The Biggest Labor Victory Space X Never Expected to Get

In February 2026, something remarkable happened in a government office that barely made headlines outside tech and labor circles. The National Labor Relations Board, an agency that's supposed to protect worker rights, essentially stepped aside from regulating Space X. Not because of a legal battle Space X won in court. Not because Congress passed new legislation. But because federal regulators decided to redefine what Space X actually is.

The US government decided Space X operates like an airline. This decision came wrapped in bureaucratic language and buried in official letters, but the implications are enormous. It means Space X is now regulated under the Railway Labor Act—a completely different legal framework than the one that protects workers at most American companies. And here's the kicker: the Railway Labor Act makes it dramatically harder for employees to strike, file complaints, or challenge management decisions.

When eight Space X employees wrote an open letter criticizing CEO Elon Musk as a "frequent source of embarrassment," Space X fired them. The NLRB had filed a complaint alleging this was illegal retaliation. But with this new classification, that entire complaint was dismissed. The case is gone. The protections those workers relied on? Also gone.

This wasn't inevitable. It wasn't the result of a lengthy court battle or a clear precedent. Instead, it emerged from a curious bureaucratic referral process where one agency essentially deferred to another on a question of legal jurisdiction. And the decision raises questions that nobody's really talking about: Can the federal government simply reclassify a company into a different legal category? What does it actually mean to call a rocket company an "airline"? And what happens to worker protections when regulatory agencies decide to step back?

The story of how Space X achieved this exemption reveals something deeper about how regulatory power works in America, how easily it can shift, and how quickly it can be reinterpreted when political winds change.

Understanding the Two Labor Systems That Now Matter

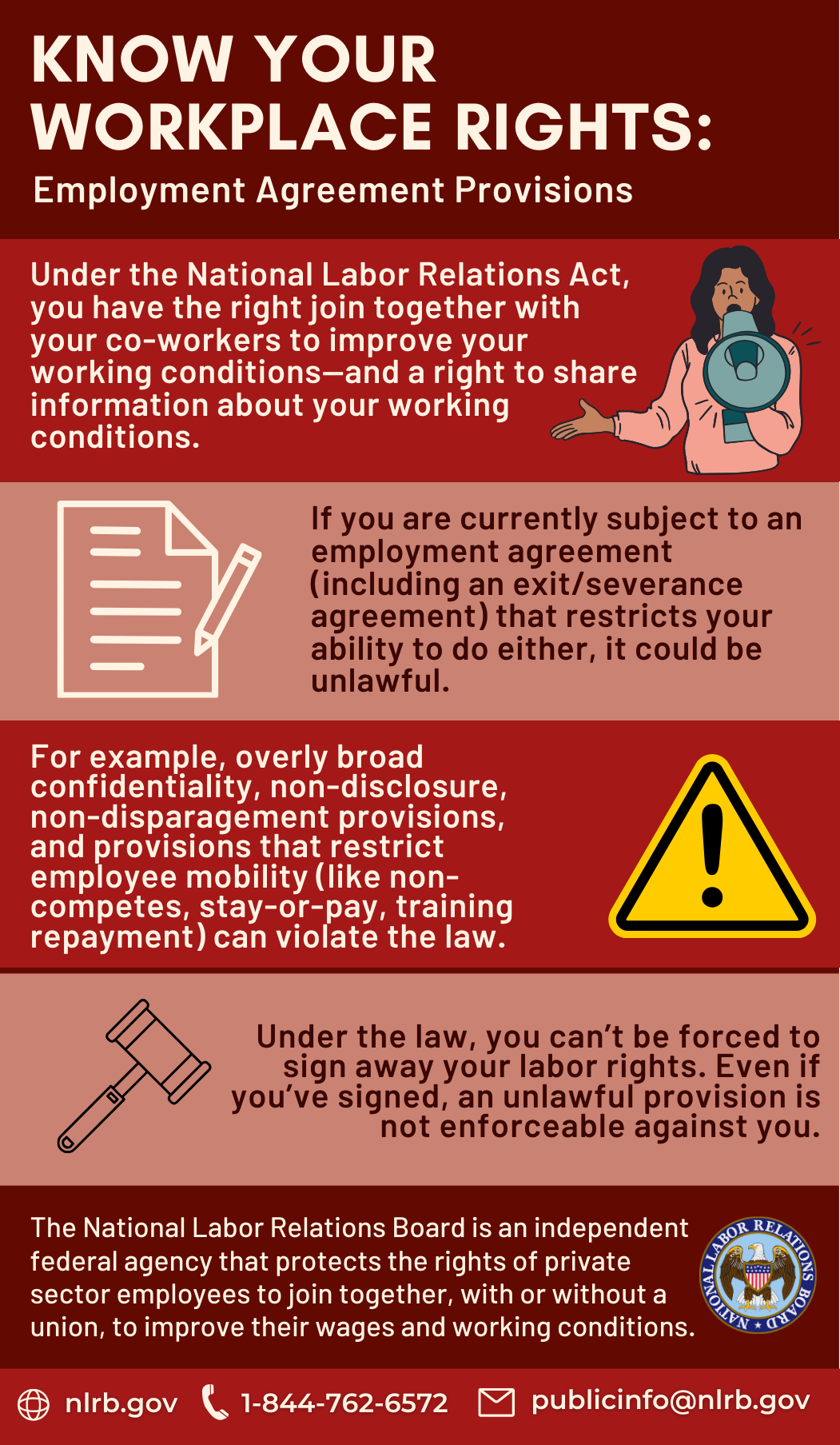

Most American workers are protected by the National Labor Relations Act, passed in 1935. The NLRB enforces it. This law guarantees workers the right to organize, bargain collectively, and engage in protected concerted activity. It's not perfect, and enforcement is notoriously slow, but it exists.

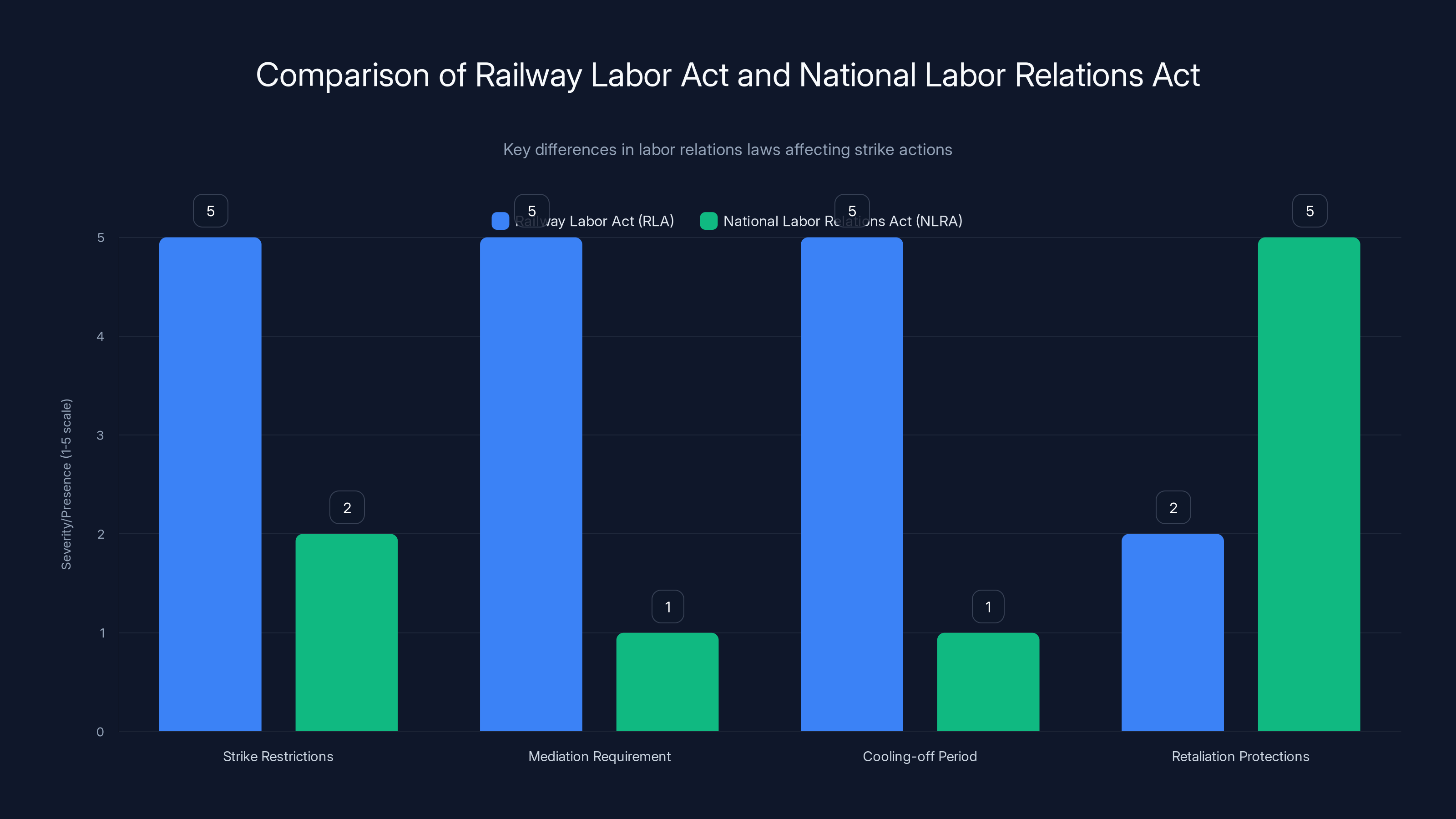

Then there's the Railway Labor Act, passed in 1926—nine years earlier. It was designed specifically for workers in industries the government considered "critical infrastructure" such as railroads and airlines. Industries where labor disputes could theoretically cripple essential services.

On paper, these two frameworks sound similar. Both protect workers. Both address labor disputes. But the actual mechanics are dramatically different.

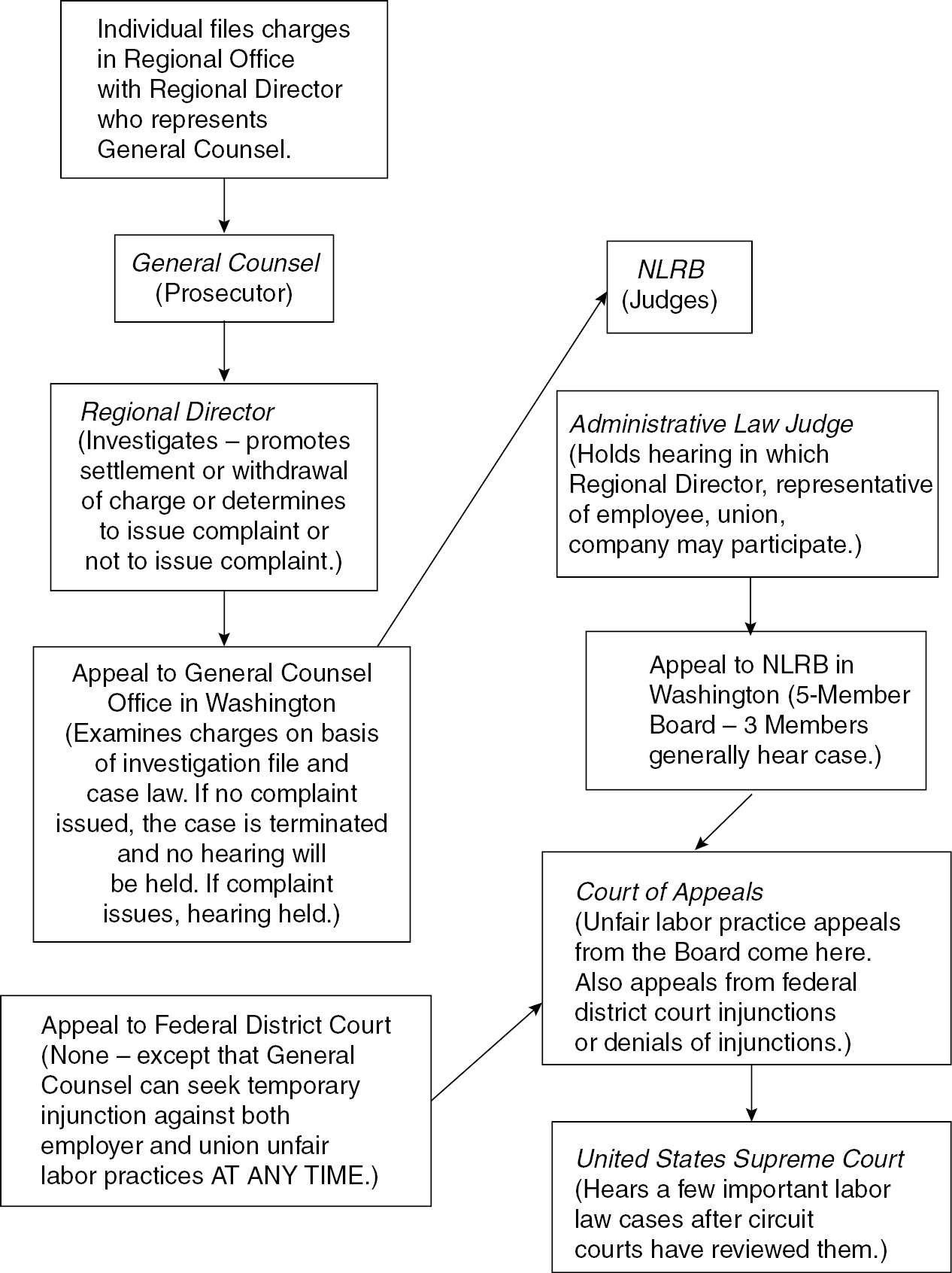

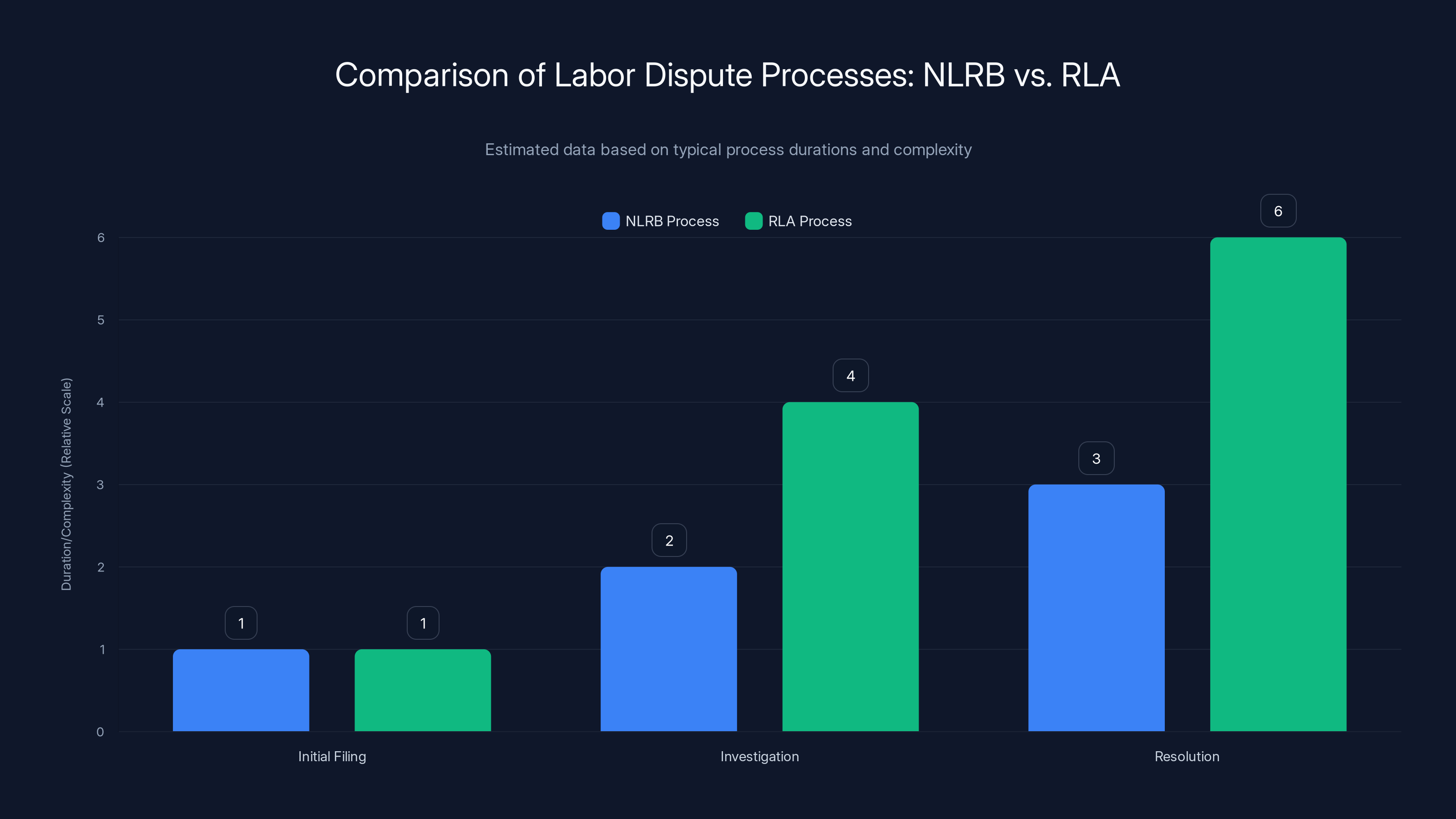

Under the NLRB system, workers have relatively straightforward remedies. They file a charge. An NLRB investigator looks into it. If the investigation finds merit, the NLRB prosecutes the case. If the company loses, remedies can include back pay, reinstatement, or posting notices acknowledging the violation. The process takes years, but it exists.

Under the Railway Labor Act, the National Mediation Board (NMB) handles disputes, but the process is far more labyrinthine. Before employees can strike, they must go through a mandatory 30-day cooling-off period. Then mediation. Then fact-finding. Then more waiting. The whole process can stretch on for months or years. It's designed to make strikes so difficult and time-consuming that most workers never attempt them.

Here's what makes this distinction critical: the Railway Labor Act explicitly exempts companies from NLRB jurisdiction. So if you're regulated by the RLA, you lose NLRB protections. Full stop. You don't get both. You get only RLA protections, which are structured very differently.

When Space X was reclassified as a "common carrier by air," the company was moved from one system into the other. The 72-year legal precedent that had applied to Space X employment law disappeared overnight.

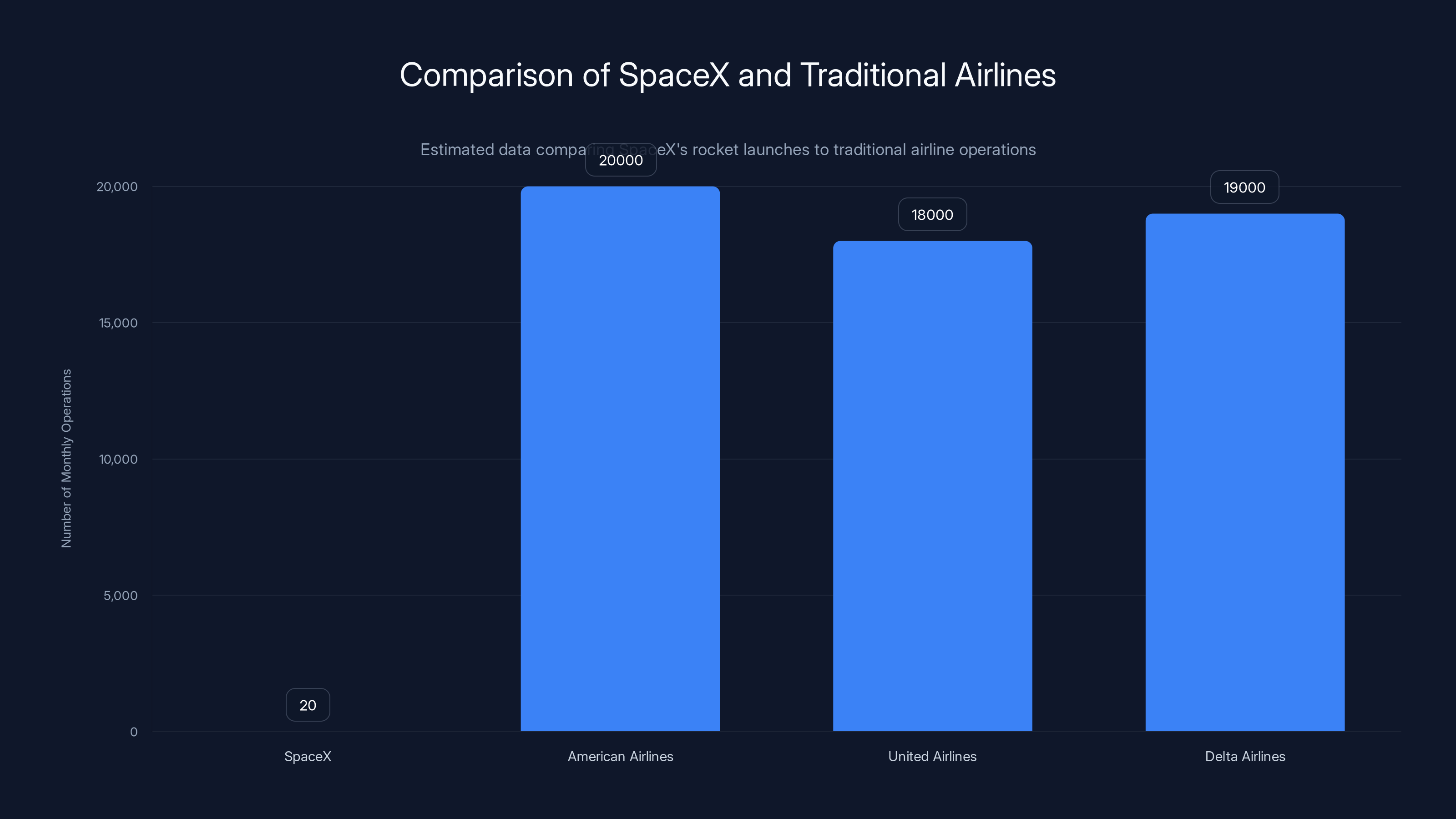

Estimated data shows SpaceX conducts significantly fewer operations monthly compared to traditional airlines, highlighting its distinct operational model.

How Space X Got Here: The Eight Fired Engineers

The story begins in 2022 with eight Space X engineers who were frustrated. They worked at one of the world's most advanced rocket companies, but they were bothered by their CEO's behavior. Elon Musk had recently acquired Twitter (now X), and he was posting constantly about topics ranging from political commentary to casual mockery of critics.

For Space X employees, this became a problem. Musk's public persona was affecting the company's reputation. More importantly, from their perspective, it was affecting their work environment. So they drafted an open letter addressed to leadership. The letter called Musk a "frequent source of embarrassment" and suggested that Space X implement a code of conduct for executive social media activity.

It wasn't a strike. It wasn't a protest. It was literally a letter—a form of communication protected under the NLRB framework as "concerted protected activity." Workers speaking up about workplace concerns have legal protection.

Space X's response was swift. The company fired all eight employees. Management said it was because they violated employment policies around internal communications, but the timing and totality of the action suggested something else: retaliation.

The fired engineers pursued NLRB remedies. In January 2024, an NLRB regional director filed a formal complaint against Space X. The complaint alleged illegal retaliation and sought reinstatement, back pay, and apology letters. This was a procedural victory—the agency was formally saying that Space X had probably violated labor law.

But Space X was playing a longer game.

The NLRB process is relatively straightforward compared to the RLA, which involves multiple stages and can be significantly more time-consuming and complex. Estimated data.

The Jurisdictional Judo Move

Instead of fighting the retaliation charge directly, Space X raised a different issue: the NLRB might not even have authority over the company. Space X argued it was a common carrier—a classification that would put it under RLA jurisdiction instead.

Initially, this argument went nowhere. Jennifer Abruzzo, the NLRB's general counsel under President Biden, rejected Space X's common carrier claim. The legal reasoning was straightforward: Space X doesn't actually operate as a commercial airline. It doesn't sell tickets to the general public. It doesn't follow an airline schedule. It launches government satellites and occasionally takes wealthy passengers on extremely expensive private missions negotiated with individual contracts.

But then political power shifted. In January 2025, Trump took office and immediately fired Abruzzo. Space X, whose CEO is allied with the Trump administration, saw an opportunity. The company asked the labor board to reconsider the common carrier question.

In April 2025, Space X and the NLRB reached an unusual agreement: the NLRB would refer the question to the National Mediation Board for a formal opinion. The joint filing said this was done "in the interests of potentially settling the legal disputes currently pending between the NLRB and Space X on terms mutually agreeable to both parties."

That language is interesting. "Mutually agreeable" suggests both sides wanted the same outcome. This wasn't Space X forcing the issue against NLRB resistance. Both parties seemed to be working toward the same goal.

The NMB took the referral and analyzed Space X's operations. On January 14, 2026, the NMB issued its decision: Space X is a common carrier by air. Therefore, the NMB concluded, Space X falls under RLA jurisdiction.

Within weeks, the NLRB dismissed the retaliation complaint. The eight fired employees would not be getting their jobs back, not through this legal pathway anyway.

Why a Rocket Company Became an "Airline"

The NMB's reasoning rested on a simple but expansive interpretation: Space X operates aircraft (rockets) that transport cargo (satellites and people) across interstate and international commerce. That makes it an air carrier. Airlines are regulated under the RLA. Therefore, Space X is regulated under the RLA.

On one level, this logic is almost tautological. You can make it work if you're willing to stretch the definition of "airline." But stretching definitions in law has consequences.

The Railway Labor Act was written for a specific purpose: to prevent labor disputes from halting railroad or airline service. If airline pilots strike, planes don't fly. If railroad workers strike, supply chains break. Both are critical infrastructure. The government wants to regulate labor disputes in these sectors more strictly than in others.

But does Space X fit that description? Space X launches about 20 rockets per month on average. It's not running a daily schedule like American Airlines or United. It's not a backbone of American transportation infrastructure. The company primarily launches government satellites and contracts for specific missions.

The lawyers representing the fired Space X employees made exactly this argument in filings with the NMB. They pointed out that Space X's entire human spaceflight operation has served just a handful of private passengers. Besides government-contracted astronaut flights to the International Space Station, Space X has sent private passengers on only two missions—both for extremely wealthy individuals who negotiated specific contracts.

They also noted that Space X had redacted pricing information from the marketing materials it submitted to the NMB. If Space X really operated as a common carrier open to the public, why would it hide pricing? Common carriers publish their rates.

But these arguments didn't sway the NMB. The agency issued its decision and essentially closed the door. One agency had deferred to another. Jurisdictional questions had been answered. The NLRB had no choice but to step back.

What made this possible was the same political reality that had changed the NLRB's leadership. The Trump administration views Elon Musk as an ally. Musk owns X (formerly Twitter), which he uses to support Trump's political agenda. Musk also committed to serving in Trump's administration (though he eventually withdrew from a formal role). In this environment, aggressive labor enforcement against Space X became unlikely.

The Railway Labor Act imposes stricter strike restrictions and mediation requirements compared to the National Labor Relations Act, which offers more direct paths to strike and stronger retaliation protections. Estimated data based on qualitative descriptions.

The Journey from NLRB to NMB Jurisdiction

Understanding how Space X moved from one regulatory regime to another requires understanding an unusual feature of American labor law: jurisdictional deference.

Both the NLRB and the NMB can claim authority over certain cases. When there's ambiguity about which agency should handle something, federal law creates a process for determining jurisdiction. The agencies consult with each other. Sometimes one defers to the other.

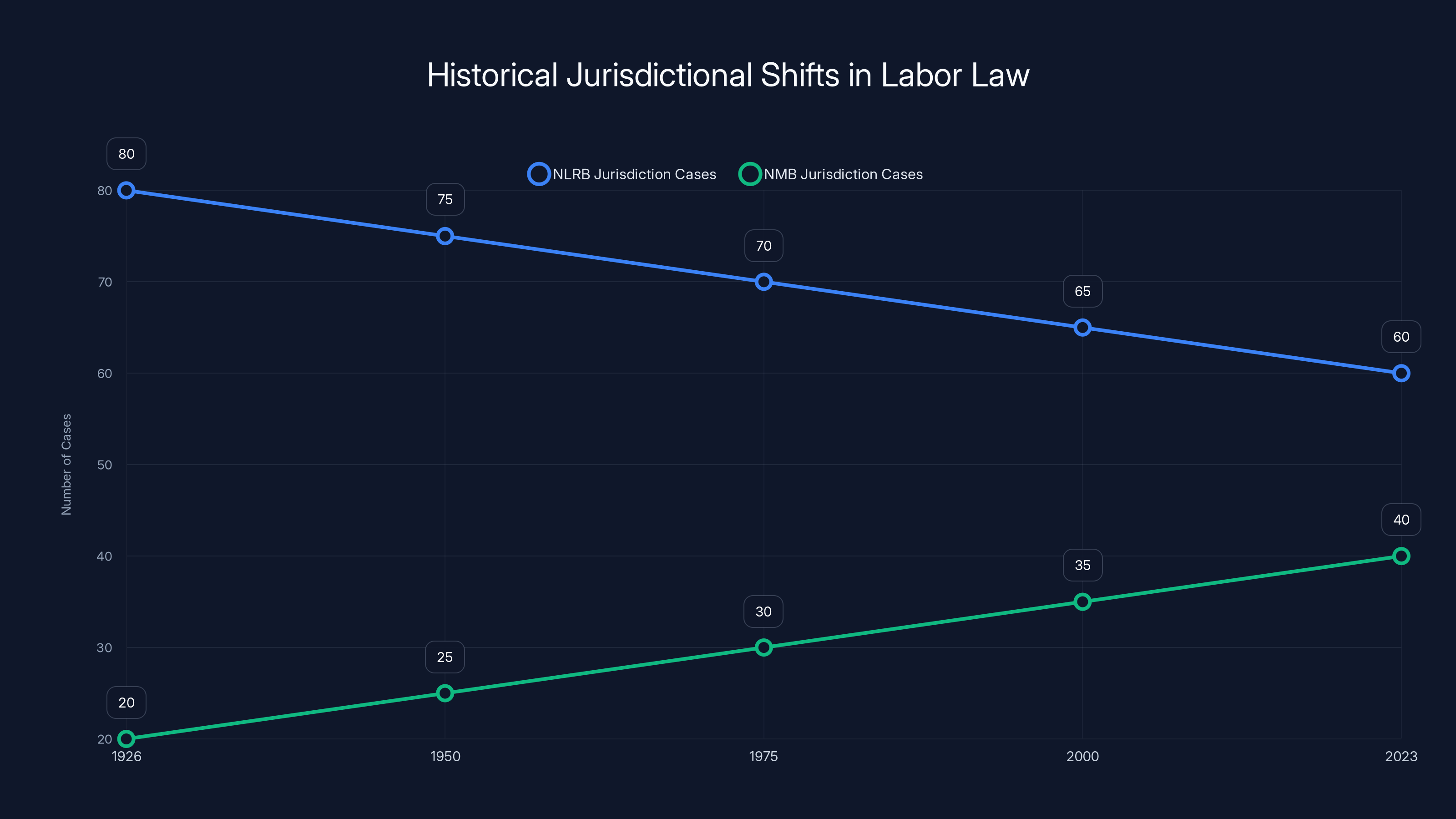

This process has been used historically to sort out which companies legitimately fall under the Railway Labor Act. The problem is that the Railway Labor Act was written in 1926, and it uses somewhat vague language about "carriers by air." Does that mean any company that operates aircraft? Just commercial airlines? Airlines that carry passengers?

Historically, the NMB had been conservative about expanding RLA coverage. The agency generally limited it to companies that operated scheduled air service or railroad operations—things that genuinely qualified as common carriers under traditional definitions.

But the NMB's decision on Space X suggested a new openness to broader interpretations. The agency decided that any company operating aircraft in interstate or international commerce could qualify, even if it doesn't follow a published schedule and doesn't open operations to the general public.

This interpretive shift has potential implications far beyond Space X. If the definition of "common carrier by air" expands to include any company with aircraft, other companies might try the same argument. Blue Origin, Amazon's Kuiper satellite initiative, Virgin Orbit before it shut down—these could potentially make similar claims.

Moreover, the process itself is worth examining. The NLRB, which had been defending its jurisdiction, essentially agreed to ask another agency whether it should keep the case. Then that other agency decided the NLRB shouldn't have it. The whole thing took place with relatively little public attention or comment.

What Changed When Space X Changed Categories

Most Space X employees are not lawyers. They don't read NMB decisions. But the practical impacts of Space X's reclassification are significant and immediate.

Under the NLRB system, if a Space X employee is fired for criticizing management, they can file an unfair labor practice charge. The NLRB investigates. If the NLRB believes retaliation occurred, it prosecutes the case. The employee has some legal recourse.

Under the RLA system, that same employee would need to file a complaint with the NMB. The NMB would attempt mediation. If mediation fails, there's a fact-finding process. But here's the catch: individual employee complaints are handled differently under RLA than under NLRA. The RLA is structured primarily around disputes between unions and management at the bargaining table level. Individual employee protections are less robust.

Moreover, the Railway Labor Act has extremely restrictive rules about strikes. Before a strike can happen, workers must exhaust a 30-day mediation period, then a fact-finding period, then a 60-day presidential cooling-off period. The whole process can take months. It's designed to make strikes so difficult that they rarely happen.

This is why labor advocates and the fired Space X employees' attorneys have been so alarmed. The reclassification doesn't just affect how cases are processed. It fundamentally changes the balance of power between workers and management.

At most American companies, workers can engage in what's called "protected concerted activity." If workers protest wages, safety conditions, or management behavior, that's protected. Employers can't retaliate. The protection is relatively straightforward.

Under the Railway Labor Act, workers in covered industries have weaker individual protections. They have union protections (if unionized), but the system assumes labor is organized. Space X has no unions. So workers at Space X now have fewer explicit protections than they did before the reclassification.

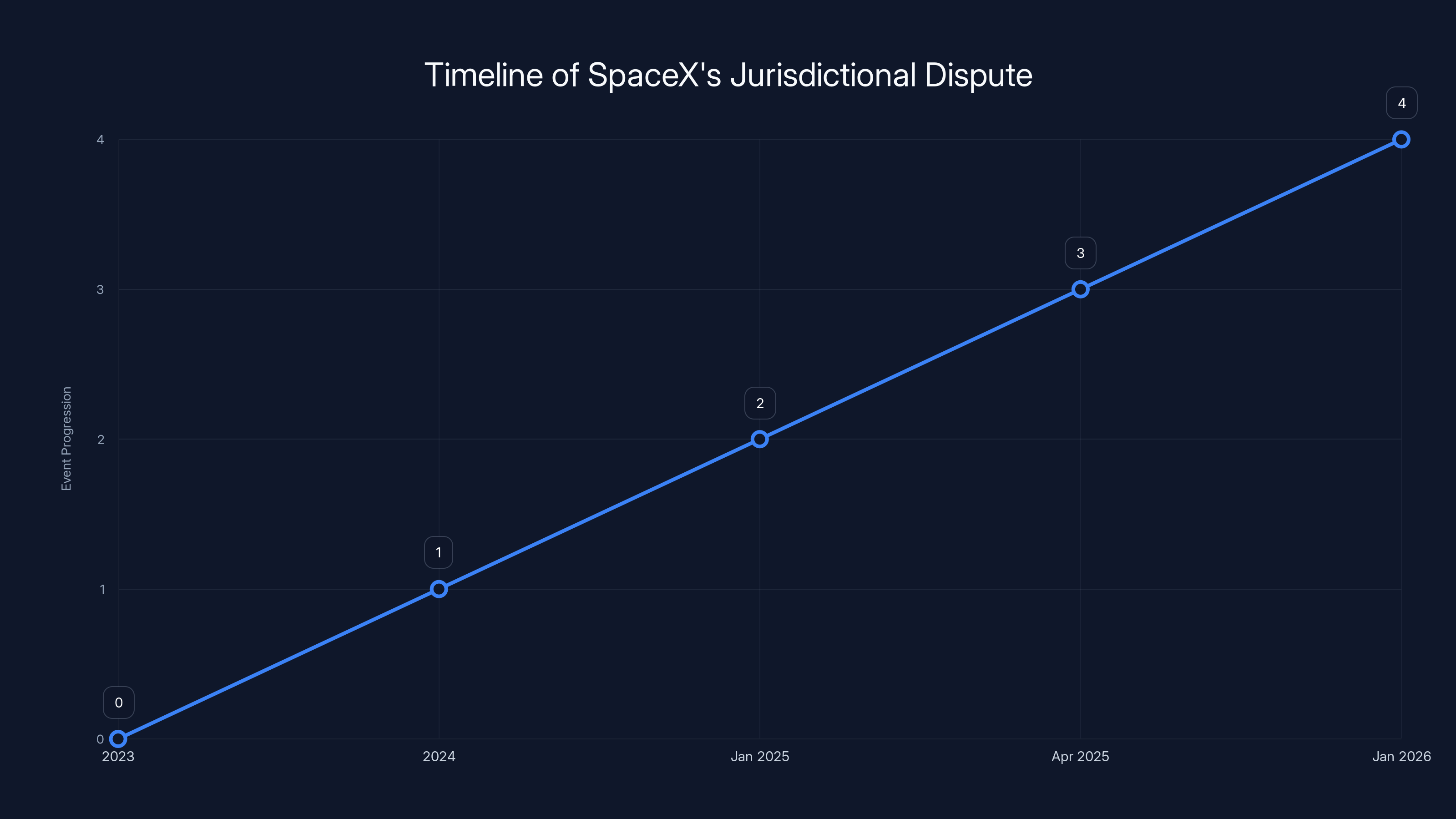

Estimated data shows a gradual increase in NMB jurisdiction cases over time, suggesting a shift towards broader interpretations of the Railway Labor Act.

The Eight Engineers and What Happens to Them

The eight Space X engineers who were fired for their letter had their NLRB complaints dismissed. They're not getting their jobs back through that legal pathway. But their situation illustrates something important about how regulatory decisions affect real people.

These were experienced engineers working at one of the world's most advanced aerospace companies. They weren't trying to unionize. They weren't demanding higher pay (at least not in their public letter). They were expressing a concern about leadership behavior and its impact on the company's reputation.

Their firing sent a message: don't speak up. Even if you think you have legal protections, those protections can disappear if the regulatory landscape shifts.

For Space X, the message was different: you can fire people for criticizing the CEO without fear of NLRB consequences. The regulatory risk has been substantially reduced.

This matters because company culture flows from incentives. When managers know that retaliation against whistleblowers will be difficult to prosecute, more retaliation happens. When employees know they can't rely on regulatory protection, fewer of them speak up about problems.

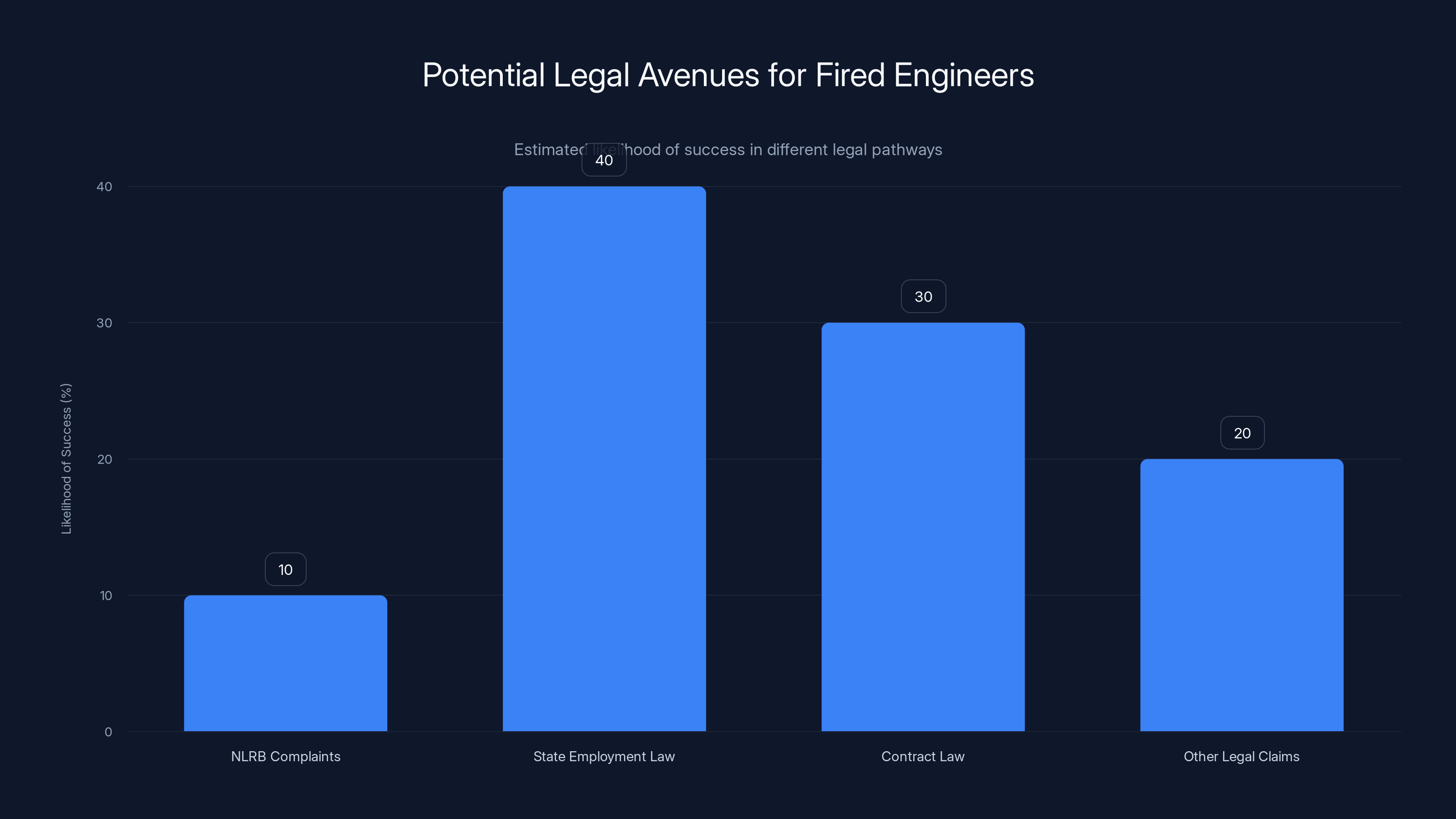

The eight engineers could still pursue other legal claims. They might have claims under state employment law or contract law. But the powerful federal labor protections that existed are gone. And that's a significant loss.

The Broader Political Context

Space X's regulatory reclassification didn't happen in a vacuum. It happened in a specific political moment.

Elon Musk is one of the world's most politically connected billionaires. He owns X, which has enormous influence over political discourse. He has a direct relationship with the Trump administration. Trump appointed him to head the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), though that role was eventually abandoned.

Meanwhile, the NLRB has gone through dramatic leadership changes. Under Biden, Abruzzo was appointed as general counsel and took an aggressive stance on labor enforcement, including against Elon Musk's companies. Under Trump, she was fired and replaced with more employer-friendly appointees.

This isn't to say the decision on Space X was purely political. The legal arguments exist and were analyzed. But the timing, the receptiveness to new interpretations, and the coordinated process between agencies all reflect a political environment favorable to Space X's interests.

It's worth noting: if the political winds shift again, this decision might eventually be challenged or revisited. Future administrations might appoint different leaders to the NMB or NLRB. But for now, Space X has achieved something that would have seemed impossible under the previous administration: a comprehensive exemption from aggressive labor board oversight.

The timeline illustrates SpaceX's strategic legal maneuvers to shift jurisdiction from the NLRB to the NMB, culminating in a favorable decision in 2026.

What the Reclassification Means for Space X's Future

For Space X, this decision provides tremendous operational flexibility. The company can discipline or terminate employees who engage in protected concerted activity without fear of NLRB retaliation claims. The company can more aggressively enforce internal communication policies. The company can make decisions about wages, working conditions, and management structure with less regulatory risk.

This matters for a company like Space X because the aerospace industry is notoriously demanding. Rockets are complex machines. Failures can cost billions of dollars. Space X's management culture emphasizes speed, intensity, and alignment around company goals. When you're trying to build rockets cheaper and faster than competitors, you don't want what you perceive as excessive regulation of employment practices.

From management's perspective, the RLA reclassification eliminates one significant regulatory constraint. It doesn't eliminate all constraints—Space X still has to follow labor laws in various respects, and it still has to comply with federal safety regulations. But the specific risk of NLRB retaliation claims has been substantially reduced.

For the space industry more broadly, the decision sends a signal. If Space X can be reclassified as a common carrier and escape NLRB jurisdiction, other aerospace companies might try the same argument. Blue Origin, which also operates rockets and is expanding its commercial spaceflight operations, might claim common carrier status. Smaller space companies might argue they should be treated the same way.

If this interpretation of the Railway Labor Act expands across the aerospace industry, you could see a wholesale shift in labor law coverage for an entire sector. Companies that were previously regulated under the NLRB would move to RLA jurisdiction. Workers in these companies would lose NLRB protections and gain RLA protections instead. For labor advocates, this would represent a significant retreat.

The Legal Arguments: Was the Decision Correct?

Legal scholars and labor law experts have sharply disagreed about whether the NMB's decision was correct.

The employees' attorneys argued that Space X simply doesn't meet the definition of a common carrier. A common carrier, they argued, offers services to the general public at published rates on regular schedules. Space X does none of these things. Space X launches satellites for government contracts and occasionally takes private passengers on custom-negotiated missions. That's not common carrier service.

Moreover, the employees' attorneys pointed out that the Railway Labor Act was designed for industries where labor disputes could affect essential infrastructure. Space X operates satellites and conducts space missions. Important, but not essential infrastructure in the same way that airline passenger service or railroad freight transport is.

The NMB's counterargument was simpler: Space X operates aircraft in interstate and international commerce. The Railway Labor Act covers carriers by air. Therefore, Space X is a common carrier.

This interpretation is broader than previous NMB decisions. Historically, the NMB had been reluctant to expand RLA coverage beyond traditional airline and railroad operations. But the NMB's 2026 decision suggests a willingness to apply the law more expansively.

From a legal perspective, the NMB's decision is vulnerable to challenge. If the fired Space X employees appeal this decision, they could argue that the NMB's interpretation of "common carrier" is too broad and inconsistent with the Railway Labor Act's statutory language and purpose. However, challenging agency interpretations is difficult. Courts defer to agency expertise. Overturning the NMB's decision would require showing that the interpretation is unreasonable, not just that you disagree with it.

The employees' case would also be complicated by the fact that the NLRB and NMB coordinated on the referral. If both agencies agreed on the outcome, it's hard to argue that the process was corrupted. The fact that the NLRB voluntarily asked the NMB to make a jurisdictional determination gives the outcome more legitimacy, even if you think the interpretation is wrong.

Estimated data suggests that while NLRB complaints were dismissed, state employment law and contract law may offer more viable legal avenues for the engineers.

Why This Matters Beyond Space X

This case is important beyond just Space X and its employees because it illustrates how regulatory authority works in America. Agencies interpret statutes. Agencies apply those interpretations to specific cases. Agencies sometimes defer to each other when jurisdiction is unclear.

But when agencies are led by appointees who have political preferences—preferences that align with particular companies or industries—those interpretations can shift. The railway Labor Act hasn't changed. Congress didn't pass new legislation. But the interpretation of who falls under the Railway Labor Act's coverage has effectively expanded.

This has happened before. Regulatory interpretation shifts whenever there's a change in administration. New appointees bring different philosophies. They interpret ambiguous statutes differently. They prioritize different enforcement goals.

What makes the Space X case notable is how cleanly it shows this process in action. The NLRB was pursuing a retaliation claim. Space X wanted to escape NLRB jurisdiction. Political power shifted. The agencies coordinated. A new interpretation was issued. The problem disappeared.

For workers, this illustrates a vulnerability in the American labor system. Your legal protections depend partly on which agencies are interpreting the law and what political appointees lead those agencies. If the political wind changes, your protections might change too.

For companies, the message is different. Strategic regulatory navigation—positioning yourself within jurisdictional frameworks to minimize oversight—is possible. It's not always easy, but it's possible if you have sufficient political influence and legal sophistication.

The Precedent for Other Companies

The Space X decision will likely be invoked by other companies seeking to escape NLRB jurisdiction. Any company that operates aircraft or claims to be in the transportation business can now point to the Space X precedent and argue for RLA coverage.

Blue Origin, Amazon's Kuiper constellation (which will eventually have launch services), Virgin Orbit (if revived), Relativity Space, and other aerospace companies could make similar arguments. If the interpretation holds, the space industry could largely transition to RLA jurisdiction.

But the precedent might also extend beyond aerospace. Any company that claims to operate vehicles in interstate commerce might argue for RLA coverage. This could affect logistics companies, shipping companies, or any business that transports goods or people.

However, the NMB would likely push back on truly broad interpretations. The agency has historical experience with RLA coverage and would probably resist applying it to companies that are obviously not in the traditional airline or railroad business. But on the margins, in industries that plausibly claim to be in the transportation or carrier business, the precedent creates vulnerability.

This is why labor advocates view the Space X decision as potentially dangerous. It's not just about Space X. It's about establishing a precedent that could gradually expand RLA coverage and reduce NLRB jurisdiction across multiple industries.

What Could Reverse This Decision

Several things could potentially reverse or limit the Space X decision.

First, future NMB appointees could interpret the Railway Labor Act differently. If there's a change in administration, and new NMB leaders decide that the Space X interpretation was too broad, they could issue a contrary decision on a similar company. The precedent isn't necessarily permanent.

Second, Congress could clarify the Railway Labor Act's scope through legislation. If lawmakers decide that the statute was being misinterpreted, they could pass a bill explicitly stating that the RLA doesn't cover companies like Space X. This is unlikely in the current political environment, but it's possible.

Third, the fired Space X employees could pursue legal challenges through other means. They could file federal court cases challenging the NMB's interpretation. They could argue that the NMB's decision was arbitrary or capricious. They could argue that the statutory interpretation violates the Administrative Procedure Act. These challenges would face significant hurdles, but they're theoretically possible.

Fourth, if labor advocates become politically powerful again, they could push for regulatory action. A future NLRB general counsel could refuse to defer to NMB jurisdictional claims in similar cases. This would create a conflict between agencies, forcing either internal resolution or potentially congressional intervention.

For now, though, the decision stands. Space X is classified as a common carrier. The NLRB has dismissed its case. The eight fired employees are pursuing other legal avenues, but their NLRB remedies are gone.

Implications for Workers at Space X and Beyond

For Space X employees, the practical implications are significant. If you work at Space X and you want to engage in protected concerted activity—speaking up about wages, working conditions, safety, or management behavior—you're now operating under a different legal framework.

You don't lose all protection. The Railway Labor Act still covers certain activities. But you lose the immediate NLRB remedies that other workers have. You lose the relatively quick investigation and prosecution process. You lose the straightforward protection that other American workers rely on.

This is likely to chill speech and activism at Space X. If employees know that the legal protections they expected are gone, they'll be less likely to speak up. This benefits management but potentially harms the company in other ways. Worker silence doesn't always mean worker contentment. It can mean workers are disengaged, worried, or planning their exit.

For the broader aerospace industry, the implications are also significant. Other companies in the space industry are watching the Space X decision closely. If they can achieve similar RLA classification, they'll have the same labor law advantages. This could gradually shift labor standards across an entire industry.

For the labor movement more broadly, the Space X decision represents a setback. Labor advocates had been pursuing aggressive NLRB enforcement under the Biden administration. The change in administration and the Space X reclassification suggest that era is ending. Labor enforcement is likely to be less aggressive under the current administration, and regulatory victories that seemed solid just months ago are proving vulnerable to political shifts.

The Bigger Picture: Regulatory Power and Political Change

The Space X case illustrates something fundamental about how regulatory power works in America. Regulatory agencies are supposed to be independent and nonpartisan. In theory, they apply law objectively, without regard to political pressure.

In practice, agencies are led by political appointees. Those appointees have political views and political constituencies. When administration changes occur, new appointees bring different priorities. Regulatory interpretation shifts. Enforcement patterns change.

This isn't necessarily corruption or illegality. It's how the system works. But it means your legal protections are less stable than they might appear. A law that protects you can be reinterpreted through administrative action. An agency that was protecting your interests can be staffed with people who prioritize different interests.

Space X benefited from this reality. The company had the political power to influence appointments to relevant agencies. The company had smart lawyers who could exploit jurisdictional ambiguities. And the company had the timing luck of a political shift that was favorable to its interests.

Other companies might not have all three advantages. But the Space X precedent shows that strategic regulatory navigation is possible if you have sufficient sophistication and influence.

For workers, this suggests the importance of seeking legal protections that are robust to political change. Statutory protections codified in law are more stable than regulatory protections based on agency interpretation. Contractual protections negotiated with employers are more stable than protections dependent on which political appointees happen to lead an agency.

But negotiating such protections requires worker power. And worker power is exactly what labor law is supposed to protect and facilitate. When labor law protections erode due to regulatory reinterpretation, it becomes harder for workers to negotiate stronger contractual protections.

It's a vicious cycle. Regulatory protection weakens. Worker power weakens as a result. Contractual protections don't improve because workers lack leverage. The cycle continues.

Space X's reclassification as a common carrier is a victory for the company. But it's also a case study in how regulatory power works, how political change affects law, and how workers can suddenly find themselves with fewer protections than they expected.

What Happens Next

Looking forward, several developments are possible.

The fired Space X employees might appeal the NLRB's decision. They might pursue legal challenges in federal court. They might seek legislative remedies through Congress. But any of these paths would be long and uncertain.

Other companies in the space industry and related sectors will likely test the boundaries of the Space X precedent. Some will try to claim RLA classification. Some will succeed. Some will fail. Over time, a pattern will emerge about how broadly the NMB is willing to expand RLA coverage.

Labor advocates will likely attempt to counter the precedent through political means. If the political environment changes and labor-friendly appointees lead the NLRB or NMB again, they might attempt to limit or overturn the Space X decision.

Congress might eventually act to clarify the Railway Labor Act's scope. But this requires legislative consensus, which is difficult when political parties have divergent views on labor protection.

In the near term, though, Space X has achieved what seemed like a dramatic victory. The company has been exempted from NLRB jurisdiction. Management has been relieved of a significant regulatory constraint. Workers have lost a layer of legal protection they had.

The case demonstrates that regulatory landscape can shift rapidly with political change. It also demonstrates that workers' rights, which might seem stable and secure, can be suddenly reinterpreted through administrative action.

For anyone paying attention to labor law, regulatory power, or the politics of government agencies, the Space X case is an important reminder: the law as applied depends partly on who's in power.

FAQ

What is the Railway Labor Act and how does it differ from the National Labor Relations Act?

The Railway Labor Act is a federal law passed in 1926 that governs labor relations in the railroad and airline industries. The National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) is a broader labor law passed in 1935 that covers most American workers. The key difference is that the RLA has much stricter restrictions on strikes, requiring workers to go through a 30-day mediation period followed by fact-finding and a 60-day presidential cooling-off period before they can legally strike. The NLRA allows workers more direct paths to strike and organize. Workers covered by the RLA lose the protections of the NLRA, including protections against retaliation for protected concerted activity.

Why did the US government classify Space X as a common carrier by air?

The National Mediation Board (NMB) classified Space X as a common carrier because the company operates aircraft (rockets) that transport cargo and people across interstate and international commerce. The NMB interpreted the Railway Labor Act broadly to include any company operating aircraft in interstate or international commerce, not just traditional airlines. The employees' attorneys argued this interpretation was too expansive because Space X doesn't operate scheduled commercial service or genuinely offer services to the general public at published rates.

What were the consequences of Space X's reclassification for the fired employees?

The eight Space X employees who were fired after writing a critical letter about CEO Elon Musk had their National Labor Relations Board complaint dismissed as a result of Space X's reclassification. Under the NLRB, their case would have proceeded with investigation and potential remedies including reinstatement and back pay. Under the Railway Labor Act jurisdiction that now applies, they lose direct NLRB remedies. They could potentially pursue other legal claims, but the powerful federal labor protection they expected is gone.

Could Space X's reclassification affect other aerospace companies?

Yes, absolutely. Blue Origin, Relativity Space, and other aerospace companies could attempt to claim common carrier status based on the Space X precedent. If the National Mediation Board applies the same broad interpretation to these companies, the entire aerospace industry could shift from NLRB to Railway Labor Act jurisdiction. This would significantly change labor law coverage across the sector and reduce worker protections compared to the NLRB framework.

Can the Space X decision be reversed or challenged?

The decision could potentially be reversed through several mechanisms. Future NMB appointees with different interpretations of the law could issue contrary rulings. Congress could pass legislation clarifying that the Railway Labor Act doesn't apply to space companies. The fired employees could pursue federal court challenges arguing the NMB's interpretation was arbitrary or unlawful. However, all of these paths face significant obstacles, and any reversal would require political change or legislative action.

What does "protected concerted activity" mean and how did Space X's reclassification affect it?

Protected concerted activity is when workers engage in group action to address workplace concerns, including writing letters, organizing meetings, or striking. Under the NLRA, workers cannot be fired for protected concerted activity, and employers cannot retaliate against employees for engaging in it. Under the Railway Labor Act, protections for individual protected concerted activity are weaker and more focused on union-related activities. Space X's reclassification means the company now operates under a system with weaker protections against retaliation for worker speech and activism.

How did political change influence Space X's ability to achieve this reclassification?

Political change was crucial. Under the Biden administration, the NLRB's general counsel Jennifer Abruzzo had rejected Space X's common carrier claims. However, when President Trump took office in January 2025 and fired Abruzzo, replacing her with more employer-friendly appointees, Space X asked the labor board to reconsider the issue. The new NLRB leadership agreed to refer the question to the NMB, and the NMB subsequently ruled in Space X's favor. The political shift created the opportunity for regulatory reinterpretation.

What is the significance of the NMB referring the question from the NLRB?

The referral is significant because it shows both agencies working toward the same outcome. Instead of fighting over jurisdiction, the NLRB asked the NMB to decide the question. The joint filing explicitly stated this was done "in the interests of potentially settling the legal disputes currently pending between the NLRB and Space X on terms mutually agreeable to both parties." This suggests both agencies wanted the same result, which raises questions about whether this truly represented independent analysis or reflected political pressures favoring Space X.

What happens to workers who were depending on NLRB protections?

Workers at Space X and potentially other aerospace companies who expected NLRB protections now find themselves under a different legal framework. They still have some legal protections under the Railway Labor Act, but these are structured differently and generally provide less protection for individual employee concerns. This likely chills worker activism and speech, as employees become cautious about whether their expected legal protections are actually available. It also strengthens management's position in labor disputes.

Could this decision lead to other companies claiming common carrier status?

Definitely. Any company that can plausibly argue it operates vehicles or aircraft in interstate commerce might attempt to claim common carrier status and shift from NLRB to RLA jurisdiction. Beyond aerospace, this could potentially affect logistics companies, shipping companies, or other transportation-related businesses. If the NMB continues to apply the same broad interpretation used in the Space X case, the scope of RLA coverage could expand significantly across multiple industries, reducing NLRB jurisdiction and employee protections in these sectors.

Key Takeaways

- SpaceX was reclassified as a common carrier by air and shifted from NLRB to Railway Labor Act jurisdiction, exempting the company from protections for fired employees

- The Railway Labor Act has much more restrictive rules on labor disputes, requiring 30+ days of mediation and cooling-off periods before strikes are legal

- Political change was critical: new Trump administration appointees were more receptive to SpaceX's argument than Biden-era officials had been

- Eight SpaceX employees who were fired for criticizing CEO Elon Musk lost their legal remedies when the NLRB dismissed their retaliation complaint

- The SpaceX precedent could be invoked by other aerospace companies, potentially shifting labor jurisdiction across an entire industry

- Regulatory interpretation can shift dramatically with political change, making worker protections dependent on administrative leadership rather than stable statutory law

Related Articles

- NLRB Drops SpaceX Case: What It Means for Worker Rights [2025]

- How Elon Musk Is Rewriting Founder Power in 2025 [Strategy]

- SpaceX and xAI Merger: Inside Musk's $1.25 Trillion Data Center Gamble [2025]

- SpaceX Acquires xAI: Creating the World's Most Valuable Private Company [2025]

- SpaceX Acquires xAI: Building a 1 Million Satellite AI Powerhouse [2025]

- Epstein's Secret Role in Musk's Tesla Private Deal [2025]

![SpaceX Common Carrier Status: Labor Law Exemption Explained [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/spacex-common-carrier-status-labor-law-exemption-explained-2/image-1-1770842175881.jpg)