How AI Discovered 1,400 Hidden Cosmic Anomalies in Hubble's Archive

Two astronomers at the European Space Agency just pulled off something remarkable. David O'Ryan and Pablo Gómez trained an AI system to search through 35 years of Hubble Space Telescope data. What they found? Over 800 previously unknown "astrophysical anomalies" hiding in plain sight.

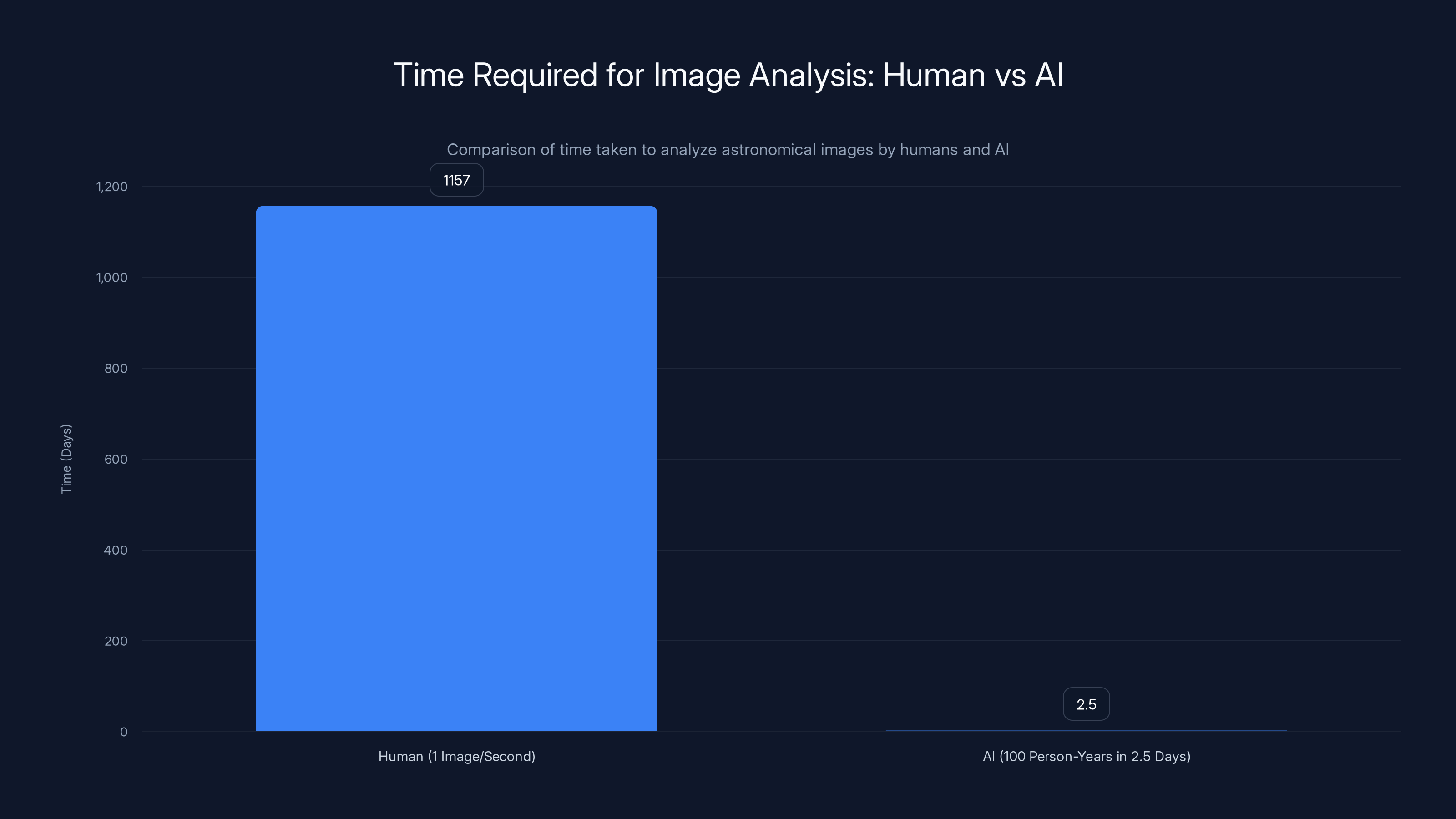

But here's the thing that really matters: they did it in 2.5 days.

Let that sink in. A dataset so massive that traditional human review would take teams of researchers months to manually examine. An AI model called Anomaly Match scanned nearly 100 million image cutouts from the Hubble Legacy Archive, flagging the weirdest objects it could find. The result was published in Astronomy & Astrophysics, and it reveals something profound about how we'll conduct science in the age of AI.

This isn't just about finding pretty pictures of galaxies. It's about fundamentally changing how astronomers approach discovery. When you're drowning in data, when there's literally too much information for humans to reasonably process, AI becomes the difference between finding hidden treasures and missing them entirely.

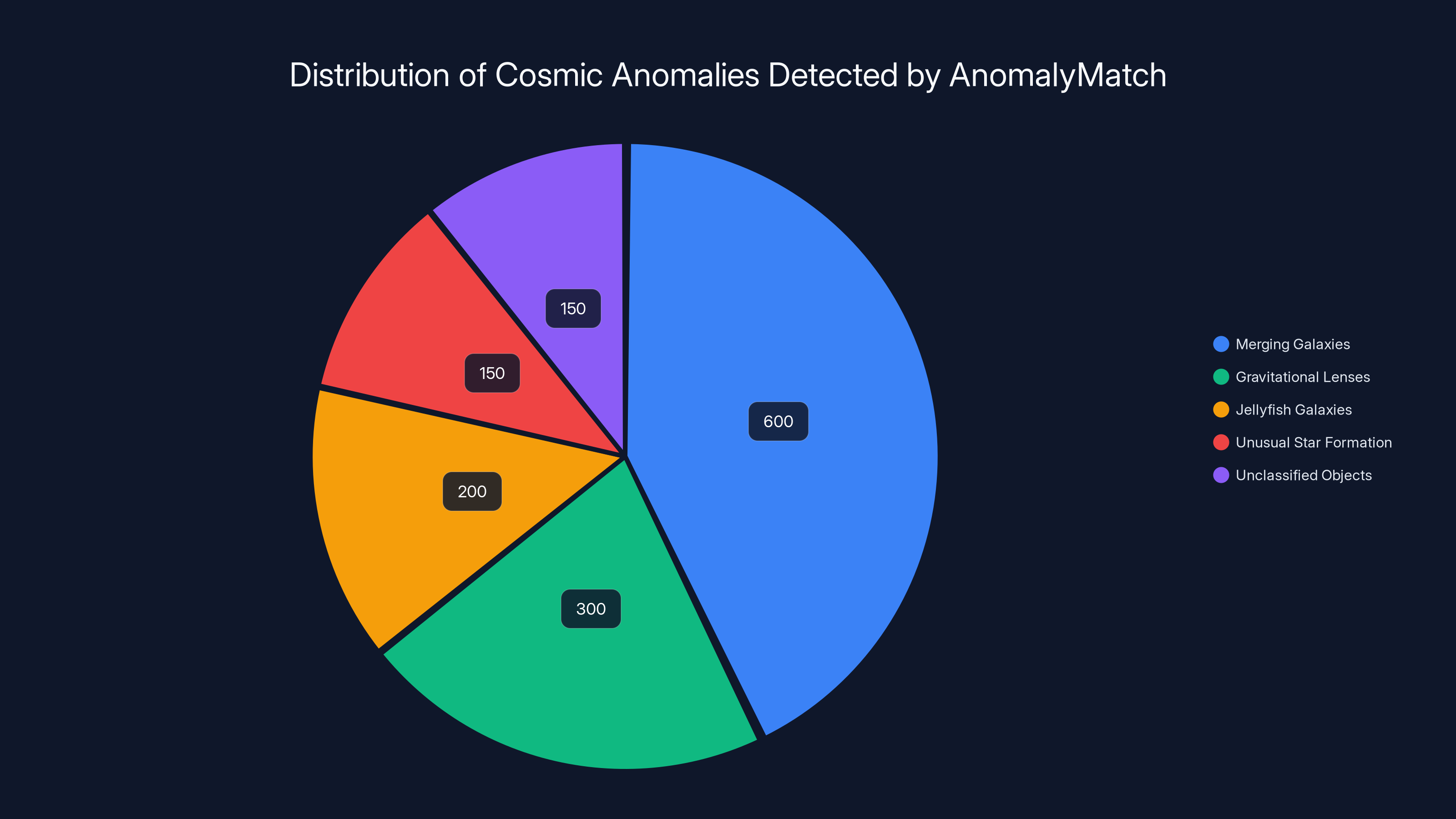

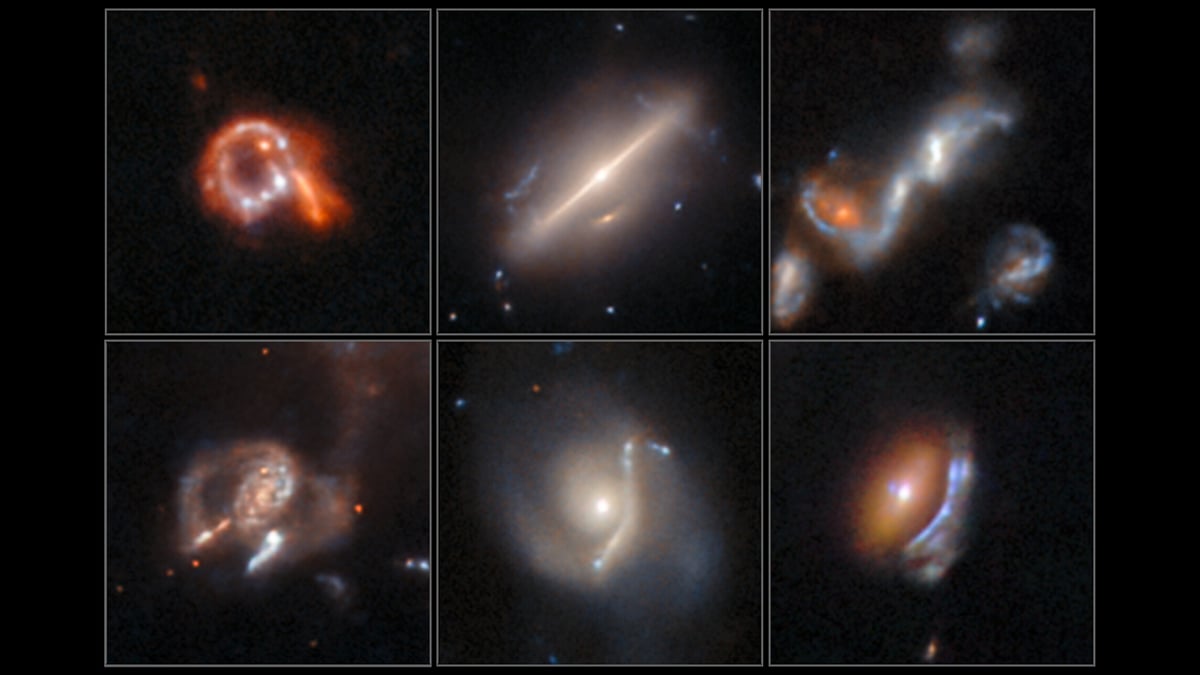

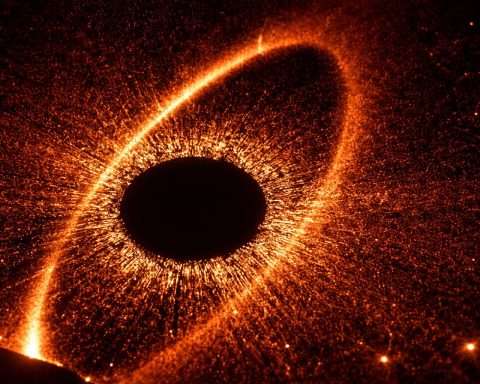

The anomalies Anomaly Match discovered include nearly 1,400 objects total. Merging galaxies. Gravitational lenses that bend light into perfect circles and arcs. Jellyfish galaxies with dangling tentacles of gas. And most intriguingly, several dozen objects that defied classification altogether.

"Perhaps most intriguing of all, there were several dozen objects that defied classification altogether," the European Space Agency noted in their announcement. "Finding so many anomalous objects in Hubble data, where you might expect many to have already been found, is a great result."

This discovery matters because it shows us something we're going to see repeatedly over the next decade: AI is becoming the research assistant that scientists never had. It doesn't replace human judgment. It amplifies it. It finds the needles. Humans decide which ones matter.

The implications here are staggering. The Hubble archives represent just one dataset among hundreds that astronomers maintain. If this approach works for Hubble, it works for every other major observatory. The James Webb Space Telescope, the Chandra X-ray Observatory, the upcoming Roman Space Telescope—all of them are generating massive datasets that could contain hidden discoveries. And now there's a template for finding them.

The Scale Problem: Why Humans Can't Keep Up Anymore

Let's talk about the fundamental problem that makes AI necessary in modern astronomy. It's not that humans are lazy. It's that the volume of data has become genuinely unmanageable.

When Hubble launched in 1990, its cameras took images and stored them on tape. Scientists would request data, wait for it to be processed, and then analyze it. The process was slow, deliberate, and manageable because the amount of data was limited by storage costs and processing power.

That world doesn't exist anymore.

Today, a single modern astronomical survey can generate petabytes of data. A petabyte is one million gigabytes. To put that in perspective, if you downloaded one gigabyte per second, 24 hours a day, it would take you 31,688 years to download a petabyte. And that's just one survey's worth of data.

The Hubble Legacy Archive alone contains data from 1.5 million observations. Each observation generates multiple images. Each image gets broken down into cutouts, thumbnails, and processed versions. That's how you get to 100 million image cutouts.

Now imagine a human astronomer sitting down to look at these images. Even if they could spend one second per image, looking at it and deciding if it's interesting, it would take them 1,157 days of non-stop work. That's three years of 24-hour shifts with no sleep, no breaks, no bathroom breaks.

This creates what astronomers call the "data crisis." You have more data than you could ever meaningfully analyze. Telescopes are so powerful and so sensitive that they pick up everything, including the things you didn't expect to find. Those unexpected things? They're often the most interesting scientifically.

Before AI, astronomers dealt with this by developing specific search strategies. You'd know what you were looking for, and you'd write code to find it. You'd look for galaxies of a certain size, light output, or redshift. You'd search for specific types of objects that matched known patterns.

But what about the things you don't know to look for? What about the objects that don't fit existing categories? Those would just sit in the archives, undiscovered, forever.

That's exactly where Anomaly Match changed the game.

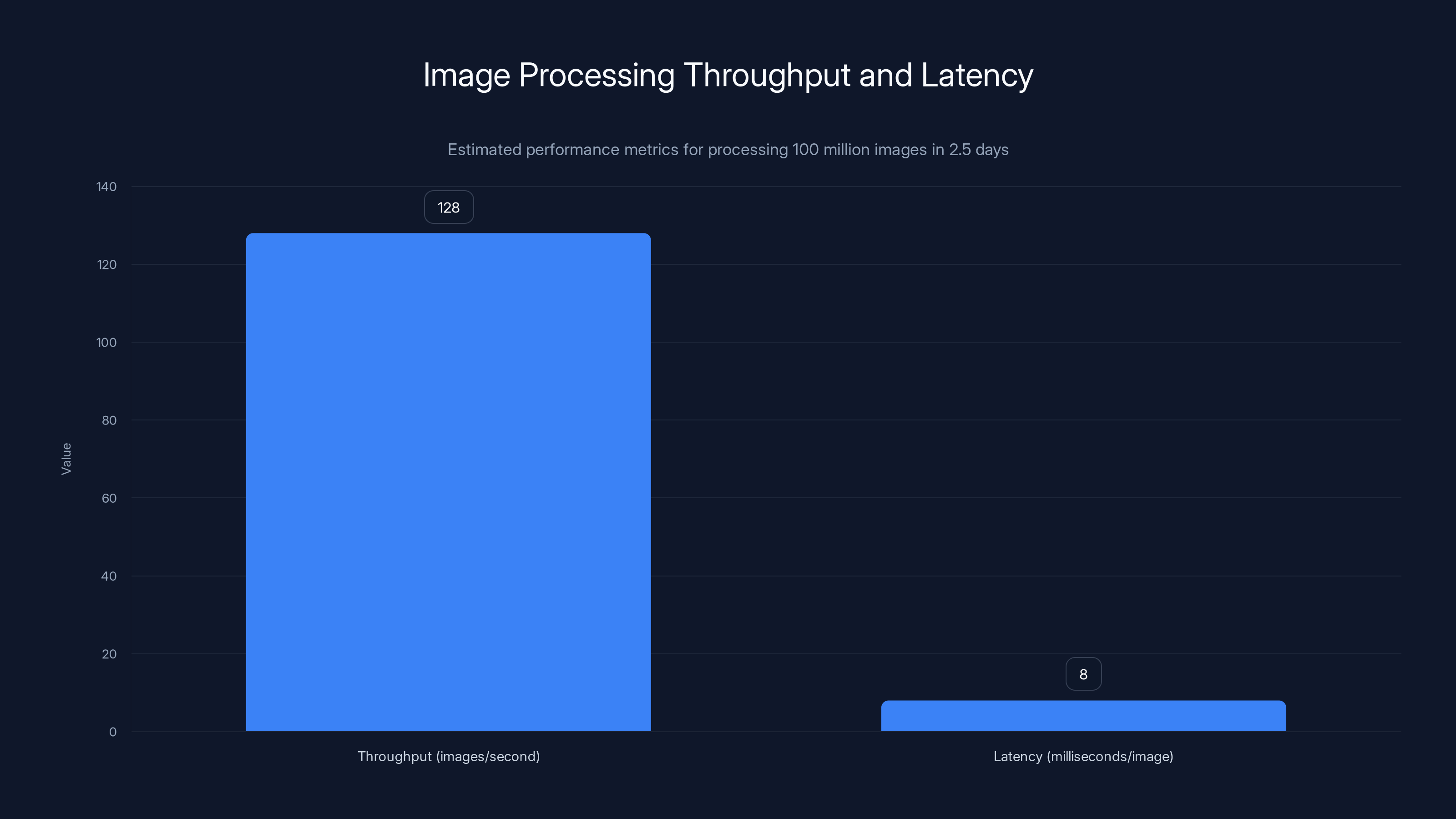

The system achieved an estimated throughput of 128 images per second with a latency of approximately 8 milliseconds per image, showcasing the efficiency of the optimized processing pipeline. Estimated data.

What Is Anomaly Match? Understanding the AI System

Anomaly Match isn't a general-purpose chatbot or a large language model. It's a specialized machine learning system designed to do one thing extremely well: identify images that are different from the norm.

The system works through what's called "anomaly detection," which is a specific category of AI designed to find outliers. Instead of asking "What is this object?", anomaly detection asks "Does this look different from everything else?"

To train Anomaly Match, the ESA researchers fed it millions of "normal" Hubble images. Regular galaxies. Stars. Noise. Dust. All the typical stuff you see in telescope data. The model learned to recognize what "normal" looks like in Hubble imagery.

Then they pointed it at the full archive. When it encountered an image that didn't match the pattern of normal, it flagged it. Not because it knew what the object was, but because it knew the image was somehow different.

This approach has a huge advantage: it doesn't need pre-programmed categories. You don't need to tell the system "Look for jellyfish galaxies" or "Look for gravitational lenses." The system just finds weird stuff, and then humans investigate why it's weird.

The 2.5-day processing time matters because it demonstrates computational efficiency. The researchers didn't need a supercomputer running for months. Modern machine learning models, when properly optimized, can process enormous datasets in reasonable timeframes.

The interesting part is what happened after the AI did its work. Anomaly Match flagged nearly 1,400 objects. But the AI doesn't get the final word. Human astronomers reviewed each flagged image to confirm that yes, it's actually anomalous, and yes, it's worth studying further. Of those 1,400 flagged objects, most turned out to be exactly what the AI suggested: genuinely interesting cosmic phenomena.

This human-in-the-loop approach is crucial. The AI handled the brute-force searching. Humans provided the judgment. Together, they found things neither could have found alone.

Merging galaxies were the most common anomaly detected, while unclassified objects, which may represent new phenomena, accounted for a significant portion. Estimated data.

The Discovery Categories: What Anomaly Match Actually Found

Let's break down what astronomers found hidden in those archives. Understanding the different types of anomalies reveals why this discovery is scientifically significant.

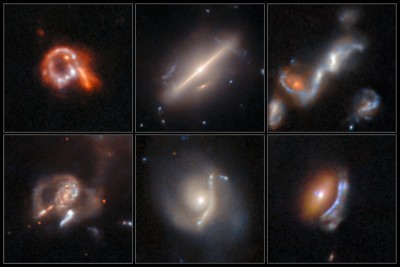

Merging and Interacting Galaxies

The majority of the discoveries were galaxies in collision or close interaction. This sounds dramatic, but it's actually common on cosmic timescales. Galaxies are constantly moving, and when they get close to each other, gravity does wild things.

When two galaxies merge, it's not a quick event. The process takes hundreds of millions of years. But at any given moment, there are thousands of galaxies mid-merge somewhere in the observable universe. In our own cosmic neighborhood, the Andromeda Galaxy is heading toward a collision with the Milky Way over the next few billion years.

Studying merging galaxies helps astronomers understand how galaxies evolve. When galaxies merge, they trigger massive star formation. Black holes collide and potentially merge. The structure of the resulting galaxy depends on the masses, velocities, and angles of collision. Each merging galaxy system teaches us something new about galactic physics.

Anomaly Match found hundreds of these systems. Many had probably been catalogued before, but the AI helped identify merging systems that might have been overlooked because they didn't fit typical search criteria.

Gravitational Lenses

One of the most visually stunning discoveries in modern astronomy is the gravitational lens. Einstein predicted this phenomenon in 1915: massive objects bend spacetime, which bends light.

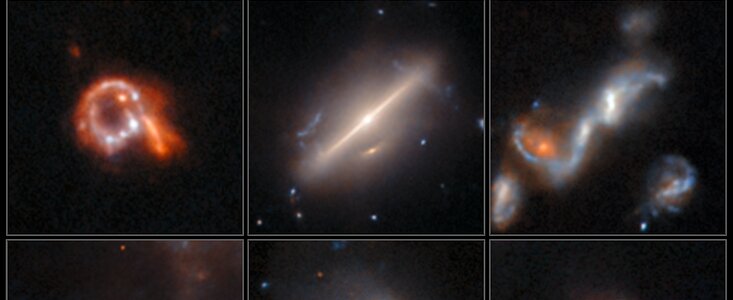

When light from a distant galaxy passes near a massive foreground object (usually another galaxy or a cluster of galaxies), the light gets bent. If the alignment is perfect, the distant galaxy appears as a ring around the foreground object. If the alignment is slightly off, you get multiple images of the same distant galaxy. Sometimes the geometry creates perfect Einstein Rings, circles of light that look too perfect to be real.

Gravitational lenses are scientifically valuable for multiple reasons. They allow astronomers to study very distant galaxies that would otherwise be too faint to observe. The lensing effect magnifies the light, sometimes making distant galaxies observable. Lenses also help measure the total mass of the foreground galaxy, including dark matter that's invisible but whose gravity affects the light.

The Hubble archives contained many gravitational lenses that hadn't been systematically catalogued. Anomaly Match found them because they're genuinely weird-looking. A perfect ring of light around a galaxy? That doesn't look like a normal galaxy. It looks anomalous. And it is.

Jellyfish Galaxies

One of the most visually striking discoveries is the jellyfish galaxy. These are spiral or disk galaxies that have developed long streams of gas extending outward, looking like tentacles.

Jellyfish galaxies form through a specific process. When a galaxy moves rapidly through a dense region of space (like the interior of a galaxy cluster), the intergalactic gas exerts pressure on it. This pressure, called ram pressure, strips gas away from the galaxy. The gas gets pulled backward, creating the tentacles.

It's like driving a truck through a rainstorm. The rain doesn't penetrate into the truck; it flows around and past it. Similarly, the intergalactic medium flows past the galaxy, stripping away its gas in the process.

What makes jellyfish galaxies fascinating is that they represent galaxies in transition. The gas being stripped is the same gas that fuels star formation. As it gets removed, the galaxy's star-forming regions shut down. Jellyfish galaxies are dying, in a sense, transformed by their environment.

Studying them helps astronomers understand how galaxies stop producing stars and eventually become quiescent red galaxies. Without environmental quenching, galaxies keep making stars indefinitely. With it, galaxies age into red-and-dead systems.

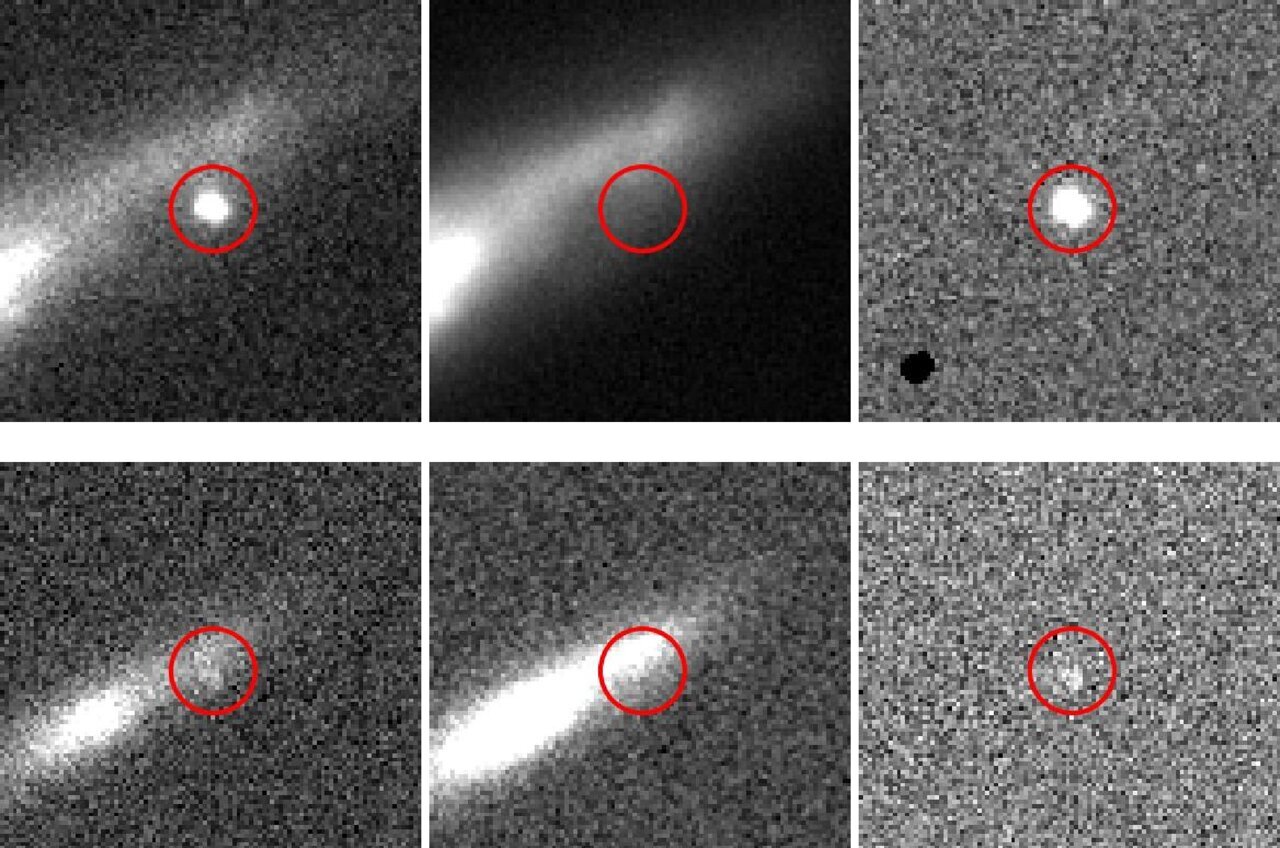

Unexplained Anomalies

The most intriguing category is the "unclassified" objects. Anomaly Match flagged several dozen images that looked weird but didn't fit into any standard category. They weren't merging galaxies. They weren't gravitational lenses. They weren't jellyfish galaxies.

They were just... weird.

The European Space Agency specifically highlighted this in their announcement: "Perhaps most intriguing of all, there were several dozen objects that defied classification altogether."

This is where real discovery happens. In science, the unexpected is often more valuable than the expected. When you find something that doesn't fit your categories, you have to rethink your categories. Maybe those objects are a completely new class of galaxy. Maybe they're a new phenomenon entirely.

With only 2.5 days of searching, researchers don't have time to fully investigate every mystery. But now they know the mysteries are there. They have 36 unclassified objects to study in detail. Some might turn out to be artifacts or misinterpretations. Others might be genuinely new discoveries.

This is the power of systematic AI-driven searching. It doesn't just find more of what you expect. It finds the things that break your expectations.

The Technical Achievement: How 2.5 Days Became Possible

To appreciate why 2.5 days is remarkable, you need to understand the technical constraints of this task.

Computational Efficiency

Processing 100 million images in 2.5 days requires moving through approximately 463,000 images per hour, or about 128 images per second. That's not just about raw processing speed. It's about optimization at multiple levels.

First, the images have to be loaded. Each image is a file on disk. Loading and unloading files takes time, especially when dealing with millions of them. The researchers had to optimize data pipeline architecture to keep images in memory buffers and process them in batches rather than individually.

Second, the machine learning model itself has to be fast. A typical deep learning model trained for image classification might take several seconds per image. For this task, researchers needed a model that could process each image in milliseconds. This likely meant using a more efficient architecture than a full-sized convolutional neural network.

Third, the computation had to be parallelized. A single processor working sequentially would take years. The researchers almost certainly used GPU clusters or cloud computing infrastructure to process thousands of images simultaneously.

The specific technical choices matter because they show that you don't always need cutting-edge AI models to solve real problems. You need well-engineered systems that match the problem constraints.

Model Architecture Choices

We don't have detailed technical information about Anomaly Match's internal architecture, but we can infer some things based on the requirements.

First, it needed to handle images of different sizes and formats. Hubble images come in various wavelengths (visible light, infrared, ultraviolet) and resolutions. A flexible model architecture that could work with any image input was essential.

Second, the model needed to be generalizable. It was trained on historical Hubble data and then applied to the same archive. But the researchers want to use this approach on other telescopes too. That means the model can't be overfit to Hubble-specific characteristics.

Third, the model needed to be interpretable, at least to some degree. When the model flagged an image as anomalous, astronomers wanted to understand why. Modern deep learning systems are often opaque, making it hard to know what features the model is actually looking at.

The researchers likely used a combination of techniques. An autoencoder architecture could learn to reconstruct normal images and flag reconstructions that fail. Isolation forests could identify outliers in feature space. Ensemble methods combining multiple approaches could improve robustness.

Hardware and Infrastructure

Running machine learning on 100 million images requires serious infrastructure. The researchers had access to ESA computational resources, likely including high-performance computing clusters.

A modern GPU can process roughly 1,000-10,000 images per second depending on image size and model complexity. To achieve the stated 2.5-day timeframe on 100 million images, you'd need roughly 10-100 GPUs running in parallel.

Cloud providers like Amazon Web Services, Google Cloud, and Microsoft Azure offer this kind of GPU capacity on demand. The ESA's own computing infrastructure was likely sufficient, but it shows that even with dedicated resources, running this analysis requires serious computational power.

The total computational cost probably ran into tens of thousands of dollars in cloud credits or equivalent institution resources. For astronomy research, that's actually quite reasonable when the alternative is hiring teams of researchers to manually review images over months or years.

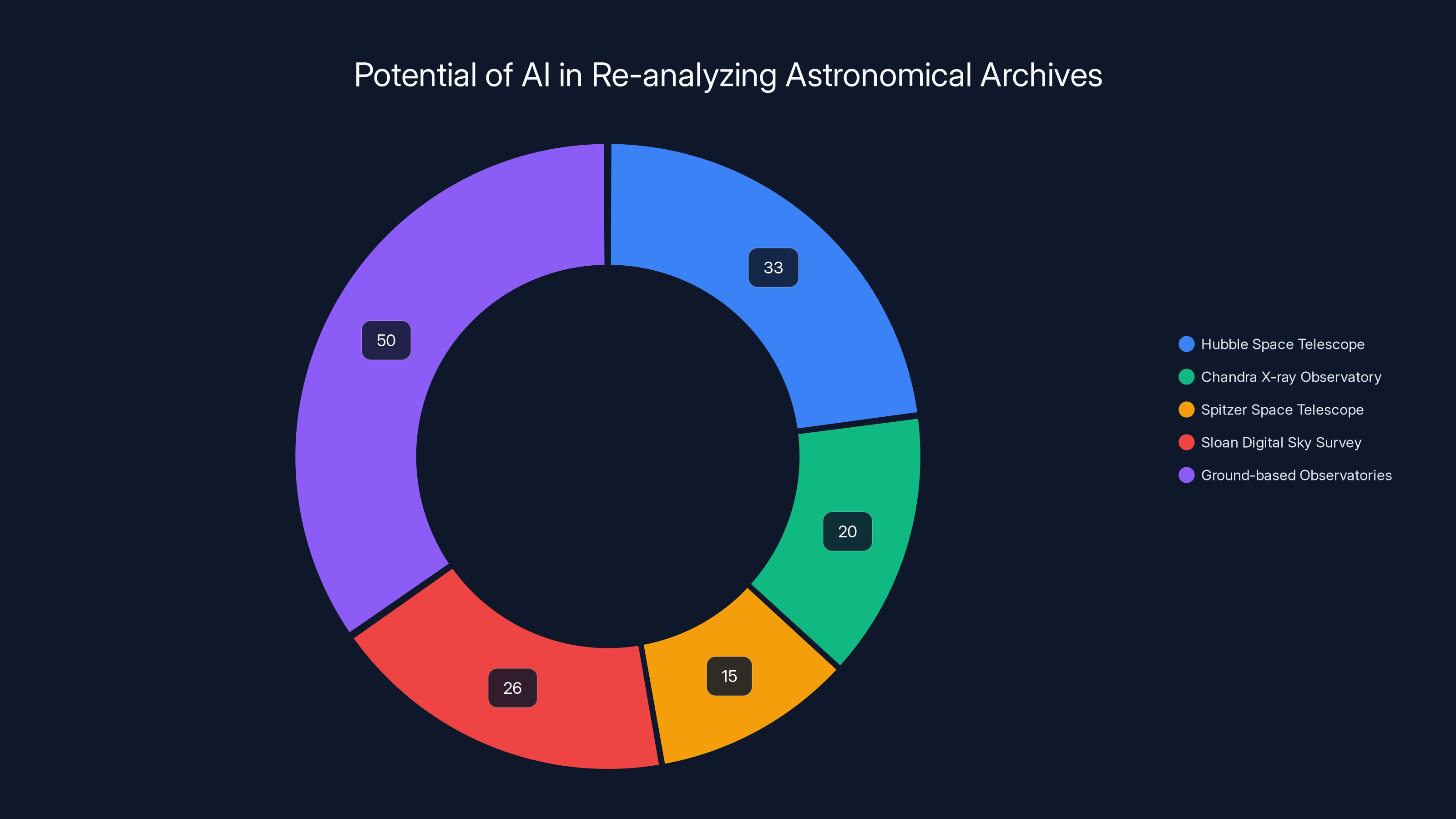

Estimated data shows the potential of AI in unlocking decades of archived astronomical data, with ground-based observatories holding the most extensive records.

Why This Matters: The Broader Implications for Astronomy

This discovery is significant for several reasons that extend far beyond the specific objects found.

Unlocking Archived Data

Astronomical archives are buried treasure. The Hubble Space Telescope has been observing the universe since 1990. Every observation gets stored permanently. The archive is freely available to researchers worldwide.

But here's the problem: just because data is available doesn't mean it's been fully explored. Historically, astronomers would propose specific observations, take the data, analyze it, publish findings, and then move on. The data stayed in the archive, but the original context was lost. Other researchers could access it, but discovering new things required knowing what to look for.

AI changes this calculus. Now, decades-old data can be re-analyzed with modern techniques. Objects that didn't match any search criteria in 1998 might match today's AI-based anomaly detection. Data that was considered fully explored can be mined again for new discoveries.

The implications are huge. There are hundreds of astronomical archives around the world. Every major observatory has one. If Anomaly Match can work on Hubble data, it can work on data from:

- The Chandra X-ray Observatory (20+ years of data)

- The Spitzer Space Telescope (15+ years of infrared data before it shut down)

- The Sloan Digital Sky Survey (26+ years of optical imaging)

- Ground-based observatories with decades or centuries of observations

Each archive probably contains undiscovered phenomena. Each one represents a potential goldmine of discoveries waiting for the right AI system to unlock them.

Democratizing Discovery

Historically, making major astronomical discoveries required access to observing time on world-class telescopes. You needed to propose observations, compete against other researchers for time, conduct the observations, and analyze the data.

This process is expensive and competitive. Hundreds of proposals fight for limited observing time. Not everyone gets access.

But Anomaly Match works on archived data that's free and open. Any researcher can download Hubble data. Now, with the right AI tools, they can discover new phenomena without needing to book telescope time.

This democratizes discovery in a profound way. It means that brilliant researchers without access to major computing resources or telescope time can still make discoveries. They just need the right AI tools and the initiative to use them.

Redefining the Role of Astronomers

This discovery points to a shift in what it means to be an astronomer. Traditionally, the skill was in identifying what to observe and interpreting what you found. The telescopes were the bottleneck.

Increasingly, the bottleneck is data analysis. Telescopes generate data faster than humans can meaningfully analyze it. The skill becomes recognizing what's interesting in massive datasets.

AI handles the pattern recognition. Humans provide judgment, context, and the scientific intuition about what matters. The two work together.

This is a fundamental shift in how science gets done. It requires astronomers to develop new skills: understanding machine learning, optimizing data pipelines, knowing how to validate AI outputs. The field is becoming less about pointing telescopes and more about being a sophisticated data scientist.

Lessons for Other Scientific Domains

While this discovery is specific to astronomy, the lessons apply broadly to any field generating massive amounts of data.

Medicine and Pathology

Pathologists examine microscope slides to diagnose diseases. A single patient biopsy might generate thousands of images at different magnifications and stains. A hospital system can accumulate millions of pathology images.

AI anomaly detection could identify unusual tissue patterns that pathologists might miss. It could flag rare diseases or atypical presentations. The same approach Anomaly Match used could work here.

Climate Science

Weather and climate models generate enormous amounts of data. Satellite imagery covers the entire planet multiple times per day. Climate scientists want to understand anomalies: unusual weather patterns, extreme events, atmospheric phenomena.

Anomaly detection AI could systematically search climate data for interesting patterns. It could identify emerging climate phenomena or potential tipping points automatically.

Genomics

Genome sequencing produces terabytes of data. A single human genome is 3 billion base pairs. A genome-wide association study might involve genetic data from millions of people.

Finding genetic variations associated with diseases requires searching massive datasets. AI anomaly detection could identify rare variants with phenotypic effects, discovering connections that statistical analysis alone might miss.

Industrial Quality Control

Manufacturing plants generate continuous streams of sensor data. Temperature, pressure, vibration, chemical composition, etc. Most data points are normal. But anomalies indicate problems: equipment failures, process deviations, contamination.

AI systems like Anomaly Match could monitor production in real-time, flagging anything unusual. This is already happening in some advanced factories, but the approach from astronomy is more sophisticated than typical industrial systems.

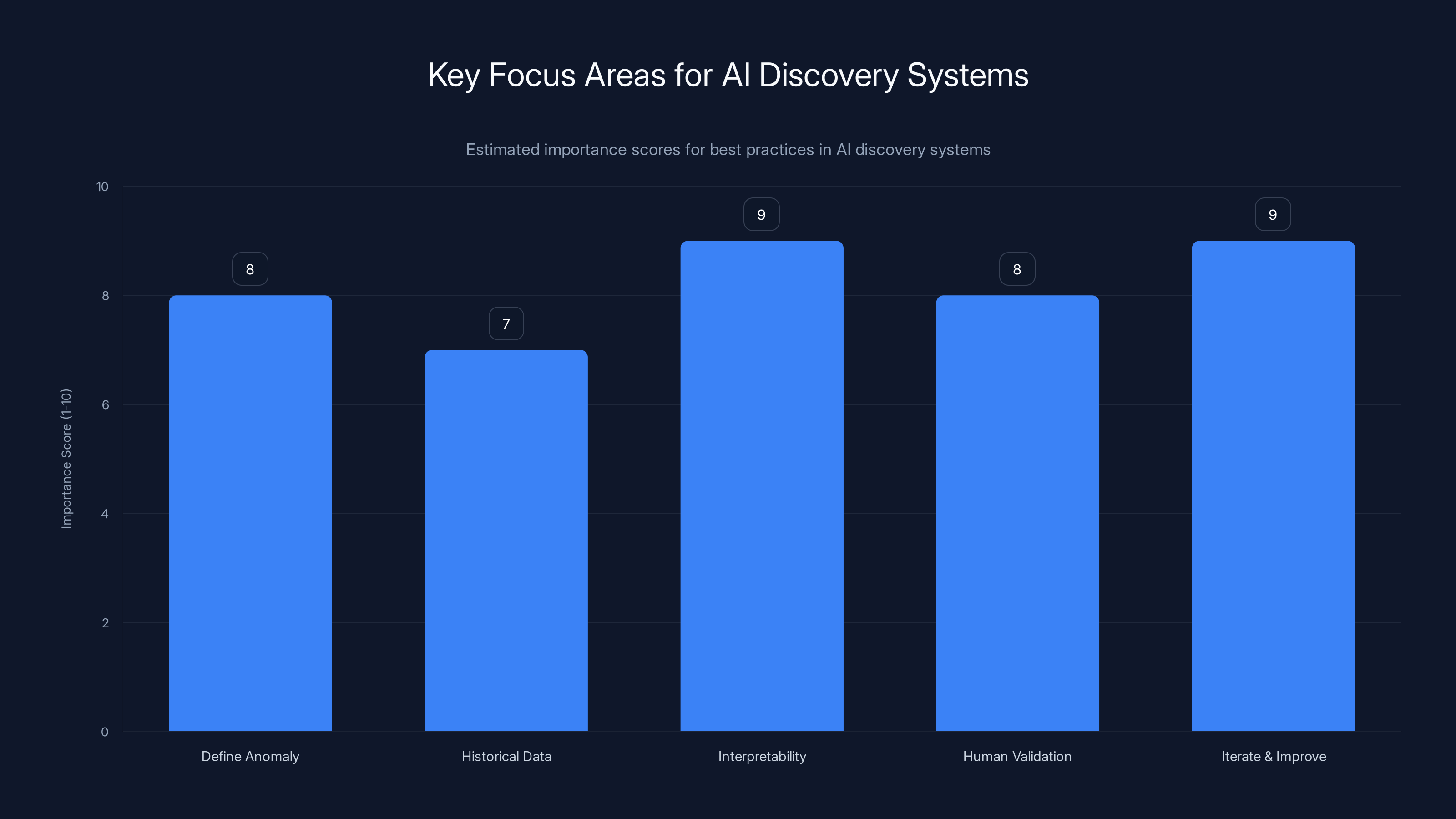

Interpretability and iterative improvement are crucial for effective AI discovery systems, scoring highest in importance. (Estimated data)

The Validation Challenge: How to Know the AI Is Right

One crucial question remains: how do astronomers know the AI isn't just hallucinating? How do they validate that the flagged anomalies are real?

The answer involves human review combined with careful validation methodology.

Manual Review by Expert Astronomers

Each image flagged by Anomaly Match was reviewed by human astronomers. They looked at the image and asked: "Is this actually anomalous? Is this something worth studying?"

This human validation step is essential. AI systems can make mistakes. They can misinterpret noise as signal. They can flag artifacts as real objects. Expert human judgment filters out false positives.

The fact that most flagged objects passed human review (about 1,400 out of however many were initially flagged) suggests the model had good precision. It wasn't flagging random images.

Comparison with Existing Catalogs

Many of the anomalies discovered had probably been observed before. Astronomers could cross-reference new discoveries with existing catalogs. If an object was already known and catalogued, it's still a valid discovery from the archive-searching perspective, even if it wasn't new to science.

The particularly interesting ones are objects that had never been catalogued before. These genuinely represent new discoveries.

Follow-up Observations

For the most intriguing objects, astronomers might request follow-up observations with other telescopes. If the object is real and interesting, follow-up data will confirm and extend the initial discovery. If it's a false positive, follow-up will reveal inconsistencies.

The unclassified objects are particularly likely to get follow-up attention. Those are the ones that genuinely require additional study to understand what they are.

Statistical Validation

Mathematically, if the AI model is working correctly, you'd expect certain statistical properties in the flagged dataset. The distribution of object types should match expectations. Rare objects should appear less frequently than common ones.

If statistical properties are off, it suggests the model has biases or is systematically misclassifying certain types of objects. Careful statistical analysis can identify these problems.

What Happens Next: Future Applications

The ESA researchers are already thinking about the next steps.

They want to apply Anomaly Match to other major astronomical archives. The James Webb Space Telescope, which launched in 2021, is already generating terabytes of data. That archive will eventually be massive. Applying anomaly detection early could reveal JWST discoveries as the archive grows.

They also want to make Anomaly Match available to the broader astronomical community. If other researchers can use the model on their own data, discoveries will accelerate. Someone studying a specific region of sky might find unexpected objects using the same approach.

There's also potential for the model to evolve. The current version detected anomalies based on visual appearance in images. Future versions could incorporate other data types: spectroscopy (light broken into wavelengths), time-series data (how objects change over time), multiwavelength data (the same object observed in different wavelengths).

Combining different data types could reveal anomalies invisible in single wavelength images. A galaxy might look normal in visible light but anomalous in infrared. An object's spectrum might be unusual in ways that color images don't reveal.

Citizen Science Integration

There's also potential for crowdsourcing the validation process. Astronomy has a strong citizen science tradition. Projects like Zooniverse have engaged millions of volunteers in classifying astronomical images.

Imagine: the AI flags anomalies, and then thousands of citizen scientists validate them. They could describe what makes each object interesting, propose classifications, even conduct follow-up research.

This could dramatically accelerate discovery while engaging the public in real science.

Commercial Applications

While astronomy is the focus here, the same techniques apply to commercial satellite imagery. Earth observation satellites generate massive amounts of data about land use, urban development, agriculture, water resources, climate.

Anomalies in that data could indicate environmental changes, illegal deforestation, mining activities, or other phenomena worth monitoring. Companies working on earth observation could use similar approaches to extract value from satellite imagery archives.

AI significantly reduces the time required to analyze astronomical data, offering a 14,400x time multiplier over human effort. Estimated data based on typical AI efficiency.

The Broader AI Revolution in Science

This discovery is part of a larger trend: AI is becoming essential infrastructure for scientific research.

We're not talking about AI replacing scientists. We're talking about AI as the research assistant that amplifies human capabilities. It handles the grunt work of pattern recognition and data processing. Humans handle the interpretation and judgment.

This is most visible in fields with massive data volumes: genomics, climate science, particle physics, medicine. But it's spreading to every scientific discipline.

Large language models can help write papers and summarize research. Machine learning can optimize experimental design. Computer vision can process microscopy images faster than human technicians. Reinforcement learning can design new molecules for drug discovery.

The scientists who'll be most successful in the next decade are the ones who learn to work effectively with AI systems. Not because they need to be AI experts, but because they need to understand what AI can and can't do, and how to ask it the right questions.

The Anomaly Match discovery is a perfect example. Two astronomers had a question: "What weird stuff is hiding in Hubble's archives?" They built an AI system to answer it. The system did the searching. They provided the scientific judgment.

That's the partnership model that's going to drive discovery for the next decade.

Challenges and Limitations: What Didn't Work

Not everything about this project went smoothly, even though the results are impressive. Understanding the limitations is as important as understanding the successes.

Training Data Bias

The model was trained on historical Hubble data. If certain types of objects are underrepresented in training data, the model might miss them in the full archive. For instance, if early Hubble observations didn't capture many very distant galaxies, the model might not recognize them as anomalous.

This creates a subtle problem: the model might be optimized to find anomalies similar to ones humans already knew about, potentially missing truly novel phenomena.

Computational Resource Requirements

While 2.5 days is fast in absolute terms, it still required significant computational resources. Not every researcher has access to GPU clusters or cloud computing budgets. This creates a barrier to adoption, limiting who can use this approach.

Democratizing the technology would require making it more computationally efficient or providing access to shared computing resources.

False Positives and Manual Review Burden

We don't know exactly how many images Anomaly Match initially flagged before human review filtered them to 1,400. If the model flagged, say, 10,000 or 100,000 candidates, that's still a lot of manual review.

In fields where there are fewer expert reviewers than in astronomy (where there are thousands of professional astronomers worldwide), this validation bottleneck could be a serious limitation.

The "Unclassified" Caveat

The model found several dozen objects that defied classification. That's intriguing, but it also suggests limitations. If 36 objects out of 1,400 are truly unclassifiable, most of the discoveries are objects humans already knew how to classify.

The interesting discoveries are exactly those unclassified objects, but they're also the rarest and least numerous.

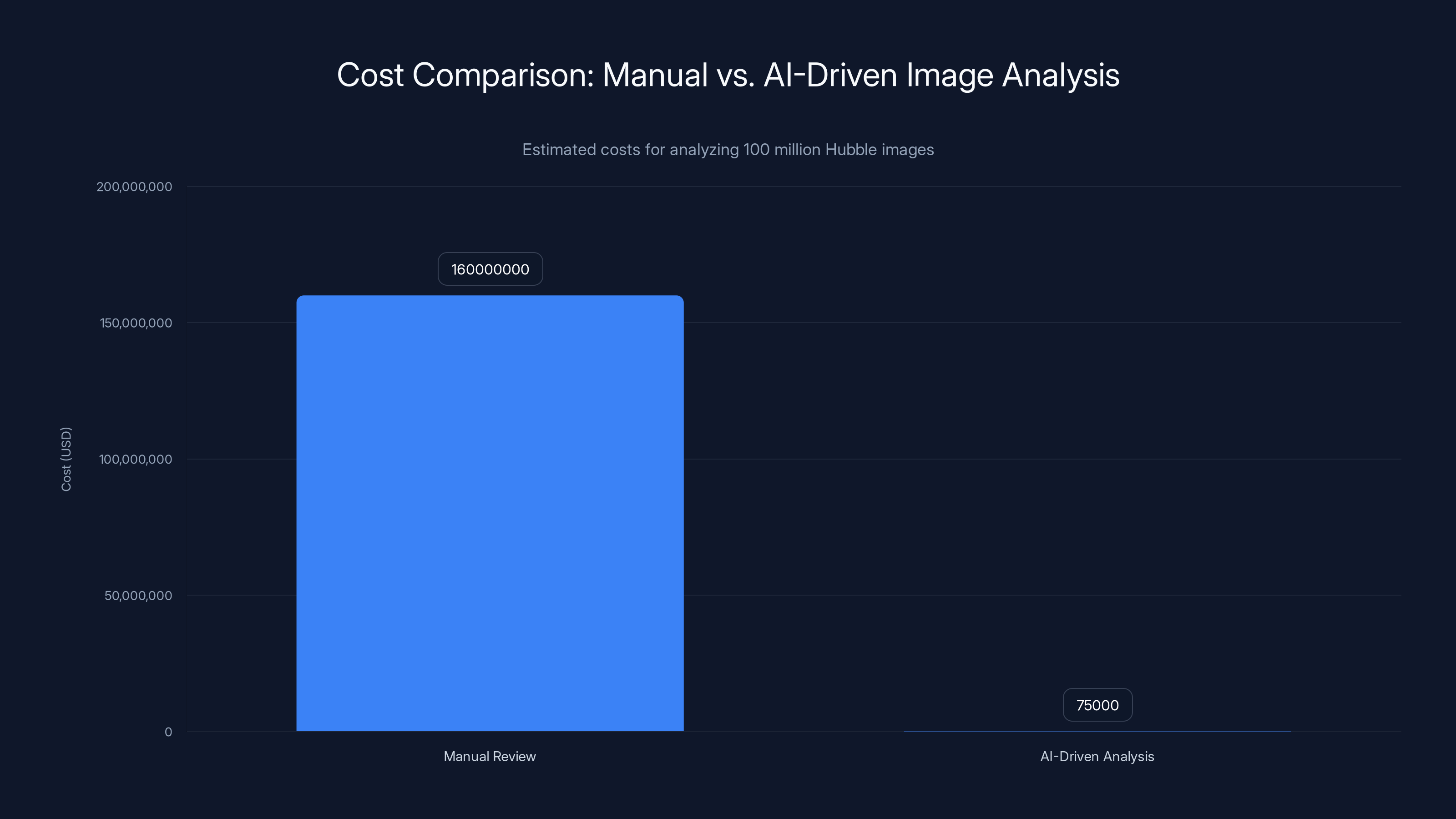

The AI-driven approach costs significantly less, with savings of approximately 1,000:1 compared to manual review, highlighting the economic efficiency of AI in large-scale data analysis.

The Economics: Cost-Benefit Analysis

Let's do some basic math to understand the economic case for AI-driven discovery.

If we estimate that a professional astronomer can carefully review about 100-200 Hubble images per day (being thorough enough to spot genuine anomalies), examining 100 million images manually would require:

At an average salary of

The Anomaly Match approach accomplished the same task in 2.5 days using computational resources worth perhaps

The cost savings are roughly 1,000:1. Even if you factor in the development time for the AI model, hiring specialist machine learning engineers, and validation time, the ROI is extraordinary.

More importantly, it's time savings. The 2.5-day timeline means discoveries happen in weeks, not over decades. In scientific research, that matters enormously. A discovery that might have taken 10 years to achieve through manual review happens immediately.

Comparative Case Studies: AI Discovery in Other Domains

The Anomaly Match approach isn't unique, though it's particularly elegant. Other domains have successfully used similar AI-driven discovery methods.

Medical Imaging and Rare Diseases

Radiologists interpret medical images: X-rays, CT scans, MRI images. Most patients have normal or easily recognizable pathology. But rare diseases can produce subtle imaging findings that even experienced radiologists might miss.

AI systems trained on millions of medical images can flag unusual patterns. They've been used to identify rare cancers, unusual anatomical variants, and atypical presentations of common diseases.

The economic case is similar to astronomy: AI can process imaging data faster than human radiologists, flagging the unusual cases for expert review. The combination works better than either alone.

Materials Science and Crystal Structure Discovery

Materials scientists use X-ray diffraction to determine crystal structures. The resulting diffraction patterns are images that need interpretation. Finding interesting new materials requires sifting through thousands of diffraction patterns.

AI systems have been trained to identify unusual crystal structures or phases from diffraction data. This has led to discovery of new materials with potentially useful properties.

Climate Modeling and Weather Prediction

Weather models generate forecasts by integrating data from sensors, satellites, and radar. Sometimes unusual patterns emerge in the data that might indicate extreme weather or atmospheric instability.

ML systems have been applied to detect these anomalous patterns, potentially enabling better severe weather prediction and early warning systems.

Each of these cases follows the same pattern: massive data volume, humans looking for unusual patterns, AI doing the heavy lifting of pattern recognition, human judgment providing validation and interpretation.

Best Practices for Implementing AI Discovery Systems

If you're considering a similar approach in your field, what should you know?

1. Define Your Anomaly Clearly

Before building an AI system, be clear about what "anomalous" means in your context. Is it statistically rare? Visually distinct? Functionally different? The answer shapes your AI architecture.

For Hubble images, anomalous meant "looks visually different from normal galaxies and stars." That's different from "extremely faint" or "unusually distant."

2. Start With Historical Data

Using archived data as your initial dataset is smart for several reasons:

- It's available immediately without waiting for new observations

- Results can be validated against historical knowledge

- The system can be tested and refined before deployment on real-time data

- There's no pressure to publish findings quickly

3. Prioritize Interpretability

When your AI flags something as anomalous, you want to understand why. Black box systems that flag items without explanation are less useful scientifically.

Consider architectures that provide some interpretability: attention mechanisms that highlight which parts of images matter, feature importance scores, or layered explanations.

4. Plan for Human Validation

Build validation workflows into your system design from the start. How will experts review AI outputs? What training will they need? How long does validation take per item?

Validation is often the bottleneck in AI-driven discovery. Plan accordingly.

5. Iterate and Improve

Your first version won't be perfect. The model will make mistakes. The flagging criteria might be too strict or too lenient. Plan to iterate, using feedback from expert review to improve the system.

This is an ongoing process, not a one-time implementation.

Ethical Considerations in AI-Driven Discovery

While this discovery is largely positive, there are ethical questions worth considering.

Bias in Training Data

If the training data (historical Hubble observations) contains systematic biases, the model inherits those biases. For instance, if certain regions of sky were observed more thoroughly than others, the model might be biased toward finding anomalies in well-observed regions.

Diversifying training data and auditing for bias are important safeguards.

Access and Equity

AI discovery systems require computational resources. Researchers with access to computing clusters can use these approaches; those without access cannot. This creates potential inequality in who gets to make discoveries.

Publicly funding access to shared computing resources for research could help level the playing field.

Intellectual Property and Credit

When an AI system makes a discovery, who gets credit? The researchers who built the system? The astronomers who validated the discovery? The institution that provided computing resources?

Scientific norms are still developing around this, but clarity will be important as AI-driven discovery becomes more common.

Future Directions: The Next Decade

Where does this technology go from here?

Multimodal Anomaly Detection

The current Anomaly Match works on optical images. Future versions could incorporate spectroscopy, photometry, and time-series data simultaneously. An object might look normal optically but be anomalous spectrally. Combining information across wavelengths could reveal richer anomalies.

Causal Reasoning

Current AI systems are correlational: they find patterns. But scientists care about causation: why does this phenomenon occur?

Incorporating causal reasoning into AI discovery systems could move from "here's something weird" to "here's something weird and here's why it happens that way."

Interactive Discovery

Imagine an interactive system where astronomers could ask questions: "Show me objects similar to this one." "Find rare examples of this phenomenon." "What changed about this object over time?"

AI systems that support conversational interaction could make discovery more intuitive and collaborative.

Automated Hypothesis Generation

Beyond finding anomalies, AI could propose hypotheses about why they exist. It could generate suggested follow-up observations or experiments. It could synthesize existing literature and suggest novel connections.

This would move AI from passive discovery support to active scientific collaboration.

FAQ

What is Anomaly Match and how does it work?

Anomaly Match is a machine learning system designed to identify objects in astronomical images that deviate from normal patterns. Rather than looking for specific known phenomena, the system was trained on millions of normal Hubble images to learn what typical looks like, then systematically scanned the archive flagging images that didn't match that pattern. This approach doesn't require pre-programmed categories, making it effective at finding unexpected phenomena that don't fit existing classifications.

How can an AI model process 100 million images in just 2.5 days?

The 2.5-day timeframe is possible through several technical optimizations working together. First, the model was designed to be computationally efficient, processing each image in milliseconds rather than seconds. Second, the computation was parallelized across GPU clusters, allowing thousands of images to be processed simultaneously. Third, data pipeline architecture was optimized to minimize file I/O bottlenecks by keeping images in memory buffers. These engineering decisions, combined with dedicated computational resources, enabled the remarkable throughput of over 460,000 images per hour.

What types of cosmic objects did the AI discover?

The nearly 1,400 anomalies flagged by Anomaly Match fell into several categories: merging and interacting galaxies (the majority), gravitational lenses that bend light into rings or arcs around massive foreground objects, jellyfish galaxies with distinctive tentacle-like structures of stripped gas, galaxies with unusual clumps of star formation, and most intriguingly, several dozen objects that defied any existing classification. These unclassified objects are particularly scientifically valuable because they might represent entirely new phenomena requiring new theoretical understanding.

Why is finding anomalies in Hubble data significant when the archive has existed for decades?

The Hubble archive contains 1.5 million observations generating 100 million image cutouts, far too much data for humans to manually review comprehensively. Historically, astronomers would conduct targeted searches for specific known objects they expected to find. This meant unusual phenomena that didn't match search criteria would remain undiscovered indefinitely. AI anomaly detection enables systematic, comprehensive searching that can find truly unexpected objects. Many of the 1,400 discoveries likely had been photographed decades ago but never recognized or classified because they didn't match standard search parameters.

How do astronomers validate that AI-discovered objects are real and not false positives?

Validation happens through multiple layers. First, human astronomers visually reviewed each image flagged by Anomaly Match to confirm it was genuinely anomalous. Second, cross-referencing with existing astronomical catalogs helps identify whether objects were previously known. Third, statistical analysis ensures the discovered object distribution matches expected patterns. Finally, for the most interesting cases, astronomers request follow-up observations with other telescopes to confirm the discoveries and understand them better. The fact that approximately 1,400 out of the flagged objects passed human review suggests the model achieved good precision in its flagging decisions.

Could this approach work on other astronomical archives and telescopes?

Absolutely, and that's already being explored. The same approach could be applied to archives from other major observatories including the Chandra X-ray Observatory, the James Webb Space Telescope, and ground-based surveys. Each archive potentially contains undiscovered phenomena waiting for AI-driven systematic searching. The researchers are actively working on adapting Anomaly Match for other datasets and making it available to the broader astronomical community, which should accelerate discoveries across multiple archives.

What are the limitations of current anomaly detection systems in astronomy?

Several limitations exist worth noting. The model's performance depends heavily on the quality and representativeness of training data, so systematic gaps in historical observations could lead to missed anomalies. The computational resource requirements create barriers for researchers without access to GPU clusters or cloud computing budgets. The validation bottleneck is significant, as human experts must review each flagged candidate. Additionally, most discoveries turned out to be phenomena humans already knew how to classify; the genuinely novel, unclassified objects were rarer. Finally, visual-only anomaly detection might miss objects that appear normal optically but are anomalous in other wavelengths or properties.

How might AI discovery evolve in the next decade?

Future development likely includes multimodal anomaly detection combining optical images, spectroscopy, and time-series data simultaneously. Systems could incorporate causal reasoning to not just find anomalies but explain why they occur. Interactive discovery interfaces might allow astronomers to ask sophisticated questions and explore anomalies conversationally. Automated hypothesis generation could propose why anomalies exist and suggest follow-up observations. Eventually, AI systems might move from passive discovery support to active scientific collaboration, working alongside human researchers to generate and test hypotheses about cosmic phenomena.

What does this discovery mean for the future of scientific research broadly?

The Anomaly Match project exemplifies a larger trend: AI becoming essential infrastructure for scientific research. Rather than replacing scientists, AI amplifies human capability by handling massive-scale pattern recognition and data processing while humans provide judgment, interpretation, and scientific context. This partnership model is spreading across scientific disciplines with large data volumes, from medicine and genomics to climate science and particle physics. Scientists in the next decade will increasingly need to understand how to work effectively with AI systems, not because they need to be AI experts, but because data-driven discovery demands it.

Key Takeaways

- AnomalyMatch AI model discovered 1,400 cosmic anomalies in Hubble archives in just 2.5 days, a task that would require 2,667 person-years of manual work

- Discoveries include merging galaxies, gravitational lenses, jellyfish galaxies, and several dozen unclassified objects representing genuinely novel phenomena

- The approach demonstrates how AI amplifies rather than replaces human expertise: the system finds patterns, astronomers provide scientific judgment

- This discovery model applies across scientific fields with massive data volumes including medicine, climate science, genomics, and materials science

- Future applications could involve multimodal anomaly detection, causal reasoning, and interactive discovery systems advancing scientific collaboration

Related Articles

- Is AI Adoption at Work Actually Flatlining? What the Data Really Shows [2025]

- State Crackdown on Grok and xAI: What You Need to Know [2025]

- Gemini 3 Becomes Google's Default AI Overviews Model [2025]

- Uber's AV Labs: How Data Collection Shapes Autonomous Vehicles [2025]

- Where Tech Leaders & Students Really Think AI Is Going [2025]

- Cognitive Diversity in LLMs: Transforming AI Interactions [2025]

![AI Discovers 1,400 Cosmic Anomalies in Hubble Archive [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/ai-discovers-1-400-cosmic-anomalies-in-hubble-archive-2025/image-1-1769600290827.jpg)