Social Media Giants Face Historic Trials Over Teen Addiction and Mental Health: The Reckoning Is Here

Lori Schott made a promise to herself long before she stepped into that Los Angeles courthouse. She was going to be there. No matter what it took.

Her daughter Annalee died by suicide in 2020 at age 18. Body image issues. Relentless comparison to other girls' Instagram profiles. Journal entries filled with self-hatred, traced back to what she saw scrolling through social feeds.

"I was so worried about what my child was putting out online," Schott told reporters outside the courthouse. "I didn't realize what she was receiving."

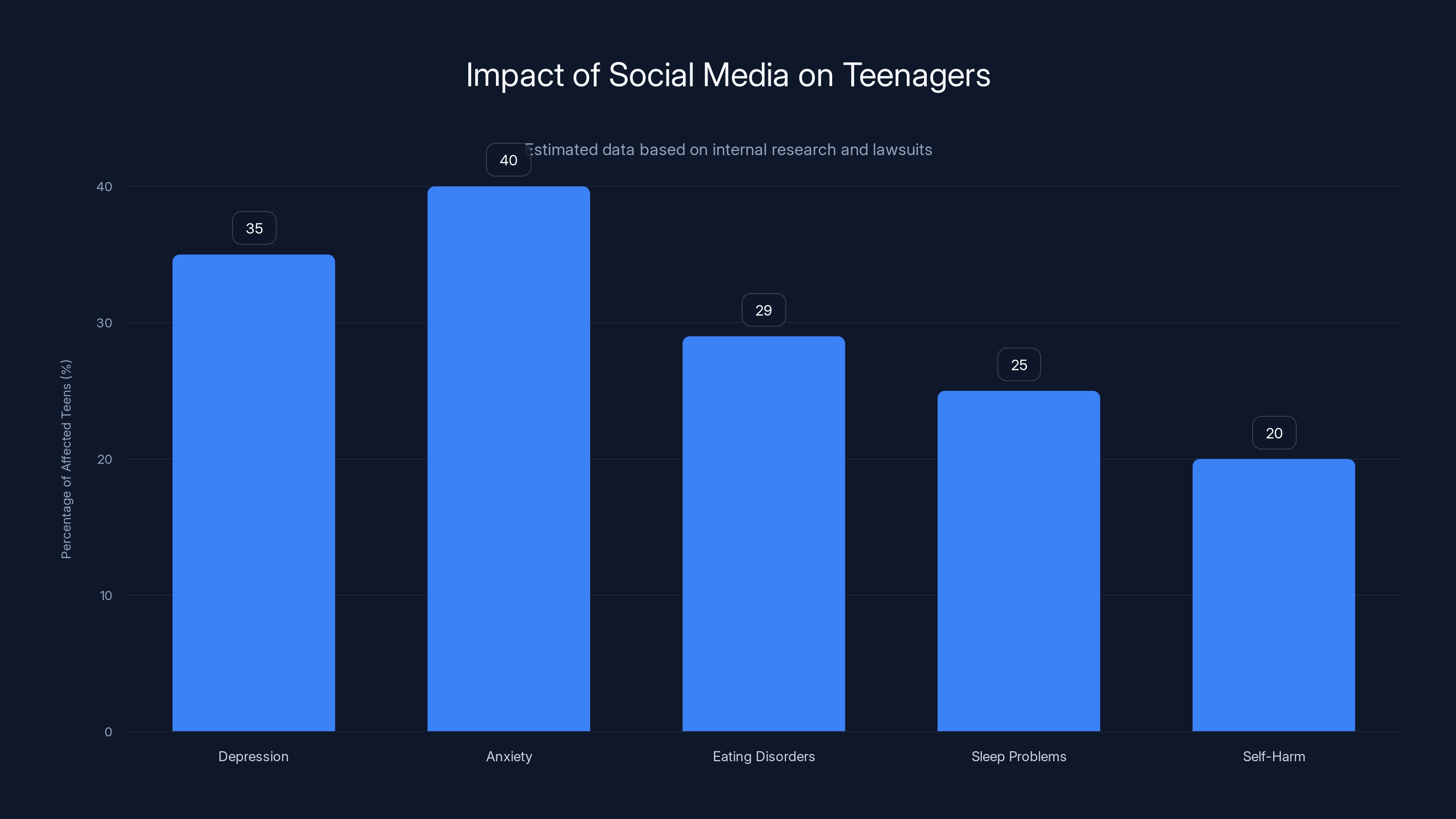

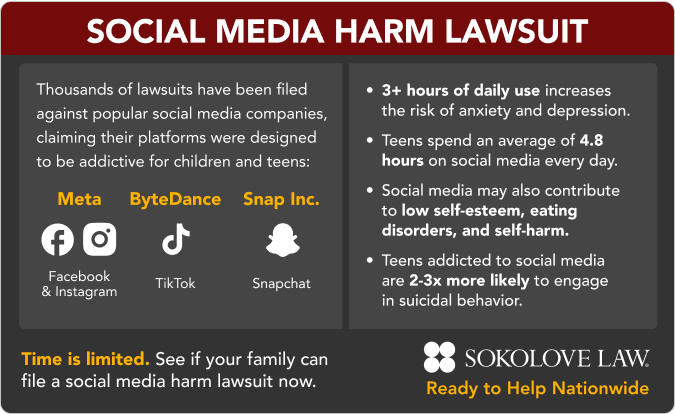

For years, tech companies have faced accusations that their platforms—Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Snapchat, YouTube—are designed to be addictive, deliberately targeting teens, and knowingly causing depression, anxiety, eating disorders, and self-harm. But here's what makes this moment different: these cases are finally making it to trial.

Not dismissed on technicalities. Not buried in settlement agreements. Actually going to court, where executives like Mark Zuckerberg will have to answer questions under oath about what they knew and what they did (or didn't do) to protect kids.

This isn't some abstract policy debate anymore. This is the reckoning.

What You're About to Witness

Think of these trials as a stress test for the entire social media business model. For two decades, platforms built their empires on one fundamental principle: engagement equals profit. The more time you spend, the more data they collect, the more ads they sell, the more money they make.

Teen users, it turns out, are incredibly valuable to this equation. They're on their phones constantly. They're forming their identities. They're vulnerable to psychological manipulation in ways that adults often aren't.

The problem—and the reason we're here—is that internal documents show companies knew exactly how their products affected young brains. They discussed it. They documented it. They did it anyway.

What you're about to read is the story of how we got here. The science behind social media addiction. The legal arguments that might finally hold Big Tech accountable. The families who've been fighting for answers. And what happens next if these cases succeed.

Because the outcome of these trials won't just affect Facebook or TikTok. It could reshape how every digital platform is built and regulated for the next decade.

TL; DR

- The Cases Are Real: Multiple bellwether lawsuits accusing Meta, TikTok, Snapchat, and YouTube of causing teen mental health harm are going to trial in 2025, not being dismissed on legal technicalities.

- Internal Documents Damning: Released company communications show executives discussed targeting teens, understood engagement risks, and continued aggressive growth strategies anyway.

- No Section 230 Protection: Unlike earlier challenges, these cases overcame Section 230 defenses by framing harm as resulting from product design, not user-generated content.

- Mark Zuckerberg Is Testifying: The Meta CEO will take the stand to answer questions about what the company knew about Instagram's effects on teen girls' body image.

- This Is Just the Beginning: If plaintiffs prevail, expect a cascade of similar cases and potential major regulatory changes to how platforms operate.

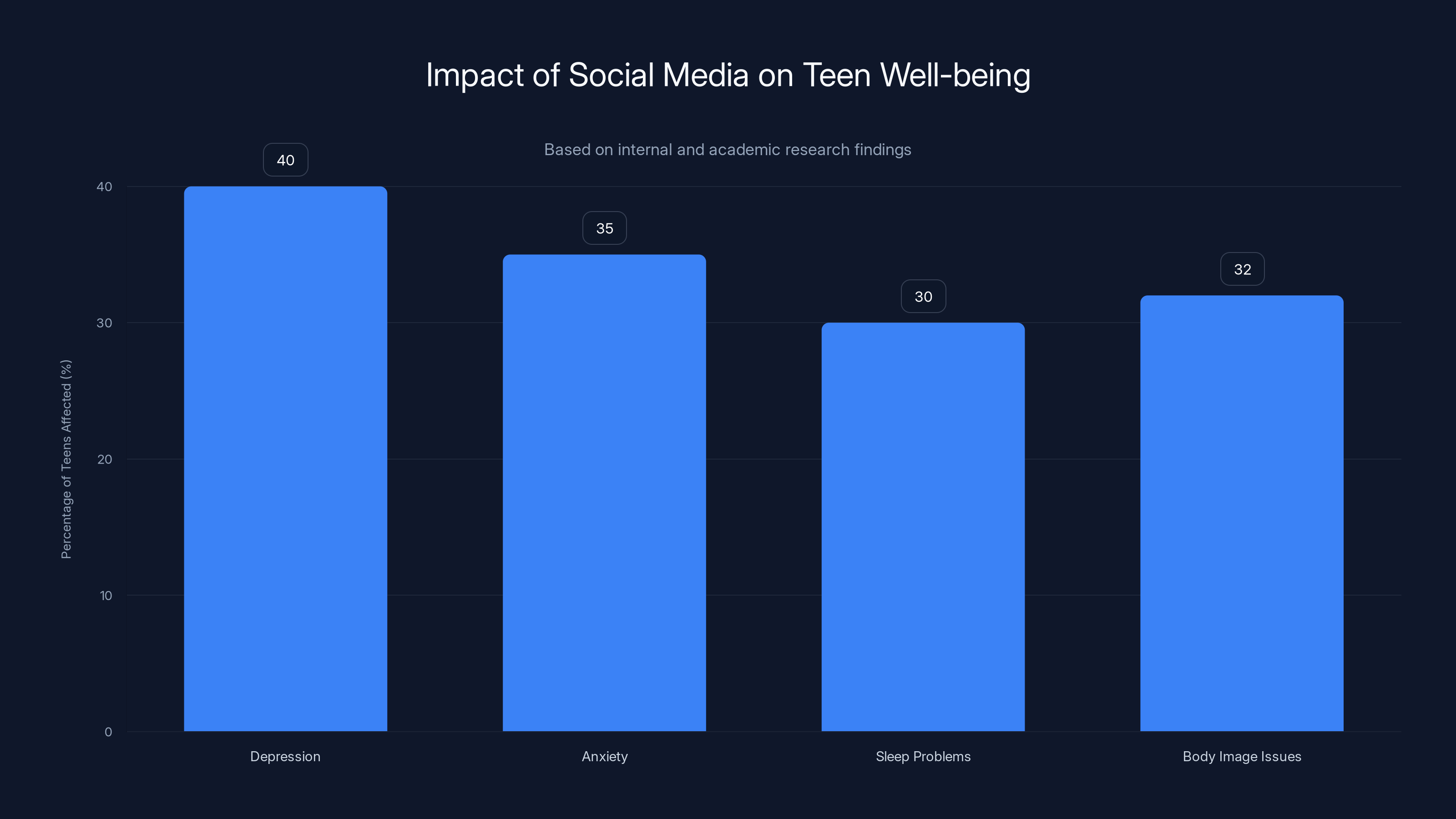

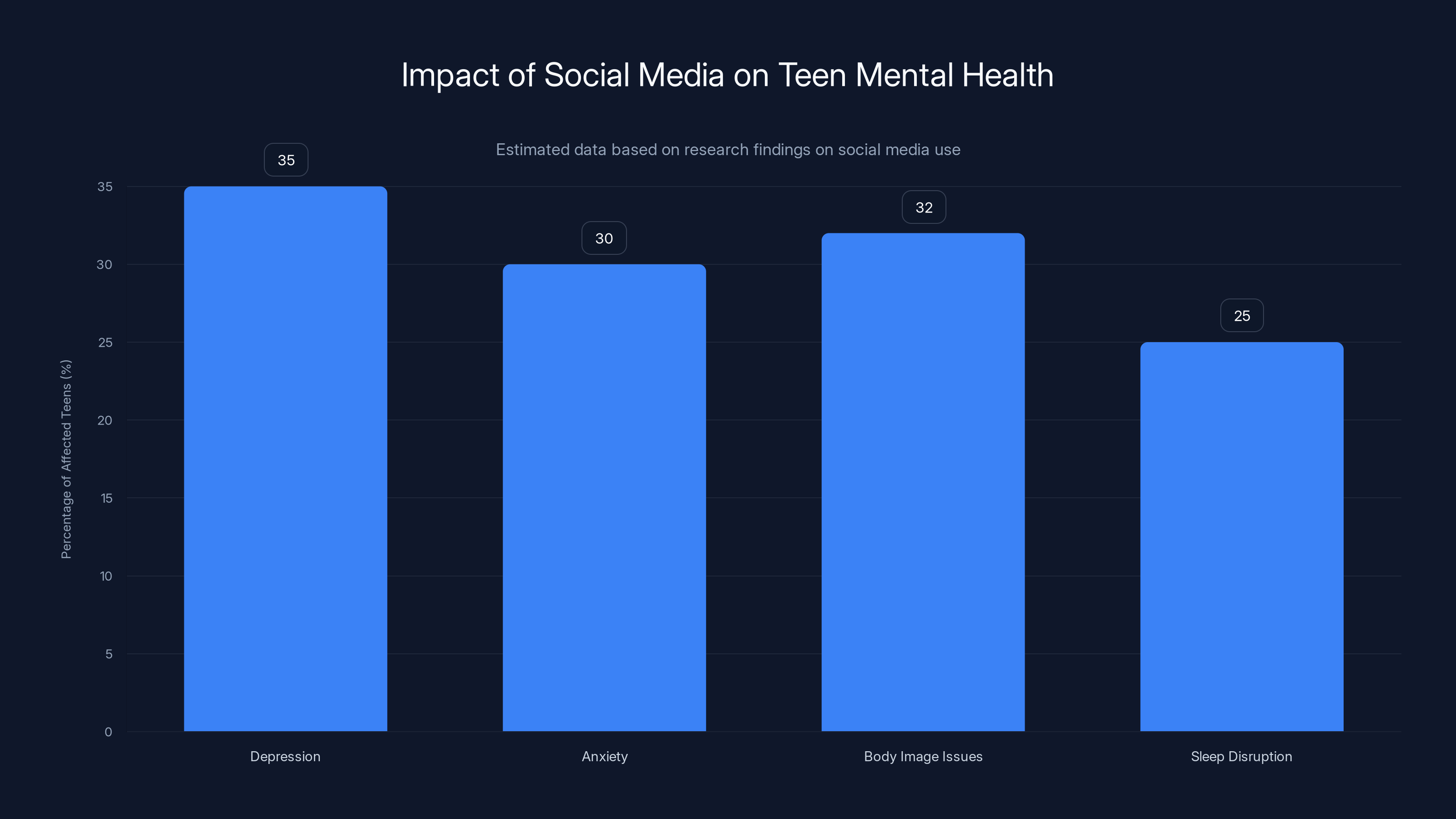

Internal documents and research indicate significant negative impacts of social media on teen well-being, with body image issues affecting 32% of teen girls.

The Road to Trial: How Social Media Cases Finally Survived Legal Obstacles

Understanding Section 230: Why It Existed and Why It Wasn't Enough

For nearly 30 years, Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act has been the legal shield protecting internet platforms from lawsuits. The logic was straightforward: if users post content, don't sue the platform for what users say. It made sense in the 1990s when forums and message boards were new.

But here's the crucial detail courts are recognizing now: these cases aren't about user-generated content. They're about platform design.

When someone sues and says "Instagram caused my daughter's eating disorder," they're not claiming that other users' posts harmed her. They're claiming Meta deliberately engineered the algorithm, the recommendation system, the notification system, and the design features to maximize engagement in ways the company knew would harm teens psychologically.

That's different. That's product design. That's the company's responsibility.

Think of it like this: Section 230 wouldn't protect a car company if they designed brakes that fail at high speeds. The brakes are the company's design choice. Similarly, courts are saying that if a platform designs its engagement mechanics in ways that predictably harm teens, that's the platform's liability, not the users'.

This distinction is why these cases got past the dismissal stage. Judges looked at the pleadings and said: "Yeah, this could actually go to trial."

The Bellwether Strategy: Why These Cases Matter

You'll hear the word "bellwether" a lot. It means a test case whose outcome signals which way a larger group of cases will go. Think of it as the canary in the coal mine for Big Tech.

Right now, there are roughly 400 cases pending against social media companies. Most are waiting. Watching. Seeing if the bellwether cases succeed or fail.

If families win even one of these trials? You're looking at potential liability in the billions. You're looking at a flood of similar cases in every state. You're looking at fundamentally different regulations.

If companies win? It signals that despite the mountains of evidence, the legal system isn't going to hold them accountable for teen harm. And the cases quiet down.

That's why the stakes feel enormous. Because they are.

What the Internal Documents Actually Show: The Evidence That Changed Everything

The Engagement Problem: What Companies Knew

In early 2024, court documents started getting released. Emails. Slack channels. Product review meetings. Internal strategy memos.

They were devastating.

Meta engineers had discussions about "teen engagement loops." How do you make teenagers come back? What hooks work? How do you keep them scrolling?

Snapchat executives talked about the value of "teen acquisition." Teenagers are valuable users. They're developing their habits. If you can addict them at 14, you've got them for life.

TikTok's growth strategy was explicit: dominate the teen market first, monetize later. Get them young. Get them engaged. Everything else follows.

YouTube executives knew that kids were watching content that wasn't appropriate for kids, yet the algorithm kept recommending it because it drove engagement.

This isn't speculation. This is what the documents say.

Here's the problem: the companies also knew—and documented—that heavy engagement with their products was correlated with depression, anxiety, sleep problems, and body image issues. Internal research showed it. Academic research confirmed it. They knew.

And they built more engagement features anyway.

The Body Image Trap: Instagram's Specific Problem

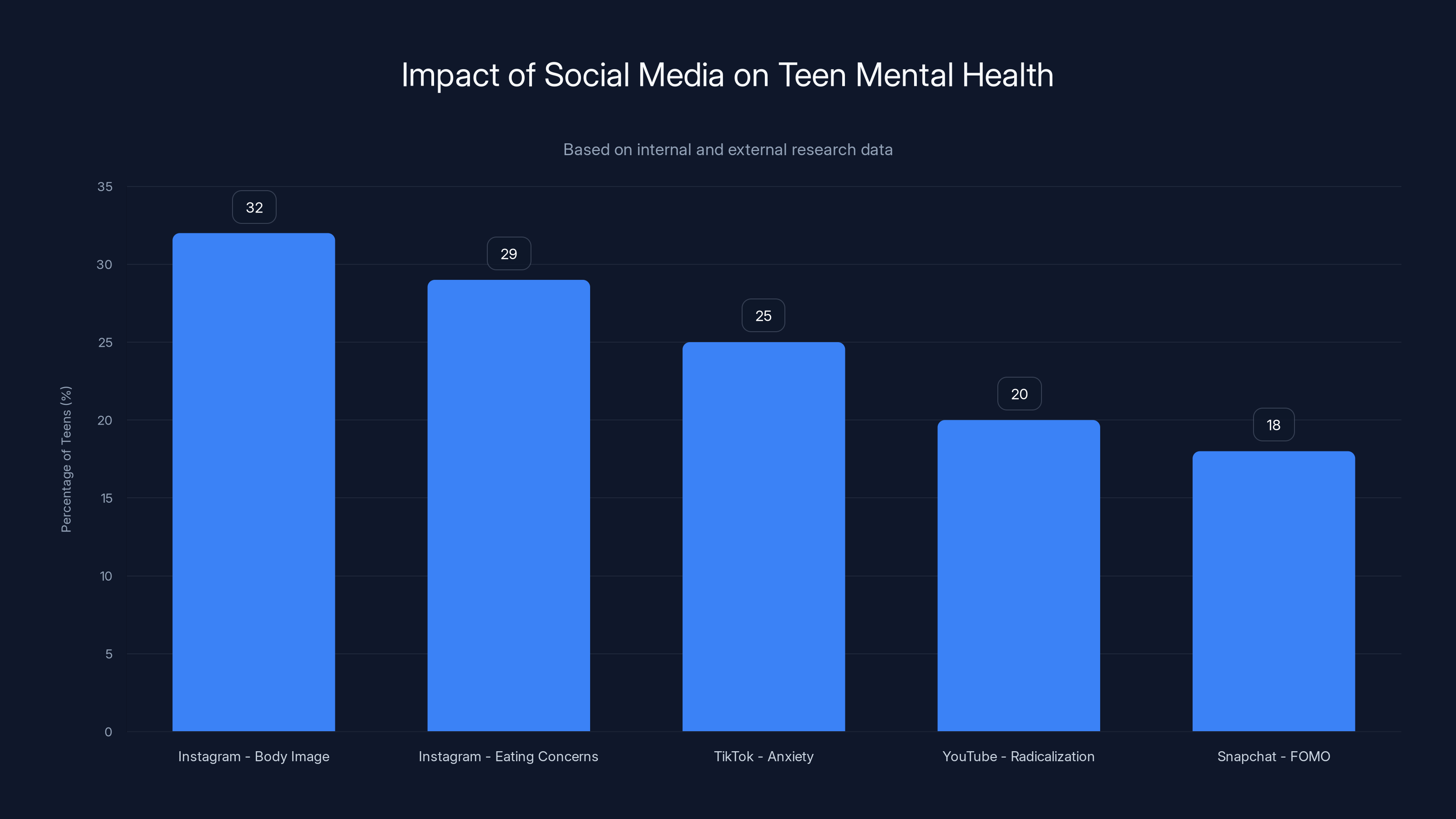

Instagram represents the clearest case of intentional harm, according to legal arguments. The platform is fundamentally built around visual comparison.

You post a photo. You get likes. You check back obsessively to see if more people liked it. Meanwhile, you're scrolling through feeds of girls who are filtered, edited, and professionally photographed, creating impossible standards.

Internal documents show Meta knew this specifically hurt teen girls. A leaked Facebook research presentation showed that Instagram made body image worse for 32% of teen girls surveyed, and for some girls, it made the problem significantly worse.

But instead of redesigning the platform to reduce comparison-focused features, Meta added more engagement hooks. Stories. Reels. The "Likes" count (which they briefly hid, then brought back because engagement dropped). Video recommendations that showed increasingly extreme content.

For a teenage girl struggling with her appearance, Instagram wasn't a neutral tool. It was a machine designed to make her compare herself constantly, feel inadequate, and keep coming back for validation through likes.

That's not accident. That's design.

The Addiction Mechanics: How Platforms Hook Teen Brains

Every major social platform uses the same psychological toolkit:

Variable rewards: You don't know if your post will get 10 likes or 100. That unpredictability triggers dopamine hits. Your brain responds like a slot machine. One more scroll. One more check.

Infinite scroll: There's no natural stopping point. Older platforms ended at a page break. Apps just keep going. Your brain never gets the signal to stop.

Notification urgency: Red badges. Badges with numbers. Buzzes and pings. Designed to create FOMO (fear of missing out). Someone interacted with your content. You need to check immediately.

Social validation systems: Likes, comments, shares, followers. Quantified social approval. For teens still forming their identities, this is powerful psychological territory. A low-like post feels like social rejection.

Algorithmic amplification of extreme content: The algorithms learned that outrage, comparison, and anxiety drive engagement. So they show you more of it. Not the wholesome content your friends posted. The stuff that makes you emotionally activated.

Teen brains are particularly vulnerable to these mechanics because the prefrontal cortex—the part responsible for impulse control and risk assessment—isn't fully developed until the mid-20s. They're literally neurologically more susceptible to manipulation.

Companies know this. They know they're leveraging a developmental vulnerability. And the evidence shows they discussed it intentionally.

Estimated data suggests a significant percentage of teens experience mental health issues due to social media platform designs. Estimated data.

Mark Zuckerberg Takes the Stand: What to Watch For

The Questions He'll Face

When Mark Zuckerberg sits down to testify, here are the lines of questioning that matter:

On Internal Knowledge: "Did you read the research showing Instagram's negative effects on teen body image? When you read it, what did you think? Why didn't the company redesign the product?"

His testimony will either confirm that he knew and didn't care, or that he didn't know (which makes him negligent). Either way, it's liability.

On Alternative Designs: "Could you design Instagram without engagement metrics like likes? Could you remove infinite scroll? Could you limit daily usage? If you could, why didn't you?"

If he says it's technically possible but they didn't do it, that shows choice, not necessity. Choice is where liability lives.

On Teen Targeting: "Did Meta intentionally market to teens? Did executives discuss teen acquisition as a strategic priority? If so, why specifically target the most vulnerable users?"

Internal documents already show the answer. His testimony will either confirm it or contradict the documents, which destroys his credibility.

On Knowability: "If you didn't know Instagram harmed teens, why not? What processes did you have to understand your product's effects? Why were those processes insufficient?"

Negligence is often easier to prove than intentional harm. A company that says "we didn't check" is still liable.

The Meta Defense Strategy

Zuckerberg will likely argue that:

-

Causation is unclear: Maybe teens with depression use Instagram more, rather than Instagram causing depression. Correlation, not causation.

-

Social media is one factor among many: Genetics, environment, school stress, family dynamics—lots of things affect teen mental health. Why is Instagram uniquely responsible?

-

User choice: Teens choose to use these platforms. Parents can restrict access. No one is forcing them.

-

The company tried to help: Meta did add parental controls. Meta did add mental health resources. Meta did remove like counts for a period.

The problem with these defenses is the internal documents. When you have emails showing executives discussing how to increase teen engagement despite knowing the risks, claiming you didn't know or couldn't control it becomes unconvincing.

What His Testimony Actually Means

Here's what often doesn't get discussed: his testimony probably won't matter as much as the documents and the other witnesses.

Juries don't trust CEOs in these cases. They're assumed to have financial motivations to downplay harm. But former employees testifying about what they were told to do, or researchers explaining what the internal studies showed, or therapists explaining the pattern of harm they see in teen patients—that moves juries.

Zuckerberg's testimony matters mostly if he says something that contradicts documents, which then gets replayed to the jury as proof of deception.

The TikTok Case: A Different Kind of Threat

Why TikTok Is the Most Vulnerable

While Meta faces lawsuits focused on specific harms (eating disorders, body image, self-harm), TikTok faces something more fundamental: the algorithm is so powerful and so opaque that it's almost impossible to defend.

With Instagram, you see your friends' posts and content you choose to follow. There's some agency. The algorithm enhances it, but the basic structure is user-directed.

With TikTok's For You page, you have virtually no control. The algorithm decides what you see. You have no followers. You don't choose the content source. TikTok's algorithm just decides "here's what you're watching for the next three hours."

This creates a unique vulnerability: TikTok has designed the entire platform around algorithmic control of content. Everything is optimization. And that optimization is explicitly for engagement, not user welfare.

Internal documents show TikTok executives understood that their algorithm could drive harmful behavior. One document discussed how the platform's "endless scroll" was specifically designed to maximize watch time, with explicit discussion of the mental health tradeoffs.

The Transnational Angle

TikTok also faces a complication that Meta doesn't: it's a Chinese company. That creates extra legal pressure and political pressure.

Some argue that lawsuits against TikTok are politically motivated because it's a foreign competitor. Others argue that foreign ownership actually makes the case stronger—why should we let a company from another country cause mental health harm to American teenagers?

This political dimension could actually help plaintiffs. If juries believe that TikTok deliberately exploited American teens for engagement and profit, with less concern for local consequences, the emotional resonance shifts.

Lawyers for the families are positioning this as: "Would you accept this product design if it was your kid?"

YouTube and Google: The Overlooked Defendant

Why YouTube Is in These Cases

Google often escapes the worst criticism of social media companies because it's framed as a "search engine" or "video platform" rather than a social network. But YouTube functions exactly like a social network for young teens.

It has recommendations. It has watch history. It has the same engagement optimization. And it owns nearly the entire market for video consumption by teens.

Internal evidence shows YouTube researchers knew that the recommendation algorithm was pushing extreme content to teens—conspiracy theories, eating disorder advice, self-harm tutorials, dangerous challenges.

Why? Because that content drives engagement. And engagement drives watch time. And watch time drives ads. And ads drive profit.

There was a moment—around 2017-2018—when YouTube faced massive criticism for recommending conspiracy theories and radicalization content. They made some changes. But structural changes that would reduce engagement? No.

Instead, they implemented cosmetic changes while keeping the fundamental algorithm in place. That signals intent: we value engagement more than safety.

The Scale Problem

YouTube reaches more teens than any other single platform. The recommendation algorithm is more powerful than Instagram's. And the content variety is broader, which means the potential harms are broader.

A teen can go on YouTube to watch a music video and end up in a rabbit hole of self-harm content within 20 minutes, following algorithmic recommendations that the platform actively optimized for engagement.

This scale makes YouTube arguably the most dangerous platform, which is why it's targeted in multiple bellwether cases.

Estimated data shows potential

Snapchat's Specific Vulnerability: Ephemeral Addiction

Why Disappearing Messages Changed the Game

Snapchat created something genuinely new: social media where messages disappear. That seemed like a feature focused on privacy. But internally, Snapchat executives understood it as a feature that created urgency.

If your message disappears, you need to see it immediately. That creates constant checking behavior. It's designed pressure.

Snapchat also pioneered the "Snap Streaks" feature—consecutive days of sending snaps to the same person. The streak number gets displayed publicly. Breaking a streak causes social shame.

This is intentional psychology. The company created a game mechanic designed to create addiction and FOMO. And they specifically targeted teens because teens care about social status more than other age groups.

Internal documents show Snapchat was explicit: "Teens are our target demographic because they're most susceptible to social validation mechanics."

That's not speculation. That's what they documented.

The Growth-at-Any-Cost Problem

Snapchat's entire business model was built on rapid teen acquisition. They didn't have Facebook's diverse advertiser base. They relied almost entirely on user growth and engagement metrics to justify valuation.

That created perverse incentives: make the product as addictive as possible, especially to teens who are easiest to addict, grow at all costs, and worry about consequences later.

Now they're dealing with the "later."

The Science Behind the Harm: What Research Actually Shows

Depression and Anxiety: The Connection

The scientific evidence is robust, not speculative. Over 100 peer-reviewed studies show correlation between heavy social media use and depression and anxiety in teens.

The direction of causation is debated (does depression lead to more use, or does use cause depression?), but the correlation is not.

What's interesting in court cases is that internal company research often shows stronger evidence of causation than public research. When Meta or TikTok funds researchers to understand their products, the researchers often find that the products cause the harm.

But instead of being public, those findings stay internal. They inform design decisions (companies choose to keep harmful features) rather than leading to warnings or redesigns.

The Body Image Trap: Documented and Quantified

The case against Instagram is particularly strong on body image because the evidence is specific.

Meta's own research showed that Instagram's comparison features significantly worsened body image for teen girls. Some of the numbers: 32% of girls said Instagram made them feel worse about their bodies. For some girls, it made the problem "significantly worse."

Over time, this correlates with increases in eating disorders, especially among girls aged 13-17.

Instagram's design is literally predicated on visual comparison. Post photos. Get feedback. See other people's photos. Compare. Feel inadequate or validated. Repeat.

For a girl developing her identity and social awareness, this is constant psychological pressure to maintain a curated image that meets impossible standards.

That's not a bug in Instagram. That's the core feature.

Sleep Disruption: The Underrated Harm

One of the least discussed but most documented harms is sleep disruption.

Notifications interrupt sleep. Blue light affects circadian rhythms. And the psychological activation of social media—the checking, the anxiety, the FOMO—prevents the deactivation needed for sleep.

For teens, sleep is critical for development, mood, and cognition. Chronic sleep deprivation from social media use compounds other mental health issues.

Internal research at multiple companies showed they understood this. Notifications at night. Features designed to trigger nighttime checking. Algorithms that know you're most engaged late at night.

Companies could implement do-not-disturb features. They could limit nighttime notifications. They could redesign features to reduce nighttime engagement.

They don't, because nights are peak engagement times.

Legal Theories: How Plaintiffs Are Building the Case

Unfair and Deceptive Practices

One major legal theory is that platforms engaged in unfair and deceptive practices. They marketed themselves as safe social platforms while knowingly designing them to harm teens.

This is important because it doesn't require proving direct causation. You just need to show that the company made claims ("safe for kids") while knowing those claims were false.

Every major platform has marketed parental controls and safety features. Instagram has the "teen accounts" option. TikTok has family pairing. YouTube has restricted mode.

But if the entire base product is designed to be addictive and harmful, are parental controls really a solution? Or are they a veneer of safety that allows the company to claim responsibility while continuing harmful practices?

Courts are increasingly finding this deceptive—claiming safety while designing for engagement regardless of the consequences.

Product Defect Theory

Another theory treats the platforms like defective products. A car with faulty brakes is defective. An Instagram algorithm that predictably harms teen girls is similarly defective.

The company knew or should have known about the defect. They had the ability to fix it. They chose not to. That's liability.

This theory is powerful because it doesn't require proving intent. Even if Zuckerberg claims he didn't know, the company should have known. The company had the research capability. They chose not to investigate, or they investigated and buried the results.

Either way, that's negligence, and negligence creates liability.

Negligent Infliction of Emotional Distress

This is an older legal theory but applies well to social media. Companies owed a duty of care to users. They breached that duty by designing products they knew would cause emotional harm. That harm was foreseeable. Teens suffered. Liability follows.

The challenge is proving that the company's specific actions caused the specific harm to a specific person. But with internal research showing widespread knowledge of risks, that becomes easier.

Consumer Protection Violations

Most states have consumer protection statutes that allow people to sue for unfair or deceptive business practices. These are often easier to prove than traditional negligence because they don't require proving harm, just unfair practice.

If a company markets a product as safe while knowing it's dangerous, that's a violation. That's enough for liability, and in some states, for punitive damages (damages designed to punish, not just compensate).

Punitive damages would be devastating to tech companies because they're not capped by insurance and they scale with the company's wealth.

Estimated data shows that social media use is linked to various mental health issues among teens, with body image issues affecting 32% of girls.

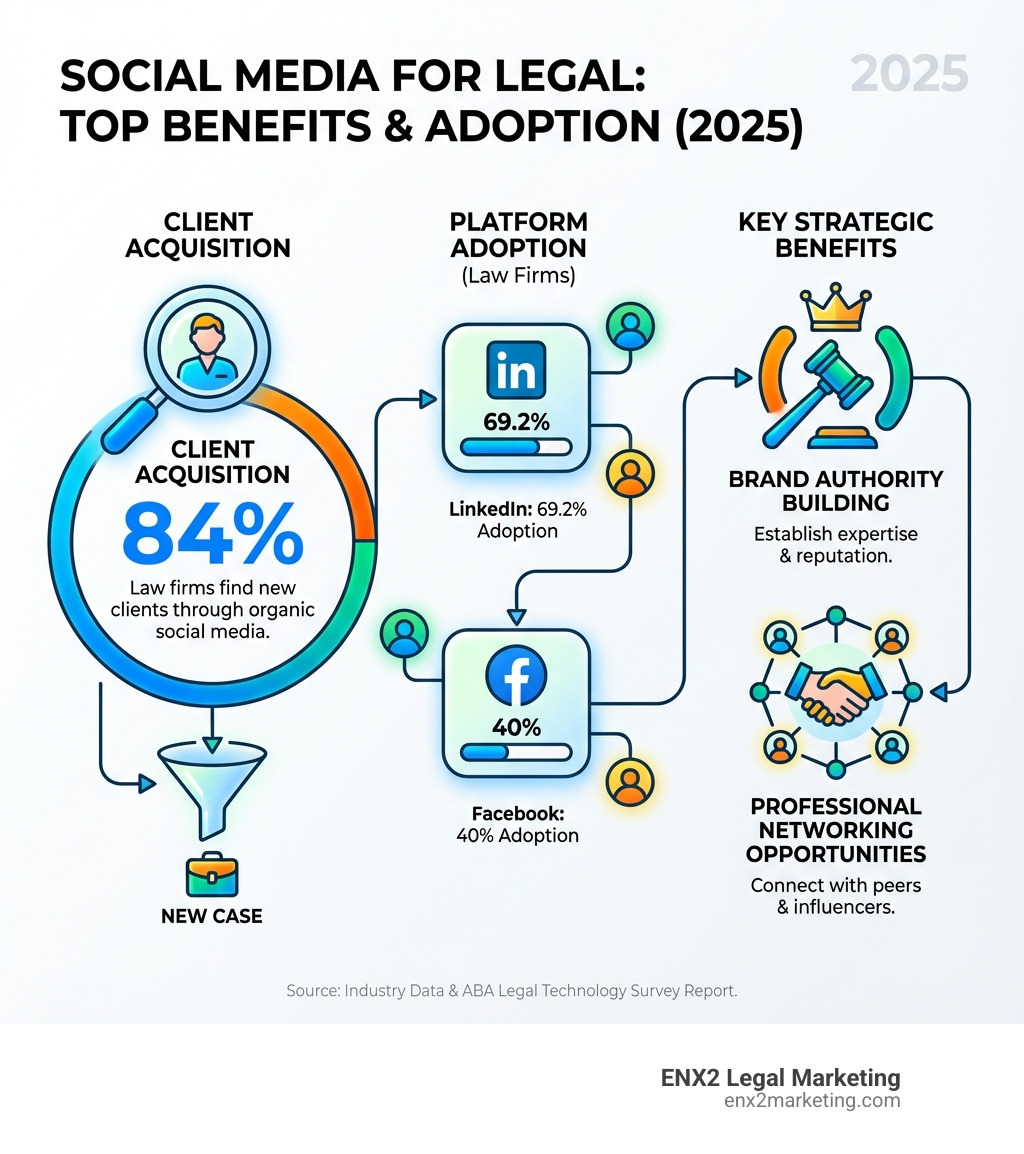

School District Cases: A Different Angle

Why Schools Are Suing

Separate from the individual family cases, schools and school districts are suing. Why? Because social media harms are affecting their business.

Increased mental health crises mean hiring more counselors. Disruptions in class because students are on their phones. Increased discipline issues. Cyberbullying incidents they have to manage.

Schools are economically harmed by the externalities of social media. And they have data to prove it.

Since social media became ubiquitous in schools, anxiety and depression rates have increased. Self-harm reporting is up. Suicide rates among teens are up. And schools have to deal with all of it.

Why should schools bear the cost of social media companies' addiction mechanics? That's the argument.

State Attorneys General Cases

State AGs represent the public interest. Multiple states have filed cases arguing that social media companies violated consumer protection laws and created a public health emergency.

This framing is important: it's not just about individual victims. It's about a systemic threat to teen development and public health.

If states prevail, they can seek damages, injunctions (court orders to change business practices), and regulatory authority over how platforms operate.

State AG cases often get more media attention and carry more weight than individual cases because they represent the government itself.

The Defense: What Tech Companies Are Arguing

Causation Is Unclear

Tech companies' primary argument is that correlation doesn't equal causation. Yes, there's a correlation between social media use and depression. But that could be because depressed teens use social media more to escape, not because social media causes depression.

This is actually true in some cases. But it's not a complete defense when you have internal evidence that companies understood and discussed the causal mechanism.

If you have an email saying "our algorithm causes depression but we're keeping it because engagement is up," then arguing causation is unclear is unconvincing.

Social Media Is One Factor Among Many

Tech companies argue that many factors affect teen mental health: genetics, family dysfunction, school stress, bullying, economic anxiety.

Why are we blaming social media specifically?

The answer is because companies designed their products to maximize these harms. They're not passive observers of teen mental health. They're active, intentional designers of engagement mechanics.

Bullying exists in schools too, but if a school knew bullying was happening and designed features to amplify it because it created engagement, that would be actionable.

Social media companies did exactly that with bullying. They recommend accounts that might follow you, creating social competition. They make likes and comments visible, creating public judgement. They create features like stories that create ephemeral social pressure.

It's not that bullying exists. It's that they designed features to amplify it.

Parents Have Responsibility

Tech companies argue that parents have responsibility for monitoring their kids' use. If social media harms teens, it's because parents aren't setting boundaries.

This is true in some cases. But it's not a complete defense when the company designed the product specifically to be hard for parents to control.

You can't put parental controls on TikTok's algorithm. You can't tell it not to show harmful content to your kid. As a parent, you have the choice: allow TikTok or don't allow TikTok.

You can't make TikTok safer. Only TikTok can do that. Placing responsibility on parents for something they literally cannot control is insufficient defense.

We Provide Mental Health Resources

Tech companies often claim they take mental health seriously. Meta provides links to crisis resources. TikTok added mental health resources. YouTube has content policies against self-harm material.

The problem is that providing a link to crisis resources doesn't reverse the harm the algorithm caused. Nor does it excuse the design of the product in the first place.

It's like a tobacco company saying "we provide cancer support resources, so tobacco isn't harmful." Resources don't undo the business model.

What Happens If Plaintiffs Win: The Cascade Effect

Immediate Impact: Liability and Damages

If even one bellwether case results in plaintiff victory, the damages could be enormous.

Imagine a jury awards

And that's a conservative estimate. Some cases involve multiple plaintiffs. Some involve class actions (groups of similar cases consolidated). Damages could be multiples higher.

For Meta and Google, that's manageable. They have $100+ billion in cash. But it sets a precedent and opens the floodgates.

Regulatory Backlash: The Real Threat

What matters more than damages is regulatory response. If courts determine that social media platforms are harming teens, expect regulators to respond.

The FTC could ban algorithmic amplification for teen users. Require consent before using engagement features with minors. Impose data minimization rules (collect less data about teens). Require transparency about engagement mechanics.

State legislatures could follow California's lead with strict teen protection laws. Some states are already proposing bills that would require social media companies to verify age and get parental consent for under-18s.

International regulators (EU, UK, others) are watching. Europe's Digital Services Act already requires protection of minors. Successful U.S. litigation could accelerate global regulation.

The result: a completely different business model. Platforms might have to reduce engagement features for teens. That means less data collection, less targeting, less optimization. That means lower profit margins.

That's the real incentive for settlement. Not the damages. The threat of being forced to fundamentally change the business model.

Product Redesign: The Potential

If platforms are forced to redesign, what might that look like?

For engagement metrics: No public like counts. No follower counts. No visible social comparison numbers. Just private feedback that you've been seen.

For algorithmic amplification: No infinite scroll. No endless recommendation algorithms. Just chronological feeds where you see what you chose to follow. You have to actively seek more.

For notifications: No FOMO-inducing notifications. No red badges. No artificial urgency. Maybe a weekly digest instead of real-time pings.

For data collection: Limited data about teen users. No behavioral profiling. No targeted advertising to minors. No collecting data about what they look at, what they're interested in, their vulnerabilities.

For time limits: Suggested breaks. Daily usage limits. Friction designed to discourage excessive use rather than maximize it.

These aren't technically impossible. They're business choices. Companies could build social networks this way. They just wouldn't be as profitable.

Instagram has the highest reported negative impact on teen girls' body image and eating concerns, with TikTok, YouTube, and Snapchat also showing significant mental health correlations. Estimated data based on research insights.

The Global Implications: How U.S. Trials Affect the World

Europe's Digital Services Act: Already Tougher

Europe is ahead of the U.S. on regulating teen exposure to social media. The Digital Services Act requires specific protections for minors and can result in massive fines (up to 6% of global revenue).

If U.S. courts establish that social media harms teens, European regulators will use that as justification for stricter enforcement.

For platforms, having to comply with two different regulatory regimes (U.S. litigation + EU DSA) means de facto global changes.

China's Approach: The Contrast

Interestingly, China restricts teen access to social media differently. TikTok (called Douyin in China) has time limits for minors. It's designed differently for under-18s. The algorithm doesn't push endless content. Daily usage is capped.

TikTok built a safer product for Chinese teens while building an addiction machine for American teens. Why the difference? Chinese regulation.

This proves that designing for teen safety is possible. Tech companies choose not to because regulation hasn't forced them.

If U.S. and European regulation catches up to China's approach, expect platforms to finally implement safety-first design everywhere.

What We Actually Know About Teen Use: The Data

Daily Usage Patterns

The average teen spends roughly 4-5 hours per day on social media and video platforms. For some, it's over 7-8 hours.

Compare that to school (6-7 hours) and sleep (8 hours ideally). Social media is now the dominant activity in teen life.

But not all time is equal. The quality of engagement matters. Passive scrolling has different effects than active interaction. Algorithmic content has different effects than curated content.

Companies have optimized for passive, algorithmic, engagement-maximizing use. That's the problem.

The Mental Health Correlation Data

Meta's own research (later leaked) showed:

- 32% of teen girls said Instagram made them feel worse about their bodies

- 29% of teen girls reported that Instagram worsened their eating concerns

- Instagram's effects were most severe for girls already struggling with body image

But you probably won't see this data in Meta's public health communications. It stays internal.

Similarly, researchers have found correlations between TikTok use and anxiety, YouTube recommendation rabbit holes and radicalization, Snapchat use and FOMO.

The consistent pattern: more use, more mental health degradation. Especially for teens already vulnerable.

Age and Vulnerability

Teens aged 13-15 are most vulnerable. Their brains are developing. Their identities are forming. Their self-esteem is fragile. Social validation feels existential.

Platforms knowingly target this age group because they're easiest to addict and most likely to adopt as lifetime users.

That's not an accident. It's a business strategy. And it's directly actionable in court.

The Timeline: When Will These Cases Actually Resolve?

2025: Bellwether Trials Begin

Multiple cases are going to trial in early 2025. These will take months. Jury selection alone takes weeks. Then testimony from plaintiffs, families, experts, executives, and company witnesses.

Expect trials to last 3-6 months each. Verdicts could come by late 2025 or early 2026.

2026-2027: Appeals and Settlements

If plaintiffs win, companies will appeal. If companies win, plaintiffs will appeal. Appeals could take years.

But most cases won't reach appeal. They'll settle. Settlements happen faster and have less publicity.

Expect settlement discussions to intensify in 2026 as the outcomes of bellwether cases become clearer. Companies will calculate: is it cheaper to pay settlements or risk verdicts and regulation?

2027+: Systemic Changes

Whatever happens in individual cases, the regulatory pressure will escalate.

If courts find platforms liable, regulators move faster. If courts protect platforms, regulatory backlash accelerates (legislatures saying, "fine, we'll do this ourselves").

Either way, expect meaningful regulation by 2027-2028.

Estimated data shows settlements ranging from

What Teens Can Do Now: The Practical Reality

It's Not Just About Time Limits

Parents often think the solution is limiting screen time. Use less TikTok, and you'll be fine.

But the problem isn't total usage. It's the design of the experience. Even moderate use of an intentionally addictive product can cause harm, especially if you're already vulnerable.

The real solutions require platform design changes that teens and parents can't implement themselves:

- Stop using engagement metrics as public feedback

- Stop algorithmic recommendation to strangers

- Stop notifications designed to create urgency

- Stop data collection for behavioral profiling

Teens can take some actions: turn off notifications, use grayscale mode to make phones less appealing, set screen time limits, follow accounts manually rather than algorithm. But these are band-aids on a fundamentally harmful design.

The Reality: Regulation Is the Only Solution

Most teen experts agree that individual behavior change won't solve this. The design is too sophisticated, the algorithms too powerful, the engagement mechanics too intentional.

What's needed is regulation that forces platforms to change their designs. Until that happens, the default is: the product is designed to harm you, and you have to resist a multi-billion dollar company's engineering trying to keep you engaged.

That's an unfair fight.

The Broader Context: Why This Moment Matters

Accountability Has Been Missing

For 20 years, tech companies have operated largely without consequences. They launched products. They optimized for profit. They ignored harm. When criticism emerged, they hired lobbyists and fought regulation.

Social media escaped the kind of regulatory scrutiny that other industries face. Pharmaceutical companies can't do what social media companies do. Food companies can't target kids with addictive products. Tobacco had to fight for decades before being held accountable.

But social media got a pass. Framed as "innovation" and "free speech," they were allowed to build addiction machines and market them to kids.

These trials represent the first real moment of potential accountability.

The Business Model Problem

Here's the deepest issue: the business model itself is the problem.

Billboards don't need to be addictive. Newspapers don't need engagement-maximization algorithms. Traditional media didn't optimize for keeping you away from your family and responsibilities.

But ad-driven social platforms do. Because advertising revenue scales with engagement. More engagement = more time = more ads = more money.

There's no incentive to make the product healthy. The incentive is always to make it more engaging, more addictive, more profitable.

Until that business model changes—either through regulation or market disruption—the behavior won't change.

That's why these trials matter. They might finally force the business model to shift.

What Happens If Companies Lose: The Realistic Scenario

Settlement Is Most Likely

Outright victory for plaintiffs in every case is unlikely. Tech companies have unlimited legal resources. They'll fight hard.

But settlement is probable. Once the costs of litigation + potential damages + regulatory risk outweigh the benefit of the current business model, companies will negotiate.

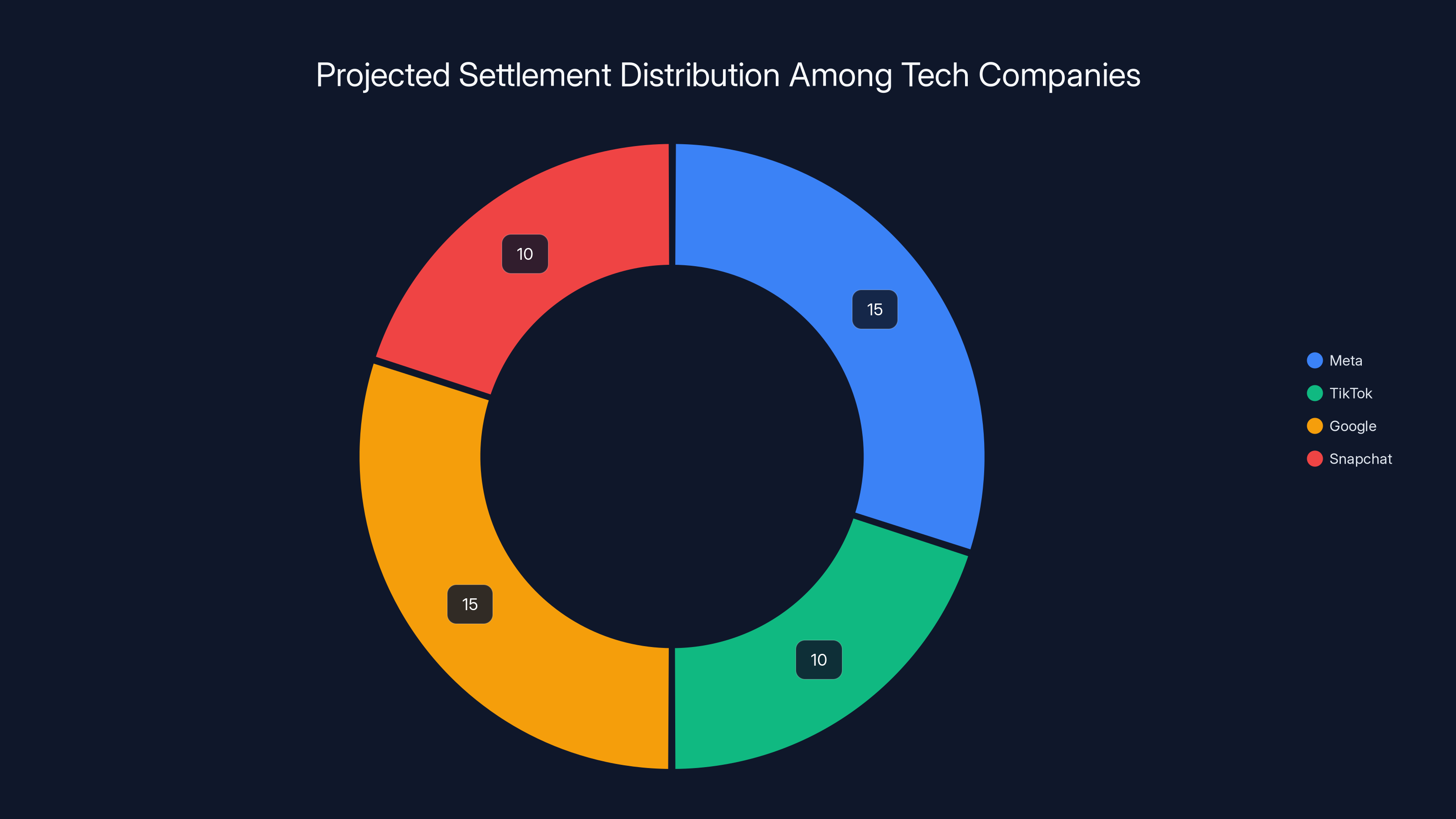

Expect settlements in the $10-50 billion range across all cases (shared among Meta, TikTok, Google, Snapchat).

That's significant but not catastrophic for these companies. It's more about sending a message: this behavior has consequences.

Design Changes: The Real Impact

What matters more than money is forced design changes.

Imagine a court ruling that says: "Platforms must not use engagement metrics as public feedback for teen users." That means no likes, no follower counts, no public comments visible to others for anyone under 18.

That sounds small. It would devastate engagement. Platforms would lose 30-40% of usage time overnight.

That's why companies fight so hard. Not the money. The business model threat.

But if courts or regulators force it, companies will comply. And they'll figure out alternative business models (subscription? less targeted ads? different products?).

The Precedent

The most important outcome is precedent. Once one court finds a platform liable for teen harm, it opens the door for thousands of similar cases.

Companies can't afford to lose and set that precedent. So they'll settle, do some things, and try to move on.

But the legal principle will be established: platforms have liability for harm caused by their design choices.

Expert Opinions: What Researchers Are Saying

Jonathan Haidt on the Phone Problem

Psychologist Jonathan Haidt has argued that the smartphone + social media combination represents an unprecedented experiment in adolescent psychology.

Teens are navigating identity development under constant public scrutiny, with algorithmic amplification of comparison and judgment.

In previous generations, teens could retreat from social pressure. They came home. They had privacy. They had time to develop resilience.

Now? The social stage is always on. The judgment is always visible. The comparison is constant.

That changes development in ways we're still discovering.

Jean Twenge's Data Analysis

Psychologist Jean Twenge has documented the correlation between smartphone adoption (2010-2015) and mental health crises in teens.

The timeline is striking: as phone penetration went from 35% to 85% in teens, depression increased 42%, anxiety increased 48%, self-harm increased 65%.

Causation isn't proven by that data, but the timing is too perfect to ignore.

Tristan Harris on Persuasive Technology

Tristan Harris, who worked at Google on attention and user experience, has become a vocal critic of persuasive technology.

He argues that tech companies have the ability to redesign for user wellbeing instead of engagement. They choose not to because engagement = profit.

The choice is intentional. The harm is predictable. That's where liability lies.

The Settlement Question: Will These Cases Actually Settle?

Why Settlement Makes Sense

For tech companies, the calculus is:

- Cost of defending trials: $100-500 million (legal fees, executive time, disruption)

- Risk of losing: potential for $20-100 billion in damages across all cases

- Cost of regulation if they lose: even higher (forced business model changes)

Compare that to settling for $5-10 billion in damages but keeping the business model mostly intact.

Settlement makes financial sense.

Why They'll Resist

But companies also know that settlement signals admission of guilt. It gives regulators ammunition.

If Meta settles for $10 billion for designing Instagram to harm teen girls, that's essentially admission that the design was harmful. That gives the FTC or Congress justification for strict regulation.

So companies are stuck: settle and admit guilt (prompting regulation) or fight and risk massive damages (which also prompts regulation).

Either way, they lose. So they'll fight to delay, hoping the political situation changes or the science becomes uncertain.

But delay just means more cases are filed, more damages accumulate, and the liability grows.

At some point, settlement becomes inevitable.

What You Should Know Going Forward

These Cases Are Real

This isn't speculation or political theater. These are serious legal cases with solid evidence and reasonable arguments.

Juries might not find completely in favor of plaintiffs, but they'll likely find something. Some liability. Some causation. Some negligence.

That's enough to shift the landscape.

The Outcome Affects Your Kids (or Future Kids)

Whether you have children or not, the outcome of these cases will affect the social media platforms that exist in 5-10 years.

If platforms are forced to redesign for safety, they'll be different. Better, arguably, but also less engaging and less profitable.

If platforms maintain the current model, the mental health crisis in teens continues.

There's no neutral outcome here. One way or another, something changes.

The Business Model Is Incompatible with Teen Wellbeing

This is the deepest insight: advertising-based engagement optimization is fundamentally incompatible with teen psychological health.

You can't simultaneously maximize engagement and minimize harm. Engagement and harm are correlated. The more a product is designed to addict, the more it will harm vulnerable people.

That's not a design bug. That's the business model working as intended.

Until that changes—either through regulation or market pressure—the behavior won't fundamentally shift.

Conclusion: The Stakes and What's Next

Lori Schott traveled from Eastern Colorado to that LA courthouse for a reason. Her daughter died. And she needed someone to answer for what happened.

For decades, that answer was unavailable. Tech companies hid behind Section 230. They framed criticism as moral panic. They pointed to parental responsibility while optimizing for teen addiction.

But this moment is different. The evidence is documented. Internal emails are released. Experts are testifying. And juries will decide whether platforms have liability.

Whatever the verdict, the conversation is shifting. Social media is no longer seen as neutral innovation. It's recognized as designed influence, with real consequences.

The question isn't whether these cases will affect the tech industry. They will. The question is how much.

Small damages and cosmetic changes? Or fundamental redesign of how platforms operate?

The trials will answer that. And that answer will shape the digital world teens inherit.

There's a real possibility—for the first time—that tech companies will be held accountable. Not just in courts, but in regulation, in business practice, in product design.

That's what makes this moment significant. Not just for the families suing. But for every teenager struggling with anxiety about their appearance, their social status, their constant connection to a system designed to exploit their vulnerabilities.

Their voice finally has a channel. A courtroom. A jury. A judge who might finally say: this is unacceptable.

And that changes everything.

FAQ

What exactly are the social media lawsuits about?

These lawsuits accuse major social media platforms—Meta (Facebook and Instagram), TikTok, Snapchat, and YouTube—of deliberately designing their products to be addictive and psychologically harmful to teens. Plaintiffs argue that companies knew their platforms caused depression, anxiety, eating disorders, sleep problems, and self-harm, but continued using engagement-maximizing designs because they drove profits through advertising revenue. The cases are being brought by families of harmed teens, school districts, and state attorneys general. Unlike earlier legal challenges, these cases survived dismissal by focusing on platform design choices rather than user-generated content, overcoming the Section 230 legal shield that previously protected companies from liability.

How did these cases overcome Section 230 protection?

Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act historically protected platforms from liability for user-generated content. However, courts in these cases recognized an important distinction: the lawsuits don't claim that other users' posts harmed teens. Instead, they claim that the platforms' own design choices—algorithms, recommendation systems, notification features, engagement metrics, infinite scroll—caused the harm. Since these design features are the company's responsibility, not users', they fall outside Section 230's protection. This legal distinction was the breakthrough that allowed these cases to proceed to trial rather than being dismissed outright, which is why legal experts consider these cases historically significant.

What internal documents prove that companies knew about the harm?

Released discovery documents show that executives and engineers at major platforms explicitly discussed the psychological effects of their products on teens. Meta's internal research indicated that Instagram worsened body image for 32% of teenage girls and eating concerns for 29% of them. TikTok engineers documented how the "endless scroll" was designed to maximize watch time despite understanding mental health tradeoffs. Snapchat executives discussed targeting teens specifically because they're most susceptible to social validation mechanics. YouTube researchers knew their recommendation algorithm pushed extreme content to teens. These documents prove that company awareness wasn't accidental—executives actively discussed these harms in internal communications while choosing to continue or expand engagement features anyway. That documented knowledge is crucial for proving intentional misconduct in court.

Why are school districts suing social media companies?

School districts argue they're bearing the costs of social media's mental health consequences without receiving any benefit. Since teens have become heavily engaged with social media, schools have seen increases in mental health crises, self-harm incidents, cyberbullying cases, and student disruptions. Schools are forced to hire more counselors, deal with behavioral issues, and manage crisis situations—all externalities caused by platforms they don't control. By suing, schools argue that social media companies should bear the financial responsibility for the harm their products cause, rather than transferring that cost to education systems and taxpayers. This angle is important because it frames the issue not just as individual harm, but as a public health and public cost problem.

What is a bellwether case and why do these trials matter?

A bellwether case is a test case whose outcome signals how similar pending cases will likely be resolved. Currently, there are roughly 400 social media cases pending against various platforms. Most of these are waiting to see how the first bellwether trials turn out before proceeding. If families win these initial cases, it signals that juries find platforms liable for teen harm, which will likely result in a cascade of additional cases and significant damages. If platforms win, it signals the opposite, and most pending cases may be dropped or quietly settled. This is why these first trials are so crucial—they're not just about one family's case; they're the canary in the coal mine for the entire litigation landscape against social media companies.

What does it mean that Mark Zuckerberg is testifying?

Mark Zuckerberg, as Meta CEO, is being called to testify about what he knew regarding Instagram's effects on teen mental health and body image, particularly for teenage girls. His testimony will likely focus on whether he read internal research showing harm, what he did (or didn't do) about it, and why Meta chose to continue features that the company's own research showed were damaging. If his testimony contradicts the internal documents, it destroys his credibility with the jury. If he admits to knowing about the harm but continuing anyway, it proves intentional misconduct. His testimony is pivotal because it goes to the question of company intent and knowledge—did executives knowingly create and maintain harmful products? That's a major factor in determining liability and damages.

What is the algorithm's role in causing teen mental health harm?

Algorithms are the engine of engagement-based harm. Rather than showing you what you chose to follow (like traditional social networks), modern algorithms decide what you see based on what will keep you engaged longest. For teens, this means the algorithm learns what makes them anxious, insecure, or emotionally activated—and shows more of that content. Instagram's algorithm learns that body comparison content keeps girls scrolling, so it shows more. TikTok's algorithm learns that dramatic, extreme, or anxiety-inducing videos drive engagement, so it recommends more. YouTube's algorithm learned that conspiracy theories and radicalization content drove watch time, so it recommended them. The algorithms are optimized for engagement, not teen wellbeing. And engagement correlates with anxiety, depression, and self-harm. That's not coincidental—it's the business model working as designed.

What happens if the platforms lose these cases?

If plaintiffs win even one bellwether case, the implications cascade quickly. First, damages could be substantial—potentially billions across all pending cases. More importantly, a plaintiff victory creates legal liability precedent, which will likely result in a flood of additional cases. Regulatory bodies (FTC, state attorneys general, international regulators) would use the verdict as justification for stricter rules. Platforms would face pressure to redesign their products, possibly including removing engagement metrics, eliminating algorithmic amplification for minors, or limiting data collection from teenagers. Many cases would likely settle rather than go to trial once the risk becomes clear. The biggest threat isn't just the money, but the forced redesign of business models that have been profitable because they optimize for addiction. That's why companies are fighting so hard—a loss threatens the fundamental structure of how these platforms operate.

What changes might platforms be forced to make?

Potential court-ordered or regulation-mandated changes could include: removing public like counts and follower counts for teen users (eliminating social comparison metrics), eliminating or dramatically restricting algorithmic recommendation to strangers (moving back toward chronological feeds or curated content), eliminating notifications designed to create urgency or FOMO, implementing aggressive time limits on usage, restricting data collection from minors, requiring parental consent for teen accounts, implementing age verification, removing engagement-optimization tactics like infinite scroll, and prohibiting targeted advertising to minors. Some of these changes would be relatively minor (cosmetic), while others would fundamentally alter how these platforms function and how profitable they can be. Companies will resist the more disruptive changes because they directly threaten revenue models.

How long will these cases actually take?

Bellwether trials are beginning in 2025 and will likely last 3-6 months each due to complex discovery, expert testimony, and multiple witnesses. Verdicts could come by late 2025 or early 2026. Appeals, if either side contests the verdict, could extend the timeline years longer. However, most cases will likely settle before appeals, which could accelerate outcomes. The cumulative timeline for all related cases to resolve could be 5-10 years, though regulatory changes (which often move faster than litigation) could begin within 2-3 years if courts find against the platforms. So expect trials to dominate headlines through 2025-2026, settlements in 2026-2027, and regulatory responses in 2027-2028.

Can teens do anything to protect themselves right now?

Yes, several tactics can help minimize harm: turn off all notifications to remove the artificial urgency trigger, use grayscale mode to make phones less visually appealing, manually follow accounts rather than relying on algorithm recommendations, set strict screen time limits, avoid checking social media before bed (it disrupts sleep), and be aware that the system is designed to exploit insecurities—so recognizing that can reduce the impact. However, these are band-aid solutions to a fundamentally harmful design. The real solution requires platform redesign or regulation that forces platforms to change. Individual behavior change can't overcome a multi-billion dollar company's engineering optimized to keep you engaged. That's why systemic change through these lawsuits and potential regulation is so important—it's the only way to fix the underlying problem rather than just asking teens to resist more aggressively.

Key Takeaways

- These trials represent the first realistic opportunity to hold social media platforms legally accountable for designed harm to teens, as cases overcame Section 230 protections by focusing on product design rather than user-generated content.

- Internal documents prove executives at Meta, TikTok, Snapchat, and YouTube explicitly discussed teen engagement mechanics and known mental health harms while choosing to continue and amplify those features.

- The bellwether strategy means outcomes of these early trials will determine whether 400+ pending cases proceed, potentially creating $20-100 billion in total liability and forcing platform redesigns.

- Evidence shows 32% of teen girls report Instagram worsening their body image, with similar documented harms for anxiety, sleep disruption, and algorithmic radicalization across platforms.

- A plaintiff victory would likely trigger regulatory backlash and forced design changes (removing engagement metrics, algorithmic amplification limits, data collection restrictions) that threaten fundamental platform business models.

Related Articles

- Meta's Parental Supervision Study: What Research Shows About Teen Social Media Addiction [2025]

- Meta's Fight Against Social Media Addiction Claims in Court [2025]

- Meta and YouTube Addiction Lawsuit: What's at Stake [2025]

- Social Media Safety Ratings System: Meta, TikTok, Snap Guide [2025]

- EU Investigation into Shein's Addictive Design & Illegal Products [2025]

- Social Media Moderation Crisis: How Fast Growth Breaks Safety [2025]

![Social Media Giants Face Historic Trials Over Teen Addiction & Mental Health [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/social-media-giants-face-historic-trials-over-teen-addiction/image-1-1771450653341.jpg)