Meta's Facial Recognition Smart Glasses: The Privacy Reckoning [2025]

Last May, Meta's internal memo landed on The New York Times' desk like a loaded gun. The message was blunt, calculated, and honestly pretty damning: launch facial recognition on smart glasses "during a dynamic political environment where many civil society groups that we would expect to attack us would have their resources focused on other concerns."

Let that sink in for a second. Meta wasn't just planning to roll out surveillance tech. They were literally timing it to avoid accountability. To slip it past watchdogs while everyone's looking the other way.

The feature? Something called "Name Tag." Sounds innocent enough, right? Wrong.

What we're really talking about is turning everyday eyewear into a surveillance device that can identify people on the street using Meta's AI, cross-reference them against social networks, and pull up personal details. For some people, that's genuinely helpful. For most of us, it's a dystopian nightmare we didn't ask for.

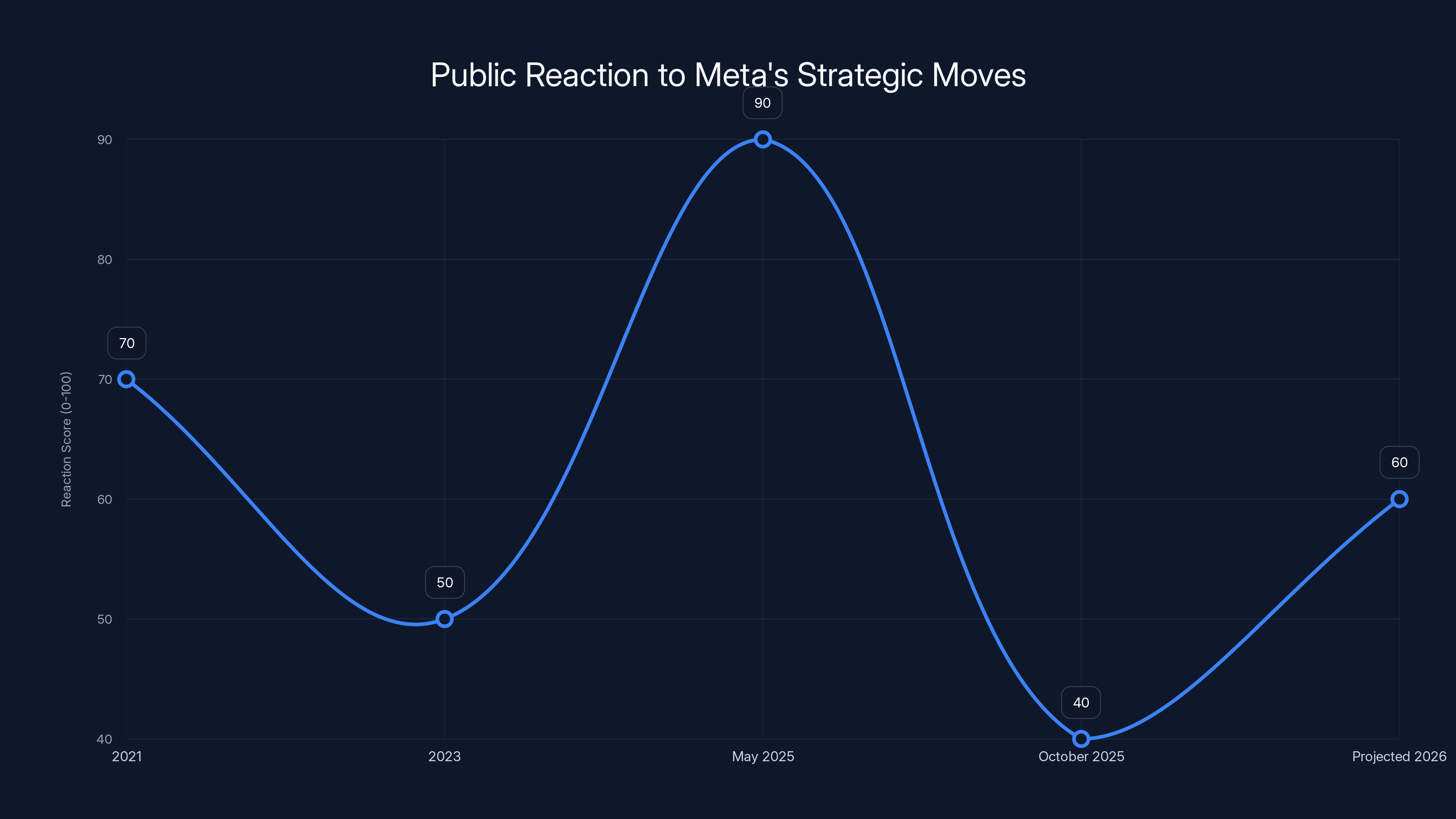

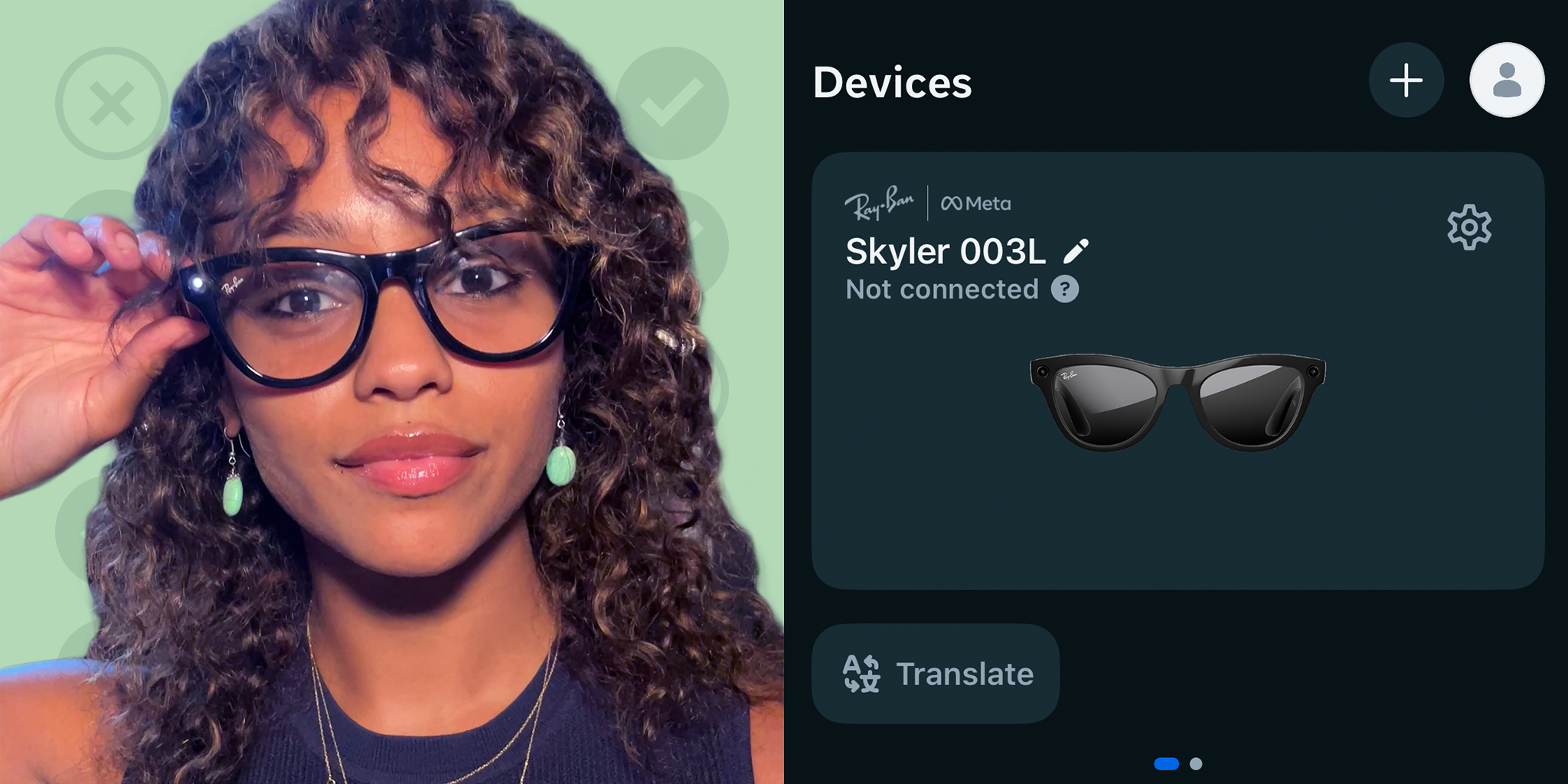

Here's the thing: this isn't some distant sci-fi scenario. Meta's been shipping Ray-Ban smart glasses since 2021. Millions of people already own them. Adding facial recognition isn't a technical leap anymore. It's a business decision. A timing decision. A "let's see if we can get away with it" decision.

This article breaks down everything you need to know about Meta's facial recognition ambitions, why privacy advocates are freaking out, what regulators are actually doing about it, and what happens next. Because spoiler alert: this fight is far from over.

TL; DR

- Meta's internal memo revealed they want to launch facial recognition on Ray-Ban smart glasses during political distraction

- The "Name Tag" feature would identify people in real time using AI, pulling data from Meta's social networks

- Privacy risks are massive: misidentification, unauthorized surveillance, data breaches, and discriminatory targeting become trivial

- No real regulation exists yet: The EU's tightening rules, but the US is still dragging its feet

- This is happening soon: Meta reportedly plans a 2025 launch, with or without public consent

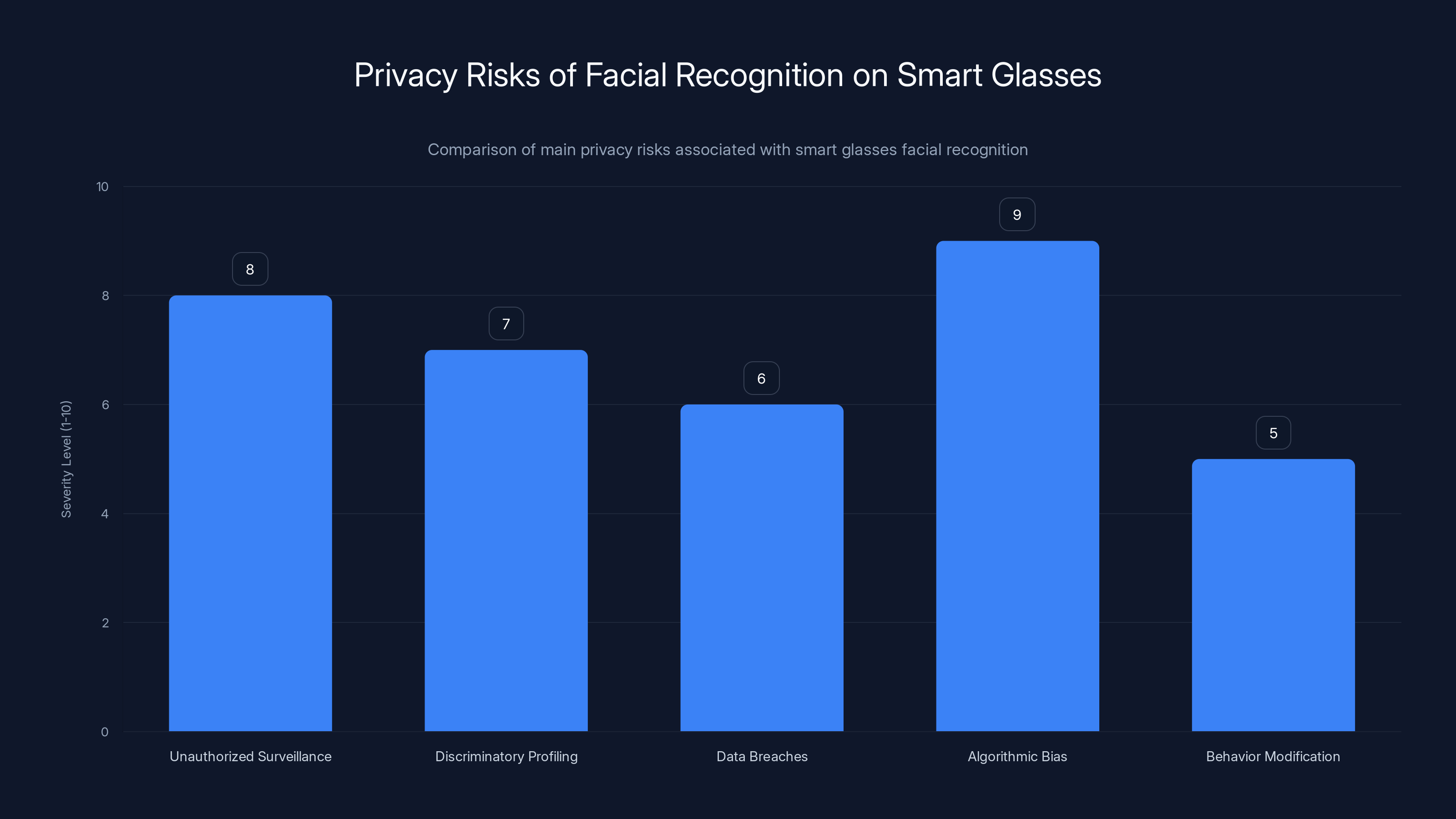

Estimated data shows that algorithmic bias is perceived as the most severe risk, followed by unauthorized surveillance and discriminatory profiling.

The Internal Memo That Changed Everything

The New York Times' October 2025 report should've been the story of the year. Instead, it barely made a dent in the news cycle. Why? Because, well, Meta timed it perfectly.

The memo from May 2025 (reviewed by The Times) doesn't mince words. Meta executives literally wrote down their strategy: wait for a moment when "civil society groups" are too busy with other crises to mount an effective opposition. It's not paranoia to read that as intentional obfuscation. It's the definition of it.

Meta's reasoning has some internal logic, at least from their perspective. Facial recognition on glasses isn't new technology. It's not illegal in most markets. And there are genuine accessibility use cases. But the timing directive? That crosses a line from "launching a feature" to "deliberately evading oversight."

The document describes Meta's plan to first test "Name Tag" at a conference for the blind and low-vision community. That's actually smart from an accessibility standpoint. But then rolling it out to everyone? That's where things get murky. Once the tech is live on millions of devices, the accessibility argument becomes cover for mass surveillance.

What makes this particularly galling is that Meta's already been caught doing this sort of thing before. In 2021, Facebook quietly launched facial recognition features and only pulled them after sustained public pressure. They know the playbook: move fast, acknowledge concerns vaguely, and wait for the outrage cycle to pass.

But here's where it gets interesting. The memo wasn't a leak. Meta didn't have a Snowden moment. The New York Times literally got hold of internal documents and reported on them. Which means Meta should've known this could go public. Yet they proceeded anyway.

That's the confidence of a company that believes the punishment (bad press) will be worth the payoff (unprecedented surveillance infrastructure). Or maybe it's just arrogance. With Meta, it's usually both.

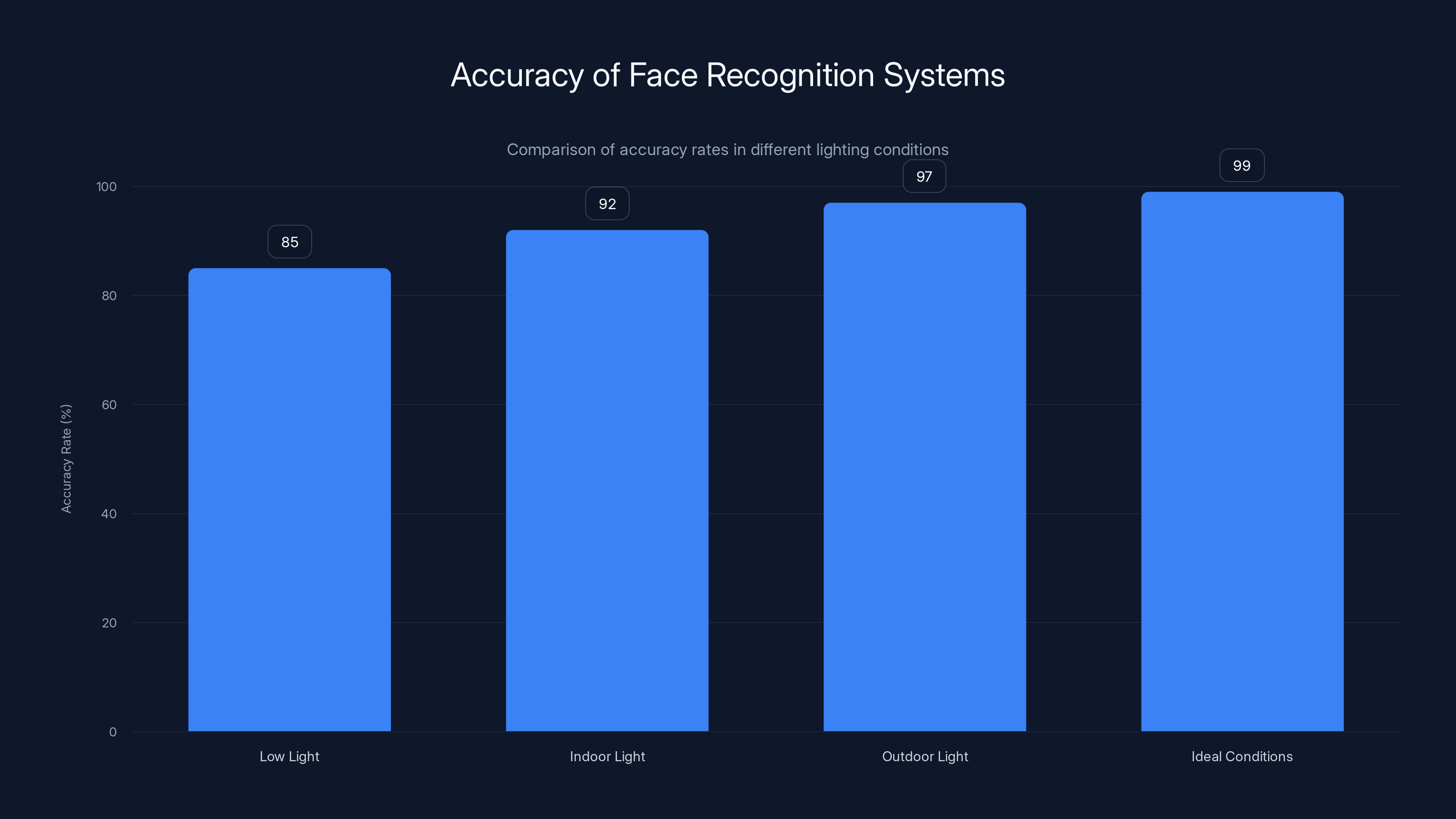

Face recognition systems can achieve up to 99% accuracy under ideal lighting conditions, making them highly effective but also raising privacy concerns.

What "Name Tag" Actually Does (And Why It's Terrifying)

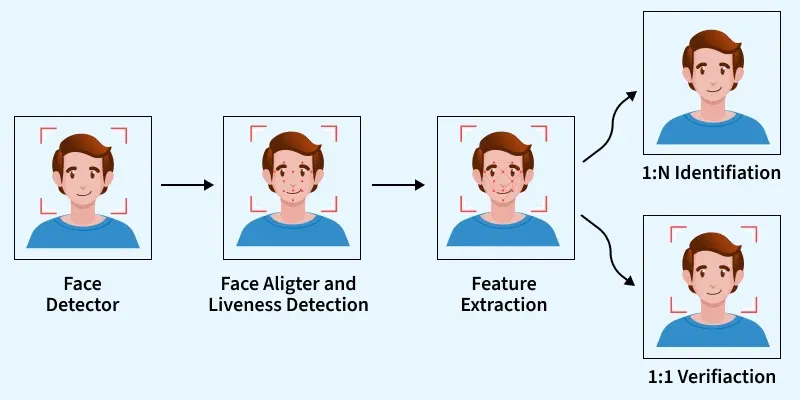

Let's talk specifics. The feature Meta's planning isn't some sci-fi pipe dream. It's... actually pretty straightforward from a technical standpoint.

Here's how it would work: You're wearing Ray-Ban Meta smart glasses. You see someone walking down the street. The glasses' built-in camera captures their face. Meta's AI processes it in real time. Within milliseconds, the system cross-references that face against Meta's databases (Facebook, Instagram, Whats App contact lists). If there's a match, the wearer sees the person's name, mutual friends, and publicly available information overlaid on their vision.

For someone with vision loss? That's genuinely useful. It's accessibility tech that actually works.

For everyone else? It's X-ray vision into other people's social lives, whether they consent or not.

The Technical Mechanics

Meta's using AI models trained on billions of photos from its platforms. The accuracy of these models is genuinely scary good. We're not talking "90% accurate." Modern face recognition systems can identify people with 99%+ accuracy under decent lighting. In public spaces, success rates are phenomenal.

The on-device processing is the clever bit. Instead of sending every image to Meta's servers (which would be obviously creepy), the glasses can do the heavy lifting locally. That makes it faster and raises fewer red flags. Except, well, the data still gets sent eventually. For "improving" the AI. For "personalization." For "better recommendations."

The glasses run on a processor similar to what's in your phone. That's enough to handle facial recognition in real time, especially if Meta's willing to sacrifice some accuracy for speed. Which they absolutely are.

The Social Network Integration

This is where it gets dystopian. Meta doesn't just want to identify faces. They want to pull in all the social context. Who are you connected to? What's in your profile? Who are your friends? What do your photos reveal?

According to The Times' reporting, Meta's exploring two approaches:

-

First-degree connections: Identify people you're already connected to on Meta's platforms. Your friends, family, colleagues.

-

Public accounts: Identify anyone with a public Instagram or Facebook profile, whether you follow them or not.

The second option is the real nightmare. Imagine walking down the street and your glasses telling you the names, profiles, and public information about every person you see who has a public social media presence. That's basically everyone under 40.

Meta's framing this as "helpful." They'd probably say something like, "Users can see who's around them and discover new connections." But what they're really building is a system for mass surveillance so comprehensive that the NSA would've envied it in 2005.

Misidentification and Real-World Harms

Here's the uncomfortable truth: facial recognition isn't perfect. It's very good, but not perfect. And in a system where errors could have real consequences, "very good" isn't good enough.

Misidentification rates vary dramatically by race, gender, and age. Studies consistently show that facial recognition systems are more accurate on white male faces and significantly less accurate on faces of color. This isn't a design flaw. It's a data problem. The training sets were biased.

In a surveillance context, that matters enormously. Imagine a woman wearing Meta glasses misidentifying a stranger as someone she knows. Maybe she starts a conversation thinking she's talking to an old friend. Or worse, imagine a name tag system making dozens of errors per day as she walks through a crowded city.

But the real nightmare is coordinated harm. What happens when Name Tag data gets weaponized? When abusers use it to track people they're trying to harm? When stalkers use it to identify people they're targeting? When racist bad actors use it to find and harass people of color?

Meta's response would probably be, "Users can control their privacy settings." Except they can't really. You can make your account private, but if someone you know hasn't, they can still be identified through your connections.

The Accessibility Argument vs. Mass Surveillance

Here's where the argument gets genuinely complicated. And I mean that. This isn't as simple as "facial recognition bad."

For people who are blind or have low vision, facial recognition on glasses could be legitimately transformative. Imagine not knowing who's talking to you. Imagine trying to navigate social situations when you can't see faces. Now imagine glasses that tell you exactly who's in the room, what they look like, and whether you know them.

There are already products attempting this. Envision, an AI accessibility company, partnered with Solos to create glasses that help low-vision users recognize other people. But here's the critical difference: it requires explicit consent. The wearer takes a picture, assigns a name within the app, and builds their own database. It's opt-in identification of people you want to remember.

Meta's approach would be the opposite. Automatic identification. Pulling from existing data. No conscious decision required.

The Legitimate Use Case

Let's be fair. For accessibility, there's a compelling use case:

- A person with vision loss enters a conference room. They can't see who's there.

- The glasses automatically identify everyone based on their face.

- Accessibility problem solved.

This is real. It matters. And it's one of the few genuinely good arguments Meta can make.

Where It Goes Wrong

But here's the problem. Once that technology exists in consumer product form, once millions of people have glasses capable of real-time facial recognition, you can't separate the accessibility use case from the surveillance use case. They're the same technical system.

And historically, every surveillance technology ever created starts with a good use case. Phone tapping started with criminal investigations. Wiretapping started with national security. Facial recognition started with finding criminals and missing persons. And every single time, it expanded far beyond its original scope.

Meta's memo basically admits this. They're not thinking primarily about accessibility. They're thinking about "growth" (The Times' reporting), "engagement" (implied by "new connections"), and obvious monetization opportunities (whoever owns the identification layer owns incredible ad-targeting data).

The accessibility argument is the trojan horse. It's legitimate, but it's also the gateway to something much larger.

Estimated data shows spikes in public reaction during key events, such as the 2021 facial recognition launch and the 2025 internal memo revelation, with a potential rebound in 2026.

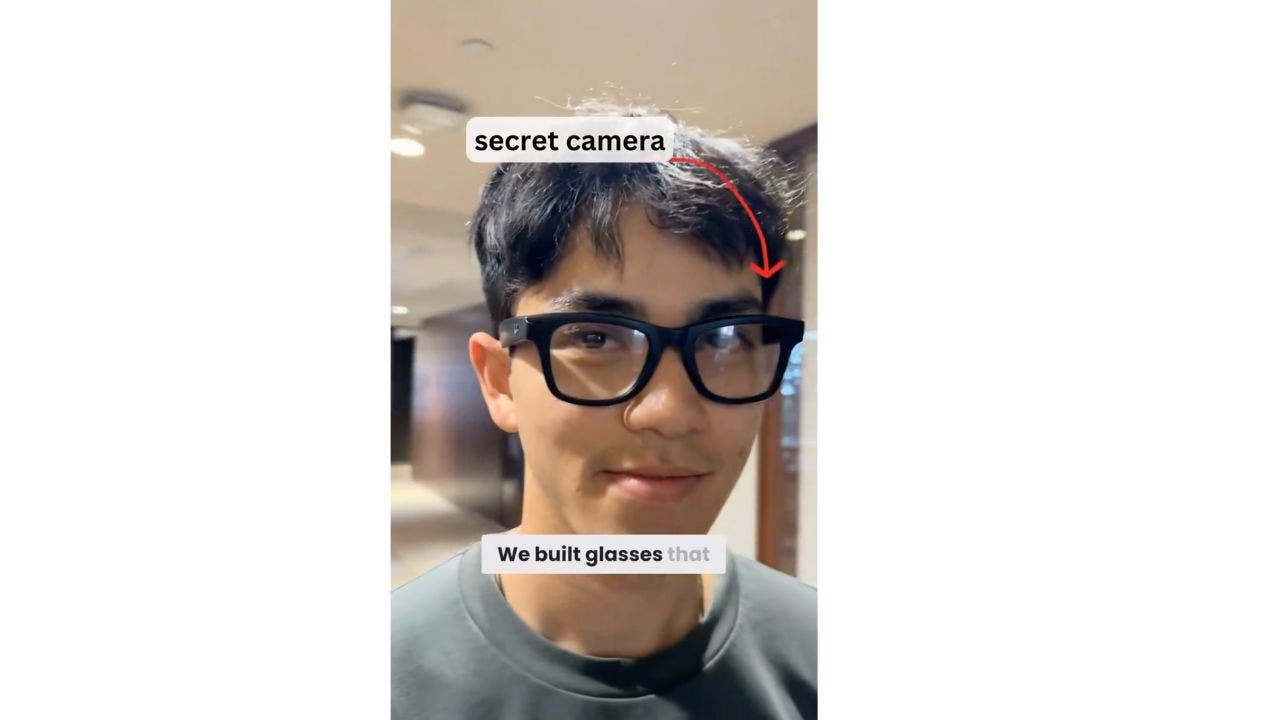

A Shocking Real-World Case: The Harvard Proof of Concept

Want to know how bad this could get? In 2024, two Harvard students built exactly what Meta's planning. Except they did it as a school project.

They took regular Ray-Ban Meta smart glasses and added facial recognition. Then they paired it with public databases. And suddenly, the glasses could identify people walking down the street and pull up their names, addresses, phone numbers, and relatives.

No consent. No authorization. Just... out there. For anyone who owns the glasses and runs their custom software.

The students released a paper on this as a warning. They explicitly wanted to show the dangers. But the damage was already done. The proof of concept existed. Everyone now knew: this is possible. And more importantly, it's not that hard.

Meta's likely using similar techniques. Facial recognition trained on billions of photos from their platforms. Cross-reference with public data. Boom. Real-time identification of pretty much anyone.

When that Harvard project went public, it sparked a flurry of headlines. "Danger! Privacy invasion!" News cycle moved on. Nothing happened. No new regulations. No technical safeguards. Just... people continuing to wear the glasses while privately freaking out.

This is what Meta is counting on. The proof of concept already exists. The public's already seen how bad it could be. And we collectively shrugged.

Privacy Risks: A Comprehensive Breakdown

Let's get specific about what could go wrong. Because there's a lot that could go wrong.

Unauthorized Surveillance and Stalking

Imagine you're trying to leave an abusive relationship. You change your number. You block them on social media. And then you run into them on the street. Except they're wearing Meta glasses with facial recognition.

They see your name. Your profile. They can look at your public posts and see where you work. Who your friends are. When you last posted a photo. The glasses turn you from someone who successfully escaped into someone who's still trackable.

Stalk-ware and spyware are already huge problems. This makes it trivial. Instead of needing expensive tracking software, an abuser just needs glasses and Meta's feature.

Discriminatory Targeting and Profiling

Law enforcement already has problems with facial recognition. Studies show these systems misidentify people of color at dramatically higher rates than white people. In some cases, the error rate is 10x higher for dark-skinned faces.

Now imagine police wearing these glasses. They could profile entire neighborhoods, running everyone's face against databases, pulling up arrest records, associations, and background checks. Civil rights groups have been warning about exactly this scenario for years.

But it's not just law enforcement. Retailers could identify "bad customers." Property managers could identify "undesirable tenants." Employers could identify job candidates by their associates or public profiles. The discriminatory applications are essentially endless.

Data Breaches and Leaked Identification Data

Meta has gotten breached before. Facebook's been breached. Instagram's been breached. Whats App's had security vulnerabilities. And we're supposed to trust that a system that identifies people and their relationships wouldn't become a target for hackers?

Imagine a database of "who's who," keyed by face, with social connections, public information, and physical location data. That's criminally valuable. That's the kind of database that would fetch serious money on the dark web. Blackmailers, stalkers, and bad actors of all kinds would pay top dollar for comprehensive identification data.

Algorithmic Bias and Misidentification

We've already talked about accuracy problems. But let's be specific. Current facial recognition systems have error rates around 0.08% for white males. For dark-skinned females, it's more like 34%.

In a system where billions of people are being identified constantly, even small error rates compound into enormous numbers of misidentifications. A 0.5% error rate across 500 million users is 2.5 million errors per day.

When the error is "the system shows you the wrong person's profile," that's awkward. When the error contributes to harassment or worse, it becomes a liability nightmare.

The Chilling Effect on Public Life

There's something called "the panopticon effect." It's a concept from philosophy: when people know they might be watched, they change their behavior. They become less free. Less spontaneous. More self-conscious.

Meta glasses with facial recognition, especially if they become mainstream, create a permanent panopticon. You can't go out in public without wondering if you're being identified, recorded, and catalogued. What you wear. Who you're with. Where you go. What you do.

That's not freedom. That's the opposite of freedom. And it happens not because of government surveillance (though that could follow), but because of corporate convenience.

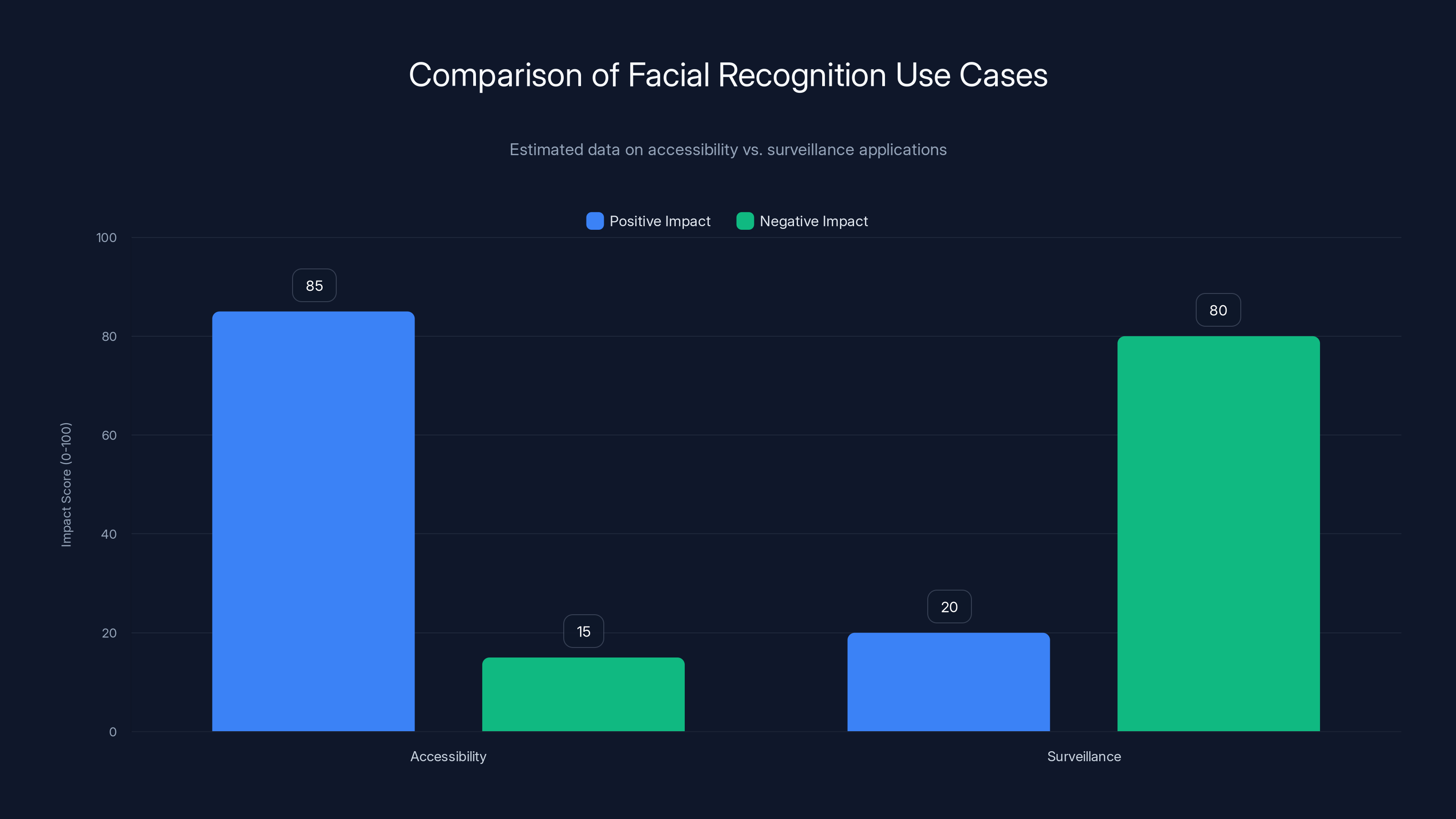

Estimated data suggests facial recognition has a high positive impact for accessibility but significant negative implications for surveillance. Estimated data.

The Regulatory Landscape: Who's Actually Doing Something?

Here's the depressing part: almost nobody's actually doing anything meaningful about this.

The EU's GDPR and Emerging Biometric Rules

The European Union is, as usual, way ahead of everyone else. Their General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) already applies to facial recognition. Under GDPR, processing biometric data requires explicit consent. Lots of consent. Not the checkbox kind. The "prove you asked specifically for this" kind.

The EU's also working on stricter biometric identification rules. They're contemplating bans on real-time facial recognition in public spaces. It's not law yet, but it's coming.

For Meta? That means any Name Tag feature in Europe would need explicit opt-in from both the wearer and the person being identified. Basically, it becomes unusable at scale, which is probably the point.

The US: Still Sleeping

The United States has almost no federal biometric privacy law. None. Zip. Zero.

There's no federal equivalent to GDPR. There's no requirement for consent. There's no requirement for transparency. The FTC has some powers to police "unfair or deceptive practices," but that's vague and requires case-by-case enforcement.

Some states have started moving. Illinois has a biometric privacy law (BIPA). California's been working on things. But it's patchwork and inconsistent. A feature legal in California might be illegal in Illinois, which is basically how you force companies to follow the strictest rule nationally.

Meta's hoping that doesn't happen. They're probably willing to launch Name Tag in the US and deal with the legal consequences later. The profit window might close them out before lawsuits stick.

Congressional Theater

Congress held hearings on facial recognition. They asked tech executives some tough questions. Those executives gave vague answers. Nothing happened. Congress moved on to other things.

There's been no serious federal legislation on facial recognition. There's been talk about regulating government use. But private companies? Still wide open.

This is the pattern. Regulated industry gets caught doing something bad. Congress holds hearings. Tech executives say they're committed to responsible innovation. Congress looks satisfied. Nothing changes.

Self-Regulation: The Punchline Nobody's Laughing At

Meta's response to privacy concerns is always the same: "We take privacy seriously." Then they point to their internal policies and their commitment to "responsible innovation."

Self-regulation, in the context of big tech, is basically a joke. Companies set their own rules, then break them when profitable. The internal consequences are minimal. The external consequences are usually just fines that amount to the cost of doing business.

Meta's been caught doing shady stuff with facial recognition before. In 2021, they were explicitly using facial recognition on photos uploaded by users without clear consent. Only when journalists and privacy advocates made a huge fuss did they dial it back. And even then, it was mostly PR damage control.

So when Meta says they'll "take a thoughtful approach," what they mean is, "We'll do it anyway, but we'll hire a PR firm to make it sound responsible."

The Business Case: Why Meta Wants This (And It's Not Pretty)

Let's talk about money. Because this is fundamentally about money.

Facial recognition, paired with social network data, is an advertiser's dream. Right now, Meta targets ads based on what you say, where you click, what you buy. It's targeted, but it's still imprecise. The system guesses.

But imagine if Meta could identify everyone you encounter. Everyone you're near. Everyone in your path. They could build a real-time map of your social sphere. Where you go. Who you're with. What you do.

Suddenly, advertising becomes incomprehensibly precise. Need to sell luxury watches? Identify people walking into luxury storefronts. Need to sell weight loss supplements? Identify people at gyms. Need to sell breakup services? Identify people leaving courthouse buildings at certain times.

It's nightmare-level targeting. And it's profitable. Horrifyingly profitable.

According to Gartner's data, companies that use real-time contextual targeting see 3x higher conversion rates on advertising. 3x. That translates to billions in additional revenue if you're Meta's scale.

So Meta's willing to risk the PR blowback. Willing to risk regulation. Willing to weather congressional theater and privacy advocacy. Because the upside is enormous. And they're betting that by the time regulation catches up, they'll already own the market.

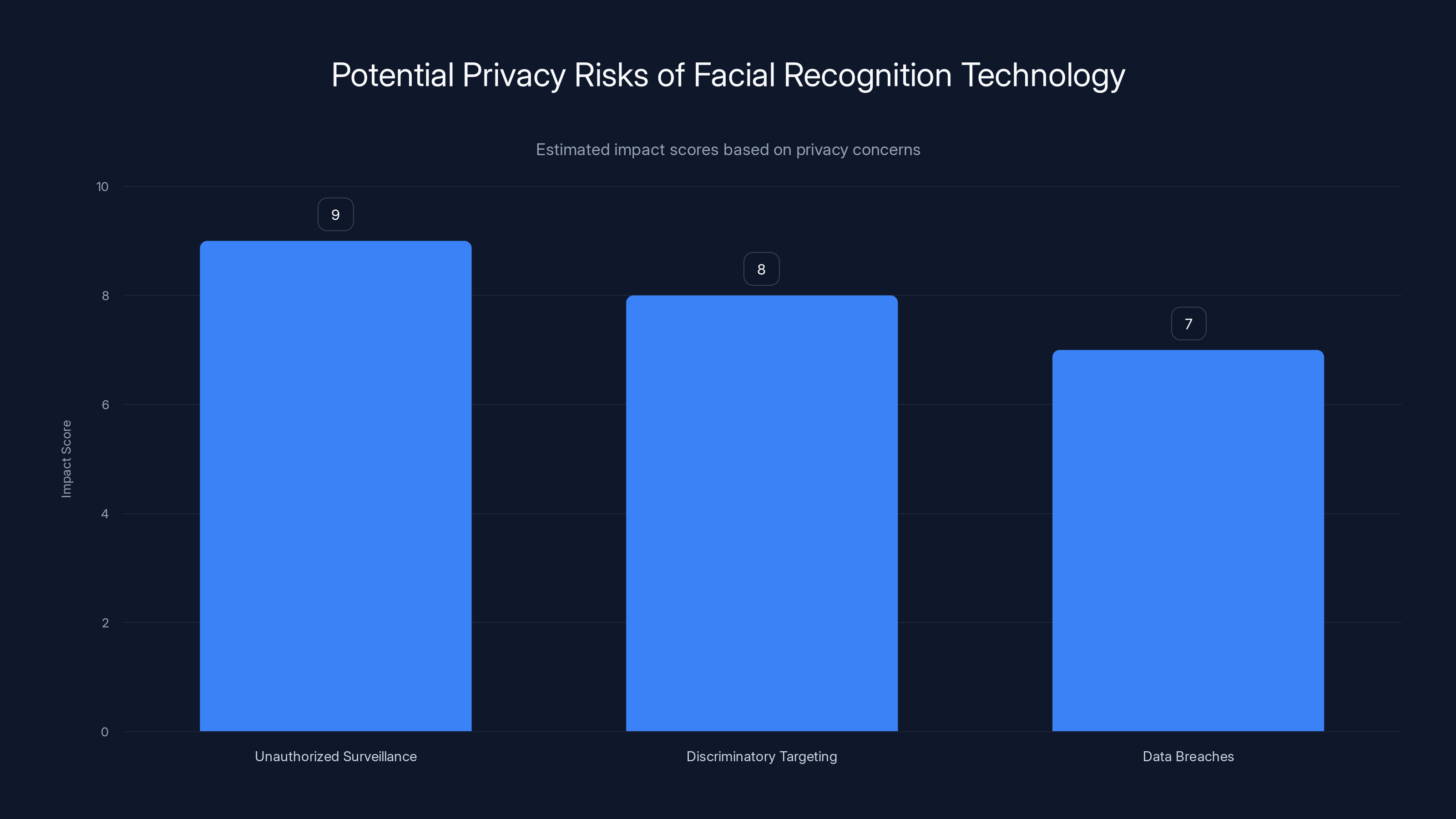

Unauthorized surveillance poses the highest privacy risk, followed by discriminatory targeting and data breaches. Estimated data based on potential impact.

Global Precedents: What Other Companies Have Done

Meta's not inventing this playbook. They're copying it.

China's Social Credit System

China's been running real-time facial recognition surveillance for years. Cameras on every street. AI systems identifying people, checking them against government databases, and assigning social credit scores based on behavior.

People who jaywalk get public shaming. People with debt get blacklisted. Political activists get tracked. It's the surveillance infrastructure of an authoritarian state, and it works because the government has both the power and the will to enforce it.

Meta doesn't have that power. But they're building the technical infrastructure that would enable it if they did. Or more realistically, the infrastructure that enables governments (and corporate actors) to do it.

UK's CCTV Networks

Britain's got more CCTV cameras per capita than almost anywhere. Cities like London have cameras on nearly every block. Early facial recognition systems were already being tested to identify people in crowds.

When Edward Snowden's revelations came out, there was outrage. And then... people just kept walking. The cameras stayed up. The surveillance continued. Now facial recognition on those cameras is being tested routinely.

Clearview AI's Scraped Database

Clearview AI is a company that scraped billions of photos from social media and built a facial recognition database. Law enforcement uses it. Private investigators use it. Celebrities were able to search themselves and find people searching for them.

Clearview argued the data was public, so scraping was fine. Courts have mostly agreed. But the company's been fined and regulated. And yet they continue operating because, well, the technology's too useful and the legal framework's too weak.

Meta's got something similar but better. They own the data. They own the platform. They own the glasses people wear.

The Timeline: When Will This Actually Launch?

According to The Times' reporting, Meta's planning a 2025 launch. That's soon. That's "this year" soon.

The memo specifically says the feature would start with accessibility use cases (conferences for blind and low-vision people) before rolling out widely. That's the beta test phase. That's where they'll work out the bugs and build the infrastructure.

By late 2025 or early 2026, expect Name Tag to be available to general users. Probably as an opt-in feature at first. "See who's in your community." "Discover connections." "Make social discovery easier."

Within a year or two of launch, it'll probably be on by default. With a privacy setting hidden four levels deep in the settings menu.

The Build-Out Phase

Right now, Meta's got Ray-Ban glasses. But they're also working on their own brand smart glasses (reportedly called Orion). They're investing heavily in AR. The glasses market is exploding. If Meta gets facial recognition right, it could become the standard feature across their entire AR ecosystem.

Once it's standard, it's impossible to remove without basically breaking the device. Which means millions of people would be carrying identification tools whether they wanted them or not.

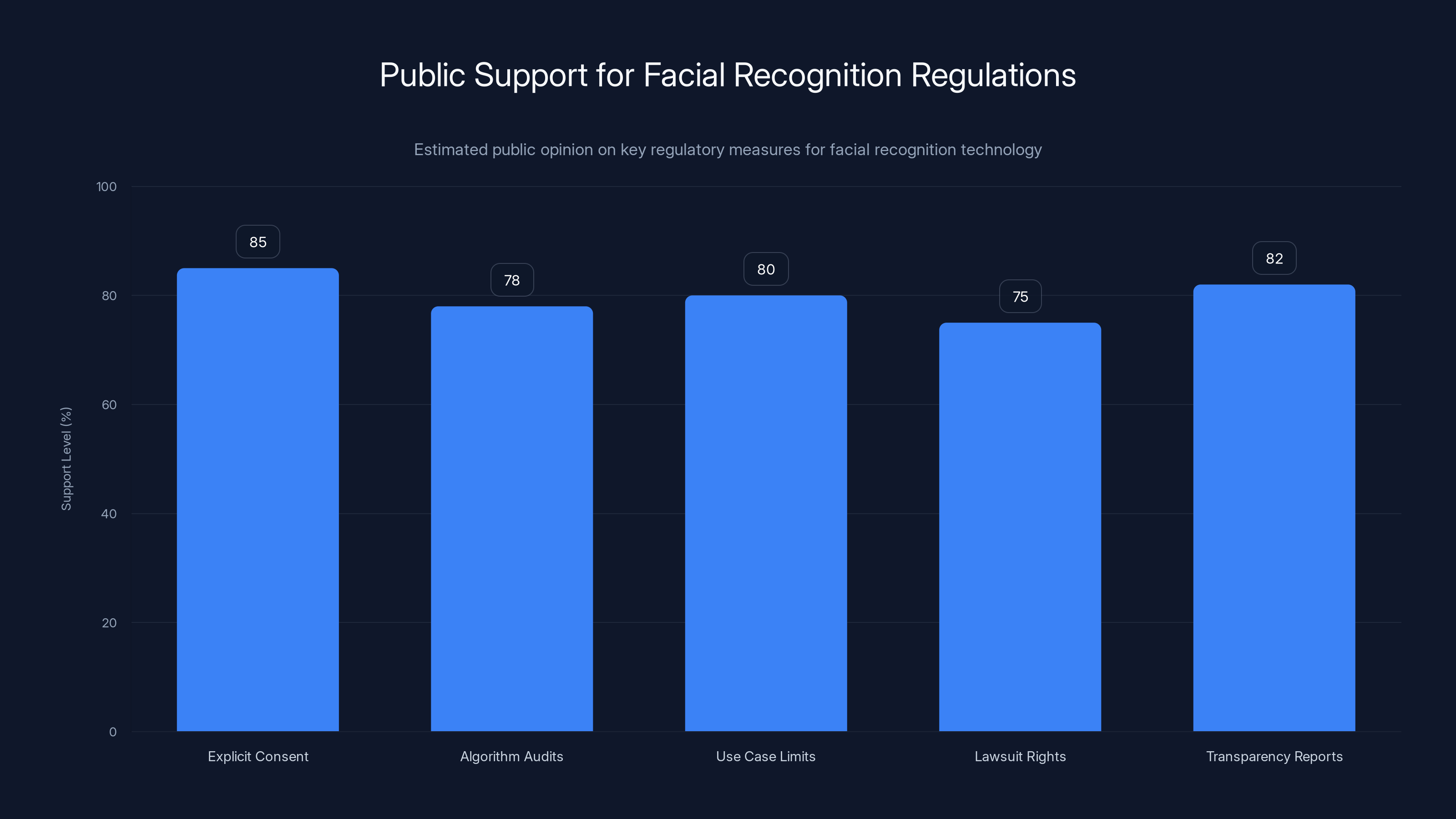

Estimated data suggests high public support for regulations on facial recognition, with explicit consent and transparency reports being top priorities.

What You Can Actually Do About This

Okay, so. It's coming. Regulation's too slow. Congress is too corrupt or incompetent. What can you actually do?

Regulatory Advocacy

Write to your representatives. I know, I know. Congress feels pointless. But state-level representatives are sometimes more responsive. Especially if facial recognition becomes a ballot issue.

Some states (Illinois, California) have stronger biometric privacy laws. If you're in a weaker state, advocating for stronger laws is actually the most effective thing an individual can do.

Personal Privacy Practices

- Don't use Ray-Ban Meta glasses: This is the most direct option. They're fine devices, but the privacy risk is real.

- Minimize your social media footprint: The more information you've made public, the more useful facial recognition becomes. Delete old photos. Make accounts private.

- Use privacy-conscious alternatives: Other smart glasses exist. They're not perfect, but they're less connected to ad networks.

Support Organizations Doing the Work

Privacy advocacy groups like the ACLU, Electronic Frontier Foundation, and Center for Democracy and Technology are fighting this stuff in court and in legislature. Supporting them (financially or through volunteering) is how systemic change actually happens.

Public Pressure

When Meta launches Name Tag, make noise. A lot of noise. The 2024 Facebook facial recognition fiasco showed that sustained public pressure works. Meta pulled the feature partially because of outrage, not because they wanted to.

If enough people care, it becomes a PR problem. And PR problems are the one thing big tech actually responds to.

The Counterargument: Why Meta Actually Believes This Is Fine

To be fair (and I hate being fair to Meta, but fairness matters), they have some actual arguments here.

Consent, Sort Of

Meta would argue that users choose to wear the glasses. If they don't want facial recognition, they can turn the feature off or just not wear them. That's technically true, but it misses the point.

In a world where everyone has glasses with facial recognition, choosing not to wear them is increasingly impractical. It's like saying, "Just don't use the internet." Technically possible. Practically impossible.

Transparency

Meta's committed to being transparent about the feature. They'll tell users it exists. They'll probably let users know when they're being identified (maybe). They're not trying to hide it.

But transparency doesn't solve the fundamental problem. A tyranny explained is still a tyranny.

Accessibility

Again, genuine accessibility benefit. For people with vision loss, this feature could be legitimately life-changing. Meta's not wrong about that.

The problem is using accessibility as cover for mass surveillance, which is exactly what Meta's doing.

Competition

If Meta doesn't build this, someone else will. This is the classic Silicon Valley argument. "We might as well do it since someone will anyway."

It's basically moral surrender dressed up as pragmatism. And yet, it's also kind of true. If Meta doesn't own the identification layer, Apple or Google will.

What Happens Next: Three Possible Futures

So where does this actually end up?

Scenario 1: Meta Launches, Faces Backlash, Dials It Back (Most Likely)

Meta launches Name Tag. Privacy advocates lose their minds. Congress holds hearings. Meta's CEO apologizes for "moving too fast." They add a few additional privacy controls. Then they quietly make the feature the default with obfuscated opt-out settings. Three years later, it's the normal way people use smart glasses.

This is the historical pattern. Gmail's Face Recognition. Facebook's facial recognition. Instagram's location tracking. All launched amid controversy. All backed off publicly. All became normalized.

Scenario 2: Real Regulation Emerges (Less Likely But Possible)

The EU passes strict facial recognition rules. The US, finally embarrassed by its regulatory ineptitude, copies them. Meta's forced to implement separate systems for different regions. The feature basically becomes unusable at Meta's target scale.

This would require Congress to actually act, which they haven't done in ages. But if pressure builds enough, it's possible.

Scenario 3: Decentralization and Proliferation (Most Dystopian)

Meta launches. Gets regulated. But then everyone realizes the technology works. Smaller companies, governments, and bad actors all build their own systems. Within five years, smart glasses with facial recognition are ubiquitous, regulated inconsistently, and basically impossible to avoid.

We end up in a world where your face is your ID, and you can't control who has access to that ID.

The Bigger Picture: Surveillance Capitalism Reaches Its Endgame

Meta's facial recognition push isn't really about smart glasses. It's the logical endgame of surveillance capitalism.

For 20 years, tech companies have been building advertising infrastructure. First, it was cookies on websites. Then it was social graphs. Then it was location data. Then it was your health data, your financial data, your relationship data.

Each time, the companies justified it. "We're connecting people." "We're personalizing experiences." "We're improving recommendation algorithms."

But really, they were building the most comprehensive surveillance machine ever created. A system that knows what you want before you want it, who you know, where you go, what you fear, and what you value.

Facial recognition is just the final piece. The last frontier. Once they have your face tied to your identity and your social graph, surveillance capitalism becomes total. There's nowhere left to hide, no data left to discover.

Meta knows this. That's why they want it so badly. That's why they're willing to risk the PR blowback. That's why they're timing it during political distraction.

They're not being paranoid about privacy advocates coming after them. They're being strategic. Because they know exactly how powerful this technology is, and they want to own it before regulation makes it impossible.

What Actually Needs to Happen

Here's my honest take: facial recognition tech isn't going away. It's too powerful, too useful, and too profitable. But it doesn't have to be a nightmare.

What we need is regulation that:

-

Requires explicit, informed consent before any facial recognition identification happens. Not checkbox consent. Real consent that demonstrates understanding of the implications.

-

Mandates algorithmic audits to ensure systems aren't discriminatory. Annual testing. Public results. Real consequences for bias.

-

Creates clear limits on use cases Facial recognition for finding missing people: acceptable. Facial recognition for targeted advertising: not acceptable.

-

Enables lawsuit rights If someone's harmed by facial recognition misidentification, they should be able to sue. Meaningfully. With real damages.

-

Requires transparency reports Companies using facial recognition need to regularly report on how many people are identified, what the data's used for, and what errors have been made.

None of this is technically hard. It's all legally and politically hard. Which is the problem.

Because Meta has engineers who can build facial recognition. What Meta doesn't have is legal rights that are stronger than corporate rights. And right now, in America, corporate rights are winning.

FAQ

What is Meta's "Name Tag" feature?

Name Tag is Meta's planned facial recognition feature for Ray-Ban smart glasses that would identify people in real time using Meta's AI and cross-reference them against social networks like Facebook and Instagram. According to The New York Times, it could show the wearer a person's name, profile, and publicly available information just by looking at them.

Why is Meta timing this release during political distraction?

Meta's internal memo explicitly stated they want to launch the feature "during a dynamic political environment where many civil society groups that we would expect to attack us would have their resources focused on other concerns." This reveals Meta's deliberate strategy to minimize privacy advocacy opposition by launching when critics are busy with other issues, which is why privacy advocates and journalists are particularly concerned about their transparency and timing motives.

How does facial recognition on smart glasses differ from smartphone facial recognition?

Smart glasses facial recognition is continuous and public-facing. While your phone's Face ID recognizes only your face for unlocking, smart glasses like Meta's would constantly identify other people as you look at them, creating real-time surveillance capabilities. This fundamental difference makes the privacy implications vastly more severe, as noted by the Harvard researchers who demonstrated this technology's potential in 2024.

What are the main privacy risks of facial recognition on smart glasses?

The major risks include unauthorized surveillance and stalking, discriminatory profiling by law enforcement and businesses, data breaches of identification databases, algorithmic bias and misidentification errors (which are worse for people of color), and the creation of a pervasive surveillance environment where people modify their behavior due to being watched. These risks compound when facial recognition is combined with social network data that Meta controls.

Has facial recognition on smart glasses been proven to work?

Yes. In 2024, Harvard students created a working proof of concept using Ray-Ban Meta glasses, facial recognition software, and public databases to identify people walking down the street and retrieve their names, addresses, phone numbers, and relatives. This demonstrated that Meta's planned feature is entirely feasible and immediately actionable with current technology.

What's the current regulatory status of facial recognition?

The EU has the strongest regulations through GDPR and emerging biometric identification rules that require explicit consent. The US has minimal federal regulation, with only a few states like Illinois and California having specific biometric privacy laws. Most countries worldwide lack comprehensive facial recognition legislation, leaving the technology largely unregulated at the moment.

Could this feature actually help people with disabilities?

Yes, for people who are blind or have low vision, real-time facial recognition that identifies people could be genuinely helpful for navigation and social interaction. However, Meta's public statements suggest their primary motivation is not accessibility but rather the broader identification of any person with a public social media profile, which turns an accessibility tool into mass surveillance infrastructure.

What can individuals do to protect themselves?

Options include not using Ray-Ban Meta glasses, minimizing your social media footprint by making accounts private or deleting old photos, supporting privacy advocacy organizations through donations or volunteering, writing to representatives about stronger facial recognition regulation, and creating public pressure when companies like Meta launch surveillance features.

When will Meta actually launch this feature?

According to The New York Times' reporting of Meta's internal memo, the company plans to launch the Name Tag feature sometime in 2025, potentially starting with testing at accessibility conferences before rolling out to general users. A wider public rollout could happen in late 2025 or 2026, though Meta hasn't made an official announcement.

Is facial recognition technology inherently biased?

Yes, current facial recognition systems show significant racial and gender bias. Studies consistently show error rates around 0.08% for white males but up to 34% for dark-skinned females. These biases exist because training datasets were predominantly composed of white male faces, and the bias compounds in surveillance applications where small error rates affect large populations.

Conclusion: The Choice We're Not Really Making

Let me be blunt. Meta's going to launch facial recognition on smart glasses. The probability is somewhere between 85% and 95%. Regulatory constraints in the US are too weak to stop them. The technology's too profitable to leave on the table. And the potential PR consequences won't be severe enough to change their calculus.

What that means is this: the surveillance infrastructure is coming. The question isn't whether it happens, but how it happens and what pushback it faces along the way.

The meta-question (sorry for the pun) is whether we actually care enough to do something about it.

Meta timed this announcement for maximum opacity. They waited until people were distracted. They knew exactly what they were doing and why. And they were probably counting on the fact that even when journalists and privacy advocates figured it out, most people would just... not care that much.

They were probably right. The story came out. Some people got angry. But it wasn't a mainstream rage moment. It didn't make the top of the news cycle for more than a few days. Congress didn't spring into action. The stock market didn't tank.

Which means Meta succeeded in exactly what they were trying to do: normalize the conversation around facial recognition surveillance until we all just accepted it as inevitable.

So here's the call to action. If you actually care about this, do something. Small thing. Big thing. Doesn't matter.

Write an email to your representative. Donate to the EFF or ACLU. Delete some photos from your social media. Don't buy the Ray-Ban glasses. Talk to people about why this matters. Vote with your attention, your dollars, and your voice.

Because the window for doing something about this is closing fast. Once the technology becomes standard, once it's normalized, once millions of people are wearing identification devices without even thinking about it, it's going to be nearly impossible to walk back.

We're not at that point yet. We're close. But we're not there.

So the question is: what are you going to do about it?

Because spoiler alert: government sure isn't going to save us. And Meta sure isn't going to regulate themselves.

It's on us.

Key Takeaways

- Meta's internal memo reveals they deliberately timed facial recognition launch during political distraction to avoid privacy advocacy opposition

- The "Name Tag" feature would enable real-time identification of people on the street, cross-referenced with social networks, creating unprecedented surveillance capabilities

- A 2024 Harvard proof of concept demonstrated this technology already works, allowing identification of strangers with retrieval of addresses, phone numbers, and relatives

- Facial recognition accuracy varies dramatically by race (0.08% error for white males vs 34% for dark-skinned females), raising serious discrimination concerns

- US lacks meaningful federal facial recognition regulation while EU enforces strict GDPR and AI Act rules, creating regulatory patchwork Meta can exploit

- The business case is massive: real-time contextual targeting could increase advertising conversion rates 3x, translating to billions in additional revenue

- Meta plans 2025 launch starting with accessibility testing, with wider rollout likely in late 2025-2026 if not successfully blocked

- Three plausible futures emerge: public backlash leading to feature dial-back (most likely), strict regulation making it unusable (less likely), or decentralized proliferation (most dystopian)

Related Articles

- Meta's Facial Recognition Smart Glasses: What You Need to Know [2025]

- Meta's Facial Recognition Smart Glasses: Privacy, Tech, and What's Coming [2025]

- Ring Cancels Flock Safety Partnership Amid Surveillance Backlash [2025]

- Discord's Age Verification Disaster: How a Privacy Policy Sparked Mass Exodus [2025]

- Ring's Police Partnership & Super Bowl Controversy Explained [2025]

- AI Ethics, Tech Workers, and Government Surveillance [2025]

![Meta's Facial Recognition Smart Glasses: The Privacy Reckoning [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/meta-s-facial-recognition-smart-glasses-the-privacy-reckonin/image-1-1770997281360.jpg)