Microsoft Rho-Alpha: Physical AI Robots Beyond Factory Floors [2025]

Robots have been stuck. For decades, they've done what they're told in perfectly controlled factory environments where nothing changes. But step outside the assembly line? They fall apart.

That's the problem Microsoft is trying to solve with Rho-Alpha, its first robotics model that brings the power of AI to physical systems. And honestly, this is a bigger deal than it sounds.

Here's what's happening: robots used to need precise instructions for every task. Move left. Grab. Rotate. If a box is slightly rotated or a surface is rougher than expected, they'd fail. But Rho-Alpha changes that game entirely. It combines language understanding, visual perception, and tactile sensing into a single model that lets robots reason about tasks the way humans do.

The core insight is deceptively simple: language models like GPT have revolutionized how software understands instructions. So why shouldn't robots benefit from the same technology? Microsoft's answer: they should. And they're building the infrastructure to prove it.

This shift toward what researchers call "physical AI" represents a fundamental change in robotics. Instead of programming every movement, you can now describe what you want, and the AI figures out how to make it happen. That opens doors to automation in messy, unpredictable environments where no two tasks are ever quite the same.

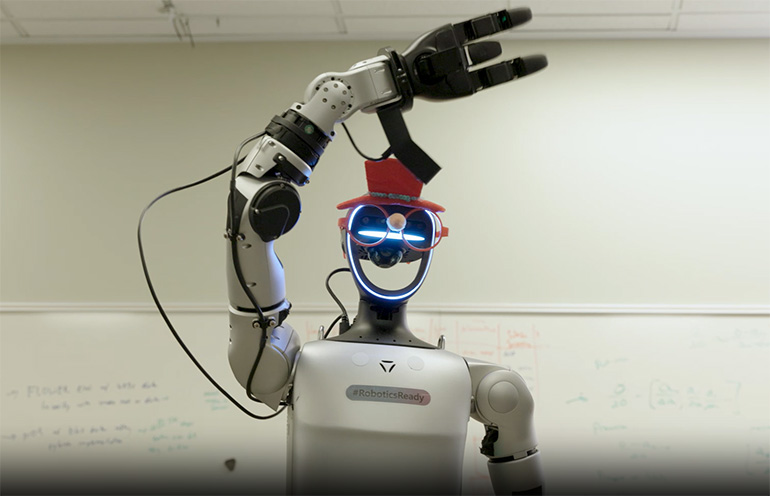

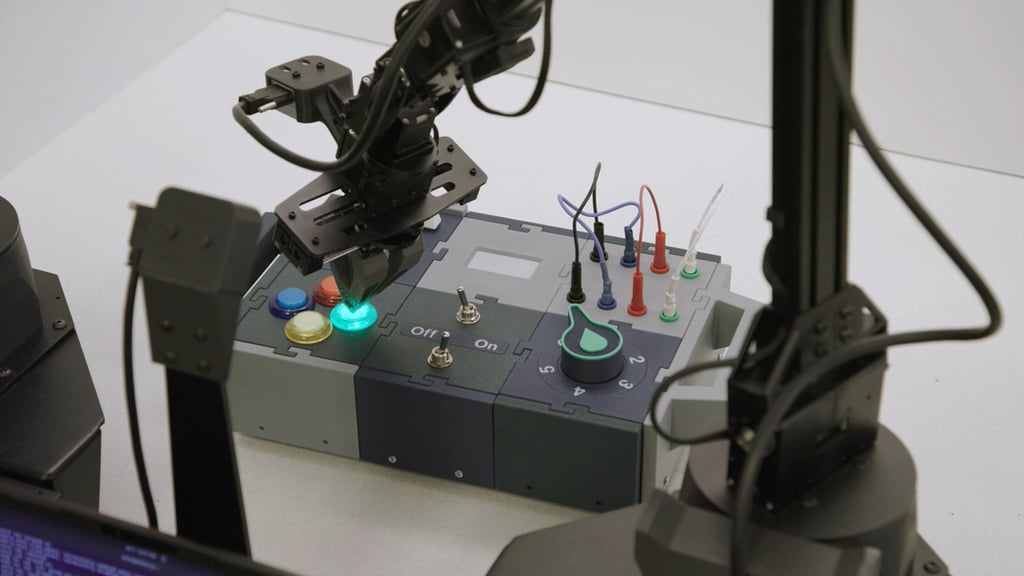

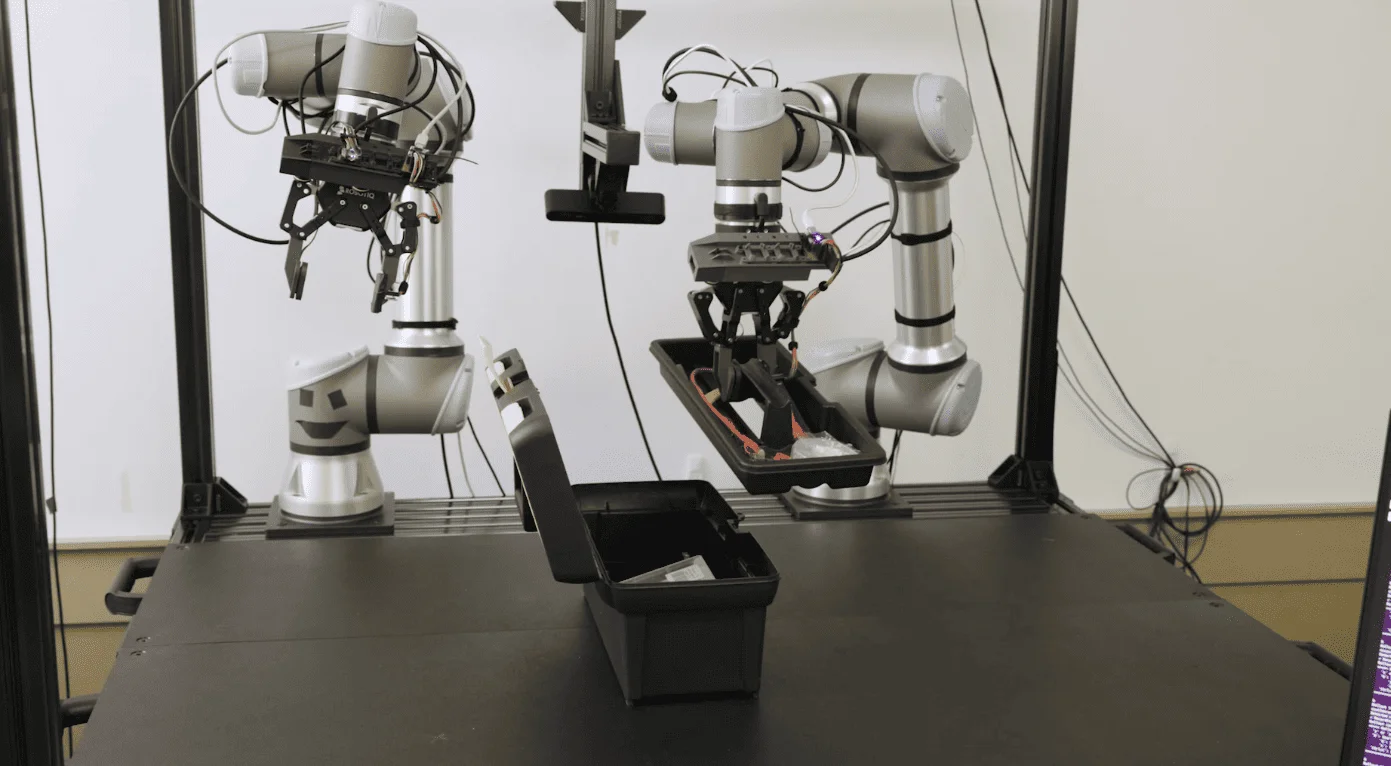

We're not talking about humanoid robots running factories yet. This is more precise than that. Rho-Alpha focuses on bimanual manipulation—tasks requiring two robotic arms working in coordination. Think assembly work, delicate part handling, or any task where precision and adaptability matter.

The real innovation? Microsoft layered in tactile sensing alongside vision. Robots can feel surfaces, pressure, resistance. That matters because it's the difference between understanding something intellectually and understanding it physically. A human hand knows instantly if something is fragile. A robot without touch sensing has to guess.

Here's the thing: building this kind of model at scale is absurdly hard. Real robotics data is scarce. Training a robot in the real world is expensive, time-consuming, and risky. So Microsoft did something clever. They generated synthetic training data using simulation, combined it with real-world demonstrations, and added a human feedback loop. Operators can correct the robot in real-time, and it learns from those corrections.

This matters because it's the template for how physical AI will actually scale. You can't collect a billion hours of robot footage like you can collect internet text. So you build hybrid systems that blend simulation, real data, and human guidance.

Let's dig into what makes Rho-Alpha different, how it actually works, and what it means for the future of automation.

TL; DR

- Physical AI is emerging: Microsoft's Rho-Alpha combines language, vision, and touch to create robots that adapt to unstructured environments instead of following rigid scripts

- Simulation + reality = better robots: The model blends synthetic training data with real-world demonstrations and human feedback to overcome the scarcity of robotics data

- Tactile sensing matters: Adding touch alongside vision narrows the gap between digital intelligence and physical action

- Bimanual tasks first: Rho-Alpha focuses on two-armed coordination, which is essential for complex manipulation work

- Human-in-the-loop learning: Operators provide real-time feedback during deployment, allowing the system to improve continuously

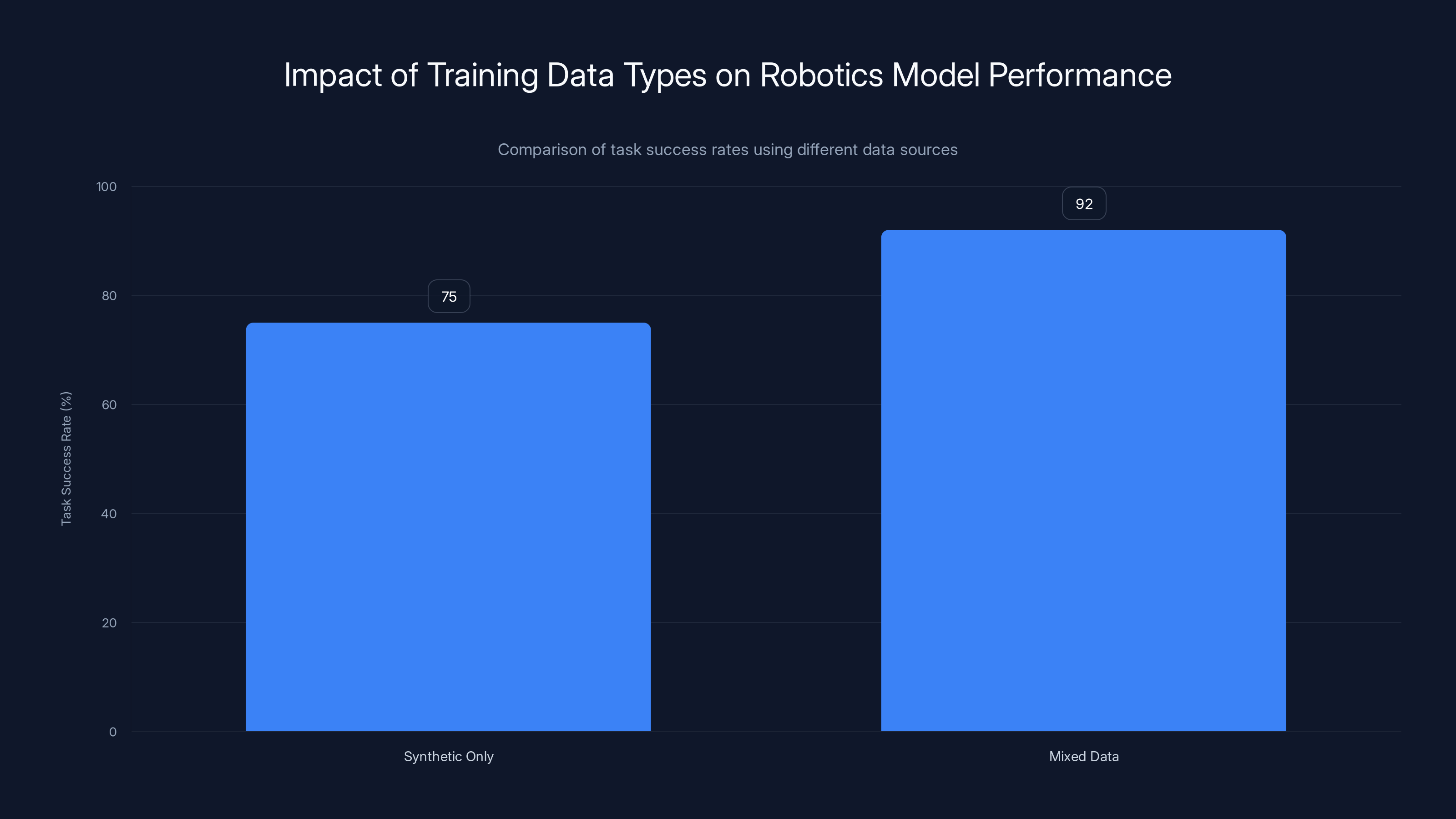

Using a mix of synthetic and real-world data improves task success rate by 17%, highlighting the importance of real-world demonstrations in bridging the reality gap.

What Physical AI Actually Means

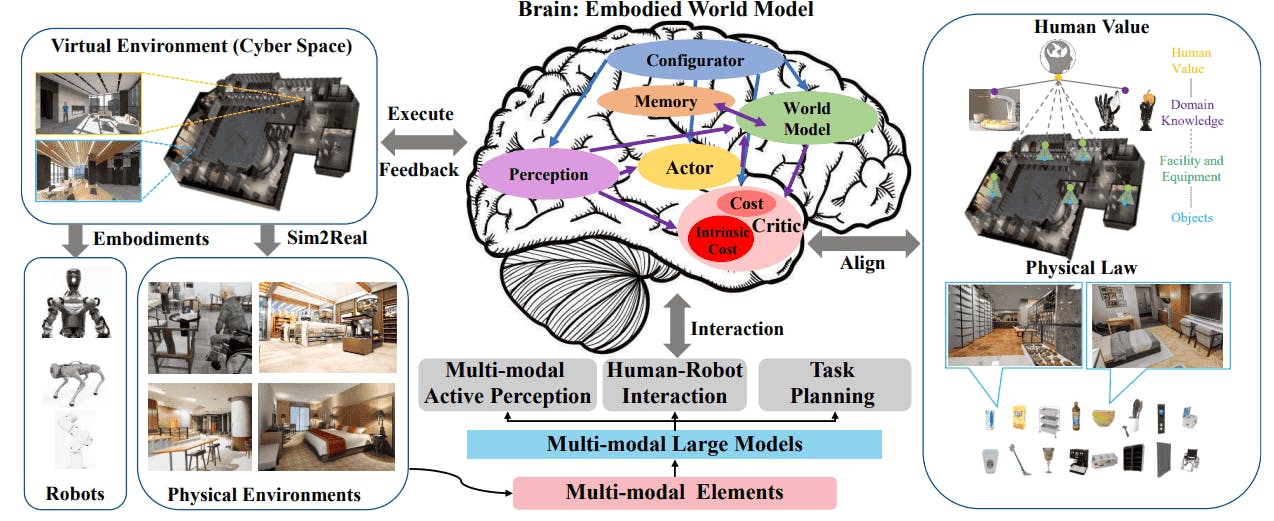

Physical AI sounds abstract until you sit with the definition. It's the idea that AI models can directly guide machines through less structured situations by perceiving, reasoning, and acting with increasing autonomy.

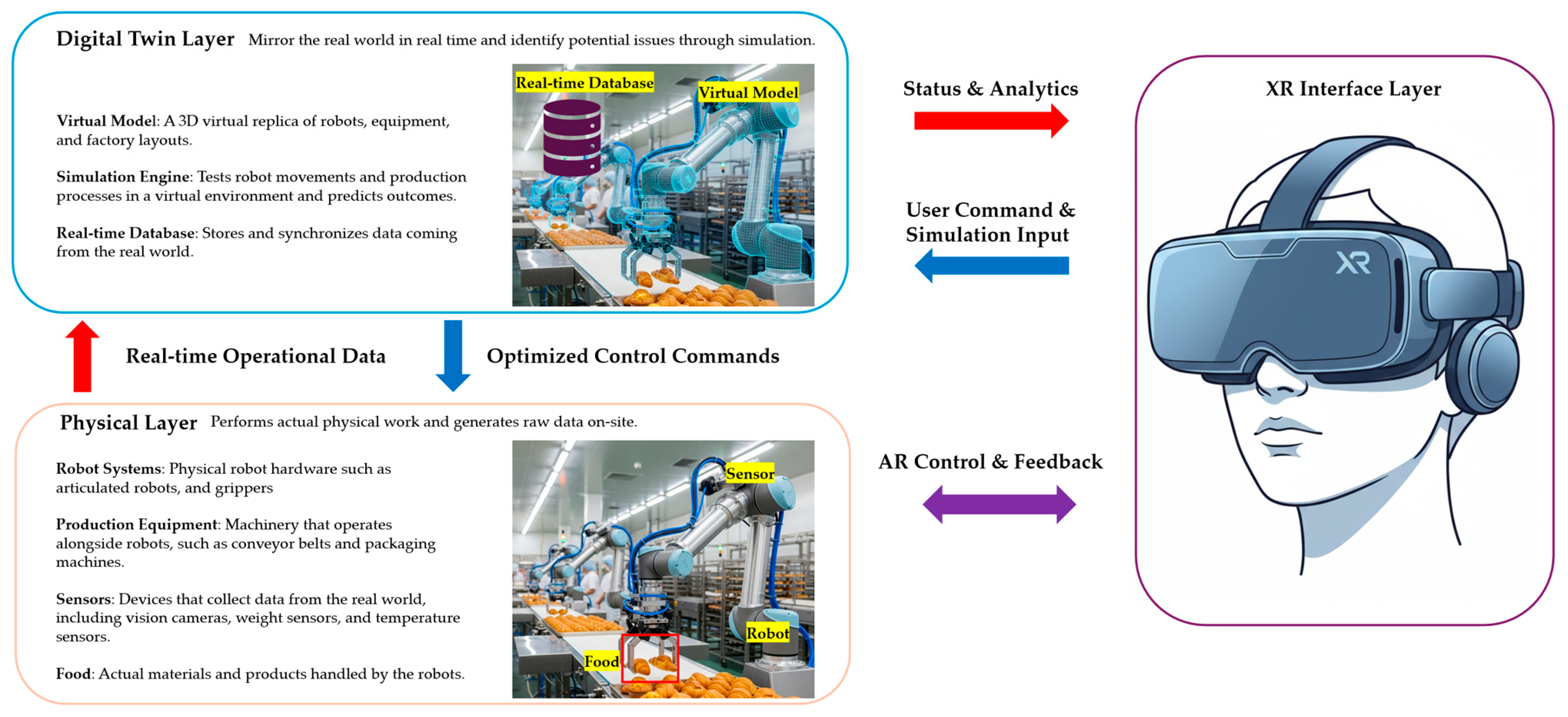

Before this, you had two separate worlds. You had AI—software models that could understand language and process information. And you had robotics—machines following predetermined programs. They didn't really talk to each other. A robot didn't understand instructions the way a language model does. It just executed lines of code.

Physical AI bridges that gap. It means an AI system doesn't just understand a command in theory. It understands how to translate that command into physical action. That's categorically different.

Think about how a human works. Someone tells you "assemble this device carefully." You don't need step-by-step instructions. You understand the goal, you see the parts, you feel how they fit together, and you adapt in real-time. Your hands tell you if something is wrong. Your eyes tell you if something doesn't look right. Your brain integrates all that information and adjusts.

That's what Rho-Alpha is attempting. It's trying to give robots something closer to that integrated understanding.

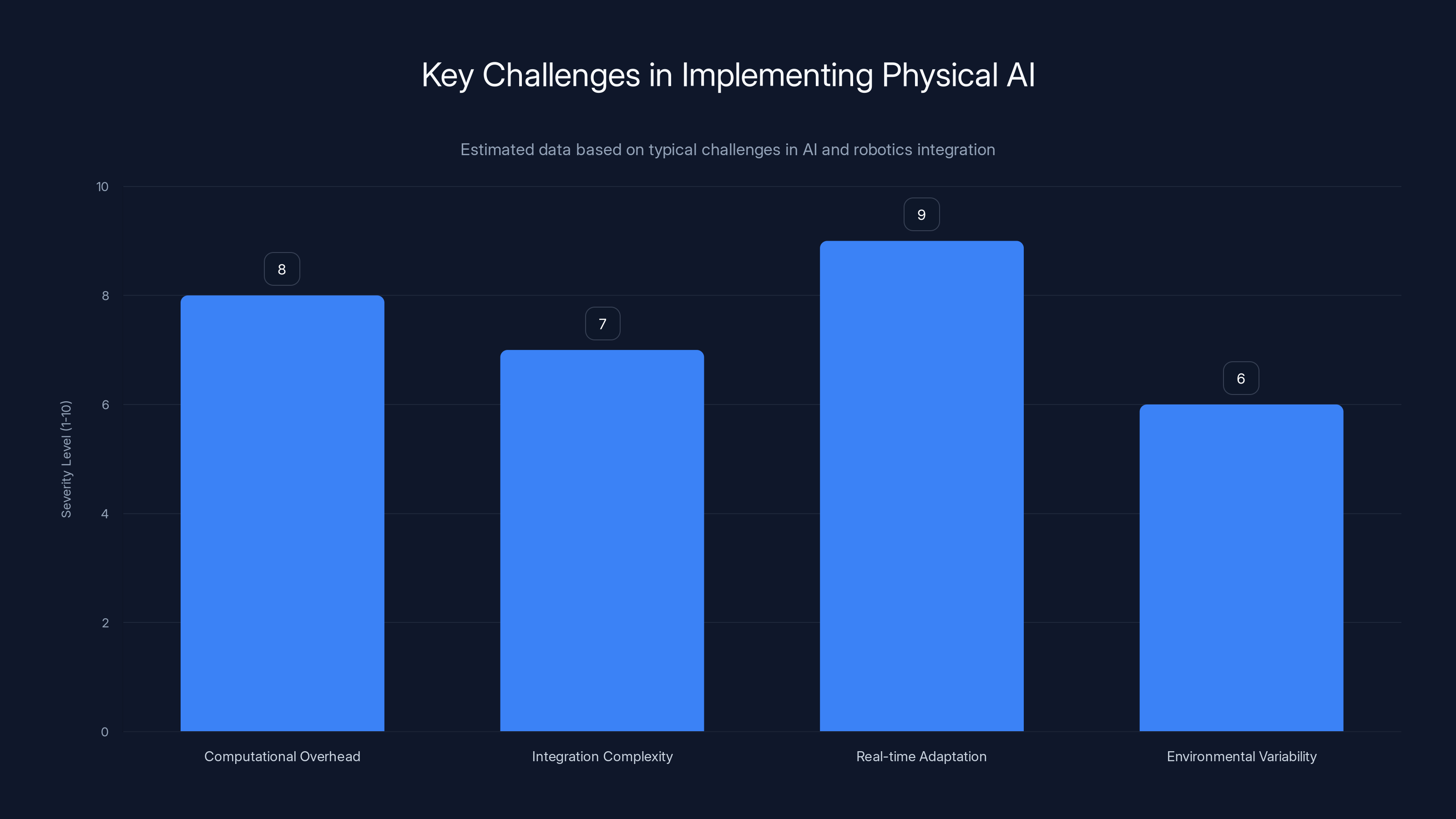

The challenge is enormous. Digital intelligence is fast but brittle. Physical systems are robust but require enormous computational overhead. Bringing them together means solving problems that don't exist in either domain alone.

In manufacturing specifically, this matters because real factories are messy. Parts arrive in boxes where orientation varies. Surfaces wear over time. Material batches differ slightly. Human workers adapt instantly. Robots used to need a human to reprogram them. Physical AI gives robots the ability to adapt themselves.

One critical point: this isn't artificial general intelligence for robots. Rho-Alpha won't learn to do completely novel tasks or operate in entirely new environments. It's trained on specific types of manipulation tasks. But within that domain, it's learning to reason and adapt rather than just execute.

The economic implications are real. Companies spend enormous resources managing variations in manufacturing. If robots can handle more variation, that labor cost drops, and automation becomes viable in more places. That doesn't mean factories go robotless. It means they need fewer human operators making constant adjustments.

Microsoft's approach signals where the industry is heading. Instead of building robots from the ground up, they're starting with foundation models—large AI models trained on diverse data—and specializing them for robotics. It's the strategy that worked for language models and computer vision. Now it's coming to physical systems.

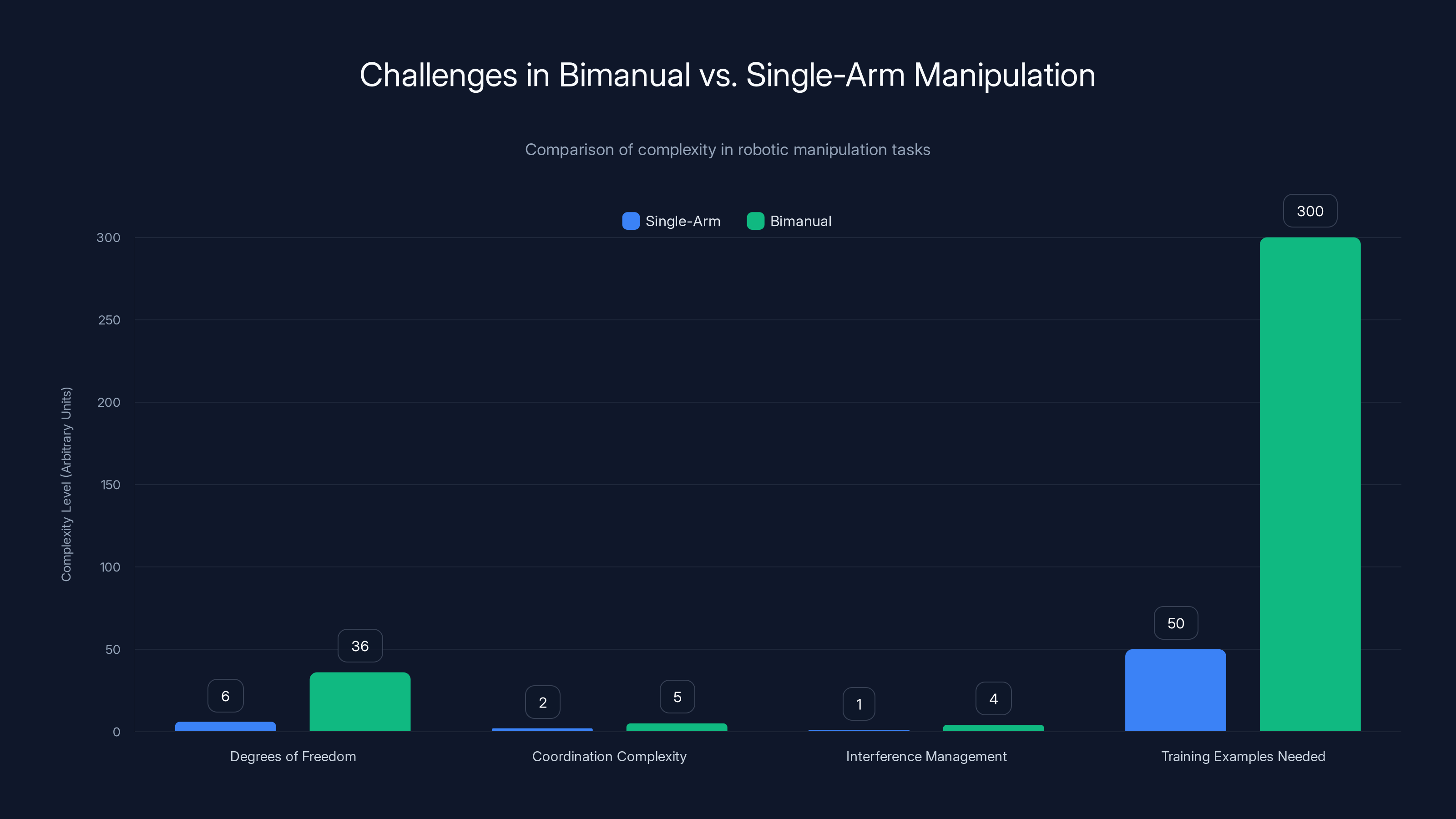

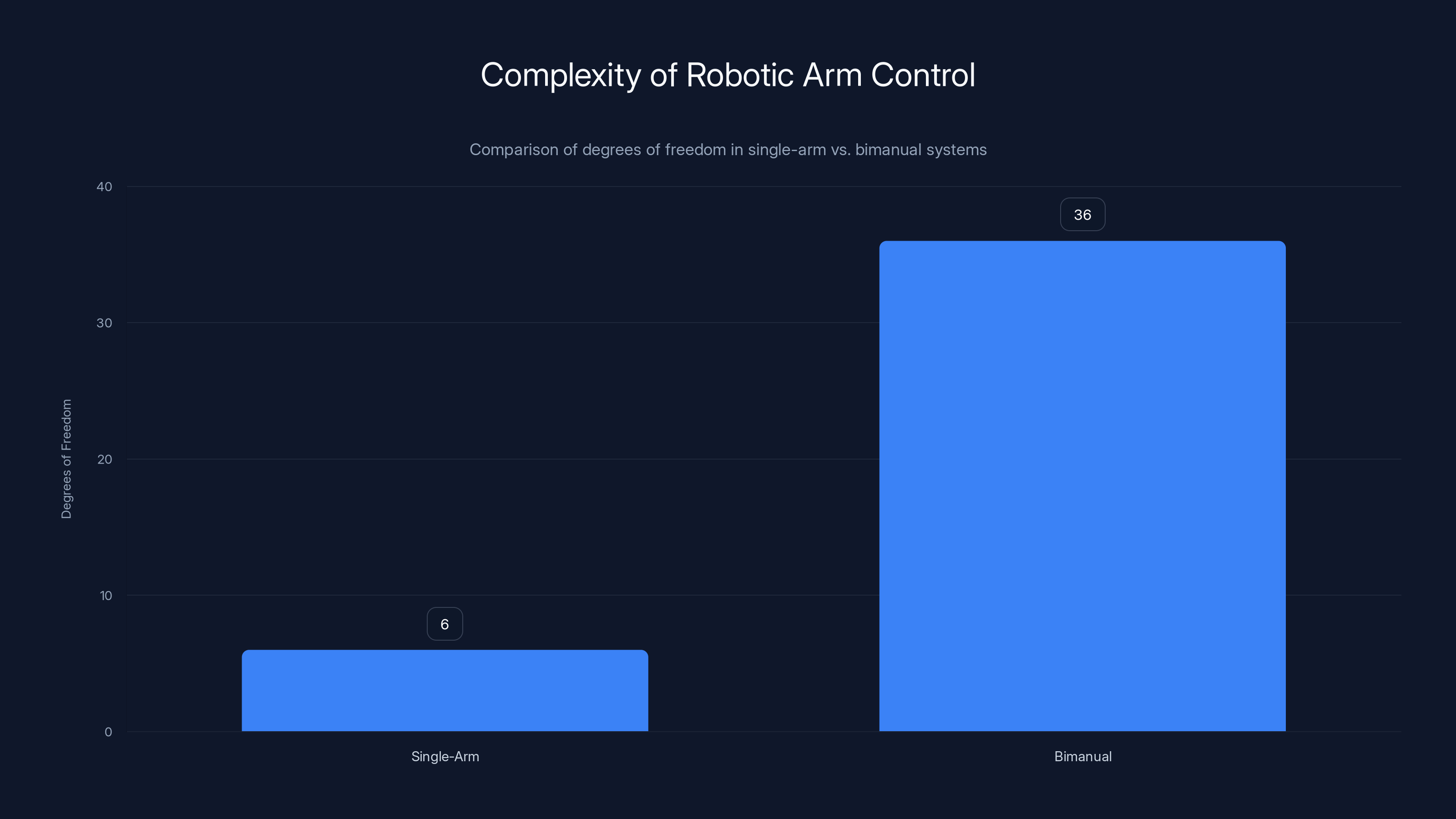

Bimanual manipulation is significantly more complex than single-arm control due to increased degrees of freedom, coordination complexity, and the need for more training examples. (Estimated data)

How Rho-Alpha Translates Language into Motion

The magic of Rho-Alpha starts with language. Microsoft derived it from its Phi vision-language models, which means the system already understands how to process natural language and connect it to visual information.

Here's the sequence: you give Rho-Alpha a command in natural language. Something like "pick up the fragile component and place it in the container gently." The model doesn't just parse those words. It connects them to visual perception. It looks at what's in front of the robot and understands what "fragile" means in context. Is it small? Is it delicate-looking? How should grip pressure change?

Then it translates all that into motor control signals. The robot's arms move according to what the AI learned during training. But here's what's different: it's not following a script. It's reasoning about the task.

This is why the connection between language models and robotics matters so much. Language models are essentially compression engines. They've learned patterns from vast amounts of human text. Those patterns include not just grammar but reasoning, cause and effect, consequences of actions. A language model trained on enough text actually understands in a meaningful way that, if you're being careful with something fragile, you shouldn't move suddenly.

Mapping that understanding to physical action is the hard part, but that's what Rho-Alpha attempts.

The system focuses specifically on bimanual manipulation tasks. That means both arms working together, which is significantly more complex than single-arm control. Bimanual tasks require coordination—one arm stabilizing an object while the other manipulates it, for example. That's where precision meets adaptation. Your hands don't move independently when you're doing something delicate. They're communicating through the object itself.

For Rho-Alpha to handle this, it needs to understand not just individual arm movements but the relationship between movements. One arm's motion constrains the other. If the object rotates differently than expected, both arms need to adjust. The AI learns this relationship through training data that shows successful bimanual tasks.

The neural network architecture likely works something like this: the visual input goes through convolutional layers that extract spatial information. The language input gets processed by transformer layers that understand semantic meaning. These representations get combined, and the output is a sequence of motor commands for each arm.

But the system doesn't commit to a full sequence upfront. It runs in a loop. Step one: compute movement based on current observation and instruction. Step two: execute that movement. Step three: look at the result. Step four: recompute the next movement based on the new observation. This closed-loop approach is crucial because it allows real-time correction.

Training this system requires data that most robotics labs simply don't have. You need thousands of examples of successful bimanual manipulation. You need to capture not just the successful path but the variations and corrections that lead to success. That's where the synthetic data generation comes in.

The Synthetic Data Revolution: Why Simulation Matters

Here's a hard truth about robotics: real training data is expensive and slow to collect. You need actual robots. You need someone to operate them or program them. You need time to run trial after trial. Mistakes and failures damage expensive equipment.

Microsoft solved this by leaning heavily on simulation. Specifically, they used NVIDIA Isaac Sim running on Azure cloud infrastructure. The idea is to generate synthetic trajectories—simulated examples of robots performing tasks—that the real robots can learn from.

This isn't new in theory. Physics engines have existed for decades. But it's new at this scale. Microsoft can generate thousands of examples of bimanual manipulation in simulation, watch what works and what fails, and use that to train the foundation model.

The challenge is the reality gap. Simulation isn't perfectly accurate. Friction varies. Material properties differ. Physics engines make approximations. A robot trained purely on simulation often fails in the real world because the real world doesn't behave exactly like the simulation.

Microsoft addressed this by combining three data sources:

Synthetic data from reinforcement learning: The AI learns directly in simulation how to accomplish tasks. A reward signal guides it toward successful outcomes. This generates thousands of diverse trajectories cheaply.

Real-world demonstrations: They still collected actual robot demonstrations, but used them selectively. These ground-truth examples teach the model what actually works when friction, material properties, and physics behave like they do in reality.

Diverse datasets: They combined demonstrations from commercial robot systems and open-source datasets. This diversity means the model sees many different approaches to the same task, which improves generalization.

The math behind this is worth understanding. Reinforcement learning in simulation generates trajectories

Where γ is a discount factor and r is the reward function. The reward can be shaped to encourage specific behaviors—gentle contact, efficient movement, successful task completion.

Once you have this synthetic data, you combine it with real demonstrations. The model trains on the combined dataset. The synthetic data provides diversity and scale. The real data provides accuracy.

But here's where it gets sophisticated: Rho-Alpha includes human corrective input during deployment. This is the human-in-the-loop component. When the robot is working in reality and makes mistakes, a human operator using teleoperation can take control and show the system the correct approach. The system learns from that correction.

This creates a virtuous cycle. The robot works based on its training. When it fails, humans intervene. Those interventions get added to a growing dataset of real-world examples. Over time, the robot needs fewer human corrections because it's learned from them.

This is actually how robotics scales in practice. You can't collect all your data upfront. You collect data as you deploy, learn from failures, and continuously improve the system.

The partnership with NVIDIA made this possible. Isaac Sim runs on NVIDIA's GPUs, which are essential for physics simulation at scale. On Azure, Microsoft could parallelize the generation of synthetic data across thousands of GPU instances. What would take months on a single machine takes weeks distributed across a cloud.

This infrastructure component is crucial. Physical AI isn't just a software problem. It's a software plus simulation plus hardware problem. Companies that can orchestrate all three—like Microsoft with Azure and NVIDIA hardware—have a structural advantage.

Physical AI faces significant challenges, with real-time adaptation being the most severe. Estimated data highlights these key areas.

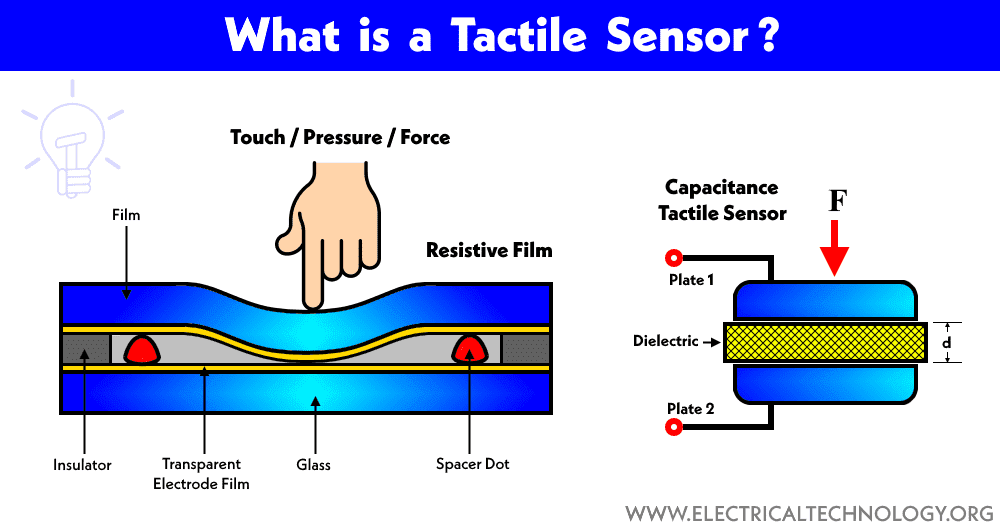

Tactile Sensing: Feeling What You're Doing

Vision gets most of the attention in AI. Language models process text. Computer vision systems interpret images. But robotics has a problem that vision alone can't solve: you need to know how things feel.

Rho-Alpha includes tactile sensing. That means the robot has sensors that can detect pressure, force, texture. When you're assembling something delicate, you don't just watch what you're doing. You feel the resistance. You sense when something is about to break. Your fingers tell you more than your eyes can.

Adding tactile sensing to Rho-Alpha narrows the gap between simulated intelligence and physical reality. It makes the model closer to how human dexterity actually works.

Tactile sensing data is more complex than visual data. An image is a grid of pixels. Tactile data is sparse—only the points where the robot is touching something send information. But that sparsity is also information. Where you're touching tells you about the task. If a pressure sensor on your finger is firing but sensors across the palm are not, you know you're making point contact. That means something about the object's geometry.

Integrating tactile information into a multimodal model requires careful architecture. The model needs to fuse information from three different sources:

- Visual input: What the robot sees

- Tactile input: What the robot touches

- Force/torque input: How much force is being applied

These inputs aren't always available simultaneously. Sometimes the robot is moving with no contact. Sometimes it's applying force. Sometimes it's making delicate contact with no significant force. The model learns to weight these inputs appropriately.

Force sensing is particularly interesting. If you know how much force you're applying, you know something about the material properties. Hard materials accept more force. Fragile materials reject force. The robot learns these relationships through examples in its training data.

Microsoft mentions that force sensing is an ongoing development, which is honest. Integrating all these modalities effectively is hard. Too much weight on tactile information and the robot becomes overly sensitive to noise. Too little and it ignores critical information. The right balance comes from large diverse training datasets.

The practical advantage is significant. Without tactile sensing, a robot might apply too much force and break something or damage a surface. With tactile sensing, the robot can detect resistance and ease up. Without it, the robot has to trust vision alone, which is limited. With it, the robot has another source of truth.

This matters for tasks outside controlled factory environments. In the real world, object geometry varies slightly. Surfaces aren't perfectly smooth. Materials have different properties than expected. Tactile feedback lets robots adapt to these real-world variations.

Research on tactile sensing in AI is relatively young compared to computer vision. There's less data, fewer researchers, less infrastructure. So Rho-Alpha's inclusion of tactile sensing signals that Microsoft believes this capability will become table-stakes in robotics. That's a significant bet.

Bimanual Coordination: Two Arms Are Harder Than One

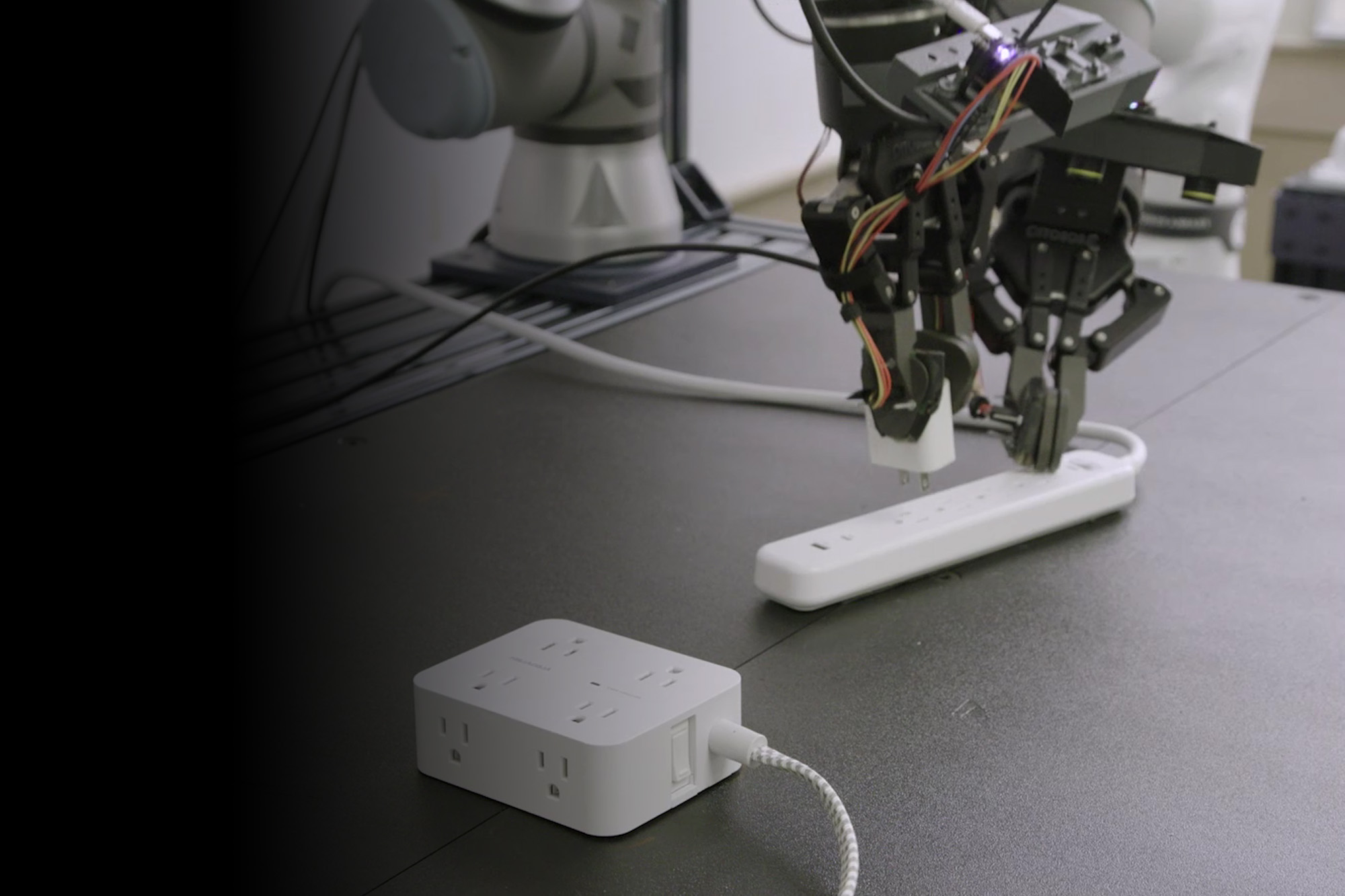

Single-arm robots are common. They're simpler, cheaper, and suitable for many tasks. But some tasks fundamentally require two arms. One stabilizes while the other manipulates. They work in opposition. They handle objects too large for one arm.

Rho-Alpha focuses specifically on bimanual manipulation because it's where complexity meets necessity. Most assembly tasks benefit from two arms. Medical procedures require two hands. Delicate manufacturing often needs fine control from two points.

Bimanual control is exponentially harder than single-arm control. With one arm, you have three translational degrees of freedom (x, y, z) and three rotational degrees of freedom (pitch, roll, yaw). With two arms, you have six times that, plus you need to ensure the arms don't interfere with each other and that their motions are coordinated toward a common goal.

Neural network models handle this through representation learning. The model learns to represent the task in a way that makes coordinated bimanual actions natural. Instead of commanding arm A and arm B separately, the model learns a latent representation of "the task I'm trying to accomplish" and generates actions for both arms that accomplish that task.

Consider an example: inserting a circuit board into a slot. One hand stabilizes the slot while the other guides the board. The insertion angle matters. The forces matter. The sequence matters. A good bimanual model learns that stabilizing the slot comes first, then begins the insertion, adjusting the board as resistance increases.

Training this requires examples where both arms are actually needed. You can't train bimanual control with single-arm examples. So Rho-Alpha's training data specifically includes bimanual demonstrations. Those are harder to collect but more valuable for this specific capability.

The coordination happens through what researchers call "implicit communication." The arms don't communicate through explicit messages. Instead, they respond to the shared task representation and the mutual presence of other forces. If one arm senses high resistance, it implicitly signals to the other arm that they're hitting an obstacle, and the other arm should adjust.

This implicit coordination is learned from data. The model sees successful bimanual trajectories where both arms adjust to obstacles, unexpected geometry, and changes in the task. It learns the pattern of how arms adapt to each other.

Implementing this requires careful sensor synchronization. Both arms need to report their position, force, and tactile information in sync. Any latency between sensors creates discoordination. That's why cloud-based control has limitations for tasks requiring microsecond-level synchronization. Rho-Alpha likely includes local control loops that handle fast feedback, with higher-level reasoning handled by the AI model.

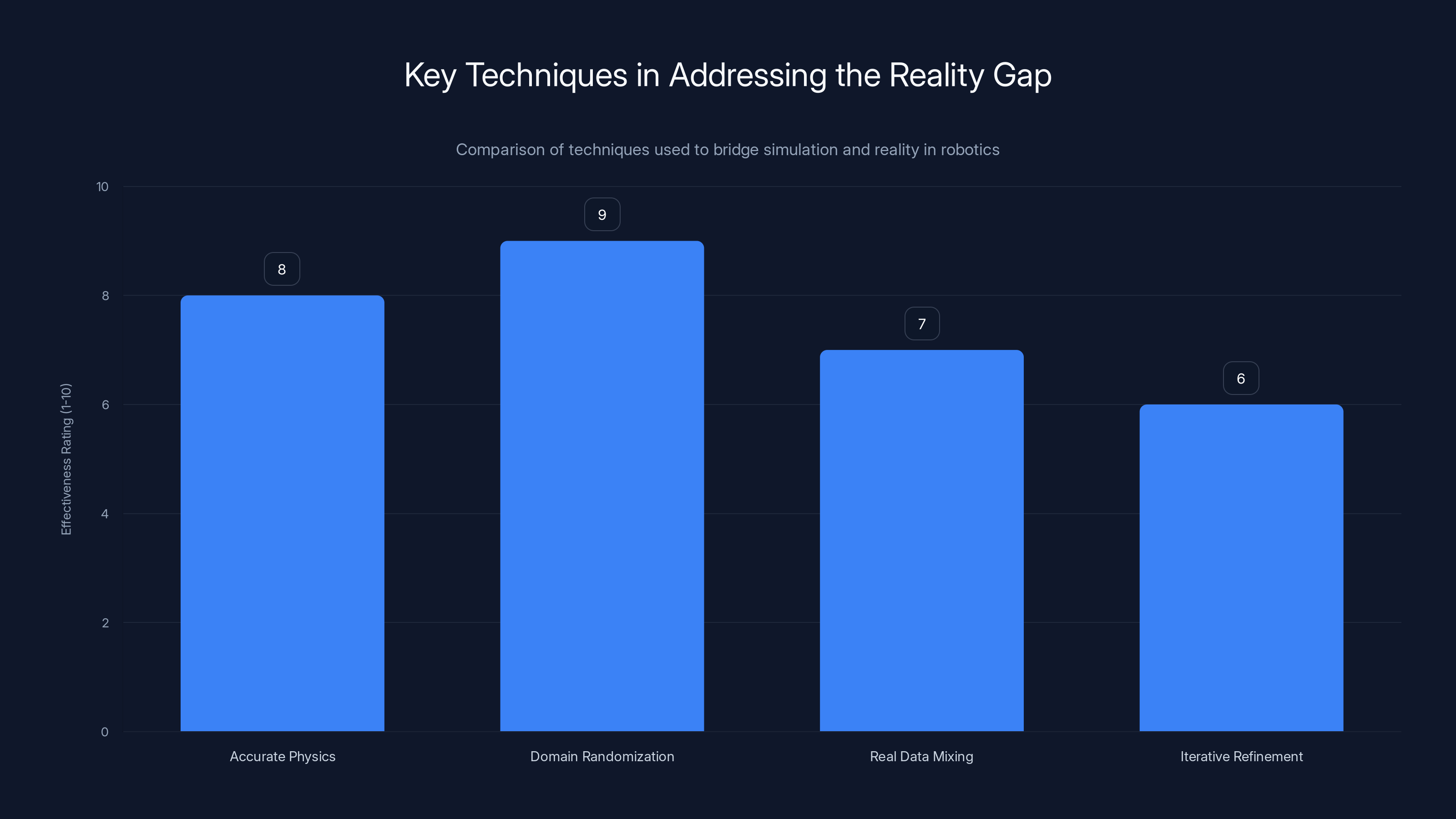

Domain randomization is rated as the most effective technique in addressing the reality gap, followed closely by accurate physics modeling. Estimated data based on typical industry insights.

Training Data: The Bottleneck That Simulation Eases

Large language models train on terabytes of text. Computer vision models train on billions of images. Robotics models train on... much less. Robotics data is scarce because collecting it is hard.

This is the core constraint that Rho-Alpha addresses. You can't collect a billion hours of robot footage the way you can scrape a billion web pages. Real-world robot training is slow and expensive.

Microsoft's solution combines three categories of data:

1. Synthetic data from simulation: This is the bulk of the training data. Isaac Sim generates trajectories algorithmically. The quality depends on how accurate the simulation is and how well the reward signal guides learning. The advantage is scale. Disadvantage is reality gap.

2. Real-world demonstrations: These validate that the synthetic data actually maps to reality. They provide ground truth. A smaller amount of real data mixed with synthetic data often produces better results than purely synthetic data, even if the real data is 1% of the total.

3. Open-source datasets: Public datasets from other robotics labs contribute diversity. They show different approaches to the same task. They reduce the risk that the model overfits to Microsoft's particular robot hardware or setup.

The combination is powerful. A model trained on this mixed dataset generalizes better than one trained on either type alone. The synthetic data provides scale. The real data provides accuracy. The diversity prevents overfitting.

Quantitatively, this approach likely improves performance. Let's say purely synthetic training achieves 75% task success rate. Mixed synthetic and real training might achieve 92%. The additional 17% comes from the model learning the reality gap from real examples.

But here's the challenge: data quality matters more than quantity. One thousand carefully curated demonstrations with proper labeling can be worth more than ten thousand sloppy ones. Rho-Alpha's training data likely includes detailed annotations: what's the goal of this task, what obstacles exist, why did the robot make this movement.

This is where the human-in-the-loop component becomes crucial. As Rho-Alpha deploys and operators provide corrections, those corrections become training data. If a robot is operating 8 hours a day, that's thousands of hours of new data monthly. After a year, the deployed robots have generated millions of new examples.

That's scalable learning. Early versions of Rho-Alpha might need human guidance 30% of the time. After six months of deployment across multiple robots, that percentage might drop to 10%. Not through software updates but through accumulated real-world data.

The challenge of data scarcity explains why robotics has been slower to benefit from AI than software has. Data is the fuel. Software companies can generate unlimited training data. Robotics companies generate data as slowly as their robots operate. Scale comes from many robots running many hours, and that takes time.

Microsoft's approach through cloud infrastructure partially solves this. They can simulate fast—compressed time in simulation means thousands of hours of simulated experience in weeks. But deploying to real robots is still limited by the number of robots and the hours they operate.

This is why partnerships matter. Microsoft's collaboration with robotics labs and manufacturers lets them access more deployment data than they could generate alone. That data, properly anonymized and aggregated, improves the central model that all deployed robots use.

The Human-in-the-Loop Learning System

Rho-Alpha includes a critical component that many robotics systems overlook: human feedback during operation. This isn't supervision—it's active learning. The robot works autonomously but can be corrected in real-time by human operators.

Here's how it works: the robot attempts a task based on its current knowledge. If it starts going wrong, an operator can take control via teleoperation. The operator shows the robot the correct approach. The system observes this correction and learns from it.

This creates several benefits:

Real-time safety: If the robot is about to break something or injure someone, a human can immediately intervene. That's essential for deployment in shared spaces.

Data generation: Every correction is a new data point showing what the correct action is. That data improves the model over time.

Operator confidence: Knowing you can take control if something goes wrong makes operators more willing to trust the system. That reduces the psychological burden of deploying automation.

Graceful failure modes: Instead of the robot getting stuck or causing damage, human intervention resolves the situation. The system learns from the resolution.

The technical challenge is making teleoperation smooth and intuitive. The human operator needs to feel like they're controlling the robot directly, not fighting lag or interface complexity. That requires low latency and natural control schemes.

For bimanual tasks, this is particularly complex. Controlling two arms simultaneously is harder than controlling one. The best interfaces often let the human control one arm while the robot handles the other, or provide high-level goal commands that the robot executes bimanually.

Microsoft's architecture likely separates control into layers. The lowest layer is direct motor control—what you'd use for teleoperation. A higher layer is learned behavior—what the AI does when operating autonomously. When the human takes over, they might drop to the lower layer. When they release control, the system returns to the learned behavior.

The learning from corrections could work like this: the human demonstrates correct action. The system records the trajectory—the sequence of positions and forces over time. It compares this to what it would have done. The difference highlights what it got wrong. Over many such corrections, the model's policy improves.

This approach scales better than traditional supervised learning. You don't need to pre-label all your data. The robot learns on the job from corrections. Operators don't need special training in data annotation. They just do their job normally and the system learns.

It's also more adaptive. If task requirements change—a new product starts being assembled, material properties change—the robot learns the new requirements from operator corrections. You don't need to retrain the entire model. Incremental corrections drive incremental improvement.

The downside is that this approach requires a human in the loop for the first phase of deployment. You can't fully automate immediately. But that's actually realistic. Most automation deployments involve a period where humans and machines work together.

Bimanual robotic systems have six times the degrees of freedom compared to single-arm systems, highlighting the increased complexity in control and coordination.

Addressing the Reality Gap Problem

Simulation is powerful but flawed. Real physics is complex. Friction varies with material, temperature, humidity. Shapes have manufacturing tolerances. Dynamics are nonlinear and chaotic at scale.

Microsoft acknowledges this challenge directly. Generating synthetic data is great, but if the synthetic data doesn't match reality, the robot trained on it will fail in the real world.

Their solution is multifaceted:

Accurate physics: Isaac Sim uses NVIDIA's Phys X engine, which models realistic physics including friction, collisions, contact dynamics. It's not perfect but it's reasonably accurate for manipulation tasks.

Domain randomization: During simulation, the system randomizes parameters. Different friction values, different material properties, different object geometries. The robot learns to handle variation rather than overfitting to specific conditions.

Real data mixing: Combining synthetic data with real data teaches the model the systematic differences between simulation and reality. The model learns to map simulated experience to real outcomes.

Iterative refinement: As the robot operates in reality, failures highlight where the simulation was inaccurate. That information can feed back into improving the simulation model or expanding the real training data.

Domain randomization is worth understanding. Instead of training a robot on the exact scenario it will face, you train it on thousands of variations. Robot 1 has friction coefficient 0.3. Robot 2 has 0.5. Object 1 is wood. Object 2 is metal. Object shapes vary slightly. By seeing all this variation during training, the robot learns robust policies that work across conditions.

Mathematically, this is a form of regularization. Instead of minimizing loss on specific examples, you minimize expected loss across a distribution of variations:

Where θ are the model parameters, p represents parameter variations, and P is the distribution of parameters. This pushes the learned policy away from overfitting to specifics.

The effectiveness of this approach is empirically validated in robotics. A robot trained with domain randomization in simulation often transfers to real-world tasks with minimal real-world training data. Without domain randomization, the gap is much larger.

But reality gaps aren't fully solvable. There will always be situations the simulation didn't capture. That's where the human-in-the-loop learning kicks in. The robot encounters a scenario it struggled with. A human corrects it. Now the model learns this specific edge case.

Over time, the robot handles more and more edge cases until it rarely needs human correction. That's the practical path to deployed physical AI. Not perfect simulation. Not perfect models. But good-enough foundations that learn from real-world experience.

Bimanual Vs. Single-Arm: When You Need Two

Not every task needs two arms. Rho-Alpha focuses on bimanual tasks, which means it's not a general solution. It's specialized for complex manipulation that requires coordination.

When should you use bimanual robots? Several categories stand out:

Assembly tasks: Most consumer electronics assembly requires two hands—one holding the chassis, the other installing components. Mobile phone manufacturing, computer assembly, Io T device production all benefit from bimanual capability.

Delicate material handling: Pharmaceuticals, semiconductors, optics. These require one hand to stabilize and one to manipulate precisely.

Large object manipulation: Some parts are too large for one robot arm to handle safely. Two arms provide distributed control and redundancy.

Precision positioning: When tolerances are tight—electronics with connectors, precision mechanisms—two arms allow control from multiple points, reducing error.

Tasks involving both hands in humans: If humans use both hands to do a job, there's usually a good reason. It often means the task is genuinely bimanual.

Single-arm robots remain dominant because they're simpler and cheaper. The question is whether physical AI like Rho-Alpha changes that calculus. If bimanual robots with AI can handle more tasks autonomously, the cost-benefit equation shifts.

The current state is transition. Many factories use one single-arm robot per task or require human workers. The future likely involves more bimanual systems because they can handle more task variation and complexity. Physical AI accelerates that transition by making bimanual robots more adaptable.

Rho-Alpha isn't the end of this story. It's an early demonstration. Over time, bimanual systems will become more capable, cheaper, and more common. Single-arm systems will handle tasks that genuinely don't need two arms. Mixed environments with both types will become standard.

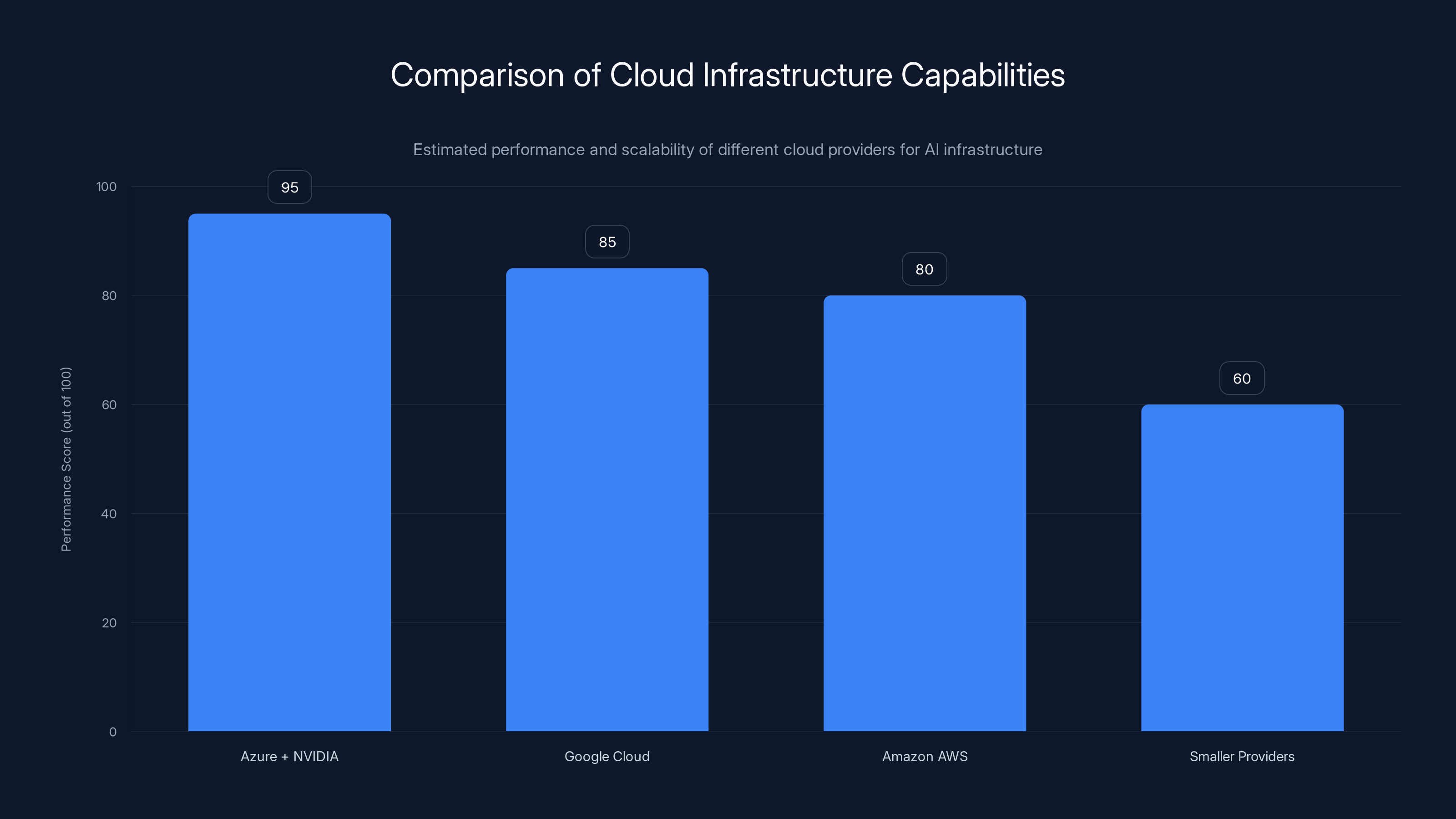

Azure combined with NVIDIA GPUs offers the highest performance for AI infrastructure, making it ideal for large-scale simulations and model training. Estimated data.

The Infrastructure Required: Why Azure and NVIDIA Matter

Building Rho-Alpha required infrastructure that most companies don't have: cloud GPUs for simulation, model training at scale, data aggregation from multiple sources, and deployment infrastructure to multiple robots.

Microsoft leveraged two key components:

Azure cloud: Provides the compute capacity to run thousands of simulations in parallel. That's what makes generating 100,000+ synthetic trajectories feasible in reasonable time.

NVIDIA Isaac Sim: Purpose-built physics simulation running on NVIDIA GPUs. The combination of specialized simulation software and GPU hardware is much faster than CPU-based simulation.

The partnership matters. Isaac Sim is optimized for NVIDIA GPUs, which run on Azure. The system was designed for this specific combination. Using different components means lower performance.

This creates a structural advantage for companies that can orchestrate this infrastructure. Microsoft, Google, Amazon, or other cloud providers can build physical AI systems. Smaller robotics companies without this infrastructure face challenges. They can't simulate at the same scale. They have to rely more on real-world data collection.

That doesn't mean smaller companies are locked out. They can use cloud services. But there's a disadvantage in latency, cost, and convenience when you're not the company running the infrastructure.

The compute requirements are significant. Training large foundation models requires thousands of GPU hours. Generating synthetic data in parallel requires even more compute. That expense is why physical AI is emerging from tech giants and well-funded startups, not from individual labs.

This dynamic echoes what happened with large language models. Foundation models require enormous compute. That capability concentrates at companies and labs with resources. They can then offer API access to others. We'll likely see the same pattern for physical AI. Microsoft, Google, and others will develop foundation models. They'll offer robots using those models through cloud APIs or partnerships.

Applications Beyond Manufacturing

While Rho-Alpha focuses on manufacturing, physical AI has applications far beyond assembly lines.

Healthcare: Surgical robots require incredible precision and delicate touch control. Physical AI improves adaptation to patient anatomy variations and real-time feedback.

Logistics: Warehouse picking and sorting involve unexpected object shapes and orientations. Physical AI robots adapt rather than fail.

Food production: Handling varied produce, different ripeness levels, different sizes. Requires tactile sensing and adaptation.

Materials handling: Fragile goods, varied packaging, different weights. Physical AI robots handle variation without human intervention.

Research and development: Labs performing chemistry, biology, physics research need robots that can adapt experiments in real-time based on observations.

Service robotics: Robots that work in human environments. Cleaning, tidying, organizing. These environments are inherently unstructured and varied.

The common thread is unstructured environments with variation. Anywhere that humans need adaptability, physical AI helps. Anywhere that precise scripting isn't sufficient, physical AI has advantages.

The timeline for deployment in these fields varies. Surgery is heavily regulated and cautious about automation. Consumer applications might move faster. Manufacturing is familiar with robotics and will likely adopt physical AI robots earliest.

But the direction is clear. As physical AI improves, applications broaden. Tasks that seemed like human specialties become automatable. The jobs that remain are those that require even more complex judgment, creativity, or human interaction.

Challenges and Limitations of Current Physical AI

Rho-Alpha is impressive but it's not a complete solution. Several limitations matter:

Task specificity: Rho-Alpha is trained on bimanual manipulation tasks. It won't suddenly become good at other types of robotics work. Generalization across different task types is limited.

Environmental variation: The system handles variation within its training distribution. Novel environments or scenarios outside that distribution will struggle. That's the fundamental challenge of machine learning.

Brittleness in edge cases: All learning systems fail on sufficiently novel situations. Rho-Alpha will encounter tasks or scenarios it was never trained on. Those will fail until humans correct them.

Hardware specificity: A model trained on one robot arm might not directly transfer to a different arm with different dynamics. Transfer learning helps but isn't perfect.

Simulation accuracy: The reality gap remains. Simulation gets better but never perfectly matches reality for every scenario.

Cost and complexity: Deploying physical AI requires infrastructure, expertise, and careful system design. It's not easy to adopt for small companies or labs.

Data privacy: Training on proprietary manufacturing processes can expose sensitive information. Data aggregation requires careful handling of intellectual property.

These limitations don't invalidate the approach. They're real constraints that affect deployment. Good engineering acknowledges constraints and designs around them. Rho-Alpha likely includes safeguards for edge cases, fallbacks to teleoperation, and monitoring to detect when the system is uncertain.

The path forward involves all three: better models, better simulation, and better real-world deployment infrastructure. As all three improve, the capabilities expand.

Market Implications and Competition

Rho-Alpha's announcement signals that the robotics industry is entering a new era. Instead of companies building robots from scratch, they'll license foundation models and specialize them for specific applications.

That's a paradigm shift. Historically, robotics required deep domain expertise. You needed to understand mechanics, controls, sensing, programming. Physical AI abstracts much of that away. You still need expertise in your specific application, but the core robotics problem is solved by the foundation model.

Competitors will emerge. Tesla's humanoid robot uses some physical AI principles. Boston Dynamics develops robots with advanced perception and control. Numerous startups are building specialized physical AI systems.

But Microsoft's advantage is foundation model expertise plus cloud infrastructure plus partnerships with manufacturers. They can iterate fast and deploy at scale. That's a strong position.

The economic impact is significant. If bimanual robots become vastly more capable and adaptable, adoption accelerates. Factory automation expands to smaller companies, to less structured tasks, to environments where robots previously couldn't work. That drives demand for the physical AI systems that enable this.

The jobs impact is complex. Some jobs disappear as robots handle tasks humans currently do. New jobs emerge in robot operation, maintenance, data collection, model improvement. The net effect depends on how fast change happens and how successfully displaced workers transition.

For enterprises, this is relevant now. If you're in manufacturing, you should be evaluating physical AI robots for tasks currently done by humans or single-function automation. If you're in logistics, healthcare, or food production, similar analysis applies.

The companies that adopt early and learn to integrate physical AI robots with their processes will gain competitive advantages in cost, flexibility, and quality.

Future Directions for Physical AI

Rho-Alpha is a starting point. Where does physical AI go from here?

Multi-task learning: Instead of training a model for specific tasks, train one model that can handle many related tasks and adapt between them. That's more flexible and more like human intelligence.

Longer horizons: Current systems handle short manipulation sequences. Future systems will handle longer task sequences, planning across multiple steps, recovering from failures mid-sequence.

General manipulation: Move from bimanual to broader manipulation capabilities. Single-arm tasks. Locomotion and manipulation combined. Systems that adapt to completely new tasks with minimal examples.

Human-robot collaboration: Better physical AI enables safer, more natural human-robot interaction. Robots that understand human intentions and adapt to human preferences.

Continuous learning: Systems that improve constantly from field experience rather than requiring periodic retraining and updates.

Reasoning: Current systems learn patterns. Future systems might develop something closer to reasoning—understanding why a task failed and how to fix it conceptually rather than just from examples.

These advances require progress in multiple areas: better sensors, faster compute, larger datasets, improved algorithms, and better frameworks for learning from interaction.

The trajectory suggests that physical AI will become more capable, more general, and more accessible over the next five to ten years. The question isn't whether this happens, but how fast and with what implications for society.

Practical Implications for Manufacturers

If you're manufacturing products with assembly steps, bimanual manipulation tasks, or variable inputs, Rho-Alpha and similar systems matter to you.

Here's how to think about it:

Audit your process: Identify tasks currently done by humans where variation is the main reason robots can't do them. These are candidates for physical AI.

Quantify the benefit: What would it save if you could automate these tasks? Calculate ROI including retraining costs, robot costs, deployment time, and risk.

Plan for integration: Physical AI robots won't replace your entire workforce. They'll handle specific tasks. Plan for mixed human-robot environments.

Invest in data infrastructure: Your deployments will generate data. That data is valuable for continuously improving the robots. Build systems to capture, clean, and learn from it.

Partner strategically: You probably don't want to build physical AI from scratch. Partner with platform providers like Microsoft or specialized robotics companies.

Start small: Pilot one application before scaling. Learn what works, what doesn't, what data you need. Then expand.

Train operators: Robots operating autonomously still need human oversight. Operators need to understand the system, its limitations, and how to intervene when needed.

The companies that move fastest will gain competitive advantages. But moving too fast without careful planning creates problems. The sweet spot is deliberate adoption with clear value targets and careful integration.

The Broader Context: AI Evolving Beyond Screens

For years, AI meant software. Language models, image recognition, recommendation systems. All operating on computers, on servers, on the cloud.

Physical AI represents a fundamental expansion. AI that affects the real world. That picks things up, assembles them, handles them. That requires precision and adaptation.

This expansion was inevitable. AI got better until it made sense to use it for anything you could. Now we're seeing that happen in robotics.

But physical AI is harder than software AI in important ways. The reality gap exists. Robots break things. Failures have physical consequences. Deployment is more complex. Data collection is slower.

These challenges mean physical AI will progress differently than software AI. It won't scale as fast. It will be more specialized, longer to deploy. But when it works, it works powerfully because it affects the real world.

Microsoft's bet on physical AI signals confidence that this domain is ready for foundation models and large-scale investment. If they're right, the next five years will see rapid progress in robotics. If they're wrong, it'll be slower.

Historically, Microsoft bets on infrastructure—cloud computing, AI platforms, development tools. They're not betting on being the best robotics company. They're betting on being the infrastructure layer for robotics AI. That's a stronger position historically.

The broader lesson is that AI is maturing. It's moving from being a software phenomenon to being infrastructure for everything. Cameras use AI. Robots use AI. Factories use AI. Cars use AI. The trend is clear.

Physical AI is a natural evolution of this trend. Using advanced AI to control physical systems. Adapting those systems to real-world complexity. Learning from real-world failures.

Rho-Alpha is one step in a much longer journey. But it's a significant step, and it opens doors that were previously closed.

Key Takeaways and What's Next

Microsoft's Rho-Alpha represents a meaningful advance in physical AI for robots, specifically in bimanual manipulation tasks. The system combines language understanding, visual perception, and tactile sensing to create robots that can adapt to variation and complexity beyond what traditional industrial robots handle.

The core innovation isn't any single component. It's the integration: training on synthetic data, combining that with real examples, including human feedback loops, and deploying systems that learn continuously from real-world experience.

For manufacturers, this matters because it expands what can be automated. For the robotics industry, it signals the direction: foundation models and specialization, not custom development from scratch. For society, it raises questions about automation's pace and impact.

The technical challenges are substantial but addressable. The reality gap exists but is being narrowed. Edge cases will occur but can be handled with human intervention and continuous learning. Cost is high but will decrease with scale.

The timeline is worth considering. Rho-Alpha is research that's being productized. We'll likely see commercial versions within one to two years. Broader adoption will take longer as industries adapt and supply chains develop.

If you're in manufacturing, the question isn't whether to adopt physical AI—it's when and which applications to target first. If you're in robotics, the question is whether to build your own physical AI foundation or partner with a platform provider. If you're in other industries, similar analysis applies to your specific automation challenges.

Physical AI is coming. Rho-Alpha is an early but significant signal that the technology is ready for real-world deployment. The robots that emerge from this generation of work will be more capable, more adaptable, and more useful than anything that came before.

FAQ

What exactly is physical AI and how does it differ from traditional robotics?

Physical AI refers to AI systems that can perceive their environment, reason about tasks, and execute physical actions with increasing autonomy, rather than following fixed programs. Traditional robotics relies on predetermined instructions for each task—if a component is slightly rotated, the robot fails. Physical AI robots can adapt to variations because they understand goals and adjust their actions based on real-time feedback. The key difference is reasoning versus programming: traditional robots execute scripts, while physical AI robots understand and adapt.

How does Rho-Alpha use synthetic data for training if it's not as accurate as real data?

Rho-Alpha combines three data sources to overcome the accuracy gap: synthetic data generated through reinforcement learning in simulation provides scale and diversity, real-world demonstrations provide ground truth accuracy, and open-source datasets provide variety and prevent overfitting to one approach. The synthetic data teaches the system general patterns about manipulation tasks. The real data teaches it how those patterns manifest in reality. Together, they create more robust models than either alone. Domain randomization during simulation training helps the robot learn to handle variation, making it more likely to transfer successfully to real-world scenarios.

What makes bimanual (two-armed) manipulation so much harder than single-arm control?

Bimanual manipulation requires coordinating six times the degrees of freedom as single-arm control, plus ensuring the arms don't interfere with each other and work toward the same goal. For example, inserting a circuit board requires one hand to stabilize the connector while the other guides the board at precise angles. The arms must respond to each other's forces implicitly—if one encounters resistance, the other must adjust. Training bimanual systems requires examples where both arms are essential, not single-arm examples adapted to two arms. This makes collecting quality training data more challenging but necessary for true bimanual capability.

How does human teleoperation feedback improve the AI model over time?

When Rho-Alpha operates autonomously and encounters a task it doesn't handle well, a human operator can take control via teleoperation and demonstrate the correct approach. The system records what the human did—the exact sequence of arm positions, forces, and tactile inputs. By comparing its own attempt to the human's approach, the model identifies what it got wrong. Over many such corrections accumulated across multiple deployed robots, the model learns these edge cases and improves. This creates a virtuous cycle: the robot works until it fails, humans show the correct way, the robot learns from corrections and fails less often.

What's the reality gap in simulation, and how does Microsoft address it?

The reality gap is the difference between simulated physics and actual physics. Friction coefficients vary in reality. Materials have unexpected properties. Manufacturing tolerances create variations. Simulated robots often fail in the real world because they learned in simplified conditions. Microsoft addresses this through domain randomization (training with varied friction values, materials, and geometries), mixing real data with synthetic data, and human-in-the-loop learning where deployed robots correct errors. This multi-layered approach doesn't eliminate the gap but narrows it enough for practical deployment.

What types of manufacturing tasks would benefit most from systems like Rho-Alpha?

Bimanual systems benefit tasks where one hand stabilizes while the other manipulates—electronics assembly, pharmaceutical handling, precision mechanisms, delicate materials like optics or semiconductors. They also excel with large objects requiring distributed control, tasks with tight tolerances, and jobs where humans naturally use both hands. Industries like consumer electronics, automotive assembly, medical device manufacturing, and food processing are ideal early adopters. The key indicator is whether human workers currently use both hands for the task—that usually signals genuine need for bimanual capability.

Why does Rho-Alpha require cloud infrastructure and why does that matter?

Generating tens of thousands of synthetic robot trajectories requires parallel computing at scale. Isaac Sim running on thousands of NVIDIA GPUs generates simulation data far faster than would be possible on single machines. Training large foundation models requires distributed GPU compute across cloud infrastructure. This isn't just convenient—it's necessary for the scale of computation involved. The advantage for Microsoft and similar companies is structural: they own the infrastructure and can iterate faster than competitors without it. Smaller companies must use cloud services, which adds latency and cost but remains viable.

Can Rho-Alpha handle completely novel tasks it wasn't trained on?

No, Rho-Alpha will struggle with tasks outside its training distribution. It was trained on bimanual manipulation tasks within certain categories. Entirely novel task types, environments it never saw during training, or edge cases outside its training data will cause failures. That's a fundamental limitation of machine learning models. The system is designed to handle variation within its training domain—different object orientations, unexpected friction, minor environmental changes—but novel tasks require human intervention or retraining on examples of those tasks. This is why the human-in-the-loop component is essential for real deployment.

What are the main limitations and failure modes of current physical AI systems?

Key limitations include task specificity (models trained for specific tasks don't automatically generalize), environmental constraints (the system only handles variation within its training distribution), hardware specificity (models trained on one robot arm don't directly transfer to different hardware), simulation inaccuracy (the reality gap remains), brittleness in edge cases (unexpected scenarios cause failures), high deployment cost and complexity, and data privacy concerns when aggregating manufacturing process data. Deployed systems require careful safety design with human override capability, continuous monitoring for failure detection, and explicit communication about what the system can and cannot do.

How do manufacturing companies start evaluating physical AI for their operations?

Start by auditing your production line to identify tasks currently requiring human workers that involve handling variation or complexity. Calculate the ROI including robot costs, deployment time, worker retraining, and risk mitigation. Pilot one application rather than trying to automate everything at once—learn what works and what data infrastructure you need before scaling. Build partnerships with robot platforms rather than developing in-house unless you have specific robotics expertise. Plan for mixed human-robot environments where humans handle exceptions and robots handle routine tasks. Invest in data capture systems because your deployed robots will generate valuable data for continuous improvement.

What does the future of physical AI likely look like over the next 5-10 years?

Physical AI will become more capable (handling longer task sequences, more complex reasoning), more general (adapting to a wider range of tasks), and more accessible (lower cost, easier deployment for smaller companies). You'll likely see multi-task foundation models that can handle related tasks and rapidly adapt to new ones. Human-robot collaboration will improve as systems better understand human intentions. Continuous learning from deployed systems will accelerate improvement cycles. The technology will expand beyond manufacturing to logistics, healthcare, food production, and service robotics. The constraint will shift from pure capability to deployment, integration, and workforce adaptation. Companies that adopt early and learn to integrate physical AI robots into their processes will gain competitive advantages.

Thanks for reading. The future of manufacturing and robotics is being shaped right now by advances like Rho-Alpha. If you're involved in any industry affected by automation, understanding this technology and its implications isn't optional—it's essential strategic knowledge.

For teams looking to automate workflows, document complex processes, or generate reports and presentations faster, Runable provides an AI-powered platform that automates content creation and workflow optimization. While Runable focuses on software automation rather than physical robotics, it demonstrates the same principle: AI adapting to your specific needs and handling complexity that would otherwise require extensive manual work. Runable starts at $9/month and can save teams significant time on documentation, reporting, and presentation creation.

The convergence of physical AI in robotics and software AI in automation tools represents a broader trend: intelligent systems handling increasingly complex tasks with less human intervention. Understanding both spaces helps you navigate the transformation ahead.

Related Articles

- Physical AI: The $90M Ethernovia Bet Reshaping Robotics [2025]

- Skild AI Hits $14B Valuation: Robotics Foundation Models Explained [2025]

- The AI Lab Monetization Scale: Rating Which AI Companies Actually Want Money [2025]

- Boston Dynamics Atlas Robot: The Future of Factory Automation [2025]

- Humans& AI Coordination Models: The Next Frontier Beyond Chat [2025]

- Tesla Optimus: Elon Musk's Humanoid Robot Promise Explained [2025]

![Microsoft Rho-Alpha: Physical AI Robots Beyond Factory Floors [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/microsoft-rho-alpha-physical-ai-robots-beyond-factory-floors/image-1-1769371746530.jpg)