The Massive Data Breach That Changed Everything

A few months ago, cybersecurity researchers stumbled onto something that made even the most jaded security veterans sit up straight. An exposed database, left completely open on the internet, contained roughly 3 billion email addresses and passwords. But that wasn't the shocking part. The real gut-punch was discovering approximately 2.7 billion records that included Social Security numbers. According to a report by Wired, this breach underscores critical identity theft risks.

Let that number sink in for a moment. 2.7 billion Social Security numbers. That's more than eight times the entire U.S. population.

Greg Pollock, director of research at cybersecurity firm Up Guard, describes the moment of discovery with a mix of resignation and urgency. After years of finding exposed databases—each one heavy with passwords and sensitive data—he'd developed what he calls "fatigue." Finding another breach felt routine. But this one was different. The sheer scale of it forced his team to drop everything and validate what they were looking at.

What made this discovery particularly unsettling wasn't just the volume of data. It was the finding that much of this information hadn't yet been exploited by criminals. Millions of people had no idea their Social Security numbers were sitting exposed on a server anyone with an internet connection could access.

The database appeared to be hosted by a German cloud provider and seemed to contain a mashup of data from multiple historical breaches, potentially including the 2024 breach of National Public Data, a background-checking service. Someone had stitched together years of stolen information into one massive, vulnerable collection, as detailed in Wiz's blog.

Understanding the Scope: Just How Bad Is This?

Let's talk numbers, because they matter here. The researchers didn't download the entire dataset—it was too massive and too sensitive. Instead, they worked with a sample of 2.8 million records, which represents less than one percent of the total trove.

From that sample, Pollock's team discovered that roughly one in four Social Security numbers appeared valid and legitimate. That validation came from analyzing the data's internal consistency and checking against known patterns. If that ratio holds across the entire dataset, you're looking at approximately 675 million legitimate Social Security numbers exposed. That's a number that shifts from abstract to terrifying when you consider the potential impact, as highlighted by HIPAA Journal.

The researchers verified their findings by reaching out to people whose information appeared in the leaked database. What they discovered was deeply troubling: not all of these individuals had already been victims of identity theft. Not all of them had experienced any kind of breach at their end. This meant the database contained fresh ammunition for criminals—information that hadn't been weaponized yet.

Beyond the Social Security numbers, the breach included billions of email addresses and passwords. While not all of these records represent unique individuals, and not all are currently valid, the sheer quantity creates an enormous attack surface. Criminals could use these credentials to attempt account takeovers across multiple platforms, leveraging the same email and password combinations on different services, as reported by Security Magazine.

The timeline of the breach also reveals something crucial about data persistence in the digital age. By analyzing password trends in the sample data, researchers concluded that much of the information dated back to around 2015. How can they be so confident? Cultural references embedded in passwords tell the story.

One Direction, Fall Out Boy, and Taylor Swift appeared frequently in the passwords—bands and artists that dominated that era. Meanwhile, references to Blackpink, Katseye, and BTS were barely visible, appearing only as the data approached 2016 and beyond. It's a clever forensic technique that shows how much information we inadvertently encode about ourselves in our passwords.

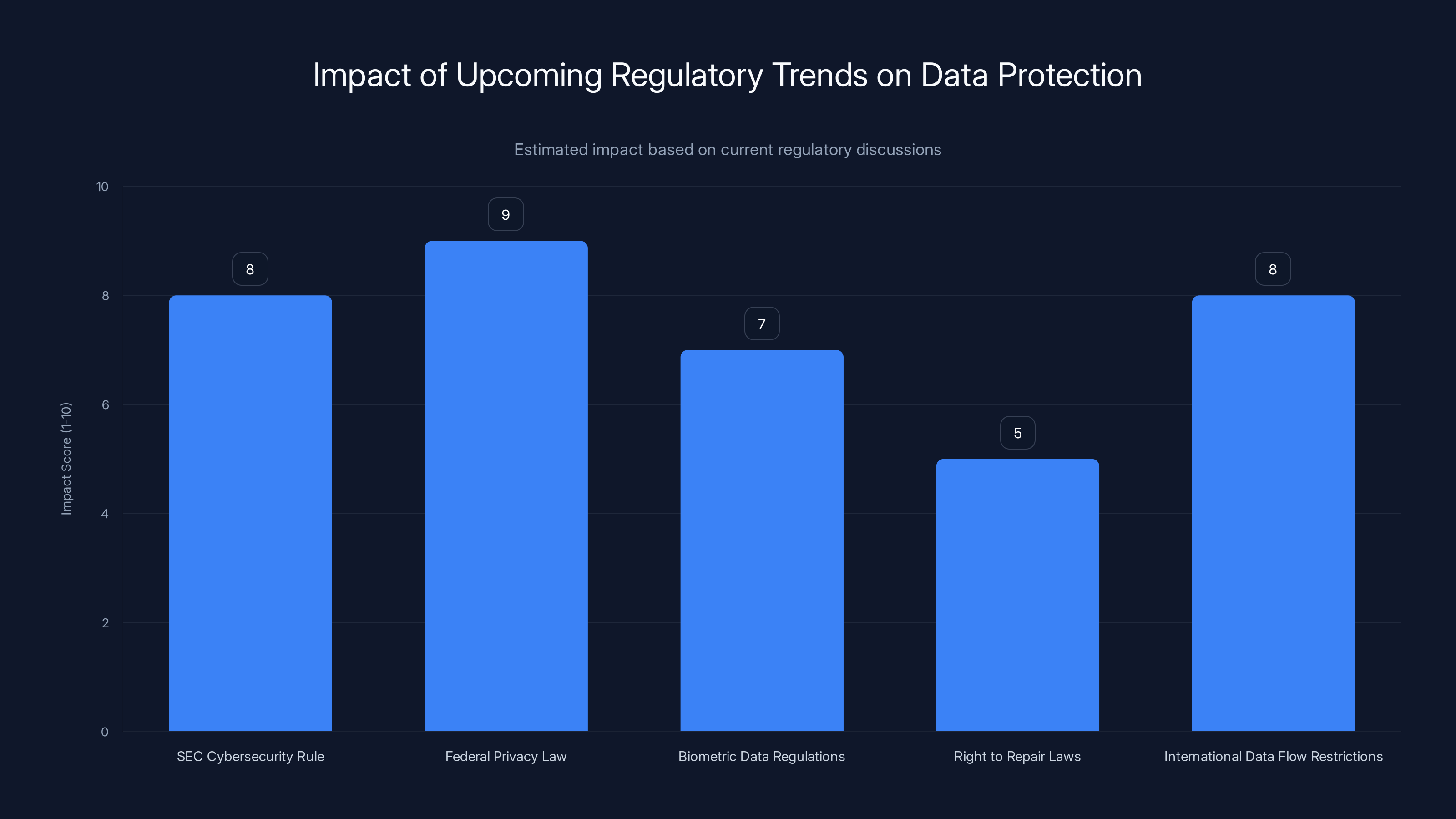

Estimated data shows that the Federal Privacy Law and SEC Cybersecurity Rule are expected to have the highest impact on data protection practices.

The Long Tail of Data Breaches: A Problem That Never Ends

Here's something that keeps security experts awake at night: data breaches don't expire. They don't fade away like old news. Instead, they create what Pollock calls a "long tail of uncertainty" that can haunt victims for decades.

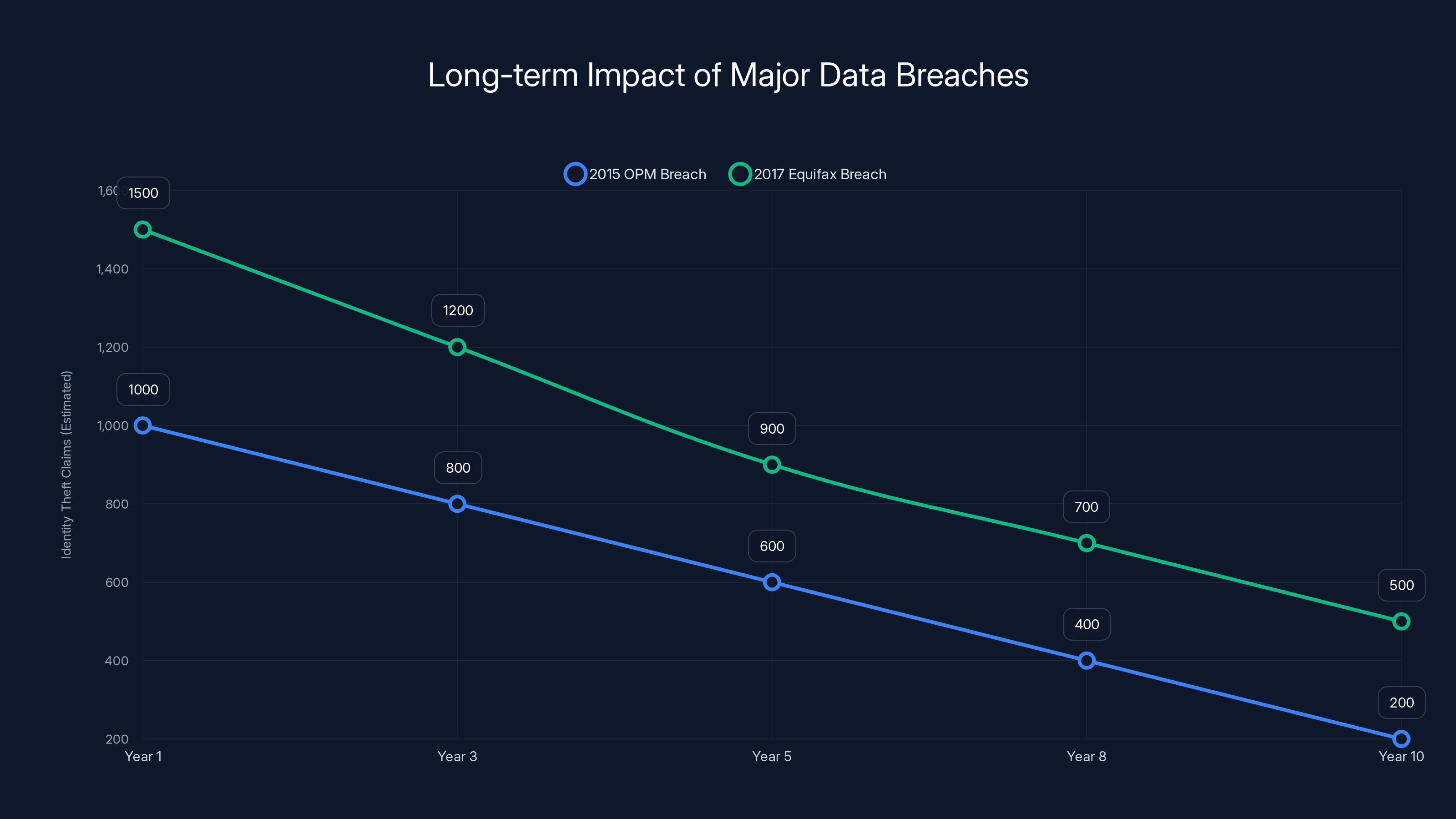

Consider the 2015 Office of Personnel Management breach, which exposed sensitive data on millions of federal employees. Nearly a decade later, people whose information was stolen in that breach continue to face identity theft risks. The same applies to the 2017 Equifax breach, which compromised data on 147 million people. That breach is eight years old, and people are still filing identity theft claims related to it, as noted by Pew Research.

Why does this happen? Because stolen data never actually disappears. Criminals compile it, recombine it, sell it, trade it, and recycle it. A dataset from 2015 gets merged with a dataset from 2017, which gets combined with new information collected through other means. The result is an ever-evolving collection of personal information that becomes increasingly valuable as it ages and accumulates.

This particular exposure illustrates that exact problem. The researchers found evidence that data brokers and cybercriminals routinely combine and recombine old datasets. This isn't a one-time incident. It's a systemic pattern where historical breaches never stop generating risk.

The erosion of data safeguards within U.S. federal government systems amplifies these risks. When the systems and processes designed to protect sensitive information weaken, the consequences ripple outward for decades. A mistake made today in how data is handled can create security problems that persist far into the future.

How This Data Ended Up Exposed: Following the Trail

Determining who created this massive database proved nearly impossible. The exposed collection appeared to be the work of someone—or more likely, some group—who had downloaded and compiled data from multiple historical breaches. But the original creator remained unidentified.

The database was hosted on Hetzner, a German cloud computing provider. When researchers couldn't identify the database owner, they went through the proper channels. On January 16, they notified Hetzner about the exposure. The company contacted its customer, and by January 21, the data was removed from public access, as reported by Taxpayer Advocate Service.

This timeline matters because it shows both the system working and the system's limitations. The data sat exposed for an unknown period of time—possibly weeks, possibly longer—before researchers found it. During that window, anyone could have downloaded the full dataset. Threat actors could have made copies. Competitors could have been selling access.

The decision to work through proper disclosure channels rather than immediately publicizing the breach demonstrates responsible security research. But it also highlights a persistent vulnerability in the current system: there's often a gap between when data first becomes exposed and when it gets taken down.

Identity theft claims persist for years after major data breaches, with a gradual decline over a decade. Estimated data highlights the long-term impact of breaches like OPM (2015) and Equifax (2017).

The Problem With Databases Left Wide Open: Security Theater vs. Reality

One of the most frustrating aspects of modern data breaches is how preventable they are. This database wasn't protected by cutting-edge encryption that criminals cracked. It wasn't protected by a sophisticated security system that was bypassed. It wasn't password-protected.

It was just sitting there. Anyone with a web browser could access it.

This represents what security professionals call a "misconfiguration." The database existed for a legitimate purpose—likely operated by a data broker or third party looking to aggregate and sell information. But somewhere along the line, access controls either weren't implemented or were accidentally removed. The result: one of the largest personal data exposures in recent history.

Misconfigured cloud storage has become a recurring theme in major breaches. A company sets up a database or server in the cloud, intends to restrict access, but either forgets to enable the security settings or enables them incorrectly. Days, weeks, or sometimes months pass with the data fully exposed before someone notices, as highlighted by TechRadar.

The irony is bitter: companies invest millions in sophisticated security infrastructure while making elementary configuration mistakes that undo all that protection. It's like building a fortress with impenetrable walls but leaving the front gate wide open.

Who Could Be at Risk: The Expanding Circle of Victims

The immediate question people ask when hearing about a breach like this is straightforward: "Am I affected?" The answer, unfortunately, is probably.

The 2.7 billion records represent different types of personal information. Some include Social Security numbers. Some include email addresses and passwords only. Some might include names and addresses. The diversity of data means that a massive breach doesn't necessarily threaten everyone in the exact same way, but it threatens almost everyone in some way.

If you've ever had an account with any major service—online banking, email, shopping, social media—there's a reasonable chance your information ended up in someone's database at some point. That database could have been breached. Your breached data could have ended up in this exposed collection.

People in certain professions face particularly high risk. Government employees, healthcare workers, financial professionals, and anyone with security clearances should be especially vigilant. Their personal information is more valuable to criminals precisely because it grants access to more sensitive systems.

But the risk extends far beyond white-collar professionals. A student whose email was breached five years ago. A retail worker whose store's payment system was compromised. A freelancer who posted on a now-defunct job board. All of these people could find their information in a collection like this.

The truly alarming finding from Up Guard's research is that some victims don't know they're victims. Their information has been exposed and is now circulating in criminal networks, but they haven't experienced the consequences yet. It's a kind of hidden time bomb that could activate at any moment.

Identity Theft: What Happens When Your Social Security Number Gets Stolen

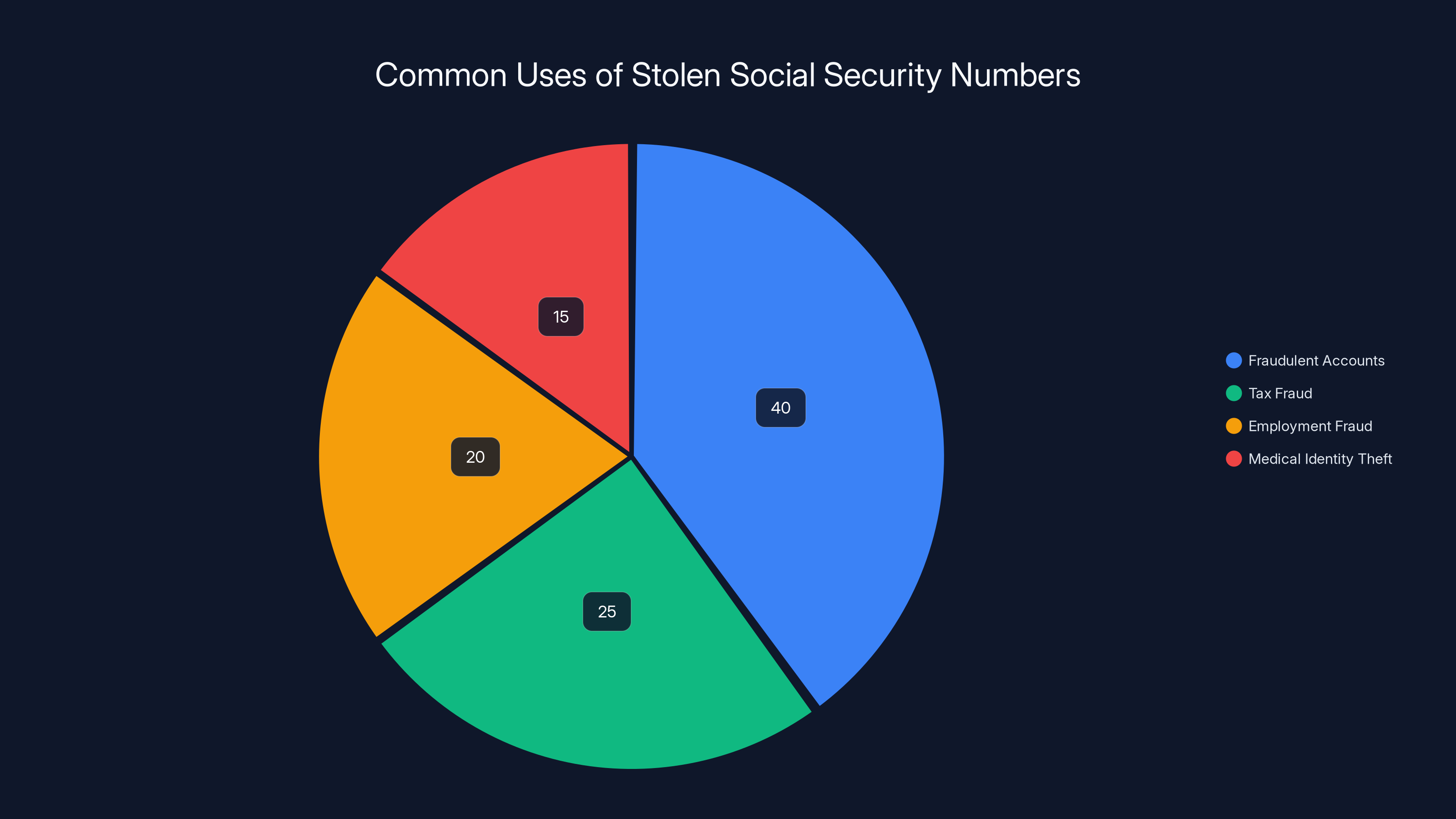

Let's talk about what actually happens when someone has your Social Security number and decides to use it. The risk isn't theoretical—it's concrete and multifaceted.

The most common use for a stolen Social Security number is opening fraudulent accounts in the victim's name. A criminal takes your SSN, combines it with personal information from the same database or from other sources, and applies for credit. They get a credit card, a car loan, or a mortgage. You don't find out until you check your credit report and see accounts you never opened or creditors start calling.

Other criminals use stolen SSNs for tax fraud. They file false tax returns on your behalf, claiming refunds that get directed to accounts they control. The IRS eventually sorts this out, but the process is time-consuming and stressful.

More sophisticated schemes involve employment fraud, where criminals use your SSN to get jobs at companies, working for a few months before disappearing and leaving you on the hook for unpaid taxes on income you never earned.

Medical identity theft is particularly insidious. Someone uses your SSN to access healthcare services, saddling you with fraudulent medical bills and potentially corrupting your medical records with information about conditions you never had.

The common thread across all these scenarios is that your SSN serves as a master key. With it, a criminal can impersonate you in ways that are difficult to detect and time-consuming to remediate.

Fraudulent accounts are the most common use of stolen SSNs, followed by tax fraud and employment fraud. Estimated data.

The Difference Between Data Exposure and Data Exploitation: Why Timing Matters

One of the most interesting findings from the Up Guard investigation is the distinction between data being exposed and data being exploited. These aren't the same thing, and understanding the difference is crucial.

Data exposure means your information has been compromised and is now accessible to threat actors. Data exploitation means someone has actually used that information to commit fraud or other crimes. The space between exposure and exploitation can range from minutes to months to years.

In many cases, the lag exists because criminals are strategic. They don't immediately use every piece of information they acquire. Instead, they might test a small sample, assess the quality of the data, and then decide whether it's worth their effort to exploit on a larger scale.

Some data sits in criminal marketplaces for months or years before being weaponized. A criminal gang might purchase access to a dataset, hold it for a few months while law enforcement attention dies down, and then begin opening fraudulent accounts. By that time, the original breach is old news and the victim's awareness of the risk has faded.

This is why the Up Guard researchers' discovery that some victims hadn't been exploited yet is so significant. It means criminals have fresh ammunition. It means the risk is current and ongoing, not historical.

Prevention Strategies: What You Can Actually Do

If you're thinking that there's nothing you can do to prevent your data from being exposed in breaches you have no control over, you're partially right. But there are concrete steps you can take to limit the damage if your information gets compromised.

Monitor Your Credit Reports Regularly. This is the single most important action. You're entitled to a free credit report annually from each of the three major credit bureaus. Check them. Look for accounts you don't recognize, inquiries from creditors you never applied to, and address changes you never authorized. If you spot suspicious activity, dispute it immediately.

Place a Credit Freeze. A credit freeze prevents anyone from opening new accounts in your name without a specific PIN. It takes about ten minutes to set up and is completely free. If you're not actively applying for credit, there's almost no downside.

Use a Credit Monitoring Service. Beyond checking your own reports, services like Credit Karma and Annual Credit Report.com provide ongoing monitoring and alerts when suspicious activity occurs. Many are free, and the cost of paid versions is cheap insurance.

Rotate Passwords Strategically. For critical accounts—banking, email, investment accounts—use unique, strong passwords. Password managers like 1 Password and Dashlane make this easier. For less critical accounts, reusing passwords is less risky than people think, as long as your critical accounts are locked down.

Enable Two-Factor Authentication. Even if someone has your password, two-factor authentication prevents them from accessing your account. It's not perfect, but it's much better than nothing.

Check If Your Information Has Been Exposed. Sites like Have I Been Pwned let you search for your email address in known breaches. It's a quick way to assess your exposure and take appropriate action.

Consider a Credit Lock Offering. Major credit bureaus now offer credit locks, which are similar to freezes but can be toggled more easily. The trade-off is that locks are less tamper-proof than freezes.

The Role of Data Brokers: The Middlemen Making Everything Worse

The existence of this massive exposed database points to a larger problem: data brokers. These are companies that collect, aggregate, and sell personal information about individuals to other businesses.

Data brokers aren't inherently criminal. Many operate legitimately, selling data to insurance companies, lenders, and marketing firms. But they're part of an ecosystem where personal information becomes a commodity traded across multiple organizations.

When data brokers collect information from multiple sources—including breached databases—they create massive repositories of personal data. These repositories become attractive targets for criminals. They're also susceptible to misconfiguration, as we saw with this exposure.

The problem is that consumers have almost no control over what information brokers collect or how they handle it. You didn't opt into this system. You probably don't even know which brokers have your information. Yet your data is being collected, stored, and sold without your meaningful consent.

Some states have begun requiring data brokers to register and follow certain data protection practices, but regulation is fragmented and often weak. The result is a Wild West environment where vast repositories of personal information accumulate with minimal oversight.

Identity theft victims face significant challenges, with emotional stress rated highest at 9/10. Estimated data based on typical experiences.

What Companies Should Be Doing: Security Basics That Keep Failing

From a corporate perspective, this breach should be a wake-up call. Not because the security challenge is unprecedented, but because the solution is so basic.

The database was exposed because it wasn't configured to be private. That's it. No sophisticated attack was needed. No zero-day exploits. Just someone—or more likely, someone's honest mistake—leaving data accessible to the public internet.

Core security practices that should prevent this:

Default Deny Access. Every database, every server, every cloud resource should start with a default of private. Access should only be granted explicitly to authorized users. This seems obvious, but it's violated constantly.

Regular Security Audits. Companies should regularly scan their infrastructure for misconfigured resources. This isn't expensive. It's not even particularly difficult. But it requires discipline and an actual security culture.

Data Minimization. Companies shouldn't store data they don't need. The fewer personal details you keep, the smaller the blast radius when you're breached. Some organizations are moving toward storing only the minimum information needed for their service and deleting everything else after a specified period.

Encryption at Rest and in Transit. Even if someone gains unauthorized access to a database, encryption makes the data useless without the encryption keys. This is table-stakes security.

Access Logging. Knowing who accessed what data and when is essential for detecting breaches early. Some companies spent weeks or months not knowing they'd been breached because they weren't logging access.

Employee Training. Many breaches happen because employees are tricked into revealing passwords or accessing insecure systems. Regular security training reduces this risk dramatically.

The frustrating reality is that none of these measures are cutting-edge or expensive. They're fundamentals that have been understood for years. Yet major breaches keep happening because companies fail to implement them consistently.

The Government's Role: Regulations That Actually Help

Individual companies clearly can't be trusted to protect personal information on their own. The economic incentives point the wrong direction. Companies benefit from collecting massive amounts of data, while the burden of a breach falls on victims. Until that equation changes, breaches will continue.

That's why regulation matters. GDPR in Europe and various state laws in the U.S. attempt to shift the balance. GDPR gives individuals rights over their data and imposes significant penalties for breaches. Some U.S. state laws, like California's CCPA, move in a similar direction.

But regulation remains fragmented and often inadequate. Different states have different rules. Federal standards are lacking. Many regulations focus on notification and remediation after breaches rather than prevention beforehand.

More aggressive regulations could mandate:

Data Minimization Requirements. Companies should be forced to justify what personal information they collect and delete it when it's no longer needed.

Security Audits and Certification. Companies handling certain types of data might be required to pass regular security audits by third parties.

Stronger Penalties for Negligence. If a breach happens because of misconfiguration, penalties should reflect that it's a preventable failure, not an unavoidable risk.

Right to Know. Individuals should have easy access to knowing what data about them companies hold and how it's being used.

Right to Delete. Individuals should be able to force companies to delete their data, with limited exceptions.

These measures would shift the incentive structure in ways that stronger security practices naturally emerge.

The Emerging Landscape: What's Changing in Data Protection

The cybersecurity landscape is shifting in response to these repeated, massive breaches. Organizations are recognizing that the old approach—collect everything, keep it forever, hope it doesn't get breached—is untenable.

There's growing momentum toward Zero Trust architecture, where every access request is verified rather than assuming that users inside a network are trusted. This is more complex to implement but significantly reduces the damage if a breach occurs.

There's also increased interest in Confidential Computing, where data remains encrypted even while being processed. This prevents even administrators from accessing sensitive information without authorization.

AI-powered security tools are becoming more sophisticated at detecting suspicious access patterns that might indicate a breach in progress. These tools can flag unusual database queries or access patterns and alert security teams in real-time.

Blockchain-based solutions are being explored for creating immutable audit trails that prove who accessed what data and when. While not a panacea, this adds transparency and accountability.

The good news is that these technologies are becoming more accessible. The bad news is they're expensive and complex, which means they'll likely only be adopted by larger organizations first. Smaller companies—which often hold equally sensitive data—will lag behind.

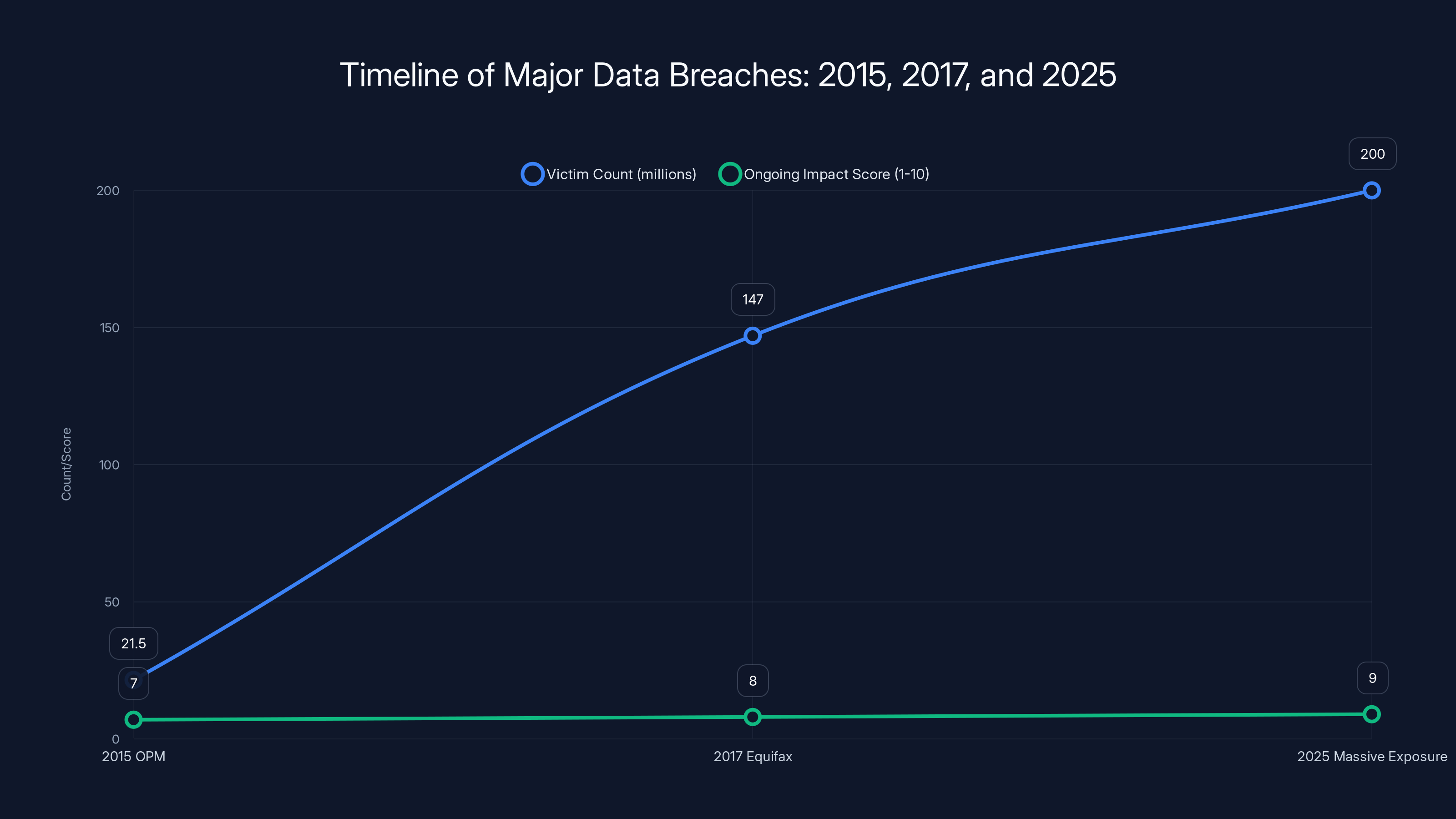

The timeline highlights increasing victim counts and ongoing impacts from major breaches in 2015, 2017, and 2025. Estimated data for 2025 shows a continued pattern of systemic failure.

Learning From the 2015 and 2017 Breaches: A Pattern of Failure

This massive 2025 breach doesn't exist in isolation. It follows directly from previous large-scale breaches that exposed the vulnerability of personal data systems.

The 2015 OPM breach exposed security clearance information on millions of federal employees and their families. Nearly a decade later, victims are still dealing with the consequences. Identity theft, unauthorized accounts, and ongoing fraud attempts continue.

The 2017 Equifax breach was perhaps even more consequential. One of the three companies that essentially controls American credit reporting suffered a breach affecting 147 million people. The response from Equifax was widely criticized as inadequate, and the company paid a settlement but was never fundamentally restructured.

What these breaches have in common is that they revealed systemic failures, not isolated incidents. When organizations holding vast amounts of personal information fail to protect that information, the damage reverberates for years.

The victims didn't volunteer to put their information at risk. They didn't consent to having it stored by these organizations. They simply existed in a society where personal data collection is ubiquitous and largely unregulated.

International Perspectives: How Other Countries Handle This

The United States approach to data protection is notably weaker than standards in other developed countries. Understanding these different approaches can illustrate what stronger protection might look like.

The European Union's GDPR is the gold standard for data protection regulation in many respects. It requires affirmative consent before collecting data, gives individuals strong rights to access and delete their information, and imposes penalties up to 4% of global revenue for violations.

Canada's PIPEDA provides similar protections, while Australia's Privacy Act and New Zealand's Privacy Act offer frameworks that sit between GDPR and U.S. standards.

Brazil's LGPD, passed in 2018, is based heavily on GDPR and provides strong protections for Brazilian citizens.

Japan has been strengthening its data protection laws, recognizing that companies lose competitiveness if they can't be trusted with data.

The United States, meanwhile, has sector-specific regulations like HIPAA for healthcare and GLBA for financial services, but no comprehensive framework. This fragmented approach creates gaps that criminals exploit and makes compliance inconsistent across industries.

For U.S. companies operating internationally, GDPR compliance is becoming de facto standard because it's easier to follow one strong rule everywhere than to maintain multiple different systems for different jurisdictions.

The Human Cost: What Victims Actually Experience

Statistics about breaches are important, but they can obscure the actual human toll. Let's talk about what identity theft actually means for individuals.

A victim might discover a fraudulent account on their credit report. They file a dispute, which should theoretically be resolved within 30 days. But creditors drag their feet, and it takes months to clear up. During this time, the victim's credit score drops, affecting their ability to get loans, refinance mortgages, or even secure housing.

A victim might receive calls from collection agencies about medical bills they never incurred. Each call is stressful. Each dispute requires documentation. The process is deliberately tedious—creditors know that many victims will give up rather than fight for justice.

A victim might file their taxes only to discover that someone already filed using their SSN, claiming their tax return. The IRS investigates, which takes months or years. The victim's refund is delayed. Their financial planning is disrupted.

Beyond the direct financial impact, there's psychological toll. Victims report feeling violated, anxious, and mistrustful of institutions designed to protect them. The emotional cost is real and underestimated in policy discussions.

The most infuriating part is that victims did nothing wrong. They didn't volunteer for the data breach. They didn't fail to protect information. They were simply harmed by companies' negligence and will spend years remedying that harm.

The European Union's GDPR is rated highest for data protection strength, while the United States lags behind with its fragmented approach. (Estimated data)

What Happens Next: The Future of This Breach

The immediate question after discovering a breach like this is what happens next. The database was taken down, but the data wasn't destroyed. Copies likely already exist in criminal marketplaces or on hacker forums.

In the coming weeks and months, criminals will begin testing the data. They'll try using the stolen credentials on popular websites to see if there's credential reuse. They'll attempt account takeovers. They'll file fraudulent tax returns and apply for fraudulent loans.

Security researchers will monitor dark web marketplaces and criminal forums to track how this data is being sold and used. This intelligence helps law enforcement understand the scope of exploitation.

Victims might eventually learn about the breach and take protective measures, but only if data brokers or companies notify them. Many won't. Many might not even realize which of their personal information was exposed.

Years from now, new breaches will likely contain data from this exposure mixed in with other stolen information, creating new combinations that criminals can exploit. The data will have a long and profitable life in criminal hands.

The only realistic bright spot is if this particular breach becomes a turning point that forces stronger regulation and better security practices. Previous breaches have occasionally catalyzed change. The Equifax breach, for example, led to some states increasing penalties for breaches. But systemic change remains frustratingly slow.

Preparing Your Personal Digital Defenses

While you can't control whether companies protect your data properly, you can take concrete steps to protect yourself against the inevitable exploitation.

Create a Personal Breach Response Plan. Know in advance what you'll do if your identity is stolen. Keep documents organized. Know the phone numbers for credit bureau disputes and the FTC's identity theft hotline.

Document Your Personal Information. Maintain a list of your Social Security number, credit card numbers, and other critical information in a secure place. If you need to dispute fraudulent activity, having this documentation saves time.

Use a VPN for Sensitive Transactions. While not foolproof, a VPN makes it harder for criminals to intercept your credentials when you're accessing banking or financial services online.

Verify Requests Independently. Criminals often impersonate banks and government agencies via email or phone. If someone claims to be from your bank, hang up and call the number on your statement. Don't use numbers from suspicious emails or texts.

Educate Family Members. Social engineering attacks often target less tech-savvy family members. Make sure older relatives know not to respond to suspicious requests or click links from unknown senders.

Review Privacy Settings on Social Media. The more information publicly available about you, the easier it is for criminals to piece together personal details needed for identity theft.

Consider Identity Theft Insurance. This won't prevent theft, but it covers some remediation costs if you become a victim. It's relatively inexpensive and provides peace of mind.

The Bigger Picture: Why This Keeps Happening

The fundamental problem isn't technology. It's economics and incentives. Companies benefit massively from collecting and keeping vast amounts of personal data. The cost of a breach—even a massive one—is often absorbed by victims or spread across consumers in the form of higher prices and reduced services.

A company that breaches millions of records might pay a fine of $10 million. But the value of the data they've collected over years might be billions of dollars. The math is clear: companies will take the risk.

Changing this requires either:

Stronger penalties that exceed the value of data. If breaching a million records meant paying $1 billion in fines, companies would suddenly prioritize security.

Individual liability for executives. Some countries are exploring jail time for executives responsible for breaches. This creates personal incentive to prioritize security.

Right to sue. Individuals should be able to sue companies that breach their data, not just file complaints with regulators. Class action lawsuits create financial consequences companies can't ignore.

Data minimization requirements. Companies should be forced to justify and limit what personal information they collect.

Without fundamental changes to this incentive structure, breaches will continue. Companies will apologize, promise to do better, and then return to the same practices because the business incentives never changed.

Steps Organizations Should Take Immediately

If you work for an organization holding personal data, here are concrete steps to reduce breach risk:

-

Audit Your Infrastructure. Systematically check all databases, servers, and cloud storage to ensure proper access controls are enabled. Use automated tools like Tenable or Qualys to find misconfigurations.

-

Implement Zero Trust Architecture. Stop assuming users inside your network are trusted. Verify every access request, regardless of source.

-

Encrypt Sensitive Data. Implement encryption for data at rest and in transit. This makes breached data useless without encryption keys.

-

Enable Logging and Monitoring. Log all access to sensitive data. Use SIEM tools like Splunk or Elastic to detect suspicious patterns.

-

Segment Your Network. Limit lateral movement if a breach occurs. Separate databases and systems so a compromise of one system doesn't automatically compromise all systems.

-

Practice Incident Response. Run tabletop exercises where your team practices responding to a breach. This isn't fun, but it's essential. When an actual breach happens, your practiced response will be faster and better.

-

Train Employees. Most breaches involve human error. Regular security training significantly reduces this risk.

-

Delete Unnecessary Data. If you don't need to keep customer data beyond a certain period, delete it. The less data you hold, the less damage a breach causes.

-

Implement Data Loss Prevention. Tools like McAfee DLP can prevent sensitive data from leaving your network without authorization.

-

Establish an Incident Response Team. Know in advance who responds to breaches, what they do, and how they communicate. Don't figure this out after a breach happens.

Regulatory Roadmap: What's Coming

Several regulatory trends are worth watching because they'll likely shape data protection for years to come.

SEC Proposed Rule on Cybersecurity. The Securities and Exchange Commission has proposed requiring public companies to disclose material cybersecurity breaches more quickly and to oversee cybersecurity more formally. This will likely force companies to invest more in security.

Federal Privacy Law. There's ongoing discussion about a comprehensive federal privacy law similar to GDPR. If passed, this would create a consistent baseline for data protection across the U.S.

Biometric Data Regulations. More states are regulating how biometric data (facial recognition, fingerprints, etc.) can be collected and used. This will likely expand to other personal data.

Right to Repair Laws. While not directly about data, right to repair laws prevent manufacturers from restricting access to systems, which could have security implications. Software security often depends on regular updates, which manufacturers can control.

International Data Flow Restrictions. Regulations in Europe and increasingly elsewhere restrict moving personal data internationally. This will force companies to rethink data collection and storage strategies.

These regulatory trends create new compliance burdens, but they also provide cover for security-conscious executives who want to do the right thing. When regulation requires something, it's no longer optional, and budget for it becomes easier to justify.

Moving Forward: Building a Culture of Security

Ultimately, preventing breaches like this requires a fundamental shift in how organizations approach data. Instead of treating security as a box to check, it needs to become core to how companies operate.

This means:

Treating security as a business enabler, not a cost center. Companies that handle data securely build customer trust and avoid massive breach costs.

Taking a systems-thinking approach where security is integrated into every process, not bolted on afterward.

Investing in employee training and development so security experts are available and empowered to do their job.

Building diverse security teams that think about problems from different angles. Homogeneous teams miss things.

Creating psychological safety where people report security concerns without fear of blame. Many breaches are found by regular employees who noticed something odd, but only if they felt safe raising the issue.

Focusing on the people whose data you hold. Not in a marketing sense, but genuinely understanding that you've been entrusted with information that could cause serious harm if mishandled.

This shift is happening, but slowly. Too many organizations still treat security as a burden rather than a priority. Until that changes, more breaches like this one will happen, and millions more people will spend years dealing with identity theft and financial fraud.

FAQ

What is the exposed database that Up Guard discovered?

In January 2025, cybersecurity researchers at Up Guard found a massive publicly accessible database containing approximately 3 billion email addresses and passwords, along with roughly 2.7 billion records that included Social Security numbers. The database appeared to be a compilation of data from multiple historical breaches, hosted on a German cloud provider and left completely unprotected with no access controls. By January 21, the database was taken offline, but not before it had been exposed to anyone with internet access.

How many valid Social Security numbers were actually exposed?

Up Guard researchers analyzed a sample of 2.8 million records from the database and found that approximately one in four Social Security numbers appeared valid and legitimate. If this ratio holds across the entire 2.7 billion records containing SSNs, the analysis suggests roughly 675 million Social Security numbers could be exploited. However, the researchers couldn't verify the entire dataset due to its massive size, so this is an extrapolation based on sampling rather than a definitive count.

Why does stolen data remain dangerous for so many years?

Stolen data creates a "long tail of uncertainty" because criminals compile, recombine, and recycle personal information indefinitely. A dataset from 2015 gets merged with data from 2017, creating new combinations that become more valuable over time. Additionally, criminals are strategic about exploitation—they test data, assess its quality, and then exploit it gradually to avoid detection. This means breaches can generate identity theft cases for decades. Historical breaches like the 2015 OPM breach and 2017 Equifax breach still produce identity theft claims years later.

How can I tell if my information was in this specific breach?

Up Guard has not released a public database where you can search for your information, likely due to privacy and security concerns. However, you can use Have I Been Pwned to check if your email address appears in any known breaches. Additionally, monitor your credit reports through Annual Credit Report.com for suspicious activity, place a credit freeze if you're concerned, and set up credit monitoring through your credit card companies or dedicated monitoring services.

What steps should I take if I think my Social Security number was exposed?

Start by placing a credit freeze with all three credit bureaus—Equifax, Experian, and Trans Union. This is free and takes about 10 minutes per bureau. Monitor your credit reports for suspicious accounts or inquiries. Consider setting up fraud alerts, which notify you if someone attempts to open accounts in your name. Enable two-factor authentication on your banking and email accounts. Check your tax filings for duplicate returns. For serious concerns, consider working with a credit counselor or consulting an identity theft lawyer, as both are often covered by victim assistance programs.

How does this breach compare to other major breaches like Equifax?

This database exposure involves more raw records (2.7 billion with SSNs) than the 2017 Equifax breach (147 million people), but the records come from aggregated historical breaches rather than a single new compromise. The key difference is that Equifax was breached through a sophisticated attack on an actively maintained company database, while this exposure resulted from misconfiguration of a cloud database. However, both create similar risks for victims—massive quantities of personal data available to criminals for decades to come.

What's the difference between a credit freeze and fraud alert?

A credit freeze prevents anyone from opening new accounts in your name without a specific PIN that only you have. It's free, permanent until you lift it, and is the strongest protection available. A fraud alert notifies potential creditors to verify your identity before extending credit, but doesn't prevent account opening. Fraud alerts last one year and must be renewed. For serious concerns, use both—place a fraud alert and a credit freeze. For ongoing monitoring, Credit Karma and similar services provide free credit monitoring and alert you to suspicious activity.

Why do companies leave databases exposed if it's so easy to prevent?

Misconfiguration happens because many companies lack mature security practices, training, and processes. Cloud infrastructure is new enough that many organizations haven't developed strong security practices around it. Additionally, the incentive structure favors companies that collect massive amounts of data without worrying about protection—breaches are treated as occasional unfortunate incidents rather than expensive failures. Until penalties for misconfigurations exceed the value companies derive from data collection, many companies will continue taking the risk.

What should companies do to prevent breaches like this?

Companies should implement several concrete practices: audit all cloud resources and databases to ensure proper access controls are enabled (default private, not public), implement Zero Trust architecture that verifies every access request, encrypt sensitive data at rest and in transit, enable comprehensive logging and monitoring of data access, segment networks to limit breach impact, train employees on security, and delete unnecessary data regularly. Using automated scanning tools like Tenable Nessus can identify common misconfigurations before they lead to breaches.

Is my password vulnerable if it appeared in this breach?

If your password was in this database, it's definitely compromised and shouldn't be used anywhere else. Change it immediately on any accounts where you've reused it. Use a password manager like 1 Password or Dashlane to create unique, strong passwords for every account. If you've reused passwords across multiple sites (which many people do), prioritize changing passwords on your most critical accounts: email, banking, investment, and healthcare. A compromised email password is particularly dangerous because email is often the recovery mechanism for other accounts.

What regulations are being proposed to prevent future breaches?

Several important regulatory efforts are underway. The SEC has proposed requiring public companies to disclose material breaches faster and demonstrate stronger cybersecurity governance. There's ongoing discussion about a comprehensive federal privacy law similar to GDPR. Multiple states have proposed or passed data minimization laws requiring companies to justify and limit data collection. International data flow regulations are increasingly restricting how companies can move personal data across borders. These regulations aim to shift incentives by making data protection legally required rather than optional.

Conclusion: The Persistent Vulnerability of the Modern Age

The discovery of this massive, exposed database containing 2.7 billion Social Security numbers represents more than just another breach. It symbolizes a fundamental imbalance in how modern society handles personal data.

Millions of people now have their most sensitive financial identifier floating in criminal networks, their worst fears about identity theft hanging like a sword of Damocles. They didn't choose to put themselves at risk. They didn't volunteer to have their information collected and stored. They simply existed in an economy where personal data is a commodity, handled by systems that prioritize convenience and profit over security.

What's particularly troubling is that the breach was entirely preventable. A database with appropriate access controls enabled wouldn't have been exposed. An organization with basic security practices would have caught the misconfiguration quickly. But prevention requires investment and discipline—investments that compete with other business priorities and discipline that many organizations lack.

The researchers who discovered this breach did the right thing, following proper disclosure practices and giving the data's host time to remediate before publicizing the finding. But this obscures a deeper truth: we rely on vigilant security researchers to catch these exposures rather than relying on companies to secure their systems in the first place.

Moving forward, protecting yourself requires a multi-layered approach. Monitor your credit reports. Use strong, unique passwords. Enable two-factor authentication. Place a credit freeze if you're genuinely concerned. Know how to respond if you become a victim.

But personal vigilance is only part of the solution. Real change requires regulatory reform that shifts the incentive structure so companies prioritize security because they must, not because they choose to. It requires penalties that exceed the value of data hoarding. It requires giving individuals rights over their data and the power to force companies to handle it responsibly.

The long tail of uncertainty that follows breaches like this one will haunt victims for years. Some will experience identity theft within months. Others will go years before criminals finally decide to exploit their information. The not knowing, the waiting for the other shoe to drop, is itself a form of damage.

Until the systemic failures that allow breaches like this to occur are addressed, millions more people will join the expanding circle of exposed identities, and society will continue paying the price in money, time, and emotional toll.

The good news is that solutions exist. They're not new or revolutionary. They're fundamental security practices that organizations should already be following. What's needed isn't better technology—it's the will to implement the technology we already have, and the regulation to make that implementation mandatory.

Until then, remain vigilant. Monitor your credit. Protect your passwords. And understand that while you're not responsible for companies' failures to secure your data, you are responsible for responding quickly when those failures inevitably occur.

Key Takeaways

- A database containing 2.7 billion Social Security numbers was exposed publicly before being removed, potentially affecting millions of Americans with identity theft risk.

- Analysis showed that approximately 1 in 4 Social Security numbers in the exposed data appeared valid and legitimate, suggesting 675 million compromised SSNs if the ratio holds across the entire dataset.

- The exposure demonstrates that data breaches create a 'long tail of uncertainty' where victims face ongoing identity theft risk for years after the initial exposure.

- The breach was caused by misconfiguration rather than sophisticated hacking, showing that many massive data exposures could be prevented with basic security practices.

- Victims should immediately place credit freezes, monitor credit reports quarterly, enable two-factor authentication, and understand that protection requires both personal vigilance and systemic regulatory change.

Related Articles

- Tenga Data Breach 2025: How a Phishing Email Exposed Customer Data

- Abu Dhabi Finance Summit Data Breach: 700+ Passports Exposed [2025]

- EU Parliament's AI Ban: Why Europe Is Restricting AI on Government Devices [2025]

- Chrome Extensions Hijacking 500K VKontakte Accounts [2025]

- EU Parliament Bans AI on Government Devices: Security Concerns [2025]

- TP-Link Texas Lawsuit: Chinese Hackers, Security Lies, and What It Means [2025]

![Billions of Exposed Social Security Numbers: The Identity Theft Crisis [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/billions-of-exposed-social-security-numbers-the-identity-the/image-1-1771436295723.jpg)