Introduction: The Age of the Founder Conglomerate

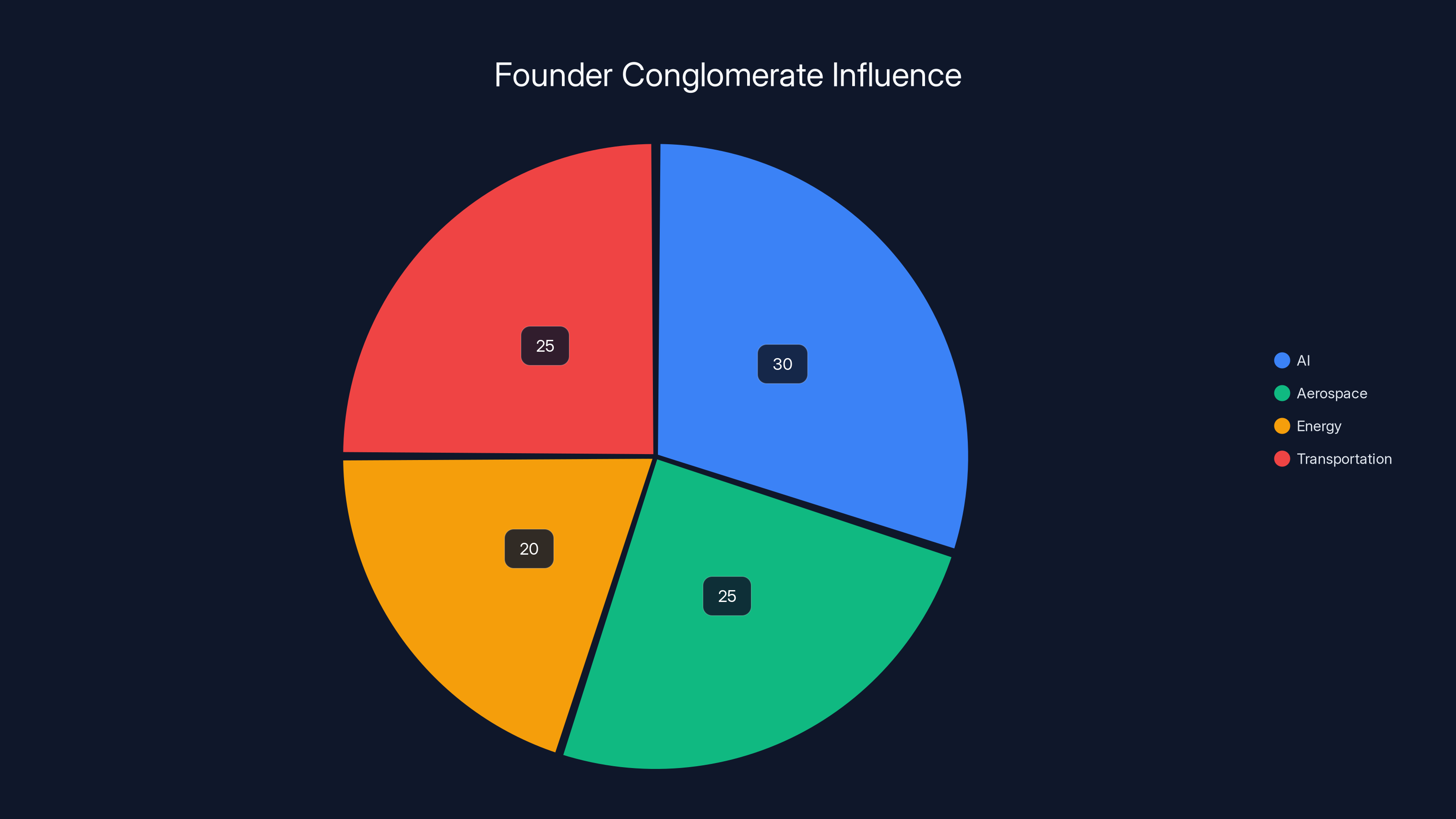

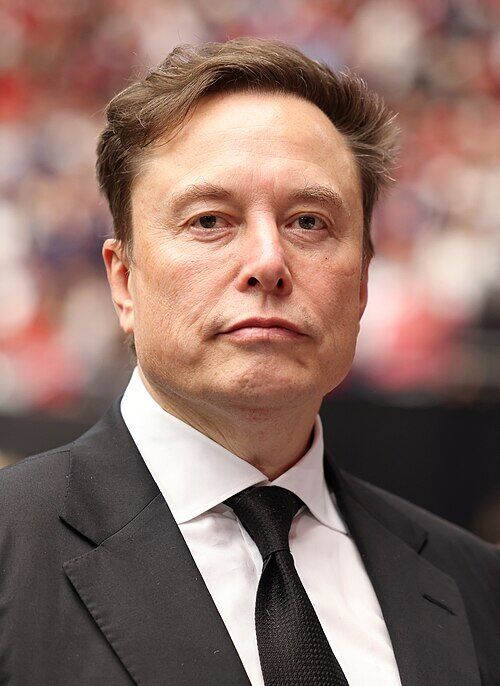

Elon Musk just pulled off something that would've been unthinkable five years ago. He merged SpaceX and xAI, essentially creating a personal holding company that operates across AI, aerospace, energy, and transportation. Not as separate divisions under a corporate umbrella, but as genuinely interlinked ventures where the same guy calls the shots across all of them.

This isn't just another tech deal. This is a fundamental shift in how power gets concentrated in Silicon Valley. We're watching the death of the traditional corporate board structure and the rise of what you might call the "founder conglomerate"—a model where one visionary doesn't have to answer to shareholders, doesn't have to compromise with committees, and can move at the speed of his own thinking.

The question everyone's asking now is: will others follow? Will Sam Altman try it? What about other founders who've been constrained by investor expectations or board governance? And maybe more importantly, what does this mean for innovation, for regulation, and for the future of how companies get built?

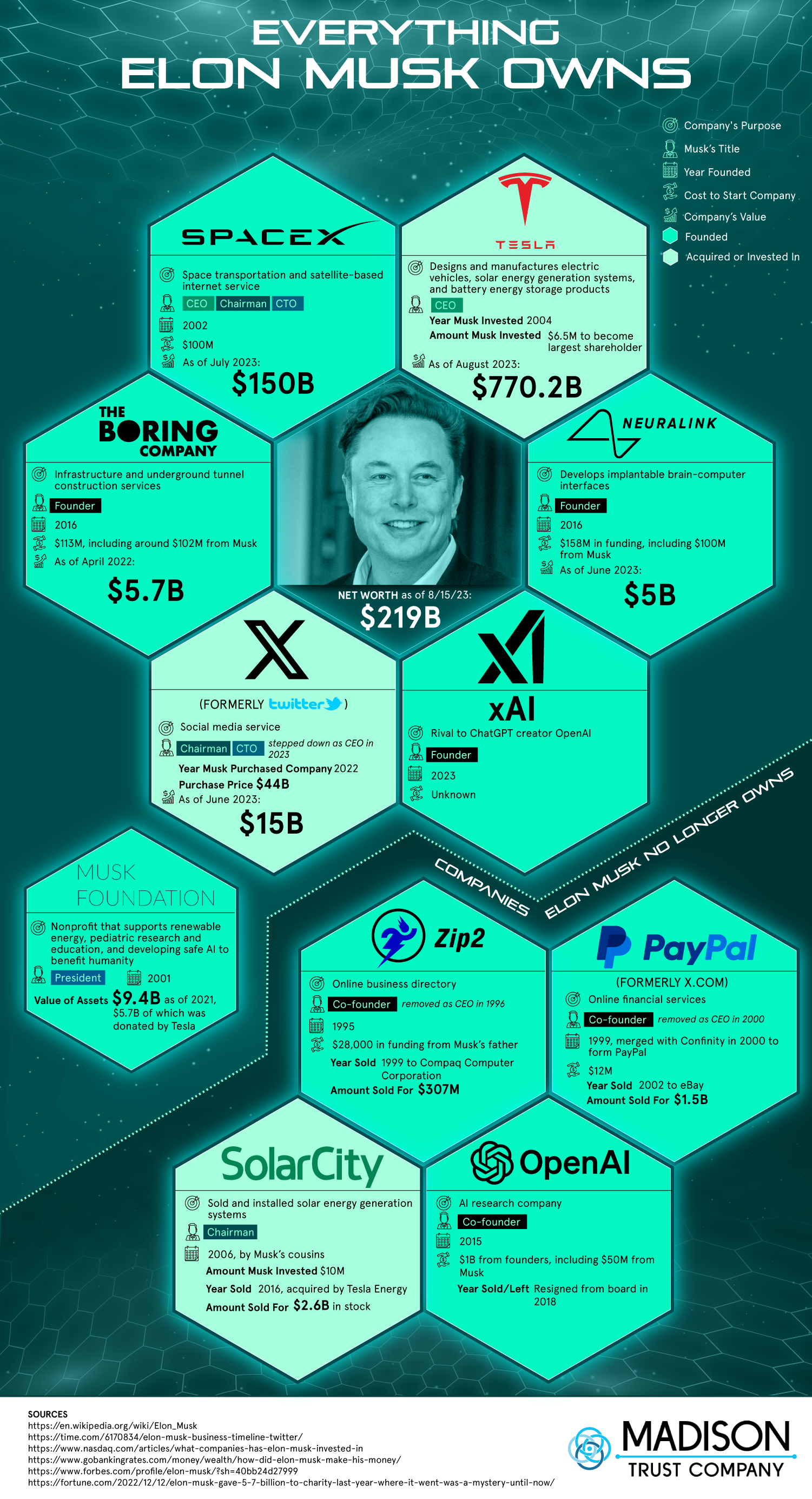

Musk has $800 billion in net worth. That's roughly equivalent to what General Electric peaked at during the height of the conglomerate era. The difference is, Musk built that wealth through direct founder control and aggressive vertical integration, not through careful board management and investor relations.

Here's what makes this moment so critical to understand: Musk's model works because he's willing to take bets that public markets would punish most CEOs for. He's willing to burn cash on projects that take five to ten years to pay off. He's willing to make decisions that upset shareholders. And because he controls the voting structure, he doesn't have to listen to them.

That's not just about Musk's personality. It's about the structural advantage that founder control actually provides when you're playing a long game in capital-intensive industries. Aerospace and AI both require massive, long-term bets. Quarterly earnings don't matter if your horizon is a decade out.

What we're seeing play out right now is nothing short of a rewriting of the rules for how founders can consolidate power and build influence across multiple domains. And whether you think that's brilliant or dangerous probably depends on where you sit.

The SpaceX-xAI Merger: A Case Study in Strategic Consolidation

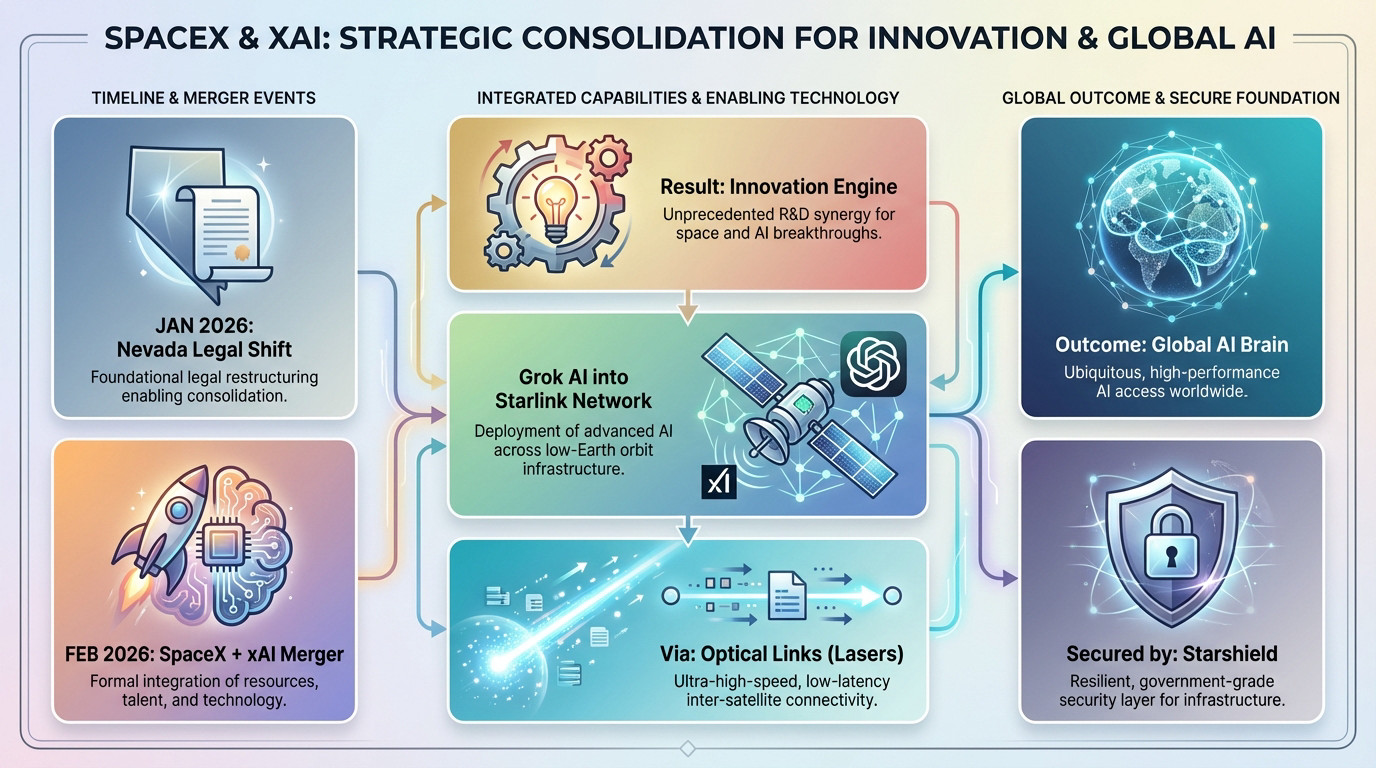

Let's start with what actually happened. Musk merged SpaceX and xAI, officially integrating them into a unified structure where both operate under common ownership with shared strategic direction. On the surface, this looks like a normal business consolidation. Two companies under one parent, operational efficiencies, shared resources.

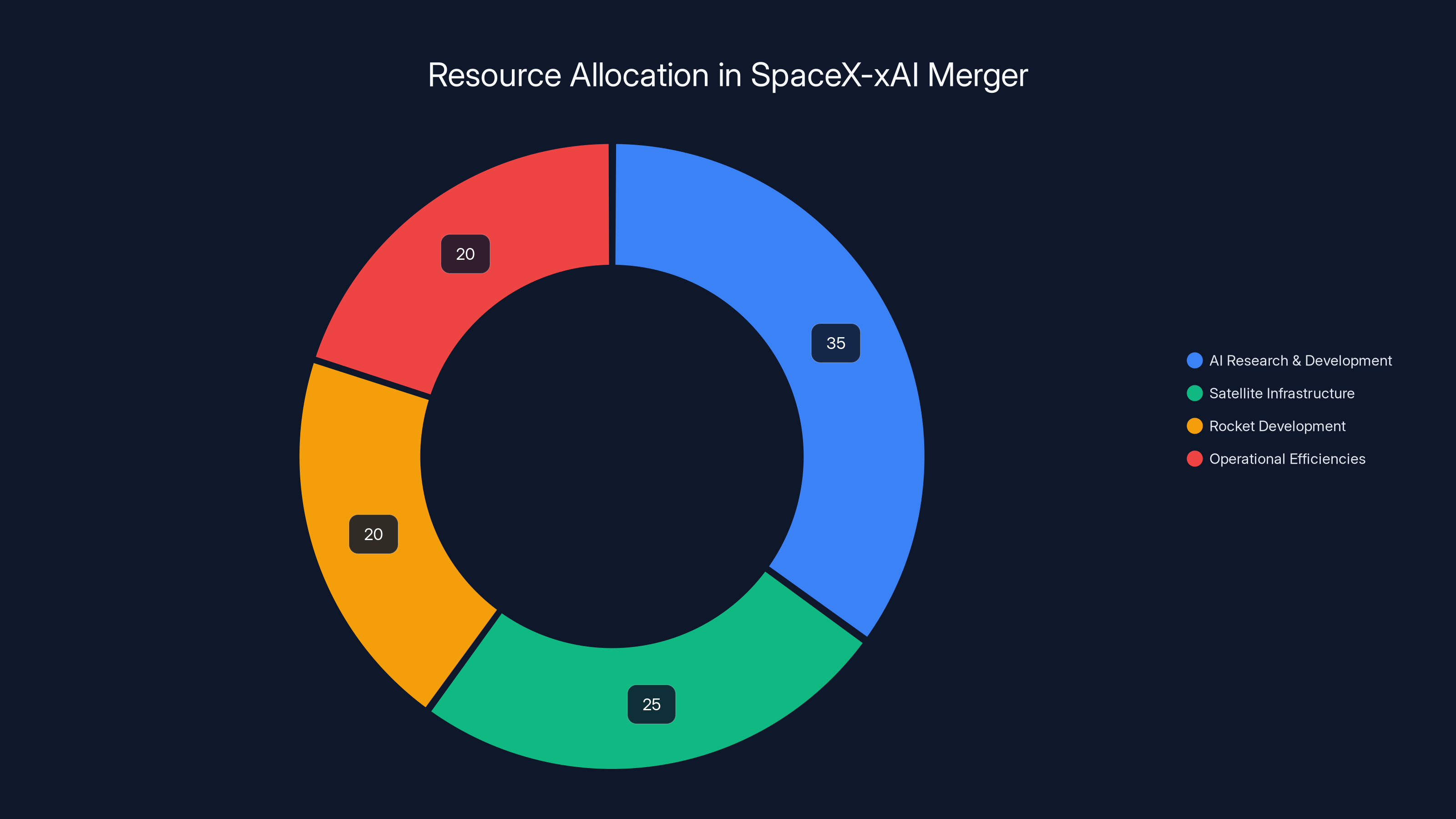

But the real story is different. SpaceX has already proven itself as a capital-generating machine. It's profitable, it has government contracts, it prints cash. xAI is still burning money on compute infrastructure and model development. That's an intentional strategy. SpaceX's cash flows directly into AI research. AI advances might eventually unlock new SpaceX applications. Starlink provides communication infrastructure that could serve AI applications.

This is vertical integration, but not in the traditional sense. It's not about controlling the supply chain to reduce costs. It's about creating a closed loop where technologies developed in one company immediately get deployed in another, where breakthroughs in one domain directly accelerate progress in the others.

Consider the computational requirements. Building cutting-edge AI models requires massive amounts of electricity and compute power. SpaceX has Starlink, which could eventually provide satellite-based computing distribution. xAI could benefit directly from cheaper, dedicated compute capacity. Meanwhile, AI improvements in logistics, materials science, and manufacturing could accelerate SpaceX's rocket development.

This isn't theoretical. Musk has explicitly said he sees these connections. The merger wasn't about financial engineering or tax optimization. It was about removing the friction that exists when two separately-governed companies try to collaborate.

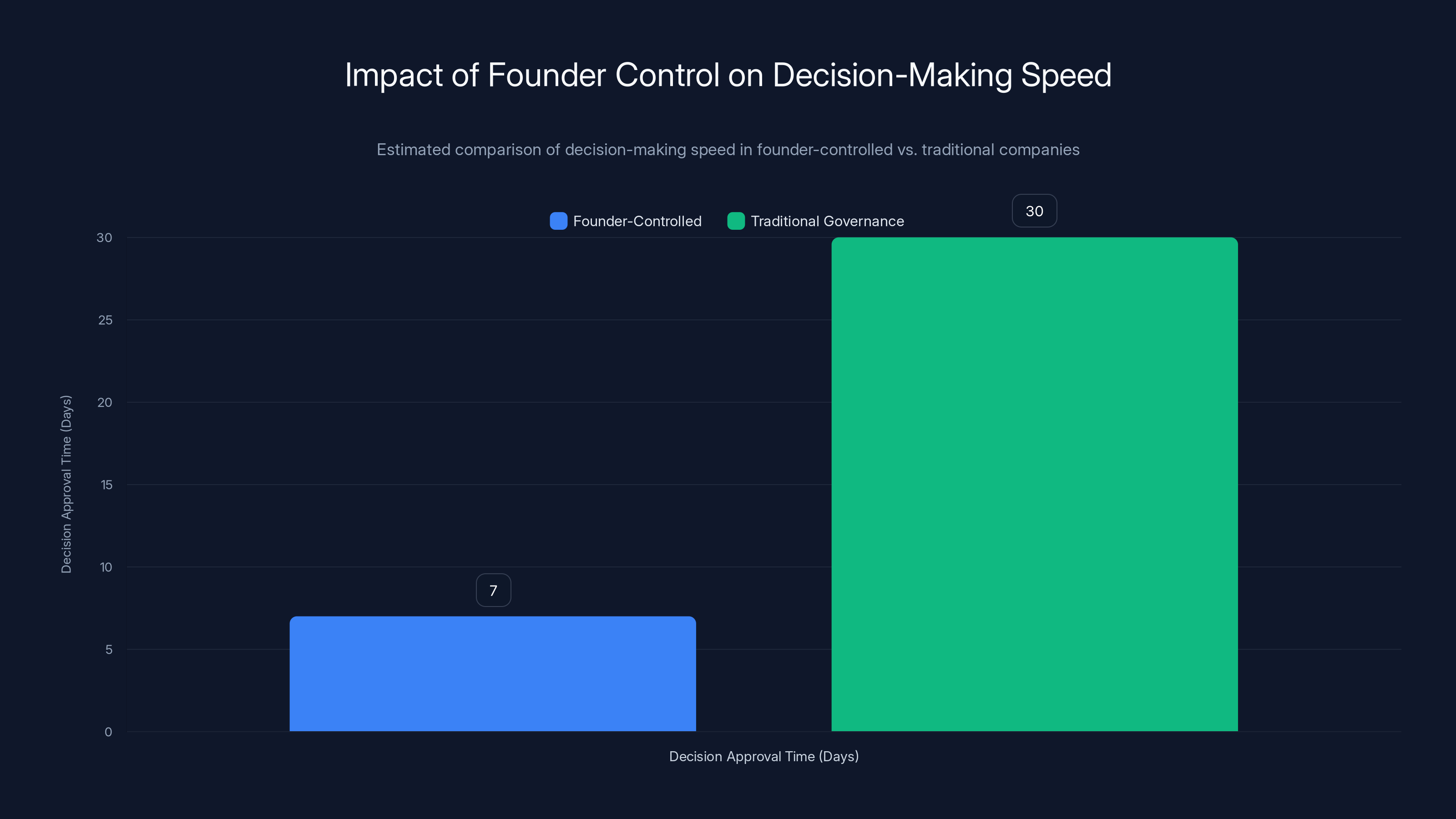

When you have separate boards, separate investor bases, and separate management structures, there are always delays. Legal reviews. Financial discussions about who pays for what. With a unified structure under founder control, those friction points disappear. A decision can be made in hours instead of weeks.

That speed advantage compounds. In AI especially, where the landscape changes monthly, that's worth real money. If Musk's companies can iterate two weeks faster than competitors because they don't have board meetings to schedule, that's a significant edge.

The consolidation also signals something important to the market: Musk is betting that the future belongs to integrated companies, not specialized ones. SpaceX isn't a rocket company anymore, it's an infrastructure company. xAI isn't just building models, it's building the infrastructure and satellite networks to deploy them globally.

Runable scores the highest in feature rating due to its AI-powered automation and cost-effectiveness at $9/month. Estimated data.

The Founder-Controlled Power Structure: Why Governance Matters

Here's where this gets really interesting. Traditional corporate governance exists for a reason. Boards provide oversight. Shareholders demand accountability. Quarterly earnings calls force transparency. These structures evolved because of historical disasters where CEOs with unchecked power made catastrophic decisions.

But there's a flip side that rarely gets discussed. Those same governance structures also slow down innovation. They force compromise on vision. They prevent the kind of long-term, irrational bets that sometimes create breakthrough progress.

Musk's approach is essentially saying: "I'll take the risks of being unchecked for the upside of being able to move fast and think long-term without compromise."

That's actually a rational trade-off in certain contexts. If you're building rockets that need to land themselves, or developing AI models that require billions in compute, the ability to make unilateral decisions on resource allocation is genuinely valuable. You're not dealing with consumer preferences that shift quarterly. You're dealing with physics and mathematics that play out over years.

The founder control structure also aligns incentives perfectly. There's no agency problem. The person making decisions about long-term investment bears the full consequences of being wrong. Musk's net worth is tied directly to whether SpaceX and xAI succeed or fail. That's different from a professional CEO who can walk away with a golden parachute.

Of course, the downside is real. Without board oversight, there's no institutional check on bad decisions. There's no devil's advocate asking hard questions. Elon's confidence in his own judgment is probably calibrated higher than it should be for someone making trillion-dollar decisions.

But here's the thing that keeps getting missed: the traditional board structure wasn't perfect either. Boards can be captured by existing power dynamics. They can prevent necessary change. They can entrench mediocrity. A founder with unchecked control can actually move faster on fixing problems too.

The question isn't whether founder control or board governance is universally better. It's whether the trade-off makes sense for a particular business at a particular stage. For capital-intensive, long-horizon bets in AI and aerospace, the case for founder control is actually pretty strong.

The Regulatory Constraint: The Real Limitation on Founder Power

Here's what actually limits Musk's power, and it's not what most people think. It's not shareholders. It's not boards. It's regulation.

You can consolidate as much as you want, but if the government decides your business model is problematic, game over. SpaceX depends on government contracts and FCC licenses. xAI's compute capacity depends on electricity grid access and potentially export controls. Starlink depends on regulatory approval in every country where it operates.

Musk's companies exist at the intersection of government jurisdiction. Aerospace is regulated by the FAA. AI could be regulated by FTC or new AI-specific bodies. Automotive is regulated by NHTSA. Energy is regulated by FERC. Starlink is regulated by the FCC.

What limits Musk's ability to consolidate power isn't internal governance. It's the external wall of regulatory constraints. And those constraints are ultimately driven by public opinion and political pressure.

That's actually a bigger story than most people realize. The traditional corporation evolved partly because it was a structure that governments understood and could regulate. With founder control, you have concentration of power that's harder to regulate. Do you fine the company? That punishes employees and shareholders who had no say. Do you remove the founder? That requires different legal authority than what currently exists.

The regulatory response to Musk's consolidation will be telling. If governments decide that the concentration of power in his hands is a political problem, they have tools to break it apart. They can impose antitrust enforcement. They can refuse to grant new licenses. They can require structural separation.

Meanwhile, Musk's strategy seems to be moving faster than regulation can keep up. Build, prove success, normalize the model, then defend it politically. It's not a new strategy, but it's effective when you're operating across multiple regulatory domains simultaneously.

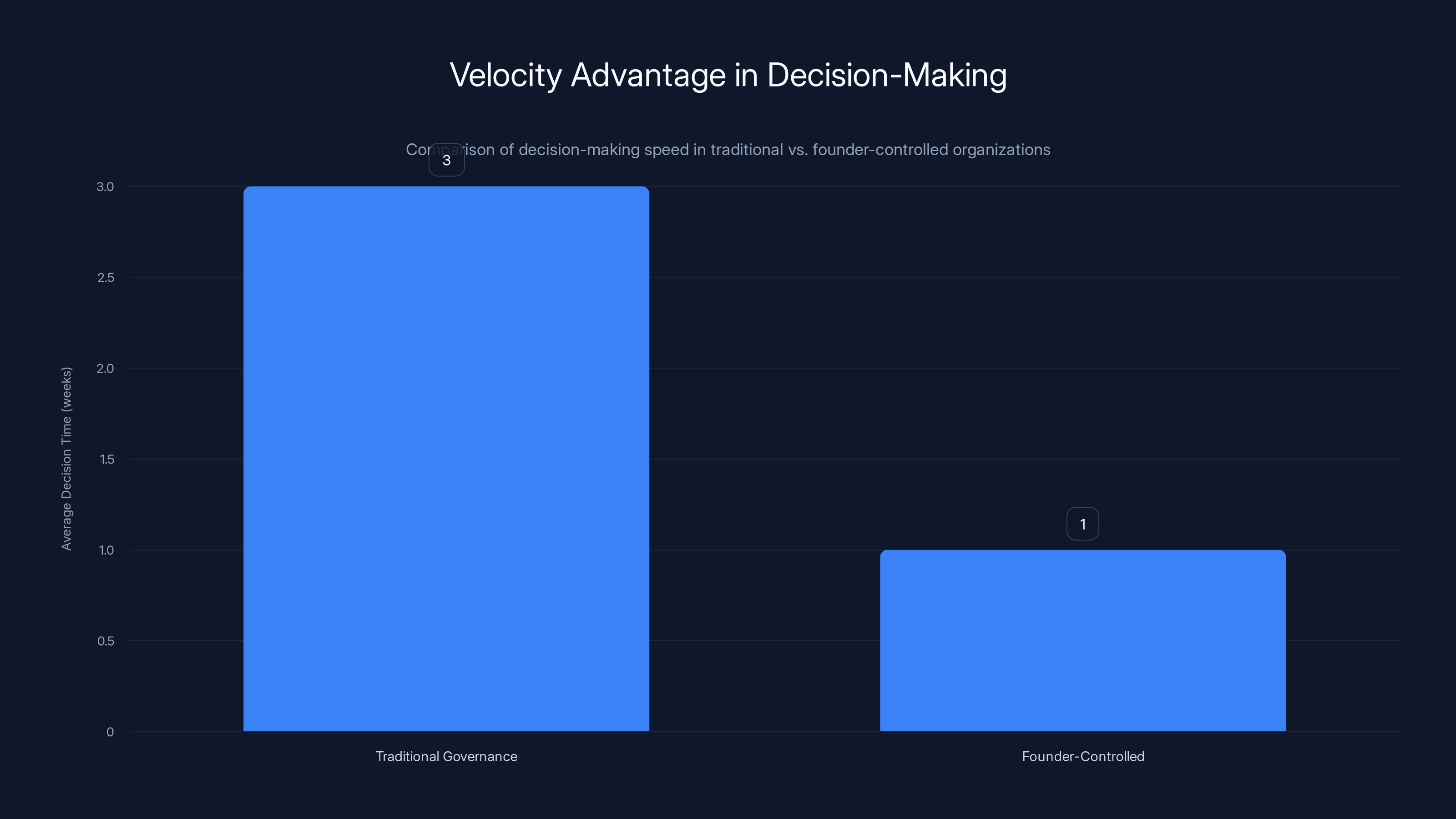

Founder-controlled companies like SpaceX-xAI can make strategic decisions approximately 4 times faster than those with traditional governance structures. Estimated data.

Founder Psychology: How Conviction Drives Different Decisions

There's a psychological dimension to founder-controlled companies that's worth examining. Musk has specific convictions about the future. He believes AI needs to develop in parallel with other technologies. He believes humanity needs to become multiplanetary. He believes Earth needs to transition to sustainable energy.

These aren't just business goals. They're quasi-religious convictions. And because Musk controls the capital allocation across his companies, he can organize entire corporate strategies around advancing these convictions.

A professional CEO, no matter how brilliant, is constrained by needing to convince boards and shareholders that every bet makes financial sense within a normal corporate framework. Musk doesn't have that constraint. If he thinks AI and space exploration need to develop in parallel, he can make that happen by allocating resources without needing to justify it on quarterly earnings.

Now, this can lead to both brilliant and terrible decisions. Musk's conviction about the importance of rapid AI development has probably accelerated progress in areas that other companies moved more cautiously on. His conviction about electric vehicles basically forced the legacy auto industry to take them seriously.

But it also means that when Musk is wrong about something, there's no institutional check to catch him. If he decides to pursue a technology direction that's actually a dead end, the company will follow him there because he has the power to make it happen.

That's the trade-off with founder conviction: it can be a superpower or a delusion, and from the inside, they often look the same.

The psychology also matters for how founder-controlled companies attract talent. People who want to work with visionary founders accept different rules. They're buying into the founder's vision, not the company's quarterly numbers. That can attract incredibly talented people who are motivated by the mission, not the compensation.

But it also creates risk. If the founder's vision turns out to be wrong, or if the founder becomes unstable, there's no institutional structure to protect the company or the employees. You're essentially betting on one person's judgment.

The Blueprint Effect: Can Others Actually Replicate This Model?

The real question everyone's asking is whether this model becomes a template that other founders try to copy. Can Sam Altman do this at OpenAI? Can other AI founders consolidate power the same way?

There are obstacles that don't apply to Musk. First, Musk's credibility. He's proven that he can build and scale companies in hard domains. When he says he wants to consolidate control, investors believe he has a vision. Most founders, even successful ones, don't have that level of proven track record across multiple domains.

Second, the capital required. Consolidating multiple companies requires having enough wealth or control that you can afford to absorb losses in growth-stage companies without pressure from external investors. Musk's net worth and his control structure gave him that. Many other founders don't have equivalent firepower.

Third, the founders need to own the companies they're trying to consolidate. Musk owns SpaceX outright and had control of xAI. If you're a CEO of a public company, you can't just merge it with another company you own. You need shareholder approval. You need board approval. You're constrained by the same governance structures that Musk escaped.

Sam Altman at OpenAI is actually in an interesting position. OpenAI is currently structured as a capped-profit company, not a traditional corporation. Altman has significant control but also institutional investors with board seats. If he wanted to consolidate OpenAI with another company, he'd face resistance from investors who want to understand why the merger creates value.

Musk could consolidate because he controlled both entities and didn't need anyone's permission. That's a constraint that limits replication. Most founders, at some point, take on external capital, and external capital comes with governance strings attached.

There's also the question of whether consolidation actually makes sense for other domains the way it does for aerospace and AI. Musk's companies have genuine operational synergies. SpaceX's infrastructure improvements directly benefit xAI. AI improvements directly benefit SpaceX. If you're consolidating a SaaS company with a hardware company, the synergies might not be as obvious.

So while the SpaceX-xAI merger might inspire other founders to think about consolidation, the actual ability to replicate it is probably limited to founders with: massive personal wealth, outright ownership of the companies they want to merge, and genuine operational synergies between the businesses.

That's a small subset of the founder community. Which means we're probably not looking at a broad shift toward founder-controlled conglomerates. We're more likely looking at one person, in one moment, with unique leverage, pulling off something that becomes a famous case study rather than a widely-copied blueprint.

Velocity and Innovation: The Actual Performance Advantage

Musk has been explicit about his thesis: "Tech victory is decided by velocity of innovation." That's not just a catchy phrase. It's the core justification for his organizational model.

The argument goes like this: in rapidly evolving fields like AI and aerospace, the company that iterates fastest wins. You can't plan for a five-year horizon because the landscape will change too much. You need to make decisions quickly, learn from them, and adjust.

Traditional governance structures are designed around stability and risk management. Quarterly reporting. Board approvals. Fiduciary duties. Shareholder rights. These all create friction when you're trying to move fast.

By consolidating under founder control, you reduce that friction. A decision that might take three months to get through a board approval process takes a week. Resources can be reallocated immediately instead of requiring budget cycles. Talent can be moved between projects based on current priorities instead of existing org structure.

That's a real advantage. It's not huge, but in a competitive race it compounds. If you're two weeks faster than your competitor on every major decision, and there are twenty major decisions a year, that's forty weeks of advantage annually. Across multiple years, that's the difference between being a market leader and a follower.

The question is whether that velocity advantage is worth the trade-offs. You lose institutional memory because you're not documenting decisions extensively. You lose the benefit of debate because there's less formal review. You lose stakeholder buy-in because fewer people are involved in decisions.

In some contexts, that's a terrible trade-off. In others, it's exactly what you need.

For AI development, velocity probably does matter more than institutional process. AI models improve when you train them more, iterate faster, and test more variations. The companies that can run more experiments with fewer approval cycles probably do have an advantage.

For aerospace, velocity is also critical but constrained by physics and regulatory testing. You can't go faster in rocket development just by having fewer meetings. You have to pass static tests, then flight tests, then get regulatory approval. SpaceX's advantage isn't that they move faster through internal processes. It's that they've engineered processes that are fast while still being safe.

So the velocity advantage is real, but it's not a universal advantage. It's specific to business models where iterative speed actually translates to competitive advantage.

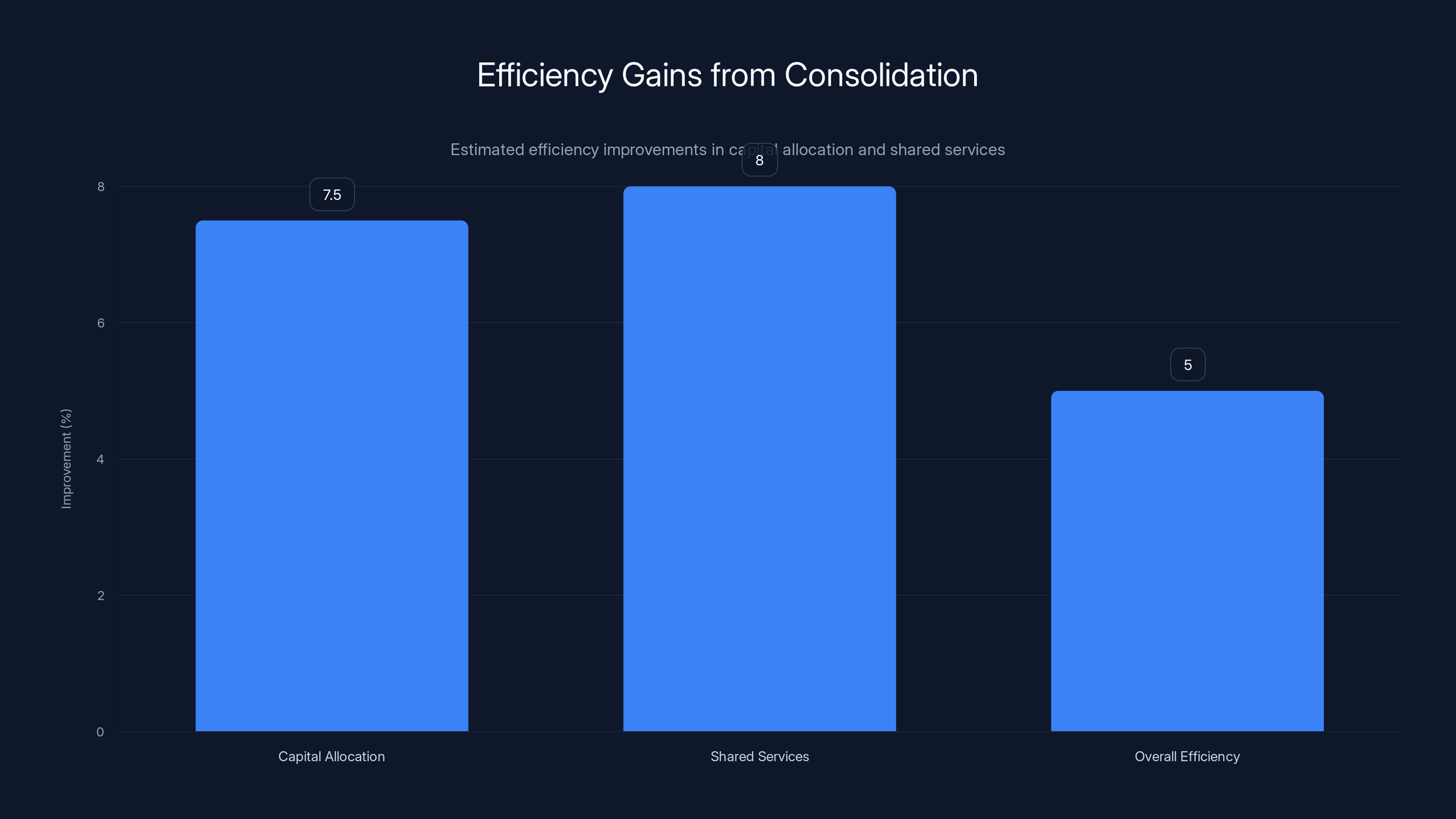

Estimated data suggests modest efficiency gains from consolidation, with 5-10% improvement in capital allocation and shared services.

Capital Allocation: The Strategic Superpower

One of the biggest advantages of consolidating companies under founder control is the ability to allocate capital across them based on strategic vision rather than individual company ROI.

In a traditional corporate structure, each business unit needs to demonstrate financial performance. There are internal conflicts about resource allocation. The profitable units subsidize the experimental ones, and there's always pressure to starve the experimental units to maximize current returns.

With founder control across multiple companies, you can allocate capital based on a longer-term strategic thesis. If Musk thinks AI is more important than near-term SpaceX profitability, he can move capital from SpaceX to xAI. He doesn't need to convince a board that this is good for SpaceX shareholders. He just does it.

That's incredibly powerful for executing on a long-term vision. It's terrible for short-term returns. It's great for long-term positioning.

Consider the actual capital flows. SpaceX generates billions in revenue, much of it from government contracts. Some of that can be diverted into compute infrastructure for xAI. That compute infrastructure accelerates AI development. Advanced AI could eventually unlock new SpaceX applications. Meanwhile, Starlink provides infrastructure that both companies benefit from.

A traditional investor looking at individual company returns might ask: why is SpaceX subsidizing xAI when SpaceX could be more profitable independently? The answer is that the founder has a strategic thesis that connects all these pieces, and he's willing to sacrifice short-term returns in individual companies to maximize long-term returns across the portfolio.

That requires either massive confidence or massive delusion, and often it's hard to tell which. But structurally, founder control enables this kind of strategic capital allocation in a way that typical governance doesn't.

The flip side is that founder's judgment failures get amplified across the portfolio. If Musk makes a bad strategic bet that affects how capital gets allocated, that bad decision ripples across all of his companies. There's no institutional check. There's no separation that limits contagion.

Precedent and Historical Parallels: The Conglomerate Era Revisited

This isn't actually the first time Silicon Valley has seen this kind of consolidation of power. The tech industry explicitly moved away from it because the traditional conglomerate model didn't work in practice.

Back in the 1980s and 1990s, you had conglomerates like ITT and Gulf+Western that tried to own everything. The logic was similar to what Musk is doing: operational synergies, capital allocation efficiency, leveraging expertise across domains.

What actually happened was that conglomerates became unwieldy. The businesses were too different from each other. They competed for resources internally. The core competency in one business didn't transfer to others. Investors didn't understand the business models, so they applied lower valuation multiples to diversified companies than to focused ones.

Eventually, the market rewarded companies that focused on what they did best. Conglomerates got broken apart. Investors preferred pure-play companies because they were easier to understand and easier to value.

So why would Musk's approach succeed where previous conglomerate models failed?

Partly because the businesses have actual operational synergies. SpaceX and xAI aren't as disconnected as, say, ITT's defense business was from its hotels. Partly because the founder controls everything personally, so there aren't the internal political dynamics that doomed historical conglomerates. Partly because this is in tech and AI, where velocity and iteration actually do create tangible advantages.

But there's also a possibility that this doesn't work at scale. That maintaining control across multiple billion-dollar companies while running them in coordination becomes impossible as they grow larger. That regulatory pressure forces separation. That the founder's judgment, which was brilliant at smaller scale, fails when applied across larger entities.

We won't actually know until it plays out. Musk's companies are still relatively young in historical terms. SpaceX is impressive but not yet generating the kind of mass-market impact that would attract serious antitrust attention. xAI is still in the early stages of development.

The historical precedent suggests that founder-controlled conglomerates are hard to sustain long-term, but Musk is working with different leverage and different industries than previous conglomerates, so the historical precedent might not apply.

The Sam Altman Question: Can Leaders Replicate the Musk Model?

Everyone's asking whether Sam Altman, Satya Nadella, or other major tech leaders will try to consolidate similar power structures.

The honest answer is probably: some will try, most won't succeed.

Sam Altman at OpenAI is probably the closest analog to Musk, and even he faces different constraints. Altman didn't start OpenAI with personal capital the way Musk started SpaceX with his own money. OpenAI has institutional investors with board seats. The cap-profit structure creates governance complexity. Microsoft is a major investor and partner, which constrains how freely Altman can move capital.

If Altman wanted to consolidate OpenAI with another company—say, an infrastructure or robotics company—he'd need approval from his board. And the board would want to understand why the consolidation creates value. There would be analysis. There would be negotiation.

Musk didn't face that friction because he controlled both entities. That's the critical difference.

Most other successful founders in tech already took venture capital or went public, which means they lost the ability to consolidate companies without stakeholder approval. The founders still operating with founder control are typically either in earlier stages or in businesses that haven't required huge amounts of capital.

There's also a personality dimension. Musk is willing to stake his reputation and wealth on his own judgment in a way that most other leaders aren't. Most founders take on boards and external investors partly because they want institutional legitimacy and because they're nervous about making billion-dollar bets on their own judgment.

Musk actively seeks out billion-dollar bets on his own judgment. That's not a widely shared personality trait among founder-CEOs.

So while the Musk model might inspire others to think about consolidation, the practical ability to execute it is probably limited to a small number of founders who: never took on constraining external capital, have the personal wealth to absorb large losses, and have the confidence to make unilateral strategic bets.

That's a pretty exclusive club.

Founder-controlled organizations can make major decisions in 1 week compared to 3 weeks in traditional governance, offering a significant velocity advantage. Estimated data.

Regulatory Implications and Government Response

Here's where this gets politically important. The concentration of power in Musk's hands across aerospace, AI, energy, and communications is starting to create regulatory friction.

There's a reason we have antitrust law. There's a reason we're skeptical of monopolies. There's a reason we want to limit concentrated power. It's not just about economic efficiency. It's about political power.

Musk's companies control critical infrastructure: satellites (Starlink), launch capacity (SpaceX), AI (xAI), energy (Tesla), tunnels (Boring Company). As these consolidate under founder control, you have one person's judgment determining infrastructure that increasingly affects everyone.

Governments are noticing. There's talk of antitrust enforcement. There's talk of requiring structural separation between national security-sensitive businesses and consumer-facing ones. There's talk of additional regulation on AI specifically.

Musk's approach is to move fast and make the consolidated structure functional before regulation catches up. If SpaceX-xAI integration becomes genuinely valuable and creates real efficiencies, then breaking it apart looks like regulatory punishment, not fair competition.

But if the integrated structure starts showing signs of abuse of power—like using SpaceX infrastructure to benefit xAI, or vice versa—then the case for regulatory intervention becomes much stronger.

The wildcard is politics. Musk's political influence is significant and growing. He's not just a businessman anymore. He's a political actor. That creates both opportunities and vulnerabilities. It creates opportunities because he can potentially defend his business interests politically. It creates vulnerabilities because political opposition could coalesce around limiting his power.

The regulatory response to founder-controlled conglomerates will probably determine whether this becomes a new model or a one-off anomaly specific to Musk.

Technology Transfer and Cross-Pollination Effects

One of the genuine advantages of consolidating SpaceX and xAI is the ability to move innovations between companies more easily.

AI advances in one domain can immediately get applied to another. Materials science improvements benefit both companies. Optimization techniques developed for one problem space transfer to another.

That's not hypothetical. Rocket guidance systems use optimization algorithms that look a lot like machine learning. Machine learning optimization could improve rocket control systems. The companies can share research, data, and talent more freely when they're unified.

In a traditional structure where SpaceX and xAI are separate companies, that collaboration still happens, but it's slower. You need licensing agreements. You need discussions about who owns what intellectual property. You need contracts defining how one company can use the other company's innovations.

With founder control, you say "apply this to that problem" and it happens immediately.

That efficiency gain is real. It's probably worth 10-20% faster progress on certain problems, maybe more. That's meaningful in a competitive race.

The downside is that innovations developed in one company environment get forced into another where they might not be appropriate. If an optimization technique works great for AI training, it might not actually improve rocket guidance even if the math looks similar. You lose some of the organizational separation that exists for good reasons.

But overall, for domains where genuine cross-pollination is possible, consolidation under founder control does create advantages.

The Founder's Exit Problem: What Happens When the Founder Retires?

Here's the uncomfortable question that doesn't get asked enough: what happens to this structure when Musk is no longer running things?

Musk is 53 years old. He could actively run companies for another 20-30 years. But what happens after that?

If Musk dies or steps back, these consolidated companies have a problem. There's no institutional structure to handle succession. There's no board that's trained on strategy. There's no clear leadership pipeline because Musk has been making all the important decisions.

Traditional governance structures exist partly to handle succession. Boards develop backup leadership. Companies operate without depending on any single person's judgment. It's less exciting, less visionary, but more sustainable.

Musk's structure is optimized for his personal control and judgment. The moment that disappears, the advantage evaporates. You might actually need to implement traditional governance at that point.

This is actually the strongest argument for regulatory intervention. From a long-term stability perspective, you don't want critical infrastructure depending on any single person's longevity.

Some of Musk's companies have addressed this with succession planning, but it's always secondary to Musk's continued leadership. SpaceX has strong leadership beneath Musk, but everyone knows that major decisions still funnel through him.

The founder exit problem is why traditional companies evolved boards and governance structures. It's not just bureaucratic overhead. It's institutional continuity.

Musk's approach works brilliantly while Musk is healthy and active. What happens after is an open question.

Estimated data shows that founder-controlled companies like Musk's have significant influence across AI, aerospace, energy, and transportation sectors. This reflects the growing trend of founder conglomerates reshaping industries.

The Talent Recruitment and Retention Dynamics

Consolidating companies under founder control changes how you recruit and retain talent. It becomes less about compensation and benefits, and more about working directly with the founder on their vision.

The best engineers, scientists, and operators are often willing to take lower compensation to work with someone they respect on problems they find meaningful. Musk's consolidation of SpaceX and xAI means the absolute best AI researchers might now be willing to work at xAI if they believe that Musk is building something fundamental.

That's an advantage in recruiting top talent. You attract people who are motivated by mission, not compensation.

It's also a risk. If the founder's vision turns out to be misguided, or if the founder becomes difficult to work with, you lose that talent attraction. And because the company is dependent on the founder's vision, losing talent cascades into losing institutional knowledge.

Traditional companies are somewhat insulated from founder dysfunction. If a CEO becomes a problem, the board can replace them. In a founder-controlled company, the founder is the company. If the founder has problems, the whole organization feels it.

Musk's personnel decisions are well documented. He'll fire people quickly if he thinks they're not contributing. He'll demand extreme work hours. He'll make decisions that personnel departments in traditional companies would never allow.

Some people thrive in that environment. Others burn out. It creates high-performance pockets and also high-churn areas.

For recruiting top talent, founder control is an advantage. For retaining mid-level talent or building stable, sustainable organizations, traditional governance is probably better.

Musk's companies tend to be high-performance but also high-burn. People come, work incredibly hard, and either move to the next challenge or leave tech entirely.

Economic Efficiency and Resource Allocation at Scale

Is consolidation actually more efficient? That's the core economic question.

There are genuine efficiencies in having shared infrastructure, shared IT, shared legal, shared admin across companies. You don't need duplicate functions.

But there are also inefficiencies. One company's needs might not match another's. Compromising on infrastructure to serve both can be suboptimal for both. A custom solution for one company that wouldn't work for another creates coordination problems.

Historically, the research on conglomerate efficiency is mixed. You see some cost reductions in shared services. You see capital allocation advantages. But you also see overhead that comes from managing the complexity of multiple different businesses under one roof.

The net effect seems to depend heavily on how related the businesses are. If they have genuine operational synergies, consolidation is more efficient. If they're completely different businesses that happen to be under one owner, consolidation can actually be less efficient.

SpaceX and xAI probably sit in the middle. There are some genuine synergies around infrastructure and talent. But they also serve different markets with different customers and different timelines.

The efficiency gains are real but probably not huge. Maybe 5-10% improvement in capital allocation efficiency, maybe some cost savings in shared services. Meaningful, but not transformational.

The real advantage isn't economic efficiency. It's strategic flexibility and speed. Being able to make unilateral decisions about capital allocation across companies is worth more than the modest efficiencies you gain from consolidation.

Long-Term Sustainability and Institutional Risk

Musk's model is optimized for the present moment and the next 5-10 years. What happens when the companies mature? What happens when the industries commoditize? What happens when Musk is no longer available to make decisions?

These are hard questions without answers. The model works right now because Musk's vision is compelling, the industries are developing rapidly, and his personal involvement creates advantages.

But institutions built around one person are inherently fragile. They're great for explosive growth and breakthrough innovations. They're terrible for long-term stability.

The most likely outcome over the next 20-30 years is either: the consolidated companies remain unified but institute formal governance structures once Musk steps back, or they get broken apart at some point because regulatory or market pressure makes consolidation disadvantageous.

Historically, founder-controlled companies eventually become professionally managed companies, usually at a transition moment like founder retirement or company maturation. That happened with Apple, with Microsoft, with Amazon to some extent.

Musk might be different. He might remain actively involved in his companies for decades. His companies might genuinely benefit from consolidation in ways that historical companies didn't.

But betting that this structure persists indefinitely is probably overconfident. Betting that it persists for the next 10-15 years while Musk is actively running things is probably reasonable.

Estimated data shows a significant portion of resources allocated to AI R&D (35%) and satellite infrastructure (25%), reflecting the strategic focus of the merger.

The Future of Founder Power: What This Means for Innovation

What does the Musk model mean for how innovation happens in the future?

It suggests that the traditional pathway—start a company, raise venture capital, go public or get acquired—might not be the only way to build large impact. Founders who are willing to maintain control, who have the capital to fund their own growth, and who can attract talent and customers without external validation might actually be able to build larger, more integrated organizations than the traditional venture path allows.

That's not universal. Most founders don't have the wealth or credibility to fund their own companies. Most innovations require external capital. But for founders in domains where they can fund growth—either through profitable operations or through massive personal wealth—maintaining founder control is an option.

We might see more founder-controlled companies in AI specifically, because AI companies are increasingly profitable and can fund their own growth. We might see fewer in biotech or deep tech, where capital requirements are huge and funding timelines are long.

The consolidation of founder-controlled companies might also accelerate. If you can operate without board constraints, why not combine multiple companies under founder control? SpaceX plus xAI plus Neuralink plus Tesla all under one decision-maker could theoretically be more efficient than managing them separately.

But the regulatory limit on consolidation is probably the binding constraint. At some point, concentrating that much power in one person's hands becomes a political problem, regardless of economic efficiency.

Comparing Founder Control to Professional Management

Let's actually compare the models:

Founder-Controlled:

- Advantages: Speed, vision alignment, long-term focus, rapid decision-making, elimination of agency problems

- Disadvantages: Succession risk, limited external perspective, potential for founder error, limited institutional stability

Professionally Managed:

- Advantages: Institutional continuity, diverse perspectives, specialization, formal governance, separation of duties

- Disadvantages: Slower decision-making, potential agency problems, compromise on vision, quarterly focus

For certain industries and certain companies, founder control is superior. For others, professional management is superior. The question is matching the governance model to the business model.

Musk's insight is that certain industries—especially those with long-term innovation horizons and capital-intensive development—might actually benefit from founder control. The industries Musk operates in (aerospace, energy, AI, automotive) are all domains where long-term vision matters more than short-term returns.

If you're running a SaaS company with annual contracts and predictable revenue, professional management is probably better. If you're developing something that takes a decade to mature but creates enormous value, founder control might be better.

The Regulatory Endgame: How Governments Might Respond

Eventually, governments will respond to Musk's consolidation. The question is how.

Option 1: Accept it and regulate lightly. If the companies remain ethical and don't abuse their consolidated power, governments might just monitor them and step in if problems emerge.

Option 2: Require structural separation. Governments could mandate that aerospace, AI, and communication infrastructure operate independently so no single person controls all three.

Option 3: Impose governance requirements. Governments could require that consolidated companies have independent boards overseeing cross-company transactions to prevent abuse of power.

Option 4: Antitrust action. If the consolidation creates monopolistic power, governments could force breakup.

Most likely is some combination of options 1 and 3. Governments will probably tolerate consolidation as long as they can impose governance oversight to prevent abuse.

Musk's strategy is probably to move fast, make the consolidation valuable and functional, and then make breaking it apart politically difficult.

The Productivity Angle: Tools for Modern Innovation Teams

As we consider how modern companies operate at high velocity, it's worth noting that the tools you use to manage teams and communication matter. Runable offers AI-powered automation for teams looking to streamline documentation, presentations, and reports at scale. When you're consolidating companies and moving at high velocity, having tools that generate presentations, documents, and reports automatically can actually save significant coordination overhead.

For teams working across multiple companies or managing rapid iteration cycles, platforms like Runable handle the routine documentation and reporting work that would normally require lengthy meetings and coordination. At $9/month, it's a practical solution for reducing the friction that consolidation is trying to eliminate in the first place.

Use Case: Consolidating company presentations and quarterly reports from multiple entities into unified dashboards and reports in minutes instead of hours.

Try Runable For Free

The Personality Factor: Can Only Musk Pull This Off?

Let's be honest: a lot of this works because of Musk specifically. His track record. His confidence. His willingness to make irrational bets that happen to work out. His ability to inspire talent. His ability to attract capital when he needs it.

Musk has built an enormous reputation for delivering on seemingly impossible things. That reputation is why investors believe in SpaceX, why engineers want to work at Tesla, why people use Starlink even when it's not the easiest option.

Take away Musk's personality and track record, and the consolidation model doesn't look as compelling. It looks like a power grab by someone unproven.

That's actually a feature of founder-controlled companies. They depend heavily on founder credibility. Which is great while the founder has credibility and terrible if that credibility evaporates.

Other founders could theoretically replicate Musk's approach. But they can't replicate the 20 years of proven success that gives Musk the credibility to pull off something this audacious.

So even if other founders understand the model intellectually, executing it requires either waiting to build similar credibility or having a different approach that works without prior success.

This is why the Musk model probably doesn't get widely copied. It's not just structural. It's personal.

Thinking About the Next Decade

Over the next decade, we'll likely see:

- SpaceX-xAI integration proving whether the consolidation actually creates measurable advantages

- Regulatory pressure on Musk's consolidated structure

- Other founders attempting some form of consolidation, with mixed results

- Traditional companies experimenting with more founder-like decision-making structures

- A broader discussion about governance models and where founder control actually works

What won't happen is a wholesale shift toward founder-controlled conglomerates. That's incompatible with the way venture capital works, the way public markets operate, and the regulatory environment.

But what might happen is greater recognition that founder control, in the right context with the right person, creates real advantages. That might shift how we think about company structure, founder exit timelines, and the role of boards.

Musk's consolidation is basically a bet that he can maintain control while remaining effective, and that the consolidation creates genuine value. If he's right, it becomes a case study in how to structure companies for long-term innovation. If he's wrong, it becomes a cautionary tale about concentrated power.

We're probably in the middle of finding out which one it is.

FAQ

What does founder control actually mean for company decision-making?

Founder control means that one person—the founder—has the authority to make major decisions about strategy, capital allocation, and direction without needing to get approval from boards, shareholders, or other stakeholders. In Musk's case with SpaceX-xAI consolidation, it means he can move resources between companies, set strategic direction, and make billion-dollar bets on his own judgment. This eliminates the friction that comes with governance committees and shareholder approval processes, allowing decisions to be made in days instead of months. The trade-off is that there's no institutional check on bad decisions if the founder's judgment is wrong.

How does the SpaceX-xAI merger create operational synergies?

The merger creates synergies through shared infrastructure, talent, and strategic vision. SpaceX's satellite network (Starlink) and launch capacity can support AI infrastructure needs. xAI's AI breakthroughs can improve optimization algorithms used in rocket guidance and manufacturing. By consolidating these companies, the same leadership can make unilateral decisions about allocating SpaceX's profitable cash flows into xAI's infrastructure needs, which might not be possible if they were separately governed. The companies also share research, talent, and can move resources between projects based on current priorities rather than being constrained by separate budgets and boards.

Why is velocity of innovation important for founder-controlled companies?

Musk's thesis is that in rapidly evolving industries like AI and aerospace, the company that iterates fastest wins. Traditional governance structures introduce friction: board meetings, shareholder approvals, budget cycles. Founder control eliminates most of that friction. If you can make decisions three weeks faster than your competitor on every major decision, and you make twenty major decisions per year, that's forty weeks of advantage. For AI specifically, where models improve through iteration and experimentation, that speed advantage in running experiments and adjusting strategies can translate into real competitive benefits.

Could other founders replicate Musk's consolidation model?

Some could, but most won't. It requires three things: personal wealth sufficient to own the companies being consolidated or fund their growth, a proven track record that gives you credibility with investors and talent, and genuine operational synergies between the companies. Musk has all three. Most other founders have at most one or two. Additionally, if you've taken on external investors or gone public, you need board and shareholder approval to consolidate, which introduces the governance friction that founder control is designed to avoid. So while the model is theoretically replicable, the practical obstacles are high.

What regulatory risks does founder-controlled consolidation face?

The biggest risk is that governments decide the concentration of power is a political problem and require structural separation or impose governance requirements. If Musk controls aerospace (SpaceX), communication infrastructure (Starlink), AI (xAI), and energy (Tesla), that's a significant concentration of power over critical infrastructure. Governments are likely to impose some form of oversight eventually—either requiring independent boards for consolidated companies, mandating separation between certain business units, or in extreme cases, forcing breakup under antitrust law. The regulatory risk is probably the binding constraint on how far founder consolidation can actually go.

How does founder control affect talent recruitment and retention?

Founder control attracts certain types of talent—mission-driven engineers and scientists willing to work with a visionary on problems they find meaningful. It repels other types of talent—those who want career stability, clear advancement paths, and corporate structure. Musk's companies tend to have very high-performance pockets but also high churn in mid-level positions. The best people are attracted by working directly with the founder on important problems. The trade-off is that people also burn out more easily in a founder-driven culture without institutional structure to support career development.

What happens to founder-controlled companies when the founder steps back?

Historically, they struggle. Founder-controlled companies are optimized for that specific founder's judgment. When the founder leaves—through retirement, death, or stepping back—the institutional advantage evaporates. There's usually no succession plan because the founder made all major decisions. Traditional companies solve this through boards that develop leadership pipelines and institutional processes that work regardless of who's in charge. Founder-controlled companies that survive long-term usually have to rebuild these structures, which means losing some of the speed and vision advantages they had under founder control.

Is consolidation economically more efficient than having separate companies?

There are modest efficiencies from shared services and infrastructure, probably 5-10% cost reduction in admin and IT functions. But the real advantage isn't economic efficiency in the traditional sense. It's strategic flexibility—being able to allocate capital across companies based on a long-term vision rather than each company's individual ROI, and being able to make unified decisions about technology development and resource allocation. For companies in capital-intensive industries with long development timelines, that strategic flexibility might be worth more than short-term economic efficiency.

How does regulatory pressure limit founder power?

While founders can consolidate companies internally relatively freely, their power is constrained by government regulation. SpaceX depends on FAA approval for launches and FCC licensing for Starlink. xAI is subject to potential AI regulation. Tesla must comply with automotive safety rules. If any of these regulators decide that the consolidated structure is problematic, they have tools to impose requirements or restrictions. Governments can require structural separation, impose governance oversight, deny new licenses, or pursue antitrust enforcement. The regulatory constraint is actually more powerful than any internal governance constraint because it's backed by government authority.

Conclusion: The Future of Founder Power and Corporate Consolidation

Musk's consolidation of SpaceX and xAI represents something genuinely new in Silicon Valley: the emergence of founder-controlled conglomerates optimized for long-term innovation rather than quarterly returns. This isn't just a business deal. It's a structural statement about how the best way to build breakthrough technologies might be through founder control, unified vision, and elimination of governance friction.

The advantages are real: speed, vision alignment, long-term focus, unified resource allocation, and rapid decision-making. The disadvantages are equally real: succession risk, limited external perspective, lack of institutional checks, and vulnerability to founder error.

What's remarkable about this moment is that the question isn't whether founder control is possible. It's whether it's preferable for certain businesses in certain moments. And the honest answer is probably yes—for capital-intensive innovation in rapidly evolving fields, founder control does create advantages.

But this doesn't mean we're about to see a flood of founder-controlled conglomerates in Silicon Valley. Most founders don't have the wealth, credibility, or control to replicate Musk's approach. Most have taken on external capital that comes with governance strings attached. And even if they could replicate it, the regulatory environment probably won't allow massive consolidation of power without pushing back.

So what we're likely looking at is a case study. A famous, high-profile example that changes how some founders think about company structure and control. But not a wholesale shift in how Silicon Valley builds companies.

The real insight from Musk's consolidation is that the traditional corporate governance model isn't necessarily optimal for all businesses at all stages. For certain domains and certain people, founder control actually might create better innovation, faster progress, and more ambitious long-term thinking.

That doesn't mean governance structures should be abandoned everywhere. It means they should be matched to the business and the person running it. For some situations, formal boards and independent oversight are essential. For others, founder control might actually be the better path.

The next decade will tell us whether Musk's consolidation actually creates sustainable advantage or whether it becomes a warning about concentrated power. Either way, it's changed how we think about founder authority and corporate structure.

What's certain is that founder power, as a concept, has become a central question in how we build companies that drive significant innovation. And Musk's consolidation is forcing that conversation earlier and more directly than it might have emerged otherwise.

Key Takeaways

- Musk's SpaceX-xAI consolidation eliminates governance friction, enabling decisions in days instead of months—a critical advantage in fast-moving industries

- Founder control works best for capital-intensive innovation with long development timelines, not for all business models

- The real constraint on founder power isn't boards or shareholders—it's government regulation of critical infrastructure

- Speed advantages from consolidated decision-making compound: 2-3 weeks faster on each major decision translates to significant competitive edge across 20+ annual decisions

- Most other founders cannot practically replicate Musk's model due to external capital commitments, lack of proven track record, or missing operational synergies

- Succession risk remains unsolved: founder-controlled companies face institutional challenges when founders retire or step back

- Traditional boards and governance exist for good reasons, but they impose costs that may outweigh benefits for certain industries at certain stages

Related Articles

- SpaceX and xAI Merger: Inside Musk's $1.25 Trillion Data Center Gamble [2025]

- Tech Elites in the Epstein Files: What the Documents Reveal [2025]

- Why Loyalty Is Dead in Silicon Valley's AI Wars [2025]

- The ARR Myth: Why Founders Need to Stop Chasing Unrealistic Growth Numbers [2025]

- Grok AI Data Privacy Scandal: What Regulators Found [2025]

- Mundi Ventures' €750M Kembara Fund: Europe's Deep Tech Revolution [2025]

![How Elon Musk Is Rewriting Founder Power in 2025 [Strategy]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/how-elon-musk-is-rewriting-founder-power-in-2025-strategy/image-1-1770404846368.jpg)