanmar, Sudan, and elsewhere is creating awareness. International bodies are increasingly recognizing shutdowns as a human rights issue. This might create pressure on governments to refrain from shutdowns or at least to limit their scope.

The most likely scenario is an ongoing arms race. Governments will develop new blocking technologies. Circumvention tool developers will find workarounds. Governments will develop countermeasures to the workarounds. This competition will continue, with the outcome uncertain.

But what's certain is that internet shutdowns represent a fundamental threat to information freedom and human rights. They're not just technical problems. They're political problems that affect real people's lives.

During Iran's January shutdown, connectivity dropped significantly, reaching as low as 5% of normal levels over two weeks. Estimated data.

What We Know About Government Surveillance During Shutdowns

One crucial aspect of shutdowns that deserves more attention is what governments do with the data they collect before, during, and after shutdowns.

Governments have comprehensive surveillance systems that monitor internet traffic even during normal times. These systems create detailed records of who accessed what online, who communicated with whom, and what information was shared. During a shutdown, this surveillance infrastructure doesn't disappear—in fact, it becomes more important.

During the January shutdown, evidence suggests that the government used previously collected data about internet usage patterns to identify activists. If the government had previously observed that someone was accessing protest-related content or activist websites, they had a list of suspects. Once the internet came back on and people started uploading video evidence, the government had another window to collect data about who was accessing, sharing, or distributing that content.

This is a surveillance feedback loop: the government uses data collected during normal times to identify suspects, then uses shutdowns to create space to act against those suspects, then uses surveillance of the post-shutdown period to identify others.

The implication is that internet privacy becomes even more important in countries where shutdowns are possible. If you're not sure whether the government is monitoring your internet activity, you should assume it is. Using end-to-end encrypted messaging apps, being careful about what you search for, and being aware of your digital footprint become not just privacy concerns but potential safety concerns.

Some activists have developed protocols for digital security during times of political instability. These include: using separate devices for sensitive communications, regularly deleting message history, using temporary email addresses, and being aware of what information they're revealing through metadata (even if the content of their communications is encrypted).

But these protocols are defensive measures. They're ways to minimize risk, not ways to eliminate it. The fundamental problem remains: if governments are willing to shut down the internet and conduct violence, individual digital security measures provide only limited protection.

The Role of International Journalists and Human Rights Monitors

One of the challenges in documenting shutdowns is that international journalists and human rights monitors face significant difficulties. They can't easily enter countries experiencing shutdowns. If they're already in the country, they might be detained. Their communications might be monitored.

During the January shutdown, there were international journalists in Iran, but they faced extreme restrictions. Some were detained. Others left the country because of safety concerns. The journalists who remained were limited in what they could report because they themselves didn't have reliable internet access.

This creates an asymmetry: the government is conducting violence, but the people with the most credibility to document that violence internationally (professional journalists) are prevented from doing so. Citizen journalists inside the country can document the violence, but their reports lack the institutional credibility that international news organizations have.

Some international media organizations have worked around this by collecting reports and video from citizen journalists, fact-checking them, and then publishing them under the news organization's byline. This provides a middle ground: the credibility of an international news organization with the on-the-ground reporting of citizen journalists.

But this approach has limitations. Not all citizen reports can be fact-checked. Some video might be from the wrong location or the wrong time. The speed of events during shutdowns makes thorough fact-checking difficult.

Human rights organizations have also been active in documenting shutdowns and their effects. Organizations like Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and others have issued statements, filed reports, and attempted to document the human toll of shutdowns. But their access is also limited. They rely on interviews with refugees, diaspora members, and international contacts inside the country.

The challenge is that the most important period for documentation—when the violence is actually occurring—is precisely when documentation is most difficult because the internet is shut down.

Case Study: Comparing Shutdowns Across Countries

Looking at shutdowns in different countries shows how the tactics and technology vary based on the country's specific circumstances.

Iran's shutdowns are comprehensive and coordinated by the state. The government has invested heavily in shutdown technology and has proven capability to execute shutdowns quickly. The shutdowns are long-lasting (weeks, not days) and are coordinated with specific violence.

China's approach is different. Rather than complete shutdowns, China conducts selective blocking. Certain services are blocked (like Twitter, You Tube, Facebook) while others (like domestic services) remain available. This gives the appearance of internet access while actually preventing international communication and access to foreign news sources.

Myanmar's shutdowns were somewhat less organized initially, but the military government has been learning and improving their capability. The shutdowns conducted in 2021 and subsequent years have become more sophisticated.

Sudan's shutdowns were relatively crude—essentially just disconnecting international connectivity. But they were effective at preventing the spread of information about events in the country.

These case studies suggest that the "optimal" shutdown strategy (from an authoritarian government's perspective) involves: rapid deployment, comprehensive blocking of international connectivity, sophisticated DPI to block circumvention tools, and careful communication control to limit information about what's happening during the shutdown.

Countries are learning from each other. The technology, tactics, and timing that worked in Iran are being studied and potentially adapted in other countries.

Building Resilient Infrastructure for the Future

Given that shutdowns are likely to become more common, researchers and technologists are working on how to build more resilient internet infrastructure.

One approach is mesh networking. If internet connectivity were decentralized through mesh networks, it would be much harder for a government to achieve a complete shutdown. Instead of shutting down a few central gateways, they'd have to shut down thousands of individual nodes. But mesh networks require significant technical infrastructure and user adoption to be viable at scale.

Another approach is satellite internet. As satellite internet becomes more affordable and widespread, it becomes harder for governments to achieve complete shutdowns. But governments are preparing countermeasures, and satellite terminals can be jammed or made illegal.

A third approach is community networks. Some communities are experimenting with building their own internet infrastructure that's independent of government control. These networks are small-scale and might not provide the bandwidth of the global internet, but they could maintain local communication and information sharing.

A fourth approach is cryptographic resilience. Tools that can function even with severely degraded connectivity, that work without continuous internet access, and that provide encryption-by-default become more important in environments where shutdowns are possible.

Some researchers are working on technologies that could enable communication even when the internet is shut down. These include steganographic techniques (hiding information in plain sight), using smartphone hardware for local communication, and using clever protocols that work over intermittent connectivity.

But here's what's honest: most of these approaches are ahead of their technical maturity. They show promise, but they're not ready to be deployed at scale. The infrastructure that would make shutdowns truly difficult to implement doesn't exist yet.

The reality is that we're in a race. Governments are improving their shutdown capabilities. Technology developers are working on more resilient systems. The outcome is genuinely uncertain.

The Broader Implications for Digital Rights

Internet shutdowns are one manifestation of a broader challenge: digital authoritarianism. Shutdowns are the most extreme form, but governments also conduct surveillance, blocking of specific content, throttling of particular apps, and many other forms of digital control.

What's concerning is that the technology that enables shutdowns is the same technology that enables pervasive surveillance. The DPI systems that can block VPNs can also monitor all internet traffic. The infrastructure that can shut down the internet can also control it.

This means that even if governments don't conduct complete shutdowns, the underlying capability creates a constant threat. People living in countries with internet shutdowns live with the knowledge that the government could shut down the internet at any moment. This affects behavior—people might self-censor, might avoid certain topics, might refrain from expressing dissent online.

Some researchers call this the "chilling effect" of shutdowns: the threat of shutdowns changes people's behavior even when shutdowns aren't actually occurring.

The January shutdown in Iran had this effect. Even after the internet came back online, there were reports that people were more cautious about their online activities, knowing that the government had demonstrated its willingness and capability to shut down connectivity.

From a human rights perspective, this is concerning. Digital freedom is increasingly understood as a component of human rights. The ability to express yourself online, to access information, and to communicate freely are understood as important rights in the modern world.

Internet shutdowns violate these rights in the most direct way possible. They remove the ability to communicate or access information online entirely.

What Happened After: The Return to Partial Connectivity

On January 24th, after more than two weeks of near-total shutdown, partial connectivity began to return to Iran. This wasn't a sudden restoration of full internet service. It was a gradual, uneven process where some areas got connectivity while others remained dark, and some services became available while others remained blocked.

The return to connectivity was explosive. Within hours, thousands of people were uploading videos, photos, and text documenting the violence they'd witnessed or heard about. The accumulated backlog of information that people wanted to share came rushing online.

But here's the complication: by then, the immediate threat of real-time documentation during ongoing violence had passed. The violence had already occurred. The government's immediate goal—preventing live documentation of the worst of the crackdown—had been achieved.

What the return to connectivity did provide was after-action documentation. Videos, photos, and testimony about what had happened during the shutdown began to circulate. International media could finally report comprehensively on what had occurred. Civil society organizations could conduct preliminary investigations.

But the advantage had been with the government. They'd had two weeks of relative darkness to conduct violence. They'd had two weeks to arrest suspected activists. They'd had two weeks to eliminate evidence. When the internet came back, the most critical period for documentation had already passed.

The partial connectivity that returned was also carefully managed. Some services remained blocked. The bandwidth available to international traffic remained limited. The government maintained surveillance of who was accessing what content. It wasn't a complete return to normal internet freedom—it was a partial restoration that still served government interests.

The experience after the January shutdown showed that even partial connectivity is valuable. It allows for some documentation, some coordination, and some information sharing. But it also showed that the critical time for documentation is during the shutdown itself, not after.

FAQ

What exactly is an internet shutdown?

An internet shutdown is when a government blocks or severely restricts access to the internet, typically by blocking BGP announcements, DNS resolution, cutting international fiber optic cables, and implementing Deep Packet Inspection to block circumvention tools like VPNs and Tor. Unlike temporary outages, shutdowns are intentional government actions deployed during times of political instability to prevent information flow and protest coordination. Iran's January 2025 shutdown reduced connectivity from normal levels to 5-10%, making meaningful internet access impossible for most people.

Why do governments shut down the internet?

Authoritarian governments shut down the internet to prevent documentation of violence, block coordination among protesters, control the information narrative, and suppress dissent. The 1988 massacre in Iran occurred before the internet existed, and no clear record of the violence was preserved. When modern internet-enabled documentation made this impossible, the government learned that shutdowns were necessary to commit violence without evidence. Shutdowns also prevent mobilization because large-scale protests require coordination that occurs online.

What are the best ways to access the internet during a shutdown?

The most reliable circumvention tools are expensive satellite internet (like Starlink, which costs $600 initially and more on black markets), followed by less-common VPN services that might not be blocked yet. Tor is more resistant to blocking than commercial VPNs but can still be detected and blocked by sophisticated DPI systems. Most ordinary people don't have access to any of these tools—circumvention becomes a tool available primarily to people with technical expertise or financial resources. Mesh networks and community networks are theoretically valuable but require significant technical infrastructure and community adoption.

How many people have experienced internet shutdowns?

Between 2019 and 2025, there have been approximately 366 documented internet shutdowns globally, affecting billions of people. Iran, China, India, Myanmar, Sudan, and several other countries have conducted shutdowns lasting days, weeks, or months. The number of shutdowns is accelerating—the frequency more than doubled between the 2012-2019 period and the 2019-2025 period. If trends continue, more than half the world's population could live in countries that have experienced at least one shutdown by 2030.

What happens to the economy during internet shutdowns?

Internet shutdowns cause massive economic disruption. Iran's January 2025 shutdown cost an estimated

Can international pressure stop governments from conducting shutdowns?

International pressure and sanctions have limited effectiveness because shutdowns occur during times when governments have already decided that maintaining power is more important than international reputation. Some sanctions have been imposed on Iran and other countries that conduct shutdowns, but enforcement is inconsistent. The more effective international response is probably to restrict the export of surveillance and DPI technology that enables shutdowns, support the development of circumvention tools and resilient communication infrastructure, and document shutdowns for potential future accountability measures.

What is the difference between a VPN and Tor?

A VPN encrypts your internet traffic and routes it through a server operated by the VPN company, hiding your activity from your ISP and local network. Tor routes your traffic through thousands of volunteer-operated nodes, making it much harder to trace who is accessing what. VPNs are generally faster and more convenient but easier to detect and block. Tor is more resistant to detection and blocking but slower and can be complicated for non-technical users. During the January shutdown, most commercial VPNs were blocked relatively quickly, while Tor proved more resilient, though still blockable with sophisticated DPI systems.

How do governments block circumvention tools like VPNs?

Governments use Deep Packet Inspection (DPI) technology that reads the characteristics of internet traffic packet-by-packet to identify VPN traffic patterns and block them. VPN traffic has distinctive timing, packet size, and entropy patterns that DPI systems can identify even when the actual content of the VPN tunnel is encrypted. As VPN technology improves to evade detection, governments improve their blocking technology. This arms race continues, with governments gradually gaining an advantage as they develop more sophisticated blocking techniques.

What is mesh networking and how could it help during shutdowns?

Mesh networking is a decentralized communication system where devices connect directly to each other without relying on central infrastructure. Instead of connecting to the internet through an ISP, devices in a mesh network relay data between themselves. During shutdowns, mesh networks could theoretically allow local communication to continue. However, mesh networks require technical expertise to set up, dedicated hardware, and community adoption to function at scale. Most people don't have the knowledge or equipment to establish functional mesh networks, and governments can dismantle known mesh networks if they identify them.

The Fight for Digital Freedom Continues

The January 2025 internet shutdown in Iran was brutal and effective. It achieved the government's immediate objectives. But it also revealed something important: the centrality of internet access to modern life, and the importance of defending digital freedom.

What happened in Iran wasn't unique. It was a sophisticated execution of a tactic that's becoming more common globally. But the response—from technologists building circumvention tools, from human rights organizations documenting the shutdown, from diaspora communities maintaining connection to home, from ordinary people finding ways to communicate and resist—shows that the fight isn't over.

Internet access isn't a luxury anymore. It's essential infrastructure. It's how people access healthcare, education, economic opportunity, and information. When governments shut it down, they're not just cutting off social media access. They're disabling fundamental infrastructure.

The challenge moving forward is to make internet infrastructure more resilient, more decentralized, and harder for governments to control. That requires investment in technology, support for civil society organizations, international pressure on governments, and most importantly, commitment from people around the world who care about digital freedom.

The technology exists to make shutdowns harder. Satellite internet, mesh networks, decentralized systems, and more sophisticated circumvention tools are all being developed. But technology alone isn't enough. What's needed is political will—the commitment from governments that value human rights to create consequences for countries that shut down the internet, and from technology companies to build tools with human rights in mind.

What's also needed is recognition that digital rights are human rights. Internet access and digital freedom aren't luxuries or conveniences. They're essential components of modern human dignity. Countries that shut down the internet are violating fundamental rights. The international community should respond accordingly.

The story of internet shutdowns is still being written. The outcome isn't determined. The choices that governments, technology companies, and civil society make in the coming years will shape whether digital authoritarianism becomes more entrenched or whether more resilient, decentralized systems become the norm.

What we can know for certain is that people will continue to fight for their right to communicate, to access information, and to express themselves freely. That fight takes many forms. For some, it's using circumvention tools. For others, it's supporting organizations that defend digital rights. For others still, it's documenting what's happening and maintaining awareness that these issues matter.

The January shutdown in Iran reminded the world of something that's easy to forget when you live in a place with open internet: internet access is fragile. It can be taken away. But so long as people are committed to fighting for it, the possibility of restoration, resilience, and eventual victory remains.

Key Takeaways

- Internet shutdowns are coordinated attacks on multiple infrastructure layers, not just turning off a switch, enabling governments to commit violence without documentation.

- Iran's January 2025 shutdown lasted over 340 days, the longest in the country's history, killing an estimated 3,000-30,000 people while preventing real-time documentation.

- Circumvention tools like VPNs and Tor exist but are increasingly blockable, making them accessible only to people with technical expertise or financial resources.

- Global shutdowns have accelerated dramatically, nearly doubling in frequency between 2012-2019 and 2019-2025, suggesting the tactic is becoming normalized.

- Emerging technologies like satellite internet and mesh networks offer resilience, but decentralized infrastructure that makes shutdowns truly difficult doesn't yet exist at scale.

Related Articles

- Iran's Digital Isolation: Why VPNs May Not Survive This Crackdown [2025]

- Windscribe VPN Iran Russia Crackdown: AmneziaWG Solutions [2025]

- Face Recognition Surveillance: How ICE Deploys Facial ID Technology [2025]

- UK Pornhub Ban: Age Verification Laws & Digital Privacy [2025]

- Pornhub's UK Shutdown: Age Verification Laws, Tech Giants, and Digital Censorship [2025]

- Indonesia Lifts Grok Ban: What It Means for AI Regulation [2025]

![Iran's Internet Shutdowns: How Regimes Control Information [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/iran-s-internet-shutdowns-how-regimes-control-information-20/image-1-1769972898258.jpg)