Microsoft's Deleted Blog: The AI Piracy Scandal Explained [2025]

In November 2024, Microsoft published a blog post that seemed innocuous at first glance. Senior product manager Pooja Kamath wanted to showcase a cool new feature for Azure SQL Database—something about making it easier to add AI capabilities to applications using Lang Chain and large language models.

The example was relatable. Engaging. Perfect for marketing purposes.

There was just one problem: the entire example relied on pirated Harry Potter books.

Microsoft's blog post didn't technically tell people to pirate copyrighted works. But it did link to a publicly available dataset containing all seven Harry Potter novels, which the platform hosting the data claimed was in the public domain. It wasn't. It was never in the public domain. The books are still protected by copyright, and J. K. Rowling's lawyers maintain a notoriously aggressive stance on intellectual property.

When the mistake surfaced on Hacker News in early 2025, the internet noticed immediately. The backlash was swift. Microsoft, facing mounting criticism, deleted the blog post without explanation. The dataset was taken down shortly after.

But here's where it gets interesting: this wasn't just a careless mistake by one product manager. This incident exposes something much deeper about how tech companies approach AI development, what they're willing to overlook, and the increasingly blurry line between innovation and infringement.

This article breaks down everything that happened, why it matters for AI ethics and copyright law, and what it signals about the future of generative AI training practices.

TL; DR

- Microsoft's forgotten tutorial: A November 2024 blog post showed developers how to train AI models using all seven Harry Potter books from a mislabeled public dataset

- The piracy problem: The books aren't in the public domain, but were marked as such on Kaggle, and Microsoft linked directly to the infringing content

- The fallout: After Hacker News discussion, Microsoft deleted the post and the dataset was removed, but the incident reveals systemic problems in how AI companies handle copyright

- Legal gray area: Microsoft may claim ignorance, but using copyrighted works to train AI without permission is facing lawsuits from authors and publishers worldwide

- Broader implications: This incident shows how easy it is for AI training to depend on pirated content, and how current enforcement mechanisms are reactive rather than preventive

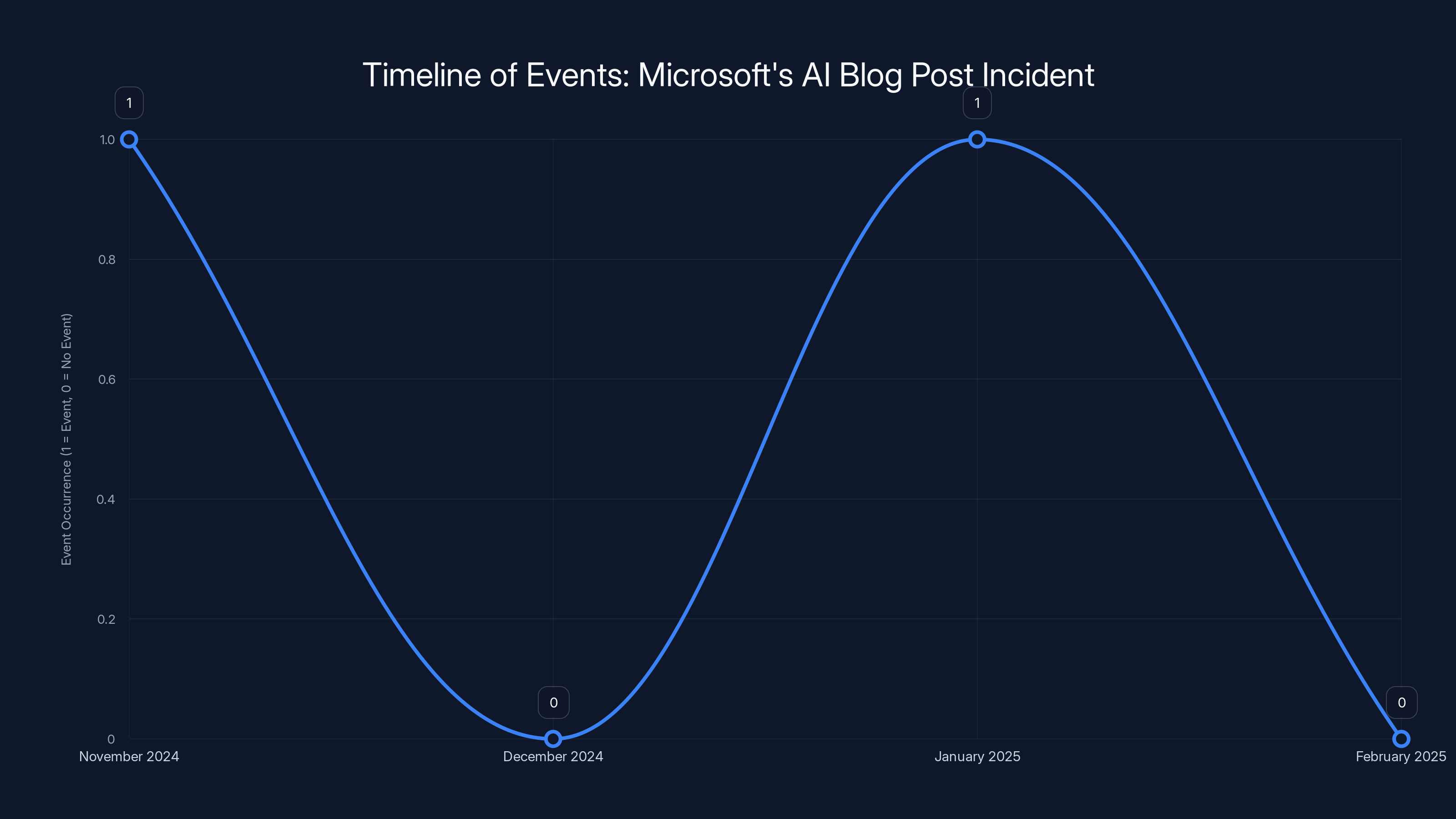

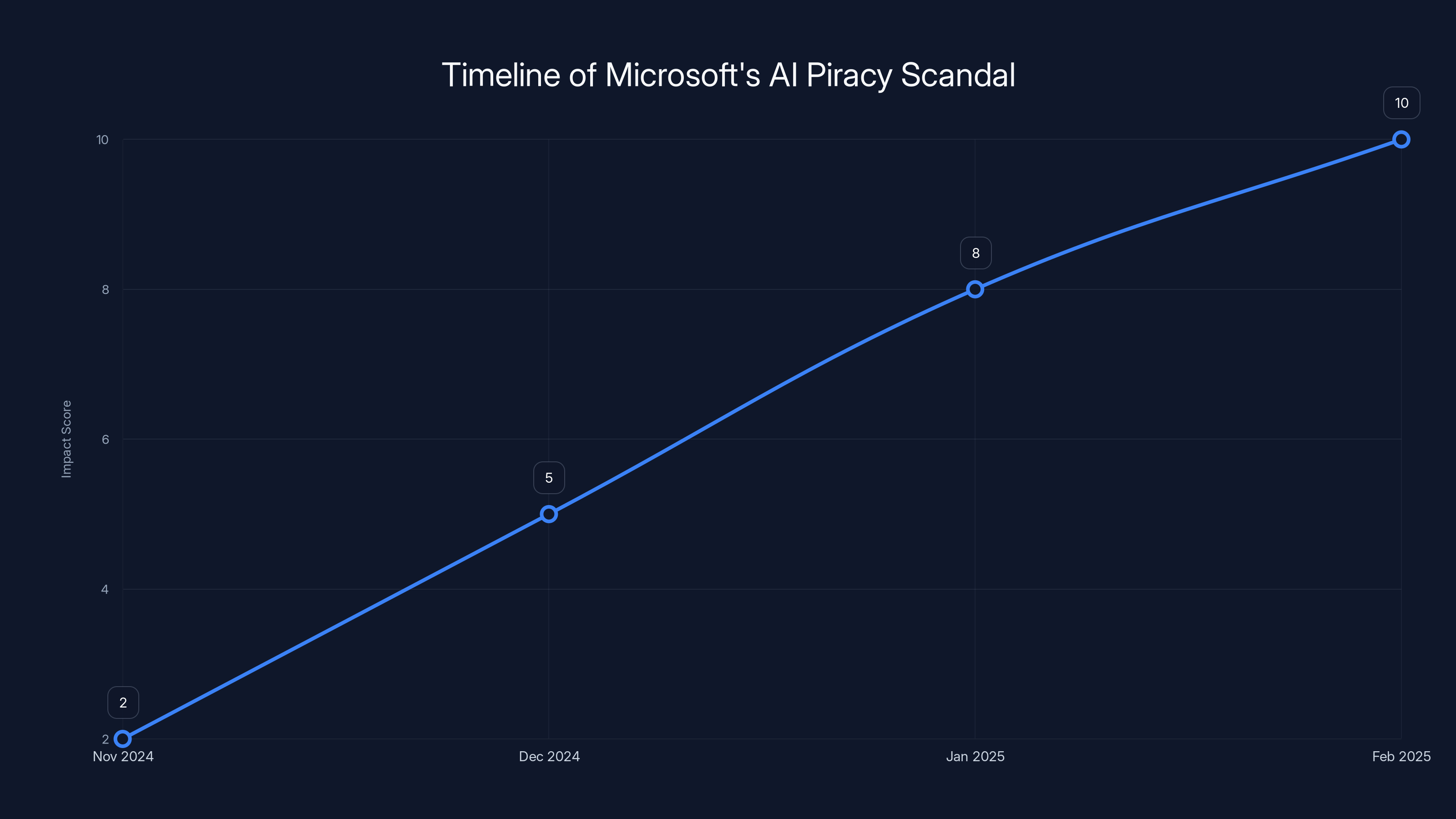

The timeline highlights the key events from the publication of the blog post in November 2024 to subsequent developments. Estimated data used for timeline projection.

What Actually Happened: The Timeline

Let's start with the facts, because there's a lot of confusion about what Microsoft actually did and didn't do.

In November 2024, Kamath published a blog post on Microsoft's Azure website. The title promised something useful for developers: a guide to adding generative AI features to applications "with just a few lines of code." The technical approach was legitimate. Using Azure SQL DB, Lang Chain, and LLMs to build AI-powered features is a real, valuable capability.

The problem was the example dataset she chose to demonstrate this capability.

Kamath selected Harry Potter as the training data. Not as an original example. Not as a hypothetical. She linked directly to a Kaggle dataset containing all seven books and then trained AI models using that data. She even had the models generate Harry Potter fan fiction incorporating Microsoft's new Native Vector Support feature. There was an AI-generated image of Harry Potter with a friend learning about Microsoft technology.

This wasn't subtle. Microsoft wasn't burying the use of Harry Potter in a footnote. The entire blog post centered on showing how easy it was to take a well-known literary dataset and build interactive AI applications with it.

The Kaggle dataset in question had been online for years. It claimed to be public domain. That label was incorrect. The dataset uploader, Shubham Maindola, later told media outlets that the public domain designation was "a mistake." He said there was "no intention to misrepresent the licensing status."

That's the charitable interpretation. But if you're uploading copyrighted novels to a public platform, good intentions don't change the legal reality.

The dataset had roughly 10,000 downloads over its lifetime. That's not insignificant, but it's also low enough that it apparently flew under the radar of Rowling's notoriously protective legal team. No takedown notice. No DMCA complaint. The infringing content just sat there, waiting to be discovered.

Then Microsoft amplified it. By linking to it in an official blog post published on Azure's documentation site, Microsoft introduced the dataset to a new audience: developers actively looking to learn about AI training. The reach expanded dramatically. Suddenly, thousands of Microsoft's customers had a direct path to training models on copyrighted Harry Potter content.

On Thursday after Ars Technica reached out to verify the licensing status, Maindola removed the dataset. Microsoft, facing the prospect of a public relations disaster, deleted the blog post. No explanation. No apology. Just gone.

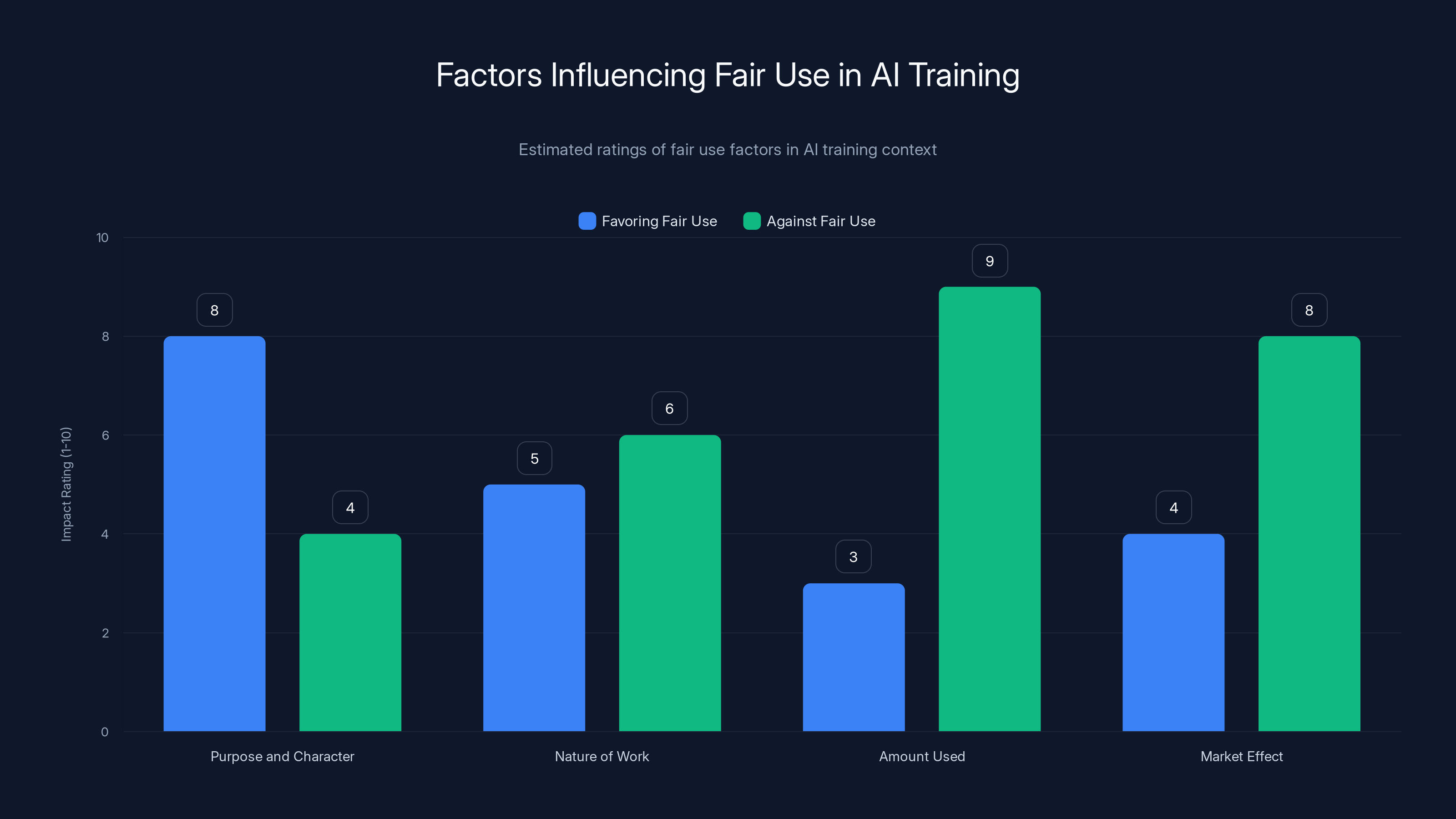

Estimated data suggests 'Purpose and Character' and 'Market Effect' are critical in determining fair use in AI training, with significant arguments on both sides.

The Technical Example: Clever But Problematic

Before diving into the copyright implications, it's worth understanding what Kamath actually built in the blog post. Because from a technical standpoint, the example was genuinely interesting.

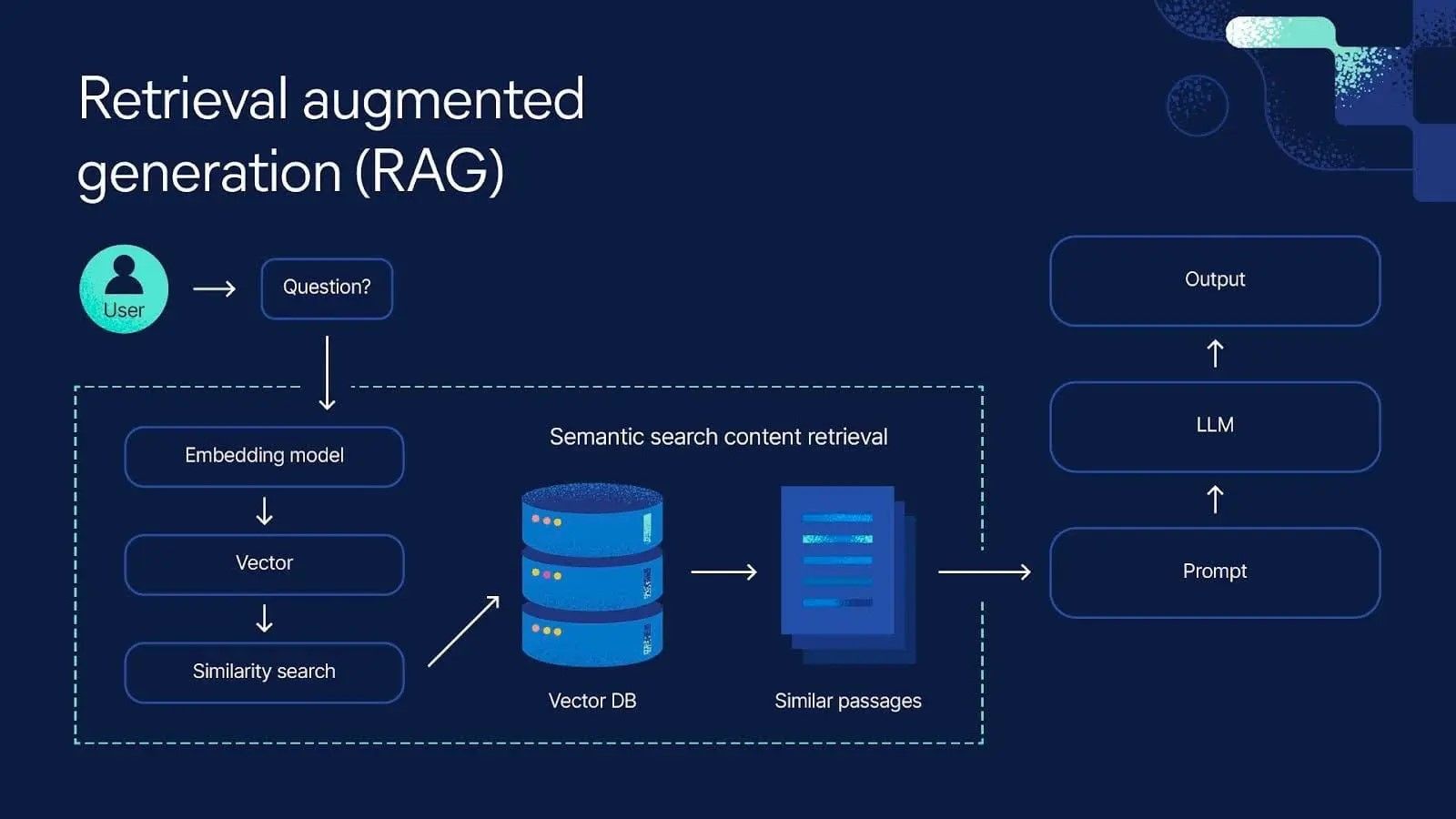

The concept used RAG, or Retrieval-Augmented Generation. This is a real technique used in production AI systems. Instead of training the LLM from scratch on Harry Potter, Kamath stored the book excerpts in Azure SQL Database with vector embeddings. When a user asked a question, the system would retrieve the most contextually similar passages from the database and feed them to the LLM as context.

It's an elegant approach. It keeps the LLM grounded in specific source material. It reduces hallucination. And it demonstrates Azure's new native vector support feature, which is actually useful for production applications.

The example queries were clever too. Someone would ask "Wizarding World snacks," and the system would pull up the scene where Harry discovers Bertie Bott's Every Flavor Beans and chocolate frogs on the Hogwarts Express. Another prompt asked "How did Harry feel when he first learnt that he was a Wizard?" and retrieved the relevant opening chapters.

From a user experience perspective, it worked great. The answers were contextually relevant. They demonstrated the feature clearly. Developers reading the post could immediately understand the practical value.

But then came the fan fiction example. This is where things got really interesting, and arguably more problematic from a copyright perspective.

Kamath showed how the same system could generate new Harry Potter stories. The model would retrieve contextually similar passages from The Sorcerer's Stone, then use those passages to inform the generation of new creative content. She asked it to write a story where Harry meets a new friend on the Hogwarts Express who tells him about Microsoft's vector database capabilities.

The model actually did this. Drawing on authentic passages where Harry learns about Quidditch and meets Hermione Granger, the generated story created a plausible narrative where a new character promotes Microsoft's technology as if it were a magical spell.

That's not just using Harry Potter as training data. That's using Harry Potter's characters, settings, and narrative structure to create derivative works that promote Microsoft's products. Even if the generated text is technically new, it's built on and derived from Rowling's copyrighted creative work.

The Copyright Problem: Why This Matters Legally

Here's where the situation gets genuinely complicated, because Microsoft didn't explicitly tell developers to break copyright law. The blog post just... linked to data that shouldn't have been available.

But that distinction matters less than it seems.

U. S. copyright law doesn't require knowledge or intent to violate. If you use copyrighted material without permission, and you don't have a legal excuse like fair use, it's infringement. Period. The fact that Microsoft didn't upload the pirated content themselves doesn't shield them from liability if they knowingly encouraged its use.

The fair use question is genuinely uncertain here. Fair use has four factors: the purpose and character of the use, the nature of the copyrighted work, the amount of the work used, and the effect on the market value of the original.

Microsoft could argue this is transformative—using Harry Potter for educational purposes to teach developers about AI. But that argument is getting weaker as courts examine AI training cases more closely.

The Authors Guild, working alongside Stephen King and other major authors, filed a lawsuit against Open AI in 2023 claiming that GPT models were trained on copyrighted books without permission. The lawsuit hasn't concluded, but courts are taking the copyright concerns seriously. They're rejecting arguments that simply because content was available online means using it is fair use.

In 2024, Sarah Silverman and other comedians filed similar lawsuits against companies using their material to train models. Publishers sued Open AI. Artists filed suits against Midjourney and Stability AI.

The legal landscape is shifting. What seemed like a gray area a few years ago is becoming clearer: using copyrighted works to train AI without permission is increasingly likely to be found infringing.

So when Microsoft published a blog post showing developers exactly how to use copyrighted books to train AI models, they weren't just making an error of judgment. They were potentially encouraging infringement at a massive scale.

Because once developers read that post and saw how easy it was, they could replicate the exact approach with any copyrighted dataset available online.

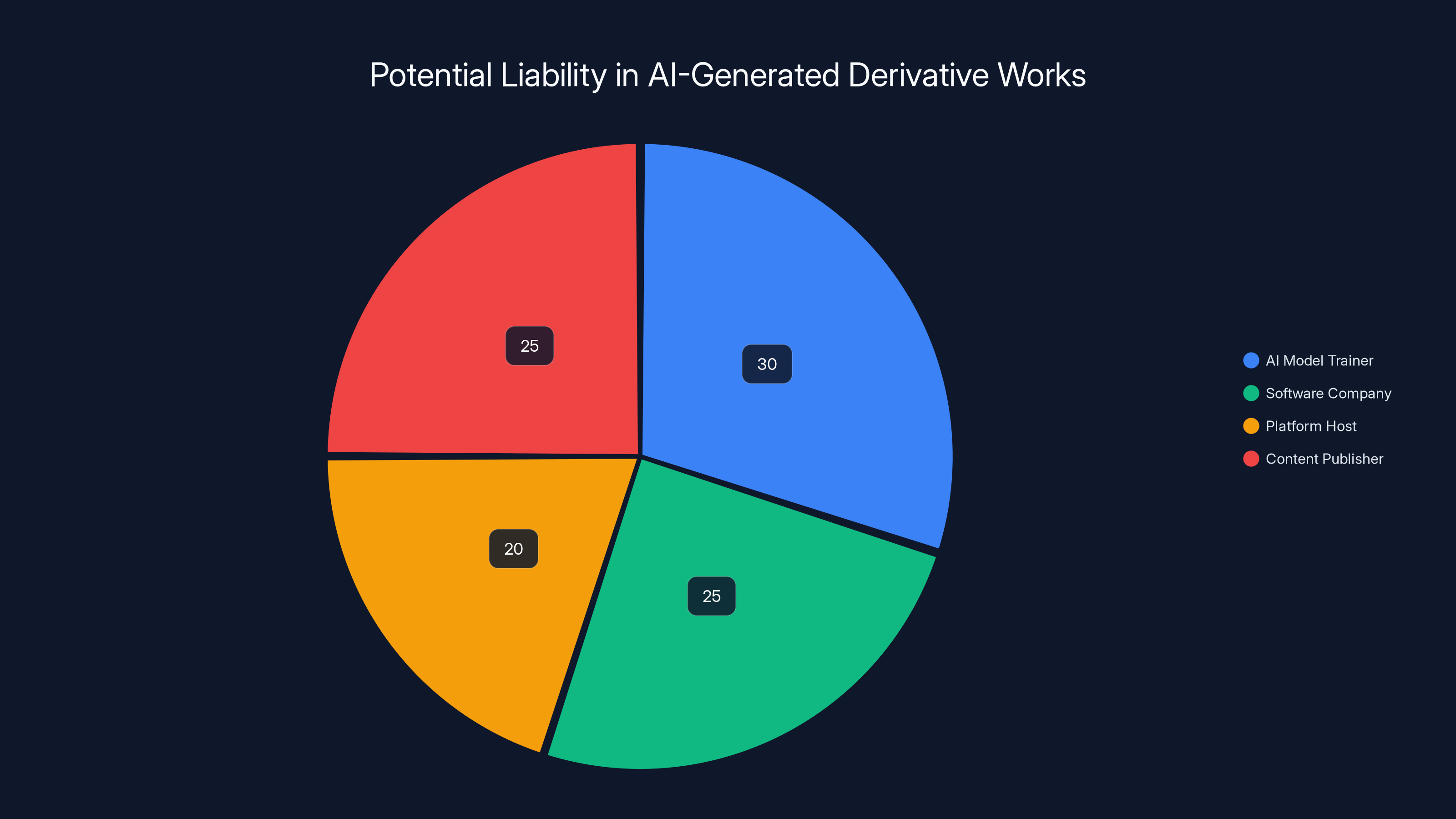

Estimated data suggests Microsoft has the highest potential liability due to their active role, but Kaggle and the dataset uploader also face significant risks. Estimated data.

Microsoft's Likely Defense: Plausible Deniability

When Microsoft's legal team reviewed what happened, they probably had several thoughts in quick succession.

First, they likely realized the blog post created significant liability. But then they also realized they had a workable defense: it wasn't Microsoft that uploaded the pirated books. It was a data scientist in India. Microsoft simply linked to publicly available data.

If the Kaggle dataset was labeled as public domain, Microsoft could claim reasonable reliance on Kaggle's labeling system. Kamath might have genuinely believed the books were in the public domain. It's possible—unlikely, but possible—that someone involved in approving the blog post wasn't familiar with Harry Potter copyright dates.

Law professor Cathay Y. N. Smith from Chicago-Kent College of Law made exactly this argument to media outlets: someone could be expert in technology and data science but not necessarily know that Harry Potter books are protected until 2047 (or even longer with potential copyright extensions).

That's a legitimate point. Copyright is complicated. Most tech people don't spend time memorizing publication dates and copyright terms. If something is marked public domain on a supposedly reputable platform, you might trust that label.

But here's the problem with that defense: Harry Potter is one of the most famous and commercially protected franchises in the world. Rowling is known for aggressively defending her intellectual property. The notion that a Microsoft senior product manager would select Harry Potter for a blog post about AI training without at least a moment's hesitation seems credulous.

If Kamath had searched for "Harry Potter copyright status" before writing the blog, she would have found thousands of results about Rowling's protective approach to the franchise. She would have learned that the books are heavily copyrighted. She would have realized the problem.

She either didn't search, or she searched and assumed the public domain label on Kaggle overrode everything else.

Either way, it suggests a level of carelessness that becomes harder to defend when scaled up to an organization as large as Microsoft.

The Bigger Picture: Why This Reveals a Systemic Problem

The Harry Potter blog post is embarrassing for Microsoft. But it's also a symptom of a much larger problem in how AI companies approach training data.

There's a fundamental misalignment between the constraints of copyright law and the practical realities of large-scale AI training. Building state-of-the-art language models requires vast amounts of text data. The internet contains vast amounts of text data. A lot of that text is copyrighted.

In the early days of AI, many companies treated this as a technical problem with a technical solution. Scrape the web. Download public repositories. Use whatever's available. Worry about copyright later.

Later is now. And companies are discovering that copyright holders take their rights seriously.

But there's a middle ground where companies—including Microsoft—have found themselves operating in a kind of gray zone. They don't officially endorse piracy. They don't explicitly tell developers to break the law. But they also don't prevent it. They don't actively avoid it. They link to datasets they haven't verified. They publish examples using copyrighted material.

It's plausible deniability at an institutional scale.

The Harry Potter example is particularly telling because it wasn't an accident. The blog post was intentionally published. It was reviewed and approved. Somewhere in Microsoft's editorial process, someone decided that using Harry Potter as an example was fine. Either they didn't verify the copyright status, or they verified it and assumed it didn't matter, or they assumed the Kaggle label was sufficient due diligence.

None of those are good looks.

And the broader implication is troubling: if Microsoft—a company with massive legal resources—can stumble into piracy this casually in official documentation, how many smaller companies are doing the same thing in less visible ways?

How many startups are training models on datasets scraped from the internet without verifying copyright status? How many developers are using copyrighted material for training data because it's convenient and nobody's caught them yet?

The Harry Potter blog post suggests the answer is: a lot of them.

Estimated data shows a potential distribution of liability among various stakeholders involved in AI-generated derivative works, highlighting the complexity of legal responsibility.

The Dataset Problem: Why Kaggle Matters More Than You Think

Kaggle is a platform owned by Google where data scientists share datasets. It's valuable. It's convenient. And it's also where a lot of improperly labeled or infringing content ends up.

The site has terms of service that say rights holders can submit DMCA takedown notices for infringing content. Repeated violations can get uploaders suspended. But enforcement is reactive, not proactive.

Someone uploads a dataset. It sits there. If nobody reports it, it stays. The system relies on rights holders actively monitoring and filing complaints. That works for some things—major copyright holders have legal teams that scan the internet for infringement.

But it's not perfect. The Harry Potter dataset had 10,000 downloads before Ars reached out. That's significant usage. And it went unnoticed for years.

Why? Probably because 10,000 downloads isn't a huge number in the grand scheme of Kaggle usage. The dataset wasn't trending. It wasn't being discussed widely. It was just... there. A small corner of the platform labeled with information that made people assume it was legal to use.

Then Microsoft linked to it. And suddenly it had visibility. Suddenly it mattered.

This reveals a second layer of the problem: platform responsibility. Should Kaggle have stronger verification procedures for datasets that claim to be public domain? Should they require proof? Should they automatically flag datasets containing works by living authors whose copyrights are obviously active?

They probably should. But they don't. And neither does any other platform that hosts user-generated datasets.

The burden falls on individual users to verify copyright status. Which is theoretically fine in principle. But in practice, it means that people who don't have legal expertise will make mistakes.

And those mistakes cascade. A mislabeled dataset becomes a blog post. A blog post becomes thousands of developers trained in a specific approach. Those developers replicate the approach with other copyrighted material.

The Fan Fiction Problem: Derivative Works in the AI Age

Let's zoom in on the fan fiction example for a moment, because it raises copyright questions that even the straightforward training data question doesn't.

Using Harry Potter books to train an AI is legally questionable. But Microsoft didn't just use the books as training data. They used the trained model to generate new content: AI-written Harry Potter fan fiction.

This is a different category of infringement. It's not just unauthorized reproduction. It's unauthorized creation of derivative works.

Under copyright law, the right to create derivative works is explicitly reserved for the copyright holder. If you create fan fiction and post it online, you're technically infringing, even if you're doing it as a fan and not for commercial purposes. Rowling's legal team has taken action against fan creators in the past (though they're generally more lenient with non-commercial fan works).

But what happens when the derivative work is created by an AI? Who bears liability? The person who trained the model? The company whose software was used? The company whose platform hosted the training data?

It's genuinely unclear. And Microsoft navigated straight into that ambiguity.

When Kamath had the model generate fan fiction incorporating Microsoft's product messaging, she was creating content that derived from Harry Potter's characters, settings, and narrative style. That content was generated using an AI trained on copyrighted material. And it was published on Microsoft's official blog to promote Microsoft's product.

It's hard to imagine a copyright holder viewing that as anything other than infringement. The fact that the fan fiction also served as advertising for Microsoft makes it even worse from Rowling's perspective.

Because now it's not just using her work for educational purposes. It's using her work, her characters, and her IP to increase the market value and visibility of a Microsoft product.

That's the kind of use that copyright law is explicitly designed to prevent.

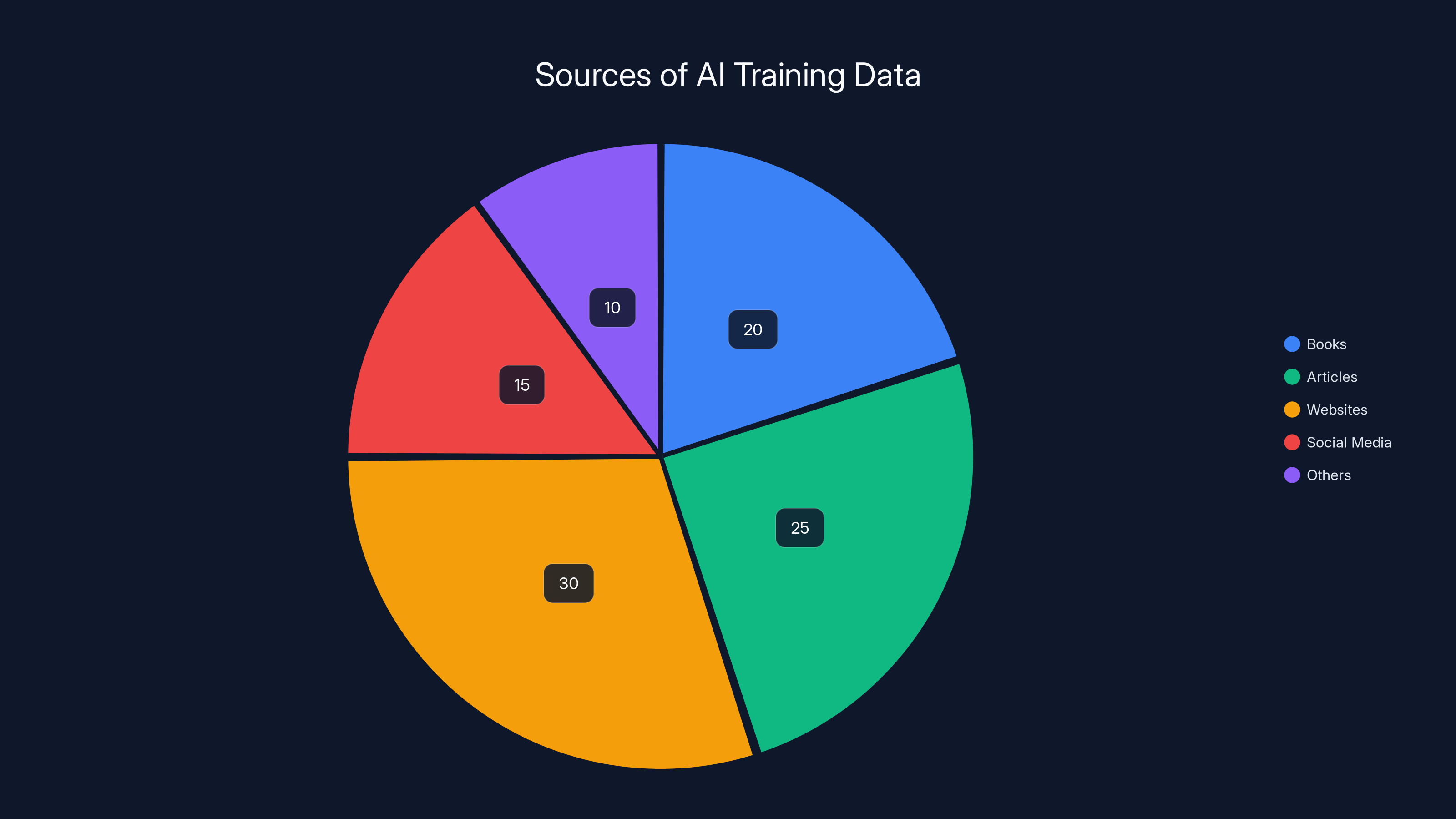

AI models are trained on diverse text sources, with websites and articles being the largest contributors. Estimated data.

Legal Liability: Who's Actually Responsible?

Now here's the interesting legal question: who bears liability for this incident?

On the surface, the answer seems clear. Microsoft published the blog post. Microsoft linked to the infringing dataset. Microsoft had the model generate derivative works using that data. So Microsoft is liable.

But Microsoft would almost certainly argue a more nuanced position. They would say:

First, they didn't upload the pirated content. A third party did. Microsoft simply linked to it. Under Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, platforms generally aren't liable for user-generated content posted by others.

Second, the Kaggle dataset was publicly labeled as public domain. Microsoft relied on that label. If the label was wrong, that's Kaggle's problem and the dataset uploader's problem, not Microsoft's.

Third, the blog post's purpose was educational—showing developers how to use Azure's features. The actual copyright infringement, if any, would be on the part of individual developers who downloaded and used the dataset, not on Microsoft.

These are not unreasonable arguments. They might not prevail in court, but they're coherent legal positions.

J. K. Rowling's legal team, by contrast, would probably argue:

Microsoft had actual knowledge that the dataset contained copyrighted works. They published detailed instructions showing how to use those works. They created derivative works using those instructions. They promoted this capability in official documentation. This goes beyond linking to content—it's actively facilitating and encouraging infringement.

Wilful infringement carries statutory damages of up to $150,000 per work. If the Harry Potter books count as seven separate works, and if the courts find Microsoft's actions wilful, the potential damages are substantial.

But would it come to that? Almost certainly not. Microsoft has legal resources and negotiating power. If Rowling's team pursued this, they'd likely settle confidentially. Microsoft would probably agree to remove the content, implement better verification procedures, and perhaps make a financial payment.

The broader point is that the legal ambiguity is part of what makes these situations so common. Companies operate in gray areas because the gray areas genuinely exist. Copyright law hasn't caught up with AI training practices. Courts are still figuring out how fair use applies. Platforms are still developing policies.

Microsoft's mistake was in the execution and visibility, not in the underlying approach. Many companies are doing similar things in less visible ways.

The Broader AI Training Problem: Beyond Harry Potter

The Harry Potter incident is just one example of a much larger issue in AI development: the routine, often invisible use of copyrighted material for training data.

Large language models are trained on massive corpora of text. That text comes from books, articles, websites, social media, and countless other sources. A significant portion of that text is copyrighted.

Artists and authors didn't consent to this usage. Most never even knew it was happening. It was just... part of the internet. Available for scraping. Available for use.

The creators of GPT-2, GPT-3, and GPT-4 trained on vast amounts of internet text. So did the creators of Claude, Gemini, and other large models. They all encountered copyrighted material in their training data. Some companies explicitly excluded books from certain publishers. Others didn't.

None of them asked permission from every single author or publisher. That would be logistically impossible.

So the industry has operated on an implicit assumption: that using copyrighted material for AI training falls under fair use, or that the training data isn't protected, or that copyright holders won't pursue legal action.

That assumption is being tested in court. And the courts are increasingly skeptical.

In 2023, The New York Times, which has a massive amount of copyrighted content that almost certainly ended up in training datasets, began discussing potential legal action against AI companies. In 2024, they actually sued Open AI and Microsoft.

That lawsuit is significant because The New York Times is massive, wealthy, and has the resources to pursue expensive litigation. And their lawsuit isn't just about GPT-4 consuming articles. It's about the broader principle that creators should have control over how their work is used, especially for commercial purposes.

If courts rule in favor of the Times, it could reshape the entire AI training landscape.

Companies might need to:

- Obtain licenses for training data

- Exclude specific copyrighted works at the request of rights holders

- Develop "opt-out" mechanisms where creators can prevent their work from being used

- Implement more careful verification of training data sources

All of these would be expensive. And they would slow down the pace of AI development.

But they might also be legally necessary.

The Harry Potter blog post is a reminder that this reckoning is happening now. It's not a future problem. It's a present problem that companies are just beginning to grapple with seriously.

The impact of Microsoft's blog post increased over time, peaking when the issue was highlighted on Hacker News, leading to the blog's deletion. Estimated data.

Microsoft's Response: Or Lack Thereof

Microsoft declined to comment to media outlets about the deleted blog post. That's a choice. It's a legitimate choice from a legal perspective—never admit more than you have to. But it's also a choice that invites speculation and narrative control by others.

The company could have said: "We made a mistake. We linked to a dataset that was mislabeled. We've removed the content. We're implementing better verification procedures." That would have been a reasonable, human response.

Instead, they deleted everything and went silent. Which makes the incident look worse. It looks like they're hiding something. It looks like they're hoping it goes away.

Kaggle also didn't respond to media requests for comment. Google, which owns Kaggle, stayed silent.

The dataset uploader, Maindola, did respond, and took responsibility for the mislabeling. That's commendable. It's also convenient for Microsoft and Google, because it lets them distance themselves from the error.

But from a PR perspective, Microsoft's silence was a mistake. In an era where transparency and acknowledgment of errors builds trust, complete radio silence reads as arrogance or contempt.

Small companies dealing with public relations crises often understand this instinctively. They respond quickly, apologize, explain what went wrong, and describe corrective measures. Their transparency often actually improves public perception despite the underlying error.

Microsoft, being very large, probably calculated that acknowledging the error would create more liability than silence would. They probably discussed it with their legal team. They probably decided that any public statement could be used against them in future litigation.

Maybe that's the right calculation from a legal standpoint. But it's the wrong calculation from a trust and credibility standpoint.

What This Reveals About AI Development Standards

The Harry Potter incident illuminates something uncomfortable about how rapidly AI has scaled in the tech industry: the standards haven't kept pace.

Microsoft is a company that employs thousands of lawyers. They have compliance departments. They have risk management processes. They have editorial review for official technical documentation.

Somewhere in that entire apparatus, a blog post got published that linked to and promoted the use of clearly infringing content. That suggests one of two things:

Either the verification and review processes aren't actually effective, or they were bypassed because speed was prioritized over caution.

Given how fast AI has moved in the last two years, the second explanation seems more likely. Teams building AI features are working under intense pressure to demonstrate capabilities and achieve proof-of-concepts. Compliance takes time. Verification takes time. Getting legal sign-off takes time.

So sometimes you cut corners. You assume a public dataset is fine because it's on a major platform. You skip the copyright verification step. You focus on the technical demonstration rather than the legal implications.

It's exactly the kind of thing that becomes a scandal when it gets public attention.

But the real question is: how many other corners are being cut? How many other datasets are mislabeled? How many other companies are linking to or using infringing material?n The Harry Potter case was visible because Harry Potter is famous. But there are probably thousands of obscure datasets on Kaggle with incorrect licensing. There are probably hundreds of blog posts and tutorials linking to or using infringing material in ways that are less visible.

The incident suggests that the AI industry has normalized a certain level of IP risk that many companies probably shouldn't be normalizing.

The Precedent Question: Does This Change Anything?

Here's a crucial question: will the Harry Potter incident actually change how AI companies approach training data and documentation?

Probably not much. At least not immediately.

What it does change is the conversation. It makes the issue visible. It shows that even well-resourced, legally sophisticated companies can end up promoting infringement if they're not careful.

That's useful information for other companies. It's a cautionary tale.

But it doesn't solve the underlying structural problem: the AI industry depends on large amounts of text data, and text data on the internet is heavily copyrighted. Until copyright law or licensing practices catch up with AI training realities, companies will continue to operate in gray areas.

What might change is enforcement. If the New York Times lawsuit against Open AI is successful, it opens the door to broader litigation against AI companies. That could force more careful practices around training data.

But that's a court decision away. It could take years.

In the meantime, the incentives haven't changed. Building better AI models requires more training data. More training data means more copyright risk. Accepting that risk has been standard industry practice.

One deleted blog post doesn't change the equation.

It does, however, make it harder for companies to claim ignorance. Everyone now knows that using copyrighted material to train AI without explicit permission is legally questionable. That knowledge raises the stakes for anyone who does it anyway.

Fair Use in the AI Age: What Does It Actually Mean?

Throughout this incident, one legal concept keeps surfacing: fair use. It's worth understanding what it actually is, because it's central to how courts might eventually rule on AI training practices.

Fair use is a doctrine in U. S. copyright law that allows limited use of copyrighted material without permission in certain circumstances. The factors courts consider are:

- The purpose and character of the use (educational, transformative, etc.)

- The nature of the copyrighted work

- The amount of the work used relative to the whole

- The effect of the use on the market value of the original work

For educational purposes, fair use is often broader. For commercial purposes, it's often narrower. Transformative uses—where the original work is used in a new way that adds value—are often protected. Uses that directly compete with or substitute for the original work are often not.

Now, here's where AI training gets complicated. Is training an AI model on copyrighted books a fair use?

Arguments in favor:

- It's arguably transformative. The model learns patterns but doesn't reproduce the books.

- It's not for the primary purpose of commercial gain from the books themselves.

- It advances technology and innovation.

Arguments against:

- It uses the entire copyrighted works, not just excerpts.

- It can result in the model outputting passages similar to or identical with the original works.

- It replaces the market for the original works—why read the book if the AI can summarize or paraphrase it?

- It's primarily a commercial enterprise using others' creativity without compensation.

Courts are starting to weigh in. In early 2024, the U. S. Copyright Office issued guidance suggesting that training AI models on copyrighted works is not necessarily fair use, especially for commercial purposes.

The New York Times lawsuit asks courts to clarify this precisely. And the answer could reshape the entire AI training landscape.

If courts rule that AI training on copyrighted works is generally not fair use, companies will need to:

- Seek licenses for training data

- Exclude copyrighted works

- Develop opt-in or opt-out systems

- Potentially pay royalties to rights holders

All of this would slow development and increase costs. But it would also align with copyright law as it's traditionally been understood.

What Developers Should Do: Practical Guidelines

If you're a developer reading about this incident and wondering what it means for your work, here are some practical considerations:

First, be cautious about datasets that claim to be public domain. Verify the claim independently. Look up copyright dates. Check whether the original creator has made any statements about IP licensing. A label on a platform doesn't constitute verification.

Second, if you're using copyrighted material for training data, understand that you're operating in legal gray area. That doesn't necessarily mean you shouldn't do it, but it means you should do it with eyes open.

Third, if you're working for a company or in a professional context, escalate IP questions to legal. Don't assume someone else has verified this. Don't assume that because something is available online, it's fine to use.

Fourth, when possible, use openly licensed datasets. Creative Commons, public domain, or explicitly licensed data exists. It's often smaller or more limited, but it's legally clear.

Fifth, if you create something using copyrighted training data and it works really well, think carefully about how public you want to make it. A private tool is lower-risk than a published library or commercial product.

These aren't guaranteed to keep you safe. But they're reasonable precautions in an uncertain legal environment.

The Future: Where This Is Heading

The Harry Potter incident is unlikely to be the last time we see AI companies stumble on copyright issues.

More likely, we'll see continued litigation. The New York Times case will probably succeed at least partially. Other publishers and authors will sue. Courts will develop clearer precedent.

That precedent will push companies toward more careful practices. It might also push toward legislative solutions—new laws that specifically address AI training and copyright.

We might see the development of licensing frameworks where AI companies pay for training data. Similar to how streaming music services pay royalties, AI companies could pay for rights to use text in training datasets.

We might see technological solutions like watermarking or metadata that allows creators to opt out of AI training.

We might see copyright reform that specifically addresses AI—clarifying what is and isn't allowed, establishing licensing frameworks, or creating new rights for creators.

All of these would be good developments. They would create clarity and align incentives appropriately.

In the near term, though, expect more cautious practices from large companies. Expect more careful verification of training data. Expect more conversations between legal and product teams.

Expect fewer blog posts casually linking to datasets without verification.

And expect continued tension between what's technically possible in AI development and what's legally permissible with copyrighted material.

Lessons for Tech Companies Everywhere

The Harry Potter incident is a case study in how even sophisticated companies can stumble on compliance and ethics issues when moving fast.

The lessons apply broadly:

First lesson: Speed and accuracy aren't always compatible. When you're moving fast, you're more likely to make mistakes. That doesn't mean always move slowly, but it means being conscious of where speed creates risk.

Second lesson: Platform reliance is risky. When you rely on third-party platforms to manage compliance (Kaggle for dataset licensing, for example), you're assuming that platform is handling it correctly. They often aren't. Do your own verification.

Third lesson: Fame creates risk. Using Harry Potter as an example was appealing because it's famous and relatable. But famous works have active, aggressive IP protection. Using obscure or explicitly licensed material would have been safer.

Fourth lesson: Transparency beats secrecy. Microsoft's silence about the deleted blog post made it worse. A straightforward acknowledgment of the mistake and explanation of what they're doing about it would have been better for their reputation.

Fifth lesson: Legal and product teams need to collaborate earlier. If lawyers had reviewed this blog post before publication, the problem would have been caught. Instead, it seems like lawyers only got involved after the fact.

These aren't unique to Microsoft or to AI. They're lessons that apply to any company moving fast in an area with significant legal implications.

The Bigger Conversation: AI Ethics Beyond Law

While the Harry Potter incident is primarily a copyright and legal issue, it also touches on broader questions about AI ethics.

Copyright is a property right, a legal concept. But underlying copyright are broader principles: creators should have control over their work, creators should be compensated for their labor, and creators shouldn't have their work used to build competing products without their consent.

AI training on copyrighted material raises these issues at a new scale.

When one author's book is copied without permission, they can pursue legal action. When thousands of authors' books are used in training without permission, the scale overwhelms individual enforcement.

When AI models can generate text that mimics particular authors' styles, there's an additional concern: are we creating tools that make it easier to impersonate or create derivative works without those authors' control?

These are questions that law will eventually address. But they're also questions that the AI industry itself should be thinking about now, before legal requirements force action.

Companies that build ethical practices proactively will have advantages when legal requirements inevitably tighten. They'll have better relationships with creators. They'll have cleaner data. They'll face less litigation.

Microsoft could have taken the Harry Potter issue as an opportunity to signal that it takes creator rights seriously. Instead, it deleted the blog post and went silent.

That's a missed opportunity for leadership.

FAQ

What exactly did Microsoft's blog post tell people to do?

Microsoft's blog post showed developers how to train AI language models using books from a Harry Potter dataset on Kaggle, then use those models to build chatbots that answer questions about the books and generate new Harry Potter fan fiction. The blog included step-by-step instructions and example outputs demonstrating the entire process.

Why is using copyrighted books to train AI illegal?

Using copyrighted works without permission violates the copyright holder's exclusive right to reproduce and create derivative works from their material. While there's legal debate about whether AI training qualifies as "fair use," courts are increasingly skeptical that commercial AI companies can claim fair use when training on copyrighted works without permission or compensation to the creators.

How did Microsoft not know the books were copyrighted?

The Harry Potter books were marked as "public domain" on Kaggle, which is the platform hosting the dataset. Microsoft may have reasonably relied on that label as accurate. However, the books are clearly still under copyright (they won't enter public domain for decades), so either the person who uploaded the dataset mislabeled it, or Microsoft should have done independent verification rather than trusting the platform's label.

What are the legal consequences Microsoft could face?

Microsoft could potentially face copyright infringement lawsuits from J. K. Rowling or her representatives. The risks include injunctions forcing removal of infringing content, actual damages (the profits earned from infringement), and statutory damages (up to $150,000 per copyrighted work if infringement is found to be wilful). However, Microsoft's size and resources mean they would likely negotiate a settlement rather than face court proceedings.

Does this mean all AI training on internet data is illegal?

No, but it exists in a legal gray area. Courts are beginning to weigh in on what constitutes fair use for AI training. The New York Times lawsuit against Open AI and Microsoft will likely establish clearer precedent about whether and when AI companies can legally train models on copyrighted works without permission. Current law is still evolving in this area.

What should developers do differently based on this incident?

Developers should independently verify the licensing status of any datasets they use, rather than trusting platform labels alone. When possible, use openly licensed data or data with explicit machine learning permissions. If using copyrighted material, understand you're assuming legal risk. And for professional work, involve legal teams early in project planning rather than after potential problems emerge.

Could this happen with other copyrighted content besides books?

Absolutely. The same problem exists with copyrighted images, music, code, articles, and other creative works. Any time copyrighted material is mislabeled or improperly licensed on platforms like Kaggle, Git Hub, or others, it can accidentally end up in AI training datasets. The Harry Potter case is visible because it involves famous IP, but thousands of other copyrighted works probably face similar risks.

How is the Harry Potter dataset situation different from general web scraping?

The key difference is that Microsoft actively promoted a specific dataset in official documentation, showing developers exactly how to use it for AI training. This goes beyond general web scraping that many AI companies do. Microsoft's link and instructions made the infringing dataset more discoverable and more likely to be used, which increases their potential liability compared to a company that simply trained on web-scraped data without explicitly promoting it.

Will this lead to legal changes in how AI companies can train models?

Likely yes. The New York Times lawsuit, combined with other author and publisher suits, will establish legal precedent that probably restricts how freely AI companies can use copyrighted material. Additionally, legislation is being considered that would specifically address AI training on copyrighted works, potentially requiring licenses, creating opt-out mechanisms, or establishing new royalty frameworks similar to those used for music streaming.

Why did Microsoft delete the blog post without explanation?

Microsoft likely consulted with legal counsel and determined that any public statement could be used against them in future litigation. They also may have wanted to minimize attention to the incident. However, this approach backfired from a PR perspective—silence made the incident look worse and invited more speculation. A transparent acknowledgment and explanation of corrective measures would probably have been better for their reputation.

The Harry Potter incident is a reminder that even massive, sophisticated companies can stumble when copyright and AI development intersect. It's a visible example of systemic problems in how training data is sourced, labeled, and used. And it's a preview of the legal battles that will shape AI development in the coming years.

For Microsoft, it was an embarrassing mistake. For the broader AI industry, it's a cautionary tale about the importance of taking intellectual property seriously, building ethics and compliance into product development early, and understanding that the regulatory environment around AI is tightening.

The companies that navigate this transition successfully will be those that get ahead of the legal requirements and build creator-friendly practices proactively. Everyone else will be playing catch-up when courts and regulators finally impose requirements.

Key Takeaways

- Microsoft published and later deleted a blog post showing developers how to train AI models using all seven Harry Potter books mislabeled as public domain on Kaggle

- Using copyrighted works to train AI without permission increasingly violates copyright law, as courts reject fair use arguments for commercial AI training

- The incident reveals systemic problems where platforms mislabel data and companies skip verification steps when moving fast to deploy AI features

- Multiple lawsuits from authors and publishers like the New York Times are establishing legal precedent that AI companies cannot freely use copyrighted training data

- Developers should independently verify dataset licensing, prioritize openly licensed data, and involve legal teams early rather than treating copyright as an afterthought

Related Articles

- ByteDance's Seedance 2.0 AI Video Generator Faces IP Crisis [2025]

- ByteDance's Seedance 2.0 Deepfake Disaster: What Went Wrong [2025]

- Music Publishers Sue Anthropic for $3B Over AI Training Data Piracy [2025]

- UK AI Copyright Law: Why 97% of Public Wants Opt-In Over Government's Opt-Out Plan [2025]

- Artists vs. AI: The Copyright Fight Reshaping Tech [2025]

![Microsoft's Deleted Blog: The AI Piracy Scandal Explained [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/microsoft-s-deleted-blog-the-ai-piracy-scandal-explained-202/image-1-1771591075281.jpg)