Harvard and UPenn Data Breaches: What You Need to Know [2025]

Late 2024 brought unwanted news to two of America's most prestigious universities. Hackers infiltrated Harvard University and the University of Pennsylvania's systems, stealing sensitive information on millions of students, alumni, staff, and donors. The breach didn't just expose names and email addresses—it revealed home addresses, dates of birth, donation histories, and deeply personal demographic information including race, religion, and sexual orientation.

This wasn't a quiet incident that stayed contained. When ransom negotiations fell apart, the hacking group Shiny Hunters published everything. All of it. More than a million records now sit on dark web marketplaces, available to anyone with access to download and exploit.

If you're connected to either institution—or just concerned about data security in general—you need to understand what happened, why it happened, and what you can do about it. Let's break down the entire situation and what it means for data privacy going forward.

TL; DR

- Over 1 million records stolen from Harvard and UPenn by Shiny Hunters hackers in late 2024

- Personal data exposed includes names, addresses, dates of birth, phone numbers, donation histories, and demographic information

- Attack vectors included single sign-on (SSO) compromise and voice phishing (vishing)

- Failed negotiations led hackers to publish all stolen data on dark web marketplaces

- Students, alumni, donors, and staff are all potentially affected across both universities

- Bottom line: This is one of the largest educational institution breaches on record, affecting millions of people with deeply personal information now in criminal hands.

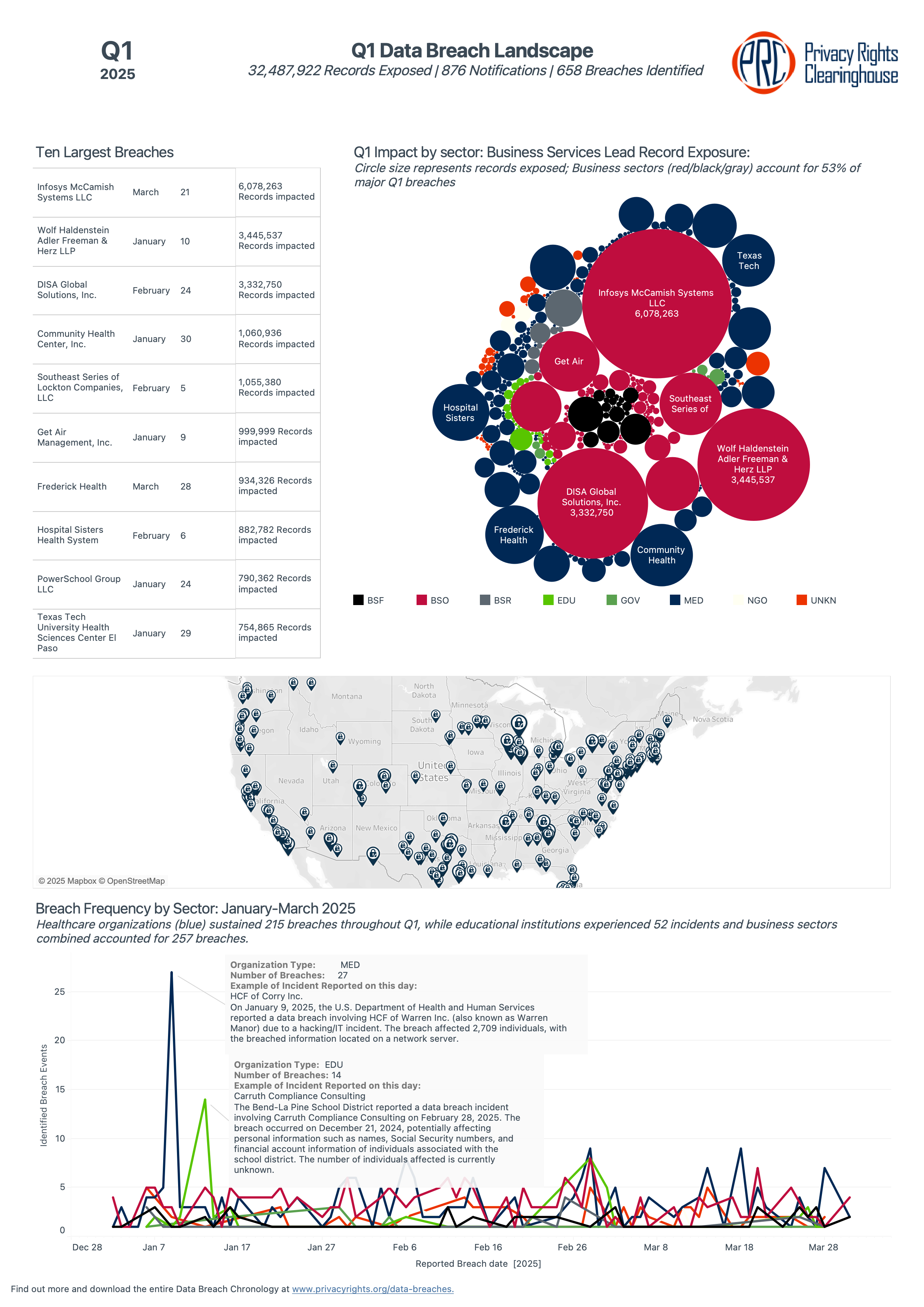

Estimated data shows that legal fees and breach notification costs are the largest expenses in a major data breach, each accounting for around 20-25% of the total financial impact.

How the Breaches Happened: The Technical Timeline

Understanding how these breaches occurred is crucial because it reveals vulnerabilities that likely exist at thousands of other organizations. The attacks weren't sophisticated in the way most people imagine cybercrime. They weren't zero-day exploits or mysterious backdoors. They were remarkably straightforward, which makes them even more concerning.

In early November, the Shiny Hunters group disclosed that they'd gained access to a University of Pennsylvania employee's single sign-on (SSO) account. This wasn't obtained through some elaborate technical hack. It's far more likely they used standard social engineering tactics or credential stuffing—testing stolen username and password combinations obtained from previous breaches.

Once they controlled that single SSO account, the real damage began. That one compromised credential gave them access to an astonishing range of systems. We're talking about the university's VPN (Virtual Private Network), Salesforce CRM databases, Qlik analytics platforms, SAP business intelligence systems, and Share Point file repositories. One account. That's all it took.

Harvard's breach came through a slightly different vector—voice phishing, or "vishing." Someone called a Harvard employee pretending to be from IT support, social engineering them into revealing credentials or clicking a malicious link. That access point led hackers directly into the Alumni Affairs and Development systems, which contain decades of accumulated donor and alumni information.

The attackers then weaponized their access in creative ways. Beyond just downloading sensitive files, they used the compromised accounts to send phishing emails to approximately 700,000 UPenn recipients. These weren't subtle spear phishing attempts. They were deliberately offensive, designed to embarrass the institution and create chaos.

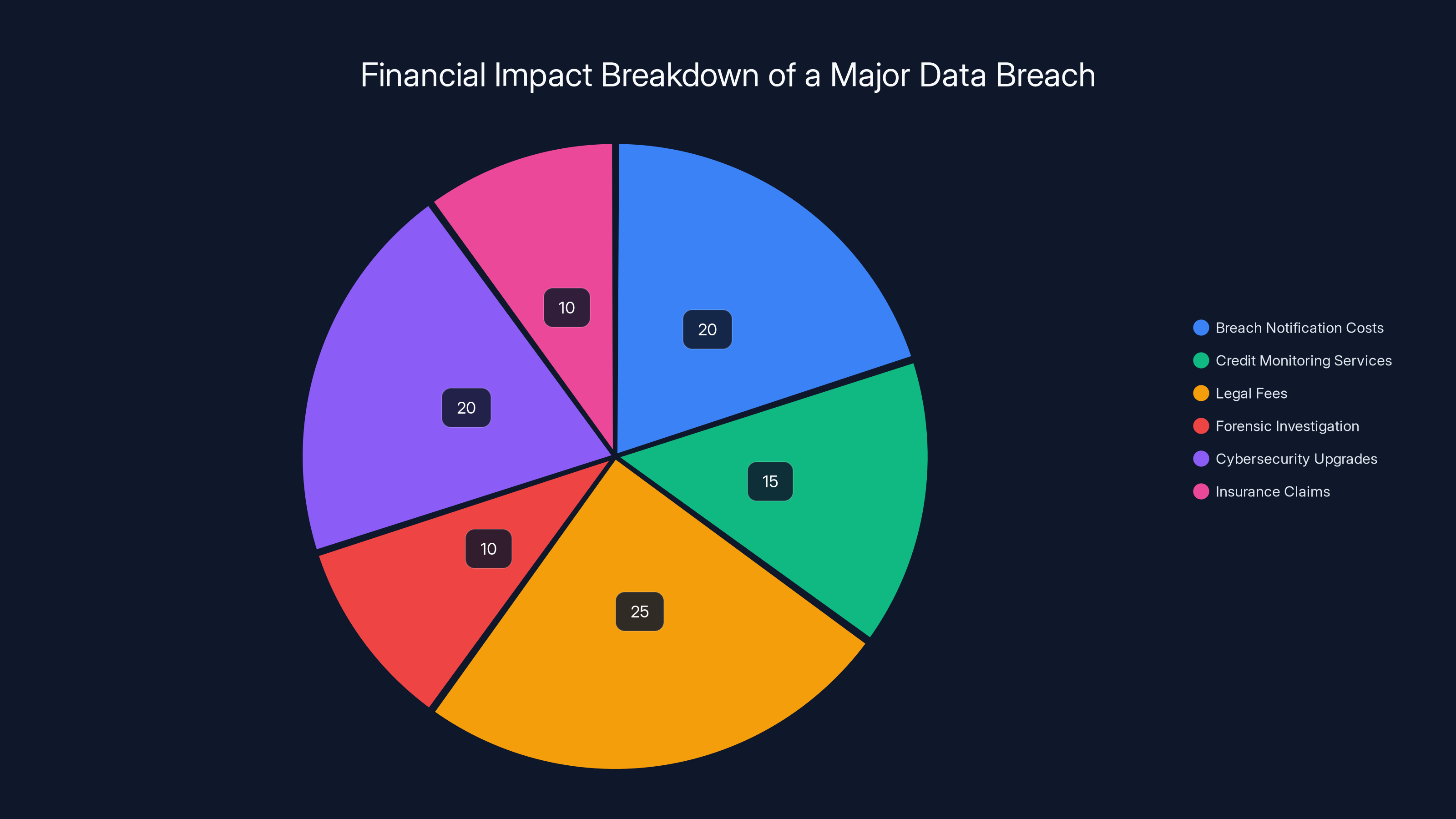

The criminal supply chain for stolen data involves indexing, purchasing, weaponizing, and consolidating data, with increasing impact at each stage. Estimated data.

The Scale of the Breach: Understanding the Numbers

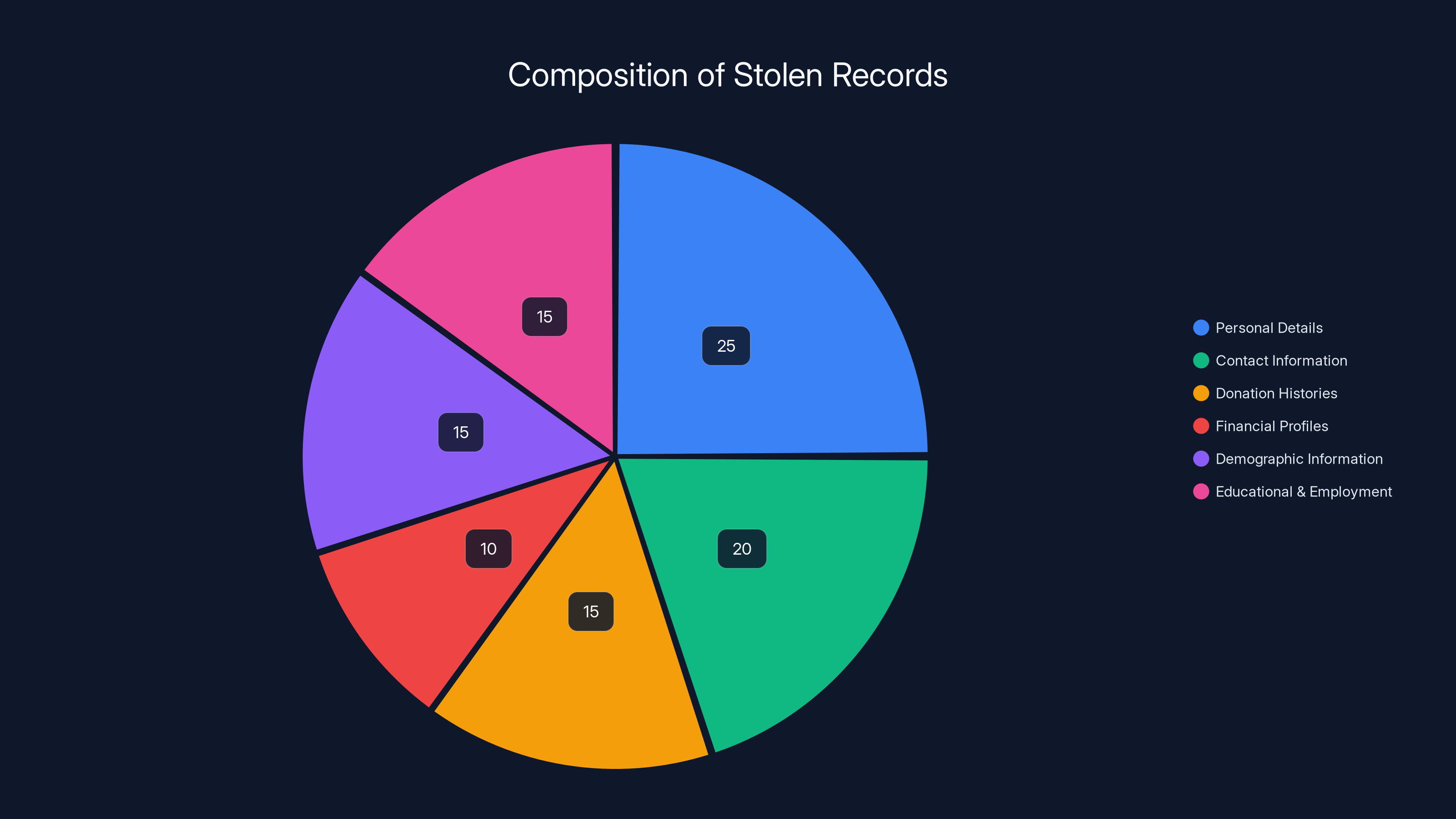

When we talk about "over a million records," what does that actually mean? Let's break down the scope of what was stolen and why the numbers matter.

Shiny Hunters claims to have stolen more than 1 million distinct records from both institutions combined. To put this in perspective, Harvard University has approximately 23,000 students enrolled, plus tens of thousands of alumni, faculty, and staff. The University of Pennsylvania has roughly 21,000 students. So how do you get to a million records?

The answer is that universities maintain information far beyond just current students. They track decades of alumni relationships, donor profiles, family members associated with donors, spouses and partners of alumni, parents of current and former students, and faculty spanning generations. A single person might have multiple records in different systems. An alumnus who donated multiple times, attended different programs, and referred family members could easily have 5-10 separate records across different databases.

When Tech Crunch investigated the stolen data, they verified a significant portion of the dataset. They confirmed that the information included personal details that go far beyond what most people consider public information. We're not just talking about names and email addresses here.

The dataset included:

- Full names of students, alumni, faculty, and donors

- Home addresses with complete street addresses

- Dates of birth, which can be used for identity theft

- Phone numbers, both personal and professional

- Donation histories, including amounts donated and the organizations they donated to

- Estimated net worth, compiled from financial profiles

- Demographic information, including race, religion, and sexual orientation

- Educational histories, including graduation dates and degrees

- Employment information, including current and past employers

- Family relationships, showing connections between donors and relatives

This isn't just personally identifiable information. This is the kind of deeply personal data that enables sophisticated social engineering, targeted phishing campaigns, and identity theft. Someone with access to this information knows where you live, how much money you probably have, your religious beliefs, your sexual orientation, and your family connections.

What Happened at UPenn: The SSO Compromise

The University of Pennsylvania's breach was the first to be disclosed, and it involved the most direct technical compromise. A single employee's SSO account gave hackers the keys to the kingdom, and they used those keys extensively.

Once inside, they had access to multiple critical systems. The Salesforce database likely contained detailed records of donor relationships, interactions, and giving history. This is the kind of information that development offices rely on to cultivate major gifts. Losing it to criminals means losing donor privacy and exposing the institution's entire fundraising strategy.

The Qlik analytics platform gave them access to business intelligence and reporting. These systems typically contain aggregated data about university operations, enrollment trends, financial information, and more. Analytics platforms are designed to surface patterns and insights, which means criminals could see exactly where the institution's most valuable information was stored.

Access to SAP—the university's enterprise resource planning system—meant they could see financial data, HR information, student records, and operational details. SAP systems are incredibly comprehensive; they track everything from payroll to procurement to asset management.

Share Point file repositories rounded out the damage. Share Point is where university employees store documents, share information across departments, and collaborate. Somewhere in those Share Point systems were likely sensitive documents, strategic plans, compliance records, and possibly personal information that employees had stored there.

When UPenn first became aware of the breach, they issued a statement saying the phishing emails were "obviously fake" and "fraudulent." This was a communication misstep. Within weeks, they had to backtrack and admit that no, this was actually a real compromise. The university had been breached. Their systems had been accessed. Their data was stolen.

The fallout was immediate and substantial. UPenn had to notify hundreds of thousands of people that their personal information had been compromised. They had to deal with regulatory notifications, potential regulatory fines, legal liability, and institutional reputation damage.

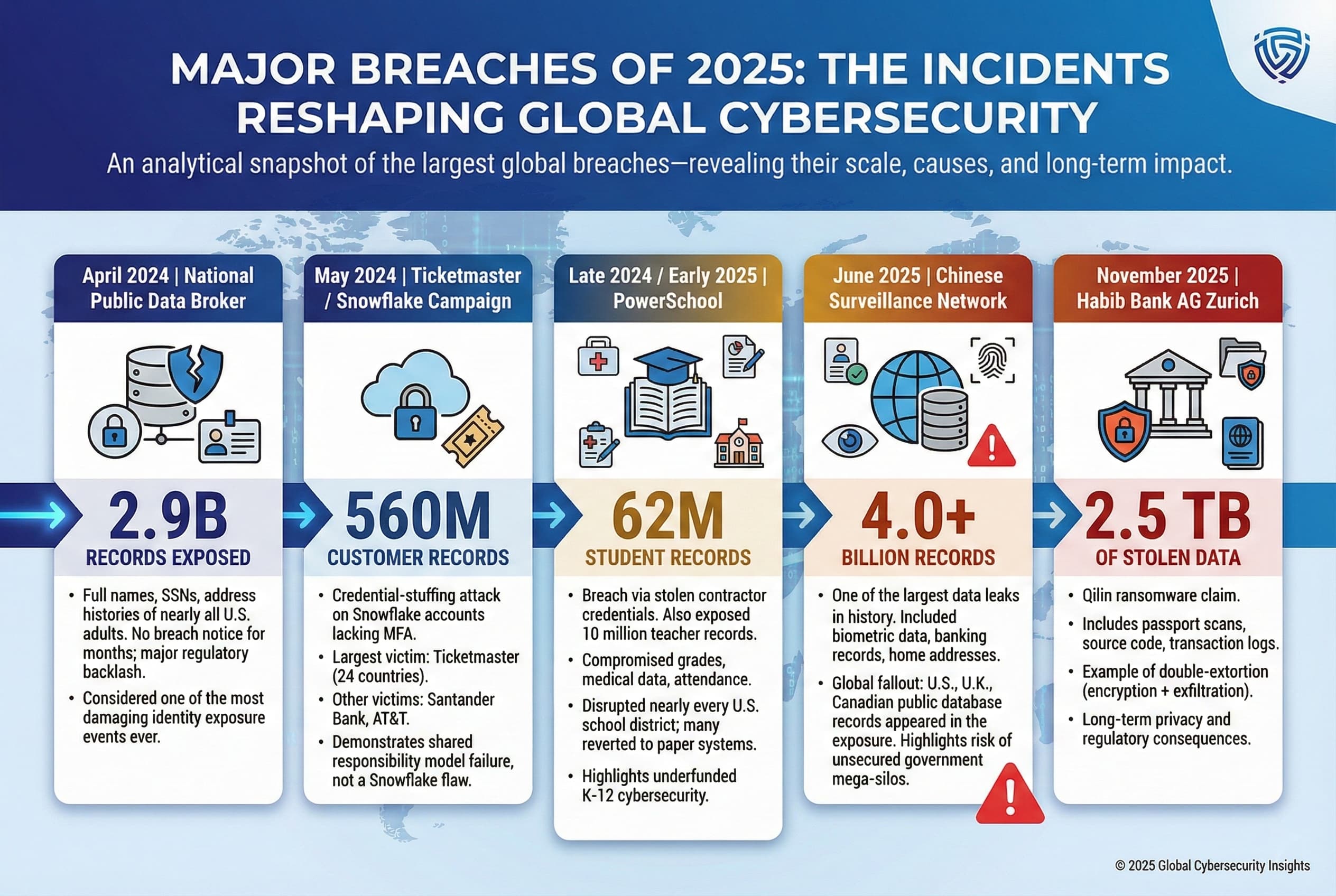

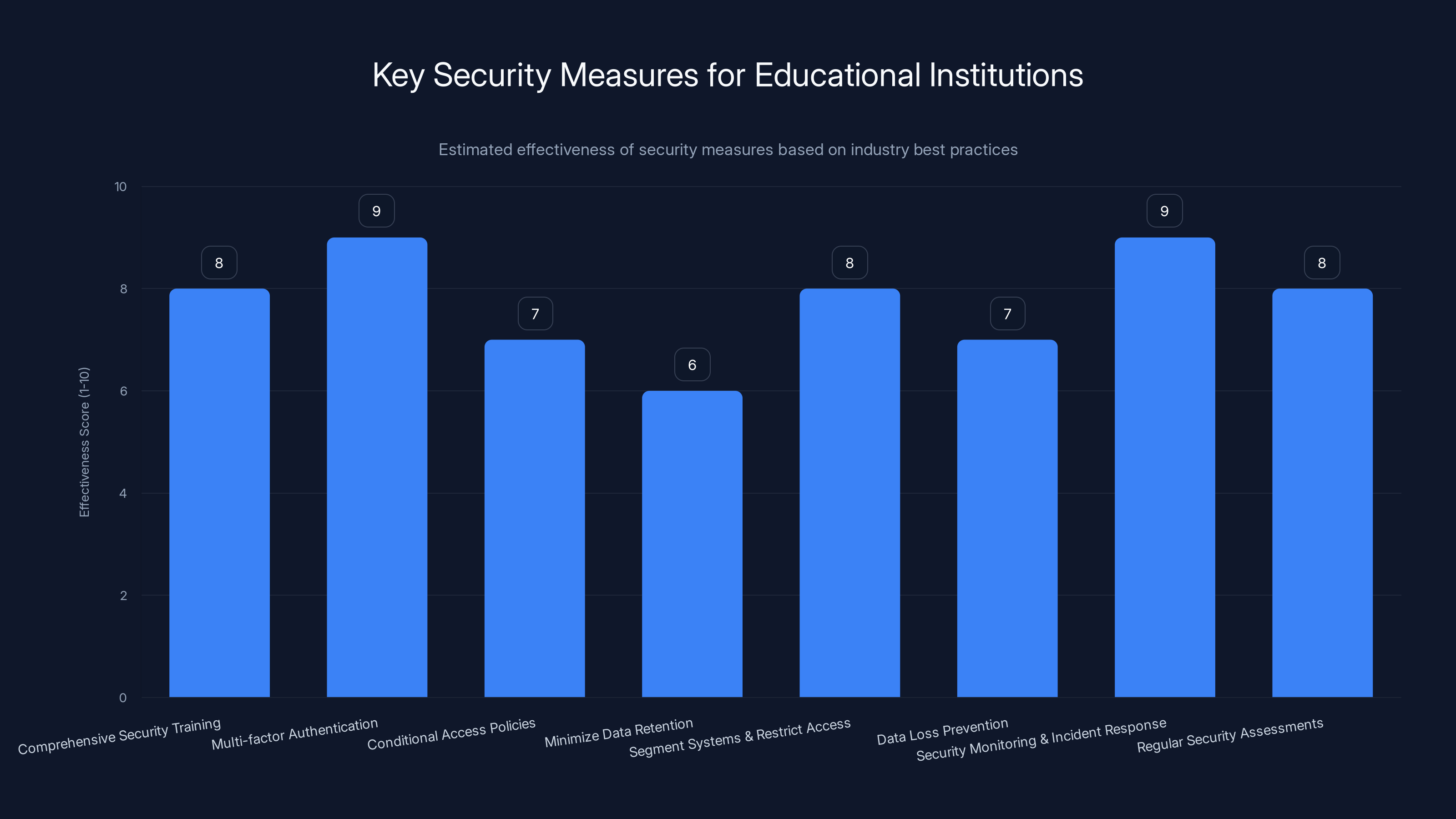

Multi-factor authentication and security monitoring are among the most effective measures, scoring 9 out of 10 in estimated effectiveness. Estimated data based on industry best practices.

What Happened at Harvard: The Voice Phishing Attack

Harvard's breach came through a different door, but arrived at the same destination: complete compromise of sensitive systems. The method was voice phishing, a surprisingly effective social engineering technique that relies on human psychology rather than technical vulnerabilities.

Here's how it likely worked: Someone called a Harvard employee, claiming to be from the IT support department. They might have used a spoofed number to make the call appear legitimate. They had just enough information to sound authentic—maybe they mentioned the employee's name, department, or a real system that the university uses.

The goal was simple but effective: trick the employee into either providing their login credentials or clicking a link that would capture those credentials. Voice phishing is effective because it creates a sense of urgency and authority. When someone calls claiming to be from IT support, most people's first instinct is to help them, not to be suspicious.

Once the attackers had legitimate credentials, they could log into the Alumni Affairs and Development systems directly. To the system's logs, they looked like a real employee. There was nothing technically suspicious about their login. They were inside.

The Alumni Affairs and Development systems contain some of the most sensitive information a university maintains. This is where donor records live—complete profiles of who has given money to the university, how much they gave, what they gave it for, and their contact information. Development officers use this information to cultivate relationships with major donors and secure significant gifts.

Compromising this system meant the attackers could see detailed giving histories, wealth indicators, contact information, and personal notes about donors that Harvard staff had compiled during their relationship-building efforts. It's the institutional memory of the development office, now in criminal hands.

The breach also exposed information about alumni spanning decades. A Harvard degree is a credential that opens doors throughout American society. The criminal underground is very interested in identifying wealthy, influential Harvard alumni and targeting them with sophisticated social engineering attacks. This data made that targeting trivial.

The Ransomware Negotiation: When Criminals Became Publishers

Unlike many breach scenarios, this one followed a somewhat predictable arc that's become increasingly common: theft, negotiation, and publication.

When the Shiny Hunters group first stole the data, they didn't immediately publish it. Instead, they used it as leverage. They contacted Harvard and UPenn and essentially said: "We have your data. Pay us in cryptocurrency, and we'll delete it and keep quiet."

This is the standard ransomware playbook. Steal data, extort money, delete files (or claim to). It's a criminal business model that has evolved significantly over the past few years. Early ransomware attacks focused on encrypting files and demanding payment for decryption keys. Modern attacks include data theft and extortion—what's called "double extortion."

One detail is particularly notable about this breach: no encryptors were deployed. The attackers didn't encrypt Harvard's or UPenn's systems. They didn't lock anyone out of their own data. They simply stole what they wanted and left. This suggests a sophisticated group that understood these institutions wouldn't respond to traditional ransomware demands but might respond to threatened publication of sensitive data.

Both institutions apparently decided not to pay. Universities face complex decisions when dealing with ransomware. Paying criminal organizations is ethically fraught. It funds future crimes. It signals that these tactics work. It might violate sanctions laws if the criminal group is in a sanctioned country. It could expose the institution to regulatory scrutiny.

So they didn't pay. And when they didn't pay, Shiny Hunters followed through on its threat. The group published the entire dataset on its dark web site, making it available to other criminals to download and exploit.

This is the new normal in data breaches. When negotiation fails, publication follows. And when data is published on dark web marketplaces, it spreads. Criminals download it, index it, and use it for years. That stolen Harvard and UPenn data will enable identity theft, phishing campaigns, and social engineering attacks for years to come.

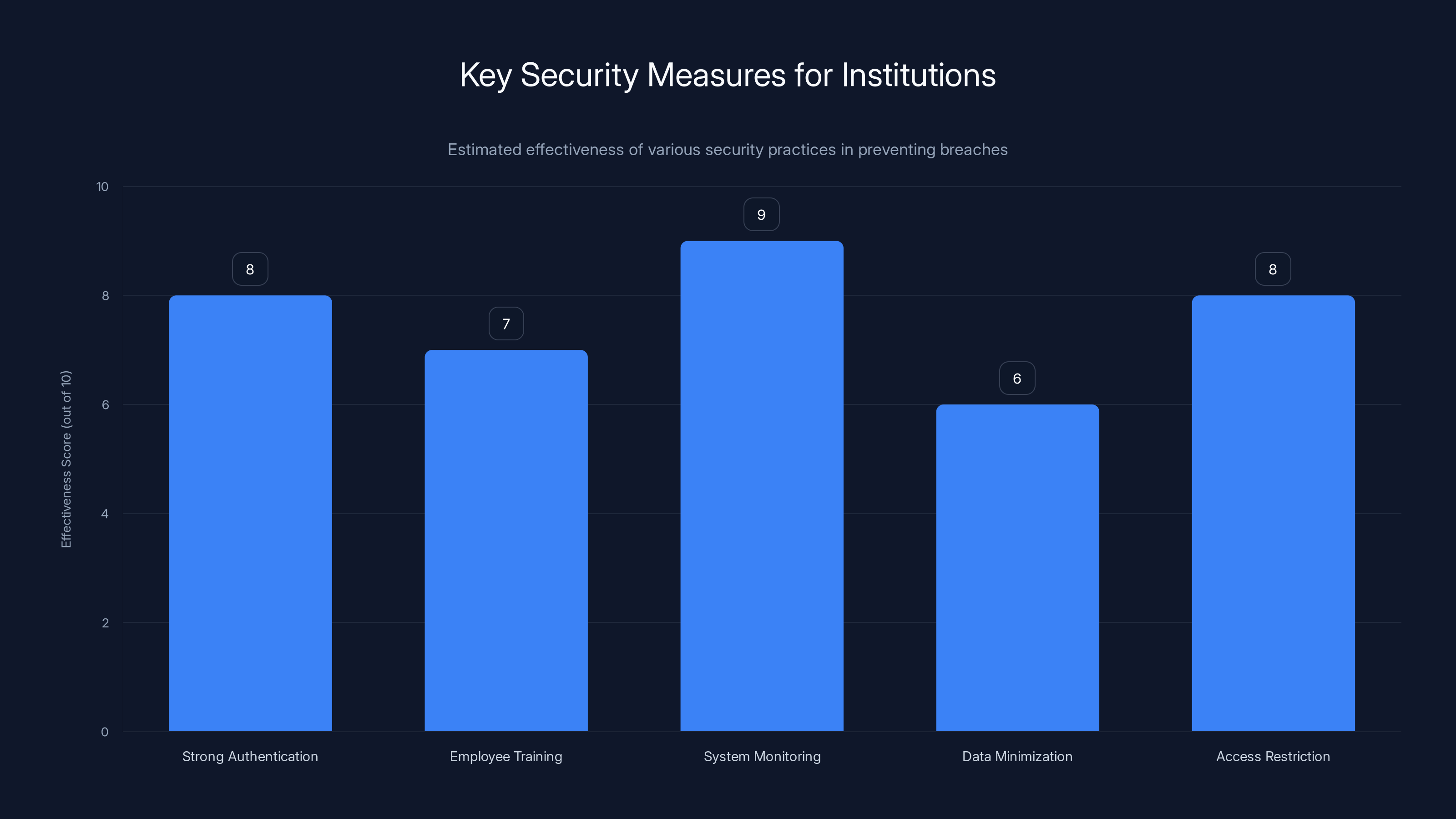

Implementing strong authentication and system monitoring are among the most effective measures to reduce the risk of data breaches. Estimated data based on common security practices.

Who Was Actually Affected: The Victims of the Breach

When we talk about Harvard and UPenn data breaches affecting "over a million people," it's important to understand who these people are and why their information matters.

The most obviously affected groups are current and former students. If you ever attended either institution, your information is likely in this stolen dataset. That includes undergraduate students, graduate students, professional students, and students who attended years ago. Student records contain names, addresses, phone numbers, birthdates, and potentially information about financial aid, housing, disciplinary history, and health information.

Alumni are affected even more broadly. Universities maintain alumni records for life. They track your graduation date, degree, major, and everything you've done since. If you graduated from Harvard or UPenn, even decades ago, your information is in this breach.

Donors and their families are heavily affected. If you've ever given money to either institution, your complete donor profile is likely in the stolen data. This includes donation amounts, dates, restrictions on how you wanted your gift used, and personal information the development office compiled about you during their cultivation efforts.

Staff and faculty members are affected. Both institutions employ thousands of people. Their personnel records, contact information, and work history are part of the breach.

But here's where it gets broader: family members. If you're a current student, your parents' contact information is probably in the database. If you're an alumnus, information about your spouse and children might be included. If you made a major gift, your entire family's information might be in the development office's CRM system.

The scope is staggering. We're not talking about a breach that affects a few thousand people. We're talking about over a million records that potentially represent several million individual people when you account for family connections.

Why does this matter? Because the information stolen is specifically valuable for targeted attacks. A criminal with access to this data knows:

- Who is likely to be wealthy (Harvard and UPenn alumni and donors are generally affluent)

- Where they live (home addresses in the dataset)

- How much they've given to charity (donation history shows wealth indicators)

- How they identify (demographic information including religion and sexual orientation)

- Their family relationships

- Their educational background

With this information, criminals can:

- Launch sophisticated phishing attacks targeted to specific individuals using personal details

- Commit identity theft using birthdates and addresses

- Execute romance scams using family information and wealth indicators

- Perform targeted social engineering using specific knowledge of their personal details

- Conduct business email compromise attacks knowing institutional affiliations and relationships

- Target harassment campaigns using demographic information and personal identifiers

The Technical Vulnerabilities: Why This Happened

Both of these breaches exploited fundamental vulnerabilities in how institutions manage access and authentication. Understanding these vulnerabilities is important because they're not unique to Harvard and UPenn. They exist at thousands of organizations.

The first vulnerability is SSO dependency without proper safeguards. Modern enterprises use SSO systems like Okta, Azure AD, or institutional SSO implementations because they improve user experience and (theoretically) improve security. But they create a critical single point of failure. When one account is compromised, the attacker gets access to everything that account can access.

Proper SSO implementation should include:

- Adaptive authentication that triggers additional verification when login patterns change

- Geolocation-based restrictions that alert when a user logs in from an unusual location

- Device trust verification that requires the login to come from a known device

- Behavioral analytics that detect unusual access patterns

- Conditional access policies that restrict what a compromised account can do

Based on the scope of access the attackers achieved, it appears these safeguards were either not implemented or not properly configured.

The second vulnerability is insufficient employee security training. The Harvard breach came through voice phishing. That's a social engineering attack that works because employees aren't trained to be suspicious when someone in authority (IT support) calls them asking for credentials.

Even basic security training should teach employees:

- Never provide credentials over the phone, even if the caller claims to be from IT

- Always verify requests through independent channels

- Legitimate IT support doesn't call asking for passwords

- Be suspicious of urgency, which is a classic social engineering tactic

- Know your institution's verification procedures and always use them

The third vulnerability is excessive data collection and retention. Both universities maintained sensitive demographic information—race, religion, sexual orientation—in databases that were apparently accessible via compromised credentials. While institutions need to collect demographic data for legitimate purposes like diversity tracking and alumni outreach, maintaining it in systems accessible to compromised credentials creates unnecessary risk.

Data minimization is a core security principle: collect only what you need, keep it only as long as you need it, and restrict access to only those who need to see it. Universities generally do a poor job of this.

The fourth vulnerability is inadequate access controls. If one compromised SSO account gave access to Salesforce, Qlik, SAP, and Share Point simultaneously, the access controls were too permissive. Proper role-based access control would restrict access to only the data that person actually needed to do their job.

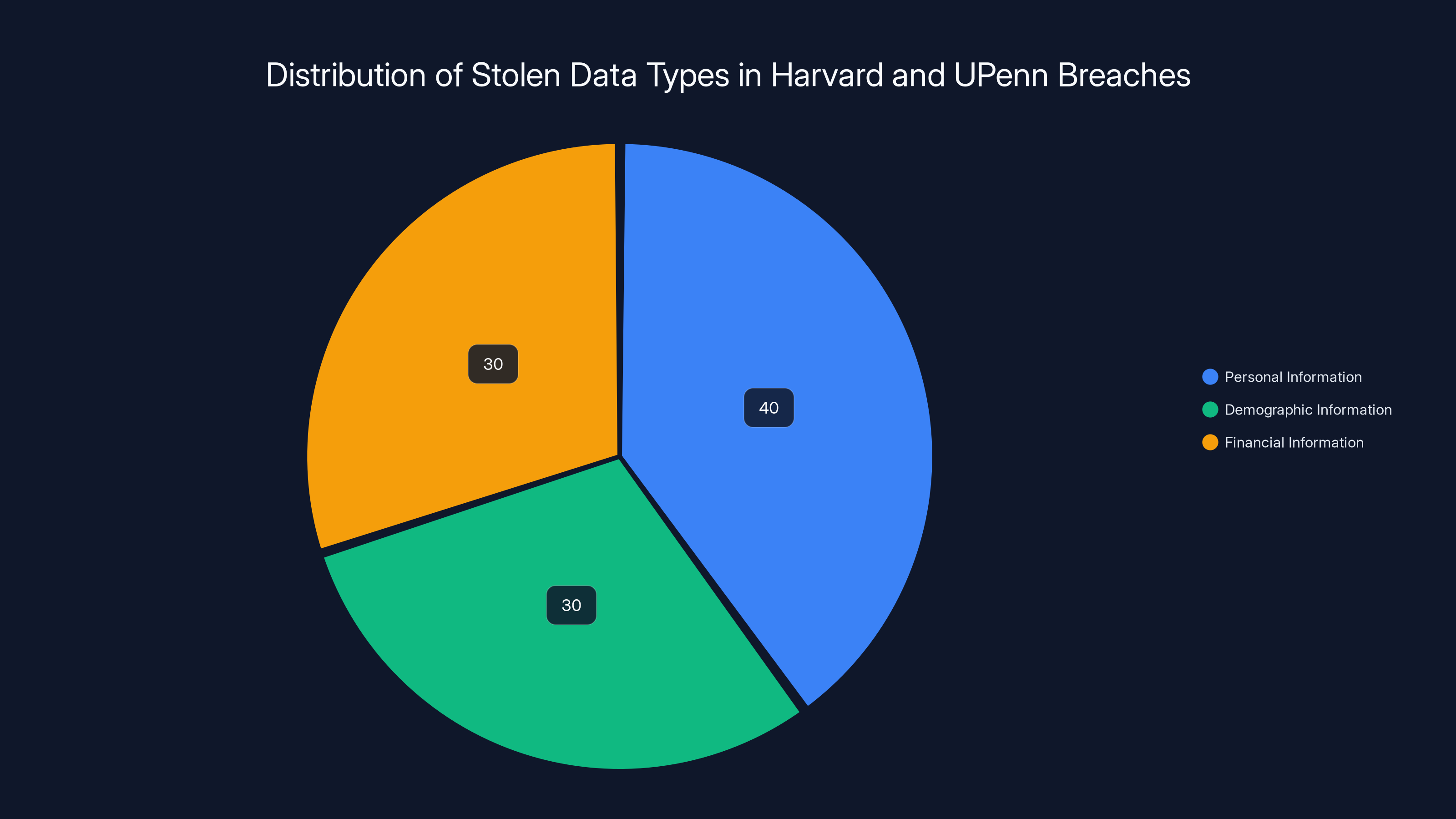

Estimated data shows that personal details and contact information make up the largest portions of the stolen records, highlighting the breadth of sensitive data compromised.

The Fallout: Legal, Regulatory, and Reputational Consequences

When a breach this large happens at an institution this prominent, the consequences extend far beyond the immediate embarrassment of having data stolen.

Regulatory consequences are substantial. Both universities must comply with notification laws in every state where affected individuals live. State data breach notification laws typically require notification within 30-60 days of discovering the breach. This means sending notifications to over a million people, which is expensive and complex.

They may also face investigations from state attorneys general. New York, for example, has particularly aggressive data protection regulations. If significant portions of the affected population are in New York, the New York Attorney General might investigate. Similar state-level investigations could follow in California, Illinois, and other states with strong data protection laws.

Federal investigation is also possible. The FBI and Secret Service investigate major data breaches, particularly those involving educational institutions. These investigations don't necessarily result in fines, but they're time-consuming and can lead to prosecution if criminal activity is found within the institution.

Financial consequences are severe. Both universities will face:

- Breach notification costs, including mailing and call center costs

- Credit monitoring services, which universities typically offer affected individuals for 2-3 years

- Legal fees for handling notifications, regulatory requests, and potential litigation

- Forensic investigation costs to determine exactly what was accessed and by whom

- Cybersecurity upgrades to prevent recurrence

- Insurance claims if cyber insurance is in place (though policies often have exclusions and limitations)

For a breach of this scale, total costs could easily exceed

Class action lawsuits are virtually inevitable. Affected individuals can sue both universities for negligence, breach of fiduciary duty, and failure to protect their personal information. These lawsuits rarely result in large individual settlements (the plaintiff usually ends up with $25-200 per person), but they're expensive to defend and create ongoing liability.

Reputational damage may be the most significant long-term consequence. Harvard and UPenn are among the world's most prestigious universities. Part of their value proposition to students, donors, and stakeholders is that they're world-class institutions with world-class operations. A breach this large undermines that narrative.

Alumni—particularly wealthy donors—are likely to be scrutinous about where they direct future gifts. Students might reconsider attending a school where their data isn't protected. Prospective students might be concerned about privacy. Faculty might worry about institutional competence.

For years to come, these breaches will be referenced whenever the institutions are discussed in media coverage. They'll be mentioned in comparisons to peer institutions. They'll affect how external parties perceive institutional competence.

How the Stolen Data Gets Used: The Criminal Supply Chain

Understanding what happens to stolen data after it's published helps explain why this breach is so damaging beyond the immediate institutions affected.

When Shiny Hunters published the stolen data on their dark web site, they didn't just upload it and leave. They made it accessible, searchable, and valuable to other criminals. The data enters a criminal supply chain that looks something like this:

First stage: The data is indexed and catalogued. Criminal marketplaces create searchable interfaces where other criminals can look up individuals by name, address, or other identifiers. They might create tools that allow searching and exporting subsets of the data.

Second stage: Specialized criminal groups purchase or access portions of the data for specific purposes. A phishing gang might purchase a list of email addresses and organizational affiliations. An identity theft ring might focus on individuals with high net worth indicators. A harassment group might target individuals based on demographic information.

Third stage: The data is weaponized. Phishing emails are sent using the legitimate-looking institutional affiliations. Social engineering attacks target individuals using personal details. Identity theft attempts use birthdates and addresses. Harassment campaigns weaponize demographic information.

Fourth stage: The compromised data becomes part of other breach datasets. When someone else is hacked, this Harvard/UPenn data might be combined with data from other sources to create even more valuable consolidated datasets.

This supply chain operates on a timeline of months and years. The impact of this breach won't be fully known for years. People affected might not realize they've been targeted by identity theft or fraud until they check their credit report months or years from now.

Estimated data shows that personal, demographic, and financial information were equally targeted in the breaches. Estimated data.

Prevention and Response: What Organizations Should Learn

While Harvard and UPenn have already learned painful lessons, other institutions can take steps to avoid similar breaches.

For universities and educational institutions:

-

Implement comprehensive security training that goes far beyond annual checkbox training. Make it role-specific, ongoing, and include simulated phishing campaigns to identify vulnerable employees.

-

Deploy multi-factor authentication universally. Don't make it optional. Every account should require something you know (password), something you have (authenticator app or hardware key), and ideally something you are (biometric). This prevents compromised credentials from being sufficient for unauthorized access.

-

Implement conditional access policies that trigger additional authentication when suspicious activity is detected. Login from an unusual location? Require additional verification. Login from an unusual device? Require additional verification.

-

Minimize data collection and retention. If you don't need to store demographic information in your CRM, don't store it there. If you don't need to keep data for 20 years, don't keep it. Less data = less risk.

-

Segment systems and restrict access. Don't give every employee access to every system. Use role-based access control. A receptionist shouldn't be able to access the database of donor giving amounts. A student services employee shouldn't have access to personnel records.

-

Implement data loss prevention (DLP) that monitors and prevents unauthorized copying of sensitive information. This can catch compromised accounts that are actively exfiltrating data.

-

Invest in security monitoring and incident response. Deploy security information and event management (SIEM) tools that can detect unusual patterns of activity. Know what normal looks like so you can identify abnormal.

-

Conduct regular security assessments including vulnerability scanning, penetration testing, and social engineering assessments. Find and fix problems before attackers do.

For individuals affected by this breach:

-

Consider a credit freeze with all three credit bureaus (Equifax, Experian, Trans Union). This prevents criminals from opening accounts in your name.

-

Monitor credit reports closely. Check your credit reports at annualcreditreport.com (the official free credit report site). Look for accounts or inquiries you didn't authorize.

-

Enable account monitoring alerts with your bank and credit card companies. Many offer free monitoring that alerts you to unusual activity.

-

Be suspicious of unsolicited contact. If someone calls claiming to be from your bank or any institution asking to verify information, hang up and call the institution directly using a number you look up yourself.

-

Use unique, strong passwords for important accounts. Password managers like Bitwarden or 1 Password make this practical.

-

Enable two-factor authentication on any important account that offers it. This provides a layer of protection even if passwords are compromised.

-

Consider identity theft protection services, particularly if you had significant assets or donated substantially to either institution.

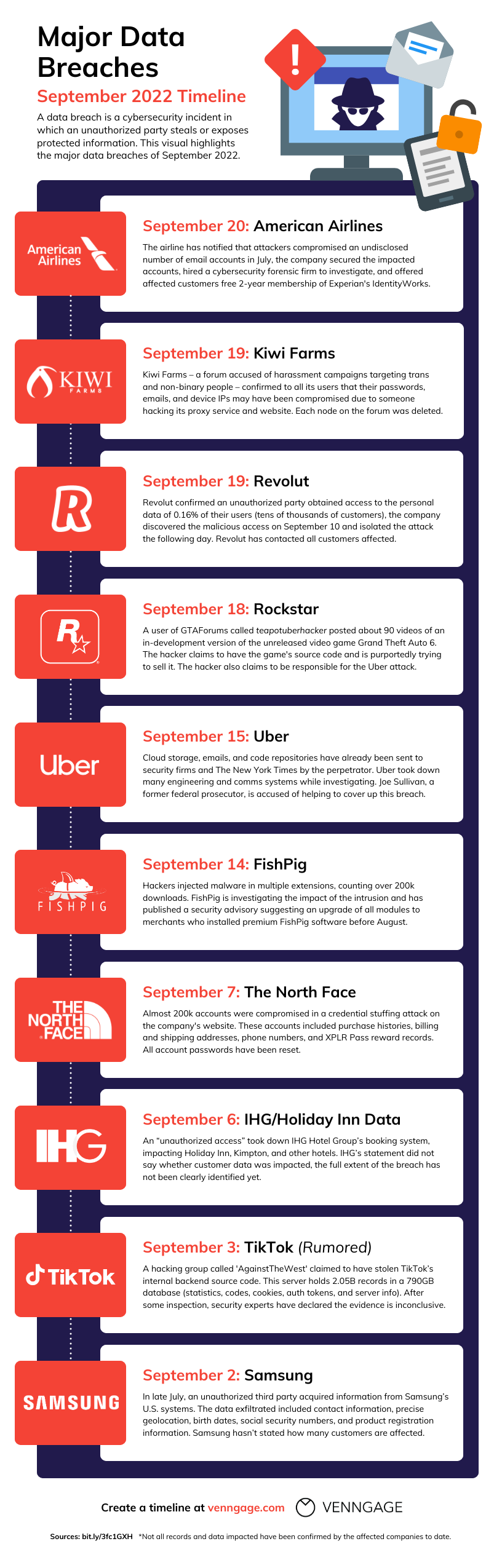

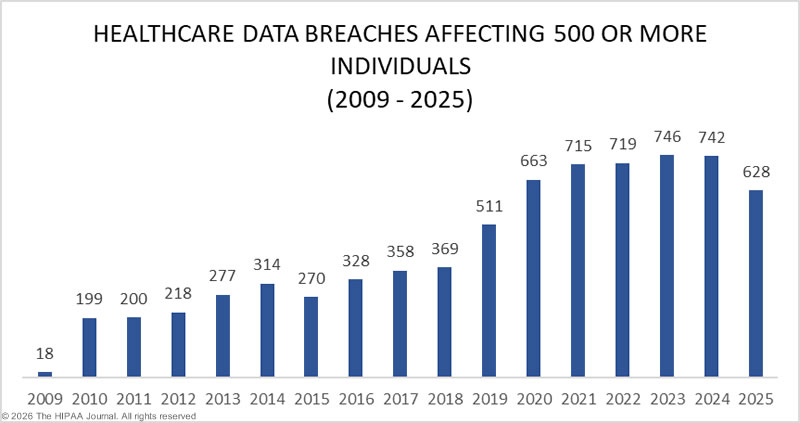

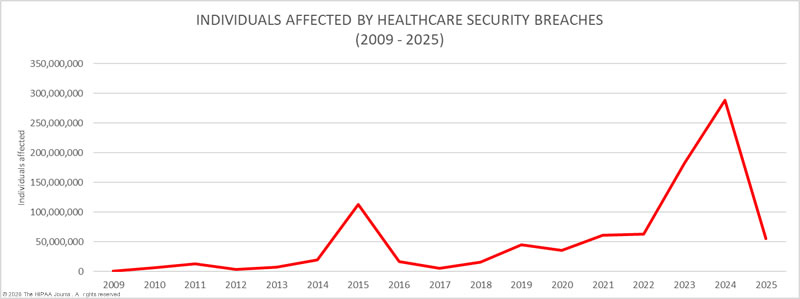

The Broader Trend: Educational Institutions as Targets

This isn't an isolated incident. Educational institutions have become increasingly attractive targets for cybercriminals in recent years. There are several reasons why:

Valuable data: Universities maintain treasure troves of personal information. Students, alumni, donors, faculty, and staff all have their data on institutional systems. For many individuals, the institution has been collecting and maintaining their information for decades.

Wealth indicators: University alumni—particularly from prestigious institutions—are statistically likely to be wealthy. Criminals targeting universities are targeting a population that's disproportionately affluent and potentially vulnerable to financial fraud.

Trust and authority: University communications are trusted. An email appearing to come from your university is likely to be opened and acted upon. This makes phishing campaigns more likely to succeed.

Open research environment: Universities pride themselves on being open, collaborative environments. This creates an inherent tension with cybersecurity, which requires segmentation and restriction.

Distributed workforce: Universities employ thousands of people working from various locations. This distributed workforce is harder to monitor and manage than a traditional corporate environment.

Complex technical infrastructure: Universities operate complex IT environments with legacy systems, custom applications, and diverse technologies all connected together. This complexity creates more potential attack surface.

Over the past few years, we've seen breaches at numerous educational institutions. Each breach exposes patterns and techniques that other criminals learn from and replicate. The Harvard and UPenn breaches will likely inspire copycat attacks at other prestigious universities.

What's Next: Regulatory and Market Changes

Large breaches at prominent institutions tend to trigger regulatory responses. We can expect:

Stronger state-level regulations: States are increasingly passing data protection laws. More states will likely follow the lead of California's CCPA and other progressive jurisdictions in requiring organizations to secure personal information and provide individuals with rights over their data.

Federal legislation: While the US still lacks comprehensive federal data protection legislation, breaches of this magnitude apply pressure on Congress to act. We might see federal standards for data breach notification, security requirements, or individual rights.

Educational institution-specific regulations: Some states might pass regulations specifically addressing higher education cybersecurity. These could mandate minimum security standards, incident reporting requirements, and data protection measures.

Insurance market changes: Cyber insurance premiums are already increasing as insurers see the scale and frequency of breaches. Institutions with poor security practices will find insurance more expensive or unavailable.

Accreditation requirements: Higher education accreditation bodies might impose cybersecurity requirements on member institutions. This could drive adoption of minimum security standards across American universities.

FAQ

What personal information was stolen in the Harvard and UPenn breaches?

The stolen data includes names, home addresses, dates of birth, phone numbers, donation histories, estimated net worth, and demographic information including race, religion, and sexual orientation. Students, alumni, donors, faculty, staff, and family members of these groups are affected.

How did the hackers gain access to Harvard and UPenn's systems?

UPenn's breach occurred through a compromised employee single sign-on (SSO) account, which gave attackers access to multiple connected systems including Salesforce, Qlik, SAP, and Share Point. Harvard's breach came through voice phishing (vishing) where someone called an employee impersonating IT support and obtained their credentials.

How many people are affected by these breaches?

Shiny Hunters claims over one million records were stolen. This likely represents several million individual people when accounting for family connections and multiple records per person across different systems.

What should affected individuals do to protect themselves?

Affected individuals should consider placing a credit freeze with the three major credit bureaus, monitoring credit reports regularly, enabling two-factor authentication on important accounts, and being suspicious of unsolicited contact. Credit monitoring services offered by the universities are worth using.

What will the consequences be for Harvard and UPenn?

Both universities will face substantial costs for breach notifications, credit monitoring, forensic investigations, legal fees, and cybersecurity upgrades. They'll face regulatory investigations, potential fines, class action lawsuits, and significant reputational damage.

Why didn't the universities pay the ransom demand?

Universities face complex decisions about ransom payment. Paying funds criminal organizations, may violate sanctions laws, exposes them to regulatory scrutiny, and signals that extortion tactics work. Both institutions apparently decided not to pay, after which Shiny Hunters published the data.

How could these breaches have been prevented?

Better prevention requires comprehensive security training, multi-factor authentication, conditional access policies, data minimization, role-based access controls, security monitoring, and regular security assessments. The vulnerabilities exploited are well-known and preventable with proper implementation.

What's the timeline for impact from this breach?

The full impact will unfold over years. Immediate consequences include notifications and legal liability. Medium-term impacts include regulatory action and civil litigation. Long-term impacts include identity theft, fraud, and social engineering attacks that may target victims years from now.

Are other universities at risk?

Yes. Educational institutions remain attractive targets for cybercriminals. Other universities likely have similar vulnerabilities in their SSO systems, employee training, and security practices. Similar breaches could occur at other prestigious institutions.

What should other organizations learn from these breaches?

Organizations should implement comprehensive security training, deploy multi-factor authentication, minimize data collection and retention, segment systems and restrict access, implement data loss prevention, invest in security monitoring, and conduct regular security assessments. Prevention is far less expensive than responding to a breach.

Conclusion: Learning from Institutional Failure

The Harvard and UPenn data breaches represent a significant failure in institutional cybersecurity. These aren't small regional universities with limited resources. These are among the world's most prestigious educational institutions with access to substantial funding and expertise. Yet their security practices were inadequate.

The breaches expose a pattern that extends far beyond these two institutions. Many organizations—educational, governmental, and corporate—prioritize convenience over security. They implement systems like SSO that improve user experience but create single points of failure. They defer security training. They don't minimize data collection. They don't implement multi-factor authentication universally.

When breaches occur, the consequences are severe. Over a million people's personal information is now in the hands of criminals. The institutions face tens of millions of dollars in costs. Affected individuals face years of increased risk from identity theft, fraud, and social engineering attacks.

The responsibility now lies with both institutions to respond appropriately and with other organizations to learn from what happened. For those affected, the immediate priorities are credit monitoring, security awareness, and protecting accounts from misuse.

For organizations considering their own security posture, the message is clear: the cost of prevention is trivial compared to the cost of response. Implement the basics. Require strong authentication. Train employees. Monitor systems. Don't keep data you don't need. Restrict access appropriately. These steps won't make an organization immune to breaches, but they significantly reduce risk and limit the damage when breaches occur.

The question now is whether this breach—and others like it—will finally drive meaningful change in how institutions approach security. History suggests institutional change is slow. But the scale of this breach and the prominence of the affected institutions might create the pressure necessary for broader adoption of security best practices.

Until then, individuals need to take security seriously. Assume your data has been breached. Use strong unique passwords. Enable two-factor authentication. Monitor credit reports. Be suspicious of unsolicited contact. The institutions might eventually get security right, but in the meantime, personal responsibility is your best defense.

Key Takeaways

- ShinyHunters hackers stole over 1 million records from Harvard and UPenn, including personal details, donation histories, and demographic information

- Breaches resulted from compromised SSO credentials and voice phishing attacks targeting institutional employees

- Failed ransom negotiations led hackers to publish all stolen data on dark web marketplaces, making it accessible to criminal networks

- Affected individuals face years of heightened risk from identity theft, fraud, and targeted social engineering attacks

- Both universities face estimated costs of $10-50 million for breach response including notifications, credit monitoring, legal fees, and security upgrades

- The breaches highlight critical vulnerabilities in educational institutional cybersecurity that exist at thousands of organizations

Related Articles

- Harvard & UPenn Data Breaches: Inside ShinyHunters' Attack [2025]

- Substack Data Breach Exposed Millions: What You Need to Know [2025]

- Password Security Guide: Why Strong Credentials Matter in 2025

- 8.7 Billion Records Exposed: Inside the Massive Chinese Data Breach [2025]

- Apple Pay Unusual Activity Scam: How to Spot Fake Messages [2025]

- Reclaim Your Browser: Best Ad Blockers & Privacy Tools [2025]

![Harvard and UPenn Data Breaches: What You Need to Know [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/harvard-and-upenn-data-breaches-what-you-need-to-know-2025/image-1-1770298575510.jpg)