Satellite Ground Stations: The Bottleneck Reshaping Space Infrastructure [2025]

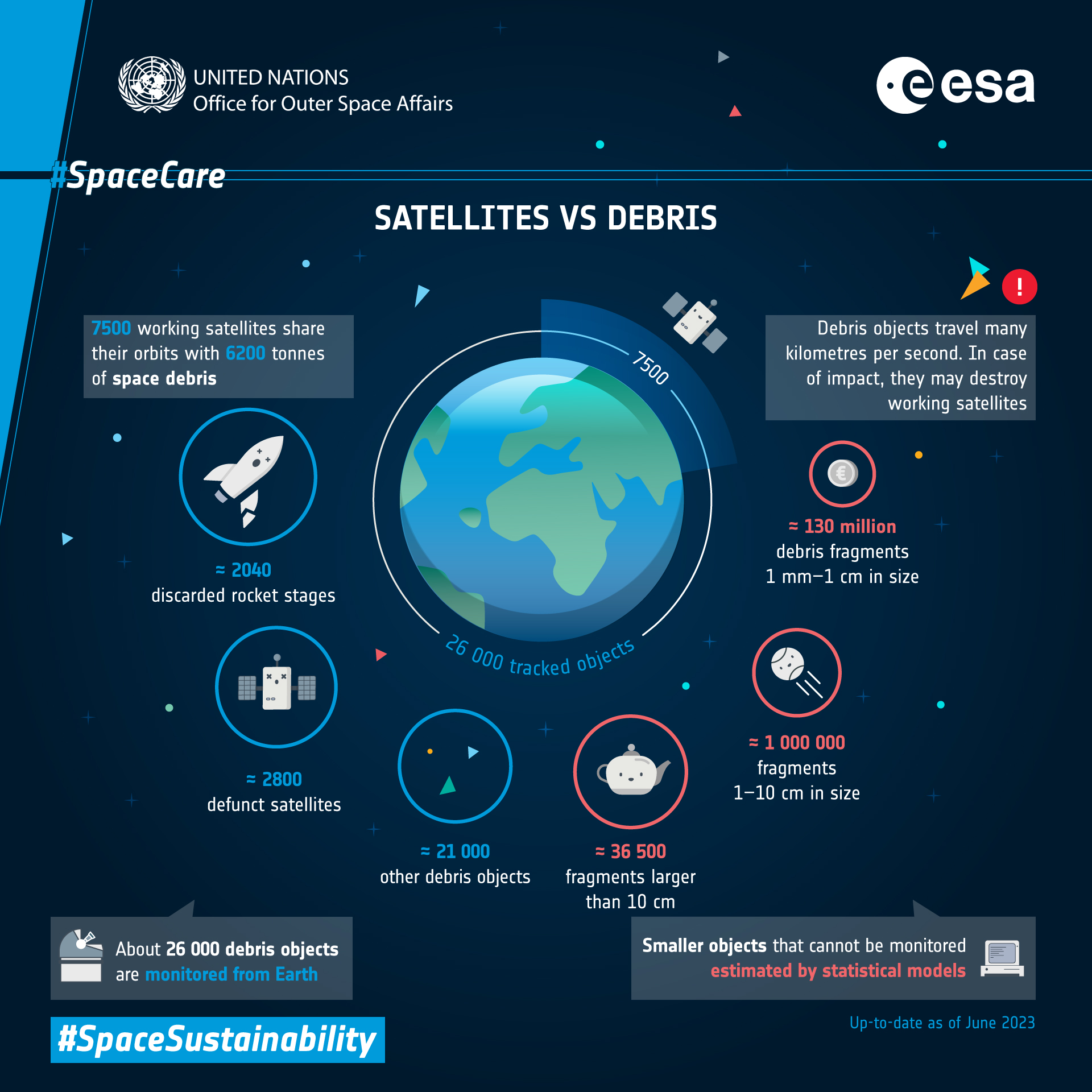

Here's a problem nobody talks about at dinner parties, but it's reshaping how humanity uses space. We're launching satellites at an unprecedented pace—thousands of them. They're collecting terabytes of data every single day. Imaging Earth, tracking weather, enabling global communications, powering machine learning models trained on orbital data. But there's a massive, creeping crisis hiding in the details.

The satellites work fine. The issue is getting the data down.

Satellites orbiting Earth beam down enormous streams of information, but most of the world's ground stations—the facilities that receive this data—were built a decade or more ago. They're aging. They're slow. They weren't designed for the volume of data modern satellites generate. Imagine building a factory capable of producing 1,000 widgets per day, then suddenly your supply chain demands 100,000 widgets daily. That's where the space industry is right now.

In January 2025, a company called Northwood Space announced a

Let's break down why ground stations matter, why the existing ones are failing, and what companies like Northwood are doing to fix it.

TL; DR

- The data problem is real: Satellites are generating exponentially more data than ground stations can handle, creating a critical bottleneck in space operations

- Legacy systems are obsolete: Most commercial ground stations were deployed 10+ years ago and lack the capacity for modern satellite constellations

- Phased-array technology changes the game: Companies like Northwood Space use electronically-steered antennas instead of mechanical dishes, enabling simultaneous multi-satellite tracking

- Military demand is driving adoption: The US Space Force awarded $49.8 million to Northwood to augment the Satellite Control Network, validating the market need

- The opportunity is massive: Global ground station infrastructure requires billions in capital investment as orbital data volumes continue exponential growth through 2030

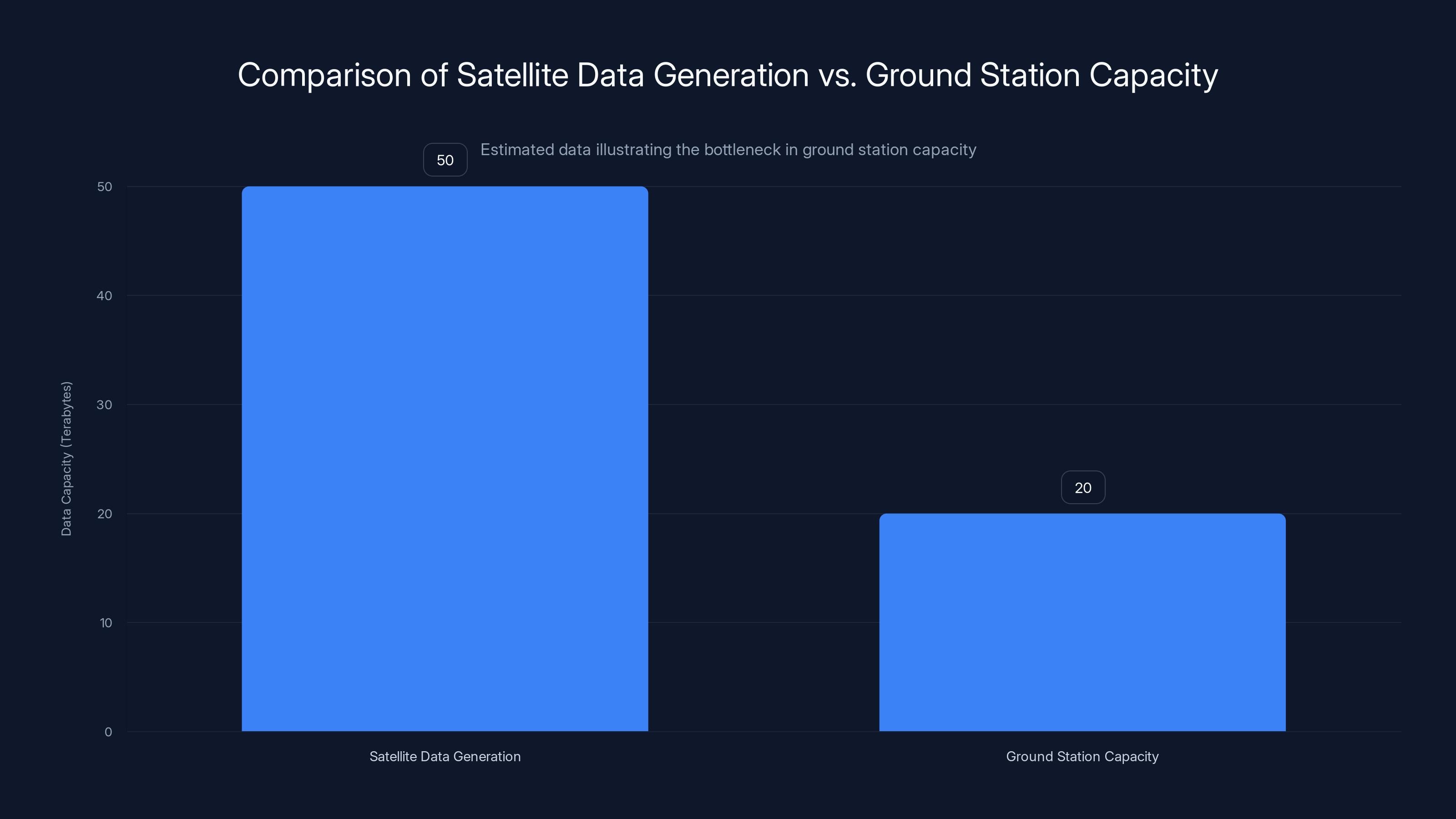

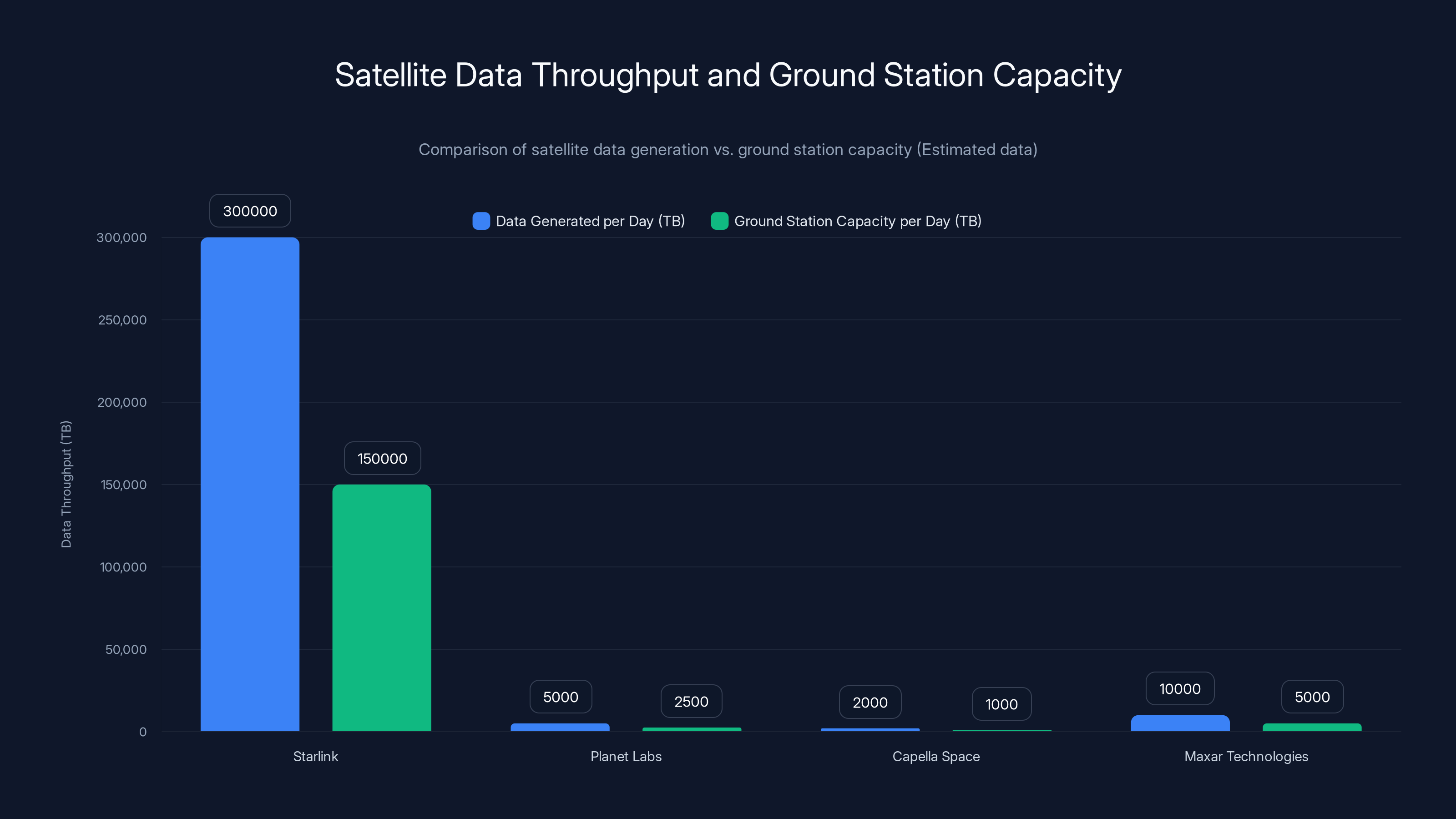

Estimated data shows that modern satellites generate over 50 terabytes daily, while many ground stations can only handle about 20 terabytes, highlighting a significant capacity bottleneck.

The Satellite Explosion and Its Hidden Consequence

If you've been paying attention to space news over the past five years, you've seen the numbers. SpaceX's Starlink constellation has grown to over 6,000 satellites. Planet Labs, Capella Space, Maxar Technologies, and dozens of other companies operate Earth observation spacecraft. Then there's Kuiper from Amazon, One Web, and countless others launching mega-constellations.

Each satellite generates data at a rate that would've seemed absurd just ten years ago. A single imaging satellite might produce 50 terabytes per day. Communications satellites handle petabits of data flowing through their transponders. When you multiply this across thousands of operational spacecraft, the total data throughput explodes.

But here's what most people miss: the satellites themselves aren't the bottleneck anymore. We figured out how to build them, launch them, and keep them operational. The constraint is on the ground.

When a satellite passes over a ground station—which might happen only once or twice per day depending on the orbit—it needs to download all of that data in a narrow window, typically measured in minutes. If the ground station can't receive data fast enough, that information is lost. The satellite circles the globe with data still on its storage drives, waiting for the next ground station pass. This introduces delays, reduces the value of the data, and limits the number of satellites any single operator can support.

For companies building Earth observation constellations, this becomes a real problem. If you've got 100 satellites and your ground stations can only download from 50 of them effectively, you're losing 50% of your revenue potential. For communications companies operating global networks, slow ground stations mean congestion and reduced capacity.

This is why Northwood Space's timing is perfect. The data bottleneck isn't theoretical anymore—it's a concrete constraint limiting the growth of the space economy.

Estimated data suggests that Northwood's investment focus is distributed across market growth, defensible technology, and addressable market, with each contributing significantly to their investment thesis.

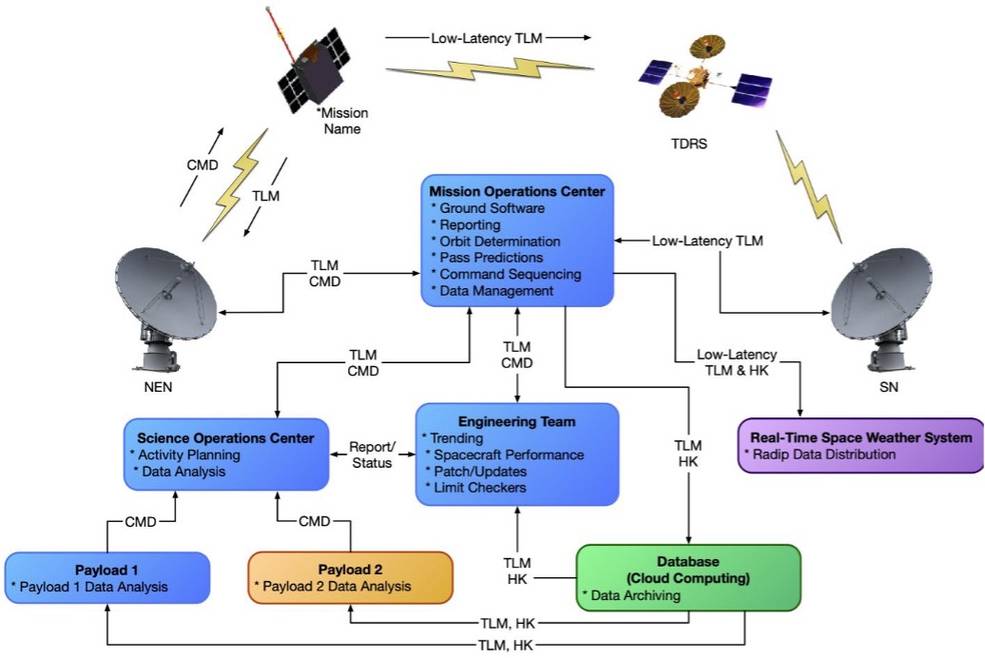

Understanding Ground Station Architecture

Ground stations aren't complex in concept. They need to do three things: receive signals from space, transmit signals to space, and process the data coming in. The traditional approach used parabolic dish antennas—the kind you've probably seen in satellite imagery. These dishes point directly at a target satellite, collect the radio signals, and transmit them to receivers.

This architecture has served the industry well for decades. It's reliable, proven, and works. But it has fundamental limitations.

First, mechanical steering is slow. A large dish antenna weighs hundreds of tons. Pointing it at different satellites requires moving all that mass, which takes time. You can't instantly switch from tracking one satellite to another.

Second, a single dish can only point at one satellite at a time. If you need to communicate with multiple satellites simultaneously—which is increasingly common—you need multiple dishes. This multiplies your infrastructure costs exponentially.

Third, parabolic antennas require a direct line of sight to their target. They're not flexible. They can't adapt to changing orbital geometries without moving the entire mechanical structure.

Consider the math: a traditional ground station might have a handful of dishes. Each dish can handle communication with a limited number of satellites. To support a modern mega-constellation of 5,000+ satellites, you'd need dozens of ground stations spread globally, each with multiple dishes. The capital cost becomes astronomical, the operational complexity explodes, and you're still struggling to achieve the throughput you need.

Phased-Array Antenna Technology: A Paradigm Shift

Instead of moving a mechanical dish to point at different targets, phased-array antennas use something more elegant: they steer an electronic beam.

Here's how it works in simple terms. A phased-array antenna is made up of many small antenna elements arranged in a grid. Each element can emit or receive radio signals. By precisely controlling the timing and phase of signals across these elements, you create a coherent beam that points in a specific direction. Want to point the beam somewhere else? Don't move the antenna—just adjust the electronic timing across the elements. It happens in milliseconds.

The implications are profound.

First, you can switch between different satellites almost instantly. No waiting for mechanical movement. A ground station can handle dozens of satellite passes in rapid succession without any lag.

Second, phased-array technology enables simultaneous multi-satellite tracking. By creating multiple beams from a single array, you can communicate with multiple satellites at the same time. One array could theoretically handle dozens of satellites simultaneously, depending on frequency and power constraints.

Third, the antenna is compact. Phased-array antennas don't require the massive mechanical structure of traditional dishes. They're lighter, smaller, and require less infrastructure. They can be deployed in more locations, with lower capital cost.

Northwood Space's "Portal" system is a phased-array implementation designed specifically for satellite operations. According to the company's technical demonstrations, a Portal array measuring 8 to 15 meters in area delivers equivalent capability to a 7-meter parabolic dish, but with electronic steering instead of mechanical movement.

The company has shown the ability to manufacture eight Portal arrays per month. By January 2025, they'd already deployed operational systems across two continents.

Estimated data shows a significant gap between data generated by satellites and the capacity of ground stations to receive it, highlighting the bottleneck in data handling.

The Competitive Landscape in Ground Station Technology

Northwood Space isn't alone in recognizing this opportunity. The ground station market includes roughly half a dozen major players, ranging from long-established aerospace contractors to newer venture-backed startups.

Traditional aerospace companies have strong institutional knowledge and existing relationships with government customers, but they've been slow to innovate in ground station design. They're comfortable with the parabolic dish approach because it's proven and their teams know it deeply.

Newer companies are approaching the problem from different angles. Some are focusing on software-defined radio technology, which makes ground stations more flexible and reconfigurable. Others are exploring electronically-steered phased-array antennas like Northwood, or distributed antenna networks, or even airborne platforms.

What distinguishes Northwood is the combination of several factors. First, they have a genuine technological advantage—the Portal system is a second-generation phased-array design that they've productized and manufactured at scale. Second, they have a clear go-to-market strategy, splitting focus between government and commercial customers. Third, they have extraordinary validation: the Space Force's $49.8 million contract is essentially the US military saying, "Yes, this technology works and we want it in production."

This government validation is worth more than any venture funding. It de-risks the technology in the eyes of other customers, both government and commercial.

Why the Space Force Cares About Ground Station Modernization

The US military operates thousands of satellites for communications, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance. The Space Force's Satellite Control Network manages launches, maintains operational status, and provides telemetry and tracking for these vehicles.

According to a 2023 government report, this network processes approximately 450 daily contacts with satellites. It's a critical piece of military infrastructure, and it's aging. The report specifically noted "sustainment and obsolescence issues while demands on the system are increasing."

Translate that from bureaucratic language: the legacy ground stations are breaking down, and there's too much work for them to handle.

The Space Force faced a classic problem: they could either invest billions in replacing the entire network with modernized parabolic dish systems, or they could look for breakthrough technologies that fundamentally changed the game.

They chose the latter approach. Rather than just building bigger, faster versions of existing technology, they opened the door to companies exploring entirely new architectures.

Northwood began working with the Space Force in September 2024. Within months, they received a $49.8 million contract to augment the Satellite Control Network. That's not a research contract or a demonstration project—it's a production contract. The Space Force is saying, "We're confident enough in this technology that we want you to build systems and deploy them into our operational network."

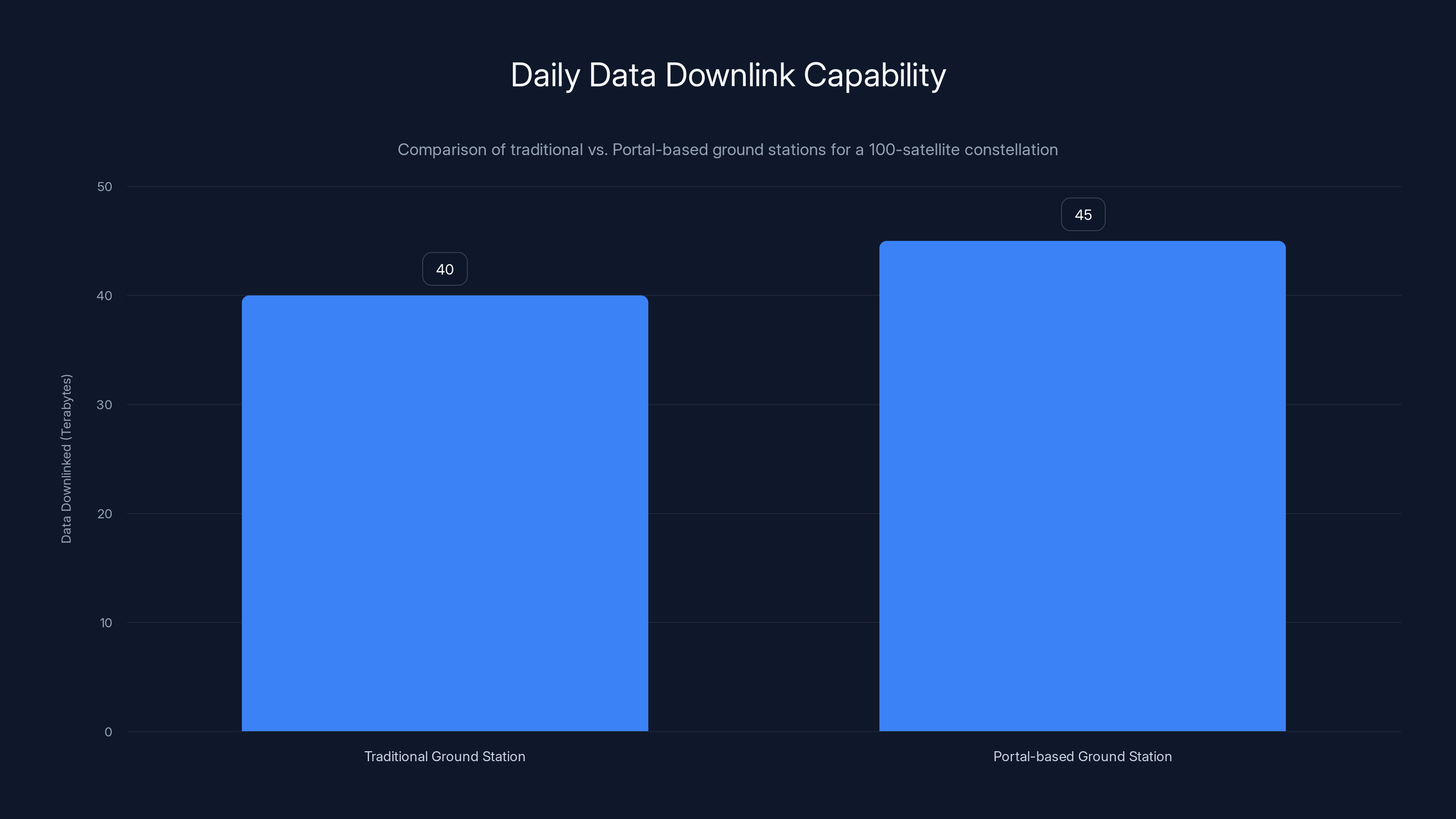

Portal-based ground stations increase daily data downlink by 5 terabytes, representing a 10% revenue boost for operators.

The Commercial Space Data Economy

The military opportunity is significant, but the commercial market is potentially even larger.

Earth observation imagery is increasingly valuable. Companies use satellite data to track crops, monitor infrastructure, detect illegal activity, and optimize operations. The imagery companies—Planet Labs, Maxar, Capella Space, and others—are all generating more data than they can economically downlink with existing ground stations.

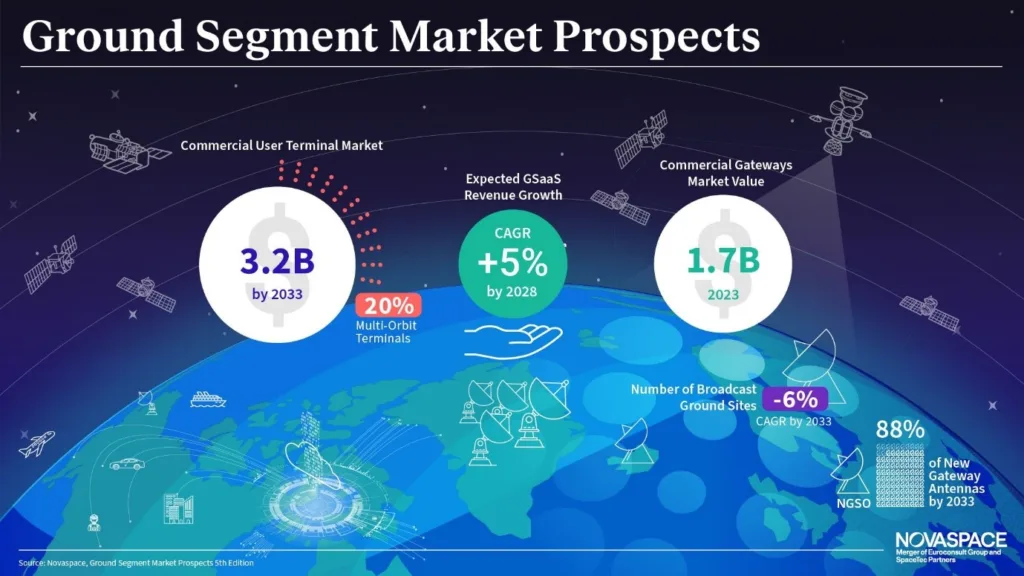

Communications megaconstellations like Starlink and Kuiper are building global networks that require extensive ground station infrastructure to connect satellites to network operations centers and backhaul gateways.

A newer and more speculative category is orbital data centers. The concept is straightforward: some compute and storage tasks are more efficiently performed in space than on Earth. Lower latency for certain applications, no terrestrial network congestion, different economics for power and cooling. Companies are exploring this seriously, but it requires enormous data throughput between orbit and Earth.

Northwood's CEO, Bridgit Mendler, emphasized this during a media roundtable: "Our overall perspective on the space industry was that volume of data was going to go up, use cases were going to go up. And that has definitely borne out, whether we're talking about communications, which has also been surging, or manufacturing or energy or compute, all of these different use cases in space, there's a lot of appetite to address them."

What she's identifying is a fundamental market dynamic: the space economy is expanding beyond traditional satellite operations into new categories that all require higher data throughput. Ground station capacity isn't a niche problem—it's central to the entire industry's growth.

Northwood's strategy explicitly targets both markets. They're building government revenue through the Space Force contract while simultaneously positioning Portal as the standard ground station for commercial mega-constellations and Earth observation operators.

Technological Advantages: Why Phased-Array Matters

Phased-array technology isn't brand new—the military has used it for radar and communications for decades. What's novel is adapting it to satellite ground stations at commercial scale.

Traditional parabolic dishes operate at frequencies like X-band (7-8 GHz) or Ka-band (32-34 GHz). Phased arrays can operate at these same frequencies, but they offer specific advantages.

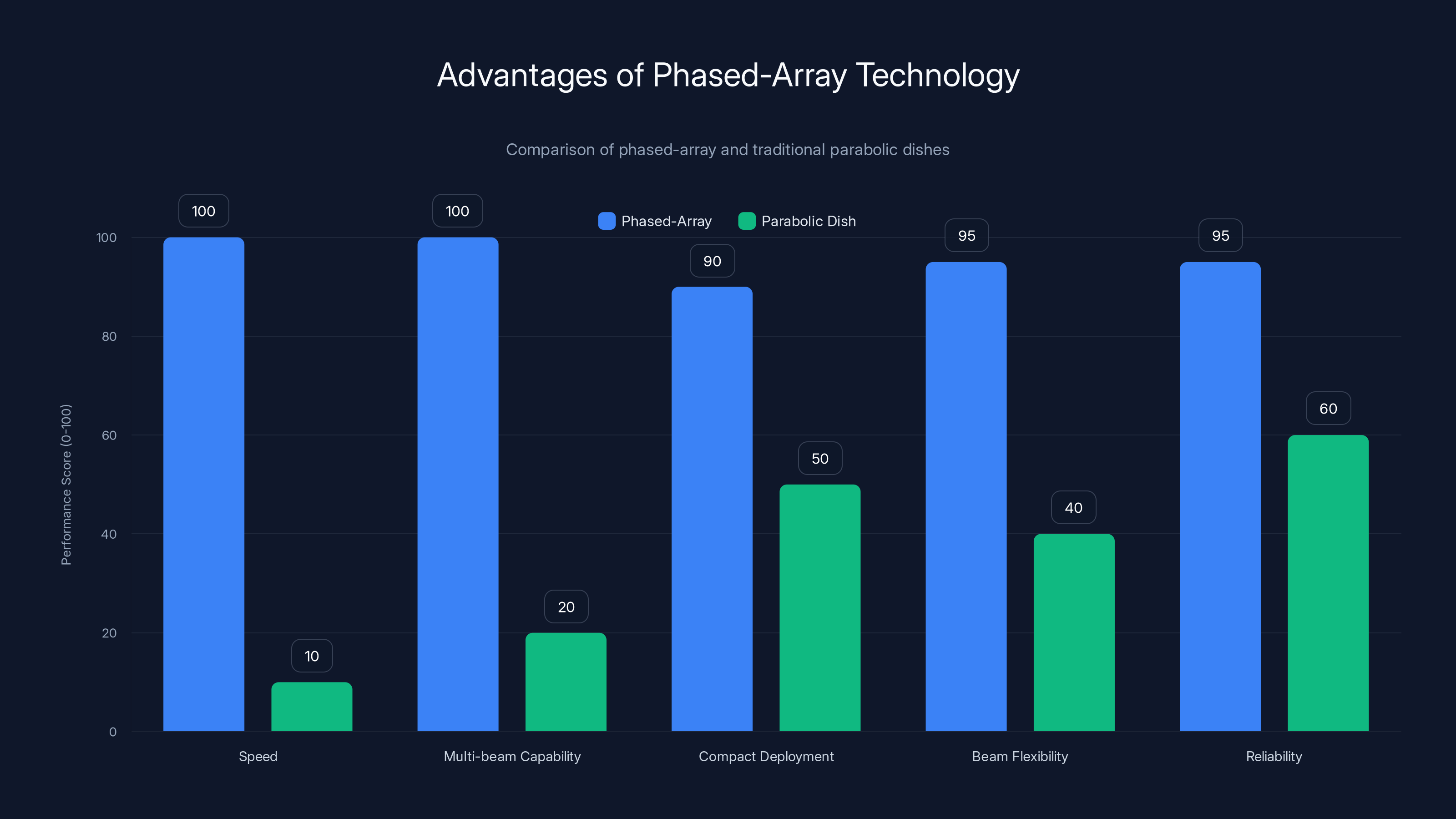

Speed: Electronic steering is three to four orders of magnitude faster than mechanical steering. A parabolic dish might take minutes to reorient. A phased array can switch targets in milliseconds. For a ground station handling dozens of satellite passes per day, this difference is enormous.

Multi-beam capability: By partitioning a large phased-array aperture into multiple smaller beams, you can track multiple satellites simultaneously. One facility can handle more satellites with a single array than a traditional dish could handle with multiple dishes.

Compact deployment: Phased arrays don't require massive mechanical structures. They're flatter, lighter, and more modular. This enables deployment at more locations, reducing the geographic gaps in coverage.

Beam flexibility: Electronic steering enables rapid beam repositioning for optimal signal reception. As satellites move across the sky, the array can compensate for changes in geometry and path loss.

Fewer moving parts: Traditional dishes have servo motors, mechanical bearings, and gearboxes. These fail. Phased arrays are mostly electronic. They're more reliable and require less maintenance.

Northwood has demonstrated that Portal arrays, measuring 8 to 15 meters in area, deliver equivalent data throughput to 7-meter parabolic dishes. For many applications, this equivalence is sufficient. For others, it's actually superior because of the speed and flexibility advantages.

The company's manufacturing capability is also significant. By demonstrating the ability to build eight arrays per month, they've proven the system can scale. Traditional satellite dishes are built in small batches, often as unique installations. Portal is being manufactured at higher volumes, which drives down per-unit cost and reduces deployment timelines.

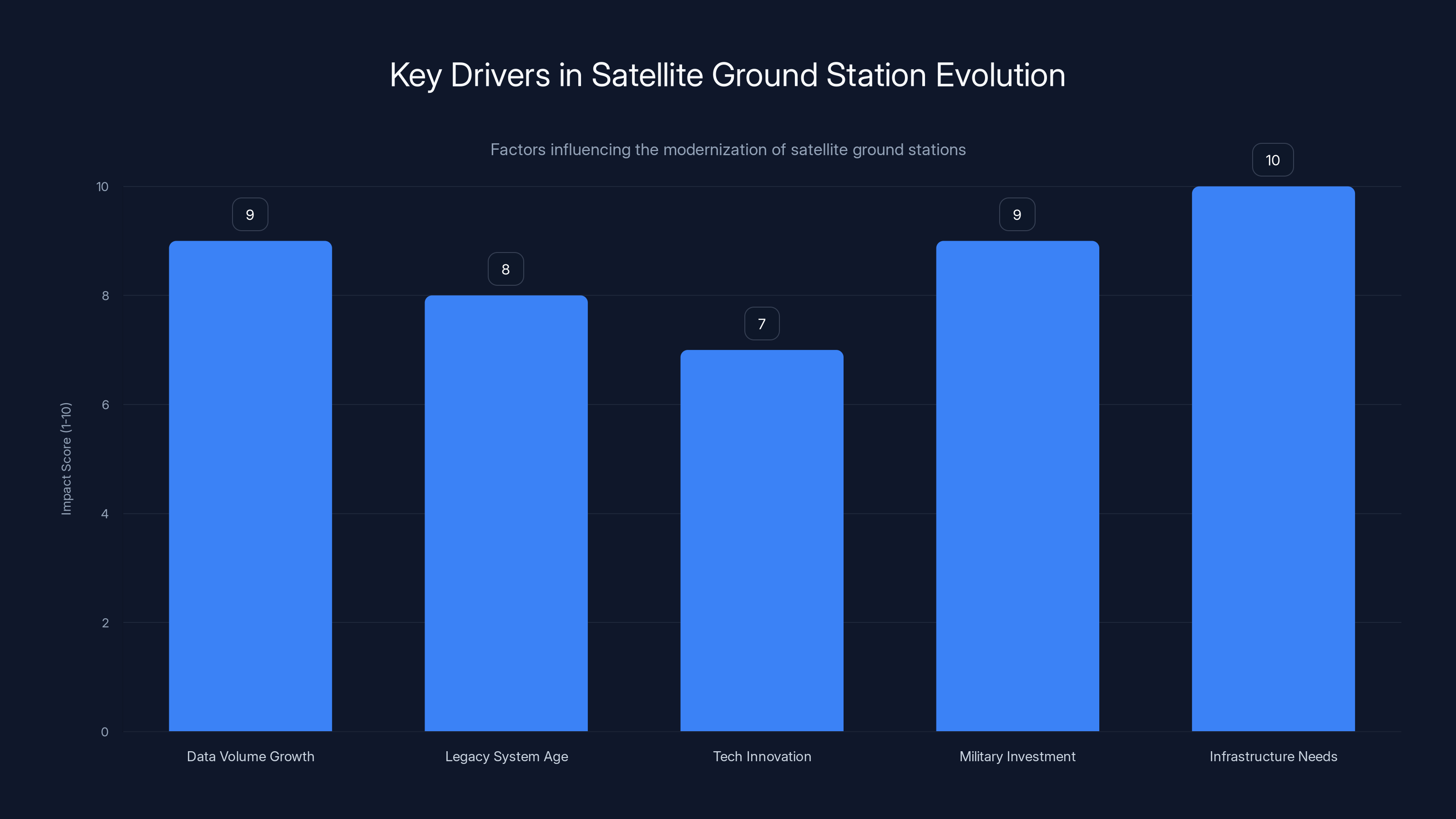

Data volume growth and infrastructure needs are the most significant drivers for modernizing satellite ground stations. Estimated data.

The Operational Deployment Strategy

Northwood's approach to ground station deployment differs fundamentally from traditional models.

Historical deployments involved selecting a few premium locations—often on government property or in strategic geographic areas—and building expensive, purpose-built facilities with multiple large dishes. Once built, these were relatively static. Adding more capacity meant either investing in another new facility or adding more dishes to existing ones.

Northwood's strategy emphasizes rapid deployment of Portal arrays across many more locations. The modular nature of phased-array technology and the smaller physical footprint enable this distribution.

By January 2025, the company had deployed operational systems on two continents. This is important because satellite coverage isn't uniform. A satellite in low Earth orbit might pass over the Pacific Ocean once per orbit, but rarely over land. Having ground stations distributed globally maximizes the number of passes where data can be downloaded.

Coverage density is a key metric. If you have one ground station, a satellite gets maybe one or two passes per day over that location. If you have ten ground stations distributed globally, the same satellite might have ten passes per day where it can downlink data. This dramatically increases the effective capacity of a constellation.

Northwood's business model assumes they'll deploy dozens of Portal arrays, not just a handful. Some will be on Northwood property, others at customer locations or government facilities. The distributed network becomes more valuable than any single facility.

The company's ability to manufacture eight arrays monthly is specifically designed to support this expansion. They're not trying to build perfect facilities at scale—they're manufacturing deployable units that can be installed relatively quickly and relatively inexpensively compared to traditional ground stations.

Financial Dynamics and Funding Rounds

Northwood's funding trajectory reveals market confidence in the business.

The company emerged from stealth in February 2024—essentially less than a year before the Series B announcement. Starting as stealth meant they were already working on Portal with some funding, but they weren't publicly visible. By the time they announced themselves publicly, they had a second-generation system and customer interest.

In April 2025, they announced a Series A round (the article references this as their "last fundraise"). Several months later, in January 2025, they announced the $100 million Series B.

A $100 million Series B is substantial. It positions Northwood in the upper tier of space infrastructure startups. For context, that's the kind of funding round typically reserved for companies that have proven product-market fit and have a clear path to scale.

Combined with the

The funding sources matter too. VCs investing at this scale are betting on several things: that the space data problem is real and urgent, that phased-array technology is the right solution, that Northwood's team can execute, and that there's a large addressable market for ground station services.

Space infrastructure funding has been robust in recent years, but it's also selective. Money flows to companies addressing genuine bottlenecks with defensible solutions. Northwood is checking these boxes.

Phased-array technology significantly outperforms traditional parabolic dishes in speed, multi-beam capability, compact deployment, beam flexibility, and reliability. Estimated data based on described advantages.

Competitive Dynamics and Market Entry

The ground station market is competitive but not crowded. Unlike fields like satellite communications where dozens of companies are pursuing similar approaches, ground station technology is dominated by a smaller set of players.

One reason is that ground stations are infrastructure. They're expensive to develop, require specialized expertise, and have long sales cycles. You can't just code your way to a ground station business like you might with a software platform.

Another reason is that ground stations are less visible than satellites. Most media attention flows to the orbital vehicles. Ground stations are the unglamorous necessary infrastructure.

This invisibility actually benefits entrants like Northwood. While competitors might still be in early-stage development or fighting for market share with incremental improvements to existing approaches, Northwood has secured major government validation and commercial interest.

The question is whether other companies will develop competing phased-array systems. Technologically, this is certainly possible. Large aerospace contractors like Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, and Raytheon have the expertise to build phased-array ground stations. But moving large organizations into new markets is slow. They're comfortable with existing approaches and existing customer relationships.

Smaller companies might pursue phased-array approaches, but they'd be entering the market years behind Northwood, without the manufacturing experience, without the government validation, without the established customer relationships.

This is why first-mover advantage is significant in infrastructure markets. Northwood's lead isn't just about the technology—it's about operational experience, manufacturing scale, and established customers.

Addressing Scalability and Future Capacity

The obvious question: can Portal scale to meet the future demand?

Griffin Cleverly, Northwood's CTO, addressed this during media communications. Across initial Portal sites, each array can handle communication with a few dozen spacecraft. In 2027 and beyond, with increased manufacturing scale, the network could handle hundreds of satellites.

This progression makes sense. Early deployments will focus on high-priority customers and locations. As manufacturing matures and costs decline, expansion accelerates.

The underlying question is whether phased-array technology can scale to handle the exponentially growing number of satellites. This depends on several factors:

Frequency availability: Radio spectrum is finite. Operating at higher frequencies enables higher data rates but also higher path loss over distance. Ground stations will need to operate across multiple frequency bands to maximize utilization.

Manufacturing efficiency: As production volume increases, per-unit manufacturing cost should decline. Northwood's demonstrated ability to build eight arrays monthly is a start, but reaching production rates of tens or hundreds per month will be necessary to deploy the network the company envisions.

Power and cooling: Large phased-array antennas consuming significant RF power require robust electrical infrastructure and cooling systems. Deploying arrays in remote locations requires substantial site preparation.

Real estate: Ground station locations are geographically constrained. You need clear sky access, proximity to network infrastructure, and minimal RF interference. Available locations are limited. As demand grows, finding new sites becomes harder.

Northwood's strategy of distributed deployment partially addresses this. Rather than relying on a few premium locations, they're building a network of many smaller facilities. This spreads the geographic load and improves overall coverage.

But there are absolute limits. You can't deploy ground stations underwater or in the middle of oceans. Some regions have better orbital geometry than others. Ultimately, ground station capacity will be constrained by the finite set of suitable locations worldwide.

This creates an interesting dynamic: as the satellite industry continues to grow, ground station infrastructure becomes increasingly valuable. Companies that control access to key locations gain negotiating leverage with satellite operators.

Data Pipeline Economics

Understanding ground station value requires understanding the economics of space data pipelines.

For an Earth observation company, the value chain looks roughly like this: launch satellites (huge capital cost), operate them in orbit (ongoing operational cost), collect imagery (capital cost for ground stations), process data (compute cost), sell results to customers (revenue).

Ground station cost is a meaningful portion of this pipeline. Not the largest (launch vehicles dominate), but significant. And critically, it's a bottleneck. If you can't downlink your imagery, it's worthless.

Northwood's value proposition is efficiency: Portal achieves equivalent capability to traditional ground stations at lower total cost of ownership. Lower capital cost (modular, smaller), faster deployment (fewer moving parts, simpler installation), lower operational cost (less maintenance, more reliable), and better throughput (faster switching, multi-satellite capability).

How much is this worth? Consider a constellation operator with 100 satellites generating 50 terabytes per day total. Traditional ground stations might be able to downlink 40 terabytes daily, leaving 10 terabytes stranded until the next day's passes.

If upgraded to Portal-based infrastructure, the same operator might downlink 45 terabytes daily. That additional 5 terabytes per day represents roughly 10% additional revenue if the data would otherwise be sold.

For a company with hundreds of millions in annual revenue, 10% is substantial.

Multiply this across dozens of constellation operators, communications companies, and other space customers, and the addressable market for ground station services becomes quite large.

Regulatory Landscape and Spectrum Constraints

Ground stations operate within regulatory frameworks that often constrain their capabilities.

In the United States, the FCC regulates terrestrial transmitters and receivers. Satellite ground stations require specific licenses. International coordination is required for certain frequency bands to prevent interference across borders.

The ITU (International Telecommunications Union) manages global spectrum allocation. Satellite services have specific allocations, but these are shared with other users. Ground stations must operate within designated frequency bands and power levels.

For Northwood and other ground station operators, this creates both opportunities and constraints. The constraint is obvious: you're limited in the frequencies and power levels you can use. The opportunity is less obvious but real: properly engineered systems can provide better spectrum efficiency than legacy equipment.

A modern phased-array system operating with advanced signal processing can extract more useful data from a given RF signal than older analog equipment. This translates to better effective capacity within existing spectrum allocations.

As spectrum becomes increasingly congested, this efficiency becomes more valuable. Regulatory agencies preferentially award licenses to operators who can demonstrate efficient spectrum use.

Northwood's approach to spectrum efficiency—multiple simultaneous beams, rapid beam steering, advanced signal processing—aligns with regulatory trends favoring more efficient technologies.

The Vertical Integration Strategy

Bridgit Mendler emphasized Northwood's "vertically integrated ground network" approach.

What does this mean? Rather than being a component supplier (building antennas that others integrate into systems) or a service provider (operating a single ground station facility), Northwood is building end-to-end ground infrastructure.

They design Portal, they manufacture it, they deploy it, and they operate the resulting network. This gives them control over the entire stack.

Vertical integration offers several advantages. First, it ensures quality control. Rather than relying on third parties to integrate their antenna into systems, Northwood ensures it's done correctly. Second, it creates switching costs. Customers become dependent on Northwood's systems and operational expertise, not just the hardware.

Third, it enables rapid iteration. If Northwood identifies a software improvement that would help ground stations operate better, they can push it out to their entire network. Customers don't need to approve upgrades or coordinate with third parties.

Fourth, it creates recurring revenue. Component suppliers get one-time sales. Service operators get ongoing revenue. Northwood's model includes both, making it more stable.

The trade-off is complexity. Vertical integration means Northwood needs expertise across hardware design, manufacturing, software systems, RF engineering, and operations. They can't just focus on one thing.

Northwood is betting that the benefits of vertical integration outweigh the complexity costs. Early signals suggest they're right—the Space Force's willingness to fund their expansion suggests confidence in this approach.

Future Roadmap and Technology Evolution

Northwood's near-term plans involve manufacturing scale-up and deployment expansion. The company has demonstrated the ability to build eight Portal arrays monthly. The Series B funding will support expansion to significantly higher production rates.

Geographic deployment will accelerate. The company expects to have systems operational on multiple continents, with a focus on locations that provide optimal coverage for commercial and government customers.

Northwood is also exploring next-generation capabilities. Phased-array technology enables various enhancements: wider frequency bands, higher power levels, more simultaneous beams, integrated processing capabilities.

One interesting direction is integration with artificial intelligence and machine learning. Ground stations generate enormous amounts of data about signal characteristics, weather conditions, orbital mechanics, and system performance. Machine learning could optimize scheduling (when to downlink from which satellites), predict maintenance needs, and improve signal processing algorithms.

Another direction is open architecture standards. The satellite industry is moving toward standardized interfaces and APIs. Northwood could become an infrastructure standard that customers integrate into their operations without deep technical involvement.

Longer-term, the question is whether phased-array technology will eventually be augmented or replaced by other approaches. Free-space optical communication, for example, offers dramatically higher bandwidth than RF. Integrating optical and RF capabilities into a single ground facility would be complex but potentially valuable.

Northwood is positioning itself as the leader in RF ground station infrastructure for the next decade at minimum, with options to expand into complementary technologies.

Broader Implications for the Space Industry

Northwood's success would have ripple effects throughout the space economy.

First, it would reduce a critical constraint on satellite constellation growth. Companies currently limited by ground station capacity could expand their operations. This accelerates investment in mega-constellations and specialized imaging systems.

Second, it would lower the capital cost of entering the satellite business. Traditional ground stations are expensive to deploy. Modular, deployable Portal arrays reduce this barrier, potentially enabling more startups to build satellite systems.

Third, it would validate phased-array technology as the standard for modern ground stations. Other companies would likely pivot to similar approaches, creating competitive pressure and driving further innovation.

Fourth, it demonstrates the continuing importance of infrastructure in space commerce. Satellites get the headlines, but infrastructure—ground stations, launch facilities, tracking networks—is equally important. As the space economy matures, infrastructure companies may outperform hardware manufacturers in terms of growth and profitability.

Finally, it highlights an important strategic trend: the US government is outsourcing infrastructure development to private companies. Rather than building everything themselves, agencies like the Space Force are funding private companies to develop capabilities, then integrating those capabilities into military operations. This approach is faster and often cheaper than traditional government development.

Investment Thesis and Market Opportunity

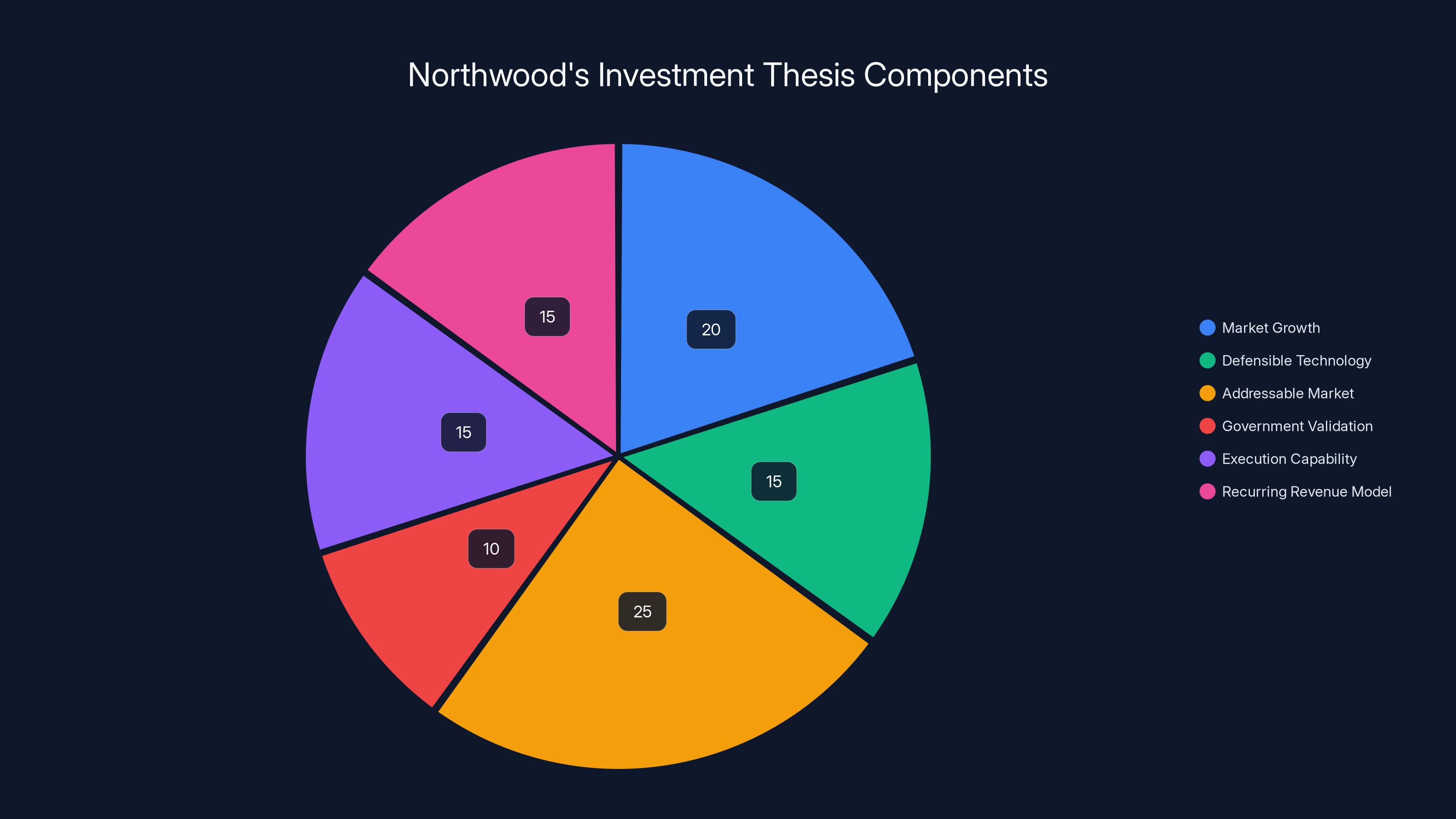

Why did investors commit $100 million to Northwood's Series B?

The thesis has several components.

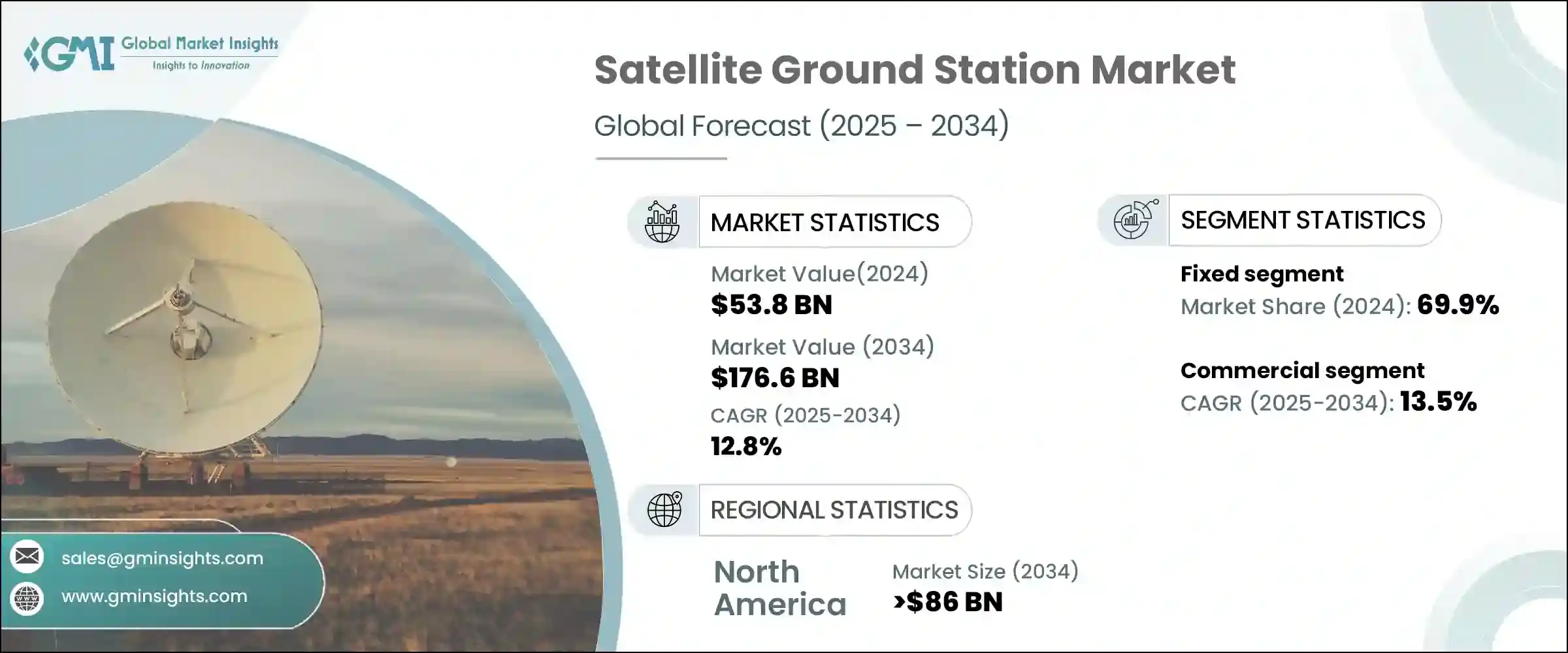

Market growth: Satellite data volume is growing exponentially. Ground station capacity is the constraint limiting this growth. Companies will pay to remove this constraint.

Defensible technology: Phased-array design gives Northwood a genuine technical moat. Competitors can copy individual features, but replicating the entire system takes years.

Addressable market: The global ground station market is measured in billions of dollars annually. Even capturing a small percentage of this represents substantial enterprise value.

Government validation: The Space Force contract derisk the investment. It proves the technology works and creates a reference customer for commercial sales.

Execution capability: Northwood's team includes experienced aerospace and RF engineers who have shipped products at scale. This isn't first-time entrepreneurs—it's people who know how to build infrastructure systems.

Recurring revenue model: The company plans to operate ground stations as a service, not just sell hardware. This creates ongoing revenue streams and higher valuation multiples.

Combining these factors, investors are betting that Northwood will become the dominant provider of modern ground station infrastructure globally. If they execute, the company could eventually achieve unicorn valuation (currently undisclosed, but likely in the multi-billion range based on funding and Space Force contract size).

The risk is execution. Ground stations are complex systems. Deploying them globally requires navigating regulatory requirements, real estate challenges, and operational complexity. Any major setback could slow the company's progress.

But the market fundamentals—growing satellite data volume and insufficient ground capacity—are undeniable. Even if Northwood doesn't capture 100% of the opportunity, there's enough market for them to build a substantial business.

Conclusion: The Unsexy Infrastructure Play That Actually Matters

Ground stations aren't exciting. They don't appear in sci-fi movies. They're not what people think about when they imagine the space economy.

But they might be the most important infrastructure layer shaping the next decade of space development.

The satellite industry has solved the hard part: getting objects into orbit and keeping them functional. What nobody adequately solved is efficiently moving data between space and Earth at the scale the industry now demands.

Northwood Space's Portal system and phased-array approach address this directly. The company's

What happens next depends on execution. Can Northwood scale manufacturing to thousands of units annually? Can they deploy systems globally while managing the operational complexity? Can they maintain their technical lead as competitors inevitably respond?

These questions will determine whether Northwood becomes the dominant player in modern ground station infrastructure, or whether they're simply the first mover in a category that eventually commoditizes.

But regardless of Northwood's ultimate trajectory, the company's emergence and funding signal something important: infrastructure in space is becoming increasingly valuable. The space economy isn't just about launching satellites—it's about the entire ecosystem that makes those satellites useful.

Investors betting on space should pay attention to unglamorous infrastructure plays. They might not generate headlines, but they often generate returns.

FAQ

What is a ground station in satellite operations?

A ground station is a facility with antennas and radio equipment that sends commands to satellites and receives data from them. Ground stations are essential infrastructure that enables communication between Earth and orbiting spacecraft. Without functioning ground stations, satellites would be unable to transmit data, receive commands, or maintain operational contact with mission control.

Why is there a bottleneck in ground station capacity?

Satellites are generating exponentially more data than ground stations can handle. Modern imaging satellites produce 50+ terabytes daily, but many ground stations were built 10+ years ago and lack the capacity to downlink all this data in the narrow windows when satellites pass overhead. The number of satellites in orbit is also increasing rapidly—Starlink alone has over 6,000 operational spacecraft—but ground station infrastructure hasn't kept pace with this growth.

How do phased-array antennas differ from traditional parabolic dish antennas?

Phased-array antennas steer their beams electronically by adjusting signal timing across multiple antenna elements, enabling instant switching between targets and simultaneous multi-satellite tracking. Traditional parabolic dishes mechanically point at targets and can only communicate with one satellite at a time. Phased-array systems are faster, more reliable, smaller, and more flexible—but they're also more complex to design and manufacture. Northwood Space's Portal system uses phased-array technology to achieve equivalent data throughput to larger traditional dishes.

What is the US Space Force's role in ground station development?

The Space Force operates the Satellite Control Network, which manages communications with thousands of military and government satellites. The network was showing obsolescence and capacity issues, so the Space Force sought modern solutions. Rather than developing entirely new systems internally, they contracted with private companies like Northwood Space to build next-generation ground stations. The Space Force's $49.8 million contract validates Northwood's technology and accelerates deployment of modern infrastructure.

How much data do satellites actually generate?

Modern satellites generate massive data volumes. Earth observation satellites can produce 50+ terabytes per day, communications satellites handle petabits of data through their transponders, and scientific satellites stream continuous telemetry. As satellite constellations grow and sensor capabilities improve, total orbital data generation will continue increasing exponentially. This data is valuable—it powers Earth observation services, enables global communications, supports climate monitoring—but only if it can be efficiently downlinked to Earth.

What is the commercial market opportunity for ground station companies?

The global ground station market represents billions of dollars in annual revenue from Earth observation companies, communications operators, and government customers. Companies like Planet Labs and Capella Space operate mega-constellations that require extensive ground infrastructure. Communications companies building global networks like Starlink and Kuiper need distributed ground stations. Even emerging use cases like orbital data centers would require enormous ground station capacity. The addressable market for modern ground station infrastructure is substantial and growing rapidly.

Can phased-array technology scale to handle future satellite volumes?

Phased-array technology can scale, but with constraints. Manufacturing efficiency will improve as production volumes increase—Northwood is building eight arrays monthly with plans to scale much higher. Distributed deployment across multiple continents improves overall coverage. However, there are geographic limits to ground station placement and spectrum constraints on radio operation. Eventually, ground station capacity may become a constraint again, but modern technology can support significantly higher satellite volumes than legacy systems.

What competitive threats does Northwood Space face?

Large aerospace contractors like Lockheed Martin and Northrop Grumman could develop competing phased-array systems, though moving large organizations into new markets is slow. Other startups might pursue similar approaches, but they'd enter years behind Northwood. The main risk is technological disruption—free-space optical communications or other novel approaches could eventually supplement or replace RF ground stations. For the next 5-10 years, Northwood's combination of technology, manufacturing experience, and customer relationships provides significant competitive advantage.

How do regulatory requirements affect ground station deployment?

Ground stations must operate within FCC regulations in the United States and coordinate internationally through the ITU to prevent RF interference across borders. Specific frequency bands are allocated for satellite services, and ground stations must operate within designated frequency ranges and power levels. Modern systems like Northwood's Portal can achieve better spectrum efficiency than legacy equipment, which aligns with regulatory trends favoring more efficient technologies. Navigating these requirements adds complexity but also creates competitive advantages for companies that do it well.

What does "vertically integrated ground network" mean in Northwood's context?

Rather than just selling antennas as components, Northwood designs Portal systems, manufactures them, deploys them globally, and operates the resulting ground network. This vertical integration ensures quality control throughout the system, creates customer switching costs through operational dependency, enables rapid software improvements across the entire network, and generates recurring revenue from operations. It's a more complex business model than component sales alone, but it creates stronger customer relationships and more stable revenue streams.

What is the time horizon for ground station infrastructure to become saturated?

Given current rates of satellite launches and data growth, ground station capacity will likely remain constrained through at least 2030. Northwood's technology can support significantly higher volumes than existing infrastructure, suggesting they have a 5-7 year window before competitors catch up or new technological approaches emerge. However, the fundamental market driver—exponentially growing satellite data volumes—will likely persist for much longer, creating ongoing demand for infrastructure improvements throughout the 2030s and beyond.

Key Takeaways

- Satellite data volumes are growing exponentially while ground station capacity has stagnated, creating a critical infrastructure bottleneck limiting space economy growth

- Phased-array antenna technology enables electronic beam steering instead of mechanical movement, allowing instant multi-satellite tracking and dramatically faster switching speeds

- Northwood Space's 49.8M Space Force contract represent major validation that modern ground station solutions are ready for production deployment

- The ground station market represents a multi-billion dollar infrastructure opportunity as mega-constellations and data-intensive space applications demand higher capacity

- Vertically integrated ground networks—where companies design, manufacture, deploy and operate systems end-to-end—create stronger customer relationships and recurring revenue streams

Related Articles

- Northwood Space Lands 50M Space Force Contract [2026]

- Blue Origin's New Glenn Third Launch: What's Really Happening [2026]

- Blue Origin's TeraWave Megaconstellation: The 6Tbps Satellite Internet Game Changer [2025]

- Haven-1 Commercial Space Station: Assembly, Launch Timeline & Future Impact 2027

- NASA's Commercial Space Station Crisis: Senate Demands Timeline [2025]

- SpaceX's 7,500 New Starlink Satellites: What It Means [2025]

![Satellite Ground Stations: The Bottleneck Reshaping Space Infrastructure [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/satellite-ground-stations-the-bottleneck-reshaping-space-inf/image-1-1769524777331.jpg)