The Contradiction at the Heart of Smart Glasses

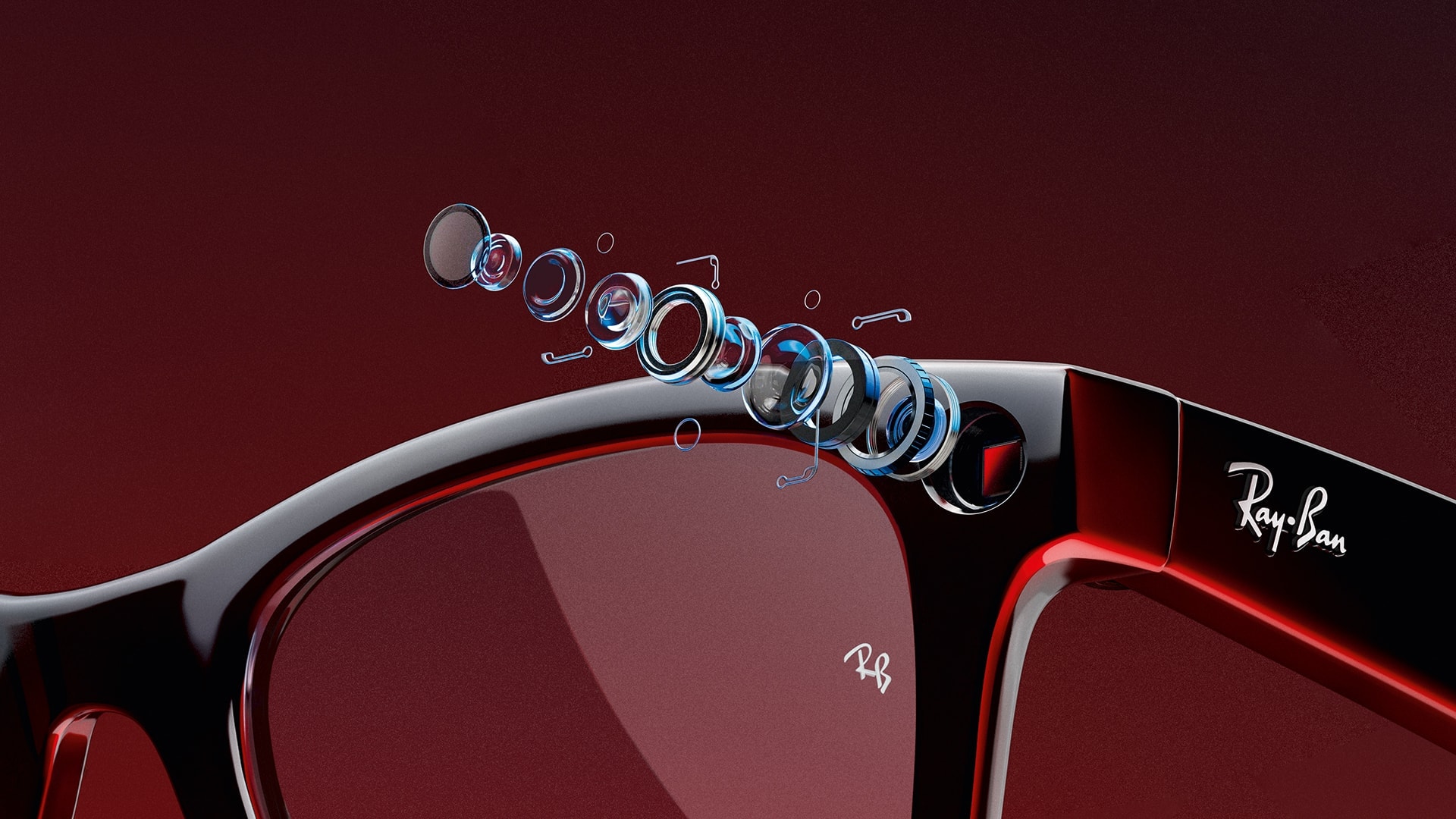

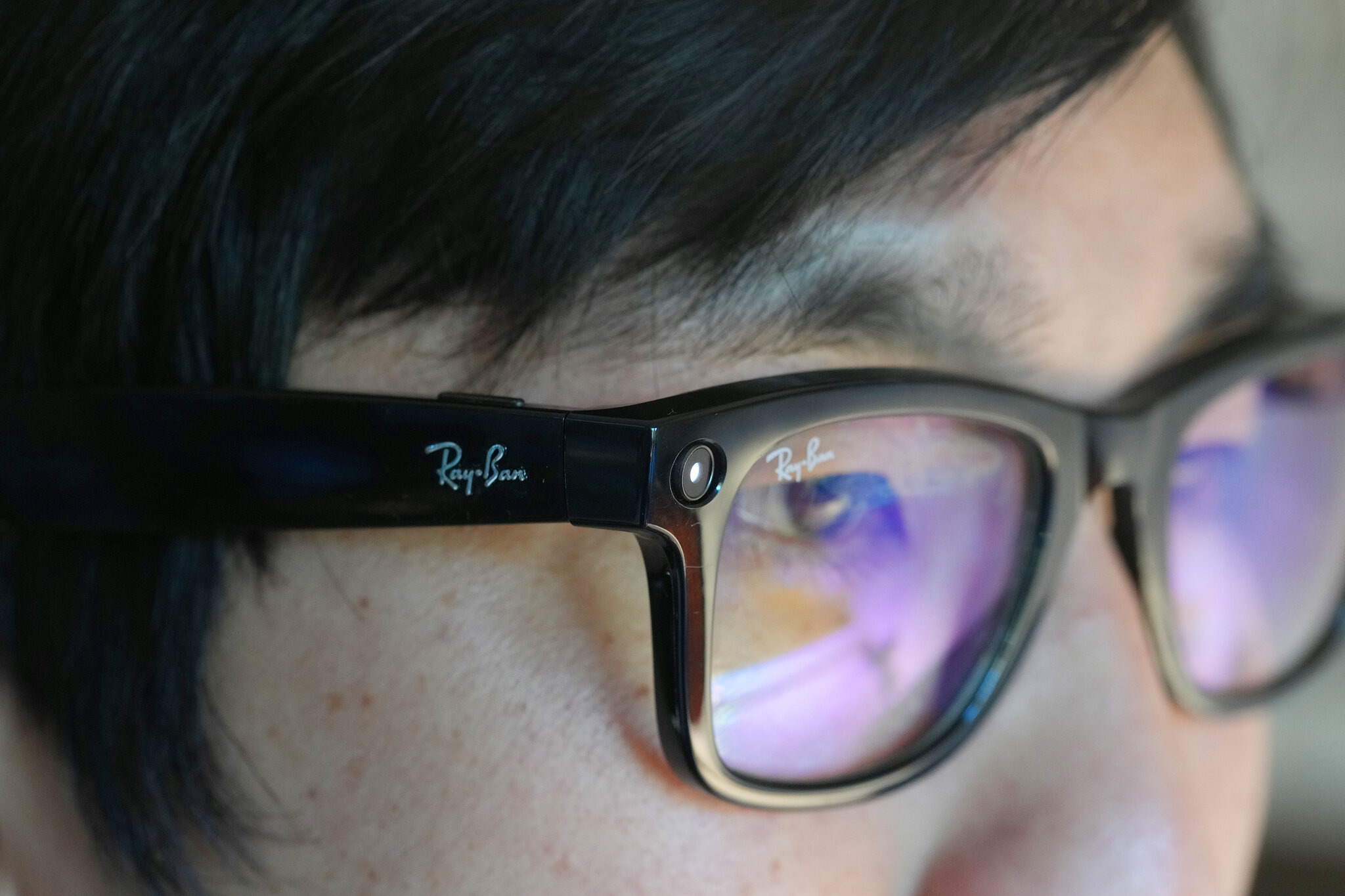

There's a fundamental tension baked into Meta's smart glasses strategy that nobody seems willing to discuss openly. The hardware is genuinely impressive. I've tested it. The cameras are sharp, the display works, and the whole package feels natural on your face. But that's precisely the problem.

You see, smart glasses work because they're discreet. They don't scream "I'm recording you" the way a phone held up to your face does. That invisibility is their greatest selling point. People can wear them at dinner, at the gym, at protests, at their kids' school events, and most folks around them won't even notice. The glasses look normal. They blend in. That's the magic that makes them useful.

But here's where the Meta situation gets complicated. That same invisibility that makes the hardware brilliant is also what makes facial recognition features genuinely terrifying. Meta has reportedly been exploring facial recognition capabilities that would allow users to identify strangers in real-time by comparing their faces against public Instagram accounts. According to reporting, Meta considered rolling out this feature "during a dynamic political environment" specifically because privacy advocates would be distracted. That's not a bug in Meta's thinking. That's a feature of how the company operates.

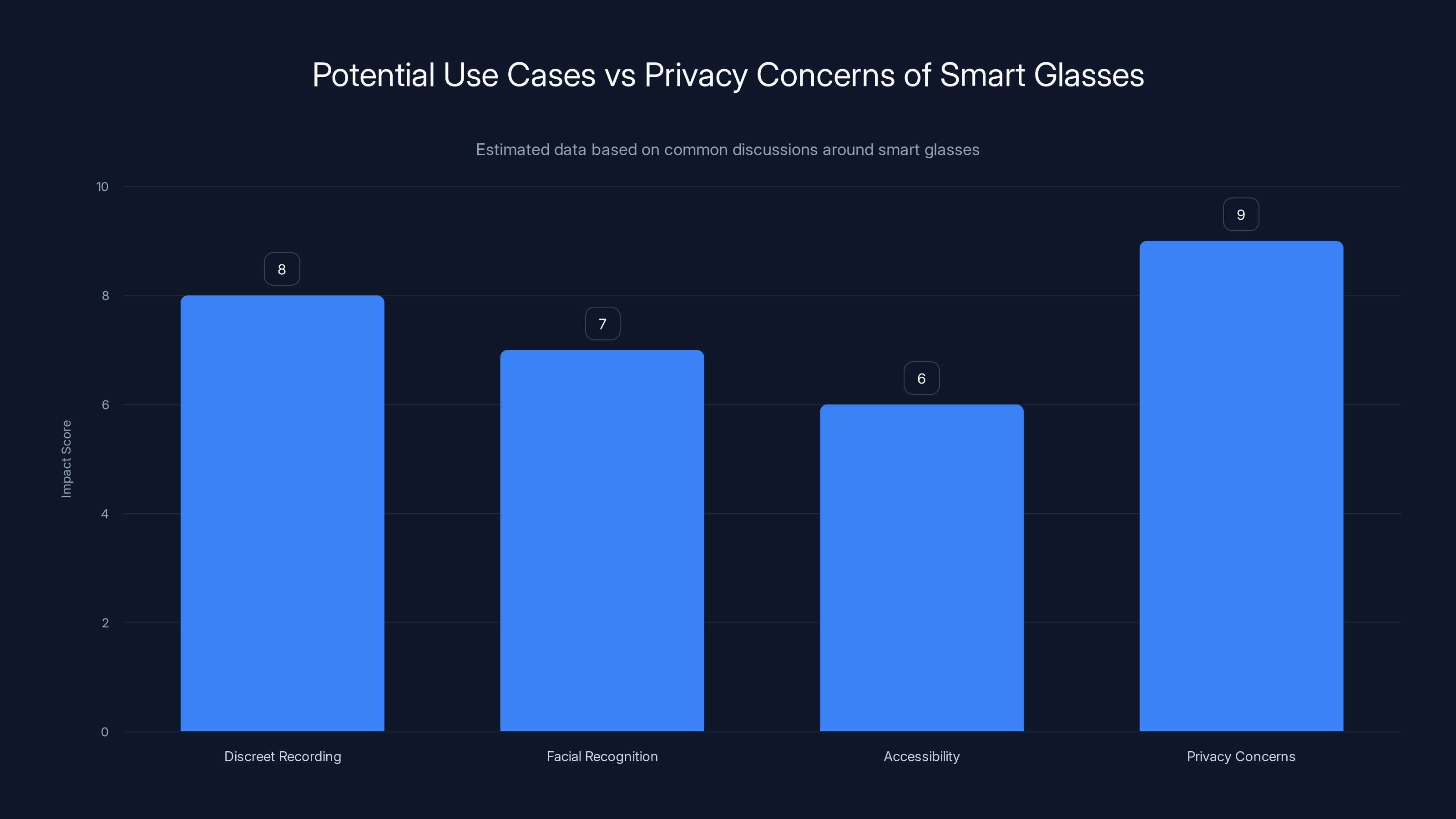

When you combine discrete recording devices with powerful facial recognition, you don't get innovation. You get a surveillance tool that looks exactly like regular eyewear. And suddenly, all those legitimate use cases people talk about—helping blind users navigate the world, remembering names at conferences, assisting with accessibility—become cover stories for a technology that could fundamentally change how public spaces work.

The conversation around smart glasses usually gets stuck in false equivalencies. "Your phone has a camera," defenders say. "The government already uses facial recognition." "CCTV cameras are everywhere." All true. But none of that addresses why smart glasses are uniquely dangerous. The difference is visibility and consent. When someone pulls out their phone to record you, you know it. Security cameras announce themselves. But someone in regular-looking glasses? You'll never know they're documenting your face, your movements, your companions, and your location.

Understanding the Privacy Problem

Let's be precise about what makes smart glasses different from existing surveillance infrastructure. The problem isn't the technology itself. Facial recognition has legitimate applications. The problem is the deployment context and who controls the data.

Consider traditional CCTV systems. They're stationary. You know they exist. They're monitored by organizations with accountability structures (theoretically). If law enforcement wants to access footage, there are procedures, warrants, legal frameworks. Imperfect? Absolutely. But there are at least some guardrails.

Now imagine millions of people walking around with cameras and facial recognition running continuously on battery power. Imagine someone in a coffee shop who's upset about an ex being able to scan their face and instantly know their location, see their public photos, and potentially identify their friends. Imagine protesters being identified at demonstrations. Imagine someone with an abusive ex or stalker having that kind of surveillance capability. Imagine a coworker using it to identify and track someone.

Meta's response to these concerns essentially amounts to "we'll add a privacy light." The problem is, that's theater. A 404 Media investigation demonstrated that a $60 modification can disable the light without affecting recording capability. Users have reported the light simply stopping working on its own. These aren't edge cases. They're fundamental design weaknesses in a system where the stakes are extremely high.

The real issue is that Meta is building infrastructure for pervasive surveillance and wrapping it in consumer-friendly language. A feature that "helps you remember names" is also a feature that lets you document everyone you meet without their knowledge. A tool that "assists with accessibility" is also a tool that can identify protesters, track movement patterns, and create permanent records of people's locations and associations.

There's also the business model problem. Meta makes money by collecting data about people's behavior, interests, and relationships. They have every incentive to extract as much information as possible from smart glasses. They've already built recommendation systems trained on billions of hours of social data. Adding facial recognition and real-world video to that system creates unprecedented opportunities for behavior prediction and manipulation.

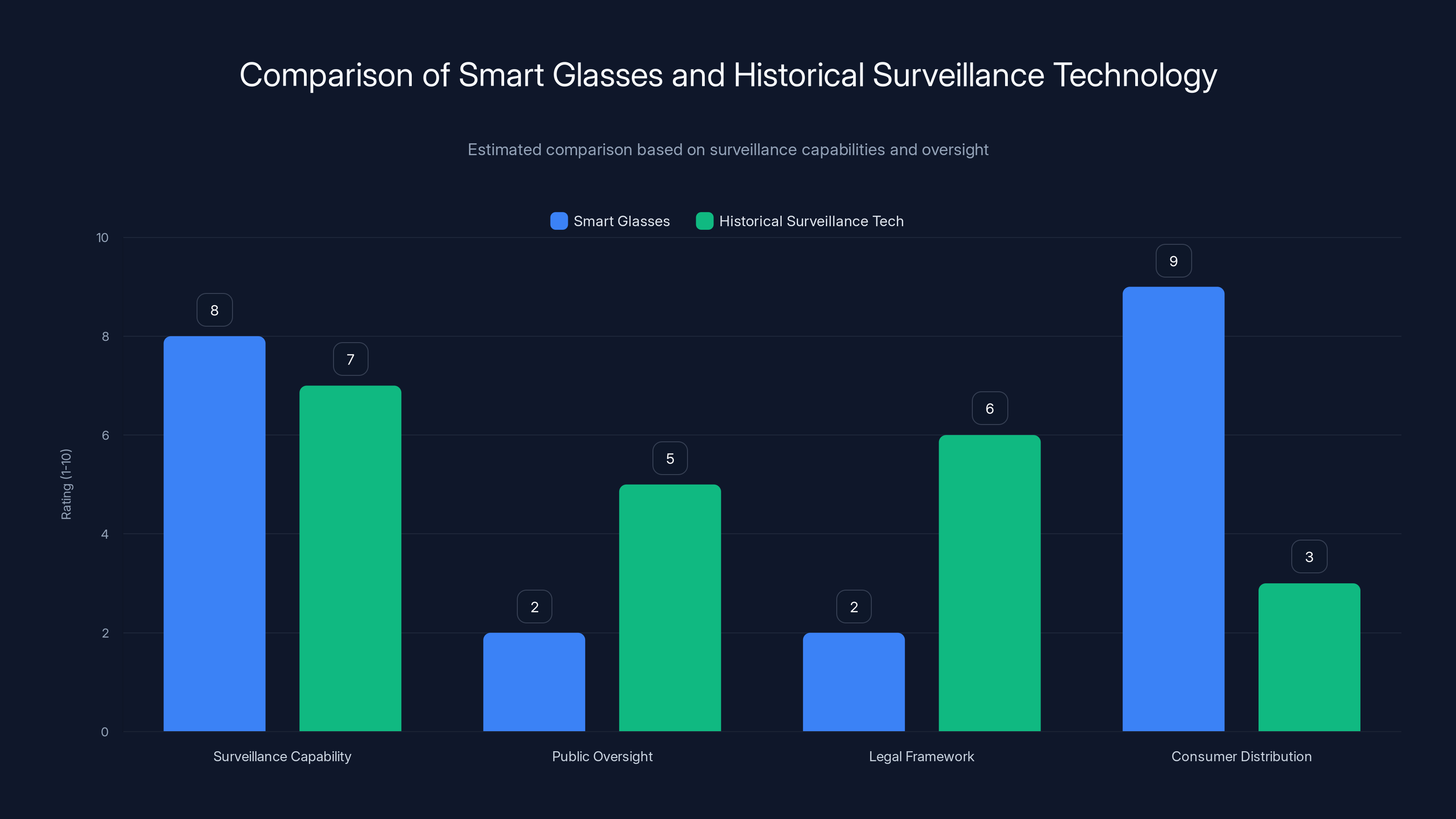

Smart glasses offer higher consumer distribution and surveillance capabilities but lack public oversight and legal frameworks compared to historical surveillance technology. (Estimated data)

The Accessibility Argument and Its Limitations

I want to be fair here. Legitimate accessibility benefits exist. I've spoken with blind and low-vision users who genuinely say Meta's glasses have improved their lives. The ability to identify objects, read text, and navigate spaces with AI assistance creates real value for people with visual disabilities.

But here's the thing: accessibility benefits and surveillance risks aren't mutually exclusive. You can design technology that helps people with disabilities without simultaneously creating powerful surveillance infrastructure. It requires different design choices.

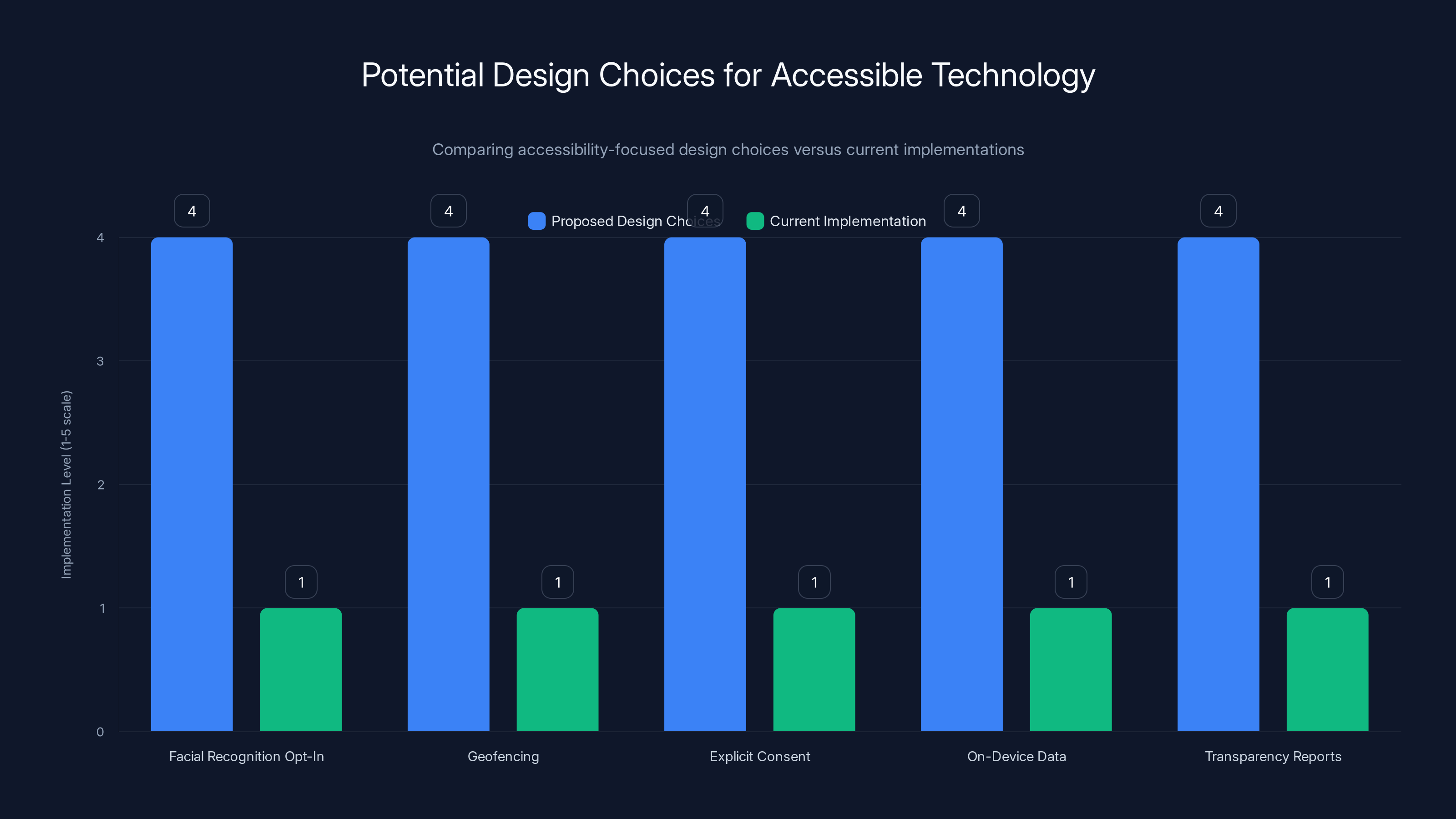

You could limit facial recognition to people who have explicitly opted in. You could geofence the feature to private spaces only. You could require explicit consent every single time the feature activates. You could build the system so data stays on-device rather than uploading to Meta's servers. You could create transparency reports showing how the feature is used. None of these exist in Meta's current or proposed system.

The accessibility argument becomes a shield for broader deployment. "This helps blind people, so we need this feature everywhere." But that's not actually true. You can build accessibility features without building mass surveillance infrastructure. The two aren't synonymous.

Consider how screen readers work. They're accessibility technology that has been deployed extensively without creating surveillance problems because they don't collect behavioral data about third parties. They don't identify strangers. They don't track movement. They help users but don't compromise the privacy of people around them.

Meta could theoretically design smart glasses the same way. But they haven't. Because that's not what Meta is actually building. Meta is building a data collection device. The accessibility features are real benefits. But they're also marketing material for something much larger.

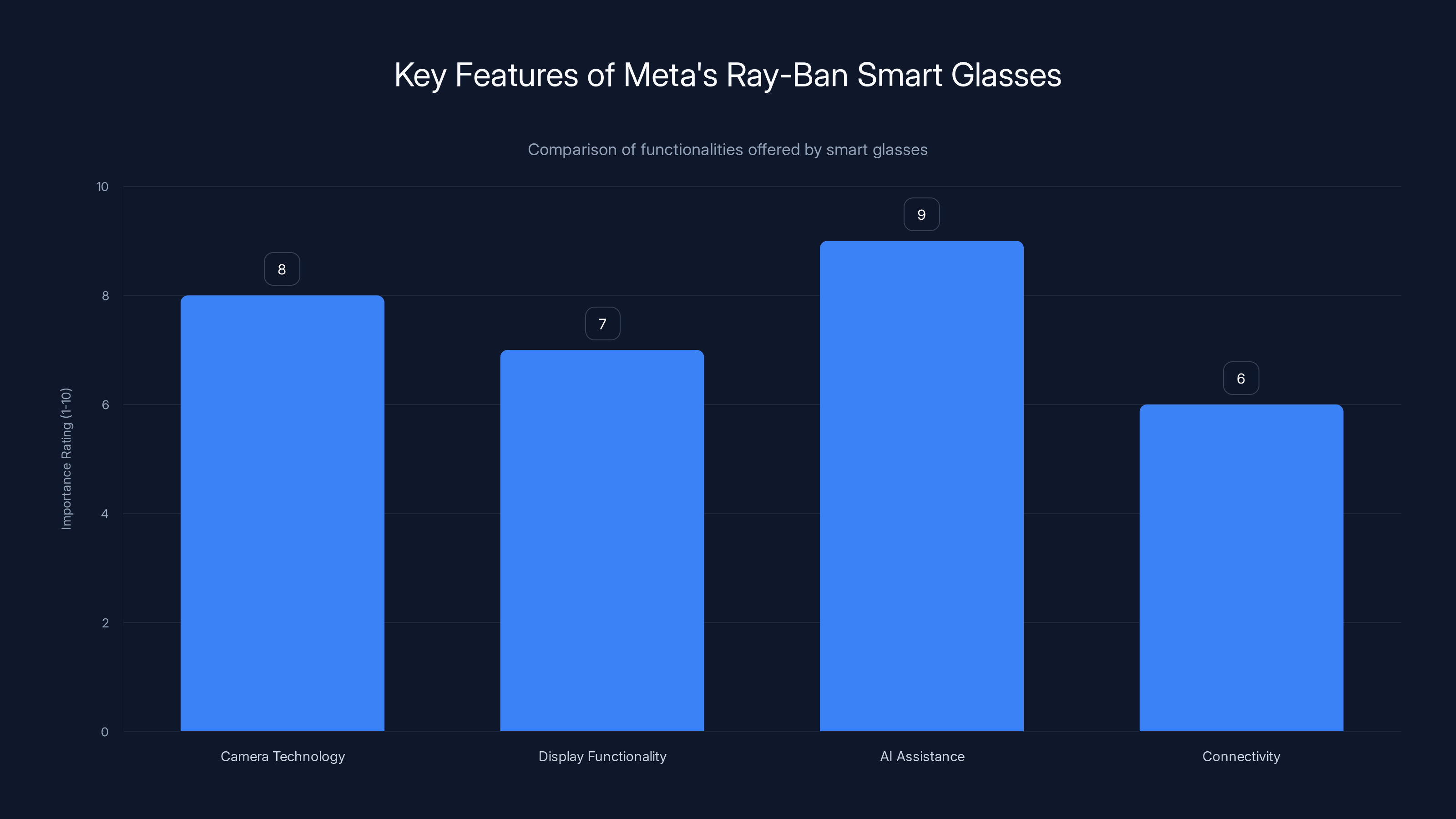

Meta's Ray-Ban smart glasses emphasize AI assistance and camera technology, rated highest in importance for user experience. Estimated data.

The "Glasshole" Problem and Social Backlash

There's a reason Google Glass failed. It wasn't technical limitations. It was social rejection. People instinctively understood that being around someone with a head-mounted camera was uncomfortable, and they responded accordingly. Early Google Glass adopters got physically confronted. People called them "glassholes." There was real social friction.

Meta's Ray-Ban glasses haven't faced the same level of backlash, partly because they look more normal and partly because Meta launched them with more marketing finesse. But the underlying problem hasn't been solved. It's just been temporarily papered over.

I've worn these glasses in public, in crowds, at outdoor events. Almost nobody notices them. And that's the problem. Invisibility removes the social friction that previously limited surveillance technology adoption. When everyone around you knows you're being recorded, they can object. They can ask you to stop. They can choose not to be around you. But if most people don't even realize they're being recorded, that social feedback mechanism vanishes.

There's also the hammer-wielding metaphor that's emerged in online discussions. A woman in New York was celebrated as a hero when she physically removed Ray-Ban Meta glasses from someone's face and smashed them. That story circulates online because it taps into something real: the understanding that surveillance tools that look like ordinary objects are categorically more dangerous than ones that announce themselves.

Will that become common? Probably not. Most people won't notice the glasses. But the fact that it can happen, that public opinion supports it when it does, indicates a deeper recognition that smart glasses represent a new category of threat.

The Timing Question and Political Manipulation

This is where the New York Times reporting becomes particularly damning. Meta wasn't just considering facial recognition. Meta was considering rolling it out "during a dynamic political environment" specifically because privacy advocates would be distracted.

Let me be explicit about what that means. Meta was strategically planning to deploy powerful surveillance technology at a moment when public attention was focused elsewhere and opposition would be fragmented. That's not a coincidence or a misunderstanding. That's deliberate strategy.

This reveals something important about how Meta operates. The company doesn't think privacy advocates are right. It doesn't think the concerns are illegitimate. It thinks they're an obstacle to be managed through timing and distraction. The solution isn't to address the concerns. It's to deploy the feature before the concerns can coalesce into action.

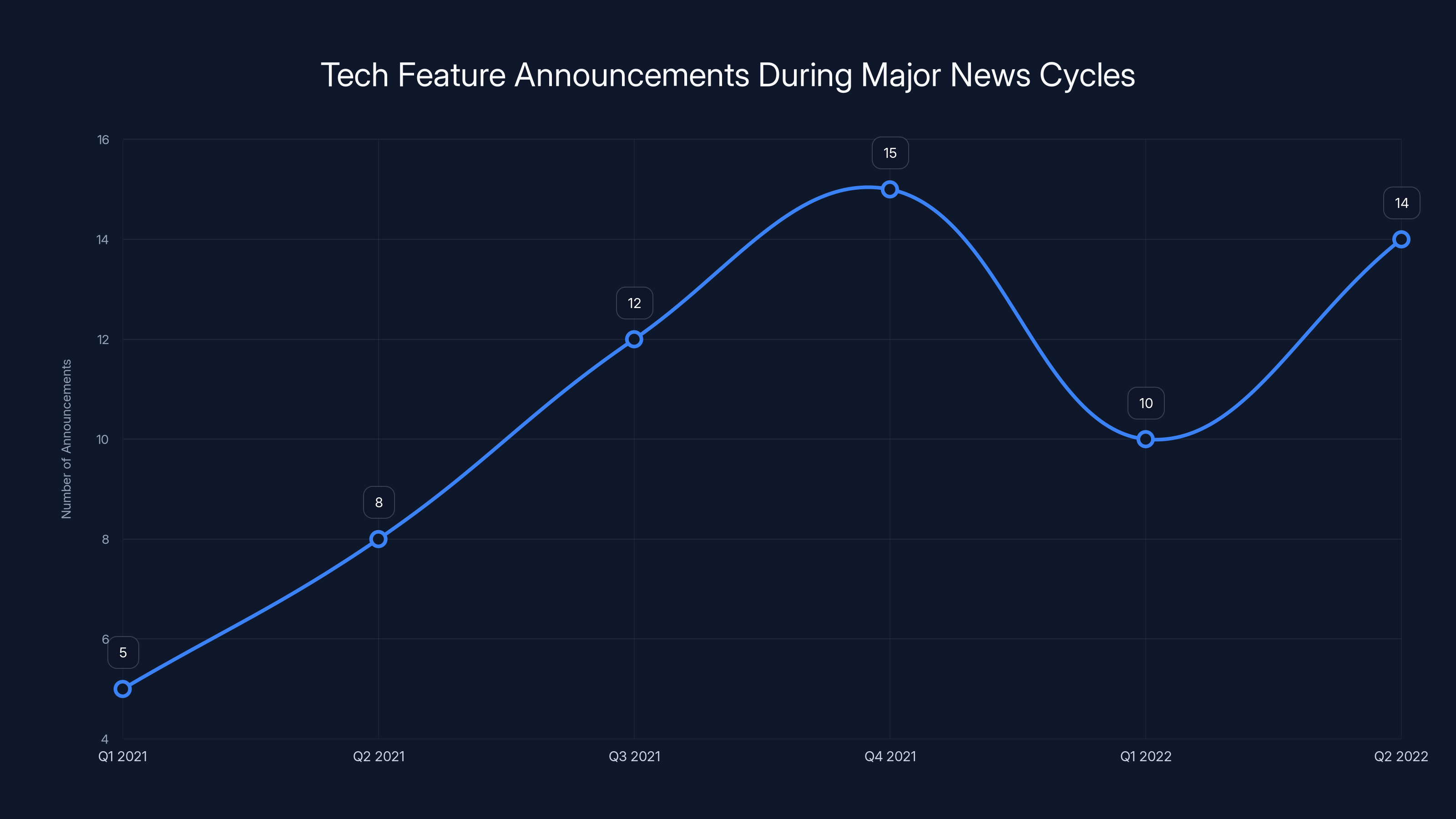

History shows this is an effective strategy. Major tech companies have repeatedly announced controversial features during major news cycles, holidays, or periods when regulatory attention was focused elsewhere. It's become standard practice. And it usually works. By the time people fully understand what happened, the technology is already deployed and the conversation shifts to managing the damage rather than preventing it.

But this particular instance is notable because we have the internal thinking exposed. Meta didn't want to navigate the political environment transparently. It wanted to use the political environment as cover. That's a choice that reveals a lot about how the company thinks about privacy, consent, and public interest.

The chart compares proposed design choices that enhance accessibility without compromising privacy against current implementations. Estimated data suggests a significant gap between ideal and current practices.

Comparing Smart Glasses to Historical Surveillance Technology

There's a useful historical parallel here. In the 1960s and 70s, law enforcement agencies deployed hidden recording technology in ways that seemed revolutionary at the time. Undercover agents could wear wires. Police could install surveillance equipment in seemingly innocent locations. The technology was powerful and useful for law enforcement purposes.

But society eventually decided that unfettered surveillance power was dangerous enough that legal frameworks needed to be put in place. You can't just record someone without their knowledge. You need warrants. You need probable cause. You need oversight. Those frameworks exist because people understood that surveillance technology, if unconstrained, enables abuse.

Smart glasses are different because they're consumer devices rather than law enforcement tools. But the principle is identical. You're distributing powerful recording and identification technology to millions of people with minimal oversight, no requirement for consent, and no meaningful accountability for misuse.

The assumption that market forces will prevent abuse has been tested repeatedly in tech history and failed repeatedly. Companies pushed tracking cookies until regulation forced them to disclose them. Companies harvested behavioral data until people started understanding the scope of collection. Companies deployed algorithmic systems that produced discriminatory outcomes until lawsuits exposed the failures. In every case, the company's internal incentives aligned with maximizing data extraction, not minimizing harm.

Meta is no exception. The company's business model depends on collecting behavioral data. Facial recognition and real-time identification represent unprecedented opportunities for data collection. The idea that Meta will voluntarily constrain those capabilities is inconsistent with how the company has operated for the past fifteen years.

Technical Vulnerabilities and Circumvention

Beyond the fundamental privacy concerns, there are significant technical vulnerabilities in Meta's approach to privacy protection. The most obvious is the physical tampering vulnerability with the privacy light. But there are others.

First, there's the data transmission problem. Meta claims that facial recognition would work by comparing faces against public Instagram accounts. That sounds limited. But it requires sending facial data somewhere—either to Meta's servers or to a local model that was trained on massive datasets of faces. Both approaches create vulnerability. Local models can be reverse-engineered. Cloud transmission can be intercepted or analyzed.

Second, there's the feature creep problem. Meta might launch facial recognition with stated limitations. But features expand. Over time, the company could add capabilities, extend the scope, or change how data is used. They have a track record of doing exactly this. What starts as a limited feature becomes broadly deployed.

Third, there's the data persistence problem. Even if Meta's servers don't permanently store facial data, the data flows through systems where it can be logged, indexed, and analyzed. The existence of the data creates a permanent record that can later be accessed or misused.

Finally, there's the regulatory evasion problem. Meta might deploy facial recognition in ways designed to skirt existing privacy laws. The European Union's regulations on biometric data are relatively strict, for example. But there are jurisdictions with fewer restrictions where Meta could deploy more aggressive versions of these features first, test them, and then push to expand their use.

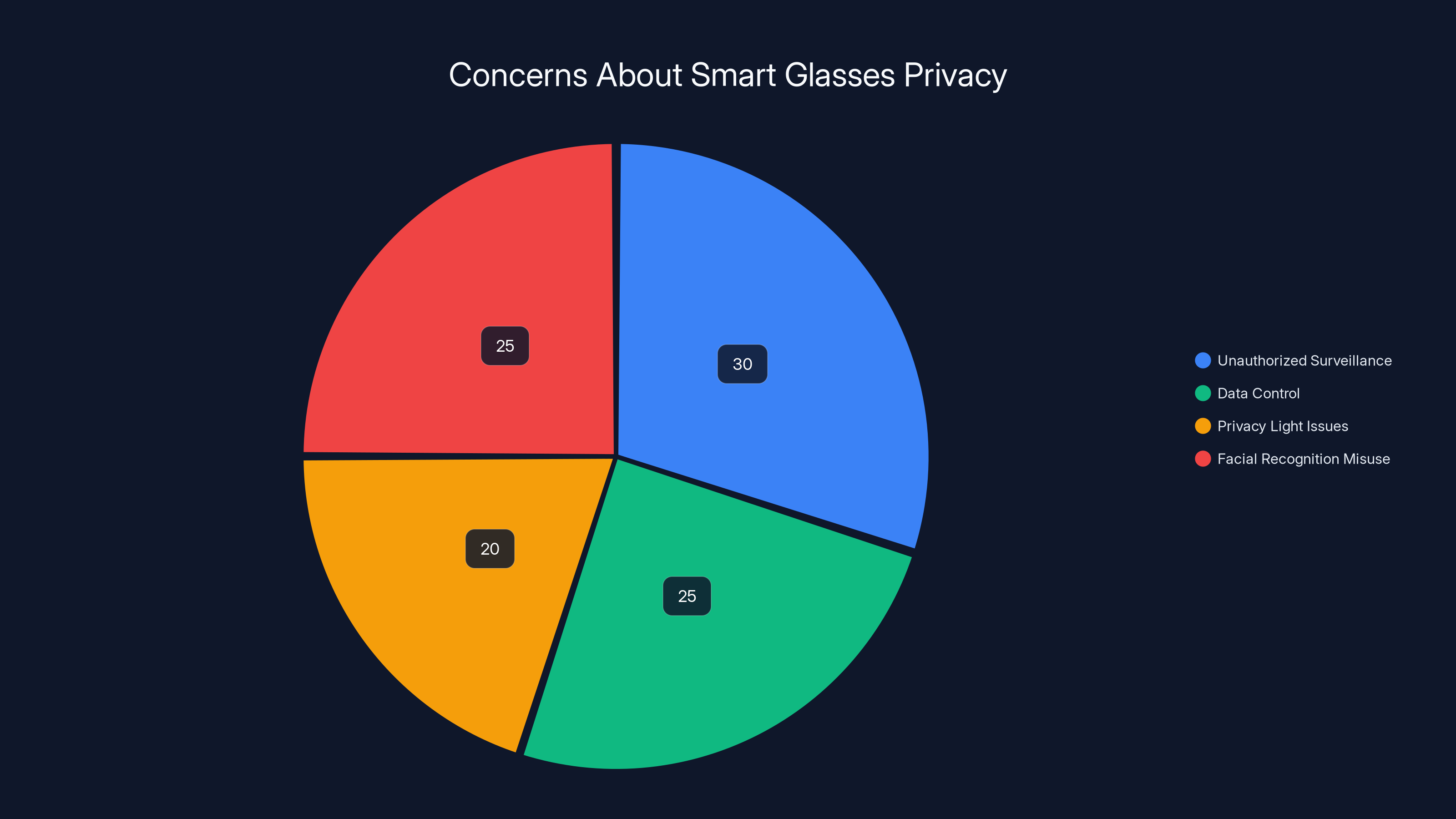

Unauthorized surveillance and facial recognition misuse are major concerns, each accounting for 25-30% of privacy issues related to smart glasses. Estimated data.

The Competitive Dynamic and Race-to-the-Bottom Effects

One underappreciated aspect of the smart glasses debate is how competition affects technology deployment. If Meta launches facial recognition and sees success (measured in user engagement, data collection, or advertising efficacy), competitors will follow. Apple, Google, and others are developing smart glasses. If one company deploys powerful surveillance capabilities, the others face pressure to do the same or risk losing market position.

This creates a race-to-the-bottom dynamic where the company willing to deploy the most invasive version of a technology gains competitive advantage. Privacy becomes a competitive disadvantage. Companies that voluntarily limit surveillance capabilities lose to companies that don't.

History shows this pattern repeating constantly in tech. It's not unique to Meta. But it's important to understand because it explains why even well-intentioned companies eventually deploy invasive features. Individual corporate restraint is unstable when competitors don't exercise the same restraint.

The solution to this problem requires regulatory frameworks that level the playing field. If all companies face the same legal constraints around facial recognition and surveillance, then deploying those capabilities doesn't confer competitive advantage. But without regulation, the competitive dynamic pushes toward maximum surveillance.

Meta isn't the villain here simply because Meta is uniquely evil. Meta is the villain because Meta's business model incentivizes surveillance and the competitive dynamics incentivize racing to the bottom. Those are structural problems that require structural solutions.

Regulatory Responses and Legal Frameworks

Some jurisdictions are starting to put rules in place around facial recognition. The European Union's AI Act includes provisions for regulating biometric systems. Some US states have restricted law enforcement use of facial recognition. But there's a gap between law enforcement restrictions and consumer device regulation.

Most frameworks focus on the government using facial recognition. Much less attention has been paid to consumer devices deploying facial recognition in public spaces. This creates a loophole where companies can deploy surveillance infrastructure that would be illegal for governments to deploy.

There are a few possible regulatory approaches. The simplest is to ban facial recognition in consumer devices deployed in public spaces. That's drastic but addresses the problem directly. More moderate approaches might require explicit consent, transparency reporting, or limitations on data retention. Some frameworks might distinguish between facial recognition used for accessibility and facial recognition used for identification.

But any effective regulation requires government action that currently doesn't exist. And tech companies have strong incentives to prevent that regulation or weaken it if it comes. Meta has already invested heavily in lobbying and PR to shape the regulatory environment around AI and facial recognition.

The challenge is that smart glasses are genuinely useful technology with legitimate applications. A complete ban would prevent beneficial uses. But allowing unconstrained deployment creates surveillance risks that are difficult to manage retroactively. The regulation needs to be specific enough to prevent abuse while preserving beneficial uses.

Smart glasses offer discreet recording and accessibility benefits, but privacy concerns, especially with facial recognition, are significant (Estimated data).

The Design Alternative: Privacy-First Smart Glasses

Here's the thing that gets lost in discussions of smart glasses: the privacy problems aren't inevitable. They're design choices. You could build smart glasses that provide useful features without creating surveillance infrastructure.

Consider what a privacy-first approach would look like. All processing happens on-device. No data streams to company servers unless explicitly requested and authorized by the user. Facial recognition, if available, requires explicit activation and consent every single time it's used. No continuous background processing. No ambient listening. No location tracking. Data is deleted immediately after use unless the user explicitly chooses to save it.

That's not technically infeasible. Modern mobile processors are powerful enough to run sophisticated AI models locally. The battery hit would be noticeable but manageable. The user experience might be slightly slower. But from a privacy perspective, it would be transformative.

Why doesn't Meta build smart glasses this way? Because it would eliminate the primary source of value to Meta. The company can't build a surveillance infrastructure that also maximizes data privacy. Those goals are fundamentally in conflict.

Meta could theoretically sell glasses that prioritize privacy and just accept smaller revenues from a narrower data stream. But that's not how public corporations operate. They optimize for shareholder value, which means maximizing data extraction and advertising reach. Privacy-first design doesn't maximize those metrics.

If smart glasses are going to be deployed widely, they probably need to be built by companies whose business models don't depend on extracting behavioral data. Or they need to be built under regulatory frameworks that require privacy-first design. Those are the only paths to smart glasses that don't become mass surveillance infrastructure.

The Psychological Angle: Why We're Normalizing the Creepy

One psychological dimension worth examining is how we normalize invasive technology. People adjust to surveillance incrementally. Each new capability seems like a small step. But cumulatively, they add up to something unrecognizable.

We already live in a highly surveilled world. Your phone tracks your location constantly. Your internet service provider monitors your browsing. Retailers track your purchases. Social media platforms monitor your behavior. Security cameras are everywhere. Most people are aware of this and have made some peace with it. The novelty has worn off.

Into that context, smart glasses with facial recognition don't seem like a categorical shift. They're just another surveillance layer added to existing infrastructure. "What's one more camera?" people think. "I'm already tracked everywhere."

But that's the wrong way to think about it. The cumulative effect of surveillance is qualitatively different from any individual component. You don't actually live in the panopticon until all the pieces exist. Adding the final pieces transforms the entire system. Smart glasses with facial recognition might be that final piece.

Once that infrastructure exists, it's nearly impossible to remove. People get accustomed to having access to identification data. Law enforcement becomes dependent on it. Advertisers optimize campaigns around it. Removing it would require going backward, which is politically and technically difficult. So once deployed, surveillance infrastructure tends to persist and expand indefinitely.

That's why the timing matters. That's why the deliberate strategy to deploy during a moment of political distraction is so concerning. Because once deployed, the infrastructure will almost certainly be permanent. And once it's permanent, it becomes a tool for control and manipulation that's difficult to resist.

Estimated data shows an increase in tech feature announcements during periods of major news cycles, suggesting strategic timing to minimize public scrutiny.

What Users Should Know About Current Smart Glasses

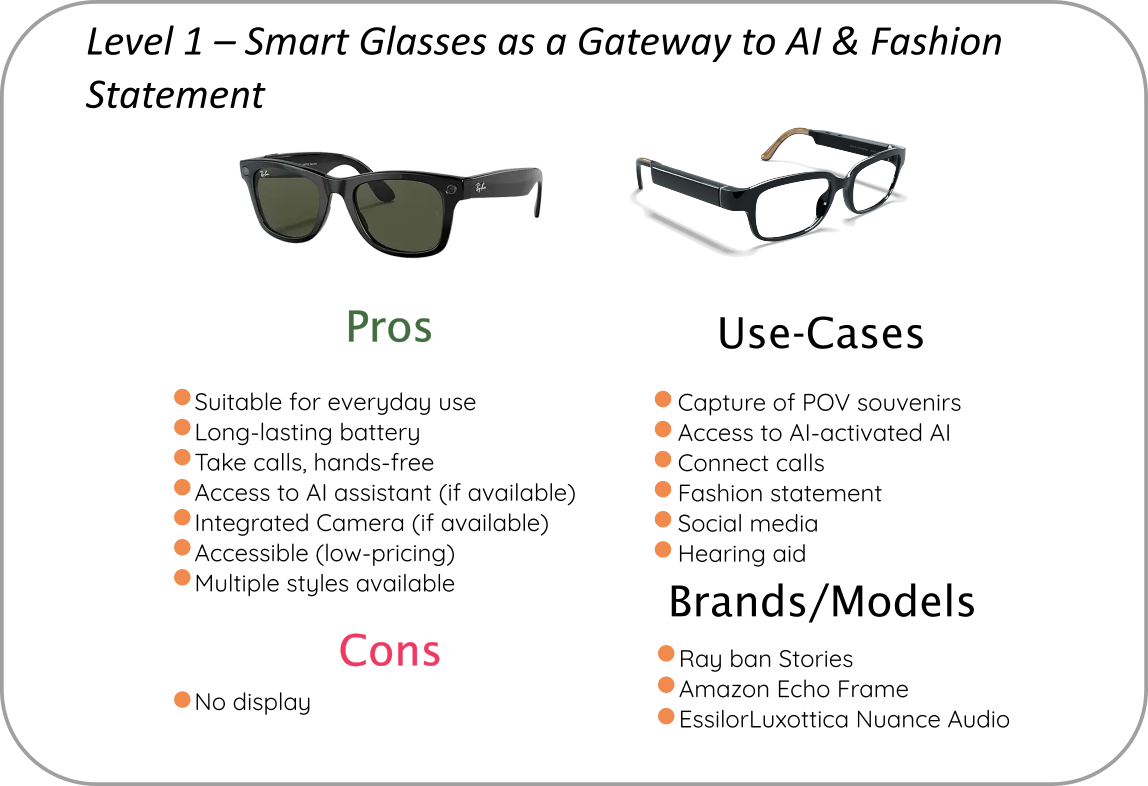

If you're considering purchasing Meta Ray-Ban smart glasses, here's what you should understand about the current capabilities and risks.

First, the glasses are already cameras. They record video and audio in ways that create permanent records. The fact that facial recognition isn't deployed yet doesn't mean they're not surveillance devices. They're already collecting data about what you look at, where you go, and who you're around.

Second, the privacy light is security theater. It provides some protection, but it's not fool-proof. Assume that the glasses can record in situations where you might think they can't.

Third, the data Meta collects from these glasses is currently being analyzed to improve their AI systems and train recommendation algorithms. You're voluntarily contributing to the development of more powerful surveillance infrastructure.

Fourth, regulatory frameworks around smart glasses don't exist in most places. If you wear these glasses in public, you might be breaking laws in jurisdictions that have banned personal recording devices without consent. You should understand your local legal environment.

Fifth, social consequences exist. People who notice the glasses might react negatively. You might face confrontation or exclusion. The social license for these devices is fragile.

Sixth, assume that future capabilities (like facial recognition) will eventually be available. If you're uncomfortable with those possibilities, buying in now is choosing to live with them.

The Path Forward: What Should Actually Happen

So where does this leave us? If smart glasses are inevitable, if companies like Meta will continue developing them, if the technology is genuinely useful for some applications, what should happen?

First, regulation needs to establish clear boundaries. Facial recognition in consumer devices should require explicit consent, be limited to specific use cases, and include transparency reporting. Governments should ban certain uses outright—using facial recognition to identify protest participants, for example.

Second, companies need to be held accountable for how they use data from smart glasses. If Meta deploys facial recognition, there need to be mechanisms for individuals to know when they've been identified, to object, and to get data deleted. Those mechanisms don't currently exist.

Third, privacy-first alternatives need to be supported. This might mean funding open-source smart glasses projects, supporting non-commercial developers, or creating tax incentives for hardware companies that prioritize privacy.

Fourth, users need to be educated about the actual capabilities and risks of smart glasses. Marketing materials are insufficient. People need to understand that wearing a head-mounted camera changes your ethical relationship to the people around you.

Fifth, social norms need to evolve. We should push back on the normalization of continuous recording. Just because technology is possible doesn't mean it's acceptable. Society needs to articulate and enforce boundaries around surveillance.

None of this is happening right now. Meta is deploying surveillance infrastructure without meaningful constraints. Regulators are behind the technology. Companies are competing on who can extract more data. And users are gradually adapting to a reality where they're constantly recorded and identified.

The window for preventing that future is closing. It's not closed yet. But it's narrowing. If facial recognition gets deployed in smart glasses without regulatory frameworks in place, if it proves commercially successful, if competitors adopt similar capabilities, then we'll have built surveillance infrastructure that's difficult to constrain and impossible to reverse.

That's what Meta's strategy to deploy during political distraction really means. It means accepting that the decision about mass surveillance infrastructure will be made by market forces and corporate incentives rather than public deliberation and democratic process.

And that's why smart glasses represent one of the most important privacy battles of the next decade. Not because smart glasses are inherently evil. But because they're the final piece that completes the surveillance infrastructure. Once they're deployed, the panopticon stops being theoretical and becomes actual.

Conclusion: The Choice We're Making Without Realizing It

Meta's Ray-Ban smart glasses are actually remarkable pieces of technology. I mean that sincerely. The engineering is solid. The user experience is thoughtful. The accessibility applications are genuinely beneficial for some people. If the company that made them had different incentives—if they made money from hardware sales rather than behavioral data extraction—smart glasses could be genuinely wonderful technology.

But Meta makes money from surveillance. That's the brutal reality. Everything the company does, from features to deployment strategies, optimizes for data extraction. When Meta explores facial recognition, it's not exploring that feature to help people. It's exploring it because the feature creates opportunities for unprecedented behavioral data collection.

And the strategy to deploy during political distraction? That reveals what Meta actually thinks about privacy concerns. Not that they're legitimate problems that need solving. But that they're obstacles that need circumventing.

The smart glasses problem is ultimately a choice we're making as a society. We can allow smart glasses to be deployed without constraint, knowing that they'll likely become surveillance infrastructure. Or we can demand regulatory frameworks, privacy-first design, and transparent deployment. We can support alternatives to Meta. We can push back on social normalization of continuous recording.

Right now, we're drifting toward the first option. Meta is building the hardware. The regulatory frameworks are years behind. Competitors are watching and preparing to follow. Users are gradually adjusting to a more surveilled world. The momentum is in the direction of ubiquitous smart glasses with facial recognition.

Changing that trajectory requires deliberate action. It requires people understanding what's at stake. It requires recognizing that surveillance infrastructure, once deployed, is nearly impossible to remove. And it requires understanding that Meta's timing—rolling out powerful surveillance features when privacy advocates are distracted—reveals the company's actual priorities.

The smart glasses future is being built right now. And without intervention, it'll be a future where your movements are tracked, your face is identified, and your private moments become data points in corporate systems. That's not inevitable. But it's where we're headed if nothing changes.

FAQ

What exactly are Meta's Ray-Ban smart glasses?

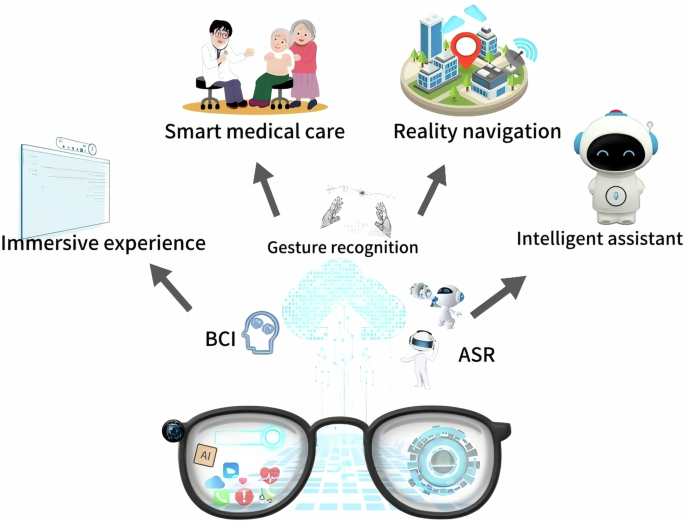

Meta's Ray-Ban smart glasses are wearable devices that combine camera technology, display functionality, and artificial intelligence to provide real-world information overlays and assistance. They include dual cameras for recording video and photos, a small display lens visible to the wearer, microphones for audio input, and processing power to run AI models. The glasses connect to smartphones and Meta's servers to enable features like real-time translation, object recognition, and the ability to identify locations and landmarks.

How does facial recognition on smart glasses differ from traditional surveillance systems?

Facial recognition on smart glasses is different because the recording device is discrete, portable, and worn on someone's body rather than stationary. Unlike security cameras that announce their presence, smart glasses look like normal eyewear, so people around the wearer often don't realize they're being recorded or identified. This means facial recognition data can be collected continuously across public spaces without awareness or consent from the people being identified. Traditional surveillance systems are typically stationary, known to be present, and subject to some legal oversight, whereas smart glasses create a distributed, personal surveillance infrastructure.

What are the accessibility benefits of smart glasses with AI assistance?

For people with visual disabilities, smart glasses can provide significant benefits. The technology can verbally describe surroundings, read text aloud, identify objects and people, provide navigation assistance, and help with wayfinding in unfamiliar spaces. For people with cognitive disabilities or social anxiety, the glasses could help with memory assistance, provide context in social situations, or offer real-time information about their environment. These applications are genuinely beneficial and represent legitimate use cases for the technology.

Why is Meta's timing for facial recognition deployment concerning?

According to reporting, Meta considered deploying facial recognition "during a dynamic political environment" specifically because privacy advocates would be distracted. This reveals that Meta wasn't trying to address privacy concerns transparently but rather to circumvent public opposition through strategic timing. The concern is that deploying powerful surveillance infrastructure during periods when public attention is focused elsewhere prevents meaningful democratic deliberation about the technology and locks in surveillance capabilities that become difficult to constrain retroactively.

How vulnerable is the privacy light on Meta's smart glasses?

The privacy light on Meta's smart glasses has documented vulnerabilities. A $60 modification can disable the light without affecting the recording capability. Additionally, users have reported that the light can simply stop working on its own. While the light provides some deterrent effect, it's not a reliable technical safeguard. The light should be understood as a social signal rather than a technical control.

What regulatory frameworks currently exist for smart glasses facial recognition?

Regulatory frameworks for smart glasses facial recognition are underdeveloped in most jurisdictions. The European Union's AI Act includes provisions for regulating biometric systems, but focuses primarily on government use rather than consumer devices. Some US states have restricted law enforcement use of facial recognition, but most don't restrict consumer deployment. Most countries lack specific regulations addressing facial recognition in consumer wearable devices, creating a significant gap in oversight.

Could smart glasses be designed with stronger privacy protections?

Yes. A privacy-first design approach would process all data on-device rather than sending it to company servers, require explicit user consent for each use of sensitive features, delete data immediately after use unless explicitly saved, disable background processing, and provide transparency about what data is collected. Modern mobile processors are powerful enough to support these approaches. However, companies like Meta don't build privacy-first designs because their business models depend on extracting behavioral data. Privacy protection would require different business models.

What should users understand before purchasing smart glasses?

Before purchasing smart glasses, users should understand that they're buying recording devices that create permanent video and audio records. They should assume that the privacy protections (like the privacy light) have vulnerabilities and aren't fool-proof. They should understand that the data collected is used to train AI systems and improve targeting algorithms. They should be aware of local laws regarding personal recording devices and consent. They should anticipate potential social consequences from people who notice them wearing recording devices. And they should assume that future features, including facial recognition, will eventually be available on the platform.

Key Takeaways

- Meta's facial recognition feature for smart glasses would enable real-time identification of strangers, raising unprecedented privacy concerns about distributed surveillance infrastructure

- The company's strategy to deploy facial recognition during political distraction reveals that Meta understands privacy concerns are legitimate obstacles rather than addressable problems

- Smart glasses are dangerous not because of the technology itself but because their discrete design makes surveillance invisible—people don't know they're being recorded

- Regulatory frameworks addressing consumer smart glasses and facial recognition are significantly underdeveloped, creating a window where companies can deploy powerful surveillance tools without legal constraint

- Privacy-first smart glasses designs are technically possible but economically impossible for companies like Meta whose business models depend on behavioral data extraction

Related Articles

- Meta's Facial Recognition Smart Glasses: The Privacy Reckoning [2025]

- FCC Equal Time Rule Debate: The Colbert Censorship Story [2025]

- ICE Domestic Terrorists Database: The First Amendment Crisis [2025]

- Ring's 'Zero Out Crime' Plan: AI Surveillance Ethics Explained [2025]

- DHS Subpoenas for Anti-ICE Accounts: Impact on Digital Privacy [2025]

- AI Ethics, Tech Workers, and Government Surveillance [2025]

![Meta's Smart Glasses Problem: Why Facial Recognition Could Ruin Everything [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/meta-s-smart-glasses-problem-why-facial-recognition-could-ru/image-1-1771594528972.jpg)