Space X's Audacious Plan to Build a Trillion-Dollar Space Infrastructure

Elon Musk's company just filed something wild with the FCC. Not just a request. Not just ambitious. A complete reimagining of how humanity could power artificial intelligence at scale.

Space X wants to launch one million solar-powered satellites into orbit. Not the Starlink internet satellites most people know about. These are different. These are AI data centers orbiting the Earth, powered by the sun, designed to handle the explosive computational demands of modern artificial intelligence. According to Space News, this initiative is set to redefine the future of computing infrastructure.

Let that sink in for a moment. One million satellites. Each one functioning as a distributed data center. All of them powered by renewable energy harvested directly from the sun.

The filing wasn't subtle about its ambitions. Space X described this constellation as "the most efficient way to meet the accelerating demand for AI computing power." But then they went further, claiming it represents "a first step towards becoming a Kardashev II-level civilization," referring to a theoretical framework where a civilization harnesses the entire energy output of a star. This ambitious vision was highlighted in TechBuzz AI's article on the subject.

This isn't science fiction anymore. It's a federal filing. And it raises fascinating questions about the future of computing, space sustainability, and whether this idea will ever actually happen.

Let me break down what's actually happening here, what it could mean, and why the FCC might say no.

The Current State of AI Computing Infrastructure

Understanding why Space X proposed this requires understanding the AI computing crisis happening right now.

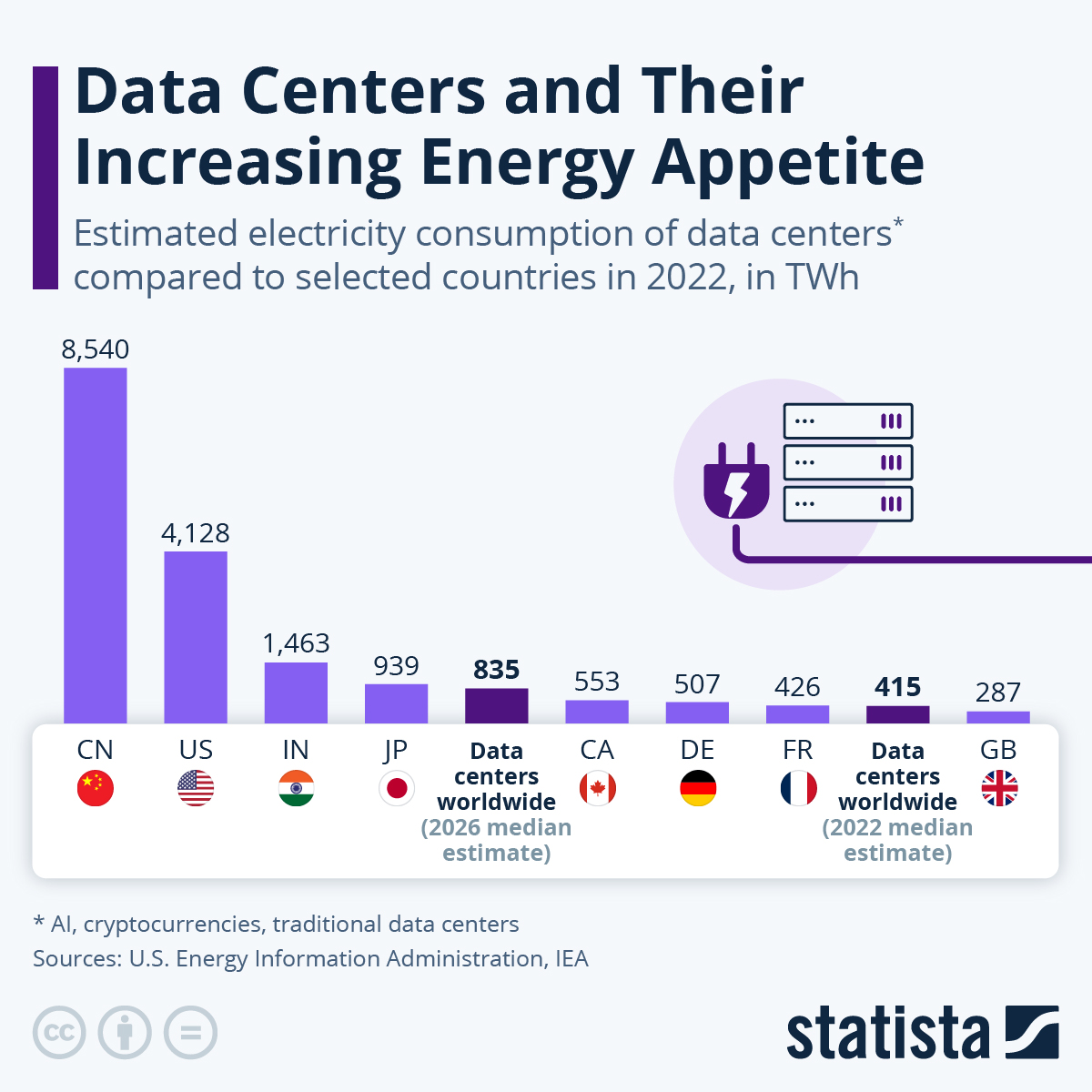

Data centers are everywhere. Massive buildings consuming absurd amounts of electricity. Open AI's training runs. Google's model development. Microsoft's Azure infrastructure. Amazon's AWS. All of these require power on a scale that's challenging the grid. According to Ohio Capital Journal, the energy demands of these centers are becoming a significant public concern.

A single large AI training run can consume 15,000 megawatt-hours of electricity. That's equivalent to the annual electricity consumption of 1,200 American homes, burned through in weeks. Some estimates suggest that training a single large language model generates carbon emissions equivalent to driving a car for 300,000 miles.

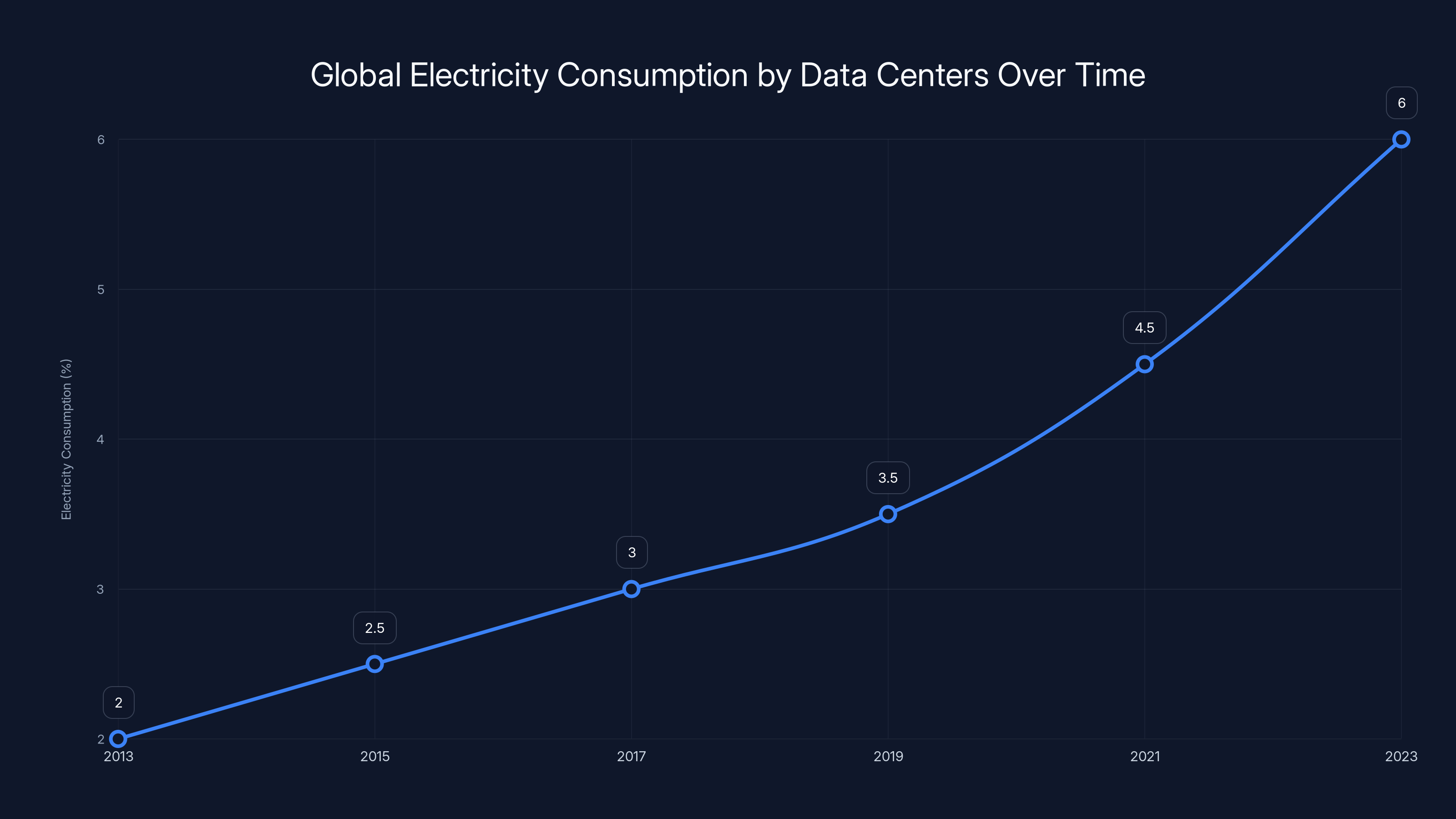

Data centers already account for roughly 4-6% of global electricity consumption, according to recent analyses. This number was 2% just a decade ago. The trend is accelerating, not slowing. Energi Media provides an insightful overview of this rapid growth.

Why? Because AI models are getting bigger. Training runs are more frequent. Inference (the actual usage of trained models) is exploding. Companies like Open AI, Google, and Anthropic are all racing to build larger models that require exponentially more compute.

The fundamental problem is that electricity costs are increasing, availability is limited, and traditional grid infrastructure can't keep pace. A massive data center in Virginia might consume 500 megawatts of continuous power. That's more than some entire countries use.

Space X's proposal offers a radical solution: put the computing power where the energy is unlimited and free. In space. Powered directly by the sun.

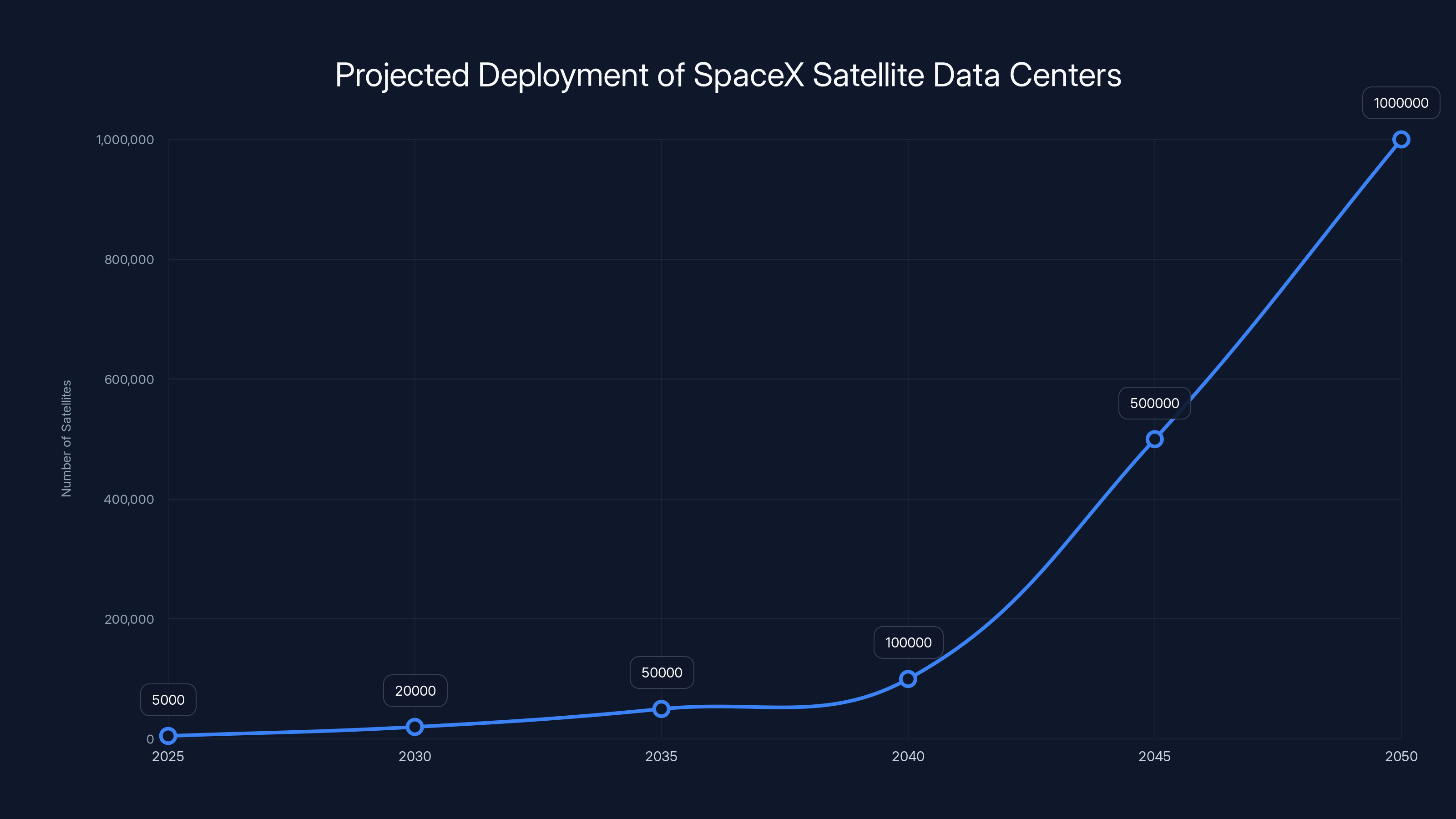

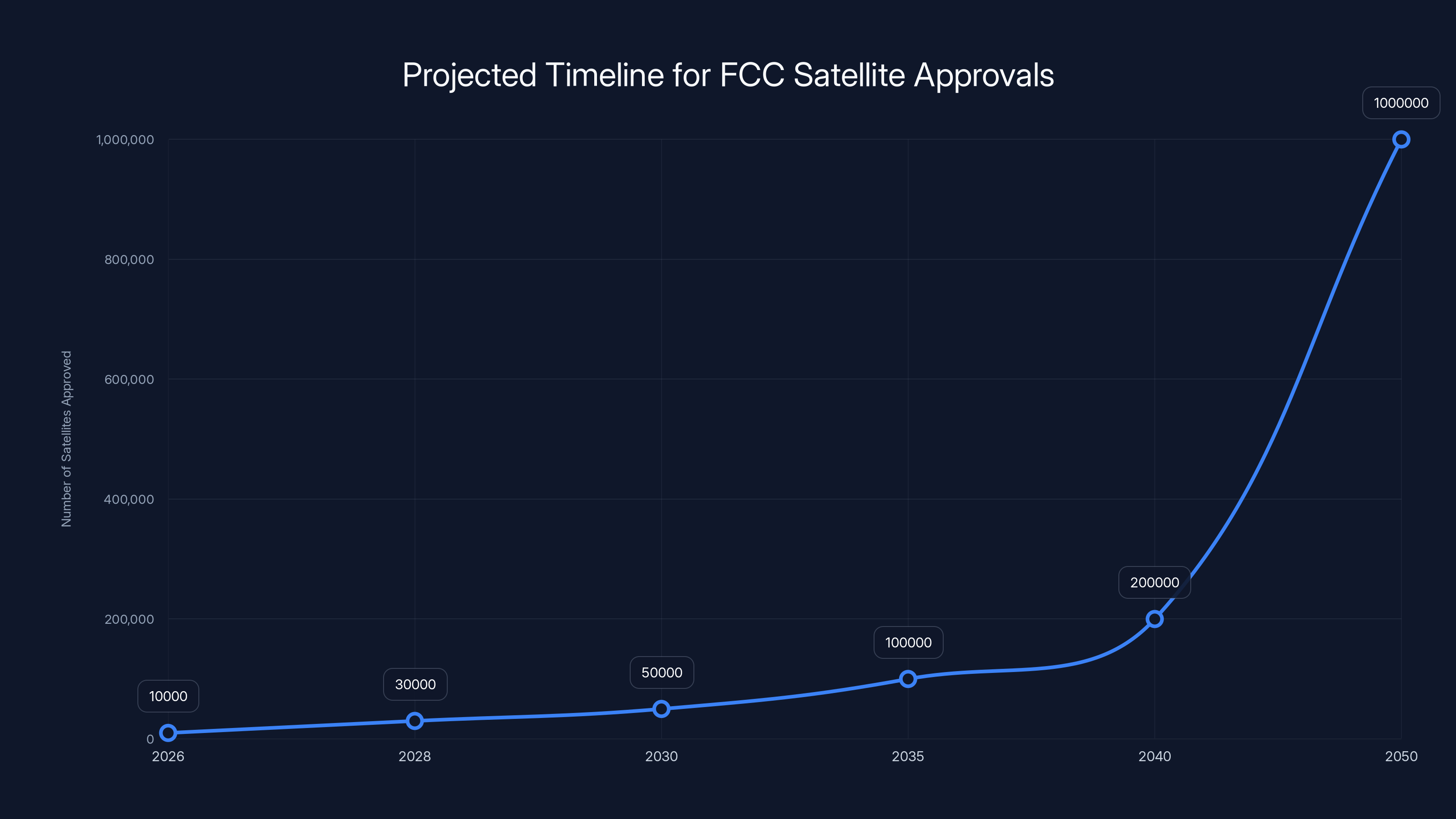

Estimated data suggests a phased deployment starting with 5,000 satellites by 2025, potentially reaching one million by 2050, contingent on FCC approvals and technological advancements.

Why Solar-Powered Satellites Make Theoretical Sense

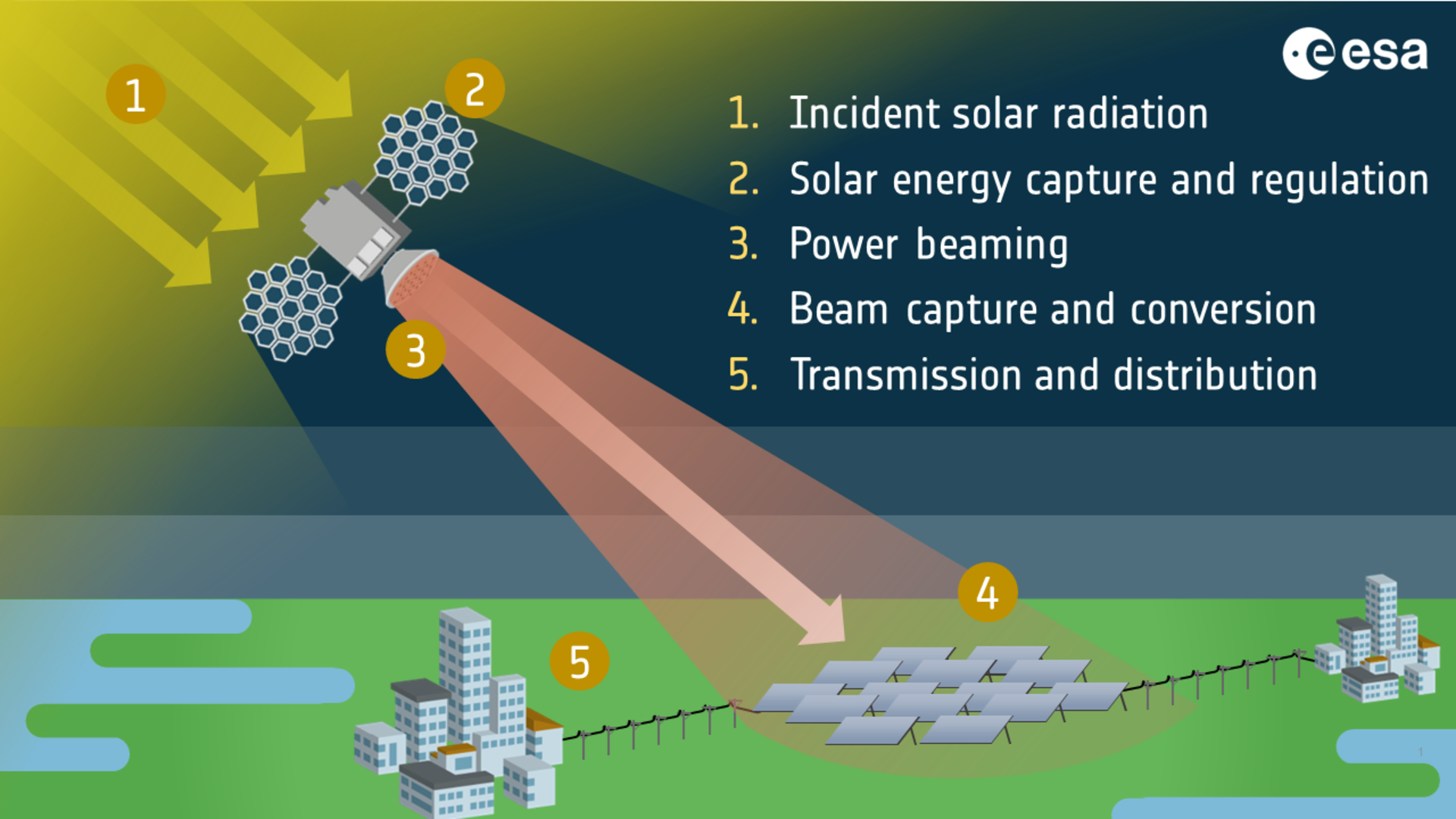

The physics here is compelling.

Earth receives approximately 174 petawatts of solar energy every single second. That's 174 with 15 zeros after it. In watts. Per second.

We use about 18 terawatts of power globally. That means the sun delivers about 10,000 times more energy than humanity currently consumes, continuously hitting our planet.

The problem? We're inefficient at capturing it. Solar panels are about 20-25% efficient at converting sunlight to electricity. Then you need inverters (90-95% efficient). Then transmission losses. Then cooling for data centers. The round-trip efficiency is roughly 15-20%.

But in space, everything changes. There's no atmosphere to scatter photons. No clouds. No night. The sun delivers consistent, uninterrupted power 24/7 (from the satellite's perspective, always facing the sun through proper orbit positioning).

A solar panel in orbit receives about 1,361 watts per square meter of power. That's called the solar constant. On Earth, accounting for atmospheric losses and the angle of the sun, you get about 1,000 watts per square meter maximum at midday.

So orbital solar panels receive roughly 36% more raw energy. More importantly, they receive it constantly, without weather interference or day-night cycles.

This is why theoretical space-based solar power has always been attractive. For AI data centers specifically, it's almost too good to be true. Unlimited power. Clean energy. No grid infrastructure required. Project Disco discusses the potential of space-based data centers in unlocking new frontiers for big data.

The challenge isn't physics. It's engineering, cost, and whether society will actually allow this.

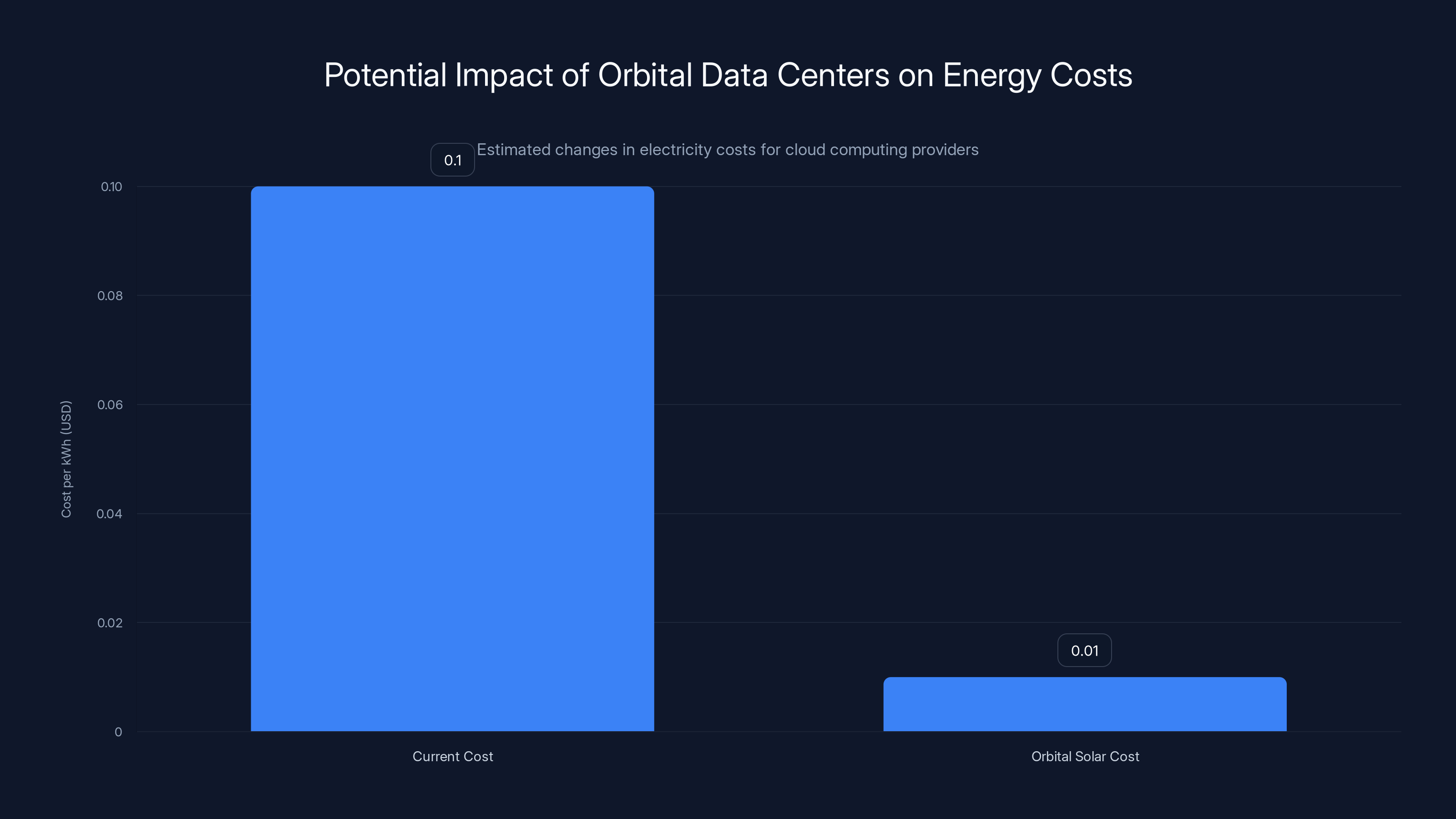

Estimated data shows that orbital solar power could reduce electricity costs for cloud computing from

Understanding the Kardashev Scale Reference

When Space X mentioned "Kardashev II-level civilization," they weren't just being poetic.

Nikolai Kardashev, a Soviet astrophysicist, proposed a theoretical framework in 1964 for categorizing civilizations based on their energy consumption:

- Type I: A civilization that controls all energy on its home planet. About watts.

- Type II: A civilization that harnesses all energy from its star. About watts.

- Type III: A civilization that controls energy across an entire galaxy. About watts.

Earth's current civilization consumes about

A true Type II civilization wouldn't need only one million satellites. They'd wrap an entire star in solar collectors. But building massive orbital infrastructure that harvests solar energy is genuinely a step in that direction.

Space X framing this as a path to Type II status is ambitious rhetoric. But it's not entirely dishonest. Building orbital infrastructure to capture stellar energy is precisely how humanity would begin climbing the Kardashev scale.

The company is essentially saying: "This is how you start. One million data centers. Then, eventually, Dyson spheres around the sun."

Whether they actually believe this will happen or whether it's strategic framing for regulators is debatable.

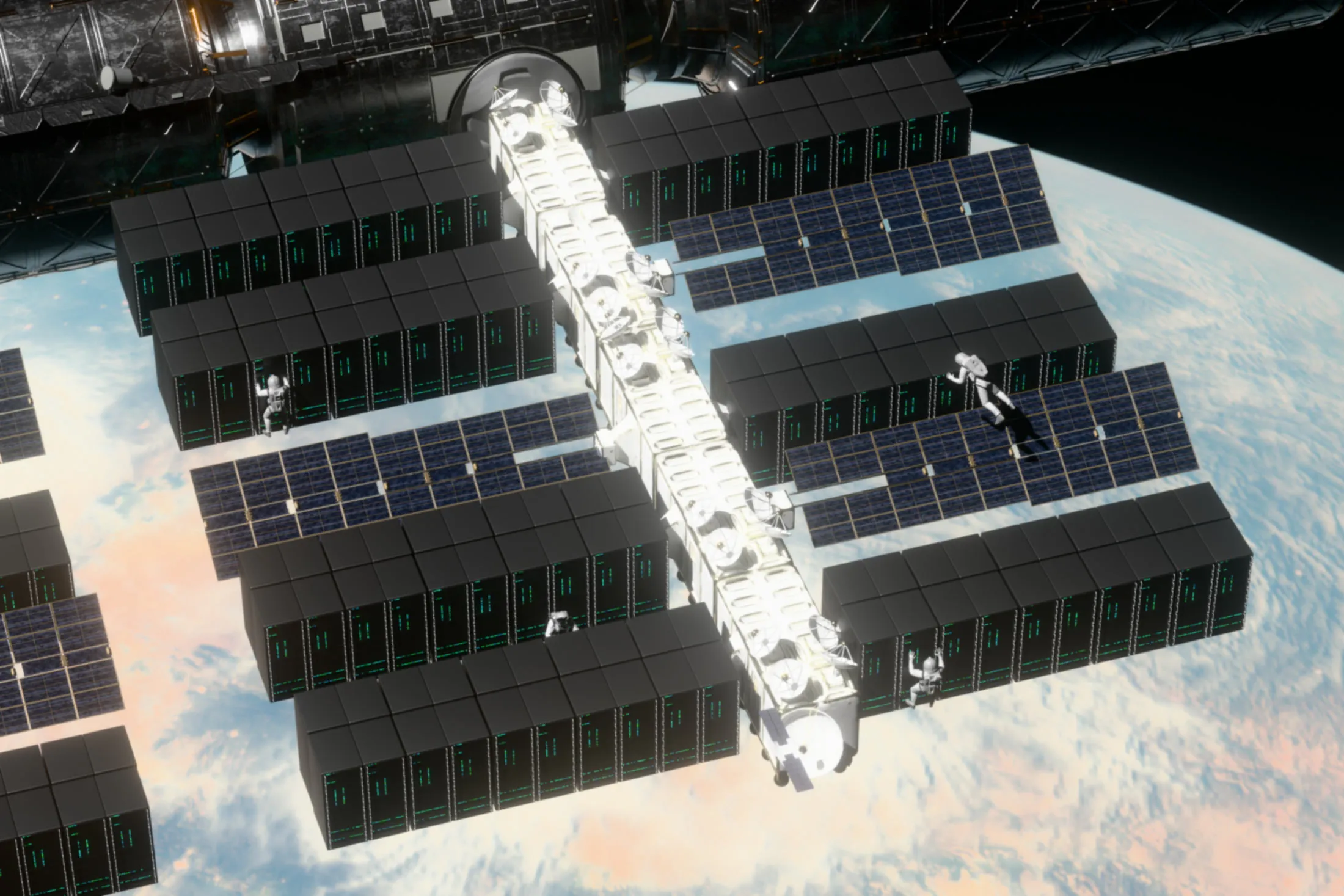

The Technical Architecture: How These Satellites Would Work

The filing doesn't specify engineering details, but orbital solar-powered data centers would need several key components.

Power Generation: Solar panels facing the sun. For a satellite providing 100 kilowatts of computing power, you'd need roughly 600-800 square meters of solar panels (accounting for efficiency losses and thermal dissipation). That's a square about 27 meters on each side. Feasible, but large.

Computing Hardware: Traditional processors, memory, and storage would work in space, though they'd need radiation shielding. Cosmic rays and solar radiation can cause bit flips and component degradation. The vacuum environment is actually beneficial for cooling, since there's no air resistance or convection to contend with.

Thermal Management: This is the hard part. Data centers generate enormous heat. On Earth, you use water cooling or air conditioning. In vacuum, you can only radiate heat. That means large radiator panels. For a 100-kilowatt data center, you'd need roughly 400-500 square meters of radiator surface. The satellite would be massive.

Power Delivery and Bandwidth: Data needs to move. Output from the satellites needs to reach ground stations, then reach users. This requires either laser communication (high bandwidth, directional) or radio frequency links. Latency would be 250+ milliseconds just from the signal travel time (300,000 km/second, satellites at roughly 35,000-36,000 km altitude for geostationary orbit, but the filing doesn't specify altitude).

Orbital Mechanics: One million satellites requires careful spacing. They can't collide. They can't create excessive debris. They need deorbiting mechanisms for end-of-life. Space X's Starlink constellation has about 6,000 active satellites and already faces scrutiny for collision risks and light pollution.

The architecture is plausible. Not easy, but plausible.

Data centers' electricity consumption has tripled from 2% to 6% of global usage over the past decade, driven by the growth of AI computing demands. Estimated data.

The FCC's Regulatory Maze and Previous Decisions

Space X can't just launch satellites. The FCC regulates orbital allocations and spectrum. The company needs approval for each constellation phase. Reuters provides an overview of the regulatory challenges Space X faces.

For Starlink, the approval process took years. Space X first applied in 2016. FCC approval finally came in 2018. But the approval was phased: permission to launch some satellites, then requests to launch more, conditional approval pending certain standards, and ongoing negotiations about debris mitigation.

As of early 2025, Space X has launched roughly 6,000 Starlink satellites. The company requested permission for 12,000. The FCC approved additional launches to 7,500 satellites but deferred authorization on the remaining 14,988.

For the one million satellite proposal, expect a similar glacial process.

FCC's likely concerns:

Orbital Debris: More satellites mean more collision risk. NASA estimates there are currently 34,000 pieces of tracked debris larger than 10 centimeters in low Earth orbit. Untracked pieces? Millions. A collision between two objects at 17,500 miles per hour creates more debris, which creates more collisions. This is called Kessler syndrome, and it's a genuine existential threat to space operations.

Spectrum Allocation: Radio frequencies are finite and internationally regulated. The ITU (International Telecommunication Union) allocates spectrum. Adding a million satellites requires spectrum that might be allocated to other users or nations.

Light Pollution: Satellites are already interfering with astronomical observations. Dark sky advocates hate them. One million satellites would make stargazing from Earth essentially impossible. Observatories worldwide would be impacted.

International Relations: Launching a million satellites that provide AI computing capacity could be seen as a strategic advantage. Other nations might seek their own constellations. This could accelerate a space arms race.

Deorbiting Plans: How do you safely deorbit a million satellites at end-of-life? One million satellites means one million potential debris sources if deorbiting fails. The liability is staggering.

The FCC will likely approve a phased approach. Maybe 10,000 satellites as a pilot. Then evaluation. Then more, conditionally. The full one million request will probably be used as a negotiating anchor, not a realistic first step.

Competing Infrastructure: Amazon, Blue Origin, and the Satellite Race

Space X isn't alone. This is becoming an infrastructure arms race.

Amazon is pursuing its own satellite internet constellation called Kuiper. The company requested FCC approval for 3,236 satellites. As of 2025, Amazon is behind schedule, citing a lack of available launch vehicles. Space X's Starship is one option, but Space X isn't necessarily eager to launch a competitor's satellites.

Blue Origin (another Bezos company) is developing New Glenn, a heavy-lift rocket intended to compete with Starship. But New Glenn development has faced delays.

One Web, partially backed by the UK government, operates about 600 satellites for internet service.

Large constellations are becoming strategic infrastructure, similar to undersea fiber optic cables. Nations are paying attention. The US sees these as competitive advantages. China is developing similar capabilities. India is planning its own satellite internet service.

The AI computing angle is new, though. Putting data centers in orbit specifically to power AI training and inference is a next-level move. It's not just about internet. It's about computational sovereignty.

If Space X successfully deploys orbital AI data centers, it could give the company (and by extension, US technology companies using those data centers) an enormous competitive advantage. Lower energy costs. Unlimited scalability. Cleaner power source.

Competitors would be forced to respond. This could accelerate the space infrastructure arms race significantly.

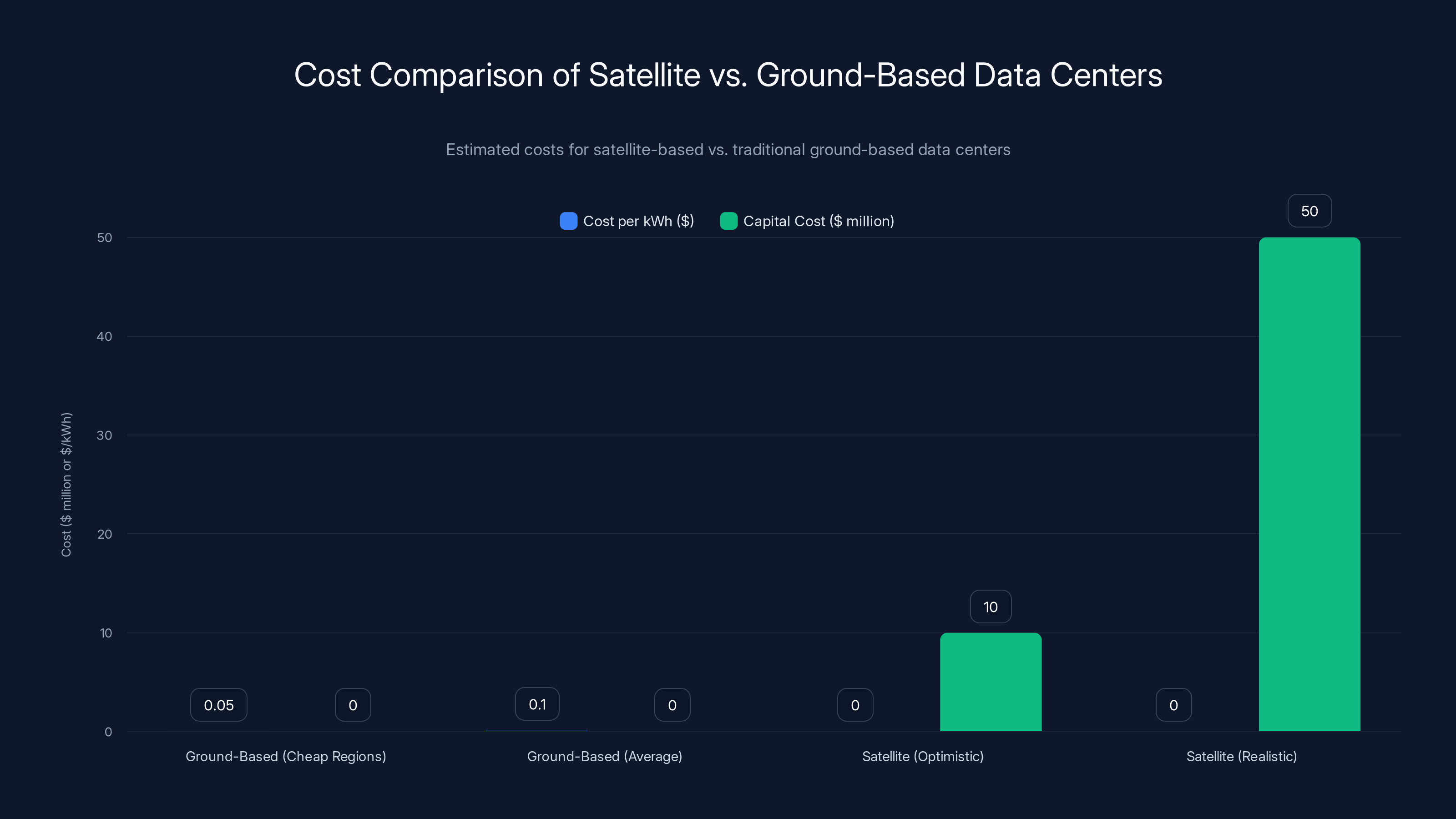

Satellite data centers have negligible marginal electricity costs but significantly higher capital costs compared to ground-based centers, especially in regions with cheap electricity. Estimated data.

Energy Economics: Do the Numbers Actually Work?

Let's do some math to see if this makes sense financially.

A single kilowatt-hour of electricity costs roughly

Orbitally harvested solar energy? Once the infrastructure is in place, the marginal cost of electricity is essentially zero. Just maintenance and replacement.

But the capital costs are astronomical.

A modern telecom satellite costs

Let's assume Space X achieves cost reductions and brings per-satellite cost to

That's more than the entire US federal budget. It's larger than the global GDP of all but four countries.

For context, the entire global space industry revenue is roughly $400-500 billion annually. Building this constellation would require ramping space manufacturing and launch cadence by 100-200 times current levels.

Space X could probably achieve some of this. If Starship reaches the claimed

So total per-satellite cost drops to maybe

The ROI breaks down if you're competing against ground-based data centers in regions with cheap electricity. But if you're positioning this as a strategic global asset that no single nation or power grid can threaten, the economics might work at a civilizational level.

If Space X positions these as data centers for national governments or alliances, the calculus changes. Geopolitical advantage might justify costs that financial ROI wouldn't.

Space Debris and the Kessler Syndrome Risk

Here's the scary part: if this goes wrong, it goes catastrophically wrong.

Kessler syndrome is a runaway cascade of collisions. One satellite collides with debris, creating more debris, causing more collisions, creating more debris, exponentially. Once started, it's nearly unstoppable.

The threshold is estimated at roughly 40,000 massive objects in low Earth orbit (below 2,000 kilometers altitude). We're currently around 34,000 pieces of tracked debris larger than 10 centimeters.

One million new satellites significantly increases collision probability. Each new satellite is a potential collision initiator.

Historically:

- In 2009, an Iridium communications satellite collided with a defunct Russian satellite, creating 2,000+ pieces of trackable debris.

- In 2021, a Chinese anti-satellite test created over 3,500 trackable pieces.

- Every day, roughly 30-40 collision warnings are issued to satellite operators in low Earth orbit.

Adding a million satellites means millions of potential collision scenarios. Even if the probability per satellite is 1-in-10,000 annually (very optimistic), you'd expect 100 collisions per year. Each creating hundreds or thousands of new debris pieces.

The space debris problem requires active management. Deorbiting satellites at end-of-life. Designing satellites for controlled reentry. Installing propulsion systems for collision avoidance. These add cost and complexity.

Space X has committed to deorbiting Starlink satellites within 5 years of end-of-life. If they commit to the same standard for one million AI data center satellites, it's feasible but requires perfect execution across 50+ years of launches.

One failed deorbiting event creates thousands of debris pieces that could trigger cascades. This is a genuine risk.

The FCC is expected to approve satellite deployments in phases, starting with a pilot of 5,000-10,000 satellites by 2026-2027. Full deployment of one million satellites is unlikely before 2050. Estimated data based on current projections.

The Light Pollution Problem: How This Affects Astronomy

Starting in 2020, professional astronomers noticed something alarming. Starlink satellites were ruining observations.

Satellites are bright. They're in direct sunlight when Earth-based observatories are in darkness. They reflect sunlight like mirrors. Modern astronomical imaging is sensitive enough to detect individual satellites crossing fields of view.

For ground-based astronomy, this is catastrophic. A single satellite can ruin an exposure. Twelve-hour observing runs can be compromised. Pattern recognition algorithms (critical for detecting asteroids, gravitational lensing, and other phenomena) get confused by satellite tracks.

With 6,000 Starlink satellites, the problem is already severe. Astronomical organizations worldwide have issued complaints.

One million satellites? Essentially every observation from Earth would be contaminated. The night sky becomes unusable for astronomy.

Space X has proposed mitigation: lowering satellite brightness through special coatings and designs. Visor shields. Special paint. These help but don't solve the problem entirely.

For one million satellites, even if 99% mitigation is achieved, 10,000 could still be visible and problematic at any given time.

The cultural impact is worth considering. Humans have observed the night sky for millennia. Ancient navigation, calendars, mythology, spiritual significance—all connected to the stars. One million reflecting satellites change that forever.

This alone might prevent FCC approval, or severely limit constellation size.

Alternative Computing Models: Why Ground-Based Alternatives Persist

Before accepting space-based AI data centers as inevitable, consider why ground-based infrastructure still dominates.

Reliability: Data centers on Earth can be easily serviced, upgraded, and repaired. A satellite with a component failure? It stays broken or requires a costly service mission.

Latency: 250+ milliseconds of round-trip latency is acceptable for training. But for inference, it's problematic. Most AI applications require sub-100 millisecond response times. Orbital data centers have fundamental physical limits.

Ease of Scaling: Adding computing power on Earth means building another data center. It's expensive but straightforward. Orbital deployment requires coordinated launches, orbital mechanics, frequency allocations, and international approvals.

Regulatory Complexity: Ground-based infrastructure faces fewer regulatory hurdles. You build on land you own, connect to the grid, and operate. Orbital infrastructure requires international coordination.

Thermal Management: Cooled data centers use the same kilowatts they consume in processing (roughly). Orbital radiators have size constraints that make massive computing power challenging.

Ground-based alternatives are improving:

- Geothermal data centers: Iceland, Kenya, and New Zealand are building facilities powered by geothermal energy. Costs are already lower than coal or natural gas.

- Hydroelectric expansion: Countries with hydroelectric capacity are building data centers nearby. Canada's Quebec region is becoming a data center hub due to cheap hydroelectric power.

- Nuclear fission: Small modular reactors (SMRs) are being deployed for industrial power. Google signed a deal for SMR power for data centers. Microsoft is exploring the same. Microsoft's blog discusses their commitment to sustainable AI infrastructure.

- Nuclear fusion: Fusion power plants remain hypothetical but could provide unlimited clean energy within 10-20 years (optimistic timeline).

- Wind power: Massive wind farms in plains and coastal regions are increasingly cost-competitive.

For AI computing specifically, ground-based renewable energy is competitive with orbital solar power once infrastructure is considered. And it's available now, not in 10+ years.

Space X's proposal isn't about necessity. It's about competitive advantage and long-term strategic positioning.

The Geopolitical Dimension: AI Computing as Infrastructure Power

Here's where this gets genuinely interesting from a strategic perspective.

Computational resources are increasingly central to national power. The US currently dominates AI development because:

- Access to cheap energy (abundant natural gas, hydroelectric capacity).

- Availability of advanced semiconductors (primarily from TSMC in Taiwan, a US ally).

- Capital to build massive data center infrastructure.

China is investing billions to reduce dependence on US chips and build domestic AI capabilities. The EU is developing regulatory frameworks around AI (potentially limiting competitive advantage). Other nations are playing catch-up.

Orbital AI data centers could shift this balance.

A company or nation that achieves orbital solar power for computation gains:

- Energy independence: No reliance on terrestrial grids or political allies for power.

- Geopolitical leverage: Computational capacity is power. Controlling orbital data center access means controlling AI development.

- Strategic depth: Orbital infrastructure is harder to destroy or regulate than terrestrial facilities.

This is why Space X's proposal matters geopolitically. It's not just about serving customers. It's about repositioning space-based infrastructure as critical national assets.

The US government is probably aware of this. Which means FCC approval, even if phased and limited, is likely. Because allowing a competitor to build this first would be strategically disadvantageous.

China will probably pursue similar capabilities. India might. The EU could. This accelerates a space infrastructure arms race.

What FCC Approval Actually Looks Like

Full approval for one million satellites in a single authorization is essentially zero percent probability.

What's likely instead:

Phase 1 (Most Probable): FCC approves 5,000-10,000 satellites as a pilot. Conditional on Space X demonstrating debris mitigation, light pollution controls, and successful operations of existing constellation.

Phase 2 (Probable): After 2-3 years of successful operations, FCC considers approving another batch. Maybe 20,000-50,000. With new conditions for thermal management, interference mitigation, and international coordination.

Phase 3 (Speculative): Subsequent tranches up to 100,000-200,000, with additional conditions and review periods.

Full Million (Unlikely in Current Form): Would require either massive changes in technology (efficient deorbiting systems, dramatically reduced size/cost, completely solved light pollution) or geopolitical circumstances (existential space threat, loss of Earth-based infrastructure).

The FCC will use approval as a regulatory lever. Each phase gets conditional approval tied to performance metrics. This maximizes their control.

International coordination also matters. The ITU would need to allocate spectrum. Other space-faring nations would likely seek reciprocal agreements. Bilateral negotiations between the US and China/Russia/EU would influence timelines.

Realistic timeline: First phase approval by 2026-2027. First operational satellites by 2028-2030. Scale to 100,000 by 2035-2040. Full million by 2050+ (if ever).

Economic Implications for Cloud Computing and Energy Markets

If orbital data centers actually deployed at scale, the energy cost structure of computing changes fundamentally.

Currently, cloud computing providers (AWS, Azure, Google Cloud) pay roughly $0.05-0.15 per kilowatt-hour for electricity. This is a significant operational cost. Data center electricity consumption is the limiting factor for expansion.

With orbital solar power priced at marginal cost (near zero), pricing could collapse. Compute-intensive tasks become almost free on a marginal basis.

This would cause a wave of new AI applications that aren't currently economically viable. Real-time high-resolution video analysis. Continuous environmental monitoring. Personalized AI assistance for billions of users simultaneously. Computationally intensive simulations that currently cost too much to run.

Electricity providers and traditional cloud operators face disruption. Renewable energy providers (wind, solar, hydroelectric) would see demand pressure from new low-cost orbital competitors.

National energy grids might become less critical. Some computing shifts to orbital infrastructure, reducing terrestrial electricity demand growth. This could be positive for climate (less grid expansion needed) but negative for utility companies' revenue.

Equity markets would react sharply. Energy companies might decline. Tech companies that can negotiate orbital data center access would gain competitive advantages. Space X's valuation would skyrocket if this succeeds.

Long-term, this could reshape where computation happens and how expensive it is to do so.

The Skeptic's Case: Why This Might Never Happen

Let's be honest about the headwinds.

Technological Challenges: Orbital data centers facing radiation, thermal constraints, and latency issues are harder than ground-based alternatives. Solving these requires breakthroughs that might not materialize.

Cost Reality: $2-10 trillion is nearly impossible to finance. Even Space X with backing can't sustain this pace without massive government contracts or international partnerships.

Political Resistance: Light pollution complaints from astronomers. Debris concerns from NASA and ESA. Spectrum allocation disputes. Cybersecurity questions. Any of these can stall approvals indefinitely.

Better Alternatives Emerging: Fusion power. Advanced geothermal. Next-generation solar efficiency. By the time orbital data centers are operational, ground-based solutions might be just as cheap and far simpler.

Latency Limits: For most AI applications, latency matters. Orbital computing introduces 250+ milliseconds of delay inherently. If AI workloads require sub-100ms response, orbital computing is fundamentally limited to training and batch processing, not inference serving.

Technical Obsolescence: A million satellites launched over 10-15 years means the oldest ones are obsolete by the time the newest ones arrive. Constant replacement and upgrade cycles are required.

It's entirely possible Space X uses this FCC filing as leverage for regulatory approvals and negotiating position, without genuinely intending to build a million satellites. It's happened before. Companies ask for 10x what they actually need, knowing they'll get 1-2x approved.

A Realistic Vision of the Next 10 Years

Here's what's probably actually coming:

2026-2027: FCC approves first phase (5,000-10,000 satellites). Space X begins manufacturing and deploying.

2028-2030: First generation operational. Ground stations built. Early customers (likely US government agencies and major tech companies) begin testing.

2030-2035: Proof of concept succeeds. FCC approves larger constellation (50,000+). Competition emerges (Blue Origin, Amazon, possibly Chinese programs).

2035-2045: Multiple operators managing orbital infrastructure. Specialized satellites for different functions (government computing, commercial cloud services, AI-specific). Debris mitigation becomes standard practice.

2045+: Either orbital computing becomes standard infrastructure (alongside terrestrial systems) or the technological advantages diminish as ground-based alternatives improve.

The most likely outcome is neither utopian (unlimited clean computing power for humanity) nor dystopian (Kessler syndrome destroys orbital access). It's pragmatic: a niche capability that works for specific use cases where latency isn't critical and capital availability isn't constrained.

Government agencies. National defense. Massive training runs by trillion-dollar tech companies. Those are the early customers.

For routine commercial use, ground-based data centers will probably remain dominant through 2050+. They're simpler, lower latency, easier to manage.

FAQ

What exactly is Space X proposing with these satellite data centers?

Space X filed an FCC request to deploy up to one million solar-powered satellites in orbit that would function as distributed data centers for artificial intelligence computing. Unlike Starlink satellites designed for internet connectivity, these would be optimized for computational power, continuously powered by solar energy, and capable of processing AI training and inference workloads at scale. The filing positioned this as a foundational step toward becoming a Type II Kardashev civilization capable of harnessing the sun's total energy output.

Why would orbiting data centers be better than ground-based facilities?

Orbital solar panels receive 36% more consistent power than Earth-based panels because there's no atmospheric interference, cloud cover, or day-night cycle. Once infrastructure is deployed, the marginal cost of electricity is essentially zero, since the sun continuously delivers free power. This solves the massive energy consumption problem facing AI companies, where training large models requires enormous quantities of electricity. However, orbital computing faces challenges like latency (250+ milliseconds round-trip) and thermal management that ground-based alternatives don't have, which limits applicability to specific use cases like batch processing and model training rather than real-time inference.

How likely is the FCC to approve one million satellites?

Outright approval for a full one million satellites is extremely unlikely. The FCC will probably use a phased approval approach, similar to how Starlink was authorized incrementally. Expect initial approval for 5,000-10,000 satellites as a pilot, followed by conditional approvals for larger tranches contingent on Space X demonstrating successful debris mitigation, light pollution controls, and operational safety. Full deployment to one million would realistically take 25-50 years if it happens at all, pending technology improvements and resolution of orbital debris concerns.

What's the space debris problem with adding a million satellites?

Orbital debris is already a critical issue. Currently, there are roughly 34,000 tracked debris pieces larger than 10 centimeters and millions of smaller fragments. Adding a million satellites increases collision probability exponentially. Each collision creates more debris, potentially triggering Kessler syndrome, a cascading effect where collisions spawn debris that causes more collisions. One failed satellite deorbiting creates thousands of debris pieces. Managing end-of-life disposal for one million satellites requires perfect execution across decades. A single major collision event could render certain orbital altitudes unusable, threatening existing satellites and future space operations.

How would orbital data center economics compare to ground-based facilities?

Capital costs favor ground-based data centers significantly. Launching and maintaining one million satellites would cost

Would this interfere with astronomy and stargazing?

Severely. Even Starlink's 6,000 satellites are already ruining professional astronomical observations and making dark sky observing difficult. One million satellites would essentially make Earth-based astronomy impossible. Every field of view would contain visible satellites. Mitigation technologies like special coatings and visor shields help but don't eliminate the problem. This is a major regulatory and cultural objection that could significantly constrain FCC approvals, since the US has major observatories and astronomical institutions with political influence.

What are Space X's competing advantages in executing this?

Space X has several advantages: Starship's reusable rocket architecture could dramatically reduce launch costs. Manufacturing capability and supply chain experience from Starlink. Regulatory relationships with the FCC from years of Starlink negotiations. Engineering expertise with large satellite constellations. Capital access through Elon Musk's wealth and the company's valuation. However, they still face immense technical challenges in satellite thermal management, radiation hardening, and debris mitigation that haven't been fully solved for this scale of deployment.

Could other countries or companies build competing orbital data centers?

Absolutely. China is likely developing similar capabilities. Blue Origin and Amazon might compete through Project Kuiper. The EU could pursue its own constellation. Success by any player would likely trigger competitors to follow. This could accelerate a space infrastructure arms race with significant geopolitical implications, as nations vie for computational advantage and orbital control. International spectrum allocation through the ITU could become a major negotiation point between superpowers.

How does latency affect the practicality of orbital computing?

Orbital satellites at geostationary altitude (roughly 36,000 kilometers) introduce 250+ milliseconds of round-trip latency due to signal travel time alone. This makes real-time AI inference serving impractical for most applications requiring sub-100ms response times. Orbital data centers would be limited to batch processing, model training, and non-latency-sensitive workloads. Ground-based data centers at 1-5 milliseconds latency are far superior for serving live AI features to billions of users. This fundamentally constrains orbital computing's applicability to specific high-capacity, latency-tolerant tasks rather than general-purpose cloud computing.

What's the timeline for actual orbital AI data center deployment?

Optimistic estimate: Initial phase approval by 2026-2027, first operational satellites by 2028-2030. More realistic: Pilot constellation of 10,000-50,000 satellites by early 2030s, with ongoing expansion contingent on technical success and regulatory approval. Full one million satellites (if it happens) likely beyond 2050. Between now and then, ground-based alternatives like geothermal, hydroelectric, and fusion power could mature, potentially making orbital computing less economically necessary. The pace depends heavily on regulatory decisions, technological breakthroughs, and whether Space X can finance operations without government contracts.

The future of AI computing might be written in the sky. Whether that's actually practical or just audacious vision depends on engineering, economics, and whether Space X can convince regulators that a million satellites orbiting Earth is worth the risks.

Key Takeaways

- SpaceX filed for FCC approval to deploy up to one million solar-powered satellites functioning as distributed AI data centers in orbit, representing a radical approach to solving the energy consumption crisis in AI computing.

- Orbital solar power receives 36% more consistent energy than ground-based systems due to no atmospheric interference or day-night cycles, but faces challenges in thermal management, latency (250+ ms), and capital costs ($2-10 trillion for full deployment).

- FCC will likely approve a phased deployment starting with 5,000-10,000 satellites as a pilot, with conditional approval for larger tranches over decades, making full one million deployment unlikely before 2050 if it happens at all.

- Space debris risk is substantial, with collision probability increasing exponentially—failed deorbiting of a single satellite creates thousands of debris pieces potentially triggering Kessler syndrome and rendering orbital altitudes unusable.

- Light pollution from one million reflective satellites would eliminate ground-based astronomy worldwide, creating regulatory and cultural obstacles that could significantly constrain FCC approvals despite technical feasibility.

Related Articles

- SpaceX's Million Satellite Data Centers: The Future of Cloud Computing [2025]

- SpaceX's Million-Satellite Orbital Data Center: Reshaping AI Infrastructure [2025]

- SpaceX and xAI Merger: What It Means for AI and Space [2025]

- Microsoft's $7.6B OpenAI Windfall: Inside the AI Partnership [2025]

- NVIDIA's $100B OpenAI Investment: What the Deal Really Means [2025]

- NASA Used Claude to Plot Perseverance's Mars Route [2025]

![SpaceX's 1 Million Satellite Data Centers: The Future of AI Computing [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/spacex-s-1-million-satellite-data-centers-the-future-of-ai-c/image-1-1769895357356.jpg)