Google's Search Antitrust Appeal: The Complete Guide to the 2024 Monopoly Ruling and Its Implications

Introduction: Understanding the Historic Antitrust Case Against Google

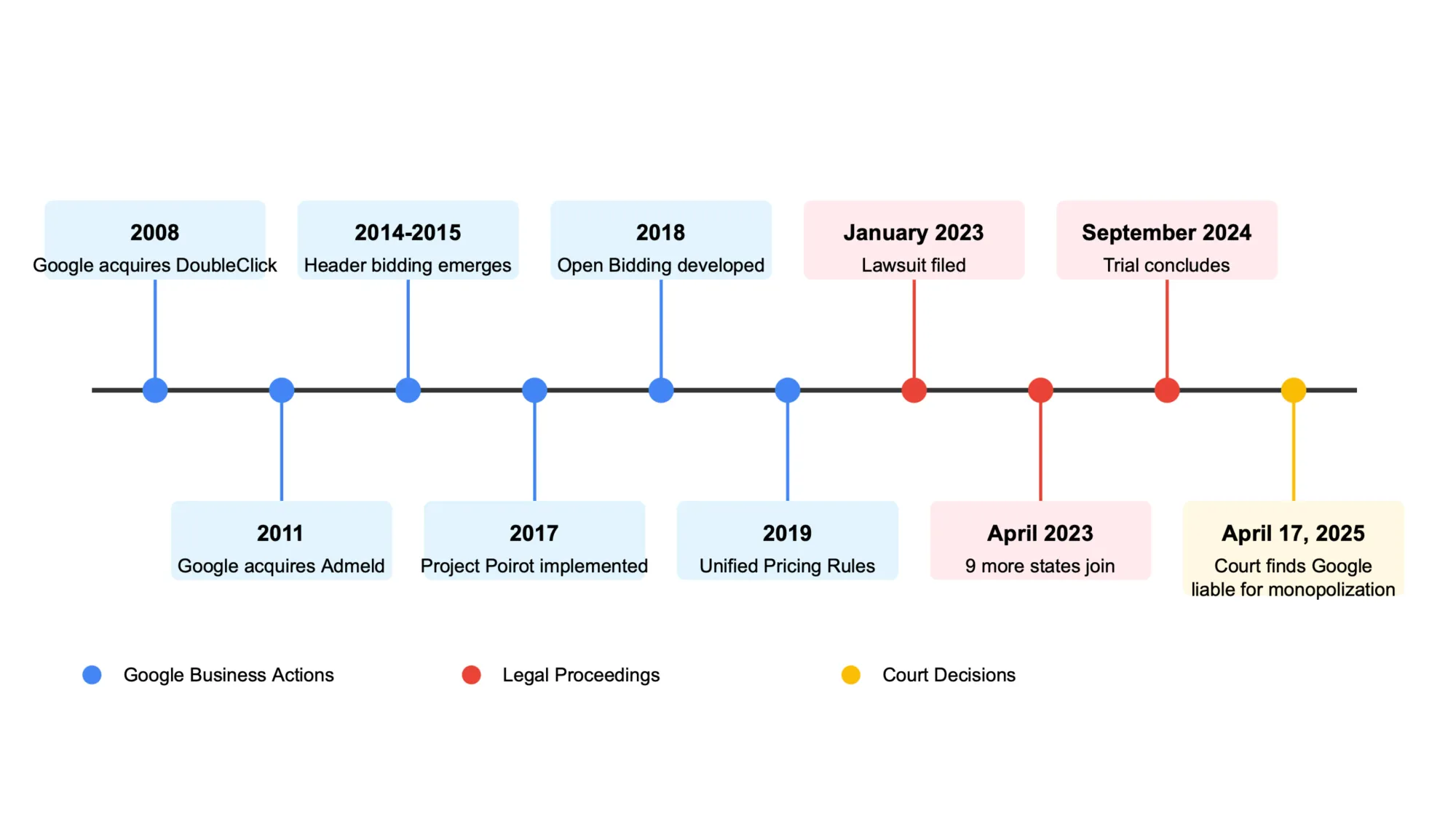

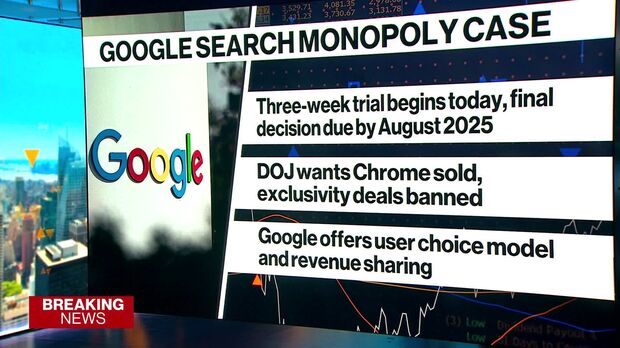

In August 2024, a federal judge delivered one of the most significant tech industry rulings in recent memory: Google was found to maintain an illegal monopoly in web search. This landmark decision capped a lengthy legal battle that began with the Department of Justice's 2020 complaint, alleging that Google had systematically leveraged its search dominance to exclude competitors and entrench its market position across multiple platforms. The ruling represented a watershed moment for technology regulation in the United States, signaling that even the most powerful tech companies would face consequences for anticompetitive behavior.

Now, as 2025 unfolds, Google has taken the next logical step in its legal strategy by appealing the ruling and simultaneously requesting that the implementation of remedies be paused pending the appeals process. This move reflects the extraordinarily high stakes involved—the remedies could fundamentally reshape how Google operates and how data flows between search competitors. Understanding this complex legal landscape is crucial for anyone interested in technology policy, competition, digital markets, and the future of search innovation.

The case touches on fundamental questions about how the internet economy functions. Does Google's market dominance stem from superior product quality and user choice, as the company contends? Or does it result from anticompetitive practices that lock out competitors and harm consumers through reduced innovation? The answers to these questions will determine whether future tech companies face similar regulatory scrutiny and how data access, browser defaults, and advertising practices evolve across the industry.

This comprehensive guide examines every facet of Google's search antitrust case, the appeals process, the proposed remedies, and what these developments mean for the competitive landscape, consumer choice, and the future of digital innovation. Whether you're a developer, business leader, entrepreneur, or simply interested in how technology regulation shapes the digital world, this analysis provides the context and insights you need to understand one of the most consequential legal cases of our time.

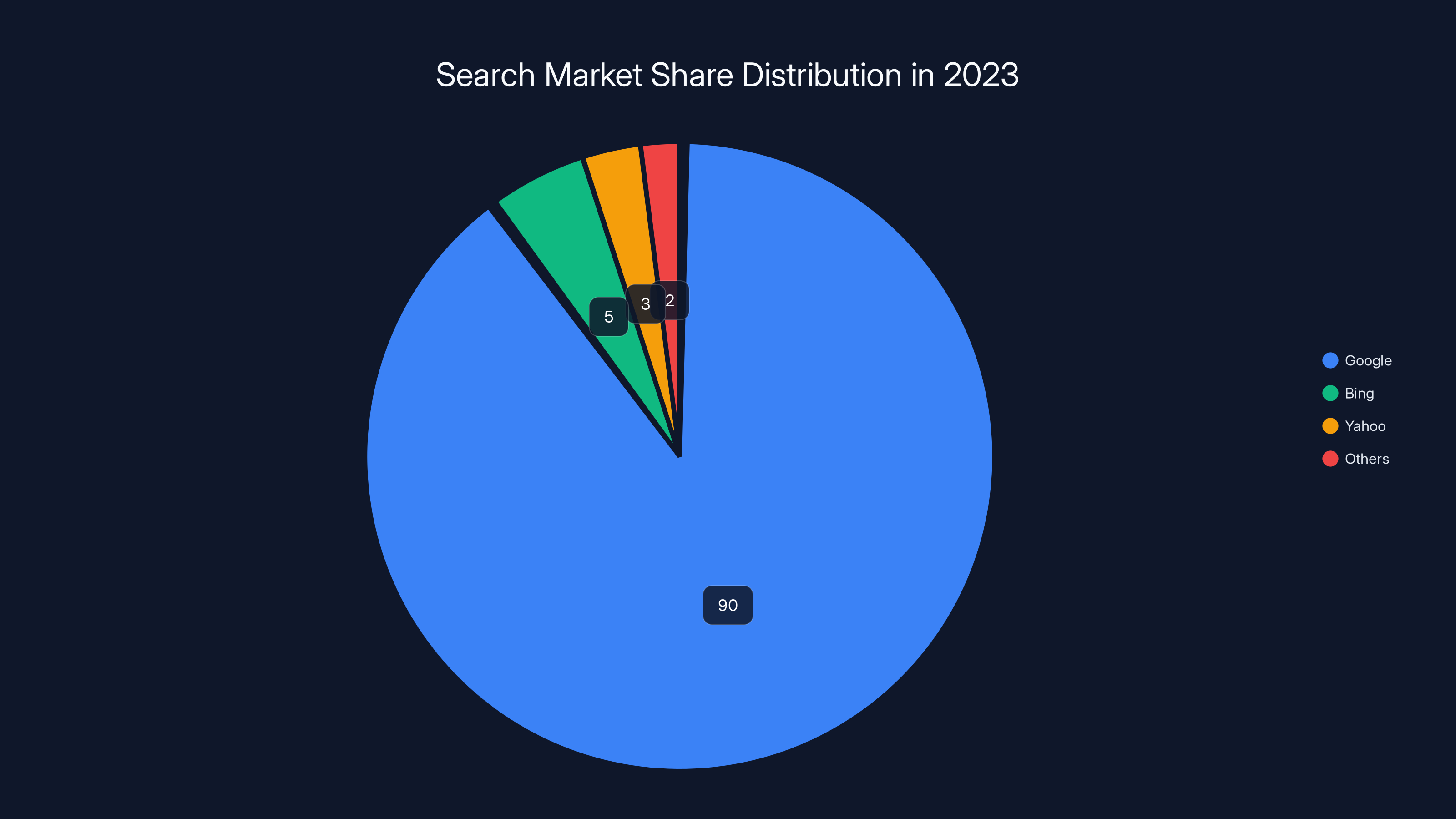

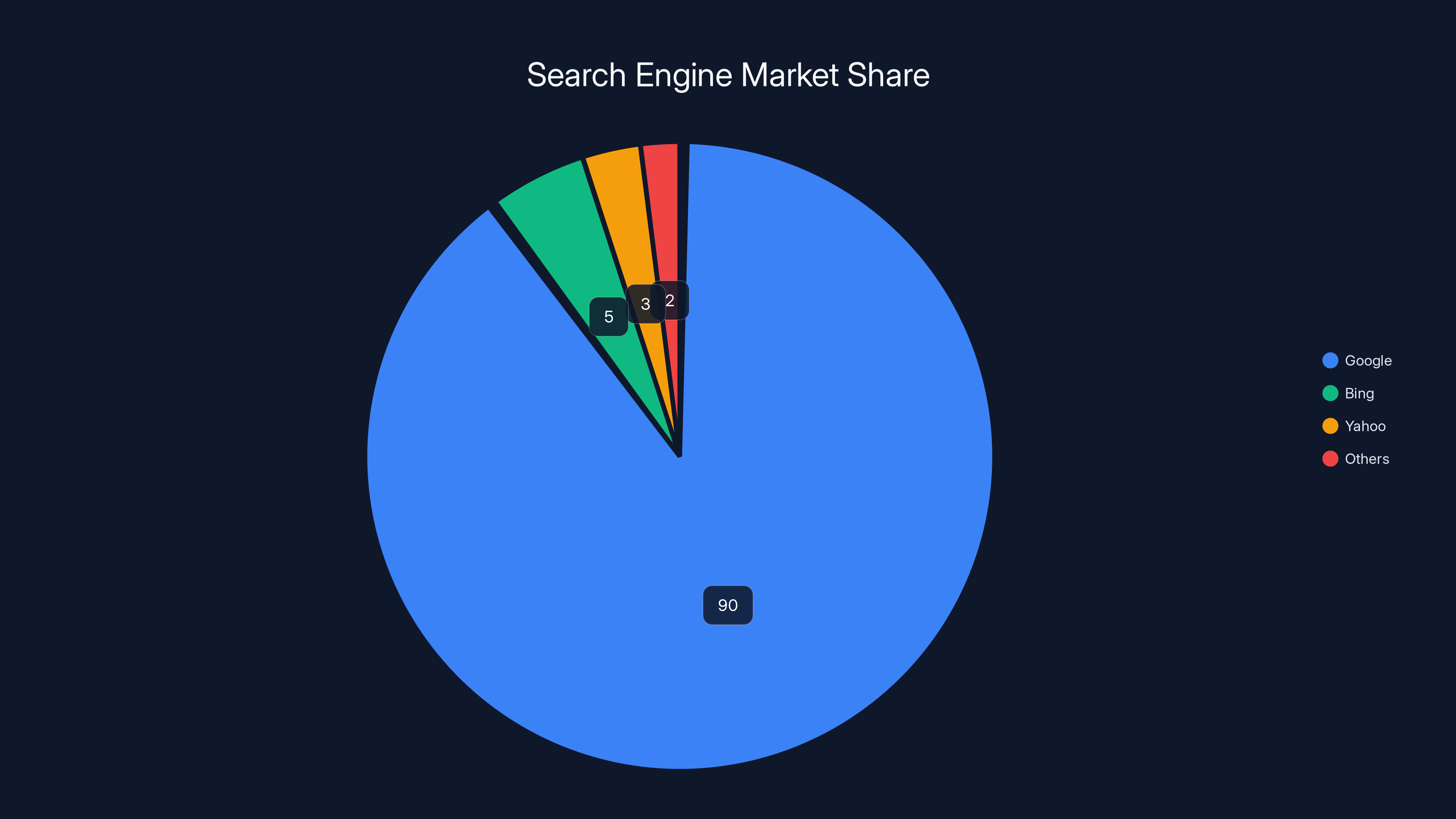

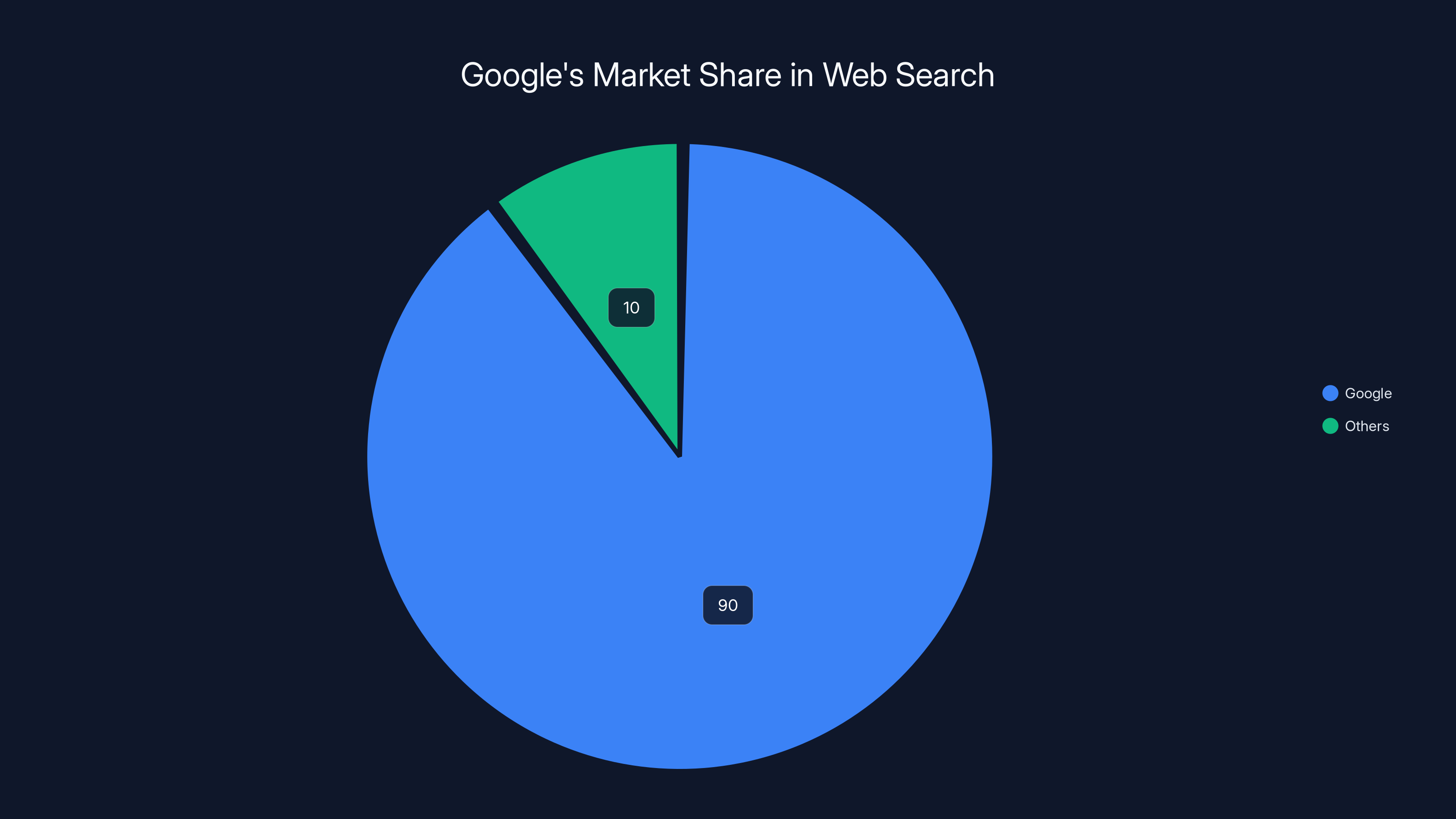

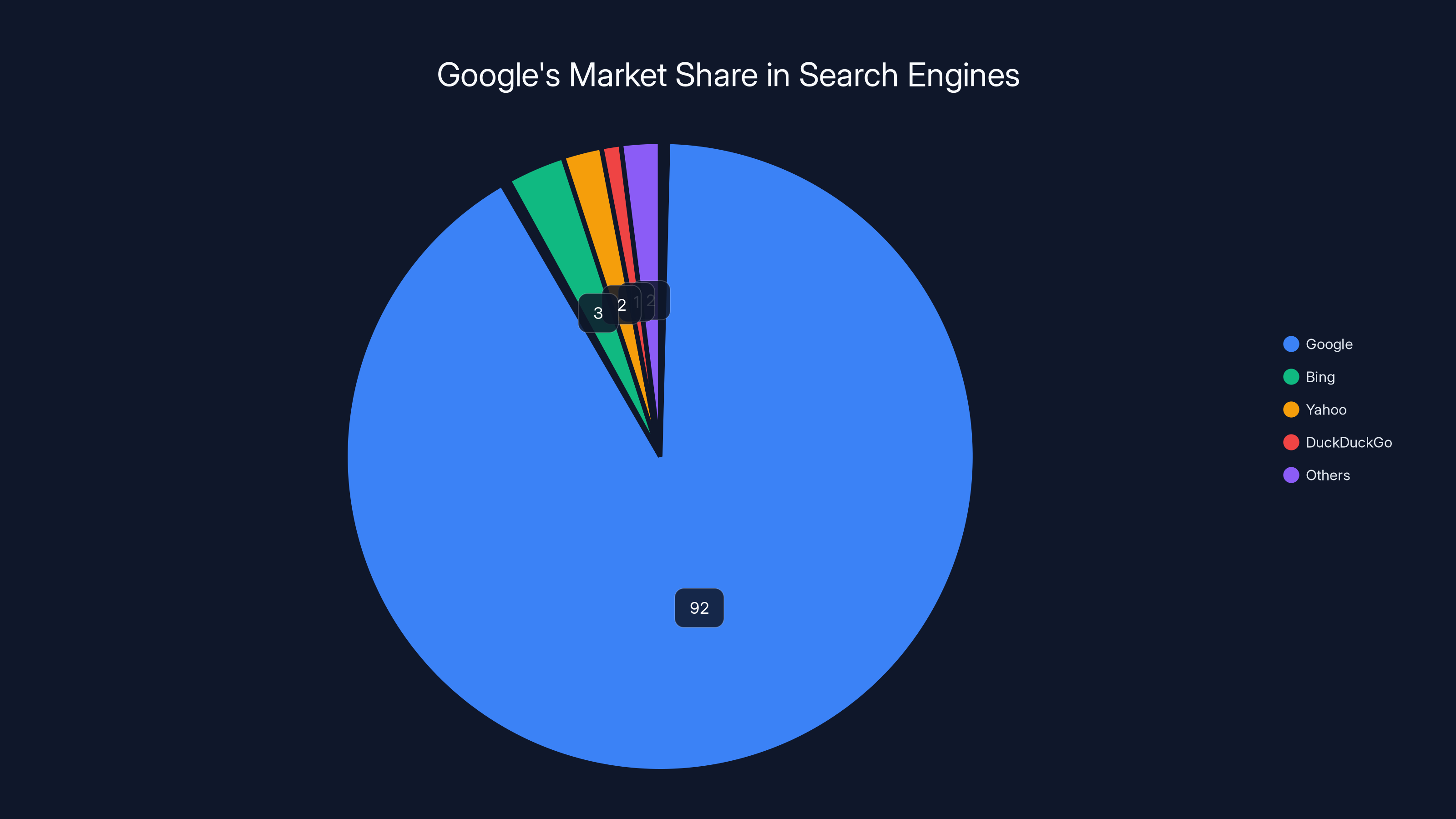

Google's dominance in the search market was a focal point of the trial, with over 90% market share, highlighting its significant control over search queries. (Estimated data)

The Origins of the Case: How the DOJ Built Its Antitrust Complaint Against Google

The 2020 Department of Justice Complaint

The government's case against Google didn't emerge overnight. The Department of Justice spent months investigating the company's practices before filing its complaint in October 2020, marking the most significant antitrust action against a tech company since the Microsoft case decades earlier. The DOJ's complaint alleged that Google had maintained and reinforced its dominance in search through a series of interconnected, anticompetitive practices rather than through superior innovation alone.

The complaint identified several key mechanisms through which Google allegedly maintained its monopoly. First, the government argued that Google had secured exclusive default search agreements with major platforms including Apple's Safari, Mozilla's Firefox, and various Android device manufacturers. These agreements meant that when users opened their browsers or devices without actively choosing a search engine, Google was the default option. The complaint suggested these exclusionary agreements prevented competitors like Bing, Duck Duck Go, and others from gaining the visibility necessary to compete effectively.

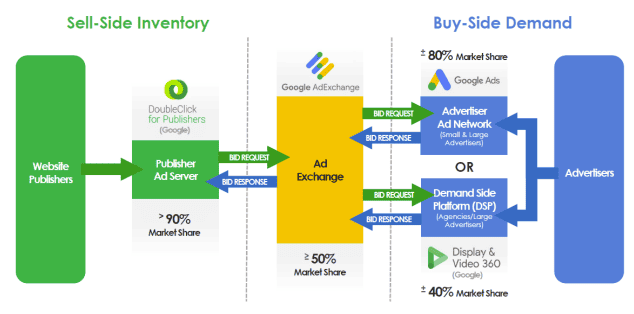

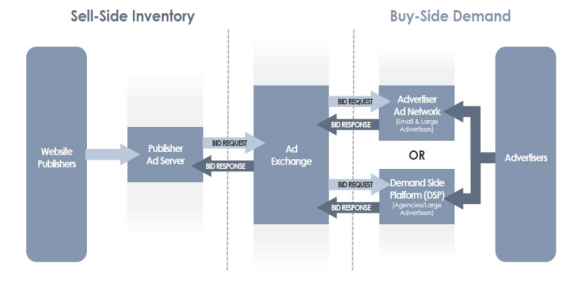

Second, the DOJ focused on Google's control over search results and advertising. The government contended that Google used its search dominance to privilege its own services and advertising products while marginalizing competitors. This vertical integration—combining search with advertising services—created potential for anticompetitive behavior that benefited Google at the expense of both competitors and advertisers.

Third, the complaint highlighted how Google leveraged its control of the Chrome browser and Android operating system to reinforce search dominance. By making Google search the default across these platforms, and by integrating search functionality deeply into these ecosystems, Google created multiple reinforcing barriers to entry for competitors.

The Expanded Scope During Investigation

As the DOJ's investigation proceeded through discovery and testimony collection, the case expanded in scope and sophistication. Federal investigators obtained internal Google documents that allegedly showed deliberate strategies to maintain search dominance. The government conducted extensive depositions with executives from competitor companies, platform providers, and industry experts who testified about market dynamics and Google's competitive practices.

The investigation revealed that Google had paid billions of dollars annually—estimates suggest $15-20 billion per year—to secure default search agreements with Apple and Mozilla. These payments, while legal on their face, raised questions about whether they represented legitimate competition or exclusionary practices. The sheer magnitude of these payments suggested that without them, competitors might gain market share, raising questions about whether Google's dominance reflected consumer preference or rather the power of its default status.

Additionally, the investigation exposed how Google's acquisition strategy had consolidated the search market. The company had acquired companies like Waze, ITA Software, and numerous other firms that might have developed into meaningful competitors. While individual acquisitions might be defensible on efficiency grounds, the cumulative pattern suggested a strategy of removing competitive threats before they could scale.

State-Level Coordination and Multi-Jurisdictional Pressure

Beyond the federal complaint, numerous state attorneys general joined the antitrust effort. Texas led a coalition of states in filing a separate complaint focusing on similar alleged anticompetitive practices. This multi-jurisdictional pressure reflected growing concern across state governments that Google's practices harmed competition and innovation within their economies.

The state-level involvement added significant complexity to the litigation landscape. While federal cases focus on interstate commerce and national market effects, state cases can emphasize local impacts on consumers and businesses within specific states. This multi-pronged legal approach meant Google faced pressure from multiple directions simultaneously, increasing the stakes for the company and the range of potential remedies that could be imposed.

The 2024 Trial and Verdict: What the Judge Actually Found

The 10-Week Trial: Evidence and Arguments Presented

The trial, held in 2023 and concluded with a verdict in August 2024, represented an exhaustive examination of search market dynamics and Google's competitive practices. Over ten weeks, both sides presented extensive evidence. The Department of Justice called expert economists, industry practitioners, and Google executives to testify about market structure, competitive dynamics, and the effects of Google's practices on rivals and consumers.

The government's case focused on demonstrating three key elements: that Google possessed monopoly power in search, that the company had maintained that power through anticompetitive rather than pro-competitive means, and that these practices had resulted in harm to competition and innovation. Federal prosecutors presented evidence showing Google's dominance in search queries (which exceeded 90% market share in many markets), its control over search results presentation, and how default agreements reinforced this dominance.

Google countered by arguing that its search dominance resulted from superior quality, that users actively chose Google because it provided better results, and that competition in search remained vibrant with alternatives available. The company emphasized rapid innovation, including investments in artificial intelligence and features that improved search utility. Google also highlighted testimony from companies like Apple and Mozilla, which stated they featured Google as the default search engine because it provided the best search experience for their users.

The Judge's Findings on Market Definition and Dominance

In his August 2024 ruling, Judge Amit Mehta found that Google maintained illegal monopoly power in general search services. This finding represented a critical determination—establishing monopoly power is the essential first element of any antitrust case. The judge found that the relevant market was "general search services," meaning searches conducted on any device for any purpose, and that Google's dominance in this market was clear and sustained.

The judge emphasized the significance of Google's default status across browsers and devices. While the company argued that users could easily switch to competitors, the judge found that default status created a powerful competitive advantage. Behavioral economics research presented during the trial demonstrated that default options exercise enormous influence over user behavior—most users don't actively select alternatives even when they're readily available. This finding proved crucial, as it suggested Google's dominance reflected the power of defaults rather than pure quality superiority.

Crucially, the judge found that the default search agreements Google had negotiated—particularly the massive payments to Apple for exclusive placement—constituted anticompetitive conduct. Rather than competing on quality alone, Google was using financial power to lock competitors out of prominent distribution channels. This finding suggested that without these exclusionary agreements, the search market would look substantially different.

The Determination of Anticompetitive Conduct

Beyond establishing dominance, the judge found that Google had maintained its position through anticompetitive practices rather than competition on the merits. Specifically, the ruling identified several categories of conduct as problematic. First, the exclusive default search agreements with Apple, Mozilla, and other platforms were found to constitute illegal exclusionary practices. These agreements prevented competitors from achieving the visibility necessary to compete effectively.

Second, the judge found that Google's integration of search with advertising services and its use of proprietary data created anticompetitive advantages. By combining its search monopoly with dominance in search advertising, Google could favor its own services and disadvantage competitors in ways that harmed both advertisers and users.

Third, the ruling addressed how Google leveraged its Android operating system and Chrome browser to reinforce search dominance. By making Google search deeply integrated into these platforms and making it difficult for users to select alternatives, Google created reinforcing barriers to competition.

Importantly, the judge rejected Google's primary defense—that its dominance resulted from superiority. While acknowledging that Google's search quality was indeed strong, the judge found that superior quality couldn't explain the systematic exclusion of competitors through default agreements and other practices. Quality and exclusionary conduct aren't mutually exclusive; a company can have superior products while also engaging in anticompetitive practices.

Google holds a dominant 90% market share in the search engine industry, illustrating the strong network effects and data advantages that create barriers for competitors. Estimated data.

The Proposed Remedies: What Would Change if Implemented

Data Sharing Requirements and Syndication Services

The remedies proposed by the Department of Justice—and adopted in modified form by the judge—represent potentially transformative changes to Google's business model. The central remedy, and the one Google most vehemently opposes, requires Google to provide syndication services to competitors and to share search data with rival search engines. This requirement represents a radical departure from how search has traditionally functioned.

Under this remedy, Google would be required to make its search index—the massive database of web pages and their characteristics—available to competitors. Additionally, Google would need to share certain aggregated search data that could help competitors understand how users were interacting with search results. This data-sharing requirement aims to level the competitive playing field by giving competitors access to information that Google previously possessed exclusively.

The rationale for this remedy rests on a fundamental insight: Google's dominance is partially self-reinforcing. Because Google processes the vast majority of search queries, it accumulates enormous amounts of data about what users are searching for, which results they click on, and how search behavior evolves. This data advantage allows Google to improve its search algorithms faster than competitors, further entrenching dominance. By requiring data sharing, the remedy attempts to break this reinforcing cycle.

Google argues this remedy is problematic for multiple reasons. First, the company contends it raises privacy concerns—sharing search data could potentially expose user information or make it available to third parties in ways that harm privacy. Second, Google argues that forced syndication requirements would "discourage competitors from building their own products," as companies might simply resell Google's index rather than developing genuinely differentiated search technologies. The company suggests that rather than spurring innovation, data-sharing requirements might reduce incentives for competitors to invest in their own search infrastructure.

Browser Default Changes and Operating System Requirements

The original DOJ proposal would have required Google to divest its Chrome browser—a radical remedy that would effectively separate Google's dominance in one product category (search) from its control of important distribution channels (browsers). A browser divested from Google would have had incentives to feature the best search engine rather than Google's search, potentially redistributing search traffic to competitors.

Judge Mehta stopped short of requiring Chrome divestiture but imposed other significant remedies related to defaults. The remedy requires Google to unbundle Chrome from Android and to cease using its control of these platforms to advantage Google Search. Additionally, the remedy requires Google to cease certain exclusive default arrangements, allowing device manufacturers and browsers to more easily feature competing search engines.

These default-related remedies attempt to address the fundamental finding that Google's dominance partially derives from its ability to make itself the default across platforms. By removing these defaults-based advantages, the remedies would theoretically allow users to more easily select alternatives and allow competitors to gain visibility.

Advertising and Conduct Restrictions

The remedies also include restrictions on how Google can leverage its search dominance to advantage its advertising products. Specifically, Google would be prohibited from using proprietary search data to advantage its advertising businesses in ways that disadvantage competitors. This restriction aims to prevent the type of vertical integration concerns—where dominance in one market is leveraged to create dominance in adjacent markets—that characterized much of the government's case.

Additionally, the remedies impose "most-favored-nation" clauses prohibiting Google from making exclusive arrangements with major platforms. This prevents the company from securing exclusive default positions in exchange for superior terms, a practice that had previously been a cornerstone of Google's strategy.

Google's Appeal Strategy: Legal Arguments and Rationale

Challenging the Market Definition and Monopoly Finding

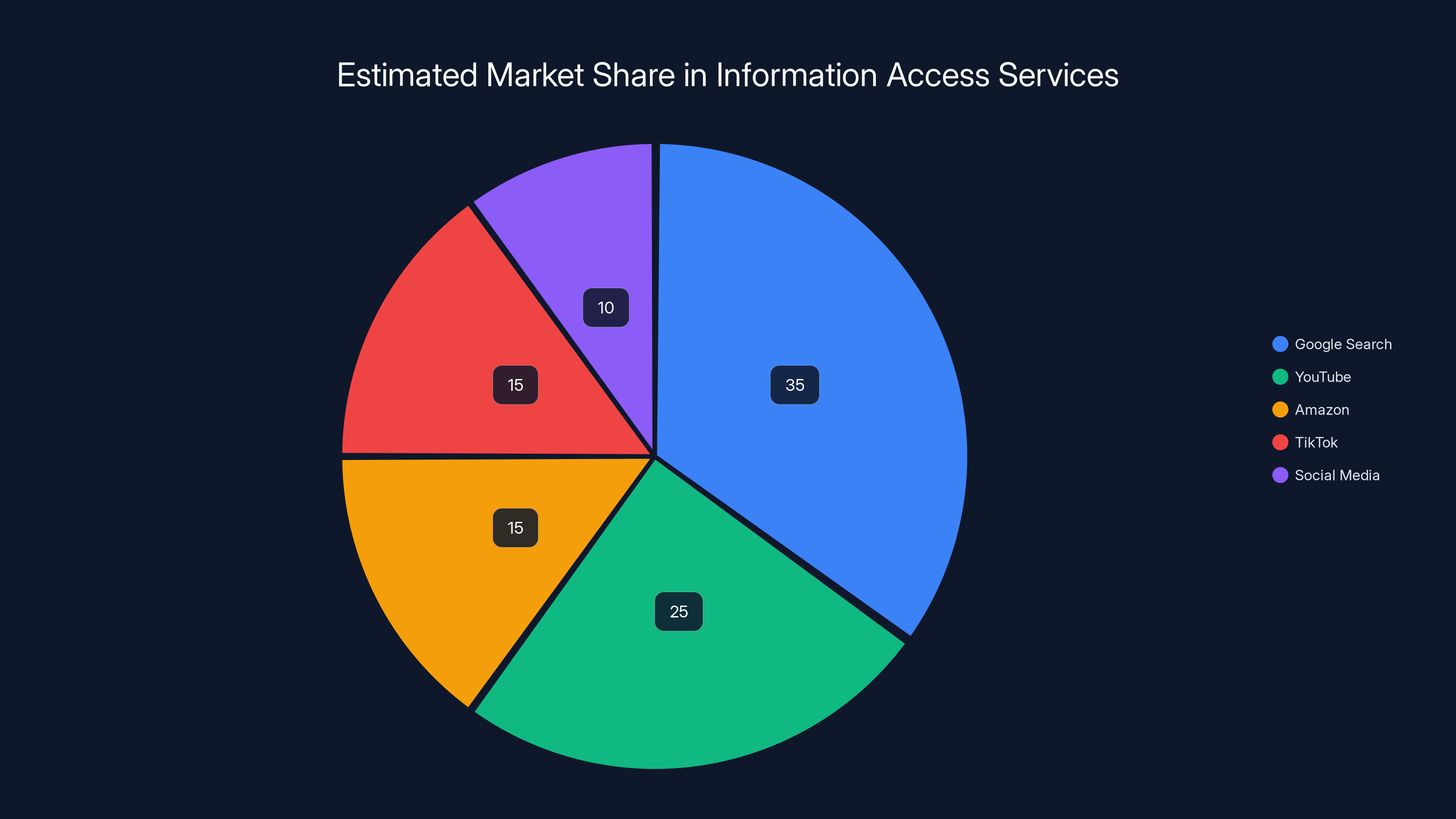

Google's appeal challenges the fundamental findings of the trial court on multiple grounds. The company's first major argument contests the definition of the relevant market. Google argues that the proper market is not "general search services" but rather "information access services" more broadly. In this broader market, Google faces fierce competition from platforms like YouTube (for video content), TikTok (for discovery), Amazon (for product search), and social media platforms (for information discovery).

From this perspective, Google's 90%+ market share in web search becomes far less impressive. YouTube, for instance, is a form of search and information discovery. TikTok's algorithm helps users discover content. Amazon's search functionality helps users find products. If users are accessing information from multiple sources rather than exclusively from Google Search, then Google's market power is substantially constrained.

This market-definition argument has historical precedent. In previous tech antitrust cases, courts have grappled with how broadly to define relevant markets. Defining markets too narrowly can overstate market power; defining them too broadly can understate it. Google will argue that the district court erred by defining the market too narrowly and thus overstating Google's dominance and exclusionary potential.

Google also challenges whether it actually possesses monopoly power in whatever market is deemed relevant. The company emphasizes that search is in a state of rapid technological change, with new competitors emerging regularly. Google points to increasing competition from AI-powered search alternatives, from vertical search engines focusing on specific domains, and from embedded search functionality within platforms. The company argues these emerging competitors demonstrate that monopoly power is not as entrenched as the government suggested.

The Voluntary Choice and Quality Defense

Google's second major appellate argument emphasizes that its search dominance results from voluntary consumer choice rather than anticompetitive conduct. The company highlights evidence showing that users actively prefer Google Search and that competitors remain available. Safari users can change their default search engine; Firefox users can select alternatives; Android users can install competing search apps. The mere fact that most users don't exercise these options, Google argues, reflects quality preference rather than anticompetitive harm.

Google bolsters this argument by pointing to testimony from competitors and platform providers. Apple, Mozilla, and other witnesses testified that they feature Google Search by default specifically because it provides superior search results. Google argues this testimony demonstrates that its dominance results from quality competition, which antitrust law should not penalize. Under this view, requiring Google to compromise on quality or to share proprietary data because competitors can't match its quality represents a punitive approach to antitrust that discourages innovation and investment.

The company also emphasizes that no end consumer has been harmed. Users get free search service of exceptional quality. The competitive concerns raised by the government and adopted by the court are business-to-business issues affecting competing search engines, not consumer welfare issues. Google argues that antitrust law should focus on consumer welfare—that is, whether end consumers have been injured—rather than on whether competitors face difficulty competing with a superior product.

Challenging the Remedy Efficacy and Appropriateness

Google's third appellate argument focuses on whether the proposed remedies are appropriate and likely to achieve their stated goals. The company argues that data-sharing requirements, in particular, won't foster competition but rather will result in competitors simply licensing Google's index rather than building genuinely innovative search technology. This would reduce innovation incentives across the industry rather than promoting competition.

Google also argues that the remedies are overbroad and will harm consumers. By forcing the company to degrade its ability to leverage data for quality improvements, or by forcing the company to unbundle products and services that work well together, the remedies will result in worse search experiences for users. This harm, Google contends, outweighs any speculative benefits to competitors.

Additionally, Google challenges whether the remedies address actual harm. If the government's theory of harm is that default arrangements create barriers to entry, then changing defaults might address the problem. But if the theory is that Google's data advantages and technical superiority make competition inherently difficult, then changing defaults won't help competitors—they still face the fundamental challenge of competing with a technically superior product.

International Precedent and Regulatory Comparison

Google's appeal also invokes international precedent and regulatory approaches adopted in other jurisdictions. The European Union, for instance, has imposed significant fines on Google and required certain changes to practices, but hasn't forced data sharing on the scale proposed in the U.S. case. Google argues that the U.S. remedies are more aggressive and potentially counterproductive compared to approaches taken elsewhere.

The company highlights how other countries balance innovation incentives against competition concerns. Google argues that the U.S. should adopt a more measured approach that addresses specific anticompetitive practices (like exclusive default arrangements) without imposing sweeping remedies that fundamentally alter business models and reduce incentives for investment and innovation.

The Department of Justice's Counter-Arguments and Case Defense

Reinforcing the Monopoly Power Finding

The Department of Justice, defending its original complaint and supporting the district court's ruling, maintains that the evidence overwhelmingly demonstrates Google's monopoly power. The government emphasizes that market share alone—Google's 90%+ share of search queries—establishes dominance. Additionally, the government points to barriers to entry that make it extraordinarily difficult for competitors to challenge Google's position.

These barriers include the network effects of search: as Google processes more queries, it accumulates more data, which improves its algorithms, which attracts more users, which generates more queries, creating a self-reinforcing cycle. Network effects of this magnitude represent genuine barriers to entry that can't be overcome through quality competition alone. The government argues that Judge Mehta correctly identified these structural features of the search market.

The DOJ also emphasizes that Google's own conduct—the billions of dollars paid for exclusive default arrangements—reveals the company's recognition that its dominance wouldn't persist absent these exclusionary agreements. If Google truly dominated through quality alone, why would it spend such enormous sums to secure default placements? The fact that Google paid these premiums suggests the company recognized that competitors could gain market share absent the defaults.

Addressing Quality and Innovation Arguments

The government acknowledges that Google provides excellent search service but argues that quality and anticompetitive conduct are not mutually exclusive. A company can provide superior products while simultaneously engaging in practices that exclude competitors and entrench dominance. The government points to historical precedent: Microsoft provided quality software products while engaging in anticompetitive conduct; Standard Oil provided reliable oil supplies while monopolizing distribution.

Regarding innovation, the government argues that competition, not monopoly, drives innovation. By maintaining exclusive control over search through anticompetitive means, Google has reduced competitive pressure and thus reduced innovation incentives. Alternative search engines might introduce innovations that improve search experiences, but they can't achieve scale because Google's defaults prevent them from gaining visibility. Removing these barriers would unleash innovation by allowing genuinely competitive search products to reach consumers.

The government also challenges Google's implicit assumption that current search technology represents the optimal endpoint. Search continues to evolve, with new AI-powered approaches emerging constantly. The government argues that competitive search markets would accelerate this innovation, as competitors pushed each other to adopt new technologies faster. Google's monopoly position actually reduces innovation incentives by insulating the company from competitive pressure.

The Data Sharing Remedy and Privacy Concerns

The government defends the data-sharing remedy by arguing that privacy concerns are overstated and manageable. The proposed data sharing would involve aggregated, anonymized information rather than personally identifiable information. Appropriate safeguards can protect privacy while enabling competitors to access the information necessary to compete. The government notes that other regulated industries manage data sharing with appropriate privacy protections, and search is no exception.

Moreover, the government argues that Google's privacy argument rings hollow given the company's extensive data collection and use practices in other contexts. Google collects vast amounts of user data for advertising and tracking purposes. Requiring the company to share aggregated, anonymized search data—with appropriate privacy safeguards—represents a proportionate remedy that doesn't exceed privacy invasions the company already engages in.

Google controls approximately 90% of web search queries, highlighting its dominance in the market. This dominance is attributed to anticompetitive practices rather than superior quality.

Market Dynamics in Search: How Dominance Translates to Exclusion

The Network Effects and Data Advantages in Search

Underlying the antitrust case is a fundamental economic truth: search markets exhibit strong network effects and cumulative advantages that can entrench dominance. As Google processes more search queries, the company accumulates more data about search behavior, which feeds into machine learning algorithms that improve search quality, which attracts more users and queries, creating a virtuous cycle for Google and a vicious cycle for competitors.

This dynamic explains why market share in search has been so stable—Google has maintained approximately 90% market share for over a decade despite constant attempts by competitors to gain share. This stability isn't necessarily because Google's search is infinitely superior, but because the data advantages and network effects create powerful barriers to competitive entry. A competitor starting from scratch would need to accumulate years of search data before achieving competitive quality, yet users wouldn't switch to an inferior search experience while waiting for that competitor to improve.

Economists refer to this dynamic as a "tipping point" market, where first-movers gain advantages that can become self-reinforcing and difficult to challenge. The search market exhibited these characteristics, with Google's early gains in market share translating into data and technology advantages that made it progressively harder for competitors to catch up.

The Role of Browser and Device Defaults

Within this landscape of structural barriers, browser and device defaults play an outsized role. Most users don't actively select search engines; they use the default provided by their browser or device. This behavioral reality means that default placement is extraordinarily valuable—it can deliver hundreds of millions of search queries annually to whichever search engine holds the default position.

Google's strategy recognized this reality and invested billions in securing default positions across platforms. The company paid Apple an estimated $15-20 billion annually to be Safari's default search engine. Similar arrangements existed with Mozilla and other platforms. These payments represented the most valuable real estate in the search market—they were worth billions because they delivered hundreds of millions of daily search queries.

Competitors couldn't match Google's payments because they lacked Google's profitability and user base. Bing, despite Microsoft's resources, couldn't justify matching Google's payments to Apple because the search volume wouldn't generate sufficient advertising revenue. Duck Duck Go and other privacy-focused alternatives were even further behind financially. This created a situation where Google could, through financial power alone, exclude competitors from viable distribution channels.

Competitive Dynamics in Adjacent Markets

Google's search dominance extends into adjacent markets, creating additional competitive concerns. In search advertising, Google maintains dominance not because its advertising products are infinitely superior, but because they're integrated with its search dominance. Advertisers must participate in Google's advertising network to reach search users; this captive advertising market generates enormous profits that fund Google's dominance in search itself.

Similarly, Google's Android operating system and Chrome browser, while providing genuine value to users, also serve as distribution channels for search. By controlling these platforms and making Google Search the default, Google ensures that hundreds of millions of users access search through Google channels daily. This integration across platforms creates reinforcing advantages that compound over time.

The Appeals Process: Timeline, Standards of Review, and Likely Outcomes

Understanding Federal Antitrust Appeals

Google's appeal will proceed through the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, one of the most important federal appellate courts and the one that typically hears technology antitrust cases. The appellate process involves significant procedural and substantive hurdles that favoring neither party systematically. Both Google's appeals and the government's counter-arguments will receive careful scrutiny.

Appellate courts apply different standards of review to different categories of judicial findings. Findings of fact—what actually happened, what evidence demonstrated—are reviewed under a deferential "clearly erroneous" standard. The appeals court will overturn factual findings only if it believes the trial court clearly made an error. This deferential standard reflects the trial court's advantage in observing witnesses and evaluating evidence in real-time.

Conversely, conclusions of law—how the law applies to facts—are reviewed de novo, meaning the appellate court applies its own legal judgment without deference to the trial court. This means that while the appeals court will likely defer to Judge Mehta's factual findings (that Google paid billions for defaults, that competitors faced barriers to entry, etc.), the court will independently evaluate legal conclusions (whether these facts constitute antitrust violations).

The Preliminary Injunction Pause Request

Google has simultaneously requested that implementation of remedies be paused pending appeal resolution. This request raises separate legal questions from the underlying appeal. To obtain a stay of remedies pending appeal, Google must demonstrate: (1) likelihood of success on appeal, (2) irreparable harm absent the stay, (3) balance of equities favoring the stay, and (4) public interest considerations.

Google's argument for irreparable harm rests on the premise that complying with remedies before appeal resolution could require permanent changes to business practices that would be difficult to unwind if Google prevails on appeal. For instance, if Google is forced to share its search index and competitors develop products based on that data, unwinding the remedy if Google wins the appeal would be extraordinarily complex. From Google's perspective, this represents irreparable harm.

The government counters that consumers are being harmed daily by Google's alleged monopoly conduct, and that preliminary stays prevent victims from obtaining relief. Additionally, the government argues that Google is unlikely to succeed on appeal given the strength of evidence, the quality of Judge Mehta's legal analysis, and precedent supporting antitrust enforcement against monopolistic firms.

Appellate Likely Outcomes and Scenarios

Predicting appellate outcomes is inherently uncertain, but several scenarios appear plausible. In the most favorable scenario for Google, the appeals court finds that the trial court erred in defining the relevant market too narrowly or in weighing evidence of Google's quality advantage. The appeals court could reverse the monopoly finding entirely, eliminating the need for any remedies.

More likely, however, the appeals court would affirm the trial court's factual findings regarding Google's dominance and the exclusionary nature of certain practices, but might modify the remedies as too broad or likely to cause more harm than benefit. The appeals court might eliminate the data-sharing requirement while maintaining restrictions on exclusive default arrangements. This "split the difference" outcome would affirm the government's case while accepting some of Google's critiques of specific remedies.

A third scenario involves the appeals court substantially affirming Judge Mehta's ruling, including both the monopoly finding and most of the remedies. This outcome would be most favorable to the government and would represent a significant loss for Google.

It's also possible that the case could be settled during the appeals process. Google faces uncertainty and disruption from prolonged litigation; the government faces uncertainty about appellate outcomes. Both parties might find settlement attractive, potentially involving Google agreeing to modify certain practices in exchange for the government dropping or reducing other remedies.

Implications for the Tech Industry and Competition Landscape

What This Means for Other Tech Companies

The antitrust case against Google has enormous implications for the broader tech industry. The ruling signals that even extraordinarily successful, dominant tech companies face antitrust liability if they achieve dominance through anticompetitive means rather than pure quality competition. This creates heightened legal risk for other major tech platforms that achieve significant market dominance through similar mechanisms.

Companies like Meta, Amazon, and Apple should be paying close attention to the legal theories the government deployed against Google and the factual findings that Judge Mehta made. Meta's dominance in social networking, Amazon's dominance in e-commerce and cloud services, and Apple's control of iOS and the App Store all involve aspects that share similarities with Google's search dominance: network effects, vertical integration with adjacent markets, control over distribution channels, and exclusive arrangements.

If the government successfully appealed and Google faces significant remedies, it would likely embolden regulators to pursue similar cases against other tech giants. Conversely, if Google prevails on appeal, it would discourage such enforcement and signal that dominant tech companies have greater latitude to defend their market positions through exclusionary practices.

Changes to Default Arrangements and Platform Competition

Regardless of the ultimate outcome, the case has already influenced how platforms approach default search arrangements. Browser makers and device manufacturers are reconsidering how prominently to feature Google and whether to negotiate exclusive arrangements. The mere existence of regulatory pressure has pushed companies toward greater competition in default placement, reducing the exclusivity that previously benefited Google exclusively.

If remedies are ultimately implemented, the changes to default arrangements could reshape search market dynamics substantially. Users who switch browsers or devices would encounter different default search options, potentially trying competing search engines that they'd otherwise never use. This exposure could shift user preferences if competitors offer genuinely different experiences—whether through privacy protection, AI-powered results, or specialized search functionality.

The Future of Search and Alternative Approaches

Beyond changes to defaults and data sharing, the antitrust case is accelerating transformation in search itself. The emergence of AI-powered search alternatives represents a fundamental shift in how users access information. Companies like OpenAI (with ChatGPT), Anthropic (with Claude), and others are developing alternatives to traditional web search that could reduce reliance on Google's index entirely.

If these AI-powered alternatives mature and gain user adoption, they could solve the antitrust problem through disruption rather than regulation. Users would switch to alternatives not because regulators forced it, but because the new technologies provided superior information access. From this perspective, the search market may be experiencing technological disruption that changes the competitive landscape regardless of antitrust outcomes.

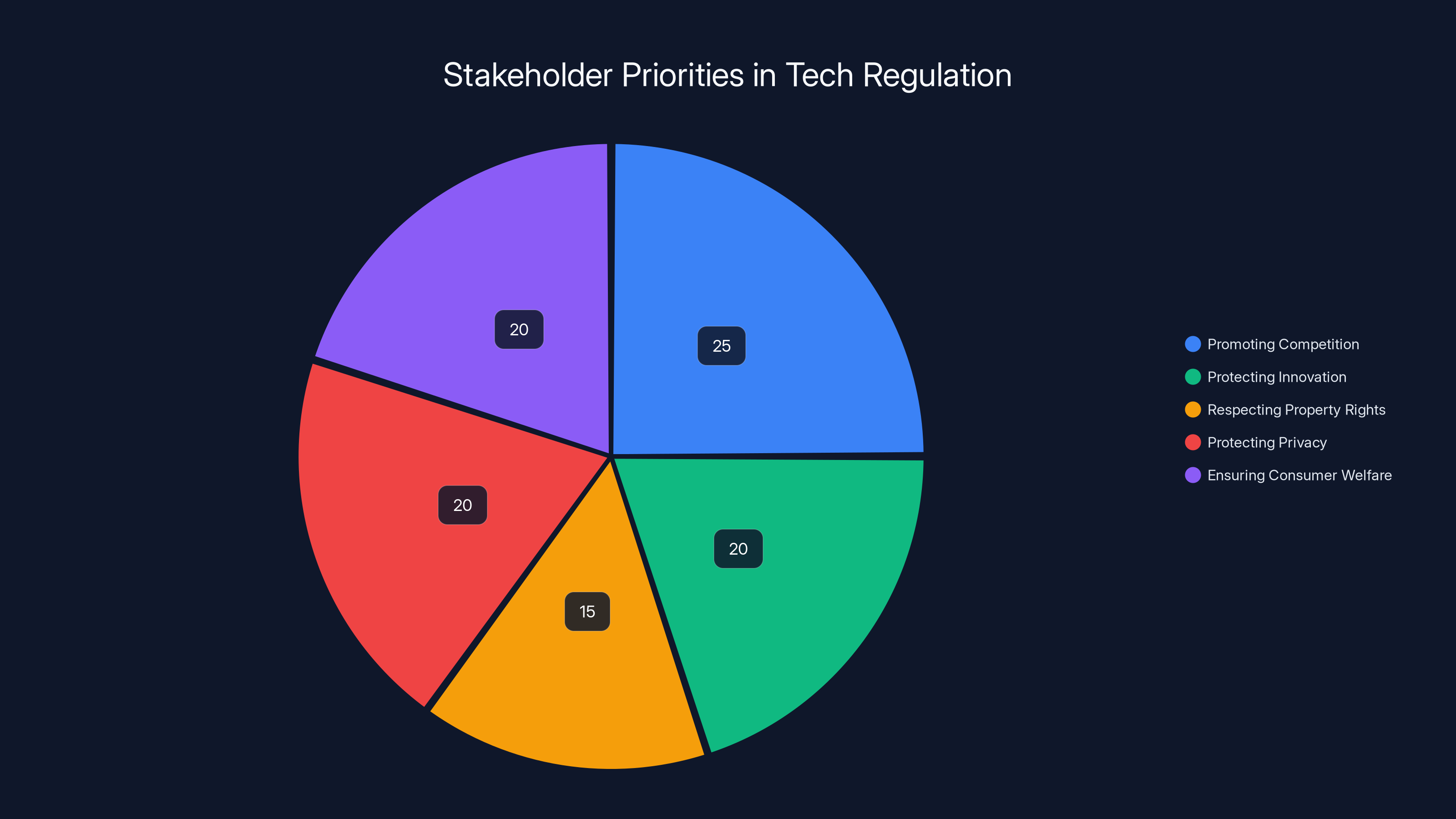

Estimated distribution shows a balanced focus among stakeholders, with promoting competition slightly prioritized. This reflects the complex nature of tech regulation debates. Estimated data.

Data Privacy and Concerns About Shared Information

The Privacy Arguments Google Advances

Google's most compelling argument against data-sharing remedies invokes privacy concerns. The company argues that sharing search data—even aggregated and anonymized data—raises significant privacy risks. Search queries can reveal extraordinarily sensitive information about users: health conditions, financial situations, personal relationships, religious beliefs, and countless other intimate details. The mere aggregation of such data, even when anonymized, could allow reidentification or enable tracking.

Google emphasizes that its privacy obligations to users would be complicated by requirements to share search data with competitors who might not maintain equivalent privacy standards. The company argues that forcing Google to act as a data intermediary could compromise user privacy and expose Google to liability if shared data is misused.

Counterarguments on Data Sharing and Safeguards

The government responds that privacy concerns are manageable through appropriate safeguards. The proposed remedy includes limitations on how shared data can be used, restrictions on reidentification attempts, and contractual obligations binding recipients to privacy standards. The government notes that regulated industries like healthcare and financial services regularly share data with appropriate privacy protections. Search is no exception.

Additionally, the government argues that Google's privacy arguments ring hollow given the company's extensive collection and use of user data for advertising and tracking. If Google is willing to collect, use, and monetize user search data for its own advertising business, privacy objections to sharing aggregated data seem inconsistent.

Practical Implementation Challenges

Regardless of legal arguments, implementing data-sharing requirements raises genuine practical challenges. Determining which data to share, in what format, under what restrictions, and with appropriate privacy safeguards requires careful technical and legal work. The government would need to develop detailed data-sharing protocols, and Google would need to engineer systems to comply.

These implementation challenges could extend the timeline for remedy implementation significantly. Google could argue that the complexity of safe, privacy-preserving data sharing requires phased implementation or that the challenges are so substantial that data sharing should be abandoned in favor of less intrusive remedies.

International Regulatory Precedent: Lessons from Europe and Other Jurisdictions

The European Union's Approach to Google Regulation

The European Union has pursued aggressive regulation of Google's practices through multiple mechanisms. The EU imposed a €2.4 billion fine in 2017 for search bias, a €1.5 billion fine in 2019 for illegal advertising practices, and a €5 billion fine in 2021 for location data collection. Rather than breaking up Google, the EU has imposed specific conduct restrictions and financial penalties.

Under the Digital Markets Act, the EU is requiring Google to make its search results more interoperable with competitors and to provide certain data access to rivals. These requirements share similarities with the U.S. proposals but have been implemented through regulatory legislation rather than antitrust litigation.

The EU's approach demonstrates that aggressive regulation of tech dominance doesn't necessarily require breaking up companies. Instead, it can involve conduct restrictions, data-sharing requirements, and interoperability mandates that level competitive playing fields without fundamentally altering company structures.

Regulatory Approaches in Asia and Emerging Markets

Other jurisdictions are developing their own approaches to tech regulation. India has imposed restrictions on Google's practices in search and advertising. South Korea has fined Google for anticompetitive app store practices. These diverse regulatory approaches suggest that Google faces global pressure to modify practices, regardless of the outcome in the U.S. antitrust case.

The international precedent cuts both ways in appellate arguments. Google argues that the U.S. shouldn't diverge dramatically from international approaches, suggesting measured remedies rather than radical changes. The government, conversely, argues that the U.S. should lead globally in protecting competition and innovation, and that measured approaches in other jurisdictions reflect different legal standards rather than wisdom about optimal remedies.

Developer and Entrepreneur Implications: New Opportunities and Risks

Opportunities for Competing Search Technologies

Developers and entrepreneurs interested in search technology face both opportunities and challenges created by the antitrust case. If remedies are implemented and data-sharing requirements take effect, competitors would gain access to search data that could substantially reduce the barriers to building competitive search engines. Instead of starting with zero data and zero users, competitors could leverage shared Google data to develop search capabilities, focusing innovation on differentiated features rather than rebuilding fundamental indexing and ranking infrastructure.

For specialized search applications—medical search, legal search, academic search, local search—the antitrust case opens opportunities for companies to develop focused search products that compete in specific domains. These vertical search engines don't need to compete with Google across all domains; instead, they can excel in narrow domains where specialized expertise and curated results provide superior value.

AI-powered search represents perhaps the most significant opportunity. Rather than building traditional web search engines, companies are developing AI-powered alternatives that synthesize information from multiple sources and provide natural language responses to queries. These approaches circumvent the need to build indexes and compete on traditional relevance ranking, instead competing on answer quality and user experience.

Regulatory and Business Risks for Startups

Conversely, startups in the search space face regulatory risks and uncertainty. If data-sharing requirements are imposed but then reversed on appeal, companies that invested in leveraging shared data might lose competitive advantages. Regulatory uncertainty itself discourages investment in search alternatives, as investors struggle to project returns given uncertain regulatory requirements.

Additionally, even if competitors gain access to Google's data, they still must compete with a company that has extraordinary resources and brand recognition. Gaining market share from Google requires not just data access but genuine differentiation—new capabilities that users prefer to Google's offerings. History shows that data access alone doesn't guarantee competitive success; execution, innovation, and user acquisition matter equally.

In 2020, Google dominated the search engine market with an estimated 92% share, dwarfing competitors like Bing and Yahoo. (Estimated data)

Business Model Implications: How Search Economics Could Change

The Advertising Model Under Threat

Google's search business operates on a fundamental economic model: users receive free search in exchange for Google's ability to target advertisements to users based on search context. This model generates approximately $170+ billion in annual revenue for Google, making it the company's primary profit engine. The antitrust case raises fundamental questions about whether this model will survive intact.

If competitors gain access to search data and distribution channels through remedies, they could develop business models that differ from Google's advertising-focused approach. A competitor might offer search with minimal advertising, generating revenue through premium subscriptions instead. Or a competitor might focus on privacy-protecting search that doesn't track users for advertising. These alternative business models could reduce advertising revenue in search overall.

Google would face pressure to modify its advertising practices in response to competition. If Google had been earning excess advertising revenues due to monopoly power, competitive pressure would force the company to reduce ad density or improve ad relevance, reducing per-query advertising revenue. This represents a genuine cost to Google of losing monopoly power.

Subscription and Premium Models

The antitrust case accelerates the trend toward alternative business models for search. Several competitors are experimenting with subscription models, offering ad-free search experiences or specialized search capabilities for paying users. If these models gain traction, search could evolve from pure free-with-advertising toward a mixed model where some users pay for premium experiences.

This shift would reduce search's role as a pure advertising channel and introduce diversity into search business models. From an innovation perspective, diverse business models could accelerate innovation by reducing dependence on advertising optimization and allowing companies to focus on search quality improvements that benefit users directly.

What's at Stake: The Broader Implications Beyond Google

The Precedent for Technology Regulation

Beyond Google itself, the antitrust case establishes precedent for how U.S. courts and regulators will treat dominant tech companies. A ruling that Google's conduct constitutes illegal monopoly maintenance signals that dominance through anticompetitive means violates antitrust law, even if the company's products are excellent. This precedent could expose other tech giants to similar challenges.

Conversely, if Google prevails on appeal, it would signal that tech dominance achieved through quality and network effects is lawful, and that dominance is difficult to establish in dynamic markets like technology. This outcome would provide comfort to other dominant tech companies and discourage further antitrust enforcement.

The Balance Between Competition and Innovation

Underlying the entire case is a fundamental tension in antitrust policy: balancing competition and innovation. Should antitrust law aggressively challenge dominant firms to promote competition, or should it give dominant firms latitude to innovate without disruptive legal challenges? This tension has animated antitrust debates for decades, and the Google case crystallizes it.

Google argues that aggressive enforcement discourages innovation by creating legal risk for successful companies. The company emphasizes its own innovation investments and suggests that diverting resources to comply with regulations rather than innovate represents a net loss for consumers. The government counters that monopoly power actually reduces innovation incentives and that competitive markets spur faster innovation.

This debate is ultimately empirical: does competition or dominance produce faster innovation? History offers examples supporting both views. In some markets, dominant companies like Microsoft and Intel drove rapid innovation. In others, competitive markets like smartphones saw faster innovation than previous monopolies in computing. The truth likely varies by industry and market conditions.

Timeline and Future Developments: What's Coming Next

The Appeals Process Timeline

Google's appeal will likely take 18-24 months to resolve through the appeals court process. The company will file briefs setting out its legal arguments; the government will file counter-briefs; there will likely be oral arguments before a three-judge appellate panel; the panel will issue a decision. After that, the losing party could request en banc review (review by the full court) or could appeal to the Supreme Court.

While the appeals process unfolds, the preliminary injunction question will be resolved separately. The court will decide whether to stay implementation of remedies pending appeal outcome. This decision will likely come within weeks or months, before the full appellate process completes.

Potential Settlement Negotiations

During the appeals process, it's possible that settlement negotiations could occur. Both parties face risks: Google faces uncertainty about appellate outcomes and the costs of compliance if it loses; the government faces uncertainty about whether appellate courts will affirm. Settlement would provide certainty for both parties.

A settlement might involve Google agreeing to modify certain practices—perhaps conceding on some data-sharing requirements or default arrangement restrictions—while avoiding the most disruptive remedies like forced browser divestiture. Such settlements have historical precedent in major antitrust cases.

International Regulatory Developments

As the U.S. case proceeds, international regulatory developments will continue separately. The EU's Digital Markets Act will likely impose additional obligations on Google. The UK, India, and other jurisdictions will continue investigating and regulating. These international developments will pressure Google to modify practices globally regardless of the outcome in the U.S. antitrust case.

Estimated data shows that Google's market share in a broader 'information access services' market is less dominant, with significant shares held by YouTube, Amazon, TikTok, and social media platforms.

Emerging Search Technologies and How They Intersect with the Antitrust Case

AI-Powered Search Alternatives

The most significant development in search technology in recent years has been the emergence of large language models and AI-powered search alternatives. ChatGPT, Claude, Perplexity, and other tools offer different approaches to information access than traditional web search. Rather than returning indexed web pages, these tools synthesize information into natural language responses.

These AI-powered alternatives could ultimately resolve the antitrust problems through disruption rather than regulation. If users prefer AI-powered search to traditional web search, competition from AI could reduce Google's market share dramatically, eliminating monopoly concerns. However, these alternatives are still emerging and may not achieve mass adoption.

Intriguingly, Google is also investing heavily in AI-powered search capabilities. The company is integrating AI capabilities into search results and developing products like Gemini that combine large language models with search. Google's ability to invest in these emerging technologies reflects its dominance and resources, but it also shows the company can adapt to technological change.

Vertical and Domain-Specific Search

Beyond general web search, specialized search for specific domains is becoming increasingly important. Medical search, legal search, academic search, and code search each have different requirements than general web search. Companies can build valuable search products by focusing on specific domains rather than competing head-to-head with Google in general search.

This vertical specialization could address antitrust concerns by reducing the importance of general web search dominance. If users access information through multiple specialized search tools, no single company's search product is essential. The market fragments into multiple specialized products, reducing any single player's market power.

Cost-Benefit Analysis: What Happens If Remedies Are Implemented

Costs to Google and Its Users

If remedies are fully implemented, Google would face substantial costs. The company would need to engineer data-sharing systems, potentially share proprietary algorithms and training data, restructure default arrangements, and unbundle certain products. These changes would require significant engineering investment and could harm Google's operational efficiency.

For Google users, the implications are more ambiguous. In theory, more competition in search could spur innovation and offer users better alternatives. In practice, if competing search engines simply license Google's data and index rather than building genuinely differentiated products, users might not see meaningful improvements. Additionally, if remedies discourage Google from investing in innovation (as the company argues), search quality could decline rather than improve.

Benefits to Competitors and Potential New Market Entrants

Direct benefits would accrue to Google's competitors. If Bing gains access to Google's search data, Bing could improve its search quality substantially with less investment. Smaller competitors and new entrants would face substantially lower barriers to entry with data access and requirement to feature competing search in default placements.

For consumers, the long-term benefits would depend on whether data access to competitors generates genuine innovation and product differentiation. If it does, competition could improve search experiences, reduce advertising load, or introduce privacy-protecting alternatives. If it doesn't, the remedy might simply redistribute search revenue to competitors without improving user experiences.

Broader Competitive and Innovation Effects

Beyond direct effects on search, remedies could have broader implications for how tech companies manage data and platform power. If data-sharing requirements apply to Google, could they apply to other dominant platforms? Could Amazon be forced to share marketplace data with competitors? Could Meta be forced to share social network data?

These broader questions create risk for the entire tech industry, increasing incentives for companies to regulate themselves proactively rather than face government intervention.

Comparative Platforms and Alternative Solutions for Teams

While the antitrust case unfolds and Google's future structure remains uncertain, organizations should be aware of emerging alternatives for search, automation, and information access. The regulatory environment and competitive dynamics are shifting, creating opportunities for differentiated solutions.

Emerging Search and Information Access Tools

Beyond traditional web search, platforms like Perplexity AI, Bing with AI integration, and specialized vertical search engines offer alternatives. Each serves different use cases: Perplexity focuses on synthesized answers rather than page results; Bing integrates Microsoft's AI capabilities; specialized search tools excel in specific domains.

For teams building applications or requiring specialized search capabilities, Runable offers AI-powered document generation and workflow automation that can complement search functionality. Runable's focus on AI agents for content generation means teams can automate information synthesis and presentation alongside search capabilities, creating comprehensive information access and processing workflows.

Teams evaluating search alternatives or automation platforms should consider multiple dimensions: search quality and relevance, privacy and data handling, integration with existing systems, cost structure, and available differentiation. Different tools excel in different contexts.

Workflow Automation and Data Processing Platforms

Beyond search itself, workflow automation platforms are gaining importance as organizations seek to process and leverage information efficiently. If search data becomes more widely available through antitrust remedies or competitive pressure, organizations will need platforms to process that data and extract value.

For teams needing automation without extensive custom development, Runable's AI agents for documents, reports, and slides provide cost-effective alternatives to building custom solutions. At $9/month, Runable makes automation accessible to startups and teams without enterprise budgets.

Alternatively, organizations could evaluate platforms like Make.com, Zapier, or Integromat for workflow automation; Elasticsearch or Meilisearch for search infrastructure; or custom solutions built on open-source tools. The choice depends on specific requirements, existing systems, and technical capabilities.

Legal Precedent and Antitrust Theory

Historical Context from Previous Tech Antitrust Cases

The Google case doesn't emerge in a vacuum; it builds on decades of antitrust jurisprudence and previous technology cases. The Microsoft antitrust case of the 1990s-2000s established important precedents about how courts analyze tech monopolies. Microsoft's dominance in operating systems, the court found, was leveraged to exclude competitors in browsers and other markets—a pattern Google's case echoes.

The key difference between Microsoft and Google is that Microsoft was eventually broken up (though the decision was later partially reversed), while the Google case hasn't resulted in divestiture. Instead, remedies focus on conduct restrictions and data sharing, reflecting different legal theories and judicial philosophies.

Shifting Antitrust Theory in Tech

Antitrust theory has evolved significantly from the "consumer welfare" focus that dominated the 1980s-2000s. Modern antitrust scholars emphasize that monopoly power can harm competition and innovation even when consumer prices remain low or when products are high-quality. This evolution in theory supports more aggressive enforcement against dominant tech companies, as the Google case demonstrates.

The shift reflects recognition that in digital markets, traditional price-based measures of consumer harm miss important harms to competition. Google search is free to consumers, but the company's monopoly power over search might reduce incentives for competitors to invest in alternatives, reducing future innovation even if current prices are favorable.

The Role of Network Effects in Antitrust Analysis

A key issue in the Google case is how courts should treat network effects and incumbent advantages in antitrust analysis. Network effects—where value increases as more people use a product—can create powerful incumbent advantages that make competition difficult. However, network effects can also result from genuine superiority and consumer preference rather than anticompetitive conduct.

The challenge for courts is distinguishing between: (1) dominance resulting from superiority and network effects (lawful), (2) dominance reinforced through anticompetitive conduct (unlawful), and (3) dominance resulting from a combination of both. Judge Mehta found that Google's dominance involves both network effects and superiority combined with exclusionary conduct. The appeals court will scrutinize whether this analysis correctly apportions causation between the lawful and unlawful elements.

Conclusion: Understanding the Stakes and Looking Forward

What the Google Antitrust Case Reveals About Tech Regulation

The Google search antitrust case reveals fundamental tensions in how democracies should regulate technology. The case involves competing values: promoting competition, protecting innovation incentives, respecting property rights in data and algorithms, protecting privacy, and ensuring consumer welfare. Different stakeholders prioritize these values differently, creating genuine disagreement about optimal regulatory approaches.

Google's argument—that dominance resulting from superior quality shouldn't face antitrust liability—has genuine merit from both economic and innovation perspectives. Companies should have incentives to invest in excellence, and antitrust law shouldn't punish success. However, the government's argument—that anticompetitive conduct can coexist with quality, and that removing barriers to competition would spur innovation—also has merit. History shows that competitive pressure drives innovation in many industries.

The resolution of these tensions through the appeals process will shape technology regulation for years to come. A Google victory would signal that antitrust law has limited reach over dominant tech companies. A government victory would signal that dominance through anticompetitive means faces legal liability regardless of product quality, potentially reshaping how tech companies structure businesses and manage competitive advantages.

The Broader Ecosystem Effects

Beyond Google specifically, the case influences how other tech companies manage dominance, how startups assess competitive opportunities, and how regulators evaluate tech markets. Every major tech company is watching this case and adjusting strategies accordingly. Companies are reconsidering exclusive arrangements, data practices, and product integration strategies in light of potential antitrust exposure.

For startups and entrepreneurs, the case creates both challenges and opportunities. The challenges include regulatory uncertainty and the possibility that competitors might gain advantages through forced data sharing or remedies. The opportunities include the potential for regulatory-spurred competition, the emergence of data-sharing requirements that reduce barriers to entry, and the prospect of AI-powered alternatives that circumvent traditional search dominance.

The Future of Search and Information Access

Regardless of antitrust outcomes, search and information access are undergoing fundamental transformation. AI-powered alternatives to traditional web search are emerging. Specialized vertical search tools are addressing specific domains where general search provides inadequate results. Privacy-focused search alternatives are gaining traction. The market is naturally evolving toward diversity and differentiation.

These transformations might ultimately resolve antitrust concerns better than regulatory remedies. If technology change reduces Google's market share and dominance organically, monopoly concerns evaporate. Conversely, if Google successfully adapts to technological change and maintains dominance even as the market transforms, that demonstrates persistent quality advantages that might deserve protection from aggressive antitrust enforcement.

The Google antitrust case is ultimately a crucial test of how regulatory systems can manage fast-moving technology markets. The outcomes will influence antitrust enforcement for years, will reshape competitive dynamics in search, and will demonstrate whether regulation or disruption provides better mechanisms for addressing tech dominance.

Key Takeaways for Different Stakeholders

For developers and entrepreneurs, the case creates opportunities to develop search alternatives, leverages emerging AI technologies, and potentially participate in more competitive markets if remedies are implemented. For teams evaluating automation and workflow solutions, the case underscores the importance of avoiding dependence on single dominant platforms while exploring alternatives like Runable for AI-powered automation at accessible price points ($9/month for critical productivity tools).

For regulators and policymakers, the case demonstrates that antitrust law can reach tech monopolies and that remedies beyond divestiture (like data sharing and conduct restrictions) are viable. For other tech companies, the case signals heightened antitrust risk for companies achieving dominance through exclusionary practices, encouraging proactive self-regulation.

For consumers, the case's ultimate resolution will determine search options, privacy protections, and the degree of competition in information access. The stakes extend far beyond Google, to fundamental questions about how regulatory systems manage innovation, competition, and technology-driven markets in the 21st century.

As appeals proceed and potential remedies face implementation, the tech industry, regulators, and consumers will all watch closely to see how courts balance competition, innovation, and consumer welfare in one of the most consequential antitrust cases of our era.

FAQ

What does it mean that Google was found to maintain a monopoly in web search?

It means a federal judge determined that Google controls approximately 90% of web search queries and that this dominance resulted from anticompetitive conduct rather than purely from superior quality. The judge found that Google systematically used exclusionary practices—like paying billions for default placement—to prevent competitors from gaining market share, rather than competing purely on search quality.

How did Google achieve and maintain its search monopoly?

Google's dominance stems from multiple reinforcing factors: network effects (more searches = better data = better algorithms = more users), securing default placement on browsers and devices through exclusive agreements (Google pays Apple an estimated $15-20 billion annually for Safari default status), and vertical integration with advertising services that generate profits supporting search investments. The combination of these factors created barriers to entry that competitors couldn't overcome through quality competition alone.

What are the proposed remedies in the antitrust ruling?

The judge's remedies include: (1) requiring Google to share search data and provide syndication services to competitors, (2) prohibiting exclusive default search agreements with browsers and device makers, (3) removing Chrome browser bundling from Android, and (4) restricting Google's ability to use proprietary search data to advantage its advertising products. The most controversial remedy is data sharing, which Google argues raises privacy concerns and discourages competitors from building proprietary search technology.

Why is Google appealing the antitrust ruling?

Google appeals for multiple reasons: the company disputes the monopoly finding, arguing that competition is intense and that dominance results from quality not exclusion; the company contends that remedies are inappropriate, likely to harm innovation, and to raise privacy concerns; and the company argues that the appeals court should overturn the trial court's legal conclusions even if its factual findings are upheld. Google simultaneously requested that remedy implementation be paused pending appeal resolution.

What happens if Google wins its appeal?

If the appeals court reverses the monopoly finding, the case ends and no remedies are imposed. If the court upholds the monopoly finding but reverses or modifies specific remedies, Google would avoid the most disruptive requirements (like data sharing) while potentially accepting limitations on exclusive default arrangements. A Google win would signal that antitrust law has limited reach against dominant tech companies and would encourage other tech companies that antitrust enforcement is unlikely.

What happens if the government prevails in the appeals court?

If the appeals court affirms the monopoly finding and remedies, Google would be required to implement data sharing, modify default arrangements, and restructure certain business practices. This would likely spur competition in search, potentially allowing Bing, Duck Duck Go, and new entrants to gain market share. For consumers and developers, it would increase search options and potentially reduce Google's ability to leverage search dominance into other markets. Google could further appeal to the Supreme Court, extending litigation for years.

What does the ruling mean for other tech companies like Meta, Apple, and Amazon?

The ruling establishes precedent that dominant tech companies can face antitrust liability for exclusionary conduct, even if their products are excellent. Other dominant companies face heightened scrutiny: Meta's social media dominance, Apple's control of iOS and the App Store, and Amazon's e-commerce and cloud dominance could all become antitrust targets. The ruling encourages regulators to pursue similar cases and discourages other dominant companies from engaging in exclusive arrangements and data leverage practices.

How could the antitrust case impact search innovation and consumer choice?

In theory, removing barriers to competition could spur innovation by allowing competitors to enter the market more easily. However, the effects depend on remedy implementation and market response. If competitors gain data access but simply license Google's index rather than building differentiated products, innovation might not improve. Conversely, if emerging AI-powered search alternatives (ChatGPT, Claude, Perplexity) disrupt traditional web search, competition might improve regardless of antitrust outcomes. Consumer choice would likely increase with more search options, though whether those options are genuinely superior depends on competitive execution.

What timeline should we expect for the appeals process and potential remedies?

Google's appeal will likely take 18-24 months to resolve through the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. A decision on staying remedies pending appeal could come within weeks or months. After the appeals court decides, the losing party might request en banc review or appeal to the Supreme Court, extending the timeline further. During this period, the preliminary injunction question will be resolved separately, determining whether remedies take effect immediately or wait for appeal resolution.

How does international regulatory action (EU, UK, India) affect the U.S. antitrust case?

International regulatory developments run parallel to the U.S. case but are independent. The EU's Digital Markets Act, UK investigations, and Indian enforcement all pressure Google to modify practices globally. These international actions demonstrate that regulatory pressure on Google is not unique to the U.S., which influences how U.S. courts view remedy appropriateness. However, international actions don't directly affect the U.S. appeal outcome, though they do show that regulatory precedent exists for alternatives to U.S. proposals.

What are the privacy implications of data-sharing requirements?

Google argues that sharing search data raises privacy concerns because search queries can reveal sensitive personal information. Even aggregated, anonymized data could potentially be reidentified or used for tracking. However, the government argues that privacy safeguards can manage these risks and that Google's privacy arguments are inconsistent with the company's other data collection and use practices. Practical implementation of safe data sharing will require careful technical design and legal contracts protecting recipient obligations.

Internal Linking Opportunities

- Antitrust law fundamentals and tech regulation framework

- How market dominance is defined and measured in digital markets

- Data privacy regulations and compliance requirements

- Competitive advantages in search and information access

- Alternative automation and productivity platforms for teams

This comprehensive guide examined Google's search antitrust case from every major angle: legal strategy, market dynamics, remedies, implications, and future directions. Whether the appeals court affirms, reverses, or modifies the ruling, this case will fundamentally shape technology regulation for years to come.

Related Articles

- Google Antitrust Lawsuits 2025: Publishers, Ad Tech, and Legal Impact

- Jensen Huang's Reality Check on AI: Why Practical Progress Matters More Than God AI Fears [2025]

- Shadow AI in 2025: Enterprise Control Crisis & Solutions

- OnePlus Foldable Phone 2026: Strategic Case for Market Re-entry

- Nvidia's AI Startup Investments 2025: Strategy, Impact & Alternatives

- [2025] Lucid Motors Faces Lawsuit Over Wrongful Termination