Why Loyalty Is Dead in Silicon Valley's AI Wars

Think back to the Google founders. Larry Page and Sergey Brin built the company from a Stanford dorm room and stayed committed through explosive growth. They saw their mission through for decades. That story feels quaint now.

Today's reality in Silicon Valley is messier, faster, and far more transactional. The people building the next generation of AI don't stick around long enough to see their companies become household names. Instead, they're jumping ship for bigger labs, better opportunities, or yes, life-changing money.

We're watching the collapse of founder loyalty in real time. And it's reshaping everything about how startups work, how capital flows, and who actually controls the future of artificial intelligence.

This isn't just a hiring problem. It's a fundamental shift in how tech operates as an industry.

TL; DR

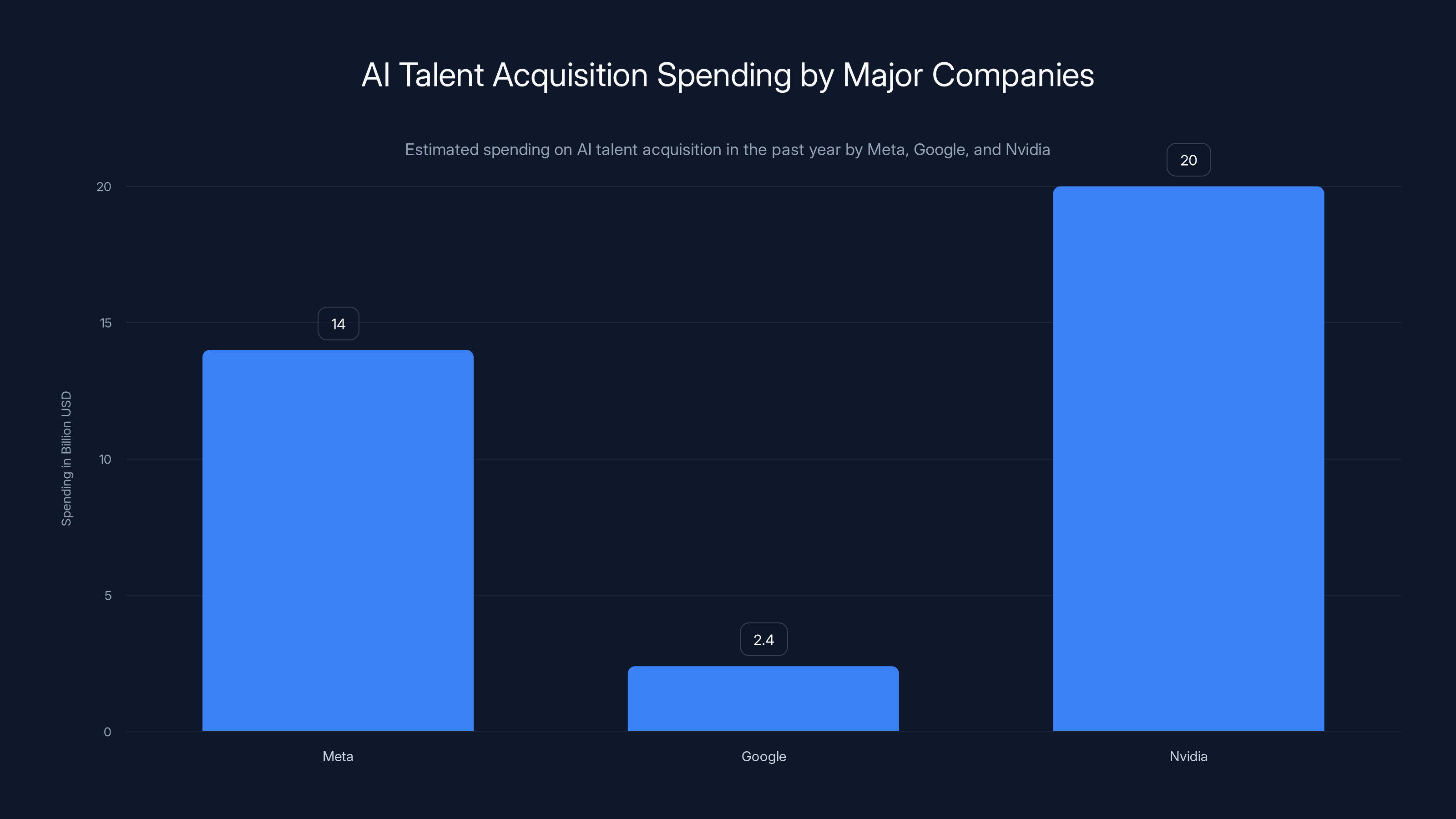

- The numbers tell the story: Meta dropped 2.4 billion and Nvidia wagered $20 billion in the past year alone on research teams, not just tech. According to The New York Times, these investments are reshaping the competitive landscape.

- Researcher musical chairs is the new normal: OpenAI, Anthropic, and other frontier labs are constantly poaching talent from each other in an endless cycle of departures and rehiring. Fortune highlights the ongoing talent shuffle among these labs.

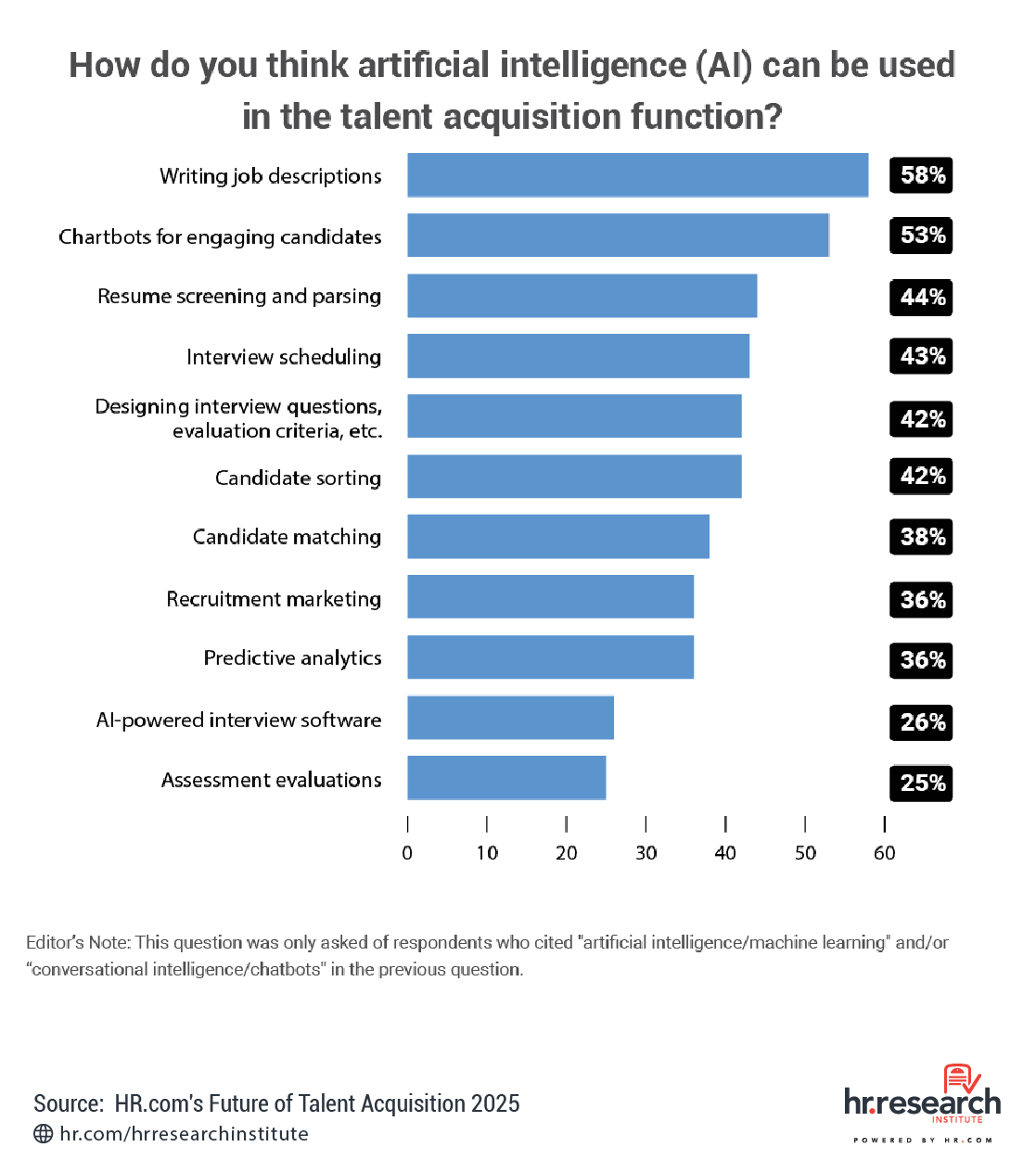

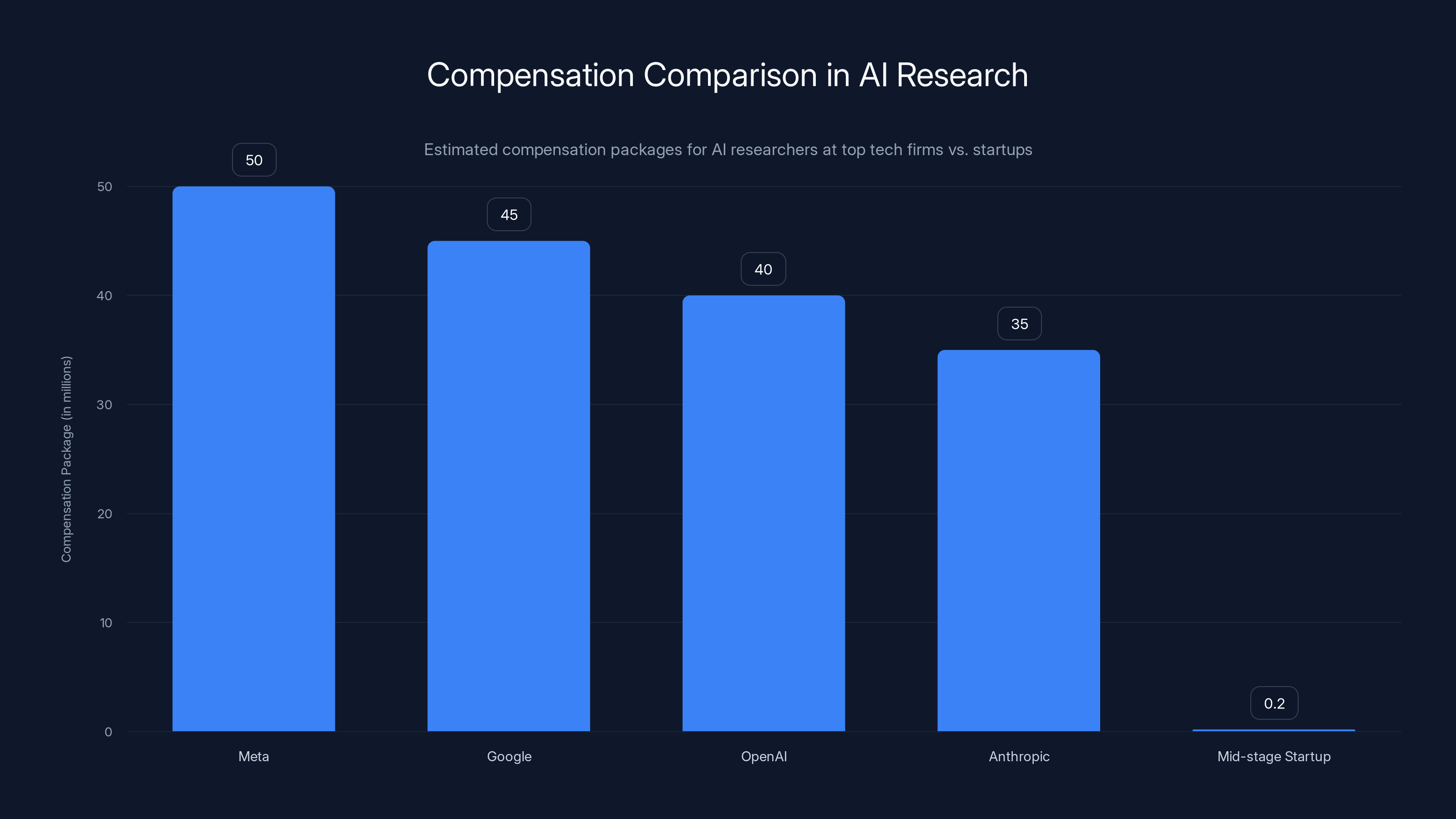

- Money is part of it, but not the whole story: Top researchers are getting compensation packages in the tens or hundreds of millions, but they're also chasing rapid innovation and impact. Reuters reports on the high stakes and high rewards in AI talent acquisition.

- Structural shifts changed the game: Stock options vesting timelines, the tech industry's damaged reputation, and accelerated AI development cycles all killed long-term commitment. The New Indian Express discusses how these changes are impacting the industry.

- Investors are scrambling to protect themselves: New deal structures now include protective provisions and founder compatibility checks that didn't exist before. SaaStr explains how investors are adapting to the new reality.

- Bottom line: The startup ecosystem is being "unbundled" in real time, with early-stage companies now being valued partly as acquisition targets for their talent pools.

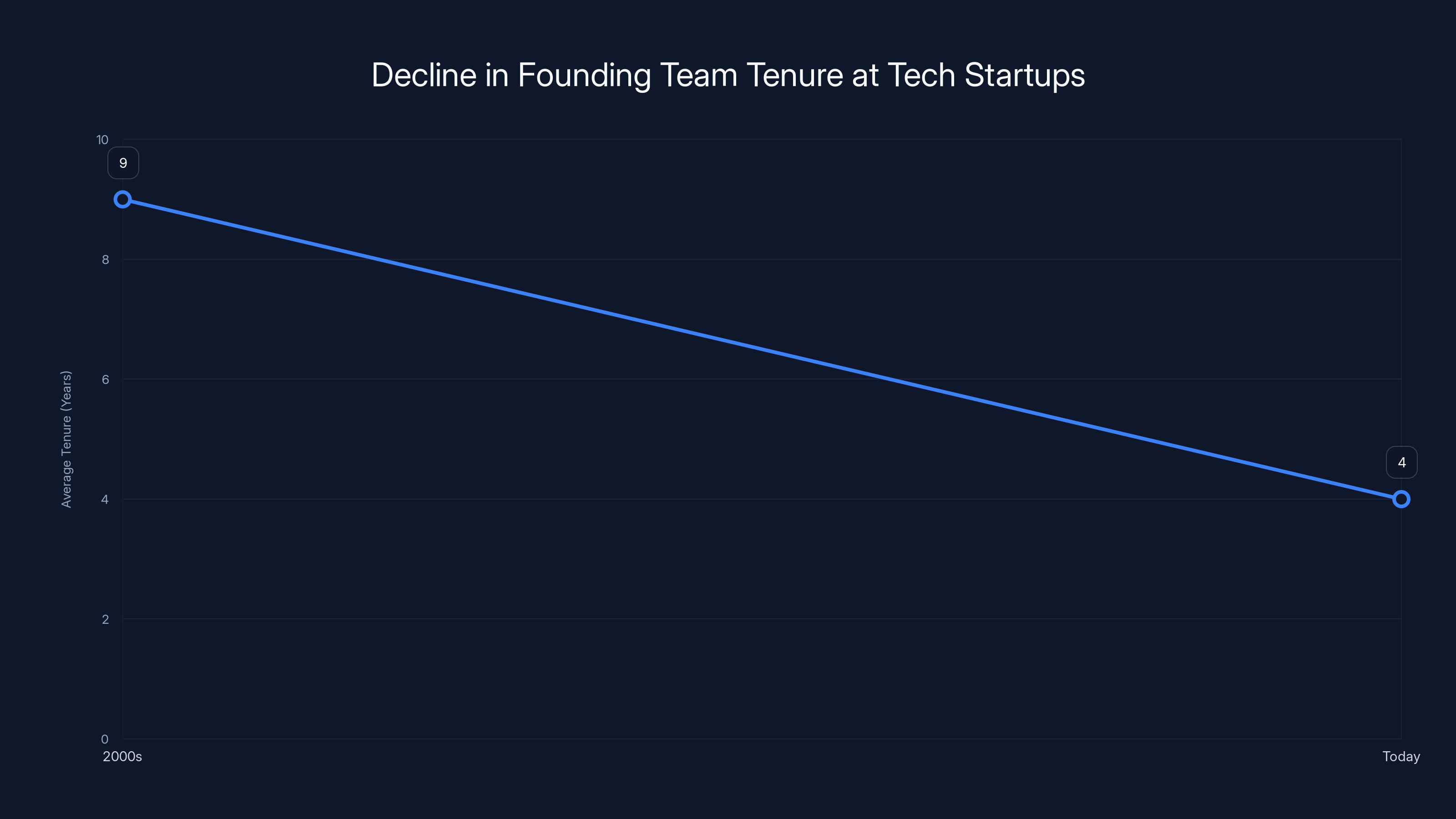

The average tenure of founding teams at tech startups has decreased significantly from 8-10 years in the 2000s to 3-5 years today, indicating a shift towards shorter-term commitments.

The Great Unbundling: How AI Startups Became Talent Farms

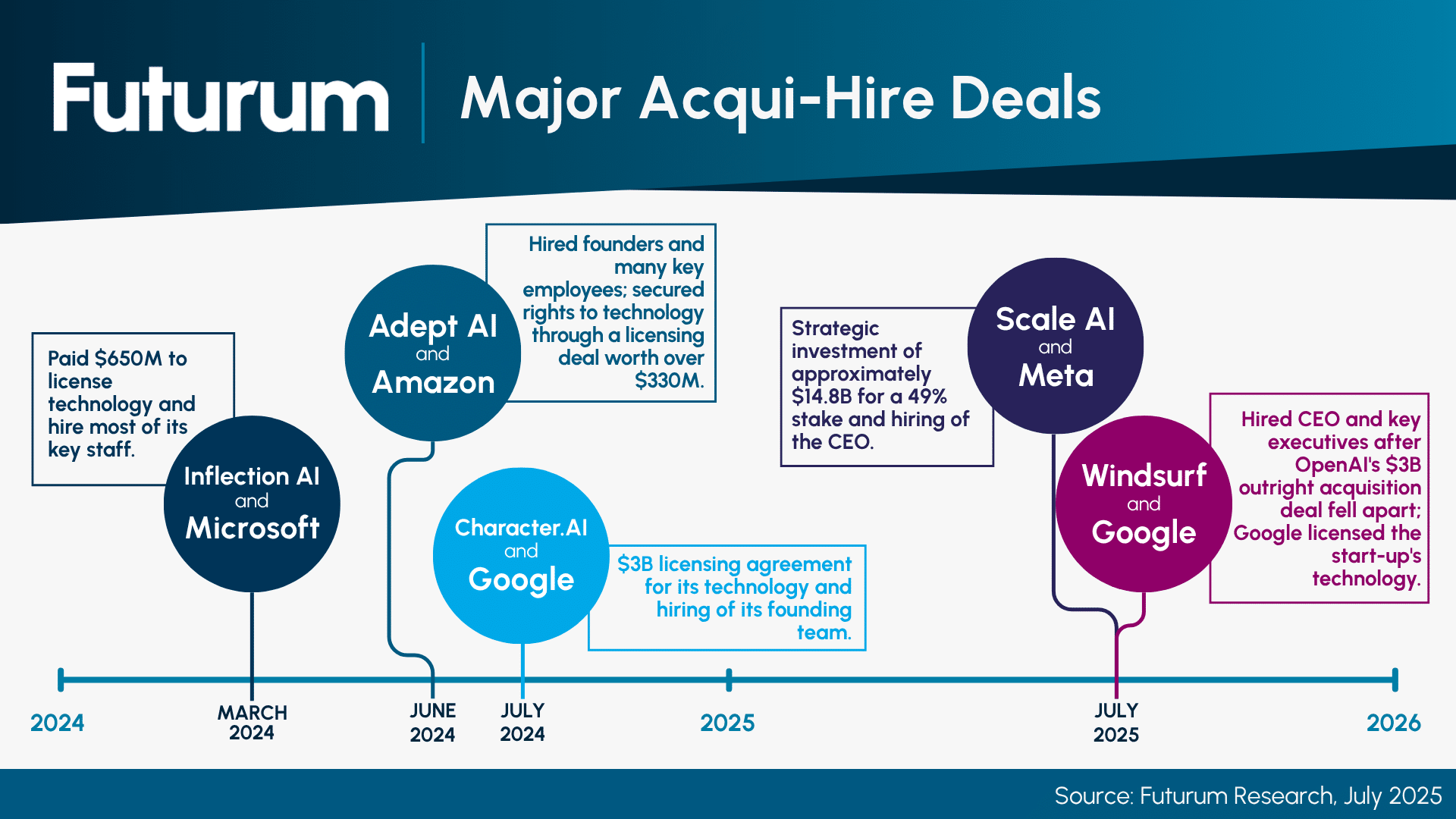

Just over the past year, we've watched three massive AI talent acquisitions reshape the industry landscape. These weren't traditional acquisitions where you buy a company to use its product. These were acqui-hires in the truest sense—buying the startup primarily to acquire its founders, researchers, and teams.

Meta's

These aren't exceptions. They're becoming the standard playbook.

The term "acqui-hire" used to describe acquiring a small team of five to ten people. Now it describes buying companies with 50+ researchers and dozens of engineers. The scale has exploded. The mission creep is real.

What's happening is what investors are starting to call the "great unbundling" of the tech startup. For decades, the implicit deal was simple: you start a company, you bring on talented early employees, and you all work together toward a liquidity event or sustained growth. Everyone sacrifices, everyone benefits. Loyalty meant something.

Today? The deal has inverted. Startups are being explicitly valued as containers for talent that can be extracted, reassigned, or redeployed the moment a bigger player makes an offer. Investors now structure deals expecting that outcome. Founders are starting their companies knowing they might not survive intact.

Dave Munichiello, an investor at GV (Google Ventures), told me directly: "You invest in a startup knowing it could be broken up."

That's not pessimism. That's the new baseline assumption.

The Talent Wars Heat Up: OpenAI, Anthropic, and the Researcher Shuffle

The churn at frontier AI labs has become almost absurd.

Three weeks ago, OpenAI announced it was rehiring several researchers who had departed less than two years earlier to join Mira Murati's startup, Thinking Machines Lab. Meanwhile, Anthropic—itself founded by former OpenAI researchers who left in protest of the company's safety practices—has been actively poaching talent back from OpenAI. And OpenAI just hired a former Anthropic safety researcher to be its "head of preparedness." Fortune covers these dynamic shifts.

It's musical chairs at the highest level of AI development.

This creates a bizarre dynamic. Researchers leave OpenAI for the independence and mission alignment of a smaller startup. Then, they get lured back with better compensation, more resources, or a sense that the frontier is moving back to the larger labs. It's not a stable system. It's not even close to stable.

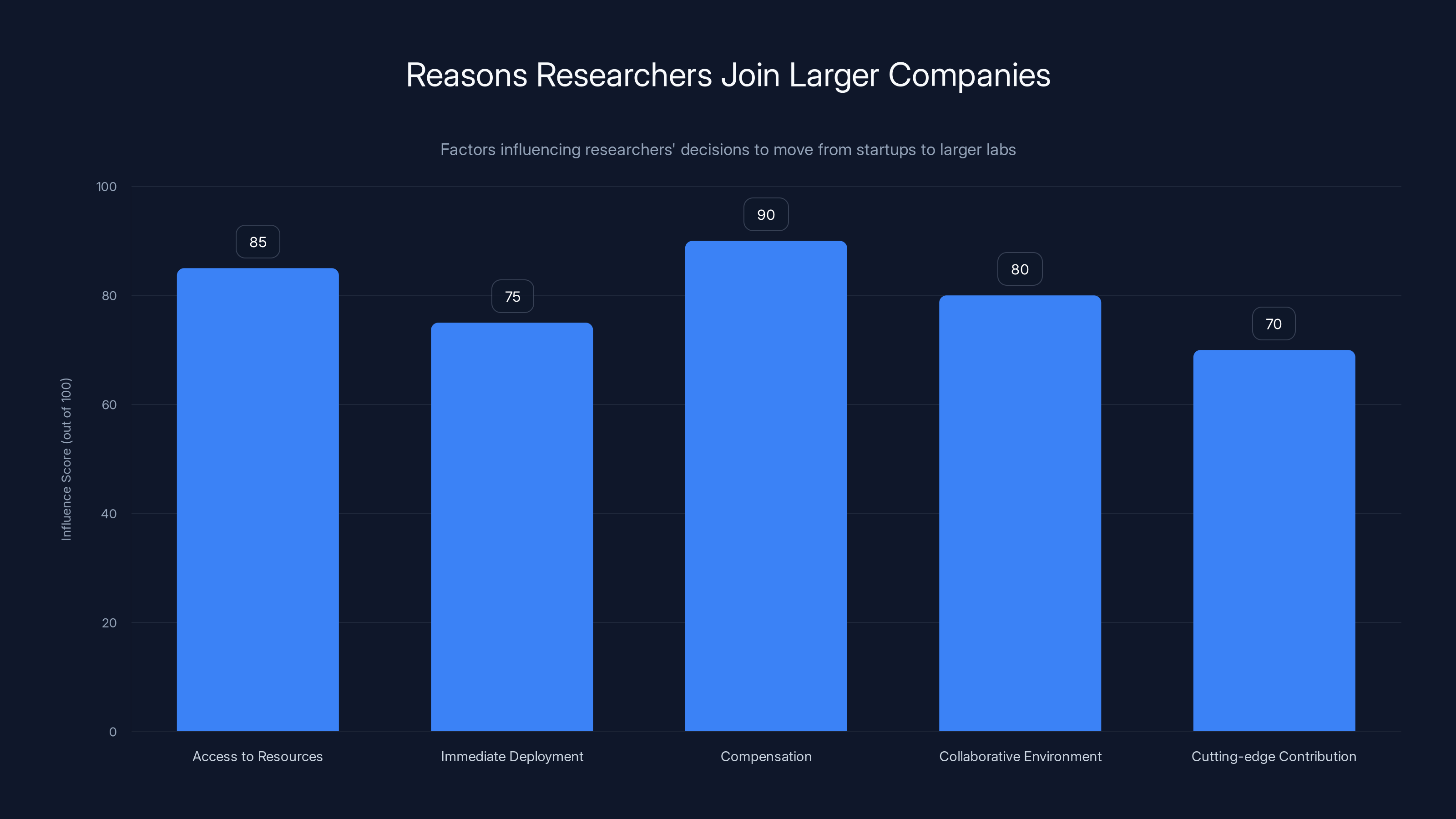

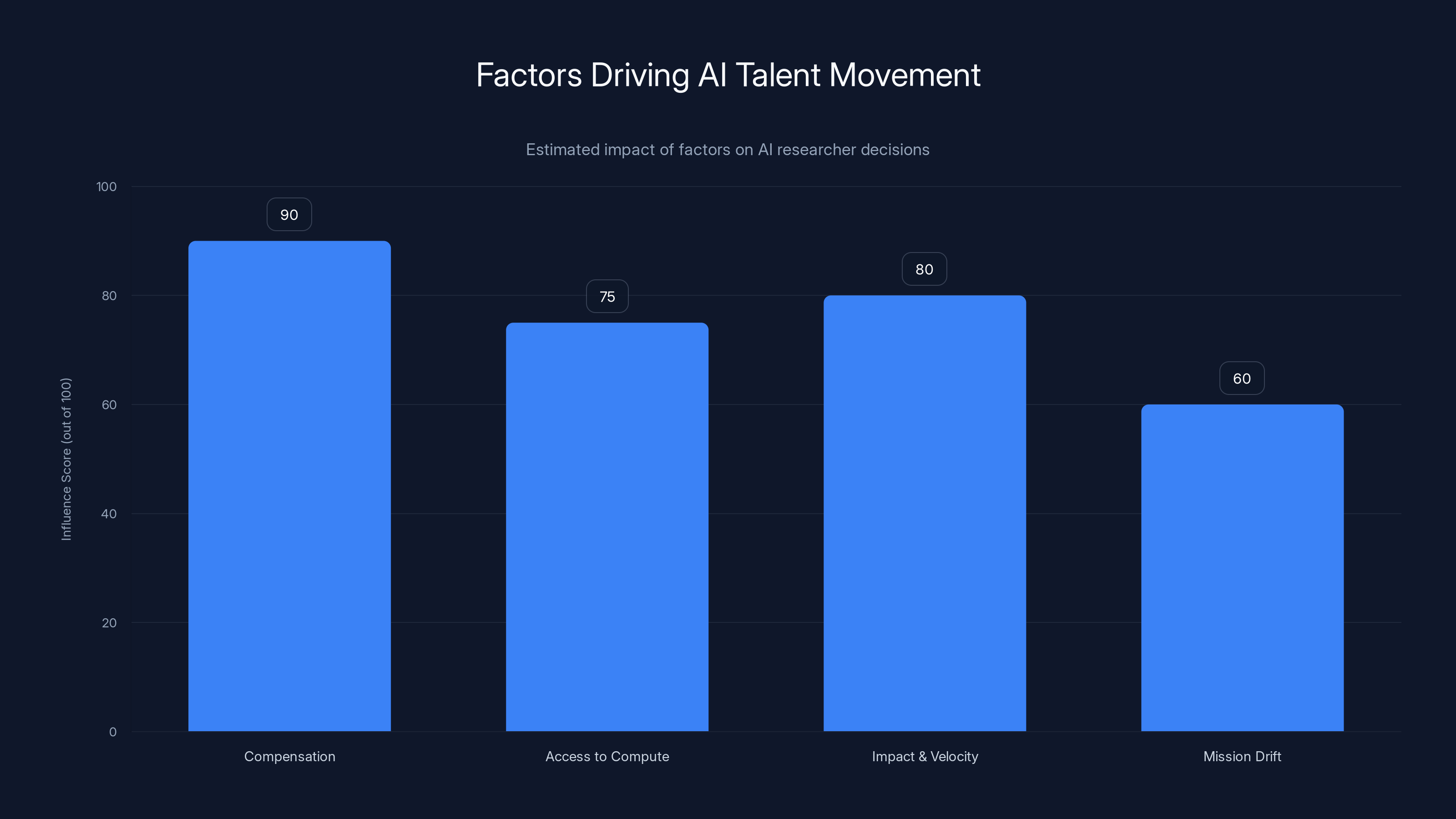

What's driving this volatility? Several factors converge:

Money that's hard to refuse: Meta was reportedly offering top AI researchers compensation packages in the tens or hundreds of millions of dollars. These aren't just salary bumps. They're generational wealth. For someone making

Access to compute: Smaller startups, no matter how well-funded, can't compete with the raw computing power that labs at Meta, Google, or Anthropic can offer. If you're developing frontier AI models, the difference between having 100,000 GPUs and 10,000 GPUs is massive. It directly impacts speed and capability.

Impact and velocity: Working at a frontier lab means your research affects models used by hundreds of millions of people. You see your work deployed at scale within months, not years. That's intoxicating for researchers.

Mission drift and disillusionment: Startups founded with grand missions often pivot when they realize adoption is slow or capital demands shift strategy. Researchers who joined for "safety" end up working on "scaling." The gap between promise and reality widens fast.

The result? No one stays anywhere long enough to build institutional knowledge anymore. Continuity is treated as a liability, not an asset.

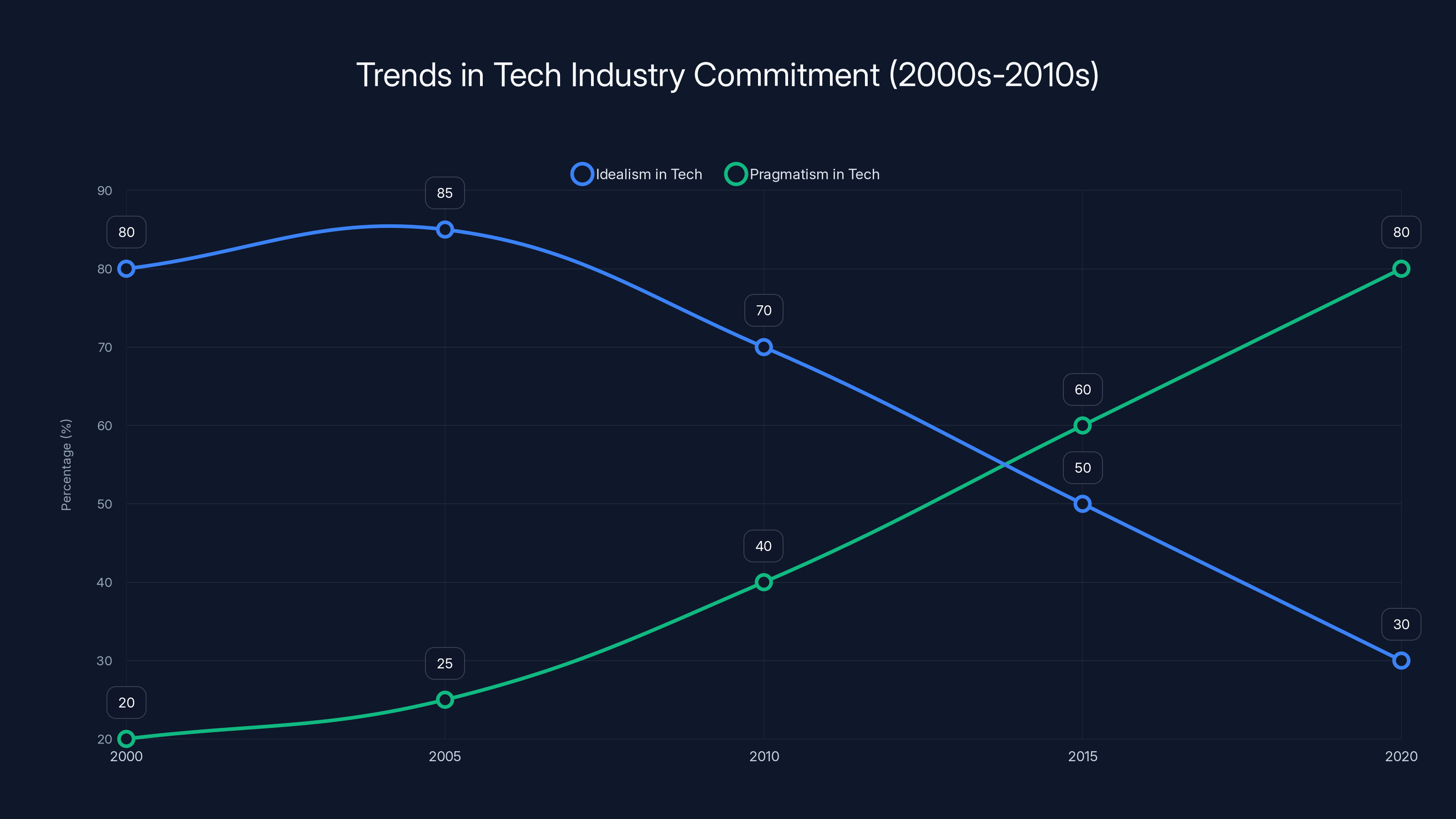

Over the past two decades, idealism in the tech industry has declined, while pragmatism has increased, reflecting a shift in employee and founder motivations. (Estimated data)

Why the 2000s-2010s Model Collapsed

Let's be honest about what changed. For a solid decade, the tech industry had something that felt like idealism baked into its DNA.

Early Google employees believed they were organizing the world's information. Facebook's first team thought they were connecting humanity. Airbnb's founding crew wanted to democratize travel. These weren't just marketing slogans. Many of these founders and early employees actually believed this stuff.

They stayed because of it.

You got the stock options vesting cliff—typically four years of commitment. But there was also psychological commitment. The sense that you were building something that mattered, that your tenure could be measured in decades, that the mission justified the sacrifice.

Then reality caught up.

As Sayash Kapoor, a computer science researcher at Princeton University and senior fellow at Mozilla, put it: "People understand the limitations of the institutions they're working in, and founders are more pragmatic."

The tech industry's halo dimmed. Facebook became Meta, and people learned about how their data was being weaponized. Amazon's growth became synonymous with worker exploitation. Elon Musk's antics shattered the image of "visionary founder." Google itself, once the idealistic upstart, became the sclerotic surveillance advertising empire it had feared becoming.

Meanwhile, the stock option contract—that four-year golden handcuff—started looking like an impediment rather than an incentive. Why commit to four years when you can vest your options at one company, jump to another at an even higher level, and do it again at a third company? The math works out better for personal wealth accumulation.

For researchers and technical founders, the calculation became even sharper. Kapoor notes that over the past five years, he's observed more PhD researchers leaving their doctoral programs to take industry jobs. The opportunity cost of staying in academia or at one company is massive when the field is moving this fast.

"There are higher opportunity costs associated with staying in one place at a time when AI innovation is rapidly accelerating," Kapoor explained.

One year at an AI startup, he argues, is equivalent to five years at a traditional tech company in a different era. You ship products used by millions. You solve novel technical problems. You learn at a compressed rate. Then you leave, taking that accelerated knowledge with you.

The Money Motive: Generational Wealth as a Tool

Let's not dance around it: money is the primary driver for many of these moves, especially the acqui-hire bonanzas.

Meta's reported compensation packages for AI researchers weren't just "competitive salary plus equity." They were eight-figure offers for individual researchers. A director of ML research at a startup might have a net worth of

When Google acquired Windsurf, the cofounders didn't just get their existing equity multiplied. They likely got massive signing bonuses, new equity grants, and additional retention bonuses spread over four years. Same with Anthropic and OpenAI researchers who've moved to bigger labs.

For a single researcher with a family, a mortgage, and ambitions, that's generational wealth. It means your kids go to elite schools without loans. It means you never worry about healthcare costs. It means you can retire at 35 if you want to.

Compare that to the four-year vesting schedule of your startup equity, which might vest as the company scales but before any actual exit happens. You're looking at five to ten years of waiting for potential liquidity events. With a $50 million upfront offer, you get certainty now.

But here's the catch: this level of compensation only works for the frontier. You need to be working on the most cutting-edge problems at places with massive capital backing to command these wages. A researcher at a mid-stage startup making $200K/year will never see that kind of offer.

This creates a two-tier market: the super-elite AI researchers clustered at Meta, Google, OpenAI, Anthropic, and a few others, hoovering up capital and opportunity. Everyone else, scrambling for drops of funding and second-tier talent.

It's not just unfair. It's structurally unstable.

How Founders Are Becoming Pragmatists Over Idealists

The founder mindset has shifted dramatically.

In the 1980s and 1990s, when Lew Tucker joined Thinking Machines Corporation in 1986, there was no job board. No LinkedIn. No headhunter culture. You "talked your way in" to a company and then you stayed. Fifty people became 500. Everyone rode it out. Very few people left.

When the company eventually went under and got acquired by Sun Microsystems in 1996, there wasn't a sense of betrayal. It was just how things ended. You moved to the acquiring company or found something new. But the whole tenure was measured in a single company's arc.

Fast forward to 2000-2010. Google's founders stayed through the IPO and beyond. Same with Facebook, Yahoo, Amazon. There were bragging rights attached to turning down acquisition offers from big, "bloated" tech companies. Staying committed to the startup mission was almost a badge of honor.

Now? Founders are doing the math differently.

A founder in 2025 understands that their startup might be acquiring-hired within three to five years. They're no longer building with the assumption they'll be there for ten years. They're building with the assumption that some part of their team will be scooped up by a larger lab or competitor.

This changes what startups optimize for. Instead of long-term sustainability, they optimize for rapid research output and team visibility. Publish papers. Speak at conferences. Build press around your team. Get noticed by the acquirers. Move fast, build reputation, get acquired.

It's not cynicism exactly. It's just pragmatism. These founders have watched a decade of acquisitions and realized the game has changed. The fastest way to capital, to scale, to resources isn't always to bootstrap and grow independently. Sometimes it's to build something compelling enough that Meta, Google, or OpenAI wants to buy your talent.

The founders of Windsurf might have calculated their impact could be larger at Google with its vast resources than remaining independent. That wasn't a failure of commitment. That was a success of pragmatism.

Top tech firms offer AI researchers compensation packages worth tens of millions, creating a two-tier market. Estimated data.

The Academic Brain Drain: Universities Can't Compete

The loyalty collapse isn't confined to startups. It's hitting academia hard.

Capoor observes a clear trend: more PhD researchers are leaving their doctoral programs mid-way through to take industry jobs. In computer science specifically, this is creating a brain drain that universities can't afford.

Why would someone finish a five-year PhD when they could join an AI startup with $10 million in funding, work on state-of-the-art models, and potentially join in an acqui-hire deal three years in? The PhD provides credentials and depth. The startup provides impact, compensation, and acceleration.

For someone in their mid-twenties, the choice is obvious.

Universities have tried to compete by offering better packages, but there's a structural limit. A professor salary tops out around

The result is that traditional academic computer science is losing its best people to industry. This has downstream implications: fewer professors training the next generation of researchers, fewer people building the theoretical foundations of AI, fewer voices asking "should we be doing this?" and more voices asking "how do we build this faster?"

It's creating a skew toward applied research over foundational research. Toward speed over safety. Toward industry incentives over academic ones.

Investor Panic: How Deal Structures Are Changing

Investors watched this unfold and started getting nervous.

You invest in an AI startup with a killer founding team. You think you're betting on that team's ability to execute. Then, eighteen months in, your Series B closes, and Meta offers the CEO a $100 million deal to come work on LLMs. The entire thesis breaks. The team fragments. Your investment case collapses.

Investors started adapting deals to protect against this.

Max Gazor, founder of Striker Venture Partners, described new diligence processes: "We're vetting founding teams for chemistry and cohesion more than ever."

That's code for: "We're trying to predict which teams will hold together and which will fly apart the first time someone gets a big offer."

New term sheets also include protective provisions that require board consent for material IP licensing or similar scenarios. Translated: if a founder or researcher wants to take key IP to a new company or gets recruited away with critical tech, there are contractual obstacles.

Some investors are even including clawback provisions or acceleration clauses that punish departures. Others are structuring equity with staggered vesting specifically to keep founders locked in longer.

Gazor also noted that many of the biggest recent acqui-hire deals involved startups founded long before the generative AI boom. Scale AI started in 2016. Windsurf wasn't a brand-new startup. These were companies with established track records that happened to be positioned perfectly for the AI wave.

Now, these potential outcomes are "constructively managed" in early term sheets. Investors assume the startup might be broken up. They structure deals accordingly. They build in provisions that give them optionality if that happens.

It's a fundamental shift in how venture capital thinks about its bets.

The Speed Advantage: One Year Feels Like Five

Here's something that doesn't get enough attention: the subjective experience of time in AI startups is compressed.

Steven Levy, who's been reporting on Silicon Valley for decades, nailed this: "Working for an AI startup for one year is equivalent to working for a startup for five years in a different era of tech."

Why? Because the iteration speed, the feedback loops, and the scale of impact are all accelerated.

In a traditional SaaS startup, you might spend six months building a feature, three months getting customers to test it, two months iterating based on feedback. A full cycle might take a year.

In an AI startup, you can launch a new model, get immediate feedback from millions of users (via API or product interface), and iterate daily. You can ship something that didn't exist a week ago to hundreds of thousands of people by Tuesday.

The researchers who build this stuff feel like they're operating at 5x speed compared to anywhere else. Every week brings new breakthroughs, new scaling results, new capabilities. You solve problems that felt impossible a month ago. You learn at a pace that's almost disorienting.

After one year at that pace, you feel like you've done five years of normal work. You've mastered techniques, solved hard problems, shipped at scale, seen your work deployed to millions.

At that point, moving to the next challenge feels natural. You're not abandoning something unfinished. You're graduating from a compressed educational program. The psychological experience of loyalty is different when time moves differently.

This is partly why researchers are comfortable jumping between companies. They don't feel like they're leaving before the job is done. They feel like they've done the job, learned what they came to learn, and are ready for the next thing.

Researchers are primarily driven by compensation and access to resources when moving to larger labs. Estimated data based on common motivations.

The Cultural Shift: From Idealism to Impact Maximization

There's a subtle cultural shift happening that goes deeper than just money.

In the 2010s, tech careers were framed around company loyalty. Google's motto was "Don't be evil," and early employees believed it meant something. Facebook would "move fast and break things" toward connecting humanity. These framing devices gave people a sense of larger purpose.

Today's AI researchers have watched tech become more cynical. They've seen the consequences of moving fast without asking hard questions. The idealism has been replaced by something more transactional but potentially more honest.

Instead of "we're building something great," it's now "we're solving the hardest technical problems in machine learning." Instead of "we're changing the world," it's "we're advancing the frontier." The framing is narrower, more focused, less ambitious in its claimed moral dimension.

This actually enables more movement. If you're building for impact on a specific metric (model performance, inference speed, safety), and you believe that metric will improve faster at a different organization, there's no loyalty violation in moving.

It's almost more honest than the previous generation's idealism, which often masked profit-seeking under a layer of moral purpose.

Researchers understand the limitations of the institutions they're working in. They're not naïve about whether an AI lab founded on "safety" will eventually prioritize growth over safety when the stakes get high. They're not shocked when a startup pivots away from its original mission. They expect it.

Given that expectation, loyalty becomes irrational. You might as well optimize for your own learning, compensation, and impact. Stay at a place as long as it's the best accelerator for your growth. Leave when you've extracted maximum value and learned what you came to learn.

The Network Effect: When Everyone Moves, Movement Becomes Normal

Once talent movement reaches a critical threshold, it becomes self-reinforcing.

When the first few senior researchers at OpenAI left for Anthropic, it was a big deal. When that happened twice more, it became a pattern. Now it's the expected lifecycle of a researcher's career.

This creates a network effect that accelerates departures. If you're at OpenAI and three colleagues have left for Anthropic in the past year, it stops feeling like betrayal. It feels like the normal career path. You're not abandoning the team. You're following the route map that others have already laid out.

Moreover, having colleagues at multiple organizations becomes a feature, not a bug. Your network spans the frontier labs. You stay connected to people you've worked with. You hear about opportunities early. You can coordinate knowledge-sharing across organizations (within ethical boundaries).

This distributed network of researchers moving between labs creates a kind of informal federation among the frontier AI organizations. They're competing for talent, but also informally collaborating through the shared personnel.

It's not a conspiracy. It's just the natural outcome of intense competition for talent creating a thin upper layer of researchers who maintain connections across all the major labs.

What Stays, What Goes: The Winners and Losers

Not everyone is leaving. The geography of loyalty is unequal.

Frontier AI researchers with advanced degrees, published papers, and cutting-edge skills can exit at will. They're acquisition targets. They've got options.

Middle-tier engineers at startups are in a weird position. They're too valuable to easily replace, but not valuable enough to command mega-offers. They can get lured away to bigger companies, but they might not land in the same role or with the same growth trajectory. There's risk in moving for them.

Support staff, operations, finance, sales—these roles are staying more stable. Loyalty matters more because the opportunity cost of moving is lower. There are more similar jobs available. You're not as specialized.

What this creates is a bifurcated workforce. At the top, constant movement. In the middle and bottom, more stability. This creates organizational instability at the core where it matters most.

Companies that figure out how to retain top talent without matching every acquisition offer are going to have an advantage. But how do you do that? You'd need to offer something beyond money: remarkable autonomy, unmatched research resources, a coherent mission that actually compels belief.

Few companies can pull that off consistently.

Meta, Google, and Nvidia have invested heavily in acquiring AI talent, with Nvidia leading at

The IPO Problem: Why Going Public Looks Less Attractive

Here's a second-order effect nobody talks about: the traditional tech exit (IPO) is looking less attractive as a finish line.

For decades, the trajectory was: found startup, build for seven to ten years, take it public, founding team becomes very rich. That was the dream.

Now, why wait seven to ten years for an IPO when you can:

- Build something impressive for two to three years

- Get acquired for your talent and IP

- Walk away with $50-100+ million

- Start something new if you want

An IPO requires maintaining a cohesive company with stable leadership for years. An acqui-hire requires none of that. You can fragment the team because fragmentation is the point.

This changes the risk calculus for founders. Why bet on the long-term vision when the short-term payout for being acquirable is so high? It's rational self-interest.

Venture capital is enabling this because from their perspective, an acqui-hire at 3x returns in year three is better than an IPO at 50x returns in year ten. Certainty and speed beat potential upside for most investors.

The side effect is that fewer startups are actually trying to build sustainable, independent companies. More are building to acquire. This is healthy for the acquirers (who get top talent cheaply) and unhealthy for the startup ecosystem (which stops producing enduring companies).

Global Implications: What This Means for the Rest of the World

America's loyalty collapse is already exporting.

Top AI researchers in the UK, Canada, Europe, and Asia are watching what's happening in Silicon Valley. They see that the barrier to $50 million compensation requires working at a US-based frontier lab or getting acquired by one. They see that the research velocity is fastest in the US.

So the best people globally are migrating toward US labs. They're leaving universities and startups in their home countries. They're concentrating at OpenAI, Google DeepMind, Anthropic, Meta.

This is creating a brain drain at the global level. The countries investing heavily in AI infrastructure but unable to compete with US mega-labs are losing their best researchers.

China's kept people through a combination of nationalism and government directives. But even that's cracking as researchers realize that the latest breakthroughs are happening at US organizations.

The EU's regulatory approach (trying to build AI governance) is interesting, but it's not solving the recruitment problem. European labs still can't match US compensation or research velocity.

The long-term implication is concentration of AI capability and talent in a handful of US organizations, with government backing from countries that want to maintain leadership.

That's a geopolitical issue, not just an economic one.

The Stability Question: Can This Model Last?

Here's the uncomfortable question: is constant researcher churn actually sustainable?

In the short term, yes. Frontier labs can absorb researchers rotating in and out. They have enough capital and resources to rebuild teams quickly.

But there are longer-term costs:

Institutional memory evaporates: When researchers leave, they take knowledge. The solutions they developed, the dead ends they explored, the context they built—it all walks out the door. The next person in that role has to rebuild some of that context.

Collaboration suffers: Research requires continuity and collaboration. The deeper the collaboration, the harder it is to fragment teams. Loss of continuity means slower iteration.

Security and safety concerns: When researchers move between labs frequently, there's increased risk of IP leakage, model weights getting shared, safety insights getting distributed. Frontier labs probably want researchers to stay longer, not move around.

Morale for mid-tier people: If everyone around you is leaving for bigger opportunities, and you're not getting the same offers, morale suffers. You get resentment, reduced productivity, lower-quality work from people who are now bitter about being passed over.

So while the system is working right now, there are structural strains. These will eventually surface.

What might restore stability? Several possibilities:

-

Saturation: At some point, all the AI researchers worth acquiring have been acquired. The labor pool exhausts. Then loyalty becomes valuable again because you need to retain people long-term.

-

Regulation: If governments regulate AI talent movement (visa restrictions, IP rules, etc.), it could slow churn.

-

Competing priorities: If something other than AI becomes the frontier (quantum computing, biology, whatever), talent will disperse. AI's talent concentration is because AI is "where it's at." When that changes, so does loyalty.

-

Moral reckoning: If AI produces outcomes that are sufficiently negative, the industry's credibility could collapse. Researchers might stop chasing the frontier. Loyalty to principles might trump loyalty to organizations.

None of these are imminent, but none are impossible either.

Compensation is the most influential factor driving AI researchers between labs, followed by the access to compute and the impact of their work. Estimated data.

What Founders Should Do: Building Durable Teams in a Churn Environment

If you're starting an AI startup in 2025, you have to assume key people will leave. That's not pessimism. That's just realistic.

Given that assumption, here's what actually works:

Hire for culture fit and patience, not just talent: The smartest person might leave fastest if they're not aligned with your mission. The person who's mid-tier but absolutely committed to your specific vision will stay longer. Optimize for alignment over raw ability.

Make departures clean: When people want to leave, don't fight it. Help them transition. Document their work. Make it easy. They're going to leave anyway. You might as well maintain relationships and preserve knowledge. It also helps retention for people who see departures aren't brutal.

Build in redundancy from day one: Don't let critical knowledge or capability sit in one person's head. Pair program. Document heavily. Create systems where departure doesn't create chaos.

Understand the clock: You probably have 18-36 months before your best people get acquisition offers from bigger labs. Plan for that. Build accordingly. Structure your roadmap so that the core product works with the team you actually have, not the team you hope to have.

Create mission clarity that matters: This sounds hokey, but it actually works. If your specific mission (not "we're building AI," but "we're solving interpretability," or "we're building agentic systems safely") resonates deeply enough, people will stay longer. They have to actually believe it. Lip service doesn't work.

Compensate well, but understand you're not competing on money: You can't outbid Meta. So don't try. Instead, compete on autonomy, impact, culture, and mission. If you're paying market rate (not top-tier rate), people will stay if the other factors are strong.

The Long View: What Tech Loses When Loyalty Dies

Let's zoom out and think about what the industry loses when loyalty becomes obsolete.

Institutions are built on continuity. Universities survive for centuries because professors stay long enough to train multiple generations of students. Companies build valuable culture because teams develop relationships and understanding over years. Scientific progress happens because researchers see their work through to completion.

When everyone is constantly leaving, you lose institutional capacity. You lose the ability to think in decades. You lose the people who remember why certain decisions were made and can defend them when they're questioned five years later.

Tech has been operating in a "move fast and break things" mode for two decades. That's worked for producing consumer products and rapid scaling. But it's not clear it works for building AI systems that are safe, robust, and aligned with human values.

The researchers jumping between labs aren't bad people. They're rational actors in a system that incentivizes movement. But the system itself—constant churn, short-term thinking, optimization for personal upside—might not be optimal for building AI that humanity should actually want to exist.

That's not a problem that gets solved with better compensation or retention bonuses. It gets solved by asking harder questions about what institutions we actually need and whether the current incentive structure produces them.

Few people are asking those questions. Most are just playing the game that exists.

Future Scenario: The Bifurcated AI Ecosystem

Let's project forward five to ten years. What does this trajectory lead to?

One possibility: a bifurcated ecosystem where AI development is concentrated in mega-labs (Meta, Google, OpenAI, Anthropic) with massive capital, top talent, and enormous compute. These labs operate like research institutions with some product teams attached. Loyalty doesn't matter because the talent pipeline is continuous and replaceable at high levels.

Everyone else—smaller startups, academic institutions, international competitors—operates in the gaps. They build niche applications, specialized tools, local solutions. They can't compete on the frontier because they don't have the capital or talent density.

The innovation happens in the mega-labs. The adaptation happens in the smaller ecosystem.

This isn't dystopian. But it's a very different structure than the one we've had for the past 20 years, where innovation could happen in small scrappy teams that grew into giants.

Another possibility: talent saturation and consolidation. At some point, all the AI researchers worth acquiring have been absorbed. The mega-labs hit diminishing returns on hiring. New talent becomes harder to find. People who've been acquired and moved multiple times get tired. Loyalty becomes relevant again because there's nowhere else to go.

A third possibility: regulatory intervention. If governments decide that AI development is too important to be left to market dynamics, they could impose rules on talent mobility, IP transfer, or capital concentration. This would slow churn dramatically.

None of these are certain. But all are plausible.

Why This Matters to You (Even If You're Not in Tech)

You might not work in AI or startups. But this shift in loyalty patterns affects you.

First, it affects what AI systems get built. When research institutions are optimized for speed and capital deployment rather than careful thinking and long-term safety research, the systems that emerge reflect those priorities. Faster, more capable, less scrutinized.

Second, it affects which countries control AI. If talent concentrates in US mega-labs, and other countries can't compete, then US strategic dominance in AI increases. That has geopolitical consequences.

Third, it affects labor more broadly. Tech's shift from loyalty to transactionalism is spreading. If tech normalizes constant job-switching, high compensation for top performers, and rapid churn, other industries will start copying it. Your industry might be next.

Finally, it affects the kind of culture we're building. A culture where everyone is optimizing for personal upside, where institutions are means to personal ends, where loyalty is irrational—that's a specific kind of culture. It emphasizes individual achievement over collective purpose. Whether that's good or bad is your judgment. But it's worth noticing.

FAQ

What exactly is an "acqui-hire" and how does it differ from a traditional acquisition?

An acqui-hire is when a larger company buys a startup primarily to acquire its team, rather than to use the startup's product or technology. Traditional acquisitions focus on the company's intellectual property, customer base, and product. Acqui-hires focus on talent. The startup's product might be shut down, but the engineers and researchers are integrated into the acquirer's organization. This has become common in AI, where frontier labs like Meta, Google, and Nvidia are willing to spend billions specifically to bring research teams in-house.

Why do researchers leave their startups for larger companies if they could build something independent?

Several factors drive this decision. Larger labs offer access to massive computing resources that smaller startups can't afford. They offer immediate deployment at scale—your research affects millions of users within weeks rather than years of bootstrapping. There's also the compensation factor. Meta offers tens or hundreds of millions of dollars to elite researchers. Additionally, working with the smartest people on the hardest problems creates a psychological pull. A researcher at a frontier lab also feels they're contributing to the cutting edge of their field, which matters deeply to many in academic or research-oriented backgrounds.

How does this affect the quality of innovation coming from Silicon Valley?

That's complex. On one hand, concentration of talent and capital in frontier labs means those labs produce the most advanced work. Models from OpenAI, Google DeepMind, and Anthropic advance the field faster than distributed innovation could. On the other hand, rapid researcher churn means less institutional continuity, less deep thinking about long-term safety implications, and more optimization for speed and capability over prudence. There's also a risk that smaller startups and academic institutions lose talented researchers, which could slow innovation in other domains.

What's the impact on founders who stay committed to their companies?

Founders who stay committed despite acquisition offers often feel left behind. If their best researchers get recruited away by mega-labs, the founder's original vision might fragment. However, some founders leverage this by positioning their startup as an "acquisition target for talent." They build something impressive enough to attract an acqui-hire offer, then negotiate how their team integrates. This is pragmatic rather than idealistic, but it reflects the new reality of startup building.

Can investor protections actually prevent talent from leaving?

Not entirely. Clauses like board consent requirements for material IP transfers or clawback provisions might slow departures, but they can't truly prevent them. If someone gets a $100 million offer from Meta, legal barriers are unlikely to stop them. What investor protections do is raise the cost slightly and give the startup some negotiating leverage. They might require the departing researcher to train a replacement or document their work. But the core issue—that bigger opportunities are available elsewhere—remains structural.

Is loyalty actually dead, or is it just changing form?

It's transforming rather than disappearing. Team members might stay loyal to their collaborators rather than their company. Researchers might stay loyal to a specific research agenda rather than an organization. Compensation packages increasingly include golden handcuffs (multi-year vesting schedules) that create artificial loyalty. But the old model—where you joined a startup and expected to stay for a decade or more—is definitely dead for elite researchers in AI.

How does this trend affect people outside of AI?

It's spreading. As AI becomes central to tech, the norms established in AI are influencing broader tech culture. High-performer churn, acquisition targeting of teams rather than products, and optimization for short-term movement are becoming normalized. Additionally, as the tech industry's culture shifts, it influences other knowledge worker fields. Some of these trends are already visible in finance, consulting, and academia.

What would actually restore long-term loyalty in tech?

Several possibilities exist. Saturation of the labor market would make loyalty valuable again. Regulatory intervention could restrict talent mobility. A major negative event in AI could reduce the industry's attractiveness. Or cultural shifts could re-emphasize institutional loyalty over personal optimization. None of these are imminent, but all are possible. Some would argue that what's needed is a shift in mission-driven work—companies that have such compelling purposes that leaving feels like a real loss. But that requires believing in institutions again, which isn't fashionable right now.

Conclusion: The New Normal and What Comes Next

Loyalty in Silicon Valley didn't die overnight. It eroded gradually, then all at once.

One year at a frontier AI lab became worth five years at a traditional company. That compression of time made staying feel irrational. Compensation packages in the tens or hundreds of millions made loyalty feel foolish. Access to cutting-edge resources and compute created obvious incentives to move. The tech industry's moral authority collapsed, making idealistic commitment harder to justify.

Now we have a new equilibrium. Researchers expect to move between frontier labs every two to four years. Founders build startups knowing their teams will be partially broken up by acquisition offers. Investors structure deals expecting that outcome. Everyone is optimizing for personal upside in a system that rewards rapid movement.

This works, at least in the short term. The frontier labs are building more advanced AI systems faster than ever. Researchers are getting richer. Capital is efficiently deployed. Products reach millions of people. By conventional metrics, it's working.

But there are costs. Institutional knowledge walks out the door when people leave. The long-term thinking that built previous generations of tech gets replaced by quarter-by-quarter optimization. Safety and alignment research gets deprioritized relative to raw capability. The people asking "should we?" get less resources than the people asking "how do we?" faster.

And it's concentrating power. The mega-labs are pulling talent from everywhere else. Smaller startups can't compete. Academic institutions are losing researchers. International competitors can't keep up. The result is increasing concentration of AI capability in a handful of organizations, mostly in the US.

What comes next depends on what breaks first. Does the talent market saturate? Does regulation intervene? Does something else become more important than AI? Does the moral reckoning finally arrive?

For now, we're in the era of the unbundled startup and the researcher in transition. Loyalty is dead. Long live optimization. Welcome to Silicon Valley in 2025.

Key Takeaways

- Founder and researcher loyalty has collapsed in Silicon Valley, with mega-labs now regularly acquiring startups for talent rather than technology

- Meta (2.4B), and Nvidia ($20B) have made record acquisitions focused on pulling research teams into their labs

- AI researchers now expect to move between frontier labs every 2-4 years, with compensation packages reaching tens or hundreds of millions of dollars

- One year at an AI startup feels equivalent to five years at a traditional tech company due to compressed innovation timelines and rapid scaling

- Investors are adapting deal structures with protective provisions and cohesion testing to minimize damage from talent departures

- Academic institutions are losing PhD researchers mid-program as industry offers prove more attractive than traditional academic paths

- Concentrated talent at mega-labs creates both innovation acceleration and concentration of AI capability in few organizations, raising geopolitical implications

- Smaller startups now operate as acquisition targets expecting their teams to be partially broken up rather than as independent growth companies

Related Articles

- The ARR Myth: Why Founders Need to Stop Chasing Unrealistic Growth Numbers [2025]

- OpenAI GPT-5.3 Codex vs Anthropic: Agentic Coding Models [2025]

- Claude Opus 4.6: Anthropic's Bid to Dominate Enterprise AI Beyond Code [2025]

- Moltbook: The AI Agent Social Network Explained [2025]

- Mundi Ventures' €750M Kembara Fund: Europe's Deep Tech Revolution [2025]

- Google Gemini Hits 750M Users: How It Competes with ChatGPT [2025]