FTC's Meta Antitrust Appeal: What's at Stake in 2025

Mark Zuckerberg thought he'd won. A federal judge sided with Meta last year, ruling that the government hadn't proven the social media giant operates as a monopoly today, despite its past acquisitions of Instagram and WhatsApp. The FTC's case seemed dead. Zuckerberg could move on to courting the Trump administration, hyping his AI infrastructure plans, and running one of the world's most profitable companies without the constant threat of forced divestitures.

Then the Federal Trade Commission filed an appeal.

That single filing has just restarted one of the most consequential antitrust battles in tech history. The appeal doesn't mean much in headlines, but in practice, it keeps alive the possibility that Meta could be forced to sell Instagram and WhatsApp, the two acquisitions that defined the company's competitive dominance over the past decade. It also signals something deeper about how antitrust enforcement might look under the new Trump administration, despite reports suggesting Trump would go soft on big tech.

This isn't a story about lawyers and courtrooms. It's about whether the internet's economic structure stays frozen as it is now, or whether the government can actually reshape how the world's dominant platforms operate. For Meta's billions of users, advertisers, and competitors who've been locked out of the social media market, the appeal outcome could reshape everything.

Let's break down what's actually happening, why it matters, and what we should expect next.

TL; DR

- The FTC lost but isn't done: A federal judge ruled Meta isn't currently operating as a monopoly, but the FTC appealed rather than accepting defeat.

- The stakes are massive: If the FTC wins the appeal, it could force Meta to divest Instagram and WhatsApp, fundamentally restructuring the social media industry.

- The 2020 charges and 2024 verdict: The FTC filed charges during Trump's first term; Judge Boasberg sided with Meta because YouTube and TikTok proved vigorous competition exists today.

- What the appeal actually argues: The FTC will argue the judge misunderstood antitrust law and how to measure current monopoly status when past anticompetitive conduct shaped today's market.

- Trump administration signals are mixed: Despite Trump's pro-business rhetoric, his new FTC director has vowed to continue the case, complicating the prediction game.

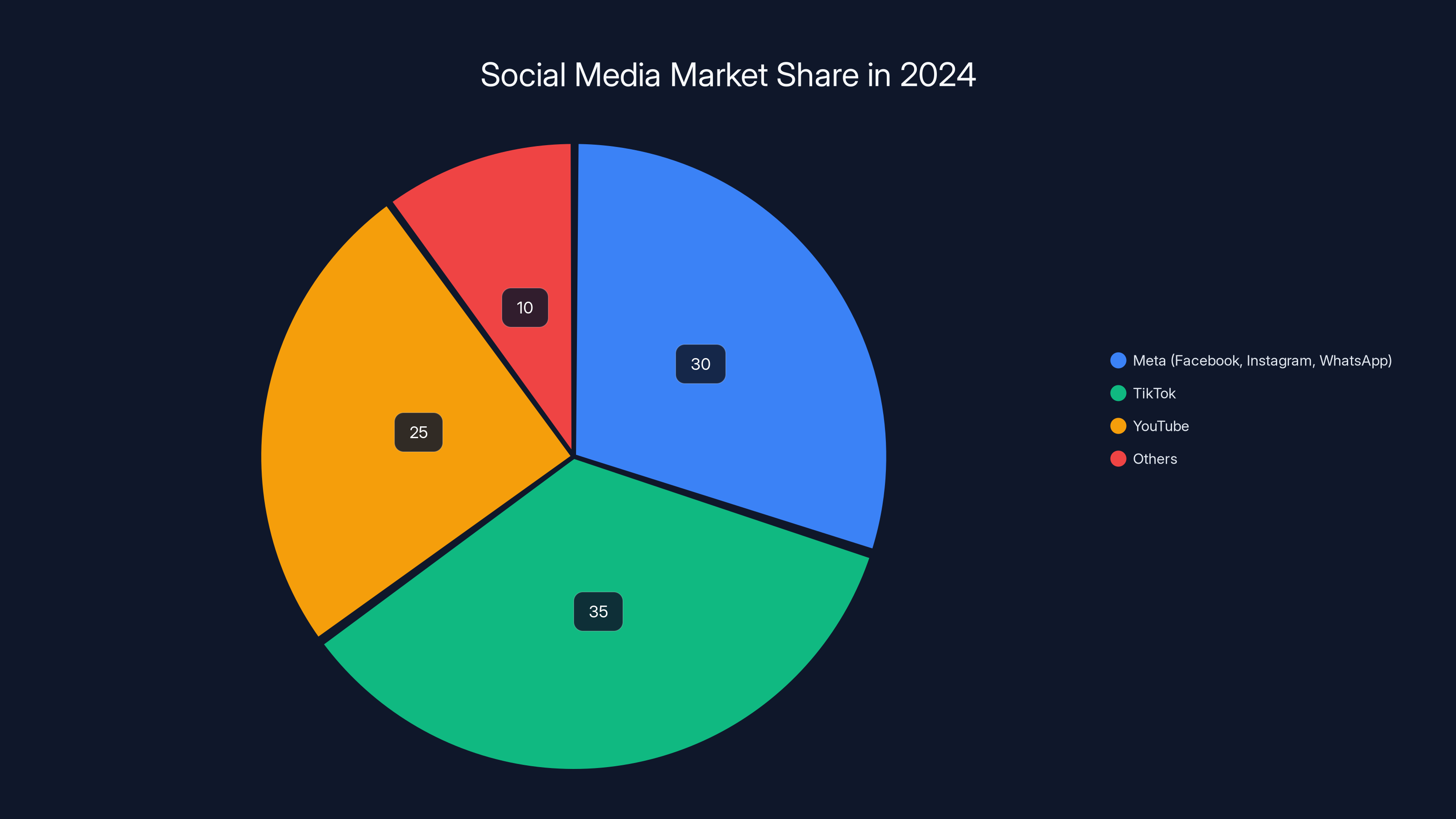

TikTok's explosive growth has significantly impacted the social media landscape, capturing a larger market share compared to Meta and YouTube. Estimated data.

The Original Antitrust Case: What Happened at Trial

The FTC's case against Meta traces back to 2020, filed during President Trump's first term when regulatory scrutiny on big tech was hitting its peak. The government's argument was straightforward in concept but massive in scope: Meta purchased its two most serious competitors (Instagram in 2012 and WhatsApp in 2014) specifically to eliminate competitive threats, not to improve products or create consumer value. By doing so, Meta maintained artificially high barriers to entry in social media, hurt consumers through reduced choice, and ultimately became the dominant social network through predatory acquisition rather than superior service.

The case went to trial in 2023 before US District Judge James Boasberg. Testimony came from current and former Meta executives, including CEO Mark Zuckerberg and ex-COO Sheryl Sandberg. They testified extensively about competitive pressure from TikTok and the rationale behind various product decisions and acquisitions. The discovery process produced millions of internal Meta documents that prosecutors used to paint a picture of a company constantly surveilling competitive threats and crushing them through acquisition.

But here's where things got interesting. Judge Boasberg, writing his decision in 2024, accepted much of the FTC's historical narrative. He essentially agreed that Meta had acted anticompetitively in the past. He agreed that the Instagram and WhatsApp acquisitions were designed to eliminate competitors. He accepted that Meta executives had discussed competitive threats and made acquisition decisions partly to neutralize them.

However, the judge then drew a crucial distinction. He noted that even with Instagram and WhatsApp fully integrated, Meta doesn't currently hold a monopoly in social media because of YouTube's massive scale and, more importantly, TikTok's explosive growth. TikTok has captured younger users and changed how people discover short-form video content. YouTube dominates long-form video. Together, these platforms have created such vigorous competition that Meta can't maintain monopoly-level pricing power or control over social media features and standards.

In antitrust law, what matters most is current market power, not past conduct. Past bad behavior gets punished, but the primary remedy only applies if you're currently holding a monopoly. Judge Boasberg's logic: yes, Meta acted wrongly before, but today it's just one major player in a competitive landscape. Therefore, the remedy the FTC sought (forced divestitures) wasn't warranted.

The verdict felt like a total loss for the FTC. Journalists wrote think pieces about how Trump-era antitrust enforcement had failed. Big tech celebrated. Zuckerberg spent the next year pivoting to becoming a power player in Trump's orbit, pledging massive AI infrastructure investments and generally making himself indispensable to the administration.

But losing at trial doesn't mean the case is finished. You can appeal. And that's exactly what the FTC decided to do.

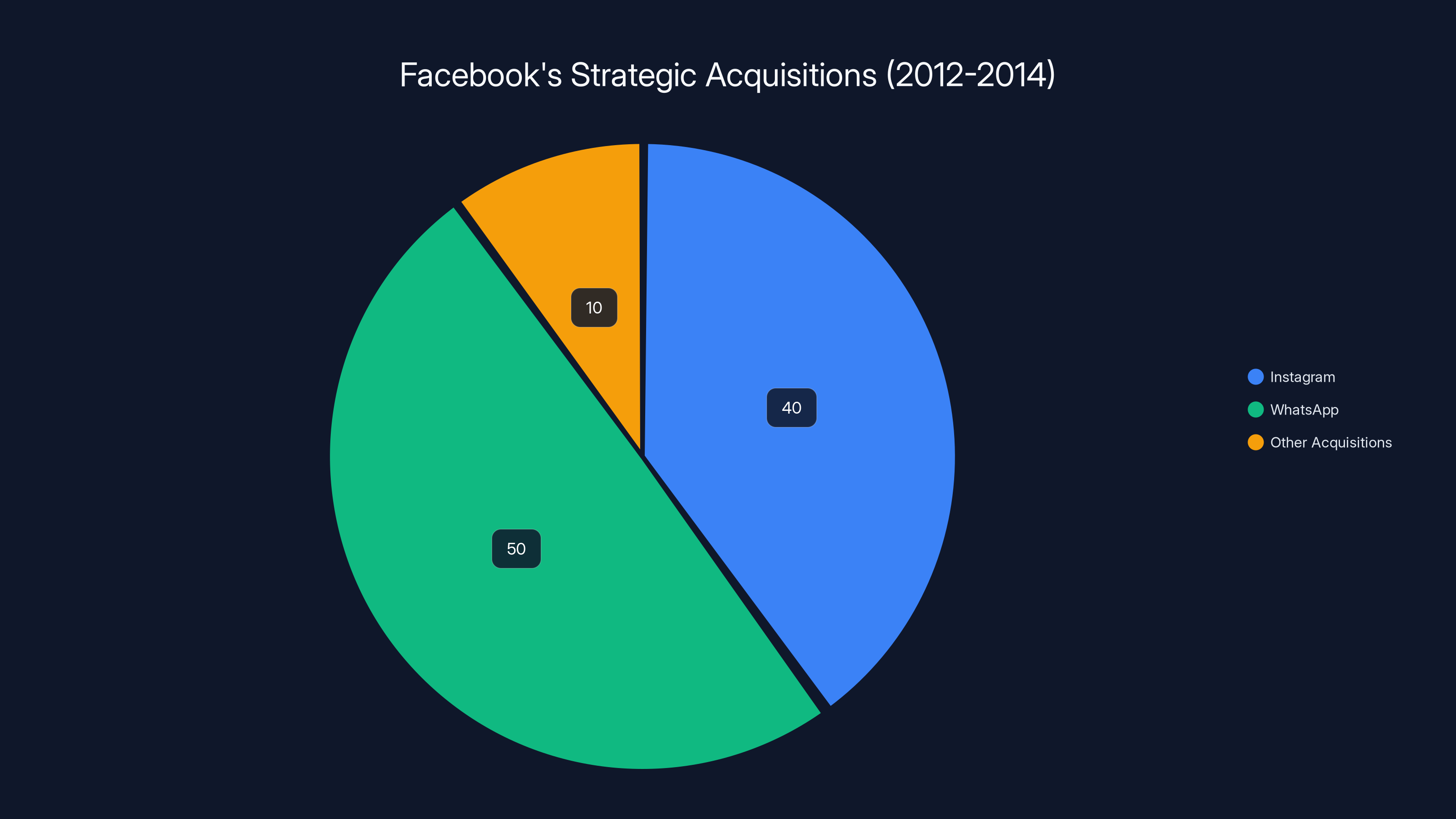

Instagram and WhatsApp acquisitions were pivotal, accounting for 90% of Facebook's strategic market impact during 2012-2014. Estimated data.

Why the FTC Appealed: The Legal Strategy Explained

The FTC's Bureau of Competition Director Daniel Guarnera made the appeal announcement in a statement that pulled no punches. "Meta has maintained its dominant position and record profits for well over a decade not through legitimate competition, but by buying its most significant competitive threats," Guarnera said. The phrasing was deliberate. Guarnera was already laying out the appeal's core argument: Judge Boasberg got the law wrong by focusing too narrowly on current competition rather than the structural dominance Meta built through anticompetitive acquisitions.

Here's the legal theory behind the appeal. Antitrust law has evolved significantly since the 1970s and 1980s when courts adopted the "consumer welfare" standard, which emphasized current prices and consumer choice. Modern antitrust thinking, particularly among progressive regulators and academic economists, argues that this framework misses something crucial: market structure and long-term competitive dynamics.

Under this newer framework, if a company became dominant through illegal conduct (like buying all your competitors), that illegality remains relevant even if current competition appears robust. Why? Because if you'd blocked those acquisitions, the competitive landscape would look entirely different. Today's competition might be artificially weak because of past monopolistic behavior that changed which companies exist and how they operate.

The FTC's appeal will argue that Judge Boasberg applied the old "static" framework when he should have applied a more "dynamic" one that accounts for how past anticompetitive conduct shapes today's market structure. YouTube and TikTok might not even exist in their current forms if Instagram and WhatsApp weren't owned by Meta. Competitive alternatives might be stronger if Meta hadn't bought them out. The judge's framework, the FTC will argue, essentially gives companies a free pass to acquire competitors, since after integration, the merged company just looks like a strong player in what appears to be a competitive market.

It's not a slam-dunk legal argument, but it's substantially more sophisticated than it might appear on the surface. The appeal will likely focus on several specific issues:

The relevance of historical monopolistic conduct: How much weight should courts give to the fact that a company became dominant through illegal acquisitions? The FTC will argue it should be heavy weight. Meta will argue current market structure is what matters.

Market definition and boundary issues: Is social media one market or multiple markets (social networking, messaging, short-form video)? If you split it into narrow markets, Meta looks more dominant. If you lump it into one broad "social" category, Meta looks like just one player. The appeal will rehash this contentious issue.

How to measure consumer harm: The FTC will argue that harm doesn't need to manifest as higher prices. Harm can be reduced product innovation, less privacy protection, or constrained developer opportunities. Meta will argue these soft harms are too speculative and subjective.

The strength of TikTok as a competitive constraint: Judge Boasberg relied heavily on TikTok's growth to argue Meta wasn't a monopoly. But what if TikTok disappears or gets severely restricted? What if it never becomes the entrenched platform Meta is? The appeal will explore whether current competition should be judged as robust when one major competitor operates under existential regulatory threat.

These aren't silly legal arguments designed to waste time. They're fundamental questions about how antitrust law should work in digital platform markets. Different judges could reasonably disagree.

There's also a practical element to the appeal filing. By appealing rather than accepting defeat, the FTC keeps leverage in settlement negotiations. Meta might eventually offer concessions (limiting certain acquisition types, opening APIs, changing algorithm practices) rather than face years of appeals and continued regulatory uncertainty. Settlement might be the actual outcome, even if the legal battle is what drives the negotiations.

The Trump Administration Wild Card: Will FTC Leadership Actually Push This Forward?

Here's where the story gets complicated and somewhat surprising. Everyone expected Trump's return to the White House would mean the end of aggressive tech regulation. Trump generally favors business, and he's close to several tech leaders. Reports circulated that Trump wanted the FTC to back off. Some predicted the appeal would be quietly dropped as a gesture of deference to the new administration's pro-business stance.

Then came the actual staffing decisions. Trump appointed Gail Slater as FTC commissioner, and while Slater is generally business-friendly, the person who actually oversees the antitrust division is Daniel Guarnera, the same Bureau of Competition Director who signed the appeal statement. Guarnera has been remarkably consistent in his messaging. Rather than retreating, he's doubled down, emphasizing that the Trump-Vance FTC will "continue fighting its historic case against Meta."

This is unexpected and reveals something interesting about where Trump administration tech policy actually sits. While Trump talks about being pro-business and has cultivated relationships with tech leaders like Zuckerberg, his actual policy apparatus still contains people like Guarnera who represent a more skeptical, enforcement-oriented approach. It's possible Trump's personal relationships don't fully control FTC action, or it's possible Trump's anti-China stance actually aligns with wanting to keep U.S. tech companies dominant domestically even while reducing their global expansion, or it's possible this is just an inconsistency in Trump's approach.

What's clear is that the appeal is proceeding. Zuckerberg's dinner at the White House and his courting of Trump haven't stopped the government from pressing forward. That's significant. It means the appeal isn't performative or designed to be dropped. The FTC genuinely intends to litigate this.

For Meta, this means the appeal isn't just a theoretical threat. There's genuine legal risk here. The company would be wise to start considering settlement scenarios and damage mitigation strategies rather than assuming Trump's pro-business stance will automatically protect them. Appeals can take years, but they also get real attention. Multiple appeals court judges will scrutinize this case seriously.

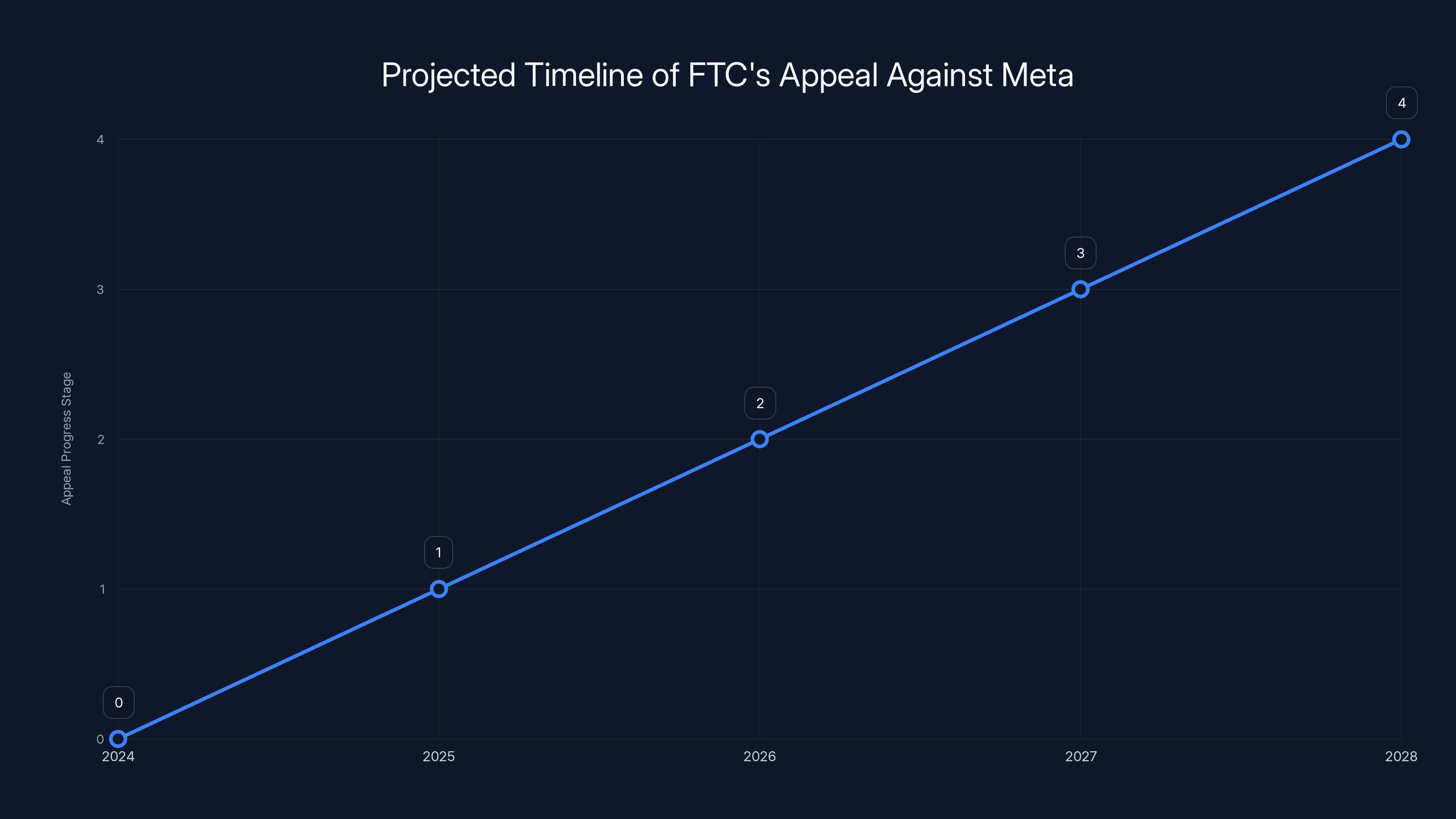

The FTC's appeal against Meta is projected to progress from briefs in 2025 to potential resolution by 2027-2028. Estimated data based on typical antitrust case durations.

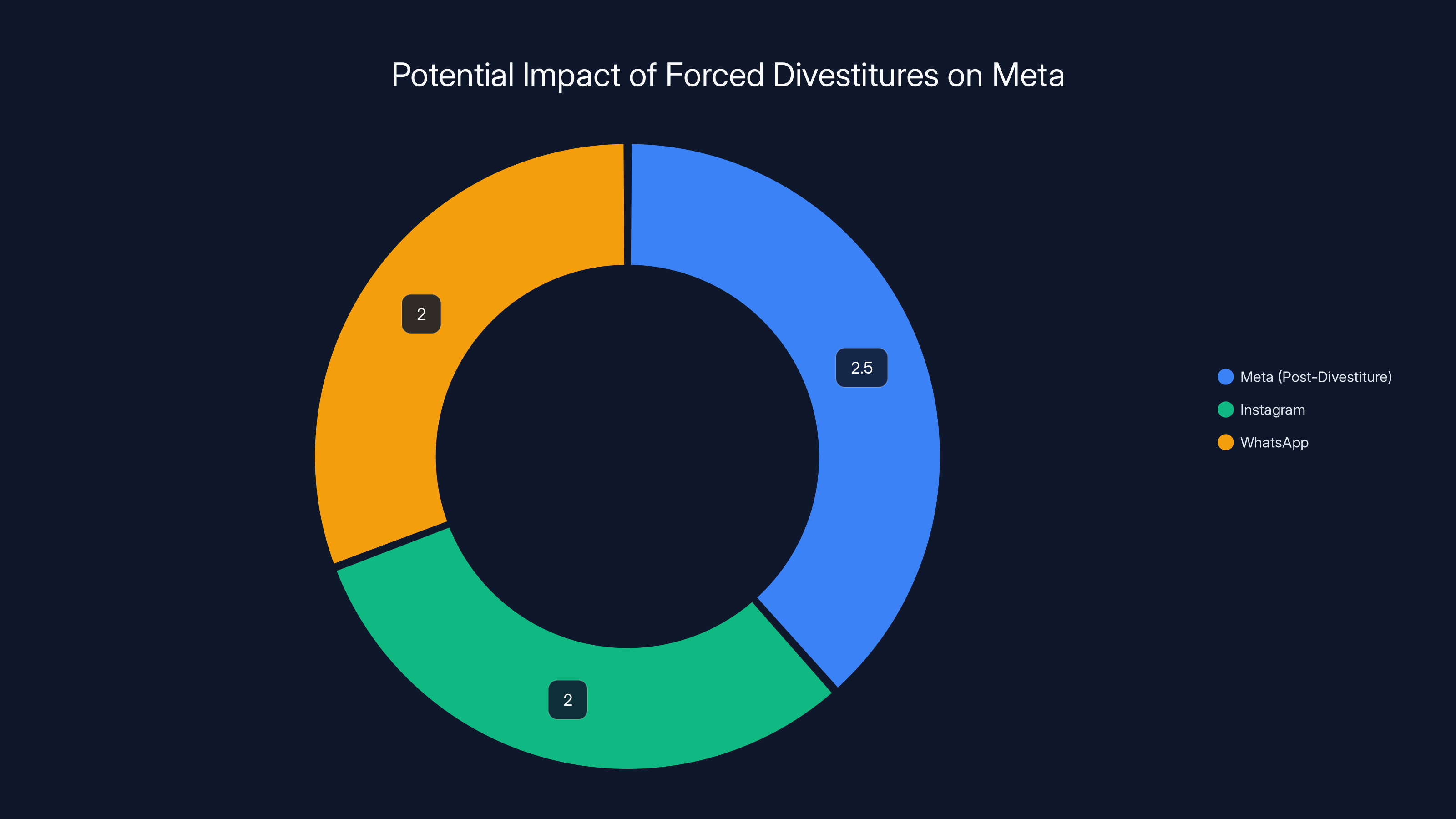

What Forced Divestitures Would Actually Mean for Meta

If the FTC somehow wins this appeal and eventually wins in court (a big if), what happens? The likely remedy would be forcing Meta to divest Instagram and WhatsApp, meaning selling them to independent companies or spinning them out as separate entities.

This would be one of the largest forced corporate breakups since the telecom industry's fragmentation in the 1980s. It would fundamentally reshape social media's competitive landscape.

Let's think through the consequences:

For Meta: The company would lose access to Instagram's 2+ billion users and WhatsApp's 2+ billion users. Financially, that would be devastating. Instagram alone generates over $100 billion in annual advertising revenue. The company would shrink dramatically in user base and revenue. However, Facebook itself (the core social network) would still exist and remain massive. Meta wouldn't disappear; it would just become much smaller.

For Instagram: As an independent company, Instagram would need to build its own infrastructure, payment processing, content moderation systems, and data analytics. The question is whether Instagram could survive independently or whether it's been so integrated into Meta's systems that separation would cripple it. Most analysts think Instagram could function independently, though it would lose access to Meta's massive ad networks and data infrastructure.

For WhatsApp: Similar story, but WhatsApp is even trickier because it's primarily a messaging service with limited monetization. WhatsApp was never designed as an advertising product. As independent company, WhatsApp would need to figure out how to sustain itself financially. It could pursue paid subscriptions, enterprise features, or business tools, but it would lose access to Meta's infrastructure and resources.

For competitive dynamics: Without Meta's acquisition of Instagram, the social media landscape might look totally different. It's unclear whether Instagram would have become the photo-sharing giant it is without Meta's resources, or whether Facebook would have remained the photo-sharing leader, or whether some other platform would have dominated. TikTok's rise happened after Instagram was already Meta-owned, so TikTok's presence today is somewhat independent of these historical acquisitions.

For users and competition: The theory is that breaking up Meta would create more competitive options. New social networks could emerge without Meta's dominance forcing them into acquisition or extinction. Users might have better privacy choices if multiple independent platforms competed on privacy rather than Meta controlling the options. However, this is speculative. Forced divestitures don't automatically create better competition; they just change ownership structures.

Most observers think forced divestitures are unlikely to actually happen, even if the FTC wins the appeal. More likely outcomes include settlement agreements where Meta agrees not to make certain types of acquisitions, opens up data access to competitors, or makes other structural changes that don't require selling off Instagram and WhatsApp. The court system tends to prefer negotiated remedies to radical restructuring.

The Historical Context: Why 2012-2014 Mattered So Much

To understand why the FTC is appealing and why this case matters, you need to understand what Instagram and WhatsApp meant in 2012-2014.

When Facebook acquired Instagram for $1 billion in 2012, Instagram had about 100 million users. It was a photo-sharing app with a clean aesthetic and young demographic. It was probably the most direct threat to Facebook's dominance at that time. Younger people were using Instagram more than Facebook itself. If Instagram had continued growing independently, it might have become the primary social network for the younger generation, potentially allowing other users to migrate as well.

Facebook's executives absolutely understood this threat. There's extensive internal email evidence that Mark Zuckerberg and other leaders viewed Instagram as a competitor they needed to neutralize. Buying it eliminated that risk while also giving Facebook ownership of an emerging trend it didn't invent.

Then in 2014, Facebook acquired WhatsApp for $19 billion. This was even more strategically important. WhatsApp was a messaging app that had global reach, especially in markets where SMS wasn't ubiquitous (like India and Latin America). It was profitable, fast-growing, and appealed to international users. More importantly, WhatsApp represented a different model of communication: direct person-to-person messaging rather than broadcast social networking.

Again, internal documents showed that Facebook executives were concerned about WhatsApp as a potential threat to their communication dominance. By acquiring it, Facebook controlled both the social networking platform (Facebook and Instagram) and the independent messaging platform (WhatsApp). You couldn't use WhatsApp without funding Facebook's acquisition.

The FTC's argument is that these weren't strategic acquisitions designed to improve products or expand into new markets. They were acquisitions designed to neutralize the only serious threats Facebook faced. If you block these acquisitions, you get a world where Instagram competes with Facebook for social networking, and WhatsApp competes independently in messaging. That creates more competitive options for users.

Meta's counter-argument is that acquisitions of this type are normal business. If Instagram had remained independent, it might have remained a photo app rather than evolving into a full social platform. Competitive conditions change constantly. Meta's strategy was to buy emerging competitors and integrate them, which is what successful companies do.

Both arguments have merit, and that's why this case has been genuinely contested throughout litigation. Neither side's theory is obviously correct or incorrect.

The historical context is important for the appeal because it helps explain why the FTC thinks it has a legitimate case. These weren't passive acquisitions of complementary services. They were strategic purchases of competitive threats made by executives who explicitly recognized the threat. That evidence is powerful in antitrust litigation, even if it's not ultimately dispositive.

If forced to divest Instagram and WhatsApp, Meta would retain a smaller user base and significantly reduced revenue, while Instagram could potentially generate substantial revenue independently. Estimated data.

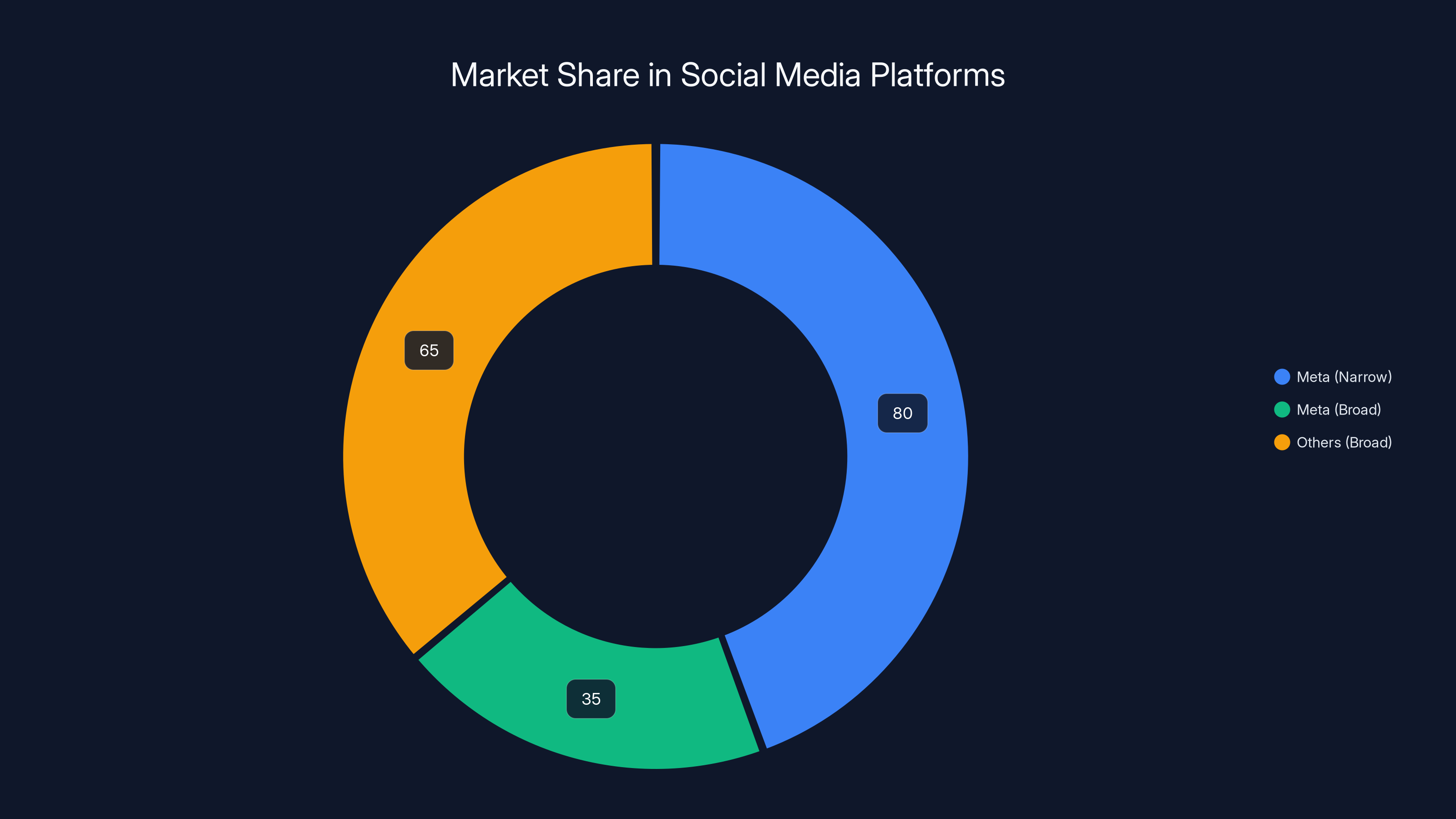

The Market Definition Problem: Is It One Market or Many?

Here's where antitrust law gets genuinely complicated and becomes almost philosophical. The FTC and Meta disagree about whether "social media" is one market or multiple markets. This disagreement is fundamental to whether Meta is a monopoly.

Narrow market definition (FTC's approach): Social networking (Facebook plus Instagram) is one market distinct from messaging (WhatsApp) and short-form video (TikTok). Within social networking specifically, Meta has about 80% market share in the U.S. That's a clear monopoly by any measure.

Broad market definition (Meta's approach): All social communication platforms (social networking, messaging, video sharing, etc.) constitute one market. Within that broad market, Meta has maybe 30-40% if you count YouTube, TikTok, Snapchat, and various international platforms. That's not a monopoly; that's a major player in a competitive market.

These aren't arbitrary definitions. Courts have to decide where the boundaries are, and different boundaries produce different conclusions about market power. In the trial before Judge Boasberg, both sides presented evidence about market boundaries. The judge essentially sided with Meta's broader definition, which is why he concluded Meta wasn't a monopoly despite Meta's dominance in specific narrower categories.

The appeal will likely revisit this issue in detail. Appeals courts sometimes grant regulatory agencies deference in defining markets based on functional similarities. The FTC will argue that social networking is functionally distinct from video consumption or messaging, so market definitions should split them up. Meta will defend the broader definition.

What's interesting is that neither definition is definitively "right" or "wrong." Markets in antitrust law are defined based on functional similarity and the degree to which customers can substitute one service for another. If you want to share photos and see what your friends are doing, can you substitute YouTube? Not really. Can you substitute TikTok? Sort of, but it's different. Can you use WhatsApp? No, that's messaging. The substitutability analysis gets complex fast.

This market definition issue is also relevant to settlement negotiations. Meta might accept certain restrictions in the social networking market (like not acquiring other social networks) while resisting broader restrictions across all social communication. The market definition debate shapes what concessions might be acceptable.

How TikTok Became the Case's Wildcard

Judge Boasberg's decision relied heavily on TikTok as evidence that Meta doesn't hold a monopoly. TikTok's growth showed that new competitors could succeed even with Meta's scale. TikTok's ability to attract users away from Instagram (particularly younger users) proved vigorous competition was alive in social media.

But here's the complication: TikTok's regulatory status is uncertain. Congress passed legislation requiring TikTok to divest its U.S. operations or face a ban. The law's status has been contested through multiple court challenges. If TikTok disappeared from the U.S. market, Judge Boasberg's reasoning about robust competition would weaken significantly.

The FTC will likely argue in its appeal that TikTok can't be relied on as evidence of current competitive constraints because TikTok's existence is contingent on government policy decisions, not on enduring competitive dynamics. Meta will argue that TikTok's current presence is what matters for evaluating current monopoly status.

This is genuinely tricky legally. Antitrust cases try to evaluate current market structure to predict future competitive dynamics. But if a major competitor's existence is temporary or contingent on regulatory decisions outside the company's control, how should that factor into the analysis? Should courts assume TikTok will persist? Should they assume it will disappear? Should they assume it will be restructured in ways that reduce its competitive threat?

There's no clear answer, and that's why TikTok's status becomes a crucial variable in the appeal. If TikTok gets banned or severely restricted while the appeal is pending, the FTC's case gets stronger because Meta would be back to near-complete dominance in social media. If TikTok thrives and expands, Meta's competitive constraint argument gets stronger.

Zuckerberg presumably understood this dynamic when he positioned Meta as pro-Trump and pro-AI infrastructure investment. By making Meta essential to Trump's tech policy ambitions, Zuckerberg might have been hedging against both the antitrust case and potential TikTok regulation. If TikTok gets banned, Meta is the beneficiary of reduced competition. If the antitrust case proceeds, Meta's value to the administration might buy some leniency or settlement.

Meta's market share varies significantly depending on market definition: 80% in a narrow market vs. 35% in a broader market. Estimated data.

The Precedent Problem: What Does This Mean for Other Tech Companies?

The Meta appeal matters far beyond Meta itself because it establishes precedent for how antitrust law applies to technology acquisitions generally. If the FTC wins, it signals that tech companies can't simply acquire competitive threats to maintain dominance. If Meta wins (or if the appeal is settled quietly), it signals that past acquisitions are largely off-limits for antitrust enforcement.

Google has faced similar scrutiny for various acquisitions (YouTube, DoubleClick, etc.). Apple's acquisition of various companies that integrated into the App Store ecosystem raises similar questions. Amazon's acquisition of Whole Foods and various logistics companies follow the same pattern of buying competitors or complementary services.

A successful FTC appeal against Meta would create pressure for similar cases against other tech giants. You'd see renewed investigation into Google's acquisitions, Microsoft's gaming acquisitions, and various Amazon purchases. Regulators in Europe and other jurisdictions would cite it as precedent for their own enforcement actions.

Conversely, if Meta wins the appeal, it sends a message to tech companies that large acquisitions made years in the past are extremely difficult to unwind, even if they were strategically important. That actually favors large incumbents over startups, because it means the path to growth involves acquisition rather than organic growth or outside investment.

The precedent issue is likely relevant to how the appeals court approaches the case. Judges think about precedent implications. They know their decision will shape how enforcement agencies and other courts approach similar cases. That's a factor in how they reason through difficult antitrust questions.

Settlement Possibilities: The Likely Endgame

Although the FTC is appealing and expressing determination to litigate, settlement is probably the most likely outcome. Here's why:

Antitrust appeals take years. They're expensive for both sides. The legal theories are complex and genuinely contested, meaning neither side can be certain of victory. By the time the appeals process concludes, market conditions may have shifted substantially. And forced divestitures are incredibly complicated to execute—you'd need to separate systems that have been integrated for over a decade.

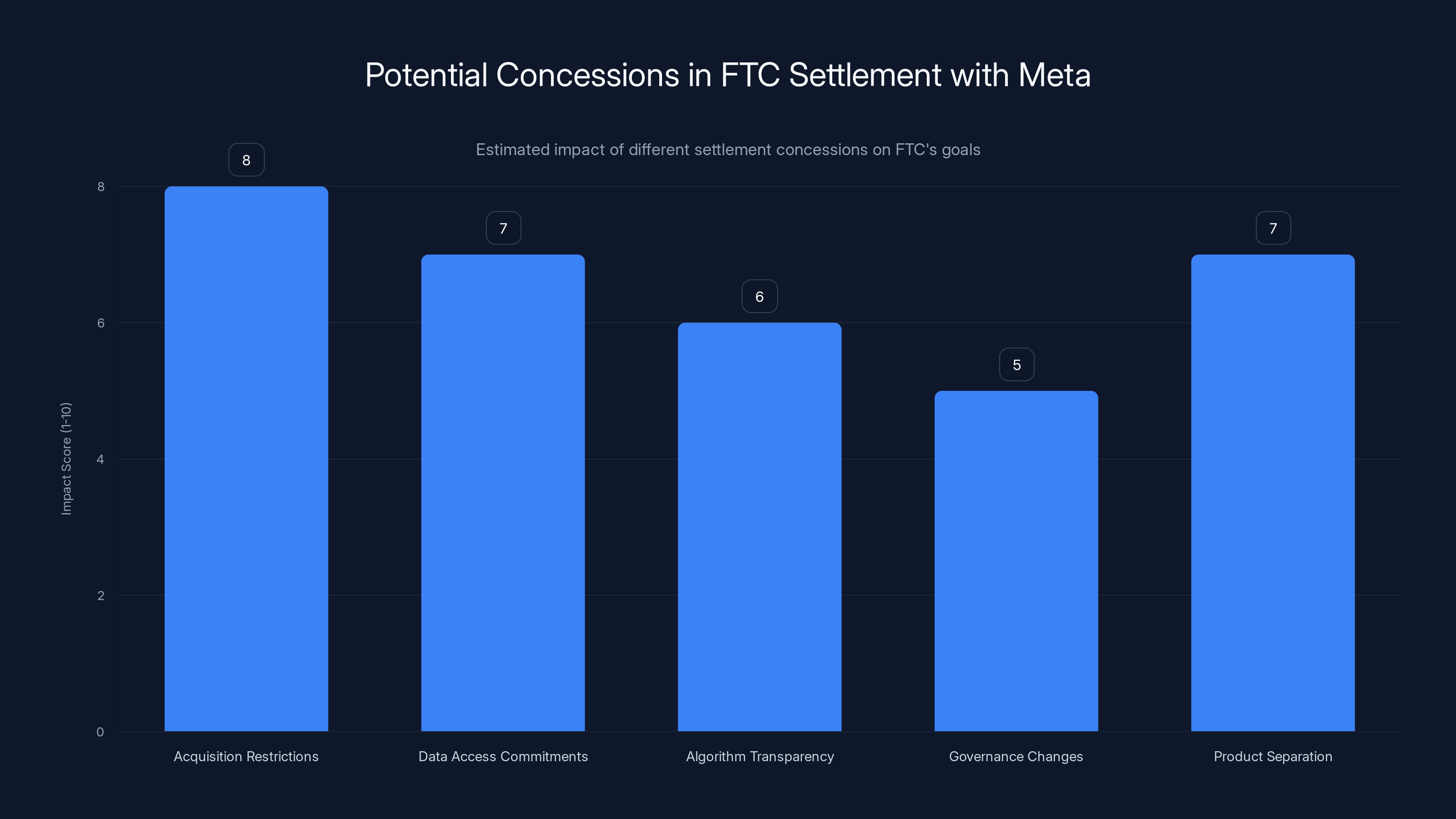

Meanwhile, Meta can offer concessions that address many of the FTC's concerns without requiring full divestitures. For example:

Acquisition restrictions: Meta could agree not to acquire social media platforms or messaging services above certain user thresholds. This prevents future Instagram-style acquisitions without requiring selling existing properties.

Data access commitments: Meta could agree to open up certain data to competitors, allowing competing platforms to interoperate or at least access user information to improve their services.

Algorithm transparency: Meta could commit to more transparency about how its algorithms work, allowing researchers and regulators to monitor for anticompetitive behavior.

Governance changes: Meta could agree to structural changes that reduce the person of Mark Zuckerberg's unilateral control, establishing independent oversight for competition-sensitive decisions.

Product separation: Meta could commit to not integrating WhatsApp or Instagram user data into the main Facebook platform for advertising targeting, even while keeping ownership.

Any of these would constitute a significant victory for the FTC because they would actually constrain Meta's future behavior rather than just punishing past behavior. They're also more achievable than forced divestitures.

For Meta, settlement is also preferable to years of appeals litigation. The company would rather resolve the uncertainty, avoid the distraction, and move forward. Zuckerberg probably prefers settlement that's painful but finite to perpetual regulatory warfare.

The question is what terms would be acceptable to both sides and what would be necessary to get there. That's purely speculative at this point, but history suggests that major antitrust cases usually end in negotiated settlements rather than all-the-way litigation.

Estimated impact scores suggest that acquisition restrictions and product separation could have the highest impact in addressing FTC's concerns, while governance changes might have a moderate effect. Estimated data.

What the Appeal Timeline Actually Looks Like

People often ask how long appeals take. The answer is: a long time.

The appeal will first go to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit, which hears most major antitrust cases. The D.C. Circuit will need to review the trial record (which is enormous in this case), accept briefs from both sides, and potentially hold oral arguments. That process typically takes 12-18 months minimum.

After the D.C. Circuit issues a decision, the losing party can request a rehearing before the full court (not just a panel of three judges). If that's denied, they can petition for certiorari to the U.S. Supreme Court, though the Supreme Court rarely takes antitrust cases and almost never takes cases that don't involve Supreme Court precedent conflicts.

So a realistic timeline is:

- Briefs and preliminary motions: 2025-2026 (6-12 months)

- Oral arguments and decision: 2026-2027 (6-12 months after briefs are done)

- If petitioned for full court rehearing: 2027 (3-6 months)

- If appealed to Supreme Court: 2027-2028 (but unlikely to be granted)

That means we're probably looking at 2027 or 2028 for a final appellate decision, assuming no settlement. That's years away. By that point, the tech landscape could look completely different. AI might be far more dominant. TikTok might be banned or sold. Meta might have pivoted to entirely different business models. The competitive dynamics Judge Boasberg relied on might be totally changed.

That's another reason settlement is likely. Litigating this for potentially 3+ more years is not an appealing prospect for either side.

International Regulatory Implications: The Global Pattern

Meta's regulatory problems aren't limited to the United States. European regulators have been even more aggressive in pursuing antitrust and anti-competitive concerns. The European Commission has fined Meta billions and imposed various restrictions on data processing and acquisition strategies.

If the FTC's appeal succeeds in the U.S., it would likely embolden European regulators to pursue similar cases or escalate their enforcement. Conversely, if Meta wins the appeal, it suggests that current market analysis (rather than historical conduct) is the relevant framework, which would affect how European cases proceed.

The global pattern matters for Meta's strategy. The company is probably already considering how U.S. antitrust decisions affect its exposure in Europe, the UK, and other jurisdictions. A loss in the U.S. appeal would ripple internationally. A win would provide some shield, though European law is distinct enough that U.S. outcomes don't automatically control European cases.

There's also a geopolitical element. The U.S. regulators might be particularly motivated to maintain strong tech leadership, which could mean favoring settlement or relatively light remedies rather than breakups. European regulators might be more willing to impose radical restructuring since they don't have the same stakes in maintaining U.S. tech dominance globally.

The Broader Question: What Is Antitrust Enforcement Actually For?

Beneath all the legal mechanics and precedent questions lies a fundamental question about what antitrust law is supposed to accomplish. Is it supposed to make prices cheaper for consumers? Is it supposed to prevent excessive market concentration? Is it supposed to protect the competitive process itself regardless of immediate consumer impact? Is it supposed to prevent any company from accumulating too much power?

Different people answer these questions differently, and those differences drive how they evaluate the Meta case.

The Chicago School perspective (dominant in courts for decades): Antitrust law exists primarily to protect consumer welfare, measured by prices, selection, and quality. If consumers benefit from Meta's services even if Meta has market power, then antitrust enforcement shouldn't interfere. This framework tends to favor Meta because its services are free to users.

The structural concern perspective (gaining influence recently): Antitrust law also exists to prevent excessive concentration of power that can be misused even if not immediately impacting prices. By this standard, Meta's dominance is itself the problem, regardless of whether prices are low. This framework tends to favor the FTC's enforcement approach.

The innovation perspective (appealing to many tech-focused commentators): Antitrust law should avoid chilling innovation and risk-taking. Aggressive enforcement against acquisitions might make investors less willing to fund startups, knowing those startups could be valuable acquisition targets for larger companies. This perspective tends to skeptical of forcing divestitures.

Judge Boasberg seemed to lean more toward the consumer welfare perspective, which is why he focused on whether Meta could raise prices or reduce service quality given competition from TikTok. The FTC seems to lean toward structural and historical concerns, which is why it emphasizes that Meta's dominance was built through acquisition of competitors.

The appeal will partly be about which philosophical framework appellate judges accept. That's not really answerable in advance because it depends on the specific judges assigned and how they interpret antitrust doctrine.

What Meta Is Doing to Prepare for Appeal

Meta isn't just passively waiting for appeals court to rule. The company is actively preparing its defense while simultaneously positioning itself for potential settlement.

On the legal side, Meta is likely investing enormous resources in appellate briefs that will try to convince the appeals court that Judge Boasberg got the relevant legal frameworks right. Meta's lawyers are probably drafting briefs arguing that current market structure is the appropriate standard, that TikTok represents genuine competition, and that forced divestitures would be inappropriate remedies even if the FTC won every factual dispute.

On the business side, Meta has incentive to demonstrate to regulators that the company is taking competitive concerns seriously. That's partly why Meta has been making moves like improving privacy controls, providing better creator tools to compete with TikTok, and generally signaling responsiveness to regulatory concerns. These moves could be cited in settlement negotiations as evidence that Meta is willing to address FTC concerns without litigation.

On the political side, as mentioned, Zuckerberg has been heavily courting Trump, pledging infrastructure investment, and generally trying to make Meta valuable to the administration. This is partly hedging against the antitrust case by making the administration more reluctant to pursue aggressive enforcement.

Meta is also presumably building relationships with appeals court judges' law clerks (through published materials and social networks of legal professionals), not through improper lobbying, but through the normal process of making sure their legal arguments are well-understood and professionally presented.

The company is likely also exploring settlement parameters, talking to intermediaries who might facilitate discussion with FTC leadership, and generally laying groundwork for negotiated resolution even while fighting the appeal.

What the FTC Needs to Win on Appeal

For the FTC to win, the appeals court needs to conclude that one of the following is true:

- Judge Boasberg misunderstood the relevant antitrust law

- Judge Boasberg misapplied that law to the facts

- The record contains evidence that contradicts the judge's findings (but appeals courts defer heavily to trial judges on factual findings, so this is a high bar)

- The legal standard should be different from what Judge Boasberg applied

Most likely, the FTC's appeal will focus on option 1 and 4: arguing that the judge used the wrong legal framework. The FTC will argue that by focusing solely on current competitive constraints (TikTok), Judge Boasberg ignored relevant considerations about how Meta's dominance was built and how current competition would look different absent those historical acquisitions.

The FTC needs at least some of the three-judge appellate panel to be sympathetic to this argument. Appeals court panels don't always agree on legal questions, so the FTC doesn't need unanimity. A 2-1 split in the FTC's favor would be victory.

The appeals court will probably scrutinize the TikTok question in detail. Is TikTok sufficiently entrenched and permanent that it proves Meta isn't a monopoly? Or is TikTok sufficiently contingent on government regulation that it shouldn't count as a reliable competitive constraint? The answer to that question could determine the appeal's outcome.

What This Means for Users, Advertisers, and the Industry

For Facebook and Instagram users: If the FTC wins the appeal and ultimately forced divestitures happen, the most likely impact is that Instagram becomes an independent company with separate data practices, potentially better privacy controls, and a different business model than Meta's. You might still use Instagram the same way, but the company operating it would be different. You'd likely still see ads, but the ads might be less targeted. Services would probably become more expensive (Instagram might introduce subscription features or paid features that are now free).

For WhatsApp users: Similar story. As independent company, WhatsApp would need to monetize somehow. It might introduce paid plans, business features, or ads. The integration with Facebook would disappear, which could mean either better privacy (less data sharing) or worse service (less investment in infrastructure).

For advertisers: A forced breakup would fragment Meta's massive advertising network. Currently, advertisers can target people across Facebook, Instagram, Messenger, and WhatsApp with integrated campaigns and shared data. Breaking up Meta would reduce that capability. Advertisers would lose some targeting precision but might have more platforms to choose from for campaign strategies.

For competitors and startups: A Meta breakup or FTC settlement that restricts future acquisitions could create more breathing room for social media competitors. It would be harder for Meta to acquire emerging competitors, which is the main way Meta eliminated threats (Instagram, WhatsApp, Snapchat-like services). New social platforms might have better chances at sustained growth without facing acquisition pressure from Meta.

For regulators globally: A successful FTC appeal would establish precedent for aggressive antitrust enforcement against tech acquisitions. It would probably trigger waves of similar investigations and enforcement actions against other tech companies. It would signal that past acquisitions can be unwound even years later if deemed anticompetitive.

FAQ

What exactly is the FTC appealing?

The FTC is appealing Judge Boasberg's 2024 decision that Meta is not currently operating as a monopoly, despite the judge accepting much of the FTC's evidence that Meta acted anticompetitively in the past. The FTC argues the judge applied the wrong legal standard and didn't properly account for how Meta's dominance was constructed through anticompetitive acquisitions of Instagram and WhatsApp. The appeal seeks to revive the possibility of forcing Meta to divest these acquired properties.

How long will the appeal take?

Antitrust appeals typically take 2-3 years from filing briefs through appeals court decision. Given the complexity of the Meta case, a reasonable timeline would be 2025 for briefs, 2026 for oral arguments and decision, with potential further appeals pushing toward 2027-2028. Settlement at any point could accelerate resolution significantly.

What's the most likely outcome?

Settlement is probably more likely than full litigation victory for either side. Meta might agree to acquisition restrictions, data access commitments, and algorithm transparency in exchange for the FTC dropping the case or narrowing the appeal scope. Complete forced divestitures of Instagram and WhatsApp are less likely even if the FTC wins, because judges tend to prefer less radical remedies and Meta would argue separation creates technical and operational chaos.

Does TikTok matter to the appeal?

Yes, significantly. Judge Boasberg relied on TikTok's growth and success as evidence that Meta doesn't hold a monopoly because vigorous competition exists. The FTC will argue in the appeal that TikTok's regulatory status is too uncertain to count as a reliable competitive constraint. If TikTok gets banned or heavily restricted while the appeal is pending, the FTC's position strengthens because Meta would be back to near-complete social media dominance.

Could the Supreme Court get involved?

Possibly, but unlikely. The Supreme Court rarely takes antitrust cases and usually only does so when lower courts disagree on important legal questions or when Supreme Court precedent is directly implicated. The Meta case might generate a Supreme Court petition, but the high court would probably deny it and let the appeals court decision stand. Supreme Court involvement would push resolution to 2028 or 2029 at the earliest.

What does this mean for other tech companies?

A successful FTC appeal against Meta would likely trigger similar antitrust investigations and enforcement actions against Google, Microsoft, Amazon, and Apple for various acquisitions. It would establish precedent that tech companies can't simply acquire competitive threats and expect those acquisitions to be off-limits for enforcement decades later. Conversely, if Meta wins the appeal, it signals that past acquisitions are essentially protected, which favors large incumbents over startups and new competitors.

Would Instagram and WhatsApp be sold to competitors or broken into smaller pieces?

If forced divestitures happened, the most likely scenario is that Instagram and WhatsApp would be sold as intact entities to investment firms, private equity groups, or potentially other tech companies, rather than being fragmented into smaller pieces. The judge would probably require that any buyer be sufficiently independent from Meta to ensure genuine competition. Finding appropriate buyers would be one of the biggest practical challenges in executing forced divestitures.

Is there any chance Trump administration will drop the appeal?

Unlikely. While Trump is generally pro-business, his FTC leadership (particularly Daniel Guarnera) has explicitly committed to continuing the case. Trump's relationship with Zuckerberg is good, but that hasn't overridden the FTC's enforcement decision. It's possible political pressure could eventually force settlement, but dropping the appeal entirely would be a dramatic reversal that would face significant backlash from career prosecutors who view the case as legitimate.

Conclusion: Why This Appeal Matters More Than You Think

On the surface, the FTC's appeal of the Meta antitrust case is a legal dispute between regulators and a tech company. Dig deeper, and it's about fundamental questions regarding how the internet's power structure should be organized. Should Meta maintain its acquisitions and keep operating as an integrated mega-platform? Or should Instagram and WhatsApp be independent companies competing separately?

The appeal's outcome will shape not just Meta's future but the future of tech regulation globally. It will influence how regulators approach other tech company acquisitions. It will affect how investors think about tech M&A strategy. It will determine whether large incumbents can acquire emerging competitors with impunity or whether aggressive enforcement creates actual risk.

For Zuckerberg, the appeal is frustrating because he thought he'd won at trial. For the FTC, it's a rare chance to fight back against a setback and make the argument that historical conduct and market structure matter more than the judge recognized. For the rest of us, it's a crucial test of whether antitrust enforcement actually constrains tech power or whether acquisition strategy is effectively protected in our legal system.

The appeal probably won't conclude until 2026 or 2027. By that time, we'll have more clarity on TikTok's regulatory fate, AI's role in social media, and whether Trump's pro-business approach to tech regulation holds. Those developments will inevitably shape how the appeals court approaches this case.

Until then, the case is simply dormant, waiting for briefs, oral arguments, and judicial reasoning. But the stakes remain massive: nothing less than how the world's largest social media company will be structured and constrained.

Key Takeaways

- The FTC appealed rather than accepting the 2024 trial loss, keeping alive the possibility of forced divestitures of Instagram and WhatsApp.

- Judge Boasberg sided with Meta because TikTok and YouTube provide vigorous competition, but the FTC argues this framework ignores how past acquisitions shaped today's market.

- Settlement is probably more likely than full litigation, with Meta potentially accepting acquisition restrictions or data transparency commitments.

- The appeal's outcome will establish precedent for antitrust enforcement against other tech companies' historical acquisitions.

- Appeals process typically takes 2-3 years, meaning resolution unlikely before 2026-2027 at earliest, with potential Supreme Court involvement extending further.

Related Articles

- Trump Mobile FTC Investigation: False Advertising Claims & Political Pressure [2025]

- ICE Verification on Bluesky Sparks Mass Blocking Crisis [2025]

- California AG vs xAI: Grok's Deepfake Crisis & Legal Fallout [2025]

- xAI's Grok Deepfake Crisis: What You Need to Know [2025]

- Grok's Unsafe Image Generation Problem Persists Despite Restrictions [2025]

- Meta Compute: The AI Infrastructure Strategy Reshaping Gigawatt-Scale Operations [2025]