Gay Tech Mafia: Silicon Valley's Networks, Power, and Influence [2025]

Silicon Valley has always been a place where fortunes are made in whispers. A venture capitalist's nod can mean millions. A founder's recommendation can launch a career. An investor's trust can change an entire company's trajectory.

For years, a particular rumor has circulated through the hallways of startup offices, the bars of Sand Hill Road, and the group chats of tech workers everywhere. It's been mentioned in passing at conferences, debated on social media, and discussed with a kind of knowing nod at venture capital parties. The rumor, in its simplest form, goes like this: gay men run Silicon Valley. Not just work there. Not just succeed there. Run it.

The claim arrives wrapped in layers of complexity. Sometimes it's said as a joke. Sometimes as conspiracy. Sometimes as observation. Rarely is it treated as a serious question worth examining. When you mention the idea in polite tech company, you get a reaction somewhere between a laugh and a yawn—that particular kind of response that suggests everyone already knows something you're just catching up to.

But what does the rumor actually mean? Is there a coordinated network of LGBTQ+ leaders shaping the industry? Or is this just modern mythology, the kind of story we tell ourselves about power and access in industries we don't fully understand? How much of what we believe about Silicon Valley's leadership reflects actual influence, and how much reflects our own biases about who belongs in positions of power?

These questions matter because they sit at the intersection of several critical conversations. They're about diversity in technology leadership. They're about how power actually circulates through networks. They're about what we assume about successful people based on their sexuality. And they're about the gaps between perception and reality in one of the world's most influential industries.

What's emerged over the past few years isn't a simple confirmation or debunking of the "gay tech mafia" myth. Instead, it's something more nuanced and more interesting. There's real LGBTQ+ representation in tech leadership. There are genuine networks and relationships that have shaped the industry. There's also a lot of projection, assumption, and conspiracy thinking layered on top of that reality. Understanding the actual landscape—rather than the rumor—requires looking at the facts, the history, and the broader patterns in how Silicon Valley operates.

The Origins of the Rumor

No one can quite pin down when the "gay tech mafia" narrative took hold. It emerged gradually, gathering steam over the past decade or so, becoming more pronounced around 2020 and intensifying significantly in 2024 and 2025. But the conditions that made the rumor possible existed long before it became a common talking point.

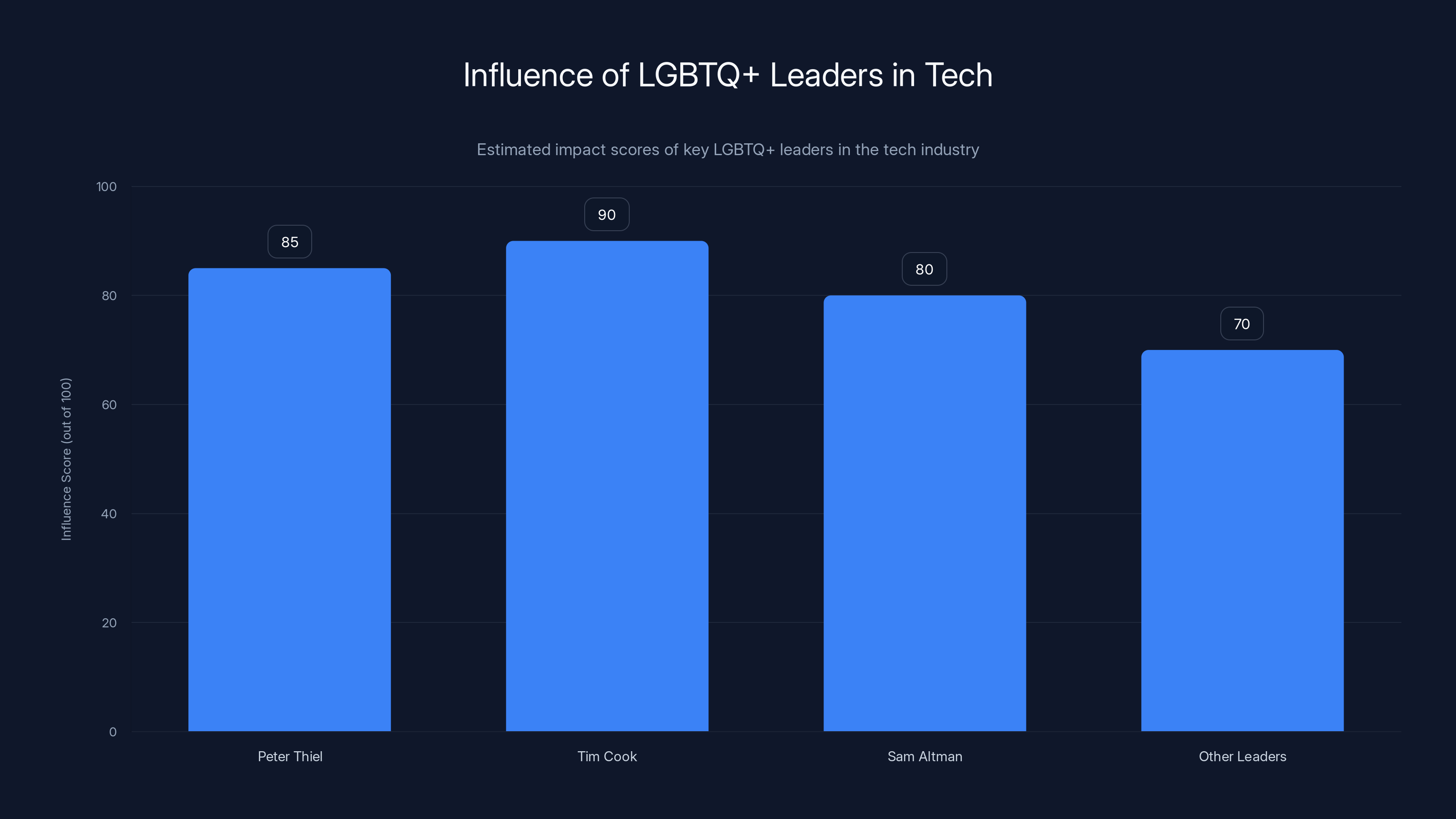

Part of the story traces back to the very real visibility of openly gay leaders in tech. Peter Thiel, the venture capitalist and PayPal co-founder, was perhaps the first high-profile openly gay tech executive to achieve genuinely outsized influence. Tim Cook took over as CEO of Apple in 2011 and came out publicly in 2014, making him arguably the most powerful openly gay person in the world at that moment. Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI, came out as gay in 2014 and has been a major figure in the AI boom. Keith Rabois, the longtime venture capitalist and entrepreneur, has been a visible and influential figure in the startup ecosystem.

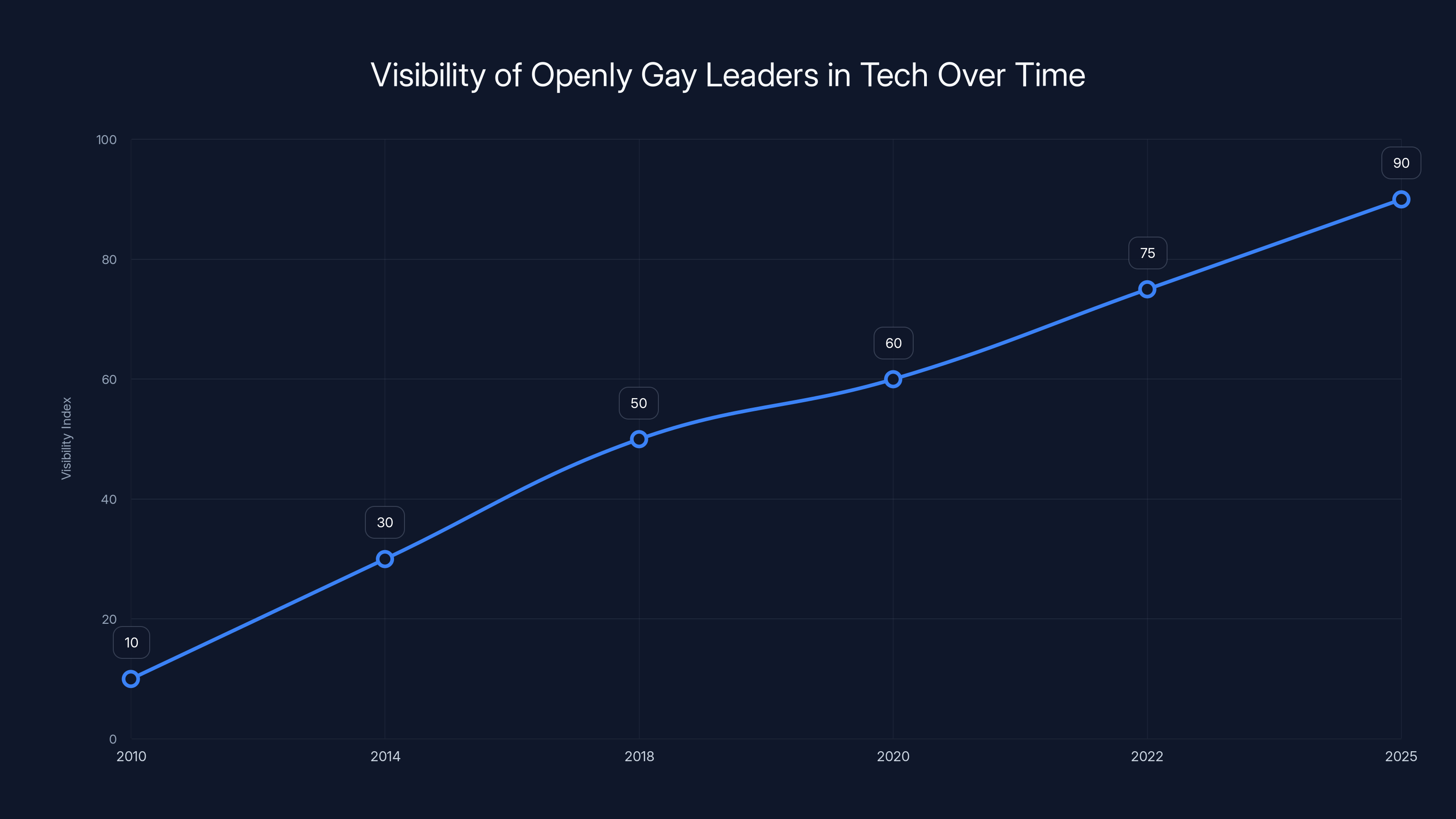

These weren't isolated examples. Over the past fifteen years, LGBTQ+ people have become increasingly visible in positions of power in Silicon Valley. Some of this reflects changing social attitudes. Some of it reflects that LGBTQ+ people, like any other group, are drawn to industries that offer opportunity and impact. But the visibility created a backdrop for a particular kind of story.

That story got amplified by the social dynamics of Silicon Valley itself. The tech industry, particularly venture capital and the startup world, operates through networks. You get introduced to investors by people who know investors. You build your company using connections you already have. You join accelerators and incubators where you meet other founders who become your peers. The entire system runs on relationships and introductions and the sense that certain people "know" certain other people.

When people started noticing that several visible tech leaders were gay, the rumor mill had something to work with. If powerful people in an industry are all connected to each other, and if several of those people happen to be gay, the narrative becomes obvious: they must be connected because they're gay. They must be looking out for each other. They must constitute some kind of organized network.

The rumor also resonated because it tapped into something real about how power works. The reality is that networks in Silicon Valley do operate along various lines. People from Stanford know other people from Stanford. People who went to Y Combinator know other Y Combinator founders. People who worked at Google know other Google alums. These networks are real, and they do provide genuine advantages. The question is whether "gay network" is a meaningful category in the same way that "Stanford network" or "Google alumni" are.

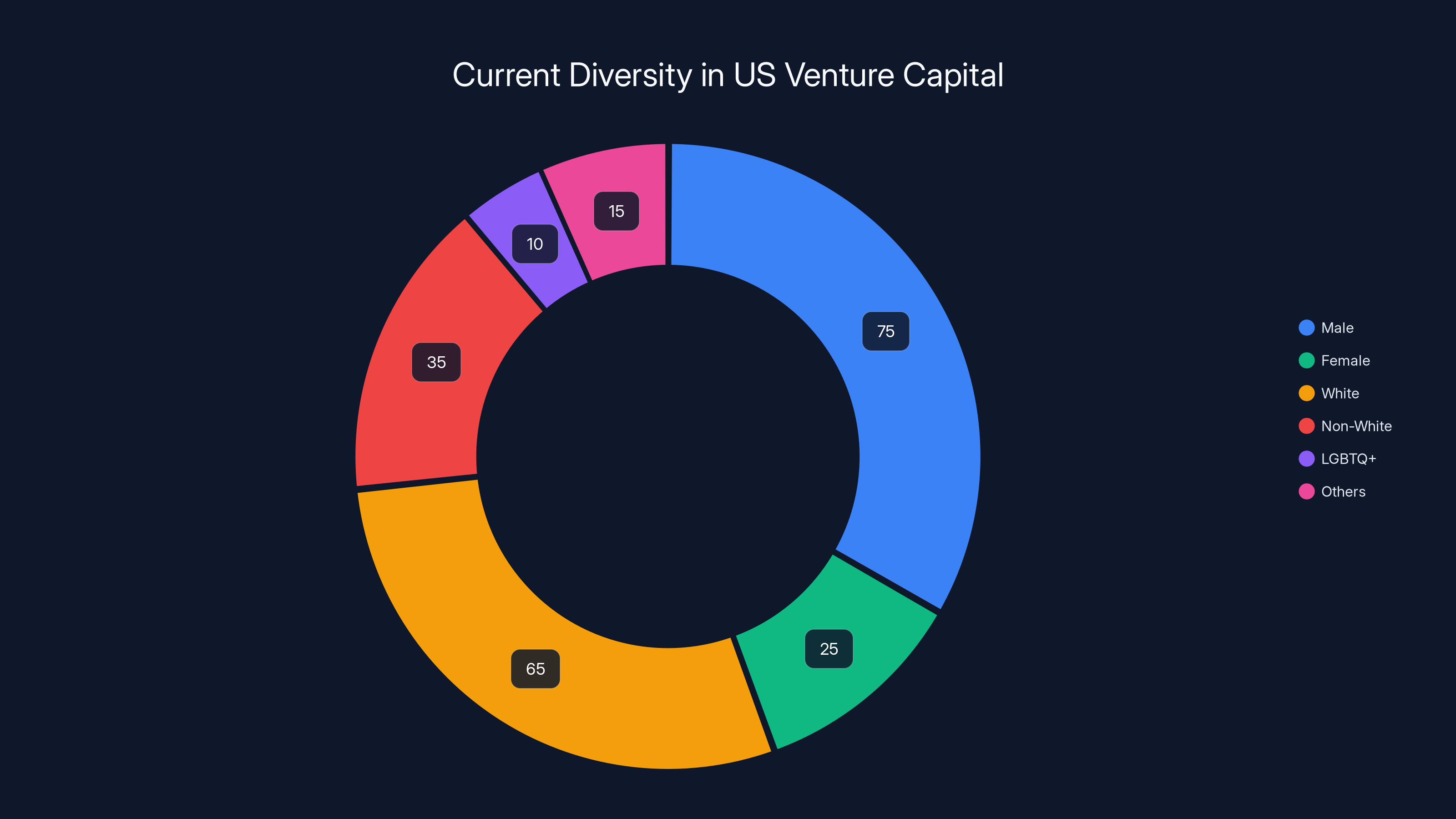

Current venture capital demographics show a significant male and white majority, with LGBTQ+ and other groups underrepresented. (Estimated data)

The Power Players: LGBTQ+ Leaders Reshaping Tech

To understand whether the "gay tech mafia" is real, you need to actually look at the people involved and what they've accomplished. The evidence doesn't support a coordinated conspiracy, but it does show something worth understanding: a genuinely significant group of LGBTQ+ leaders who've shaped the industry in profound ways.

Peter Thiel remains perhaps the most influential gay tech figure in recent history. His visibility in the venture capital world opened doors. As an openly gay founder and then investor, his success made space for others. The Thiel Fellowship, which gives young entrepreneurs $100,000 to skip college and start companies, has indeed produced prominent founders. People have speculated that Thiel uses the fellowship to advance gay entrepreneurs specifically. The evidence for this is thin. Most Thiel Fellows are straight. Thiel himself has said he cares about selecting the smartest people regardless of any other factor. But the rumor persists partly because Thiel has been publicly committed to libertarian politics and to the idea that the best people should rise to the top—a meritocratic vision that some people interpret as self-serving.

Tim Cook's influence at Apple represents something different. Cook didn't come out until after he was already the most powerful person at one of the most valuable companies in the world. His visibility as a gay CEO matters symbolically and practically. It signals that you can be openly gay and run major institutions. It also means that as one of the most powerful people in tech, Cook's presence alone shapes conversations about representation and leadership. Whether Cook has ever explicitly favored LGBTQ+ people in hiring or investment decisions is unclear. The visibility, though, matters regardless.

Sam Altman's rise as CEO of OpenAI during the AI explosion has been particularly visible in recent years. Altman's previous experience leading Y Combinator gave him deep connections throughout the startup world. His visibility as an openly gay CEO of the most prominent AI company created a backdrop where people started paying attention to who else was gay in tech leadership. The timing mattered—as AI began dominating conversations about the future of technology, people noticed that the guy running OpenAI was gay. Combined with other visible gay leaders, it created a gestalt shift in how people perceived the industry.

Keith Rabois represents a different model. As a venture capitalist who's been visible in the startup world for decades, Rabois has made a practice of mentoring younger founders and entrepreneurs. His openness about his sexuality was remarkable at a time when venture capital was even more closeted than it is now. Whether Rabois has preferentially invested in gay-led companies or hired gay partners is less documented. But his visibility as a successful gay investor changed what seemed possible in that world.

The visibility of openly gay leaders in tech has increased significantly from 2010 to 2025, with notable spikes around 2014 and 2020. (Estimated data)

Visibility Versus Reality: What the Data Shows

One of the most important distinctions in this conversation is between visibility and actual power. The "gay tech mafia" narrative relies on the visibility of certain individuals and then extrapolates from that visibility to suggest a broader coordinated influence. But visibility and power aren't the same thing.

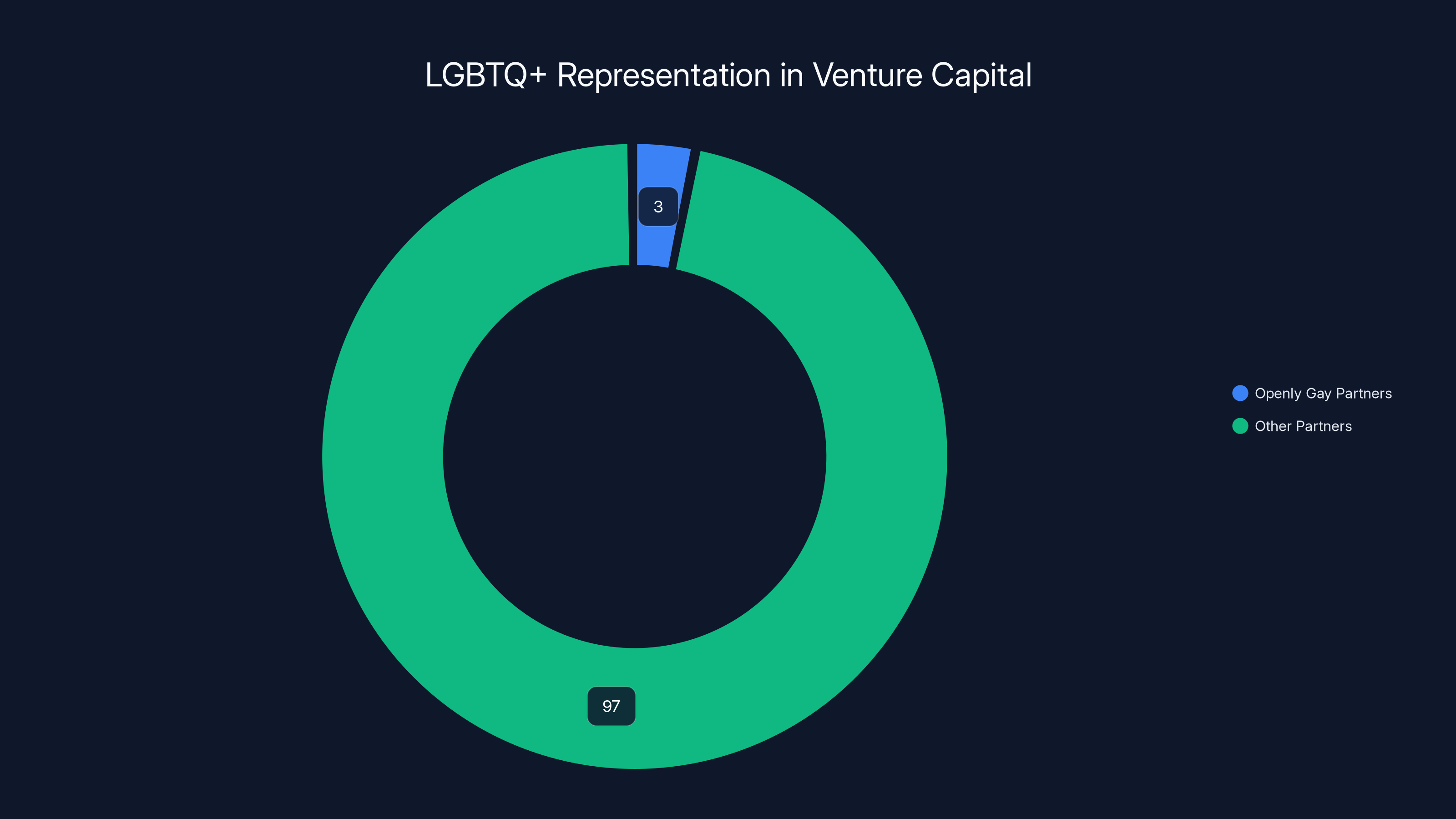

When you actually examine the numbers, LGBTQ+ representation in tech leadership remains limited. Yes, there are visible gay men in positions of influence. But the venture capital industry, which controls the distribution of capital and therefore shapes what gets built, remains overwhelmingly straight and male. Studies of venture capital firms show that partners who are openly gay represent a tiny fraction of the industry. The exact numbers vary by year, but estimates suggest somewhere between 1% and 5% of venture capital partners are openly gay, depending on the firm and the geography.

This matters because it means that even if every gay venture capitalist actively invested in other gay entrepreneurs, their actual share of capital deployment would still be minuscule compared to their straight counterparts. One person, no matter how influential, can only deploy so much capital and mentor so many founders. The idea that a small number of visible gay leaders control the industry requires believing in a kind of efficiency and coordination that doesn't match how venture capital actually works.

Moreover, venture capital has become increasingly professionalized and process-oriented. Modern VCs don't just make decisions based on personal relationships. They have partners, they have processes, they have LPs (limited partners) who are investing their money and want returns. They conduct due diligence. They make investment decisions based on market opportunity, founder capabilities, and business metrics. A venture capitalist can't just decide to fund another gay entrepreneur because of personal connection and have that work out in a professional context where results matter.

What the data does show is something more subtle. LGBTQ+ people in tech, like other minority groups, often build relationships with each other. There are informal networks. People introduce other people they know. Visibility creates opportunity—when someone notices there are gay leaders in tech, other LGBTQ+ people might feel more comfortable coming out, which creates more visibility, which normalizes the presence. This is real and worth acknowledging. It's not, however, the same as a coordinated mafia that "runs" Silicon Valley.

The Y Combinator Narrative and Sauna Rumors

One of the most specific claims in the "gay tech mafia" narrative concerns Y Combinator and its president, Garry Tan. Starting in late 2024, rumors circulated on social media about Tan hosting sauna and cold plunge sessions where Y Combinator founders would gather. The rumors evolved into suggestions that these were homoerotic gatherings, that Tan was "grooming" male entrepreneurs, that the whole thing was part of some gay power network.

The facts are considerably more mundane. Tan, who is himself straight, installed a sauna and cold plunge at his house and invited some founders over for dinner. After dinner, they asked to use the sauna. This happened. Tan has been open about this. The rumors that followed seem to have originated partly from people outside the Y Combinator ecosystem looking in and seeing what they wanted to see, and partly from what Tan himself describes as "rejects" of Y Combinator manufacturing a meme about the experience.

One particular photo—showing young male founders in swim trunks near a sauna—went viral on social media and sparked wild speculation. The image itself was completely innocent. But it created an opportunity for people to project their own assumptions about power, sexuality, and how tech leadership works onto an ordinary social gathering.

The Joschua Sutee incident, where a founder posted a photo of himself and cofounders apparently naked in bedsheets as part of what seemed to be a Y Combinator application, was similarly interpreted as evidence of something nefarious. In reality, it was a joke application designed to court attention on social media. The "grooming" narrative that emerged didn't match how Y Combinator actually works or what Tan's role actually involves.

What's interesting about this dynamic is what it reveals about how rumors function. When people want to believe something, they interpret ambiguous evidence as confirmation. A sauna becomes proof of a gay network. A naked photo joke becomes evidence of inappropriate recruitment practices. An ordinary dinner becomes a scene from a conspiracy thriller.

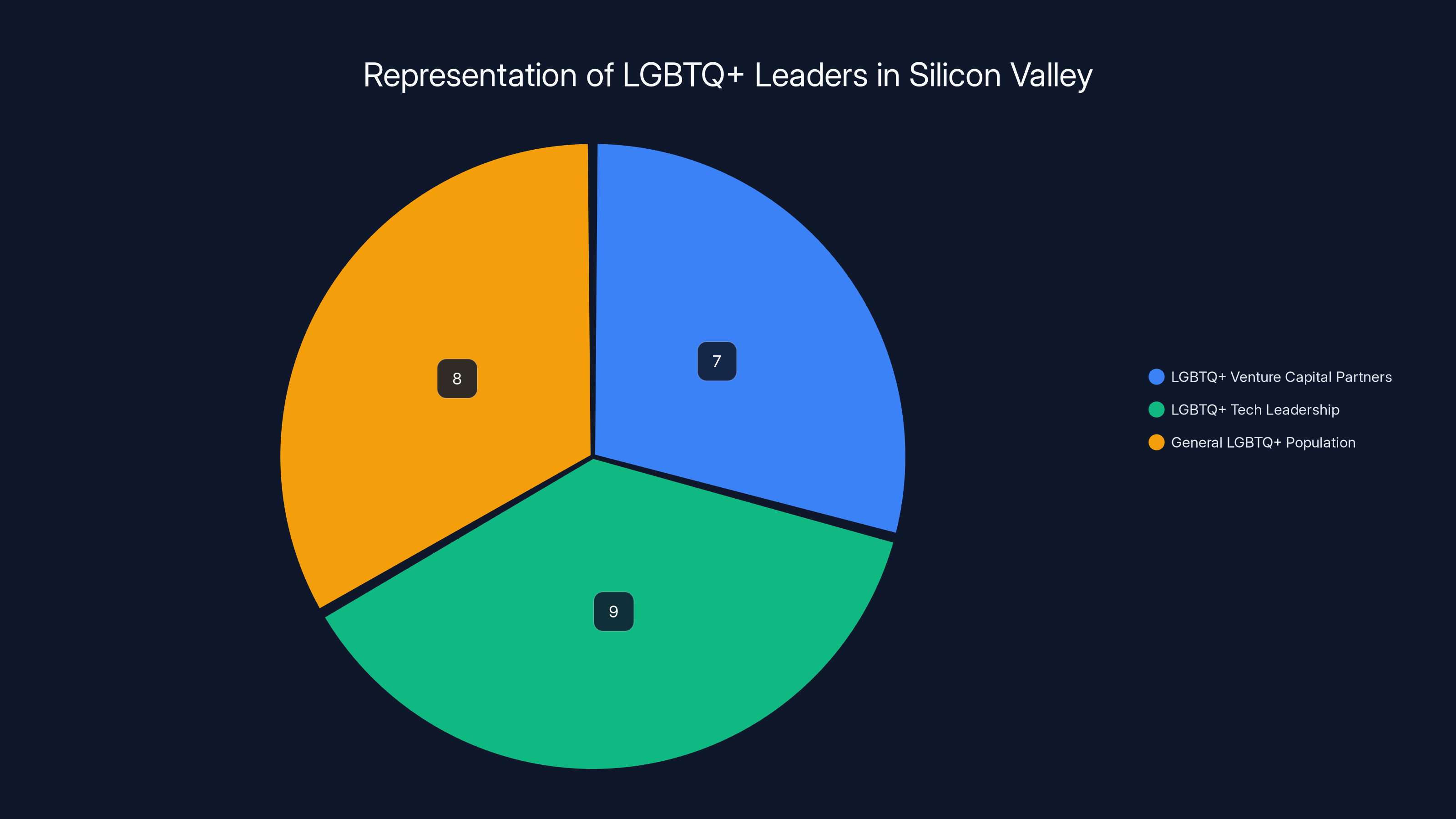

Estimated data shows that LGBTQ+ representation in venture capital and tech leadership is roughly on par with their representation in the general population.

Social Dynamics and the Geography of Power

To understand how the "gay tech mafia" rumor actually functions, you need to understand the social geography of Silicon Valley and how it's changed. The tech industry, unlike many others, operates through visibility and social media. Founders post about their lives. Investors share their thinking publicly. The whole ecosystem is somewhat performative—people signal their values, their networks, and their belonging through what they share.

When you look at who's visible on social media in the tech world, certain patterns emerge. There are groups of founders who seem to know each other, who appear in photos together, who collaborate and support each other's ventures. Some of these groups happen to be made up of gay men. This visibility creates a perception that there's an organized network.

But here's where the actual sociology gets interesting. Similar visible networks exist for straight founders and investors. Stanford alumni have networks. Google alums have networks. People from certain venture capital firms have networks. The fact that some networks happen to be gay networks doesn't make them fundamentally different from any other network based on shared experience or background.

What has changed is the nature of these networks. Thirty years ago, LGBTQ+ people in tech would often have hidden their sexuality. Networks existed, but they were necessarily underground or invisible. Over the past decade, as attitudes have shifted, these networks have become more visible. A gay founder can now openly attend events with other gay founders, can mention in interviews that they're gay, can build relationships openly. This visibility doesn't mean power has shifted—it means power has become more transparent.

The interesting question isn't whether gay people in tech know each other—of course they do. The question is whether that matters more than all the other forms of network and connection that also structure the industry. And the evidence suggests it doesn't.

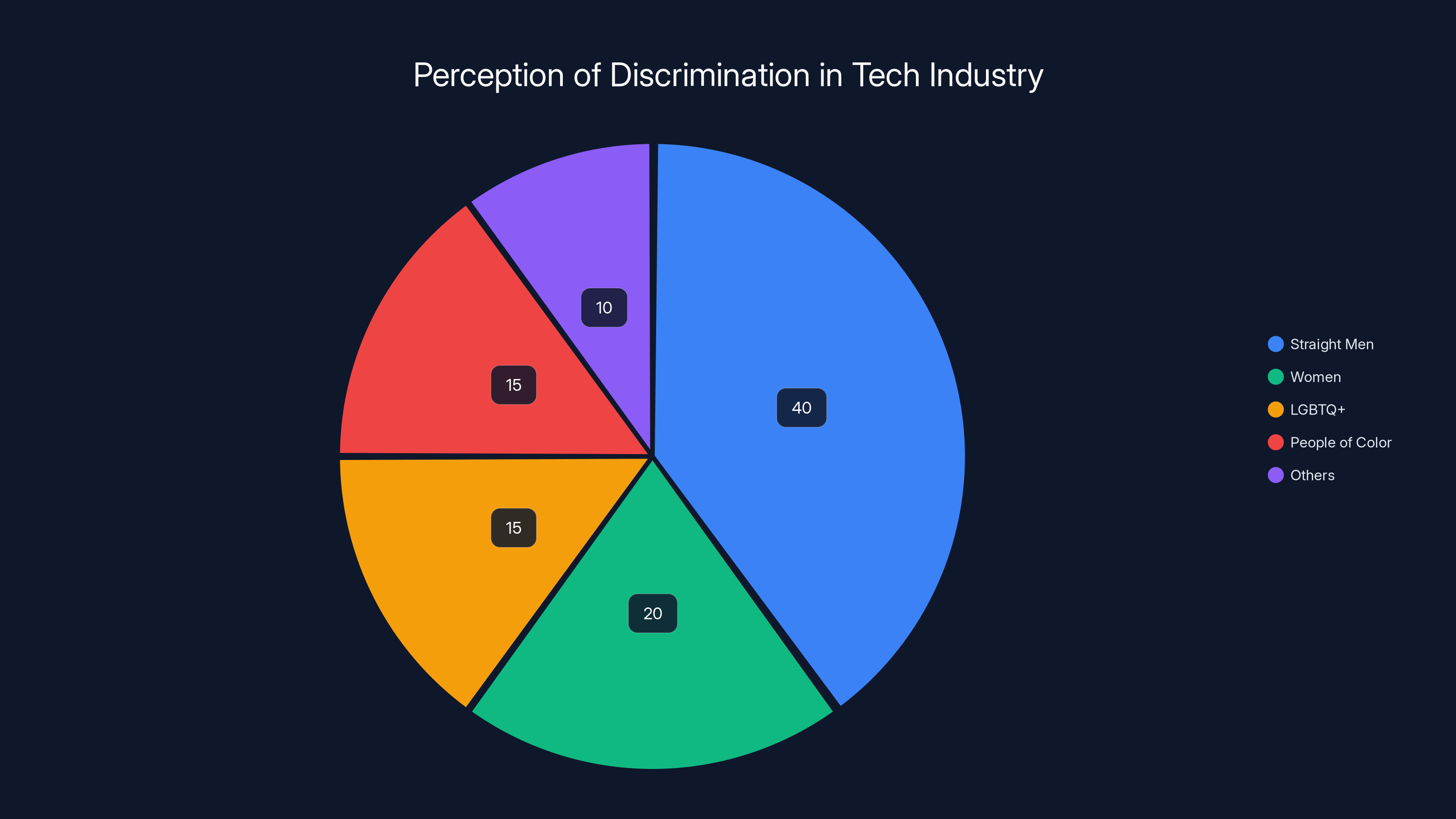

The Straight Backlash and Perception of Discrimination

Part of what's made the "gay tech mafia" narrative stick is that it's arrived alongside what some straight men in the industry perceive as discrimination against them. At venture capital parties and startup conferences, there have been explicit conversations among straight male investors about how hard it's become to succeed when they're competing against gay networks.

This perception deserves examination. There's a particular irony in straight men—a group that has historically dominated Silicon Valley completely—claiming they're being discriminated against. The venture capital industry, as recently as fifteen years ago, was almost exclusively straight male. Women, gay people, people of color, and other minorities were systematically excluded. The infrastructure of the industry—the norms, the social events, the informal networks—was built around straight male experience and preferences.

Over the past decade, that has shifted. Not completely. The industry is still majority straight and male. But there's more diversity. This creates a genuine discomfort for some people who benefited from the previous system. When there's less automatic preference for people like you, it can feel like discrimination. But it's actually just the baseline of fairness extending to other groups.

The "gay tech mafia" narrative functions as a way to reframe this as a problem that needs solving rather than as a correction of past exclusion. If you can convince yourself that there's an organized gay network preferentially funding gay entrepreneurs, then the playing field doesn't seem level. You're not losing ground because the industry is becoming more fair—you're losing ground because you're being discriminated against.

This matters because it shapes how people think about diversity and inclusion in tech. When straight men complain about gay networks, what they're sometimes really expressing is discomfort with the end of their own dominance. This isn't to say discrimination can't happen or networks don't exist. But it's to note that the perception of a "gay mafia" often functions as a narrative that obscures actual power dynamics.

Estimated data shows that openly gay partners make up only 3% of venture capital partners, highlighting limited LGBTQ+ representation in the industry.

The Role of Social Media in Amplifying Rumors

No discussion of the "gay tech mafia" narrative can ignore the role of social media in spreading and amplifying the rumor. Platforms like X (formerly Twitter) have created an environment where speculation can spread widely and quickly. A photo of young people near a sauna. A joke tweet about fractional vizier services for the gay elite. A comment about someone's sexuality. These get retweeted, quoted, discussed, and before you know it, there's a consensus narrative that didn't exist before.

This dynamic matters because it shows how rumors function in the age of digital media. Something doesn't have to be true to be widely believed if it gets amplified enough times and if it fits a narrative that people want to believe. The "gay tech mafia" story is compelling partly because it's exactly the kind of story that social media spreads. It's scandalous. It involves power and sex and insider knowledge. It appeals to people who feel excluded from power because it explains their exclusion as the result of conspiracy rather than as the result of their own limitations.

The algorithm itself plays a role here. Twitter's recommendation system tends to surface engaging content, and controversial narratives are engaging. Posts about the gay tech mafia, whether serious or joking, tend to get engagement. That engagement pushes them higher in people's feeds. Over time, what started as a joke or speculation becomes a widely shared reference point.

Moreover, the opacity of Twitter's algorithm and the difficulty of fact-checking in real-time create an environment where rumors can flourish. Someone posts a claim about the gay tech mafia. It sounds plausible. It aligns with people's suspicions. It gets retweeted. By the time you could verify it, thousands of people have already seen it and incorporated it into their understanding of how tech leadership works.

The Homophobic Subtext

Underneath many versions of the "gay tech mafia" narrative lies a particular kind of homophobia. Not the explicit kind that's easy to identify, but a more subtle version that works by treating gay people as somehow less authentic or legitimate in positions of power.

When straight men complain about gay networks, there's often an assumption embedded in the complaint: that gay people succeed because of their sexual orientation or their networks rather than because of genuine capability. This differs from how people talk about other networks. When someone gets a job through a Stanford connection, we call it networking. When someone gets a job through a gay connection, it becomes evidence of nepotism or conspiracy.

There's also a long history of using sexuality as a way to delegitimize people's accomplishments. If a gay person succeeds, the narrative becomes that they succeeded because they slept with someone or because they're part of a sexual network. The focus shifts from their actual capabilities and achievements to their sexuality and sexual practices. This is a classic way that homophobia works—it's not about saying gay people are bad, it's about suggesting that their successes aren't quite legitimate.

The fascination with the sexual dynamics of the "gay tech mafia" reflects this homophobic undertone. What people are often interested in isn't actually whether there are networks in tech (there obviously are), but in the sexual details of those networks. There's a voyeuristic element to the rumors. They function partly as a way to make gay people's sexual lives the center of attention.

This is worth noting because it shapes how we should think about the narrative. It's not just neutral speculation about how power networks form. It's partly an expression of anxiety about gay people in positions of authority, an anxiety that gets channeled into rumors about networks and conspiracies.

Estimated data shows that Tim Cook has the highest influence score among LGBTQ+ leaders in tech, highlighting his symbolic and practical impact.

Networks, Mentorship, and How Power Actually Distributes in Tech

To move past the "gay tech mafia" narrative, it's useful to actually understand how power distributes in Silicon Valley and tech more broadly. The answer is less conspiratorial than the rumors suggest, but also more interesting.

Power in tech comes from several sources. Capital, obviously—people with money can make things happen. Platform and audience—people with large followings can influence what happens. Expertise and reputation—people known for specific competencies attract opportunities. And networks—people connected to other influential people have better access and information.

All of these things are real, and all of them tend to concentrate. The rich get richer. People with platforms attract more opportunities. Experts become more expert through access to the best information and the best collaborators. And networks tend to perpetuate themselves—you introduce people you know to other people you know, creating denser and denser connections.

These dynamics work the same way regardless of the sexual orientation of the people involved. A straight venture capitalist with good connections will tend to invest in people in their network. A gay venture capitalist does the same thing. This isn't unique to any group. It's how networks function everywhere—in every industry, every country, every era.

The part that's specific to the tech industry is that so much of what you need to succeed is actually available to anyone with the right information and work ethic. You don't need connections to learn to code. You don't need an introduction to access most of the tools you need to build something. You can apply to Y Combinator without knowing anyone. You can pitch investors you've never met. The barriers to entry are lower than in most industries.

But once you're in the system, connections matter. Once you're trying to raise a large funding round, the people who know venture capitalists matter. Once you're trying to hire great people, your network matters. Once you're trying to navigate the complexities of going public or being acquired, having experienced people to talk to matters. This is where networks create genuine advantage.

When people talk about the "gay tech mafia," they're often pointing to this dynamic and suggesting it applies specifically to gay people. But the evidence doesn't really support this. The people who are succeeding in tech are mostly the people with the best ideas, the best execution, the best timing, and the best networks. Networks matter, but they're not the primary driver of success. And networks exist in every sector of the tech industry, not just among gay leaders.

The International Dimension

One thing that's sometimes overlooked in the "gay tech mafia" narrative is that the tech industry operates internationally, and the United States represents just one part of a global ecosystem. When you expand the aperture to include what's happening in Europe, Asia, and other regions, the idea of a concentrated gay network running tech becomes even less credible.

In many countries, LGBTQ+ people in positions of power remain far less visible than in the United States. In some countries, being openly gay in a position of authority is still genuinely risky or completely impossible. The idea that there's a global gay tech mafia coordinating across borders to shape the industry doesn't withstand scrutiny when you consider the actual legal and cultural constraints in different parts of the world.

Moreover, the tech industry's centers of power are distributed. Silicon Valley matters, but so do China's tech hubs, India's tech talent pipeline, Israel's innovation ecosystem, and European centers of technology development. No single group, gay or otherwise, coordinates across all these regions. The idea gets even less plausible when you consider the full global context.

What you do see internationally is that visibility of LGBTQ+ leadership varies dramatically by country. In some places, gay tech leaders are prominent and visible. In others, they remain largely closeted or rare. This variation itself is interesting and worth examining. But it doesn't support the narrative of a globally coordinated gay network. It supports a narrative where representation and visibility vary based on local legal, cultural, and political contexts.

Estimated data shows that while straight men perceive discrimination, other groups have historically faced more systemic exclusion. Estimated data.

Looking Forward: What Real Diversity in Tech Leadership Looks Like

As we move forward, the more useful question than "does the gay tech mafia exist" is: what would actually equitable representation in tech leadership look like, and what are the barriers to getting there?

Right now, the venture capital industry in the United States is approximately 70-80% male and 60-70% white, with significant regional variation. Within that, openly LGBTQ+ people remain a small percentage. Women, particularly women of color, remain significantly underrepresented. So do people with disabilities, people from non-traditional backgrounds, and people from underrepresented geographies.

If we wanted to move toward more diverse tech leadership, what would actually need to happen? Several things. First, more visibility from leaders in underrepresented groups. Not just visibility for its own sake, but genuine openness about their experiences and their paths to success. This is what figures like Tim Cook and Sam Altman have provided. When someone publicly succeeds as an openly gay leader, it changes what seems possible for other LGBTQ+ people.

Second, actual investment in mechanisms that create opportunity for people from underrepresented groups. This might mean accelerator programs specifically designed to support founders from particular backgrounds. It might mean venture capital firms making deliberate commitments to diversity in hiring and investment. It might mean building mentorship relationships across group lines. These things require intentional effort, not just goodwill.

Third, examination of the assumptions we make about who belongs in positions of power. When we assume that successful people must be part of some network or conspiracy, when we're more skeptical of people from underrepresented groups, when we hold different standards for different people—these things create barriers. Moving past them requires conscious effort.

The "gay tech mafia" narrative, ironically, might actually be an obstacle to real diversity in tech. By framing LGBTQ+ leadership as somehow improper or unearned, by suggesting it represents unfair advantage rather than overdue inclusion, the narrative works against the actual goal of a more diverse tech industry. Real progress on diversity means acknowledging that people from different backgrounds bring valuable perspectives and should have equitable access to opportunity.

The Business Case for Diverse Leadership

Beyond the ethical arguments for diverse tech leadership lies a compelling business case. There's substantial research showing that diverse teams and diverse leadership make better decisions, avoid groupthink, and identify opportunities that homogeneous teams miss.

When venture capital partners are mostly straight men from similar backgrounds, they tend to invest in founders who remind them of themselves. This creates an opportunity cost—good ideas from people outside their network don't get funded. Diverse teams of investors look for different things and fund different types of companies. They're more likely to identify market opportunities that homogeneous teams overlook. They're more likely to spot red flags that similar people might miss.

Similarly, when tech companies have leadership that reflects the diversity of their user base, they build better products. This isn't just theoretical. There's concrete evidence from tech companies that invested in diverse leadership and saw improvements in product quality, user satisfaction, and financial performance. When your team understands different perspectives and user needs, you build products that work for more people.

The business case is important because it moves the conversation beyond identity politics. You don't need to believe in diversity solely as a fairness issue (though that's compelling). You can believe in it because diverse teams and diverse leadership make better decisions and build better products. This is something the entire industry should care about.

In the context of the "gay tech mafia" narrative, the business case matters because it reframes the question. Instead of asking whether gay networks are running tech (a loaded question that presumes unfairness), we should ask: how do we build the most diverse possible leadership in the tech industry to maximize our ability to identify opportunities, build great products, and serve global markets? That's a question that benefits from LGBTQ+ leaders, women leaders, leaders from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds, and leaders from non-traditional career paths.

The Path Forward: Beyond Rumors to Reality

Where does this leave us? Not with a definitive answer about whether the "gay tech mafia" exists, because the question itself is flawed. What we actually have is this: a visible increase in LGBTQ+ people in positions of power in the tech industry over the past decade. This is real and worth acknowledging. We also have networks in the tech industry, which is true of all industries. Some of these networks happen to involve gay people, which is natural since gay people exist and tend to know other gay people. We also have the persistence of homophobia and the tendency for people to delegitimize the success of people from groups they're not part of.

The rumor of a "gay tech mafia" is partly a reflection of these realities, partly a projection of anxiety about changing power dynamics, and partly just the way humans create narratives to make sense of complex systems they don't fully understand.

Moving forward, the more productive conversation is about how to build more equitable and diverse tech leadership. This means creating clearer pathways for people from underrepresented groups to enter positions of power. It means being intentional about building networks that cross traditional boundaries. It means examining our own assumptions about who deserves success and who's allowed to be in charge.

It also means being skeptical of rumors that work to delegitimize the success of people from underrepresented groups. The "gay tech mafia" narrative, when taken seriously, works to suggest that gay people in tech succeeded through improper means rather than through actual capability. This is a form of discrimination, even if it's dressed up as observation or gossip.

The goal should be a tech industry where someone's sexual orientation is as irrelevant to their ability to succeed as it should be in any meritocratic system. We're not there yet. Building a system that actually operates on merit rather than on accident of birth, network, or identity requires ongoing effort. But it's the right goal, regardless of what rumors circulate about who's currently in power.

FAQ

What does "gay tech mafia" actually mean?

The term refers to an alleged coordinated network of gay men who supposedly control or heavily influence Silicon Valley's venture capital, startup ecosystem, and major tech companies. In reality, there's no evidence of a coordinated conspiracy, but there is increased visibility of openly gay leaders in tech positions, which the narrative sometimes conflates with actual power coordination. The term is more often used as a joking reference to the reality that multiple visible gay leaders exist in tech, rather than as a literal description of an organized group.

Is there actual discrimination against straight men in tech?

The available evidence suggests that straight men remain the dominant group in venture capital and tech leadership, receiving the vast majority of funding and partnership opportunities. What some straight men perceive as discrimination often reflects the end of overwhelming dominance rather than actual unfair treatment. That said, some individual instances of bias might occur in any direction. The broader pattern remains one of continued straight male dominance in positions of power and capital allocation, though this is slowly changing.

How visible are LGBTQ+ leaders in Silicon Valley?

LGBTQ+ leaders are more visible in tech now than at any previous point in history, with openly gay CEOs of major companies and prominent venture capitalists. However, visible individuals don't represent broad representation. Studies suggest that LGBTQ+ people represent roughly 5-10% of venture capital partners and a slightly higher percentage of tech company leadership, compared to estimates that 5-10% of the general population identifies as LGBTQ+, meaning there's rough parity in some areas despite the visibility gaps in previous decades.

Do networks in tech actually matter for success?

Yes, networks matter significantly in tech, as they do in most industries. Having connections to investors, mentors, and other founders can provide advantages in access to capital, advice, and opportunity. However, networks are not the only factor in tech success, and many successful founders started with no relevant networks. The internet and open-source software have democratized access to the tools needed to learn and build, reducing the traditional gatekeeping that networks once provided.

Why do rumors about the "gay tech mafia" persist despite lack of evidence?

Rumors persist because they tap into real anxieties about changing power dynamics, provide simple explanations for complex systems, and reflect deeper homophobia about gay people in positions of authority. The narrative also aligns with conspiracy thinking that appeals to people who feel excluded from power. Social media amplification ensures that once a narrative takes hold, it spreads regardless of factual basis.

What would actually equitable representation look like in tech leadership?

Equitable representation would mean leadership teams that reflect the diversity of the population and user base tech serves, with decision-making power distributed across people of different genders, races, sexual orientations, abilities, and backgrounds. This would require intentional efforts to remove barriers, build diverse networks, and examine assumptions about who belongs in positions of power. We're still quite far from this goal, with most tech leadership remaining predominantly male, straight, and white.

The Bottom Line

The "gay tech mafia" is a useful myth to examine because it reveals how we think about power, networks, and identity in tech. The rumor isn't entirely false—there are visible gay leaders in tech, and they do know each other—but it's not true in the way conspiracy thinking suggests. There's no coordinated cabal running Silicon Valley. What there is, instead, is a gradually more diverse set of people in positions of power, which is producing real changes in how the industry operates.

The more important conversation isn't whether a gay network controls tech, but how to build a tech industry that's actually meritocratic and accessible to everyone. This means creating real opportunities for people from underrepresented groups, removing barriers to entry and advancement, and building networks that cross traditional boundaries.

It also means being skeptical of narratives that work to delegitimize the success of people who don't look like the traditional tech leader. When we suggest that someone succeeded because of their identity or their network rather than their actual capabilities, we're engaging in a form of discrimination. This applies equally whether we're talking about gay people, women, people of color, or any other group.

The best outcome would be a tech industry where a person's sexual orientation is as irrelevant as it should be—where the question of whether someone is gay or straight matters no more than the color of their eyes. We're not there yet. Building toward that future requires moving past rumors about mafias and getting serious about actual diversity and equity. That's the real challenge, and it's worth far more attention than speculation about what gay leaders might be doing behind closed doors.

Key Takeaways

- The 'gay tech mafia' is more rumor and homophobic speculation than coordinated reality, though LGBTQ+ representation in tech leadership has genuinely increased over the past decade

- While visible gay leaders exist in tech, they represent a small percentage of venture capital and leadership positions, which remain dominated by straight men receiving 75-80% of capital

- Networks function in tech as they do in all industries, concentrating opportunity among connected individuals regardless of sexual orientation, but the evidence doesn't support organized coordination by gay leaders

- The narrative often functions as a way for straight men to reframe losing ground to more diverse competition as unfair discrimination rather than overdue inclusion

- Building truly equitable tech leadership requires intentional efforts to remove barriers, examine assumptions, and create diverse networks—not rumors about conspiracies

Related Articles

- Why Loyalty Is Dead in Silicon Valley's AI Wars [2025]

- India's $200B AI Infrastructure Push: What's Really Happening [2025]

- xAI's Mass Exodus: What Musk's Spin Can't Hide [2025]

- Under Salt Marsh Episode 4: Character Power Dynamics Shift [2025]

- OpenAI's Greg Brockman's $25M Trump Donation: AI Politics [2025]

- xAI Engineer Exodus: Inside the Mass Departures Shaking Musk's AI Company [2025]