800,000 Telnet Servers Exposed: Complete Security Guide [2025]

Imagine discovering that nearly a million devices on your network are broadcasting their location to attackers like a beacon in the night. That's essentially what happened when security researchers at Shadowserver Foundation uncovered the sheer scale of exposed Telnet servers worldwide. We're talking about 800,000 IP addresses running Telnet services that shouldn't be publicly accessible. And worse? Attackers started probing these systems within a day of the vulnerability being patched.

Here's the thing that keeps security professionals awake at night: most of these exposed endpoints are legacy systems. They're running outdated versions of GNU Inet Utils (some versions are over a decade old), they're sitting on network edges that nobody's monitoring, and they're completely unaware of the threat targeting them right now.

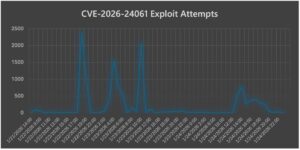

This isn't some theoretical vulnerability that requires a specific skill set to exploit. The CVE-2026-24061 flaw is rated 9.8 out of 10 in severity—one of the highest possible ratings. It's an authentication bypass, which means attackers can skip right past login screens and land directly on your system with root-level access. And they're not just connecting for reconnaissance. Early data shows threat actors are actively attempting to deploy Python malware to compromised devices.

What makes this particularly urgent is that the patch exists. It's been released. But patching infrastructure isn't simple, especially when you're dealing with thousands of legacy systems spread across your enterprise, or when those systems are embedded in industrial equipment that can't easily be updated. Some organizations have already moved to block Telnet entirely. Others are scrambling to figure out which of their devices are even running it.

This article walks you through everything you need to know about this vulnerability, what it means for your organization, and exactly what steps you should take—whether you're managing a data center, an ISP, industrial control systems, or just trying to harden your network infrastructure. We'll break down the technical details, show you how to find vulnerable systems, and give you a practical roadmap for remediation.

TL; DR

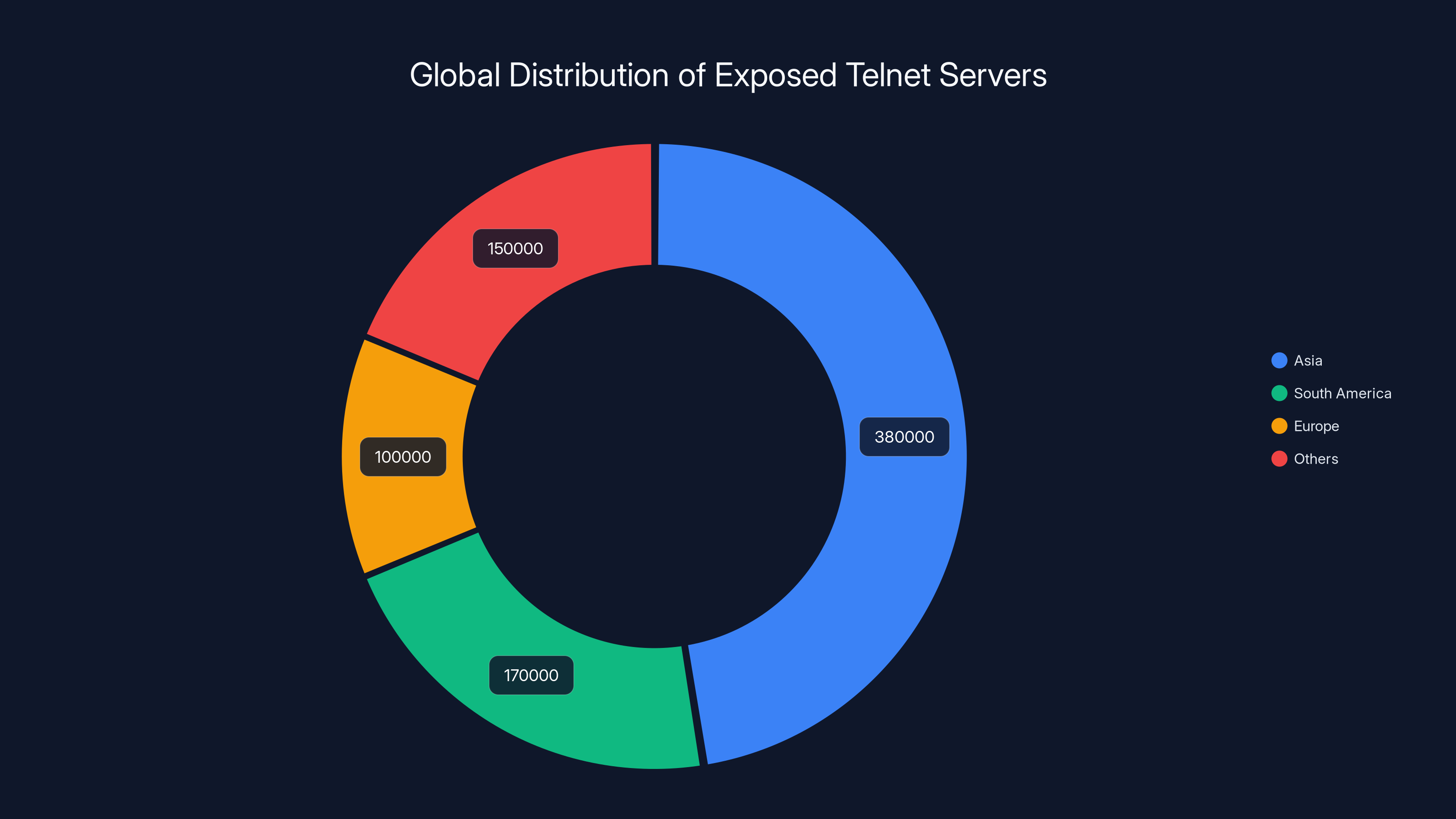

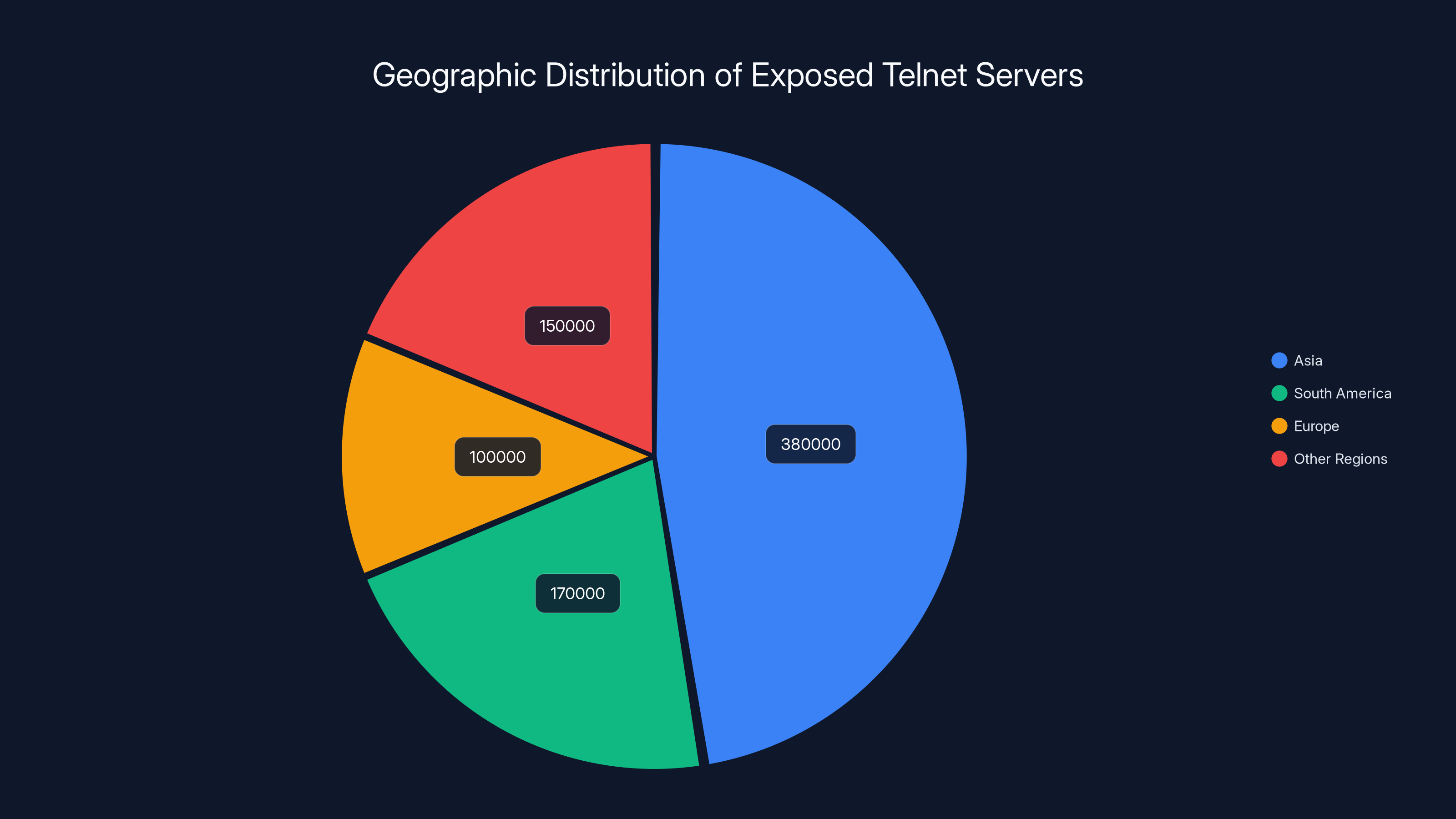

- 800,000 exposed Telnet servers identified worldwide, primarily in Asia (380,000), South America (170,000), and Europe (100,000)

- CVE-2026-24061 affects GNU Inet Utils 1.9.3 through 2.7, rated 9.8/10 severity with critical authentication bypass

- Root access obtained within 24 hours of patch release, with attackers attempting Python malware deployment in 83% of successful breaches

- Immediate actions required: disable Telnet service, block TCP port 23, or apply version 2.8 patch immediately

- Runable can automate security compliance reporting and documentation of remediation efforts across your infrastructure

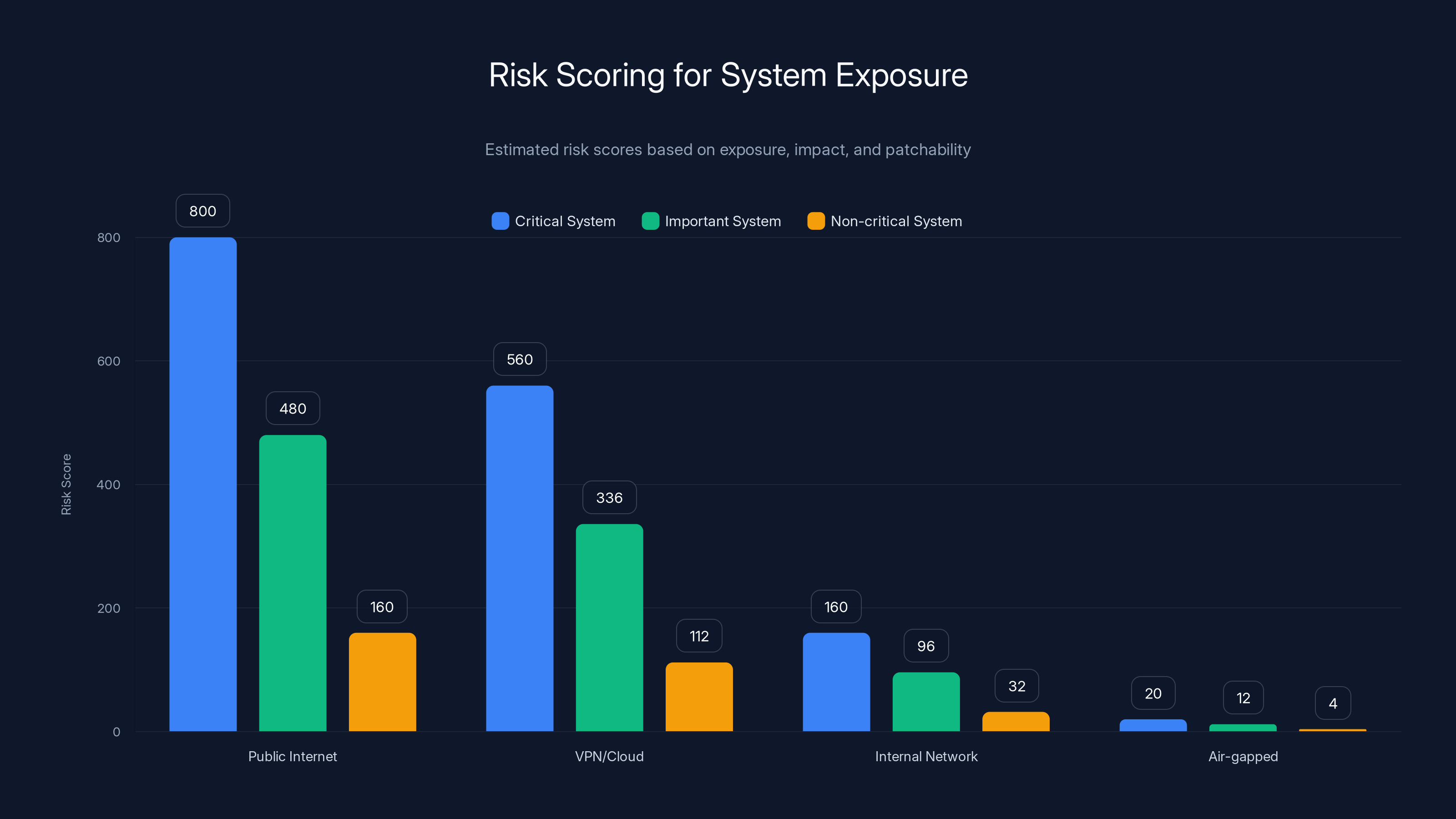

Risk scores highlight the importance of prioritizing publicly exposed critical systems due to their high vulnerability and potential impact. Estimated data based on scoring criteria.

Understanding the Telnet Vulnerability: CVE-2026-24061 Explained

What is Telnet and Why Does It Still Exist?

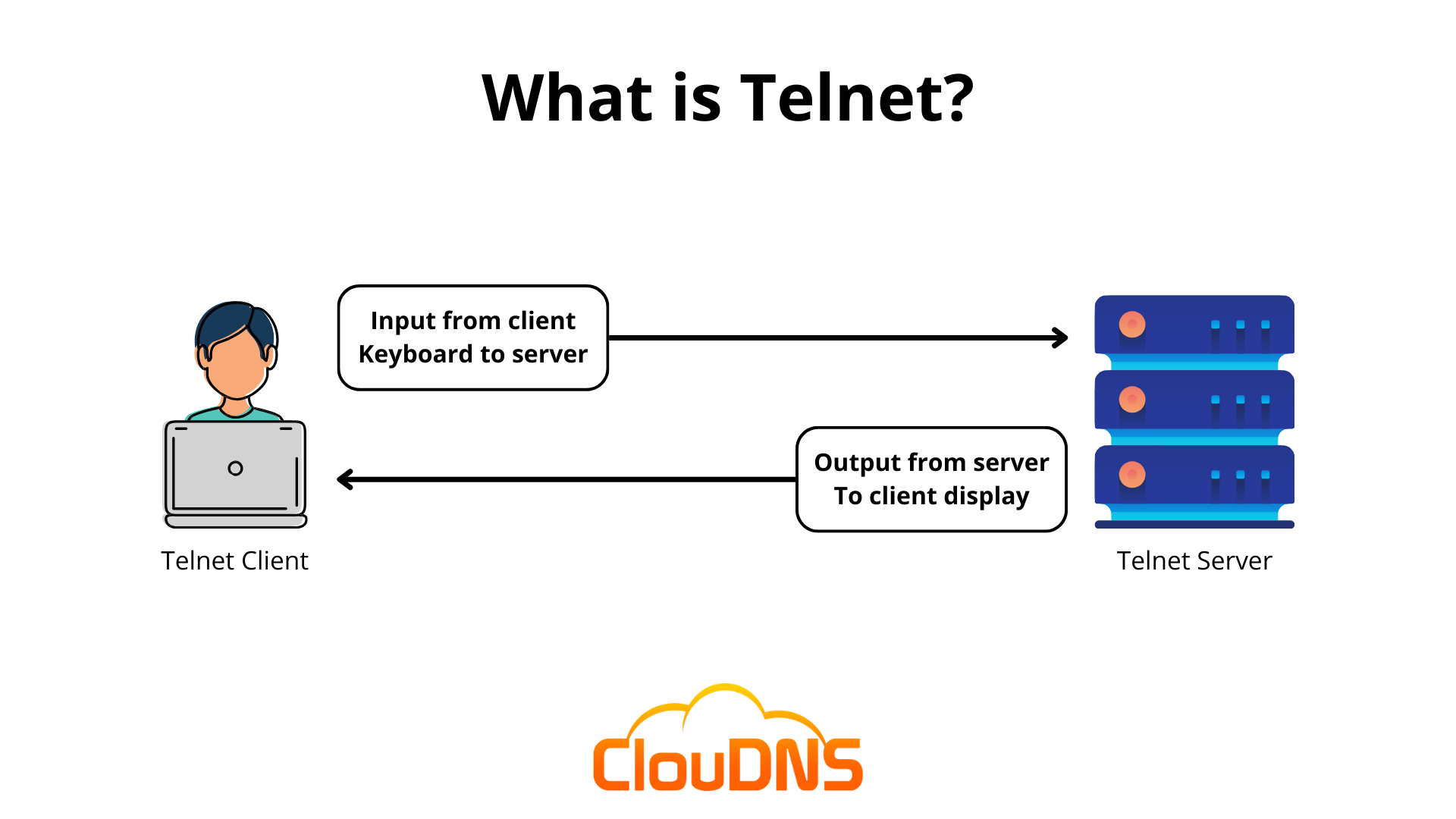

Telnet is ancient. We're talking 1969 ancient—created when the internet was a handful of universities connected by thick cables and trust wasn't even a concept yet. Back then, Telnet solved a real problem: it let you connect to a remote machine and execute commands as if you were sitting at the keyboard.

But here's the problem that became catastrophically obvious within about five minutes of the internet becoming public: Telnet sends everything in plaintext. Your password, your commands, your data—all of it transmitted in the clear like postcards through the mail. No encryption. No obfuscation. Nothing.

SSH (Secure Shell) was created in 1995 specifically to fix this. It's Telnet with encryption, authentication, and proper security controls. There's absolutely no legitimate reason to run Telnet on the open internet anymore. Yet 800,000 systems still are.

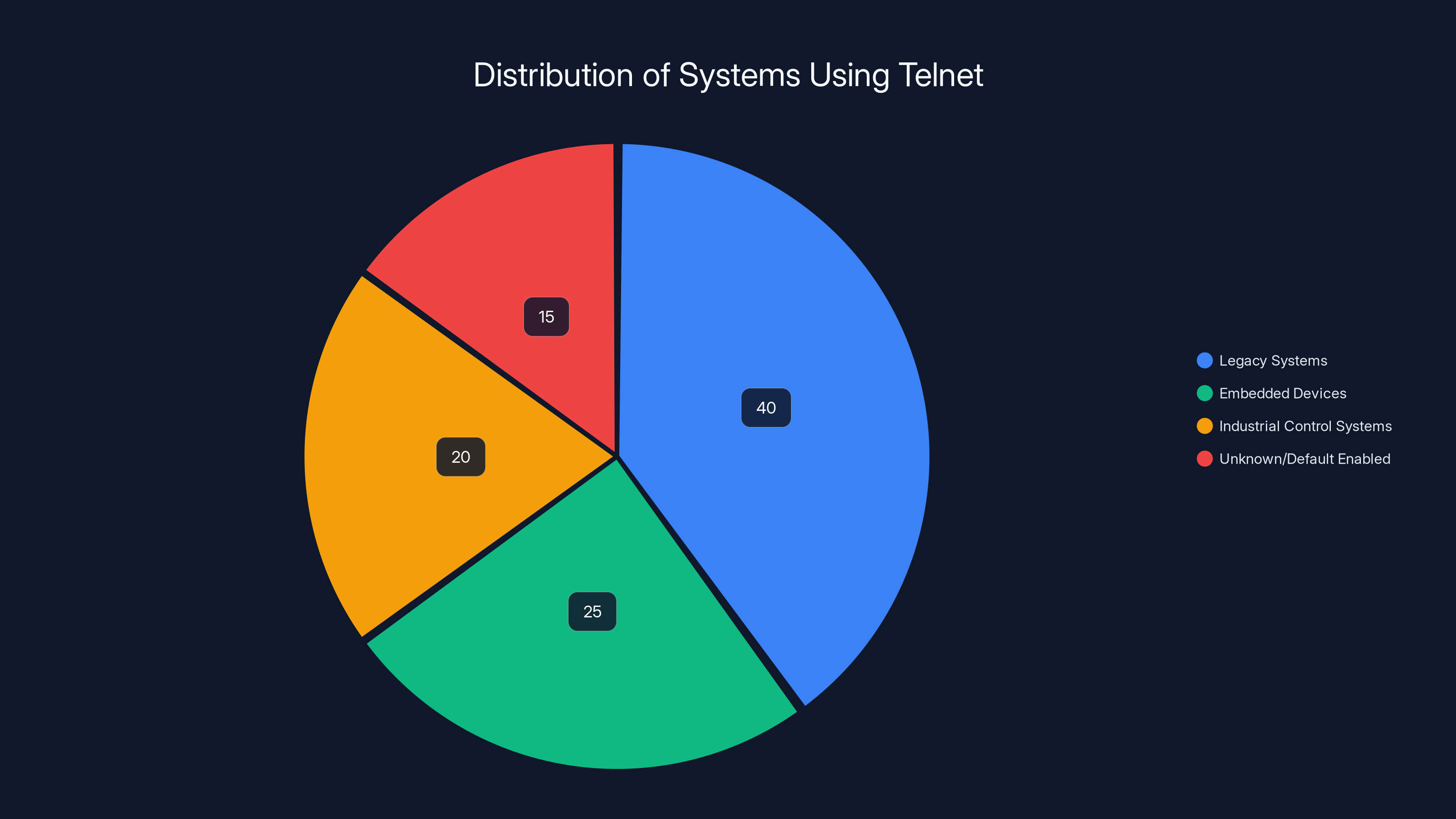

Why? Legacy systems. Industrial control systems that were installed in 1998 and have been running continuously ever since. Embedded devices in network infrastructure that were never designed to be updated. Devices from manufacturers that went out of business years ago. Systems running on specialized operating systems where replacing the software means replacing the hardware.

And then there are the cases where nobody even knew Telnet was enabled. Some systems enable it by default. Some administrators enabled it for "temporary" troubleshooting in 2003 and never turned it off. Some got inherited from previous IT teams that didn't document anything.

The Technical Details: How CVE-2026-24061 Works

The vulnerability is an authentication bypass in GNU Inet Utils, a collection of network utilities that includes the telnetd (Telnet daemon) service. The flaw exists in versions 1.9.3 through 2.7. Think about that version range for a second: it spans from 2015 (version 1.9.3) to early 2024 (version 2.7). That's a nine-year window where the vulnerability existed.

The bypass works at the authentication layer. Normally, when you connect to a Telnet server, it prompts you for a username and password. The server checks those credentials against its authentication system (usually PAM, the Pluggable Authentication Modules system in Linux). If the credentials don't match, access is denied.

With this vulnerability, an attacker can craft a specific type of request that essentially tells the server "trust me, I'm authenticated" without actually providing valid credentials. It's like walking up to a bank teller and saying "the manager approved my withdrawal" without having a manager actually approve it. The server just accepts it because of a flaw in how it handles the authentication handshake.

Once that authentication bypass succeeds, the attacker lands on the system with root privileges. Root access is essentially the master key to a Linux system. You can read any file, modify any file, install any software, disable any security controls, or create new user accounts to maintain persistent access.

Why the 9.8 Severity Rating Matters

CVSS (Common Vulnerability Scoring System) rates vulnerabilities from 0.0 (no impact) to 10.0 (catastrophic). A 9.8 rating isn't just "bad"—it's in the top tier of severity, reserved for vulnerabilities that are trivially exploitable with severe impact.

Breaking down that score: the vulnerability requires no special access (you can exploit it from the internet), no user interaction (you don't need anyone to click a link or open a file), and it impacts all three security pillars: confidentiality (attackers read your data), integrity (they modify it), and availability (they delete it or shut down services).

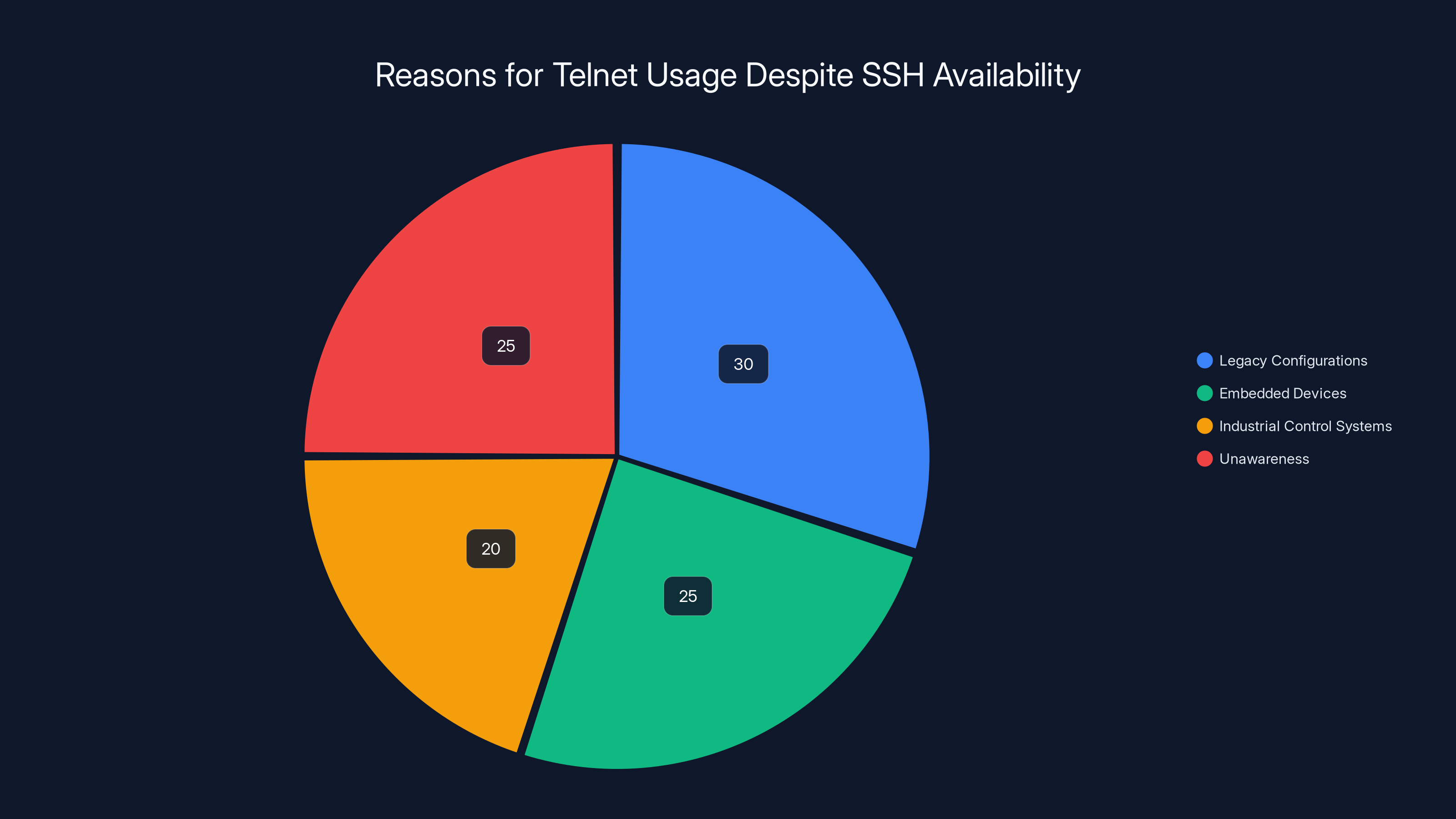

Legacy configurations and unawareness are major reasons for continued Telnet usage, each accounting for 25-30% of cases. (Estimated data)

The Scale of Exposure: 800,000 Devices Worldwide

Geographic Distribution and Risk Hotspots

Shadowserver Foundation's telemetry data paints a stark picture. They identified 380,000 exposed Telnet servers in Asia. That's nearly half of all exposed endpoints globally. The breakdown continues: 170,000 in South America, 100,000 in Europe, with the remainder scattered across other regions.

Why Asia? Several factors converge. First, Asia hosts enormous numbers of legacy manufacturing systems, telecommunications infrastructure, and Io T devices from the pre-cloud era. Second, the region has significant industrial control systems—power plants, water treatment facilities, manufacturing equipment—that were installed decades ago and updated minimally. Third, some regions still have older Telnet-based monitoring and management systems for critical infrastructure that were never replaced because "if it isn't broken, don't fix it."

South America's concentration likely reflects similar patterns: large populations of industrial systems, telecom infrastructure built in earlier decades, and potentially fewer resources dedicated to continuous security updates across national infrastructure.

But here's what's important: geography doesn't matter for attackers. An exposed Telnet server in Singapore is just as exploitable from someone in New Jersey. The "attack surface" these 800,000 devices represent is global.

Which Industries and Systems Are Most Affected?

While Shadowserver's data shows the raw numbers, security researchers and incident response teams have identified specific patterns in what's actually running Telnet:

Industrial Control Systems and SCADA: Manufacturing facilities, power generation plants, and water treatment systems often run ancient embedded systems designed before internet connectivity was even considered. Many have Telnet management interfaces that were intended only for local network use but somehow ended up internet-routable.

Telecommunications Infrastructure: Older networking equipment from manufacturers like Cisco, Juniper, and others often had Telnet as the default remote management protocol. Some of this equipment is still in production networks, gradually being phased out over 5-10 year lifecycles.

Io T and Embedded Devices: Network cameras, environmental monitors, sensors, and various connected devices frequently ship with Telnet enabled. Manufacturers know nobody will update them, so they often don't even bother with SSH support.

Legacy Server Infrastructure: Organizations running older versions of Linux, Unix variants, or specialized operating systems sometimes have Telnet still enabled on internal systems that gradually became "inadvertently" internet-exposed through network configuration changes or cloud migration mistakes.

Network Edge Devices: Routers, load balancers, and access servers sometimes retain Telnet as a fallback management interface, particularly in older deployments.

Timeline of Exploitation: From Patch to Attack

The Patch Released: January 20, 2025

GNU Inet Utils version 2.8 was released on January 20, 2025, containing the fix for CVE-2026-24061. The fix involved correcting the authentication validation logic so that malformed or incomplete authentication requests are properly rejected instead of being implicitly trusted.

For organizations actively monitoring security advisories and patching promptly, January 20 was the day they could begin remediation. For the vast majority of organizations? They probably didn't even know there was a problem yet.

Active Exploitation Begins: January 21

Within 24 hours of the patch being released, threat actors began probing for vulnerable endpoints. This is actually typical for critical vulnerabilities. Security researchers and threat actors both monitor vulnerability disclosure channels. When a critical patch drops, bad actors reverse-engineer the patch to understand what the flaw was, then immediately start scanning for systems that haven't been patched yet.

Grey Noise, a company that maps internet-wide threat activity, detected at least 18 distinct IP addresses initiating Telnet connection attempts. These weren't random scans—they were targeted probes attempting to exploit CVE-2026-24061 specifically.

Within those initial Telnet sessions, attackers attempted to bypass authentication using techniques that exploit the vulnerability. And here's what's critical: in the vast majority of cases, it worked. They gained access. They obtained root privileges. On 83% of successful breaches, they immediately attempted to deploy Python malware.

What the Attackers Did Once Inside

Python malware deployment suggests the attackers were interested in establishing persistent access and potentially recruiting these systems into a botnet. Python is particularly attractive for malware because it's already installed on most Linux systems (it's part of the base operating system), making detection less likely than if they deployed a compiled binary.

The deployment attempts mostly failed, which suggests the Python environment on target systems either wasn't properly configured or the malware had platform-specific issues. But the important thing: they tried. They had a chain of attack ready to execute the moment authentication succeeded.

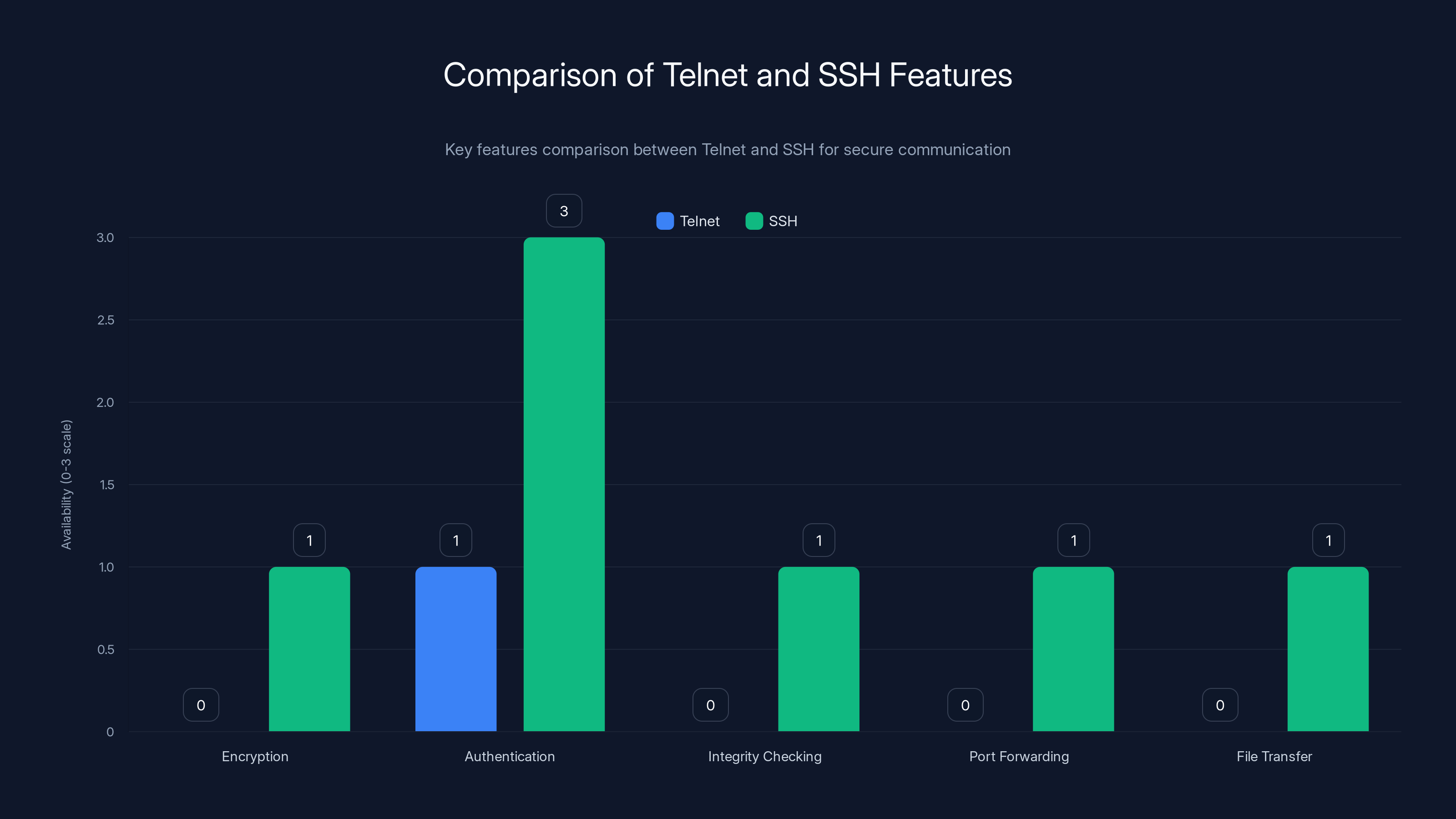

SSH significantly enhances security over Telnet by providing encryption, multiple authentication methods, integrity checking, port forwarding, and secure file transfer capabilities.

Attack Surface Analysis: Who's Actually Vulnerable?

The Direct Risk: Publicly Exposed Telnet Services

If you've got Telnet listening on a public IP address with port 23 accessible from the internet, you're in direct danger. An attacker can connect, exploit CVE-2026-24061, gain root access, and own your system. There's no authentication check. There's no legitimate reason for Telnet to be publicly accessible. This is the clearest, most dangerous position to be in.

For organizations with exposed Telnet endpoints, remediation is urgent. Not "get to it next quarter." Not "prioritize for next maintenance window." Today urgent.

Indirect Risks: Internal Systems with External Pathways

But here's where it gets more complicated for many organizations: you might have Telnet running on internal systems that are supposed to be protected by firewalls, but they're accessible from the internet due to misconfigurations, cloud migration mistakes, or VPN access.

Say you've got a manufacturing system on your corporate network with Telnet enabled for management. A thoughtful administrator put it on your internal network, blocked access with firewall rules, and called it secure. But then someone set up a VPN connection or a remote access solution that didn't properly segregate network access. Or cloud migration changed your network topology. Now that internal system is effectively public.

Or consider: attackers breach something else (your web application, your email system, a weak employee workstation). Once inside your network, they run tools to scan for Telnet services. Now they can pivot to critical infrastructure systems using the same CVE-2026-24061 exploit, gaining the root access needed to compromise your entire infrastructure.

Supply Chain Risk: Devices You Don't Directly Control

If you're running cloud infrastructure, using CDNs, relying on third-party Io T devices, or using managed services, you're potentially affected indirectly. A vulnerable Telnet instance on a device you think is managed and updated could still be exploitable.

Inherited Risk from Acquisitions and Mergers

When organizations merge or acquire other companies, they often inherit their infrastructure. That includes dusty legacy systems running ancient versions of GNU Inet Utils with Telnet enabled. Until your integration team consolidates that infrastructure (which can take 2-5 years), you've got Telnet vulnerability sitting in your environment.

Step-by-Step: Finding Vulnerable Systems in Your Environment

Method 1: Network Scanning with Nmap

The most direct approach is port scanning. Telnet listens on TCP port 23 by default. Running a simple network scan identifies which systems have Telnet listening.

For a specific network range:

bashnmap -p 23 192.168.1.0/24

For the internet (if you want to scan your public IP ranges):

bashnmap -p 23 your_public_ip_range

This will show which IP addresses have port 23 open. But finding the port is only the first step—you need to know which systems are running vulnerable versions of GNU Inet Utils.

Method 2: Version Detection

Once you've identified systems with port 23 open, you can probe them to determine what version is running:

bashnmap -s V -p 23 target_ip

The -s V flag enables version detection. Nmap will attempt to connect and fingerprint the service, potentially revealing the version of GNU Inet Utils.

For more detailed version information, you can connect directly:

bashtelnet target_ip 23

The banner that appears on connection sometimes reveals version information, though many systems are configured to show minimal information for security reasons.

Method 3: Asset Inventory Cross-Referencing

If you maintain an asset inventory (and you should), cross-reference it against:

- GNU Inet Utils versions 1.9.3 through 2.7

- Systems with Telnet enabled

- Devices still in production from the 2000s-2010s era

- Legacy equipment from manufacturers that no longer exist

- Industrial control systems and embedded devices

Your asset management system should have information about OS versions, installed packages, and software versions. Query it for anything matching the vulnerable criteria.

Method 4: Shodan and Internet-Wide Scanning

If you want to understand your external exposure, Shodan and similar services have already scanned the internet and indexed what's publicly accessible. You can search for your organization's IP ranges and see what's exposed.

This is particularly useful for understanding what the attacker sees. If Shodan shows your Telnet service, so do the bad guys.

Asia leads with 380,000 exposed Telnet servers, followed by South America and Europe. Estimated data.

Immediate Remediation: The Three-Step Response

Option 1: Immediate Patch Deployment

If you can upgrade to GNU Inet Utils 2.8 or later, that's the complete fix. The vulnerability is closed. Systems that have been patched are no longer exploitable via CVE-2026-24061.

The challenge: many systems can't simply get patched. Your embedded device from 2005 might run a proprietary version of GNU Inet Utils that won't upgrade cleanly. Your manufacturing system might have dependencies that break if you update core utilities. Or you might have hundreds of systems spread across global locations where coordinating patches is a logistics nightmare.

Option 2: Disable Telnet Service

If patching isn't immediately feasible, disabling the Telnet service eliminates the attack vector entirely. The vulnerability only matters if Telnet is running.

On Linux systems:

bashsudo systemctl disable telnetd

sudo systemctl stop telnetd

Or, if using older init systems:

bashsudo service telnetd stop

For embedded systems or systems where you can't disable the service directly, you can comment out the Telnet line in /etc/inetd.conf or /etc/xinetd.d/telnet depending on your system configuration.

The caveat: disabling Telnet means you lose that remote management access. If Telnet was being used for legitimate system administration, you need a replacement. SSH is the obvious choice, but getting SSH installed and configured on legacy systems sometimes requires vendor support or specialized knowledge.

Option 3: Firewall-Level Blocking

If you can't patch or disable Telnet, you can block access at the firewall level. This prevents the vulnerability from being exploited remotely, but it doesn't fix the underlying system.

Blocking TCP port 23 at your border firewall:

bash# iptables example (older systems)

sudo iptables -A INPUT -p tcp --dport 23 -j DROP

# firewalld example (newer systems)

sudo firewall-cmd --permanent --add-rich-rule='rule family="ipv 4" port protocol="tcp" port="23" reject'

For systems that legitimately need Telnet access, you can create exceptions:

bashsudo firewall-cmd --permanent --add-rich-rule='rule family="ipv 4" from="192.168.1.0/24" port protocol="tcp" port="23" accept'

This allows Telnet access only from your internal network (192.168.1.0/24) while blocking it from the internet.

Detection and Monitoring: Identifying Active Exploitation

Network-Based Detection

If you have network monitoring tools (IDS/IPS systems, SIEM platforms, or packet capture capabilities), you can look for exploitation attempts.

Indicators of Compromise:

-

Telnet connections from unexpected sources: Normal Telnet traffic should come from known IP addresses (your network operations center, specific engineer workstations, your management network). Traffic from random internet IPs is suspicious.

-

Failed authentication attempts followed by successful connections: If logs show multiple failed Telnet login attempts immediately followed by a successful session, it could indicate exploitation. Legitimate administrators usually get login right on the first try.

-

Telnet sessions immediately spawning unexpected processes: If Telnet sessions are followed by execution of python, bash, wget, curl, or other utilities, that's a red flag for malware deployment.

-

Root access via Telnet: Check Telnet logs for authentication as root or sudo elevation. Telnet access should generally go to service accounts or non-root users, not directly to root.

System-Based Detection

On affected systems themselves, you can monitor for exploitation:

Check system logs:

bash# Telnet access logs (location varies by system)

tail -f /var/log/auth.log

tail -f /var/log/secure

# Look for unexpected Telnet connections

grep "telnet" /var/log/auth.log

Monitor process execution:

bash# List current processes and their parents

ps aux

# Look for unusual Python processes, particularly those spawned by telnetd

ps aux | grep python

ps aux | grep telnetd

# Check for unexpected cron jobs

crontab -l

cat /etc/cron.d/*

Network connection monitoring:

bash# View established connections

netstat -an | grep ESTABLISHED

ss -an | grep ESTABLISHED

# Look for connections from Telnet-spawned processes

lsof -p [telnetd_pid]

Using Runable to Automate Monitoring Documentation

For organizations managing multiple systems, keeping track of which devices are patched, which are blocked at the firewall, and which are being monitored becomes complex quickly. Runable can help automate the creation of remediation reports and compliance documentation. You can generate automated status reports across your infrastructure showing patch status, firewall rules applied, and monitoring configurations, all in AI-generated documents that track your security posture over time.

Estimated data shows that legacy systems account for the largest share of systems still using Telnet, followed by embedded devices and industrial control systems.

Long-Term Strategy: Replacing Telnet Infrastructure

Why You Need an End-of-Life Plan for Telnet

Even after you've addressed CVE-2026-24061, the larger issue remains: Telnet is fundamentally insecure. It has no encryption, no modern authentication, and no integration with security frameworks that matter today (MFA, certificate authentication, zero trust).

The best remediation isn't patching—it's replacing Telnet with SSH or, in modern infrastructure, eliminating direct remote access entirely in favor of API-based management and orchestration.

Migration Path 1: SSH as a Direct Replacement

SSH is Telnet's security-conscious successor. It provides:

- Encryption: All communication is encrypted

- Authentication: Multiple authentication methods (passwords, keys, certificates)

- Integrity checking: Ensures data wasn't modified in transit

- Port forwarding: Can tunnel services securely

- File transfer: SFTP and SCP for secure file operations

For systems where Telnet is used for remote command execution, SSH is a near-perfect drop-in replacement. The learning curve is minimal, the tooling is available on every modern operating system, and support across device manufacturers is nearly universal.

Migration approach:

- Identify all systems currently using Telnet

- Verify SSH is available on those systems (most ship with it installed)

- Configure SSH on systems where it's not already running

- Update documentation, scripts, and automation tools to use SSH instead of Telnet

- Test SSH access thoroughly before removing Telnet

- Disable Telnet

- Monitor for any systems that break due to the change

Migration Path 2: API-Based Management

For modern infrastructure, the better approach is eliminating interactive shell access entirely. Instead of connecting to systems and running commands, management should happen through APIs.

Examples:

- Kubernetes clusters: Use kubectl (API-based) instead of Telnet to container nodes

- Cloud infrastructure: Use cloud provider APIs (AWS, Azure, GCP) instead of Telnet to EC2 instances

- Network equipment: Use RESTCONF, NETCONF, or proprietary APIs instead of CLI access

- Io T devices: Use device management platforms with APIs instead of direct access

This approach has multiple advantages:

- Better security: You're not exposing shell access, limiting the blast radius of compromised credentials

- Better auditability: API calls can be logged and traced more reliably

- Better scalability: You're not managing individual shell connections for thousands of devices

- Better integration: APIs integrate naturally with automation frameworks and orchestration platforms

Migration Path 3: Zero Trust Access

For organizations serious about modern security, the ultimate goal is zero trust: no implicit trust in any connection, regardless of whether it's from internal or external networks.

Zero trust access to systems means:

- Identity verification: Verify who you are (MFA, certificate, workstation verification)

- Device verification: Verify your workstation is secure and compliant

- Least privilege: Grant access only to the specific systems you need, for the specific time you need it

- Session recording: Record everything that happens during the session for auditability

- Anomaly detection: Alert if behavior deviates from normal patterns

Solutions like Beyond Trust, Cyber Ark, Hashi Corp Boundary, and similar tools implement zero trust access. They're more complex to deploy than SSH, but they're also significantly more secure and audit-friendly.

Organizational Impact Assessment

Risk Scoring for Your Environment

Not all Telnet exposure is equally dangerous. A Telnet service on an internal system that's air-gapped from the internet is lower risk than one sitting directly on your public IP. A system running non-critical applications is lower risk than one running payment processing or healthcare data systems.

Score your exposure by considering:

Exploitability: How easy is it for an attacker to reach and exploit the system?

- Public internet exposure: 10 points

- VPN or cloud-accessible: 7 points

- Internal network only: 4 points

- Air-gapped/offline: 1 point

Impact: What damage would exploitation cause?

- Critical business system (payment, healthcare, operations): 10 points

- Important but not critical (monitoring, logging): 6 points

- Non-critical (test systems, development): 2 points

Patchability: How quickly can you address it?

- Patches available and tested: 1 point

- Patches available but complex deployment: 4 points

- Difficult or impossible to patch: 8 points

Multiply these three scores. A publicly exposed critical system that can't be easily patched scores 10 × 10 × 8 = 800. A non-critical internal system with available patches scores 4 × 2 × 1 = 8. Clearly, you should prioritize the first one.

Budget and Resource Planning

Remediating 800,000+ systems globally (if you're a large organization with hundreds or thousands of systems) requires planning:

Immediate costs (first 30 days):

- Scanning and assessment: 40-80 hours of skilled security personnel

- Firewall rule implementation: 20-40 hours of network engineering

- Notification and communication: 20-30 hours of security operations

- Total: roughly 15,000 in labor for a mid-sized organization

Short-term costs (30-90 days):

- Patch deployment, testing, and validation: 100-300 hours depending on environment size

- System down time and coordination: varies widely

- Replacement systems for devices that can't be patched: varies widely

- Total: 100,000+ depending on your infrastructure

Long-term costs (90+ days):

- SSH hardening and deployment

- Zero trust infrastructure implementation (if pursuing that path)

- Ongoing monitoring and compliance

- Total: varies significantly based on organizational goals

Asia accounts for nearly half of the exposed Telnet servers globally, with 380,000 devices, highlighting significant security vulnerabilities in legacy systems. Estimated data.

Lessons Beyond CVE-2026-24061

Why Legacy Systems Remain a Perpetual Vulnerability

This vulnerability isn't unique. It follows a pattern that repeats regularly:

- Software reaches the end of active development: Maintainers move on, stop accepting patches, effectively declare the software stable

- Users continue using it because it works, changing it is risky, and there's no business case for an upgrade

- A vulnerability is discovered in code that hasn't been maintained in years

- Exploitation happens at scale because so many people are still using it

- Organizations scramble to fix something that should have been addressed years ago

This exact pattern has repeated with Telnet for 15+ years. It happened with Open SSL (Heartbleed). It happened with Apache Struts. It'll happen again with something else that reaches end-of-life while millions still use it.

The Inventory Problem

A theme that emerges across every major vulnerability response: organizations don't actually know what systems they're running. An organization discovers Telnet is enabled on systems they own but nobody has heard of. They find devices from 2008 still in production racks with nobody claiming responsibility for them. They discover that the "legacy system" supposedly being phased out is still handling critical transactions.

Invention and asset management aren't flashy security work. They don't get executive attention until a vulnerability like this forces the conversation. But they're foundational. You can't patch what you don't know exists.

The Vendor Problem

Many of the most exposed systems are embedded devices or appliances where updating the OS or installed utilities requires vendor intervention or specialized tools. A manufacturer may have stopped supporting a product 10 years ago. Do they issue patches for a 9-year-old vulnerability? Often not. Organizations are left with a choice: accept the vulnerability, replace the entire device, or find workarounds like firewall blocking.

This isn't a new problem, but it's one that manufacturers haven't solved well. The software supply chain remains fragmented and insecure.

Broader Context: The State of Critical Infrastructure Security

Why Telnet on Critical Infrastructure Still Matters

The 800,000 exposed Telnet servers aren't just random internet-of-things devices. Many are running critical infrastructure. Power plants use systems with Telnet management interfaces. Water treatment facilities operate equipment remotely accessed via Telnet. Industrial control systems that manufacture goods rely on embedded systems with Telnet enabled.

When you compromise a system running critical infrastructure via a Telnet vulnerability, the impact goes far beyond that one system. A compromised power grid management system could cause widespread outages. A compromised water treatment facility could contaminate water supplies. A compromised manufacturing control system could halt production or damage products.

This is why CVE-2026-24061 hit threat intelligence feeds so hard. It's not just about data theft—it's about operational disruption and potentially physical safety.

The Internet of Aging Things

We're entering an era where "legacy systems" outnumber new systems. The average age of deployed infrastructure has steadily increased. Devices that were designed for 5-year lifecycles are still running after 15-20 years. Systems that were never intended to be internet-connected end up on networks that connect to the internet. Security patches were never part of the design philosophy.

We're going to keep seeing critical vulnerabilities in ancient systems. The question is whether organizations take proactive measures now or keep responding reactively to crises.

Practical Checklist: What You Need to Do This Week

If you've read this far, you know CVE-2026-24061 is serious. Here's what your action items should be:

Day 1: Awareness and Communication

- Ensure your security leadership knows about CVE-2026-24061

- Schedule a brief meeting with infrastructure, network operations, and system administration teams

- Communicate the situation to executives (this might require external incident response or cyber insurance notifications)

- Document what you find—you'll need this information for incident response tracking

Day 2-3: Assessment

- Scan your network for systems listening on port 23 (run Nmap, query monitoring systems, check Shodan)

- Document findings: which systems are exposed, which ones are internal, which are critical

- Identify which systems can be patched immediately versus which require workarounds

- Check your public IP ranges against Shodan to see what's publicly visible to attackers

Day 4-5: Immediate Mitigation

- Implement firewall rules to block port 23 from the internet on all external-facing systems

- If possible, disable Telnet on systems that aren't actively using it

- Begin patch testing on a small subset of systems that can be updated safely

- Set up monitoring alerts for Telnet connection attempts or suspicious activity

By End of Week: Long-Term Planning

- Develop a patch deployment timeline for all affected systems

- Identify systems that can't be patched and plan replacement or mitigation strategies

- Update documentation and runbooks to reflect changes

- Schedule follow-up reviews to verify remediation progress

Automating Compliance and Remediation Tracking

For teams managing complex remediation efforts, Runable can help streamline the process of generating compliance reports, documenting remediation progress, and tracking security posture across your infrastructure. Instead of manually creating spreadsheets and status documents, you can automate report generation showing which systems have been patched, which firewalls have been updated, and which systems remain on your remediation roadmap.

Use Case: Generate automated security compliance reports tracking CVE remediation status across your entire infrastructure.

Try Runable For Free

FAQ

What exactly is CVE-2026-24061 and how does it work?

CVE-2026-24061 is an authentication bypass vulnerability in GNU Inet Utils versions 1.9.3 through 2.7 that affects the Telnet daemon (telnetd). It allows attackers to craft specially formed requests that bypass the authentication mechanism, gaining immediate root-level access to affected systems without providing valid credentials. The vulnerability exists in how the authentication handshake validates user credentials, essentially trusting incomplete or malformed authentication attempts that should be rejected.

Why do so many systems still have Telnet enabled when SSH is available?

Many systems have Telnet enabled due to legacy configurations, embedded devices designed before security was a priority, industrial control systems that can't be easily updated, and cases where nobody realizes Telnet is even enabled. Some devices are so old that SSH wasn't available when they were installed, and replacing them would cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. Other organizations simply inherited Telnet-enabled systems from previous administrations and never documented them for remediation.

How can I check if my organization is affected?

Start by scanning your network for systems listening on TCP port 23 using tools like Nmap. Check your asset inventory for systems running GNU Inet Utils versions 1.9.3 through 2.7, particularly legacy or industrial equipment. Search your public IP ranges on Shodan to see what's visible to attackers from the internet. Finally, check your firewall logs to see if there are any blocked Telnet connection attempts, which would indicate the vulnerability is already being probed.

What's the difference between patching, disabling, and blocking Telnet?

Patching (upgrading to version 2.8 or later) fixes the vulnerability but leaves the service running. Disabling Telnet (via systemctl stop telnetd) removes the attack surface entirely but breaks any legitimate access that depends on Telnet. Firewall blocking (dropping port 23 traffic) prevents remote exploitation without modifying the systems themselves, but the vulnerability still technically exists if someone gains internal network access. Each approach has trade-offs depending on your environment.

Should I migrate directly to SSH or pursue a zero trust architecture?

SSH is the practical immediate step for most organizations. It's a direct Telnet replacement, widely supported, and solves the authentication bypass vulnerability immediately. Zero trust architecture is the long-term goal for security-mature organizations, but it requires more extensive infrastructure changes and implementation complexity. Most organizations should plan for SSH in the near term (30-90 days) and zero trust in the long term (1-2 years) as a strategic initiative.

How do I know if my systems have been actively exploited?

Check Telnet access logs for successful connections from unexpected sources, failed authentication attempts followed by successful connections, or root access via Telnet when that shouldn't be possible. Monitor system processes for unexpected Python execution, malware downloads (wget, curl), or SSH key generation following Telnet sessions. Network monitoring tools should be checked for unusual outbound connections. If you suspect compromise, perform a full forensic investigation with incident response professionals.

What should I prioritize if I have multiple exposed Telnet systems?

Prioritize based on a risk matrix considering exploitability (how exposed is it to the internet), impact (how critical is the system), and patchability (how quickly can you fix it). Critical systems with public internet exposure should be remediated first. Non-critical internal systems can follow. Estimate 10-30% effort should go to immediate containment (firewall blocking), 60-70% to patching and remediation, and 10% to long-term infrastructure improvements.

Why can't vendors just force patches automatically?

Automatic patching breaks things. Not all systems can tolerate automatic updates—industrial control systems might fail if utilities change without proper coordination, embedded devices might lose stability, and some organizations can't afford the downtime. Additionally, many systems are no longer supported by their original vendors, so there's nobody to push patches from. This is why asset lifecycle management and end-of-life planning are so important.

Conclusion: Taking Action in an Imperfect Infrastructure

The discovery of 800,000 exposed Telnet servers is a wake-up call, but it's also a wake-up to something security professionals have known for years: legacy systems don't disappear. They accumulate. They become invisible. They represent technical debt that compounds over time.

CVE-2026-24061 is urgent because it's actively being exploited, but it's a symptom of a larger problem: infrastructure that was never designed with security as a core principle, deployed decades ago, and never properly updated or replaced.

Your response should be immediate and multi-layered. This week, you should identify exposed systems and block them at the firewall. Over the next month, you should begin patching and disabling services. Over the next year, you should plan to replace Telnet infrastructure entirely with modern, secure alternatives.

But beyond CVE-2026-24061, you should take steps to prevent this situation from recurring. Implement asset inventory systems so you know what you're running. Establish vulnerability management processes with SLA-based remediation timelines. Plan end-of-life strategies for aging infrastructure rather than letting it silently accumulate vulnerabilities. Consider zero trust architectures that eliminate the need for direct remote access entirely.

The 800,000 exposed servers represent organizations where these processes broke down. Don't let your infrastructure be the next statistic when the next critical vulnerability emerges.

Key Takeaways

- CVE-2026-24061 is a critical authentication bypass in GNU InetUtils affecting 800,000+ systems globally with a 9.8/10 severity rating

- Threat actors began exploiting the vulnerability within 24 hours of patch release, achieving root access on 83% of successful compromises

- Immediate actions: block port 23 at firewalls, disable Telnet services, or deploy patches to GNU InetUtils 2.8 or later

- Asia represents 47.5% of exposed Telnet servers, followed by South America (21.25%) and Europe (12.5%)

- Long-term strategy should move from Telnet → SSH → API-based management → zero trust architecture to prevent future legacy vulnerabilities

Related Articles

- Nike Data Breach: What We Know About the 1.4TB WorldLeaks Hack [2025]

- Microsoft's Example.com Routing Anomaly: What Went Wrong [2025]

- Browser-Based Attacks Hit 95% of Enterprises [2025]

- Pegasus Spyware, NSO Group, and State Surveillance: The Landmark £3M Saudi Court Victory [2025]

- AI-Powered Malware Targeting Crypto Developers: KONNI's New Campaign [2025]

- Proton VPN Linux Overhaul 2025: Complete GUI & CLI Guide

![800,000 Telnet Servers Exposed: Complete Security Guide [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/800-000-telnet-servers-exposed-complete-security-guide-2025/image-1-1769524741908.jpg)