Lunar Spacesuits: The Massive Challenges Behind Artemis Missions

When NASA sends astronauts back to the Moon in the coming years, they'll face something that sounds absurd: their spacesuits might actually make the job harder, not easier.

That's not hyperbole. It's what a veteran NASA astronaut recently told a panel of researchers and engineers at the National Academies. Kate Rubins, who spent 300 days in space and conducted four spacewalks outside the International Space Station, delivered a blunt assessment of the new suits being developed for the Artemis program: "I think the suits are better than Apollo, but I don't think they are great right now" as reported by Ars Technica.

This might seem like a small detail in the grand scheme of returning humans to the lunar surface. But it's actually one of the most significant engineering challenges facing NASA's ambitious mission timeline. The suits weigh more than 300 pounds in Earth's gravity, are restrictive in ways that cause physical trauma, and present health risks that simply didn't exist during the Apollo era according to CNN.

Here's what makes this problem so critical: astronauts on the Moon won't just take a quick walk around like the Apollo crews did. They'll spend eight or nine hours a day in these suits, conducting multiple spacewalks while sleep-deprived, exposed to radiation outside Earth's protective magnetosphere, and dealing with abrasive lunar dust that gets into everything. The physical demands are extreme, the environment is hostile, and the tools being designed to protect them may actually be compromising their ability to work effectively as highlighted by Universe Today.

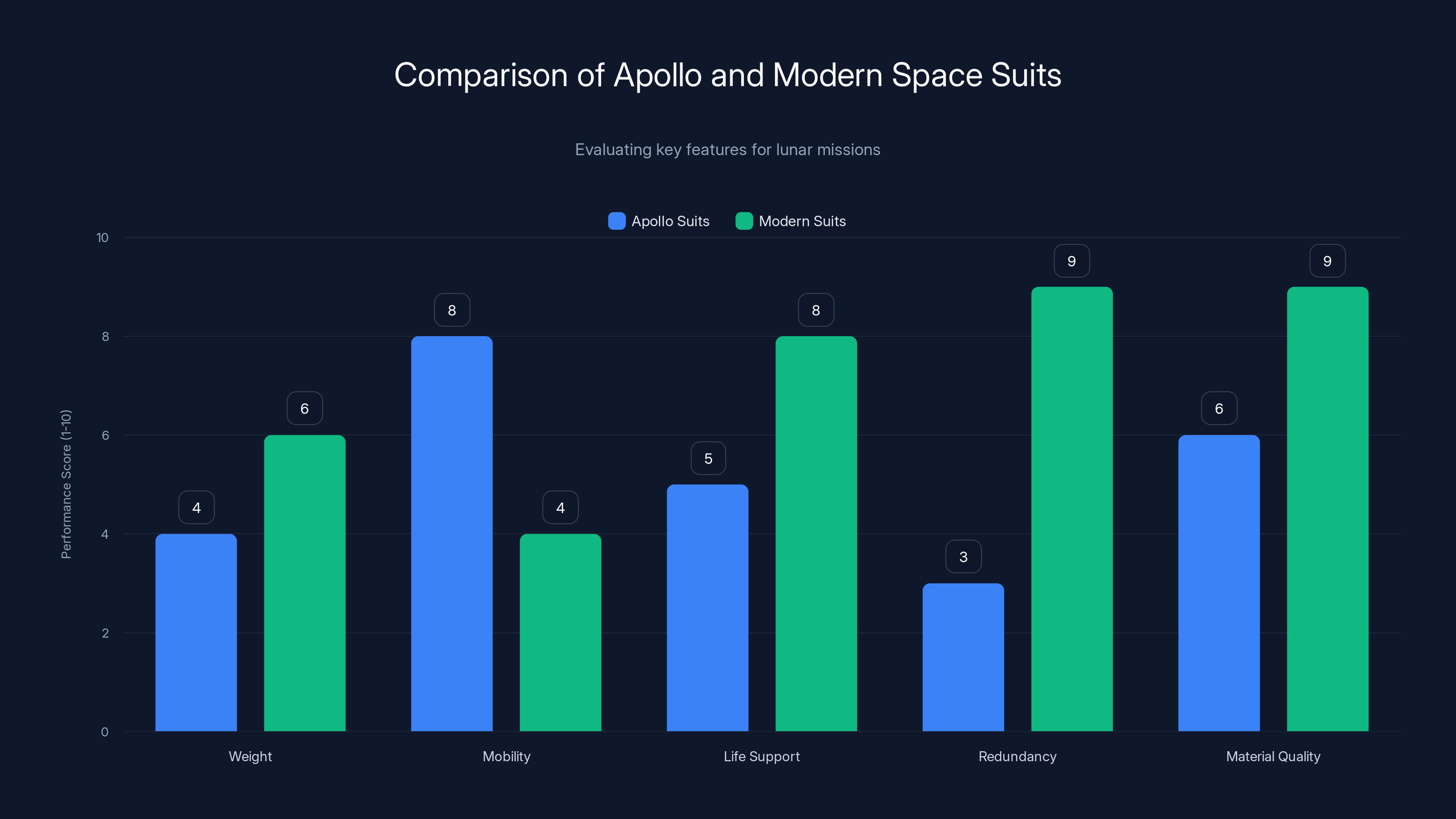

The irony is that decades of technological advancement have actually made spacesuits worse for lunar work. Modern materials, greater redundancy, and extended life support have added weight and complexity. The suits that worked reasonably well on Apollo now seem primitive compared to what we're building for Artemis, yet astronauts who've done spacewalks in both environments say the new suits are exhausting in ways the old ones weren't as noted in Britannica.

This isn't just about comfort. It's about mission success, crew safety, and whether we can actually accomplish what we're setting out to do on the Moon.

TL; DR

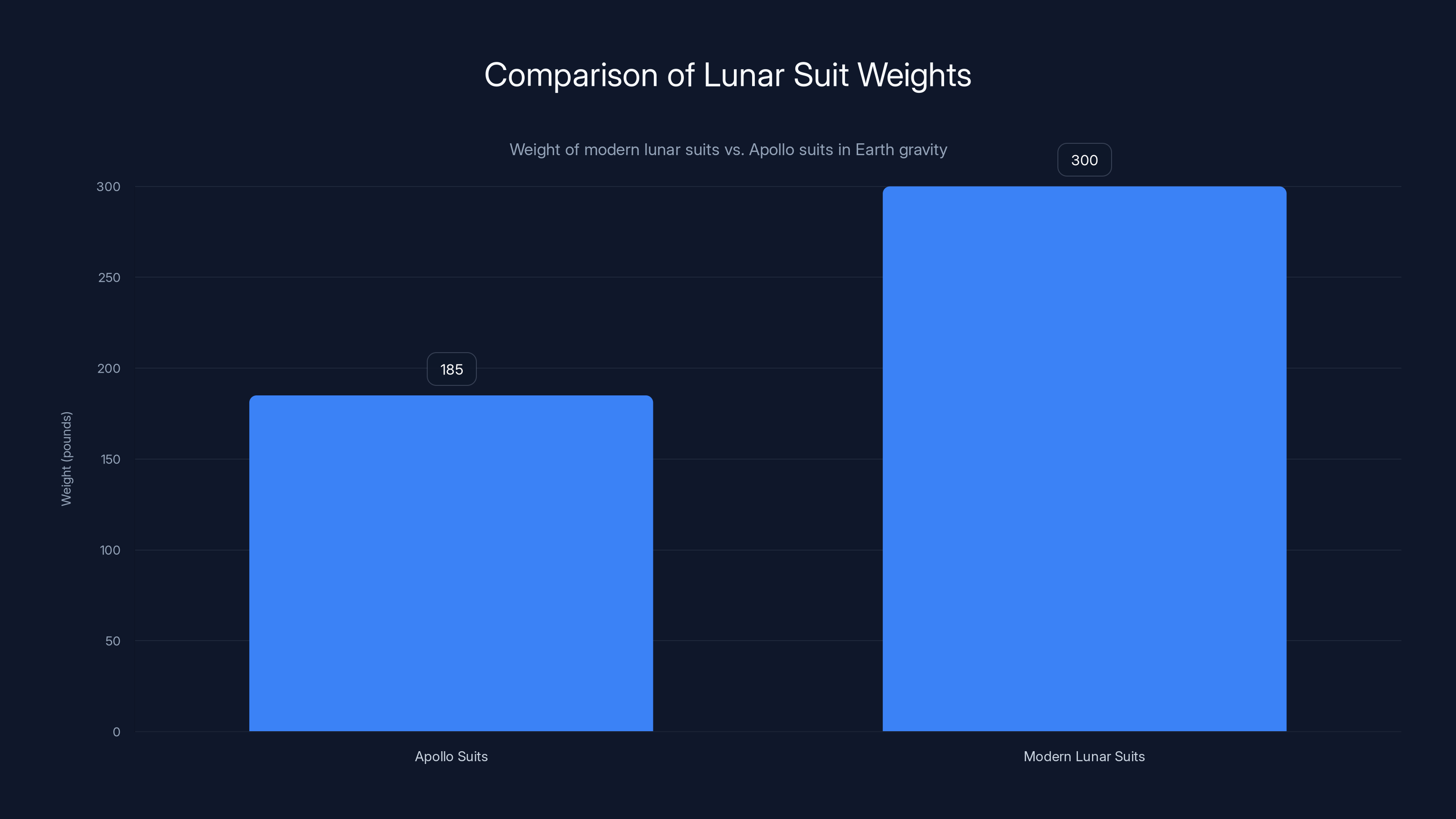

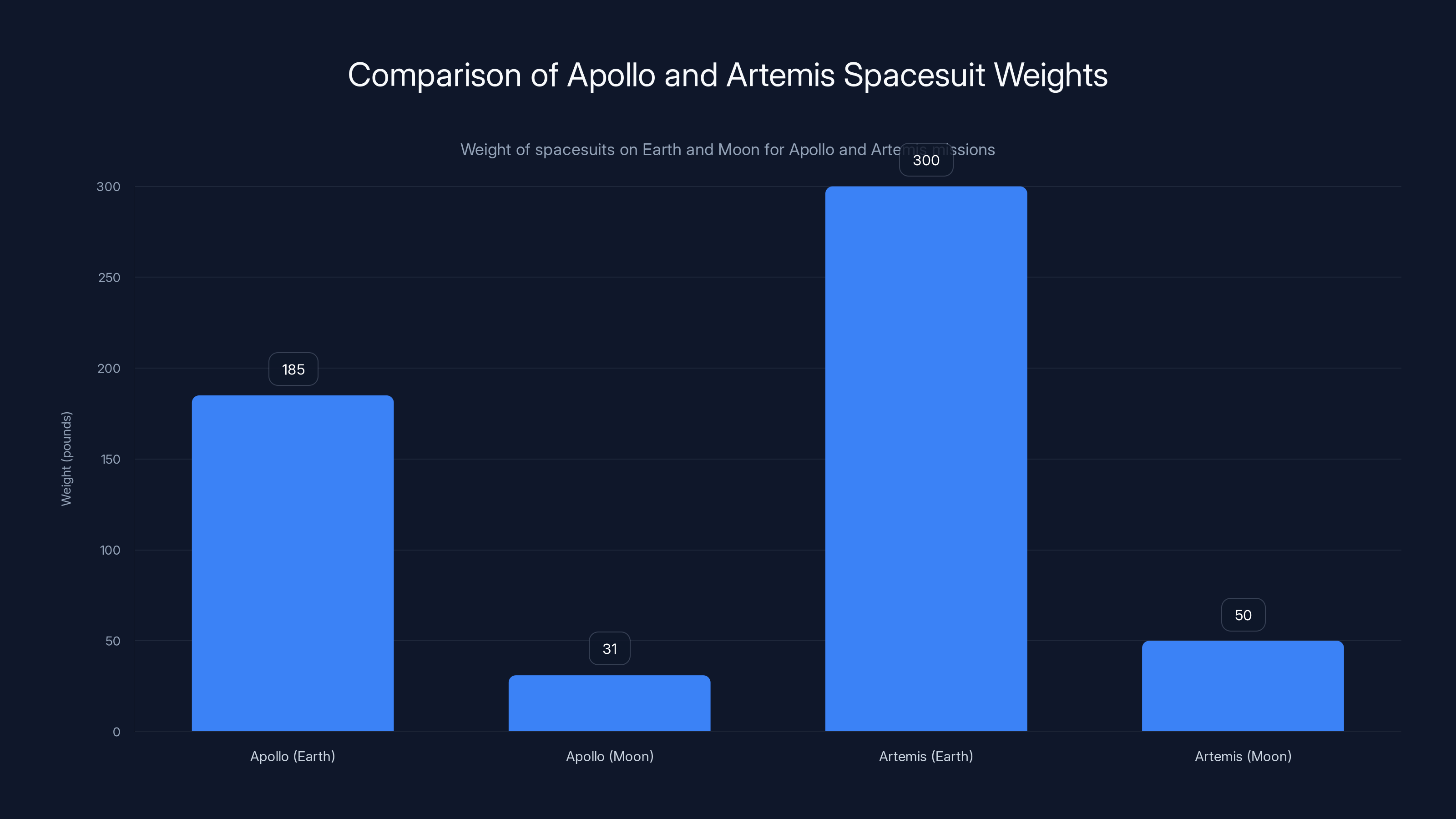

- Modern lunar suits weigh over 300 pounds in Earth gravity compared to Apollo's 185-pound suits, making them significantly heavier despite advanced materials as reported by IBTimes.

- Astronauts report severe physical trauma including skin abrasions, joint pain, orthopedic injuries, and difficulty with basic tasks like bending down to pick up rocks.

- Sleep deprivation and constant EVAs will create an "extreme physical event" for moonwalkers, with 8-9 hour suit operations daily versus relaxed microgravity work on the ISS.

- Axiom Space's $228 million contract is supposed to deliver commercial spacesuits for Artemis III, but design compromises between protection and mobility remain unsolved.

- Lunar environmental factors (radiation, abrasive dust, one-sixth gravity) create challenges that Earth-orbit spacesuits simply weren't designed to handle.

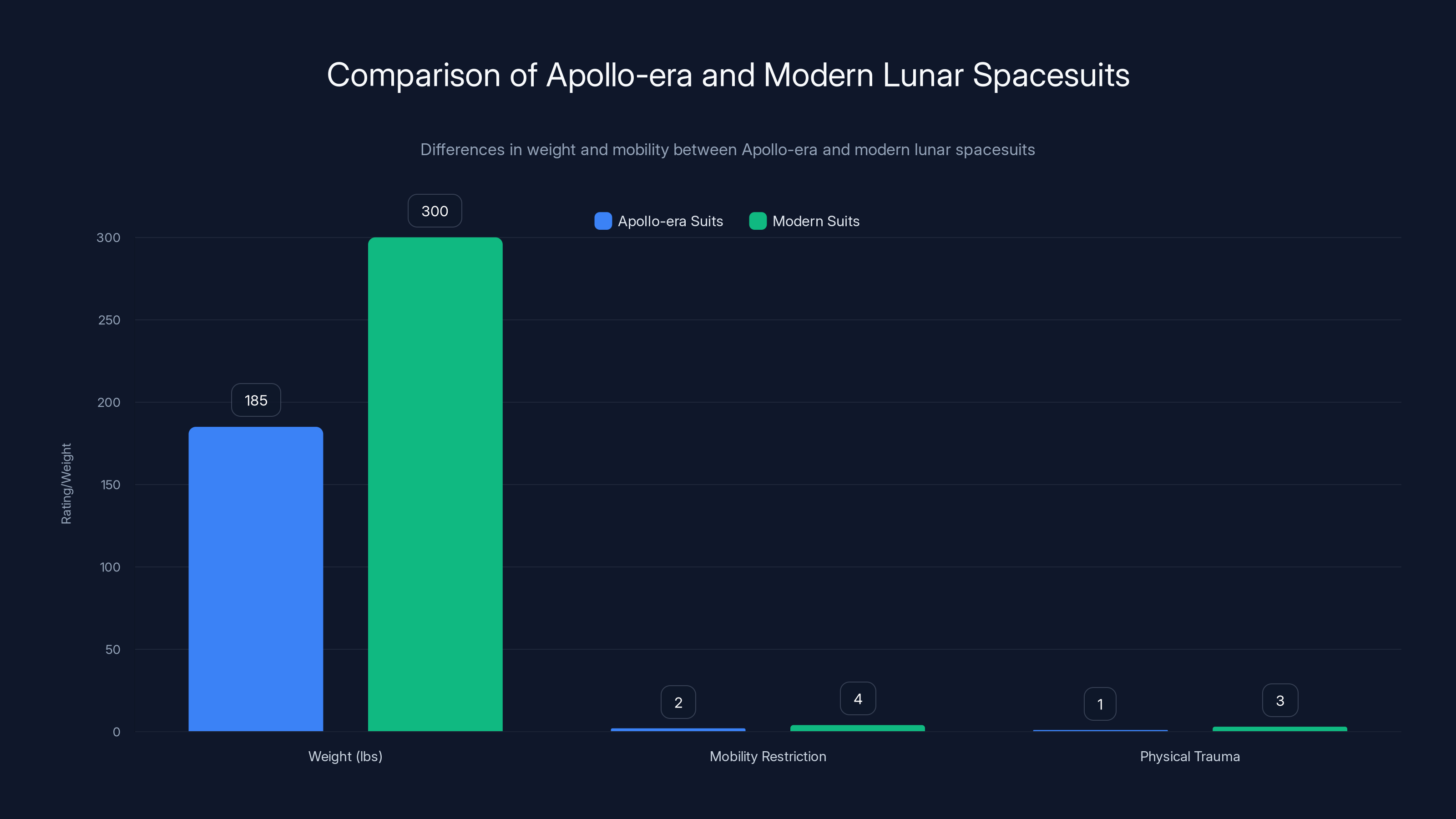

Modern lunar spacesuits are significantly heavier and more restrictive than Apollo-era suits, leading to increased physical trauma. Estimated data for mobility restriction and trauma ratings.

The Apollo Legacy Problem

The Apollo spacesuits have a reputation they probably don't deserve. Most people think of them as crude, primitive technology that somehow worked anyway. They were actually remarkably well-engineered for their specific purpose: brief, low-gravity walks in a relatively benign environment.

Eugene Cernan and Harrison Schmitt logged 22 hours of surface time during Apollo 17. That was a lot for the time, but it was still measured in hours, not days. The suits weighed 185 pounds on Earth (about 31 pounds on the Moon at one-sixth gravity), and they were designed to be worn once and discarded. The astronauts weren't doing strenuous physical labor for extended periods. They were exploring, collecting samples, and taking measurements as detailed by Colombia One.

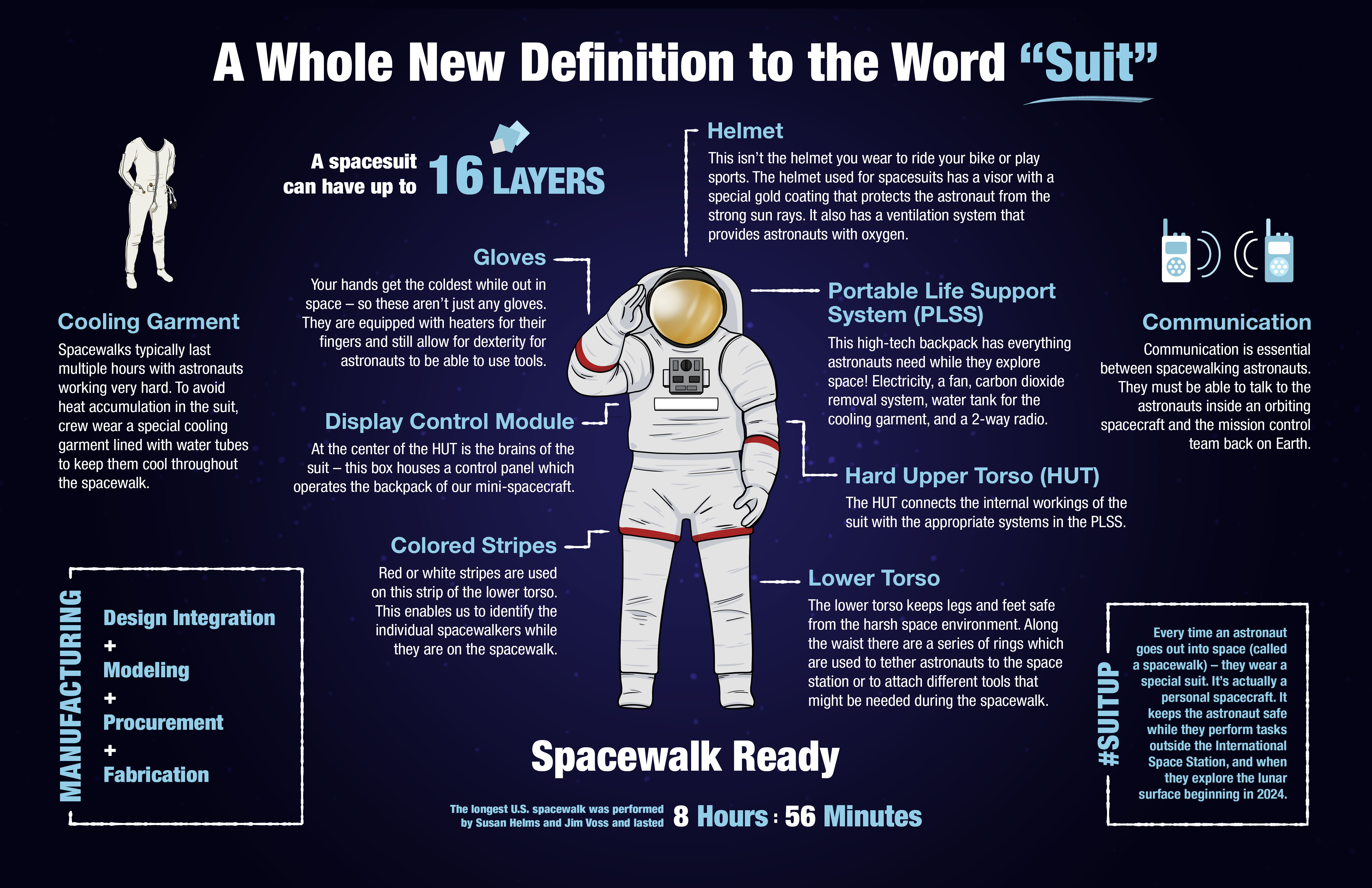

The modern spacesuits being developed for Artemis are fundamentally different beasts. They need to support astronauts who will spend days on the lunar surface, conducting multiple surface excursions, dealing with equipment that needs to be maintained, and performing science experiments that require precision and dexterity. They need greater mobility in the legs and joints because astronauts actually have to walk, crouch, and bend down in lunar gravity. They need more redundant life support systems because a failure would be catastrophic.

All of this adds weight. The Axiom suit weighs more than 300 pounds in Earth's gravity, which translates to about 50 pounds on the Moon. That's roughly 60% heavier than Apollo suits were on the lunar surface. The additional redundancy and capability mean additional mass, and mass is your enemy in spacesuits.

But here's the catch: Apollo astronauts had decades to recover from their physical stress. Modern missions will send astronauts for weeks-long stays. The accumulated physical strain compounds exponentially.

The Real Problem: Physical Trauma from Modern Suits

When Mike Barratt, a NASA astronaut and medical doctor, spoke to the same National Academies panel, he didn't mince words about what spacewalk suits do to the human body. "We've definitely seen trauma from the suits," he said. This includes everything from skin abrasions and joint pain to orthopedic fractures.

You read that right: astronauts have suffered fractures from the physical stress of wearing these suits. Not from impacts or accidents, but from the suits themselves.

The mechanism is straightforward. Modern extravehicular mobility units (EMUs) have rigid sections and flexible joints, but the joints themselves create mechanical stress concentrations. When an astronaut bends a knee or hip inside the suit, they're fighting against both the internal pressure and the suit's mechanical structure. The suit doesn't bend naturally. It resists, forcing the astronaut to strain harder. Do this for seven or eight hours, add the metabolic stress of doing physical work, and injuries accumulate.

There's also the center-of-gravity problem that Rubins mentioned. The suit is designed to keep the astronaut alive, and the life-support backpack is heavy. When you're wearing it, your center of gravity shifts behind where it naturally is. On Earth, this is annoying. On the Moon, in one-sixth gravity, it becomes a significant fall risk. Rubins bluntly stated: "People are going to be falling over."

Falling in a 300-pound spacesuit, even in one-sixth gravity, isn't just an embarrassment. A hard fall could puncture the suit, break equipment, or injure the astronaut. The suit that's supposed to protect you becomes a liability because you can't control your own balance properly.

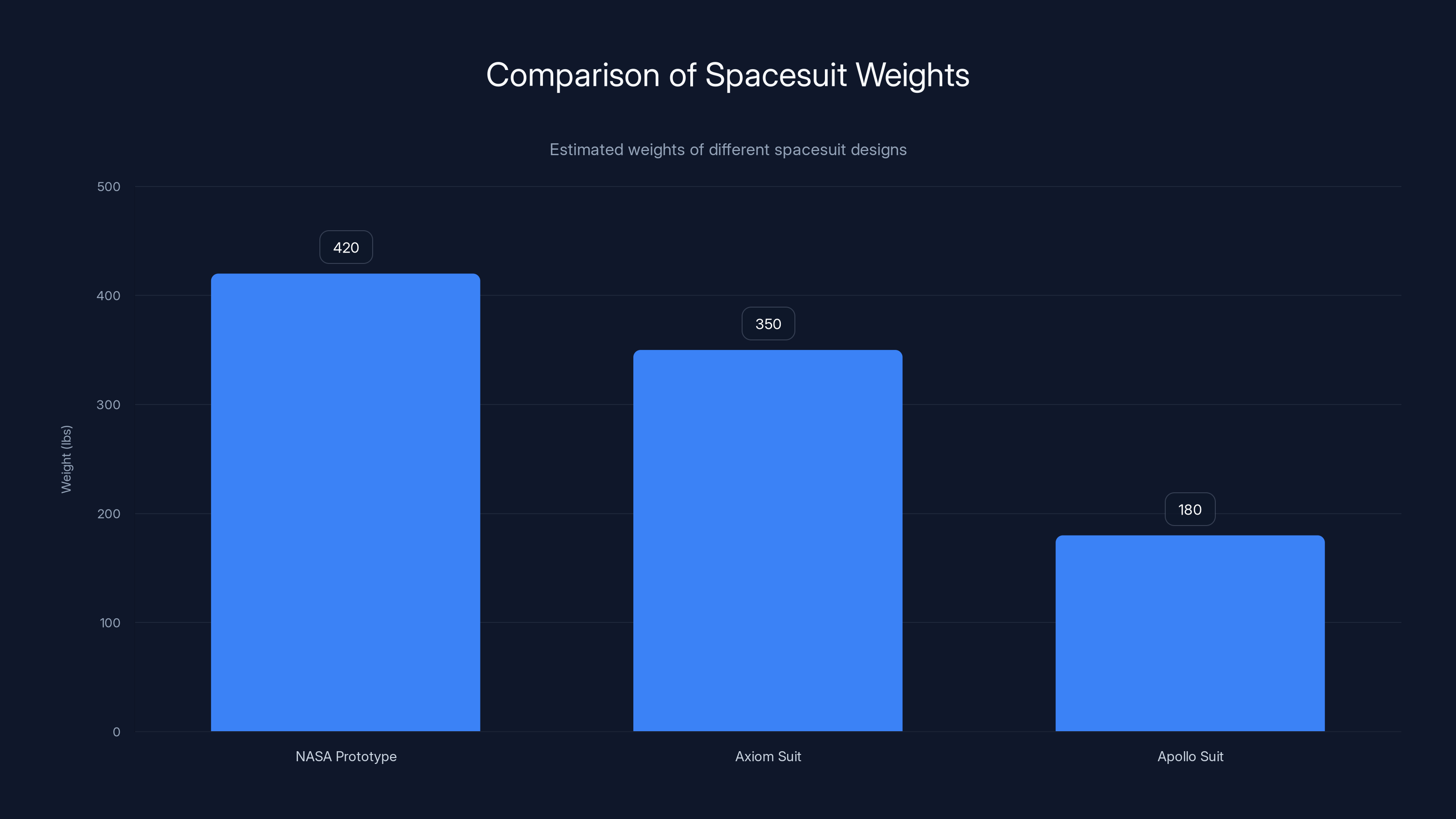

The Axiom suit improves on NASA's prototype designs by being somewhat lighter (the prototype was estimated at over 400 pounds), but it's still a compromise. The engineers have to balance protection, redundancy, mobility, and weight. Right now, that balance tips toward protection and redundancy at the cost of usability.

The Axiom spacesuit is lighter than NASA's prototype but heavier than the Apollo suit. Estimated data based on typical design improvements.

One-Sixth Gravity Changes Everything

The International Space Station exists in microgravity. Astronauts float. They don't have to support their own weight or the weight of tools. This fundamentally changes how spacesuits work and what they need to do.

On the Moon, there's gravity. It's weak compared to Earth, but it's real. That 300-pound suit, while only 50 pounds on the lunar surface, still needs to be supported by your body. You have to carry tools, walk across irregular terrain, and maintain your balance. The suit that works reasonably well in microgravity becomes a burden in partial gravity.

Lunar terrain is also different. It's not flat. It's full of rocks, craters, and slopes. Astronauts need to be able to navigate this terrain safely while wearing a suit that makes rapid movements difficult and throws off their balance. This is why Rubins emphasized that moonwalks will be "even more challenging" than ISS spacewalks, despite the benefit of having gravity to help orient you.

There's also the fact that you can't just take the suit off if it's uncomfortable. You're dependent on it for survival. The psychological stress of being trapped in a suit that's restricting your movement and causing physical pain, all while you're in an environment that will kill you in seconds without protection, adds another layer of difficulty.

The reduced gravity also means that the pressure differential between inside and outside the suit is the same, but it feels more restrictive because you're trying to do work in a gravity field. On the ISS, the zero gravity helps mitigate the suit's stiffness. On the Moon, there's no such compensation.

Sleep Deprivation and the "Extreme Physical Event"

Here's something that doesn't get discussed enough when people talk about Artemis missions: the astronauts won't be sleeping much.

Rubins described the timeline bluntly: "People are going to be sleep shifting. They're barely going to get any sleep. They're going to be in these suits for eight or nine hours. They're going to be doing EVAs every day."

Think about what that means. On the ISS, spacewalks happen maybe once or twice a week. Astronauts do EVAs, and then they have days or weeks to recover. They eat well, sleep normally, and exercise. The suit work is hard, but it's punctuated by rest.

On the Moon, NASA's current plan involves multiple EVAs in rapid succession during a relatively short mission. The astronauts will wake up, get suited up, spend eight or nine hours on the surface, come back, try to sleep in tight quarters, and repeat. This isn't exploration. This is industrial-level work with a completion deadline.

Add in the radiation exposure outside Earth's magnetosphere, and the physiological stress becomes extreme. Astronauts on the ISS deal with elevated radiation, but it's an order of magnitude less than on the Moon. The cosmic rays and solar radiation on the lunar surface accumulate throughout the mission.

Combine sleep deprivation, radiation exposure, the physical stress of heavy suits, reduced gravity that throws off your balance, and the need to accomplish real work on a tight schedule. That's not exploration. That's what Rubins called it: "an extreme physical event."

The human body isn't designed for this. We can handle brief exposures. We can handle extended stays in comfortable environments. But this combination of factors is something we've never really tried on a large scale.

The Axiom Space Contract and the Weight Problem

NASA gave Axiom Space a $228 million contract to develop commercial spacesuits for Artemis III. This is a fixed-price contract, which means Axiom bears the risk if they go over budget or miss deadlines. It's a high-stakes, high-pressure project.

The contract was a shift in NASA's approach. Rather than developing suits entirely in-house (as they did for the ISS), they partnered with a commercial company and let them drive innovation. In theory, this is good. Commercial companies can be more agile, more willing to take risks, and more cost-conscious than government contractors.

In practice, it's created a situation where the suit's specifications had to be locked in early, compromises had to be made between competing demands, and the result is... well, it's better than what we had before, but not great. It's a suit that works, but is far from optimal.

Axiom's suit is based on NASA's own prototype exploration suit, which NASA developed over years of research. Axiom took that design and tried to improve it: make it lighter, more comfortable, more flexible, more reliable. They succeeded to some degree. The suit is lighter than NASA's 400+ pound prototype and more capable than Apollo suits.

But they're still fighting against fundamental physics. A suit that protects you on the Moon needs certain specifications. You need life support (water, oxygen, carbon dioxide removal). You need thermal control (the Moon gets cold at night). You need the pressure vessel itself to withstand the internal pressurization. You need redundancy in critical systems. You need thermal protection. All of this adds up to mass.

Add in the regulatory and safety requirements, and Axiom had to make the choice to prioritize safety and reliability over weight. That's probably the right call, but it means the resulting suit is still heavier than optimal.

The contract was critical because Artemis III's timeline depends heavily on the suit being ready. NASA currently hopes to launch Artemis III by the end of 2028, but that depends on the suits being ready, new human-rated landers being available from Space X and Blue Origin, and everything else falling into place. A suit delay would cascade into mission delays that could push the landing years into the future.

Modern lunar suits weigh significantly more than Apollo suits, at over 300 pounds compared to 185 pounds, despite advancements in materials.

Comparing to Apollo: Why Newer Isn't Always Better

This is the core of the paradox that Rubins articulated. On paper, modern suits are better. They're more capable, they provide greater life support, they have more redundancy, and they're made of better materials.

But in practice, for the specific job of walking on the Moon and doing scientific work, they might actually be worse.

Apollo suits were optimized for one thing: brief lunar surface exploration with minimal equipment. They were light, relatively simple, and designed to work in one-sixth gravity with no expectation of extended operations. The astronauts who wore them trained extensively and got very good at moving in them.

Modern suits are optimized for multiple things simultaneously: long-duration operations, high reliability, extensive redundancy, comfort, and flexibility. When you optimize for multiple competing goals, you end up with compromises on all of them.

Harrison "Jack" Schmitt, who actually walked on the Moon during Apollo 17, has been vocal about this in interviews. He's argued that the path forward should be toward lighter suits with greater mobility, not heavier suits with more features. "I'd have that go about four times the mobility, at least four times the mobility, and half the weight," he said in a NASA oral history interview.

The problem is that achieving that would require either revolutionary new materials or a complete rethinking of how we do life support and thermal control on the Moon. Neither of those is on the horizon for Artemis III.

Lunar Dust: The Abrasive Problem Nobody Planned For

Lunar dust isn't like Earth dust. It's jagged, abrasive, and incredibly fine. It gets everywhere. Apollo astronauts reported that it stuck to their suits, got tracked back into the lander, and generally caused problems. Some of them actually experienced irritation from the dust.

Modern suits have slightly better sealing, but they still have joints, ports, and openings where dust can get in. The fine dust particles are sharp at a microscopic level, and they can wear through protective coatings and seals over time.

This becomes a real problem on a longer mission. An Apollo mission lasted a few days. An Artemis mission will last weeks. That's weeks of repeated EVAs in an environment full of abrasive dust. The suit's seals will degrade. The joints will fill with particles. The life support systems will need to work harder to keep the suit functional.

Designing a suit to be resistant to lunar dust is possible, but it adds complexity and weight. Better seals, protective coatings, improved air filtration. All of these things add up.

The dust problem is actually part of why heavier suits have become acceptable. Better protection against dust requires better seals and more robust materials, both of which contribute to weight. It's another example of how solving one problem creates pressure on other aspects of the design.

Radiation Exposure Outside Earth's Magnetosphere

The International Space Station orbits within Earth's magnetosphere, which provides a significant shield against cosmic radiation and solar energetic particles. The Moon orbits much farther out, in an environment with much higher radiation exposure.

For short Apollo missions, this wasn't a huge concern from a mission-critical standpoint. The radiation doses were manageable, and astronauts were exposed for only a few days. For longer Artemis missions, radiation becomes a real health concern.

Spacesuits provide some shielding, but not a lot. The radiation just passes through. The internal shielding would require adding mass, and we're already struggling with suit weight. So Artemis astronauts will accumulate radiation doses that are significantly higher than ISS astronauts ever experience.

This is one of the "health risks" that Rubins mentioned to the National Academies panel. It's not an immediate problem (astronauts won't get sick during the mission), but it increases long-term cancer risk and other radiation-related health issues.

There's no solution to this with current technology. You can't make a suit light enough to do the work while also providing radiation shielding. Future missions might establish habitats with better shielding, but that's years away.

Artemis spacesuits are significantly heavier than Apollo suits, weighing 60% more on the Moon, which impacts astronaut mobility and fatigue.

Mobility and Flexibility: The Bending Problem

Rubins specifically mentioned one task that should be simple but is actually hard in a modern lunar suit: "Bending down to pick up rocks is hard."

This might sound trivial. But gathering samples is a core part of lunar exploration. Scientists want rocks. To get rocks, astronauts need to bend down, pick them up, and put them in bags. In a heavy, stiff suit, with a shifted center of gravity, in one-sixth gravity where your balance is unstable, this becomes a serious challenge.

Apollo suits actually had better mobility in the hips and lower body than the current Axiom design. Apollo engineers knew that astronauts would need to bend and pick things up, so they optimized the suit for that specific motion. The trade-off was that the suits were less capable in other ways, but they were really good at the job they were designed to do.

Modern suits prioritize different things. They have better upper body mobility for reaching and manipulating tools. They have more redundancy and longer life support for extended operations. But they sacrifice some of the hip and knee mobility that's necessary for bending tasks.

It's another example of optimization trade-offs. You can't have everything. The question is what you prioritize, and it seems like modern suit designs have made choices that weren't optimal for lunar surface work.

Fixing this isn't trivial. Improving hip mobility while maintaining suit integrity and not adding too much weight requires engineering work. It's possible, but it requires iteration and testing. There may not be time for that before Artemis III launches.

The Extravehicular Mobility Unit (EMU) Legacy

NASA's current spacesuits for ISS work are called Extravehicular Mobility Units, or EMUs. They were developed in the 1980s and have been used ever since, with incremental upgrades. They're in their fourth decade of service.

The EMU design prioritized reliability and longevity. It was built to be maintained, repaired, and reused for hundreds of spacewalks. It succeeded spectacularly at that goal. EMUs have logged more spacewalk hours than any other suit design in history.

But they weren't designed for lunar work. They were designed for zero-gravity operations near the ISS, where astronauts don't have to support their own weight and work is done in a relatively benign environment. Taking an ISS-optimized suit and repurposing it for the Moon was never going to be ideal.

The Axiom suit is based on NASA's prototype replacement for the EMU, which itself was designed based on lessons learned from decades of EMU operations. So in some sense, the Axiom suit incorporates seven decades of spacesuit development history.

But that history is biased toward ISS-like operations. The fundamental design philosophy still reflects the compromises that made sense for ISS work. Moving that philosophy to lunar work, with different gravity, different tasks, and different constraints, creates new compromises.

Sleep Quality and Physiological Stress

Beyond just the lack of sleep, there's the quality of sleep that astronauts will get on the Moon. They'll be in tight quarters, in full spacesuits or in minimal shirtsleeve environments, with the constant knowledge that they're on an alien world in an extremely hostile environment.

Physiological stress doesn't just come from physical exertion. It comes from the environment, the high stakes, the need to accomplish specific objectives on a timeline. All of that increases cortisol and adrenaline, making it harder to sleep even when you have time to sleep.

Add in the radiation exposure, the accumulated muscle fatigue from heavy suits and one-sixth gravity work, and the fact that astronauts' circadian rhythms will be disrupted by the lunar day/night cycle (which is about 14 Earth days on and 14 off), and you have a recipe for very poor sleep quality.

Poor sleep impairs cognitive function, decision-making, and fine motor control. All of these are critical for scientific work and for maintaining safety in a hostile environment. Fatigue impairs judgment, and impaired judgment on the Moon can be fatal.

This is a problem that suits can't solve. It's an environmental and mission-planning problem. But it's worth noting that the solution (shorter missions, better habitat design, more time for rest) conflicts with the goal of maximizing the amount of scientific work done during each landing.

Apollo suits excelled in weight and mobility, crucial for lunar missions, while modern suits offer superior life support and redundancy. Estimated data based on qualitative analysis.

Training and Suit Familiarization

There's a factor that often gets overlooked in suit discussions: training. Astronauts get much better at working in spacesuits with practice. They learn to move efficiently, they develop muscle memory, and they get used to the constraints.

Apollo astronauts trained extensively in mockups and analog environments. By the time they got to the Moon, they were very skilled at working in the suits. The later Apollo missions were more productive than the earlier ones partly because the astronauts had more experience.

Artemis astronauts will also train extensively. They'll use analog sites on Earth (locations that simulate the Moon) to practice their tasks. They'll spend hundreds of hours in simulator suits.

But there's a limit to what training can overcome. Training can make you better at a bad tool, but it doesn't make the tool good. A 300-pound suit with poor mobility will still be a 300-pound suit with poor mobility, no matter how much you train.

There's also the question of whether there's enough time for adequate training before Artemis III. Current mission timelines are already aggressive. Adding extensive suit-specific training on top of all the other training adds pressure to the schedule.

The Radiation and Dust Environment

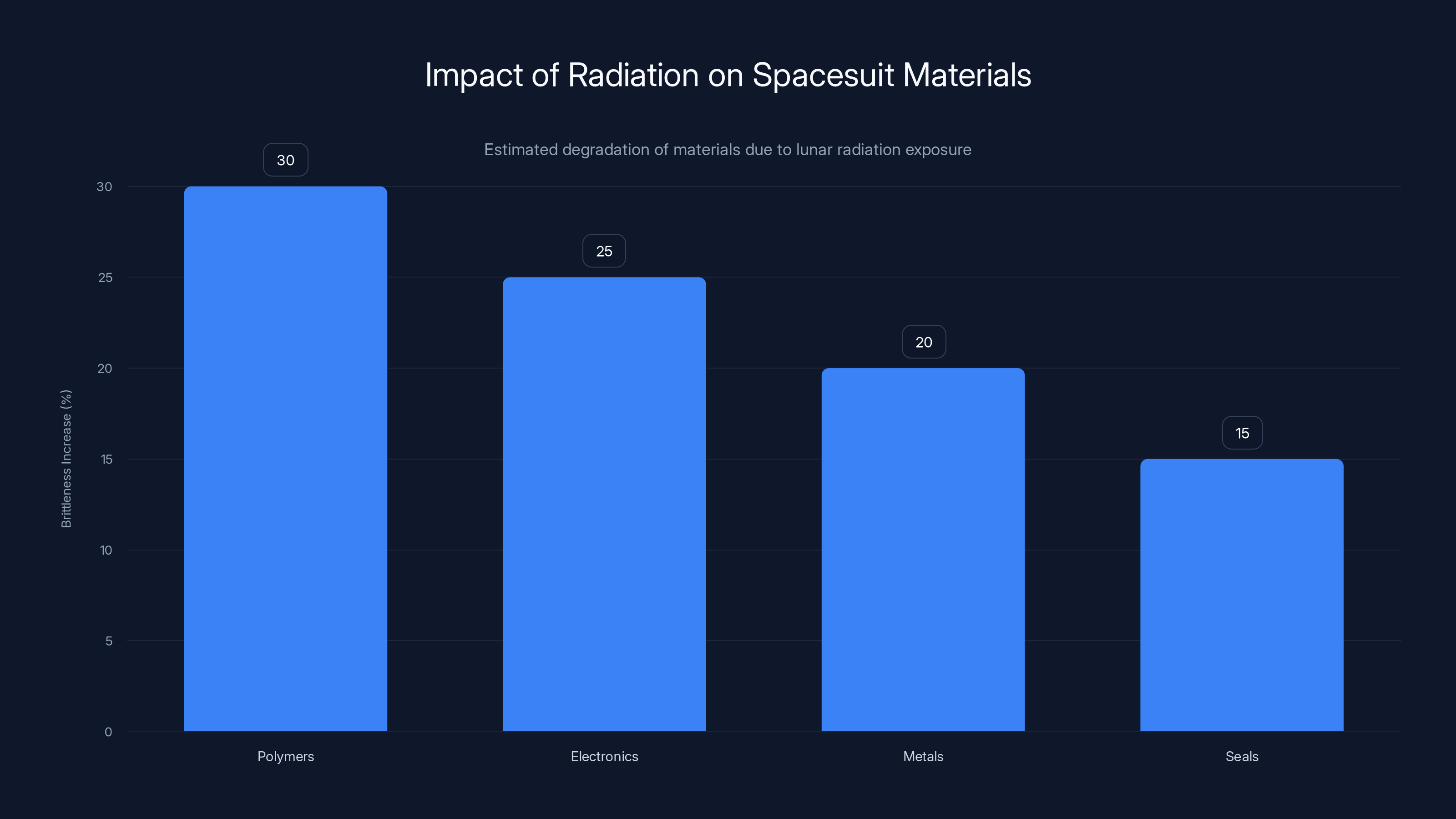

Combining the radiation problem with the dust problem creates a compounding challenge. Radiation doesn't just expose astronauts. It also damages materials. Polymers break down under radiation exposure. Electronic components fail. Metals become brittle.

A spacesuit that's designed to work in the mild ISS environment might degrade rapidly on the lunar surface. The materials might become more brittle, the seals might degrade faster, and the electronics might fail sooner.

NASA engineers know this, and Axiom engineers know this. The suits are being designed with radiation tolerance in mind. But you can't engineer around all of it. There will be degradation, and that degradation might reduce suit lifespan or require more frequent maintenance.

For a short mission, this isn't a huge deal. For the longer Artemis missions that NASA is planning, it becomes a real constraint. A suit that degrades might not be usable for the entire mission duration.

Design Philosophy: Protection Versus Capability

Ultimately, the suit weight and capability problem comes down to a fundamental engineering trade-off: protection versus capability.

A lighter suit would be more capable. Astronauts could move faster, bend easier, and accomplish more work. But it would be less protective, provide less redundancy, and have shorter life support duration.

A heavier suit with more redundancy would be safer and more reliable. It would support longer operations and have backup systems for critical functions. But it would be harder to work in and would limit what astronauts could accomplish.

NASA's engineers have chosen to prioritize protection and reliability. That's a defensible choice. An astronaut lost to a suit failure would be catastrophic. A mission that's less productive but all astronauts return alive is still a success.

But Rubins and Schmitt are arguing for a different balance. They've been to space. They know what suits can do and what they can't. And they're suggesting that the current balance is wrong for lunar work.

The counter-argument is that we don't fully understand the lunar environment yet. We don't know all the ways that suits will fail or all the challenges astronauts will face. In that context, having extra redundancy and protection makes sense. You're willing to accept a heavier, more restrictive suit because the environment is genuinely hostile and inadequately understood.

Both perspectives have merit. The question is whether the balance is right. And based on what experienced astronauts are saying, it doesn't seem like it is.

Estimated data shows that polymers in spacesuits can become up to 30% more brittle due to radiation, with electronics, metals, and seals also experiencing significant degradation.

Timeline Pressures and Design Compromises

Artemis III is supposed to happen by the end of 2028. That's ambitious. It's a government mission, so timelines slip, but NASA is committed to this date. And that commitment affects everything.

When you have a hard deadline, you have to lock in designs before they're optimal. You have to make compromises to stick to the schedule. You can't do unlimited iteration and testing.

The Axiom contract is fixed-price, which means Axiom is motivated to finish on time and within budget. That's good for controlling costs. But it also means they can't spend years perfecting the design. They have to deliver something that works, on time, within the budget.

Mission success doesn't just depend on hardware being ready. It also depends on the Space X Starship being ready, the Blue Origin Blue Moon lander being ready, and a dozen other things. If the suits aren't ready, the whole timeline slips.

This schedule pressure is real, and it's driving decisions. Engineers would probably prefer more time to optimize the suit design. But they don't have it.

Future Iterations and the Path Forward

Artemis III won't use the final suit design. It will use generation 1 of Axiom's commercial suit. There will be generation 2, generation 3, and potentially many more generations.

Each generation can incorporate lessons learned from previous operations. Astronauts who use the first suits will provide feedback. NASA and Axiom will analyze what worked and what didn't. They'll make improvements.

So while Rubins' criticism of current suits is valid, it's also important to note that this is an iterative process. The suits will get better. Future Artemis missions will use improved versions.

The question is whether the first generation is good enough. Is it good enough to accomplish the mission objectives? Is it safe enough? Will it enable the scientific work that NASA wants to accomplish?

Based on what experienced astronauts are saying, the answer is probably yes, but barely. The suits will work. Astronauts won't love them, but they'll accomplish their objectives.

That's not a ringing endorsement, but it's probably sufficient for a first generation of a new system. Technology is rarely perfect on the first try.

Lessons from Apollo and the Transition to Modern Space

Apollo missions were short, focused, and accomplished specific objectives. Land on the Moon, collect samples, return home. The suits were optimized for that mission profile.

Artemis missions are attempting something more ambitious. Longer stays, more extensive exploration, more scientific objectives. The suits need to enable that, and the current design represents a compromise between what's technically possible and what's achievable on a schedule and budget.

The lesson from Apollo isn't that we should go back to 1970s suit technology. It's that optimization for specific mission requirements matters. Apollo suits were optimized for Apollo missions. Artemis suits are being optimized for Artemis missions. But there's disagreement about whether the optimizations are correct.

Historically, space programs have often over-engineered solutions out of an abundance of caution. You put in redundancy because space is dangerous and failures can be catastrophic. You make things robust because you can't easily repair or replace them. This approach has worked pretty well.

But it comes with a cost: weight, complexity, and reduced capability. For lunar surface operations, where astronauts need to do useful work, that cost might be too high.

The Health Risk Perspective

When Rubins spoke to the National Academies panel, she wasn't just complaining about suit weight and mobility. She was raising health concerns.

The physical trauma from wearing heavy, restrictive suits for extended periods is real. Skin abrasions, joint pain, potential fractures. These aren't minor problems. They could compromise an astronaut's ability to perform critical tasks or could lead to serious injuries.

Add in the radiation exposure, the sleep deprivation, the accumulated fatigue, and the physiological stress of the environment, and you're looking at a situation where astronaut health is genuinely at risk.

This is why the National Academies panel exists. NASA brings in outside experts to assess mission plans and raise concerns. The panel identified suit performance and astronaut health as critical issues.

NASA is aware of these concerns. But knowing about a problem and solving it are different things. The suit development is locked in. The mission timeline is locked in. NASA will proceed with the best solutions available, which means accepting some level of risk.

That's the nature of human spaceflight. You accept risk because the alternative is not going to space. But the level of risk should be explicitly understood and accepted by decision-makers.

Broader Implications for Lunar Exploration

The suit problem isn't just about Artemis III. It's about the entire future of sustained lunar exploration.

If astronauts can't work effectively on the lunar surface because of suit limitations, that constrains what we can accomplish. We can't do long-duration scientific missions. We can't establish habitats. We can't mine resources or build infrastructure.

Solving the suit problem is critical for the next phase of human space exploration. We need suits that are light, flexible, durable, and protective. We need them to work in a radiation-rich environment with abrasive dust and partial gravity.

The Axiom suits are a step forward. They're better than ISS suits for lunar work. But they're not optimal. And they probably won't be optimal for Artemis II or III either.

The real solution might require revolutionary advances in materials, life support technology, or suit design that we don't currently have. Metamaterials that are lighter and stronger. Exoskeletons that augment astronaut strength. Completely new approaches to pressure vessel design.

None of these are on the horizon for the next few years. So NASA will work with the tools available, and astronauts will work in suits that are less than ideal.

The Commercial Space Dimension

One unique aspect of Axiom's contract is that they're a private company. They have a financial incentive to deliver a suit that works and that can potentially be sold to other customers.

NASA is essentially outsourcing suit development to the private sector, which is consistent with the broader trend of commercial space. Space X builds rockets, Blue Origin builds landers, and now Axiom builds suits.

This has advantages (competition, innovation, cost control) and disadvantages (reduced oversight, potential conflicts of interest, less institutional knowledge retained at NASA).

For spacesuits, the commercial approach is relatively new. For decades, suits were developed by government contractors working for NASA. Now, Axiom is driving the design, though with NASA specifications and oversight.

The long-term implication is that suit development could move entirely to the commercial sector. Multiple companies could develop different suit designs optimized for different missions or different customers. This could drive innovation.

But there's a risk: if suit development becomes too commercialized, it might prioritize cost and efficiency over safety and capability. Balancing these incentives will be important.

Unknowns and Contingency Planning

Despite decades of space exploration, there are still unknowns about how humans will perform on the lunar surface during long-duration missions.

The Apollo missions were too short to reveal many problems. Astronauts spent a few days on the Moon. They didn't sleep for extended periods in lunar gravity. They didn't accumulate radiation doses from weeks of surface operations.

Artemis missions will reveal new challenges. Some of them will be suit-related. Others will be environmental or physiological. Some might be unknown unknowns that no one anticipated.

NASA is building contingency into the mission planning. If something goes wrong, there are procedures and fallbacks. But you can't contingency-plan for everything.

The suits are critical because they're the interface between the astronauts and the environment. If they fail or underperform, options become very limited very quickly.

This is another reason why experienced astronauts like Rubins are raising concerns. They want decision-makers to explicitly understand the limitations and risks. They want contingency planning to account for the possibility that the suits might not perform as well as hoped.

Expert Perspectives and Recommendations

The astronauts who've actually done this work are saying clearly that suit performance is a concern. Rubins, Barratt, and others have raised specific issues. Schmitt, who walked on the Moon, has argued for different design priorities.

These aren't complaints about minor discomforts. They're concerns about whether the suits are adequate for the mission.

NASA is listening. The National Academies panel is listening. Engineers are listening. But listening to concerns is different from solving the problems raised.

The suit design is locked in. The contract is fixed-price. The timeline is aggressive. So the fixes, if any, will be incremental improvements to the existing design, not fundamental redesigns.

Future generations of suits can incorporate lessons learned. But Artemis III will fly with generation 1, and generation 1 has limitations.

The Bottom Line

Modern lunar spacesuits are heavier, less flexible, and more physically demanding than optimal for lunar surface work. They're heavier than Apollo suits, even though they're "better" in terms of capability and redundancy. They cause physical trauma, create balance issues, and will exhaust astronauts who are already dealing with sleep deprivation and radiation exposure.

They'll work. Astronauts will accomplish the mission. But the experience will be grueling, and the limitations are real.

As Rubins said, "I think the suits are better than Apollo, but I don't think they are great right now. They still have a lot of flexibility issues."

That's probably the most honest assessment. Not perfect, not ideal, but good enough to accomplish the mission. That's what we get when we push hard to meet a timeline and optimize for multiple competing objectives.

The suits will get better with future iterations. Lessons learned will inform better designs. But for now, Artemis astronauts will work in suits that aren't great, because that's what's available when humanity decides to go back to the Moon.

FAQ

What exactly is the problem with modern lunar spacesuits?

Modern lunar spacesuits are significantly heavier than Apollo-era suits (300+ pounds vs. 185 pounds), more restrictive in critical joint movements, and cause measurable physical trauma to astronauts including skin abrasions, joint pain, and potential orthopedic injuries. The heavier weight and compromised center of gravity in lunar gravity creates balance issues and limits mobility for essential tasks like sample collection.

Why are new spacesuits heavier if technology has advanced?

Modern suits prioritize safety, redundancy, and extended mission duration over weight optimization. They need to support 8-9 hour EVAs with multiple redundant life support systems, better thermal protection, and enhanced durability in the harsh lunar environment. This additional capability and protection directly increases weight, particularly in the life support backpack systems.

How does one-sixth gravity affect spacesuit performance?

One-sixth lunar gravity changes the physical demands significantly. While it reduces the weight of equipment, it still requires astronauts to support themselves and maintain balance, creating an awkward situation where suits are designed for either microgravity (ISS) or Earth gravity, but not specifically for partial gravity. The shifted center of gravity from the life support backpack becomes particularly problematic, making falls more likely despite the reduced gravity.

What health risks do astronauts face wearing these spacesuits for extended periods?

Astronaut physicians report that prolonged spacesuit wear causes skin abrasions from seams and pressure points, joint pain from restricted mobility, potential stress fractures from accumulated physical strain, and in some cases actual orthopedic injuries. Combined with radiation exposure outside Earth's magnetosphere and severe sleep deprivation, the overall physiological stress reaches what astronauts describe as an "extreme physical event."

How do the new Axiom suits compare to Apollo-era spacesuits?

Artemis suits are more technologically advanced with better life support, greater redundancy, and improved materials, but they're also significantly heavier and more restrictive in critical movements like bending at the hips and knees. While they're "better" on paper in terms of capability and safety margins, experienced astronauts note they're actually more physically demanding for the actual work of exploring the lunar surface.

What is the timeline for the Axiom spacesuits?

Axiom Space has a fixed-price $228 million contract to develop commercial spacesuits for Artemis III, currently targeted for launch by the end of 2028. These will be first-generation commercial lunar suits, with future missions expected to use improved versions incorporating lessons learned from these initial Artemis operations.

Can the suit problems be fixed before Artemis III launches?

The suit design is locked in and the mission timeline is aggressive, so major redesigns aren't feasible. Minor improvements and adjustments are possible, but Artemis III will likely launch with generation-one Axiom suits that have known limitations. Future generations will incorporate improvements based on astronaut feedback and operational experience.

Why does lunar dust matter for spacesuits?

Lunar dust is extremely fine and jagged at the microscopic level, making it highly abrasive. It damages protective coatings, wears down seals, and gets into joints and mechanisms over time. On longer missions, accumulated dust exposure degrades suit materials, potentially reducing seal integrity and forcing increased maintenance requirements during the mission.

How much radiation exposure will Artemis astronauts receive compared to ISS astronauts?

Lunar surface radiation exposure is roughly 100-200 times higher than at sea level on Earth and significantly higher than on the ISS, because the Moon is outside Earth's protective magnetosphere. This accumulated exposure increases long-term cancer risk and other radiation-related health effects, with no practical way to shield astronauts without making suits prohibitively heavy.

What do experienced astronauts say about the current suit designs?

Former astronaut Kate Rubins, who conducted multiple spacewalks on the ISS, stated clearly that while new suits are better than Apollo suits on paper, "I don't think they are great right now." She emphasized concerns about flexibility, balance issues, and the physical trauma of wearing heavy restrictive suits for extended periods. Physicist and Apollo 17 astronaut Harrison Schmitt has advocated for suits with "four times the mobility and half the weight," suggesting current designs prioritize protection over capability.

Return to main navigation and explore more about space exploration, human spaceflight challenges, and the future of lunar missions. The next generation of lunar exploration depends on solving the spacesuit paradox: creating equipment that protects astronauts while enabling them to accomplish critical scientific work in one of the most hostile environments humans will ever encounter.

Key Takeaways

- Modern Axiom lunar suits weigh over 300 pounds in Earth gravity, significantly heavier than Apollo's 185-pound suits, contradicting expectations of technological progress.

- Astronaut physicians report serious physical trauma including skin abrasions, joint pain, and potential orthopedic fractures from extended spacesuit wear during lunar operations.

- The combination of heavy suits, one-sixth gravity, radiation exposure, sleep deprivation, and abrasive lunar dust creates an 'extreme physical event' that experienced astronauts describe as more challenging than any ISS spacewalk.

- Current suit designs represent compromises between protection/redundancy and mobility/capability, with engineers prioritizing safety over the lighter, more flexible design that Apollo veteran Harrison Schmitt advocates for.

- Fixed-price contract timelines and mission scheduling pressure mean Artemis III will launch with first-generation suits that have known limitations, with improvements likely only coming in future generations.

Related Articles

- NASA's Crew-11 Early Return: What the Medical Concern Means [2025]

- Navigating Unknown Terrain: NASA's Decision to Return Astronauts Home Amid Medical Concerns [2025]

- Blue Origin's New Glenn Third Launch: What's Really Happening [2026]

- SpaceX IPO 2025: Why Elon Musk Wants Data Centers in Space [2025]

- Tesla's Dojo3 Space-Based AI Compute: What It Means [2026]

- Dr. Gladys West: The Hidden Mathematician Behind GPS [2025]

![Lunar Spacesuits: The Massive Challenges Behind Artemis Missions [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/lunar-spacesuits-the-massive-challenges-behind-artemis-missi/image-1-1769430969295.jpg)