How AI Is Accelerating Scientific Research Globally [2025]

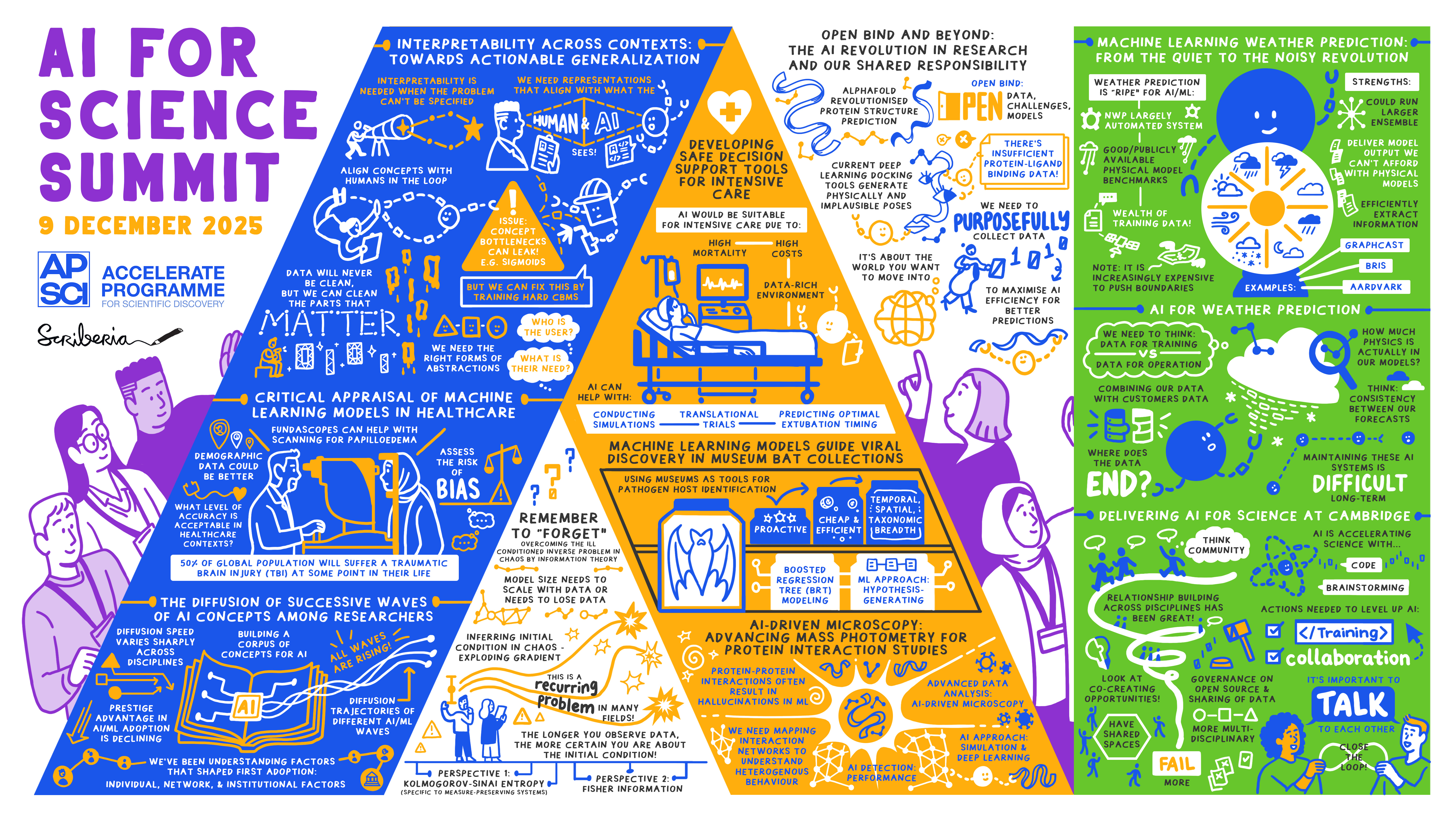

Something's shifted in how science gets done. Not dramatically overnight, but steadily, measurably. Researchers aren't just experimenting with AI anymore—they're building it into their actual workflows. Math proofs that used to take months. Physics simulations that were cost-prohibitive. Protein designs that required years of iteration. Now there's AI in the loop, and the pace has picked up.

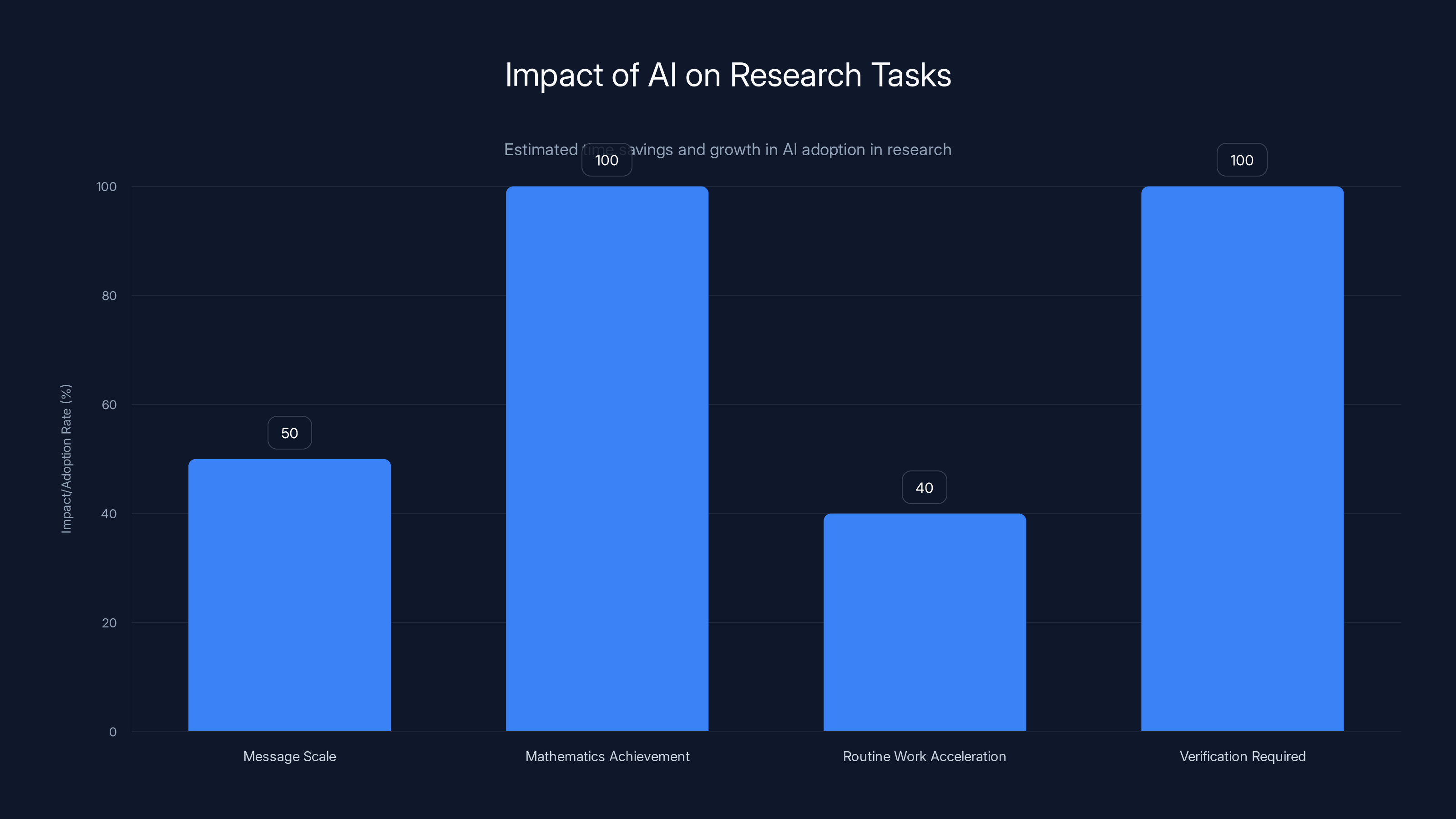

This isn't speculation or marketing hype. OpenAI released data showing that 8.4 million messages are sent every week on science and mathematics topics alone. That's roughly 1.3 million researchers, globally, using AI as a thinking partner. And this usage has grown nearly 50% in just the past year.

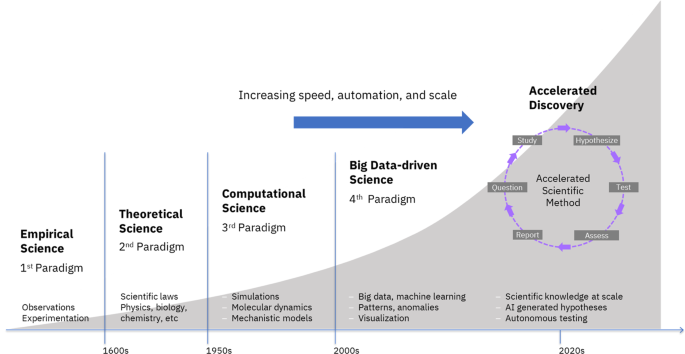

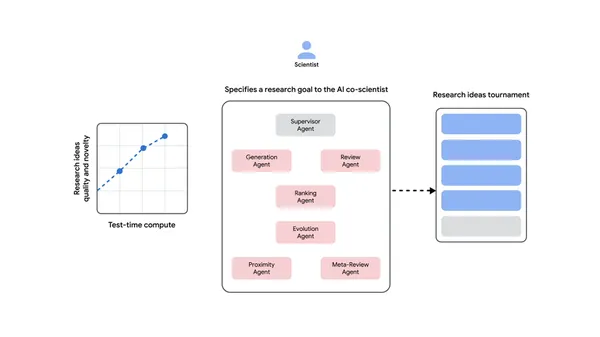

Here's what makes this different from previous tech cycles. When Excel revolutionized finance, it was mostly about faster spreadsheets. When cloud computing transformed startups, it was about cheaper infrastructure. But AI in research? It's reshaping the fundamental way discovery happens. It's not replacing scientists—it's giving them a collaborator that thinks differently, catches mistakes, and suggests connections they might have missed.

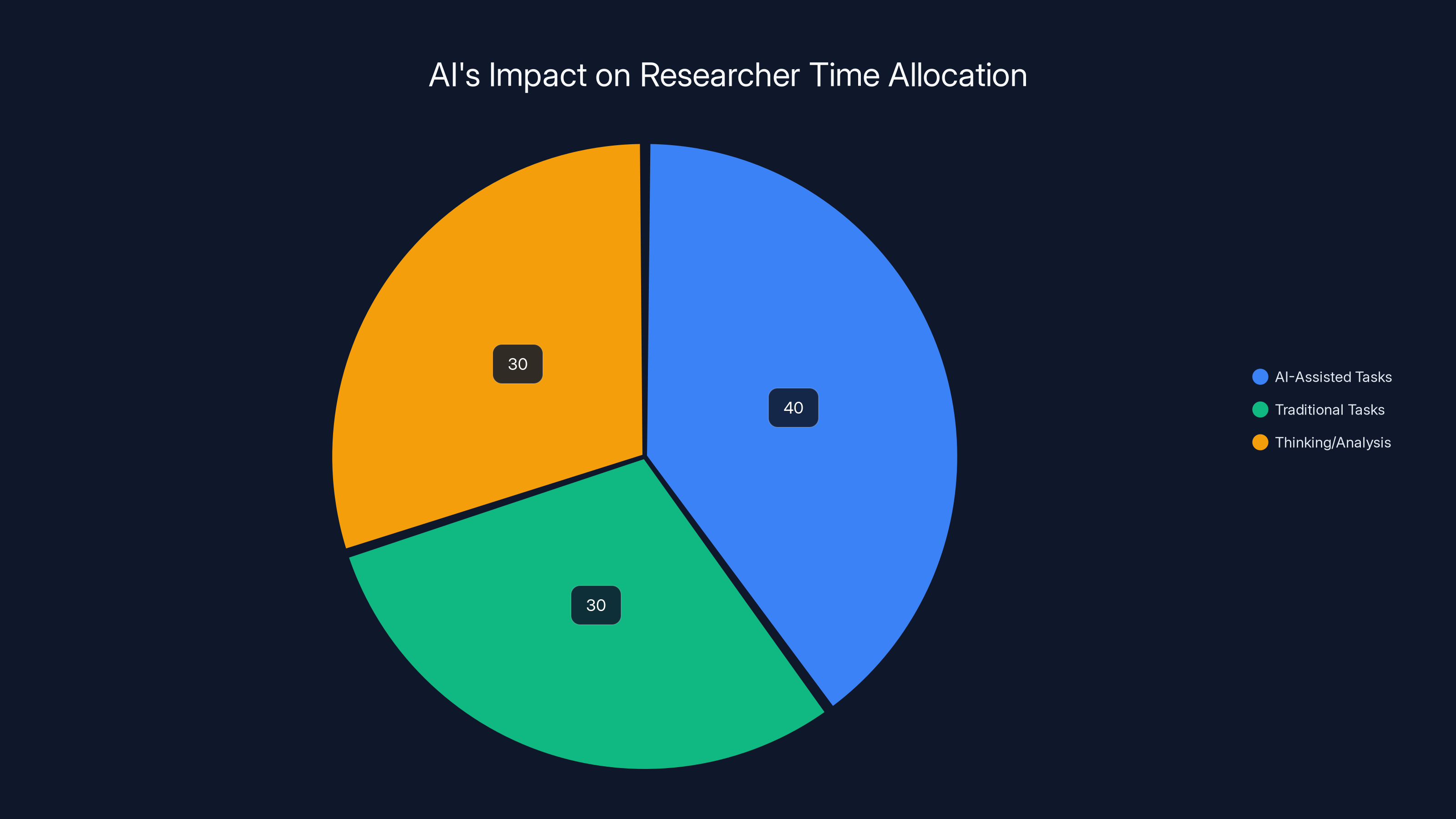

The implications are profound. Science moves slowly by design. Peer review, verification, replication—these things take time because they should. But the routine parts? The grunt work that delays actual thinking? That's where AI is changing the game. Coding, literature review, experiment planning, simulation support, data wrangling—all the tasks that eat up 40-50% of a researcher's time. AI handles those differently, which means researchers get more time for actual thinking.

But here's where we need to be careful. The headlines want to tell you that AI solved a math problem humanity couldn't crack. That's not quite what's happening. What's actually happening is subtler and more interesting. AI is identifying connections. It's automating verification. It's suggesting paths forward. And yes, sometimes it catches things humans miss. But the final validation, the confirmation, the decision-making—that's still human.

Let's dig into what's actually happening in laboratories and research institutes worldwide. Because the data tells a story that's more nuanced than "AI is doing science now."

The Scale of AI in Research: Numbers That Matter

OpenAI's research claim sits on solid ground. 8.4 million messages per week isn't a small number, but it's also worth understanding what that actually represents. That's roughly 440 million messages annually on science and math topics from about 1.3 million users. For perspective, that's approaching the population of a small country, all actively using AI for research.

The growth rate matters more than the absolute number. Nearly 50% year-over-year growth suggests we're past the "interesting experiment" phase. This is becoming embedded in how research actually happens. Universities, private research institutes, biotech companies, materials science labs—they're all factoring AI into their pipelines.

What's particularly interesting is the distribution. Not all researchers use AI equally. Graduate students and postdocs—the people doing the actual daily research—represent the bulk of this usage. These are people deep in the work, trying to move projects forward. They're not playing with AI on weekends. They're using it because it saves them tangible time on work that actually matters.

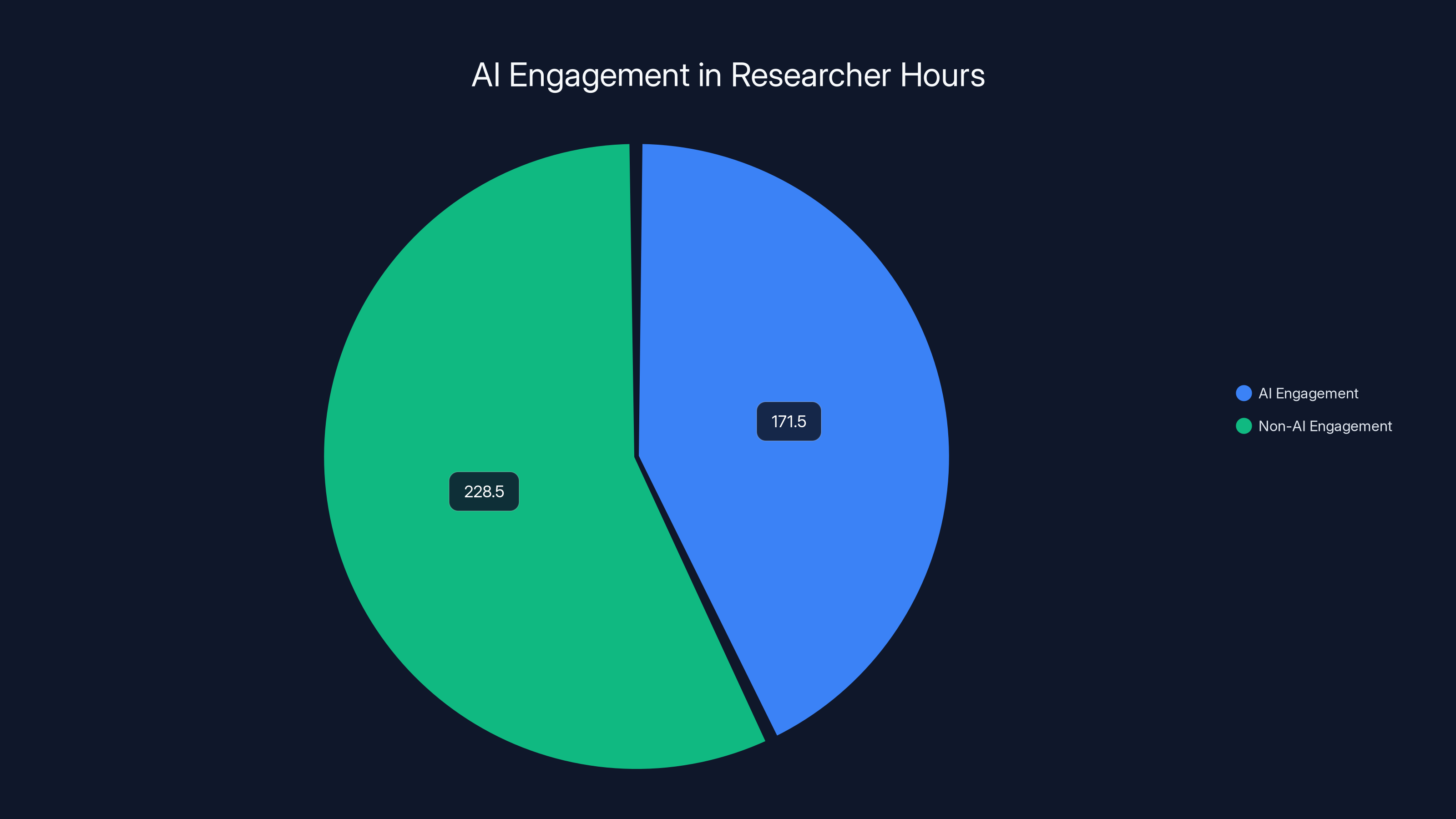

The weekly message count translates to something concrete. If each message represents a query taking 5-10 minutes to execute and review, that's roughly 2.2 to 4.4 million researcher-hours weekly being spent in active collaboration with AI. In a year, that's between 114 million and 229 million researcher-hours. For context, there are roughly 8 million active researchers globally. If they work 50 weeks a year, that's 400 million researcher-hours available annually. AI is consuming 28-57% of that, at least in terms of active engagement.

These numbers flatten out when you think about it. Most researchers aren't using AI for everything. But the ones who are, the ones in the early-adopter category, are using it intensively.

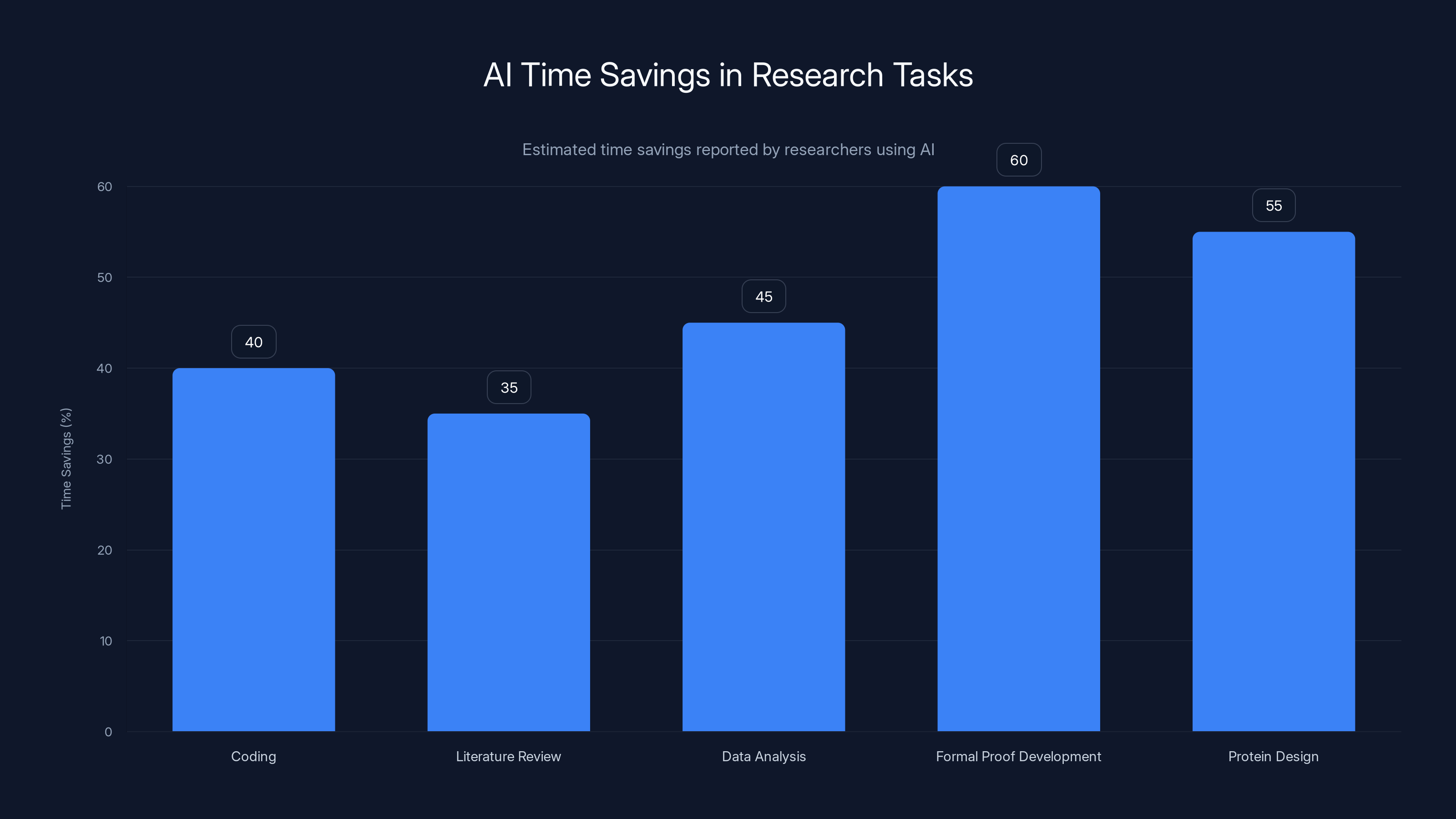

Researchers report 30-50% time savings on routine tasks like coding and data analysis, with even higher savings for specialized tasks like formal proof development and protein design. (Estimated data)

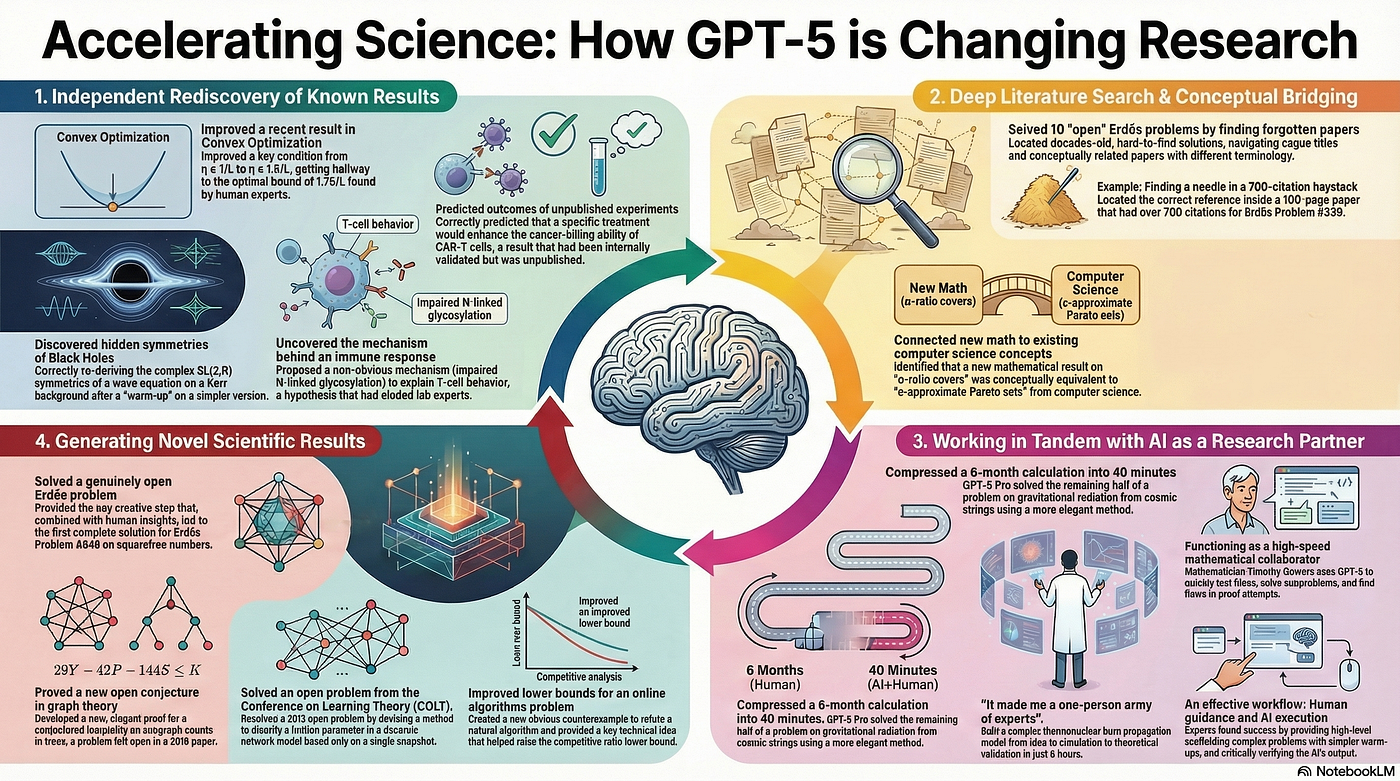

Mathematics: Where AI Proves Its Capability

Mathematics is where OpenAI's claims become most verifiable. Numbers either work or they don't. Proofs either check out or they don't. There's no middle ground, no interpretation. This makes math the most honest benchmark for AI's research capability.

OpenAI claims that their GPT-5.2 models achieved gold-level results at the 2025 International Mathematical Olympiad. For context, that's the competition where the world's top high school mathematicians struggle. Achieving gold means solving nearly all problems correctly, fast, under pressure. The fact that an AI system can do this is notable. The fact that it's doing it reliably is more important.

But here's the interesting detail that gets lost in headlines. The model doesn't just solve problems. It follows long reasoning chains. It checks its own work. It can operate within formal proof systems like Lean, which is a computer language specifically designed for mathematical verification. This matters because Lean doesn't accept approximate answers or clever shortcuts. Either your proof is valid or it isn't.

The Frontier Math benchmark tells another story. This is a newer benchmark designed specifically to test whether AI systems can handle novel mathematical problems that human mathematicians are actively working on. OpenAI claims "partial success" here, which is honest language. The model doesn't crack these problems completely, but it makes progress. It suggests approaches. It identifies sub-problems that might be solvable. Sometimes it's right. Sometimes it confidently suggests paths that don't lead anywhere.

The real kicker is the Erdős problem angle. For decades, certain mathematical problems have resisted solution despite attracting brilliant minds. Erdős himself offered monetary prizes for solutions, and those prizes remain unclaimed. OpenAI claims their systems have contributed to solutions connected to these open problems, with human mathematicians confirming the results.

Now, this doesn't mean AI generated entirely new mathematical thinking. What it means is something more practical. The AI recombined known ideas, identified connections across fields that specialists might have missed, suggested approaches worth formalizing. Then humans took it from there. They verified it. They confirmed it was actually a contribution.

This is the pattern that repeats. AI accelerates verification and proof discovery by suggesting what to check, what connections matter, what might be worth formalizing. The human mathematician still does the heavy thinking about whether this approach is actually novel or just a clever rearrangement.

Estimated data shows significant savings from AI tools, with individual researchers saving

Physics Simulations: From Theory to Verification

Physics labs are using AI differently than mathematicians. For a physicist, the problem isn't usually proving something in the abstract sense. It's understanding how physical systems behave, predicting outcomes, and designing experiments. That's where AI becomes genuinely useful.

Physics laboratories are integrating AI across their entire workflow. That means combining simulations, experimental logs, documentation, and control systems into a unified pipeline. A physicist runs an experiment. AI logs the results. AI relates those results to simulations. AI flags when something unexpected happened. AI suggests what to adjust for the next run.

This is different from AI solving a physics problem in theory. This is AI becoming part of the experimental apparatus itself. It's handling bookkeeping that used to take hours. It's spotting correlations in datasets that humans would miss because the dataset is too large to visualize easily. It's maintaining context across dozens of experiments spanning weeks.

Theoretical exploration is another angle. A physicist has an idea. They want to know if it's worth pursuing. Running a full simulation might take days. Asking an AI to outline the physics, identify potential issues, suggest which parameters matter most—that takes minutes. Does the AI always get it right? No. But it gets you 80% of the way there in 5% of the time. You then spend the remaining 95% of time on the parts that actually need precision.

Graduate student perspective here matters. A physics Ph.D. student is typically simulating complex systems. Electromagnetic fields, particle interactions, fluid dynamics—these involve massive parameter spaces. Running full simulations means waiting for computational results. AI can explore the landscape faster, suggest which areas are most worth simulating precisely, help interpret why results turned out the way they did.

One specific capability stands out. AI can integrate multiple types of documentation. Your experimental log, your simulation parameters, your published papers on similar systems, your lab notes on what's failed before—AI can cross-reference all of that simultaneously. Humans can't do that in real time. We have to flip between documents, remember context, manually connect dots. AI does that in microseconds.

The catch is that AI's intuitions about physics are learned from existing publications and datasets. If your system is genuinely novel, if you're working at the frontier where the model was never trained on similar systems, AI starts making mistakes. But as a tool for staying in the middle of the distribution? It's phenomenally useful.

Biology and Chemistry: Specialized AI for Complex Systems

Biology throws a wrench into the pure AI-solves-everything narrative. Biological systems are absurdly complex. A protein folds in three-dimensional space based on amino acid interactions. The fold determines function. Predict the fold, potentially design a protein that does what you want. Simple, right? Except biology doesn't scale linearly. Small changes cause unexpected cascades.

This is where researchers are using hybrid approaches. They don't ask a general-purpose language model to predict protein structures directly. That's a recipe for confident nonsense. Instead, they pair large language models with specialized tools. Graph neural networks that understand protein topology. Protein structure predictors trained on known folding patterns. Physics simulators that verify whether a proposed fold makes thermodynamic sense.

The general-purpose AI handles high-level reasoning. It reads research papers on protein design. It understands the goal you're trying to achieve. It suggests design principles based on knowledge of how other proteins work. Then the specialized tools verify whether those suggestions actually produce valid structures.

Chemistry follows a similar pattern. Chemical reactions involve quantum mechanical interactions that are computationally expensive to simulate precisely. But they're also well-described by training models on existing reaction data. So researchers use AI to suggest likely products and pathways, then use more precise but slower tools to verify the chemistry actually works.

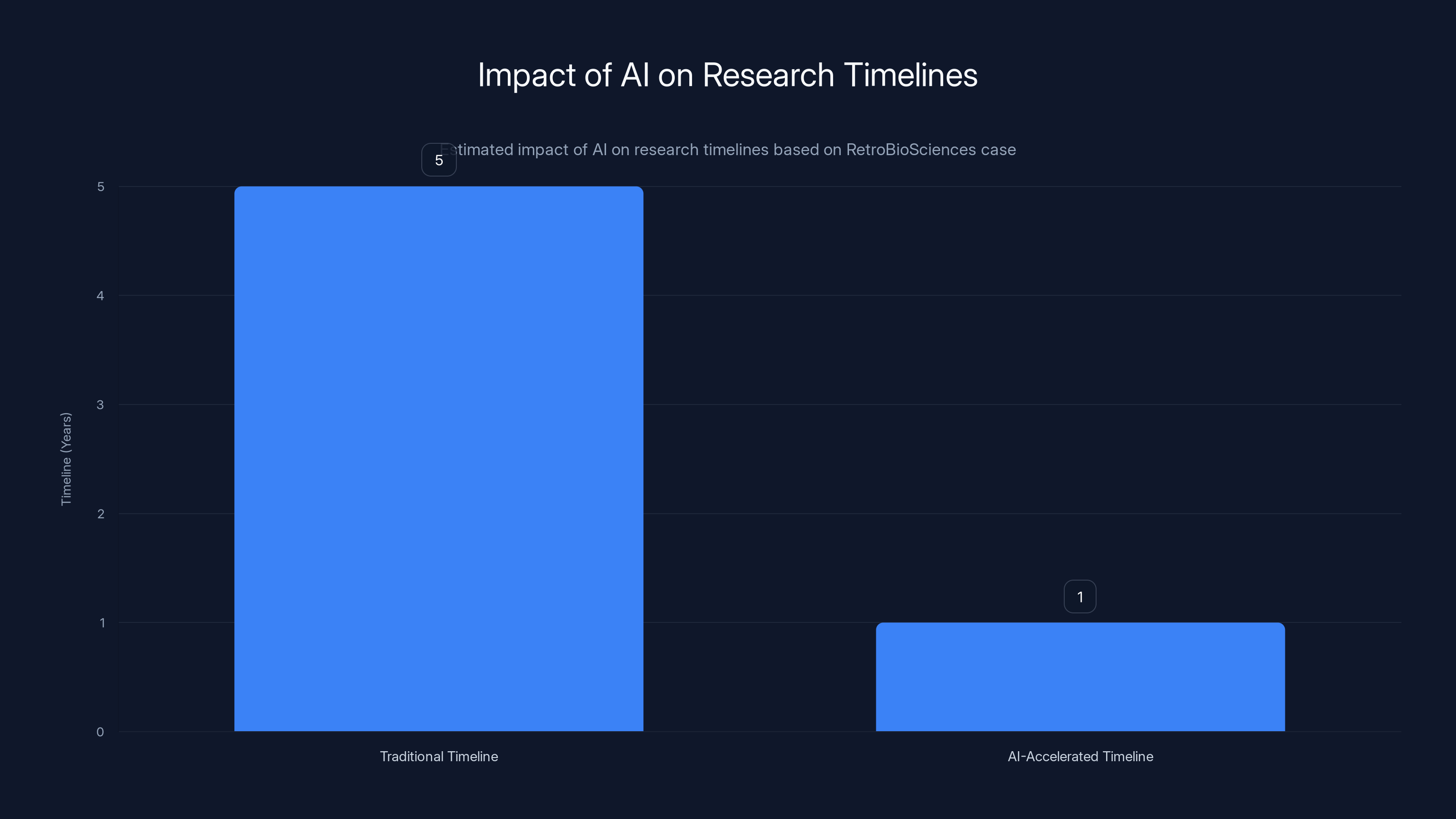

Biotech company examples illustrate this well. Retro Bio Sciences uses AI to design new proteins for specific functions. They claim this reduces timelines from years to months. The bottleneck in traditional protein design is iteration cycles. You suggest a design. It gets synthesized, tested, and results come back weeks later. You learn something, propose new designs, iterate again. AI collapses some of those cycles by suggesting better designs earlier.

The trust mechanism is crucial here. You don't trust the AI's prediction. You trust the AI plus specialized verification tools. The AI suggests three promising designs. The specialized tools run simulations to predict whether they'll fold correctly. You then synthesize the most promising one and test it experimentally. That still takes time, but you've eliminated the bad options before spending money on synthesis.

One detail that matters for reproducibility. When a researcher says "we used AI to design this," they mean AI played a role, not that AI did the work. The researcher still understood the system, still made decisions about which suggestions to pursue, still verified results experimentally. The AI was a collaborator that could process more possibilities faster.

AI adoption in research tools has grown by 50% year-over-year, with significant impacts on routine work acceleration and mathematics achievements. Estimated data.

Graduate-Level Benchmarks: Measuring Real Capability

OpenAI claims GPT-5.2 exceeds 92% accuracy on GPQA, which stands for Graduate-level Google-proof Q&A. This is a benchmark specifically designed to test whether AI systems can handle questions that require graduate-level scientific knowledge.

Ninety-two percent accuracy sounds impressive until you understand what accuracy means here. GPQA asks questions about real scientific concepts that graduate students study. It's not trivia. It's the kind of conceptual understanding you need to do actual research. Getting 92% right means the model understands the concepts deeply enough to apply them to novel questions.

For context, that's better than many humans without that specific background would do. It's roughly at the level of someone who just finished a graduate course and truly understood it. Not an expert with 20 years of experience, but someone competent enough to read papers in the field and understand what's happening.

This matters for research because it means AI can read scientific literature and actually understand it, not just statistically predict the next words. That's a fundamental shift. When you ask AI for a summary of a paper, it's not just extracting keywords. It's understanding the argument, the evidence, the limitations.

But here's the limitation that's crucial. GPQA is multiple choice. It tests whether AI can select the right answer from four options. Real research requires generating novel hypotheses, identifying gaps in knowledge, suggesting experiments that haven't been done. Multiple choice proficiency doesn't automatically translate there.

Graduate students often describe their research process as 70% reading papers and understanding the field, 20% designing and running experiments, 10% writing up results. If AI is strong at the reading and understanding phase, it genuinely saves time on that 70%. The 20% and 10%, the actually novel parts, are harder for AI to help with.

The Practical Impact: Where Time Gets Saved

OpenAI lists the practical applications. Coding. Literature review. Data analysis. Simulation support. Experiment planning. These aren't glamorous, but they're where researchers actually spend time.

Coding is obvious. Most researchers aren't professional programmers. They write code to analyze data, run simulations, control equipment. That code is often functional but inefficient. Asking AI to review code, suggest optimizations, implement standard algorithms—this saves hours per week. A researcher spends 20% of their time on code. If AI makes that 50% faster, that's 10% of their week back. For a 50-hour research week, that's 5 hours.

Literature review is brutal. A field generates thousands of papers annually. A researcher needs to know the landscape, understand what's been tried, know what failed and why. That means reading abstracts, sometimes full papers, keeping mental notes of who's doing what. AI can accelerate this. It can scan a hundred abstracts, summarize their approaches and findings, flag which ones are most relevant to your specific question. This takes a researcher from two weeks of reading to two days of reading plus AI summaries.

Data analysis is where AI's computational power genuinely matters. Researchers often have datasets too large to visualize easily. Pattern recognition across that data is what takes time. AI can run statistical tests faster, suggest which variables correlate with outcomes, flag outliers worth investigating. It won't replace a statistician, but it'll save a researcher from weeks of Excel work.

Experiment planning is the interesting one. Before running an experiment, you think through it. What variables matter? What controls do you need? What could go wrong? What's the sample size required for statistical power? These are questions AI can help think through. It won't replace your scientific intuition, but it will sanity-check your reasoning, suggest variables you might have forgotten, flag risks.

With AI integration, researchers spend approximately 40% of their time on AI-assisted tasks, freeing up more time for thinking and analysis. Estimated data.

The Validation Question: How Do We Know This Actually Works?

Here's where skepticism is warranted. OpenAI's claims are supported by benchmark results. But benchmarks aren't real-world impact. A benchmark is a controlled test. Real research is messy, iterative, and often fails. Does AI acceleration on a benchmark translate to actual research acceleration?

Some evidence suggests yes. The Retro Bio Sciences case is one of the few with specific numbers. They claim protein design timelines went from years to months. That's a massive improvement. But one company doesn't constitute proof across all of science. We'd need broader data on whether research groups using AI are actually publishing faster, discovering more, or producing higher-quality work.

There's also a selection bias problem. The researchers using AI intensively are probably those who are naturally tech-forward, possibly already efficient with their time. They might be accelerating regardless of AI, just by being early adopters of tools generally. Are they faster because of AI, or because they were already optimizing everything?

Long-term impact is another question. Maybe AI accelerates initial discovery, but does it make those discoveries more likely to be reproducible? More likely to lead to real innovation? Or does it just let researchers publish more papers that are mostly incremental?

OpenAI acknowledges these uncertainties in their report. They note that independent validation remains limited, that questions persist about how broadly results apply, whether reported gains translate to lasting scientific advances. That's honest language. It means they're not overselling.

But here's what we do know. Researchers are using it. Usage is growing fast. They're not doing this for fun. They're doing it because they believe it saves time. Whether that belief holds up at scale, whether it actually leads to breakthrough discoveries, that's a 5-10 year question we can't answer yet.

AI's Limitations in Scientific Research

AI confidently generates incorrect suggestions. This is perhaps the most important limitation. An AI model might suggest a physics approach that sounds right but violates conservation laws. It might propose a protein fold that's thermodynamically impossible. It might recommend combining chemicals that would explode. It does these things with full confidence.

This is why human oversight is critical. AI is a tool, and like any tool, it needs human judgment applied to its output. The difference between using AI productively and being harmed by AI is verification. Always verify. Always have someone who understands the science look at what AI suggests before acting on it.

Another limitation is novelty. AI models are trained on historical data. They're excellent at finding patterns within that data, recombining ideas in interesting ways, suggesting what might work based on what has worked before. But they're fundamentally not designed to imagine things that have no precedent. Genuinely new physics, new chemistry, new biological understanding—that requires thinking outside the training distribution.

AI can help with the 95% of science that's exploring within known territory. The 5% that's actually pushing boundaries? That's still almost entirely human territory. AI might suggest the path, but recognizing that the path leads somewhere genuinely new, that's a human insight.

Context persistence is also limited. Humans have persistent memory of their research. You remember experiments you ran six months ago, related conversations, papers you read that seem connected. AI systems get new context with each conversation. They don't remember last week's discoveries unless you explicitly tell them about them. Researchers have to manually maintain that continuity.

AI acceleration reduced protein design timelines from years to months at RetroBioSciences. Estimated data based on reported improvements.

Across Industries: Different Applications, Different Impact

Academic research and industry research use AI differently. Universities are often exploring, trying to publish novel findings. Industrial research is often optimizing for specific outcomes. These require different AI applications.

In academic mathematics, AI helps with verification and formalization. A mathematician might have an intuitive sense that something should be true. AI can help build the formal proof. In industry, mathematics is usually already proven. The question is whether you can compute it fast enough. AI might optimize algorithms or suggest computational approaches.

In academic physics, AI helps understand complex systems and design experiments. In industry, physics is usually applied physics. Design a material with specific properties. Optimize a process. Here, AI accelerates iteration between simulation and design.

Biology has the starkest difference. Academic biology is often exploring mechanisms, understanding how things work. Industrial biology is often engineering, designing organisms or molecules to do specific things. Academic researchers use AI to read literature and plan experiments. Biotech companies use AI for design and optimization.

Chemistry in pharma is probably where AI has the biggest impact already. Drug discovery is massive search problem. Billions of possible molecules, but only a tiny fraction might work as intended. AI narrows that search space dramatically. Researchers estimate AI reduces early-stage drug discovery timelines by 30-50% in some cases.

Materials science is another heavy AI user. Finding materials with specific properties is again a search problem. Experiment a few materials, get results, AI suggests the next logical tests based on property relationships. Iterate faster.

Scientific Progress and Timescales: The Reality

OpenAI positions AI as accelerating scientific progress. Faster discovery, faster understanding, faster solutions to pressing problems. That's true, but with important context.

Most foundational scientific understanding comes from a small global population of researchers. These are the people at universities, research institutes, and research-focused companies working on fundamental questions. Maybe 100,000 globally. Maybe 200,000. Everyone else is applying or extending their work.

AI could accelerate both the core research and the applied research. The impact on the applied side might be immediate—companies using AI to optimize processes, improve products. The impact on the core research side takes longer because discovery itself is slow. You can't rush biological validation. You can't speed up climate observations. You can't make the universe reveal its secrets faster than it does.

Drug development as an example. Finding a promising molecule is maybe 3-5 years with AI assistance, versus 5-7 years without. But then you spend 10+ more years on clinical trials. You can't accelerate that part. So AI saves you 2 years on a 15-year timeline. Important, but not revolutionary.

Climate modeling is another example. AI might help analyze climate data faster, suggest relationships worth investigating. But understanding climate requires decades of observations. Models require validation against future predictions. You can't get that validation faster.

Energy systems, medicine, public safety—these are where scientific progress matters most, according to OpenAI. Progress in these areas does save lives, prevent suffering, improve systems. But the basic timeline of scientific discovery hasn't changed much since the scientific revolution. Hypothesis, experiment, validation, publication, replication. That's the sequence, and it takes time for good reasons.

AI might compress the first few steps. But the last two, the ones that actually determine whether something is real—those still take time.

Estimated data shows AI accounts for 43% of annual researcher-hours, highlighting its significant role in modern research practices.

The Integration Path: How Researchers Get Started

If you're a researcher thinking about using AI in your work, there are patterns that work well. Start with literature review. That's where AI is safest and most useful. Let it read papers, summarize findings, identify clusters of related work. You verify the summaries against the actual papers, but you've cut your reading time significantly.

Then move to experiment planning. Use AI to think through your experimental design, identify potential issues, suggest controls you might have missed. This is mostly about sanity-checking your thinking, which AI is good at. Again, you make the final decision, but AI helps you think more systematically.

Coding is next. If you write code for analysis, simulation, or data processing, use AI to review it, suggest optimizations, generate standard algorithms. This is well-trodden ground. AI is reliable here because the code either works or it doesn't, and you can verify that quickly.

Data analysis is similar. Use AI to suggest analyses, identify patterns, recommend statistical tests. You interpret the results, but AI helps you think about the data more thoroughly.

Avoid using AI for judgment calls, scientific decisions, or anything where you don't have strong ability to verify output. Don't let AI tell you which hypothesis is true or which direction to take your research. That's still your decision. Use AI to accelerate the thinking, not to do the thinking.

The key principle is trust but verify. Verify more in areas where errors would be costly. Trust more in areas where you can quickly check if AI is right.

The Tools Landscape: What's Actually Available

ChatGPT is the obvious starting point. It's general-purpose enough for literature review, experiment planning, coding help, data analysis frameworks. But it's not specialized for any of these.

For biology, tools like Hugging Face have specialized models for protein structure prediction, trained on known structures. These are tools you'd use alongside ChatGPT, not instead of it.

For physics simulations, there are specialized frameworks, but most are built on open-source tools. You'd use GPT-like models for ideation and planning, then implement using whatever simulation software your field uses.

For mathematics, tools like Lean help formalize proofs. GPT models are good at suggesting approaches, but Lean is where you'd actually verify correctness.

Chemistry has tools like RDKit for molecular analysis, paired with generative models for design suggestions.

In most cases, you're not replacing existing tools. You're adding AI as a layer that helps you think about how to use those tools more effectively.

The Economic Impact: Who Saves What

Time saving translates to money saving. A researcher's time is expensive. A Ph.D.-level researcher in the US costs roughly

If AI saves 5 hours per week on routine tasks, that's

Those numbers assume the saved time translates to actual productivity. It might not if the researcher just works 5 fewer hours. But if it translates to more research output, more publications, more discoveries, the multiplier effect is significant.

For biotech companies, the impact is more direct. Faster drug discovery means faster time to market, which means significantly more revenue. A drug that reaches market one year earlier might earn an extra $100 million or more if it's treating a common condition.

Materials science companies might accelerate product development by 20-30% if AI makes the iteration cycle faster. That's directly profitable.

Academic research operates on different incentives. Faster discovery is better, but the incentive isn't financial, it's career advancement and understanding. Still, if a researcher can do 20% more work in the same time, that's more publications, more impact, faster career progress.

Future Trajectory: Where This Is Heading

The trend is toward more specialized AI tools, not just general-purpose models. You'll have models trained specifically on biology literature and experimental data. Models trained on physics simulations and theoretical work. Chemistry-specific models. These specialized tools will be better at their domains than general-purpose AI because they've learned the specific patterns and language of those fields.

Multimodal integration will increase. Future systems will connect simulation outputs, experimental data, literature, and computational results into unified platforms. A researcher might ask a system to design an experiment, suggest likely outcomes based on simulation, identify relevant published work, and plan the data analysis—all in one interface.

Verification will become more formalized. You'll see more integration with tools like Lean for mathematics, standardized simulation software for physics, formal verification methods for chemistry. The goal is reducing the gap between AI suggestion and confidence in AI suggestion.

Realtime collaboration will improve. Currently, using AI feels like a separate step—you query it, get results, integrate them back into your work. Future systems will be more integrated with the tools you already use. Your notebook updates, AI automatically analyzes the new data. Your simulation finishes, AI suggests what to check next.

The big unknown is whether AI will actually produce a breakthrough in understanding, or whether it'll just accelerate incremental progress. Most scientific advance is incremental. Small discoveries building on previous small discoveries. Genuine breakthroughs are rare. AI might make incremental progress 50% faster, but will it enable breakthroughs? That's still open.

There's also the possibility that AI introduces systematic biases. If everyone uses similar AI training data, everyone might explore similar hypothesis space. Genuine breakthroughs often come from people thinking differently, working outside the mainstream. If AI homogenizes how researchers think, it might reduce breakthrough potential even while accelerating routine work.

The Human Dimension: What Researchers Actually Think

Off the record, researcher conversations about AI are mixed. Early adopters love it. It's like having a highly capable research assistant who never sleeps, doesn't ask for raises, and is always available. The time savings are real. The frustrations are also real—AI confidently generates nonsense, requires verification, sometimes takes longer to verify than to do the work manually.

Skeptics worry about loss of skills. If everyone uses AI to code, will the next generation know how to actually code? If everyone uses AI for literature review, will people still develop deep knowledge of their field? There's legitimate concern here. Outsourcing thinking has risks.

Older researchers are slower to adopt. Partly conservatism, partly because they already have efficient workflows that don't include AI. Younger researchers adopted faster because they're learning workflows that include AI from the start.

The common theme is context dependency. AI is useful in some situations, not others. The skilled researchers treat it like any tool—appropriate for some jobs, not others. The unskilled researcher who relies on AI for judgment is at risk of making errors they don't recognize.

FAQ

What does it mean that AI is being used for scientific research?

Researchers are using large language models like ChatGPT in their actual work processes. They're not just experimenting with AI for fun—it's integrated into how they solve problems, analyze data, write code, and understand literature. This includes using AI to suggest experimental approaches, verify mathematical reasoning, accelerate routine computational tasks, and synthesize findings across multiple papers.

How much time does AI actually save researchers?

Estimates vary by task, but researchers report 30-50% time savings on routine work like coding, literature review, and data analysis. For specialized tasks like formal proof development or protein design iteration, savings can be higher. However, the time saved depends on how much time researchers spend on verification—checking that AI output is actually correct reduces the net time savings compared to doing the work manually without verification.

Can AI generate completely new scientific discoveries on its own?

No. Current AI systems cannot generate genuinely novel scientific theories or discoveries independently. What they can do is accelerate the process of exploring existing knowledge, suggest connections between ideas humans might miss, help verify existing proofs, and optimize designs based on known principles. The actual discovery—recognizing that something genuinely new has been uncovered—remains a human capability. AI accelerates the path to discovery, but doesn't make the discovery itself.

What are the biggest risks of using AI in research?

The primary risk is confident incorrect output, called hallucination. AI models generate plausible-sounding text that may be completely false. In research, this is dangerous because incorrect suggestions might lead to wasted experiments, false conclusions, or flawed methodology. Another risk is over-reliance—researchers might trust AI output without adequate verification. Homogenization of research approaches is a longer-term concern, where widespread AI use might reduce diversity of thinking in a field.

How do researchers verify that AI suggestions are actually correct?

Verification methods depend on the domain. In mathematics, AI suggestions are verified by formal proof systems like Lean. In physics and chemistry, suggestions are tested through simulation or actual experimentation. For literature synthesis, researchers manually review the papers AI summarized. In coding, suggestions are tested against actual code execution. The core principle is always the same: AI output is trusted only to the extent it can be independently verified by the researcher.

Is AI accelerating scientific progress significantly?

AI is accelerating the pace of routine scientific work—the 40-50% of research time spent on non-novel tasks. Whether this translates to faster or better discoveries is still an open question. Some biotech companies report 30-50% faster iteration on drug discovery. Academic researchers report faster literature review and experiment planning. But whether the actual rate of novel scientific discovery has increased is harder to measure and will take years to fully evaluate.

What types of research benefit most from AI assistance?

Research involving large literature bases benefits from AI literature review. Work involving code benefits from AI programming assistance. Tasks with large parameter spaces benefit from AI optimization suggestions. Iterative design processes (protein design, materials science, circuit design) benefit from faster iteration cycles. Research less likely to benefit includes qualitative work, long-term observational studies, or research requiring entirely novel conceptual frameworks.

How should a researcher get started using AI if their field hasn't widely adopted it yet?

Start with low-risk applications where output is easy to verify, like literature summarization or code review. Use AI to think through experimental design and identify potential issues, but make final decisions yourself. Avoid using AI for scientific judgment—what hypothesis is true, which direction to pursue—because those decisions require expertise and context. Treat AI as a research assistant for routine work, not as a replacement for your scientific thinking. Always verify results before acting on them.

Will AI eventually do most scientific research automatically?

There's no evidence suggesting AI will autonomously conduct scientific research at the frontier. AI systems operate within the distribution of their training data, making them excellent at exploring known territory but poor at recognizing what's genuinely new. The frontier of science requires human judgment about what's worth investigating, recognition of unexpected results, and the creativity to ask new questions. AI will likely become increasingly integrated into research processes, but as a tool augmenting human researchers, not replacing them.

What benchmarks demonstrate AI's scientific capability?

Key benchmarks include GPQA (Graduate-level Google-proof Q&A), which tests graduate-level scientific knowledge with 92%+ accuracy achieved by GPT-5.2. The International Mathematical Olympiad benchmark shows competitive performance on difficult mathematics problems. Frontier Math tests performance on novel mathematical problems still being worked on by human researchers, where AI achieves partial success. These benchmarks are useful as capability indicators but don't directly translate to real-world research impact, which is harder to measure.

How does AI in research differ between academia and industry?

Academic research uses AI primarily for acceleration of routine work and to help plan novel investigations. The goal is publication and understanding. Industrial research, especially in biotech and materials science, uses AI for design optimization and iteration acceleration. The goal is faster product development and competitive advantage. Industry has financial incentives to measure impact and optimize workflows, so integration tends to be faster and more systematic. Academia moves slower because research culture is more conservative and success is measured differently.

TL; DR

- Massive Scale: 8.4 million messages weekly on science and math from 1.3 million researchers globally, representing 50% year-over-year growth in AI research tool adoption

- Mathematics Achievement: AI systems achieve gold-level performance on the International Mathematical Olympiad and contribute to solutions of open mathematical problems with human verification

- Routine Work Acceleration: AI saves 30-50% time on coding, literature review, data analysis, and experiment planning—the non-novel parts of research

- Verification Required: All AI output must be independently verified because models confidently generate incorrect suggestions; this is essential for research safety

- Hybrid Human-AI Workflow: Effective research uses AI as a collaborator for routine tasks while keeping human judgment on scientific decisions, novel hypothesis generation, and validation of conclusions

- Bottom Line: AI is accelerating the pace of routine scientific work across mathematics, physics, biology, and chemistry, but the impact on fundamental discovery rates remains to be seen over the next 5-10 years

Key Takeaways

- AI is becoming embedded in research workflows with 8.4 million weekly messages on science/math topics from 1.3 million global researchers, growing 50% annually

- AI achieves gold-level performance on International Mathematical Olympiad and contributes to open problem solutions, but requires human verification of all output

- Time savings of 30-50% occur on routine tasks (coding, literature review, data analysis) while acceleration of fundamental discoveries remains unproven

- Hybrid human-AI workflows combining specialized tools with general-purpose models prove most effective while keeping human judgment central to scientific decisions

- Verification is essential because AI confidently generates incorrect suggestions; the cost of verification determines whether AI actually saves net time per task

Related Articles

- Linus Torvalds' AI Coding Confession: Why Pragmatism Beats Hype [2025]

- AI Discovers 1,400 Cosmic Anomalies in Hubble Archive [2025]

- Why AI Agents Keep Failing: The Math Problem Nobody Wants to Discuss [2025]

- AI Coding Agents and Developer Burnout: 10 Lessons [2025]

- Elon Musk's $134B OpenAI Lawsuit: What's Really at Stake [2025]

- The Real AI Revolution: Practical Use Cases Beyond Hype [2025]

![How AI Is Accelerating Scientific Research Globally [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/how-ai-is-accelerating-scientific-research-globally-2025/image-1-1769641614100.jpg)