Introduction: When a Second Billionaire's Company Enters the Space Internet Race

Jeff Bezos owns two major space companies. Most people know about Blue Origin—the rocket manufacturer and space tourism outfit. But fewer realize that Amazon, his cloud computing behemoth, has been quietly developing its own satellite internet constellation called Amazon Leo for over a decade. According to Nearshore Americas, Amazon is investing $10 billion to compete with Starlink.

Now, in a move that surprised the entire aerospace industry, Blue Origin just announced it's building a third major satellite network called Tera Wave. And this one isn't going after Starlink's consumer broadband market. Instead, it's targeting something far more lucrative: enterprise data centers, government networks, and mission-critical operations that need extreme reliability.

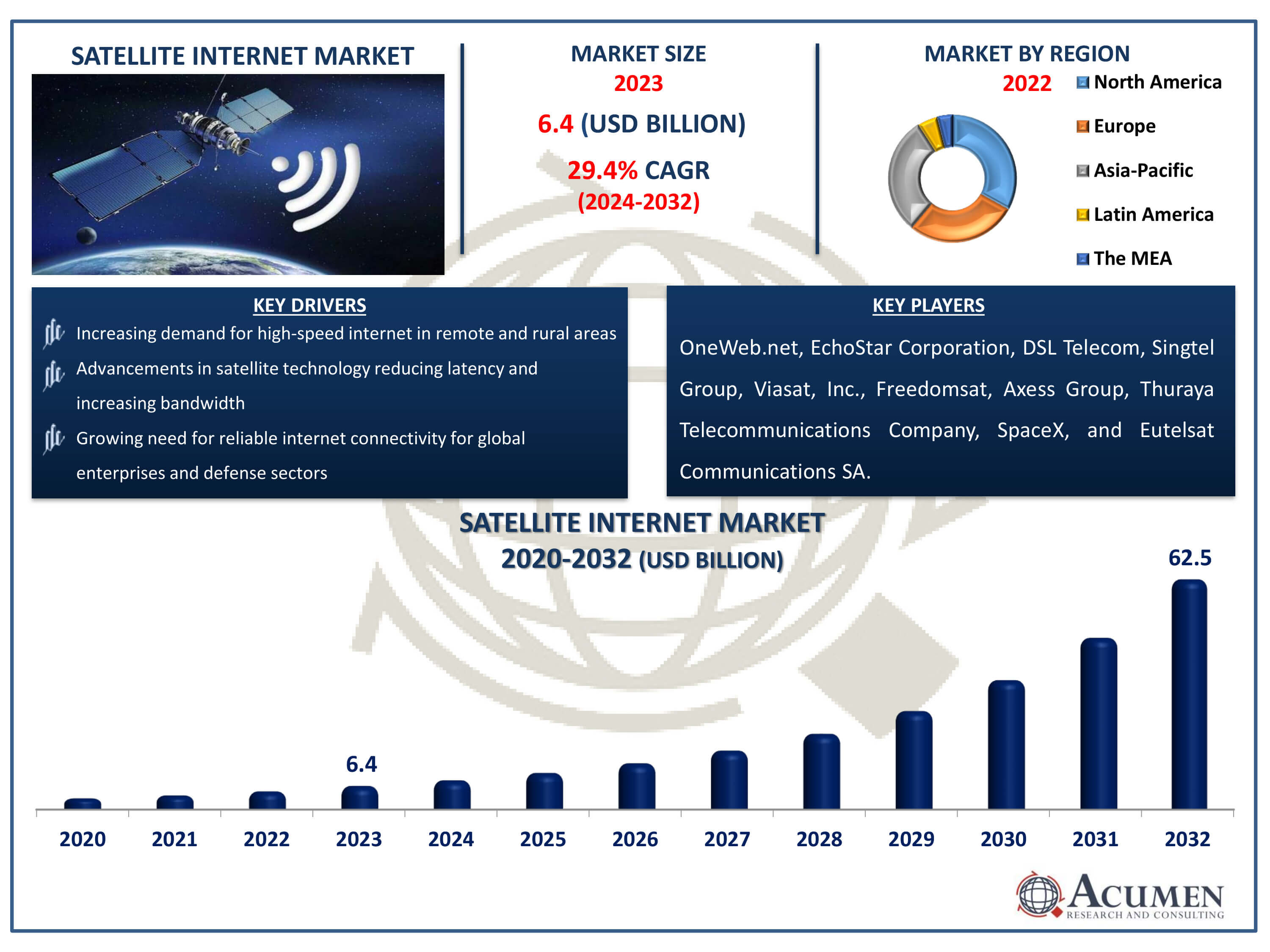

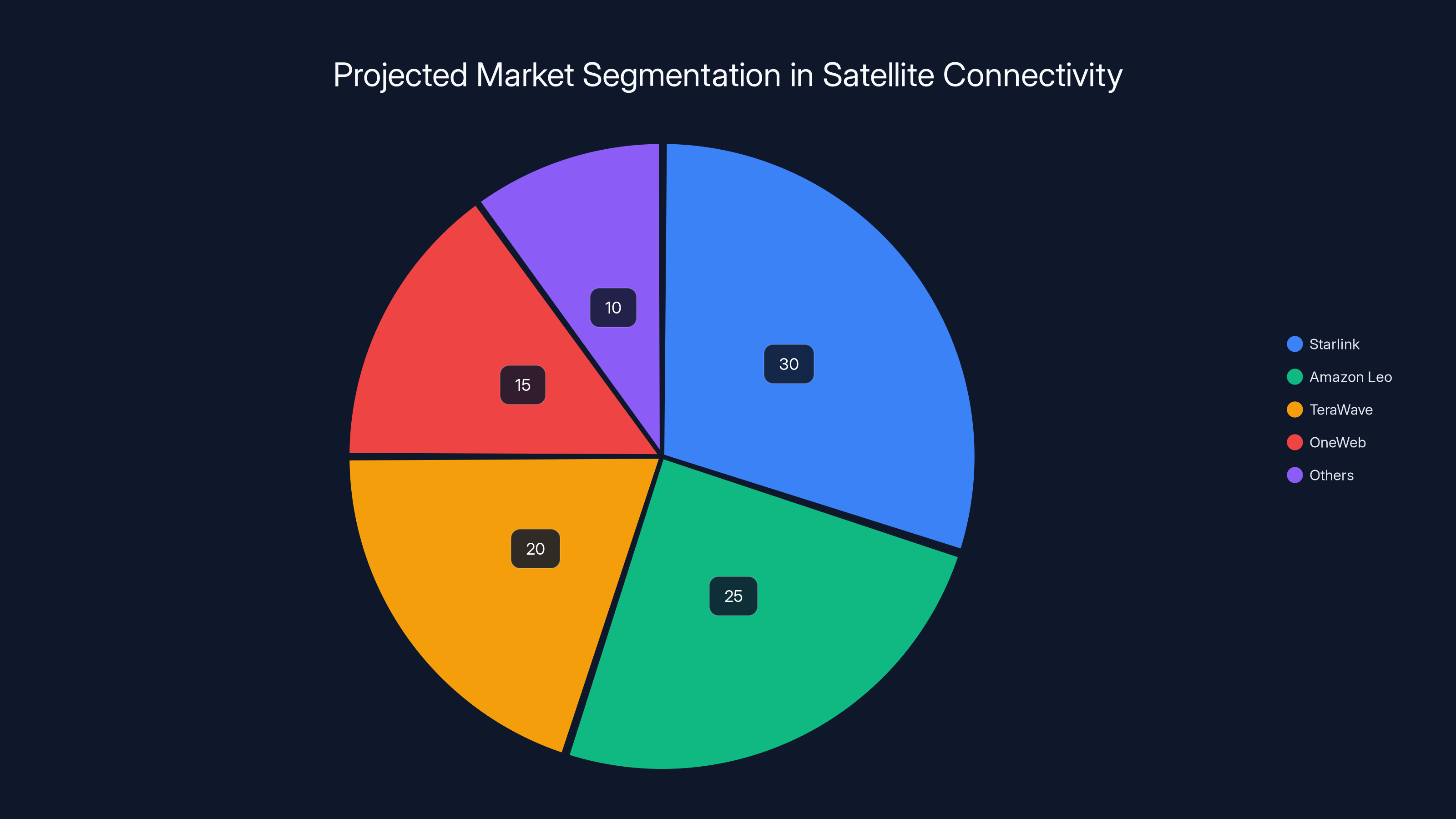

This announcement matters because it signals a fundamental shift in how the space industry views satellite connectivity. The race for global broadband has been the narrative for years. Starlink dominates the consumer market with millions of subscribers. Amazon Leo waits in the wings, promising to compete directly with Starlink. But behind the scenes, a different battle is brewing—one focused on connecting data centers, powering AI operations, and replacing traditional fiber links between remote facilities.

Tera Wave's headline spec makes your head spin: up to 6 terabits per second of total capacity. To put that in perspective, the fastest single fiber optic cable currently connecting two continents manages about 400 terabits per second. Tera Wave, with its 5,408 optically interconnected satellites, would offer a distributed, redundant alternative to traditional undersea cables. For enterprise customers, that's not just faster—it's fundamentally different. It means backup connectivity. It means no single point of failure. It means the ability to reroute traffic around problems in real time.

But here's where it gets complicated. Blue Origin is already stretched thin. The company is developing the New Glenn heavy-lift rocket, multiple lunar landers, a space station module, orbital refueling spacecraft, and now this megaconstellation. Adding Tera Wave to that roadmap raises a critical question: can Blue Origin actually execute on all of this, or is the company taking on too much?

Let's dig into what Tera Wave actually is, why Blue Origin is building it, what it means for the satellite internet landscape, and whether this ambitious plan can succeed given the company's current constraints.

Understanding Tera Wave: The Technical Architecture

Tera Wave isn't just another satellite internet constellation. The architecture reveals a fundamentally different approach compared to Starlink and Amazon Leo.

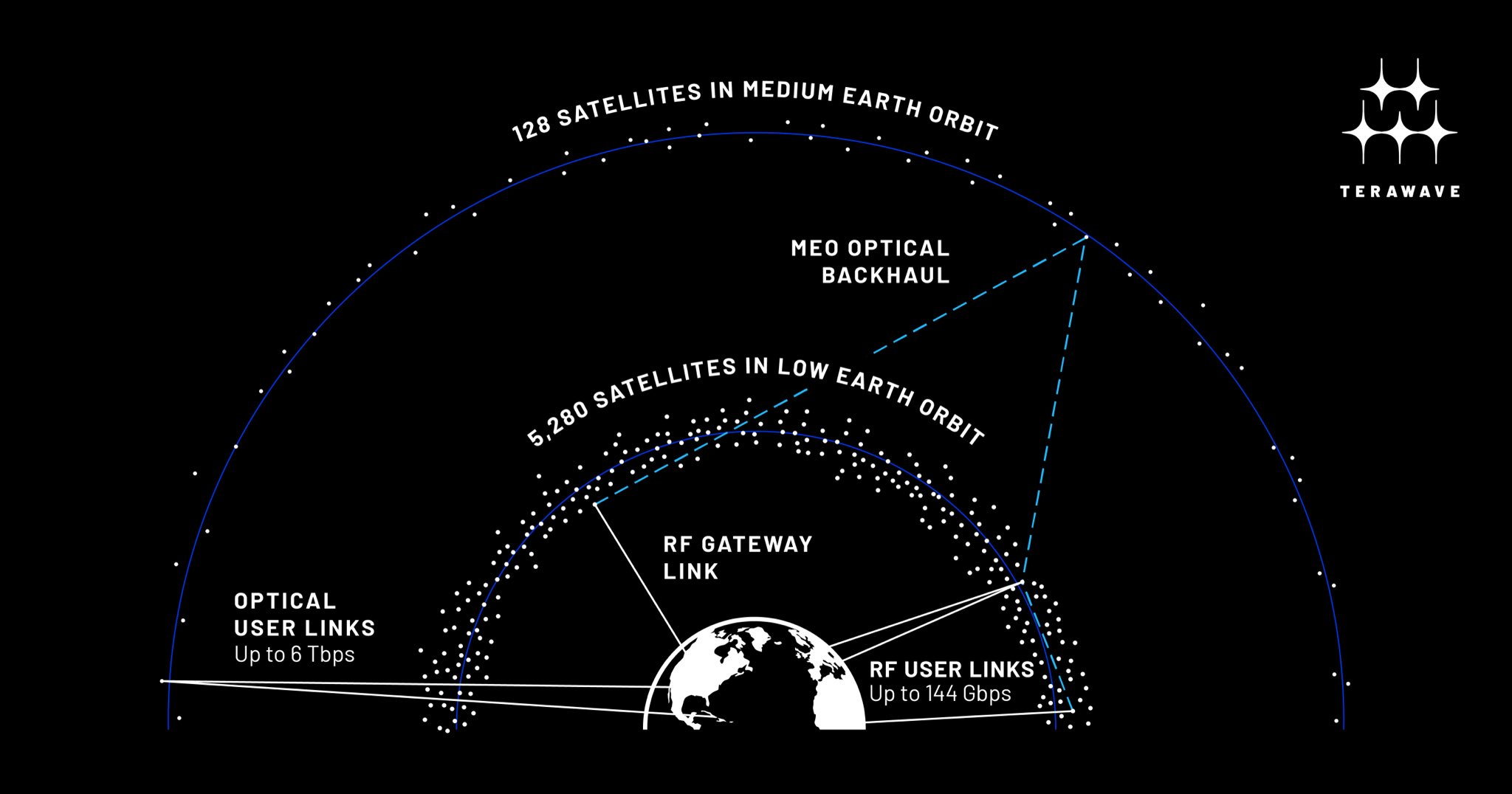

The constellation consists of 5,408 satellites split between two orbital shells. The majority sit in low-Earth orbit at altitudes around 340 to 500 kilometers. A smaller portion operates in medium-Earth orbit at much higher altitudes. This two-shell design isn't arbitrary—it's a deliberate engineering choice.

The low-Earth orbit satellites handle traditional radio frequency communications. Think of these as the access layer. Ground stations and user terminals communicate with these satellites using standard radio spectrum. Each can deliver up to 144 gigabits per second of throughput. That's actually quite impressive for radio-based systems, but it's the secondary innovation that makes Tera Wave different.

The medium-Earth orbit satellites use optical inter-satellite links—essentially laser connections between spacecraft. These don't suffer the same atmospheric interference as radio signals. They can achieve much higher data rates and lower latencies. The optical backbone creates a resilient mesh network that allows data to be routed intelligently across hundreds of satellites simultaneously.

Here's the key insight: traditional constellations like Starlink optimize for consumer latency and throughput. Tera Wave optimizes for redundancy and massive aggregate capacity. If a radio link fails, the optical network can instantly reroute traffic. If one satellite goes down, traffic bypasses it through multiple alternate paths. For data centers handling trillions of dollars in transactions, that reliability justifies the investment.

The total architecture can deliver up to 6 terabits per second when aggregating across the entire constellation. That's not per-satellite or per-gateway—it's the total network capacity. For comparison, Starlink's entire network delivers roughly similar total throughput, but distributed across different use cases and serving millions of consumer customers. Tera Wave concentrates that capacity on tens of thousands of premium enterprise customers.

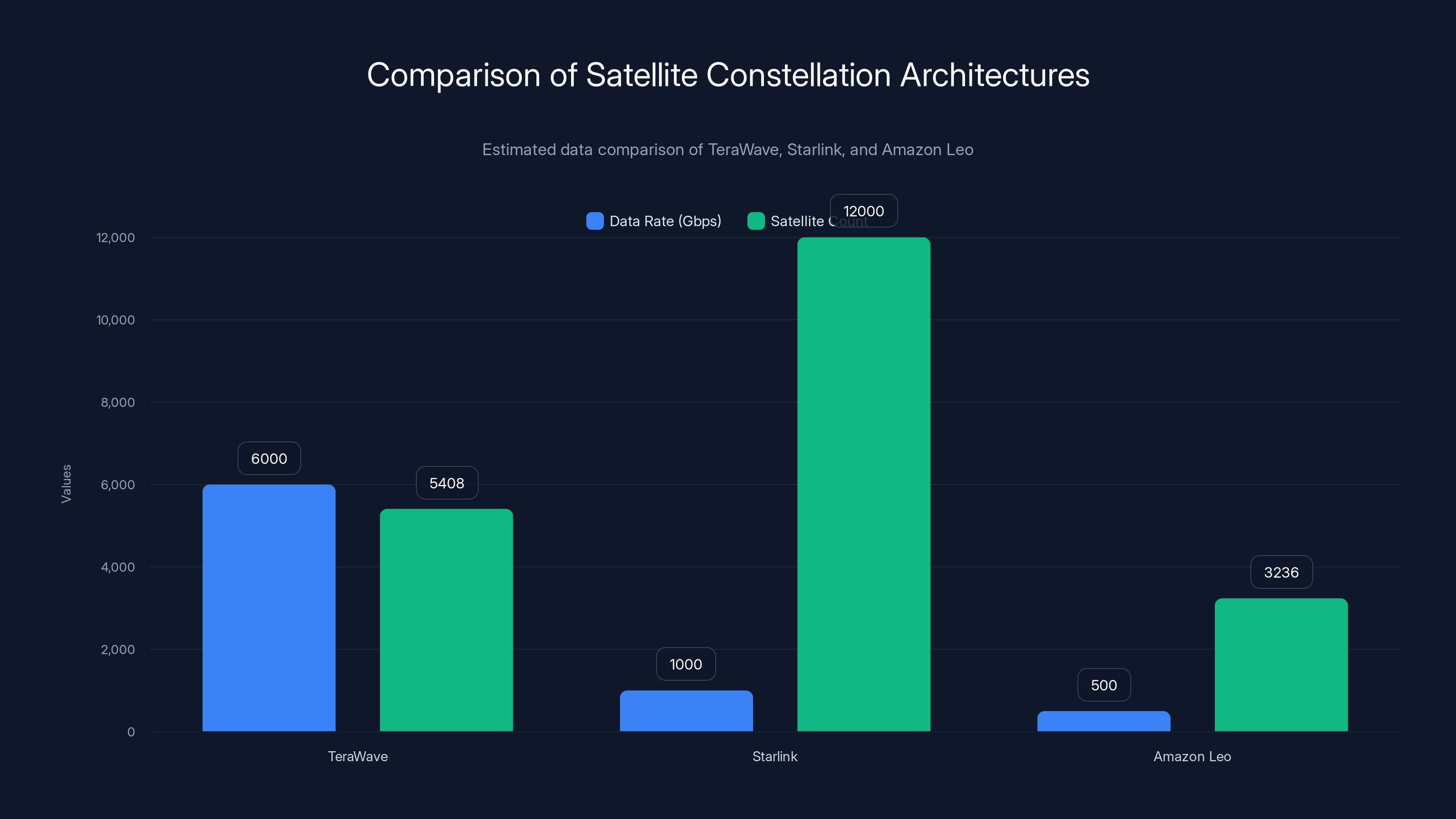

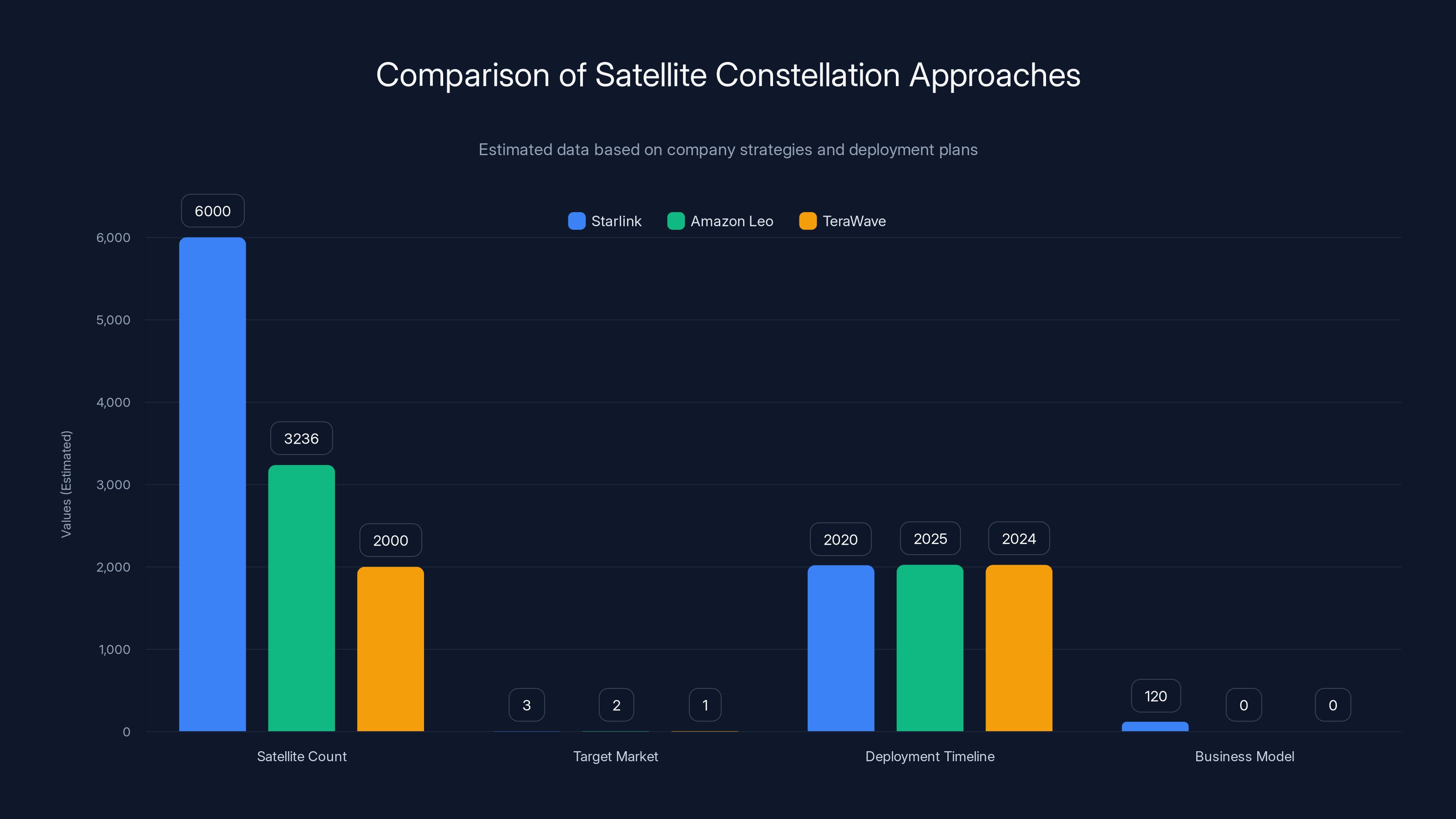

TeraWave offers significantly higher data rates with fewer satellites compared to Starlink and Amazon Leo, highlighting its focus on enterprise and government reliability. (Estimated data)

Why Blue Origin Is Targeting Enterprise Markets, Not Consumers

This decision reveals sophisticated business thinking from Dave Limp, Blue Origin's CEO.

Starlink serves consumers. Amazon Leo will serve consumers. Both companies make money from monthly subscription fees to individual users, businesses, and telecommunications partners. But the economics are brutal. Consumer broadband is competitive. Margins are thin. You need millions of subscribers to make the unit economics work. Space X probably has millions of Starlink subscribers now, and the company still operates at thin margins.

Enterprise customers work differently. A single data center customer might represent

Furthermore, enterprise customers have different requirements that actually favor a specialized constellation. A hedge fund's data center in rural Kansas doesn't care about direct-to-cell communications or serving remote households. It cares about one thing: a low-latency, ultra-high-capacity, redundant connection to cloud providers and trading partners. Tera Wave delivers exactly that.

The timing also matters. AI data centers are exploding in demand. Companies are building massive compute facilities in locations far from traditional fiber backbones. They need connectivity, and they need it now. Traditional telecom companies can't deploy fiber fast enough. Satellite connectivity represents a bridge solution—available within months, not years, and with built-in redundancy.

Government customers present another lucrative market. Military operations, intelligence agencies, and homeland security all value satellite connectivity for the same reason enterprises do: they need it to work when terrestrial infrastructure fails. Government contracts are often worth enormous sums and come with long-term stability.

Amazon Leo is also positioning itself for the enterprise market eventually. But by announcing Tera Wave now, Blue Origin stakes a claim to enterprise customers early. The company signals deep commitment to that market segment before Amazon Leo even launches.

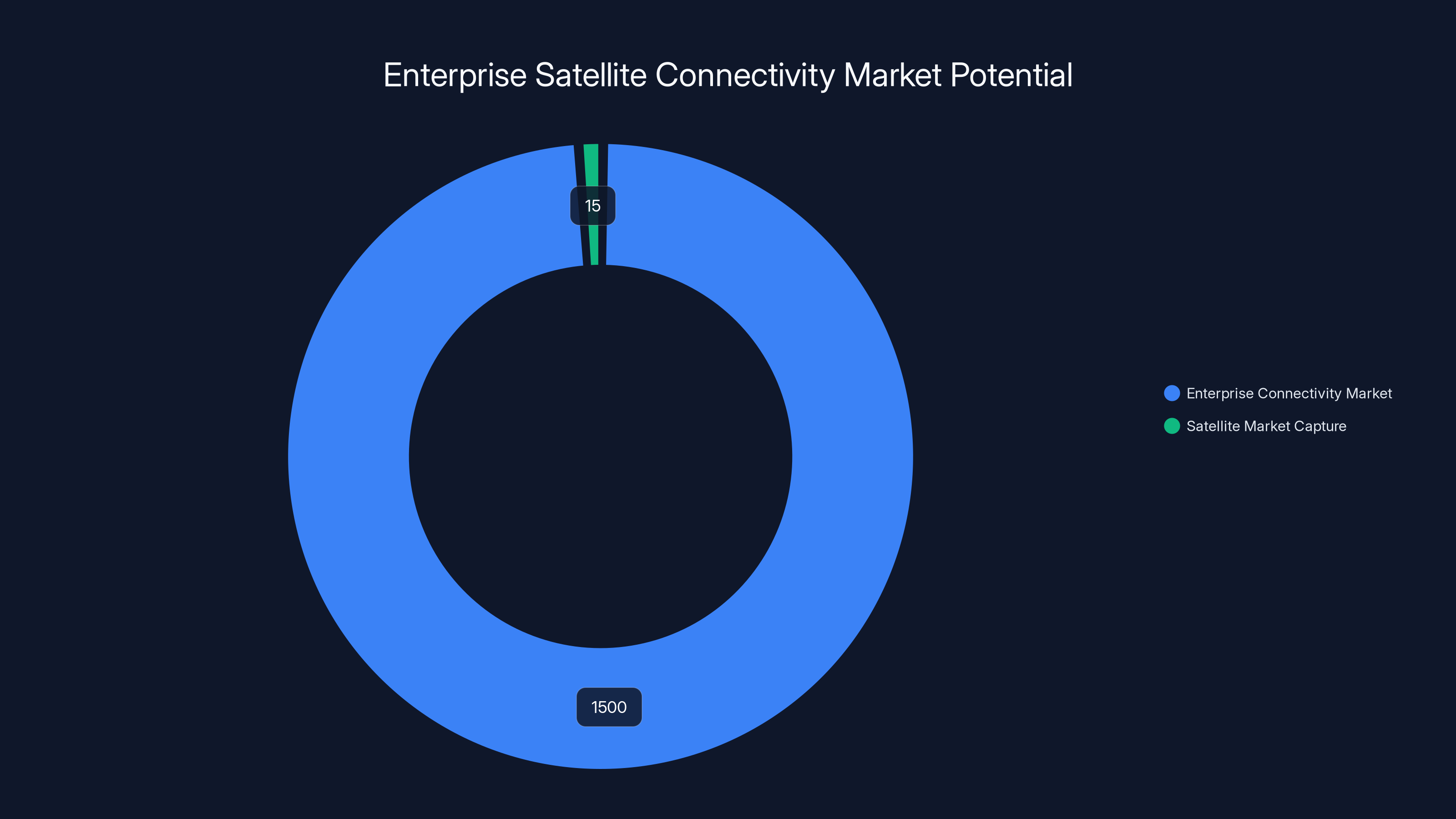

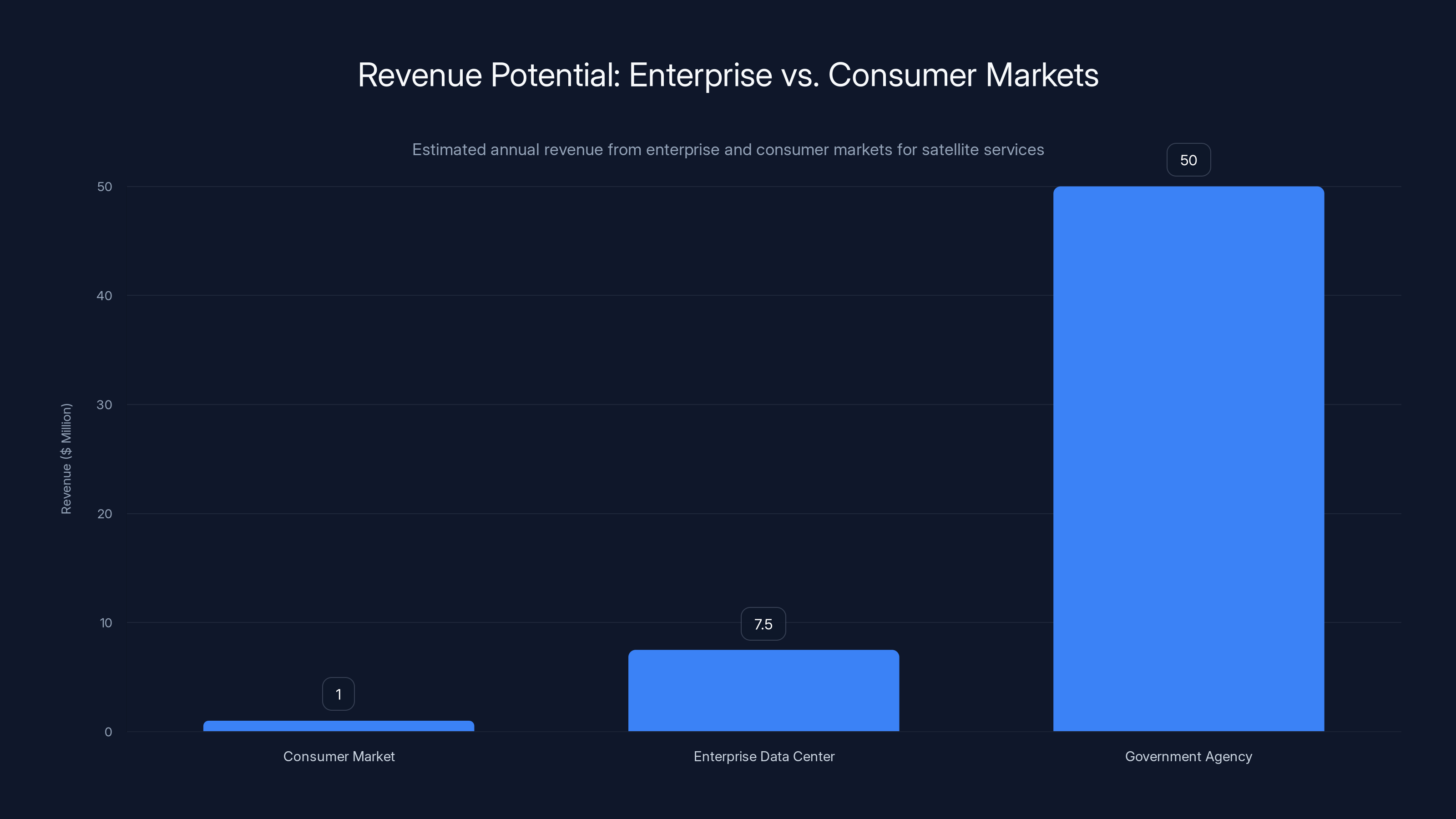

If satellite connectivity captures 1% of the enterprise market, it represents a $15 billion opportunity annually. (Estimated data)

The Resource Allocation Problem: Blue Origin's Ambitious Portfolio

Here's where reality gets complicated.

Blue Origin has an extraordinary list of concurrent programs:

- New Glenn rocket (heavy-lift launch vehicle)

- Blue Moon lunar landers (multiple variants for NASA)

- Blue Ring spacecraft (orbital support vehicle)

- Orbital Refueling Depot (fuel transfer in space)

- Blue Alchemist (in-situ resource utilization)

- Orbital stations (commercial space station modules)

- Crew Capsule (commercial crew transport)

- Mars missions (long-term exploration objectives)

- Multiple space telescopes and science payloads

- Now: Tera Wave megaconstellation

Each of these represents a multi-year, multi-billion-dollar commitment. Managing them simultaneously requires organizational discipline, but Blue Origin has struggled with focus historically.

Lindo St. Angel, who leads the new Emerging Systems division overseeing Tera Wave, has impressive credentials. He spent 15 years at Amazon in various engineering roles before joining Blue Origin in late 2024. His mandate is to drive innovation in advanced aerospace technologies. That's a broad charter, and it suggests Blue Origin is creating a dedicated organizational structure to isolate Tera Wave from some of the competition for resources that has plagued the company.

But here's the catch: Tera Wave requires extraordinary manufacturing capacity. Building 5,408 satellites isn't like building five. Each satellite needs communication systems, power systems, attitude control, propulsion, inter-satellite optics, and a thousand components from hundreds of suppliers. The assembly line must be completely different from rocket manufacturing. The supply chain becomes a bottleneck.

Blue Origin says deployment begins in Q4 2027. That's roughly 36 months away. In that timeframe, the company must simultaneously:

- Finalize satellite design and complete rigorous testing

- Stand up manufacturing facilities with the capacity to produce satellites at scale

- Secure supply chain commitments for thousands of components

- Ramp up New Glenn launch cadence from its current pace

- Continue Amazon Leo launches

- Maintain all other ongoing programs

That's an aggressive timeline. It's not impossible—Space X has demonstrated that focused teams can achieve remarkable things. But Blue Origin's historical pace suggests the company moves deliberately rather than urgently.

How Tera Wave Compares to Starlink and Amazon Leo

Three major megaconstellations now exist or are in development. Understanding the differences matters for predicting winners.

Starlink's Approach: Space X has deployed over 6,000 satellites primarily serving consumers and SMBs. The constellation emphasizes low-cost production, aggressive deployment timelines, and direct-to-consumer service. Space X integrated satellite manufacturing into its existing production lines, which helped achieve scale. Starlink prioritizes latency and ubiquitous coverage over pure capacity. The business model revolves around monthly subscription fees—approximately $120 for residential service, higher for mobility and professional tiers.

Amazon Leo's Approach: Amazon originally conceived Leo to compete directly with Starlink on consumer broadband, eventually authorizing 3,236 satellites. But the real strategy appears to be providing connectivity to Amazon Web Services customers, supporting infrastructure backhaul, and potentially enabling direct-to-device communications. Amazon Leo satellites will be slightly different from Starlink's, optimized for AWS integration. The timeline has slipped multiple times, with deployment now expected in 2025-2026.

Tera Wave's Approach: Blue Origin explicitly targets enterprises, data centers, and governments. The constellation emphasizes redundancy and massive aggregate capacity over ubiquitous coverage. By using optical inter-satellite links, Tera Wave creates a managed backbone that can prioritize traffic and ensure reliability. The business model is enterprise contracts and government awards, not consumer subscriptions.

These aren't necessarily competing directly. A customer could theoretically use Starlink for consumer broadband, Amazon Leo for AWS connectivity, and Tera Wave for critical data center links. They serve different market segments.

However, there are overlapping use cases. Enterprise customers in remote locations might choose Starlink or Amazon Leo if the service meets their needs and costs less. Starlink has already proven its appeal to businesses, with premium service tiers reaching thousands of commercial customers. Amazon might price Leo competitively against Starlink for SMBs. Tera Wave would only win accounts where the premium on reliability and capacity justifies the higher cost.

Starlink leads in satellite count and consumer market focus, while Amazon Leo and TeraWave target enterprise and infrastructure markets. Estimated data based on strategic insights.

The Optical Inter-Satellite Link Technology

The technology enabling Tera Wave's differentiation deserves deeper examination.

Optical inter-satellite links (ISLs) use laser beams to transmit data between satellites. This approach has several advantages over traditional radio links. Laser signals are highly directional, so they don't spread energy in all directions like radio signals. They're immune to radio frequency interference. They achieve dramatically higher data rates—think tens of gigabits per second per link versus a few gigabits for radio. And they consume less power per bit transmitted.

But ISLs introduce complexity. Satellites move continuously. You need precision pointing systems to keep laser beams aligned between vehicles traveling at orbital velocities. The optics must be extremely robust to withstand radiation, temperature extremes, and micrometeorite impacts. The electronics must operate reliably without maintenance for years.

Companies like Mynaric have pioneered commercial optical inter-satellite link terminals. Their technology operates with about 99.9% availability in space environments. That's exceptional but means approximately 8.6 hours of downtime per year per link. For backup connectivity, that's acceptable. For primary connectivity, you need multiple redundant paths.

Tera Wave's architecture likely employs multiple laser links per satellite—perhaps four or six independent optical connections to nearby satellites. If one fails, traffic instantly routes through alternate paths. The mesh topology means no single satellite or link failure can disrupt service to customers.

Building this out across 5,408 satellites requires not just reliable optical terminals but sophisticated routing algorithms. Ground stations must compute optimal paths through the network based on real-time satellite positions and link status. That's a complex distributed computing problem, but it's solvable with modern techniques.

The real innovation is using optical ISLs not just for enhanced capacity but as the primary mechanism for resilience. Traditional constellations use ISLs as nice-to-haves. Tera Wave makes them fundamental to the business model.

Launch Cadence Requirements: Can New Glenn Deliver?

Here's the constraint that matters most: Blue Origin must launch 5,408 satellites to make Tera Wave real.

Space X launches roughly 50 Starlink satellites per Falcon 9 mission. That requires approximately 110 launches to deploy a full Starlink constellation. Space X achieves this by launching multiple Falcon 9 rockets per month—they've demonstrated over 50 launches annually in recent years.

New Glenn is far larger than Falcon 9. It's designed to carry 140-ton payloads to low-Earth orbit. A single New Glenn launch could potentially carry 100-150 Tera Wave satellites. That would reduce the total launch count to perhaps 40-50 missions. But that still requires launching New Glenn roughly 10-12 times per year to meet the aggressive deployment timeline.

New Glenn has only flown twice successfully as of early 2025. It recently achieved first-stage booster landing in November, which is a major milestone. But the rocket is still in the early operational phase. Ramping from 2 flights to 12+ annual flights is a steep acceleration curve.

Moreover, Blue Origin has already committed New Glenn launches to Amazon Leo. The rocket's manifest includes dozens of Amazon Leo launches, plus other government and commercial customers. Adding 40-50 Tera Wave launches on top of that would require extraordinary manufacturing and logistics capability.

Space X solved this by building multiple production lines for Falcon 9 boosters and creating an efficient operational cadence. Blue Origin would need similar capabilities, but the company has historically taken a more conservative approach to launch operations.

One possibility: Blue Origin could use other launch vehicles. Space X's Starship, once operational, could carry an enormous payload. Amazon Leo has already launched some satellites on Space X's Falcon 9 due to New Glenn delays. Blue Origin could follow a similar strategy, distributing Tera Wave launches across multiple providers.

But relying on competitors to launch your constellation is strategically uncomfortable. It means depending on Space X's schedule and priorities. For a megaconstellation business model to work, you need reliable, controllable launch capacity.

Enterprise and government markets offer significantly higher revenue potential per customer compared to the consumer market. Estimated data based on typical contract values.

The Data Center Connectivity Angle: Why Now?

Tera Wave's timing isn't random. It aligns with the explosion in AI data center construction.

Every major technology company is building new data centers to support AI model training and inference. These facilities require enormous amounts of connectivity. Traditional approaches involve installing fiber optic cables, which can take years to deploy and cost hundreds of millions of dollars.

But fiber isn't always practical. A data center in rural New Mexico or Montana can't wait three years for fiber deployment. And building redundant fiber routes to ensure business continuity is prohibitively expensive.

Satellite connectivity solves this. You can activate it within months. Tera Wave's promised 144 Gbps per link is more than sufficient for data center backhaul. Multiple user terminals provide redundancy. The total cost, while substantial, might be lower than building new fiber infrastructure.

There's also the question of latency. Traditional satellite internet has high latency—200-300 milliseconds is typical. That's acceptable for web browsing but problematic for real-time financial trading or low-latency AI applications. Low-Earth orbit satellites like those in Tera Wave's constellation achieve much lower latencies—perhaps 20-40 milliseconds. That's still higher than fiber (which travels at the speed of light through glass, giving latencies of a few milliseconds), but increasingly acceptable for data center applications.

Blue Origin's announcement specifically mentions AI data centers and orbital data centers as potential use cases. The company has been exploring in-situ resource utilization and orbital manufacturing. There's speculation that Blue Origin might eventually want to operate data centers in space powered by solar panels and cooled by the vacuum. Sounds science fiction, but the economics are intriguing—unlimited thermal dissipation, proximity to the vacuum, and renewable power. Tera Wave could serve as the connectivity backbone for such operations.

More immediately, Tera Wave could bridge the gap for terrestrial data centers in remote locations by providing the redundant, high-capacity connectivity they need.

Government and Military Applications

Blue Origin explicitly mentions government users as target customers for Tera Wave.

The U.S. Space Force and military branches have invested heavily in satellite communications. Traditional military satellites are expensive, limited in number, and increasingly vulnerable to adversaries. A large, diverse constellation like Tera Wave distributes the risk—destroying one satellite doesn't degrade the network.

The laser inter-satellite links also offer military advantages. Laser communications are harder to jam and intercept compared to radio signals. The distributed nature makes the network resilient to adversary attempts to disrupt it. For command and control of military operations, that resilience is invaluable.

The Intelligence Community also operates satellite communications networks. Tera Wave's capacity and redundancy appeal to agencies that need assured connectivity for surveillance, reconnaissance, and intelligence operations.

Government contracts also fund development. The Space Force has initiatives like Space Mobility and Logistics and Next-Generation Satellite Communications. Blue Origin could potentially secure contracts that accelerate Tera Wave development while reducing the company's capital requirements.

One precedent: Space X initially developed Falcon 9 with significant investment from NASA and military contracts. Those relationships helped fund early development. Blue Origin could follow a similar strategy, using government demand to bootstrap Tera Wave.

However, government programs also introduce constraints. Approval processes are lengthy. Requirements often demand capabilities beyond initial designs. And if the government becomes a primary customer, commercial rollout might be delayed while military needs are prioritized.

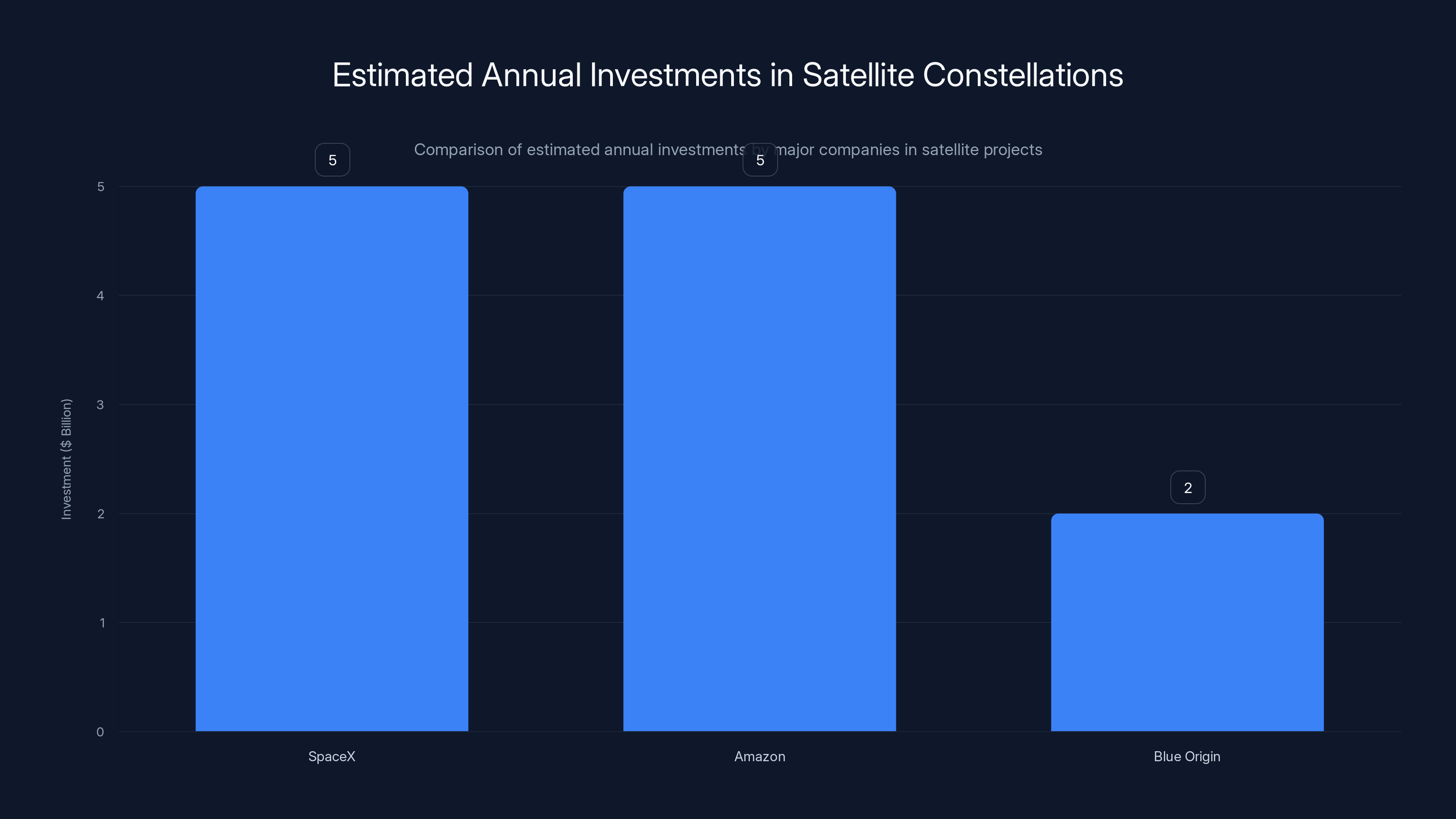

Estimated data shows SpaceX and Amazon investing around

Financial Implications and Capital Requirements

Building a 5,408-satellite constellation isn't cheap.

Space X invested an estimated $5-10 billion to develop and deploy Starlink (including satellite and launch vehicle development). Amazon's investment in Leo is estimated at similar or higher amounts. Blue Origin would need comparable capital.

But Blue Origin doesn't face the same startup constraints as Space X did. The company benefits from decades of experience and Bezos' willingness to fund ambitious projects. Amazon has committed to launching Amazon Leo, which generates operational experience and revenue that can fund related programs. And Blue Origin operates from a position of organizational maturity.

The question is whether Blue Origin will commit the necessary capital. Bezos has historically invested enormous sums in Blue Origin—estimates suggest over $2 billion annually at various times. But that funding supports all Blue Origin programs. Tera Wave adds to the portfolio, meaning either increased total funding or reallocation from other programs.

One possibility: Blue Origin could pursue investment or partnerships to fund Tera Wave. The company could approach strategic partners like telecommunications companies, data center operators, or government agencies for co-investment. That would reduce Blue Origin's capital burden while securing customer commitments.

Alternatively, Blue Origin could pursue a public offering or debt financing. The company isn't currently public, but going public could provide capital for expansion. Space X has remained private while achieving extraordinary valuation increases—Space X is now valued above $200 billion. Blue Origin could pursue a similar path, raising capital through strategic investors or eventually a public offering.

Supply Chain Challenges and Manufacturing Scale

Building thousands of satellites requires a robust supply chain and manufacturing ecosystem that Blue Origin is still developing.

Satellite components are highly specialized. Optical terminals for inter-satellite links come from a handful of suppliers globally. Radiation-hardened electronics must meet exacting specifications. Power systems must provide reliable performance in the harsh space environment. Each component represents a potential bottleneck.

Blue Origin would need to establish long-term supply agreements ensuring component availability. That requires negotiating with suppliers, often securing exclusive or priority allocations. Some suppliers might demand volume commitments or upfront investments to expand capacity.

Manufacturing assembly also requires significant capital. Space X solved this by building massive production facilities and integrating satellite manufacturing with rocket production. Blue Origin would need to construct similar facilities or contract with manufacturers.

Another consideration: Blue Origin's existing relationships with suppliers. New Glenn manufacturing, lunar lander development, and other programs already stress supply chains. Tera Wave would compete for the same suppliers and manufacturing capacity.

This creates a potential vicious cycle. Without demonstrated manufacturing capability, suppliers are reluctant to commit. Without supplier commitments, Blue Origin struggles to demonstrate feasibility. Breaking this cycle requires demonstrating credibility, either through prototype production or securing anchor customers who commit to the constellation.

Space X broke this cycle through persistence and willingness to accept failures. The company built prototypes, tested them, learned from failures, and iterated rapidly. Blue Origin has historically moved more slowly, which has worked well for human spaceflight but might not work for satellite production.

Estimated data suggests Starlink will dominate consumer broadband, Amazon Leo will target AWS customers, and TeraWave will focus on premium enterprise accounts.

Competitive Response: What Will Space X and Amazon Do?

Tera Wave's announcement won't go unanswered.

Space X's Response: Space X might argue that Starlink already serves enterprise customers through custom solutions. The company could develop premium tiers with higher reliability, managed service options, or private network capabilities. Space X could also compete on price—Starlink's economies of scale could allow aggressive pricing that undercuts Tera Wave.

Alternatively, Space X might focus on Starship's massive lift capacity. Starship can deliver enormous payloads to orbit. Space X could deploy a constellation of giant relay satellites or concentrated capacity hubs, solving the redundancy problem differently than Tera Wave's approach.

Amazon's Response: Amazon Leo will eventually launch. When it does, Amazon can leverage AWS integration as a competitive advantage. Customers using AWS could get preferential rates or seamless connectivity between data centers and the satellite network. Amazon's scale and customer base provide distribution channels Starlink and Blue Origin lack.

Amazon could also accelerate Leo's deployment timeline in response to Tera Wave. The company has the capital and organizational ability to move faster if threatened.

Other Competitors: Other companies are also developing constellations. UK-based One Web, Chinese companies like Guowang and Hongyun, and smaller startups are pursuing various approaches. Tera Wave's entry increases competition but also validates the market—if Blue Origin sees enough opportunity for a major investment, that signals to investors and customers that satellite connectivity for enterprises is a genuine business.

The most likely outcome: Market segmentation. Different constellations serve different customers based on price, coverage, reliability, and latency requirements. Starlink dominates consumer broadband. Amazon Leo serves AWS customers and SMBs. Tera Wave serves premium enterprise and government accounts. There's enough market to support multiple players, but scale and execution will determine winners.

Technical Risks and Unknown Challenges

Tera Wave faces significant technical risks that the announcement doesn't address.

Optical Inter-Satellite Link Reliability: While Mynaric and others have demonstrated ISL technology, operating thousands of laser links across 5,408 satellites simultaneously is unprecedented. Orbital debris poses risks—a small particle hitting an optical terminal could disable it. Micrometeorite impacts, radiation, and thermal stress all threaten reliability.

Routing Complexity: Managing traffic across thousands of satellites requires sophisticated algorithms. Computation must happen in real time as satellites move. If routing fails, network performance degrades catastrophically. This is a complex distributed systems problem with no existing precedent.

Orbital Mechanics and Collision Avoidance: With 5,408 satellites, all under active control and regularly maneuvering, collision risks are significant. The orbital environment is increasingly crowded. Active debris removal or maneuvering might be necessary to maintain safe spacing. This adds operational complexity and cost.

Manufacturing Consistency: Building thousands of satellites at consistent quality is challenging. Each satellite must meet exacting specifications. Quality control and testing procedures must be rigorous. A single design flaw discovered after launch could affect thousands of units.

On-Orbit Operations: Maintaining a constellation of 5,408 satellites requires significant ground operations. Each satellite needs monitoring, some require occasional maneuvers to adjust orbital position, and failures require replacement launches. Operating costs scale with constellation size.

Regulatory Approval: Orbital coordination with other constellations is managed by international regulatory bodies. Tera Wave's deployment must be coordinated with existing satellites and approved by relevant authorities. Delays in approval could affect deployment timelines.

These risks are manageable but require exceptional engineering execution. The question isn't whether they're solvable but whether Blue Origin can solve them within the aggressive timeline.

Timeline Analysis: Can Blue Origin Deliver?

Blue Origin committed to beginning Tera Wave deployment in Q4 2027. That's approximately 36 months from the announcement.

For context, Starlink took roughly four years from first launch (2019) to achieving orbital constellation status with hundreds of satellites. Amazon Leo's timeline has slipped repeatedly. Neither constellation achieved their initial aggressive targets.

Blue Origin's 36-month timeline is very aggressive given the company's historical pace. However, a few factors could make it achievable:

-

Leveraging existing expertise: Blue Origin has experience with spacecraft design, propulsion systems, and orbital operations. Engineers can apply this knowledge to satellite design, potentially accelerating development.

-

Dedicated organizational structure: The Emerging Systems division provides focused management and resource allocation. Isolating Tera Wave from other Blue Origin programs could reduce internal competition for resources.

-

Funding availability: Bezos' willingness to invest massive capital can accelerate timelines if necessary. Additional hiring, facility construction, or supplier relationships can be expedited with sufficient investment.

-

Proven satellite designs: Blue Origin doesn't need to innovate all components from scratch. Existing spacecraft power systems, attitude control, and electronics can be adapted or licensed from suppliers.

However, the timeline also faces headwinds:

-

Manufacturing ramp: Standing up production facilities takes time. Even with accelerated timelines, 12-18 months for facility construction and tooling is realistic.

-

Supply chain delays: Optical terminals, specialized electronics, and other components have long lead times. Securing supplier capacity for 5,400+ satellites involves negotiations that take time.

-

Regulatory processes: Spectrum allocation, orbital coordination, and launch licensing can introduce delays.

-

Testing and validation: Rigorous testing of satellite designs and constellation operations can't be skipped without accepting risk. This takes time and can't be significantly accelerated.

A realistic assessment: Q4 2027 is achievable for initial deployment of a limited constellation—perhaps 100-200 satellites for validation. Full deployment of 5,408 satellites likely extends into 2029-2030, similar to Space X and Amazon's timelines.

Integration with Amazon Leo and Orbital Data Centers

One of the most intriguing aspects of Blue Origin's announcement is the implication of potential integration with Amazon's other space initiatives.

The announcement mentions that Blue Origin has begun preliminary work on orbital data centers. Combined with Amazon Leo and now Tera Wave, a comprehensive space infrastructure ecosystem emerges.

Imagine this scenario: AWS customers operate data centers in orbit, powered by solar panels, cooled by the vacuum, with unlimited thermal dissipation. Amazon Leo provides connectivity to terrestrial customers and cloud infrastructure. Tera Wave provides primary connectivity between orbital data centers and ground stations. Blue Origin's New Glenn launches the infrastructure, Blue Ring spacecraft maneuvers it into position, and Orbital Refueling Depots provide fuel for station-keeping.

This isn't necessarily the plan, but the pieces hint at ambitious long-term thinking. Bezos has always wanted to industrialize space. Amazon has invested heavily in building cloud infrastructure. Combining those ambitions in orbit would be a logical extension.

However, this integration could also create organizational conflicts. Amazon Leo and Tera Wave would compete for launch capacity. Orbital data centers would compete with terrestrial AWS facilities for customer workloads. Without careful management, these initiatives could undermine each other rather than reinforcing.

Alternatively, the initiatives could be compartmentalized—Amazon Leo serves consumer and commercial customers, Tera Wave serves premium enterprise and government customers, orbital data centers serve specific use cases requiring space-based computation. This segmentation would minimize conflicts while providing optionality.

Market Size and Revenue Potential

What's the addressable market for enterprise satellite connectivity?

The global telecommunications market is approximately

Tera Wave's capacity to serve tens of thousands of customers is meaningful. If each enterprise customer averages

Government contracts add to this opportunity. A single strategic contract with the Department of Defense or Intelligence Community could represent hundreds of millions of dollars. Multiple government agencies would multiply this opportunity.

However, capturing market share requires competitive pricing and superior service. Starlink has already proven satellite internet is viable and taken a significant share of premium broadband customers. Amazon Leo will bring AWS' customer relationships and pricing power. Blue Origin must offer sufficient differentiation to justify premium pricing.

The opportunity is real, but execution is critical. Building a megaconstellation is insufficient—customers must be convinced to adopt the service, migrate from existing providers, and commit long-term. That's a sales challenge equal to the engineering challenge.

Key Takeaways and the Road Ahead

Tera Wave represents Blue Origin's boldest statement yet about its competitive ambitions in space.

The constellation's focus on enterprise connectivity and redundancy addresses a genuine market need. Companies require reliable, high-capacity connectivity, and satellite can deliver better than terrestrial alternatives in many scenarios. The technical approach—optical inter-satellite links, dual-orbit architecture, mesh routing—demonstrates sophisticated engineering.

But execution remains uncertain. Blue Origin has announced ambitious programs before with mixed results. The company operates more slowly than Space X, which could make the Q4 2027 timeline unrealistic. Resource competition across Blue Origin's numerous programs could starve Tera Wave of necessary investment.

Yet the strategic logic is sound. Bezos owns Amazon, which needs connectivity. He owns Blue Origin, which can build and launch infrastructure. By controlling both ends—the customer (AWS) and the infrastructure (Tera Wave)—Amazon/Blue Origin can capture more value than either company could independently.

The space industry is transitioning from government programs and experimental ventures to genuine commercial infrastructure. Megaconstellations are part of that transition. Starlink proved the concept is viable. Amazon Leo will validate it further. Tera Wave will accelerate the transition by targeting premium customers willing to pay for superior service.

For competitors, Tera Wave represents a validation that the satellite connectivity market is large enough to support multiple entrants. For customers, it means more options and competitive pricing. For the space industry, it signals that the next frontier isn't just reaching space—it's building permanent, economically viable infrastructure in orbit.

Blue Origin's announcement changes the conversation. The race for global broadband isn't over, but a new race for enterprise connectivity and orbital infrastructure is beginning. Tera Wave is Blue Origin's first major move in that race. Whether it succeeds depends on execution, capital commitment, and leadership focus over the next 3-5 years.

FAQ

What exactly is the Tera Wave megaconstellation?

Tera Wave is a planned satellite constellation consisting of 5,408 satellites designed by Blue Origin to provide enterprise and government customers with ultra-high-capacity, reliable connectivity. The constellation combines low-Earth orbit satellites (for radio access) with medium-Earth orbit satellites (for optical relay), enabling total data rates up to 6 terabits per second across the entire network. Unlike consumer-focused constellations like Starlink, Tera Wave prioritizes redundancy and reliability for mission-critical operations.

How does Tera Wave's architecture differ from Starlink or Amazon Leo?

Tera Wave uses optical inter-satellite links between satellites to create a redundant mesh network, while Starlink and Amazon Leo rely primarily on radio connections. Tera Wave's dual-orbit design (low-Earth and medium-Earth) allows it to deliver 144 Gbps via radio while achieving much higher rates through optical links. Starlink focuses on consumer broadband and prioritizes ubiquitous coverage; Tera Wave targets enterprise and government customers where reliability and capacity matter more than universal availability. Amazon Leo will serve AWS customers and consumers, positioning itself as a competitor to Starlink.

Why is Blue Origin building another satellite constellation when Amazon Leo already exists?

Blue Origin and Amazon are separate companies with different market focuses, though both are owned by Bezos. Amazon Leo targets consumers and AWS integration, operating as a traditional broadband service. Tera Wave targets premium enterprise and government customers where high reliability and massive capacity justify premium pricing. The markets are large enough to support multiple constellations serving different segments. Additionally, Tera Wave's announcement signals Blue Origin's commitment to the enterprise market before Amazon Leo even launches, helping the company secure early customer contracts.

What are the key technical innovations in Tera Wave?

The primary innovation is using laser-based optical inter-satellite links as the network backbone to ensure redundancy and resilience. Unlike radio links, laser communications are immune to radio frequency interference and achieve much higher data rates with lower power consumption. The mesh topology means no single satellite or link failure can disrupt service—data automatically reroutes through alternate paths. This approach trades increased complexity for dramatically enhanced reliability, making it ideal for enterprise and government applications.

When will Tera Wave actually launch and become operational?

Blue Origin announced deployment would begin in Q4 2027, approximately 36 months from the announcement. However, that timeline is very aggressive. Space X took four years to build a sizable Starlink constellation, and Amazon Leo's deployment has repeatedly slipped. A realistic assessment suggests initial deployment of 100-200 validation satellites could occur in late 2027, but full constellation deployment would likely extend into 2029-2030. The actual timeline depends on Blue Origin's manufacturing ramp-up, New Glenn launch cadence, and supply chain execution.

How many launches will Blue Origin need to deploy Tera Wave?

With New Glenn capable of carrying approximately 100-150 satellites per launch, Blue Origin needs roughly 40-50 New Glenn launches to deploy the full 5,408-satellite constellation. That translates to approximately 10-12 launches annually throughout the deployment period. New Glenn has only flown twice as of early 2025, so ramping to that cadence represents a significant acceleration. Blue Origin would need to achieve manufacturing and operations capabilities comparable to Space X's Falcon 9 program, which took years to develop.

How much will Tera Wave cost, and who will pay for it?

Building a 5,408-satellite constellation typically costs

What are the main risks to Tera Wave's success?

Major risks include: (1) Manufacturing at scale—building thousands of identical satellites reliably; (2) Optical inter-satellite link reliability—the technology is proven but operating thousands of laser links simultaneously is unprecedented; (3) Launch cadence—Blue Origin must accelerate New Glenn operations significantly; (4) Orbital operations complexity—managing thousands of active satellites and routing decisions in real-time; (5) Customer adoption—enterprises must be convinced to switch from terrestrial connectivity to satellite; (6) Resource competition—other Blue Origin programs may starve Tera Wave of necessary investment. Execution risk is substantial, and delays are likely.

Could Tera Wave compete with Space X's Starlink or Amazon Leo?

Tera Wave doesn't directly compete with Starlink's consumer broadband or Amazon Leo's AWS-integrated service because it targets different customers (premium enterprise and government). However, there will be overlapping use cases. Enterprise customers in remote locations might choose Starlink if the service meets their needs at lower cost. Space X could develop premium Starlink tiers with higher reliability. Amazon Leo could offer competitive enterprise services leveraging AWS relationships. The market is large enough for multiple providers, but Tera Wave's success depends on demonstrating enough differentiation (redundancy, capacity) to justify premium pricing.

What does this mean for the future of satellite internet?

Tera Wave's announcement validates that satellite connectivity is becoming serious infrastructure, not just a niche service. The massive investment from Blue Origin signals that large, profitable markets exist beyond consumer broadband. It accelerates the transition from satellites as government tools to satellites as essential commercial infrastructure. Within a decade, expect satellite connectivity to be as commonplace as fiber optic cables, with different constellations serving different use cases. This could revolutionize connectivity in remote locations and provide true global redundancy for critical operations.

Is orbital data center integration part of Tera Wave's plan?

Blue Origin mentioned beginning preliminary work on orbital data centers alongside the Tera Wave announcement. While details are limited, the implication is that Tera Wave could serve as the connectivity backbone for data centers operating in orbit. This would represent an ambitious vision combining several Blue Origin capabilities: New Glenn for launches, Blue Ring for spacecraft operations, orbital refueling depots for station-keeping, and Tera Wave for connectivity. However, whether these initiatives integrate or remain separate remains unclear. If integrated, it would represent one of the most ambitious space infrastructure projects ever attempted.

Related Articles

- SpaceX's 7,500 New Starlink Satellites: What It Means [2025]

- SpaceX's 15,000 Starlink Gen2 Satellites: What It Means [2025]

- NASA's Commercial Space Station Crisis: Senate Demands Timeline [2025]

- SpaceX's 7,500 New Starlink Satellites: What the FCC Approval Means [2025]

- Starlink's Free Internet Push in Venezuela: What It Means [2025]

- SpaceX Lowers Starlink Satellites to Reduce Collision Risk [2025]

![Blue Origin's TeraWave Megaconstellation: The 6Tbps Satellite Internet Game Changer [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/blue-origin-s-terawave-megaconstellation-the-6tbps-satellite/image-1-1769022466446.jpg)