The Day a Billion-Device Network Started Crashing

Last year, something happened that sent shockwaves through the entire cybercriminal underworld. Not a Hollywood hack scene with dramatic music. Just Google quietly dropping legal documents, seizing domains, and updating their Play Protect system. By the time anyone realized what was happening, millions of devices had vanished from one of the internet's largest criminal infrastructure networks.

The target was IPIDEA, a residential proxy service so massive and so entrenched in cybercrime that over 550 separate threat groups depended on it in a single week. We're talking about groups linked to China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea. All of them. Using the same network. For espionage, credential theft, botnet control, and breaching enterprise systems.

This wasn't a law enforcement raid you'd see on the news. It was something more strategic, more surgical, and frankly, more effective. Google's Threat Intelligence Group documented how they systematically dismantled one of the largest criminal proxy networks in existence, and what they learned tells us something important about the future of cybersecurity, the sophistication of criminal infrastructure, and whether Big Tech companies can actually fight back against organized cybercrime.

Let me break down what happened, why it matters, and what comes next.

What Is a Residential Proxy Network, Really?

Okay, so here's the thing. A residential proxy sounds boring and technical. And sure, it is. But the implications? Those are terrifying.

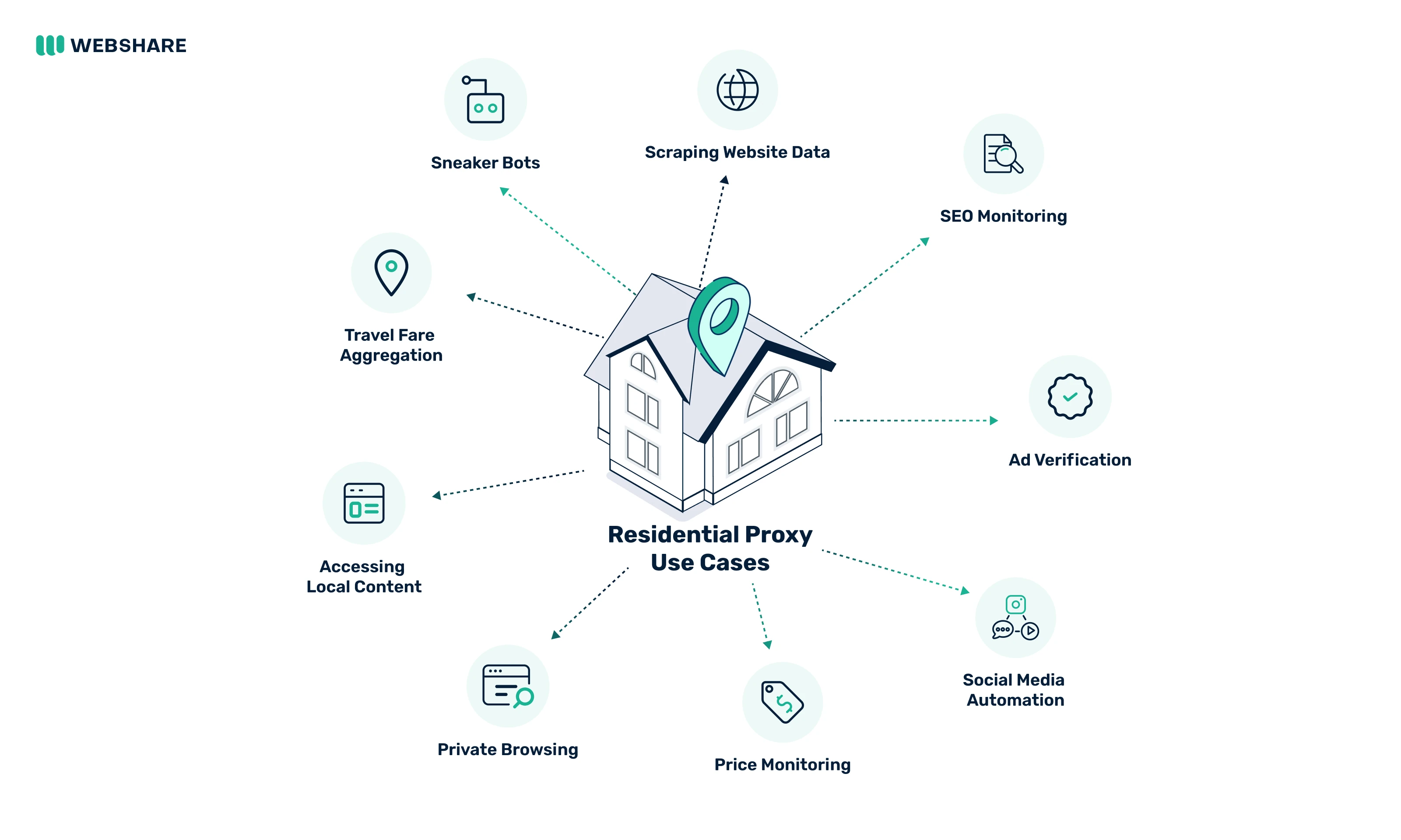

Think of a regular proxy like a middleman. You send a request, the proxy intercepts it, modifies it slightly, and sends it on your behalf. The server on the other end sees the proxy's address, not yours. That's useful for a lot of legitimate reasons. Testing websites across different locations. Checking how your ads appear in different countries. Scraping public data for research.

But residential proxies are different. They don't use corporate IP addresses. They use IP addresses that belong to actual residential connections, ISP-assigned addresses issued to real people's homes and devices. And here's where it gets dark. Those devices are mostly there without the owners knowing about it.

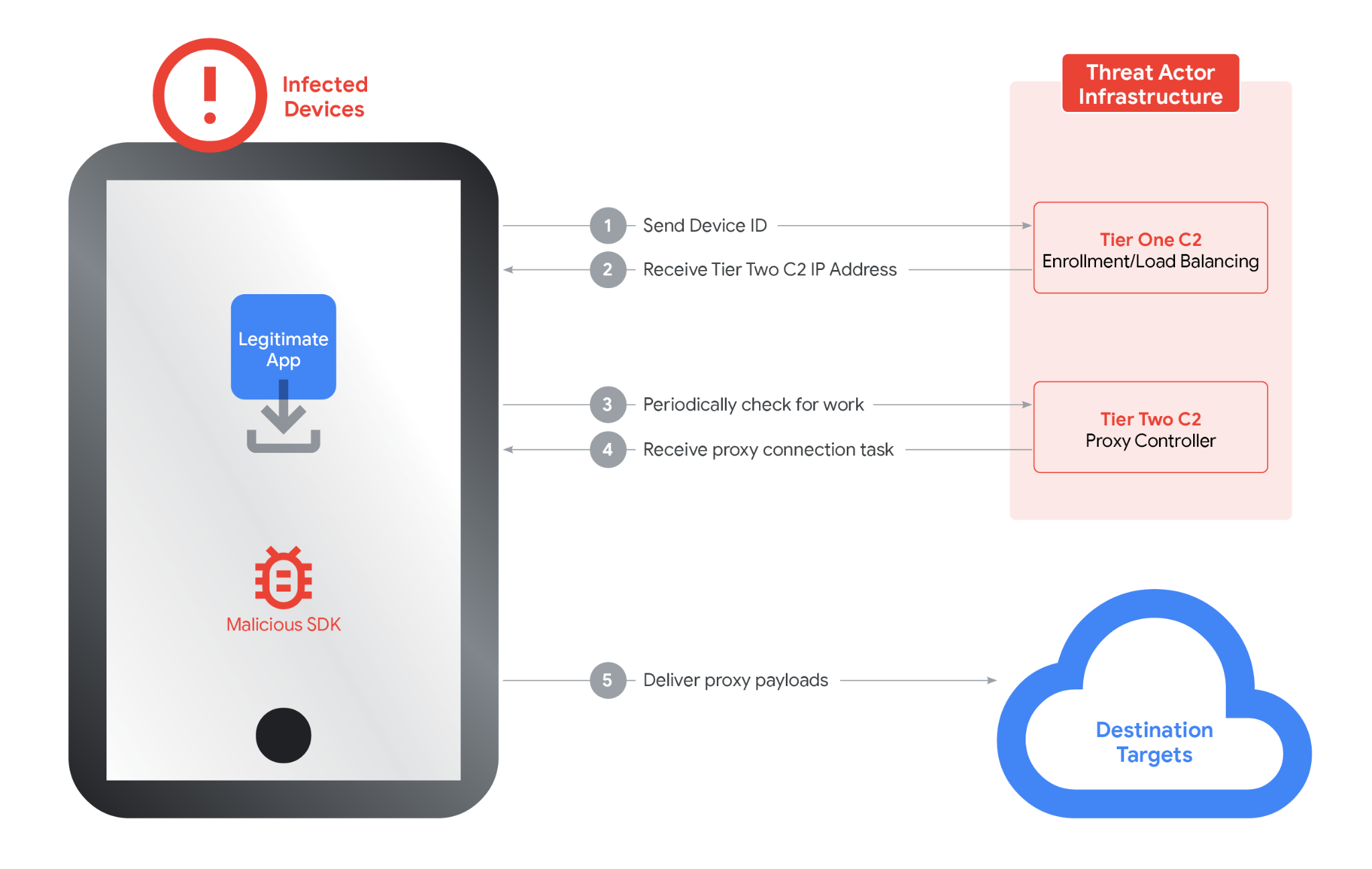

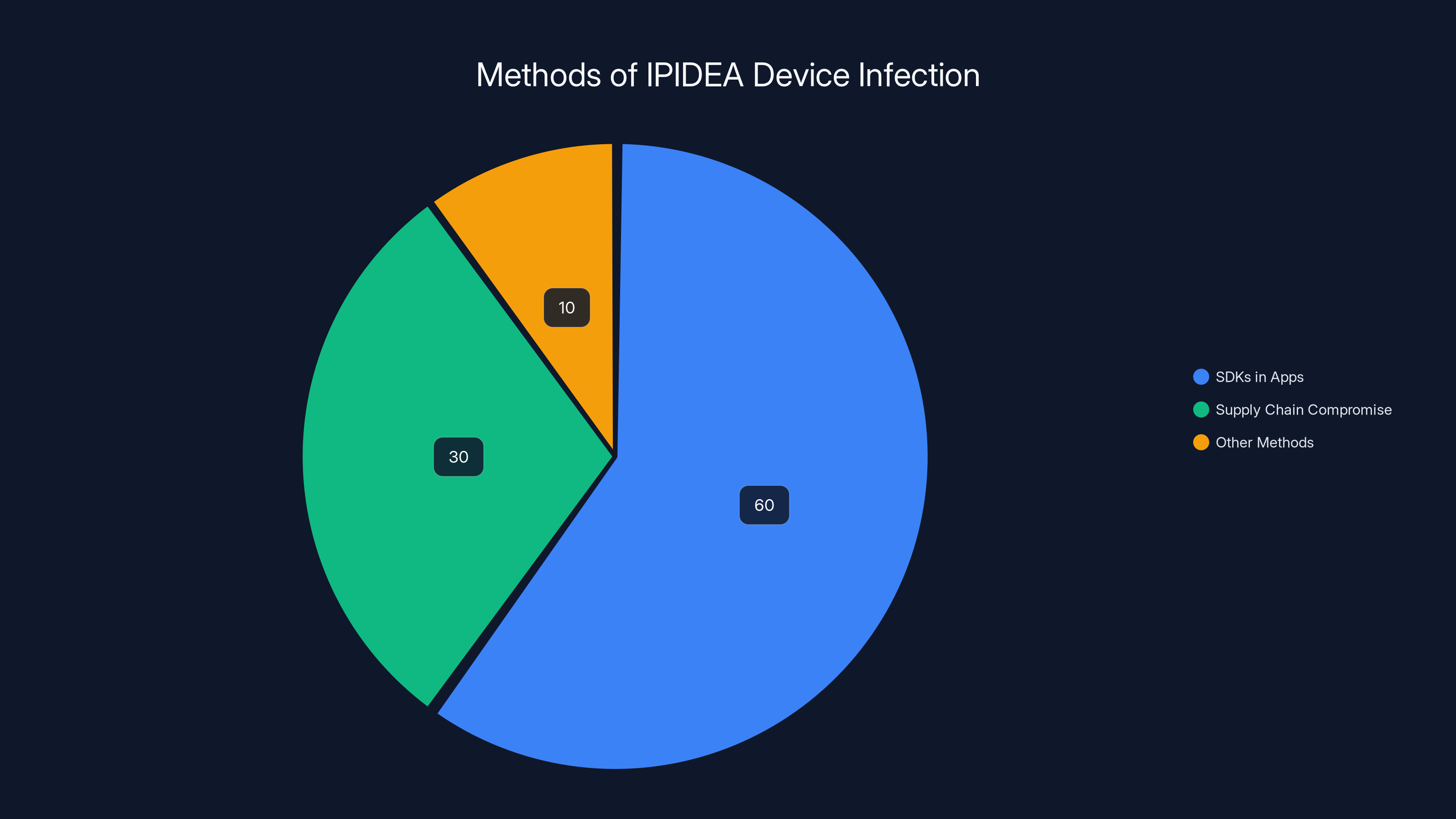

IPIDEA did this through a clever, almost cynical mechanism. They created software development kits (SDKs) marketed to app developers as a way to "monetize your application." The pitch was simple: embed our code, earn money. App developers, especially smaller ones trying to make money on free apps, said yes. They embedded the SDK. And suddenly, every user of that app became part of a massive proxy network without ever consenting to it.

This is where it gets really deceptive. The users never installed a proxy app. They weren't running a service they knew about. They downloaded what appeared to be a legitimate app like a mobile game, a productivity tool, or a utility. Buried in the back-end code was this SDK that quietly started routing internet traffic through IPIDEA's network. The device became a proxy. The user had no idea.

In some cases, the network was even more insidious. Supply chain compromise. IPIDEA apparently worked with hardware manufacturers in certain regions to have the malware preinstalled on Android TVs and set-top boxes right from the factory. People bought what they thought was a normal device and got a proxy asset included in the hardware.

The scale was stunning. We're talking millions of devices. Android phones, Windows PCs, routers, Io T devices, set-top boxes. All of them quietly contributing bandwidth to one of the most powerful criminal infrastructure networks on the planet.

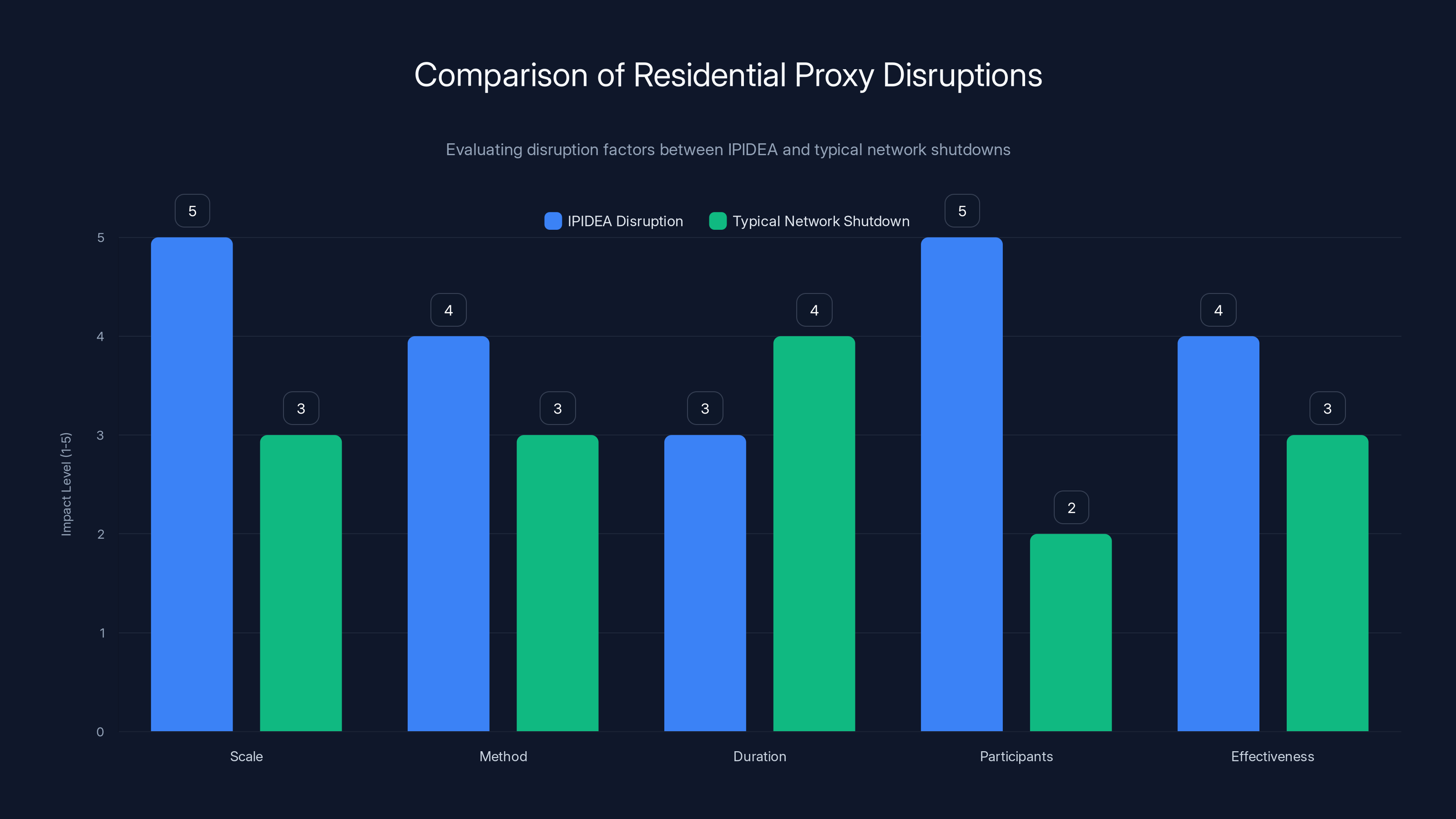

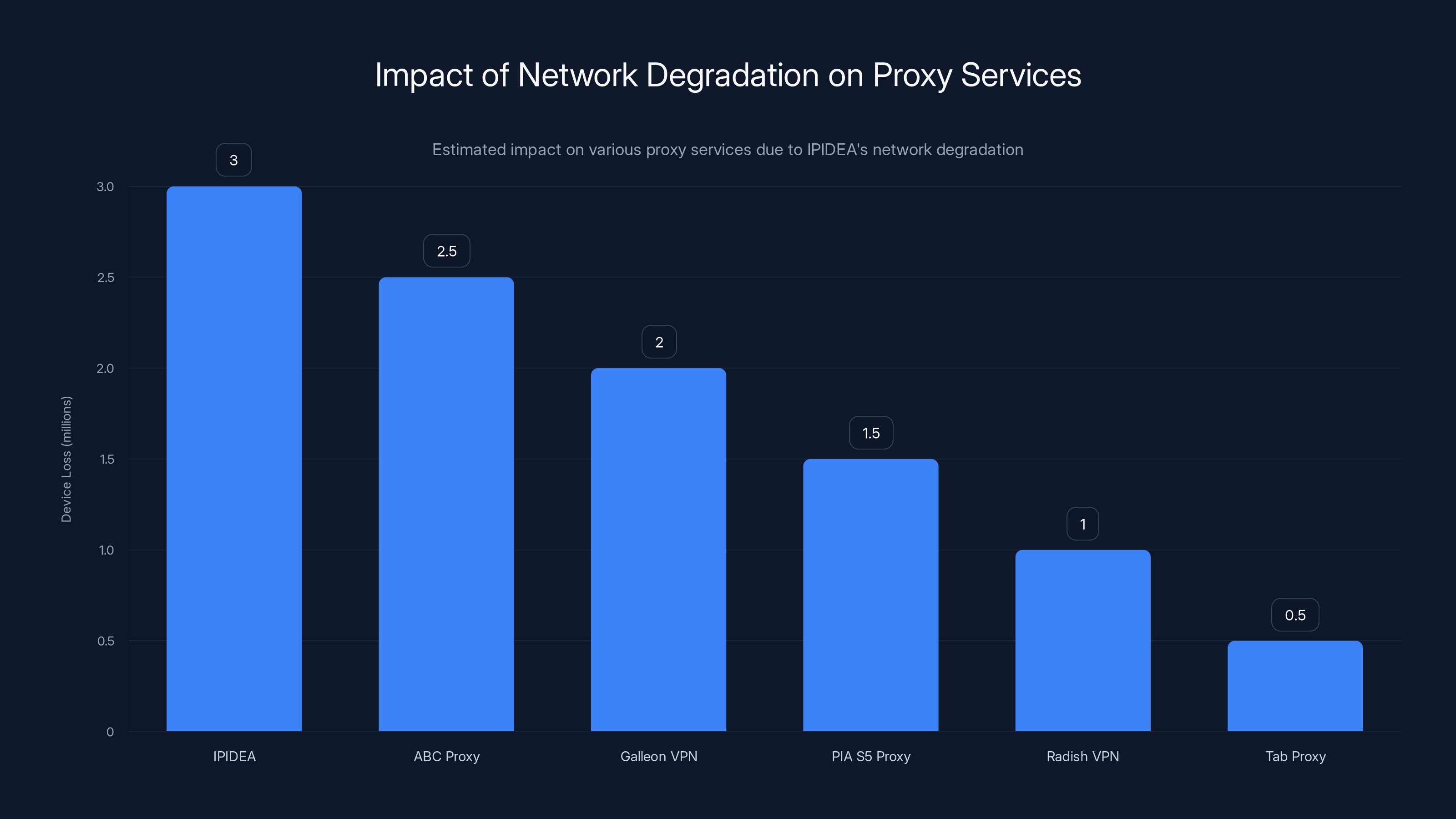

IPIDEA disruptions show higher scale and participant involvement compared to typical network shutdowns, indicating a more comprehensive approach. Estimated data based on qualitative descriptions.

How IPIDEA Built a Criminal Megastructure

IPIDEA didn't just happen. It was engineered. And it was engineered by people who understood infrastructure at a level that's honestly impressive, in a deeply unsettling way.

First, the reach. IPIDEA offered access to proxy servers from dozens of countries. The researchers documented multiple geographic endpoints. This matters because when a threat actor wants to appear to be coming from a specific country or region, residential proxies are perfect. They're not datacenter IPs that look suspicious. They're real residential addresses. Banks and security systems are trained to trust residential IPs. That's by design. Nobody thinks a residential connection is going to be a malicious actor.

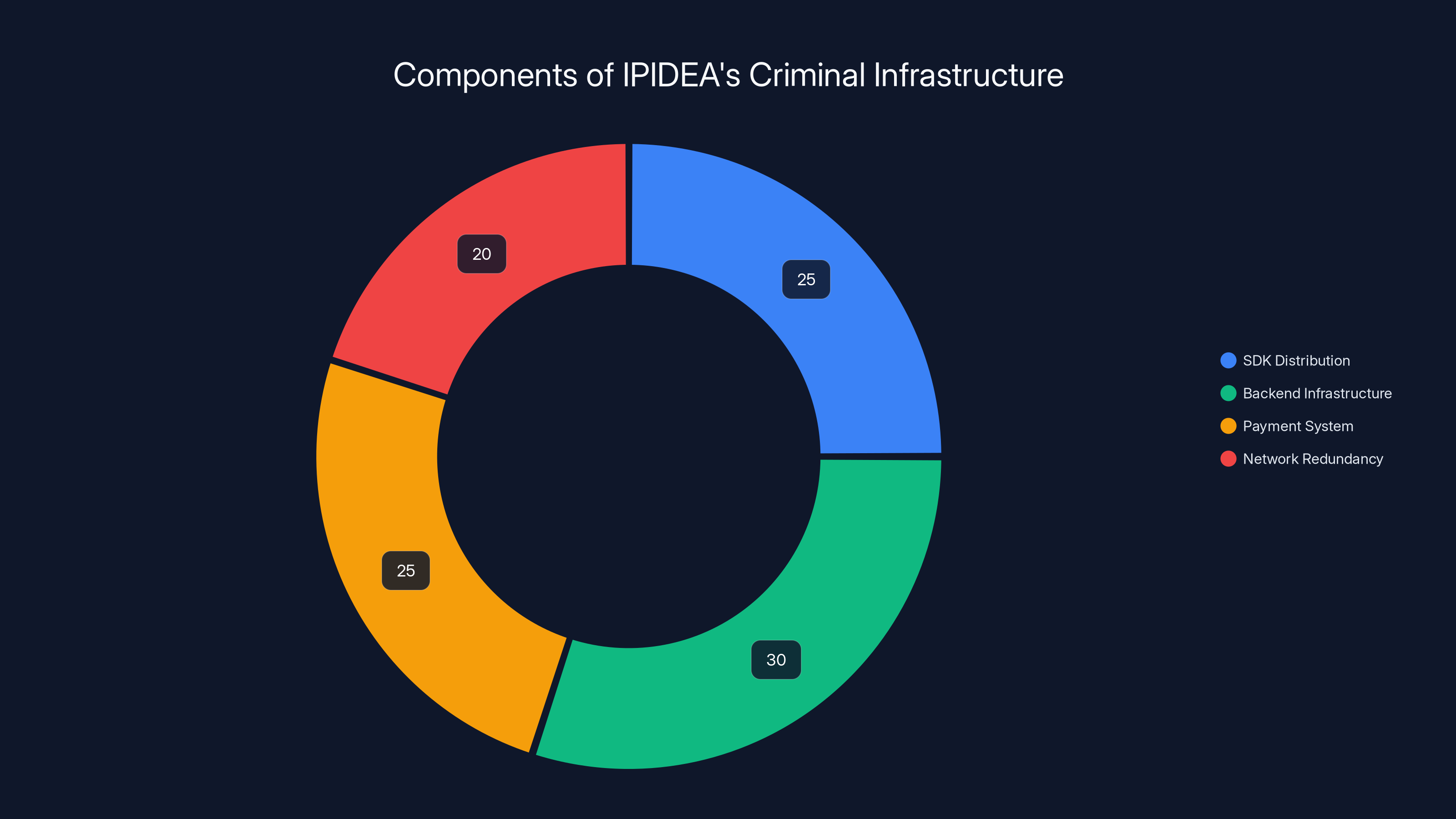

Second, the business model. IPIDEA operated what's called a "reseller" network. They didn't just sell access directly to threat groups. They sold access to other proxy service providers, who then sold access to their own customers, who then might have sold access down the chain further. It's a multi-layer business where the top gets plausible deniability. IPIDEA could claim, "We don't control how people use our network." Technically true. Morally? That's another story.

Third, the brands. This is the clever part. IPIDEA didn't operate under one obvious name. Google's researchers linked IPIDEA to multiple well-known proxy and VPN services. ABC Proxy. Galleon VPN. PIA S5 Proxy. Radish VPN. Tab Proxy. Some of these had customer bases that included businesses who thought they were using a legitimate service from an independent company. But they were all using the same backend. Same infrastructure. Same millions of hijacked devices.

The reseller model created a false sense of legitimacy. Someone could download Galleon VPN thinking it's a standalone service offering privacy. In reality, they're just renting access to IPIDEA's stolen network of residential devices. The criminals who bought access got something they couldn't build themselves. Real residential IPs in dozens of countries. The ability to appear as though millions of different people were making requests.

The sheer audacity of this model shouldn't be overlooked. These weren't sophisticated zero-day hacks. They were relying on something simpler and more powerful: human nature. App developers want to monetize. Users don't read permission dialogs carefully. Hardware manufacturers in certain countries operate in gray regulatory zones. All of these things exist. IPIDEA just exploited them at scale.

The 550 Threat Groups: What Were They Actually Doing?

Now, here's the question everyone should ask. What exactly were 550+ threat groups doing with millions of residential proxy IPs? The answer is probably worse than you think.

Espionage. This is the core of what state-sponsored threat actors do. They use proxies to probe government networks, steal intelligence, and mask their origin. If a group from China wants to attack a think tank in the United States, they'll route the traffic through residential proxies in dozen countries. The defenders see requests from Ohio, then Singapore, then Denmark, then Finland. The attribution becomes nearly impossible. The actual attacker stays invisible.

Credential attacks. This is where the criminal money actually is. Threat groups use residential proxies to test stolen passwords and usernames at scale. A residential IP attempting to log into a Gmail account from Ohio looks normal. A datacenter IP doing the same thing gets flagged immediately. With IPIDEA, attackers could perform credential stuffing attacks using thousands of different IP addresses, each one appearing to be a normal person in a real location. The number of accounts that could be cracked multiplies exponentially.

Botnet command and control. Botnets are networks of compromised computers that execute commands from a central authority. If you want to hide the botnet controller's location, residential proxies help. Instead of connecting directly, the botnet connects through proxies. Layer after layer of obfuscation.

Cloud and enterprise breaches. This is where it gets really serious. Many companies implement security rules that say, "No connection allowed from known datacenter IPs." But they trust residential connections. An attacker using IPIDEA could appear to be connecting from an employee's home network. From that trust, they could escalate into cloud environments, steal data, plant ransomware, establish persistence, and maintain access for months.

Google specifically mentioned that IPIDEA proxies were used for "access to compromised cloud and enterprise environments". That's diplomatic language for: "Major companies got breached because we trusted residential IPs, and the attackers knew that."

The geographic distribution of the threat groups is worth noting. Groups with links to China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea all operated on the same network. This reveals something important about global cybercrime: it's not fragmented into isolated regional ecosystems. It's integrated. A Russian group might rent proxies to attack a US bank, while an Iranian group uses the same infrastructure to probe European targets. IPIDEA was the central nervous system for global organized cybercrime.

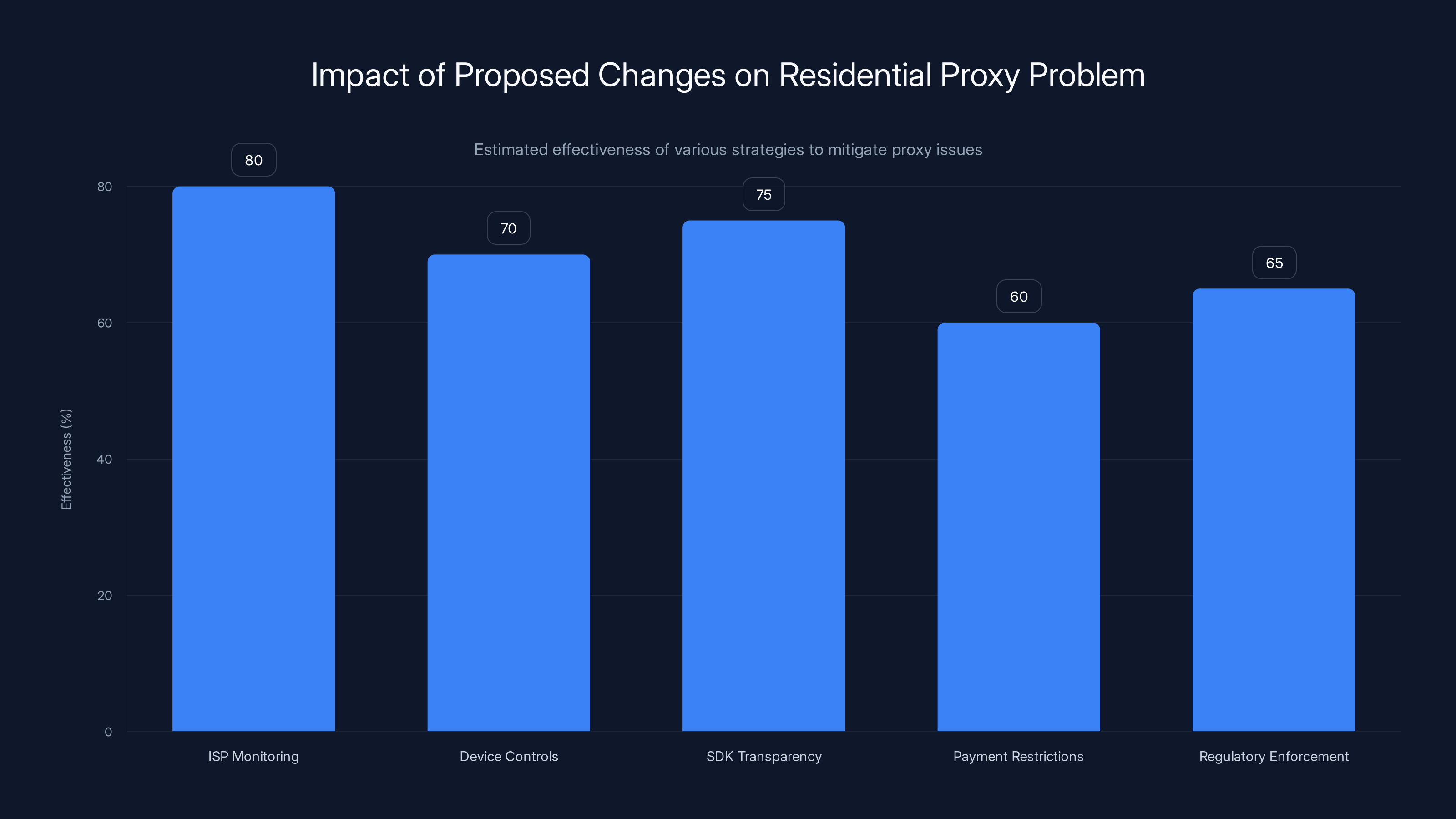

Estimated data shows ISP-level monitoring as the most effective strategy, potentially reducing proxy usage by 80%. Other measures also contribute significantly to mitigation.

Google's Three-Part Takedown Strategy

Now for the interesting part. How do you kill a network this big? You can't arrest the operators if they're in countries that won't extradite. You can't shut it down by attacking the servers because it's distributed. So what do you do?

Google executed three parallel actions, and the combination was devastating.

Part One: Legal Action and Domain Seizure

This sounds simple, but it's more effective than people realize. IPIDEA needed domains for command and control. They needed marketing pages where potential resellers could sign up. They needed infrastructure that had to be registered somewhere, controlled from somewhere, accessible from somewhere.

Google worked with law enforcement and took legal action to seize these domains. Command and control infrastructure fell offline. The ability to manage the botnet, update configurations, and coordinate with resellers disappeared. It's like cutting the nervous system out of the network.

Domain seizures happen all the time in cybercrime investigations, and most of the time, they're minor annoyances. Criminals just use new domains. But when you combine it with the other two actions, it becomes significant.

Part Two: Industry Intelligence Sharing and Law Enforcement Coordination

Google didn't handle this alone. They documented their findings and shared technical intelligence with industry partners and law enforcement agencies. This is important because it means the disruption wasn't isolated. Other security companies could recognize IPIDEA infrastructure and block it. Law enforcement in multiple countries could take parallel action.

Think of it like this: Google found the network and mapped it. But they made sure everyone else got the map too. Banks could implement blocks on their networks. ISPs could identify and remediate compromised devices. Threat intelligence vendors could push updates to their customers.

This intelligence sharing is how modern cybersecurity defense actually works. No single company can fight organized cybercrime alone. But if Google documents the threat and shares it widely, the entire ecosystem improves.

Part Three: Google Play Protect Updates

This is where the disruption became truly effective. Google updated Google Play Protect, their mobile security system, to automatically identify and remove apps containing IPIDEA SDKs. Any Android device running Google Play Protect that had these apps installed would get notified and the apps would be removed.

Consider the scale impact here. Android has over 3 billion active devices. When Google Play Protect pushes an update, it reaches a massive installed base. Not every device, not immediately, but broadly and comprehensively.

Apps that had embedded the IPIDEA SDK started disappearing from devices. The pool of hijacked devices available to the proxy network contracted sharply. Every app uninstalled, every infected device removed, reduced the available bandwidth and IP addresses IPIDEA could offer.

This is the action that reduced the device pool by millions. Not fancy hacking. Not zero-days. Just Google's security infrastructure identifying problematic code and removing it at scale.

The Damage: Network Degradation and Cascading Impact

Google was explicit about the impact: "We believe our actions have caused significant degradation of IPIDEA's proxy network and business operations, reducing the available pool of devices for the proxy operators by millions."

But here's the crucial part: "Because proxy operators share pools of devices using reseller agreements, we believe these actions may have downstream impact across affiliated entities."

Translate that: When IPIDEA lost millions of devices, so did ABC Proxy, Galleon VPN, PIA S5 Proxy, Radish VPN, and Tab Proxy. The reseller network meant that the disruption cascaded. A threat group that depended on Galleon VPN didn't know they were actually using IPIDEA. When their service degraded, they had to find alternatives. The criminal ecosystem had to reorganize.

This is actually more important than it might seem. Criminal infrastructure has inertia. Groups use tools they know work. They have relationships with service providers. They've built workflows around specific capabilities. Disrupting that forces them to adapt, rebuild, and move. And during that period of disruption, visibility increases and attribution becomes easier.

The network lost capability across multiple dimensions. Geographic coverage narrowed. Bandwidth decreased. Quality of service degraded. Criminals who were comfortable routing traffic through millions of residential IPs suddenly had to compete for access to a smaller pool. Pricing likely increased. Service reliability definitely decreased.

Was IPIDEA completely eliminated? No. Google was careful not to claim that. They said the network experienced "significant degradation." It's still operating, but smaller, less capable, and more visible.

The Infrastructure They Left Behind: Technical Artifacts

Google's research documented the technical infrastructure IPIDEA built, and it's worth understanding because it reveals how sophisticated criminal infrastructure has become.

The SDK distribution method was highly optimized. IPIDEA didn't distribute SDKs directly to millions of developers. They worked through developer networks, affiliate programs, and marketing channels. Developers who wanted to monetize their apps could integrate the SDK with minimal friction.

Once embedded, the SDK was designed to be invisible. It consumed minimal battery. It didn't create network traffic bursts that would trigger usage warnings. It didn't request suspicious permissions. It just quietly included itself in the normal data flows of the app.

The backend infrastructure was distributed. Command and control servers existed in multiple countries. The proxy network had redundancy. If one endpoint failed, traffic would route through others. This is actually good infrastructure design being used for criminal purposes.

The payment system was sophisticated. Criminals could pay in cryptocurrency. The money was laundered through multiple layers. Profit could be distributed to the app developers who embedded the SDKs, the resellers, and the operators.

This is what separates IPIDEA from amateur ransomware operations or script-kiddie attacks. This was professional infrastructure. Built by people who understood systems architecture, marketing, payment processing, and international money laundering.

SDKs in apps accounted for an estimated 60% of IPIDEA infections, with supply chain compromise contributing 30%. Estimated data.

Why Residential Proxies Matter in the Broader Criminal Economy

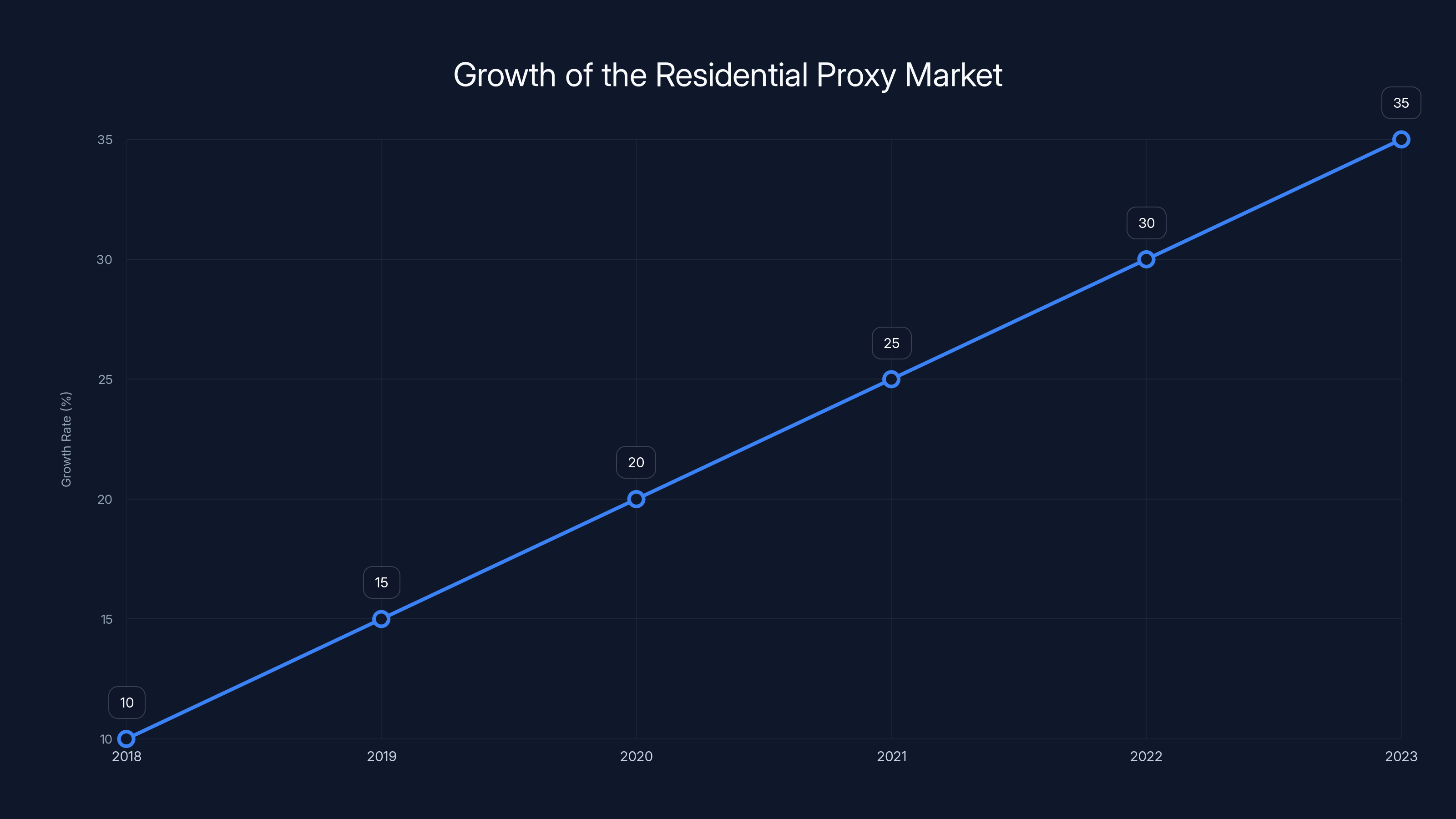

IPIDEA is one network. But the residential proxy market itself is described by Google as a "fast-growing gray market that continues to enable large-scale cybercrime." That's important language. They're not saying the market will shrink. They're saying it's growing, and it's fundamentally gray.

Why? Because residential proxies have legitimate uses. Website testing. Ad verification. Localization testing. Legitimate companies use them. But the same tool is perfect for cybercrime because it's nearly impossible to distinguish legitimate use from criminal use when both are using the same infrastructure.

The market is growing because the price is dropping. Cloud computing made attacks cheaper. More developers exist in countries with less regulatory oversight. The supply of people willing to embed SDKs for profit is larger than it's ever been. And the demand from criminals is insatiable.

Google's disruption of IPIDEA probably won't significantly slow the growth of the residential proxy market. Some users will migrate to other networks. Some will find alternative infrastructure. The criminal economy is large enough and profitable enough that new proxy services will emerge to fill the void.

But the disruption does something else. It establishes precedent. It shows that major tech companies are willing to take action. It demonstrates that infrastructure can be dismantled with legal action, intelligence sharing, and good security engineering. It raises the cost of operating a major proxy network because you now have to account for the possibility that Google might decide to take you down.

The Cascade of Implications: What Happens Next?

When one of the largest criminal infrastructure networks gets significantly degraded, it creates ripple effects across the entire cybercrime ecosystem.

First, immediate migration. Threat groups that depended on IPIDEA proxies have to find alternatives. Some will move to other residential proxy services. Others might try to build their own proxy networks. This creates opportunities for detection and response during the migration window.

Second, price increases. There's now less capacity in the market. Basic economics. With reduced supply of residential proxy access, the price goes up. This increases the cost of credential stuffing attacks, large-scale phishing campaigns, and botnet operations. Not enough to stop them, but enough to make them less attractive relative to other approaches.

Third, visibility into reseller networks. Google documented how multiple branded proxy services were actually IPIDEA backends. That information is now public and in law enforcement hands. Other proxy networks that operate similarly are likely to be scrutinized more carefully. If you're running a proxy service, you now know that using a reseller model and maintaining shared infrastructure makes you more visible and more targetable.

Fourth, developer awareness. App developers who unknowingly embedded IPIDEA SDKs are now aware that this can happen. Some will be more careful. Some will audit their dependencies. Some will avoid SDKs from sketchy monetization networks. Not all of them, but some. And that raises the cost of acquiring new devices for future proxy networks.

Fifth, supply chain scrutiny. The discovery that hardware manufacturers were preloading malware will likely trigger audits and investigations in the countries where this was happening. If it leads to charges and enforcement action, it becomes riskier for manufacturers to participate in similar schemes.

None of this destroys the residential proxy market. None of it stops cybercrime. But all of it increases friction. All of it makes operations more difficult and more expensive.

The Regulatory Angle: What This Means for Tech Policy

This action also has implications for how governments think about technology regulation and corporate responsibility.

Google didn't wait for government to act. They couldn't, probably. Government moves slowly. International coordination is hard. By the time law enforcement could build a case and get all the jurisdictions to agree, IPIDEA would have evolved and moved on.

Instead, Google used their own enforcement tools. They controlled the Play Store and Play Protect, so they could remove malicious apps. They had the legal resources to seize domains. They had relationships with industry partners to share intelligence.

This raises a question that policymakers are grappling with: Should tech companies be allowed to take unilateral action against criminal infrastructure? On one hand, yes. It works. It's faster. It stops real harm. On the other hand, who controls what's considered criminal infrastructure? Who decides which networks to disrupt? These are enforcement powers that are increasingly held by private companies rather than governments.

The answer from companies like Google is usually: "We work with law enforcement and follow legal procedures." And they did, to some degree. But the reality is also that Google had the power to disrupt IPIDEA because they control massive distribution and infrastructure platforms. Governments don't have that power. Tech companies do.

This is going to be a major policy question in the next few years. How much enforcement power should private companies have? What are the appropriate checks and balances? How do you prevent abuse while still allowing companies to defend their platforms?

For now, the IPIDEA disruption is generally being seen as a win. The infrastructure was criminal. The action was effective. But the precedent is significant.

IPIDEA's infrastructure was evenly distributed across SDK distribution, backend systems, and payment processing, with a focus on network redundancy. Estimated data.

Parallels and Comparisons: IPIDEA in Context

IPIDEA isn't the first major criminal infrastructure network to get disrupted. There's a history here worth understanding.

Compare it to the botnet takedowns from years past. Conficker. Zeus. Mirai. In each case, security researchers documented the network, law enforcement coordinated action, and at some point, the network got knocked offline or severely degraded. But in most of these cases, the operators still escaped. They still had resources. They still operated new botnets.

Compare it to the darknet market takedowns. Silk Road. Alpha Bay. Wall Street Market. These were targeted at specific criminal markets, not infrastructure. When one market got shut down, operators moved to another.

IPIDEA is different because it's infrastructure. It's not selling drugs or stolen data. It's selling network access. It's foundational. Taking it down affects the entire ecosystem that depends on it.

The closest parallel might be to ISP-level infrastructure disruptions. When providers like Bulletproof Hosting got shut down in the mid-2010s, entire criminal operations had to relocate. The difference is that IPIDEA operated at a larger scale and with more distributed infrastructure.

The Shadow Network: What Replaces IPIDEA?

Here's the uncomfortable truth. IPIDEA was big, but it wasn't unique. Other residential proxy services exist. Some are probably larger. Some operate in countries where Google has even less leverage.

The market for residential proxies is global. India has proxy services. Nigeria has proxy services. Russia has proxy services. China has proxy services. The moment IPIDEA experienced serious degradation, demand from criminals shifted elsewhere.

This isn't to say the disruption was pointless. It wasn't. It raised costs. It disrupted operations. It forced migrations. All of those things matter. But it's important to be realistic. The residential proxy market didn't shrink because IPIDEA got disrupted. It probably kept growing because the fundamental economic incentives are still there.

What might actually change the economics of the market is more fundamental. If residential ISPs began implementing monitoring that made it obvious when a device was being used as a proxy. If device manufacturers required explicit opt-in for proxy usage. If app stores increased scrutiny of SDKs more broadly. If payment processors refused to process proxy service transactions. Any of these would change the game.

But absent those kind of systemic changes, disruptions of individual proxy networks are tactical wins in a strategic struggle that the defenders are currently losing.

Lessons for Enterprise Security Teams

For people actually defending networks and systems, what does the IPIDEA takedown teach us?

First, SDK audits are critical. Any third-party code you integrate into your application is a potential vector for compromise. You need to know what SDKs you're using, from where they come, and what they're actually doing. This is the supply chain security problem at the application level.

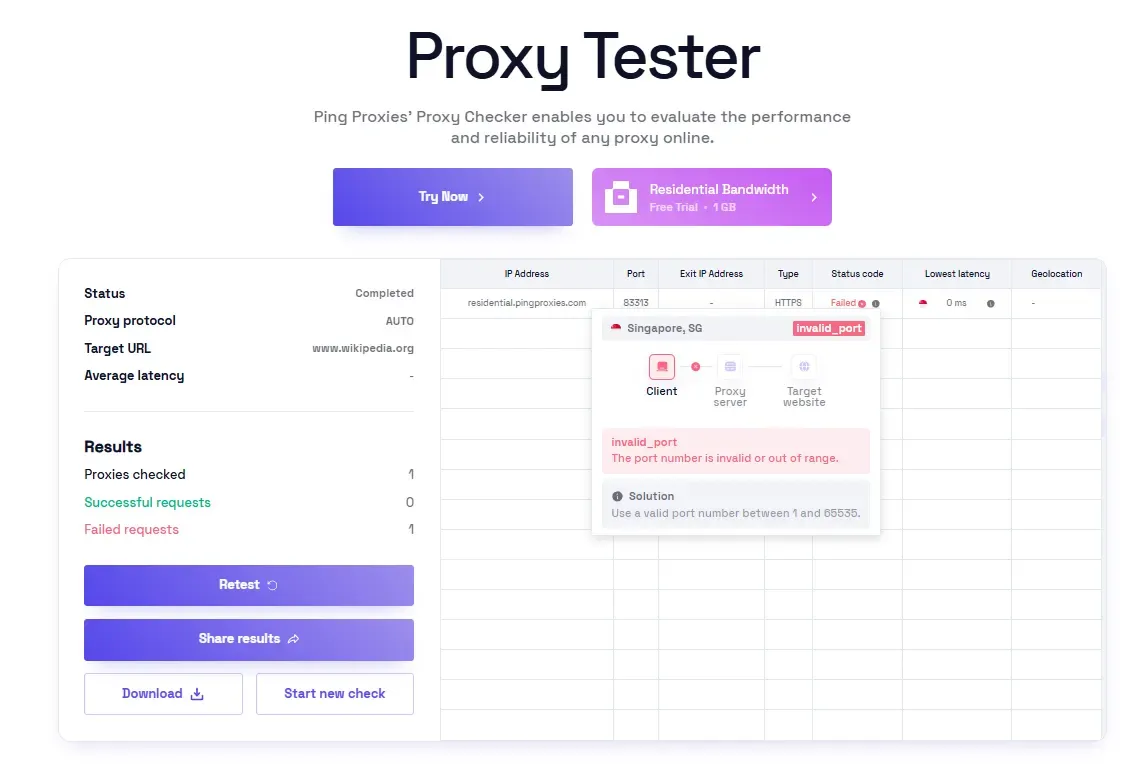

Second, residential IP behavior is worth monitoring. If you see access from residential IPs in countries that don't make sense for your business, that's worth investigating. It might be innocent. It might be an attacker using a proxy. But it's a signal worth paying attention to.

Third, the proxy threat is evolving. Proxies used to be a known problem with known detection methods. Increasingly, they're becoming harder to distinguish from legitimate traffic. Your security architecture needs to account for that.

Fourth, threat intelligence sharing works. When Google published their findings about IPIDEA, security teams everywhere could update their detection. The attack surface changed. This is why intelligence sharing from major security companies matters.

Fifth, the attack economy has changed. Credential attacks using residential proxies at scale are now cheaper and easier than they've ever been. This is going to drive massive upticks in large-scale attacks against your systems. If you're not prepared for that threat, you should be.

The residential proxy market is experiencing rapid growth, estimated to increase by 5% annually due to decreasing costs and rising demand from both legitimate and criminal uses. Estimated data.

The Detection Problem: Can We Stop This From Happening Again?

One of the challenges with residential proxy-based attacks is that they're incredibly hard to detect. From the perspective of the target system, the attacker looks like a legitimate user in a legitimate location.

Credential stuffing attacks that route through residential proxies look like normal login attempts from various locations. Bank fraud that originates from a residential proxy looks like it's coming from a normal person's home. Enterprise network penetration that uses residential proxies to appear to be coming from an employee's home network is nearly impossible to distinguish from legitimate VPN access.

The detection has to happen at different layers. Your network security team might notice unusual access patterns. Your threat intelligence might reveal IPs associated with known proxy providers. Your user behavior analytics might flag impossible travel or unusual access sequences. Your app security might detect anomalous API calls. But no single layer catches it all.

This is why the Google approach of removing IPIDEA SDKs at the source is so valuable. It eliminates the problem before it even manifests as an attack. You can't use residential proxies for an attack if the residential proxies don't exist.

Future Defense: What Should Change?

Looking forward, several things need to happen if we're going to actually address the residential proxy problem at scale.

ISP-level monitoring and remediation. Internet service providers are the obvious place to detect when a consumer device is being used as a proxy. They see the traffic patterns. They understand the usage anomalies. If ISPs were required or incentivized to implement monitoring that detects proxy usage and notifies customers, the supply of available devices would drop dramatically. This is technically feasible. It's just politically difficult because ISPs don't want the liability.

Device manufacturer controls. Operating systems could implement tighter controls on what software is allowed to do regarding network traffic routing. Apple, Google, and Microsoft could make it much harder for malicious SDKs to operate transparently in the background. This is partially happening, but not comprehensively.

SDK transparency and verification. App stores could require that SDKs be independently verified and that their network behavior be disclosed to users. Instead of hidden SDKs doing unknown things, you'd have transparent, verifiable SDKs doing disclosed things. This would basically eliminate the stealth proxy injection vector.

Payment processing restrictions. Processor networks like Visa, Mastercard, and banking systems could refuse to process transactions related to proxy services. This would increase the difficulty of monetizing the proxy business. It's not impossible to work around, but it adds friction.

Regulatory enforcement. Governments could prosecute individuals and organizations operating large-scale proxy networks as facilitators of cybercrime. This is already happening in some cases, but it's not consistent or comprehensive globally.

None of these are complete solutions. Criminals are creative. If one vector closes, they'll find another. But they would increase the cost and complexity of operating at scale, which is the actual goal.

The Geopolitical Dimension: State-Sponsored Implications

One aspect that deserves more attention is the state-sponsored angle. Google documented that threat groups with links to China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea all used IPIDEA. That's interesting because it suggests a level of infrastructure sharing that crosses traditional geopolitical boundaries.

In some cases, this might be deliberate neutrality on IPIDEA's part. They don't care about the politics. They care about the money. But it could also represent a pragmatic understanding among different state intelligence services that certain infrastructure benefits everyone.

Alternatively, it could represent a gap in state-sponsored attack capability. Instead of building and maintaining their own proxy infrastructure, state actors are renting from criminal enterprises. This is actually pretty common. State-sponsored attackers often use commercial malware, rented botnets, and purchased exploits alongside their own custom tools.

The implication is that when you disrupt infrastructure like IPIDEA, you're disrupting not just criminal groups, but also state-sponsored operations. Google's action had geopolitical consequences even if those weren't the primary intent.

This also explains why the action was coordinated with law enforcement. Taking down a network used by state-sponsored threat groups requires government approval and coordination. Google didn't do this unilaterally. They got buy-in from U. S. government agencies, likely the FBI and other intelligence services, before they acted.

Estimated data shows significant device loss across multiple proxy services due to network degradation, with IPIDEA experiencing the highest impact.

What Happens to the Users?

One interesting question that gets less attention: What happened to the millions of users whose devices were infected with IPIDEA proxies?

Most of them probably never knew. Their phones were part of the network. They saw no change. A notification came through their Play Store saying an app was being removed for security reasons. They tapped OK without reading it. And that was that.

For them, the Google disruption was entirely invisible. A potential security threat was removed from their device automatically. From their perspective, nothing happened.

But that's also the reality of most cybersecurity. The best defensive actions are the ones that users never notice. The breach that's prevented before it happens. The malware that's removed before it does damage. The infrastructure that's disrupted before it affects you.

In some cases, though, users might notice degraded service if they were using an app intentionally to access proxy services. Some proportion of IPIDEA users were actually using it deliberately for legitimate purposes like accessing region-restricted content or testing. For them, the disruption meant they had to find alternative services.

This is where the legitimate versus criminal use distinction gets blurry. The same infrastructure that enables state-sponsored espionage also enables someone in a restrictive country to access uncensored information. You can't just neutrally disable proxy access without affecting both use cases.

The Bigger Picture: What Does This Mean for Cybersecurity?

Zoom out for a moment. What does the IPIDEA takedown tell us about the state of cybersecurity and cybercrime in the mid-2020s?

First, it tells us that major tech companies have moved into enforcement. They're not just defending their platforms anymore. They're actively disrupting criminal infrastructure using legal action, intelligence sharing, and technical measures. This is a significant shift from even a decade ago.

Second, it tells us that criminal infrastructure is increasingly sophisticated and distributed. IPIDEA wasn't some amateur operation. It was professional, scalable, and resilient. The people who built it understood systems architecture and business operations. This is the new normal for large-scale cybercrime.

Third, it tells us that disruption is possible, but not permanent. You can slow down criminal operations, but you can't stop them completely. The best you can do is raise costs and reduce efficiency. As long as the economic incentives exist, people will keep building criminal infrastructure.

Fourth, it tells us that the defense is going to be increasingly technical and increasingly corporate-led. Governments are slower and less nimble. Tech companies have the tools, the data, and the expertise to move faster. This creates both opportunities and risks. It's good that infrastructure gets disrupted. It's concerning that private companies have this much enforcement power.

Fifth, it tells us that we're going to see more of these actions. Google has demonstrated that it's feasible and effective. Other companies will follow. We should expect a future where major platform companies routinely take action against criminal infrastructure.

Practical Defense: What Organizations Should Do

If you work in IT security or infrastructure, here's what you should actually do in response to threats like IPIDEA.

First, update your threat intelligence. Get the indicators of compromise from Google's research. That means the IP ranges used by IPIDEA, the command-and-control domains, the app signatures. Add these to your blocking and detection systems.

Second, audit your supply chain. What third-party SDKs are you using? Do you know what they're doing? Have you reviewed them recently? This is especially important if you're a mobile app developer or if your applications use significant amounts of third-party code.

Third, implement residential proxy detection. Your network monitoring should flag when connections come from known residential proxy IP ranges. These aren't connections from legitimate users in your customer base. They're attacks.

Fourth, segment your network. If you can't completely prevent attacks through residential proxies, you can at least limit the damage. Access from a residential proxy should trigger additional verification. It shouldn't automatically grant access to sensitive systems.

Fifth, share intelligence. If you discover that you've been attacked through a specific proxy service, share that information with your industry peers. This is how the defense works. Everyone contributes information, and everyone benefits from the collective knowledge.

The Continuing Threat: Residential Proxies Aren't Going Away

One final point that's worth emphasizing. Even though IPIDEA got seriously disrupted, even though Google took decisive action, the residential proxy threat isn't going away. If anything, it's accelerating.

New proxy services are already emerging to fill the gap. The market is growing, not shrinking. The economic incentives are stronger than ever. The demand from criminals continues to increase because credential-based attacks are profitable and relatively low-risk compared to other cybercriminal activity.

What changes is the specific infrastructure. IPIDEA is degraded. But something like IPIDEA will exist next year, and the year after. The fight against proxy-enabled cybercrime isn't a war with a victory. It's an ongoing defensive effort where the goal is to make attacks more difficult and more expensive.

For organizations, this means treating the residential proxy threat as permanent. Build defenses with the assumption that attackers have access to residential proxies. Design systems with the understanding that traffic from residential IPs can't be trusted implicitly. Implement multiple layers of defense so that when proxies are used in attacks, they're caught by one of those layers.

The work Google did matters. It disrupted one of the largest criminal networks in existence. It raised costs for attackers. It generated intelligence that will help defenders for years. But it didn't solve the problem. The problem is structural and it's going to require structural solutions across the entire internet ecosystem.

FAQ

What is a residential proxy network?

A residential proxy network is a collection of internet-connected devices (phones, computers, routers, Io T devices) whose internet connections are routed through a proxy service. The key distinction from datacenter proxies is that residential proxies use IP addresses assigned to real homes and consumer devices, making them appear as legitimate users rather than corporate infrastructure. IPIDEA operated one of the largest such networks, with millions of compromised devices worldwide.

How did IPIDEA infect devices without user knowledge?

IPIDEA primarily infected devices through software development kits (SDKs) that they marketed to app developers as monetization tools. When developers embedded these SDKs into their applications, users who downloaded the apps unknowingly added proxy functionality to their devices. Additionally, IPIDEA engaged in supply chain compromise by having malware pre-installed on certain Android TVs and set-top boxes at the manufacturing level.

Why are residential proxies so dangerous for cybersecurity?

Residential proxies are dangerous because they allow attackers to hide their true origin while appearing to be legitimate users in real locations. Security systems are trained to trust residential IP addresses because they typically come from normal people, not attackers. This makes residential proxies ideal for credential stuffing attacks, accessing restricted systems that implement geographic restrictions, and maintaining persistent access to enterprise networks while evading detection.

What specific actions did Google take to disrupt IPIDEA?

Google implemented three parallel actions: First, they took legal action to seize domains used for command-and-control and marketing. Second, they shared technical intelligence with industry partners and law enforcement agencies. Third, they updated Google Play Protect to automatically detect and remove apps containing IPIDEA SDKs from Android devices. The combination of these actions reduced IPIDEA's available device pool by millions.

What were the 550 threat groups using IPIDEA for?

The threat groups used IPIDEA for multiple criminal purposes including state-sponsored espionage, large-scale credential stuffing attacks, botnet command-and-control operations, and breaching enterprise and cloud environments. Groups linked to China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea all relied on IPIDEA infrastructure, indicating it was serving both independent cybercriminals and state-sponsored threat actors simultaneously.

How effective was Google's disruption of IPIDEA?

Google's actions caused significant degradation of IPIDEA's operations, reducing available proxy devices by millions and degrading the network's capability to support attacks. However, the threat actors and IPIDEA operators themselves were not completely eliminated, and the residential proxy market remains a growing "gray market" that continues to enable cybercrime. The disruption raised costs and forced attackers to migrate to alternative infrastructure, but didn't solve the underlying problem.

What should organizations do to protect against residential proxy attacks?

Organizations should implement multiple defensive layers including monitoring for connections from known residential proxy IP ranges, implementing additional verification for suspicious access patterns, auditing third-party SDKs in their applications, segmenting networks to limit damage from compromised access, and maintaining updated threat intelligence about current proxy threats. Additionally, implementing behavioral analysis and impossible-travel detection can help identify attacks using residential proxies.

Why does the residential proxy market continue to grow despite disruptions like IPIDEA?

The market continues growing because residential proxies have legitimate uses for businesses (website testing, ad verification, localization testing) and for users in restrictive countries seeking access to uncensored content. Simultaneously, the criminal demand for proxies remains extremely high, and the economics continue to reward new proxy services. The cost of operating a proxy network is relatively low, and the potential profit is substantial, creating strong incentives for new operators to emerge.

What is the difference between IPIDEA and legitimate proxy services?

The fundamental difference is consent and disclosure. Legitimate proxy services are explicitly installed and used by people who know they're using a proxy. Users of legitimate services make an informed choice and understand what's happening with their connection. IPIDEA infected devices without user knowledge or consent through deceptive SDK distribution, making users unwitting participants in a criminal infrastructure network without their awareness or agreement.

Could this happen again with a different proxy service?

Yes, absolutely. The IPIDEA disruption was a major victory, but the underlying business model and technical approach remains viable. New proxy services with similar or improved designs will likely emerge. The residential proxy market is growing, and the criminal demand shows no signs of diminishing. Future disruptions will require continued vigilance, intelligence sharing, and coordinated action from tech platforms, law enforcement, and security researchers.

TL; DR

- Google disrupted IPIDEA, one of the largest residential proxy networks, affecting over 550 threat groups linked to China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea

- The disruption strategy combined legal domain seizures, industry intelligence sharing, and Google Play Protect app removal, reducing the proxy device pool by millions

- IPIDEA operated through deception, infecting devices via hidden SDKs in apps and pre-installed malware on hardware, creating a network without user consent

- The threats were severe, including state-sponsored espionage, credential attacks, botnet control, and enterprise network breaches, all enabled by residential proxies that appeared legitimate

- The residential proxy market remains a growing threat despite this disruption, continuing to enable large-scale cybercrime through multiple successor services and operators

- Organizations must implement multi-layer defenses including proxy detection, supply chain audits, network segmentation, and behavioral analysis to protect against similar threats

Comparison of Residential Proxy Disruptions

| Factor | IPIDEA Disruption | Typical Network Shutdown | Long-Term Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scale | Millions of devices, 550+ threat groups | Thousands to hundreds of thousands of devices | Market consolidation, migration to alternatives |

| Method | Legal action, intelligence sharing, app removal | Law enforcement seizures or technical takedown | Temporary disruption, rebuilding within months |

| Duration | Ongoing degradation, not complete elimination | Usually 6-12 months before resurgence | Recurring threat cycles with new infrastructure |

| Participants | Major tech companies + law enforcement + industry | Government agencies only | Expanded defense coordination |

| Effectiveness | Significant short-term impact, strategic implications | Limited without complementary actions | Indicates future disruption models |

Key Takeaways

- Google disrupted IPIDEA, a network infecting millions of devices through hidden SDKs, affecting 550+ threat groups linked to multiple nations

- The three-pronged approach combined legal domain seizures, intelligence sharing, and Play Protect app removal to reduce the device pool by millions

- IPIDEA enabled state-sponsored espionage, credential attacks, botnet control, and enterprise breaches by providing legitimate-appearing residential IP addresses

- The residential proxy market remains a growing criminal infrastructure threat that will continue to enable attacks despite this major disruption

- Organizations must implement multi-layer defenses including proxy detection, SDK audits, network segmentation, and behavioral analysis to counter these threats

Related Articles

- I Tested a VPN for 24 Hours. Here's What Actually Happened [2025]

- 800,000 Telnet Servers Exposed: Complete Security Guide [2025]

- Nike Data Breach: What We Know About the 1.4TB WorldLeaks Hack [2025]

- Are VPNs Really Safe? Security Factors to Consider [2025]

- Iran's Digital Isolation: Why VPNs May Not Survive This Crackdown [2025]

- Best VPN Services 2025: Tested, Reviewed, and Ranked [2025]

![Google's War on Residential Proxies: How IPIDEA's Network Collapsed [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/google-s-war-on-residential-proxies-how-ipidea-s-network-col/image-1-1769697542626.jpg)