The ARR Myth: Why Founders Need to Stop Chasing Unrealistic Growth Numbers

Introduction: The Dangerous Game of ARR Theater

Somewhere in San Francisco, a founder just tweeted that their AI startup hit $100 million in annual recurring revenue. No product launch was mentioned. No customer press release. Just a graph and a celebration emoji.

Your stomach drops. You're only at $3 million. How are they growing 30 times faster?

Here's what you're not seeing: that $100 million figure isn't what you think it is. It might not even be real revenue in the accounting sense. And if it is, it probably comes with a mountain of problems that don't fit in a tweet.

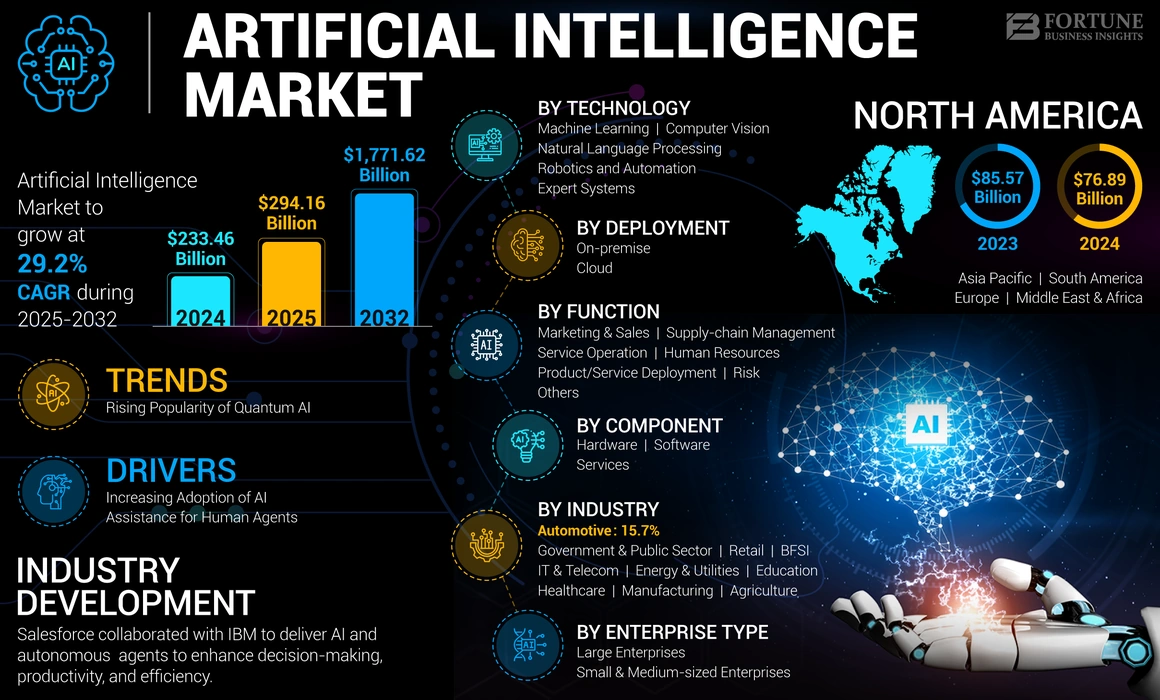

This is the ARR mania problem facing founders in 2025. The AI boom has created a bizarre new culture where growth metrics are currency, and founders are competing in a game where the scoreboard doesn't actually measure winning.

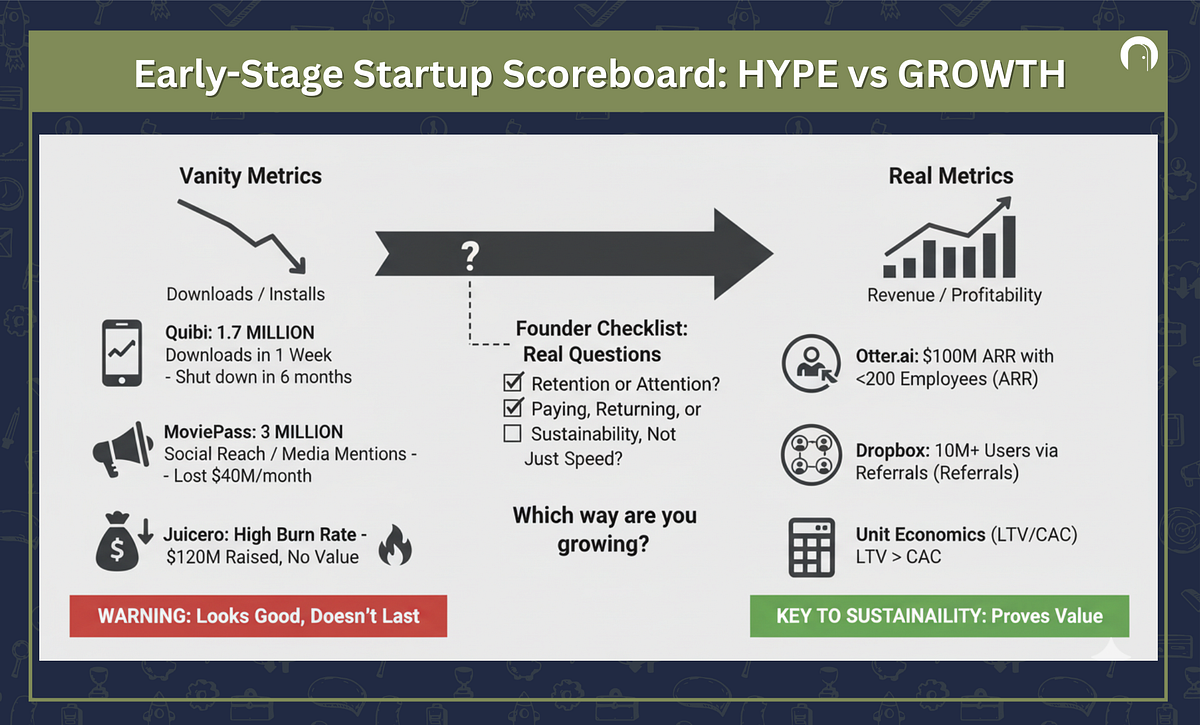

The reality is this: the venture capital world has become obsessed with annual recurring revenue (ARR) numbers as the primary barometer of startup success. VCs want to see founders hitting impossible milestones before Series A funding. The pressure is real. The competition feels existential. And yet, the metrics being used to measure success are fundamentally broken.

This isn't just a semantic debate about accounting terminology. When founders chase ARR theater instead of building durable businesses, they make decisions that undermine long-term value creation. They hire too fast. They overpromise to customers. They build on shaky foundations. And when the hype cycle inevitably cools, they crash harder than the startups that built sustainably from day one.

The good news? There's a way out of this trap. Once you understand what the numbers actually mean, you can stop playing a game you can't win and start building something that lasts.

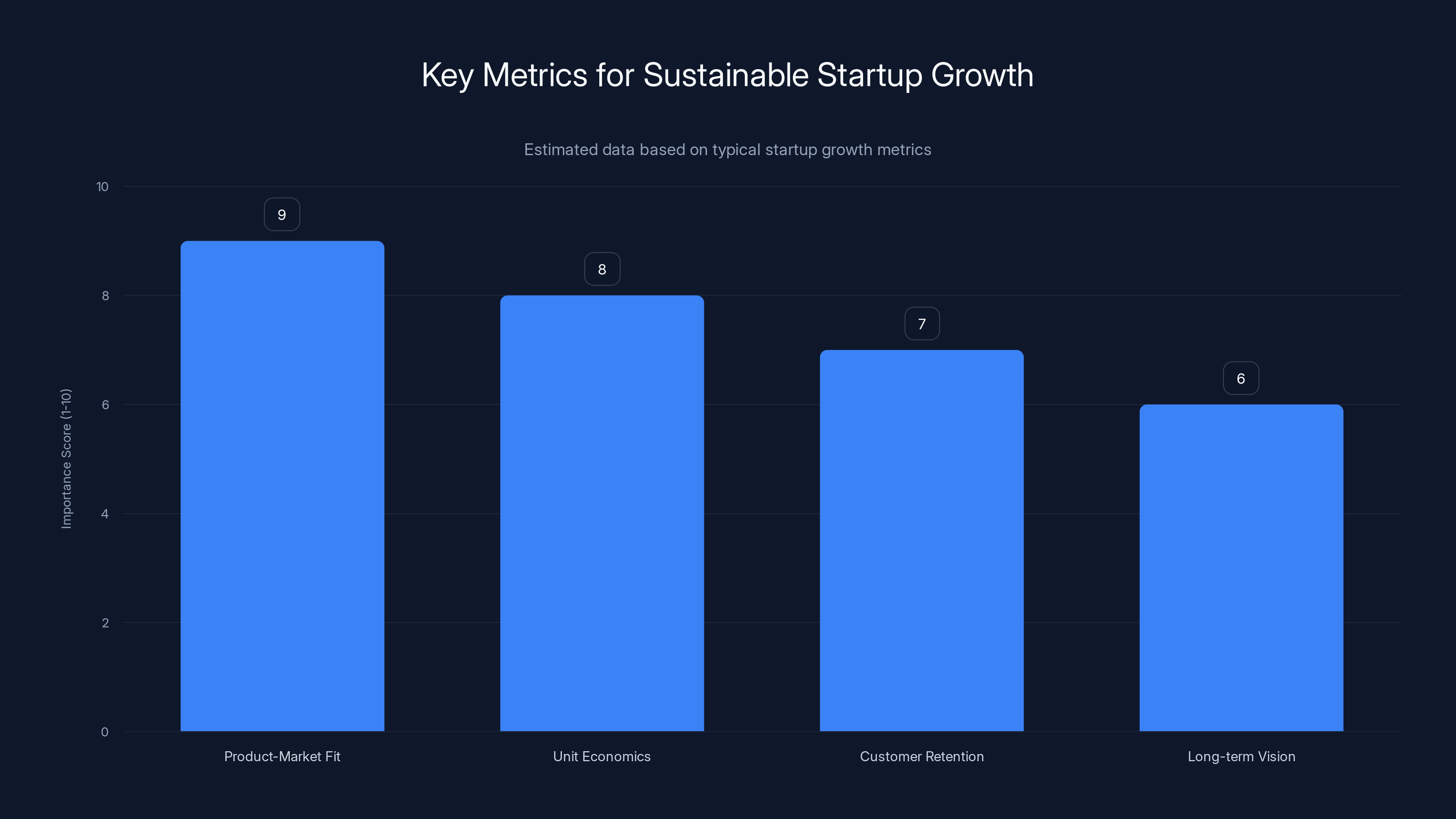

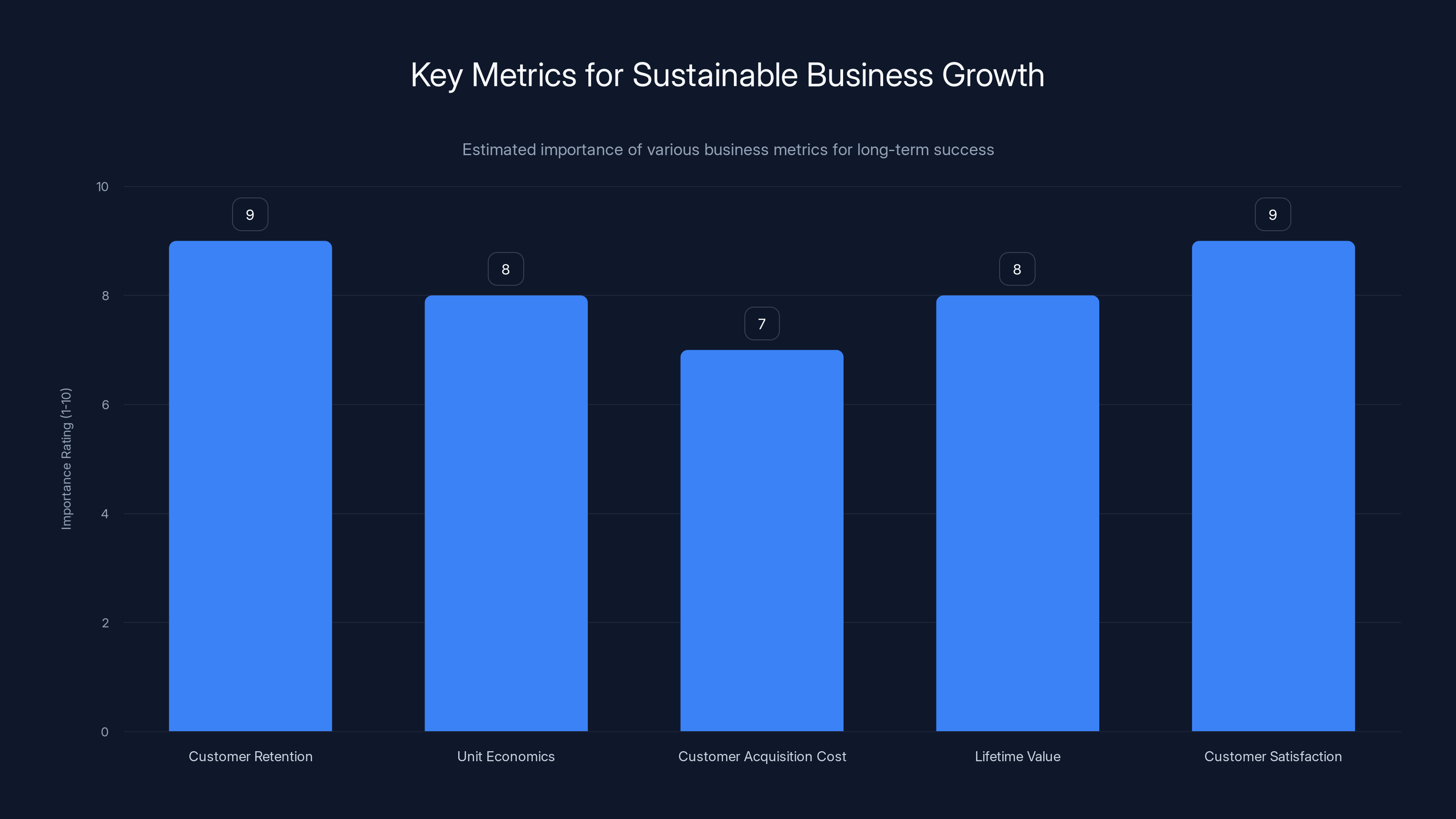

Product-market fit is the most critical factor for sustainable growth, followed by strong unit economics and customer retention. Estimated data reflects typical priorities.

Understanding ARR vs. Revenue Run Rate

Let's start with the definitions, because this is where most of the confusion actually lives.

Annual recurring revenue (ARR) is an actual accounting term with real meaning. It represents the annualized value of contracted, recurring subscription revenue. Think about a customer who signs a $10,000 per year contract. That's ARR. It's predictable. It's guaranteed (at least until they churn). It's the foundation of what makes a SaaS business different from a consulting firm.

Revenue run rate is something else entirely. It's what happens when you look at the money you made last month, or last quarter, and just multiply it to project what a full year would look like. Made

Here's the critical difference: ARR is contractual and durable. Run rate is a snapshot extrapolated into fantasy.

But on Twitter? These numbers get conflated constantly. A founder sees one really good month and announces they're at "

The problem is that most people reading the tweet don't know the difference. They see $100 million and assume the company has found product-market fit and signed a bunch of long-term customers. What they don't see is that maybe the number includes pilot programs that expire in 90 days, or a single enterprise customer going through an unusually strong quarter.

The dirty truth that gets buried in venture capitalist discussions is that not all $1 of ARR is the same. A dollar of ARR from a Fortune 500 company with a 3-year contract is worth infinitely more than a dollar of ARR from a startup doing a 3-month pilot. One will probably still be paying you in year two. The other probably won't.

Yet the scoreboard treats them identically. That's the trap.

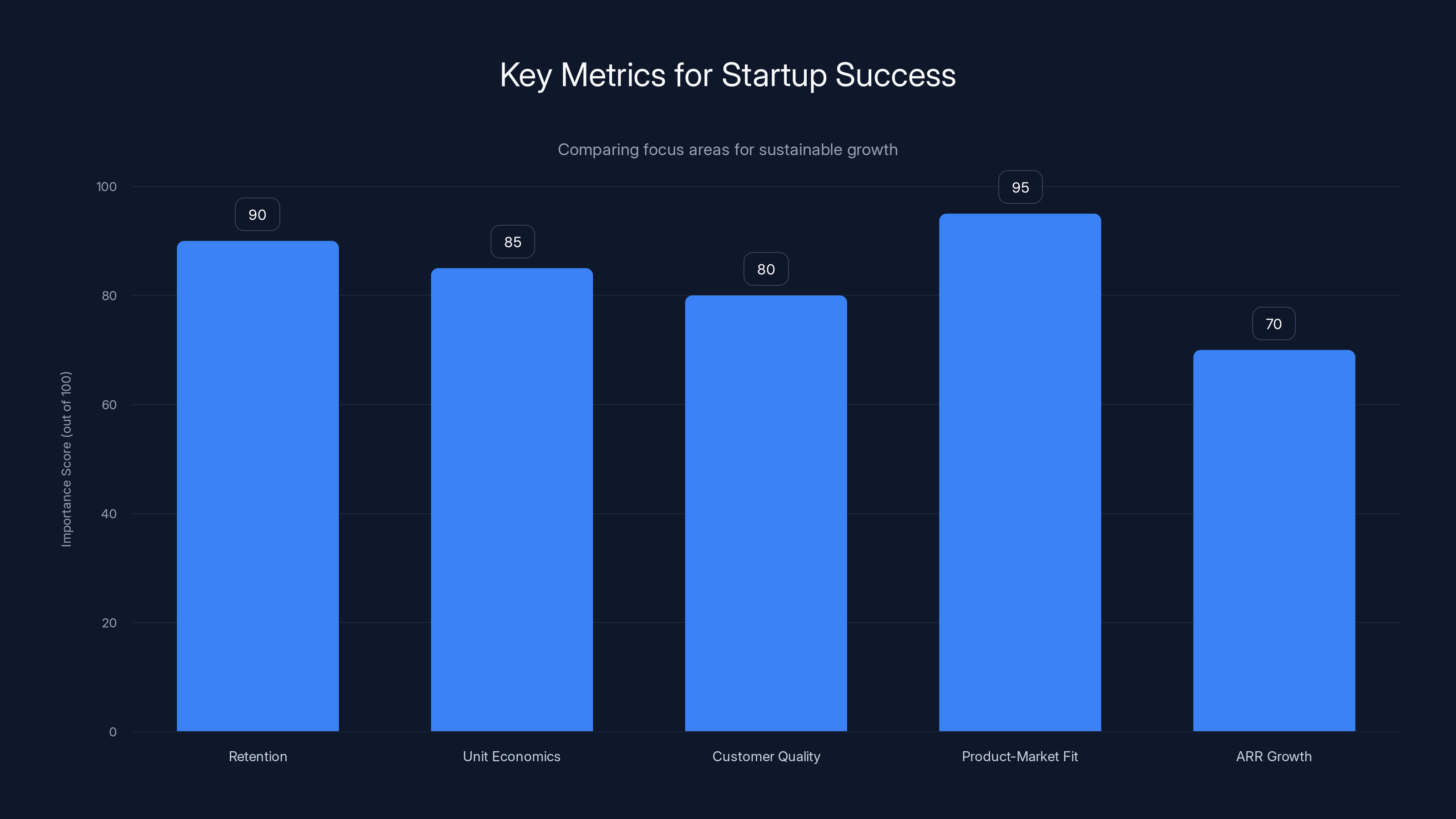

While ARR growth is often emphasized, retention, unit economics, customer quality, and product-market fit are more critical for long-term success. Estimated data.

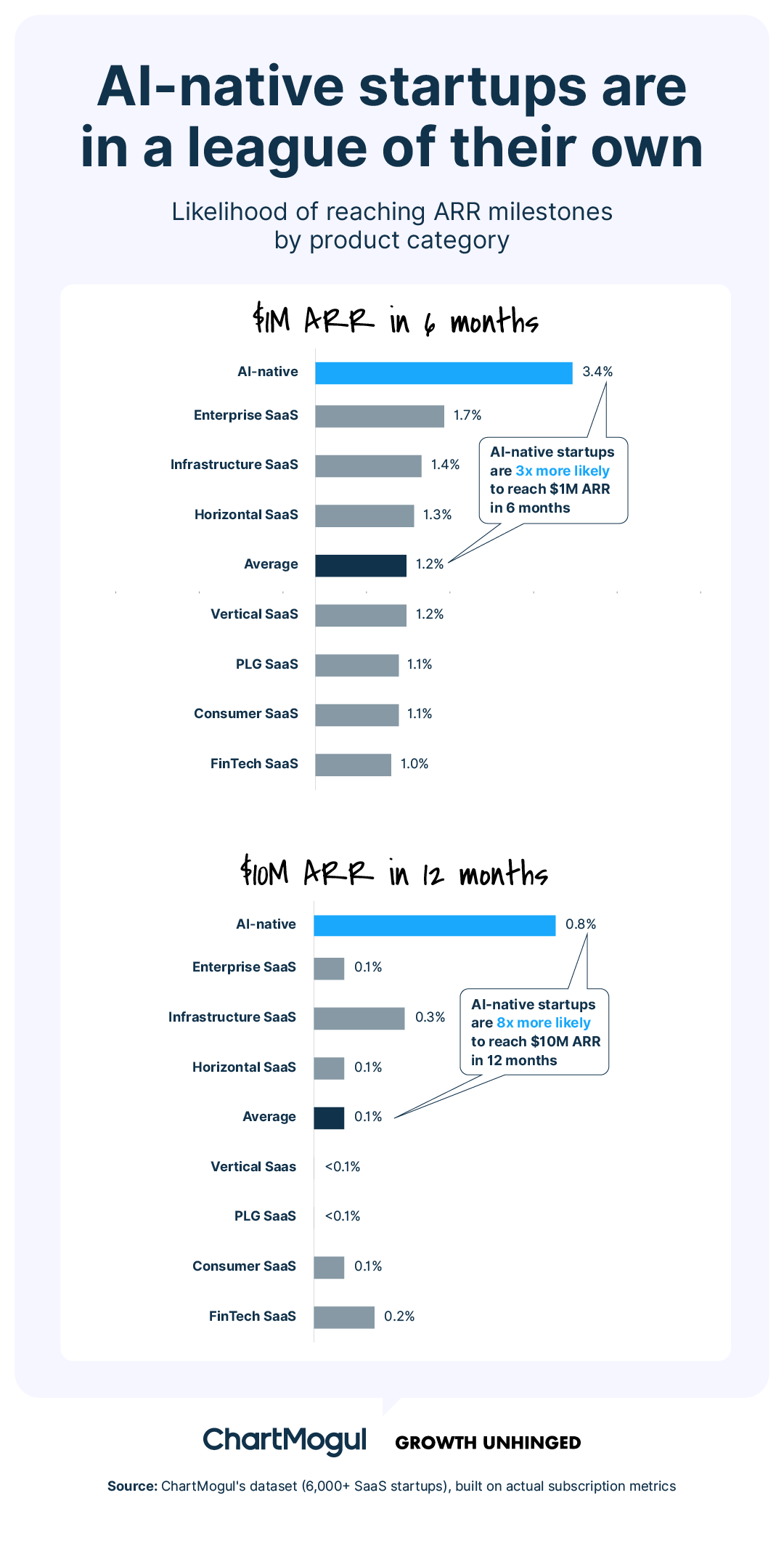

The AI Startup Anomaly: Unprecedented Growth and Its Origins

There's something genuinely weird happening with AI startups right now that hasn't really existed in previous tech cycles.

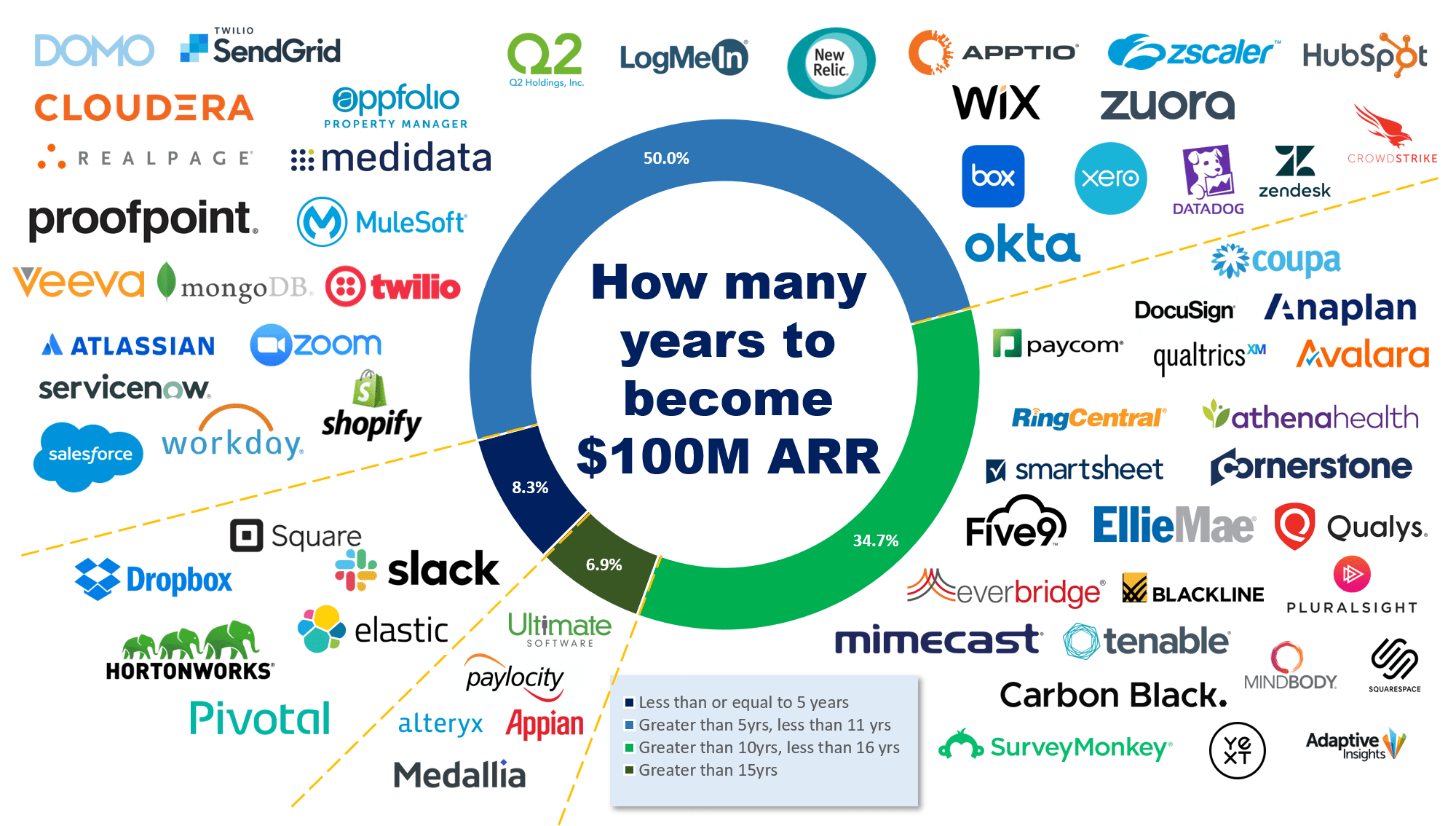

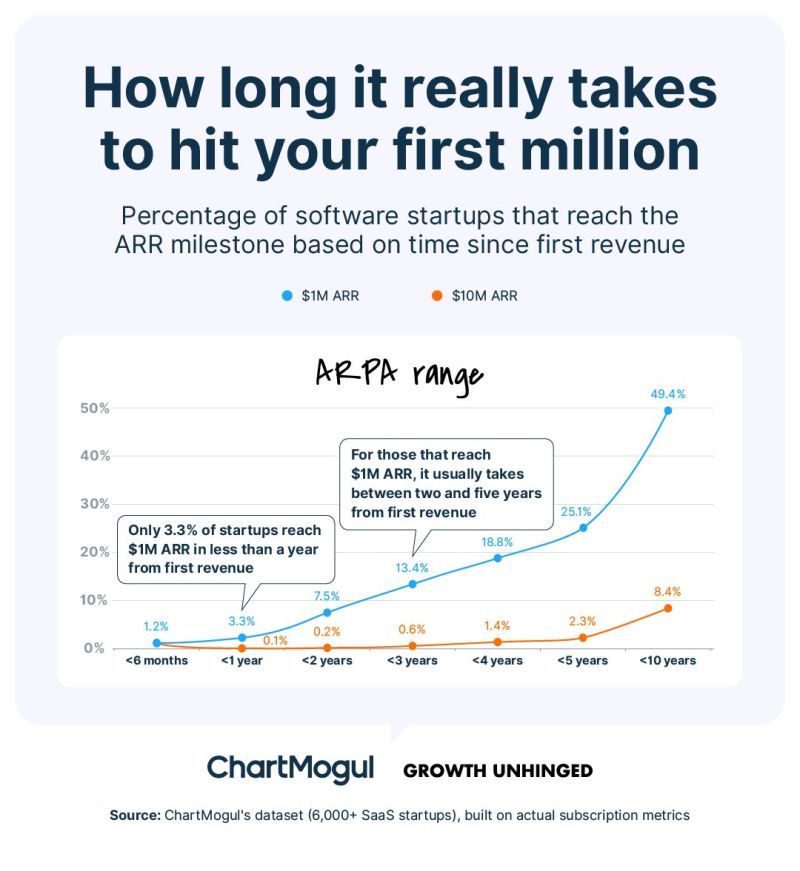

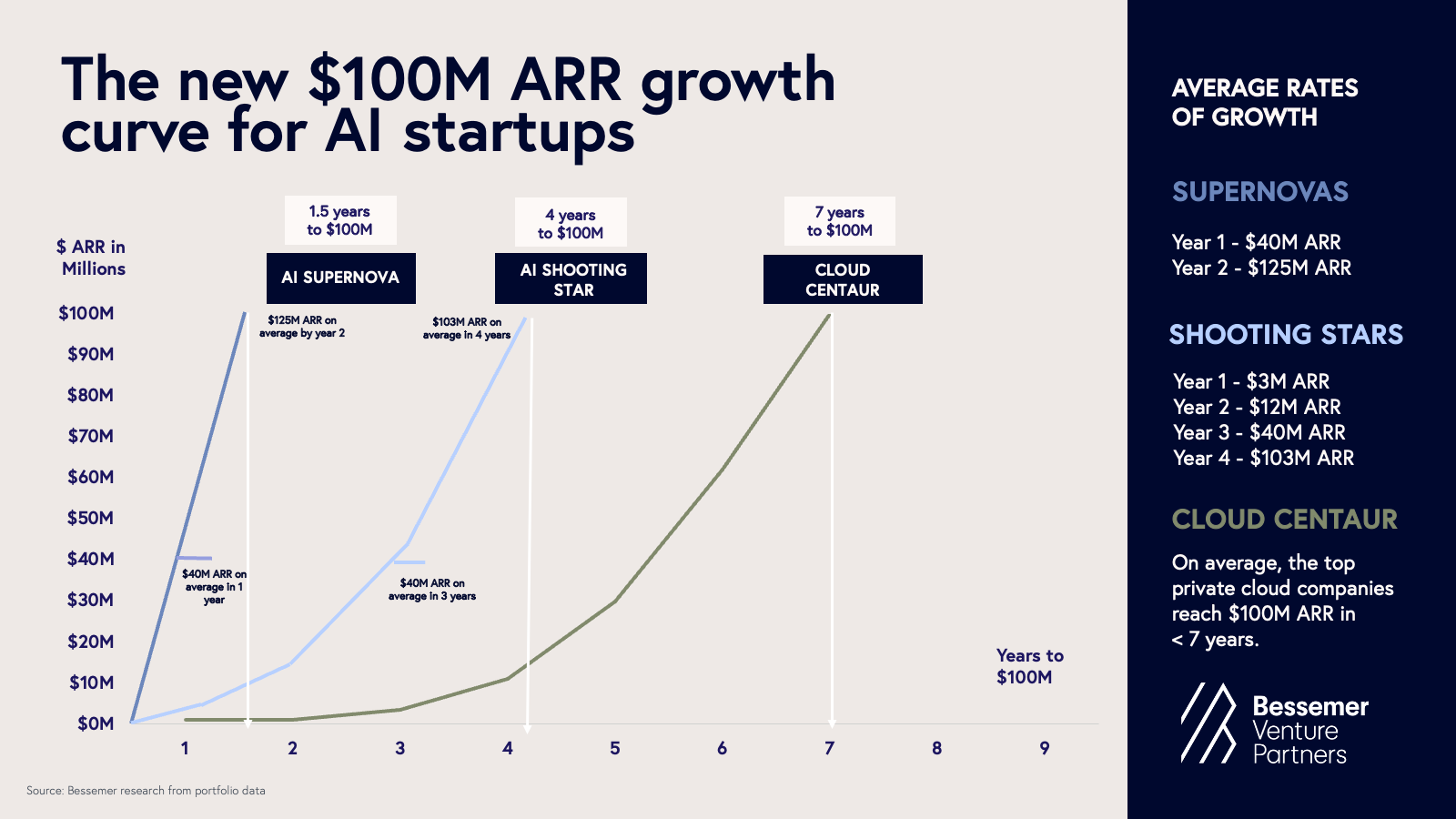

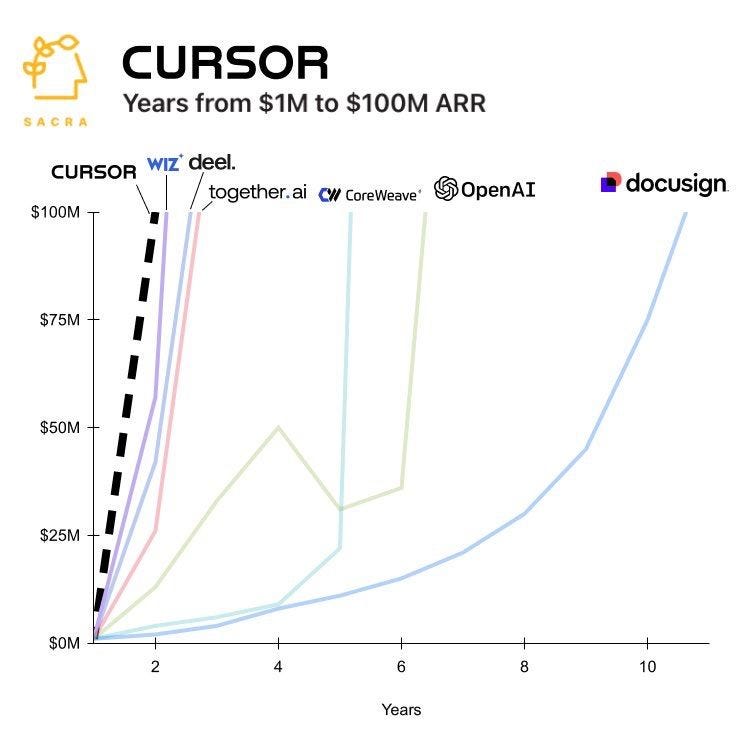

We're watching companies go from zero to

Why?

Part of it is legitimate product magic. When you build something that saves people 10 hours per week or makes their work 10 times better, adoption can be genuinely explosive. The underlying demand was always there. There were always people willing to pay for better tools. AI just made better tools possible for the first time.

But that's only part of the story.

The venture capital industry has also fundamentally changed how it allocates capital. In previous cycles, a founder might raise

Now? A founder raising Series B is raising

When capital constraints disappear, growth metrics change dramatically. You can pay for customer acquisition cost (CAC) that would've been insane in previous eras. You can afford to support customers with white-glove onboarding. You can build features that make the product so good that adoption becomes viral.

There's also an element of genuine network effects that didn't exist in previous eras. When Chat GPT hits 100 million users, everyone talks about it. Developers see that everyone at work is using Cursor. Podcasters use Eleven Labs for voice cloning. The social proof and market awareness compounds at light speed. Distribution becomes almost free.

But here's the thing: just because growth is possible doesn't mean it's sustainable. And just because you can grow fast doesn't mean you should. The companies that are hitting these numbers and maintaining profitability and retention are doing something different from the ones that hit these numbers and then crashed.

The Retention Problem: Why Growth Means Nothing Without It

Let's talk about the metric that literally nobody tweets about but is infinitely more important than ARR.

Retention.

You can grow to $100 million in revenue run rate through pilot programs, free trials converted to paid, and overly aggressive sales tactics. You can hit that number in a Twitter-worthy dashboard. But if 70% of your customers churn by month 6, you're not building a company. You're building a hole that you're pouring money into faster than you can fill it.

Here's a real example: imagine a startup lands 100 enterprise customers doing pilot programs. The ARR looks amazing on day one. $100 million annualized. But pilots don't convert at 90% rates. They convert at 10%, maybe 20% if you're lucky. You just burned through your growth numbers on a metric that has almost no staying power.

Retention is the difference between a startup and a business.

A startup might have 100% month-over-month growth and 50% annual churn. A business has 5% month-over-month growth and 95% annual retention. Which one would you rather own? Which one are investors actually going to back long-term?

Retention also costs nothing to measure. You literally just track how many of your customers are still paying you 12 months later. A 90% annual retention rate means 90% of last year's revenue is still coming in this year. A 50% annual retention rate means you're replacing half your revenue base every single year. The first business is durable. The second is unsustainable.

The reason founders don't tweet about retention is simple: it's not impressive. "We grew 5% month-over-month but maintained 92% retention" doesn't get retweets. It doesn't go viral. It doesn't impress VCs at the cocktail party.

But it's the only metric that actually matters.

The companies hitting $100 million in real ARR while maintaining 90%+ retention are genuinely impressive. They've solved product-market fit. They've built something customers actually want. They've created defensibility through value creation rather than sales aggressiveness.

The companies hitting $100 million in run rate with 60% retention? They're in trouble. They just don't know it yet.

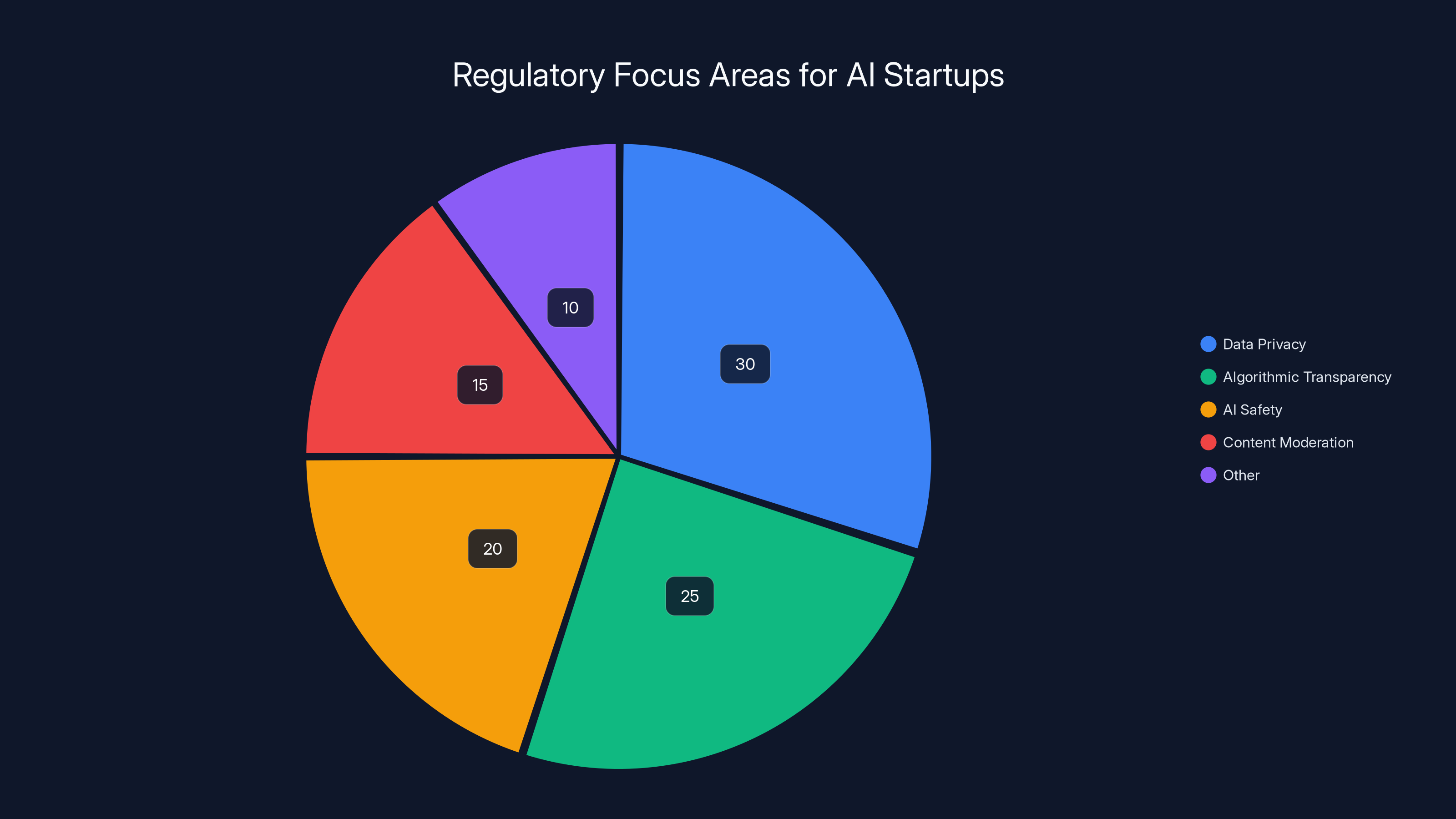

Estimated data shows that data privacy and algorithmic transparency are the primary regulatory concerns for AI startups, accounting for over half of the focus areas.

The Hiring Trap: Growing Fast Means Making Expensive Mistakes

You know what comes right after "we hit $100 million ARR" in the startup playbook?

Mass hiring.

A founder goes from 20 people to 200 people in 18 months. They're trying to capitalize on the growth window. They're trying to build the company before the market changes. They're trying to execute on every opportunity in front of them.

This is also where most of the operational chaos happens.

When you're hiring that fast, you're not hiring carefully. You're hiring people who can handle fast-paced environments and ambiguity. That's a useful skill. But it's not the only skill that matters. You also need people who can build systems, enforce standards, and think long-term.

Fast-growing startups end up with first 100 employees who wear 10 hats each. That works when everyone in the company has already worked at three startups and knows how to improvise. It breaks down when you have people who've only worked at big companies and expect things like documented processes, clear job descriptions, and career ladders.

There's also the recruitment premium. When everyone knows your company is growing at 10x, every salesperson in San Francisco wants to work there. You're competing for talent with companies like Google, Apple, Meta. To win that war, you end up paying a 30%, 40%, sometimes 50% premium to get the same people.

Then there's the onboarding problem. You've hired 50 new engineers in a quarter. There's literally no way to properly onboard 50 engineers in a quarter. So you get some who actually understand your codebase and architecture, and a bunch who are basically just copying code from existing pull requests and hoping it works.

Cursor dealt with this explicitly. The company became so large so fast that it had to intentionally slow down hiring and focus on consolidating the team. That's a luxury problem, but it's still a problem.

The math here is brutal. If you're spending

And that's before you account for the slower velocity, the technical debt they accumulated, and the projects that need to be redone after they leave.

Fast growth without operational excellence doesn't create value. It destroys it.

The Pricing Risk: When Growth Comes from Getting Pricing Wrong

Here's a scenario that happens more often than anyone admits: a startup launches with aggressive free tier or incredibly cheap pricing. Growth is explosive. ARR numbers look amazing. Everyone's excited.

Then they try to raise prices and everything falls apart.

Cursor experienced this explicitly. The company offered incredibly cheap access to its product, which drove adoption through the roof. But when they tried to raise prices, customers rebelled. The company had trained the market that Cursor was a

What looked like

The problem is that pricing directly impacts the quality of your growth. When you have unlimited capital and you're chasing growth, you can sustain unprofitable unit economics for a long time. A customer might be costing you

But again, nobody tweets about unit economics. Nobody builds a narrative around finding the right price point. The story is all about growth, growth, growth.

The companies that are actually building durable value are usually growing a bit slower because they're obsessive about pricing. They're testing different customer segments. They're analyzing which customers are most profitable. They're thinking about how to build a business that can sustain itself on the revenue it generates, not just on the venture capital it's burning through.

The sustainable approach is unsexy. It's methodical. It involves actually talking to customers and understanding what they'd pay. It involves saying "no" to revenue that would destroy your business model. It involves accepting slower growth in exchange for stronger fundamentals.

That's not the game being played right now.

Focusing on customer retention and satisfaction, along with strong unit economics, is crucial for long-term business viability. Estimated data.

Compliance and Risk: The Silent Killer of Hypergrowth

When you're growing at 10x per year, you're probably not paying much attention to compliance.

You've got maybe one person handling legal and compliance matters. They're probably junior. They're probably overwhelmed. And the CEO definitely doesn't want to hear about all the regulatory issues lurking in the product.

This is where things get dangerous.

If you're building an AI product, there are suddenly 15 different regulatory regimes that might apply to your business. Different countries have different rules about data privacy, algorithmic transparency, AI safety, content moderation. The United States is implementing rules through individual states. Europe has the AI Act. China has its own framework. And so on.

Some of these rules don't fully exist yet, which means nobody knows exactly how they'll be enforced. But that doesn't mean they don't apply. It means you're operating in legal gray area, hoping that nobody important notices before you're big enough to hire a 20-person legal team to figure it out.

Some startups get away with this. Some don't.

Eleven Labs, for example, is doing voice cloning, which touches on rights issues, likeness issues, consent issues, and synthetic media regulation. The regulatory landscape is genuinely unclear. But the company is betting that the regulatory environment will clarify in their favor, or that by the time enforcement happens, they'll be big enough and profitable enough to deal with it.

Maybe that works out. Maybe it doesn't.

The point is that when you're optimizing for ARR growth above all else, legal and compliance risks are easy to deprioritize. You tell yourself you'll deal with them later. And sometimes you do. And sometimes you end up spending millions defending lawsuits, paying regulatory fines, or having features forced offline before you've built the business you intended.

This isn't just an AI thing. Data privacy regulations have caught many fast-growing startups off guard. Bank regulations have derailed fintech companies. Tax regulations have caught marketplace companies when they suddenly realized they owed sales tax in 50 states.

The founders who are actually thinking long-term are setting aside 10-15% of their early capital for legal and compliance work. They're hiring experienced heads of legal who can identify risks before they become crises. They're talking to lawyers about the regulatory landscape even when they can't afford much legal help.

Is it an inefficient use of growth capital? Absolutely. Does it slow down your ARR trajectory? Sometimes. Will it save you from existential issues? Probably.

The Customer Quality Question: Are These Real Customers or CAC Experiments?

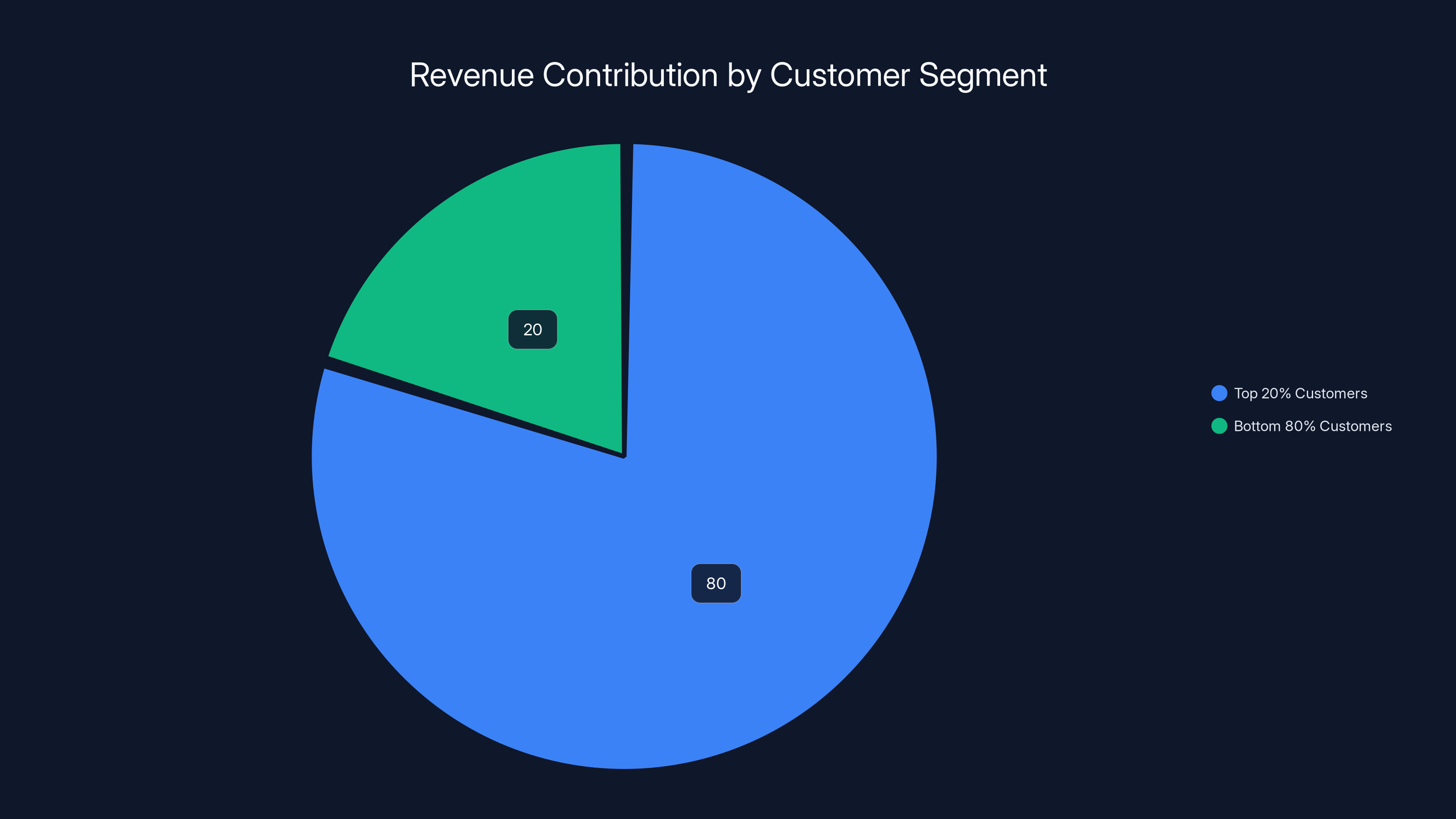

Here's a metric that matters way more than ARR but almost never gets discussed: customer acquisition cost relative to lifetime value.

CAC is what it costs to acquire a customer. LTV is what you make from that customer over their lifetime. The basic math is that if your LTV is 3x or higher than your CAC, your unit economics work. If it's lower than that, you're burning money.

But in the hypergrowth era, founders are often willing to spend absolutely insane amounts on CAC in order to boost ARR numbers in the short term.

Let's say you spend

But what if they only stick around for 1 year? The LTV is $100,000. That's a 2x return. Still positive, but thin. And what if they stick around for 1 year and then churn? You're now at 1x and you need them to stay for 2 years just to break even.

The problem is you don't know which customers will stick around until they actually stick around. So you take a bet. And when you're optimizing for ARR, you take a lot of bets on customers you're not sure about.

Some of these customers work out. Some don't. But in the ARR calculation, they all count the same way.

Eleven Labs offers free credits to creators, which drives adoption and buzz and makes the product look incredibly successful from an ARR perspective. But how much of that "ARR" converts to actual paid customers? How many of those creators end up paying? These are the questions that never get asked because they don't help the narrative.

The companies that are actually building sustainable value are obsessive about customer quality. They track which cohorts of customers have the best retention. They understand what types of customers are most profitable. They're willing to pass on revenue that comes from customer segments that look good for 6 months but churn after a year.

This sounds obvious when you write it out, but it's genuinely hard to do when you're raising capital on the basis of ARR numbers. VCs don't want to hear "we're passing on some revenue to maintain cohort quality." They want to hear "we're at $50 million ARR and we're not slowing down."

Estimated data shows that the top 20% of customers typically generate over 80% of revenue for SaaS companies, highlighting the importance of focusing on profitable customer segments.

The Psychological Cost: Anxiety and the Crushing Burden of Unrealistic Expectations

Jennifer Li from Andreessen Horowitz identified something that matters more than all the financial metrics combined: the psychological toll that ARR mania is taking on founders.

You're building a company. You're making real progress. Your product is getting better. Your customers are happy. But every day you're seeing founders on Twitter announce they hit

You start asking yourself: Am I moving too slow? Should I be more aggressive? Should I be doing whatever the successful founders are doing?

The anxiety is real. And it's not productive.

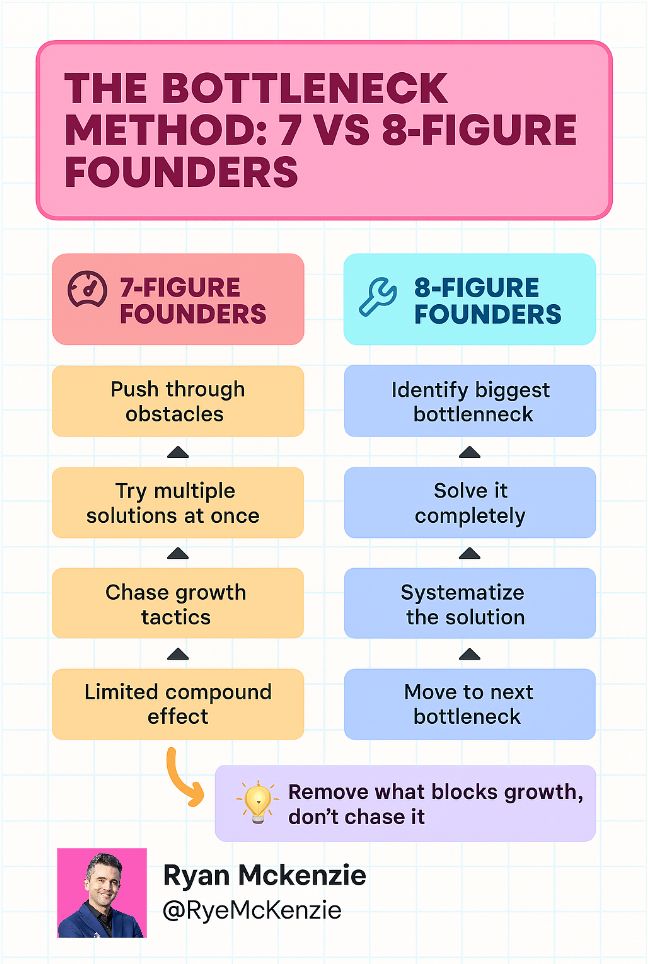

Here's what typically happens: a founder internalizes this pressure and makes bad decisions in order to chase the narrative. They hire too fast. They make promises they can't keep. They build features nobody asked for. They chase customer segments they don't understand. All in the name of hitting a number that feels like proof that they're succeeding.

Then, 18 months later, they realize that the company they built doesn't work. The culture is broken because they hired too fast. The product is brittle because they built features without understanding why customers needed them. The customers are unhappy because they've been over-promised to.

All of this could've been avoided by ignoring the Twitter comparison game and just focusing on building something good.

The founders who are actually winning are the ones who've somehow managed to block out the noise and just focus on the fundamentals. They're building products people love. They're hiring slowly and carefully. They're maintaining sustainable unit economics. They're not checking Twitter every morning to see who just announced a record ARR number.

But that's genuinely hard when the entire venture capital industry is telling you that growth is the only metric that matters.

What Sustainable Growth Actually Looks Like

Let's talk about what genuinely successful startups are optimizing for instead of just chasing ARR.

Product-Market Fit Above Everything Else

This sounds obvious, but it's genuinely not how most founders think about it. If you have product-market fit, growth becomes easier. Customers come to you. Retention is high. Unit economics work. You don't have to force growth with expensive sales and marketing.

The problem is that product-market fit isn't a number you can tweet. You can't quantify it. You can't put it on a slide deck. But you can feel it. Your customers are excited. They're telling other people about your product. They're willing to pay more for it. They're not leaving.

Founders who are actually thinking long-term are willing to move slower in the early days to make sure they have this nailed. That means spending time with customers. It means iterating based on feedback. It means sometimes deciding that a customer isn't a good fit and turning them away.

But it results in a foundation that can actually sustain a 10x business. Whereas forcing growth before you have product-market fit just results in a leaky bucket.

Unit Economics That Work

This is the boring metric that nobody cares about but everyone should. Can you make money on the customer at your current pricing?

If your customer acquisition cost is

The sustainable businesses have unit economics that work. They might be spending

But discovering that usually requires saying "no" to some revenue. It requires turning away customers who might boost your ARR but wouldn't be good for your LTV. It requires pricing carefully instead of aggressively.

Retention and Durability

This is the metric that actually tells you whether you're building something durable or just pushing water uphill.

A 95% annual retention rate means your business is getting stronger every year. Your revenue compounds. Your unit economics improve as you reduce the ratio of acquisition cost to lifetime value.

A 50% annual retention rate means you're in a perpetual struggle just to keep your revenue flat. You're spending millions acquiring customers who leave anyway. You're not building anything.

The best founders track retention obsessively. They understand which customer cohorts have the best retention. They know why customers churn. They're constantly iterating to improve the product based on what they learn from customers who leave.

Team Quality Over Team Size

Fast-growing startups tend to optimize for headcount. They want to get big fast because big feels like it means successful.

But the sustainable startups are optimizing for team quality. They're willing to do more work with fewer people if it means having people who are actually great at what they do.

This has become almost unfashionable in the venture capital world, which is obsessed with "speed to market" and "execution velocity." But slow, deliberate hiring tends to result in better products and better cultures than fast, desperate hiring.

The trade-off is obvious: if you hire slowly, you grow more slowly in the short term. Your ARR number in month 6 is going to look worse than the founder who hired 50 people and threw them at the problem.

But in month 30, the quality difference becomes apparent.

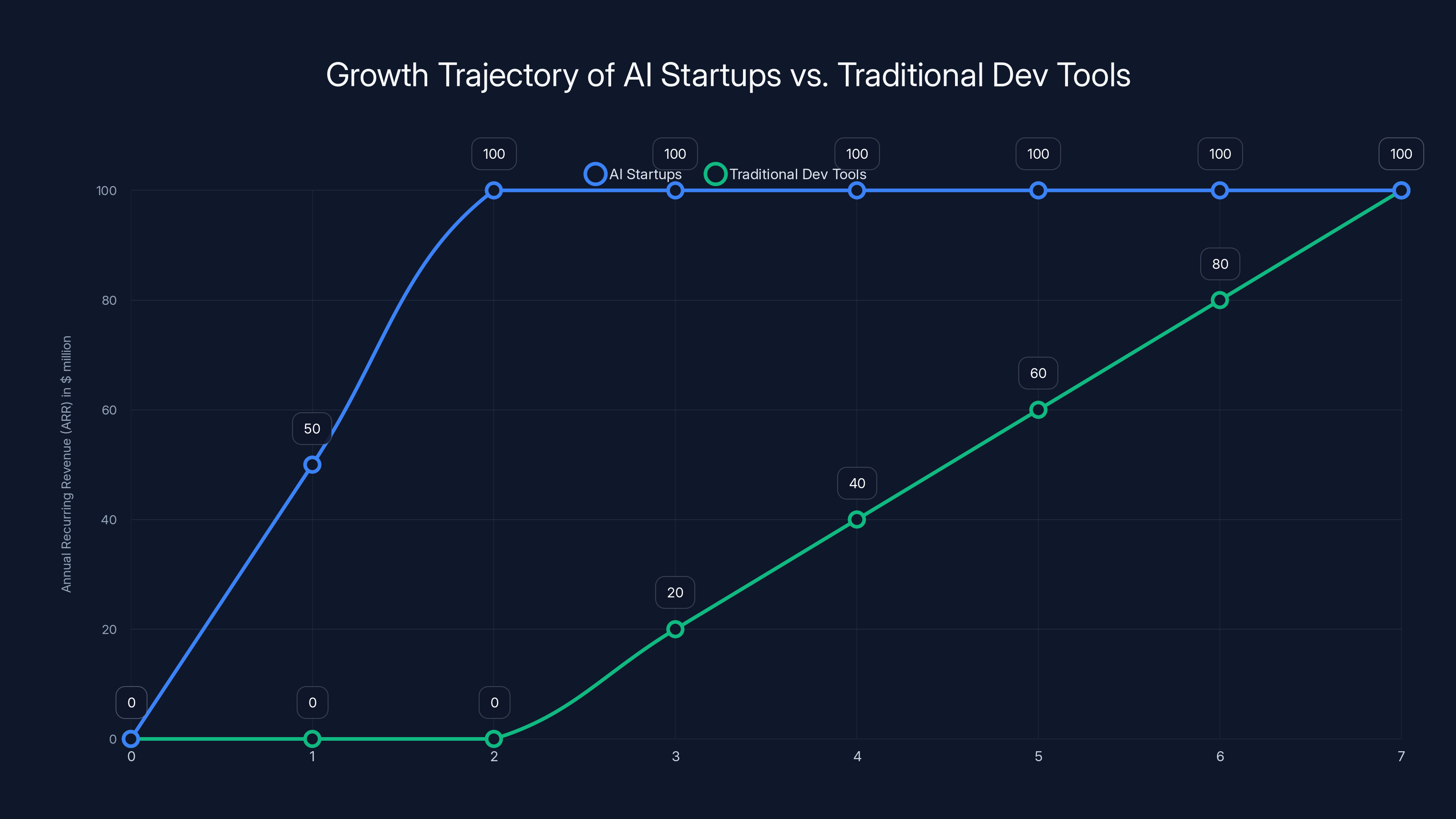

AI startups like Cursor can reach $100 million ARR in just 2 years, compared to 5-7 years for traditional dev tools. Estimated data based on industry trends.

The Venture Capital Problem: How Investor Incentives Fuel the ARR Arms Race

Here's the thing that doesn't get discussed enough: the venture capital industry is fundamentally incentivized to push this behavior.

A VC makes money by finding companies that grow really fast, that can go public at huge valuations, and that will return the fund's capital many times over. The faster the growth, the sooner the exit, the better for the fund's metrics.

When a VC sees a founder hitting $100 million in ARR in two years, that founder suddenly looks like a potential 10x or 100x return. Even if that ARR is mostly run rate and that growth is unsustainable, it doesn't matter from the VC's perspective in that moment. What matters is that the founder is demonstrating the ability to scale.

So VCs have actively encouraged the ARR theater. They've asked founders why they're not growing faster. They've funded competitors to the same company just to accelerate the market. They've created FOMO by showing founders how much capital other founders are raising.

All of this creates pressure on founders to chase metrics that might not actually matter for long-term success.

There are some VCs who are pushing back on this. Jennifer Li from Andreessen Horowitz is one of them. She's explicitly saying that founders should stop obsessing over ARR and start obsessing over business durability. That's refreshing.

But she's also at Andreessen Horowitz, which is one of the largest and most capital-abundant VCs in the world. It's easy to tell founders not to stress about growth when you can write a

The Revenue Audit: How to Separate Real from Theater

If you're evaluating a startup and trying to figure out what the actual business looks like underneath the ARR theater, here are the questions to ask.

What Percentage Is Actual ARR vs. Run Rate?

This is the fundamental question. Push the founder to break down their revenue into contracted ARR (multi-year contracts with clear renewal dates) and revenue run rate (based on short-term or non-contracted arrangements).

If 80% of the number is actual ARR and 20% is run rate, you're looking at a real business. If it's 20% ARR and 80% run rate, you're looking at smoke and mirrors.

What Is Annual Retention?

A founder should be able to tell you this off the top of their head. If they can't, that's a bad sign. If they tell you it's less than 80%, that's a red flag. If they tell you it's 95% or higher, that's genuinely impressive.

How Much of Revenue Comes from a Small Number of Customers?

If 50% of ARR comes from 5 customers, that's not a sustainable business. That's a services business in disguise. Sustainable businesses have reasonably distributed revenue across a larger number of customers.

What Is the Burn Rate and How Long Is the Runway?

A company can grow ARR incredibly fast while burning even more cash. You need to understand the relationship between top-line growth and the actual unit economics of the business.

What Is Unearned Revenue?

Unearned revenue is money customers have already paid you that you haven't earned yet. It's a liability on the balance sheet. A high unearned revenue balance is good for cash flow in the short term, but it tells you that customers have prepaid, which usually means they're confident in the product (or that you convinced them to prepay).

A startup with

The Path Forward: How to Think About Growth Differently

If you're a founder and you've been feeling anxious about your ARR numbers relative to what other founders are tweeting, here's how to reframe the problem.

You're not in a race with other founders. You're in a race with your past self. The question isn't "am I growing as fast as someone else?" The question is "am I building a business that will still exist in five years?"

That's a different optimization problem with a different answer.

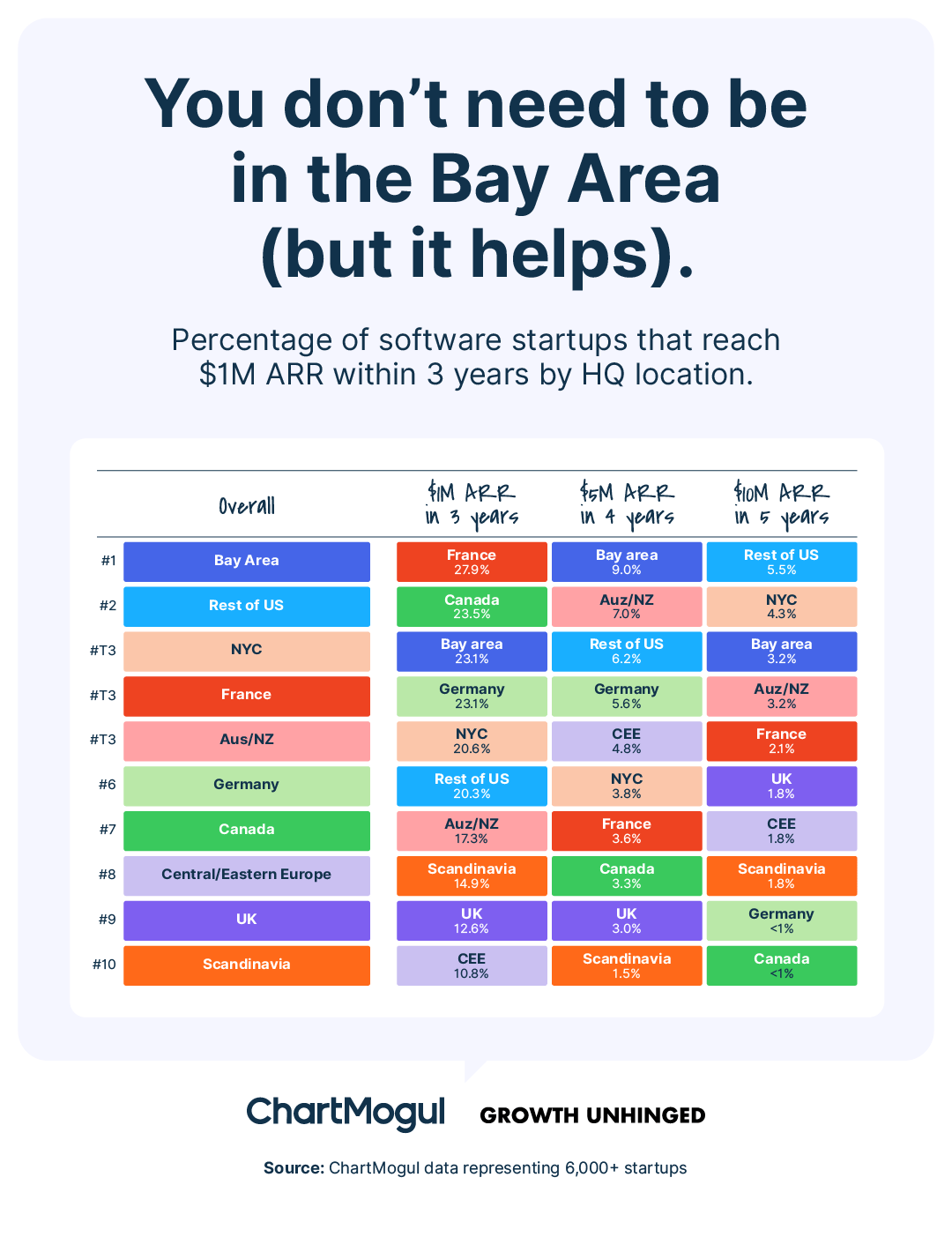

The specific growth rate that's right for your business depends on your product, your market, your team, and your capital. There's no universal "right" number. Some of the most valuable companies in the world grew slowly in their first few years. Some grew explosively.

What they all had in common was that they built something people genuinely wanted, that they had reasonable unit economics, and that they had retention rates that proved the product stuck around.

The ARR theater doesn't measure any of those things.

So here's what actually matters:

1. Build Something People Want

Spend time with customers. Understand their problems. Build something that solves those problems better than the alternatives. Don't optimize for growth at the expense of product quality.

2. Price Rationally

Price based on value, not scarcity or FOMO. Make sure your pricing makes sense relative to the value you're delivering. Be willing to turn away revenue that would destroy your unit economics.

3. Hire Carefully

Every person you hire compounds either forward or backward. Hire slowly. Hire for quality. Hire people who improve the culture and the product, not just people who can execute faster.

4. Track the Metrics That Matter

Retention. Unit economics. Customer acquisition cost. Lifetime value. Customer satisfaction. These are the metrics that predict whether you'll still be in business in five years. ARR growth does not.

5. Ignore the Twitter Comparison Game

Every founder you see on Twitter announcing a milestone has a story you don't know. You don't know if their ARR is real or run rate. You don't know if their retention is 90% or 40%. You don't know if they're actually profitable or burning millions per year.

You only know the narrative they've chosen to present.

Don't build your strategy around someone else's narrative.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Mistake 1: Conflating Growth with Success

Growth is easy when you have capital. Sustainability is hard. Don't optimize for the easy metric.

Mistake 2: Abandoning Profitability for Scale

There's a case for "invest in growth now, get profitable later." But many founders take this way too far and build businesses that can never be profitable given the unit economics they've established.

Mistake 3: Overhiring for Growth

More people does not equal more product. Sometimes it equals slower product because you're spending all your time managing people instead of building.

Mistake 4: Ignoring Retention as a Growth Driver

Retention is growth. If you're keeping 95% of your customers year over year, your revenue is compounding. You can hit the same ARR number with 10x less acquisition spend if your retention is good.

Mistake 5: Building for Investors Instead of Customers

Everything you do should be optimized for customer success and retention. If it's not, it's probably a mistake.

Looking Forward: What Changes When the Hype Cools

The AI boom won't last forever. When it cools, something interesting is going to happen: the companies with sustainable unit economics, good retention, and real customer value are going to thrive. The companies that were built purely for ARR theater are going to disappear.

This has happened in every technology cycle. The dot-com boom. The mobile boom. The blockchain boom. Each time, the rhetoric is "this time is different, growth is all that matters." And each time, when the capital dries up, the same boring metrics start mattering again: profitability, sustainability, real customer value.

The founders who are thinking five years ahead are already building for that world. They're not optimizing for the next Twitter moment. They're building something durable.

That's the real competitive advantage.

Conclusion: Building for Five Years, Not for Twitter

At its core, the ARR mania problem is about misaligned incentives and unrealistic narratives.

Venture capital has convinced founders that growth is the only metric that matters. Twitter has convinced everyone that growth means public announcements and superlative numbers. And the combination of those two forces has created a situation where many founders are making decisions that look good on a slide deck but are terrible for long-term business health.

But here's what's actually true: the most valuable companies in the world are the ones that built something durable first and let growth follow as a natural consequence. They found product-market fit. They established healthy unit economics. They hired thoughtfully. They built culture. They maintained retention.

The ARR number was never the goal. It was the result of getting everything else right.

So if you're a founder right now, feeling anxious about your growth rate relative to what other founders are tweeting, here's your permission to stop. To take a step back. To focus on the metrics that actually predict whether you'll be in business in five years.

Your retention rate matters more than your ARR growth rate.

Your unit economics matter more than your total revenue.

Your customer satisfaction matters more than your Twitter mentions.

Your team quality matters more than your headcount.

Build something durable. The growth will follow. And when it does, it will be real.

FAQ

What is the difference between ARR and revenue run rate?

Annual recurring revenue (ARR) is the annualized value of contracted, recurring subscription revenue—money from customers who have committed to ongoing payments. Revenue run rate is calculated by taking revenue earned in a short period (like one month) and multiplying it by 12 to project an annual figure. ARR is predictable and guaranteed through contracts; run rate is often based on one good month and may not repeat. This is the fundamental distinction that many founders conflate on social media.

Why are founders being pressured to achieve unrealistic ARR numbers?

Venture capital has become abundant and concentrated in the hands of VCs who make money by finding companies that grow explosively fast and eventually reach valuations at the unicorn level or higher. When a founder hits $100 million in ARR quickly, it signals the potential for a massive return. VCs have actively encouraged founders to chase these metrics through large funding rounds, competitive dynamics, and public narratives about what success looks like. Additionally, social media amplifies the most extreme success stories, creating FOMO and anxiety among founders who are growing at more sustainable rates.

What should founders focus on instead of ARR growth?

Founders should prioritize retention, unit economics, customer quality, and product-market fit. If 95% of your customers stay with you year after year, your revenue compounds without requiring ever-increasing customer acquisition spending. If your customer acquisition cost is low relative to lifetime value, your business can actually sustain itself. If your customers genuinely love the product, they'll help you grow through word-of-mouth and advocacy. These metrics are invisible on Twitter but absolutely critical for building a company that survives the inevitable downturns.

How can investors evaluate whether a startup's ARR is real or theater?

Investors should ask founders to break down their revenue into actual contracted ARR (multi-year commitments) versus run rate. They should ask for annual retention rates, which reveal whether customers actually stick around. They should understand what percentage of revenue comes from the largest customers—if 50% comes from five customers, that's a services business, not a scalable SaaS business. They should track the unearned revenue balance and understand customer acquisition costs relative to lifetime value. These questions separate sustainable businesses from ones built purely for the narrative.

What happens to fast-growing startups when growth slows?

Many startups that grew explosively on venture capital hit a wall when the capital cycle slows or when their burn rate catches up with their runway. Companies with poor retention discover that their revenue cliff is steeper than they expected. Companies with terrible unit economics realize they can't be profitable without cutting costs dramatically. Companies that hired too fast have to lay off significant percentages of their workforce. Companies that have solid fundamentals—good retention, reasonable unit economics, engaged customers—tend to weather downturns far better and often emerge as the category leaders.

Is there a "right" growth rate for startups?

The right growth rate depends entirely on your product, market, team, and capital situation. Some of the most valuable companies in the world grew slowly in their early years. Some grew explosively. What matters is that the growth is sustainable given your unit economics and customer retention. A 10% month-over-month growth rate with 95% retention and healthy unit economics is genuinely better for long-term success than 50% month-over-month growth with 40% retention and negative unit economics. Growth is only valuable if it's durable.

How do retention rates affect long-term business value?

Retention is compound growth. If you have 95% annual retention, you keep 95% of last year's revenue without acquiring a single new customer. Your revenue base stays with you and grows. If you have 50% annual retention, you need to replace half your customer base every year just to stay flat. You're perpetually in a customer acquisition treadmill. Over five years, the difference is staggering: the first company might grow from

What operational challenges come with hypergrowth?

Companies growing from

How should founders handle Twitter pressure about growth metrics?

Every founder on Twitter is presenting a curated narrative of their business. You don't see the retention rate, the unit economics, the customer quality, the operational chaos, or the regulatory risks. You see the number that looks good. Building your strategy around someone else's highlight reel is a recipe for poor decisions. The solution is to ignore the Twitter comparison game entirely and focus on building a business with solid fundamentals. If you're hitting your retention targets, your customers are happy, your unit economics work, and your team is healthy, you're winning—even if your growth number sounds boring on Twitter.

Key Takeaways

- ARR (Annual Recurring Revenue) and revenue run rate are fundamentally different—most Twitter claims conflate the two

- Retention rate matters infinitely more than growth rate: 95% retention compounds exponentially while 50% retention means perpetual replacement mode

- Unit economics (CAC vs LTV) determine sustainability; many hypergrowth companies have negative or marginal unit economics

- Hypergrowth hiring causes operational chaos: 50 engineers in a quarter is chaos, not scalability

- Regulatory risk, compliance issues, and legal challenges often blindside fast-growing AI startups that prioritize growth over governance

- VC incentives actively push founders to chase unsustainable growth narratives rather than build durable businesses

Related Articles

- Mundi Ventures' €750M Kembara Fund: Europe's Deep Tech Revolution [2025]

- Resolve AI's $125M Series A: The SRE Automation Race Heats Up [2025]

- A16z's $1.7B AI Infrastructure Bet: Where Tech's Future is Going [2025]

- ElevenLabs 11B Valuation [2025]

- SNAK Venture Partners $50M Fund: Digitalizing Vertical Marketplaces [2025]

- Peter Attia Leaves David Protein: Longevity Startup Drama Explained [2025]

![The ARR Myth: Why Founders Need to Stop Chasing Unrealistic Growth Numbers [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/the-arr-myth-why-founders-need-to-stop-chasing-unrealistic-g/image-1-1770327425626.jpg)