Introduction: The Blackout That Shook West Africa

On a Wednesday afternoon in September 2024, something extraordinary happened in Gabon. Internet users across the country opened their phones to find Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, and X completely inaccessible. No warning. No timeline. Just gone.

The government called it a temporary measure for "national security" during a period of civil unrest. For the 2.4 million people living in this Central African nation, it meant an instant severing of their primary communication channels. Families couldn't reach relatives. Businesses couldn't connect with customers. News organizations couldn't post updates.

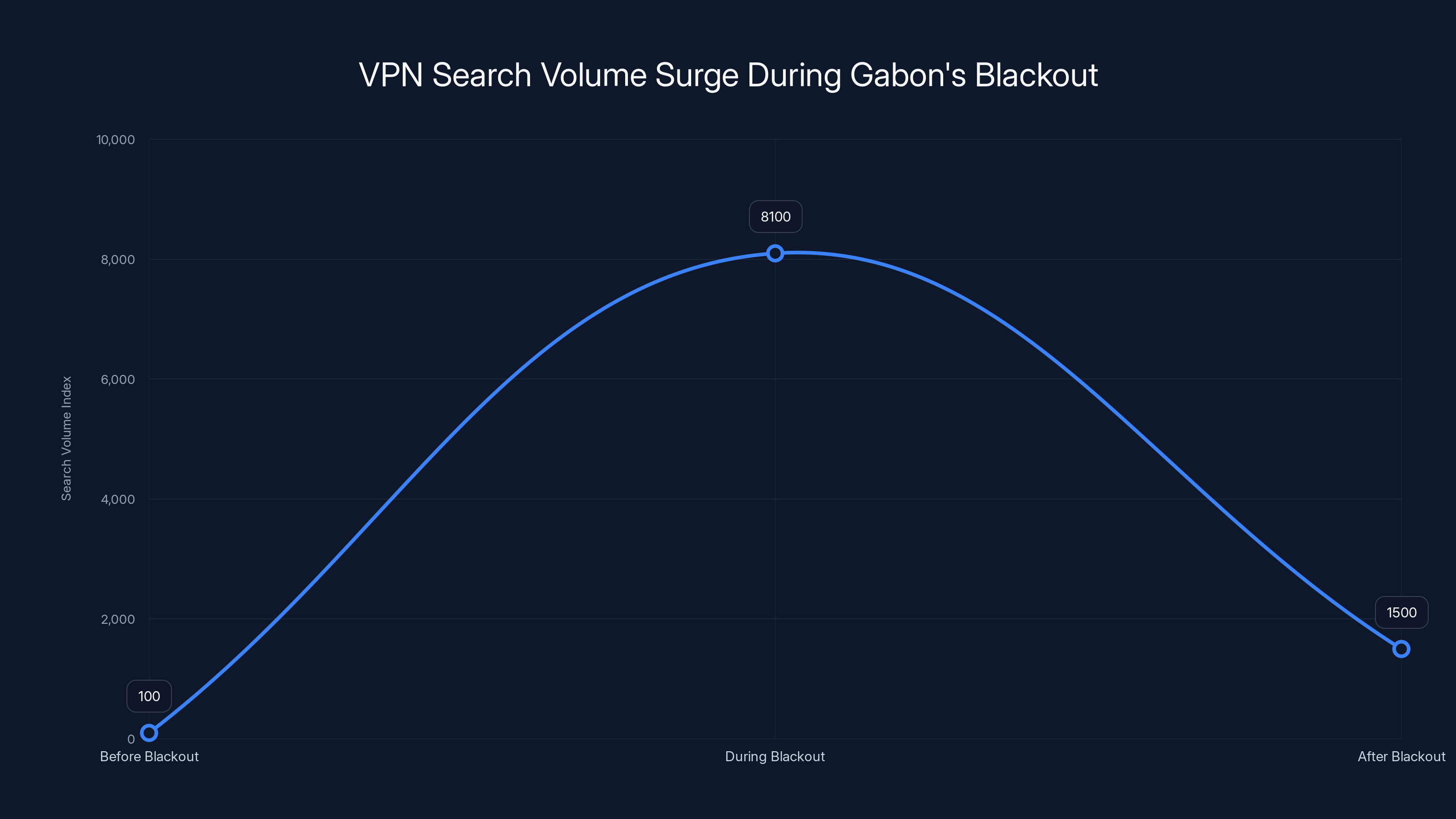

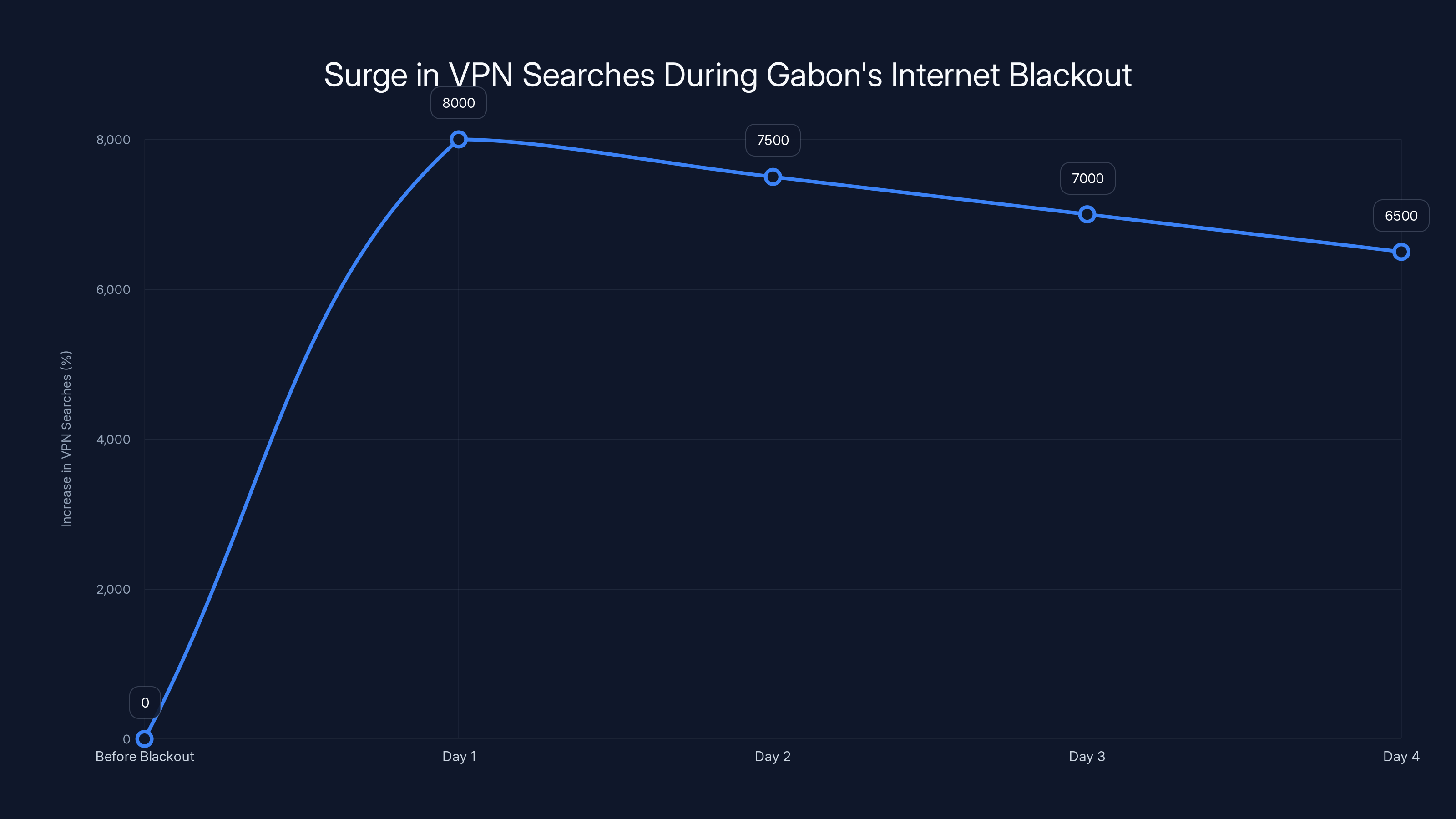

But here's what made this blackout particularly noteworthy: within hours, VPN searches skyrocketed by 8,000%. Not 800%. Not 80%. Eight thousand percent. People were desperately hunting for ways to circumvent the blocks, and they found them. The internet, it turns out, is remarkably difficult to fully suppress once people understand what's at stake.

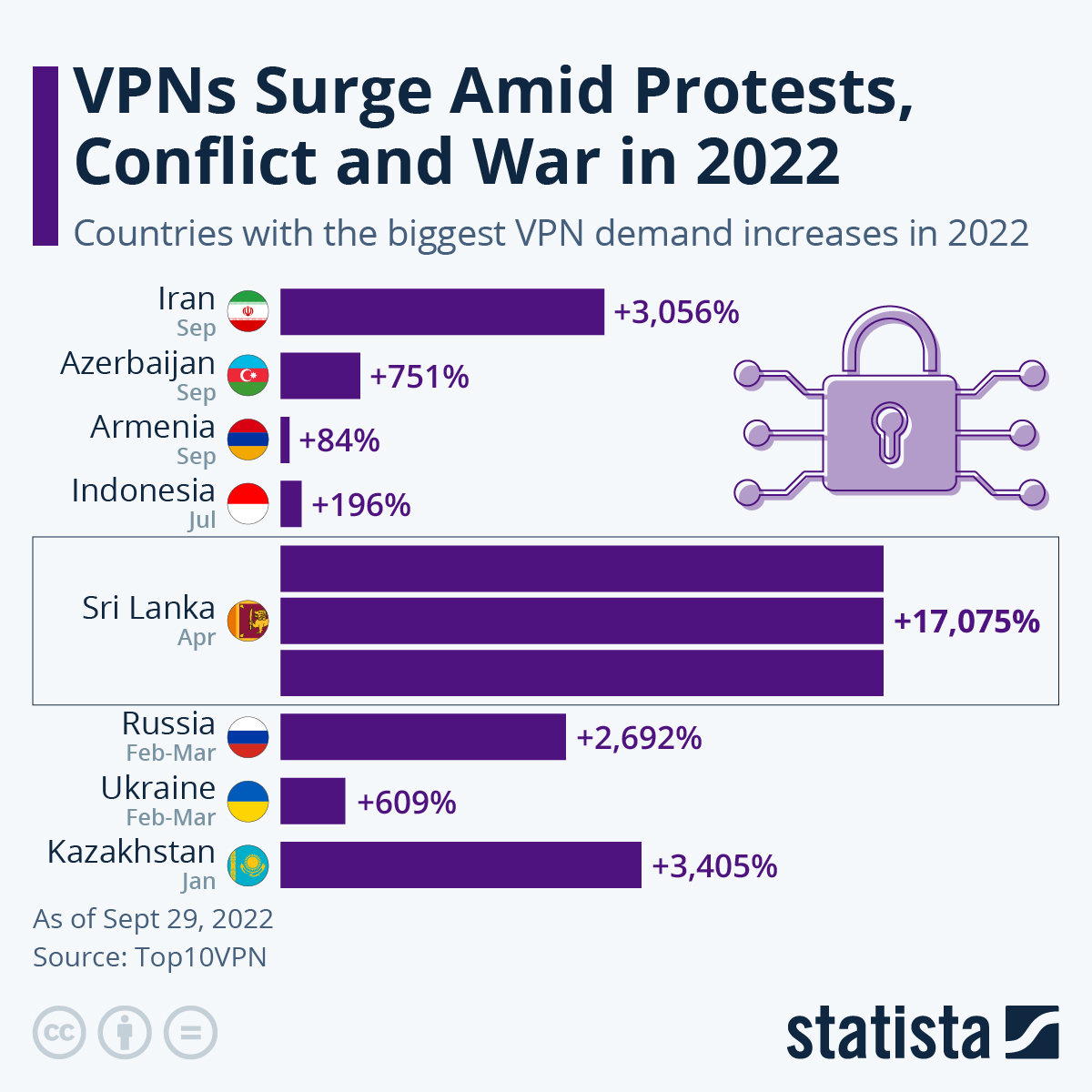

This wasn't Gabon's first brush with digital censorship, but the scale and swiftness were unprecedented. It also wasn't an isolated incident. What happened in Gabon reflects a troubling global trend: governments increasingly weaponizing internet shutdowns as tools of political control. From Myanmar to Nigeria, from Venezuela to Iran, dozens of nations have learned that cutting people off from the internet is a potent way to suppress dissent, control narratives, and consolidate power.

But the story of Gabon's blackout reveals something governments don't want us to understand: shutdowns are incomplete. They're blunt instruments. And ordinary people have tools to fight back. Understanding how Gabon's blocking worked, why citizens responded the way they did, and what this means for internet freedom worldwide tells us something crucial about power, technology, and human resilience in the digital age.

TL; DR

- The Blackout: Gabon blocked major social media platforms Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, and X without advance notice, citing national security concerns

- VPN Surge: Search volume for VPNs increased by 8,000% within hours, showing how rapidly people seek workarounds when connectivity is threatened

- Incomplete Control: Despite government efforts, citizens found ways to access blocked platforms, proving internet censorship is difficult to enforce completely

- Global Pattern: Gabon's shutdown follows a worldwide trend of internet restrictions during political instability, affecting billions of people

- Bottom Line: Social media blackouts remain a politically volatile tool that governments use during crises, but technological workarounds ensure they rarely achieve total information control

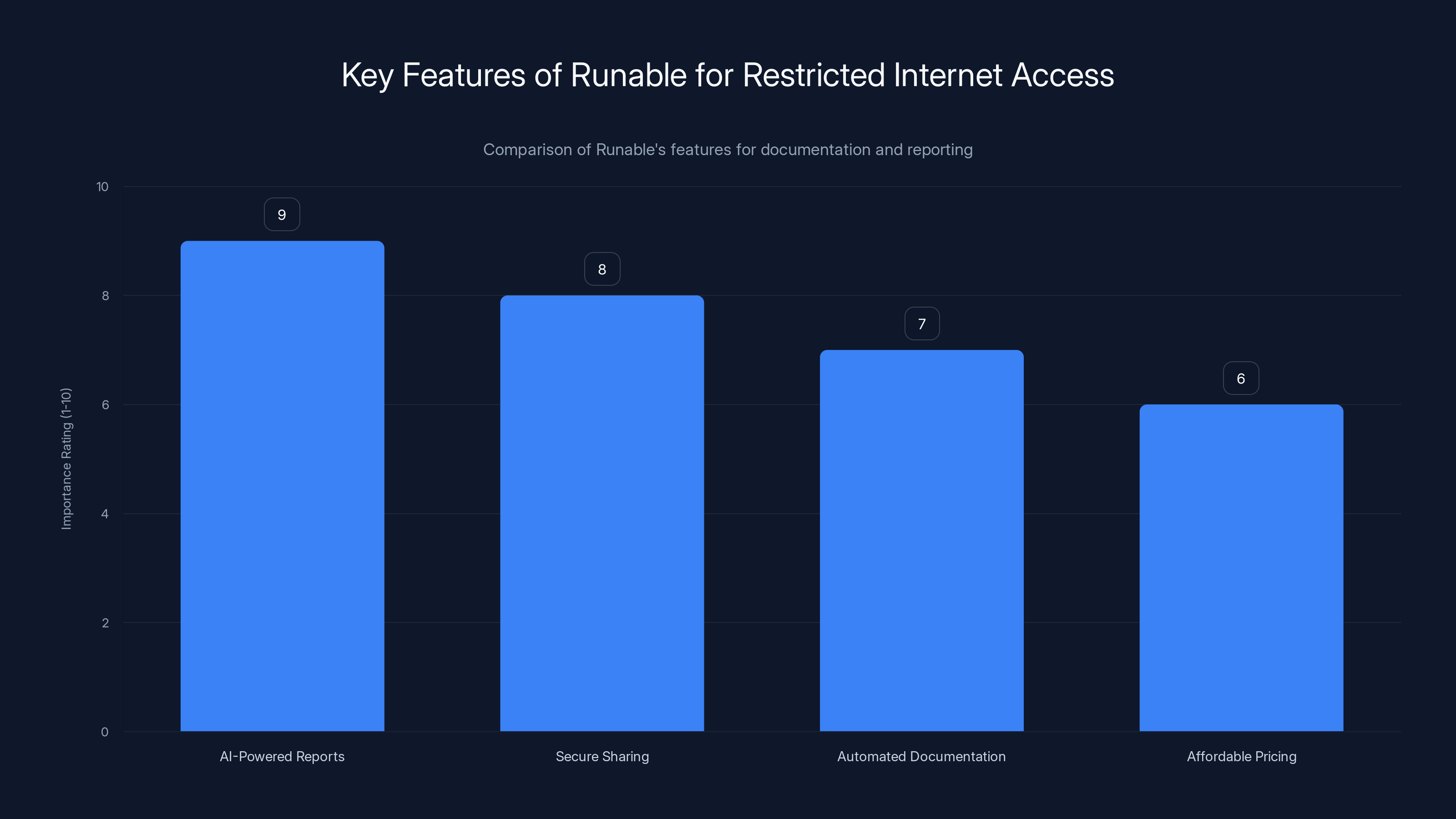

Runable's AI-powered report generation and secure sharing are highly rated features, crucial for users in restricted internet environments. (Estimated data)

What Sparked Gabon's Social Media Blackout?

The timing of Gabon's internet restrictions was no coincidence. The country was experiencing significant political turbulence that summer. In August 2023, General Brice Oligui Nguema had launched a military coup, overthrowing President Ali Bongo Ondimba and his family, who had controlled Gabon for decades.

What followed was a period of uncertainty. The military junta promised a transition back to civilian rule, but the timeline remained vague. Election schedules shifted. Constitutional reforms were debated. And crucially, civil society organizations began organizing resistance and criticism on social media platforms.

Facebook and WhatsApp had become the primary organizing tools for Gabon's young, digitally native population. Activists were coordinating protests. Journalists were breaking news that government media wasn't covering. Ordinary citizens were asking uncomfortable questions about the military's timeline and intentions.

For an interim government still consolidating power, this represented a direct threat to information control. The government didn't need to arrest everyone criticizing the junta. They just needed to cut off the platforms where criticism lived.

On September 1, 2024, they did exactly that. The blocks were implemented swiftly and broadly, affecting not just social media but also messaging apps and video platforms. The stated justification was protecting national security during a transition period. The practical effect was silencing the primary communication channel used by the country's most vocal critics.

This pattern repeats globally. Governments almost always block the internet during moments of political sensitivity: elections, military takeovers, protests, or major policy announcements. The blocking is presented as temporary and necessary. It rarely is either.

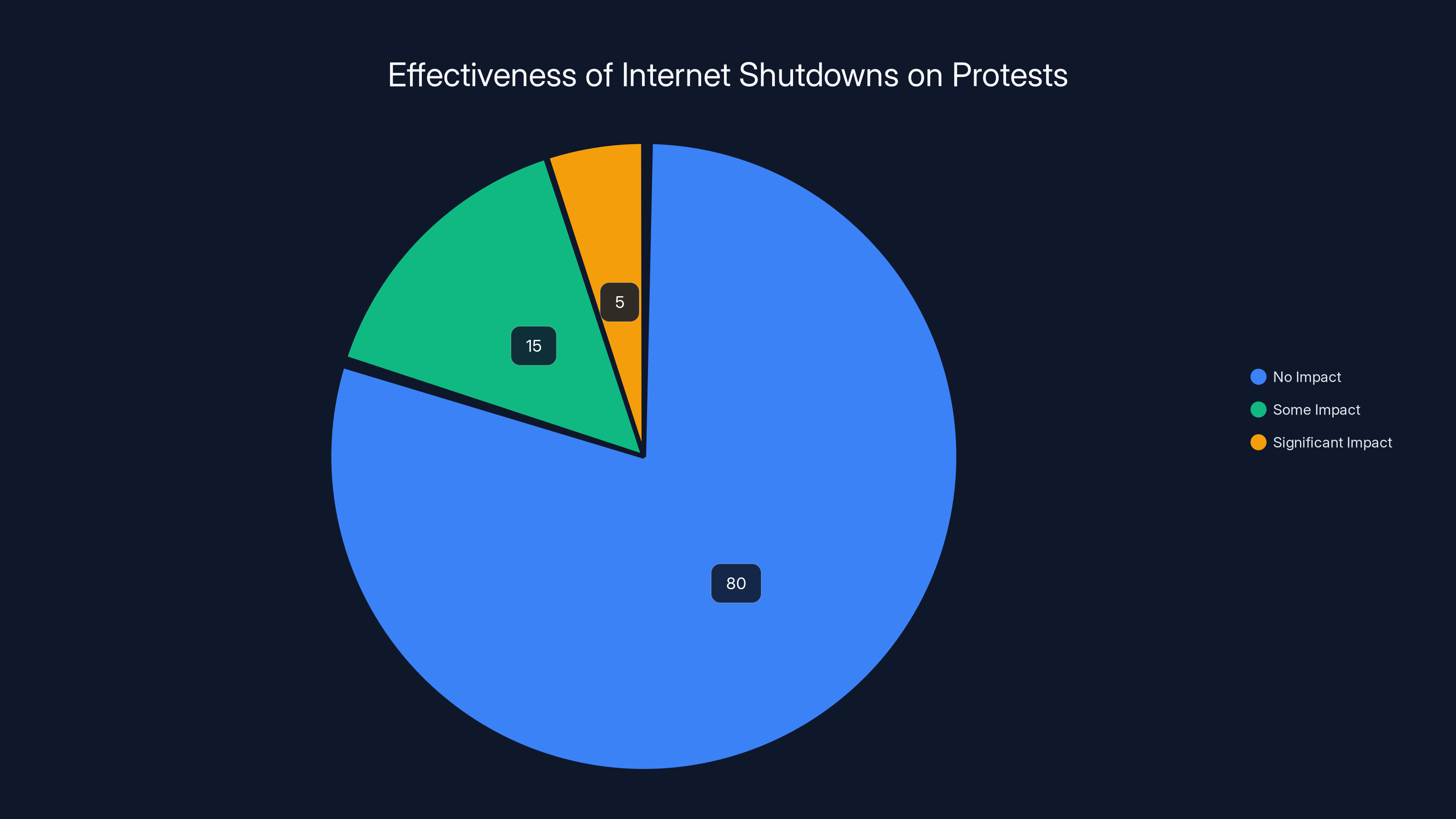

A study found that over 80% of internet shutdowns had no measurable impact on protest activity, indicating their ineffectiveness in stopping opposition.

The Mechanics: How Governments Actually Block the Internet

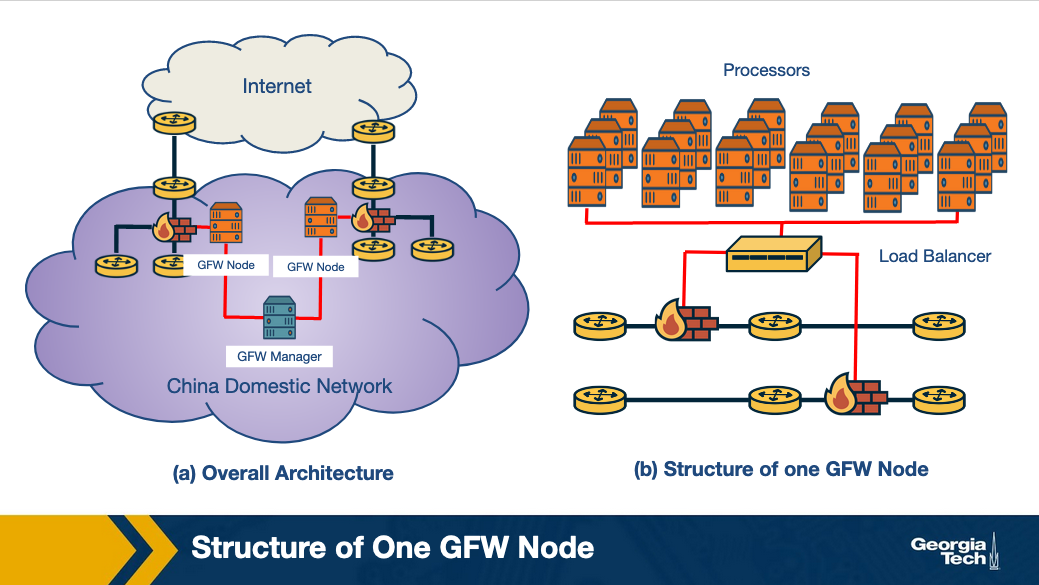

When we talk about social media blocking or internet censorship, most people imagine a simple on-off switch. In reality, it's far more complex. Governments have several tools at their disposal, ranging from crude to sophisticated.

The simplest approach is ISP-level blocking. Gabon's government works with the country's major internet service providers (ISPs), which include companies like Societe Gabonaise des Telecommunications (SGT) and Gabon Telecom. The government issues orders to these providers to block specific IP addresses and domain names associated with Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, and other services.

When you try to visit Facebook.com, your ISP's DNS servers return a false response or refuse to resolve the domain at all. Your browser never reaches Facebook's servers. From the user's perspective, the site simply doesn't exist.

But here's the problem with ISP-level blocking: it's not complete. It blocks the regular website, but WhatsApp is an app, not a website. Instagram can be accessed through various endpoints. Facebook runs on multiple IP ranges across multiple data centers globally. To truly block something, you need to identify every possible way a user might access it, then block all of those simultaneously.

Gabon's government attempted this through a combination of DNS filtering (preventing domain resolution), IP blocking (preventing direct connection to server addresses), and deep packet inspection (examining the content of data packets to identify and block specific services even when using encryption or VPNs).

Deep packet inspection is particularly aggressive. It works by examining the actual data flowing through internet pipes, identifying the patterns that characterize WhatsApp or Facebook traffic, and discarding those packets before they reach their destination. It's like a postal service that opens every letter, identifies those from certain senders, and destroys them.

Even this approach has limitations. Modern traffic encryption makes deep packet inspection less reliable. Services can disguise their traffic to look like other, permitted services. And most importantly, VPNs completely undermine the entire process by encrypting all traffic, making it invisible to ISP inspection.

Gabon's blocking strategy was ultimately a conventional approach: hit the obvious targets with DNS and IP blocking, hope that most users don't know about or can't access VPNs, and accept that technical users will find workarounds.

The Explosive VPN Response: Why 8,000% Isn't Hyperbole

The 8,000% increase in VPN searches during Gabon's blackout requires context to understand why it's so significant. VPN usage wasn't zero before the blackout. Gabon, like most countries, had some percentage of the population using VPNs for privacy or work-related purposes. Estimates suggest maybe 2-5% of Gabon's internet users had VPN experience.

But when social media disappeared, people who'd never considered a VPN suddenly needed one. A 2-year-old child crying because they couldn't video call their grandmother. A business owner who managed inventory through WhatsApp. A journalist who needed to file stories beyond government control. A teenager who'd grown up on Instagram. These weren't privacy enthusiasts. They were ordinary people facing an immediate, urgent problem.

So they Googled "how to unblock Facebook," "VPN Gabon," "access WhatsApp," and similar queries. They found tutorials on YouTube (which wasn't blocked). They shared links via Telegram (which wasn't initially blocked). They downloaded apps they'd never heard of before.

The search volume spike tells us that within hours, millions of people were searching for solutions. Some were in Gabon itself. Others were family members abroad trying to help relatives reconnect. The 8,000% figure, while dramatic, reflects the difference between baseline VPN interest and crisis-driven demand.

What's particularly interesting is that VPN adoption didn't stop when the blocks were lifted. Once people understood they had tools to evade censorship, those tools remained valuable. Journalists continued using them for reporting. Activists continued using them for organizing. Regular users appreciated the privacy benefits of VPN encryption.

This pattern has occurred in every country where internet shutdowns have happened. The blocks are eventually lifted. But VPN adoption persists at elevated levels indefinitely. Users learn that government control is possible, and they respond by adopting technical defenses. It's a technology arms race in slow motion.

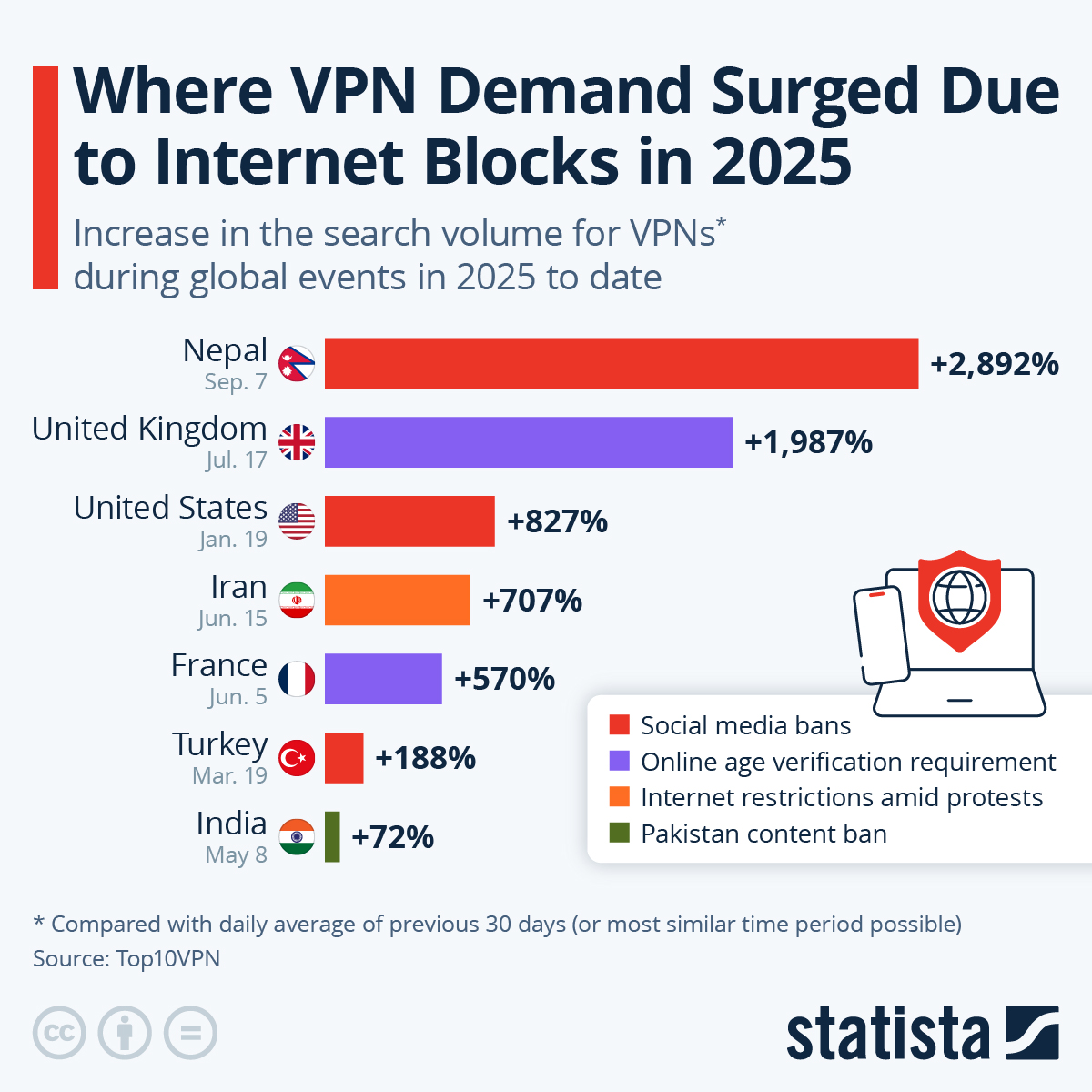

Gabon's experience isn't unique. During the 2022 Myanmar military coup, VPN searches increased by over 9,000%. When Sudan experienced internet shutdowns in 2023, VPN demand surged by 6,500%. In each case, the message was identical: when you take away people's freedom to communicate, they will find tools to restore it.

Estimated data shows a trend of decreasing effectiveness of internet shutdowns as populations become more tech-savvy and adopt VPNs.

Global Internet Shutdowns: A Widening Trend

Gabon's blackout didn't happen in isolation. According to research organizations tracking internet freedom, the number of internet shutdowns worldwide has been increasing steadily for the past five years.

In 2023, organizations documented shutdowns or restrictions in more than 90 countries. That's nearly half the nations on Earth. The shutdowns ranged from temporary social media blocks like Gabon's to complete internet blackouts affecting entire nations for weeks or months.

Venezuela has become notorious for frequent, prolonged shutdowns. During the 2024 election period, the government blocked X (formerly Twitter) for weeks, claiming the platform was spreading misinformation. Coincidentally, X was also the primary platform where Venezuelan citizens were discussing election irregularities and organizing opposition movements.

Bangladesh in 2024 experienced some of the most severe restrictions in years. During protests against the government's handling of university admissions, authorities implemented complete internet shutdowns affecting 168 million people. Mobile data was completely disabled. This didn't stop the protests. It just made them harder to coordinate and harder for international observers to document.

Iran has a well-documented history of shutting down internet access during periods of civil unrest. During the 2022 protests following the death of Mahsa Amini, the government implemented extensive restrictions on social media and messaging apps while also degrading overall internet speed and access. The explicit goal was to prevent organized resistance to the government.

What these cases share is a common logic: internet shutdowns are deployed by governments that feel threatened. They're not random. They're not mistakes. They're calculated political decisions to suppress information flow during moments of vulnerability.

The irony is that internet shutdowns often backfire. They're visible proof of government overreach. They're remembered by citizens who experience them. They create urgency around VPN adoption and technical privacy measures. And they intensify opposition by confirming what activists have been saying: the government will suppress your freedom of expression if given the chance.

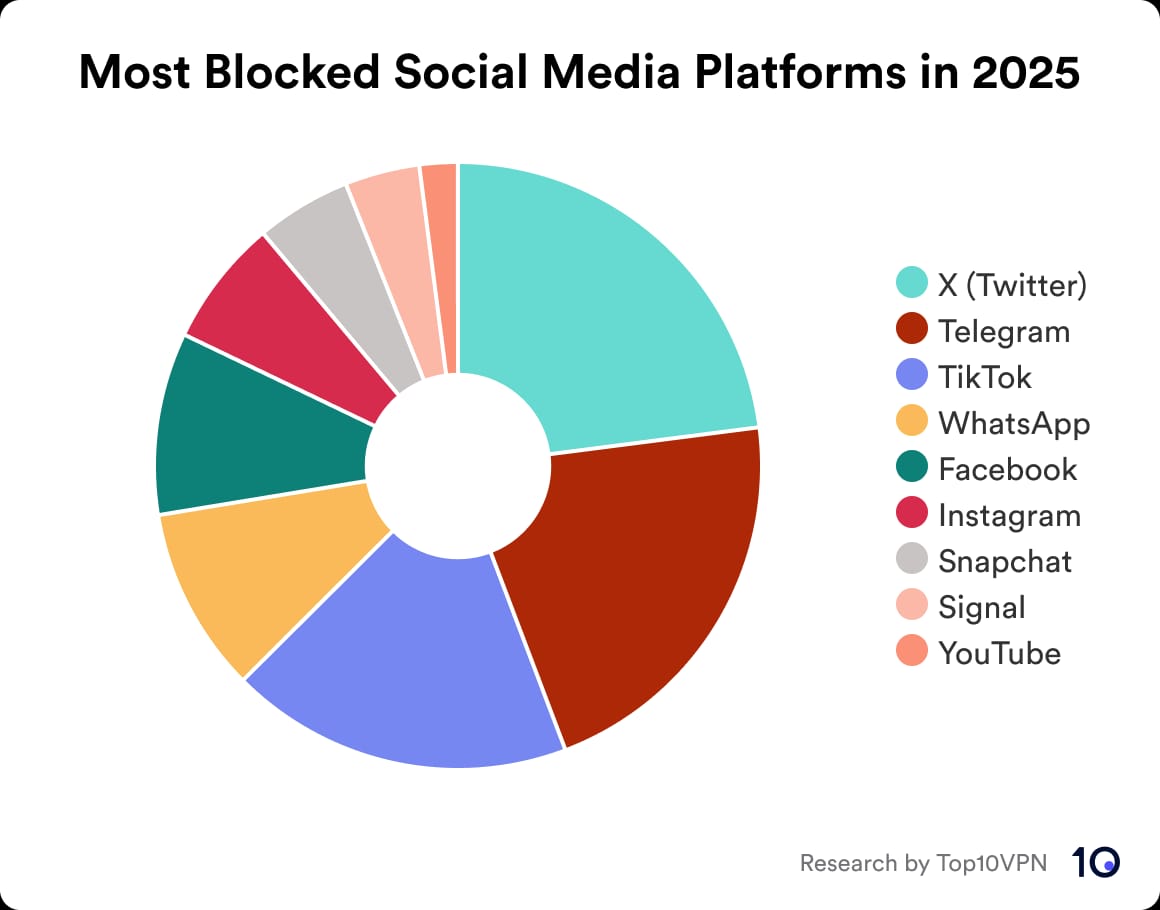

Who Gets Blocked and Who Doesn't: The Selective Nature of Censorship

One fascinating detail about Gabon's shutdown: it wasn't universal. Some platforms were blocked. Others weren't. This reveals something important about how internet censorship actually works in practice.

Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, and X were all blocked. But Telegram, a messaging app favored by privacy-conscious users and activists, wasn't initially blocked. Neither was Signal. Neither were many smaller social platforms and direct messaging services.

Why this selectivity? Several reasons explain it. First, blocking every platform is technically harder than it sounds. Governments typically target the biggest, most visible platforms because those are what most people use. Telegram has maybe 100 million daily active users globally. WhatsApp has 2 billion. The government prioritizes what matters most.

Second, there's a legitimacy question. Blocking a platform like WhatsApp (owned by Meta, a US company) can be framed as a stand against foreign companies or Western influence. Blocking Telegram (which provides strong encryption) looks like suppressing privacy itself, which is harder to justify publicly.

Third, and perhaps most importantly, government officials often use the same platforms as everyone else. If you're part of Gabon's government and you use WhatsApp to communicate with your colleagues or family, blocking it creates complications. Most governments exempt themselves from the restrictions they impose, which is why you often see evidence of government officials using platforms they've publicly blocked.

This selectivity creates an opportunity for activists. They migrate to the platforms that aren't blocked. They develop workarounds for the ones that are. If the government then blocks those platforms too, they migrate again. It's a constant chase, and the government can never stay ahead indefinitely.

During Gabon's shutdown, activists and journalists quickly migrated to Telegram and Signal. They shared information through encrypted group chats. They coordinated around the restrictions. Within days, the internet had partially re-routed around the government's blocks.

The 8,000% increase in VPN searches during Gabon's blackout highlights a massive surge in demand, which remained elevated even after the blackout ended. (Estimated data)

The Technical Workarounds: How People Beat Censorship

When the Gabon government blocked social media, they weren't expecting the blocking to last forever. They were buying time. Time for the political situation to stabilize. Time for opposition to lose momentum. Time for news cycles to move on.

But the blocking also bought time for technical countermeasures. Within hours, Gabonese citizens began implementing the most basic: VPNs.

A VPN is functionally simple. When you connect to a VPN, your internet traffic gets encrypted and routed through a server in another country. If you connect to a US VPN server, it appears to Gabon's ISPs that all your traffic is heading to the United States. They can't see what websites you're visiting or what apps you're using. They can only see encrypted data going to and from a VPN server.

The government could theoretically block known VPN server addresses. Some governments do this. China maintains a constantly-updated list of VPN server IPs and blocks them at the ISP level. But this is resource-intensive and never completely effective. VPN providers constantly move their servers to new addresses. They use obfuscation techniques to make their traffic look like normal HTTPS traffic. New VPN services launch regularly, staying ahead of government blocklists.

Beyond VPNs, users have other options. Proxy services work similarly to VPNs but with less encryption. They route traffic through a different server but don't fully encrypt it. Tor is an even more advanced tool. It routes traffic through multiple encrypted layers across a decentralized network, making it nearly impossible to trace or block.

Many Gabonese citizens accessed Facebook and WhatsApp through these tools within days of the block being implemented. The government's initial shutdown achieved its goal of cutting off the platforms for the masses. But technical users—and those willing to spend 10 minutes learning—had immediate access.

There's also a simpler workaround that governments can't really block: mobile data. Gabon's blocks targeted the fixed-line ISPs and mobile broadband networks. But if you could physically travel to another country with your phone, you'd get different ISP service and could access everything. Within days, stories circulated of people crossing the border to neighboring Cameroon or Equatorial Guinea just to check their messages and upload news.

Interestingly, the government recognized this and increased restrictions at border crossings, preventing people from leaving temporarily to access the internet. This escalation shows how internet freedom is intertwined with physical freedom of movement.

The Economic Impact: Businesses, Creators, and Livelihoods

When we discuss internet shutdowns, we often focus on the political dimensions. But there's an economic dimension that's equally important and often overlooked.

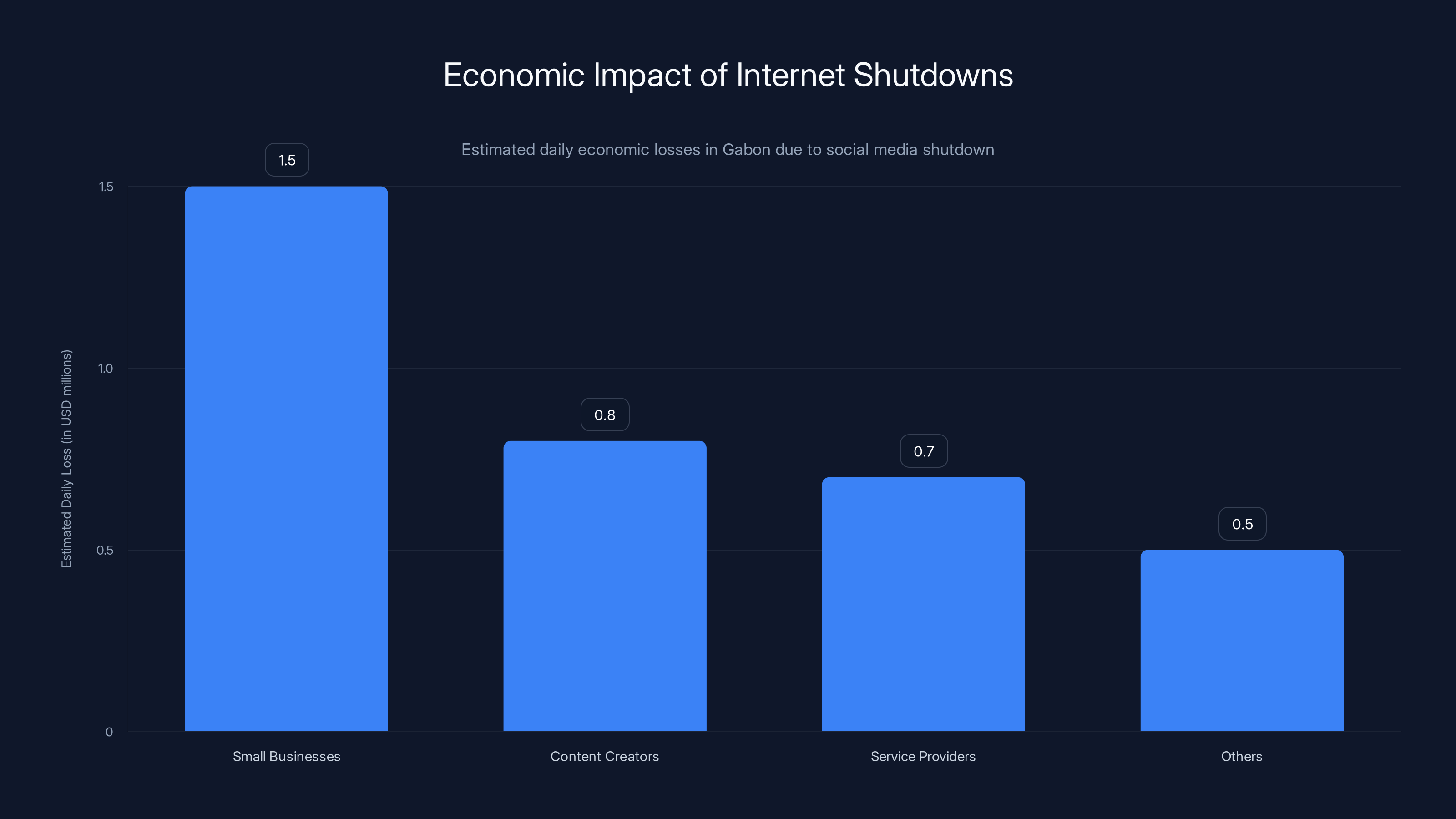

Gabon's social media shutdown was estimated to cost the economy millions of dollars in lost productivity and business activity per day. This wasn't hypothetical damage. It was real, immediate, and measurable.

Consider small businesses in Gabon that rely on WhatsApp for customer communication. A store owner who takes orders through WhatsApp. A service provider who schedules appointments through the app. A reseller who coordinates with suppliers. When WhatsApp goes offline, that entire business process breaks.

Some of these businesses could pivot to other communication methods temporarily. But many couldn't. The customer base expects WhatsApp. Switching everyone to email or phone calls isn't instantaneous. In a country where digital banking and online payment systems are still developing, WhatsApp isn't just a social app. It's an economic necessity.

Content creators faced similar challenges. Gabon has a growing population of people earning money through YouTube, TikTok, Instagram, and Facebook. When those platforms go offline, they can't create content. They can't interact with their audiences. They can't earn money.

One content creator interviewed during the shutdown described uploading content with a VPN at 4 AM when their internet was fastest and the network was least congested, trying to keep their audience engaged while the platforms were blocked. Others simply gave up and spent days earning nothing.

The shutdown also affected access to services that relied on these platforms for delivery. A ride-sharing service might coordinate drivers through Facebook groups. A delivery service might use WhatsApp for logistics. A healthcare provider might use Instagram for patient communication.

Research on internet shutdowns in other countries provides estimates. During India's 2019 Kashmir shutdown, which lasted weeks, the estimated economic impact was between $2-3 billion. During Sudan's 2023 shutdowns, early estimates suggested hundreds of millions in lost economic activity per week.

Gabon's shutdown lasted days, not weeks. But even that brief period represented significant economic loss. For a nation with a population of just 2.4 million and an economy heavily dependent on oil exports, losing millions in GDP for political control is a trade-off that most economists would question.

During Gabon's internet blackout, VPN searches surged by 8,000% on the first day, gradually decreasing as users found ways to circumvent restrictions. Estimated data.

Internet Shutdowns as Political Tools: The Intention Behind the Action

Why do governments shut down the internet? The question sounds simple, but the answer is complex. It's never just about security. It's about control.

Internet shutdowns serve multiple political functions simultaneously. First, they disrupt the organization of opposition. Protests are harder to coordinate without real-time communication. Activists can still organize, but it's slower and less efficient. It gives the government critical days to respond, arrest leaders, or change circumstances.

Second, shutdowns prevent the viral spread of information the government wants suppressed. During an election, if the government can shut down social media, it can control the narrative for days. It can make arrests out of the public eye. It can move military forces without opposition being documented. It can shape the initial media narrative before the platforms come back online.

Third, shutdowns are a signal of state power. They demonstrate to the population that the government can, if necessary, take away their communications. It's an implicit threat: challenge us and we'll cut you off again. This psychological impact is sometimes more important than the practical effect.

Fourth, shutdowns can be used to prevent journalists from reporting. If international journalists can't stay connected to file stories, they can't document what's happening on the ground. If domestic journalists can't access the internet to publish, government narratives go unchallenged.

Gabon's government achieved several of these goals during their shutdown. They prevented rapid social media coordination of opposition. They maintained narrative control for several days. They demonstrated state power. They were signaling to the population that they could do this again if necessary.

But these gains came with costs. The shutdown confirmed everything opposition groups had been saying about government overreach. It created international attention and criticism. It accelerated VPN adoption, making future shutdowns less effective. And it set a precedent: if the government does this again, people know how to respond.

This is why internet shutdowns are somewhat self-defeating in the long term. They work once. Maybe twice. But each time people learn. Each time more people adopt technical countermeasures. Each time the government's tool becomes less effective.

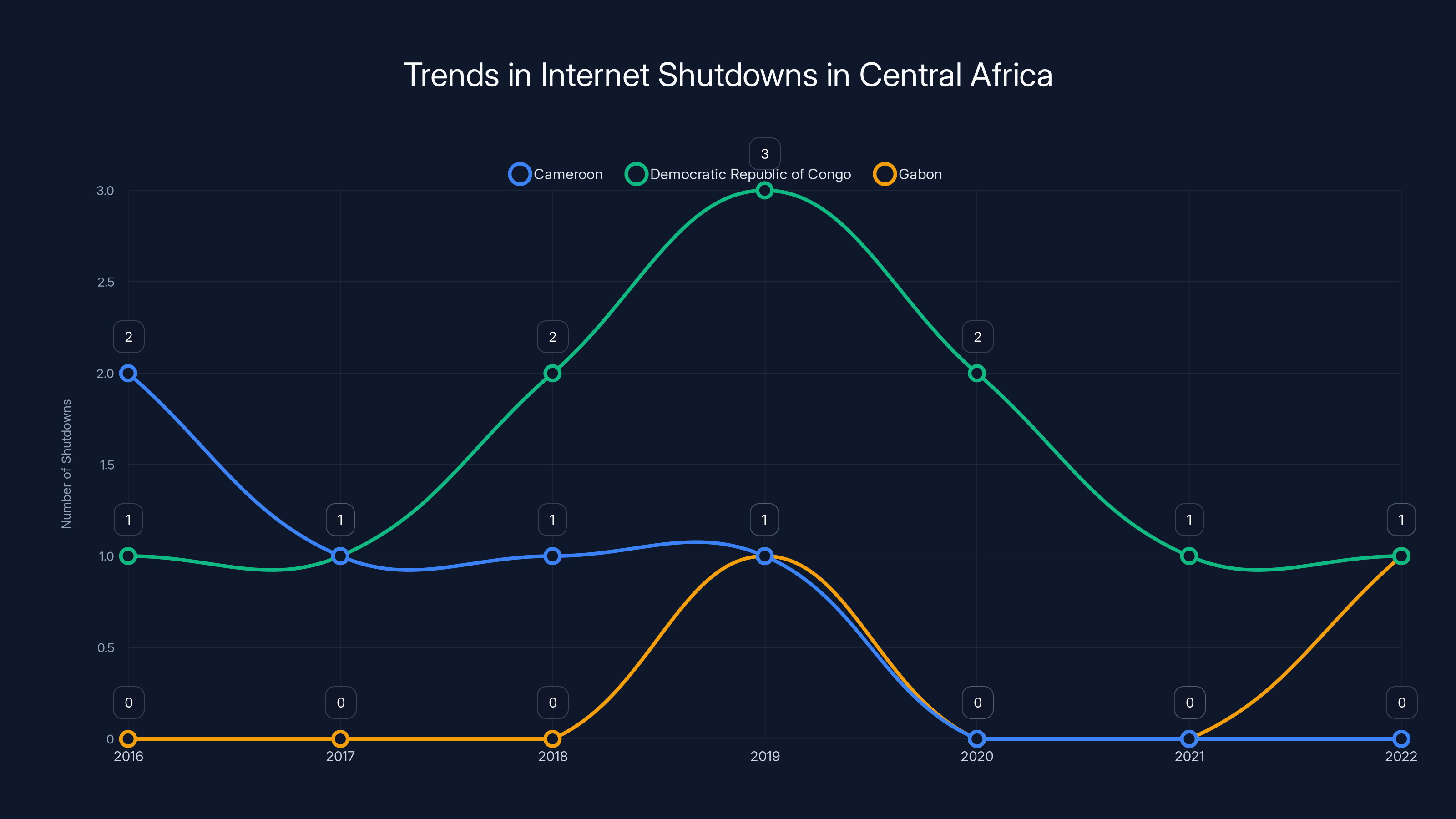

Regional Dynamics: Internet Freedom in Central Africa

Gabon didn't invent the shutdown strategy. The wider Central African region has a complex relationship with internet governance and freedom.

Cameroon, Gabon's neighbor, has a track record of internet restrictions. In 2016, the government shut down the internet in the Anglophone regions to suppress separatist movements. That shutdown lasted weeks. It achieved some of its stated goals but also generated international condemnation and documented human rights abuses that occurred while media couldn't report.

The Democratic Republic of Congo has experienced periodic shutdowns, particularly around elections. In 2019, during the presidential election, the government shut down internet access in specific regions where opposition support was strong.

Across West and Central Africa, there's a pattern. As governments face political challenges, they increasingly turn to internet shutdowns as a solution. The first time they try it, it works. But the effectiveness diminishes with each repetition as populations become technically savvy and VPN adoption increases.

Gabon's situation was unique because the government was newly formed and consolidating power. A military junta needs to establish legitimacy and control. Internet shutdowns are a way to do both simultaneously. But this approach is increasingly controversial even within Africa.

The African Union has made statements about the importance of internet freedom. Pan-African organizations have pushed back against shutdowns as a violation of human rights. But enforcement is weak. Individual governments can ignore continental pressure because there are no real consequences.

What's driving change is not regulation but technology adoption. As VPNs become mainstream and more people understand technical workarounds, shutdowns become less effective. Young, digitally native populations in these countries see VPNs as normal technology, not exotic tools. They expect to have access to global communication platforms.

Gabon's youth—the most vocal critics of the military junta—were precisely the population most likely to circumvent the shutdown. This demographic is the future of Gabon's politics. Their expectation of digital freedom will shape the country's relationship with the internet going forward.

The shutdown in Gabon led to significant daily economic losses, particularly impacting small businesses and content creators. (Estimated data)

International Response and Human Rights Implications

When Gabon shut down social media, international human rights organizations immediately condemned it. Organizations like Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and Reporters Without Borders issued statements emphasizing that internet shutdowns violate fundamental human rights to freedom of expression and information.

But here's the complexity: international condemnation of internet shutdowns rarely stops governments from implementing them. The cost of international criticism is often lower than the perceived benefit of controlling information during a political crisis.

What does affect governments is pressure from their own populations and economic consequences. When citizens demand internet restoration (which happens consistently), governments eventually comply. When businesses complain about lost revenue, officials listen. When other countries begin restricting trade or diplomatic relations in response, pressure increases.

Gabon's situation was particularly sensitive because the military junta was trying to establish legitimacy and eventually transition back to civilian rule. An extended internet shutdown could have delegitimized their claim to be a "transitional government" rather than a dictatorial junta. The international community would be justified in refusing to recognize their authority.

Within days of the shutdown, Gabon received pressure through various channels. The Gabonese diaspora in Europe and North America created international attention. International media covered the shutdown. The African Union issued statements of concern. And crucially, Gabon's government faces eventual elections. An extended shutdown would guarantee international observation and criticism that could undermine their legitimacy.

After less than a week, Gabon partially restored social media access. The restoration was gradual and incomplete initially, suggesting the government was testing whether citizens would comply once basic access returned. This is a common tactic. The shutdown demonstrates capability. Partial restoration shows flexibility. Full restoration is treated as a government gift.

The human rights implications of internet shutdowns are profound. When a government can cut off communication at will, it has tremendous power to suppress information about abuses. Documented cases of torture, extrajudicial killing, and disappearances are harder to verify when journalists can't report and citizens can't share information.

Several countries have justified internet shutdowns while simultaneously committing documented human rights abuses. The shutdowns weren't coincidental. They were enabling.

Internet freedom organizations now track shutdowns as a significant human rights concern. They argue, correctly, that the ability to communicate is foundational to all other freedoms. Once that ability is removed, other rights become harder to exercise or defend.

Technical Solutions and Future Outlook

As governments become more sophisticated with internet censorship, technologists are developing more sophisticated countermeasures. This arms race between censorship and circumvention is ongoing and accelerating.

One emerging technology is mesh networking. If people can communicate through decentralized networks that don't rely on centralized ISPs, government shutdowns become ineffective. Projects like the Free Network Foundation are working on technologies that allow communities to create their own local networks that can function independently of ISP infrastructure.

Another approach is satellite internet. Companies like Starlink are deploying satellite internet service globally. This technology is harder to shut down because it doesn't rely on terrestrial ISP infrastructure. If a government shuts down traditional internet access, citizens with satellite internet devices can still access global connectivity.

Gabon, like most African countries, is on Starlink's expansion roadmap. As satellite internet becomes available and affordable, it becomes a potential bypass for government censorship. This changes the calculus entirely. A government that can't shut down ISP access might still shut down traditional internet, but that becomes less effective if significant portions of the population have satellite access.

Encryption technologies continue to advance. Quantum-resistant encryption is being developed to protect against future cryptographic breakthroughs that could compromise current encryption standards. As encryption becomes stronger, government deep packet inspection (the technique of inspecting internet traffic to identify and block specific services) becomes increasingly ineffective.

On the policy side, there's growing recognition that internet freedom is an economic and development issue, not just a political one. World Bank research increasingly shows that countries with strong internet freedom experience better economic outcomes, faster innovation, and more transparent governance. This economic argument may eventually prove more persuasive to some governments than human rights arguments alone.

The long-term outlook suggests a continued escalation of both censorship and circumvention technologies. Governments won't stop attempting to control internet access. But their ability to do so comprehensively is diminishing due to technological changes that put circumvention tools in citizens' hands.

Lessons from Gabon: What We've Learned

Gabon's social media shutdown, while dramatic, offers several clear lessons that apply globally.

First, internet shutdowns are never comprehensive. There's always a way around them. Whether through VPNs, satellite internet, mesh networks, or physically traveling to another country, determined people will find ways to communicate. Government blocking is a speed bump, not a wall.

Second, shutdowns accelerate VPN adoption and technical literacy among general populations. The first time a government blocks the internet, people who never thought about VPNs suddenly seek them out. This creates lasting change. Once people know VPNs exist and how to use them, they tend to continue using them even after blocks are lifted, because they understand they might be needed again.

Third, shutdowns have real economic costs. They damage businesses, hurt workers, reduce productivity, and harm innovation. These costs often outweigh any political benefits, even if governments don't acknowledge it.

Fourth, shutdowns are signals of government weakness, not strength. A confident government doesn't need to shut down internet access. Resorting to shutdowns signals that a government feels threatened enough to take drastic action. Citizens recognize this, and it undermines government legitimacy rather than enhancing it.

Fifth, international attention and pressure matter, but citizen pressure matters more. When Gabon's government faced pushback from its own population and diaspora, combined with international pressure, they relented. Governments respond to pressure that threatens their power or legitimacy.

Sixth, technical tools like VPNs are democratizing access to circumvention. Twenty years ago, bypassing government censorship required significant technical knowledge. Today, anyone can download a VPN app and be up and running in minutes. This structural change makes comprehensive censorship increasingly difficult.

The Global Picture: Other Recent Shutdowns and Patterns

Gabon's shutdown happened within a context of increasing global restrictions. Understanding other recent shutdowns provides perspective on how common and dangerous this trend has become.

Bangladesh experienced severe restrictions in 2024 during protests against the government's education policies. Initial reporting suggested over 400 people died during protests, with the internet shutdown preventing international documentation. Activists reported that the shutdown lasted longer and was more comprehensive than Gabon's, affecting mobile data, broadband, and even some international connectivity.

Venezuela's ongoing restrictions are among the most stringent globally. During 2023-2024, the government blocked X, Instagram, and other platforms repeatedly. President Nicolás Maduro's government justified blocks as preventing misinformation and foreign interference, but the timing—always during elections or major protests—made the political purpose transparent.

Myanmar, facing international condemnation for military violence and persecution of the Rohingya minority, has used internet shutdowns repeatedly to prevent international monitoring and reporting. The government has also targeted specific communities and ethnic groups with disproportionate blocking, essentially creating digital apartheid.

Sudan's ongoing civil conflict has involved extensive internet shutdowns. Different factions have shut down internet access in territories they control as a tool of controlling information and restricting movement. The shutdowns have made it impossible for humanitarian organizations to coordinate relief efforts, contributing to humanitarian catastrophe.

What these cases share is a common playbook. A government faces a crisis (election, protest, conflict, investigation). The government claims the internet shutdown is temporary and necessary for security. The shutdown is implemented broadly, affecting business, journalism, and ordinary communication. International criticism occurs but is ignored. Eventually, the shutdown is lifted, but not before significant damage occurs to the economy, civil society, and human rights.

Each case also follows the same pattern of circumvention. People seek VPNs. Users migrate to platforms that aren't blocked. Technically adept people find workarounds. The shutdown becomes progressively less effective as it continues.

What's changed in recent years is speed. Gabon's VPN search surge happened within hours. In earlier shutdowns, it might have taken days for significant circumvention to develop. Technology and information about circumvention tools now spread nearly instantaneously.

Runable and Staying Connected During Restrictions

When internet access becomes restricted or unreliable, documenting and sharing information becomes critically important. Runable provides tools for creating documentation, reports, and presentations that help communicate important information even when traditional platforms are inaccessible.

For journalists and activists in regions experiencing internet restrictions, platforms like Runable that enable automated content creation can help quickly generate reports and documentation. Using Runable's AI-powered report generation starting at $9/month, users can transform data and notes into professional documents that can be shared via secure channels when internet restrictions occur.

The ability to rapidly create presentations and detailed reports becomes valuable for organizations operating in environments where traditional communication channels are unreliable or monitored.

Use Case: Generate comprehensive incident reports and documentation during internet restrictions or communications blackouts

Try Runable For Free

Future Predictions: Where This Is Heading

Based on current trends, we can reasonably predict how internet shutdowns will evolve.

Short-term (next 2-3 years): More frequent but shorter shutdowns. Governments will use shutdowns more often but for briefer periods, learning that extended shutdowns cause too much economic damage and international attention. These brief shutdowns will still disrupt but will be less transformative.

Governments will also become more selective, targeting specific platforms or geographic regions rather than broad internet shutdowns. We'll see more "surgical" blocking—shutting down Instagram in one province where protests are happening, while leaving it operational elsewhere. This is harder for citizens to circumvent and harder for international observers to notice.

Medium-term (3-7 years): Satellite internet coverage will expand significantly across Africa and other regions currently experiencing shutdowns. This will make geographic internet shutdowns less effective because people can maintain connectivity through satellite. Governments will respond by attempting to regulate or ban satellite internet devices, likely unsuccessfully.

VPN technology and other circumvention tools will become mainstream and user-friendly enough that average citizens (not just tech-savvy people) will use them routinely. This will shift the baseline expectation from "internet is available" to "internet might be blocked so I'll use circumvention tools routinely." This structural change will make shutdowns far less effective.

Long-term (7-15 years): The cat-and-mouse game between governments and circumvention technologies will reach an equilibrium. Comprehensive internet shutdowns will become technically difficult and economically costly enough that most governments abandon them except during extreme crises. Instead, governments will focus on other forms of information control: disinformation campaigns, algorithm manipulation, targeted surveillance, and content moderation rather than platform shutdowns.

This represents a shift from blocking access to shaping content. It's less visible but potentially more insidious. When the internet is shut down, everyone knows they've lost access. When algorithms are manipulated or disinformation spreads, people may not realize they're being censored. They might think they're seeing authentic information when they're actually seeing government-shaped narratives.

The challenge for the next decade will be ensuring that as technical shutdowns become less feasible, governments don't pivot to more sophisticated forms of information control that are harder to detect and fight.

Practical Guidance: Preparing for Internet Restrictions

For individuals and organizations in countries with internet restriction histories, preparation makes sense.

First, use a VPN proactively, not just during shutdowns. Regular VPN usage normalizes the technology and ensures you're familiar with how it works. It also obscures your baseline internet usage patterns, making it harder to identify when you switch to a VPN during a crisis.

Second, maintain offline backups of important information. If you're a journalist, activist, or person doing sensitive work, keep copies of documents, contact information, and communications outside the cloud. Cloud storage can be accessed by governments if they control ISP access.

Third, establish communication plans that don't rely on internet access. Know how to reach important contacts through phone calls, SMS, or in-person meetings. These shouldn't be your primary methods, but they should be available if internet access is lost.

Fourth, learn about mesh networking and offline communication tools. Projects like Briar (an encrypted messaging app that can work on peer-to-peer networks without internet access) are specifically designed for communicating when traditional internet is unavailable.

Fifth, if you're an organization, consider decentralized communication infrastructure. Don't rely solely on WhatsApp or Telegram. Have alternative platforms that your community knows how to access.

Sixth, advocate for stronger internet rights in your country. Push for legislation that criminalizes or restricts government authority to shut down internet access. These laws exist in some democracies and prevent shutdowns from occurring even during crises.

Most importantly, understand that internet shutdowns are not technical problems with technical solutions alone. They're political problems. The real solution is creating societies where governments don't feel threatened enough to shut down communication. That requires strong democratic institutions, independent media, rule of law, and respect for human rights. Technical tools help. But they're not sufficient on their own.

FAQ

What exactly is an internet shutdown?

An internet shutdown occurs when a government orders internet service providers to block access to the internet, specific websites, or specific services. Shutdowns can be complete (all internet access goes offline) or partial (only certain services are blocked). They can be nationwide or geographically targeted. Shutdowns are typically justified on grounds of national security, but the practical effect is to prevent citizens from communicating and accessing information about what the government is doing.

Why do governments shut down the internet?

Governments shut down the internet when they face political threats they believe they can suppress through information control. The most common triggers are elections, protests, military coups, or other major political instability. By shutting down internet access, governments hope to prevent rapid organization of opposition, control media narratives, and buy time to address political challenges. However, research shows that shutdowns rarely achieve these goals and often backfire by confirming government overreach.

How effective are internet shutdowns in stopping protests or opposition?

Studies of internet shutdowns in multiple countries show they are surprisingly ineffective at stopping protests or opposition. One comprehensive study found that over 80% of government-imposed shutdowns had zero measurable impact on protest activity. People continue organizing offline or through channels that aren't blocked. The most notable effect is usually political: the shutdown confirms what opposition groups have been claiming about government authoritarianism, which can increase opposition rather than decrease it. Shutdowns do slow organization compared to having internet, but they don't prevent it.

Can VPNs reliably bypass internet blocks?

VPNs are highly effective at bypassing most internet blocks, but they're not foolproof. VPNs work by encrypting all your traffic and routing it through servers in other countries, making it invisible to your ISP's blocking systems. However, some governments (notably China) maintain constantly-updated lists of VPN server addresses and block them at the ISP level. More sophisticated governments can identify VPN traffic patterns and block based on those patterns rather than specific servers. That said, VPN adoption defeats most shutdowns implemented in democracies or less technically advanced authoritarian states. The combination of VPNs with other tools (proxy services, Tor, obfuscation techniques) makes circumvention reliable in most scenarios.

What happened after Gabon lifted its social media block?

After less than a week of blocking, Gabon's government partially restored social media access, initially in limited form. This is a common tactic: shutdowns demonstrate capability and give the government leverage, while restoration is presented as a concession that shows flexibility. After full restoration, VPN usage remained elevated among Gabonese internet users. Once people learn they can be cut off, they tend to adopt technical tools to prevent that from happening again, even after access is restored. The shutdown had a lasting effect on how Gabon's population views internet access and government authority.

Are internet shutdowns legal under international law?

No. The United Nations, the African Union, and numerous international organizations have recognized internet access as a human right. Shutdowns are considered violations of the right to freedom of expression and the right to information. However, this legal status doesn't prevent governments from implementing shutdowns because enforcement mechanisms are weak. International organizations can criticize shutdowns but cannot enforce international law against individual governments. The practical protection against shutdowns comes from domestic pressure and technology adoption rather than international law.

How do I access the internet if it's shut down where I am?

If you face an internet shutdown, your options are: (1) Use a VPN if you installed it before the shutdown occurred; (2) Use proxy services or Tor if you can access them; (3) Travel to another country temporarily to use their internet; (4) Use satellite internet if you have access to a device with satellite capability. Prevention is easier than reaction, which is why experts recommend installing a VPN before you might need it. If you're caught without preparation, finding and installing circumvention tools during an active shutdown is much harder because the sites and services you'd normally use to download them are often blocked.

What's the relationship between internet shutdowns and human rights abuses?

During internet shutdowns, documented human rights abuses increase because journalists can't report, citizens can't share information on social media, and international observers can't communicate about what they're witnessing. Multiple studies of shutdowns coinciding with military operations, police violence, and other abuses show a consistent pattern: the shutdown enables abuses to occur out of public view. This is why human rights organizations treat internet shutdowns as serious threats to fundamental rights, not just inconveniences to connectivity.

Will internet shutdowns become more or less common in the future?

Based on current trends, internet shutdowns will likely decrease as complete shutdowns but shift toward more targeted restrictions on specific platforms or services. As satellite internet and other technologies make geographic shutdowns less effective, governments will shift toward other information control methods like algorithm manipulation, disinformation campaigns, and targeted surveillance. The underlying intent to control information won't change, but the methods will evolve. Societies with strong democratic institutions and rule of law will likely move away from shutdowns entirely, while authoritarian states will continue using them but in more limited, selective ways.

How can organizations prepare for possible internet shutdowns?

Organizations should maintain offline communication plans, backup communication channels that don't rely on internet access, decentralized leadership structures that can function if communications are limited, and regular training for staff on circumvention tools and security practices. Maintaining offline backups of important documents and establishing relationships with international partners who can amplify your organization's messaging if local platforms are blocked are also important. Most critically, organizations should advocate for legal protections against internet shutdowns at the policy level rather than relying entirely on technical workarounds.

Conclusion: Internet Freedom as a Democratic Imperative

Gabon's social media shutdown was a dramatic but ultimately temporary event. The platforms came back online. People regained access. Life continued. But the shutdown revealed something fundamental about the relationship between governments, citizens, and technology in the 21st century.

Internet shutdowns are not mistakes or overreactions. They're calculated political decisions by governments that feel threatened enough to suppress communication. The fact that they don't work completely—that VPNs defeat them and workarounds emerge quickly—doesn't matter to governments. Even partial effectiveness serves their purposes. Delays in organization matter. Gaps in media coverage matter. Psychological demonstrations of state power matter.

What matters more is that citizens learn from shutdowns. They learn they can be cut off. They learn that governments will suppress access if given the political opportunity. And they respond by adopting tools and practices that make future cutoffs less effective.

This arms race between government control and citizen circumvention will define internet policy for the next decade. Governments will develop more sophisticated tools for blocking and controlling information. Citizens and technologists will develop more sophisticated tools for maintaining access and circumventing control.

The outcome isn't predetermined. Societies with strong democratic institutions, independent courts, and respect for human rights will likely prevent comprehensive internet shutdowns because those shutdowns are incompatible with democratic principles. Authoritarian states will continue restricting internet access but will face an increasingly informed and technically sophisticated population that can circumvent those restrictions.

What's critical is that we don't normalize shutdowns as acceptable policy tools. Each time a government implements a shutdown without serious consequences, it makes the next shutdown more likely. Each time the international community protests but doesn't enforce consequences, it signals that shutdowns are tolerable. Each time citizens accept shutdowns as temporary inconveniences rather than fundamental violations of rights, it strengthens the next government that considers implementing them.

Gabon's experience is part of a broader global story about the tension between state control and individual freedom in a connected world. The outcome of that tension will determine whether the internet remains a tool of liberation and connection or becomes another instrument of state control. That outcome depends on what we, as citizens and advocates, do in response to shutdowns when they occur.

The VPN searches spiked 8,000% because millions of ordinary people understood something crucial: when government cuts you off, you find ways to reconnect. That human impulse toward connection and communication is more powerful than any technology governments can deploy to suppress it. If we nurture that impulse, protect the tools that enable it, and build societies that respect it, internet freedom can endure. If we ignore shutdowns as inevitable and move on, we surrender the fight. Gabon's people chose to resist. Their example matters for all of us.

Key Takeaways

- Gabon shut down major social media platforms for nearly a week, citing national security during a period of political transition following a military coup

- VPN searches increased 8,000% within hours as 2.4 million citizens desperately sought ways to restore internet access and communication

- Internet shutdowns are technical but ultimately incomplete, with multiple circumvention options including VPNs, proxies, and satellite internet becoming increasingly accessible

- Over 90 countries implemented internet restrictions in 2023, with Africa experiencing 40% of all shutdowns globally, reflecting a widening trend of digital censorship

- While governments use shutdowns to suppress opposition and control information, shutdowns often backfire by confirming concerns about authoritarianism and accelerating VPN adoption indefinitely

Related Articles

- Iran VPN Crisis: Millions Losing Access Due to Funding Collapse [2025]

- Billions of Exposed Social Security Numbers: The Identity Theft Crisis [2025]

- Abu Dhabi Finance Summit Data Breach: 700+ Passports Exposed [2025]

- EU Parliament's AI Ban: Why Europe Is Restricting AI on Government Devices [2025]

- Chrome Extensions Hijacking 500K VKontakte Accounts [2025]

- Japanese Hotel Chain Hit by Ransomware: What You Need to Know [2025]

![Gabon's Social Media Blackout: Why VPN Demand Surged 8000% [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/gabon-s-social-media-blackout-why-vpn-demand-surged-8000-202/image-1-1771436458375.jpg)