The Convergence of Two Musk Empires

When you're running both the world's most ambitious AI company and a rocket manufacturer simultaneously, there's only one logical next step: build a city on the moon and shoot AI satellites into deep space using a maglev train.

That's not hyperbole. That's where Elon Musk landed when plotting the future of x AI and Space X after their merger.

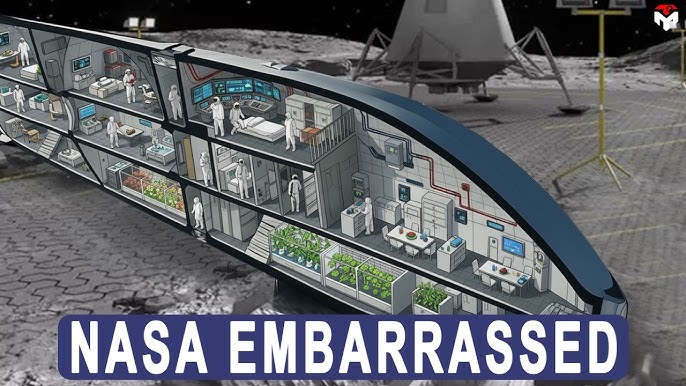

The announcement came during an all-hands meeting at x AI, where Musk outlined what he's calling Moonbase Alpha, a lunar facility designed to manufacture advanced AI computing systems and launch them into deep space. The move represents something more significant than another audacious Musk-ism: it's a strategic pivot for two companies that needed a shared vision.

For years, Space X had Mars. The Red Planet served as Space X's north star, a recruiting tool, and a narrative anchor that unified wildly disparate engineering efforts into a coherent long-term mission. "Occupy Mars" wasn't just a slogan—it was identity. It explained why the world's most expensive rocket company deserved to exist when the fundamentals of its business model didn't quite work on Earth alone.

But Mars became a problem. Not because it's too far away or technically impossible. Because nobody would actually pay for it. When Space X announced plans in 2016 to repurpose its Dragon spacecraft as a Mars lander, the company quietly abandoned the concept a year later after realizing the actual cost exceeded even the most generous venture capital patience. NASA would pay Space X to land astronauts on the moon. Customers would pay for Starlink internet. But Mars? Mars was aspirational unprofitability.

Meanwhile, x AI faced a different problem. Fresh off a merger that combined an AI research lab with a rocket company, Musk needed to explain why these two entities belonged together. Data centers in orbit made sense—computational density without thermal limits, endless solar power, lower latency for certain applications. But that was engineering logic, not inspiration.

Then Musk did what he does best: he found a metaphor big enough to contain both businesses and still leave room for expansion. Enter the Kardashev Scale.

Understanding the Kardashev Scale and Its Application to AI

The Kardashev Scale isn't new. Soviet astrophysicist Nikolai Kardashev proposed it in 1964 as a theoretical framework for measuring how advanced civilizations are by their energy consumption.

A Type I civilization would harness all the energy available on its home planet. Current human civilization ranks somewhere around 0.73 on this scale—we capture energy from fossil fuels, hydroelectric sources, solar panels, and nuclear reactions, but we're nowhere near capturing the sun's total energy output hitting Earth.

A Type II civilization would construct infrastructure to capture the entire energy output of its star. Think Dyson spheres or stellar engines. A Type III civilization would control all the energy in an entire galaxy.

We're nowhere close to any of this. But Musk is using the scale as a narrative framework to justify infrastructure investments that individually make sense but collectively point toward something grander.

The pitch is elegant: if you want to build artificial general intelligence, you need staggering amounts of computing power. If you want computing power, you need energy. If you want cheap, unlimited energy, you need to get to space. And if you want to maximize energy capture in space, you might as well build manufacturing capacity there to avoid launching finished products from deep gravity wells.

What makes this framework so useful for Musk is that it scales infinitely. You start with data centers in low Earth orbit. Then you graduate to lunar manufacturing. Then you're talking about solar collectors in space. Then you're positioning for the next 500 years of technological development. Every intermediate step is profitable; every endpoint justifies the journey.

But here's where the vision gets specific: Musk isn't just talking about abstract energy capture. He's talking about building a mass driver on the moon.

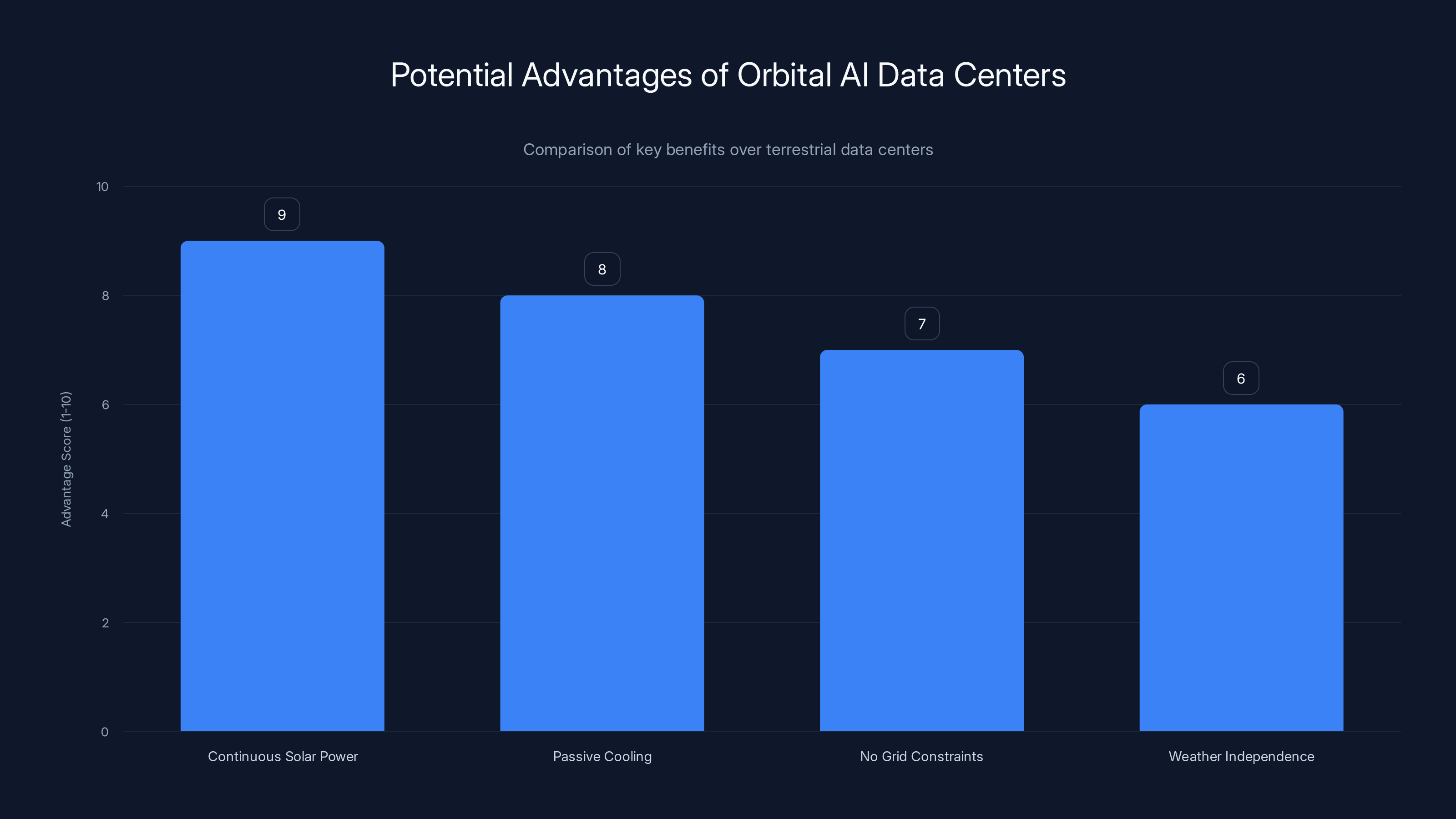

Orbital AI data centers offer significant advantages such as continuous solar power and passive cooling, scoring high on potential benefits compared to terrestrial centers. (Estimated data)

Mass Drivers: The Lunar Logistics Technology That Changes Everything

A mass driver is a form of linear accelerator that uses electromagnetic force to accelerate objects along a track at tremendous speeds. Imagine a maglev train that instead of carrying passengers launches satellites.

On Earth, a mass driver doesn't make much sense. Our atmosphere is thick, gravity is strong, and we've already optimized traditional rockets to launch stuff to orbit. But on the moon? The moon has about 1/6th of Earth's gravity and no atmosphere. If you can build a mass driver long enough and energize it sufficiently, you could launch payloads into deep space at velocities that would require absurd fuel expenditures from Earth-launched rockets.

This is where Musk's vision becomes genuinely clever engineering thinking wrapped in audacious framing.

Consider the physics. A rocket launched from Earth needs to overcome Earth's 1g gravitational pull plus atmospheric drag. By the time a spacecraft escapes Earth's gravitational well, it's burned enormous fuel just fighting gravity. A mass driver on the moon could accelerate AI satellites to near-escape velocity with no atmospheric losses, no gravity losses, and using solar power rather than chemical energy.

The second-order benefits multiply. If you're manufacturing advanced computing hardware on the moon using local resources (mined regolith, potentially extracted water ice), you avoid the cost of lifting finished products from Earth's gravity well. You also position your infrastructure near infinite solar power with no weather, no season, no night cycle.

Historically, mass driver concepts were pure physics papers. Arthur C. Clarke wrote about them. Theorists published papers on optimal launch angles and acceleration profiles. But nobody built one because nobody had sufficient reasons to justify the engineering effort.

Musk's pitch is different. With Space X managing launch logistics and x AI providing a customer with essentially unlimited computational appetite, a lunar mass driver goes from theoretical curiosity to infrastructure that makes business sense.

The engineering challenges remain staggering. You'd need to build a launch facility on the moon. You'd need to develop lunar construction techniques that work in vacuum and low gravity. You'd need to create spacecraft designed to withstand violent acceleration without damage. You'd need to establish reliable power generation. And you'd need to manufacture advanced computing hardware in an environment where a spacesuit leak is fatal and technical problems require either robotics or months of supply ship logistics.

But each of these challenges has a path to solution. Robotics can handle vacuum construction. Space X's Starship is designed for frequent lunar missions. Advanced ceramics and composite materials can survive launch accelerations. Solar panels function perfectly on the moon's vacuum.

The real question isn't whether a mass driver is possible. It's whether the computational benefits justify the infrastructure investment.

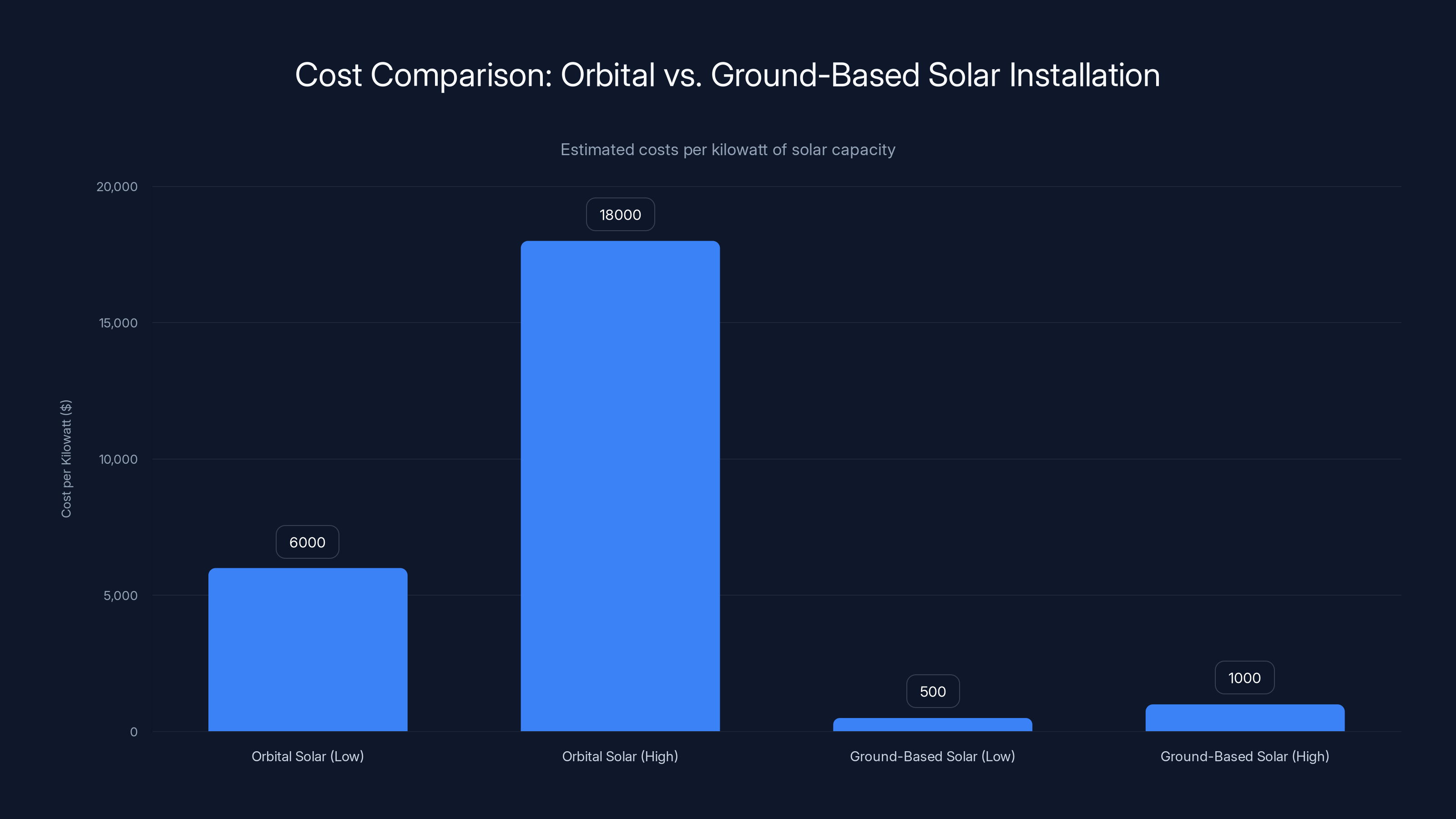

Orbital solar installation costs are currently much higher than ground-based, ranging from

The Economics of Orbital and Space-Based AI Infrastructure

Let's get to the financial reality, because this is where Musk's grand vision confronts actual business logic.

AI training requires absurd amounts of electricity. Open AI's latest generation models consume gigawatts of power continuously. A single data center training cutting-edge models can consume as much electricity as a small city.

On Earth, electricity costs between

In orbit, solar panels receive constant sunlight without atmospheric filtering. No cooling requirements beyond passive radiators (the vacuum of space is an excellent heat sink). No cooling water. No grid infrastructure. No location constraints beyond "needs line of sight to the sun."

The math on electricity cost in space is theoretically extraordinary. If you can deliver solar panels to orbit and install them, the marginal cost of electricity approaches zero. No fuel, no transmission losses, no grid fees.

But "delivering solar panels to orbit" is the hidden cost. Today, it costs roughly

Compare that to ground-based solar, which costs roughly

However, Musk's theory is that rapid reusability changes the equation. Starship is designed for same-day turnaround between launches. If launch costs truly collapse to $50 per kilogram (a target Musk has discussed), the economics flip. Suddenly, orbital power becomes cheaper than ground-based power when you factor in continuous 24/7 availability, no weather downtime, and unlimited scalability.

The lunar mass driver doesn't solve the electricity problem; it solves the payload problem. Once you have affordable access to the lunar surface and proven manufacturing capability there, you avoid the cost of launching finished satellites from Earth's gravity well.

Consider a hypothetical AI satellite weighing 10,000 kilograms, manufactured on the moon and launched via mass driver: the entire cost is the energy to accelerate it and the mining/manufacturing labor. Compare that to launching the same satellite from Earth: 10,000 kilograms times

Musk stated in the all-hands meeting that with orbital AI data centers and lunar-launched satellites, the company could potentially harness "maybe even a few percent of the sun's energy" for AI training and operation. A few percent of the sun's energy output is roughly 10-100 petawatts. Current global electricity consumption is about 20 terawatts.

In other words, Musk is framing infrastructure that could provide 500 to 5,000 times the current global energy supply, all dedicated to AI computation.

Why Space X Needed AI, and Why x AI Needed Rockets

On the surface, the Space X-x AI merger seems like forcing two unrelated businesses together because Musk runs both. But the strategic logic is actually solid.

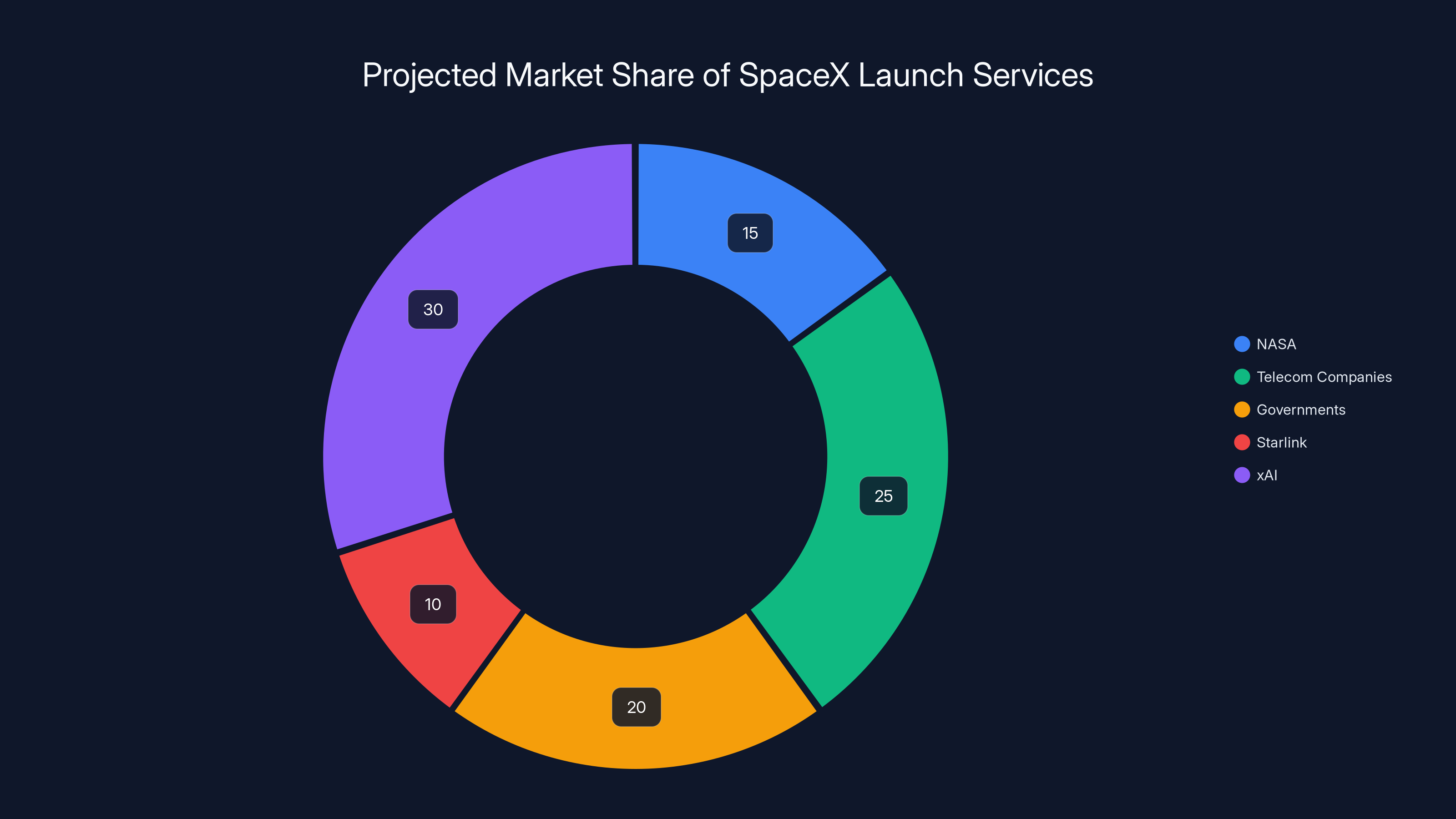

Space X's core business is launch services. It sells rides to orbit. The company has achieved remarkable efficiency through reusability and iteration, but it's fundamentally a service provider. Customers call, Space X launches their payload, Space X gets paid.

The problem: customers are finite. NASA buys astronaut rides. Telecom companies buy satellite launches. Governments buy intelligence satellites. Starlink (Musk's own constellation) is a recurring customer. But the addressable market for launch services is limited to the number of payloads humans want in space.

Unless Space X launches its own payloads.

Orbital AI data centers are Musk's answer to that problem. If x AI operates computing infrastructure in orbit, it becomes Space X's largest customer indefinitely. The customer's demand scales with AI development pace, which Musk controls directly. Space X launches regularly, operates infrastructure profitably, and generates recurring revenue.

Meanwhile, x AI had a different problem. Building AGI-class AI systems requires enormous computational resources. You can rent data center capacity from cloud providers like Amazon Web Services, Google Cloud, or Microsoft Azure. But you're at the mercy of their infrastructure, their pricing, their policies, and their willingness to serve an AI company that competes with their own AI initiatives.

Owning compute infrastructure directly—particularly infrastructure in space where your competitors can't easily access it—is a strategic moat. If you control the servers, you control your destiny.

The merger, then, makes sense: Space X gets a customer with infinite demand for launches. x AI gets infrastructure independence and the ability to scale without cloud provider constraints.

And Musk gets to frame the whole thing as climbing the Kardashev Scale, which sounds far more inspiring than "we merged two companies to create a vertically integrated supply chain."

Estimated data suggests that framing SpaceX as an 'Infrastructure Company' could significantly increase its IPO valuation to

Orbital Data Centers: The Near-Term Reality

Before we get to lunar mass drivers launching AI satellites into deep space, Space X and x AI actually need to prove that orbital data centers work at all.

This is the near-term play, the thing that could happen in the next 3-5 years if engineering and cost targets hold up.

Orbital data centers aren't new concepts. Jeff Bezos's Blue Origin has discussed orbital infrastructure. Various startups have proposed space-based computing. But actually building, launching, powering, cooling, and operating a functional data center in the hostile environment of low Earth orbit is a different challenge.

The technical barriers aren't insurmountable. Modern electronics can survive in vacuum. Solar panels work in space. Passive cooling (radiators that emit heat as radiation) can maintain equipment at reasonable temperatures. Power distribution systems exist. Communication links to Earth are established technology.

The difficult part is the full system working reliably at scale, with minimal human intervention, for years.

Consider cooling alone. On Earth, data centers use enormous amounts of water or air to dissipate heat generated by processors. In orbit, you can't use water (freezes solid in vacuum). You can't use air (there is none). Your only option is radiative cooling, where equipment emits infrared radiation into the vacuum of space.

Radiative cooling works, but it requires the equipment to run hotter than ground-based systems, which reduces efficiency. It requires large radiator surfaces. And it requires careful thermal management because if critical systems get too hot, they fail.

Power is another challenge. Orbital solar panels generate power, but that power must be stored in batteries for periods when the satellite passes through Earth's shadow. Modern lithium-ion batteries handle this, but adding a few megawatts of battery capacity adds weight, complexity, and thermal management challenges.

Reliability and maintenance is perhaps the biggest issue. If equipment fails in an orbital data center, you can't send a technician to fix it. You need to either design the system for fault tolerance (redundant components so failure of one system doesn't crash the whole facility) or plan for eventual replacement by launching new modules.

The cost implications are significant. A terrestrial data center might have redundancy at the component level. An orbital data center needs redundancy at the module level, because you can't perform field repairs. This means more equipment, more weight to launch, more power and cooling requirements.

But again, if Space X truly achieves the low launch costs they're targeting (and recent Starship tests suggest they might be on track), the economics become viable.

Musk hasn't specified when x AI would begin launching orbital data center modules, but the timeline implied by the merger is 2027-2029. By then, Starship should be operating at high frequency. Space X will have developed operational experience launching and servicing orbital stations. x AI will have matured its model architecture enough to know the exact computational requirements.

And if orbital data centers work—if they deliver cost-effective compute at scale—then the path to lunar infrastructure and mass drivers becomes suddenly more credible.

The Moon as a Manufacturing Hub: Challenges and Timelines

Here's where Musk's vision becomes a multi-decade commitment with no guarantee of success.

Lunar manufacturing isn't new theoretically. Researchers have published papers on how to extract water ice from lunar regolith, how to use that water to produce fuel and oxygen, how to mine useful minerals. The technical papers exist. The engineering paths are understood.

But moving from "theoretically possible" to "operationally reliable" involves solving hundreds of challenges that exist nowhere else in human experience.

First, transportation. To set up a manufacturing facility on the moon, you need to land equipment repeatedly. Starship is designed to land on the moon, but the operational frequency needed to establish and supply a manufacturing facility is unprecedented. Not one landing. Not five landings. Potentially dozens or hundreds of landings over multiple years to ferry equipment, resources, and repair parts.

Second, power. A manufacturing facility needs consistent, reliable power. Lunar night lasts about 14 Earth days. You can't just turn off a manufacturing plant for two weeks. You'd either need to store enormous amounts of energy in batteries or position infrastructure at the lunar poles where sun exposure is nearly continuous.

The lunar poles sound like a good option until you consider logistics. The poles are difficult to land near (uneven terrain, permanently shadowed craters). They're far from the equator where other lunar activities might occur. And the infrastructure to support continuous operations at the poles requires that Space X develop sophisticated logistics chains.

Third, automation and robotics. Humans can't work on the lunar surface without spacesuits, and spacesuits limit work duration and capability. Manufacturing requires tools, equipment, and human-scale adjustments. All of that needs to happen via remote robotics or deployed robot systems that can operate in an environment where a malfunction means waiting months for replacement parts.

Fourth, raw materials. You need to mine the moon. That requires developing mining equipment that works in vacuum, lunar gravity, and perhaps extreme cold. You need to process regolith and extract useful materials. You need the entire supply chain of mining, refining, and manufacturing equipment built from scratch.

Musk acknowledged some of this complexity in the all-hands presentation by focusing on the vision rather than granular logistics. But logistics are where engineering ambitions go to encounter reality.

The timeline for lunar manufacturing is necessarily vague, but informed speculation suggests 15-20 years before you have operational manufacturing capacity at meaningful scale. That's 2040-2045.

A mass driver launching AI satellites into deep space? That's probably 20-25 years out, if it happens at all.

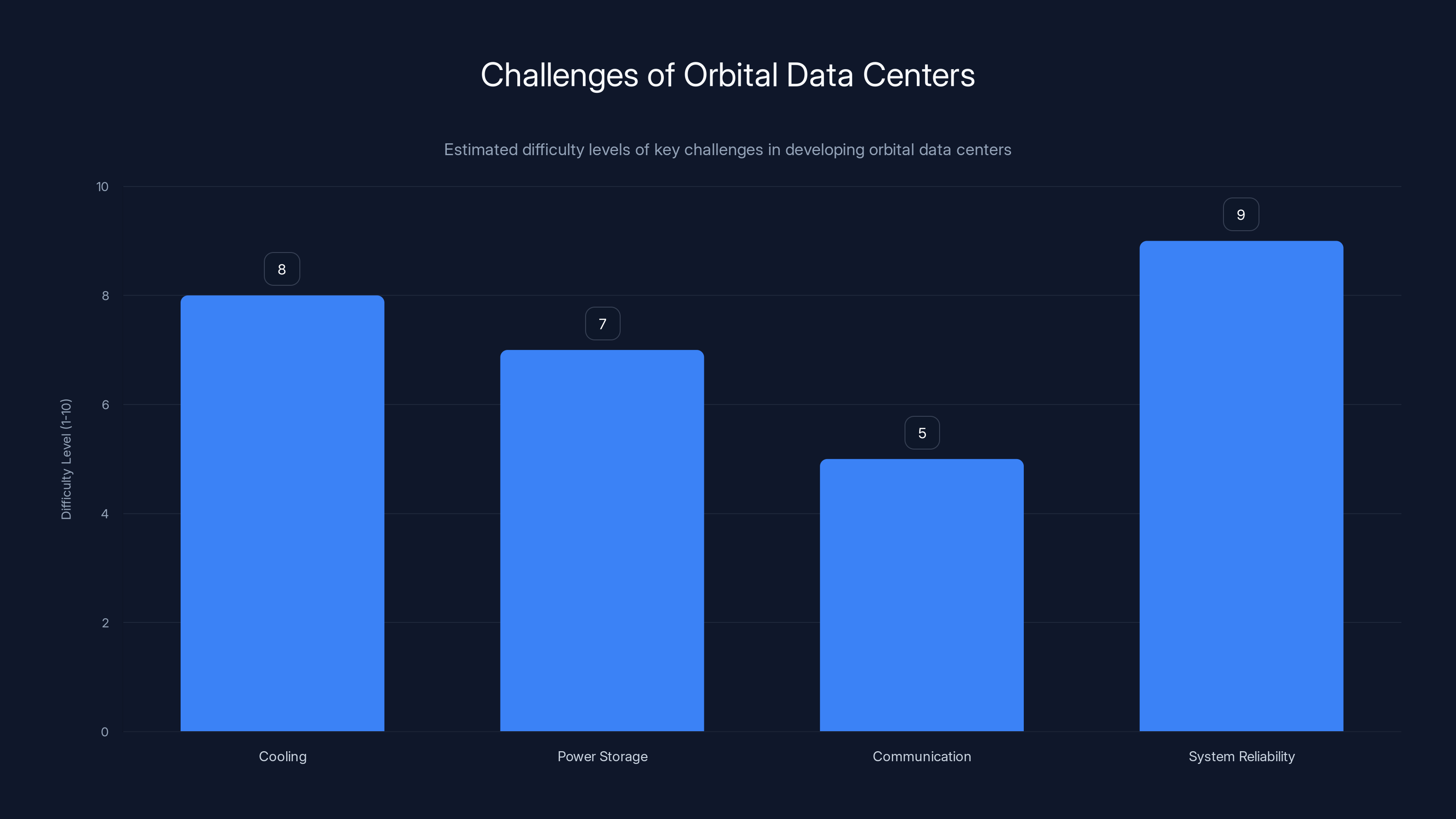

Cooling and system reliability are the most challenging aspects of developing orbital data centers, with cooling requiring innovative solutions like radiative cooling. Estimated data.

The Role of the IPO in Enabling Moonbase Alpha

Here's the business context that makes Moonbase Alpha credible rather than fantasy.

Musk needs capital. Lots of capital. Space X has been partially funded by government contracts, but those contracts are for specific objectives (launch astronauts, maintain Starlink, carry military payloads). None of them explicitly fund lunar infrastructure for AI manufacturing.

An IPO—the anticipated public offering of combined Space X-x AI—would raise capital from public markets. And public markets respond to narrative.

If Musk pitches Space X as "a launch service company," the valuation is constrained by addressable market for launch services. Space X might be worth

If Musk pitches Space X as "the infrastructure company building the Kardashev Scale," the narrative becomes open-ended. The company isn't selling launches; it's building the foundation for the next phase of human civilization. It's positioning for 500-year timescales. It's not limited by current market demand; it's enabling future markets that don't yet exist.

Public market investors love that story. Tesla didn't succeed because it was a profitable car company (it barely was for its first decade). Tesla succeeded because Musk framed it as infrastructure for sustainable energy—a market that could grow infinitely.

The same dynamic applies here. Space X-x AI pitches itself as the infrastructure company for post-human civilization. Moonbase Alpha isn't a side project; it's the visible symbol of a company thinking 30 years ahead.

That narrative justifies a valuation of

Of course, narrative alone doesn't sustain valuations. Execution matters. But execution timelines measured in decades are actually advantageous for this model. Investors don't need to see Moonbase Alpha built within five years. They just need to see steady progress: orbital data centers deployed, lunar landings increasing in frequency, first mining operations proving out.

The IPO, then, is the mechanism that funds Moonbase Alpha by raising capital from investors betting on the vision.

The Competitive Landscape: Is Anyone Else Building This?

Musk's competitors in space and AI might be noticing that he's just claimed the future.

Blue Origin is developing lunar landers and infrastructure, but hasn't articulated a vision that connects space infrastructure to AI computation. NASA is funding lunar missions through partnerships but hasn't committed to orbital data centers or deep space infrastructure for AI.

International space agencies (European, Chinese, Indian) have lunar ambitions, but they're framed as scientific exploration or resource utilization, not AI infrastructure.

The AI companies—Open AI, Anthropic, Google, Meta—are solving computational challenges by renting cloud infrastructure or building ground-based data centers. None have signaled plans to develop space-based infrastructure.

The gap is real. Musk has staked a claim to the intersection of space infrastructure and AI computation, and nobody else is positioned to compete in that space.

The risk is that the vision becomes a liability. If public markets lose confidence that Space X can execute on space-based infrastructure, the entire valuation collapses. The company becomes a launch service provider again, worth

But investors would rather own a company shooting for the stars (literally) than a company optimizing incremental improvements to launch efficiency.

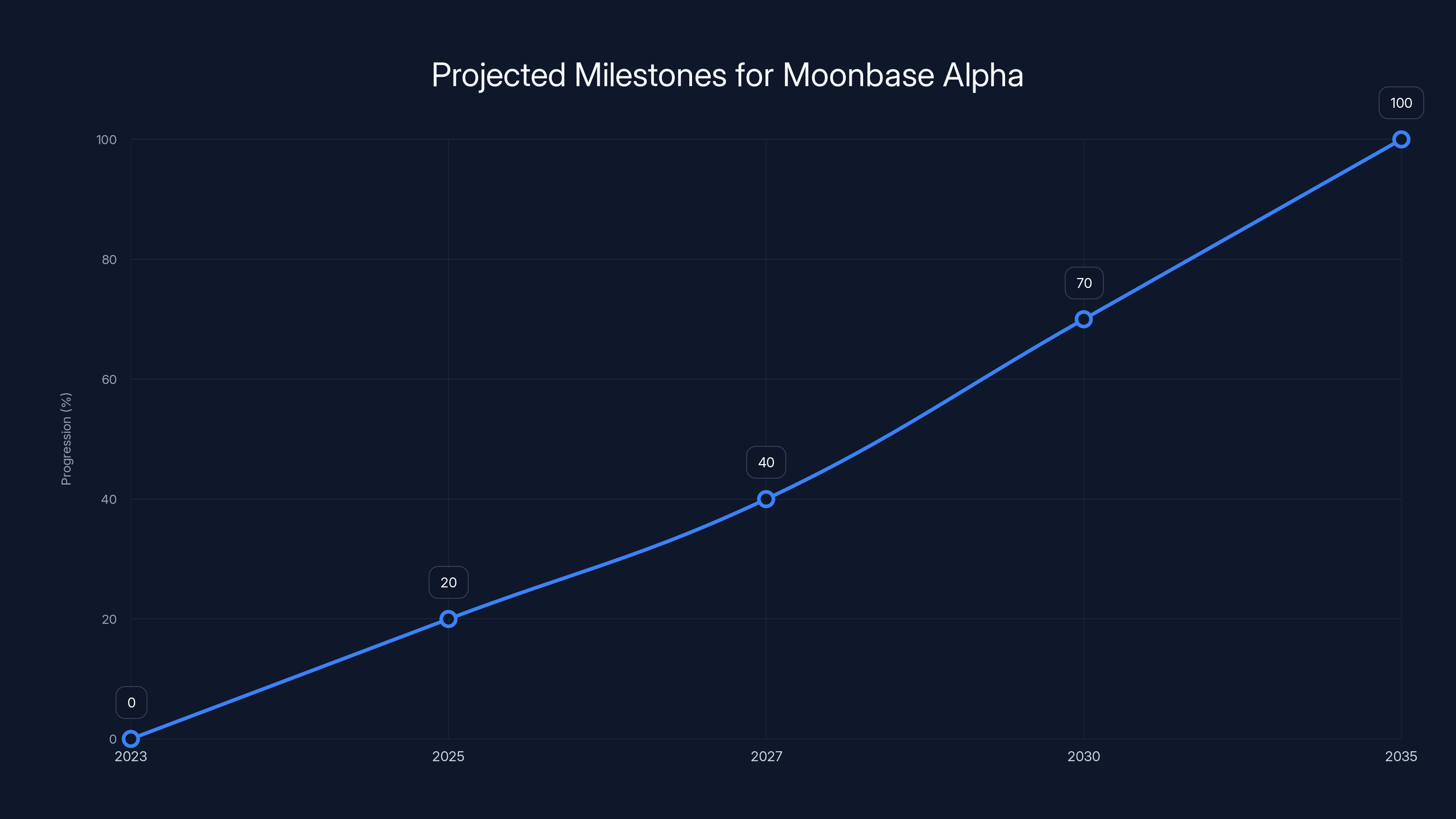

Estimated data shows potential progression of Moonbase Alpha's key milestones, highlighting the strategic steps from current capabilities to the envisioned lunar infrastructure.

Historical Parallels: How Musk Uses Vision to Build Companies

Musk has form in this area. He's done it before.

Tesla launched as an electric car company competing with Ford and General Motors. But Musk framed it as an energy company. Tesla was building batteries, solar technology, and sustainable infrastructure. The cars were just the most visible manifestation of that larger vision.

Investors understood. Tesla was worth more as "the company building sustainable energy infrastructure" than it would have been as "a car manufacturer." That frame justified a valuation that exceeded Ford and GM despite manufacturing a tiny fraction of vehicles.

Space X launched as a rocket company, but Musk framed it as a company solving the greatest challenge to human survival: ensuring the species is multi-planetary. That vision attracted top engineering talent willing to work for lower salaries because they believed in the mission. It justified maintaining enormous R&D spend despite commercial viability concerns. It made government agencies and private customers trust Space X to execute on unprecedented goals.

Moonbase Alpha is the same playbook. The facility itself is years away. But the vision—positioning AI and space infrastructure as adjacent facets of climbing the Kardashev Scale—changes how investors, employees, and customers perceive the company.

The key difference from previous Musk visions is that Moonbase Alpha required merging two companies to make sense. Neither Space X nor x AI alone can credibly pursue deep space AI infrastructure. But together, they can.

This explains why the merger happened when it did, and why Musk announced Moonbase Alpha immediately after consolidating leadership. The vision is the justification for the organizational structure.

What Moonbase Alpha Says About the Future of AI

Moonbase Alpha isn't just about rockets and moons. It's a statement about what Musk believes the future of AI looks like.

Specifically: he believes AI requires more power and energy than Earth can reasonably provide. He believes AI will be so computationally demanding that locating it on a planet becomes inefficient. He believes the future of intelligence—artificial and perhaps eventually other forms—lives in space.

This is different from how other AI researchers frame the problem. Most focus on improving efficiency: better algorithms, better hardware designs, better cooling techniques. The goal is to get more AI per watt, more computation per unit of energy.

Musk's framing is different. He's not trying to make AI more efficient. He's trying to make energy more abundant.

If the fundamental constraint on AI is electrical power, the solution isn't incremental improvements in chip design. It's moving to an environment where power is essentially unlimited. And that environment is space, where solar panels receive uninterrupted sunlight and can be deployed at arbitrary scale.

There's an implicit assumption in Moonbase Alpha that AGI—artificial general intelligence—will be so computationally expensive that it requires orders of magnitude more power than current systems. Whether that assumption is correct is unknowable until AGI exists.

But if it's true, Musk's vision positions Space X-x AI to own the infrastructure that AGI requires. That's extraordinarily valuable.

If it's false, if AGI can be achieved with improved algorithms and modest power increases, then Moonbase Alpha becomes an expensive monument to Musk's ambition.

The bet, then, is directional. Musk is betting that the constraint on AGI is power. His competitors are betting that the constraint is algorithms. And whichever bet is correct will dominate AI development over the next 20 years.

With the integration of xAI, SpaceX's largest customer is projected to be xAI itself, accounting for 30% of its launch services, surpassing traditional customers like NASA and telecom companies. Estimated data.

The Exit Interview: Why Executives Left x AI

The article mentions that Moonbase Alpha was announced alongside a restructuring at x AI, where "a stream of former executives exited the AI lab."

This is notable. If Moonbase Alpha was the grand vision uniting the company's purpose, why would executives leave?

Possible explanations:

First, some executives at x AI might have joined the company believing it was a focused AI research lab. The merger with Space X and the pivot toward space infrastructure was a strategic shift that didn't align with their career goals. A researcher who wanted to solve AGI might view moon bases as a distraction.

Second, announcing Moonbase Alpha simultaneously with an executive shakeup might signal that previous leadership didn't believe in the vision. Musk replaced them with people who do.

Third, this could be standard organizational churn. Companies go through phases. Early leadership helps establish culture. Scaled leadership optimizes operations. Visionary leadership points toward the future. If Musk decided x AI needed visionary leadership more than operational optimization, he'd swap executives accordingly.

The pattern Musk has exhibited at other companies is to surround himself with people who believe in his vision. If an executive doesn't believe in Moonbase Alpha, they probably weren't going to be convinced by continued arguments. Replacement was likely cleaner than attrition.

Potential Failure Modes and Unknowns

Musk's vision is compelling, but it rests on a series of engineering and economic bets that could easily fail.

Launch costs don't achieve targets: Space X is targeting

Orbital data centers prove less useful than expected: Space has unique properties (zero gravity, vacuum, extreme temperatures), but artificial intelligence doesn't inherently benefit from these properties unless you're doing something exotic like cryogenic computing. If orbital data centers don't meaningfully outperform ground-based alternatives, the demand for launches disappears.

Lunar logistics doesn't scale as assumed: Moving from Space X's current 5-10 lunar landings per year to the 50-100 landings needed to establish manufacturing might prove technically infeasible or permanently expensive. The equipment and human expertise to support that level of activity doesn't exist yet.

Manufacturing in vacuum proves harder than expected: Building things in terrestrial factories is hard. Building things in vacuum under remote control with multi-day communication delays and no possibility of repair is exponentially harder. Something that seems feasible in theory might prove impractical in execution.

Regulatory barriers: Governments might restrict what can be built in space or how lunar resources can be utilized. International space law is sparse, and nations might decide to reserve certain capabilities for governmental use only.

Technology disruption: A breakthrough in AI efficiency, in terrestrial power generation, or in computing architecture might make space-based infrastructure unnecessary before it's built.

Any of these represent possible futures. Musk's vision is real engineering thinking applied to genuine problems, but it's not guaranteed to succeed.

The Narrative as Product

One final observation: Moonbase Alpha might be as much about narrative as infrastructure.

When Musk announced Moonbase Alpha at the x AI all-hands meeting, the slides came at the end of the presentation, where, during Space X meetings, he typically shows renderings of rockets landing on Mars. The structural similarity is intentional. Moonbase Alpha takes Mars's place in the company's mythology.

This serves multiple functions:

For recruiting: Engineers want to work on meaningful problems. "Help us build the infrastructure for post-human civilization" recruits differently than "help us optimize data center costs."

For investors: Public markets value narrative. A company climbing the Kardashev Scale is more valuable than a company optimizing margins.

For customers: If x AI positions itself as serving the infrastructure needs of AGI, government agencies and private customers might prefer working with them over traditional cloud providers.

For morale: Working on Moonbase Alpha is inherently more inspiring than working on version 4.2 of a product that mostly works.

Musk understands this. He's not just building rockets and AI systems. He's building mythologies that make the engineering feel significant.

When Space X engineers worked on achieving reusability, the technical challenge was enormous. But the motivation was clearer: they were building the infrastructure for multi-planetary civilization. That narrative made engineers more willing to accept long hours, lower pay, and inevitable failures.

Moonbase Alpha provides the same function for the merged company. It's not just a facility. It's a symbol that Space X and x AI are thinking bigger than quarterly earnings and incremental product updates.

Long-Term Implications and Market Structure

If Musk even partially executes on Moonbase Alpha, the implications for the space and AI industries are profound.

First, it creates a defensible moat. If Space X owns the infrastructure for launching AI satellites from the moon, competitors are years behind. Blue Origin, Axiom, and other players in commercial space would need to replicate the entire infrastructure stack to compete.

Second, it changes the cost structure for space-based infrastructure. If launch costs fall, if lunar logistics becomes routine, if space-based manufacturing works, the entire industry shifts. Companies currently focused on incremental Earth-based improvements would need to radically accelerate their roadmaps or become obsolete.

Third, it realigns market power. Today, cloud providers like AWS, Google Cloud, and Azure own the infrastructure that AI companies depend on. If x AI owns space-based infrastructure instead, power dynamics shift. Independent AI labs become less dependent on cloud providers.

Fourth, it changes the competitive landscape for AI itself. If x AI has access to uniquely cheap, uniquely scalable computational resources that competitors can't access, it could become insurmountably dominant in AI development. That's an antitrust risk, but also a market reality.

Conclusion: Vision as Strategy

Moonbase Alpha is simultaneously audacious engineering and perfectly logical business strategy.

It's audacious because building a city on the moon and launching satellites with a mass driver sounds like science fiction.

It's logical because given the goals (scale AI to superintelligence, reduce Space X's dependence on external customers, increase launch frequency profitably), Moonbase Alpha is an internally consistent path forward.

The gap between where Space X and x AI are today and where Moonbase Alpha would require them to be is enormous. But the intermediate steps—orbital data centers, increased launch frequency, proven lunar landing operations—have near-term business value independent of the final vision.

This is Musk's actual genius: he frames long-term visions in ways that make near-term execution profitable.

Investors who bet on Moonbase Alpha aren't betting on lunar infrastructure in 2045. They're betting that the intermediate steps—more reliable launches, orbital computing capability, lunar logistics—will create value for decades before the final vision materializes, if it ever does.

Moonbase Alpha also serves the crucial purpose of unifying two previously separate companies under a shared mythology. Space X needed a customer with infinite demand. x AI needed infrastructure independence. Moonbase Alpha makes both needs obvious.

Whether Moonbase Alpha ever actually becomes a functioning facility is, in some sense, secondary. The narrative reorients both companies toward thinking about space-based infrastructure as central to their missions rather than peripheral. That reorientation alone changes how they make engineering decisions, recruit talent, and position themselves in markets.

Over the next 5-10 years, we'll see whether Moonbase Alpha transitions from narrative to reality. The technical foundations are sound. The engineering challenges are known. The market incentives exist.

What remains unknowable is whether Musk's execution on this vision matches his ambition. History suggests it might. But history also shows that even Musk's companies miss timelines and pivot strategies when reality doesn't cooperate.

Moonbase Alpha is real enough to drive engineering decisions today. Whether it's real enough to actually exist as a functioning facility in 2040 remains to be written. Either way, it's defined where Space X and x AI believe their future lies.

TL; DR

-

Musk's Moon Pivot: Space X and x AI merged with a new shared vision—Moonbase Alpha, a lunar manufacturing facility launching AI satellites into deep space via mass drivers, replacing Mars as the company's long-term narrative anchor.

-

The Kardashev Scale Framework: Moonbase Alpha positions the company to climb the Kardashev Scale by harnessing increasing amounts of solar energy (Earth orbit → moon → potentially a few percent of the sun's total output) for AI computation.

-

Mass Driver Technology: A lunar-based electromagnetic accelerator could launch AI satellites at near-escape velocities, avoiding the enormous fuel costs of launching from Earth's gravity well while using virtually free solar power.

-

Economics Made Real: If Space X achieves $50/kg launch costs and lunar operations become routine, orbital data centers and lunar manufacturing create genuine cost advantages over ground-based alternatives.

-

Strategy Beneath the Vision: The merger unites Space X's launch capability with x AI's computational demand, making each company dependent on the other's success and creating defensible market positions neither could achieve independently.

FAQ

What is Moonbase Alpha and why did Musk announce it?

Moonbase Alpha is a proposed lunar manufacturing facility where advanced AI computing systems would be built and launched into deep space using mass drivers. Musk announced it to provide Space X and x AI with a shared long-term vision after their merger, replacing Mars colonization (which Space X deprioritized) as the company's aspirational narrative. The facility represents a path to essentially unlimited energy for AI computation by harnessing solar power in space without terrestrial constraints.

How would lunar mass drivers actually launch AI satellites?

A mass driver is an electromagnetic linear accelerator that uses solar power to accelerate objects along a frictionless track. On the moon, with 1/6th Earth's gravity and no atmosphere, a mass driver could accelerate AI satellites to 2-3 kilometers per second, sufficient to reach deep space destinations. Unlike rockets (which burn fuel to escape gravity), a mass driver uses solar electricity to accelerate objects, making the marginal cost of each launch essentially zero once the infrastructure exists.

What would orbital AI data centers actually do?

Orbital data centers would house AI training and inference hardware in Earth orbit, using continuous solar power and the vacuum of space for passive cooling. They'd eliminate grid constraints, cooling water requirements, and weather-related downtime. The economics only work if launch costs drop dramatically and orbital facilities deliver genuinely superior performance to ground-based alternatives, which remains unproven.

Is anyone else building space-based AI infrastructure?

Blue Origin is developing lunar infrastructure but hasn't connected it to AI computation. NASA funds lunar missions but hasn't committed to orbital data centers. Traditional AI companies like Open AI, Anthropic, and Google are solving computational challenges through incremental improvements rather than space-based infrastructure. Musk has effectively staked a claim to this intersection with minimal competition.

When could Moonbase Alpha actually be operational?

Orbital data centers could potentially be deployed in the next 5-10 years if Space X achieves its launch cost targets. Lunar manufacturing would require 15-20 years of development and dozens of successful landing operations. A functional mass driver launching AI satellites is probably 20-25 years away, if it happens at all. The timeline is necessarily vague because the technical challenges are unprecedented.

Why would this vision help an IPO valuation?

Public market investors value narrative alongside execution. A company framed as "infrastructure for post-human civilization" justifies higher multiples than a company framed as "launch service provider." Space X positioned as a Kardashev Scale infrastructure play could be worth

What could derail Moonbase Alpha?

Launch costs might not drop to assumed levels, making space-based infrastructure uneconomical. Orbital data centers might not outperform ground-based alternatives meaningfully. Lunar logistics might prove harder to scale than expected. Manufacturing in vacuum might encounter unforeseen challenges. Regulatory barriers could restrict space-based development. Or a breakthrough in AI efficiency or terrestrial power generation might eliminate the need for space-based infrastructure before it's built.

How does this compare to previous Musk visions?

Moonbase Alpha follows the same playbook as Tesla (framed as sustainable energy infrastructure, not just cars) and Space X Mars (framed as multi-planetary civilization, not just rockets). Musk uses grand narratives to attract talent, justify investment, and create market positioning that wouldn't be justified by near-term financials alone. Moonbase Alpha is the same strategy applied to the AI infrastructure problem.

Key Takeaways

- Moonbase Alpha is SpaceX and xAI's shared vision to manufacture AI satellites on the moon and launch them via mass drivers, replacing Mars colonization as the companies' long-term narrative anchor.

- The Kardashev Scale framework positions space-based infrastructure as humanity's path to harnessing increasing energy abundance for AGI computation—from orbital data centers to lunar manufacturing to solar-scale infrastructure.

- Mass drivers could launch satellites at near-escape velocities using solar power instead of chemical rockets, dramatically reducing costs once terrestrial gravity and atmospheric drag are eliminated.

- Economics work only if SpaceX achieves $50/kg launch costs, orbital data centers deliver superior performance to ground-based alternatives, and lunar logistics becomes routine—three unproven assumptions.

- The merger unites SpaceX's launch capability with xAI's infinite computational demand, making each company dependent on the other's success and creating a defensible competitive position neither could achieve independently.

Related Articles

- xAI's Interplanetary Vision: Musk's Bold AI Strategy Revealed [2025]

- Elon Musk's Moon Satellite Catapult: The Lunar Factory Plan [2025]

- SpaceX Common Carrier Status: Labor Law Exemption Explained [2025]

- xAI's Lunar Manufacturing Plans: Musk's Moon Strategy Amid IPO & Leadership Exodus

- AI Inference Costs Dropped 10x on Blackwell—What Really Matters [2025]

- EU Data Centers & AI Readiness: The Infrastructure Crisis [2025]

![Moonbase Alpha: Musk's Bold Vision for AI and Space Convergence [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/moonbase-alpha-musk-s-bold-vision-for-ai-and-space-convergen/image-1-1770936013668.png)