NASA's Mars Orbiter Decision: What's at Stake [2025]

NASA is sitting on one of those decisions that sounds boring until you realize it'll shape space exploration for the next ten years.

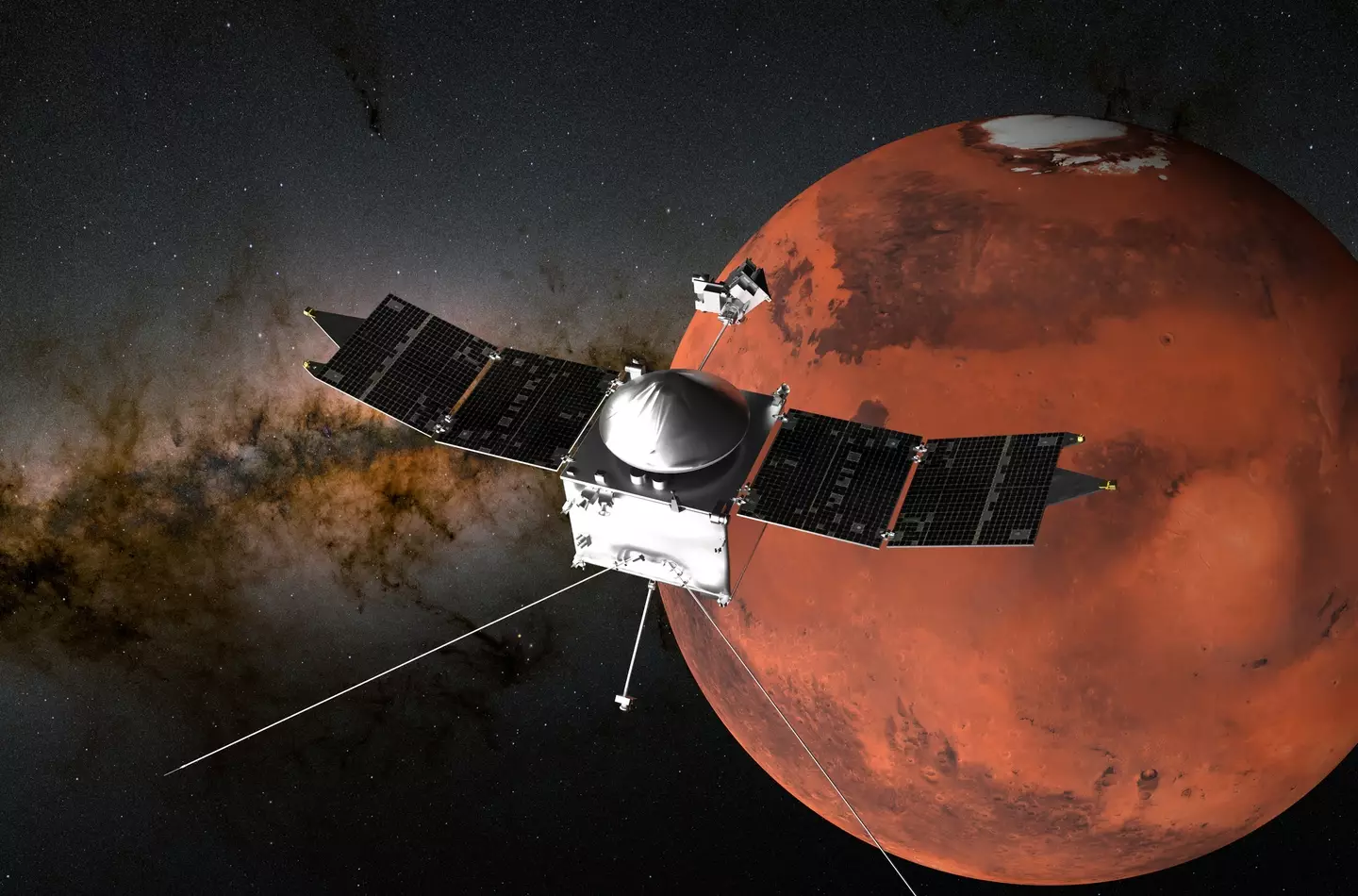

The issue? The agency needs to pick a spacecraft to relay communications from Mars back to Earth. Sounds straightforward. But buried inside that simple requirement is a massive debate about money, priorities, competition, and what NASA's role should be in the commercial space era.

Here's what's happening behind closed doors at NASA Headquarters, why it matters, and why the clock is ticking.

TL; DR

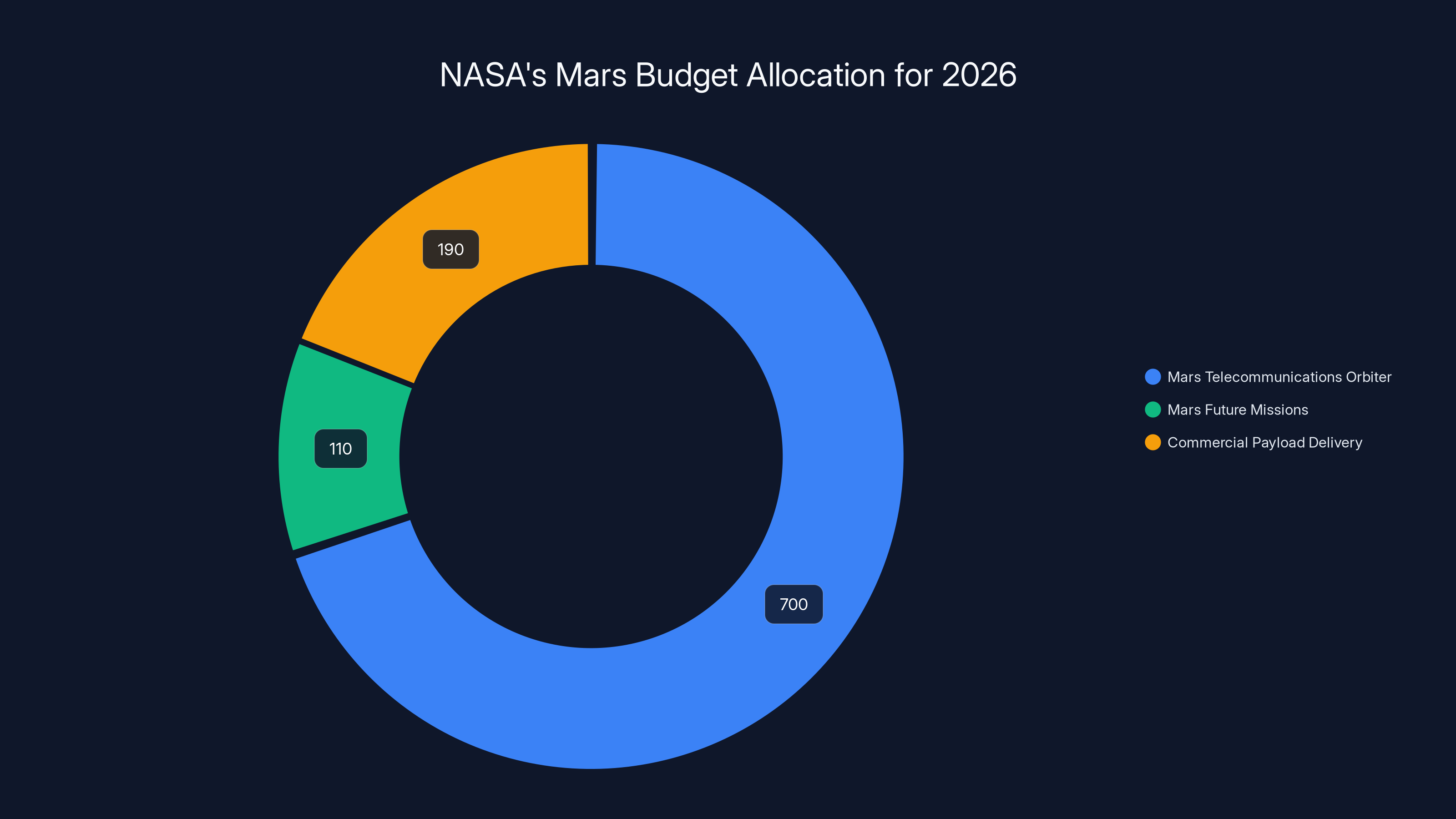

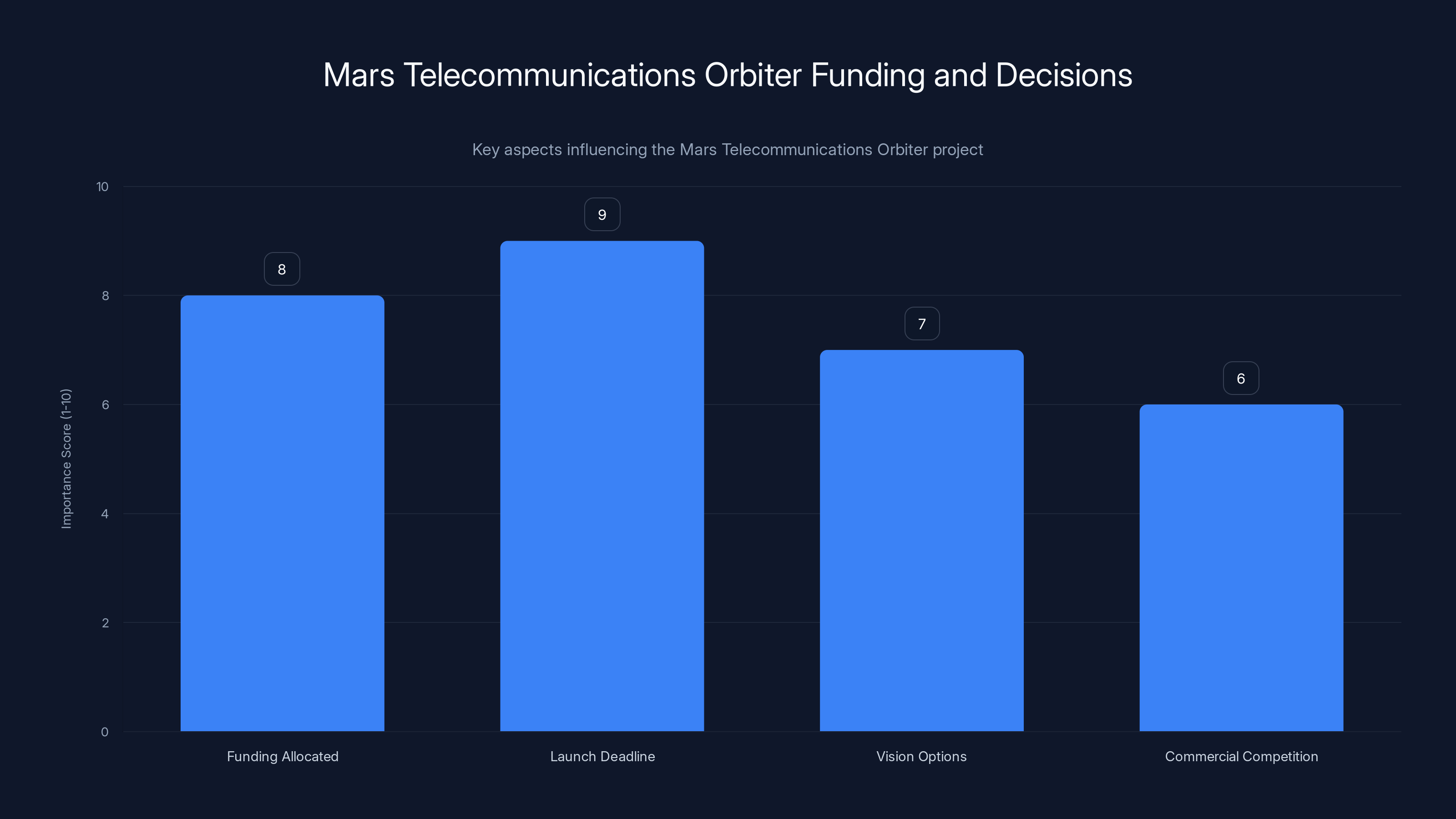

- Congress allocated $700 million for a Mars Telecommunications Orbiter, but NASA must obligate the funds by September 30, 2026

- Two competing visions exist: a stripped-down communications relay versus a science-packed observatory

- The commercial question: Should NASA favor companies with existing Mars Sample Return contracts, or open the competition wider?

- Timeline pressure: The spacecraft needs to launch in late 2028 to hit the next favorable Mars transfer window

- Bottom line: This decision will determine whether the next decade of Mars exploration is led by NASA science priorities or commercial industry partnerships

NASA's Mars Telecommunications Orbiter has a budget of

Why Mars Communications Matter More Than You Think

Let's start with the obvious part: Mars is really, really far away. When you send a rover or a lander to the red planet, you can't just call mission control and say "hey, we've got a problem." Radio signals take between 3 and 22 minutes to travel between Earth and Mars, depending on orbital positions.

So every piece of data, every image, every science reading has to hop through relay satellites in Mars orbit before it reaches Earth. These orbiters are basically the post offices of space. Without them, your rovers are just sending data into the void.

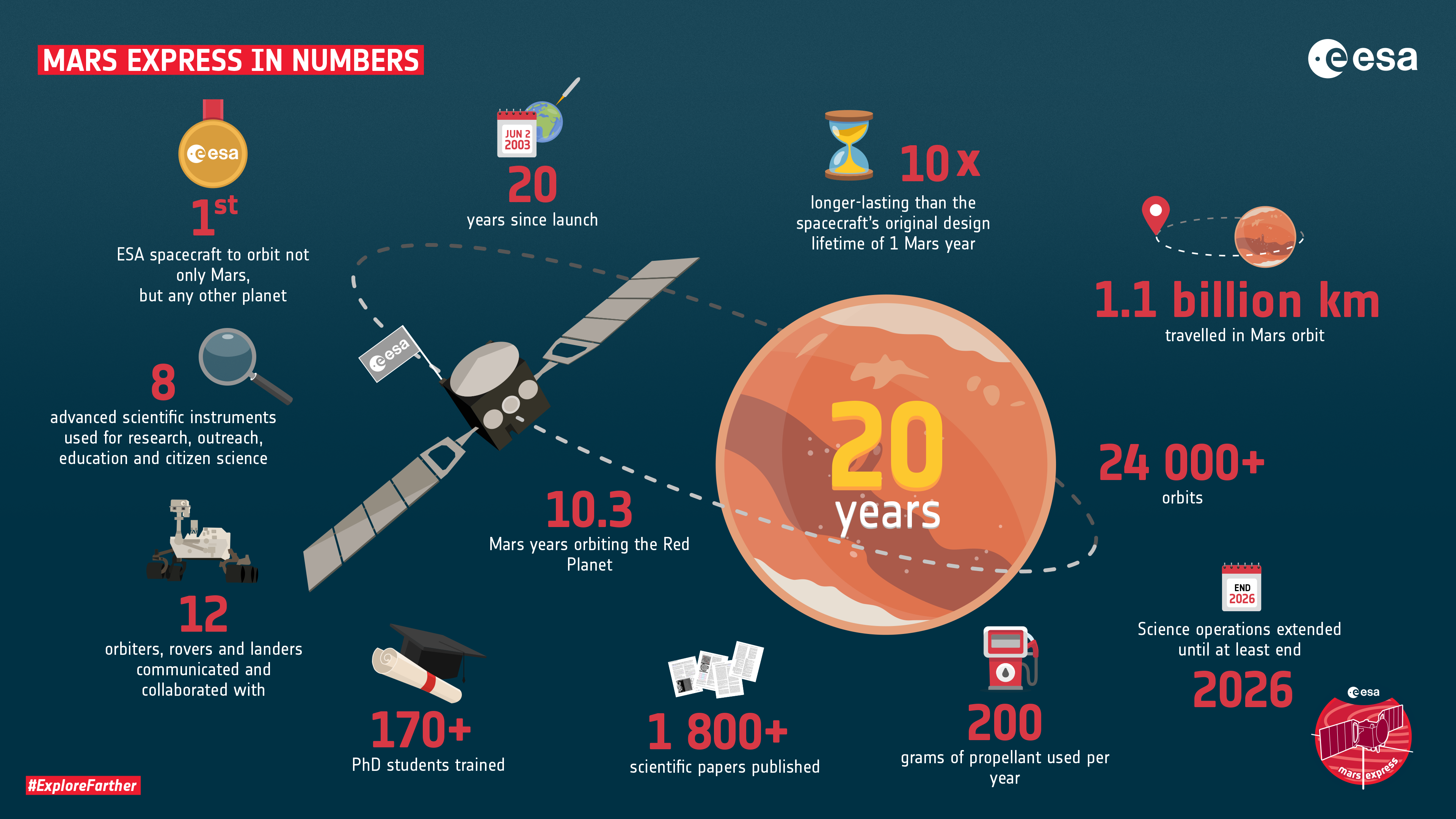

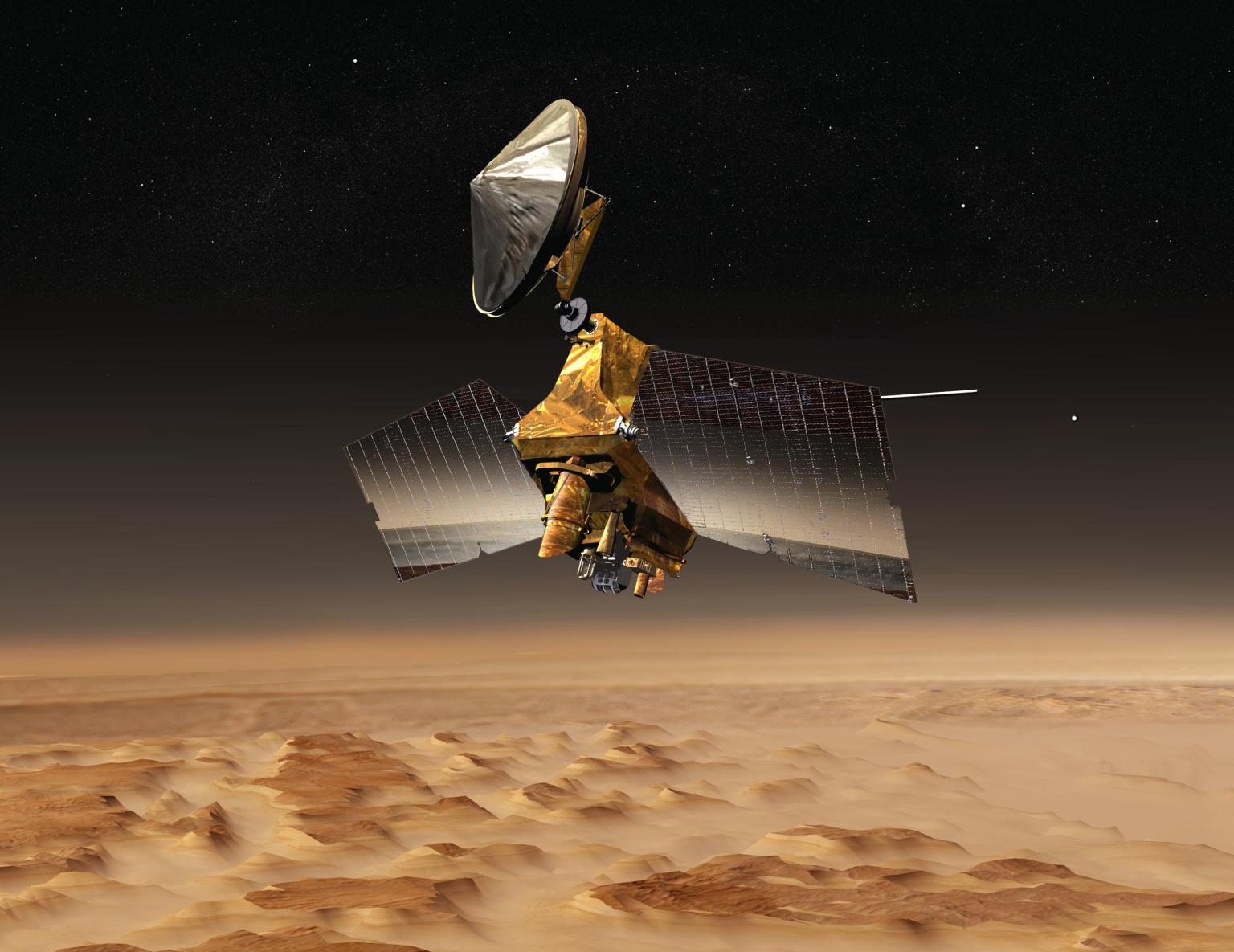

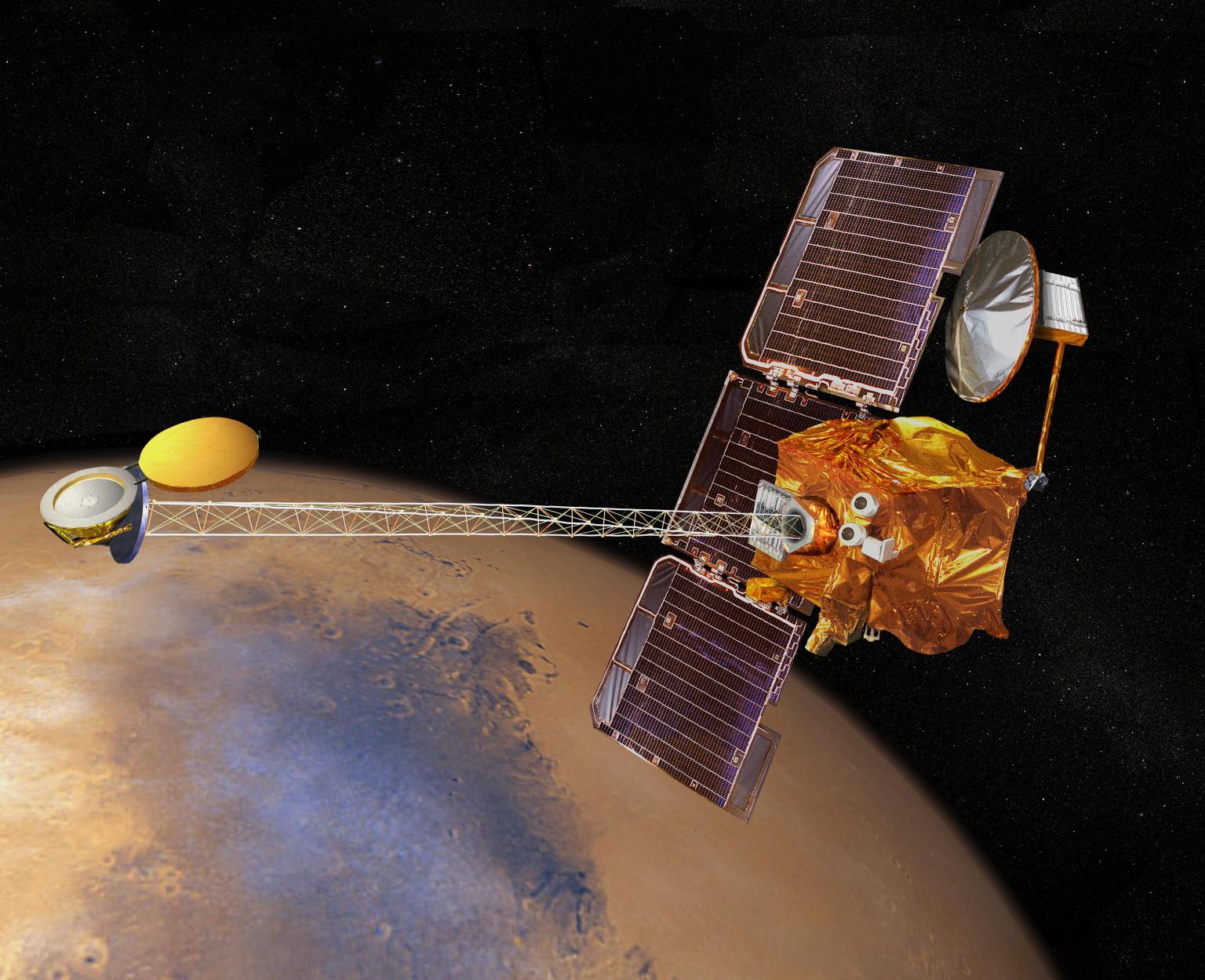

NASA currently depends on two aging workhorses: the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) and MAVEN. The MRO has been there since 2006—that's 20 years of continuous operation. Twenty years. That's like expecting your laptop from 2004 to still be your primary computer in 2025. MAVEN failed recently, which shocked nobody in the Mars community, because these things weren't designed to last two decades.

Without a new relay, NASA's Mars program hits a wall. All those rovers, landers, and future human missions depend on this infrastructure.

But here's where it gets interesting. Congress didn't just say "go build a communications orbiter." They included some pretty specific language that's got people inside and outside NASA confused about what they actually want.

The $700 Million Question: What Actually Gets Built?

In 2024, Congress passed what staffers called the "One Big Beautiful Bill"—supplemental appropriations legislation that included $700 million specifically for a Mars Telecommunications Orbiter. That's a lot of money. And it came with conditions.

The language, authored by a key staff member working for Senator Ted Cruz of Texas, included some unusual requirements. The spacecraft had to come from US companies that had received funding in fiscal year 2024 or 2025 for "commercial design studies for Mars Sample Return." More on that in a second. But the real question is: what does $700 million actually buy you?

According to industry sources who spoke to various outlets, the answer is confusing. One experienced aerospace official said "

So why is Congress throwing $700 million at it?

The answer involves three competing visions of what this mission should be:

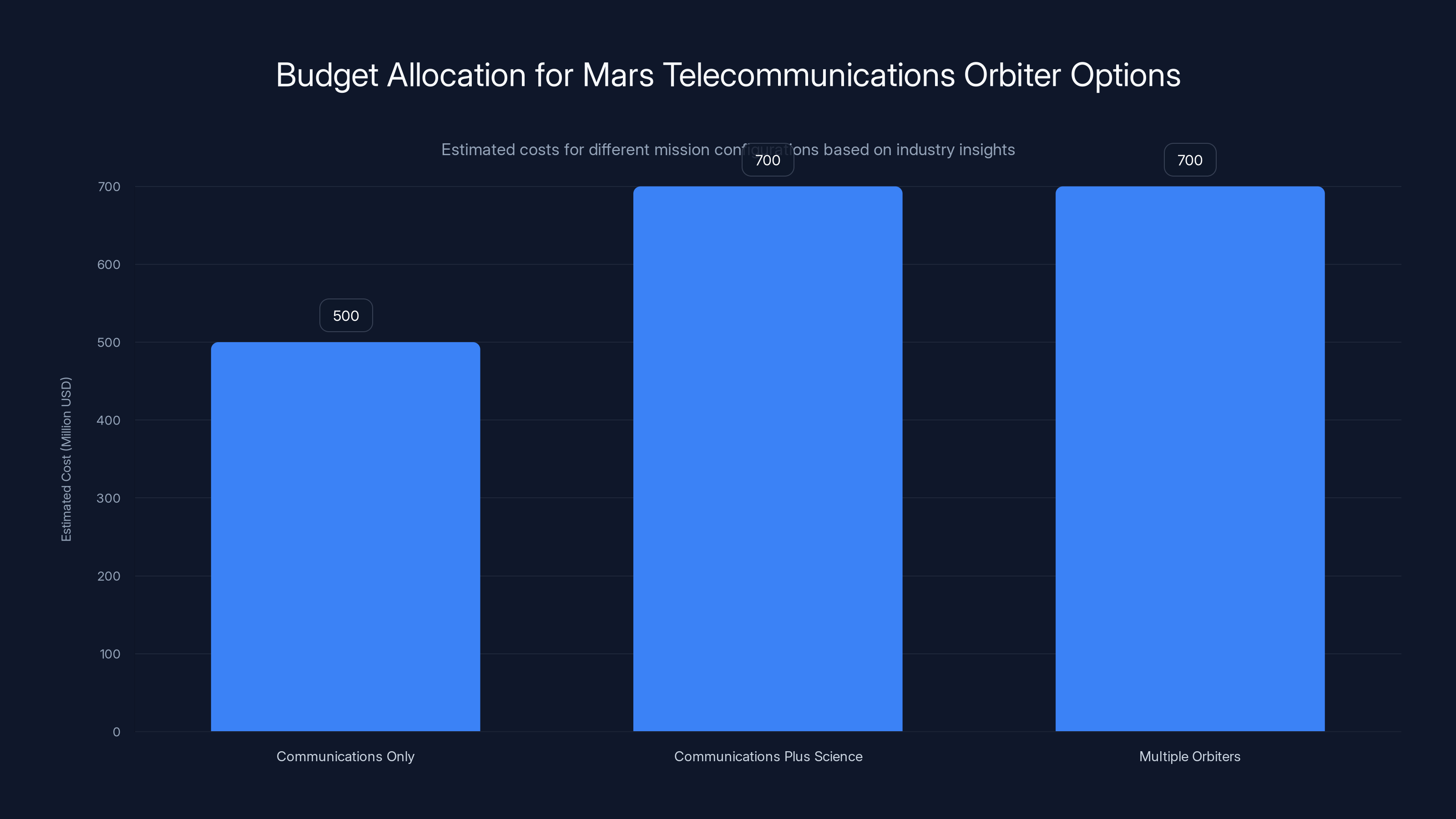

Option 1: Communications Only. Strip it down. Orbiter with a good antenna, reliable power systems, and that's it. Get it out the door fast, keep costs down, focused purely on the relay mission. This is what NASA's official statement suggests they're planning to do.

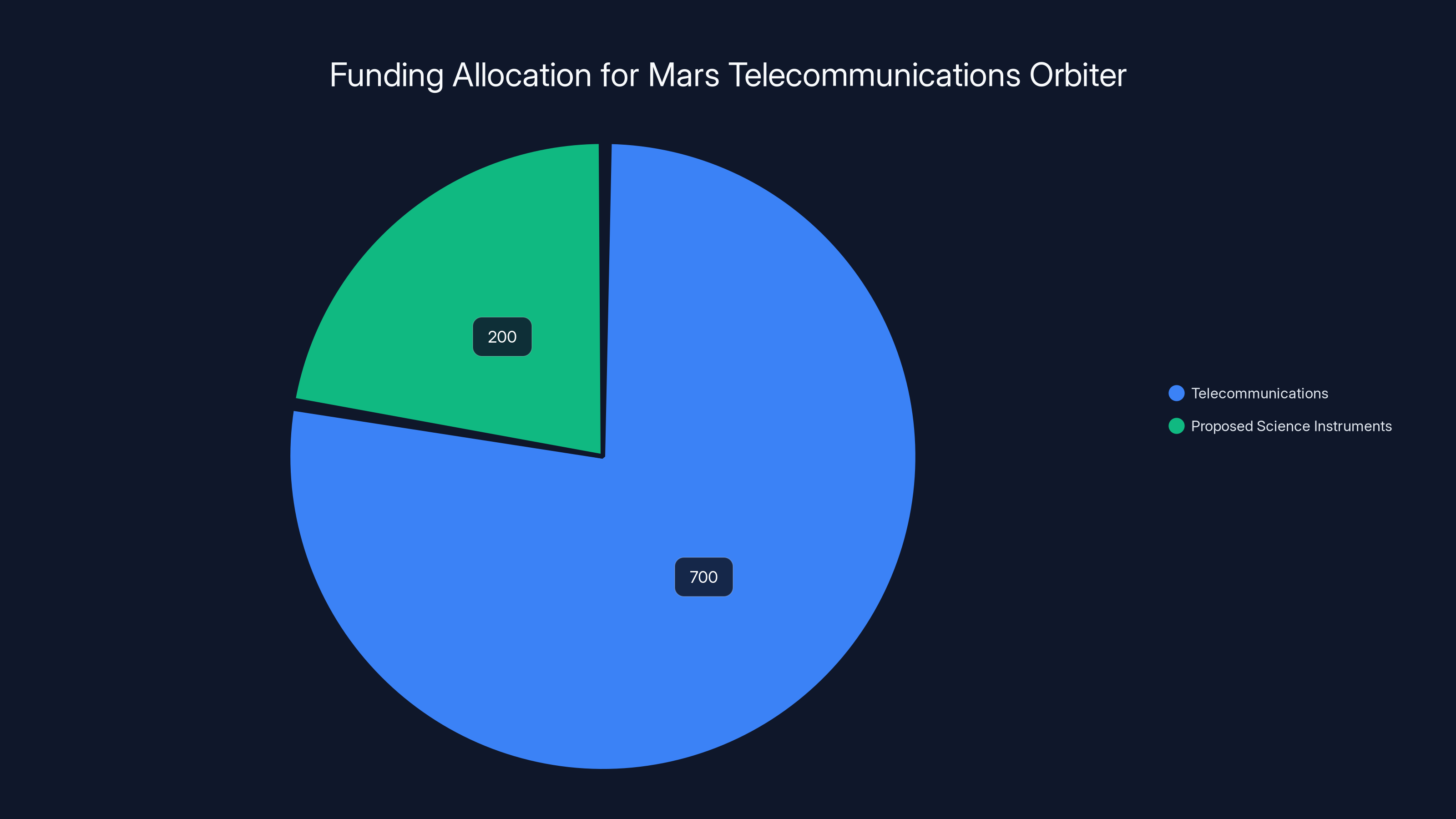

Option 2: Communications Plus Science. Take that orbiter, add three or four scientific instruments. A high-resolution camera (desperately needed since the best camera at Mars is 20 years old). Maybe a magnetometer to study Mars's remnant magnetic field. A spectrometer to hunt for subsurface water ice. Space weather instruments. According to NASA scientists, you could add a solid science package for about $200 million. That leaves room to breathe in the budget and actually accomplish something.

Option 3: Multiple Orbiters and Capabilities. Open the competition wider. Ask multiple companies to propose different solutions. Maybe one company focuses on communications. Another adds a small lander. Someone else brings specialized instruments. Tap into other Mars funding pools beyond the $700 million to create real competition.

Casey Dreier, chief of space policy at the Planetary Society, thinks Option 2 is obvious: "To me, it seems like an easy decision. This project is already going to Mars, and science would add real value." Adding instruments to a mission that's already headed there is textbook good stewardship. The marginal cost is small compared to the scientific return.

But NASA's leadership isn't convinced it's that simple.

The 'Communications Only' option is estimated to cost

The Commercial Partnership Complication

Here's where the decision gets politically charged.

In 2024, NASA selected companies to conduct commercial design studies for Mars Sample Return missions. These are faster, cheaper approaches to bring Martian samples back to Earth without NASA building all the hardware. Companies selected included Rocket Lab and others.

The Congressional language specifically says the new orbiter must come from companies that received this 2024 or 2025 funding. That's not an accident. Several observers noted the language appeared "designed to favor Rocket Lab."

Rocket Lab, founded by New Zealand-born entrepreneur Peter Beck, has been vocal about their Mars ambitions. They've proposed a telecommunications orbiter concept. If you're a betting person and you see Congressional language that seems tailored to a specific contractor's proposal, you'd reasonably conclude someone on Capitol Hill thinks Rocket Lab should win this contract.

But not everyone at NASA is happy about this constraint.

The commercial space industry has fragmented into different camps. SpaceX has its own Mars plans. Blue Origin (owned by Jeff Bezos) has proposed its own architectures. Established contractors like Lockheed Martin and Boeing have deep Mars experience. When Congress narrows the eligible vendors, you're not running an open competition. You're picking winners.

That creates problems. First, it might not result in the best technical solution. Second, it upsets other companies who feel locked out. Third, it creates perception issues around fairness.

NASA's new administrator, Jared Isaacman, took office just over a month ago. He inherited this mess along with about fifty other critical decisions, including the Artemis II launch (now scheduled for February 8, 2026). Isaacman hasn't publicly stated whether he supports adding science instruments or respects the Congressional language as written.

What we know is this: time is running out to figure it out.

The Timeline Problem Is Real and Severe

Legislation requires NASA to obligate the funding "not later than fiscal year 2026." Fiscal year 2026 ends on September 30, 2026. That's less than nine months away from this writing.

Obligate is a technical term meaning the money has to be committed contractually. So NASA has roughly nine months to:

- Decide what the mission actually should do (comms only, comms plus science, multiple orbiters, etc.)

- Draft the procurement request

- Release it to industry

- Allow companies time to respond (usually 30-60 days minimum)

- Evaluate proposals

- Select a winner

- Award the contract

That's ambitious. Possible? Sure. But tight.

Why the rush? Because the spacecraft needs to launch in late 2028 to catch the next favorable Mars transfer window. Miss that window, and you're waiting until 2030. Miss that, and suddenly you're in 2032. Every two years you miss is a mission cycle lost.

NASA's current Mars schedule shows no other major spacecraft launching to Mars in 2026 or 2027. This Telecommunications Orbiter might be the only Mars mission during President Trump's second term. It's politically significant. The Trump administration wants to make its mark on Mars exploration. Letting this mission slip would be bad optics.

So there's genuine urgency. But urgency often leads to poor decisions, especially when you haven't resolved the fundamental question of what the mission is supposed to do.

The Science Versus Engineering Debate

Inside NASA, this is where the real disagreement lives.

One camp says: "Look, we have

This isn't radical. It's how NASA has operated for decades. When you're sending hardware to an expensive destination, you maximize its science return. It's basic stewardship.

They've got specific ideas:

-

High-resolution camera: The Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter's best camera is 20 years old. Every year, dust settles on lenses, degrading image quality. A new camera would revolutionize Mars surface science for the next decade.

-

Magnetometer: Mars's magnetic field is one of the red planet's great mysteries. Unlike Earth, Mars has a weak, patchy global magnetic field. Understanding why requires instruments in orbit.

-

Spectrometer: Detecting near-surface water ice is critical for future human missions. Current instruments can map subsurface ice, but improved spectroscopy would dramatically improve accuracy.

-

Space weather payload: Measuring solar radiation and charged particles helps understand Mars's atmosphere and informs human mission planning.

Some scientists even proposed repurposing instruments from the canceled Mars Ice Mapper mission. That satellite was killed in budget cuts, and some of its hardware exists. Why not use it?

The counter-argument from other NASA leaders is simpler: "The Congressional language says 'telecommunications orbiter.' It doesn't say anything about science. We can read that as spelling out a comms-only mission. Adding science changes the mission. That might violate Congressional intent. Plus, adding science complexity adds risk, adds schedule pressure, and makes evaluation harder."

There's a kernel of truth here. More systems equal more things that can break. More complexity equals harder testing and longer development schedules. And yes, the Congressional language is ambiguous enough that NASA's interpretation matters.

But here's the thing: legislation is often vague. Agencies have discretion in implementation. NASA has routinely added science payloads to missions that weren't originally specified as science missions. It's standard practice.

The real question is: does Isaacman, as the new administrator, have the political will to push for a more ambitious mission? Or will he play it safe and stick with what the language technically allows?

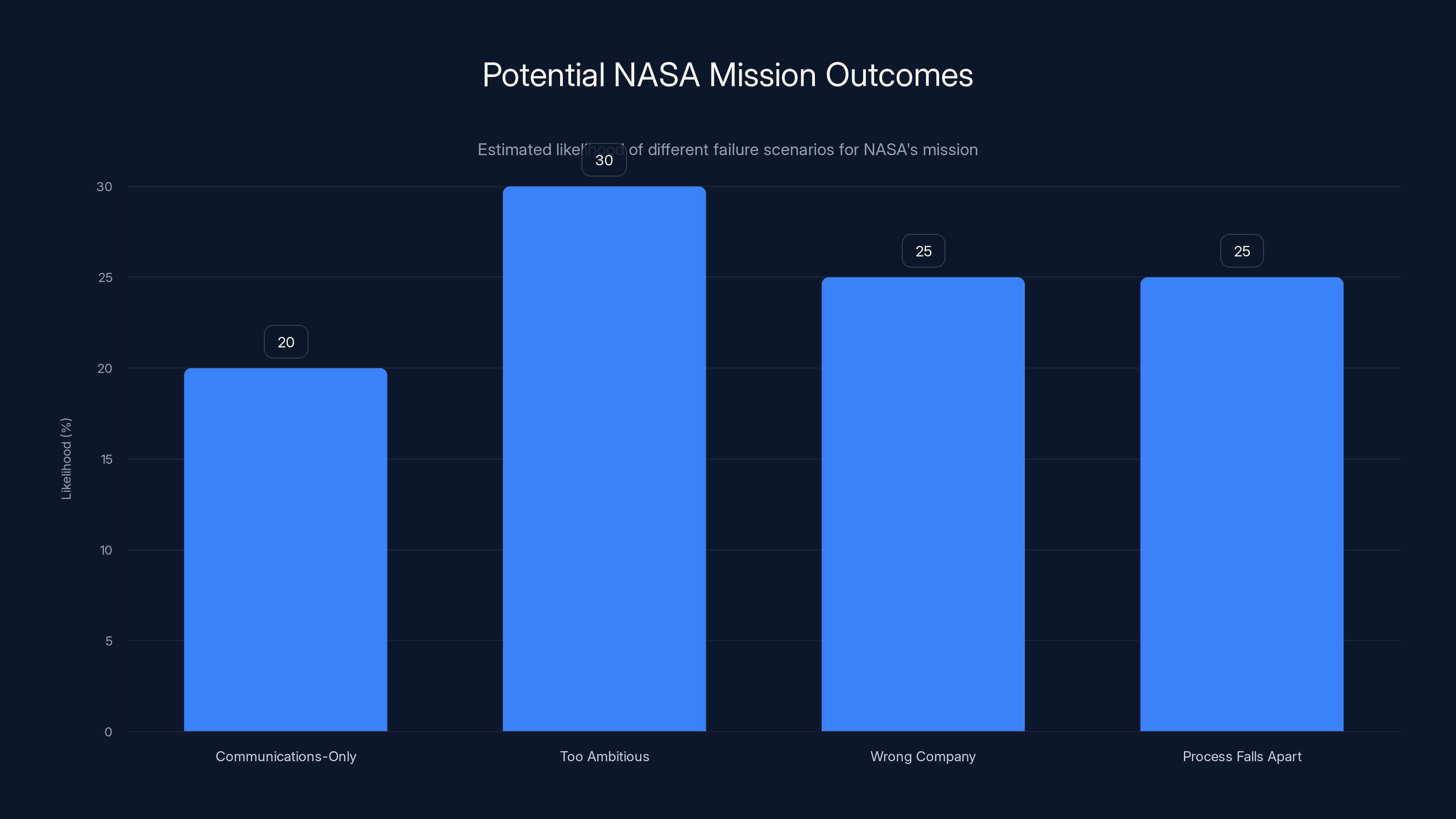

This chart estimates the likelihood of different failure scenarios for NASA's mission. The 'Too Ambitious' scenario is considered the most likely to lead to failure. (Estimated data)

The Competitive Landscape Is Complicated

Let's talk about who might actually win this contract.

Rocket Lab is the obvious candidate given the Congressional language. They've got funding from the 2024 Mars Sample Return studies. They've proposed a telecommunications orbiter concept. They're hungry to get to Mars. But they're also relatively small and have limited Mars experience. Their New Shepard suborbital flights are successful, but orbital Mars missions are a different beast.

Blue Origin also received Mars Sample Return funding but the Congressional language seems less targeted at them. They've got massive resources and serious space plans, but they're more focused on lunar development right now.

SpaceX isn't eligible under the current language because they didn't get Mars Sample Return funding in the eligible years. That's interesting because SpaceX is probably the most technically capable company for this mission. Starship could launch this orbiter easily. But they're excluded by definition.

Traditional contractors like Lockheed Martin and Boeing have Mars experience but aren't mentioned in the Congressional language. They're probably out unless NASA interprets the rules differently.

So you've got a situation where the company most people think should win—Rocket Lab—might win anyway, but the competitive process isn't really open. That's awkward.

NASA could try to open it up by reinterpreting the language, but that risks Congressional blowback. Congress controls funding. Mess with what Congress intended, and they can make your life difficult in the next appropriations cycle.

Isaacman has to navigate between technical excellence, Congressional intent, political realities, and fair competition. No pressure.

What Happens If NASA Gets This Wrong

Let's think through the failure scenarios.

Scenario 1: Communications-Only Mission, No Science. NASA plays it safe. Builds a straightforward relay orbiter. Launches in 2028. It works fine. But NASA misses an opportunity to add high-resolution imaging and magnetometry capabilities that would have been available nowhere else. In 2030, when a new science mission could have used that data, NASA has to explain why they didn't grab it when they had the chance.

Scenario 2: Mission Becomes Too Ambitious. NASA adds too many science instruments. Schedule slips. Development costs balloon. By 2027, the project is over budget and behind schedule. The 2028 launch window slips to 2030. By then, the political climate has changed, budgets have shifted, and the mission gets canceled entirely. You end up with nothing.

Scenario 3: Wrong Company Wins. Due to the Congressional language, a company wins that technically isn't the best choice. The mission succeeds, but industry observers note that the better approach from a competing company was locked out by politics. NASA's credibility takes a hit. Next time Congress has to fund something like this, there's more skepticism.

Scenario 4: The Process Falls Apart. NASA can't reach consensus on what the mission should be. Internal debates drag on. The September 2026 obligation deadline passes. Congress gets angry. Isaacman gets questioned in oversight hearings. The whole thing becomes a political football.

None of these are great outcomes.

The best outcome is Option 2: communications plus modest science package, competitive evaluation, launch in 2028, mission succeeds, everyone learns something. But that requires Isaacman to make a decision, communicate it clearly to Congress, and stick with it. That's harder than it sounds.

The Bigger Picture: Mars Policy for a Decade

This decision matters beyond the specific orbiter.

NASA is theoretically committed to returning Mars samples to Earth someday. That's been official policy for over a decade. But nobody knows exactly when or how. The commercial design studies from 2024 were meant to figure out faster, cheaper approaches. This orbiter would support that mission.

But the orbiter itself signals something about NASA's future Mars strategy. If NASA puts science instruments on it, that says: "We're still driving Mars exploration through science priorities." If NASA keeps it communications-only, that says: "We're stepping back and letting commercial partners take the lead on deep Mars work."

That's a philosophical shift. It affects everything from workforce priorities to technology development to international partnerships.

It also affects budget planning. If this orbiter is just comms, then NASA needs different funding for Mars science. That means fighting for budget in other areas. If the orbiter does science, then you've gotten science capability without a separate budget line. From a fiscal perspective, option two is obviously smarter.

Isaacman will inherit the Mars strategy question regardless. But how he handles this orbiter decision will define his approach to the whole Mars program.

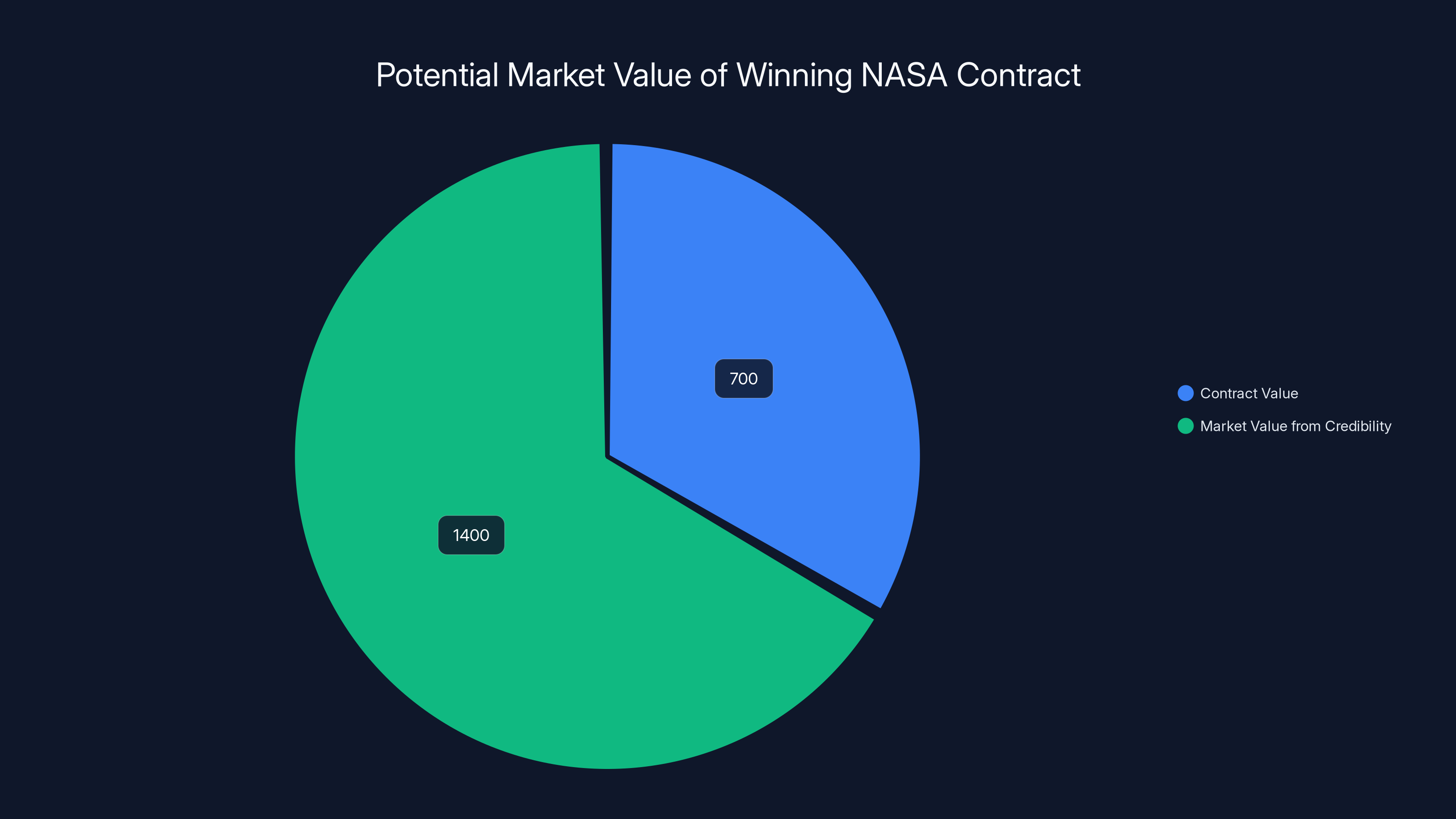

Winning the NASA contract is estimated to have a market value twice the contract's worth, highlighting the importance of credibility in the commercial space industry. (Estimated data)

Internal NASA Politics and Decision-Making

Behind the technical arguments are real institutional tensions.

Science divisions at NASA want the instruments. They see this as a once-in-a-decade opportunity. Missing it feels like failure. But exploration divisions and mission managers worry about complexity and schedule risk. They've seen ambitious missions slip and burn.

NASA's new administrator has to navigate between these camps. He doesn't have decades of institutional knowledge. He doesn't owe favors to specific science communities. He might actually be the right person to cut through the debate and make a decision. Or he might defer to career staff and institutional precedent.

One telling detail: NASA's official statement to press said they'd procure "a high-performance Mars telecommunications orbiter." Notice what's missing? Any mention of science. That suggests the official position is leaning toward communications-only.

But sources close to Isaacman indicated he hasn't personally decided yet. There's a gap between what the public relations team is saying and what the administrator has actually committed to.

That gap is where the real decision-making happens.

The Commercial Space Industry's Role

This orbiter decision reflects a broader shift in how NASA does business.

For decades, NASA built everything in-house or gave contracts to traditional aerospace companies. That model is changing. Commercial companies now build spacecraft for NASA. Commercial rockets launch NASA missions. Commercial space stations are coming. NASA is becoming more like a customer than a builder.

This orbiter decision is a test case for that model. Is a relatively new commercial company like Rocket Lab ready for a Mars mission? Can they deliver on time and budget? Will they push innovation, or does their inexperience create risk?

If Rocket Lab wins and succeeds, it validates the commercial space model and opens doors for more missions. If they win and fail, it discredits the whole approach and pushes NASA back toward traditional contractors.

That's why the politics around this matter. It's not just about one spacecraft. It's about NASA's strategy for the next decade.

Commercial companies understand this too. Whoever wins this contract gets something more valuable than the $700 million: credibility as a Mars-capable company. That opens doors to other customers, other missions, other opportunities. The market value of winning is probably double the contract value.

So you're going to see serious proposals from eligible companies. And you're going to see pressure from ineligible companies arguing the Congressional language is unfair.

What Congress Actually Wanted (And Didn't Say)

The fact that a specific staff member drafted the language with such specific contractor references tells you something happened behind the scenes.

Senator Cruz's office was interested in this mission. Maddie Davis, the key staff member, presumably did homework on available options. They concluded Rocket Lab was the right choice. Rather than say that directly, they embedded the preference in legislative language.

This is standard practice in Congress. When lawmakers want specific outcomes, they write bills that make those outcomes likely. It's not corruption; it's how the system works. Special interests lobby for favorable language. Agency staff work with Congressional staff to structure bills that achieve policy goals.

But it creates inefficiencies. When you constrain the competitive pool, you might not get the best solution. You get the solution that fits your pre-determined preference.

NASA leadership knows this happened. They're not naive. The question is whether they accept it or push back.

Some NASA officials might see the Congressional language as irritating constraint that narrows their options unfairly. Others might see it as fine guidance that actually clarifies what Congress wants. Either way, they have to work within it.

Unless Isaacman decides to interpret the language more loosely. He could argue that the spirit of the legislation is supporting commercial partners for Mars work, not literally restricting to specific contractors. That's a defensible reading. Congress would probably go along with it, especially if Isaacman explained it clearly.

But that requires confidence and political capital. Isaacman has both as a successful entrepreneur, but he's new to government. He might not want to pick a fight with Congress in his first months.

NASA's Mars budget for 2026 is more flexible than it appears, with

The Technical Requirements Nobody's Talking About

Let's get nerdy for a second.

A Mars telecommunications orbiter needs specific capabilities. It has to receive weak signals from surface assets (rovers, landers, future human missions) and relay them back to Earth with high fidelity. That means a powerful transmitter, a sensitive receiver, and sophisticated communications electronics.

The spacecraft also needs to survive in Mars orbit, which means dealing with radiation, solar variability, dust, and other hazards. Reliability over a multi-year mission is critical. You can't service this thing. When it breaks, it breaks.

Bandwidth requirements are increasing. Early Mars rovers transmitted kilobits per second. Modern rovers and future landers will generate orders of magnitude more data. A new orbiter needs to handle that. It needs to be upgradeable too. You don't want to launch a mission in 2028 that's already obsolete by 2032.

These requirements influence the design. A more capable orbiter is heavier, more expensive, requires more power. You have to balance capability against cost and complexity.

The spacecraft bus—the basic platform everything hangs on—is crucial. Do you use an existing bus design from another mission and adapt it? Or build from scratch? Existing is faster and cheaper. From scratch is potentially optimized but riskier.

None of these technical requirements are contentious. Everyone agrees on them. The debate is about cost, complexity, and what's actually necessary versus nice-to-have.

A communications-only mission needs maybe two or three specialized subsystems. Add science instruments and you need six or seven more. That complexity ripples through design, testing, validation, and operations.

Isaacman's team needs competent spacecraft engineers evaluating these tradeoffs. Congress doesn't want to hear that science instruments add too much complexity. Congress wants to hear: "We'll build a great orbiter that relays signals and does science." But engineers know that's simplistic.

The Budget Situation Is Messier Than You Think

NASA's fiscal 2026 budget included

There's also a bigger wedge of funding for Mars commercial payload delivery programs. This is money NASA set aside to support commercial companies developing Mars delivery systems.

So NASA's actual Mars budget for 2026 is more flexible than the headline

Budget flexibility is a form of power. It lets you make decisions that seem constrained but actually aren't. Isaacman probably hasn't fully realized the flexibility he has. Or maybe he has, and that's what's holding up a decision.

But there are limits. If he moves too much money around, it affects other programs. NASA's Mars budget is finite. Robbing Peter to pay Paul works until you run out of Peters.

Timeline: When Decisions Need to Happen

Here's the calendar:

Now (January 2026): Isaacman settling into role, reviewing options, getting briefed by career staff. Internal debates about science versus comms.

February-March 2026: Decision window. Isaacman needs to decide what the mission is before drafting the procurement request.

April-May 2026: Procurement request released to industry. Companies start drafting proposals.

June 2026: Proposal submissions due. Evaluation period begins.

July-August 2026: Negotiations with selected contractor(s). Contract terms finalized.

September 2026: Contracts must be awarded and funding obligated by end of fiscal year (Sept 30).

Fall 2026-2028: Spacecraft development and testing.

Late 2028: Launch window. Spacecraft launches to Mars.

That's a tight schedule. Things slip. Personnel change. Political priorities shift. But it's doable if everyone moves quickly and decisively.

The key chokepoint is now: February-April 2026. That's when Isaacman has to decide. If he pushes the decision into May or June, schedule pressure intensifies. If he pushes it to July, the whole thing becomes at-risk.

The Mars Telecommunications Orbiter project is influenced by funding deadlines, launch timing, vision choices, and commercial competition. Estimated data.

What Success Would Actually Look Like

Let's imagine a good outcome.

Isaacman announces in March 2026 that NASA will procure a telecommunications orbiter with modest science capability: a high-resolution camera, magnetometer, and spectrometer. The mission is streamlined for 2028 launch but not compromised.

NASA releases a procurement that's technically sound but flexible enough to allow multiple approaches. Rocket Lab responds with a proposal. So does Blue Origin. Maybe Lockheed Martin finds a way to participate.

NASA evaluates on technical merit and cost. The winner is selected. Contract signed by September 2026. Funding obligated. Congress is happy because their intention was honored: a Mars mission supported by commercial partners.

The spacecraft launches in late 2028 or early 2029. By 2030, it's in Mars orbit, relaying data from surface missions. The camera returns stunning images. The magnetometer reveals new insights about Mars's magnetic field. Scientists publish papers. The mission's ROI justifies the investment.

Ten years from now, nobody remembers the debate. They just remember the scientific discoveries enabled by this orbiter.

That's success. It requires one decisive administrator, clear communication with Congress, technical expertise in evaluation, and slightly lucky timing. Not impossible.

The Broader Mars Exploration Strategy

This orbiter doesn't exist in isolation. It's part of a larger Mars program.

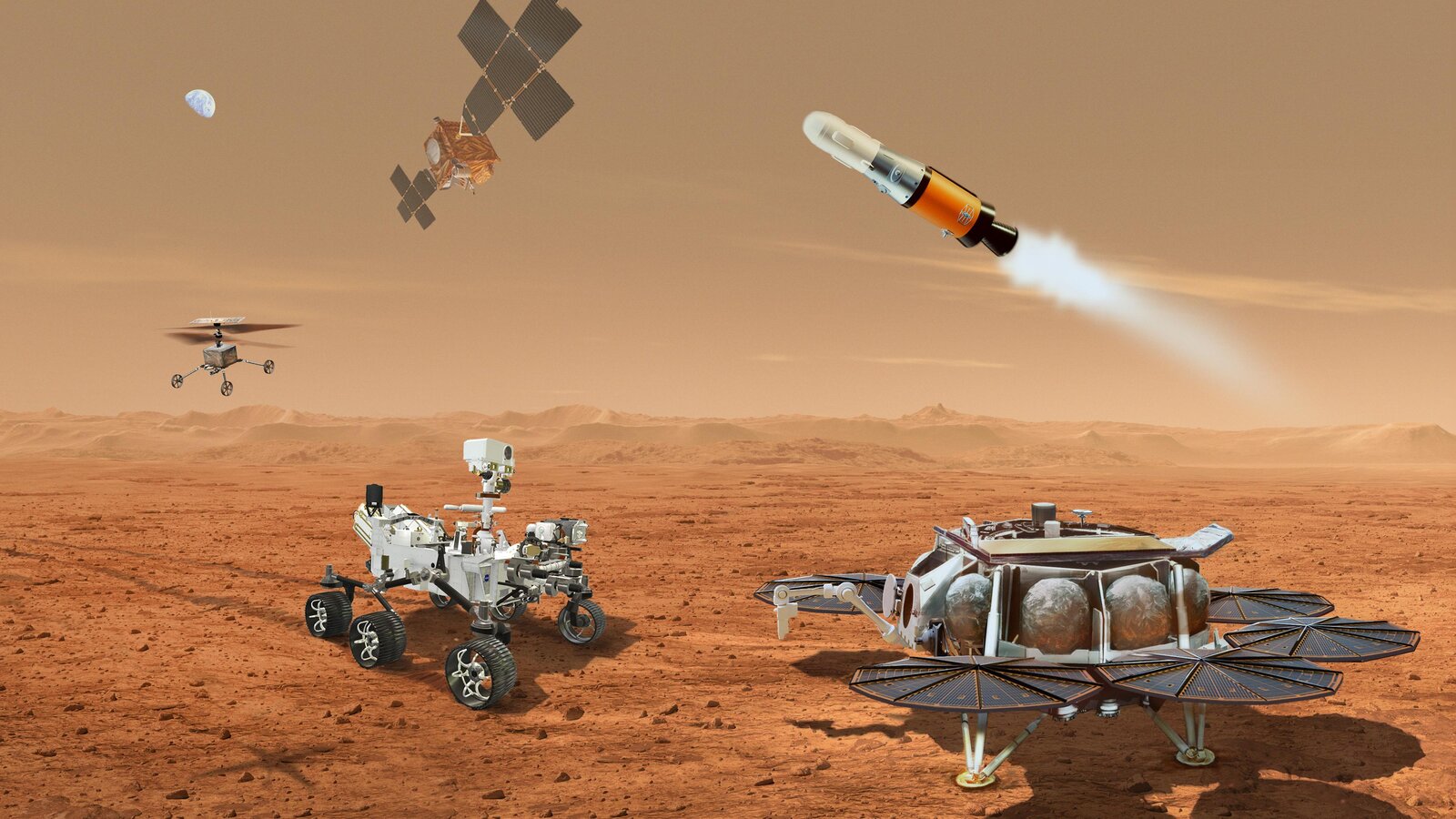

NASA has rovers on the surface (Curiosity and Perseverance). These rovers transmit data through relay orbiters. Eventually, NASA wants to return samples from Perseverance back to Earth. That mission needs relay capacity. The new orbiter could support that.

Longer term, NASA has vague plans for eventual human Mars missions. But that's probably 10-15 years away. By then, everything about Mars infrastructure will look different. The orbiter you're building today might be outdated by then.

So this mission lives in an awkward time horizon. It's not for current rovers (they work fine with existing relays). It's for missions in the 2030s and 2040s. By then, technology will have advanced. New companies will exist. New competitive dynamics will emerge.

NASA's job is to build something good enough to last, flexible enough to adapt, and reliable enough to depend on. That's harder than it sounds.

The orbiter is also a test bed for new communications technologies. Higher data rates. New frequencies. Autonomous relay management. These capabilities matter as Mars exploration gets more complex.

That's why adding science instruments makes sense. You're upgrading the infrastructure anyway. Get science value out of it.

Political Implications and the Trump Administration

The Trump administration has Mars ambitions. They talk about going to Mars. They're pushing accelerated timelines and commercial partnerships.

This orbiter fits that narrative nicely. It's a Mars mission happening under Trump's watch. It's commercial (or partially commercial). It's infrastructure investment for future ambitious missions.

But it also has budget implications. Is $700 million well-spent on a relay, or should it go toward human lunar exploration? The administration probably wants to claim credit for Mars while actually investing in the Moon (which is where they want humans to go).

Isaacman, as administrator, has to balance these political realities with technical requirements. He's been recruited partly because he's a successful entrepreneur who understands business and gets things done. The administration expects him to cut through institutional inertia and deliver.

That's a lot of pressure for a guy six weeks into the job.

International Dimensions Nobody's Mentioning

Mars exploration has become more international. China is conducting Mars missions. Russia and Europe have partnerships. India is active. Japan is exploring.

When the US delays or cancels Mars missions, that affects the international community. It affects data sharing. It affects who gets to study Mars and how. There's prestige and geopolitical competition involved.

A communications orbiter that serves everyone—all Mars missions, not just NASA's—is strategically valuable. It positions the US as supporting Mars exploration broadly, not just pursuing narrow national interest.

That's not the main driver of this decision, but it's in the background. NASA leadership thinks about these things.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

NASA has made aerospace procurement mistakes before. Lessons from past failures might actually be relevant here:

- Underestimating complexity: Spacecraft are never as simple as initially planned. Add contingency.

- Schedule optimism: Add margin to timelines. The Artemis program learned this the hard way.

- Cost underruns: When things go wrong, they go expensive. Budget accordingly.

- Changing requirements mid-development: Lock down the mission definition early. Changes downstream multiply costs.

- Too many stakeholders in the decision: Too many cooks create slow decision-making. Isaacman needs authority to decide and stick with it.

The good news is these are known failure modes. NASA can plan accordingly if leadership recognizes them.

What the Competitive Space Industry Brings to the Table

Rocket Lab, Blue Origin, and other commercial companies bring something traditional contractors don't: hunger to prove themselves.

They're not satisfied with incremental improvements. They want to innovate, reduce costs, and demonstrate capability. That's valuable. It pushes NASA toward better solutions.

But inexperience is also real. A company that's never built a Mars spacecraft before can make mistakes that experienced contractors avoid. That's a legitimate concern.

The best outcome probably involves experienced contractors working with commercial companies on hybrid approaches. But the Congressional language might not allow that.

Potential Workarounds and Creative Solutions

NASA could potentially resolve some of these tensions through creative contract structuring:

- Phased approach: First phase is comms-only orbiter. Second phase adds science instruments once the comms mission is mature.

- Industry partnership: Award primary contract to one company but require partnerships with others on science subsystems.

- Government-furnished equipment: NASA provides science instruments; contractor integrates them into spacecraft.

- Option clauses: Base contract is comms-only. Options for science instruments if schedule permits.

These approaches let you satisfy Congressional intent while adding capability. They require clever contracting but are technically feasible.

The Decision Deadline Approaches Fast

In aerospace, deadlines are real. You can't launch a spacecraft at the exact moment you decide to. There's minimum lead time for vehicle development, testing, and integration.

For a late-2028 launch, critical design reviews need to happen in 2027. Component procurement starts in 2026. The spacecraft needs to be designed by mid-2026. That means proposals need to be evaluated and contracts awarded by September 2026, which means proposals need to be submitted in June-August 2026, which means the request needs to be released in April-May 2026.

So Isaacman's decision window is genuinely narrow. February-March 2026. Miss that window and the schedule slips. Schedule slip means missing the launch window. Miss the launch window and you're done.

NASA's leadership understands this. That's why people are starting to ask publicly: what's the decision?

Forecasting the Actual Outcome

Based on institutional dynamics and political realities, here's my best guess:

Isaacman will decide on communications-plus-modest-science approach. It splits the difference. Congress gets their Mars mission. Science community gets their instruments. Commercial companies get work. Schedule stays achievable.

Rocket Lab will probably win because the Congressional language advantage is significant. They'll partner with an experienced contractor for spacecraft bus and mission operations.

The mission launches in late 2028 or early 2029. It works. Congress feels vindicated. Everyone moves on to the next decision.

Will it be optimal? Probably not. Will it satisfy everyone? No. Will it work? Likely yes.

That's how big government decisions usually turn out. Not perfect, but functional.

FAQ

What is a Mars telecommunications orbiter?

A Mars telecommunications orbiter is a spacecraft that orbits Mars and relays communications between surface assets (rovers, landers) and Earth. It receives weak radio signals from Mars surface missions and transmits them back to Earth with sufficient power to be detected. NASA currently relies on the 20-year-old Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter for most relay traffic, making a new orbiter critically important for ongoing and future Mars missions.

Why does NASA need a new Mars telecommunications orbiter now?

NASA's current relay spacecraft are aging. The Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter launched in 2006 and has far exceeded its original lifespan. MAVEN, another key relay spacecraft, recently failed. Without a new orbiter in place, NASA's future Mars missions—including potential sample return campaigns and human exploration preparation—would lose their primary communications infrastructure. Congress recognized this urgency and appropriated $700 million specifically for a new Mars Telecommunications Orbiter in supplemental funding.

What's the debate about adding science instruments to the orbiter?

NASA scientists argue that since the orbiter is already going to Mars, adding scientific instruments—like a high-resolution camera, magnetometer, or spectrometer—would provide tremendous value at a modest incremental cost of about $200 million. Other NASA leaders argue that the Congressional language specifies a "telecommunications orbiter," implying a communications-only mission, and that adding science instruments increases complexity and schedule risk. The debate reflects competing visions: maximize science returns versus minimize risk and stay within the original mission scope.

Who might win the contract to build this orbiter?

The Congressional language restricts eligibility to companies that received funding for commercial Mars Sample Return design studies in fiscal year 2024 or 2025, which appears designed to favor companies like Rocket Lab. However, the interpretation of this language is somewhat flexible, and NASA could potentially broaden the competitive pool. The specific contractor selection depends on NASA's interpretation of Congressional intent and the evaluation of technical proposals when they're received.

What happens if NASA misses the deadline?

If NASA doesn't obligate the $700 million in funding by September 30, 2026, Congress could repurpose the money to other programs or require new legislation to continue the project. More critically, missing the obligation deadline jeopardizes the late-2028 launch window—the next opportunity to send a spacecraft to Mars given orbital mechanics. Missing that launch window means waiting until 2030 or beyond, delaying Mars infrastructure by years and potentially derailing dependent missions.

How does this decision affect future human Mars missions?

Any human mission to Mars requires robust telecommunications infrastructure to maintain contact with crews and transmit data. This orbiter would provide the foundational relay capacity for decades of future Mars work, including potential human expeditions. If the orbiter includes scientific instruments, it would also provide critical data about Mars's environment and resources—information astronauts would need to plan safe and effective operations on the surface.

Why is Congressional language about contractor eligibility controversial?

When Congress specifies particular contractors in legislation, it constrains competition and raises fairness concerns. Other companies may have superior technical solutions but are excluded by definition. This can also send signals to the aerospace industry about which companies Congress favors, affecting how companies allocate research resources and form partnerships. However, Congressional intent does matter legally and practically, so NASA has to work within these constraints.

What role does commercial industry play in this mission?

Unlike traditional government-built spacecraft, this orbiter will be built by commercial companies. This reflects NASA's shift toward partnering with the private sector rather than building everything in-house. Commercial companies bring innovation, cost competition, and new approaches. However, less experienced commercial firms may lack the heritage and proven reliability of traditional aerospace contractors, creating a tension between innovation and risk management.

Conclusion: A Decision That Matters More Than It Appears

On the surface, picking a spacecraft for Mars communications sounds like a technical decision. Dig deeper, and it's about Mars strategy, commercial space partnerships, Congressional intent, budget priorities, and whether NASA is still driving planetary exploration or stepping back.

Jared Isaacman has inherited this decision at a critical moment. The window to decide and act is narrow. The stakes are higher than the headline suggests.

If done well, this mission could be a template for how NASA and commercial space work together. If done poorly, it could set precedents everyone regrets.

The decision matters for Mars exploration in the 2030s and 2040s. It matters for which companies develop Mars capability. It matters for whether NASA remains committed to scientific discovery or pivots toward infrastructure and logistics.

Everyone inside and outside NASA is watching to see what Isaacman decides. The quiet deadline of September 2026 is approaching. The clock is ticking.

For a decision that sounds administrative, this one will shape the future of space exploration in ways we're only beginning to understand. That's why it mattered enough for Congress to fight over in appropriations bills. That's why NASA career staff are divided on the best path forward. And that's why the new administrator's decision will be remembered when this orbiter is relaying data from the red planet for the next two decades.

Key Takeaways

- NASA must obligate $700 million in funding by September 30, 2026, forcing a decision timeline of just 9 months on the Mars Telecommunications Orbiter design and contractor selection

- Internal NASA debate centers on whether the orbiter should be communications-only or include scientific instruments like high-resolution cameras and magnetometers that could be added for about $200 million

- Congressional language appears designed to favor Rocket Lab, creating questions about fair competition versus intentional contractor preference in government procurement

- Missing the late-2028 launch window would delay Mars infrastructure until 2030 or beyond, cascading delays through the entire Mars exploration program

- The decision signals NASA's broader Mars strategy: whether science priorities drive exploration or commercial partnerships and infrastructure take precedence

Related Articles

- NASA's Commercial Space Station Crisis: Senate Demands Timeline [2025]

- NASA's Science Budget Crisis Averted: What Congress Just Saved [2026]

- Satellite Ground Stations: The Bottleneck Reshaping Space Infrastructure [2025]

- Blue Origin's New Glenn Third Launch: What's Really Happening [2026]

- Blue Origin's TeraWave Megaconstellation: The 6Tbps Satellite Internet Game Changer [2025]

- The Space Launch Race Heats Up: Ariane 6, India's Falcon 9 Clone, and the Future [2025]

![NASA's Mars Orbiter Decision: What's at Stake [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/nasa-s-mars-orbiter-decision-what-s-at-stake-2025/image-1-1769789502405.jpg)