Microsoft's Maia 200 Chip: Reshaping the Future of AI Inference

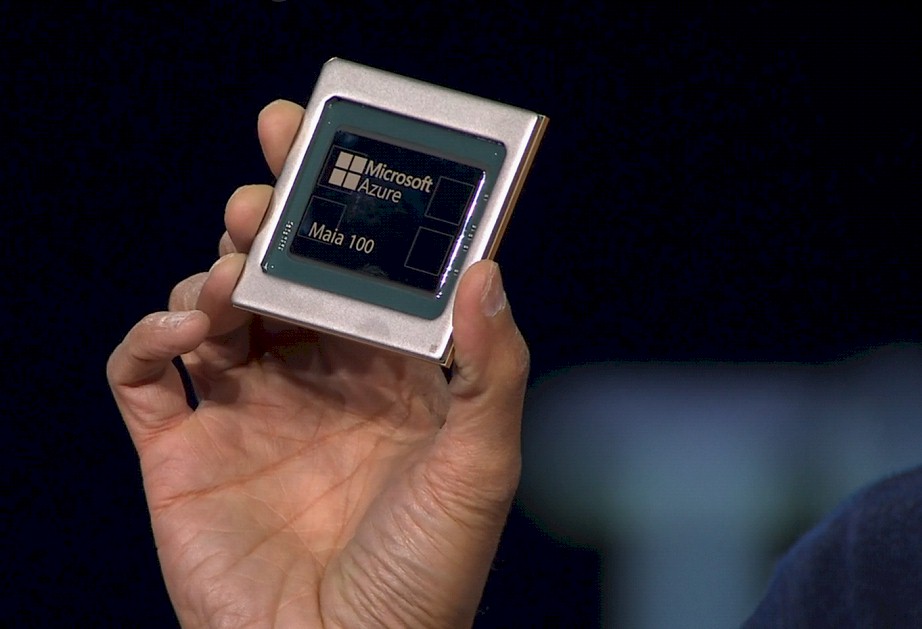

There's a seismic shift happening in the semiconductor world, and it's fundamentally changing how companies think about building AI infrastructure. For years, NVIDIA controlled the narrative. Their GPUs were the only game in town, and everyone knew it. But something shifted in early 2025 when Microsoft stepped forward with the Maia 200—and suddenly, the conversation got a lot more interesting.

Let me be direct: this isn't just another chip announcement. This is Microsoft throwing down a serious gauntlet at NVIDIA's feet while simultaneously solving one of the biggest pain points plaguing enterprise AI adoption. The Maia 200 isn't designed for training massive models. It's built for inference, which is where real money gets spent in production environments.

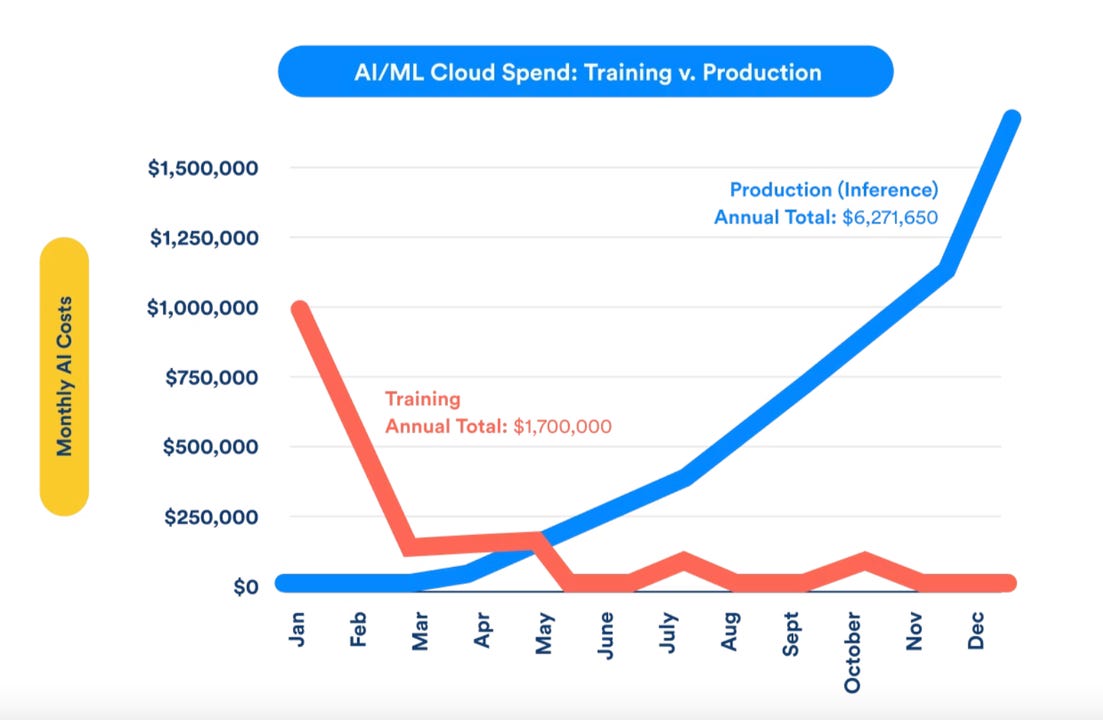

Here's the thing that matters most: inference costs represent the actual economics of running AI at scale. When you've trained a model, that's a one-time expense. But running it in production? That's ongoing, real dollars bleeding out every day. Companies are spending billions on inference infrastructure, and most of them are paying NVIDIA's premium prices because alternatives didn't exist. Until now.

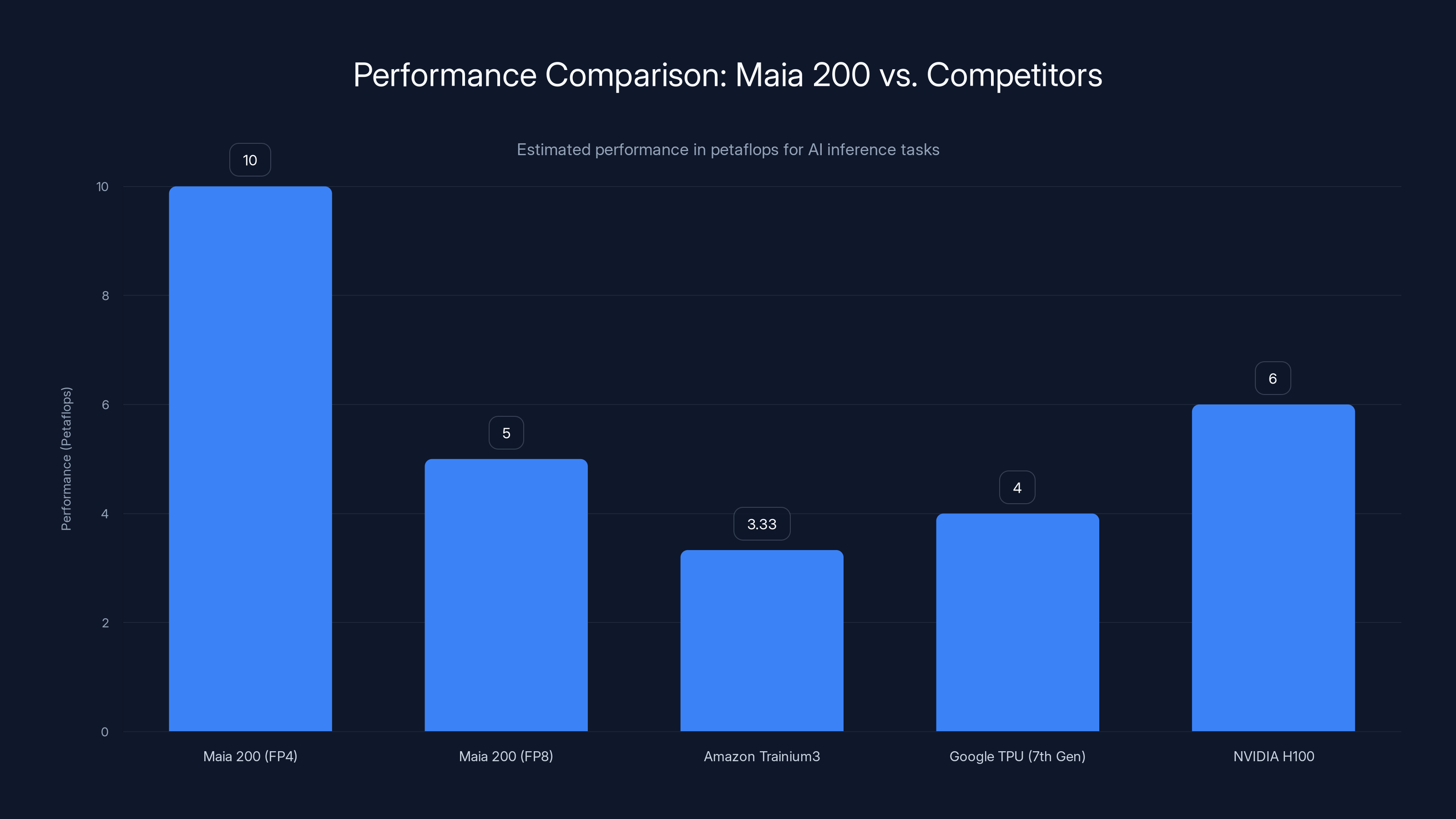

Microsoft's Maia 200 packs over 100 billion transistors and delivers more than 10 petaflops of performance in 4-bit precision, with roughly 5 petaflops in 8-bit mode. These aren't theoretical numbers either. The chip is already powering Microsoft's own AI infrastructure, running Copilot, supporting Superintelligence research, and handling production workloads.

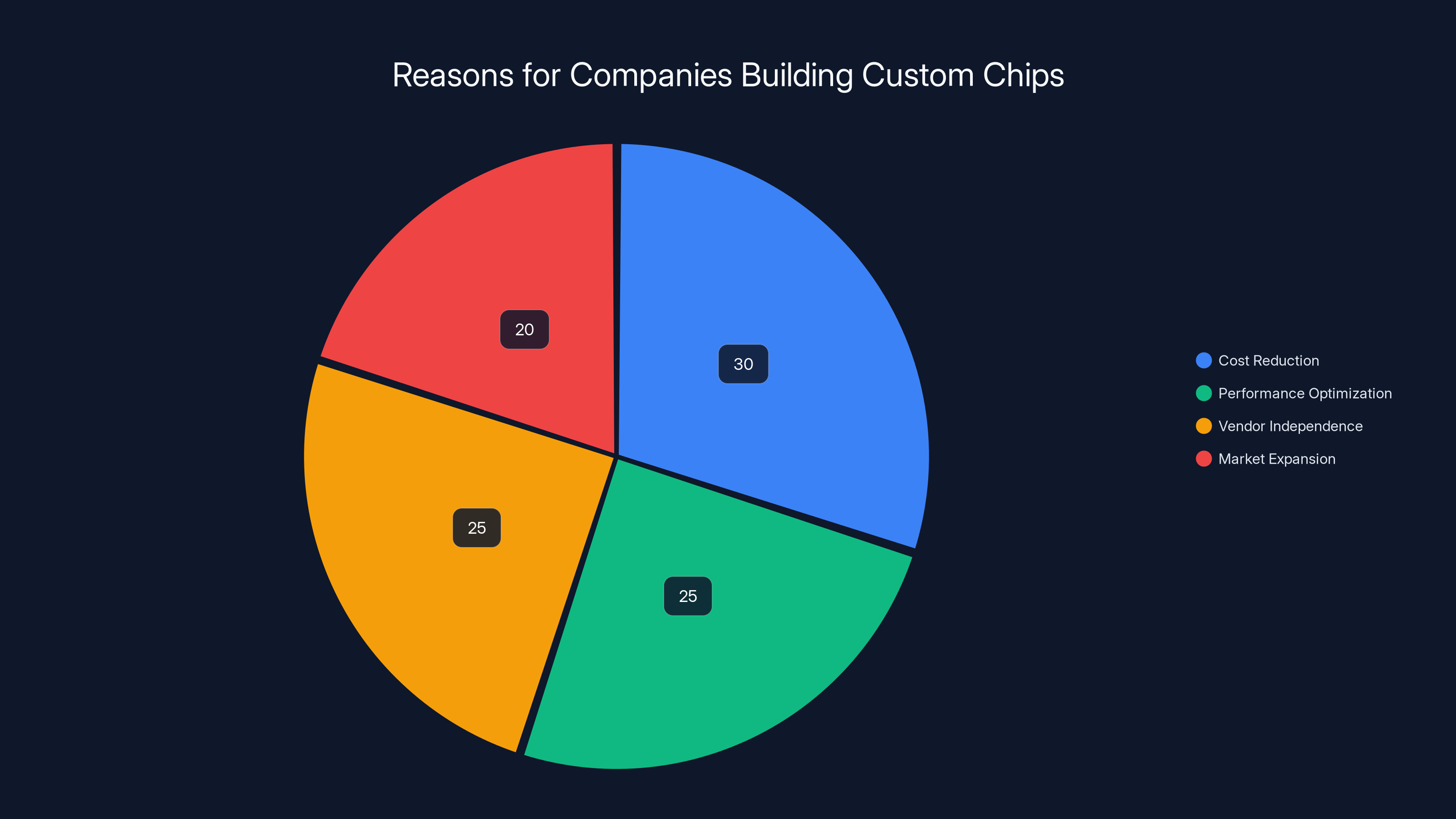

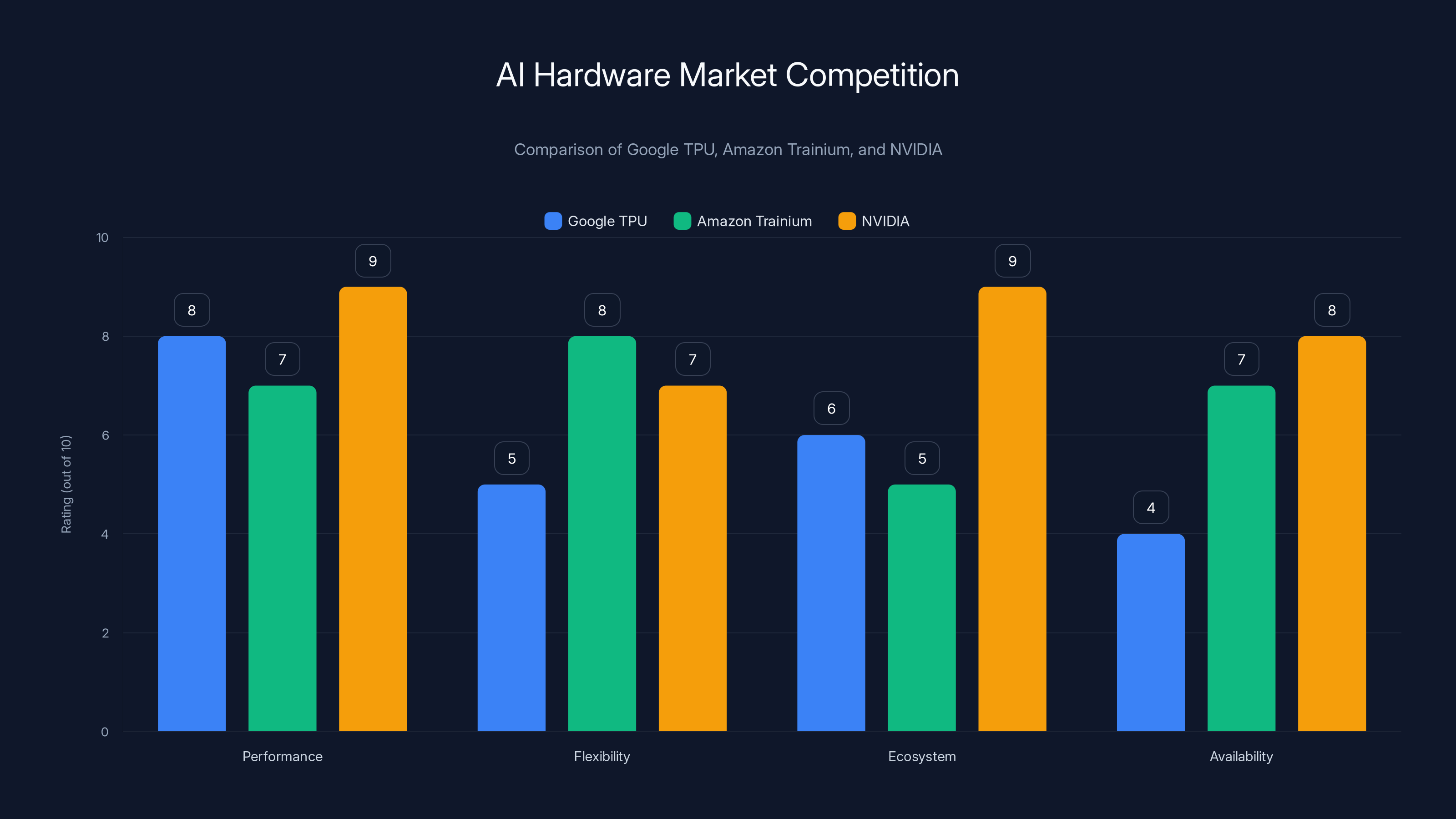

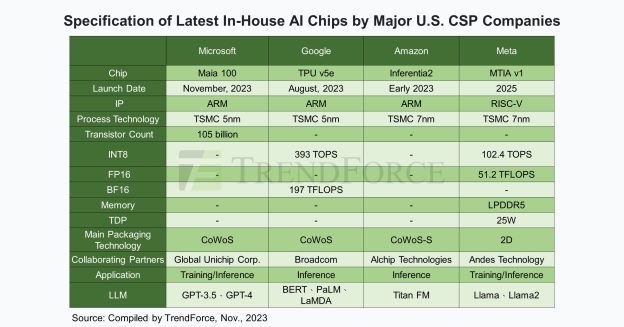

The broader context here is crucial. Tech giants realized years ago that relying entirely on NVIDIA created a bottleneck. Google built TPUs. Amazon developed Trainium. Meta explored custom silicon. And Microsoft? They're taking their shot with Maia, and early indications suggest they're hitting their target.

But this story goes deeper than just hardware specs. It's about chip economics, enterprise AI adoption, the future of model deployment, competitive pressure reshaping trillion-dollar markets, and what happens when companies decide they can't wait for vendors anymore.

Let's dig into what's actually happening here, why it matters, and what the ripple effects might be across the entire AI industry.

The Economics of AI Inference vs. Training

Most people conflate model training with deployment, but they're fundamentally different problems with completely different hardware needs. Understanding this distinction is essential to understanding why Maia 200 matters.

Training a large language model is brutally expensive. It requires sustained, intensive computation over weeks or months. You're doing matrix multiplications repeatedly, shuffling massive datasets, backpropagating gradients. The process demands the kind of raw horsepower that GPUs excel at. Training GPT-4 probably cost hundreds of millions of dollars. Training Claude 3 wasn't cheap either.

But here's where most people get confused: once the model is trained, you don't need that same hardware to use it. Inference is different. When someone types a question into Chat GPT, that's inference. The model's weights are fixed. You're running forward passes, not training loops. The computational requirements drop dramatically.

Yet companies somehow ended up spending astronomical amounts on inference hardware anyway. Why? Because NVIDIA's GPUs, while overkill for pure inference, were the only option that scaled. So everyone bought them, even if they were paying for capabilities they didn't use.

Let's look at actual numbers. A single A100 GPU costs roughly

Microsoft's Maia 200 changes this equation. The chip is specifically architected for inference workloads. It doesn't waste transistors on capabilities you don't need. It's leaner, more efficient, and purpose-built.

Consider this calculation: if inference costs represent 70-80% of your total AI infrastructure spend, and Maia 200 cuts your inference hardware costs by 40-50%, you're suddenly looking at 30-40% savings on total infrastructure. For a company spending

That's not trivial. That's transformative.

Microsoft's Maia 200 chip delivers superior performance in 4-bit precision, outperforming Amazon's Trainium3 and Google's TPU in specific AI inference tasks. Estimated data.

Maia 200: The Technical Deep Dive

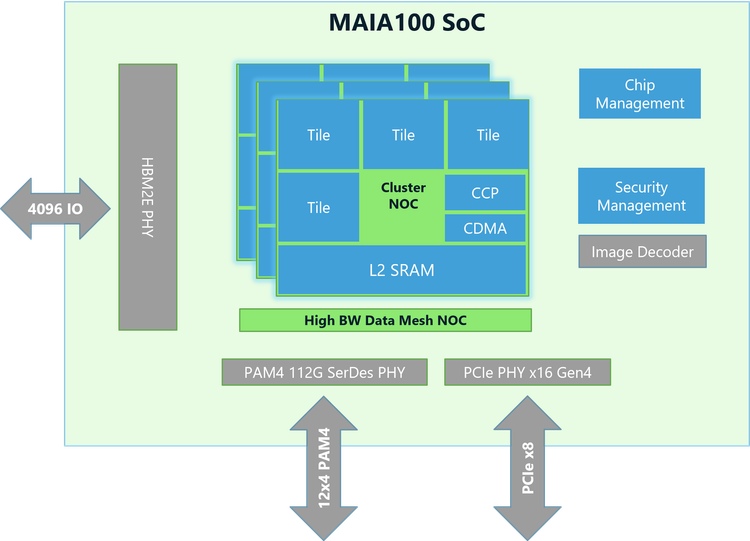

Okay, let's talk specs, because the technical details tell you a lot about Microsoft's thinking here.

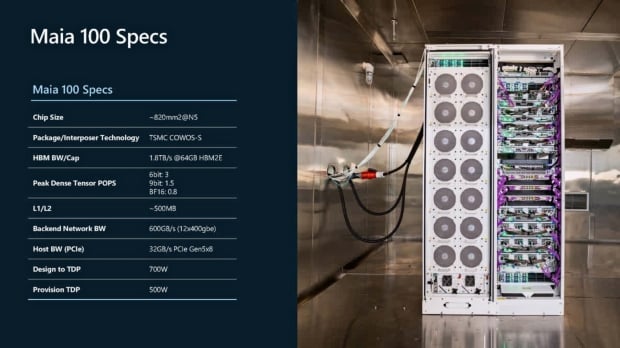

The Maia 200 contains over 100 billion transistors. For context, that's roughly the same transistor count as NVIDIA's H100, which is a training-optimized GPU. Microsoft achieved comparable transistor density while building hardware optimized for a completely different workload. That's impressive engineering.

Performance metrics tell a clearer story than transistor counts ever could. The Maia 200 delivers over 10 petaflops in 4-bit precision. In 8-bit mode, it hits approximately 5 petaflops. Microsoft claims these numbers represent roughly 3 times the FP4 performance of Amazon's Trainium 3 chip and outperform Google's seventh-generation TPU in FP8 performance.

Now, comparing these chips directly is tricky because they're architecturally different. But the headline is straightforward: Maia 200 is genuinely competitive with custom silicon from companies that have invested enormous resources in chip design.

What's particularly clever about Maia's architecture is how it handles different precision levels. Most inference workloads don't need full 32-bit floating point. They work fine at 8-bit, or even 4-bit. You get minimal accuracy loss and massive memory savings. The Maia 200 is optimized exactly for this reality.

Memory bandwidth is another critical metric for inference workloads. You're not doing much computation relative to the amount of data moving through the system. The bottleneck is typically pulling weights from memory, not compute itself. Maia 200 addresses this with high-bandwidth memory access patterns optimized for how models actually get deployed.

Microsoft also emphasized that "one Maia 200 node can effortlessly run today's largest models, with plenty of headroom for even bigger models in the future." This matters because it means you don't need to parallelize across multiple chips for most workloads. The economics get better, the complexity drops, and operational overhead shrinks.

The chip also includes built-in support for common AI frameworks and deployment patterns. Microsoft isn't asking developers to rewrite code. They're providing SDKs, tools, and documentation that let existing applications run with minimal changes.

Estimated data shows that cost reduction and performance optimization are primary drivers for companies building custom chips, each accounting for about a quarter of the motivation.

Why Companies Are Building Their Own Chips

Microsoft didn't wake up one day and decide to become a semiconductor company. They were forced into it by circumstance and incentive.

NVIDIA's dominance in AI is genuine and well-earned. Their engineering is excellent, their software ecosystem is mature, and they've spent years optimizing for machine learning workloads. But dominance creates pricing power, and pricing power creates incentives for alternatives.

When NVIDIA's GPUs are the only viable option for a critical business function, NVIDIA can charge accordingly. There's no competition. No way to negotiate. No ability to shop around. You buy what they sell, at the price they set, or you don't do AI at scale.

For a company like Microsoft that's investing tens of billions in AI infrastructure, that's unacceptable. They're essentially paying a tax to NVIDIA on every AI service they provide. Microsoft Azure can't pass through NVIDIA's premium pricing to customers indefinitely. The margins get squeezed. Growth becomes constrained.

Google faced the exact same problem, which is why they built TPUs. Amazon had the same realization, leading to Trainium and Inferentia chips. Meta faced the same pressures. These companies didn't build custom silicon because they wanted to. They built it because the alternative—depending entirely on a single vendor—was worse.

Microsoft's approach is interesting because they're not just building chips for internal use. They're opening Maia 200 to external developers, academics, and AI labs. This suggests they might actually try to sell or license the technology, not just use it internally.

This shift has massive implications for the semiconductor industry. For decades, chip design was concentrated among specialist companies: NVIDIA, Intel, AMD, ARM. But the economics of AI changed that. Companies with sufficient capital can now afford to design their own silicon, and the potential payoff justifies the investment.

We're not at a point where Microsoft is competing directly with NVIDIA in the discrete GPU market. But we're at a point where Microsoft has reduced their NVIDIA dependency significantly, which changes leverage in negotiations and gives them optionality.

Maia 200 vs. The Competition: How It Stacks Up

Let's do a head-to-head comparison of where Maia 200 sits relative to other custom silicon and NVIDIA alternatives.

| Hardware | FP4 Performance | FP8 Performance | Primary Use Case | Ownership |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maia 200 | 10+ petaflops | 5 petaflops | AI inference | Microsoft |

| Trainium 3 | 3.3 petaflops | Strong performance | AI inference | Amazon |

| TPU v 7 | ~9 petaflops | Strong performance | Mixed workloads | |

| H100 GPU | 1.4 petaflops | 2.8 petaflops | Training + inference | NVIDIA |

| A100 GPU | 0.6 petaflops | 1.2 petaflops | General-purpose ML | NVIDIA |

This table is incomplete and somewhat misleading because these chips solve different problems. But the headline is that Maia 200 is genuinely competitive on raw performance metrics.

Where Maia 200 potentially excels is in power efficiency and cost per inference operation. NVIDIA GPUs are designed for maximum compute density. They're built to handle training workloads, which require different characteristics than inference. Maia 200 is stripped down, optimized, and purposeful.

Microsoft's claim of 3x FP4 performance compared to Trainium 3 is significant. If that holds up in real-world deployments, it means Maia 200 can handle roughly three times the inference load per chip. That directly translates to cost savings.

But here's the catch: raw performance metrics don't tell you the whole story. What matters is:

- Actual latency in production: How fast can the chip process individual requests? Users care about response time, not throughput.

- Memory efficiency: Can it run current models without exotic techniques?

- Cost per inference: Including infrastructure, power, cooling, and support.

- Software maturity: Are there good frameworks, libraries, and tools?

- Operational complexity: How hard is it to deploy and maintain?

Maia 200 likely wins on several of these dimensions. But NVIDIA has years of software maturity and ecosystem development. That's not easy to overcome.

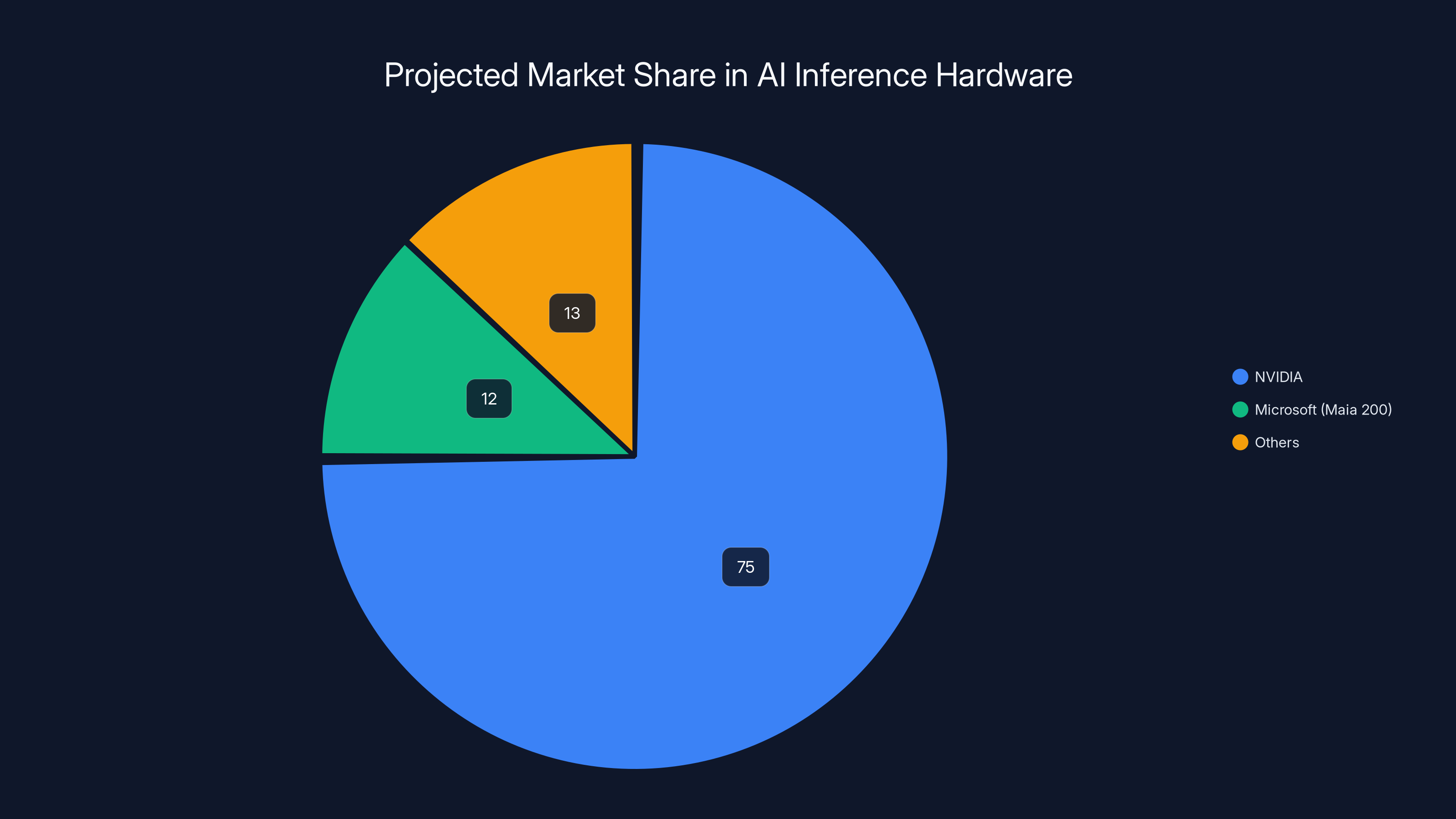

Estimated data suggests Microsoft could capture 10-15% of the AI inference hardware market, reducing NVIDIA's dominance. Estimated data.

The Real Threat to NVIDIA's Dominance

Here's something important to understand: Maia 200 probably isn't going to displace NVIDIA from the training market. Training is where NVIDIA's software moat is strongest. CUDA, cu DNN, Tensor RT, and the entire ecosystem are optimized for training workloads. Building comparable alternatives takes years.

But inference is different. Inference is more standardized, more predictable, and more commoditized. It's a better target for disruption.

If Microsoft can prove that Maia 200 handles 80-90% of real-world inference workloads while cutting costs by 40-50%, they've won. They don't need to displace NVIDIA everywhere. They just need to own the inference piece.

Consider the market dynamics. Inference represents roughly

NVIDIA's response will likely be aggressive price cuts, aggressive bundling with software, and possibly their own inference-optimized products. They have resources to compete, and they're not going to cede market share without a fight.

But the competitive landscape has fundamentally shifted. NVIDIA no longer has a monopoly. Companies have options. That changes everything about how negotiations work, how pricing evolves, and how the market develops.

The longer-term implication is that custom silicon for AI becomes standard, not exceptional. Five years from now, expect Apple, Tesla, Meta, Byte Dance, and other major tech companies to have their own inference chips. NVIDIA will still be dominant in training, but inference becomes increasingly fragmented.

How Maia 200 Powers Production AI Workloads

Let's get specific about what Maia 200 actually does in the real world, because that's where theory meets practice.

Microsoft is already using Maia 200 in several contexts. First, it's running Azure's AI services. When someone uses an AI feature in Microsoft 365, Copilot, or any other cloud service, some of those workloads are running on Maia 200. That's real production traffic, not benchmarking.

Second, Microsoft's research teams are using it for Superintelligence research. That's computationally intensive work, but it's different from serving millions of concurrent users. Research teams can tolerate latency that production systems can't.

Third, external developers and researchers can now access Maia 200 through Microsoft's SDK and development tools. Early access partners include AI labs, academic institutions, and frontier AI companies. This is Microsoft's way of building an ecosystem around the chip.

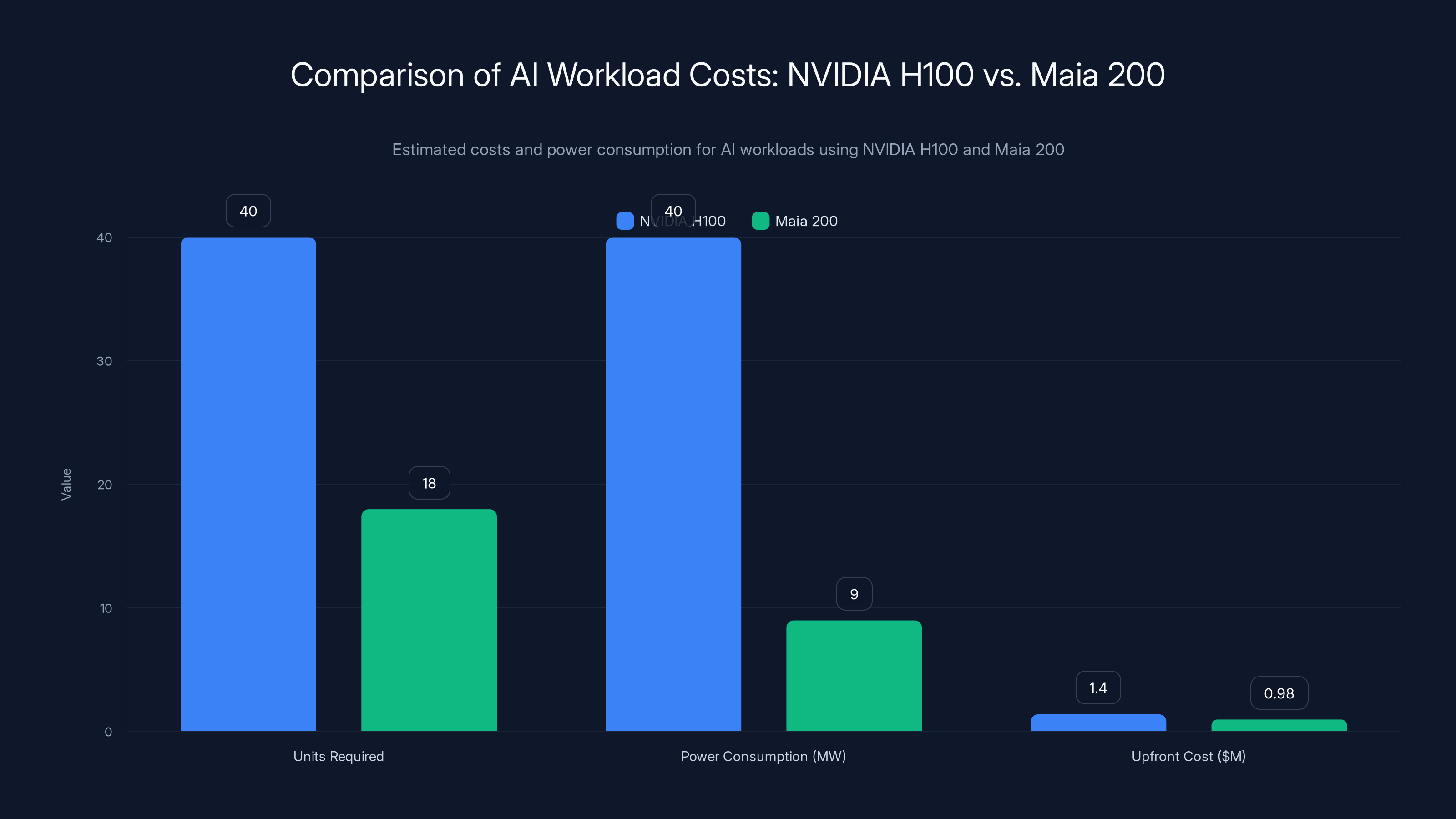

Consider a specific use case: a customer service company that wants to deploy AI-powered chatbots at scale. They need to handle thousands of concurrent conversations with sub-second latency. They also need cost predictability because they're running a business, not a research project.

With NVIDIA GPUs, they might need forty H100 units for their workload, consuming roughly 40 megawatts of power, and costing $1.2-1.6 million upfront, plus ongoing electricity and cooling costs.

With Maia 200, they might need fifteen to twenty units, consuming perhaps 8-10 megawatts, and costing 30-40% less upfront while being significantly cheaper to operate. The economics change dramatically.

Another use case: an e-commerce company embedding product recommendations into their search and browsing experience. That's millions of inferences per second across dozens of models. Efficiency matters enormously at that scale.

Or consider a healthcare company deploying diagnostic AI across hundreds of clinics. Each clinic needs local inference capability, but the aggregate demand is enormous. Cost per inference directly impacts whether the technology gets deployed or stays shelved.

In all these cases, Maia 200 changes the cost-benefit calculation. Workloads that were barely economical become clearly profitable. Workloads that were impossible become feasible.

Maia 200 offers significant cost and power savings compared to NVIDIA H100 for AI workloads, requiring fewer units and consuming less power. (Estimated data)

The Strategic Implications for Microsoft's AI Ambitions

Microsoft isn't building Maia 200 just to compete with NVIDIA. It's part of a larger strategy to own the entire AI stack, from models (through Open AI partnerships) to infrastructure (Azure) to chips (Maia) to software (Copilot).

This vertical integration gives Microsoft enormous advantages. They can optimize across layers. They can guarantee supply. They can control pricing. They can move faster than companies that depend on third-party hardware.

Consider the competitive positioning. When customers want to run AI on Azure, Microsoft can offer them optimized hardware, optimized software, and direct support. They're not just reselling someone else's products. They're offering a complete stack.

Google has been building this stack for years with TPUs and internal AI infrastructure. That's one reason Google remains competitive in AI despite spending less on GPU purchases than Microsoft or Amazon.

Amazon is trying to do something similar with Trainium, Inferentia, and custom silicon. But Amazon's approach is more fragmented. Trainium is for training, Inferentia is for inference, and they have different strengths.

Microsoft's advantage is that Maia is purpose-built for inference at a single point: production deployment. That focus allows extreme optimization.

The strategic bet here is that Microsoft is betting correctly on the future of AI compute architecture. If inference workloads really do become the dominant use case, and if Maia 200 really is superior for those workloads, then Microsoft has positioned themselves perfectly.

But there's risk too. If training workloads become more important than expected, or if customers really do need NVIDIA's specific capabilities, then Maia becomes a sidecar at best. Microsoft would have invested billions in a product with limited applicability.

That's why Microsoft is moving carefully. They're not abandoning NVIDIA. They're adding optionality. They're building a safety valve for cost control without sacrificing performance.

Inference at Scale: Technical Challenges Maia Addresses

Inference sounds simple: load a model, run data through it, return results. But inference at production scale introduces nasty problems that theoretical benchmarks don't capture.

First, there's the latency problem. Users expect responses in milliseconds. Training workloads can tolerate seconds of compute time. Inference can't. This requires different hardware characteristics: lower memory access latency, higher clock speeds, better cache behavior.

Second, there's the concurrency problem. A single inference machine might handle thousands or millions of requests per second. Managing that efficiently requires sophisticated scheduling, memory management, and resource allocation. Batching requests helps, but batching introduces latency tradeoffs.

Third, there's the model diversity problem. You might be running five different models on the same hardware: a classification model, a ranking model, a recommendation model, a translation model, a summarization model. Each has different performance characteristics. Each requires different resource allocation. Managing this is complex.

Fourth, there's the precision problem. Modern models are trained in float 32, but inference can use lower precision. Not all operations can use lower precision though. Some parts of the model need higher precision or you get accuracy degradation. Mixing precisions requires careful orchestration.

Maia 200 addresses these challenges through:

Low-latency memory architecture: The chip has high-bandwidth memory closely coupled to compute. Model weights load quickly, latency stays predictable.

Dynamic batching support: The hardware and software stack support efficient batching across thousands of requests without inducing unacceptable latency.

Mixed precision execution: Native support for 4-bit, 8-bit, and 16-bit operations, allowing different parts of the model to use appropriate precision.

Advanced scheduling: Software stack optimizes scheduling of different models and requests across available hardware resources.

Thermal efficiency: The chip is power-efficient, reducing data center cooling costs and electrical overhead.

These aren't theoretical advantages. These are the actual problems that production inference systems need to solve.

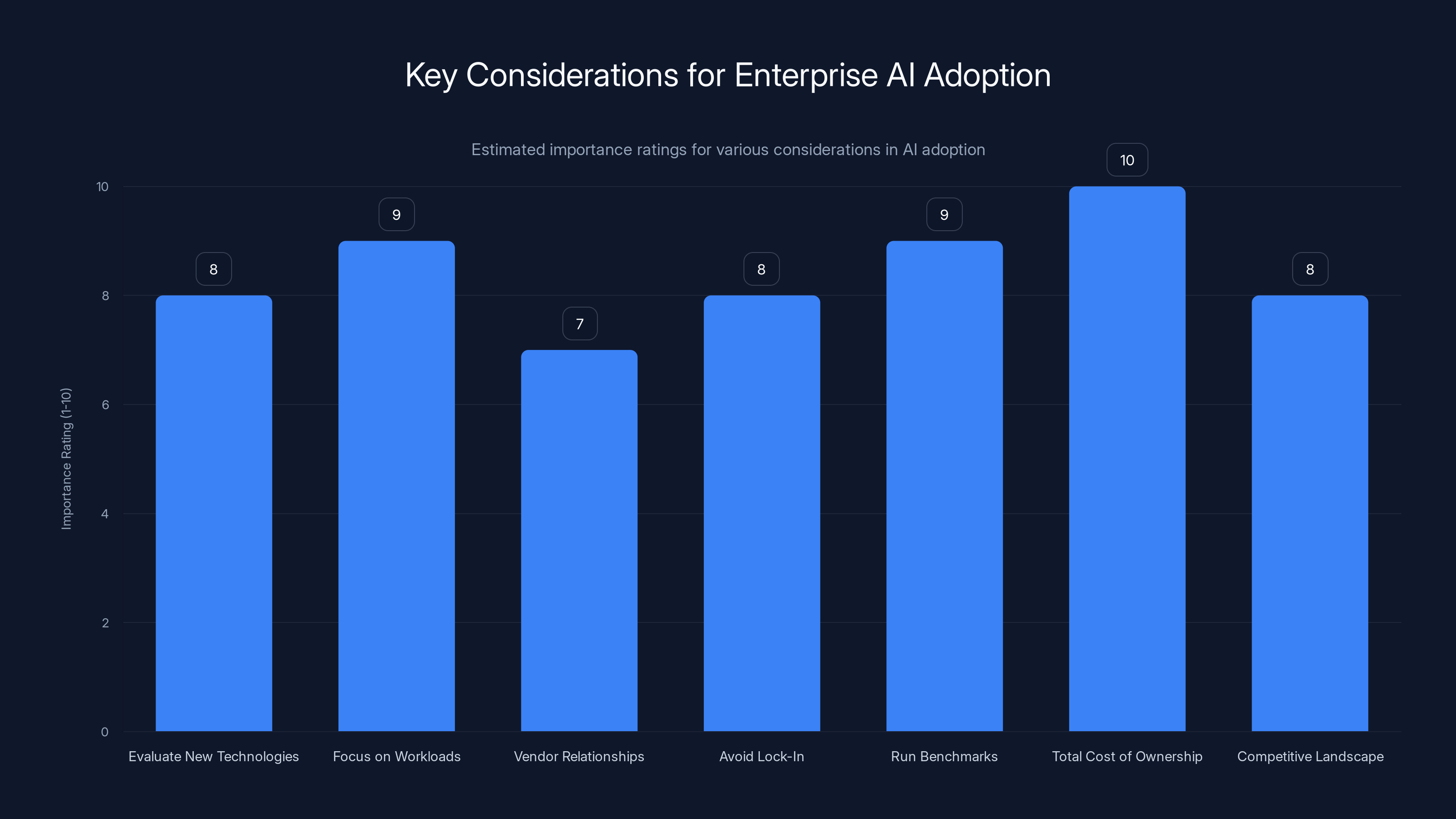

Importance ratings for various considerations in enterprise AI adoption show that focusing on workloads and total cost of ownership are critical. (Estimated data)

Market Competition: Google TPU, Amazon Trainium, and NVIDIA's Response

Maia 200 enters a field where competition is getting more serious.

Google's TPU has been around for years. It's mature, well-understood, and integrated into Google's cloud infrastructure. The latest generation (TPU v 7) is competitive on performance metrics. But TPUs are only available through Google Cloud, which limits their addressability. You can't buy TPUs and deploy them yourself. You have to use Google's cloud infrastructure.

Amazon's Trainium is newer, more flexible, and available through AWS. But Trainium is fragmented between Trainium (for training) and Inferentia (for inference), which adds complexity. Amazon's also still optimizing their software stack and tool integration.

Microsoft's advantage is that Maia 200 is specifically for inference, so there's no fragmentation. It's also being positioned more openly. Microsoft is providing SDKs and inviting external developers to use the technology, not just internal teams.

NVIDIA's response will be multi-pronged. First, they're likely to cut GPU prices, especially for inference-focused products. They might accelerate release cycles for inference-optimized hardware. They might bundle software discounts. They might improve their software stack and developer tools.

Second, NVIDIA will point to their massive installed base and ecosystem. Most data centers run NVIDIA. Most developers know CUDA. Most frameworks are optimized for NVIDIA hardware. That's powerful moat, and it's not easy to overcome.

Third, NVIDIA will emphasize their advantages in training workloads and mixed training-inference scenarios. For companies that need to do both training and inference, NVIDIA offers a unified platform.

But make no mistake: NVIDIA's pricing power has diminished. They no longer have a monopoly on inference. Customers will increasingly negotiate, look at alternatives, and potentially split workloads across multiple hardware platforms.

Long-term, I'd expect the market to stratify:

- Training: NVIDIA dominates, but faces increasing competition from custom silicon

- Inference at hyperscalers: Increasingly custom silicon (Maia, TPU, Trainium) supplemented by NVIDIA

- Inference at smaller scale: Mix of NVIDIA, custom silicon, and possibly new entrants

- Edge inference: Specialized hardware, not traditional GPUs

Power Efficiency and Data Center Economics

Power consumption isn't just an environmental concern. It's a major cost factor for data centers.

Large data centers running AI workloads consume enormous amounts of electricity. A facility running thousands of GPUs might use 50-100 megawatts, costing tens of millions of dollars annually in electricity alone. That doesn't include cooling infrastructure, real estate, networking, and redundancy systems.

Maia 200 is designed with power efficiency in mind. By being purpose-built for inference rather than general-purpose compute, it can eliminate unnecessary circuitry and optimize for actual workloads.

Let's do a rough calculation. Assume a data center running inference workloads:

- H100 GPU: ~700 watts per GPU

- 100 H100 GPUs: ~70 kilowatts

- Effective infrastructure overhead (cooling, power conversion, etc.): ~1.5x

- Total: ~105 kilowatts

- Annual electricity cost (at 920,000

Now with Maia 200:

- Maia 200: ~300-400 watts per chip

- 50 Maia chips for same performance: ~17.5-20 kilowatts

- Infrastructure overhead: ~1.5x

- Total: ~26-30 kilowatts

- Annual electricity cost: ~$230,000

That's a roughly $690,000 annual saving in electricity alone. For a company running multiple data centers, the aggregate savings becomes billions of dollars.

Moreover, lower power consumption means lower cooling requirements, which means cheaper data center infrastructure. You need less redundancy. You have more flexibility in placement. You reduce environmental impact.

For a company like Microsoft that's building massive data center capacity to support AI services, power efficiency isn't nice-to-have. It's essential. It directly impacts the feasibility of their business model.

This is why companies are willing to invest billions in custom silicon. The payoff, measured in power savings alone, justifies the investment within a few years of deployment at scale.

NVIDIA leads in ecosystem and performance, but Amazon Trainium offers more flexibility and availability. Estimated data based on market analysis.

Software Ecosystem and Developer Tools

Hardware without good software is expensive silicon. A Maia 200 is only useful if developers can actually write code for it.

Microsoft is providing:

- SDK and development tools: Software development kits that let developers write code targeting Maia 200

- Framework support: Integration with Py Torch, Tensor Flow, and other major ML frameworks

- Optimization libraries: Tools to convert models to formats that run efficiently on Maia

- Documentation and examples: Reference implementations and tutorials

- Direct support: Access to Microsoft engineers for optimization and troubleshooting

This is all crucial, and it's where Microsoft has advantages over some competitors. NVIDIA has spent twenty years building a software ecosystem. You can't replicate that overnight. But you can shortcut it by building good abstractions and focusing on the actual hard problems developers care about.

Microsoft also has relationships with major AI research labs and companies. They can work with early adopters to optimize workloads, find problems early, and refine the software stack based on real-world feedback.

Google did something similar with TPUs. They started with internal use, then gradually opened the platform while improving tools and documentation.

The key is not trying to replicate NVIDIA's entire ecosystem. It's about providing enough tooling and support that competent developers can build on the platform without excessive friction.

Adoption Challenges and Barriers

Despite Maia 200's advantages, adoption will face real barriers.

First, there's inertia. Thousands of companies have already built their infrastructure around NVIDIA. They've trained their teams on CUDA. They've optimized their pipelines. They've built vendor relationships. Switching costs are real, even if the long-term benefits are significant.

Second, there's the chicken-and-egg problem. Developers are reluctant to write code for platforms with small installed bases. Platforms with small installed bases struggle to attract developers. Breaking this cycle takes time and intentional ecosystem building.

Third, there's uncertainty about whether Maia 200 will actually perform as promised in real-world deployments. Benchmarks look great. But how does it actually perform on your specific workload? How does it handle edge cases? How reliable is it? These questions only get answered through production experience.

Fourth, there's the question of long-term commitment. Is Microsoft genuinely committed to this platform, or is it a defensive maneuver they'll abandon if circumstances change? Companies making major infrastructure investments need confidence that their vendor won't disappear.

Fifth, there's integration complexity. Most production systems don't run single workloads on single hardware platforms. They're mixed. Some workloads run better on NVIDIA. Some run better on Maia. Coordinating across multiple platforms introduces operational complexity.

Microsoft is addressing some of these barriers by:

- Offering the chip through Azure and other cloud providers, not just direct sales

- Providing extensive documentation and support

- Working with major research labs and companies on optimization

- Demonstrating real production deployments at scale

- Committing to roadmaps and future product releases

But barriers remain, and they're not trivial. It'll take years for Maia 200 to accumulate significant market share, if it ever does.

The Competitive Dynamics: Winners and Losers

If Maia 200 succeeds, who wins and who loses?

Winners:

Microsoft: Custom silicon gives them control, cost advantages, and differentiation. If Maia succeeds, Azure becomes more competitive, pricing becomes more flexible, and margins improve.

Hyperscalers in general: Google, Amazon, and other large cloud providers benefit from reduced NVIDIA dependency. They can negotiate better terms. They can switch more readily. They have more optionality.

Software companies: As inference becomes decommoditized across different chips, software value increases. Companies that provide frameworks, optimization tools, and orchestration software win.

Developers and researchers: More competition means better pricing, more flexibility, and better tools. That's good for everyone building AI systems.

Losers:

NVIDIA: Not in the sense of going out of business, but in the sense of reduced pricing power, reduced market share, and reduced margins. NVIDIA still dominates, but the dominance is less complete.

Smaller cloud providers: They probably can't afford to build custom silicon. They're stuck buying from NVIDIA at standard pricing. Their costs rise relative to hyperscalers that have custom hardware. The competitive gap widens.

Companies dependent on NVIDIA: Any company whose business model depended on NVIDIA's pricing power or capacity constraints is affected. This might include smaller chip designers, certain system integrators, or specific service providers.

Long-term, this looks like a healthy market dynamic. Competition increases. Efficiency improves. Prices fall. Customers benefit. It's the standard arc of technology maturity.

Looking Forward: Maia Evolution and Roadmap

Microsoft hasn't announced detailed roadmaps, but based on industry patterns and their public statements, we can make educated guesses about where Maia evolves.

Maia 300 is probably already in development. It'll likely offer:

- Higher performance (15+ petaflops in 4-bit?)

- Better power efficiency

- Improved memory bandwidth

- Better support for newer model architectures

- Expanded precision support

There might also be specialized variants:

- Maia Lite: Smaller form factor for edge inference

- Maia Pro: Higher performance for larger models or higher concurrency

- Maia Cluster: Multiple chips optimized for distributed inference

Microsoft will likely maintain API compatibility across generations, allowing code written for Maia 200 to run on future versions with minimal changes. This is crucial for ecosystem adoption.

We'll probably also see closer integration with Azure services, Copilot, and Microsoft's AI products. The chip becomes part of the broader ecosystem, not just a standalone product.

Eventually, Maia might get deployed beyond cloud environments. Microsoft might license the design to other vendors. They might create edge variants for devices. The chip becomes part of the broader computing infrastructure.

But that's all speculation. What we know is that Microsoft has committed to this space, is investing seriously, and has genuine competitive advantages. That's enough to suggest Maia 200 matters and will continue to evolve.

Industry Implications and Market Structure Changes

Maia 200's announcement signals broader structural changes in the computing industry.

For decades, processor design was concentrated among specialist companies: Intel, AMD, NVIDIA, ARM. They had the expertise, the capital, and the scale to justify chip design costs.

But AI changed that equation. The potential payoffs from custom silicon became so large that even capital-intensive chip design became economically rational for hyperscalers.

We're at the beginning of a shift where:

- Specialization increases: Chips optimize for specific workloads rather than general-purpose compute

- Competition fragments: Instead of a few dominant platforms, we get multiple platforms with different strengths

- Software becomes platform-specific: Code optimization matters more. Generic implementations become less viable

- Supply chain complexity increases: Data centers need to manage multiple chip types, different software stacks, different performance characteristics

- Ecosystem fragmentation grows: Some software runs optimally on NVIDIA. Some on Maia. Some on TPU. This is actually good for customers but bad for developers.

This isn't unique to AI. It's happened before in other computing eras. When mainframes dominated, then minicomputers, then personal computers, then mobile devices. Each transition disrupted incumbents and created new winners.

What's different this time is speed. The shift from monolithic processors to specialized AI silicon is happening in years, not decades. That stresses existing organizations and creates opportunity for new entrants.

Practical Considerations for Enterprise Adoption

If you're running a company that cares about AI infrastructure costs, what should you be thinking about?

First, don't wait for perfection. Maia 200 is here now, it's real, and Microsoft is serious about it. Even if you don't switch immediately, you should evaluate it seriously. The financial potential is significant.

Second, focus on your specific workloads. What are you actually trying to run? Is it inference or training? Single models or multiple models? What latency requirements do you have? What precision levels do you need? Different workloads have different answers, and what's optimal for one might not be optimal for another.

Third, build relationships early with vendors. If you're interested in Maia 200, start engaging with Microsoft now. Give them feedback. Test their tools. Participate in their community. This helps them build better products and gives you leverage when it's time to make purchasing decisions.

Fourth, avoid lock-in. Don't make architectural decisions that make it impossible to switch. Keep your code portable. Use standard frameworks. Build interfaces between your systems and the hardware layer. This gives you optionality, which is valuable when you're dealing with new and evolving hardware.

Fifth, run benchmarks. Generic performance claims are one thing. Real-world performance on your actual workloads is different. Don't trust vendor benchmarks. Run your own tests. Measure carefully. Compare apples to apples.

Sixth, think about total cost of ownership. Hardware costs matter, but so do electricity, cooling, real estate, support, and software. Calculate the full cost picture before making decisions.

Seventh, assume the competitive landscape will continue evolving. New options will emerge. Pricing will shift. Features will improve. Plan for a world where you're re-evaluating these decisions regularly, not making them once and committing for a decade.

The Broader Context: AI Infrastructure at Scale

Maia 200 exists in a specific context: the infrastructure arms race for AI supremacy.

Every major tech company is building massive AI infrastructure. Google has TPUs and data centers optimized for ML. Amazon has custom silicon, massive compute capacity, and deep ML expertise. Meta is building enormous infrastructure for AI research and products. Open AI (backed by Microsoft) needs massive compute capacity. Byte Dance is building AI infrastructure to compete globally.

In this environment, controlling your own silicon is a huge advantage. You're not dependent on anyone else's supply chain. You can optimize specifically for your workloads. You can move faster than competitors bound by vendor timelines. You can potentially cut costs significantly.

Microsoft's Maia 200 is part of this broader infrastructure strategy. It's not a product for external customers. It's an internal tool to improve Microsoft's competitive position in AI. Everything else (SDK, external access, ecosystem building) is secondary.

This is important context because it means Microsoft isn't going to abandon Maia after a few quarters if it doesn't immediately become a standalone revenue driver. This is infrastructure they need for their own AI ambitions. The investment is justified by internal use cases alone.

That's actually good news for external developers and potential customers. It means long-term commitment is likely. Microsoft isn't going to kill the project because it didn't gain market share immediately. They need it.

Conclusion: A Watershed Moment for AI Infrastructure

Maia 200 might not be revolutionary in the way breakthrough technologies are. It's not inventing something entirely new. It's optimizing existing concepts for a specific use case.

But it's significant. It represents a shift in market structure, a reduction in NVIDIA's monopoly power, and validation that custom silicon for AI is economically rational even for non-semiconductor companies.

If Maia 200 succeeds—if it truly delivers the promised performance, efficiency, and cost benefits in real-world deployments—it becomes a template. Other companies will follow. Custom silicon for specific AI workloads becomes standard, not exceptional. The semiconductor landscape fragments into multiple competing platforms.

That's actually healthy. Competition drives innovation. It breaks up pricing power. It forces companies to focus on customer needs rather than extracting monopoly rents. It creates opportunity for new entrants. It makes the technology more accessible.

For NVIDIA, this is a challenge but not a death knell. NVIDIA is still the dominant player in AI compute. They have resources, expertise, and market position. They can adapt, compete, and likely remain dominant for years to come.

But their era of monopoly pricing power is probably over. That changes everything about the economics of AI infrastructure going forward.

The fact that Microsoft is confident enough to announce this, to open it to external developers, and to position it as genuinely competitive with NVIDIA hardware tells you something important: the math works. The cost savings are real. The performance is sufficient. This isn't vaporware or desperation. This is a serious product that solves real problems.

We're at an inflection point in AI infrastructure. The next five years will determine whether Maia becomes table stakes for enterprise AI or remains a niche play. But either way, the market has fundamentally changed. NVIDIA's days of unopposed dominance are behind us.

That's the story that matters. Everything else is details.

FAQ

What is Microsoft's Maia 200 chip?

Maia 200 is a custom-designed semiconductor chip built specifically for running artificial intelligence inference workloads at scale. The chip contains over 100 billion transistors and delivers more than 10 petaflops of performance in 4-bit precision, making it optimized for running large language models and other AI models in production environments.

How does Maia 200 differ from NVIDIA GPUs?

Maia 200 is purpose-built for inference workloads, while NVIDIA GPUs like the H100 are general-purpose chips optimized for both training and inference. Maia 200 focuses on memory efficiency, power consumption, and inference-specific optimizations, making it more cost-effective for companies primarily running AI models in production rather than training new models.

What are the performance specifications of Maia 200?

Maia 200 delivers over 10 petaflops in 4-bit floating-point precision and approximately 5 petaflops in 8-bit precision. Microsoft claims the chip provides roughly 3 times the FP4 performance of Amazon's Trainium 3 and outperforms Google's seventh-generation TPU in FP8 performance metrics, though real-world results depend on specific workloads and deployment configurations.

Why is Microsoft building its own AI chip?

Microsoft developed Maia 200 to reduce dependence on NVIDIA for inference workloads and to optimize infrastructure costs for large-scale AI deployment. By building custom silicon tailored to their specific needs, Microsoft can achieve better performance per dollar, improve power efficiency, and maintain more control over their AI infrastructure strategy.

How much does Maia 200 cost compared to NVIDIA hardware?

While Microsoft hasn't published exact pricing, industry analysis suggests Maia 200 is significantly cheaper than comparable NVIDIA infrastructure when accounting for hardware costs, power consumption, cooling requirements, and operational overhead. A single Maia 200 chip can handle inference workloads that might require multiple high-end NVIDIA GPUs, reducing total cost of ownership substantially.

Can I use Maia 200 outside of Microsoft Azure?

Currently, Maia 200 is being offered through Microsoft's cloud platforms and to select early-access partners including AI research labs, academic institutions, and frontier AI companies. While not yet available as a standalone product for direct purchase, Microsoft is providing SDKs and development tools to facilitate external adoption and ecosystem development.

What models can run on Maia 200?

Maia 200 is designed to run any modern large language model and AI inference workload, including state-of-the-art models like GPT-4, Claude, and others. The chip's architecture supports various precision levels (4-bit, 8-bit, 16-bit) and can handle multiple models simultaneously, making it flexible across different use cases and applications.

How does Maia 200 impact the broader AI chip market?

Maia 200 signals that large technology companies are increasingly investing in custom silicon to reduce their dependence on NVIDIA and optimize AI infrastructure costs. This trend is likely to continue with other companies developing specialized chips, leading to increased competition, reduced NVIDIA market share in certain segments, and ultimately better pricing and options for enterprise customers.

What is the power consumption of Maia 200?

Maia 200 is designed with power efficiency as a core architectural goal, consuming significantly less power than comparable GPU solutions for inference workloads—typically 300-400 watts per chip compared to 700+ watts for high-end NVIDIA GPUs. This power efficiency translates to substantial savings in data center electricity costs, cooling infrastructure, and operational expenses at scale.

Will Maia 200 replace NVIDIA GPUs entirely?

No, Maia 200 is specialized for inference workloads and won't replace NVIDIA in training scenarios where GPUs remain optimal. The market is likely to evolve toward specialized hardware where NVIDIA dominates training, custom silicon like Maia handles inference at hyperscalers, and NVIDIA remains strong in general-purpose AI compute. Most enterprises will likely use multiple chip types in their infrastructure.

Key Takeaways

- Microsoft Maia 200 custom chip delivers 10+ petaflops in 4-bit precision, competitive with NVIDIA and custom silicon from Google and Amazon

- Inference workloads represent 70-80% of AI infrastructure costs, making Maia 200's optimization for this segment strategically important

- Power efficiency and reduced cooling requirements could save large enterprises $100+ million annually compared to NVIDIA GPU infrastructure

- Custom silicon is becoming standard for hyperscalers, fragmenting the AI hardware market and reducing NVIDIA's monopoly pricing power

- Maia 200 enables companies to run large language models efficiently at scale, making AI deployment more economically accessible across enterprises

Related Articles

- Tesla's Dojo 3 Supercomputer: Inside the AI Chip Battle With Nvidia [2025]

- RadixArk Spins Out From SGLang: The $400M Inference Optimization Play [2025]

- Why Agentic AI Projects Stall: Moving Past Proof-of-Concept [2025]

- Modernizing Apps for AI: Why Legacy Infrastructure Is Killing Your ROI [2025]

- Agentic AI Demands a Data Constitution, Not Better Prompts [2025]

- The AI Adoption Gap: Why Some Countries Are Leaving Others Behind [2025]

![Microsoft Maia 200: The AI Inference Chip Reshaping Enterprise AI [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/microsoft-maia-200-the-ai-inference-chip-reshaping-enterpris/image-1-1769445775790.png)