Microsoft's Strange Email Routing Mishap: What Happened to example.com [2025]

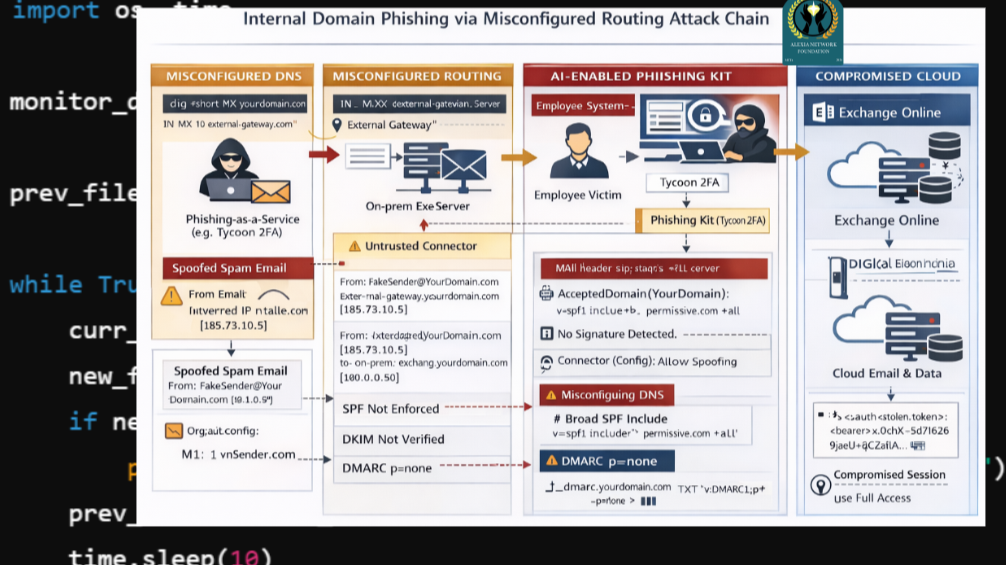

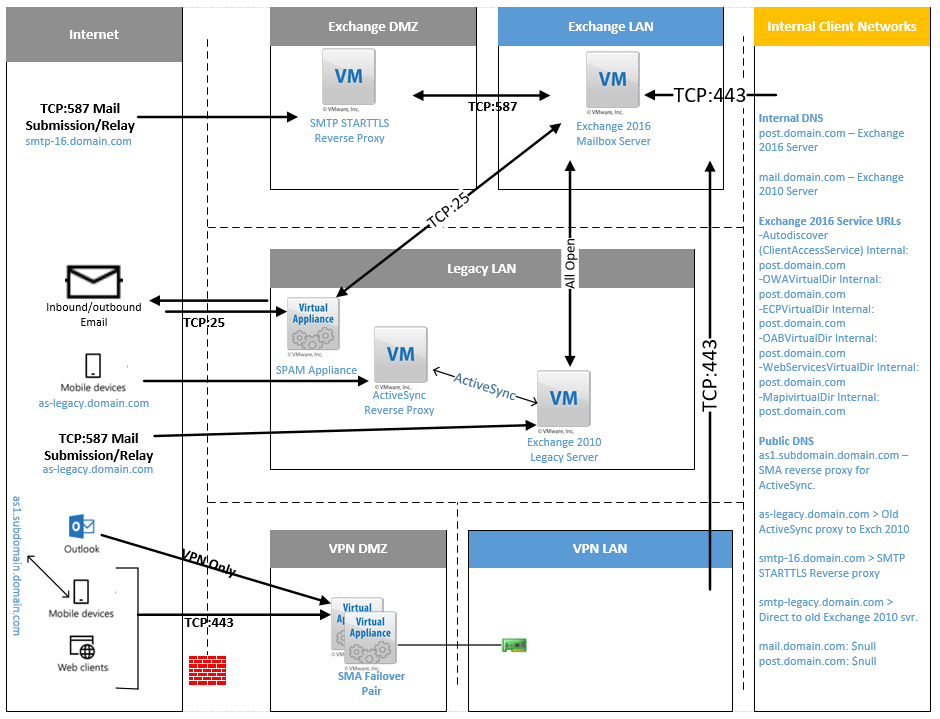

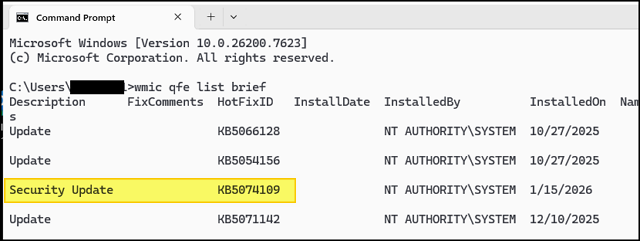

In January 2026, network researchers stumbled upon something bizarre buried inside Microsoft's infrastructure. Test email traffic—the kind that should never reach any real server—was being routed to an obscure Japanese manufacturing company. For years, nobody inside Microsoft could explain why.

This wasn't a hack. It wasn't espionage. It was something almost worse in the world of tech infrastructure: a configuration mistake so fundamental that it persisted across multiple product teams, multiple service updates, and thousands of engineers who presumably walked past it without noticing.

The incident reveals uncomfortable truths about how even the largest technology companies maintain their global infrastructure. It's a story about automation, testing standards that exist on paper but not in practice, and the massive blind spots that hide in plain sight when nobody's specifically looking for them.

Let's walk through what happened, why it happened, and why it matters for infrastructure security more broadly.

TL; DR

- The incident: Microsoft's Outlook autodiscover service returned mail server hostnames pointing to a Japanese company (Sumitomo Electric) when testing with example.com, a reserved domain

- The scope: The issue persisted for several years and affected test infrastructure across multiple Microsoft services

- The root cause: A domain configuration error embedded in autodiscover systems that should have been caught by automated safeguards

- The response: Microsoft disabled the anomalous routing in January 2026 but provided minimal technical explanation

- The lesson: Even massive enterprises miss basic infrastructure hygiene because nobody owns the responsibility to check

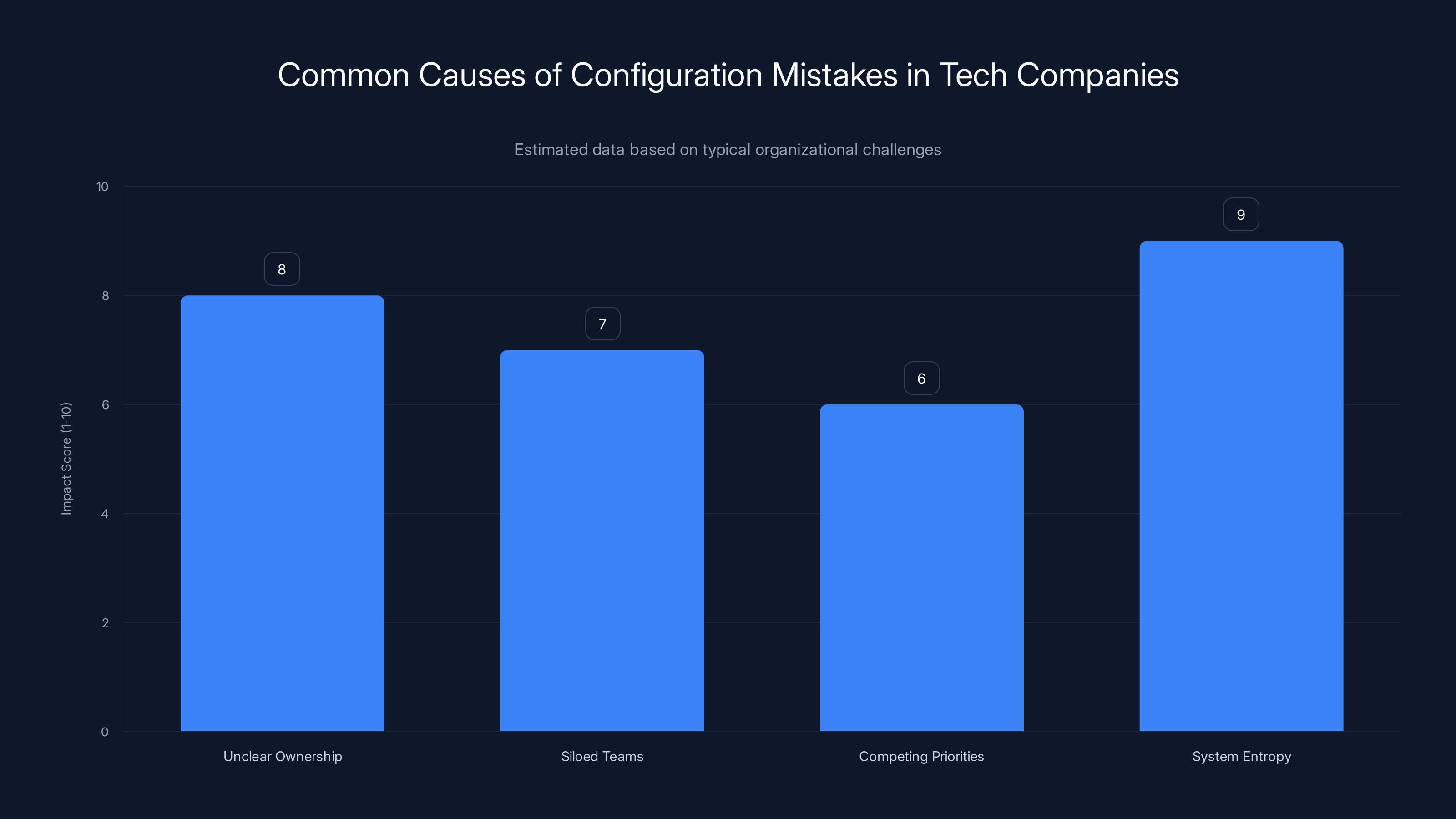

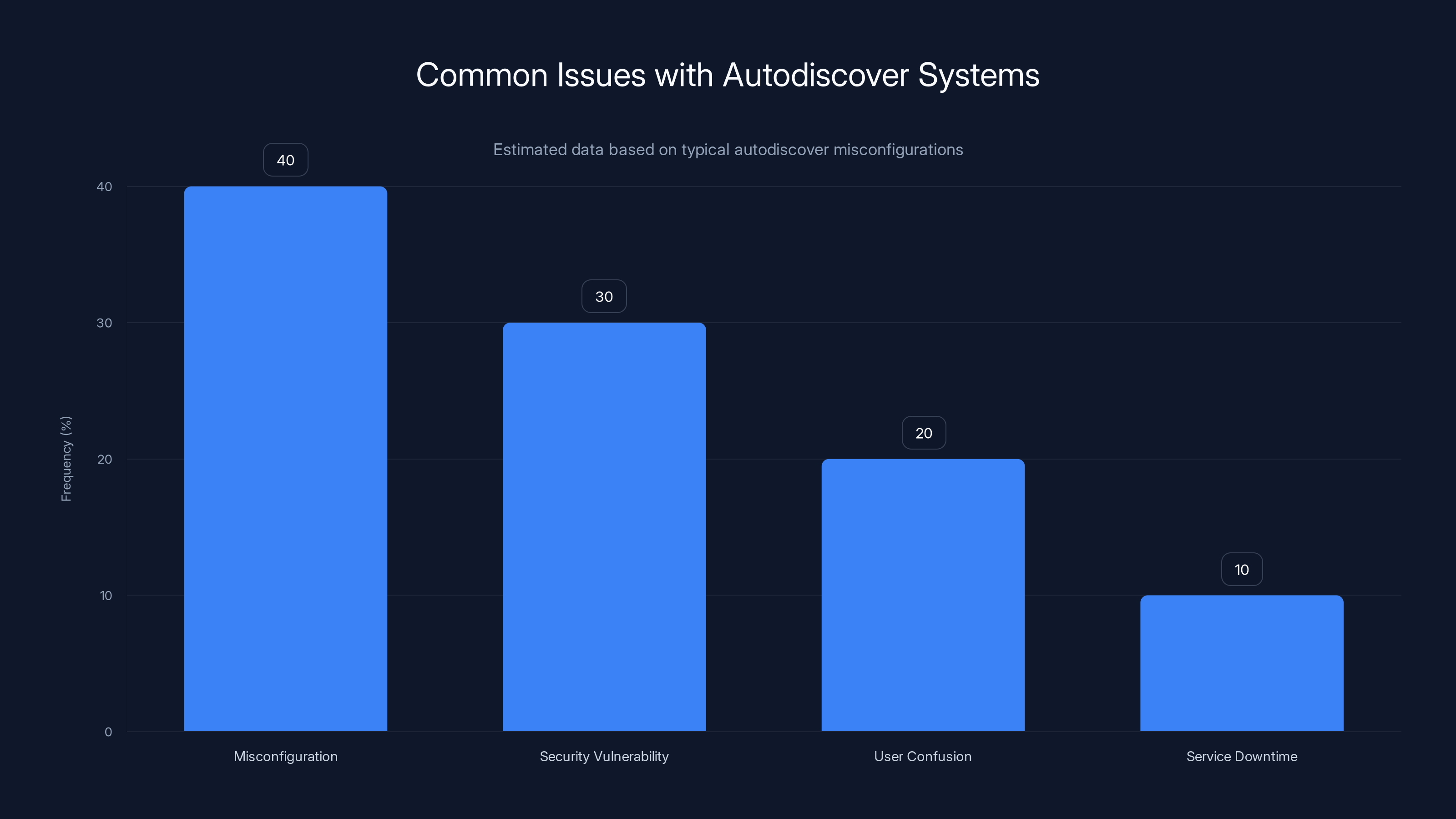

Organizational issues like unclear ownership and system entropy are major contributors to configuration mistakes, even in large tech companies. Estimated data.

What Is example.com, and Why Does It Matter?

Before we get into the weeds of this incident, you need to understand something fundamental: example.com isn't just any domain. It's a protected domain, defined by RFC 2606, specifically reserved for documentation and testing.

The internet engineering community set aside four domains for this exact purpose: example.com, example.org, example.net, and example.edu. They're the digital equivalent of test kitchen space in a restaurant. Everyone knows they're fake. Nobody expects them to resolve to actual services. They exist so developers can write documentation, build test cases, and run experiments without accidentally hitting real infrastructure.

Here's the critical part: by design, these domains should never generate routable service information in any production system. A web server responding to example.com makes sense. But your email client fetching mail server hostnames for example.com and getting back actual, working IMAP and SMTP endpoints? That shouldn't happen. That violates the fundamental contract of what reserved domains are supposed to do.

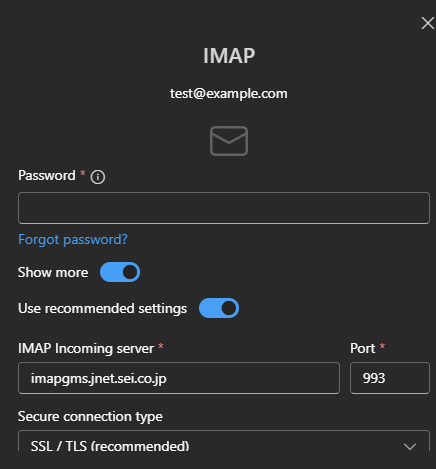

Microsoft's Outlook autodiscover system broke that contract. When researchers submitted test credentials using example.com, the service returned legitimate mail server information pointing to sei.co.jp, a domain registered to Sumitomo Electric, a Japanese company known for industrial cables and semiconductor components.

The fact that this happened at all suggests that somewhere in Microsoft's codebase, a configuration file included hardcoded domain mappings. Or perhaps the autodiscover logic itself was flawed, pulling from a database that contained entries it shouldn't.

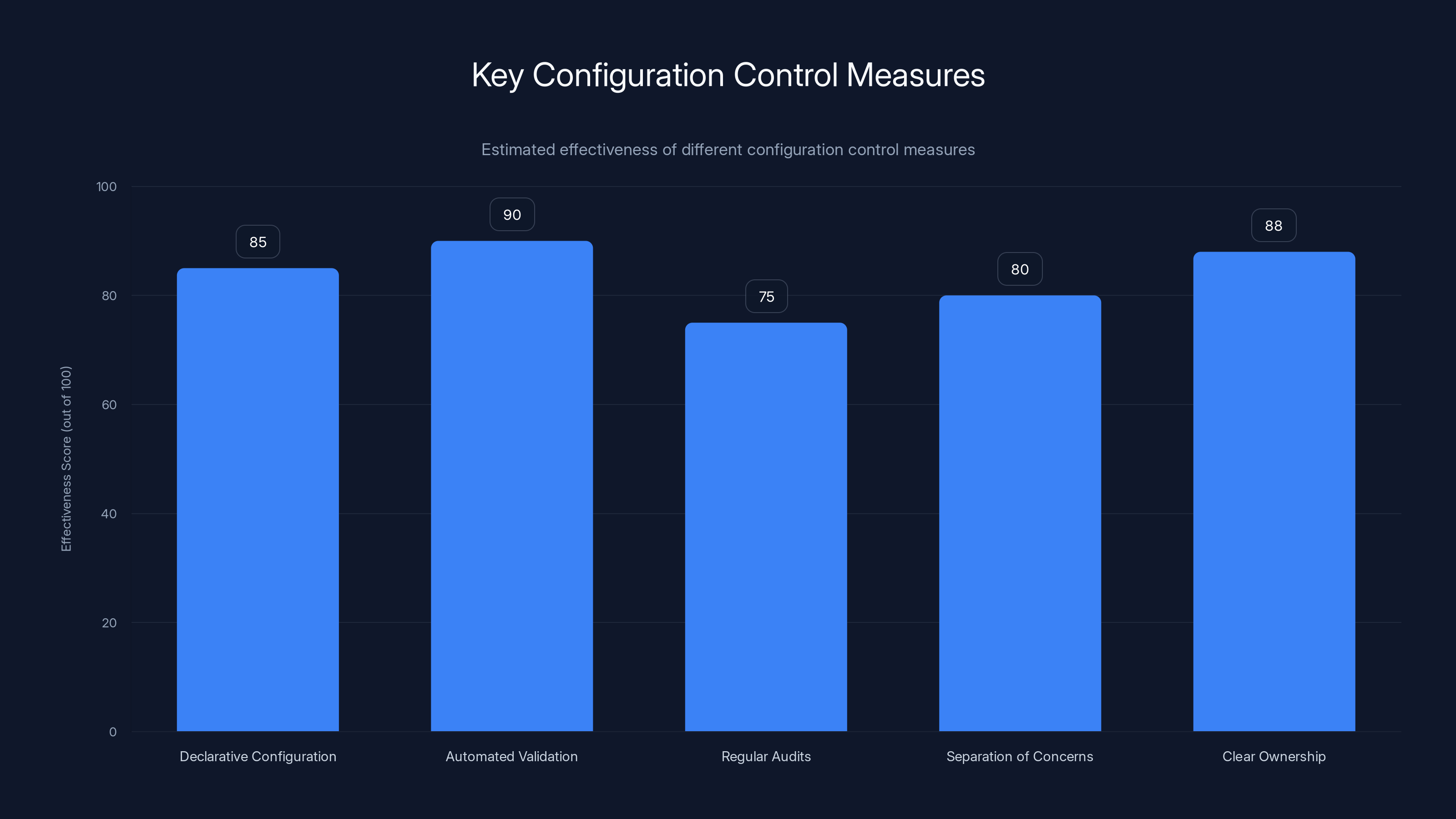

Automated validation is estimated to be the most effective measure for preventing configuration issues at scale, followed closely by clear ownership of the configuration database. (Estimated data)

The Autodiscover System and How It Works

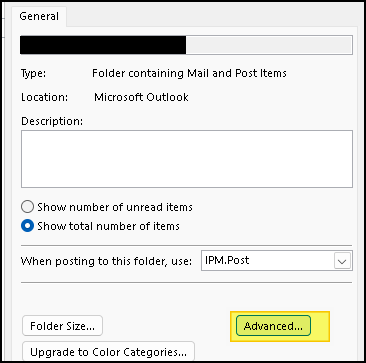

Understanding why this matters requires understanding Microsoft's Outlook autodiscover feature. It's actually quite elegant in concept, even if the execution here was flawed.

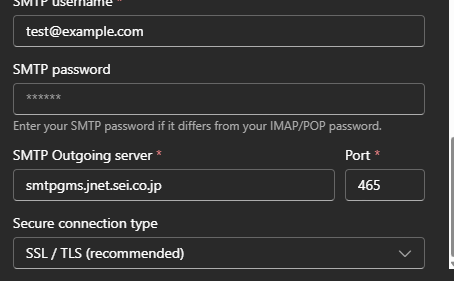

When you set up a new email account in Outlook, the client doesn't ask you for technical details. You provide an email address and password. That's it. Autodiscover then takes over, communicating with your email provider's servers to figure out what mail server to connect to, what protocol to use (IMAP, SMTP, Exchange Web Services), and what authentication method to employ.

This is genuinely convenient. Users don't need to know that their mail server is imap.company.com or smtp.company.com. The autodiscover system finds it automatically.

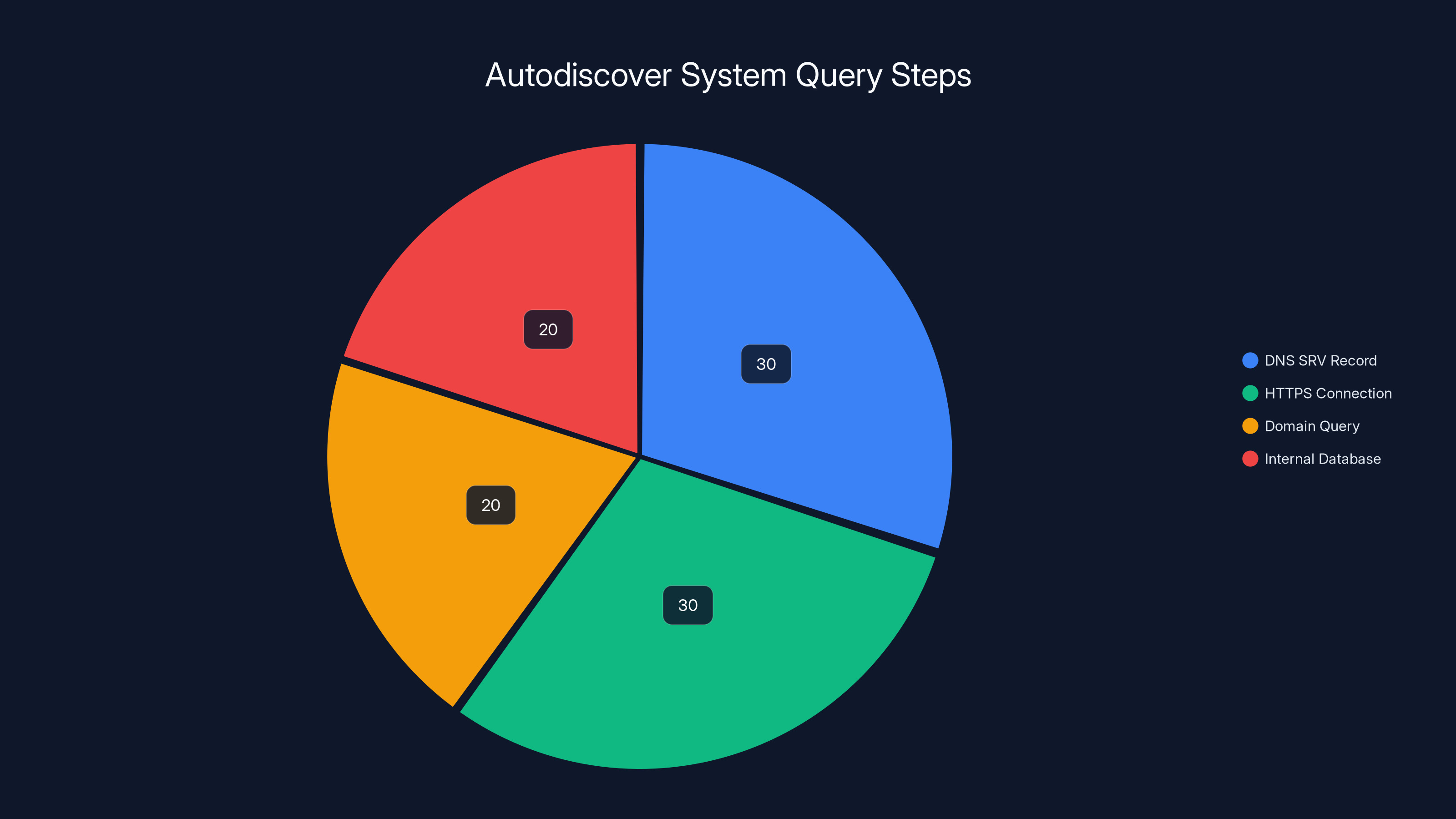

But here's the vulnerability hiding inside that convenience: autodiscover makes assumptions about domain structure. When you provide an email address like user@example.com, autodiscover typically:

- Checks for a DNS SRV record pointing to the mail server

- Attempts an HTTPS connection to autodiscover.example.com

- Falls back to querying the domain itself

- In some cases, checks internal configuration databases for known domain mappings

At some point in this chain, Microsoft's system was checking an internal database. And that database contained an entry mapping example.com (or perhaps a wildcard pattern matching it) to servers at sei.co.jp.

What's almost comical about this is that sei.co.jp is legitimately a Sumitomo Electric domain. This wasn't random data corruption. Someone, at some point, deliberately added this mapping to the system. The mystery is who, when, and why.

The Technical Anomaly: JSON Responses That Shouldn't Exist

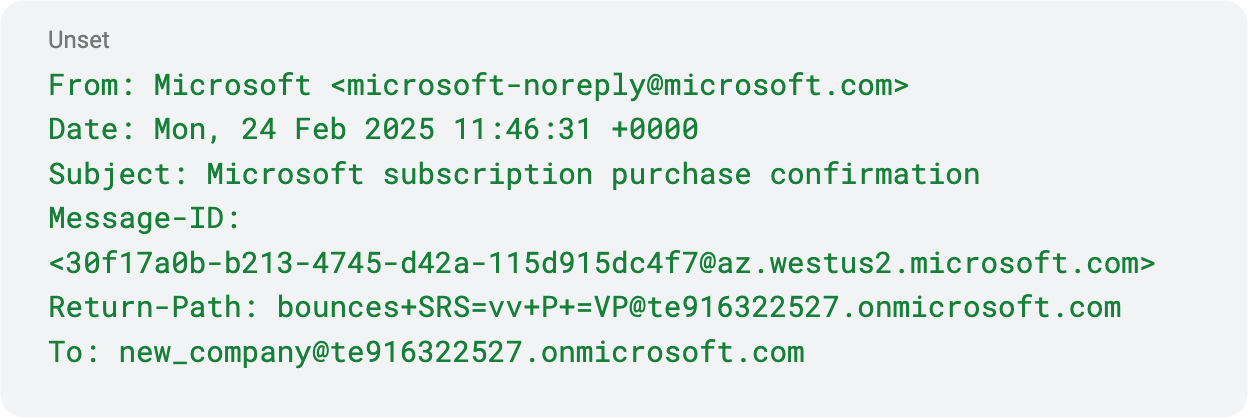

When researchers tested the autodiscover endpoint with example.com credentials, they received JSON responses containing mail server hostnames. This is where the incident becomes technically interesting because those responses shouldn't have been generated at all.

Autodicover can respond in multiple formats depending on the client and the situation. For Exchange clients, it typically returns XML. For mobile clients, it might return JSON. In either case, the response includes mailbox server addresses, protocol information, and authentication details.

The researchers' test requests returned something like:

json{

"autodiscover": {

"response": {

"user": {

"action": "settings",

"email Address": "test@example.com",

"display Name": "Test User"

},

"account": {

"account Type": "email",

"action": "settings",

"protocol": [

{

"type": "IMAP",

"server": "imap.sei.co.jp",

"port": "993",

"login Name": "test@example.com"

},

{

"type": "SMTP",

"server": "smtp.sei.co.jp",

"port": "587"

}

]

}

}

}

}

These aren't placeholder responses. These are properly formatted, valid server configurations pointing to actual machines. An Outlook client would accept this response and attempt to connect to those servers.

This is fundamentally different from a DNS misresolution or a BGP hijack, where legitimate traffic gets misdirected due to routing errors. This is an application-level service deliberately returning server information for a domain it shouldn't know about.

The fact that the response included properly formatted IMAP and SMTP endpoints suggests this wasn't random corruption. The system was working as designed—just pointing to the wrong server. The question is: how did the mapping get there, and more importantly, why wasn't it caught?

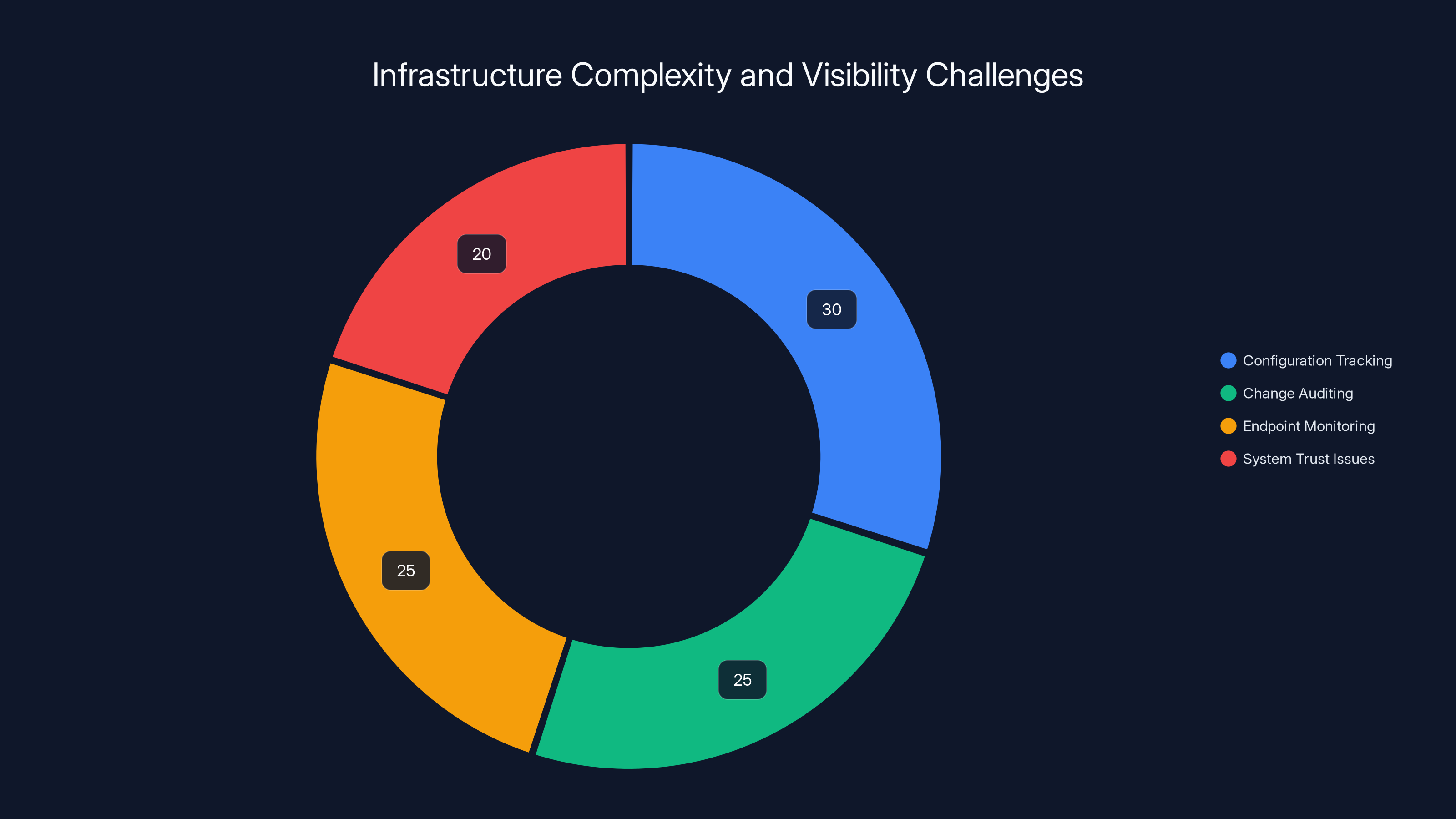

Estimated data shows that configuration tracking and change auditing are major challenges in large-scale infrastructure management, each accounting for around 25-30% of the issues.

Why This Should Have Been Caught: The Safeguards That Failed

Microsoft's infrastructure, like most major cloud providers', has multiple layers of safeguards specifically designed to catch this kind of mistake. The fact that this persisted suggests those safeguards failed across the board.

First, there should be automated validation that checks for reserved domain references in configuration files. RFC 2606 domains should trigger alerts if they appear in production systems. This is simple to implement: scan all configuration databases for patterns matching example.com, example.org, test.com, localhost, or other reserved ranges.

Microsoft almost certainly has such tooling. So either it wasn't running on the system containing this mapping, or its alerts were ignored.

Second, code reviews and change logs should document when domain mappings are added to autodiscover databases. This isn't some obscure corner of the codebase—this is a critical service touched by hundreds of engineers. Any change to production domain mappings should go through multiple levels of approval.

The fact that someone added sei.co.jp to the autodiscover database without a paper trail suggests either:

- The database wasn't under proper version control

- Changes weren't logged

- Logs existed but weren't being audited

- The change was made through an informal process that bypassed normal controls

Third, automated testing of the autodiscover endpoint should include tests that verify it returns errors (not valid server information) for reserved domains. This is a basic test any QA team would write. If it existed, it would have caught this immediately. If it didn't exist, that's a significant gap in test coverage.

Fourth, there are passive monitoring systems that would detect this. If the autodiscover endpoint suddenly started returning valid server information for example.com, monitoring would show a change in behavior. Either these systems weren't monitoring this particular endpoint, or alerts were firing and being ignored.

The picture that emerges is one of multiple independent safeguards all failing simultaneously. Not because they don't exist, but because they exist in isolation, without someone dedicated to making sure they all work together.

The Duration: Years of Undetected Misconfiguration

One of the most unsettling aspects of this incident is that it apparently persisted for several years. This wasn't a recent mistake caught after a few weeks. Security researchers found it in January 2026, but the misconfiguration likely existed years before that.

How does something this visible remain hidden for so long?

Partially, it's because nobody was looking for it. Autodiscover endpoints aren't commonly probed or tested by outside researchers. The endpoint requires specific knowledge to query correctly. If you're not specifically testing email client behavior, you might never interact with autodiscover.

Internally at Microsoft, the answer is more sobering. Example.com traffic might be used for legitimate testing purposes. Developers testing email client behavior might use example.com credentials intentionally. So when the system started returning server information for example.com, it might have appeared to be working as designed.

Here's the scenario: A developer, or a team, decides to test autodiscover with example.com. They manually add a mapping to point to test servers. That works. The feature gets tested. The mapping gets left in place because "we might need it again." Months pass. Teams change. Documentation gets lost. Eventually, the original mapping migrates into production configuration because nobody realizes it shouldn't be there.

This kind of configuration drift is almost inevitable at massive scale. Microsoft runs thousands of services, manages millions of configuration entries, and employs tens of thousands of engineers. Individual engineers make good decisions within their context. But when those decisions aren't coordinated, when there's no global policy enforcement, things slip through.

The fact that it persisted for years also suggests that real user traffic wasn't being affected—or if it was, users weren't complaining. If someone had tried to set up an email account using example.com (not a realistic scenario, but possible), the client would fail to connect, the user would get an error, and they'd try something else. It wouldn't generate support tickets because nobody actually uses example.com for real email accounts.

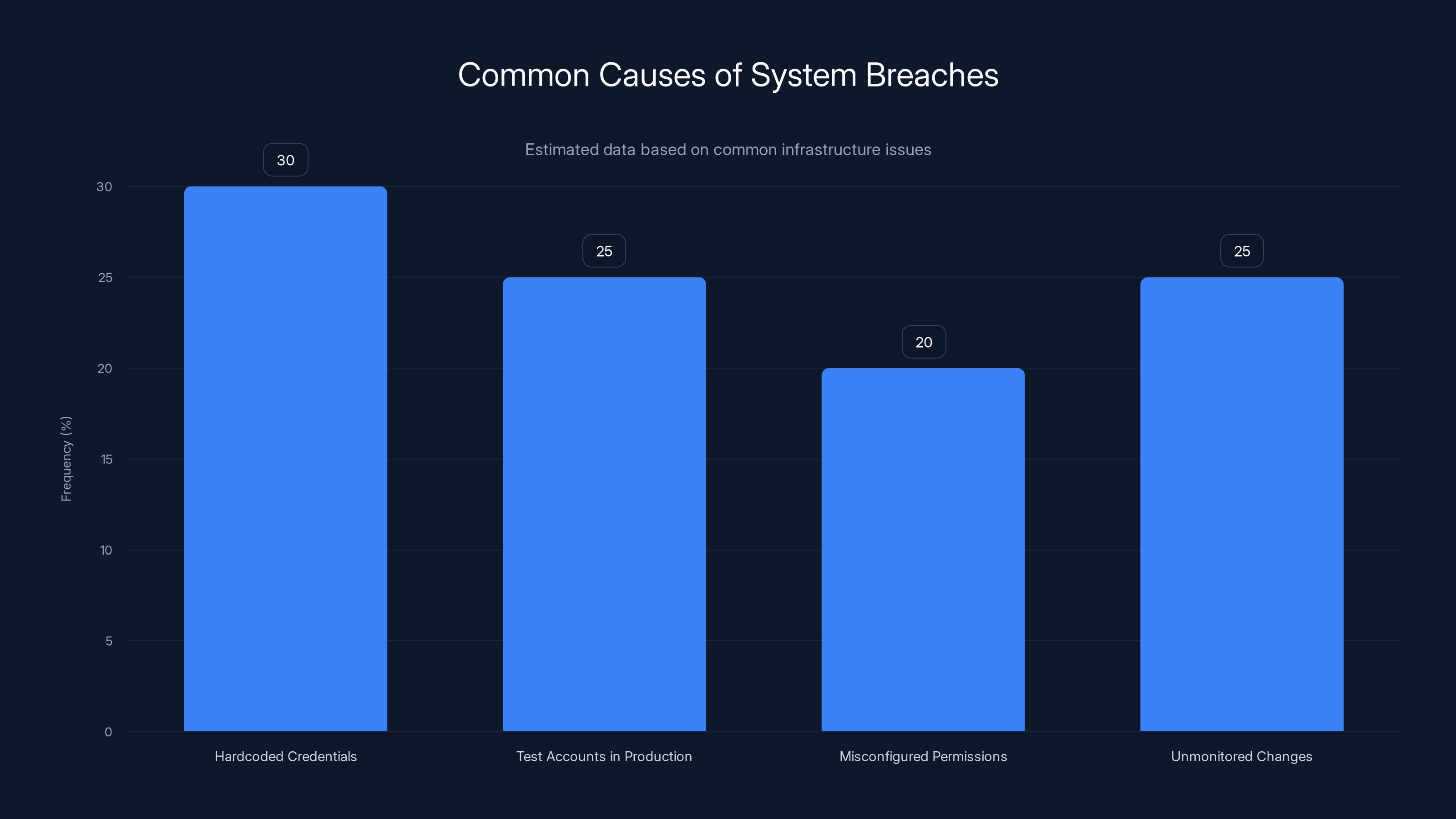

Basic mistakes such as hardcoded credentials and unmonitored changes are frequent causes of system breaches. Estimated data.

The Sumitomo Electric Connection: A Mystery Within the Incident

One question the incident raises but never answers: why Sumitomo Electric specifically?

Sumitomo Electric is a legitimate industrial company. It manufactures cables, semiconductors, and related components. It has corporate infrastructure, including email systems, hosted on sei.co.jp. The domain is real, registered, and probably has working mail servers.

But why would Microsoft's autodiscover system reference it?

One possibility: Sumitomo Electric and Microsoft have some kind of partnership or service agreement. Maybe Sumitomo Electric uses Microsoft 365, and at some point, there was a legitimate reason to configure cross-domain autodiscover behavior. But that would be unusual and would typically be handled through proper federation mechanisms, not hardcoded mappings.

Another possibility: The mapping was added as part of testing collaboration between Microsoft and Sumitomo Electric. If Sumitomo Electric was beta-testing Outlook Copilot or some other new feature, Microsoft's test infrastructure might have included references to Sumitomo Electric's email systems. But again, that should have been removed before the code reached production.

A third possibility: The mapping is completely accidental. Someone copy-pasted a configuration file, or imported a configuration template from the wrong source, and sei.co.jp ended up in there by chance. This is remarkably common in distributed systems—you copy an old configuration as a starting point, intending to modify it, but somehow the old values stay.

Microsoft's public statements haven't clarified which scenario is accurate. The company confirmed it updated autodiscover to stop returning server information for example.com, but didn't explain how sei.co.jp got there in the first place.

From a security perspective, this ambiguity is concerning. If you don't understand how a misconfiguration happened, you can't be confident you've fixed all similar issues.

The Security Implications: What Could Have Gone Wrong?

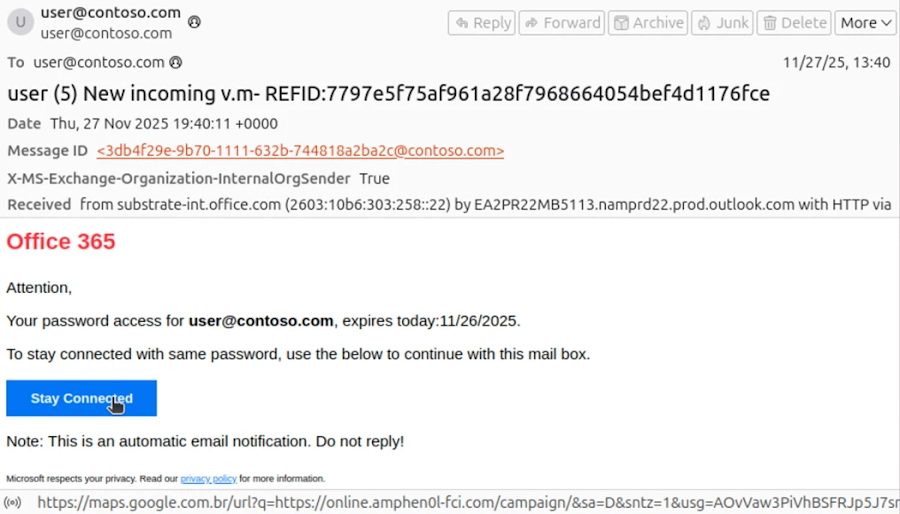

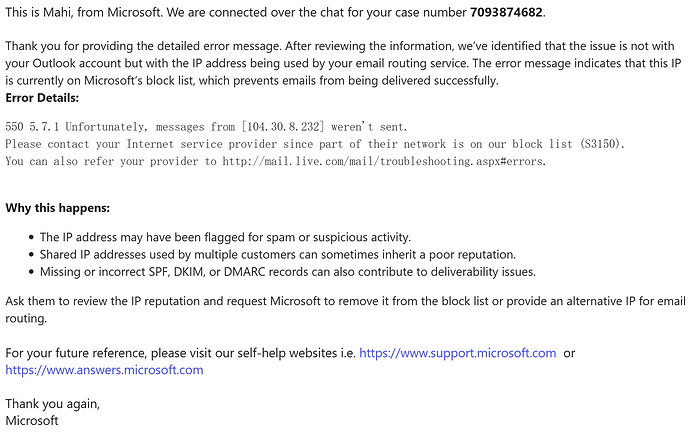

On the surface, this incident didn't compromise user accounts or expose sensitive data. No evidence suggests real user credentials were exposed or that real mailboxes were accessed. The routing behavior only affected test traffic using example.com, a domain nobody actually uses for email.

But zoom out, and the security implications are more serious than they first appear.

First, this demonstrates that Microsoft's autodiscover system can be made to return arbitrary server configurations. If the internal mechanism that added sei.co.jp to the system can be exploited by an attacker, they could potentially cause Outlook clients to connect to attacker-controlled mail servers.

Such a compromise wouldn't need to target example.com specifically. If an attacker could inject a mapping for any domain—say, company.com—they could intercept mail for that company. Outlook clients would try to authenticate with the attacker's server instead of the real mail server. They wouldn't get access (because they'd use the legitimate credentials), but they could log those credentials.

This is a known attack pattern called a mail-in-the-middle attack, and it's one reason email systems have authentication mechanisms like SPF, DKIM, and DMARC. But if the client is being misdirected at the protocol level by a trusted system (like autodiscover), those protections might not help.

Second, this shows a fundamental gap in internal monitoring and validation. If something this visible can hide for years, what else is hiding? Configuration databases that nobody validates. Services that nobody checks. Assumptions that never get verified.

Third, and perhaps most importantly, this incident reveals how easily testing infrastructure can become production infrastructure. There's a reason RFC 2606 created reserved domains: to ensure a clear separation between test and production. But that separation only works if every system respects it. When one system blurs the line, it weakens the whole model.

Estimated data showing the distribution of steps in the Autodiscover process. Each step plays a crucial role in determining the correct mail server configuration.

How Microsoft Responded: And Why the Response Feels Incomplete

When researchers first reported the anomaly, Microsoft didn't immediately clarify what was happening. For several days, the company provided no explanation, even internally. Engineers at Microsoft apparently had no quick answer for why example.com was routing to sei.co.jp.

This isn't necessarily negligence. In a system as complex as Microsoft's, it can take time to trace a misconfiguration back to its source. But it also suggests that nobody had visibility into the domain mapping system—nobody could quickly answer "why is this entry here?"

Eventually, Microsoft updated the autodiscover service to stop returning server information for example.com. By the following Monday, the routing behavior had ceased. Instead of returning valid mail server hostnames, requests to the endpoint timed out or returned "not found" errors, which is the correct behavior for reserved domains.

But Microsoft's public statement was thin on details. The company acknowledged the issue and confirmed it had fixed it, but provided minimal explanation of root cause or scope. The investigation remained open, Microsoft said, which typically means they're still determining how the misconfiguration happened and how long it persisted.

This incomplete response left several questions unanswered:

- How was the mapping initially added to the system?

- Who added it and when?

- Was it intentional or accidental?

- How many other test configurations exist in production autodiscover systems?

- What was the change control process (or lack thereof) that allowed this to persist?

From a transparency standpoint, enterprises would benefit from more thorough post-mortems. Not because we need to blame individuals, but because understanding failure modes is the only way to prevent them in the future.

Patterns: Configuration Issues at Scale

This incident isn't isolated. It's part of a broader pattern of configuration-related security issues that plague large organizations.

Look back at other Microsoft incidents: the test account left active in Azure Active Directory that allowed attackers to access internal systems. The Exchange Server vulnerability that required hardcoded credentials to fix. The countless misconfigured S3 buckets that expose data for companies of all sizes.

Configuration security is genuinely hard at scale. You can't rely on individual engineers to remember that every configuration they add might persist for years. You can't assume that all changes will go through proper review. You can't trust that monitoring will catch everything.

What you can do is implement layered controls:

-

Declarative configuration with version control: Every configuration entry should be tracked in Git or similar. Changes should require pull requests and reviews. You should be able to answer "who changed this and when" for every production setting.

-

Automated validation: Before any configuration change reaches production, it should be validated against a ruleset. Reserved domains shouldn't appear in production mappings. Test infrastructure shouldn't be mixed with production infrastructure. Service accounts shouldn't have high privileges.

-

Regular audits: At least quarterly, organizations should sweep their configuration databases looking for obvious mistakes: hardcoded IP addresses, test credentials, reserved domains, orphaned services, etc.

-

Separation of concerns: Test infrastructure should use different systems than production. You shouldn't be reaching into the same database for both. Separate systems cost more, but they eliminate the possibility of test configuration leaking into production.

-

Clear ownership: Someone, or some team, should be responsible for the configuration database. Not as a side task, but as their primary responsibility. That ownership includes regular review, cleanup, and documentation.

Most organizations have one or two of these controls. Few have all five.

Misconfiguration is the most frequent issue in autodiscover systems, highlighting the need for better monitoring and testing. Estimated data.

The Broader Context: Infrastructure Complexity and Visibility

Microsoft operates one of the largest technology infrastructures on Earth. Hundreds of millions of customers rely on Microsoft 365, Azure, and other services. That scale creates both advantages and challenges.

The advantage is that Microsoft can afford to hire exceptional infrastructure engineers and invest in sophisticated monitoring and redundancy. The challenge is that no amount of expertise fully solves the complexity problem.

When you're operating at that scale, invisible mistakes become inevitable. Not because the people are bad, but because human cognition has limits. You can't track every configuration, audit every change, monitor every endpoint. You have to trust systems to do it for you. And when those systems weren't designed for this scenario, things fall through the cracks.

The example.com incident is a microcosm of this. The mistake was probably obvious in hindsight ("Why is this domain mapping here?"), but finding it required either:

- Someone specifically looking for it, or

- Someone stumbling across it while testing something else

Neither is a reliable way to catch misconfiguration. You need preventive systems.

What's also striking is that this incident, while visible to outside researchers, apparently generated no internal alarms. Autodiscover serves millions of clients. If even a small percentage were using example.com, the traffic would show up in logs. Either the traffic was isolated to specific test environments, or logs weren't being analyzed for this pattern.

Best Practices: How to Avoid Similar Issues

If you maintain email infrastructure, APIs, or any service where configuration errors could have security implications, here's what to learn from this incident:

First, assume configuration mistakes will happen. Don't rely on people to remember not to use reserved domains or test infrastructure in production. Assume someone will do it anyway, and build systems that prevent it.

Second, treat configuration as code. Version it, review it, test it. Use infrastructure-as-code tools like Terraform or Cloud Formation to manage configuration. Make it impossible to have undocumented manual changes.

Third, implement a strict separation between test and production. Don't just use environment variables to switch modes. Use completely different systems, different databases, different credentials. Make it so that test data cannot possibly leak into production.

Fourth, automate validation. Before any configuration change is deployed, scan it for common problems: reserved domain references, test credentials, hardcoded IPs, etc. This can be as simple as a Bash script that runs as part of your deployment pipeline.

Fifth, maintain a configuration audit log. Not just for compliance, but for operational understanding. When something goes wrong, you should be able to see exactly what changed, when it changed, and who changed it. You should also be able to see what triggered the change (which code commit, which deployment, which request).

Sixth, rotate responsibility for configuration review. Don't let one person become the keeper of "configuration knowledge." Regularly have different engineers audit the system. Fresh eyes catch things that familiar eyes miss.

Seventh, test your tests. Run your test infrastructure intentionally. Make sure test environments actually use test domains and test credentials. Verify that test data doesn't leak into production monitoring or logging.

None of this is revolutionary. This is hygiene-level infrastructure management. But it's easy to defer when things are working and pressure is high to ship features.

The Incident as a Teaching Moment

What makes the example.com incident valuable isn't that Microsoft is uniquely incompetent—they're not. It's that it reveals how much infrastructure complexity can hide in what should be simple systems.

Autodicover is supposed to be straightforward: given a domain, return the mail server. How hard could that be? And yet, we see that at scale, with hundreds of services and thousands of configuration entries, even straightforward systems develop hidden problems.

The lesson applies beyond email and beyond Microsoft. It applies to anyone operating systems at scale:

- Configuration that works at small scale breaks at large scale

- Visibility has to be built in, not assumed

- Tests are only useful if they actually run and catch things

- The absence of complaints doesn't mean everything is fine

- Every assumption about how a system should work should be validated regularly

For security professionals, this incident is a reminder that most breaches aren't the result of sophisticated zero-day exploits. They're the result of basic mistakes—hardcoded credentials, test accounts left in production, misconfigured permissions—being left unattended for long enough that someone finds them.

For engineers building systems, it's a reminder that the systems you build need to fail safely. If something goes wrong in your system, it should default to denying access, not granting it. It should timeout or return an error, not return invalid data.

For infrastructure teams, it's a reminder that you need monitoring and alerting for the things you don't expect to see. Don't just alert on traffic spikes or error rates. Alert on configuration changes, on new domains appearing in mappings, on test infrastructure being referenced in production systems.

What Happens Next: Ongoing Questions

As of the last update, Microsoft's investigation into the incident remained ongoing. The company hasn't provided a complete public post-mortem, which is understandable from a liability perspective but unfortunate from a transparency perspective.

Open questions include:

- Was the sei.co.jp mapping intentional or accidental?

- How many other test configurations exist in similar systems?

- Has Microsoft implemented additional safeguards to prevent reserved domain references in production?

- Why didn't existing monitoring and validation systems catch this?

- Has Microsoft audited other critical services for similar issues?

For the security community, the incident serves as a useful benchmark. It shows that even companies with the resources and expertise to build bulletproof infrastructure sometimes don't. The reasons are typically organizational, not technical: unclear ownership, siloed teams, competing priorities, and the inevitable entropy of systems at scale.

FAQ

What is example.com and why is it reserved?

Example.com is a domain specifically designated by RFC 2606 for use in documentation and examples. The internet engineering community set it aside, along with example.org, example.net, and example.edu, to ensure developers and documentation writers had domains they could use in tutorials, code examples, and testing without accidentally affecting real services. These domains should never resolve to legitimate services in production systems.

How does Microsoft's Outlook autodiscover work?

Outlook autodiscover is a feature that allows users to configure email accounts without manually entering server settings. When you provide an email address and password, the Outlook client queries the domain's autodiscover endpoint to retrieve mail server information including IMAP server address, SMTP server address, port numbers, and authentication methods. This eliminates the need for users to understand technical details about their mail provider's infrastructure.

Why was routing test email traffic to Sumitomo Electric a problem?

The incident revealed that Microsoft's autodiscover system was returning valid mail server configurations for example.com, pointing to servers at Sumitomo Electric's domain (sei.co.jp). This violated the fundamental purpose of reserved domains and demonstrated that a critical Microsoft service could be misconfigured without detection for years. It exposed potential vulnerabilities where attackers might manipulate autodiscover to redirect Outlook clients to attacker-controlled mail servers.

How did this misconfiguration persist for years without being detected?

The misconfiguration likely persisted undetected because nobody was specifically looking for it. Autodiscover endpoints aren't commonly probed by outside researchers, and internally, developers might have added the mapping intentionally for testing purposes without proper cleanup. Additionally, since example.com isn't used by real users, the incorrect configuration didn't generate support complaints or obvious errors that would trigger alerts.

What were the security implications of this incident?

While the incident didn't result in real user accounts being compromised, it demonstrated that Microsoft's autodiscover system could return arbitrary server configurations, potentially opening the door to mail-in-the-middle attacks where clients connect to attacker-controlled servers instead of legitimate mail servers. It also revealed significant gaps in configuration monitoring and validation systems that should have caught the misconfiguration immediately.

What steps should organizations take to prevent similar issues?

Organizations should implement layered controls including version-controlled configuration as code, automated validation that prevents reserved domain references in production, regular audits of configuration databases, strict separation between test and production systems, clear ownership of configuration management, and regular rotation of review responsibilities. Additionally, services should be designed to fail safely—returning errors for unexpected inputs rather than returning invalid data.

Did Microsoft provide a complete explanation of how this happened?

No. Microsoft acknowledged the issue and fixed it by disabling the problematic routing behavior, but provided minimal details about root cause or how long the issue persisted. The company stated the investigation was ongoing but hasn't released a complete post-mortem explaining who added the mapping, when, and why. This limited transparency left many questions unanswered about the scope and severity of the incident.

How common are configuration-related security incidents at large companies?

Configuration-related security issues are remarkably common at scale. Other Microsoft incidents have included test accounts left in Active Directory and hardcoded credentials in Exchange. Across the industry, misconfigured S3 buckets, exposed API keys, and abandoned test infrastructure are regular occurrences. The pattern suggests that configuration security is fundamentally difficult at enterprise scale and requires deliberate architectural choices to manage effectively.

Conclusion

The Microsoft example.com incident is fascinating not because it represents a catastrophic security breach—it doesn't—but because it reveals how infrastructure problems hide in plain sight at massive scale. A configuration entry pointing a reserved test domain to a Japanese manufacturing company should trigger alarms immediately. Yet it persisted for years inside one of the world's largest technology companies.

The root cause wasn't malice or incompetence. It was the inevitable entropy of complex systems: test configurations that never got cleaned up, monitoring systems that weren't checking the right things, documentation that didn't keep pace with reality, and a lack of clear ownership over a critical system.

Microsoft didn't provide a complete post-mortem, which means the details remain murky. We don't know definitively how sei.co.jp ended up in autodiscover responses, though we can speculate. We don't know whether this was a one-off mistake or symptomatic of broader configuration hygiene problems. We don't know what additional safeguards the company implemented to prevent recurrence.

What we do know is that this incident serves as a teaching moment for anyone building infrastructure at scale. Configuration mistakes happen. Test infrastructure leaks into production. Domains get mapped incorrectly. The question isn't whether these things will happen—they will. The question is whether your systems are designed to catch them before they become problems.

If you operate email infrastructure, cloud services, APIs, or any system where configuration errors could have security or reliability implications, audit your configuration systems today. Look for reserved domain references. Look for test infrastructure in production. Look for configuration entries without documentation or approval records. Look for systems without version control or audit logs.

You'll probably find things that surprise you. Everyone does. The companies that manage infrastructure well aren't the ones that never make mistakes—they're the ones that catch their mistakes before the mistakes catch them.

The Microsoft incident proves that even the best-resourced companies can miss obvious problems when the systems designed to catch them aren't working properly. Learn from that. Build better.

Use Case: Automatically documenting infrastructure configuration changes and validating that production systems don't reference test domains or reserved IP ranges.

Try Runable For Free

Key Takeaways

- Microsoft's autodiscover system returned valid mail server configurations for example.com, a reserved test domain, for several years without detection

- The routing pointed to sei.co.jp, legitimately registered to Sumitomo Electric, suggesting a configuration entry that either leaked from testing or was accidentally left in production

- Multiple infrastructure safeguards failed simultaneously: configuration validation, version control, testing, monitoring, and change management systems didn't catch the error

- Configuration drift at massive scale is nearly inevitable without deliberate architectural separation between test and production systems

- Organizations should implement layered controls including version-controlled configuration-as-code, automated validation, regular audits, clear ownership, and complete separation of test infrastructure from production

Related Articles

- Microsoft's Example.com Routing Anomaly: What Went Wrong [2025]

- Microsoft 365 Outage 2025: What Happened, Why, and How to Prevent It [2025]

- Cloud Security in Multi-Cloud Environments: Closing the Visibility Gap [2025]

- Why Your Backups Aren't Actually Backups: OT Recovery Reality [2025]

- SkyFi's $12.7M Funding: Satellite Imagery as a Service [2025]

![Microsoft's Strange Email Routing Mishap: What Happened to example.com [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/microsoft-s-strange-email-routing-mishap-what-happened-to-ex/image-1-1769889944720.jpg)