Meta's Metaverse Gamble Failed. Here's What Happened and Why It Matters

Remember when Mark Zuckerberg stood on stage and declared that the metaverse was the future? When Meta spent tens of billions reshaping itself around virtual worlds, VR headsets, and immersive digital experiences? That vision is officially dead.

In early 2025, Meta took a sledgehammer to its grand metaverse ambition. The company announced that Horizon Worlds, its flagship virtual social platform, would abandon VR entirely and move "almost exclusively mobile." This wasn't a minor pivot. This was a full-scale strategic reversal that signals one of the most expensive tech miscalculations in recent memory.

Meta's Reality Labs division has torched nearly $80 billion since 2020. Think about that number for a second. Eighty billion dollars. That's more than the GDP of many countries. It's more than Apple's annual R&D budget. And it was spent building a future that nobody wanted.

This isn't just a story about one product failing. It's a window into how even the world's largest tech companies can misread markets, ignore user behavior, and chase visions so compelling that they override basic business logic. It's also a masterclass in knowing when to kill something and pivot hard.

Let's break down what happened, why it happened, and what it means for the future of VR, AI, and the platforms we'll actually use.

The Metaverse Dream: What Meta Actually Believed

To understand this failure, you need to understand what Zuckerberg and Meta's leadership genuinely believed about the future. In 2021, when Horizon Worlds launched, the company wasn't making a cynical bet. They believed—truly believed—that immersive VR social experiences would become the primary way humans interact online.

The pitch made sense, at least in theory. The metaverse concept promised something revolutionary: instead of staring at a 2D screen, you'd put on a headset and exist in a 3D space with your friends. You'd see their avatars, hang out, play games, attend events. It would feel more real, more present, more human than video calls or text.

This wasn't just Zuckerberg's dream. The entire tech industry bought in. Nvidia invested heavily in metaverse infrastructure. Microsoft launched Mesh. Roblox and Fortnite started positioning themselves as metaverse platforms. Even Web 3 projects built entire business models around metaverse land and virtual real estate.

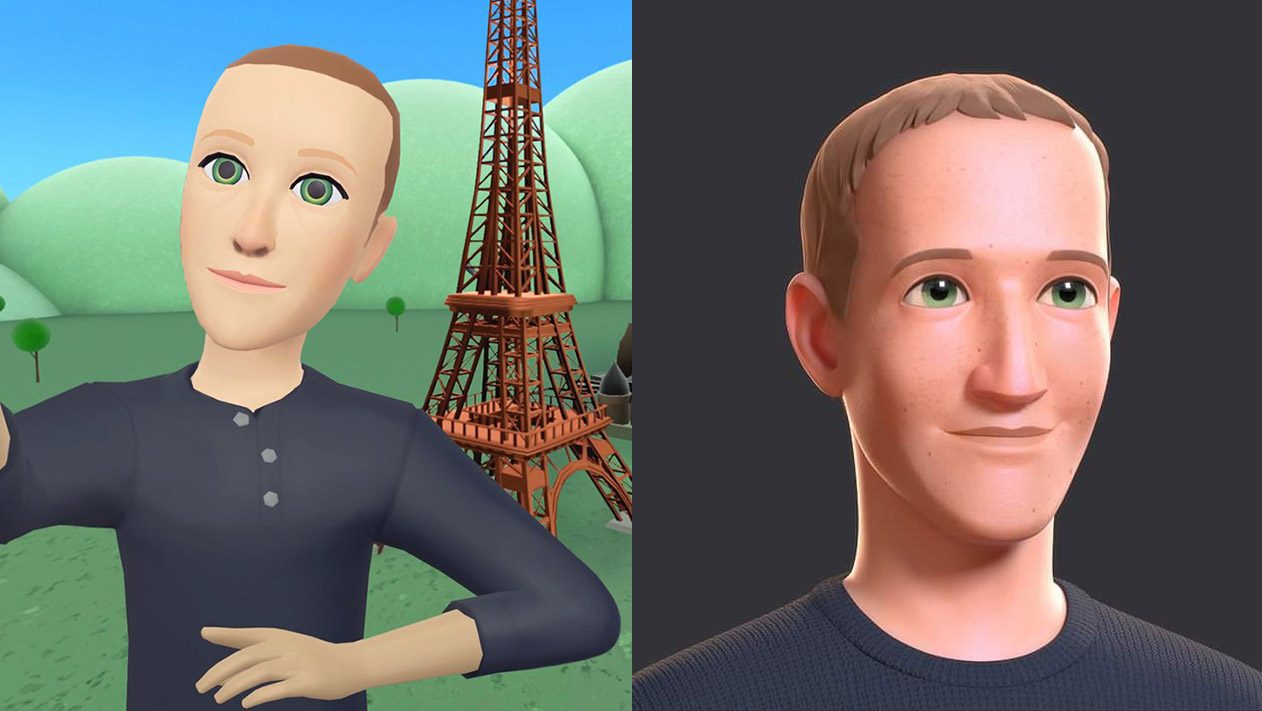

But there were warning signs from day one. Horizon Worlds launched to tepid reviews. Users found the avatars creepy. The graphics looked dated compared to other games. Performance was choppy. And most importantly, nobody could articulate why you'd want to hang out in this virtual space instead of, well, just texting your friends or hopping on a Discord call.

Meta didn't ask that question hard enough. They built the metaverse because they believed in the metaverse. They committed billions because committing billions meant you were serious. They hired thousands of engineers because that's what you do when you're restructuring an entire company around a new vision.

The problem? The users never showed up.

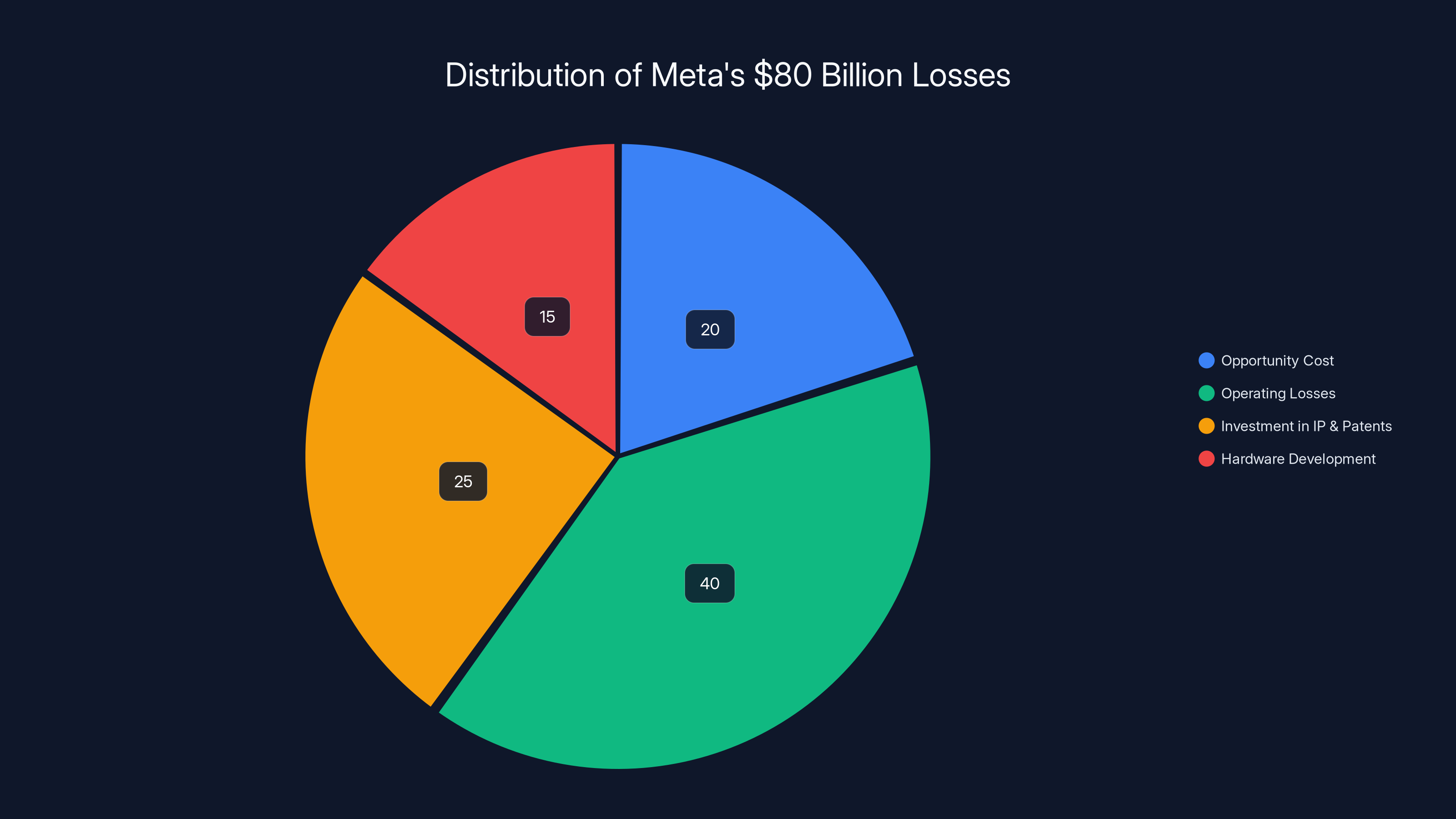

Estimated data shows that 40% of the $80 billion loss was due to operating losses, while 25% was invested in valuable IP and patents, highlighting significant opportunity costs and investments in hardware development.

The Metaverse's Fatal Flaws: Why Nobody Wanted It

Let's talk about why the metaverse actually failed, because the reasons are instructive for any tech company building new platforms.

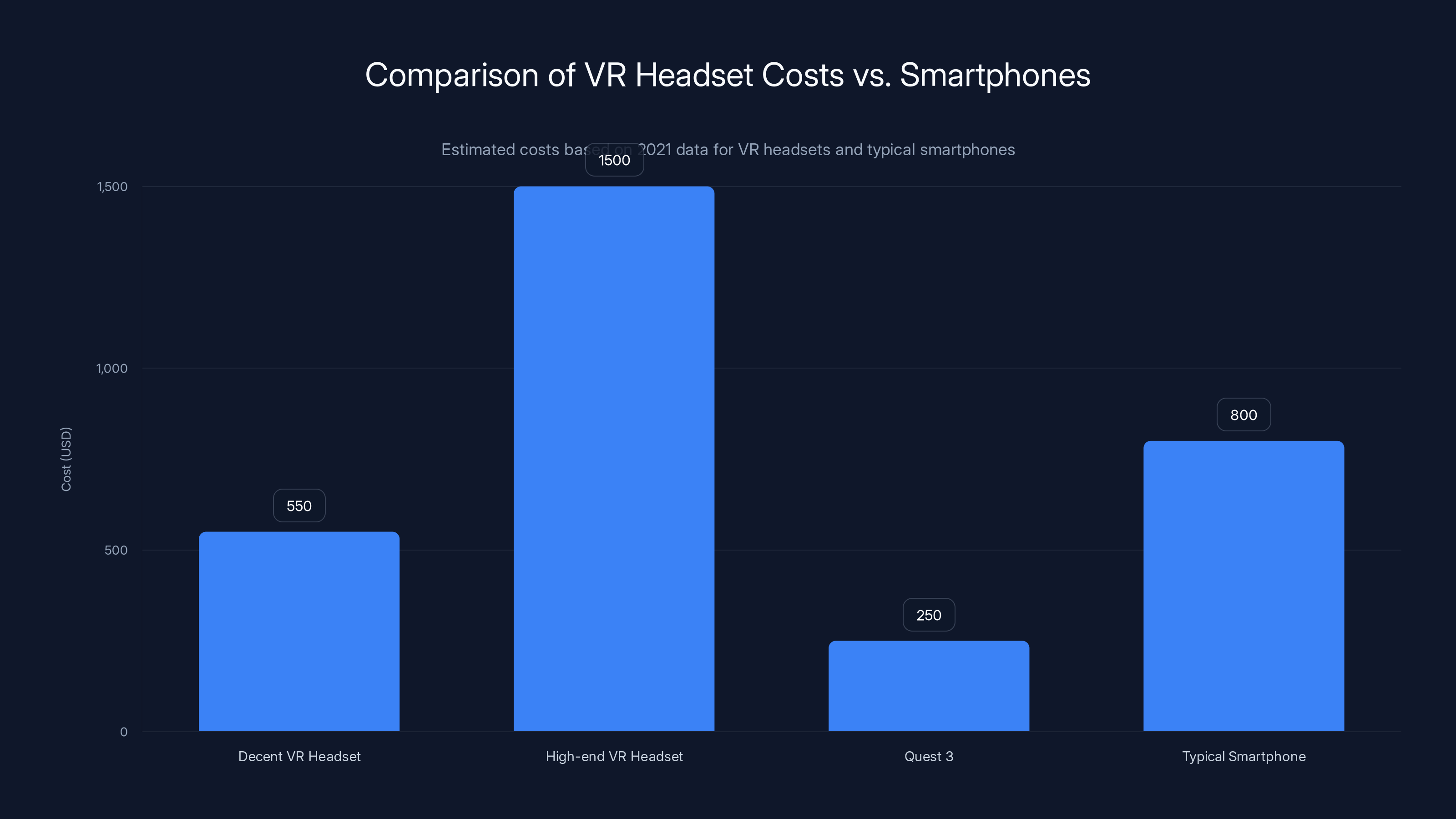

VR Hardware Was Too Expensive and Too Uncomfortable

In 2021, a decent VR headset cost

Meta tried to address this by making cheaper headsets like the Quest 3 at lower price points. But even at

The Graphics and Experience Didn't Match the Hype

When you put on a Horizon Worlds headset and looked at your avatar—it was... rough. The character models looked like something from a 2010-era game. The animations were stiff. The physics felt off. Compare that to sitting in an actual Roblox world, which is 2D but colorful, charming, and full of actual social games. Or sitting in Fortnite, where the graphics are gorgeous and the gameplay is actually fun.

Horizon Worlds felt like work. It felt like a presentation. It didn't feel like hanging out.

The Network Effects Weren't There

Social platforms succeed because of network effects: the more people on the platform, the more valuable it becomes. But Horizon Worlds was chicken-and-egg problem in reverse. Not enough cool people used it to attract more people. This created a spiral: fewer users meant fewer experiences, which meant even fewer reasons to visit.

Meanwhile, your friends were already on Instagram, Tik Tok, and Discord. Why would they spend 30 minutes putting on a headset to socialize in an uncomfortable 3D space when they could just open an app that's already in their pocket?

The Use Case Was Never Compelling Enough

This is the fundamental problem. For most people, the metaverse didn't solve a meaningful problem. It wasn't faster than existing communication. It wasn't easier. It wasn't more private. It was just... different. And "different" isn't a business model.

Meta had some compelling use cases—meeting with people across the world, virtual events, collaborative workspaces—but these are niche markets. There's a real use case in enterprise (companies gathering remotely), but Meta's focus was always consumer social. And consumers never bought in.

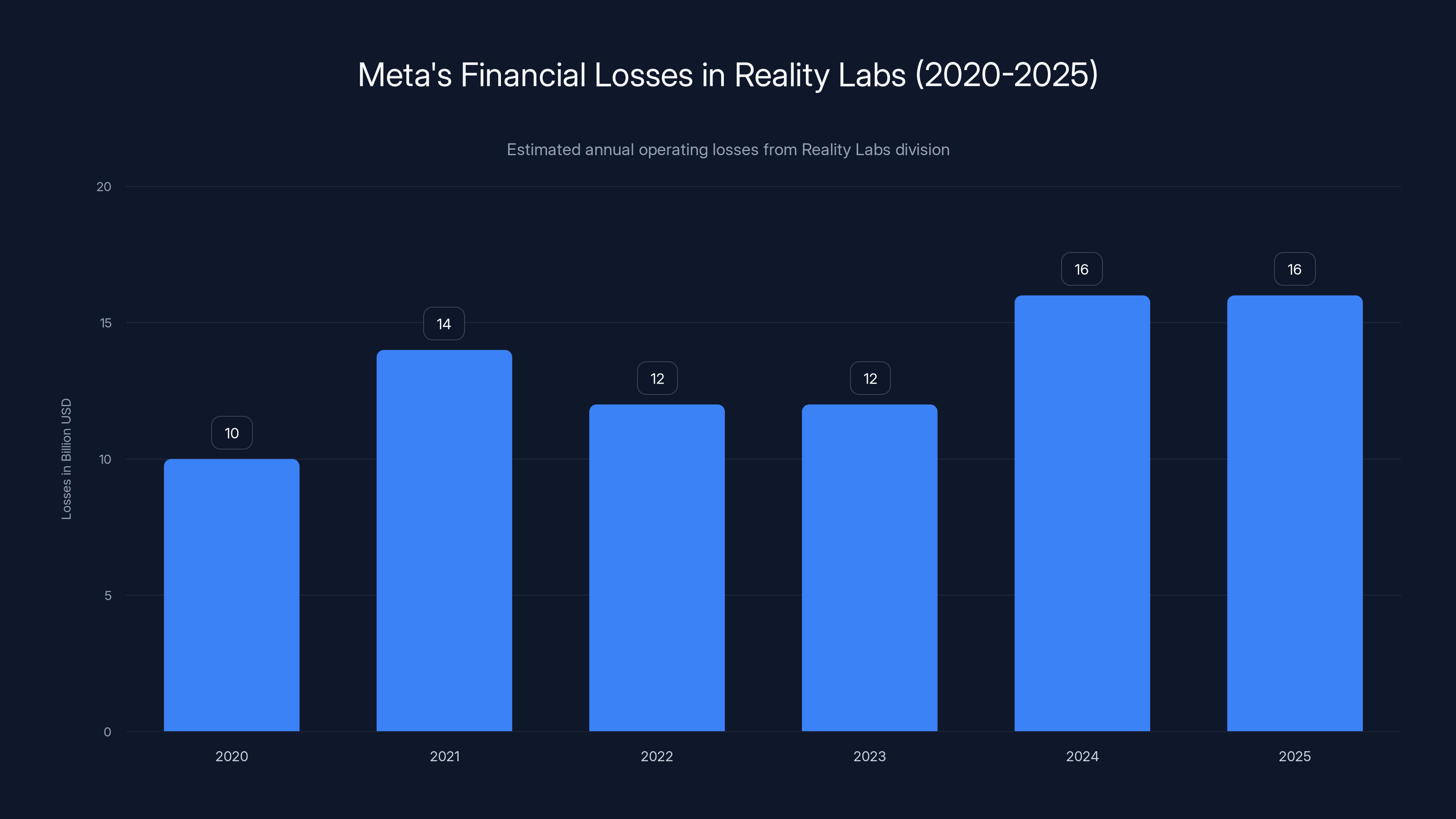

Meta's Reality Labs faced significant financial losses, peaking at $16 billion annually by 2024 and 2025. Estimated data based on reported figures.

Meta's Reality Labs: How a Billion-Dollar Division Burned Cash

By 2023, it became clear that the metaverse strategy wasn't working. So what did Meta do? Double down.

Meta's Reality Labs division, led by Andrew Bosworth, became a corporate black hole. The division employed thousands of engineers working on hardware, software, and AR/VR experiences. The operating loss in 2022 alone was

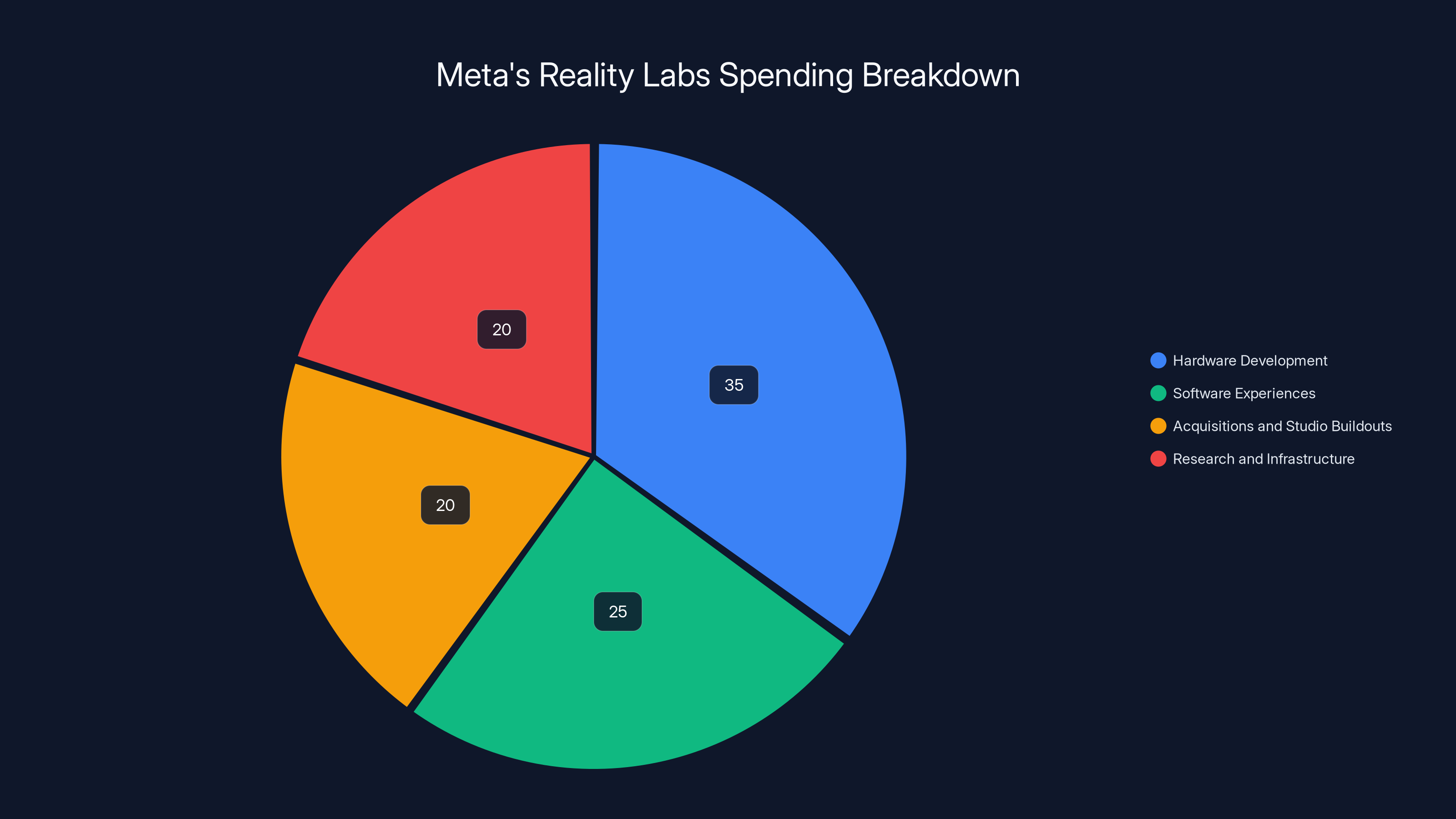

Here's the breakdown of what Meta was actually doing with that money:

Hardware Development

Meta invested heavily in building its own VR headsets: the Quest Pro ($1,500), Quest 3, and various prototypes of AR glasses. Each generation promised improvements, better performance, better graphics. None of it mattered if nobody wanted to wear the thing in the first place.

Software Experiences

Meta invested in building games and social experiences for Horizon Worlds and the broader Oculus platform. Games like Beat Saber and Superhot were actually good. But they were niche gaming experiences, not "the future of social interaction."

Acquisitions and Studio Buildouts

Meta acquired companies like Supernatural (a VR fitness app for $100+ million) and built out entire VR game studios. In late 2024 and early 2025, the company started shutting many of these down. Supernatural moved to "maintenance mode." Entire game studios were dissolved.

Research and Infrastructure

Meta spent billions on research facilities, prototype development, and the infrastructure to support a metaverse that might never exist at scale. This included AI researchers, hardware engineers, and software teams all working toward a vision that kept becoming more uncertain.

The brutal math:

The Pivot: Why Mobile Wins Over VR

By late 2024, the strategy shifted. Meta's leadership, particularly in Reality Labs, started asking the question they should have asked in 2020: "What do users actually want?"

The answer: they want to play games and socialize on platforms they already use. On mobile. On their phones.

This is where the strategy gets interesting. Instead of building a VR metaverse, Meta decided to build Horizon Worlds as a mobile-first social gaming platform that competes with Roblox and Fortnite.

The logic is sound: Roblox has 600+ million registered users and generates billions in revenue. Fortnite has 500+ million registered users. Both platforms let users socialize, play games, and create content. Both are primarily played on mobile. Both have demonstrated that there's massive demand for synchronous social gaming.

Meta has one advantage that neither Roblox nor Fortnite has: 1.2 billion daily active users on Facebook and Instagram. If Meta can leverage its existing social networks to drive users to Horizon Worlds' mobile experience, it could actually become significant.

Samantha Ryan, VP of Content at Reality Labs, explained the strategy in a blog post: "We have a unique ability to connect those games with billions of people on the world's biggest social networks." This is true. Neither Roblox nor Fortnite has that distribution advantage.

So the pivot makes strategic sense. But it also represents a humbling admission: the metaverse was wrong. VR as the primary computing platform was wrong. The future isn't immersive 3D social spaces. It's the same thing people have been doing for years, just on better platforms with better games.

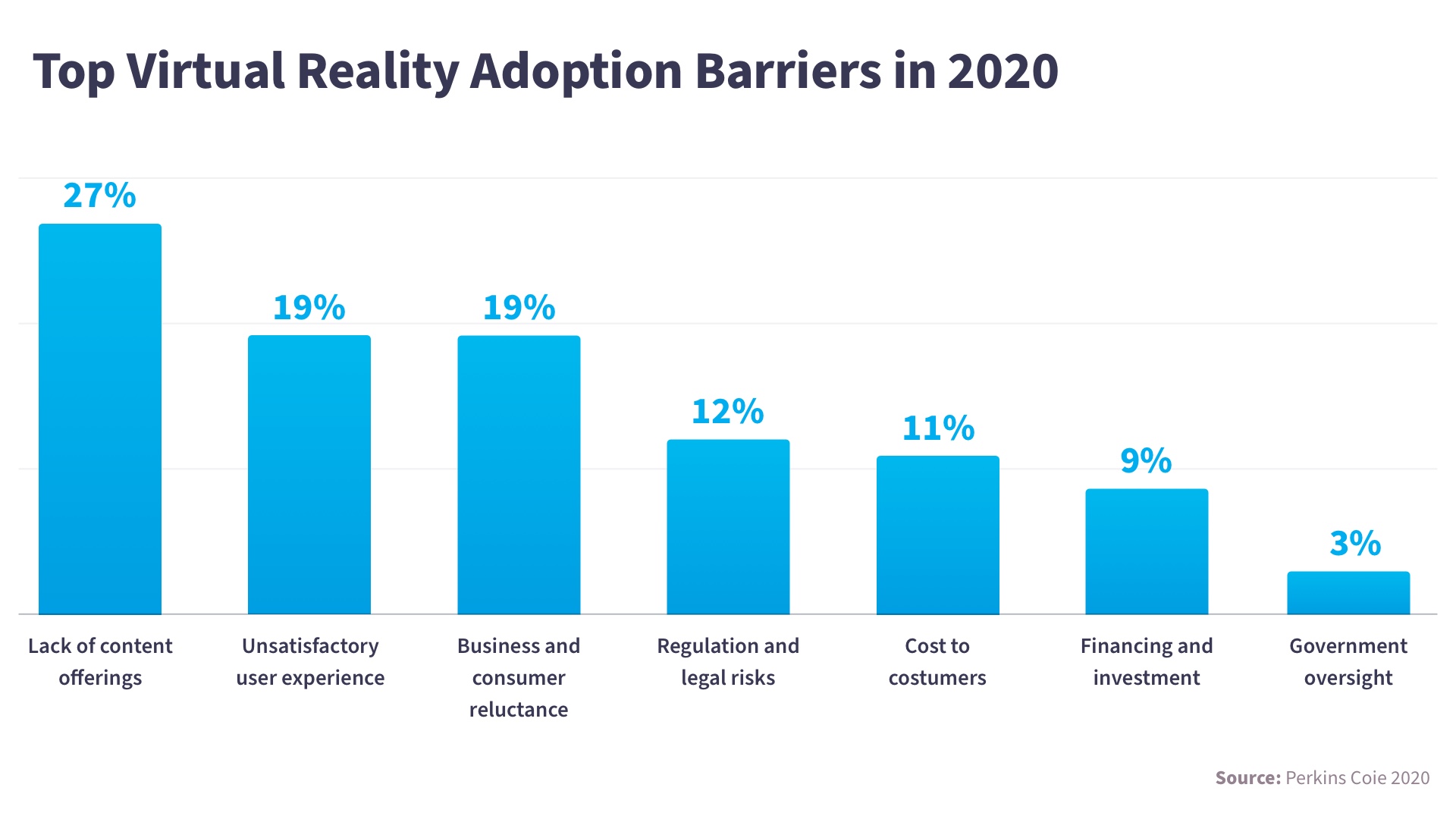

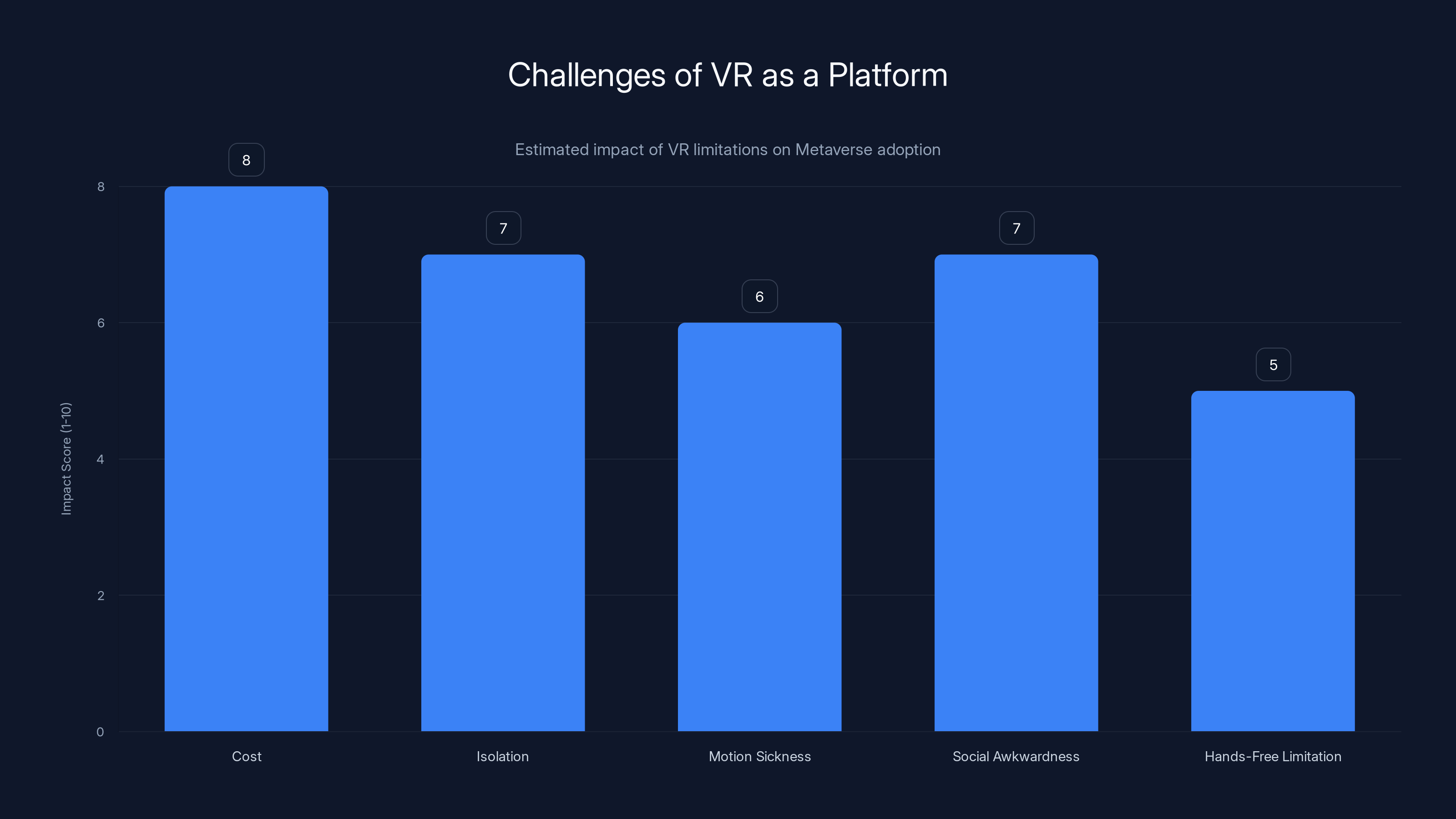

Estimated data shows that high costs and social awkwardness were major barriers to VR adoption for the metaverse, with scores of 8 and 7 respectively.

The Layoffs and Studio Shutdowns: A Division in Transition

In late 2024 and early 2025, Meta made significant organizational changes within Reality Labs. The company laid off roughly 1,500 employees from the division—about 10% of its workforce. This wasn't random. It was strategic.

Meta shut down several VR game studios that were building experiences for the old metaverse vision. The company sunset production on Supernatural, its VR fitness app acquired for $100+ million, moving it into "maintenance mode." This is corporate speak for: "We built this. We spent a fortune. We're letting it slowly die."

These decisions signal a clear message: Meta is no longer betting on VR as a consumer entertainment medium. The layoffs weren't because the division is irrelevant. They happened because Meta is radically rightsizing the division to match its new, smaller ambitions.

The employees who left were disproportionately those working on metaverse experiences—the social VR worlds, the avatar systems, the virtual event infrastructure. The employees who stayed were those working on:

- Mobile gaming infrastructure for Horizon Worlds

- Hardware engineering for VR headsets (now positioned as niche gaming devices)

- AI research for next-gen applications

- AR/smart glasses development (more on this below)

This is brutal for anyone who believed in the metaverse vision. But it's rational from a business perspective.

The AI Pivot: Why Meta Abandoned VR for Artificial Intelligence

Here's the critical part of Meta's strategy shift that most commentary misses: the metaverse didn't just fail. It lost out to artificial intelligence.

Meta's leadership realized something important around 2023-2024: The future of computing isn't VR. It's AI. Specifically, AI that understands language, can have conversations, and can perform complex tasks on behalf of users.

Mark Zuckerberg explicitly said this during Meta's earnings call in early 2025: "It's hard to imagine a world in several years where most glasses that people wear aren't AI glasses."

Notice the shift in positioning. Meta's still making glasses. But instead of being VR devices for immersive worlds, they're AI-enabled glasses that augment reality with intelligent information.

This is a completely different product category. Meta's Ray-Ban smart glasses, for example, let you point your glasses at something and get AI-powered information about it. Want to know the name of a plant? Point. Want to translate a sign? Point. Want to have a voice conversation with an AI assistant? Talk to your glasses.

Zuckerberg also noted that sales of Meta's smart glasses tripled within the last year, calling them "some of the fastest growing consumer electronics in history." This is remarkable. Meta finally found a glasses-based product that people actually want.

Meanwhile, Meta has been investing heavily in AI models and AI research. The company released Llama 3, an open-source large language model that competes with Chat GPT and Claude. It integrated AI features throughout its apps. It's building AI agents and AI-powered search.

The message is clear: this is where the future is. Not in virtual worlds. Not in immersive metaverses. In AI that's integrated into the glasses you wear, the devices you use, and the platforms you already visit.

Estimated data shows that in 2023, Meta's Reality Labs allocated the largest portion of its budget to hardware development, followed by software experiences, acquisitions, and research infrastructure.

Why the Metaverse Failed: A Post-Mortem

Let's zoom out and examine the metaverse failure at a high level. Because this isn't just about Meta. It's about how a compelling vision can be completely wrong, and how even brilliant companies can misread markets.

The Vision-to-Reality Gap Was Too Large

The metaverse wasn't a bad idea in theory. But the gap between the theory and the reality was massive. The theory: immersive 3D social spaces where humans feel present with each other. The reality: choppy graphics, creepy avatars, motion sickness, social awkwardness, and nobody using it.

Meta thought it could bridge that gap with investment and willpower. Turns out, you can't engineer cultural adoption. You can't force a platform into existence through sheer spending. Eventually, actual humans have to want to use it, and they didn't.

The Wrong Computing Platform Was Chosen

Meta bet on VR as the computing platform of the future. But VR has fundamental limitations:

- It requires dedicated hardware that's expensive

- It's isolating (you can't do other things while wearing a headset)

- It causes motion sickness in some people

- It makes social interaction feel awkward, not natural

- It's not hands-free (you need controllers or hand tracking)

Meanwhile, smartphones were solving similar problems with dramatically less friction. A smartphone is something you already carry. It doesn't require you to be isolated. It works throughout your day. It's affordable.

If the metaverse had been built on mobile first instead of VR, it might have had a chance. But Meta's vision was fundamentally wedded to the idea of immersive VR. When that didn't work, the whole strategy collapsed.

Enterprise vs. Consumer Reality Mismatch

There IS a real market for VR in enterprise. Companies genuinely benefit from remote collaboration spaces, virtual training environments, and immersive data visualization. But that market is maybe $10-20 billion annually, not the hundreds of billions Meta imagined.

Meta's leadership confused the enterprise opportunity with a consumer opportunity that didn't exist. Most humans don't want to spend hours in a VR headset. They'll use it for gaming sometimes. For training occasionally. But as a primary way to socialize? Never happened.

The Competition Was Underestimated

Meta assumed that having billions of users and billions of dollars would guarantee dominance in any new platform it entered. This assumption was wrong.

Roblox had a 15-year head start building a user-generated content platform. Fortnite had Epic Games' expertise in game development and graphics. Discord had built the best social infrastructure for gaming. Meta thought it could out-spend these competitors and win anyway.

But in software, being first to market and having better community infrastructure matters more than raw spending. Meta couldn't buy its way into cultural relevance the way it had with Instagram and Whats App. Horizon Worlds was a native experience, not an acquisition, and it had to be built from scratch against entrenched competitors.

Organizational Incentives Pushed the Wrong Direction

Once Meta committed $80 billion to the metaverse and reorganized the entire company around it, the organizational incentives became perverse. Success was defined as "the metaverse must work," not "what do users actually want?"

Middle managers were evaluated on whether they hit metaverse adoption targets. Engineers were given raises for building metaverse features. Product managers crafted roadmaps assuming the metaverse would succeed. At no point did anyone seriously ask, "Should we actually be doing this?"

This is a trap that large organizations often fall into. You commit to a vision. You reorganize around it. You hire people to execute it. Now failure means everyone admits they were wrong, people get fired, and careers are damaged. So instead, you keep believing in the vision even as evidence mounts that it's failing.

Zuckerberg didn't help by being the vision's biggest evangelist. When the CEO is on the board of his vision, challenging that vision becomes career suicide.

What Horizon Worlds Looks Like Now: The Mobile Future

So what's actually happening with Horizon Worlds now that it's pivoting to mobile?

The platform is being rebuilt from the ground up as a mobile-first social gaming platform that leverages Meta's existing distribution. Instead of putting on a VR headset, you open an app on your iPhone or Android phone. You create an avatar. You hang out in social spaces. You play games. You socialize synchronously with friends.

This is basically what Roblox does, except with better integration into Facebook and Instagram. Horizon Worlds will potentially be able to invite your Facebook friends directly. It can send notifications through Instagram. It can be promoted to Meta's 1.2 billion daily active users.

The explicit strategy, as stated by Samantha Ryan, VP of Content at Reality Labs: "We're going all-in on mobile. Thanks to our unique ability to connect those games with billions of people on the world's biggest social networks."

Will this work? Maybe. Roblox and Fortnite are incredibly successful. There's demonstrable demand for this category. Meta's distribution advantage is real. But Horizon Worlds starts from a place of severe disadvantage:

- Brand damage: The app is already associated with failure and creepy avatars

- Competition: Roblox and Fortnite are entrenched with billions of dollars in annual revenue

- Late timing: Mobile social gaming is a mature market, not an emerging one

- Talent: Many of Meta's best gaming talent left during the Reality Labs restructuring

Meta might succeed with Horizon Worlds on mobile, but it will never be the transformative success that the VR metaverse was supposed to be. It'll be a solid gaming platform. Maybe it'll hit 10-50 million users. But that's not a "change the world" story.

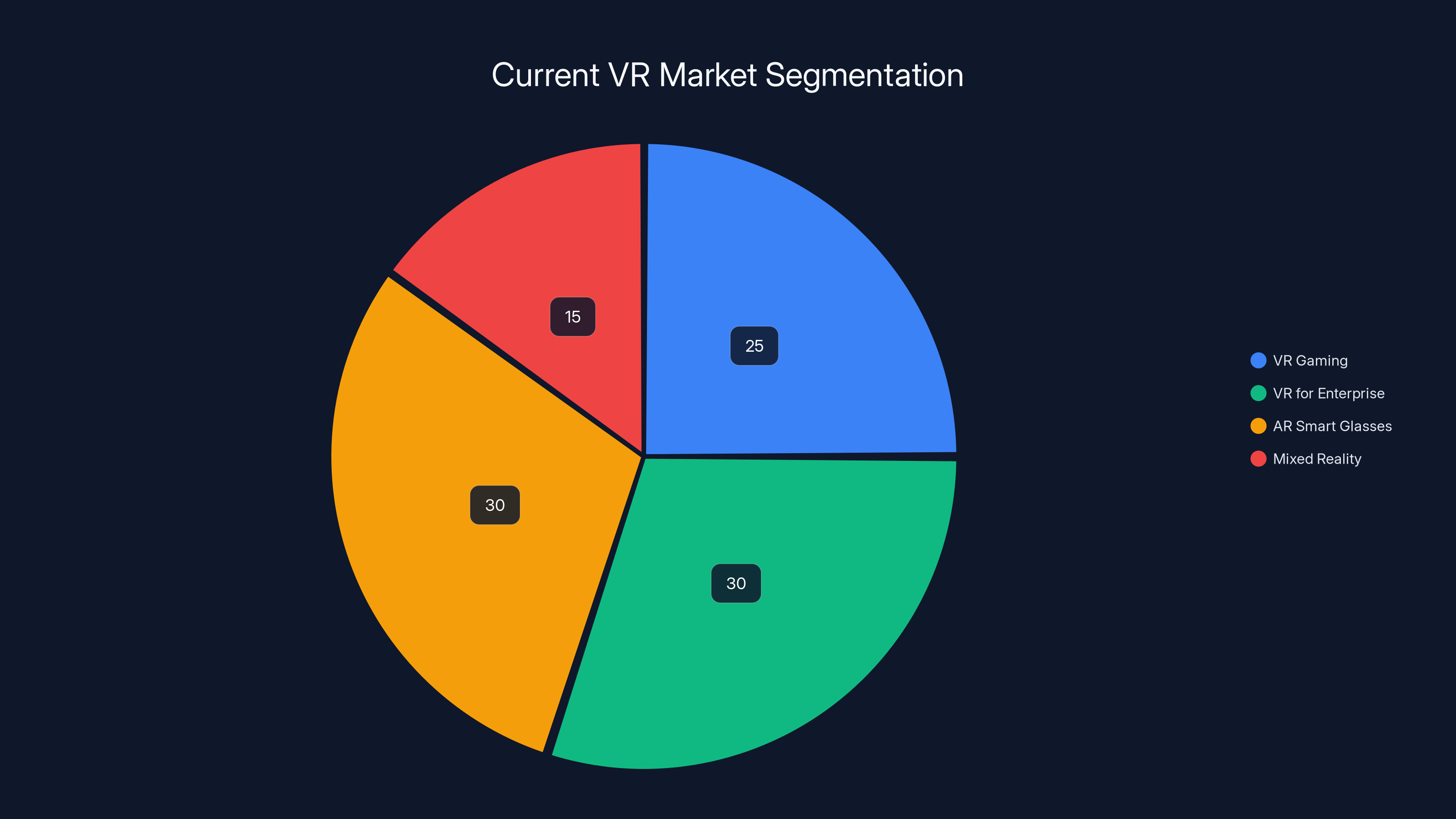

Estimated data shows VR gaming, enterprise applications, and AR smart glasses each hold significant shares of the VR market, with mixed reality still emerging.

The Financial Impact: What $80 Billion Actually Means

Let's put the financial impact of this failure into perspective, because the numbers are staggering.

The Cost of Failure

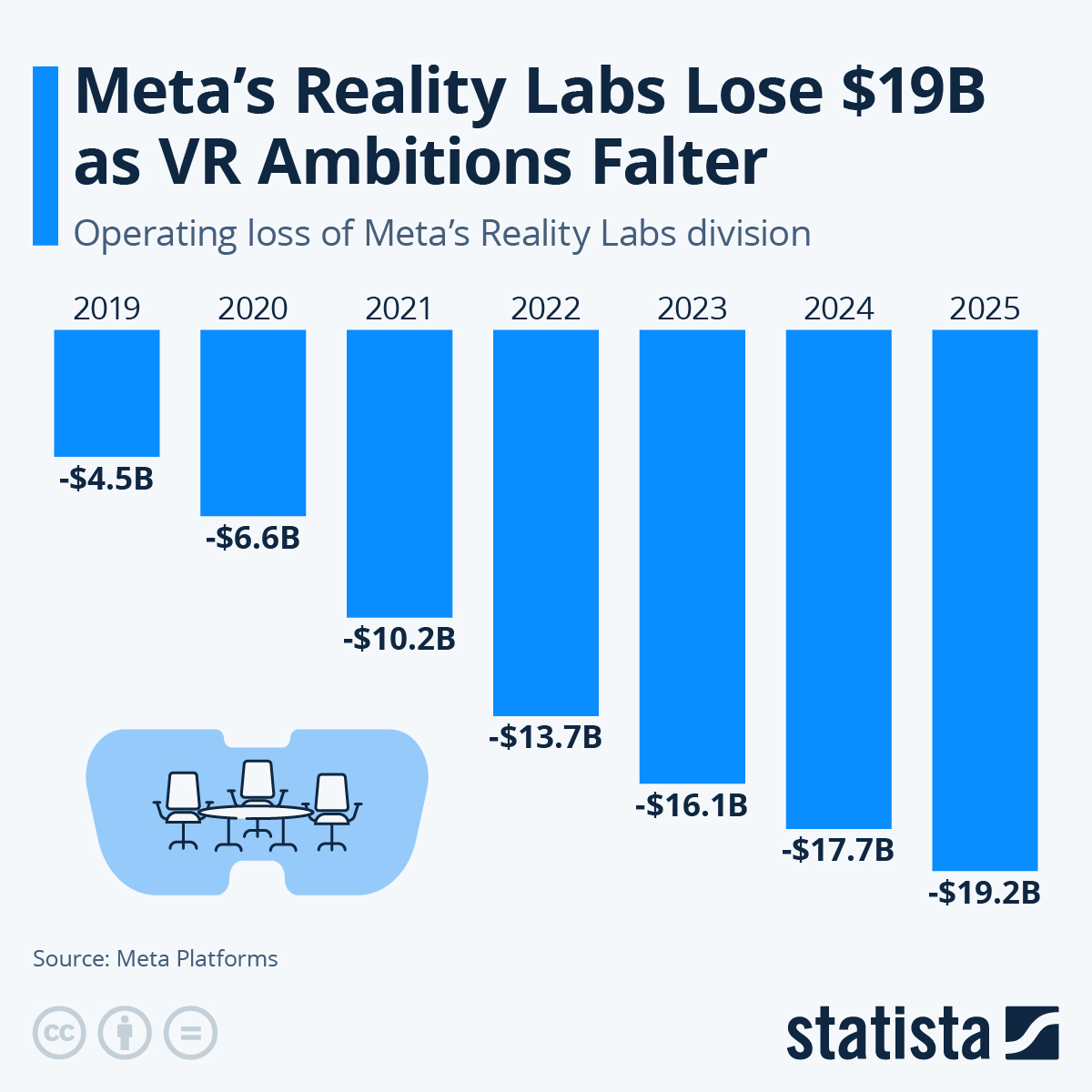

Meta's Reality Labs division lost nearly $80 billion between 2020 and 2025. To put this in context:

- This is more than the entire annual market capitalization of many large companies

- It's equivalent to Meta's entire annual revenue in 2018

- It's roughly 20% of Meta's total operating income over that period

- It represents opportunity cost: this capital could have been invested in AI, distributed elsewhere, or returned to shareholders

The Impact on Meta's Financial Performance

The Reality Labs losses significantly dragged on Meta's overall profitability. In 2022 and 2023, when Meta was already facing scrutiny over slowing user growth and declining ad revenue, Reality Labs operating losses of $12-13 billion per year raised serious questions about management effectiveness.

Investors became increasingly vocal about these losses. Activist investors called for transparency. Analysts questioned Zuckerberg's judgment. And in late 2024, Meta's board finally pressured the company to get serious about unit economics across all divisions.

The Sunk Cost Fallacy

One way to think about what happened is through the lens of sunk cost fallacy. Meta invested

But that's exactly when you should kill projects: when they're not working and the data shows they won't work at scale. Meta finally did this, but it took nearly five years of losses.

What Meta Got for Its Money

It's important to note that $80 billion wasn't entirely wasted. Meta built:

- Valuable IP and patents around VR, AR, display technology, and interaction design

- Hardware that's actually good: The Quest 3 and Ray-Ban smart glasses are genuine achievements

- Talented engineers and researchers in AR/VR who are now working on AI and other projects

- Market education: The metaverse discourse, however wrong it turned out to be, educated consumers about AR/VR possibilities

- A smoking gun warning: A cautionary tale about betting the company on a vision without sufficient user validation

But fundamentally, the company bet $80 billion that humans would want to spend significant time in immersive VR social spaces. They were wrong. And that's expensive to be wrong about.

Lessons for Tech Leaders: What to Learn from the Metaverse Failure

The metaverse failure offers several crucial lessons for tech leaders and entrepreneurs building new platforms:

1. Vision Must Be Grounded in User Behavior

A compelling vision is valuable. But it must be rooted in understanding what users actually want, not what you hope they'll want. The metaverse vision was compelling in theory but disconnected from user behavior. Most humans simply didn't want immersive VR social spaces, no matter how well they were executed.

The lesson: Validate with users early and often. Run experiments. Watch what people actually do. Don't confuse investor excitement or analyst interest with actual product-market fit.

2. Being First Matters, But Execution Matters More

Meta had distribution, capital, and talent. But Roblox had community, game developers, and cultural momentum. In platform businesses, who got there first and built genuine community usually wins. Meta tried to out-spend its way to dominance, which rarely works in software.

3. Don't Restructure Your Entire Company Around Unvalidated Bets

When Meta reorganized around the metaverse and created the Reality Labs division, it created organizational pressure to succeed regardless of market feedback. Divisions fight for resources and survival. Once Reality Labs was structured as a distinct business unit with thousands of employees, killing it became politically difficult.

The lesson: Keep experimental initiatives smaller and more autonomous. Don't build organizational dependence on unproven markets.

4. Organizational Incentives Shape Decisions

Once you've committed $80 billion and convinced your board and employees that this is the future, admitting you were wrong is politically and professionally costly. This creates a bias toward continuing to invest even when the evidence is clear.

Healthy organizations need structures that make it safe to kill bad bets early. This might mean bonus structures that reward smart failures, leadership that publicly admits mistakes, or governance that regularly re-evaluates big bets.

5. Technology Adoption Is Driven by Convenience, Not Vision

VR is a genuinely amazing technology. It has real applications. But most human behavior is driven by convenience, not capability. Smartphones won not because they're the most powerful computing devices, but because they're always with you. They require minimal setup. They do most things "good enough."

Immersive VR requires friction: you need the hardware, you need to put it on, you need a dedicated space, you can't do other things simultaneously. This friction is a feature killer.

6. Competition Doesn't Care About Your Spending

Meta assumed that having billions of dollars and billions of users would guarantee dominance. But Roblox had 15 years of community building and developer relationships. Fortnite had Epic's game development expertise. You can't buy your way past a competitor with a strong community.

The lesson: In platform businesses, community and developer relationships matter as much as capital. Sometimes more.

VR headsets in 2021 were significantly more expensive than typical smartphones, contributing to their lack of widespread adoption. Estimated data.

The Future of VR: What Actually Happened

It's important to note that VR itself hasn't failed. VR remains valuable for gaming, training, healthcare, and other specialized applications. But consumer social VR—the metaverse as Meta envisioned it—is not the future.

What's actually happening in VR now:

VR Gaming Continues to Grow

VR gaming is legitimate and growing. Games like Beat Saber, Half-Life: Alyx, and VRChat have found audiences. The VR gaming market is projected to exceed $12 billion annually by 2026. But this is a niche market, not a mass market. Maybe 5-10% of consumers are interested in VR gaming. That's much smaller than the metaverse ambition suggested.

VR for Enterprise and Training

Companies use VR for training, data visualization, and remote collaboration. Medical schools use VR to train surgeons. Manufacturers use VR to train technicians. This is a real market worth billions annually, but it's not consumer-facing and it's not social.

AR on Smart Glasses Is the Actual Future

Meta's pivot to AI-enabled AR glasses is smarter than the VR metaverse ever was. Smart glasses that overlay information on the real world, provide AI assistance, and enhance your perception of the physical environment—this is something people actually want. Meta's Ray-Ban smart glasses sales tripling is real validation that this category resonates.

Mixed Reality in Gaming

Apple's Vision Pro and similar devices are exploring mixed reality, blending digital content with the real world. This is more appealing than pure VR for some use cases, but it's still early stage. Price points around $3,500 mean it's still a niche product.

The bottom line: Immersive VR social spaces were never the future. Convenient AI-enhanced devices that augment your daily life are. Meta eventually figured this out. It just took $80 billion and five years to get there.

What This Means for the Broader Tech Industry

Meta's metaverse failure has ripple effects across the entire tech industry.

It's Emboldened AI as the Priority Technology

When Meta's metaverse bet failed, it became clear that AI was more important than immersive environments. Every major tech company has since doubled down on AI investment. Open AI, Anthropic, Google, Microsoft, and yes, Meta itself have all shifted massive resources toward AI research and development.

It's a Cautionary Tale About Over-Conviction

The metaverse failure teaches Silicon Valley an important lesson: even brilliant founders and massive companies can be completely wrong about the future. This should create some humility. Yet it doesn't always. Many companies are currently doubling down on generative AI with the same level of conviction that Meta had about the metaverse.

It's Validated Mobile as the Dominant Platform

For over a decade, tech leaders debated whether mobile was truly the future or whether something else (VR, AR, conversational AI, etc.) would displace it. Meta's pivot back to mobile-first strategies is a strong signal: mobile is the dominant computing platform. Not because it's the most powerful or advanced, but because it's convenient and ubiquitous.

It's Raised Questions About Tech Leadership and Accountability

How does a company lose $80 billion on a bad bet and face minimal consequences? Zuckerberg is still CEO. He remains one of the most powerful voices in tech. The board didn't seriously challenge him until the losses became undeniable. This raises questions about governance, accountability, and how tech companies are structured.

Why This Matters Beyond Meta: Technology Betting and Failure

The metaverse failure matters because it illustrates something fundamental about technology: massive capital and genuine genius are not sufficient to make a bad product successful.

Meta had:

- The world's most advanced AI capabilities

- Billions of dollars to invest

- Billions of users to distribute to

- Genuine hardware and software talent

- A CEO willing to bet the company

And none of it mattered because the fundamental product didn't solve a problem users had.

This is a crucial lesson for every tech company, especially in eras of hype-driven investing (like the current AI wave). Just because something is technically possible doesn't mean people want it. Just because your company has resources doesn't mean you'll win in a new market. Just because a technology is powerful doesn't mean it'll become mainstream.

The companies that win are those that:

- Listen to users, not just experts and analysts

- Iterate quickly based on feedback, not grand plans

- Focus on solving real problems, not building impressive technology

- Test at small scale before betting the company

- Kill bad bets early instead of throwing good money after bad

- Stay humble about their ability to predict the future

Meta eventually did most of these things. But it took an $80 billion loss to learn these lessons.

Looking Forward: What Meta and the Industry Learned

As of early 2025, here's where things stand:

Meta is focusing heavily on AI: The company released Llama 3, is building AI agents, and integrated AI throughout its products. This is where the company believes the future is, and the market seems to agree.

Horizon Worlds might still have a chance on mobile: Whether it succeeds depends on execution, competition, and whether Meta can leverage its distribution advantage effectively. But even if it succeeds, it won't be the world-changing success the metaverse was supposed to be.

Smart glasses with AI are the new frontier: Meta's Ray-Ban glasses sales tripling suggests this category has real potential. Not because they're revolutionary, but because they solve a real problem: letting you access information and AI assistance while staying present in the physical world.

The industry is adjusting expectations: Other companies are watching Meta's metaverse failure closely. It's making investors, founders, and employees more skeptical of massive bets on unproven technologies. This is probably healthy.

But there's a risk of overswinging: Some observers are concluding that VR and AR will never matter. This is almost certainly wrong. The categories have real value. It just turned out that immersive social VR wasn't the key use case everyone thought it was. Gaming, training, professional applications—these remain valid.

The broader lesson: Technology adoption is determined by user behavior, not founder vision. Meta finally learned this. Now the question is whether the rest of the industry learns it without paying the same $80 billion tuition bill.

FAQ

What was the metaverse and why did Meta think it would be the future?

The metaverse was Meta's vision of immersive 3D virtual spaces where people could socialize, work, and play using VR headsets. Meta believed it would become the primary way humans interact online, replacing smartphones as the dominant computing platform. The company invested $80 billion in this vision between 2020 and 2025, building hardware, software, and experiences around this concept. However, the vision never gained mainstream adoption because VR headsets were expensive, uncomfortable, and nobody could articulate a compelling reason to prefer virtual socializing in a headset over existing communication tools like messaging, video calls, or social apps.

How much money did Meta actually lose on the metaverse and Reality Labs?

Meta's Reality Labs division lost approximately **

Why did Meta pivot from VR to mobile for Horizon Worlds?

Meta realized that the core problem with the metaverse strategy was the reliance on VR hardware. VR headsets are expensive ($300-1500), require setup and maintenance, cause motion sickness in some users, and isolate you from the physical world while using them. Mobile platforms avoid all these friction points. By moving Horizon Worlds to mobile, Meta could compete with proven platforms like Roblox and Fortnite while leveraging its unique advantage: the ability to promote the app to 1.2 billion daily active users across Facebook and Instagram. Mobile social gaming is a mature, successful category where Meta actually has a chance to compete effectively.

What happened to the VR games and apps Meta had invested in?

Meta shut down or moved into "maintenance mode" several VR-focused projects and acquisitions. Most notably, Supernatural, a VR fitness app that Meta acquired for over $100 million, stopped producing new content and shifted to maintenance-only. Several VR game studios that Meta had built or acquired were dissolved entirely. The company laid off roughly 1,500 employees from Reality Labs, primarily those working on metaverse experiences, avatar systems, and VR game development. This represented about 10% of the division's workforce and signaled that Meta was serious about abandoning the consumer social VR strategy.

Is VR completely dead now?

No, VR isn't dead, but it's not the mainstream consumer platform that Meta envisioned. VR remains valuable for gaming, professional training, medical education, and enterprise applications. The VR gaming market is legitimate and growing to $12+ billion annually. However, immersive social VR—the idea that humans would spend hours in virtual worlds with avatars—turned out to be a niche interest at best. What's actually succeeding are VR games that offer compelling gameplay experiences, and enterprise applications solving specific professional problems. The lesson is that VR has value, but for narrower use cases than the metaverse narrative suggested.

What is Meta focusing on now instead of the metaverse?

Meta has pivoted hard toward artificial intelligence and AI-enabled smart glasses. The company released Llama 3, an open-source large language model, and is building AI agents and AI-powered features throughout its apps. More significantly, Meta's Ray-Ban smart glasses with AI capabilities have seen sales triple in the past year, becoming "some of the fastest growing consumer electronics in history" according to CEO Mark Zuckerberg. These AI-enabled glasses let users get information, translation, and AI assistance while staying present in the physical world—a compelling use case that VR's immersive spaces never quite achieved.

Why did Meta's leadership stick with the metaverse strategy for so long despite clear signs of failure?

Once Meta committed $80 billion to the metaverse strategy and reorganized the entire company around it, organizational incentives created pressure to continue investing. Reality Labs became a distinct business unit with thousands of employees, making it politically difficult to kill. Middle managers and engineers were evaluated on metaverse adoption targets. CEO Mark Zuckerberg was personally identified with the vision, making challenges to it feel like personal criticism. Additionally, sunk cost fallacy likely played a role: the company had invested so much that abandoning it felt like admitting massive failure. It wasn't until external pressure from investors, analyst scrutiny, and undeniable market failure that the company seriously re-evaluated the strategy.

Could Horizon Worlds succeed as a mobile social gaming platform?

It's possible but challenging. Roblox and Fortnite have massive heads-start in this category with billions of dollars in annual revenue, established developer communities, and strong network effects. Horizon Worlds starts with brand damage (associated with the failed metaverse) and lost talent from the Reality Labs restructuring. However, Meta does have genuine advantages: 1.2 billion daily active users it can promote to, integration with Facebook and Instagram, and substantial resources. The company could build a successful social gaming platform, but it likely won't achieve the transformative scale that the metaverse was supposed to reach. Success would mean 10-50 million users, not billions.

What's the broader lesson from Meta's metaverse failure for other tech companies?

The key lesson is that vision, capital, and talent are insufficient without genuine user demand and product-market fit. Even the world's largest tech company with massive resources cannot force adoption of a product that doesn't solve a compelling user problem. Other lessons include: (1) validate product concepts at small scale with real users before betting the company, (2) listen to user behavior more than expert predictions, (3) organizational structures should make it easy to kill bad bets rather than institutionalizing them, (4) convenience often beats capability—people choose what's easy, not what's most powerful, and (5) competitors with strong community relationships and developer networks can outcompete wealthier players. These lessons are particularly relevant in the current AI boom, where massive capital is flowing into applications whose market success remains unvalidated.

The Bottom Line

Meta's metaverse collapse is one of the most expensive business failures in tech history. $80 billion invested. 300,000 users at peak. It's a stark reminder that even the world's most powerful companies can be completely wrong about the future.

But there's something important happening beneath the failure. Meta didn't just abandon the metaverse. The company is building something that might actually matter: AI-enabled smart glasses that augment your everyday life with intelligent information and assistance. Ray-Ban smart glasses sales are tripling. Llama 3 is competitive with the best open-source AI models. AI agents are being integrated throughout Meta's products.

This is the real lesson. The future isn't about escaping into virtual worlds. It's about having intelligent technology enhance the real world you're already in.

Meta eventually figured this out. It just cost them eighty billion dollars.

For founders and tech leaders watching this, the question is: How much are you willing to spend before admitting a strategy isn't working? How long will you let organizational incentives and sunk costs drive decisions? And most importantly, are you actually listening to what users want, or just building what you think they should want?

The metaverse was the product of amazing engineering, unlimited capital, and genuine conviction. None of it mattered because users didn't want it.

That's the real story here.

Key Takeaways

- Meta lost approximately $80 billion on its Reality Labs and metaverse ambitions between 2020 and 2025, with Horizon Worlds peaking at only 300,000 monthly active users

- The core problem: immersive VR social spaces required expensive hardware, caused isolation from the physical world, and never solved a compelling user problem

- Meta pivoted Horizon Worlds to mobile-first gaming to compete with Roblox and Fortnite while leveraging its 1.2 billion daily active users across Facebook and Instagram

- The company's strategic focus has shifted entirely to AI-enabled smart glasses and large language models, where Ray-Ban sales are tripling and represent genuine market validation

- The failure illustrates crucial lessons for tech leaders: vision without user validation fails, organizational incentives can perpetuate bad bets, and convenience beats capability in technology adoption

Related Articles

- OpenAI's 850B Valuation Explained [2025]

- Zuckerberg's Testimony in Social Media Addiction Trial: What It Reveals [2025]

- Edge AI Models on Feature Phones, Cars & Smart Glasses [2025]

- Zuckerberg Takes Stand in Social Media Trial: What's at Stake [2025]

- Google I/O 2026: 5 Game-Changing Announcements to Expect [2025]

- RentAHuman: How AI Agents Are Hiring Humans [2025]

![Meta's Metaverse Collapse: Why VR Lost to Mobile and AI [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/meta-s-metaverse-collapse-why-vr-lost-to-mobile-and-ai-2025/image-1-1771605650333.jpg)