Europe's Deep Tech Funding Crisis: Why Kembara Matters Now

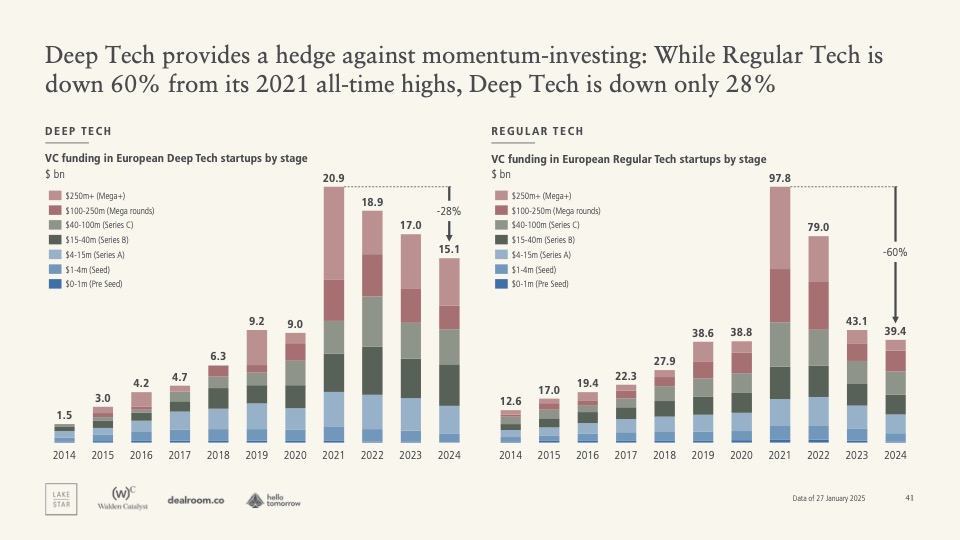

Europe has a problem nobody talks about at dinner parties, but it's keeping venture capitalists up at night. The continent produces some of the world's most innovative deep tech startups. The universities spin out brilliant companies. The founders are world-class. But somewhere between Series A and Series C, these companies disappear.

They don't fail because the technology is bad. They fail because the capital dries up.

Here's what's actually happening: European climate and deep tech startups raise seed money, maybe a solid Series A. Then they hit a wall. The gap between European growth capital and what these companies actually need is massive. Some companies go broke. Others get acquired for fractions of what they could become. A few lucky ones find capital abroad and leave Europe entirely, taking the jobs and the intellectual property with them.

That's the problem Mundi Ventures is trying to solve. And they just raised €750 million to do it.

Kembara Fund I, the fifth and largest fund from Mundi Ventures, just completed its first close with €750 million in commitments. The fund has regulatory approval to scale all the way to €1.25 billion if everything goes right. But getting to three-quarters of a billion euros as a first close in the current economic environment? According to the fund's leadership, that wasn't easy.

This isn't just another venture fund announcement. This represents a structural shift in how European deep tech gets funded. The team behind Kembara has seen the problem from every angle: as founders, as investors, as advisors, and as operators inside failed companies. They're building a different kind of fund for a different kind of problem.

Let's dig into what's actually happening here, why it matters, and what it means for the future of European deep tech.

TL; DR

- €750 million first close: Mundi Ventures' Kembara Fund I reached its initial target with potential to scale to €1.25 billion

- Focus on Series B/C: The fund targets growth-stage deep tech and climate startups when capital is hardest to find

- European champions thesis: Goal is to build European-scale companies rather than watching them sell to US acquirers

- New leadership team: Includes seasoned operators from Atomico, Lilium, and climate tech investing backgrounds

- Non-dilutive financing model: Combining venture capital with venture debt and alternative capital structures to reduce founder dilution

Estimated data shows a significant funding gap at Series B, where many European startups struggle to secure necessary capital, often leading to acquisitions.

The Series B Crisis: Where European Startups Go to Die

There's a brutal truth in European venture capital that most people don't realize: the gap between Series A and Series C is where the best companies disappear.

Series A is abundant. Seed rounds are abundant. Investors love backing ideas with impressive founders and novel technology. It's exciting. It's safe-ish because the check sizes are manageable. But then the company hits Series B. The capital required grows. The competition gets serious. The technology needs to scale not just technically but commercially.

That's when European founders start getting calls from Silicon Valley investors offering acquisition prices that look insane compared to what they've raised. A €20 million Series A looks small when Google is offering €200 million. Most founders take the deal. The acquirer gets a talented team and interesting IP. Europe loses a potential champion.

But what if that company could have raised a proper Series B? What if they could have scaled manufacturing, expanded into Asia, hired the team they needed? That €200 million acquisition price could have become a €2 billion business in five years.

This is exactly what happened with Lilium, the electric aircraft company where Kembara co-founder Yann de Vries was an operator. The company raised over $1 billion and went public via SPAC. It had brilliant technology. It had smart founders. It had all the ingredients for success. And then it ran out of capital. It couldn't bridge the gap to profitability or the next major revenue milestone. The company ceased operations in 2024.

De Vries watched this happen from the inside. He saw teams failing not because their technology was bad, but because the capital structure was wrong. Raising only in dilutive equity meant the company was constantly burning through founder ownership to fund growth. By the time they really needed cash, the cap table looked terrible.

That lesson is baked into Kembara's entire investment thesis. This fund isn't trying to do what other European VCs do. It's trying to fix the thing that actually breaks European deep tech companies.

Meet the Team: Operators Who've Lived Through the Pain

Kembara's leadership team looks different from typical venture funds, and that's intentional.

You've got Yann de Vries as co-founder and general partner. De Vries is a seasoned venture capitalist who founded Redpoint e Ventures Brazil, later became a partner at Atomico, and most importantly, left the investment side to join Lilium as an operator. That last move is crucial. He didn't just watch deep tech companies struggle from a spreadsheet. He lived through it. He experienced the capital challenges from inside the company.

Then there's Javier Santiso, founder of Mundi Ventures, who is now a co-founder and GP of Kembara. Santiso has been building Mundi as a platform for supporting European tech scale-ups across multiple funds. He's built the machine. Kembara is the machine operating at its most ambitious.

The other two general partners bring critical expertise. Robert Trezona is a climate tech VC with deep sector knowledge and a track record in climate infrastructure investing. Pierre Festal brings deep tech expertise. They're not generalists trying to learn climate and deep tech. They've spent years understanding how these sectors actually work.

And they brought in Siraj Khaliq as senior strategic advisor. Khaliq is a former partner at Atomico, the European deep tech fund that basically pioneered this space. He brings institutional knowledge about what works and what doesn't in European deep tech.

This matters because the fund isn't going to make the mistakes earlier European funds made. These are people who've seen which assumptions about capital, scaling, and European tech were wrong. They're building a fund based on lessons learned through actual failures.

Kembara leads the effort in providing growth capital for European deep tech, but significant contributions also come from LEC, Plural, and corporate ventures. Estimated data.

The €750 Million Vote of Confidence

Raising €750 million as a first close in 2024-2026 is notable for a specific reason: this was hard.

Venture capital in Europe has been contracting. The mega-funds of the 2020-2021 era seem like ancient history now. Limited partners are more cautious. The economic environment is uncertain. Geopolitics are complicated. Getting three-quarters of a billion euros committed to a new fund is a serious achievement.

What this tells you is that European institutional capital is serious about the deep tech thesis. Pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, endowments, and corporate strategic investors all committed to Kembara because they believe in the fundamental thesis: Europe needs growth capital for deep tech companies, and the returns will be exceptional when European champions actually exist.

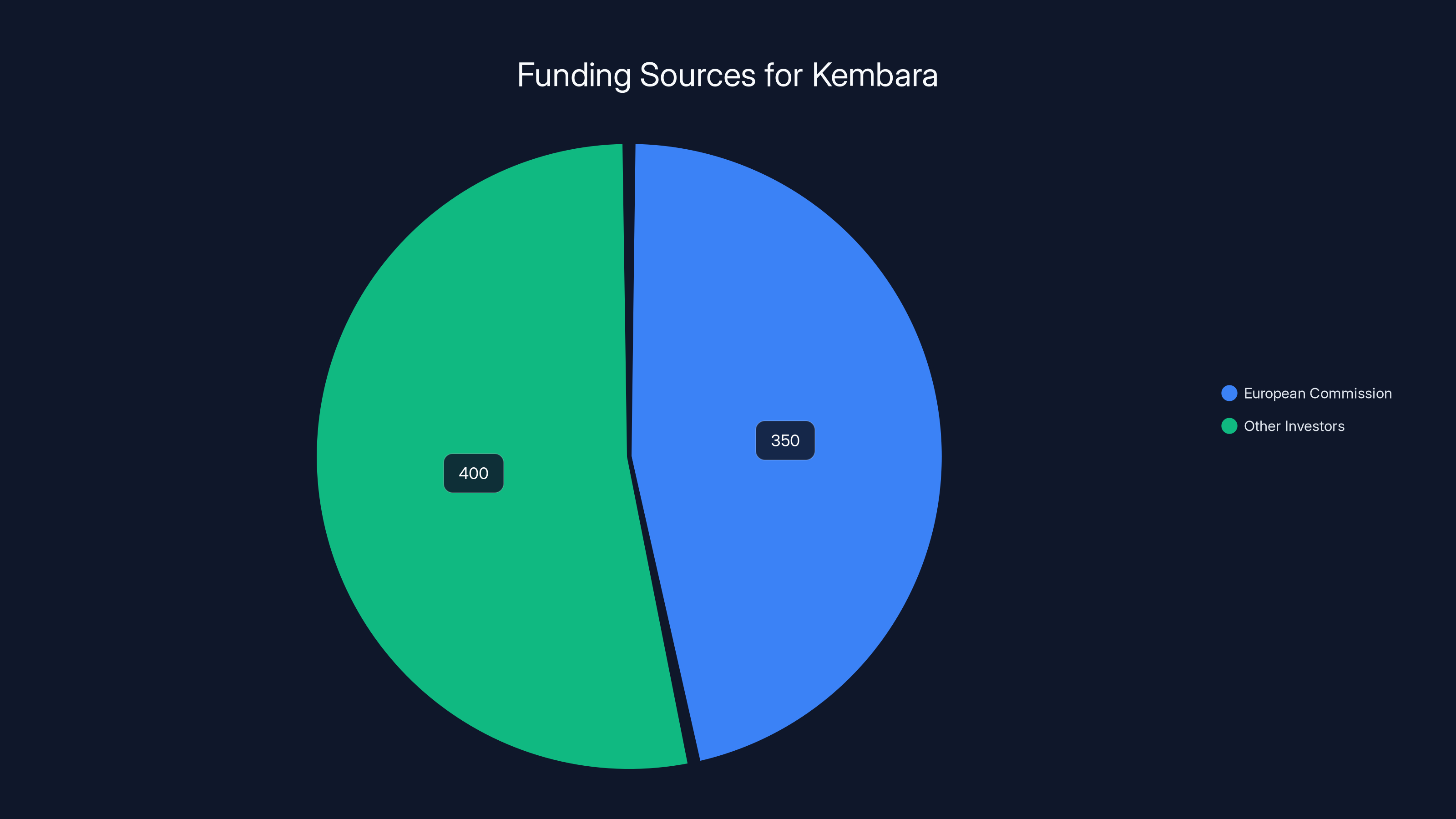

The fund got a major boost from the European Investment Fund under the European Tech Champions Initiative, which committed €350 million in 2024. That's a strong signal that European policymakers understand the problem too. They're not just talking about building European tech champions. They're putting capital behind it.

But the fact that Kembara had to raise €750 million in the first place tells you something else: the market knows this capital is needed. If European deep tech companies had other options for Series B and C funding, there wouldn't be room for a €750 million fund focused entirely on that problem.

Deep Tech Plus Climate: The Two Pillars of Kembara's Thesis

Kembara isn't a generalist fund. It's focused on two specific sectors: deep tech and climate tech. That focus is important because these are the areas where Europe actually has competitive advantages.

Deep tech is the obvious one. Europe's universities produce cutting-edge research in quantum computing, semiconductors, materials science, biotech, and physics-based hardware. Companies like these need massive capital to go from prototype to production. They need manufacturing infrastructure. They need supply chain expertise. They need capital that understands that the path to profitability takes longer than a SaaS company.

Climate tech is equally important but for different reasons. Europe is mandating climate solutions. The EU's regulatory environment is forcing the development of new technologies in everything from carbon removal to sustainable energy to circular manufacturing. That regulatory pressure creates a market. Companies that can serve that market while also exporting solutions globally can become huge.

But here's where it gets strategic: Kembara's thesis includes dual-use and defense tech to "protect European sovereignty." That language might sound abstract, but it's actually very concrete. European companies that build semiconductor manufacturing, satellite infrastructure, or quantum computing will be critical to European independence in a geopolitically fractious world.

That's why sovereign wealth funds and government bodies committed capital. It's not charity. It's strategic infrastructure investment. A European company that dominates semiconductor packaging or satellite manufacturing isn't just valuable as a business. It's valuable as an asset for European strategic autonomy.

The Series B/C Sweet Spot: Why This Check Size Matters

Kembara's strategy is to make initial checks between €15 million and €40 million into approximately 20 companies. That might sound like a lot of capital spread across a lot of companies, but it's actually carefully designed.

This check size is perfect for Series B and C companies. These are companies that have proven product-market fit at a small scale. They've raised seed and Series A. They know what they're building works. What they need now is capital to scale manufacturing, expand geographically, hire experienced operators, and build the business infrastructure to become a real company.

A €15-40 million check is substantial. It's enough to make a real difference in a company's trajectory. It's enough to cover 18-24 months of aggressive scaling. But it's not so large that it distorts the equity structure or makes follow-on financing impossible.

Where this gets really smart is the follow-on strategy. Kembara has committed to writing follow-on checks all the way up to €100 million per company if warranted. That means if one of their Series B investments becomes a breakout success, the fund can participate meaningfully in later rounds. That's critical because deep tech companies often need massive capital to scale.

Think about it: a quantum computing company might need €15 million for Series B to prove their algorithms in real-world conditions. If they succeed, they'll need €80 million for Series C to build manufacturing and sell to major customers. Having a fund that can double down at every stage means the company doesn't have to hunt for new capital from investors who don't understand their business.

Traditional financing significantly dilutes founder ownership by Series C, reducing it to 15%. Non-dilutive financing preserves more ownership, maintaining it at 25% by Series C. Estimated data.

Non-Dilutive Financing: The Capital Structure Innovation

Here's where Kembara is doing something genuinely different. The fund isn't just raising capital to deploy in traditional venture equity. It's building a financing platform.

The insight came directly from Lilium's failure. De Vries watched that company struggle because it was trying to fund a capital-intensive business using only dilutive equity. Every time they raised a round, founder ownership decreased. Every time they needed cash, they had to negotiate new terms that were worse than before. Eventually, the equity well ran dry.

Kembara is taking a different approach. The fund is building relationships with limited partners who don't just want to invest in the fund itself. They want to co-invest in winning companies through various instruments. Some LPs want to provide venture debt. Some want to provide equipment financing. Some want to provide revenue-based financing. Some want to provide non-dilutive grants.

The idea is that when a Kembara-backed company reaches a major inflection point, the fund doesn't just provide more equity. The company can access venture debt at reasonable terms. It can structure equipment financing. It can access non-dilutive grants from European government programs. By mixing dilutive and non-dilutive capital, the company optimizes its capital structure and minimizes dilution.

This matters enormously for deep tech. A semiconductor company needs expensive equipment. If it finances that equipment through a lease rather than buying it with equity capital, the math completely changes. A climate tech company might qualify for non-dilutive grants from EU climate programs. If the fund helps structure that financing, the company preserves equity for actual operating needs.

De Vries said it directly: "What we want to do now is to productize non-dilutive financing for these deep tech founders to help them de-risk their future financing and optimize the capital structure to minimize dilution."

This isn't just a nicer way to raise money. This is a structural advantage. European founders who have access to venture debt, grants, and equipment financing alongside venture equity can scale companies that US-only funded companies can't achieve.

The European Sovereign Wealth Play: Geopolitics as Capital

There's a geopolitical dimension to Kembara that you can't ignore. De Vries was explicit about it: "There's going to be a lot of support from sovereign wealth funds in Europe, from government, from corporations, to push and drive for building these European champions in deep tech out of Europe."

This isn't conspiracy thinking. This is how capital actually works in the 2025 environment. European governments watched what happened during COVID when they were dependent on semiconductors from Asia. They watched the US build strategic capacity in chips through the CHIPS Act. They watched China invest massively in semiconductor independence.

Europe decided it needed the same thing. But building semiconductor capacity requires private companies doing the heavy lifting. The government can't run fabs. But the government can ensure that European companies building semiconductor technology get the capital they need to scale.

That's why sovereign wealth funds from European countries committed to Kembara. They're not expecting venture-like returns. They're investing in strategic infrastructure. If Kembara-backed companies become leaders in semiconductors, quantum computing, advanced materials, or satellite technology, that's a win for European strategic autonomy.

This changes the risk calculus. Companies in Kembara's portfolio have patient capital behind them. The capital understands that these are long-term plays. The capital isn't going to force a quick exit to hit IRR targets in five years. The capital can wait for the companies to build real businesses.

The Scale-Up Problem: Why Europe Needs This

De Vries was clear about the core problem: "Europe doesn't have an innovation problem. It doesn't have a startup problem. The problem it has is a scale-up problem."

Read that carefully. He's not saying Europe can't innovate. He's saying Europe can't scale what it innovates.

The data backs this up. Europe's share of global tech market cap has been declining for decades. Not because European companies can't innovate. But because European companies don't scale the way US and Chinese companies do. A typical progression looks like this:

- European company innovates and raises seed capital

- Company raises Series A, proves something

- Company needs to raise Series B to go from 50 people to 200 people, from one market to three markets

- Series B capital is hard to find in Europe

- Company gets acquired or runs out of money

Compare that to a US company on the same trajectory. The US company has abundant Series B and C capital available. Every major VC has capital dedicated to growth-stage investing. There's competition for good deals. That competition drives capital into scaling companies.

Europe never built that infrastructure. The big VC funds focused on early stage. The corporate venture arms weren't hungry enough. The growth equity firms that did exist often focused on mature companies. That left a gap.

Kembara is trying to fill that gap on a bigger scale than has been attempted before. €750 million focused entirely on Series B/C deep tech and climate is a different level of capital concentration.

Europe's share of global tech market cap has been declining over the past two decades, highlighting the scale-up problem. Estimated data.

Learning From Deepmind: The Counterfactual That Haunts Europe

De Vries mentioned Deepmind in a specific way: as a company that was "missing this growth capital and sold too early."

Google acquired Deepmind for $500 million in 2014. At the time, that seemed like a huge price for a research company. Today, Deepmind is valued at billions. It's one of the most important AI research organizations in the world. And it's owned by Google.

Why does this matter? Because Deepmind didn't have to be acquired by Google. If there had been European growth capital available in 2014, Deepmind could have scaled as an independent company. It could have built AI products. It could have competed globally. It could have been a European champion.

Instead, Google captured the value. And Deepmind, while innovative and important, became a Google research division rather than an independent global company.

This is the haunting counterfactual that drives European VCs. How many "Deepminds" have been acquired at valuations that in retrospect look absurdly cheap? How many European companies could have become global champions if the capital had been available?

Kembara is betting that they can change that trajectory. By providing the growth capital European deep tech companies need, they can keep more of those potential champions European.

The Investment Strategy: 20 Companies, €15-€100M Range

Kembara's plan is to deploy capital into approximately 20 companies over the life of the fund. That's a focused portfolio. It's not trying to deploy into 200 companies across ten different strategies.

Initial checks range from €15 million to €40 million. Subsequent checks can go up to €100 million. This creates a clear strategy: the fund is looking for companies that have already demonstrated product-market fit but need capital to scale. These aren't early-stage bets where you're gambling on whether an idea will work. These are companies where the technology works, the founders have proven themselves, and the question is just whether they can scale.

For founders, this is interesting because it means Kembara isn't going to try to manage their company the way an early-stage investor would. They're not going to obsess over monthly metrics or try to dictate product strategy. They're going to ask: can this company scale? Do the founders understand how to build a company that scales? What capital structure do they need?

The focus on deep tech and climate means the fund is willing to take longer time horizons. Deep tech companies often take 7-10 years to reach meaningful scale. Climate tech companies are fighting regulatory headwinds and need to build real infrastructure. Kembara's LPs understand this. They're not expecting venture-like returns in five years.

Competition and Alternatives: The Shifting Landscape

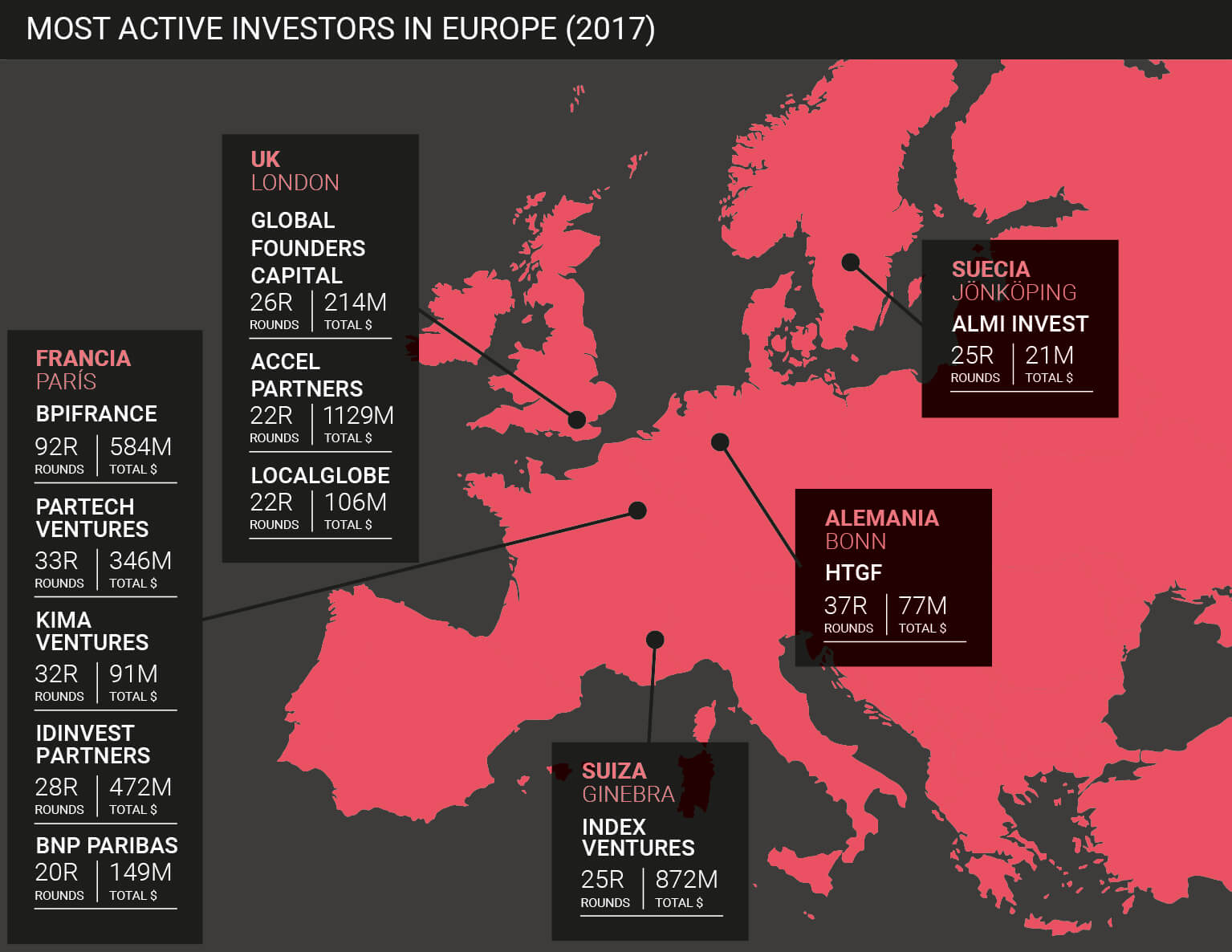

Kembara isn't alone in trying to provide European growth capital, though it's one of the largest efforts.

Elaia, a European deep tech VC firm, partnered with Lazard to create LEC (Lazard Elaia Capital). This fund is making initial investments between €20 million and €60 million per company. It's a similar thesis: Europe needs growth capital for deep tech, and the capital needs to understand the longer timelines involved.

Plural, an operator-led fund, is reportedly raising a new fund of up to €1 billion with a different approach: they're putting experienced operators on boards and helping companies scale operationally, not just financially.

There are also structural changes happening. Europe's largest VC funds are starting to have larger growth capital allocations. Corporate venture arms from companies like Siemens, ABB, and others are deploying more capital into deep tech scale-ups.

What this suggests is that the market is correcting itself. Capital is flowing toward the scale-up problem because everyone recognizes it's real. Kembara is the largest single effort, but it's part of a broader trend.

Estimated data shows that if European AI companies like Deepmind had access to growth capital, their valuations could have been significantly higher, potentially reaching billions instead of being acquired early.

The Defense Tech and Sovereignty Angle: Why It Matters

Kembara's focus on "dual-use and defense tech to protect European sovereignty" might sound like boilerplate until you understand what it actually means.

Europe is waking up to a reality: it's dependent on the US for military technology, and it's dependent on Asia for critical semiconductors. Neither of these dependencies is comfortable. Ukraine made this clear. When Europe tried to help Ukraine defend itself, it discovered that some types of military technology were restricted and not available through normal channels.

That created an imperative to build European capacity in critical defense technologies. But you can't announce "we're funding defense companies to reduce US dependency." That's not diplomatic. Instead, you fund deep tech companies that have commercial applications but can also serve defense needs.

A European company that builds quantum computers is dual-use: it has commercial applications in finance and cryptography, but it also has defense applications in secure communications. A European company that builds advanced semiconductors is dual-use: commercial applications in AI and computing, plus defense applications in military systems.

Kembara's willingness to invest in these areas signals that European LPs believe the geopolitical calculus has shifted. Europe needs strategic independence in critical technologies. That independence comes from having independent companies building critical technologies. And those companies need capital.

The Regulatory and Policy Backdrop: When VCs Meet Government

Kembara's ability to raise €750 million isn't separate from European policy. It's a direct result of European policy.

The European Commission created the European Tech Champions Initiative specifically to drive capital into European deep tech scale-ups. That initiative committed €350 million to Kembara. That's not investor capital voting on expected returns. That's government capital voting on strategic importance.

That government capital changes the dynamics. It makes it easier to raise institutional capital because there's already a credible partner with deep pockets committed. It signals policy support, which reduces political risk. It suggests that European founders building deep tech companies are operating in a supportive environment.

In contrast, European climate tech companies have faced policy uncertainty. Will carbon pricing stick? Will climate subsidies continue? Will regulations actually require the technologies that are being developed? Kembara's LPs decided the answer is yes. The European commitment to climate transition is real. Companies that build climate solutions will have markets.

That policy backdrop matters enormously for what companies Kembara can fund and whether those companies will succeed.

The Dilution Problem: Why Traditional Financing Doesn't Work for Deep Tech

Deep tech companies face a unique financing challenge that vanilla venture capital doesn't solve.

Think about the trajectory of a semiconductor equipment company. Year 1-2: raise €10M seed. Build the prototype. Year 2-3: raise €30M Series A. Start production of first equipment. Year 3-4: raise €50M Series B. Scale production, enter multiple markets. Year 4-6: raise €100M Series C. Build factories, hire engineers, dominate the market.

In total, the company raised €190 million. But the founder's ownership went from 100% (before seed) down to maybe 15-20% by Series C. Every round diluted existing shareholders.

For a typical SaaS company, that's fine. The company might be profitable much earlier, so later rounds can be at lower dilution. But a deep tech company often doesn't reach profitability until after Series C. By that point, the founders have been massively diluted.

If you could replace €50M of the Series B with a combination of €20M equity and €30M venture debt, the math changes completely. The company still has €50M to work with. But the equity round is 60% smaller. The founders get diluted less. The long-term upside is preserved better.

This is why Kembara's commitment to non-dilutive financing is such a big deal. It's not just nicer for founders. It's strategically important. European deep tech companies with better capital structures will outcompete US companies with worse capital structures over the 10-year horizon.

The European Commission contributed €350 million, nearly half of Kembara's €750 million funding, emphasizing the strategic importance of government support in venture capital.

What Happens Next: The 2-3 Year Deployment Plan

Kembara has €750 million at first close. The target is to reach €1 billion at final close (with potential to go to €1.25 billion).

They plan to deploy into approximately 20 companies. That means the average initial investment is roughly €37.5 million (€750M / 20 companies). Given the stated range of €15-€40 million, some companies will get smaller checks and others larger.

Over the next 2-3 years, Kembara will be actively deploying this capital into Series B and C companies across deep tech and climate. The team will be looking for companies that have achieved product-market fit, have experienced founding teams, and have the ambition to become European champions.

They'll also be building the non-dilutive financing ecosystem. Relationships with venture debt providers, equipment financiers, and grant programs need to be formalized and productized.

The success metrics will be clear: did they fund companies that scaled? Did any of those companies become European champions? Did the non-dilutive financing model actually reduce dilution compared to traditional VC financing?

These are multi-year questions. But the fact that €750 million is already committed means the capital is patient. Kembara isn't going to push for quick exits. The fund is built for the long game.

The Founder Experience: What This Means for European Founders

If you're a European deep tech founder, Kembara changes the landscape of options available to you.

For the first time, there's a credible source of growth capital specifically designed for deep tech companies. The lead investor understands the sector. They understand the capital needs. They understand that 10-year timelines are normal. They have relationships with venture debt providers and alternative capital sources.

That's different from raising Series B from a generalist fund that doesn't understand the industry. Or from founders having to raise from multiple sources and spend months negotiating different capital structures.

Kembara isn't just writing checks. They're building an ecosystem around European deep tech scale-ups.

For an ambitious European founder working on quantum computing, semiconductors, advanced materials, or climate solutions, that ecosystem is meaningful. It suggests there's a path to building a real company in Europe. You don't have to sell to Google or move to Silicon Valley.

That changes behavior. When founders believe there's a path to European scale and success, they make different choices. They invest in hiring. They invest in building real infrastructure. They think about being independent companies, not acquisition targets.

Kembara is betting that European founders, given proper capital, will build better companies than they would have otherwise.

The Challenges Ahead: Execution Risk Is Real

Raising €750 million is impressive. Deploying it wisely is hard.

Kembara will need to identify 20 truly exceptional companies across deep tech and climate. They'll need to structure deals that work for both the company and the fund. They'll need to help these companies scale in a still-uncertain economic environment. They'll need to build the non-dilutive financing ecosystem they've promised.

And they'll need to do all of this while global economic conditions remain uncertain. If there's a recession or a capital crunch, limited partners might get nervous. Companies might struggle to reach their milestones. The whole thesis could get tested.

The team has experience and credibility. But execution is always harder than strategy. Getting to €750 million is one milestone. Converting that into a portfolio of successful deep tech companies is a different mountain.

Still, the fact that they've already demonstrated they can raise this capital is a good sign. Markets don't commit €750 million to funds that investors don't believe in.

The Global Implications: Why This Matters Beyond Europe

Kembara is a European fund solving a European problem. But it has global implications.

The rise of European growth capital for deep tech creates competition for US venture capital. It creates alternatives for founders who might otherwise only have US options. It creates the possibility that the next breakthrough in semiconductors, quantum computing, or climate tech could come from a European company.

For the US venture industry, this is a wake-up call. If European capital is doing a better job of funding deep tech scale-ups than US capital, that's a problem for US innovation. If European companies start dominating sectors that were previously US-dominated, that changes the geopolitical landscape.

For founders globally, this is interesting because it suggests that the venture capital market is finally recognizing that deep tech needs different capital than software. Longer timelines. Patient capital. Specialized expertise. Understanding of manufacturing and scaling. If Kembara works, other regions will copy the model.

FAQ

What is Kembara Fund I?

Kembara Fund I is a €750 million (with potential to reach €1 billion) venture capital fund managed by Mundi Ventures. The fund focuses on deep tech and climate tech companies at the Series B and C stages, aiming to bridge the growth capital gap for European companies building potential global champions.

Why did Kembara raise such a large fund for Series B/C investing?

The fund was created to address a specific gap in European venture capital: growth-stage deep tech and climate companies often struggle to find sufficient capital to scale from Series B to Series C. This gap has historically forced European companies to either accept acquisition by foreign buyers or run out of capital. Kembara's size allows it to deploy meaningful capital per company (€15-€100M) while maintaining a focused 20-company portfolio.

How is Kembara different from other European venture funds?

Kembara differentiates itself through several mechanisms: (1) it combines traditional venture equity with non-dilutive financing options like venture debt and equipment financing to optimize capital structures, (2) it brings together a team with deep operational experience in the sectors it invests in, and (3) it has European institutional backing including sovereign wealth funds and the European Investment Fund, signaling patient, long-term capital.

What sectors does Kembara focus on?

Kembara invests across deep tech and climate tech with particular emphasis on sectors critical to European sovereignty including semiconductors, quantum computing, advanced materials, satellite technology, spacetech, and climate solutions. The fund also focuses on dual-use and defense tech that can serve both commercial and strategic security purposes for Europe.

What is non-dilutive financing and why does it matter for deep tech?

Non-dilutive financing includes venture debt, equipment leasing, grants, and revenue-based financing that don't require founders to give up equity ownership. For deep tech companies that require massive capital across many rounds, mixing non-dilutive and dilutive capital preserves founder ownership and improves long-term company independence, which Kembara emphasizes as crucial after the lessons learned from companies like Lilium.

Who are the limited partners investing in Kembara?

Kembara's limited partners include the European Investment Fund (which committed €350 million under the European Tech Champions Initiative), sovereign wealth funds from European countries, government bodies, corporate strategic investors, and institutional investors including pension funds and endowments. This mix of patient capital distinguishes Kembara from traditional venture funds with shorter return horizons.

How long does Kembara expect to hold investments?

Given the fund's focus on deep tech and climate companies, which typically take 8-10 years to reach meaningful exits or IPOs, Kembara's fund structure and LP composition are designed for longer holding periods than typical venture funds. This patient capital approach is fundamental to the fund's ability to support companies through the challenging scale-up phase.

What is the European scale-up problem that Kembara is solving?

Europe produces exceptional deep tech innovations but historically has struggled to scale those innovations into global companies. The gap occurs at Series B/C when companies need massive capital to build manufacturing, expand internationally, and achieve profitability. Without local capital sources, European founders often sell to foreign acquirers or fail, meaning Europe loses potential global champions. Kembara specifically targets this gap.

How many companies will Kembara fund and at what stage?

Kembara plans to invest in approximately 20 companies across the Series B and C stages. Initial check sizes range from €15 million to €40 million per company, with capacity to follow on with checks up to €100 million per company in winning investments. This approach allows the fund to maintain a focused portfolio while deeply supporting each company through scaling challenges.

What is the significance of Yann de Vries' experience at Lilium?

De Vries' tenure at Lilium, which ceased operations in 2024 despite raising over $1 billion, taught him that pure equity financing doesn't work for capital-intensive deep tech companies. The company lacked access to venture debt and alternative capital structures that could have extended runway without excessive equity dilution. This experience directly shaped Kembara's innovation of combining equity with non-dilutive financing options.

Conclusion: The Bet on European Independence

At its core, Kembara represents a bet on European technological independence and entrepreneurial capability.

The fund isn't pretending to be something it's not. It's not the next Open AI investment or a Facebook-killer fund. It's a focused, patient capital source for companies building the unglamorous but essential infrastructure that nations need: semiconductors, quantum computers, climate solutions, manufacturing technology.

The €750 million first close proves that institutional capital—governments, sovereign wealth funds, pension funds—believes in this thesis. It believes Europe needs independent capacity in critical technologies. It believes European founders, given proper capital, will build global companies. It believes the long-term returns from funding deep tech scale-ups will justify patient capital.

But the real test comes now. The team needs to deploy this capital into exceptional companies. They need to help those companies scale faster and with less dilution than their competitors. They need to prove that European deep tech companies, properly funded, can compete globally.

If they succeed, Kembara becomes a template. Other European institutions will follow. More capital will flow toward European deep tech scale-ups. The next generation of European tech champions will stay European instead of being acquired or sold.

If they fail, it's a sign that the problem is harder than even experienced operators realized. That Europe's issue isn't capital but something deeper about execution, commercialization, or culture.

For founders, investors, and anyone watching European tech, Kembara is the biggest bet Europe has made on solving its scale-up problem. The next two years will be revealing.

Key Takeaways

- Kembara Fund's €750M first close addresses Europe's critical scale-up problem where companies struggle between Series A and Series C

- The fund combines traditional venture equity with non-dilutive financing (venture debt, equipment leasing, grants) to optimize capital structures and reduce founder dilution

- Kembara's leadership team includes operators who lived through deep tech failures (Lilium), directly shaping the fund's approach to patient capital

- European institutional capital including sovereign wealth funds committed to Kembara, signaling geopolitical recognition of Europe's need for strategic technology independence

- The fund targets approximately 20 deep tech and climate companies with initial checks of €15-40M and follow-on capacity up to €100M per company

Related Articles

- Resolve AI's $125M Series A: The SRE Automation Race Heats Up [2025]

- A16z's $1.7B AI Infrastructure Bet: Where Tech's Future is Going [2025]

- ElevenLabs 11B Valuation [2025]

- SNAK Venture Partners $50M Fund: Digitalizing Vertical Marketplaces [2025]

- Peter Attia Leaves David Protein: Longevity Startup Drama Explained [2025]

- Nvidia's $100B OpenAI Gamble: What's Really Happening Behind Closed Doors [2025]

![Mundi Ventures' €750M Kembara Fund: Europe's Deep Tech Revolution [2025]](https://techcrunch.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/KEMBARA.jpg?w=1200)