Boston Dynamics Atlas Robot: The Future of Factory Automation [2025]

Imagine a robot that never calls in sick. Never complains about overtime. Never needs a bathroom break. That's not science fiction anymore—it's happening right now on real factory floors.

Boston Dynamics, the robotics company owned by Hyundai, just kicked off mass production of its Atlas robot, and the implications are enormous. After nearly a decade of research and refinement, the company is shipping units to manufacturers who need to solve one specific problem: there aren't enough humans willing to do dangerous, repetitive work in factories.

But here's the thing—this isn't about robots "taking our jobs" in the dystopian sense everyone worries about. It's way more nuanced than that.

Atlas is purpose-built for manufacturing environments. It's not designed to make breakfast, fold your socks, or have a conversation with you. It's engineered to perform highly specific, physically demanding tasks that would otherwise require hiring humans for work that's either dangerous, tedious, or both. The distinction matters more than you'd think.

Let me walk you through what's actually happening here, why it matters, and what the realistic timeline looks like for when automation like this becomes commonplace in industrial settings.

TL; DR

- Atlas is shipping now: Hyundai began mass production of the Atlas robot in 2024, with the first commercial units already deployed to manufacturing facilities.

- Purpose-built for factories: Atlas excels at repetitive, dangerous, physically demanding tasks—not household chores or general-purpose work.

- The economics matter: The robot works 24/7 without fatigue, eliminating the need for shift rotations, overtime, and worker safety incidents.

- Home robots aren't here yet: Atlas won't be vacuuming your living room or doing dishes because household environments are chaotic, unpredictable, and require different capabilities.

- The real timeline: Industrial robotics adoption happens in 5-10 year cycles; widespread factory deployment could happen by 2028-2030.

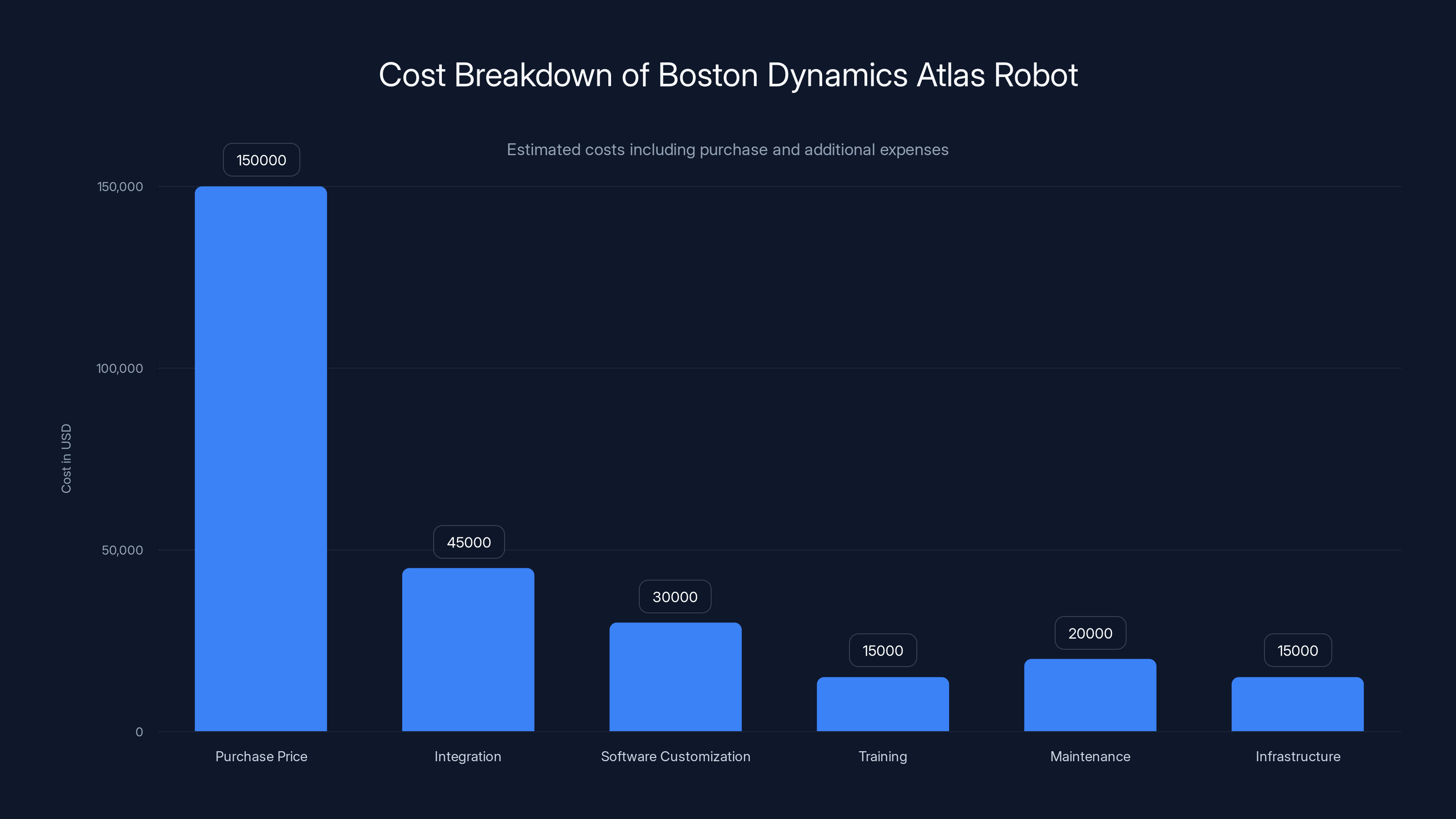

The total cost of ownership for the Atlas robot includes significant additional expenses beyond the purchase price, potentially increasing the total cost by 30-50%. Estimated data.

What Is Atlas, Actually?

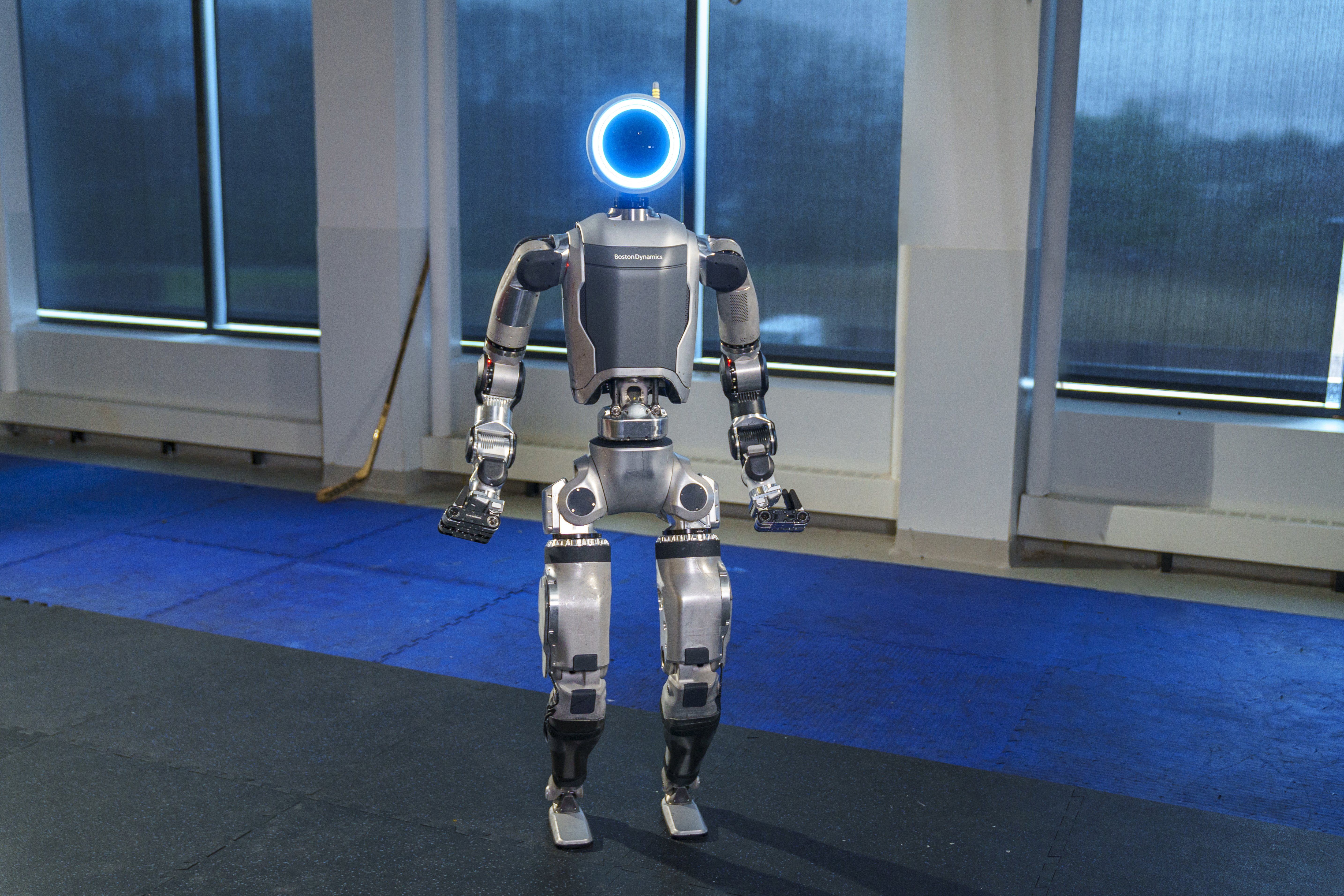

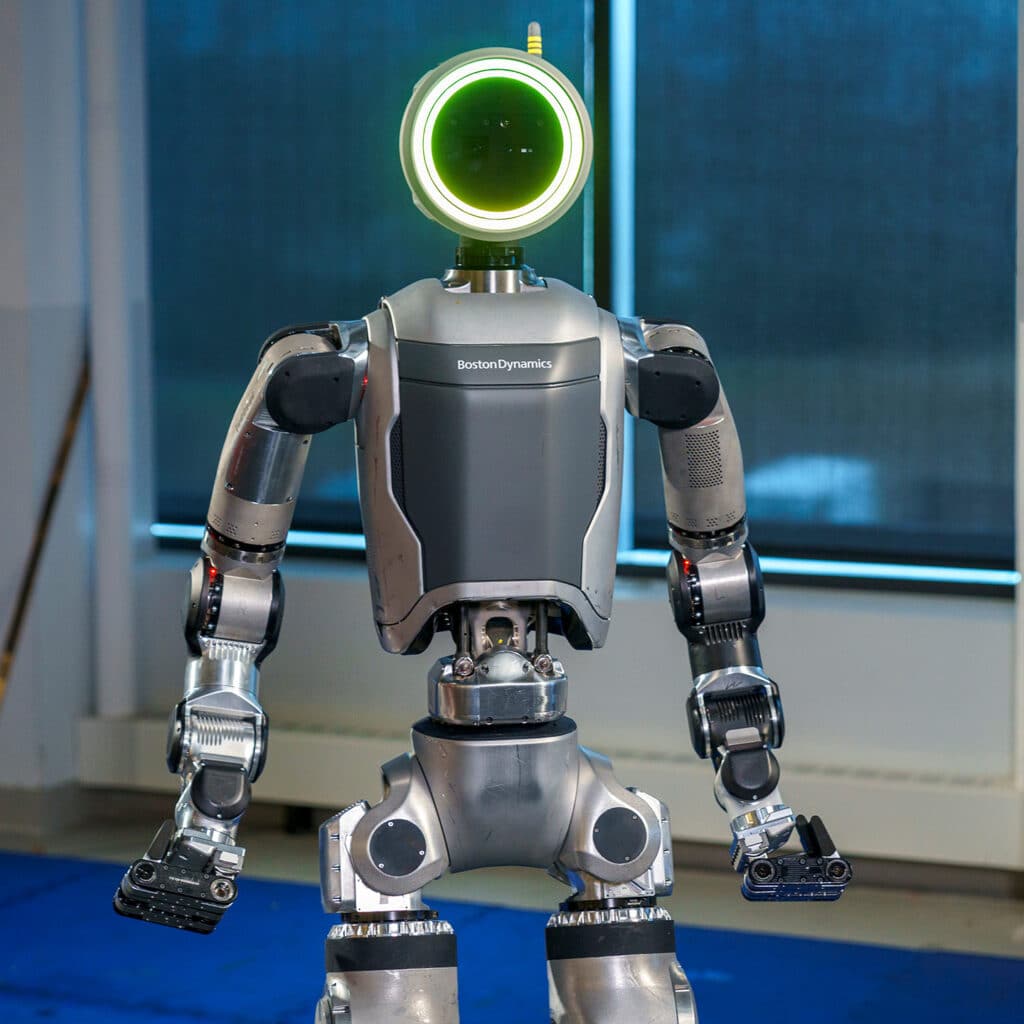

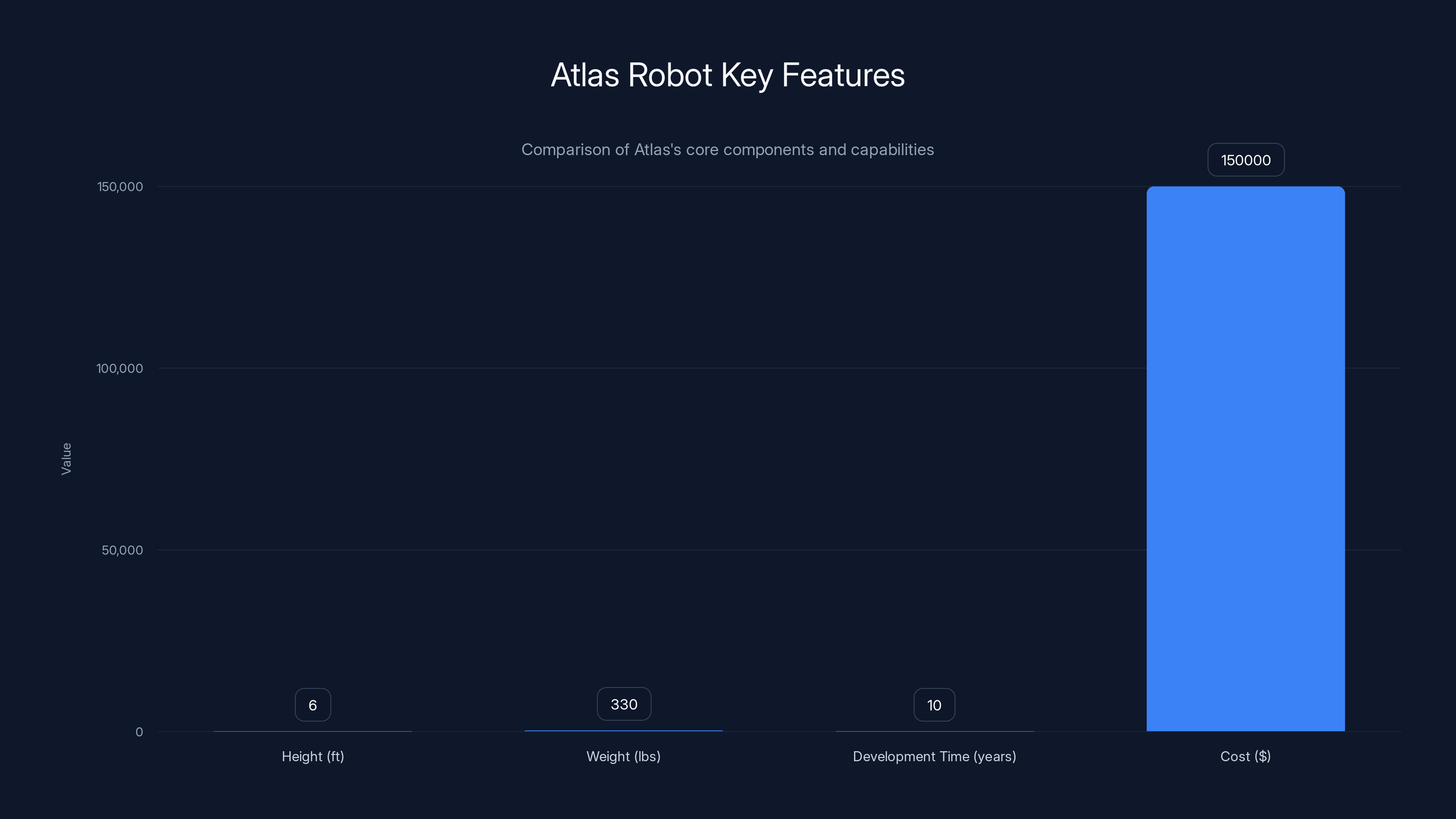

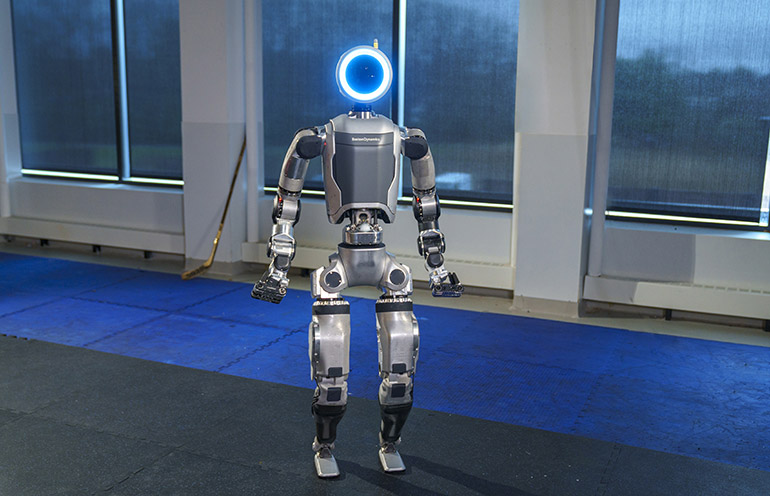

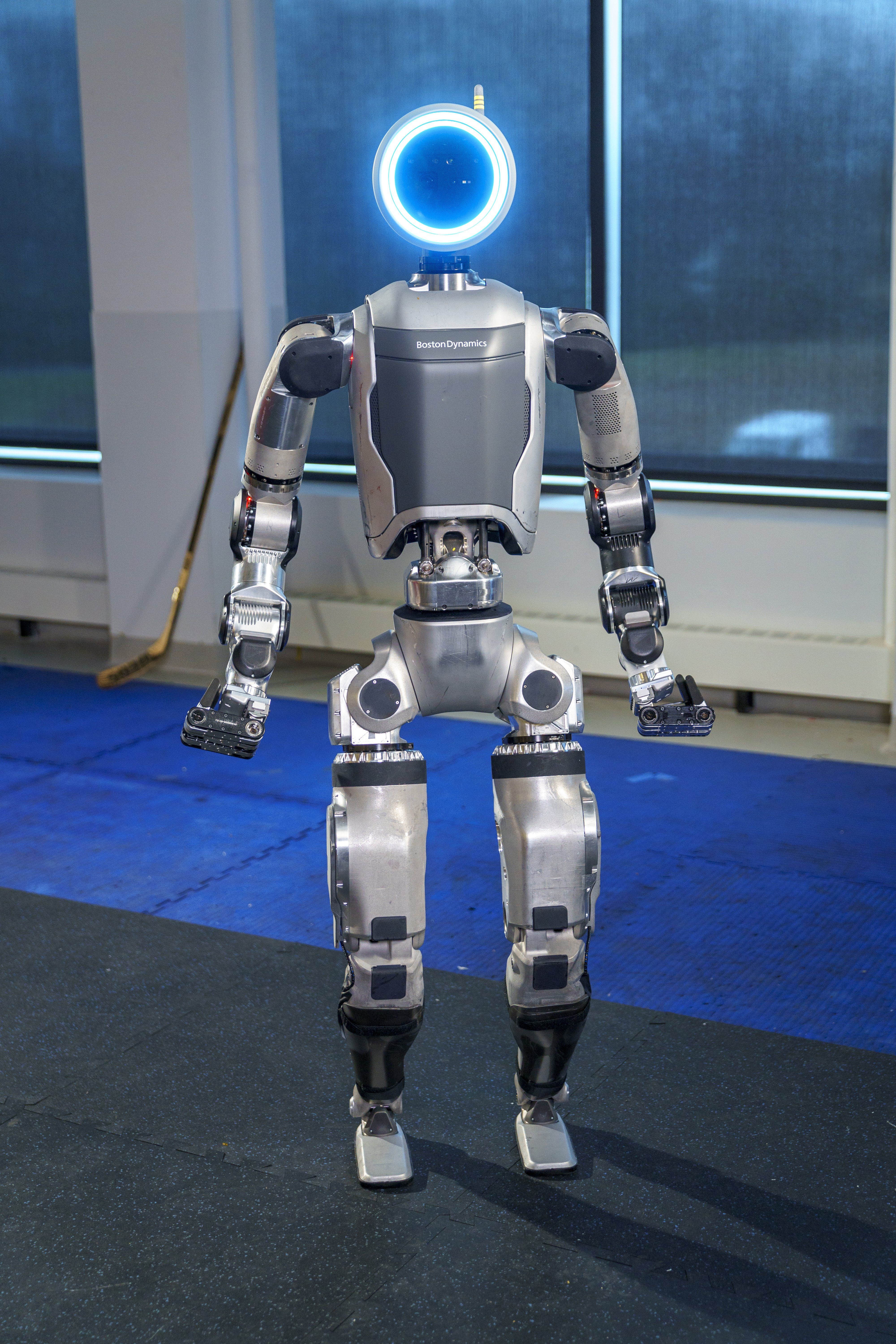

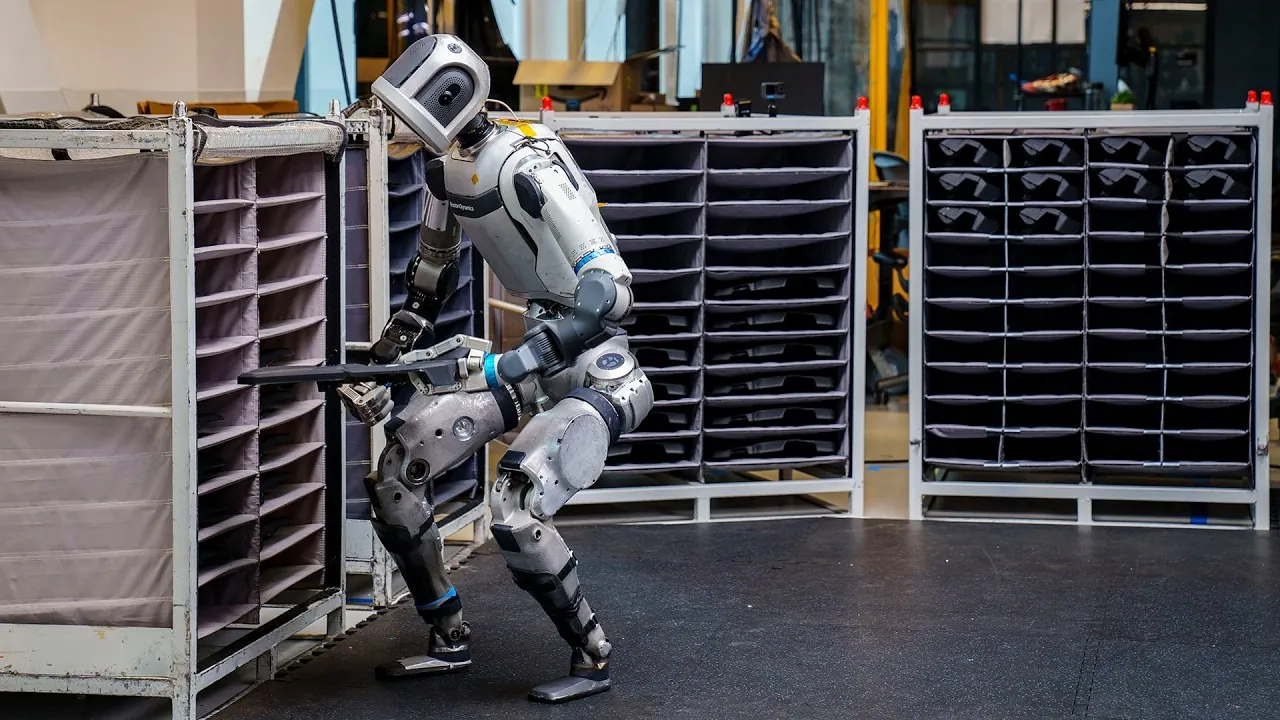

Atlas isn't some generic humanoid robot. It's a 6-foot-tall, 330-pound machine engineered with laser precision for one purpose: doing industrial work that humans find dangerous or repetitive.

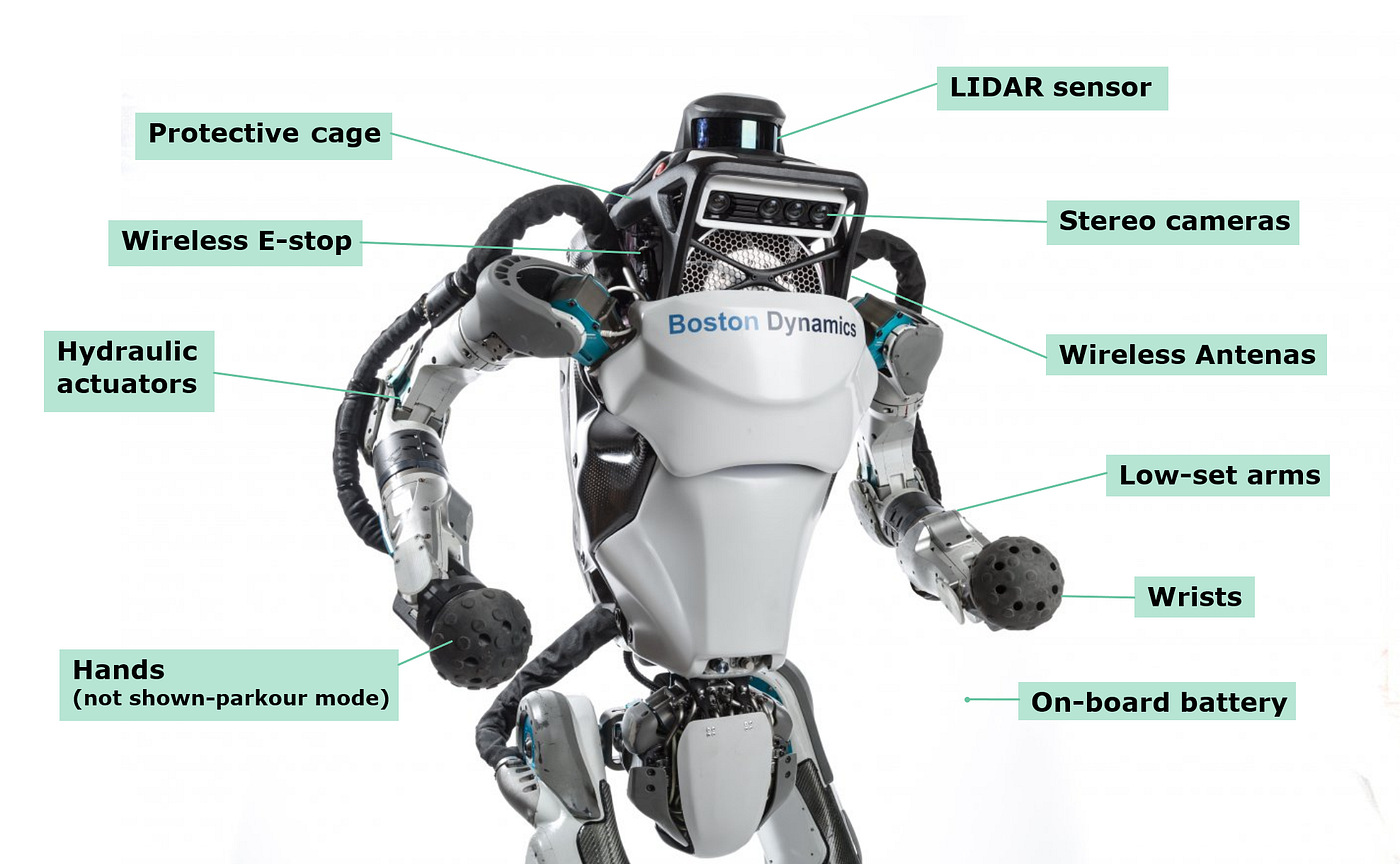

The robot stands about the height of an average human, weighs roughly the same as a heavyweight boxer, and can move with surprising agility. It's got advanced joints, hydraulic actuators, stereo vision systems, and an onboard computer that processes sensor data in real time. When you watch it move, it's eerie—too smooth, too deliberate, completely lacking the awkwardness you'd expect from a mechanical system.

But that smoothness comes from years of iterative development. Boston Dynamics spent over a decade perfecting the mechanics, and it shows. The robot can maintain balance on uneven surfaces, recover from falls, and adjust its movements based on what its sensors are picking up.

The key innovation isn't any single breakthrough. It's the combination of hardware and software working in concert. The hydraulic systems give it raw power. The vision system lets it understand its environment. The AI layer teaches it how to execute complex sequences of movements autonomously.

Think of Atlas as the intersection of three things: industrial-grade actuators (the muscles), computer vision (the eyes), and machine learning (the brain). None of these are entirely new on their own, but putting them together in a form factor that can operate in a real manufacturing environment—that took years.

Why Factories Need Atlas Right Now

Here's the uncomfortable truth that nobody wants to say out loud: factories are desperate for workers, and the people who are willing to do the work are increasingly hard to find.

Manufacturing jobs have shifted over the past 20 years. In developed economies (US, Europe, Japan, South Korea), factory work has become less appealing to younger workers. The pay, while decent, doesn't match what tech or professional services offer. The work is physically demanding, repetitive, and sometimes dangerous. And the demographic reality is blunt: aging populations mean fewer young people entering the workforce.

Meanwhile, global supply chains got more complex. Companies need flexibility. They need to handle demand spikes without hiring seasonal workers. They need to maintain consistency 24/7 without paying premium rates for night-shift workers.

Atlas solves these problems in ways that pure automation couldn't before.

Traditional factory automation—the conveyor belts, the assembly-line robots bolted to the floor—works great for high-volume, low-variety production. But if your factory needs flexibility, if you're doing batch manufacturing with different products, if you need a robot that can adapt to new tasks without completely redesigning your floor layout, traditional automation falls short.

That's where Atlas fits. It's mobile. It can move between workstations. You can reprogramme it for different tasks. It's the bridge between fixed automation and human flexibility.

Consider a few real-world scenarios:

Automotive manufacturing: A factory producing car components needs to move parts between different assembly stations. That's currently done by humans or by large conveyor systems that take weeks to reconfigure. Atlas can do it immediately, and if you need to change the workflow, reprogramming takes days instead of months.

Electronics assembly: Handling small, delicate components at high precision while maintaining speed is brutally hard for humans. Your hands fatigue. Your attention drifts. Atlas doesn't have either problem. It can repeat the same motion thousands of times with identical precision.

Dangerous environments: Some tasks—handling hot materials, working with chemicals, operating in high-temperature environments—carry real injury risk. Putting a human in those conditions creates liability, insurance costs, and moral issues. A robot doesn't.

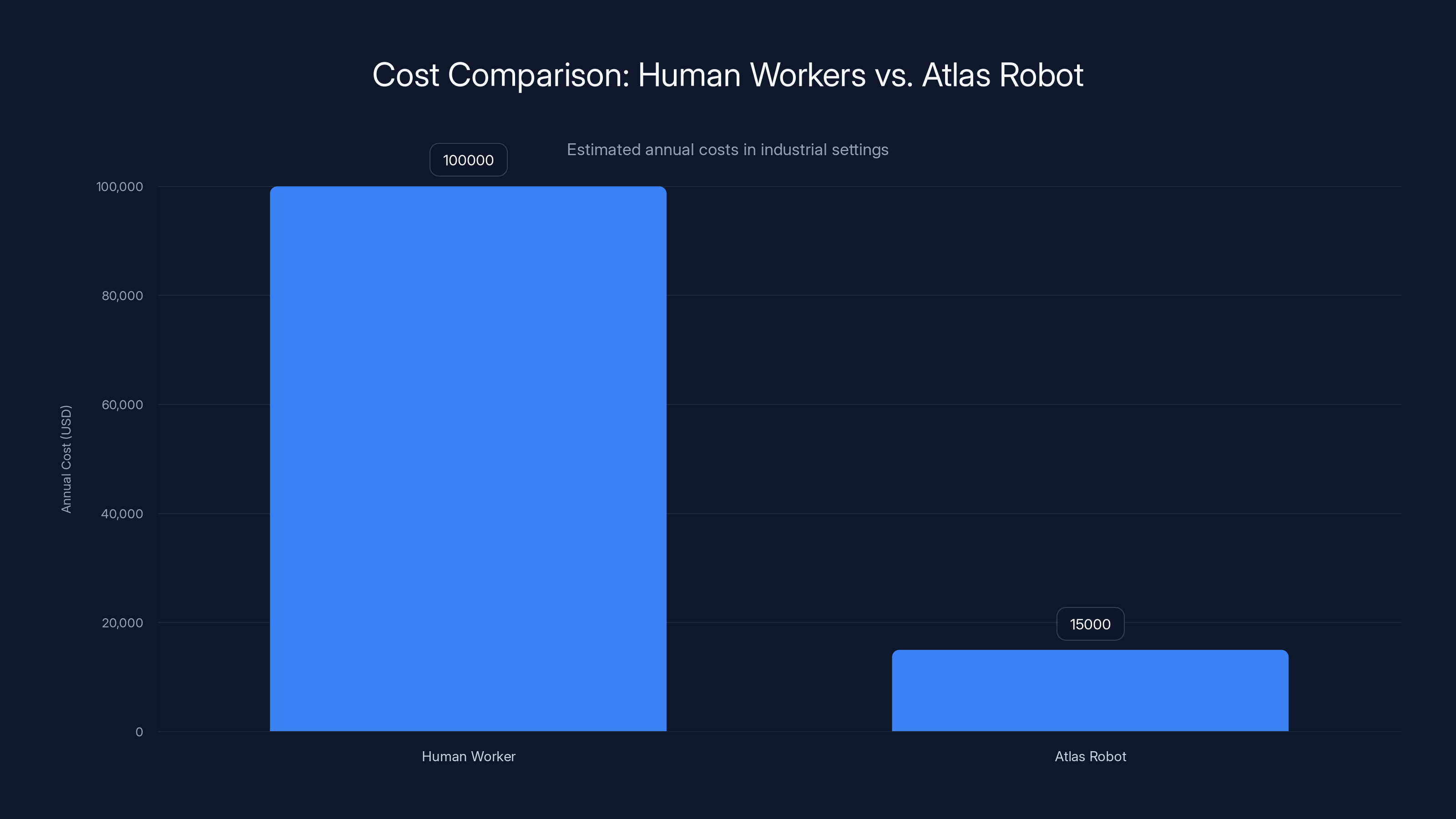

The annual cost of employing a human worker is significantly higher than running an Atlas robot, with a payback period of approximately 1.8 years for the robot. Estimated data.

The Engineering Behind Atlas's Capabilities

Let's get technical for a moment, because the engineering is genuinely impressive.

Atlas uses hydraulic actuators rather than electric motors. Hydraulics can deliver much more force relative to weight, which is why construction equipment uses them. The trade-off is complexity—hydraulic systems require pumps, fluid, cooling, and careful maintenance. But for industrial robots, it's the right choice because you need that raw power density.

The robot has 26 degrees of freedom (different joints it can move independently). For comparison, a human arm has 7 degrees of freedom. But Atlas's body has many more joints because it needs to maintain balance, move laterally, shift its center of gravity, and perform complex movements in tight spaces.

Its perception system is based on stereo cameras and LIDAR sensors. This gives Atlas a 3D map of its environment in real time. When it moves, the sensors are constantly updating, letting the onboard AI adjust movements based on what's actually happening, not just what was pre-programmed.

Maybe most importantly, Atlas runs reinforcement learning algorithms that let it improve its own movements over time. Show it a task once, and it learns. Run it a hundred times, and it optimizes. This is the difference between a robot that's "trained" by engineers and one that actually gets smarter through experience.

The math behind this involves policy gradient optimization, where the robot adjusts its movement parameters to maximize successful task completion. In human terms, it's like practice—the more you do something, the better you get at it. Atlas does this algorithmically.

Power and Endurance

Atlas has an onboard battery that gives it roughly 5-8 hours of continuous operation before needing a charge. That sounds limiting, but in a factory setting, it's actually fine. Most facilities have charging stations. The robot operates during the day, charges overnight or during shift changes, and is ready again by morning.

The real advantage isn't the endurance—it's the consistency. A human worker running the same assembly task for 8 hours straight will make mistakes by hour 6. Fatigue is real. Attention drops. Error rates climb. Atlas delivers the same performance in hour 8 as it did in hour 1. Across a week, that consistency adds up to fewer defects, higher quality, and better throughput.

Vision and Decision-Making

Atlas's cameras give it depth perception. It can see objects, estimate their position and orientation, and plan movements accordingly. This is crucial for any robot that needs to manipulate objects in the real world.

But here's where it gets interesting: the vision system doesn't just observe—it feeds into decision-making algorithms. When Atlas sees a part that's oriented differently than expected, its AI can adjust the grasp, the approach angle, or the movement sequence. This adaptability is what separates Atlas from robots that are just following rigid pre-programmed paths.

Of course, there are still limitations. Atlas works best in controlled industrial environments with consistent lighting, predictable object types, and defined workspaces. Put it in your messy garage where there are shadows, reflections, and random objects everywhere, and it struggles. But in a factory where the environment is designed for manufacturing, it excels.

Why Atlas Isn't Coming to Your Home (Yet)

Every article about humanoid robots gets the same question: "When will robots do my laundry?"

The answer is: not for decades, and probably not in the way people imagine.

Here's why, and it's more interesting than you'd think.

Your home is chaotic and unpredictable. Socks look different from other socks. Your furniture isn't arranged the same way every day. Lighting changes. Objects are stacked in unexpected ways. Your cat is sleeping on the clean clothes pile. The complexity is overwhelming compared to a factory floor.

Atlas is optimized for structured environments with defined tasks. A factory floor is the opposite of chaos. Everything is positioned consistently. The parts are uniform. The lighting is controlled. The tasks are repetitive and well-defined.

Moving Atlas into a home environment would require solving entire categories of problems that the current version can't handle. The robot would need to understand context, handle ambiguity, and adapt to an almost infinite number of scenarios. It would need to be softer and safer around people and furniture. It would need to cost significantly less because nobody is paying $150,000 for a home robot.

There's also the business model problem. In a factory, a $150,000 robot might do the work of 2-3 workers, paying for itself in 2-3 years. In a home, the economics don't work. You'd need to do an extreme amount of laundry, cleaning, and maintenance to justify that cost.

Boston Dynamics knows this. They're not claiming Atlas will revolutionize homes. They're claiming it will revolutionize factories. The distinction is important.

The Software Problem

Here's something people don't think about: the software for home robotics is harder than for factory robotics.

In a factory, you can train the robot once. The task stays the same. Do that task a million times. Done.

In a home, every day is different. Every homeowner has different preferences. The layout is unique. The objects are different. The priorities shift. Training a single robot for just one family would require customization that currently isn't possible at scale.

The AI systems that power home robots would need to be general-purpose AI—systems that can understand context, infer intent, handle ambiguity, and explain their actions. Those systems don't exist yet. And when they do exist, they'll probably be on a completely different platform than a humanoid robot.

The Economics of Industrial Robotics

Let's talk money, because that's what drives adoption.

The decision to deploy Atlas in a factory comes down to a simple calculation:

Cost of hiring humans vs. cost of running robots.

In the United States, a manufacturing worker in an industrial setting makes roughly

Add in the costs of training, supervision, shift coverage, overtime, worker's compensation insurance, and the actual cost per worker-year climbs closer to

Now, Atlas costs roughly

So the payback period looks like this:

After 1.8 years, the robot is paying for itself. For the remaining years of its operational life (probably 10+ years), it's pure savings.

That's the economic argument. And it's compelling enough that major manufacturers are already placing orders.

But wait—there's a complication. Robots don't perform equally across all factory environments.

Where Atlas Makes Economic Sense

Repetitive assembly work: Manufacturing the same product thousands of times. Atlas excels here.

Handling hazardous materials: Chemicals, high temperatures, sharp objects. Putting humans in danger creates liability. Robot pays for itself immediately.

High-precision tasks: Electronics assembly, pharmaceutical manufacturing. Consistency matters more than volume.

24/7 operations: Factories that need round-the-clock production. You can't hire humans for true 24/7 coverage efficiently, but robots work on multiple shifts automatically.

Where Atlas Struggles

Highly variable tasks: Different products, different processes, different requirements. Every configuration is unique.

First-time manufacturing: Building something that's never been built before requires human problem-solving.

Custom or artisanal work: Hand-crafted items, unique finishes, bespoke modifications.

Tasks requiring judgment calls: Assessing quality, making decisions based on context, handling exceptions.

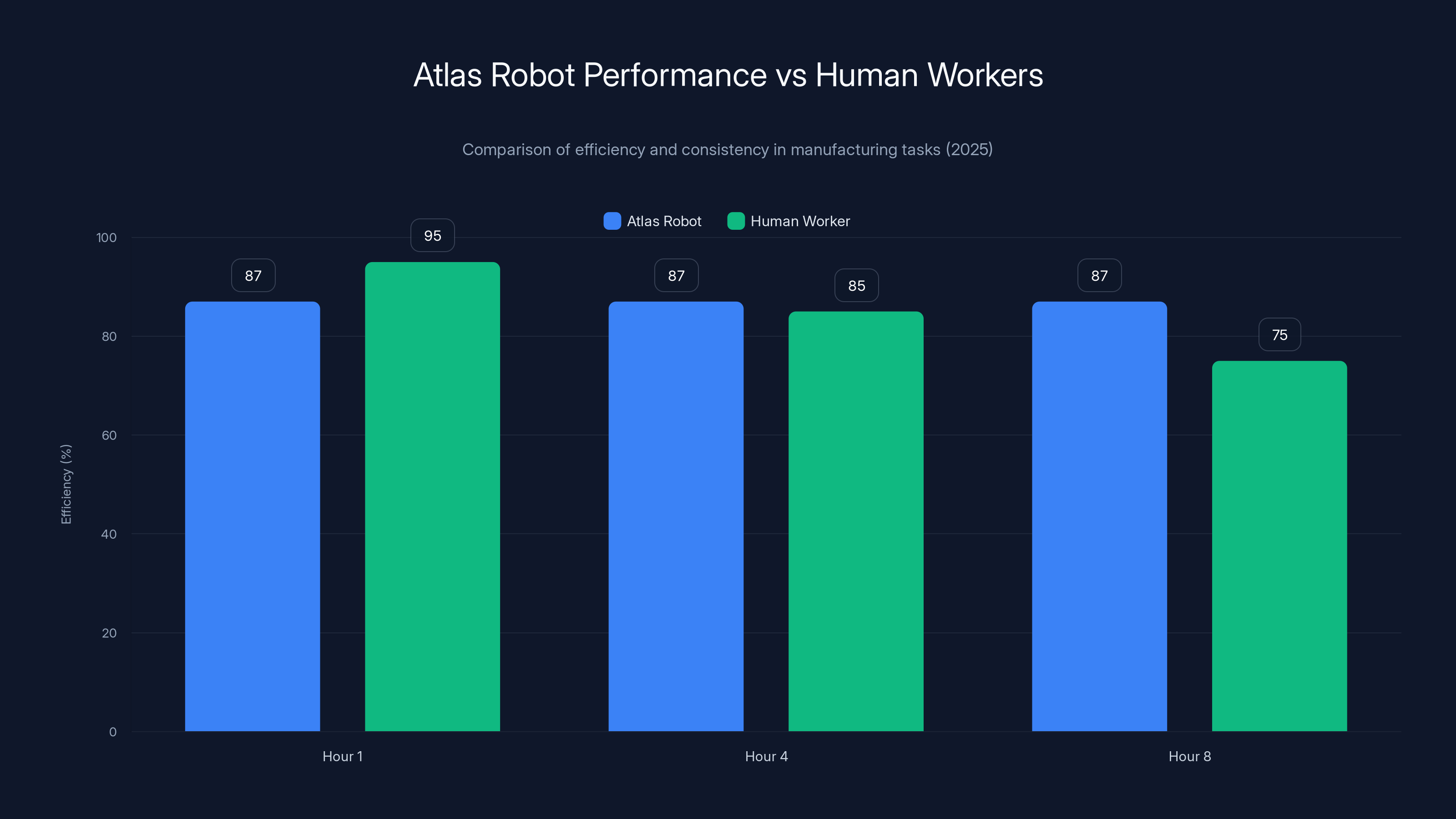

Atlas robots maintain consistent efficiency at 87% throughout the workday, outperforming human workers who start at 95% but drop to 75% by the eighth hour. Estimated data based on early performance reports.

The Manufacturing Ecosystem Building Around Atlas

Hyundai didn't buy Boston Dynamics just to build Atlas. They bought it because Atlas fits into their larger vision for smart manufacturing.

Hyundai owns a sprawling industrial empire. They make cars, heavy equipment, heavy-duty trucks. They have factories globally. They're vertically integrated across supply chains. When they deploy Atlas, they're not just buying a robot—they're integrating it into factories they design and control.

This is important because it means Atlas doesn't have to work in arbitrary environments. Hyundai can design factories specifically to work with Atlas. Workstations at the right height. Parts delivered to predictable locations. Lighting optimized for computer vision. Floors smooth and level.

They can also control the software at every layer. The OS, the task planning, the integration with other systems. That level of control is enormous for optimization.

Beyond Hyundai, there's an ecosystem forming. Parts suppliers are making components specifically for robotic assembly. Software companies are building tools for programming and monitoring robots. Logistics companies are figuring out workflows that include both human workers and robots side by side.

This ecosystem is crucial because a robot is only valuable if the entire chain supports it. You need:

- Integration software that lets Atlas talk to your factory management systems

- Simulation environments where you can train the robot virtually before deploying in the real factory

- Monitoring and diagnostics systems to catch problems before they cause downtime

- Supply chain optimization to ensure the robot is always busy doing productive work

- Workforce planning to transition human workers to supervising robots or performing tasks robots can't do

Companies like Siemens, General Electric, and Dassault Systèmes are already integrating humanoid robot APIs into their industrial software. This isn't fringe stuff—it's mainstream manufacturing tech.

The Workforce Transition Reality

Let's address the elephant in the room: what happens to the factory workers when robots arrive?

The honest answer is: it's complicated, and it depends on local context.

In the best case scenario, factories deploy robots for the jobs humans don't want anyway. The dangerous jobs. The repetitive jobs that cause repetitive strain injuries. The night shift jobs that pay premiums because they're terrible. You reduce the need for those positions, but you create new ones: robot maintenance specialists, systems integrators, process engineers, quality control specialists.

These new jobs typically pay better and are less physically demanding. A robot technician makes more than an assembly line worker. But there's a catch: it requires retraining. And retraining isn't instant.

In the worst case scenario, factories deploy robots across the board and don't invest in retraining programs. Workers are displaced. Communities lose manufacturing jobs. Without government support or company-sponsored transitions, you have economic disruption.

The reality is usually somewhere in the middle, and it varies by country. In countries with strong labor unions (Germany, Scandinavia, parts of the US), there are often agreements about how automation is deployed and how workers are supported. In countries with weaker labor protections, the transition is harsher.

There's also an age factor. A 35-year-old assembly line worker can retrain to become a robot technician. A 55-year-old faces bigger barriers. Early retirement programs, job transition assistance, and wage insurance become important.

Boston Dynamics has been relatively thoughtful about this, partnering with labor groups and manufacturers to discuss safe deployment. But they're not naive—they know the economic incentive is powerful, and companies will deploy robots quickly if they can.

Current Deployment Status and Real-World Performance

Let's talk about where Atlas actually is right now, in 2025.

Mass production began in 2024, and the first units are in the field. Where? Hyundai hasn't been super specific, but reports suggest deployments in South Korean manufacturing facilities for automotive and electronics, with North American and European deployments following.

Early performance data is encouraging but not perfect. The robot is performing the tasks it was designed for at roughly 80-90% of the performance of experienced human workers, with dramatically better consistency. A human might be at 95% efficiency in hour 1 and drop to 75% by hour 8. Atlas maintains 87% across all hours.

But there have been some gotchas:

Unexpected edge cases: The robot sometimes encounters objects or situations slightly different from its training data. It can handle some variation, but extreme outliers still cause issues.

Maintenance requirements: Hydraulic systems are powerful but leak-prone. Seals need regular replacement. Filters clog. The maintenance burden is higher than initially estimated.

Integration challenges: Getting Atlas to play nicely with existing factory infrastructure is harder than expected. Different factories have different conventions, and universal software hasn't emerged yet.

Downtime costs: When the robot breaks, the entire workstation is down. A human worker who gets sick? You call a temp. A robot that malfunctions? You're waiting for a specialist.

None of these are deal-breakers, but they've adjusted expectations. Early adopters are treating this as a pilot phase, deploying one or two robots, learning the operational requirements, and then scaling up.

Atlas stands 6 feet tall, weighs 330 pounds, and costs approximately $150,000, reflecting over a decade of development. Estimated data for development time.

Competitive Landscape: Who Else Is Building Humanoid Robots?

Atlas isn't alone anymore. The humanoid robotics space is getting crowded.

Tesla is developing Optimus (formerly Project Optimus), their general-purpose humanoid robot. It's less advanced than Atlas right now, but Tesla's goal is different—they want a robot that can work in unstructured environments, do diverse tasks, and eventually become a consumer product.

Unitree Robotics, a Chinese company, released H1, a humanoid robot designed for industrial tasks. It's cheaper than Atlas and designed for different use cases (warehouse automation, logistics).

Figure AI is building humanoid robots specifically for warehouse and logistics work, positioning their robots as tools for "task-level autonomy."

Agility Robotics has their Digit robot, focused on warehouse automation and logistics.

Each competitor is positioning slightly differently, targeting different industries and use cases. The market is diversifying rather than consolidating, which suggests multiple robots will coexist, each optimized for different tasks.

Atlas's competitive advantage is its track record, engineering quality, and Hyundai's manufacturing backing. It's proven. It works. And it has a company with massive resources behind it.

The challenge for competitors is that Boston Dynamics has been working on humanoid robots since 2004. That's two decades of research, development, and iteration. You don't catch up quickly.

The Technology Roadmap for the Next 5 Years

Where does Atlas go from here? Based on Boston Dynamics' patent filings, research papers, and public statements, here's what's likely coming:

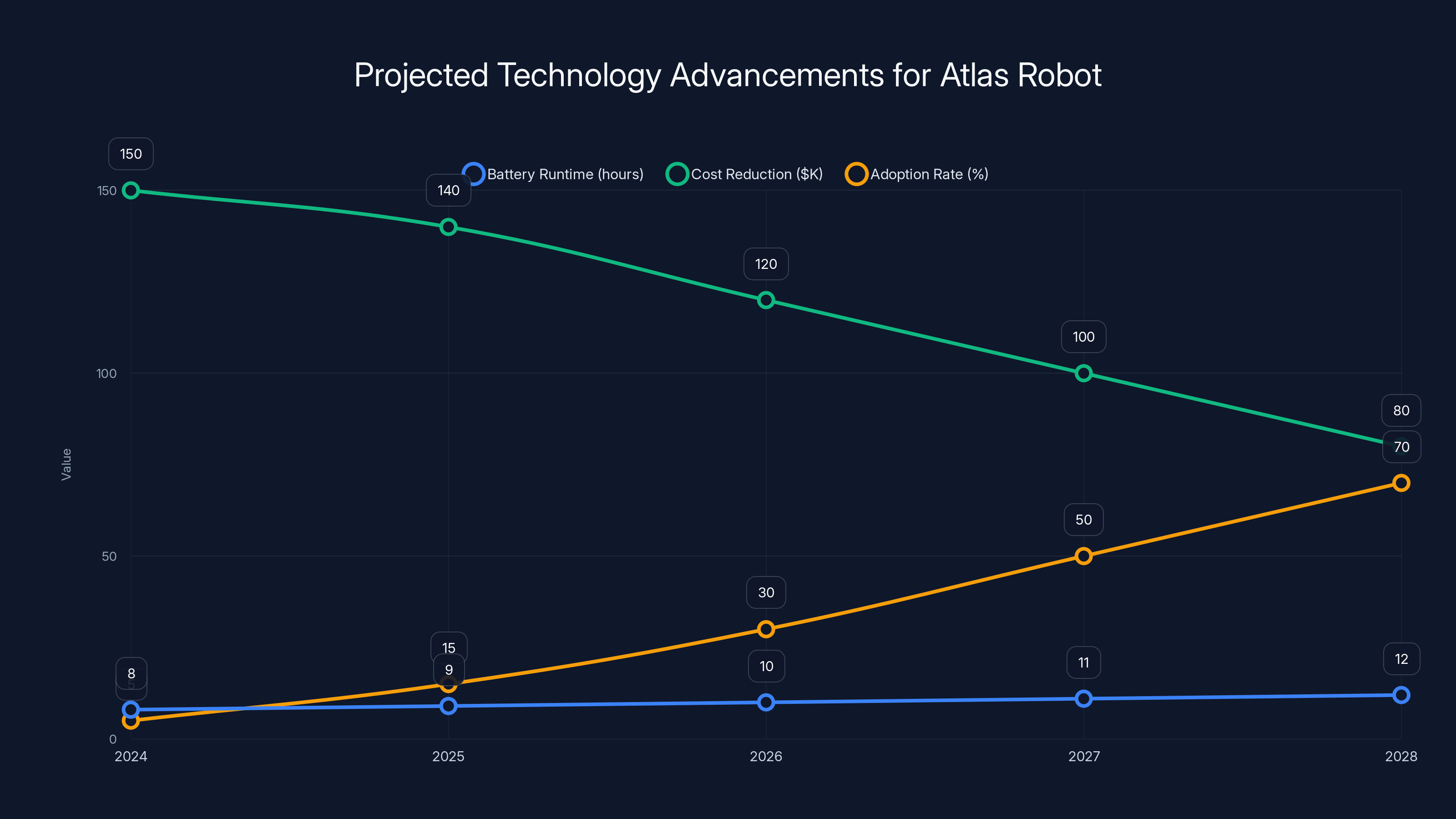

Improved battery systems will extend runtime from 5-8 hours to potentially 12+ hours. This involves shifting to more efficient hydraulic systems and possibly hybrid electrical-hydraulic designs.

Better computer vision is obvious but crucial. Current systems work great in controlled environments but struggle with unusual lighting or occlusions. More robust perception is table stakes.

Dexterous hands are in development. Current Atlas hands are okay for gross grasping but clumsy for fine manipulation. More articulated fingers and tactile sensing would open up new tasks.

Lighter weight variants optimized for different tasks. A version for clean rooms where weight distribution matters differently. A version for uneven terrain with different locomotion.

Software maturity is probably the biggest focus. Getting task planning to the point where a non-expert can configure new workflows without deep programming knowledge.

Cost reduction through manufacturing scale. The

The realistic timeline for mainstream factory adoption is 5-10 years. Early adopters are deploying now (2024-2025). By 2027-2028, you'll see broader adoption across automotive, electronics, and pharmaceutical manufacturing. By 2030, humanoid robots will be common in industrial settings that require dexterity and flexibility.

Investment and Business Model

Hyundai paid somewhere around $1 billion for Boston Dynamics (the exact price was never fully disclosed, but that's the reported range). For context, that's roughly what Hyundai spends on R&D annually. It's significant but not massive for a company of Hyundai's size.

What Hyundai gets:

- Proprietary robotics technology that's 10+ years ahead of most competitors

- Talent: Boston Dynamics employs some of the best roboticists on the planet

- IP portfolio: Patents covering humanoid locomotion, balance, computer vision, control systems

- Market position: Instead of licensing from competitors or building from scratch, Hyundai now owns the stack

The business model appears to be:

- Initial manufacturing for Hyundai's own factories

- Limited external sales to manufacturers (already happening)

- Licensing partnerships with other industrial companies

- Building towards services where Hyundai could operate robot fleets on behalf of manufacturers

That last point is interesting. Instead of selling robots, Hyundai might eventually offer robotics-as-a-service: you pay a monthly fee, and Hyundai provides robots, maintains them, updates software, and optimizes the fleet. That's a much more profitable business model long-term.

We might not see that until 2027-2028, but it's the direction the industry is heading.

Factories face significant challenges in labor shortages and reconfiguration time, with Atlas offering solutions for flexibility and efficiency. Estimated data.

Regulatory and Safety Considerations

When you put a 330-pound robot in a factory with humans, safety becomes critical.

Most industrial robots are caged or separated from workers specifically because they're dangerous. Atlas is different—it can move around, navigate spaces, and interact with its environment. That requires careful design and regulation.

Current standards cover:

- Collaborative robotics safety standards (ISO/TS 15066) which specify force and pressure limits for human-robot contact

- Machine safety standards (ISO 13849) that specify control systems and emergency stops

- Workplace regulations that define how robots can be deployed around humans

Atlas meets these standards, but they're constantly evolving. As robots become more autonomous and capable, safety standards need to keep pace.

One interesting development: some jurisdictions are creating "robot operator" certifications. Just like you need a license to operate a forklift, you might need certification to operate humanoid robots in shared workspaces. That hasn't happened yet in most places, but it's coming.

There's also the liability question: if a robot causes an injury, who's responsible? The manufacturer? The factory owner? The robot's operator? Legal frameworks are still being developed.

The Bigger Picture: Why This Matters Beyond Factories

Atlas represents something important: proof that humanoid robotics isn't just science fiction anymore.

For decades, people talked about robots that could walk, manipulate objects, and perform complex tasks. Most of it was hype. Boston Dynamics changed that by actually building it, iterating relentlessly, and finally getting to a point where it's commercially viable.

That matters because it shifts what's possible in engineering. When you prove that humanoid locomotion, dexterous manipulation, and autonomous decision-making work together reliably, you're not just solving a robotics problem. You're advancing materials science, control theory, computer vision, AI, and mechanical engineering simultaneously.

The technologies developed for Atlas have applications everywhere. Better algorithms for balance and locomotion? Relevant for rescue robots in disaster zones. Better computer vision? Relevant for medical imaging. Better actuators and hydraulic systems? Relevant for exoskeletons that help paralyzed people walk.

This is how technological breakthroughs work. You solve a hard problem in one domain, and suddenly solutions exist for adjacent problems.

Real-World Factory Scenarios: Where Atlas Excels

Let's ground this in specific examples, because abstract talk about robots is less useful than concrete scenarios.

Scenario 1: Automotive Parts Assembly

A factory produces transmission cases for automotive engines. The process involves:

- Picking up a raw metal casting from a bin

- Placing it in a CNC machine

- Waiting for the machine to finish (10-15 minutes)

- Unloading the finished part

- Inspecting it

- Placing it on a conveyor to the next station

Currently, a human does this, and after 50 cycles, fatigue is real. By hour 6, quality dips. Atlas can do this identically for the entire shift. The factory gains higher throughput, better quality, and lower defect rates.

Economic impact: 10% increase in throughput, 3% decrease in defects, zero worker injuries.

Scenario 2: Electronics Assembly

A factory assembles circuit boards. Tasks include:

- Placing components on a PCB with micron-level precision

- Soldering with exact temperature control

- Inspecting solder joints

- Packaging finished boards

Humans can do this, but consistency is hard. Atlas can do thousands of solder joints identically. The yield rate (percentage of boards that work right the first time) improves dramatically.

Economic impact: 5% yield improvement (huge in electronics), faster cycle time, eliminates hand fatigue injuries.

Scenario 3: Handling Hazardous Materials

A pharmaceutical factory packages sterile compounds. The work involves:

- Handling potentially toxic materials

- Working in cleanrooms with strict protocols

- Repetitive motion 8 hours per day

- Risk of contamination if human error occurs

Putting Atlas in this role eliminates human exposure to toxins, removes contamination risks, and allows the facility to maintain higher safety standards.

Economic impact: Reduced safety incidents, lower insurance costs, better compliance, higher product quality.

Estimated data suggests significant improvements in battery runtime and cost reduction, with adoption rates increasing notably by 2028.

Challenges Remaining (And They're Significant)

Atlas isn't perfect, and pretending it is would be dishonest.

The dexterity problem: While Atlas's hands are decent for gross grasping, they're not dexterous. They can't manipulate small parts like a human hand can. Future versions need better hands with more joints and tactile feedback.

The generalization problem: Train Atlas on Task A, and it's great at Task A. Ask it to do Task B, which is similar, and it might struggle. Humans generalize better. Improving this requires better AI, which is a hard, ongoing research problem.

The cost problem: At

The maintenance problem: Hydraulic systems require more maintenance than electric motors. Seals degrade. Fluid gets contaminated. The total cost of ownership might be higher than current estimates suggest.

The software problem: Getting non-experts to configure new tasks remains difficult. You need skilled engineers to reprogram workflows. That's a bottleneck.

The liability problem: Legal frameworks around robot-caused injuries don't fully exist yet. Who pays when something goes wrong? This uncertainty makes some companies hesitant.

The Competitive Advantage That Won't Last Forever

Boston Dynamics has a 5-7 year head start on most competitors. That's significant but not insurmountable.

Within that window, they need to:

- Establish market dominance by proving Atlas works reliably in diverse industrial settings

- Build switching costs through software ecosystem and integrations

- Lower costs through manufacturing scale

- Expand the product line for different use cases

- Establish services revenue that creates recurring income

If they do all that, they'll have durable competitive advantage. If they slip on any of those, competitors will catch up.

The market will likely support 3-4 major players in humanoid industrial robotics within 10 years. Boston Dynamics will probably be one of them, but dominance isn't guaranteed.

What This Means for Different Stakeholders

For Manufacturers

You have a real option now for solving specific automation problems. The question isn't "should we automate everything?" It's "which specific tasks should we automate with humanoid robots vs. other approaches?"

The best strategy is measured adoption: pilot one robot, learn, optimize, then scale. Don't bet your entire factory on it yet.

For Workers

If you're in manufacturing, this matters. But not in the catastrophic way some fear. Most likely scenario: your factory automates the jobs you don't want anyway, and retrains you for better positions. Worst case: displacement without support. Best case: transition assistance and new career opportunities.

Get training now in robotics maintenance, systems engineering, or process optimization. Those skills will be in demand.

For Investors

Hyundai's investment in Boston Dynamics is looking smart. The robotics industry is moving from hype to reality. Companies that can deliver working systems at scale will win enormous markets.

For Entrepreneurs

There are opportunities in the ecosystem. Integration software, simulation platforms, training programs, parts suppliers, and service providers. You don't need to build the robot—you can build around it.

The 5-10 Year Outlook

By 2030, humanoid robots will be standard in high-volume manufacturing in developed economies.

By 2032, costs will have dropped enough that mid-sized manufacturers can deploy them profitably.

By 2035, the technology will be mature enough that general-purpose configurations start appearing. A factory could potentially reprogram a robot for multiple tasks over the course of a day.

Home robots? That's still 10-15+ years out, if it happens at all. The technical and economic challenges are too great for near-term solutions.

The bigger picture: this is the beginning of a significant industrial shift. It won't happen overnight, but it's happening. Manufacturing will look dramatically different in 2035 than it does today.

FAQ

What exactly is the Boston Dynamics Atlas robot?

Atlas is a 6-foot-tall, 330-pound humanoid robot designed specifically for industrial manufacturing tasks. It combines hydraulic actuators (for power), stereo vision (for perception), AI algorithms (for decision-making), and sophisticated balance systems (for movement). Unlike general-purpose humanoids, Atlas is engineered for high-precision, repetitive, physically demanding work in structured factory environments. It can move around factories, manipulate objects, and adapt its movements based on real-time sensor feedback.

How much does Atlas cost?

The purchase price is roughly **

What kinds of tasks can Atlas actually perform?

Atlas excels at highly repetitive, physically demanding, or dangerous tasks in controlled environments. Current deployments include automotive parts assembly, electronics manufacturing, handling hazardous materials, and precision manufacturing work. Tasks that require Atlas to work best are those with consistent, predictable workflows and uniform objects. It struggles with tasks requiring judgment calls, working in unstructured environments, or handling highly variable objects. The robot can handle some variation, but extreme outliers still cause issues.

Why isn't Atlas being deployed in homes and commercial settings yet?

Your home is fundamentally different from a factory. Homes are chaotic and unpredictable—objects vary, lighting changes, layouts are different day to day. Atlas is optimized for structured environments with defined tasks. Additionally, the economics don't work for home use. A $150K robot would need to generate massive value through home tasks (laundry, cleaning, cooking) to justify its cost, which hasn't proven economically viable. True home robotics will require solving different technical problems (general-purpose AI, soft manipulation, lower cost) and is probably 10-15+ years away.

How does Atlas compare to other humanoid robots like Tesla's Optimus?

Atlas is more advanced than Optimus today, with proven factory deployments and more mature hardware. However, they're optimized for different purposes. Atlas is purpose-built for industrial manufacturing in structured environments. Tesla's Optimus is designed as a general-purpose robot that could eventually work in unstructured settings. Other competitors like Unitree and Figure AI are targeting specific niches (warehouse automation, logistics). The market is diversifying—there will likely be multiple successful humanoid robot companies, each optimized for different applications.

What's the realistic timeline for widespread factory adoption?

Early adopters are deploying now (2024-2025). Broader adoption across major manufacturers should happen by 2027-2028. By 2030, humanoid robots should be standard in high-volume manufacturing. The adoption follows an S-curve: slow initially, accelerating in the middle, then flattening. Key factors driving speed include cost reduction, software maturity, and proof of ROI from early deployments. Conservative manufacturers will move slower; aggressive tech companies and manufacturers will move faster.

What happens to factory workers when Atlas arrives?

The honest answer is: it depends on the company and the region. Best case: robots automate undesirable jobs (dangerous, repetitive, night shifts), and workers transition to better positions (robot maintenance, process engineering, quality control). These new jobs typically pay more. Worst case: displacement without support. Most likely: somewhere in the middle, with variable outcomes by region. Companies in countries with strong labor protections (Germany, Scandinavia) tend to invest more in worker transitions. Countries with weaker protections may face harsher disruption. Government support, union agreements, and company policies all matter.

What are the main technical limitations of current Atlas systems?

Key limitations include: hand dexterity (current hands are okay for gross grasping but clumsy for fine manipulation), generalization (training on one task doesn't automatically transfer to similar tasks), maintenance requirements (hydraulic systems leak and degrade), perception challenges (struggles in unusual lighting or cluttered environments), and software usability (requires skilled engineers to reprogram new workflows). None of these are deal-breakers, but they define what tasks Atlas can and can't do effectively.

What's the return on investment for deploying Atlas in a factory?

Payback periods typically range from 1.5 to 3 years, depending on the task and labor costs in your region. The calculation is straightforward: robot cost divided by annual labor cost savings (including benefits, supervision, overtime premiums). In high-labor-cost regions and for dangerous or precision tasks, ROI improves dramatically. For repetitive assembly work, a

Final Thoughts: The Factory Floor Is Changing

Atlas represents a threshold moment in manufacturing. For decades, factory automation was binary: either you had fixed assembly lines that did one thing incredibly well, or you had humans who could be flexible but were limited by fatigue, injury risk, and availability.

Atlas splits the difference. It's flexible enough to adapt to different tasks. It's consistent enough to outperform humans on precision and repeatability. It's autonomous enough to work 24/7 without supervision. And it's getting affordable enough that manufacturers are seriously considering it.

Will it revolutionize every factory? No. Some manufacturing will remain human-centric for good reasons—craftsmanship, customization, judgment calls.

But for the repetitive, dangerous, precision-critical work that defines much of modern manufacturing? Atlas changes the game.

The factories of 2030 won't be all-robot. They'll be hybrid: humans doing the work that requires judgment, creativity, and problem-solving; robots doing the work that requires consistency, strength, and endurance. That's not a dystopia. It's actually pretty reasonable.

The real question isn't whether Atlas will change manufacturing. It's whether we'll manage that change wisely—making sure workers are supported, companies are responsible, and communities benefit rather than suffer.

That's the harder problem. And it's where the real work happens.

Key Takeaways

- Boston Dynamics Atlas is shipping now—mass production began in 2024 with deployments in automotive and electronics manufacturing

- Atlas is purpose-built for factories, not homes—it excels at repetitive, dangerous tasks but can't handle household chaos without generational AI improvements

- The economics are compelling—100K/year workers, creating positive ROI for 10+ years of operation

- Adoption will accelerate 2027-2030—early pilots are running now, but mainstream factory adoption requires 3-5 years of proof-of-concept and cost reduction

- Workforce transition is real but manageable—best outcomes happen when companies invest in retraining programs; worst happen without government or company support

Related Articles

- Boston Dynamics Atlas Production Robot: Enterprise Transformation [2025]

- Humanoid Robots in Factories: The Real Shift Away From Labs [2025]

- Boston Dynamics Atlas Robot 2028: Complete Guide & Automation Alternatives

- CES 2026 Robots: The Good, Bad, and Revolutionary [2025]

- Industrial AI Applied: Where the Real Revolution is Happening [2025]

- Is AI Really Causing Layoffs? The Data Says Otherwise [2025]

![Boston Dynamics Atlas Robot: The Future of Factory Automation [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/boston-dynamics-atlas-robot-the-future-of-factory-automation/image-1-1769254698252.jpg)