Introduction: The Shift in Blue Origin's Lunar Ambitions

When Blue Origin first announced plans for the third launch of its New Glenn mega-rocket, space enthusiasts everywhere perked up. The company had been pretty clear about one thing: they were taking their robotic lunar lander to the moon. The Blue Moon Mark 1 was supposed to be the grand finale of this launch trifecta, cementing Blue Origin's place in the new era of commercial lunar exploration.

Then came January 2026, and suddenly everything changed.

Instead of aiming for the lunar surface, the third New Glenn launch will instead carry satellites for AST Space Mobile to low-Earth orbit. No moon. No historic lunar touchdown. Just a straightforward commercial satellite delivery mission in late February.

On the surface, this looks like a pivot. A disappointment, even. But dig deeper, and you'll see something more interesting happening here. Blue Origin isn't abandoning its lunar ambitions or suddenly losing confidence in New Glenn. Instead, the company is making a calculated decision about sequencing, resources, and what actually matters right now in the space industry.

Let's break down what's happening, why it matters, and what this tells us about where commercial spaceflight is headed in 2026 and beyond.

The New Glenn Mega-Rocket: Understanding the Context

Before we talk about why the third launch is changing course, it's worth understanding what New Glenn actually is and why it represents such a significant milestone for Blue Origin.

New Glenn is no small achievement. The rocket spent over a decade in development, which might sound like a long time until you realize how complex orbital launch vehicles actually are. This isn't like updating software. You're building something that needs to withstand extreme temperatures, massive acceleration forces, and the harsh environment of space. The slightest miscalculation or manufacturing flaw can turn into a catastrophic failure.

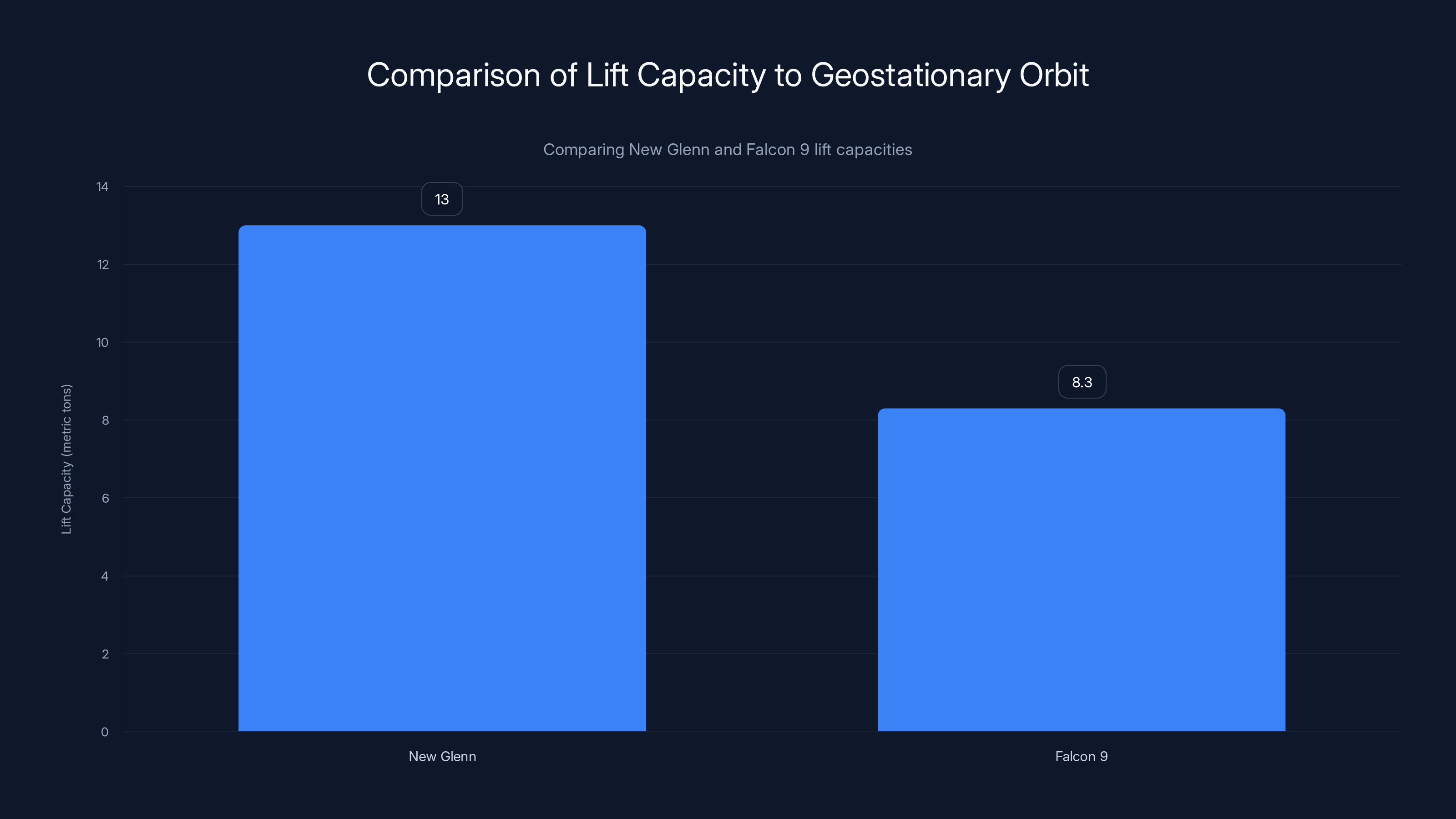

The rocket itself is enormous. We're talking about a two-stage orbital launch vehicle that can carry 13 metric tons to geostationary orbit. That's serious lift capacity. For context, SpaceX's Falcon 9 carries roughly 8.3 metric tons to the same orbit. New Glenn isn't just playing in the same sandbox. It's a bigger shovel.

What makes New Glenn particularly interesting is that it's Blue Origin's first vehicle specifically designed for regular orbital and beyond-orbital missions. The company spent years with New Shepard, their suborbital vehicle that takes tourists to the edge of space. That was fun, profitable, and good for brand building. But New Shepard doesn't go to orbit. New Glenn does. And it does it in a way that suggests Blue Origin learned from watching SpaceX master reusability.

The first two New Glenn launches happened remarkably close together, which itself is worth noting. Blue Origin successfully flew the rocket twice in a little over a year. The second mission, which happened in November 2025, was particularly significant because it marked the first time the company recovered and plans to reuse the booster stage. That's the same strategy that made SpaceX dominant in the launch industry. Reusability is the game-changer.

For the third launch, Blue Origin is reusing that recovered booster. This is exactly what needs to happen if commercial spaceflight is going to become truly economical. Every time you reuse a booster, you're learning more about durability, refurbishment costs, and reliability. The data from this third flight will be crucial.

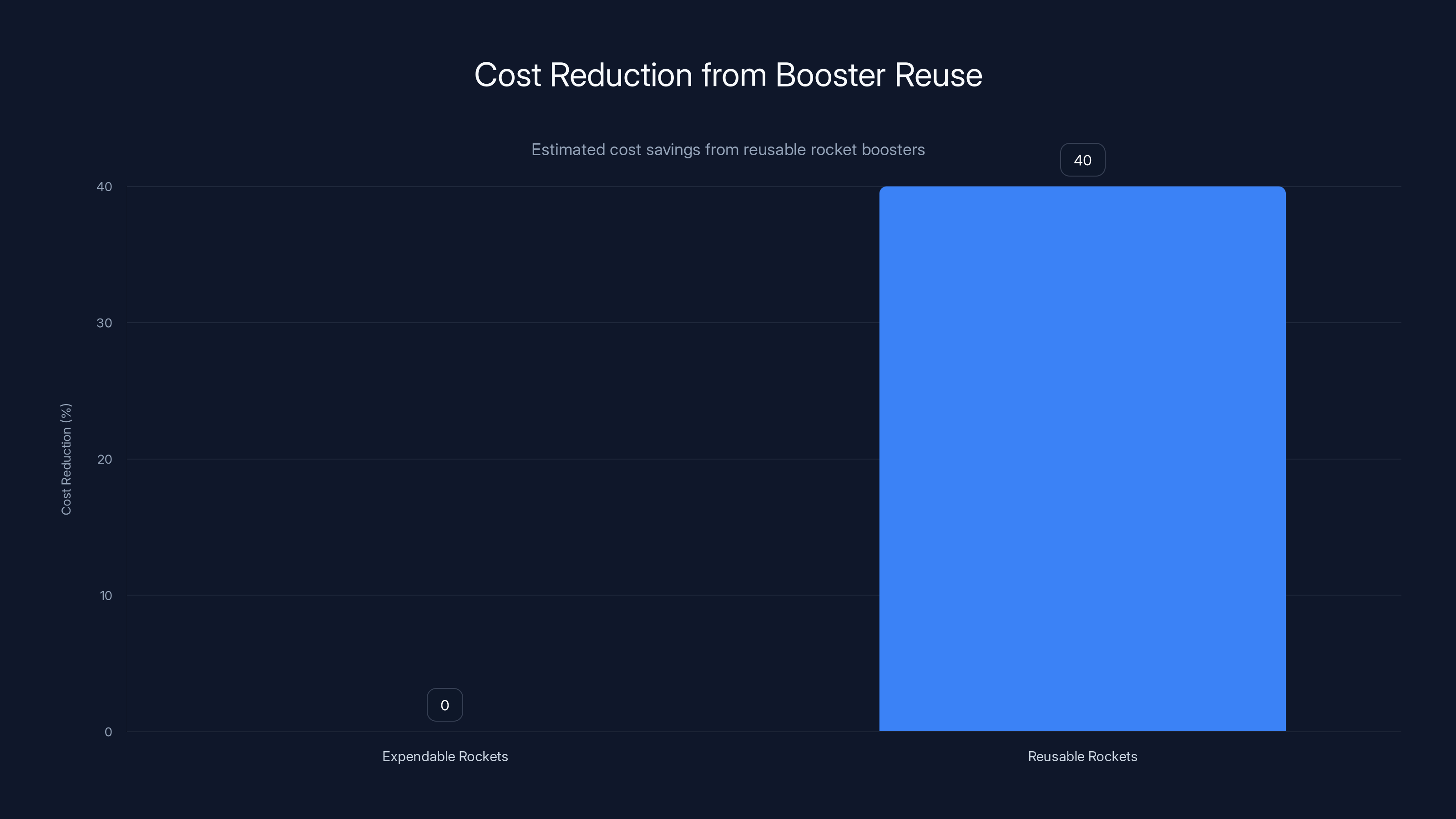

Reusing rocket boosters can reduce launch costs by approximately 30-50%, with an estimated average of 40% savings, making space access more economical. Estimated data.

Why Blue Moon Mark 1 Isn't Flying (Yet)

Here's where things get interesting. Blue Origin didn't explain why they delayed the lunar lander mission, but that silence actually speaks volumes.

The Blue Moon Mark 1 is currently being shipped to NASA's Johnson Space Center in Texas for vacuum chamber testing. Let that sink in. The lander isn't ready for flight. It needs testing. Real, thorough testing in conditions that simulate the space environment.

This makes complete sense, actually. The last thing Blue Origin wants is to send an unproven lander to the moon, have it fail, and become the company's most expensive paperweight. The lunar surface is unforgiving. There's no recovery team. There's no do-over. Once it's there, it's there forever, and if it doesn't work, everyone remembers that.

NASA learned this lesson the hard way with the Ranger spacecraft program in the 1960s. Early missions repeatedly failed because they weren't ready. Only after rigorous ground testing and analysis did the Ranger missions start succeeding. Blue Origin is taking that historical lesson seriously.

The vacuum chamber testing at Johnson Space Center will put the Mark 1 through simulated lunar conditions. Engineers will be able to watch how the lander's systems respond to the extreme cold, the vacuum, and all the other stressors it'll face on the moon. If something is going to break, better to find out now in Texas than on the lunar surface.

There's also the matter of timing and logistics. The Blue Moon program is part of NASA's Artemis program, which is developing the lunar infrastructure for sustained human presence on the moon. Blue Origin has contracts with NASA to provide lander services. These aren't arbitrary deadlines. They're coordinated with NASA's timeline, with other contractors, with the whole lunar development ecosystem.

Delaying the Mark 1 flight might actually be the smart play for multiple reasons. It gives NASA more time to prepare for the lander's arrival. It gives Blue Origin more time to ensure quality. And it keeps New Glenn flying on a schedule that makes commercial sense.

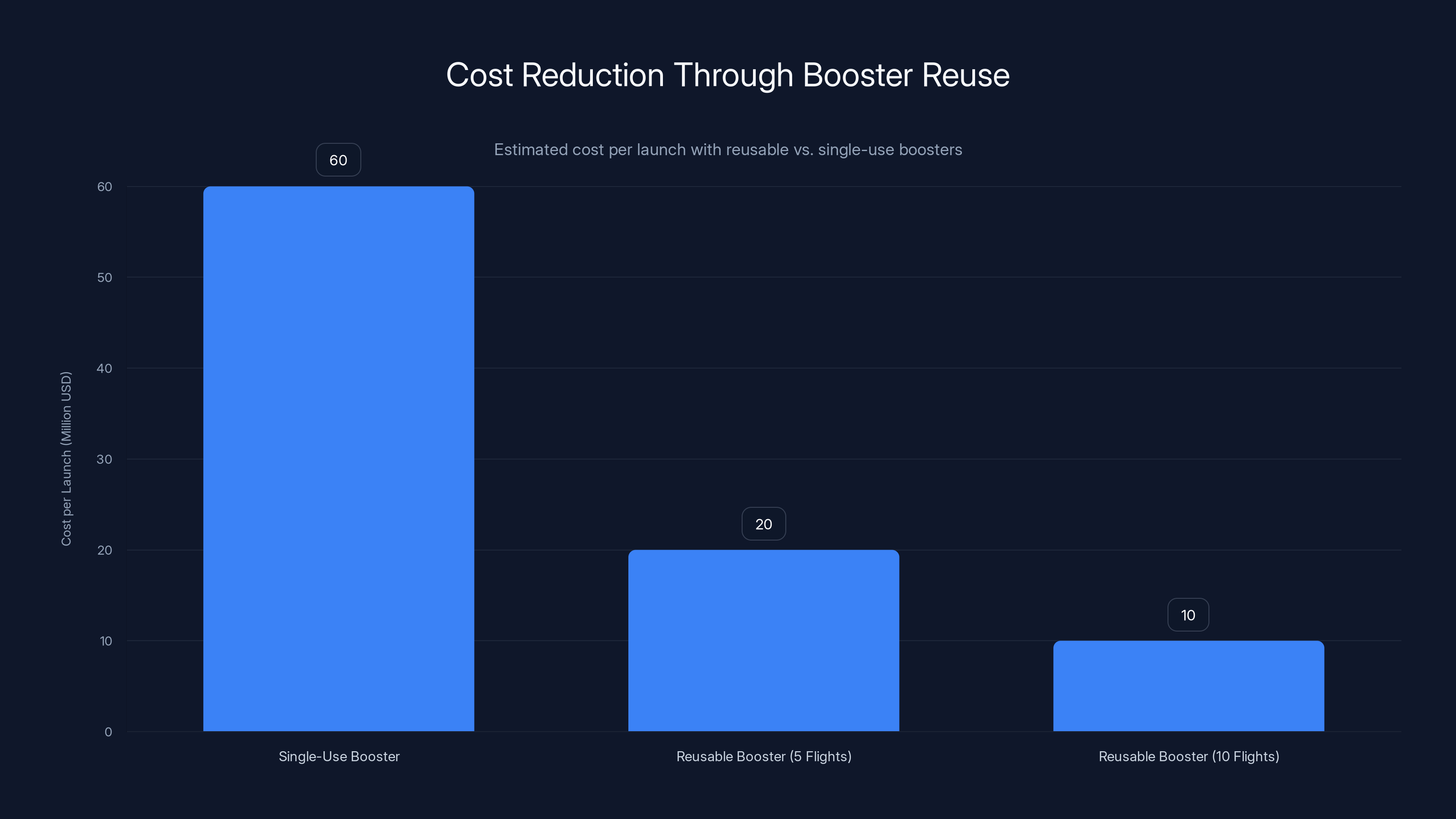

Reusing boosters significantly reduces the cost per launch. A booster reused for 10 flights can cut launch costs by up to 83% compared to single-use boosters. (Estimated data)

AST Space Mobile's Satellite Constellation: What's Actually Launching

So what exactly is heading to orbit on that third New Glenn flight? The answer is AST Space Mobile's satellites, part of their effort to build out a space-based cellular broadband network.

Let's talk about what AST Space Mobile is actually trying to do here, because it's pretty ambitious.

AST Space Mobile is trying to solve a problem that affects billions of people: lack of connectivity in remote areas. Terrestrial networks (cell towers on the ground) work great in populated areas. But vast regions of the planet have either no coverage or terrible coverage. Mountains, rural areas, oceans, deserts. These places are connectivity dead zones.

Satellite-based cellular broadband promises to change that. Instead of relying on ground infrastructure, AST Space Mobile is launching satellites that can provide cellular service directly to your phone. Your phone already has a receiver for satellite signals (that's how GPS works). The innovation here is making satellite networks actually work for cellular broadband at scale.

This is different from traditional satellite internet like Starlink or Viasat, which require special equipment. AST Space Mobile wants to work directly with standard smartphones. That's the game-changer.

Blue Origin has signed a deal with AST Space Mobile to send multiple satellites to orbit. This third New Glenn launch is the second commercial payload mission for the rocket. The first was also an AST Space Mobile deployment. So we're seeing a pattern here: Blue Origin is building a business relationship with AST Space Mobile, flying multiple missions for them.

This is exactly how the launch industry is supposed to work. You get a customer who has ongoing needs. You develop a reliable launch service. You fly them regularly. You build efficiency into the process. Revenue stabilizes. The company becomes sustainable.

From a pure business perspective, this is smarter than the alternative. Flying the Blue Moon lander to the moon is scientifically interesting and good for marketing. But AST Space Mobile launches are recurring revenue. They're predictable. They allow Blue Origin to keep New Glenn flying on a regular schedule.

The Timeline: Late February and a Very Busy Month in Space

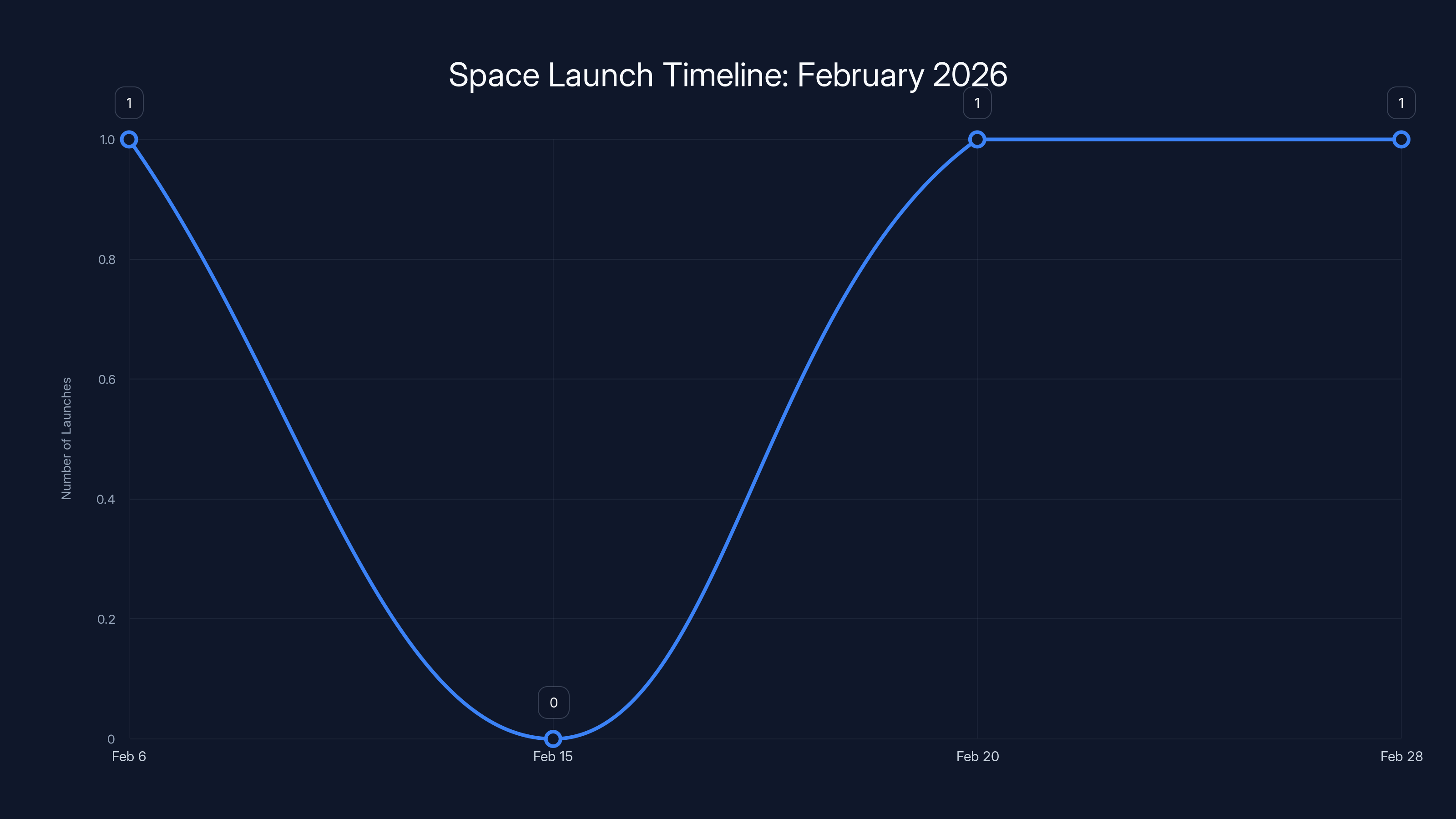

The third New Glenn launch targets late February 2026, which means we're looking at a specific, narrow window. Late February might sound vague, but in the launch industry, this is actually being pretty specific. You're talking about February 20-something, give or take a few days depending on weather and final preparations.

Why is this timing significant? Because February 2026 is absolutely packed with space activity.

First, there's NASA's Artemis II mission, which could launch as early as February 6. This is huge. Artemis II will send four astronauts around the moon (but not landing on it yet). The crew will orbit the moon, do science, test systems, and come home. This is the dress rehearsal for Artemis III, which will actually land astronauts on the lunar surface.

The Artemis II mission has been delayed multiple times already. NASA and NASA's contractors have been working through technical issues with the Space Launch System (SLS) rocket. Getting it to launch in early February would be a massive success and a relief for the entire program.

Second, SpaceX is expected to start testing the third iteration of its Starship rocket. You've probably heard about Starship. It's the vehicle that Elon Musk claims will eventually take humans to Mars. The third test flight (IFT-3) is going to be significant because SpaceX keeps iterating and improving. Each test gives them more data about how the vehicle actually performs versus how their models predicted it would perform.

Third, there's NASA's Crew-12 mission, which will launch astronauts to the International Space Station. This is part of the regular rotation of ISS crew, but it's particularly important because the Crew-11 team was medically evacuated earlier (due to health issues with returning astronauts), and the station needs to get back to full staff.

So in the span of a few weeks in February, you've got a lunar mission happening, a Starship test, and an ISS crew rotation. That's a lot of spaceflight activity. It's also evidence of how mature the commercial space industry has become. These missions are now routine enough to happen in clusters.

For Blue Origin's New Glenn launch to happen in late February, the company is choosing to launch after Artemis II and Starship IFT-3, but probably around the same time as Crew-12. This gives the launch corridors time to separate and reduces the risk of interference or congestion.

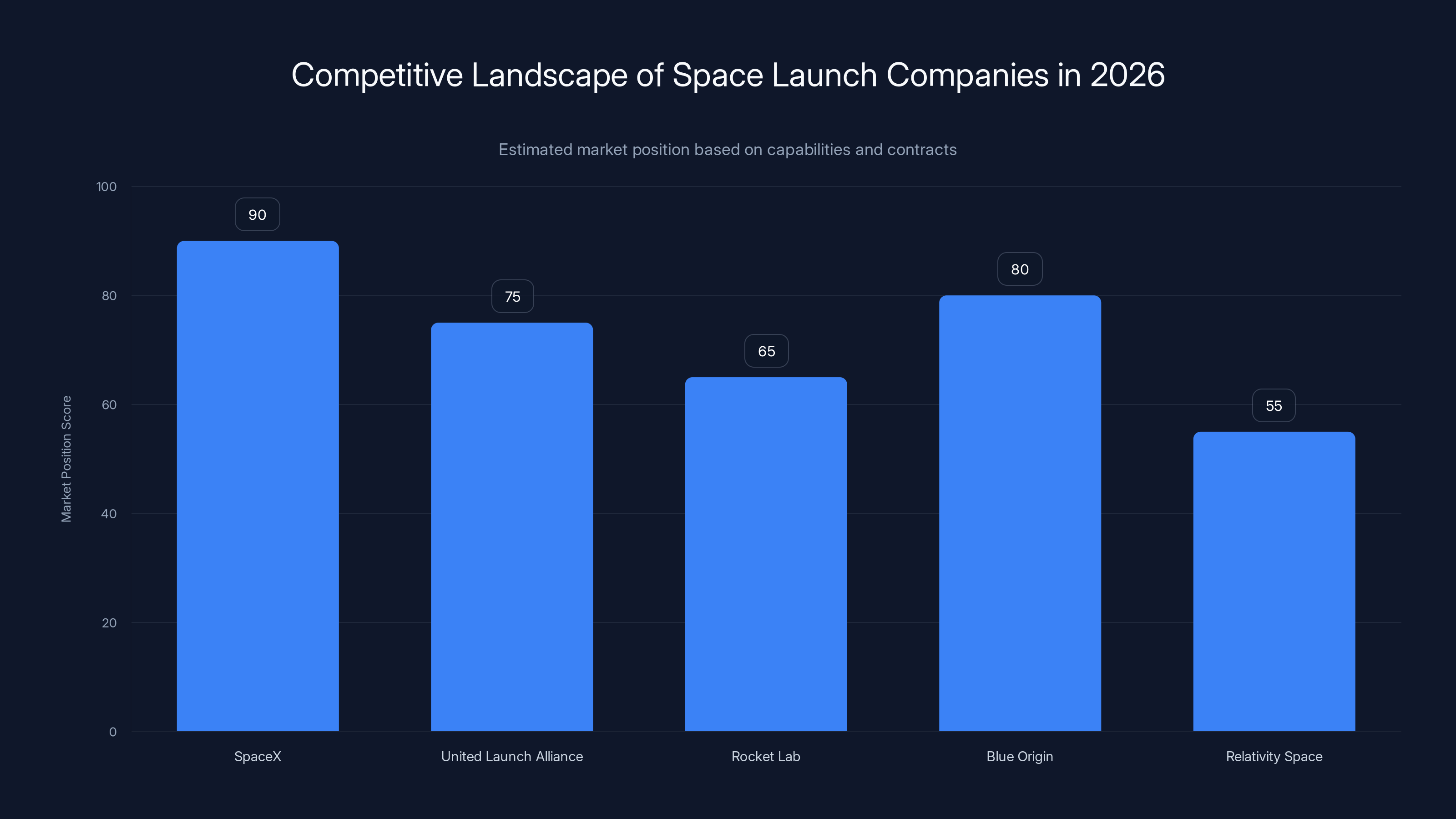

SpaceX leads with a strong reusable rocket strategy and diverse contracts. Blue Origin is competitive with New Glenn's heavy-lift capabilities. (Estimated data)

Booster Reuse: The Economic Engine Behind Modern Spaceflight

Here's something that deserves more attention than it usually gets: the third New Glenn launch will reuse the booster from the second mission. This is not a small detail. This is the foundation of modern spaceflight economics.

Let's think about what rocket boosters actually are and why reusing them matters so much.

A rocket booster is the first stage of a multi-stage launch vehicle. It's the massive engine and fuel tank that lifts the rocket off the ground and accelerates it to high speed before separating and falling back to Earth. The booster is the most expensive part of the rocket. It's the most complex. It's the part that does the most work.

For decades, boosters were single-use. You'd launch a rocket, the booster would fall back to Earth, crash into the ocean or land, and that was it. You'd just built a new booster for the next launch. Over time, multiple launches would cost an enormous amount of money because you were building a new, expensive booster each time.

SpaceX changed this game with the Falcon 9. They figured out how to recover the booster, land it safely, refurbish it, and fly it again. The first reused Falcon 9 booster flew in 2015. Now, SpaceX regularly reflies boosters. Some have gone to orbit over 10 times.

This is transformative for the industry because it fundamentally changes the cost structure. If you can fly a booster 10 times, the cost per flight drops dramatically. You're spreading the design, manufacturing, and testing costs across multiple missions instead of one.

Blue Origin is now doing the same thing with New Glenn. The booster from the second mission landed on a drone ship in the ocean (yes, they're literally using SpaceX's playbook). Now they're planning to refurbish it and fly it again for the third mission.

The significance of this cannot be overstated. It means Blue Origin is moving from experimental phase into operational phase. They're not just proving they can fly New Glenn once or twice. They're proving they can build a sustainable, reusable launch system.

There's a secondary benefit to booster reuse that's worth considering: validation and learning. Every time you refly a booster, you learn more about its durability, how refurbishment costs compare to your estimates, what wear patterns develop, and how performance holds up over multiple flights.

This data is incredibly valuable. It informs design improvements, refurbishment procedures, and long-term planning. Blue Origin will be taking detailed measurements of the recovered booster, examining every component, running diagnostics, and comparing actual data to theoretical predictions.

Then they'll prepare it for the third flight. This is where the real work happens. Refurbishment isn't simple. Components need inspection. Some might need replacement. Fluids need refreshing. Seals might need replacement. Avionics need verification. By the time the booster is ready for flight again, the team has spent hundreds of hours preparing it.

The team will also be making decisions about how many times they think this particular booster can safely fly. SpaceX publishes this information. Some Falcon 9 boosters have been designated for 10+ flights. Others for fewer. There's no universal number. It depends on the specific booster's condition, wear patterns, and remaining service life.

For the third New Glenn launch, we'll be seeing booster reuse as an operational reality, not an experiment. That's the milestone.

Blue Origin's Grander Vision: Beyond New Glenn

Here's what's easy to miss when you're focused on the third New Glenn launch: it's just one piece of a much larger puzzle that Blue Origin is assembling.

In November 2025, Blue Origin revealed something that made space enthusiasts sit up and pay attention: a super-heavy variant of New Glenn. We're talking about a rocket that will be taller than the Saturn V that took humans to the moon in the 1960s.

Let that sink in. Saturn V is 363 feet tall and could lift 130 tons to low-Earth orbit. It's the gold standard of launch vehicles. The fact that Blue Origin is building something comparable is significant.

This super-heavy variant of New Glenn isn't just a bigger rocket for the sake of being bigger. It's answering the question of what comes next for Blue Origin's launch business. If New Glenn is the medium-to-heavy lift vehicle, what about true super-heavy lift?

There are applications that only a super-heavy launch vehicle can serve efficiently. You could launch massive space stations. You could send heavy exploration missions beyond Earth orbit. You could deploy large constellations of satellites in a single flight. You could support human Mars missions with the kind of payload capacity that makes the economics work.

SpaceX's Starship is pursuing this same super-heavy lift capability. So is NASA's SLS. Blue Origin building a super-heavy New Glenn variant means they're staying competitive in this arena.

But there's more. Blue Origin also announced something called TeraWave, a satellite internet constellation that the company plans to start deploying in late 2027. This is Blue Origin's answer to Starlink.

Let's think about what this means. Blue Origin wants to not just launch rockets. They want to be a customer of their own rockets. They want to own and operate satellites in orbit providing internet service to billions of people.

This is actually a brilliant strategy. When you own the launch business and the satellite business, you control the entire value chain. You can integrate them in ways that competitors can't. You can optimize for your specific needs. You can make business decisions that favor both parts of the business.

And there's the Blue Ring spacecraft, another in-development vehicle that can host and deploy payloads for other space companies. This is Blue Origin positioning itself as an orbital infrastructure company, not just a launch provider.

When you step back and see the full picture, the delayed Blue Moon lander mission for the third New Glenn launch makes sense. Blue Origin is sequencing their efforts. They're flying commercial missions now, building revenue, proving reliability, and gathering data. They'll launch their own lander when the time is right.

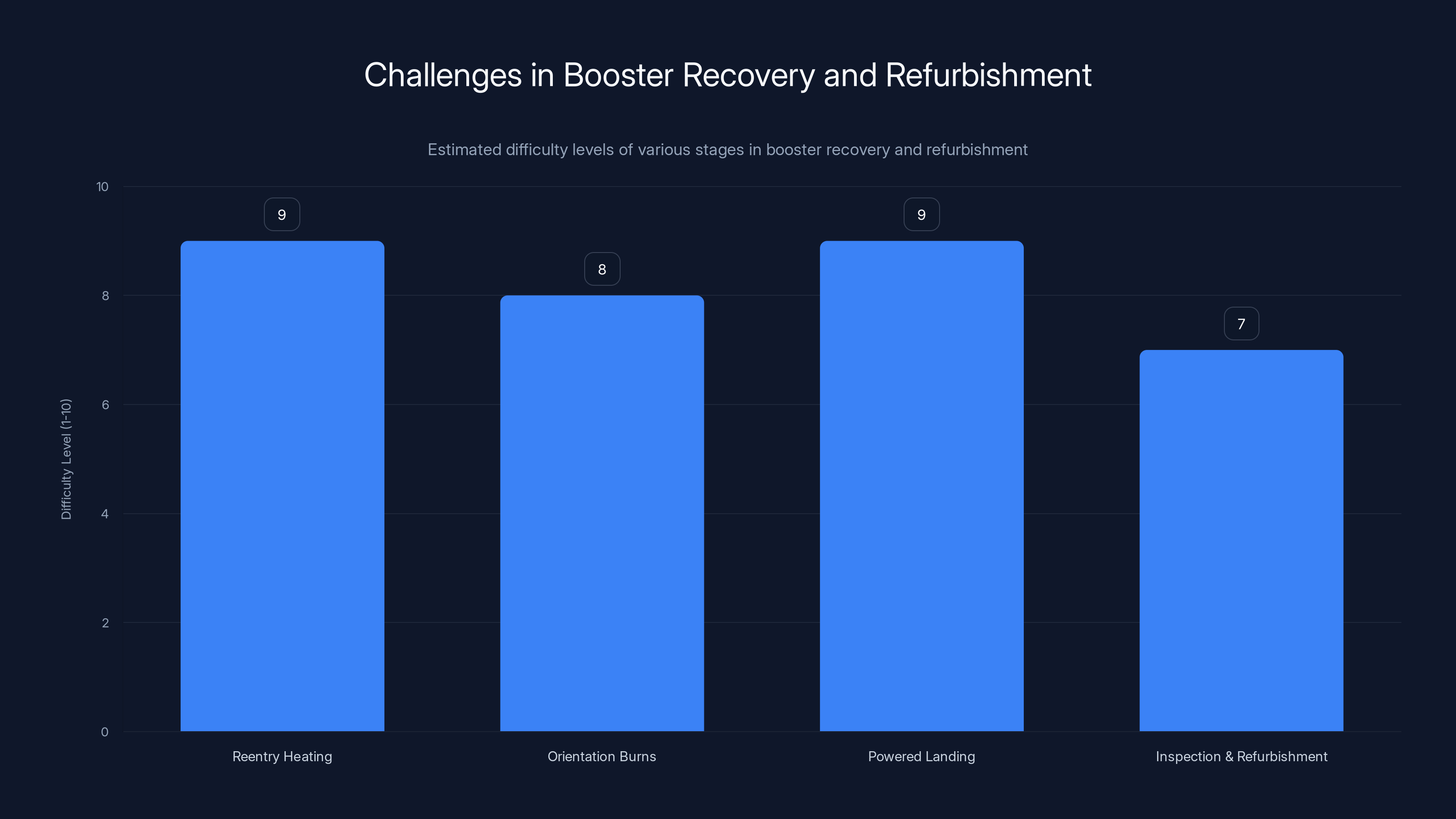

Reentry heating and powered landing are among the most challenging stages in booster recovery, requiring precise execution to avoid loss of hardware. (Estimated data)

The Broader Implications: Commercial Spaceflight Maturing

What's happening with Blue Origin's third New Glenn launch tells us something important about the state of commercial spaceflight in 2026.

For years, the narrative was dominated by single events. SpaceX lands a booster for the first time. Blue Origin takes tourists to the edge of space. Virgin Galactic finally gets to space. These were moments that got headlines because they were rare and significant.

Now we're in a different era. Companies are flying regularly. They're reusing hardware. They're building business relationships with customers. They're planning multi-year missions and constellations. The industry is moving from experimental to operational.

Blue Origin flying the third New Glenn with a reused booster carrying commercial satellites is mundane in the best way possible. It's not a historic first. It's Tuesday. It's what you do when you've got a working rocket, a paying customer, and a launch schedule to maintain.

This shift is important because it means the space industry is becoming reliable enough for people to build businesses on top of it. AST Space Mobile can plan their satellite constellation knowing they'll have launch capacity. They can sign multi-launch contracts with Blue Origin. They can commit to timelines and budgets with confidence.

That's economic maturity. That's the infrastructure layer solidifying under the space economy.

Technical Challenges in Booster Recovery and Refurbishment

While booster reuse sounds straightforward conceptually, the actual execution is brutally complex. Understanding the challenges gives you real insight into why this is such a big deal.

When a booster separates from the upper stage, it's traveling at hypersonic speeds at high altitude. The booster then needs to: survive reentry heating, perform orientation burns to change its trajectory, execute a powered landing with precision, and come to rest safely on a drone ship (or land pad).

Each of these steps involves extreme conditions and high stakes. One miscalculation and you lose the booster. You lose millions of dollars of hardware.

Once the booster is recovered, it's covered in soot from the reentry heating. The engines need inspection at component level. Every valve, connector, seal, and pump needs to be examined. Engineers need to determine what's reusable and what needs replacement.

Here's what's particularly tricky: predicting wear. For components that fly once, you design them with large safety margins. You make them strong enough that you're confident they'll work. But when something is going to fly 5, 10, or 20 times, you need different information.

You need to understand exactly how each component degrades. At what point does performance degrade enough that it needs replacement? What's the useful life? When do small cracks become problems? When does oxidation affect a critical surface?

This requires deep understanding and often empirical testing. SpaceX has published that some Falcon 9 boosters have been cleared for up to 10 or more flights. But they didn't know that going in. They learned it through experience, inspection, and testing.

Blue Origin will be going through the same learning curve with New Glenn. The recovery, inspection, and refurbishment of that booster for the third flight will generate crucial data.

New Glenn can carry 13 metric tons to geostationary orbit, significantly more than Falcon 9's 8.3 metric tons, highlighting its superior lift capacity.

Blue Moon Mark 1: What Makes It Different

While we're waiting for the Blue Moon Mark 1 lander to fly to the moon, it's worth understanding what makes this lander notable.

Blue Moon is designed as a cargo lander, not a crewed lander. It's built to carry up to 3,500 kg of payload to the lunar surface. That's serious cargo capacity. You can fit scientific instruments, equipment for experiments, supplies, and in the long term, equipment for establishing a lunar base.

The lander is part of Blue Origin's vision for lunar infrastructure. They're not just trying to land on the moon once for a photo. They're building towards sustainable presence.

Blue Moon's cargo capacity is comparable to other commercial lunar landers in development. SpaceX is developing Starship for much larger payloads. NASA is also working with companies like Axiom Space and others on various lunar vehicles.

What's interesting is that Blue Moon Mark 1 is designed to land near the lunar south pole, where there's evidence of water ice in permanently shadowed craters. Water ice is valuable for multiple reasons: it can be split into hydrogen and oxygen for rocket fuel, it can provide water for life support systems, and it's scientific data about lunar composition.

The lander will carry scientific instruments to study the lunar environment. It will validate systems and procedures for future missions. It will gather data that informs how humanity approaches sustained lunar presence.

When Blue Moon Mark 1 finally launches on New Glenn (probably not on the third flight, but on a future one), it will be a significant milestone. But as important is the data that lander returns and how Blue Origin uses that to improve subsequent missions.

TeraWave and Blue Origin's Satellite Internet Ambitions

Blue Origin's announcement of TeraWave satellite internet constellation in January 2026 deserves attention because it shows the company's ambitions extending beyond launch services.

We live in an era where multiple companies are building satellite internet networks. Starlink is the most visible, with thousands of satellites already in orbit. Amazon's Kuiper project is also building a constellation. Various other companies are pursuing satellite internet or satellite broadband in different ways.

TeraWave will be Blue Origin's network. The company plans to start deploying it in late 2027. That's a fairly aggressive timeline, though achievable if everything goes according to plan.

One of the challenges with satellite internet is that you need a critical mass of satellites to provide useful coverage. Too few, and you have gaps. With too many satellites but poor spacing, you have redundancy where you don't need it and gaps where you do need coverage.

The number of satellites in a constellation determines its performance characteristics. More satellites generally means better coverage and capacity, but also higher cost and more space debris risk.

Blue Origin hasn't released specific details about how many satellites TeraWave will have, orbital altitude, or performance targets. But given that they're planning to use New Glenn and potentially the super-heavy variant for deployment, we can infer they're planning for a substantial constellation.

The interesting part is how TeraWave will feed back into New Glenn utilization. Blue Origin will have a guaranteed customer for launch services: themselves. They'll need regular launches to deploy, replenish, and maintain their constellation.

This is very different from depending entirely on external customers for launch revenue. This is vertical integration.

February 2026 is a busy month for space missions, with key launches including NASA's Artemis II and SpaceX's Starship test. Estimated data.

Industry Competitive Landscape in 2026

To understand where Blue Origin stands with New Glenn in 2026, you need to see the competitive context.

SpaceX has been executing the reusable rocket strategy for years now. They have Falcon 9 (proven workhorse), Falcon Heavy (for heavy lift), and Starship in development. They have NASA contracts, military contracts, commercial contracts. They have a satellite internet business with Starlink. They're the incumbent in many ways.

United Launch Alliance (ULA) has Atlas V and Delta IV Heavy. These are expensive rockets but reliable and fully proven. ULA is developing Vulcan, which will feature reusable first stages. ULA's strength is in reliability and customer relationships, not cost cutting.

Rocket Lab has Electron, a small launch vehicle for small satellites. They're expanding with Neutron, a medium-lift vehicle. Rocket Lab's focus is on rapid launch cadence and serving the growing small satellite market.

Relativity Space is 3D printing rockets. Axiom Space is building commercial space stations. Various companies are working on different pieces of the space infrastructure puzzle.

Into this landscape comes Blue Origin with New Glenn. It's positioned as a heavy-lift workhorse that can compete with Falcon Heavy and eventually with Starship. Booster reuse means competitive pricing. Commercial customers like AST Space Mobile validate the concept.

Blue Origin's strength is financial backing (Jeff Bezos has committed significant resources), engineering talent, and willingness to invest long-term. Their challenge is that SpaceX is ahead on launch experience and has already built customer relationships.

The third New Glenn launch matters in this competitive context because it's proof that Blue Origin can execute at scale, that they can reuse hardware, and that they can maintain a launch cadence.

What Happens Next: The Roadmap Beyond February 2026

The third New Glenn launch in late February is important, but it's not the end of anything. It's a data point in an ongoing trajectory.

After the third flight, Blue Origin will almost certainly continue flying New Glenn. With a paying customer in AST Space Mobile who needs multiple launches, there will be more missions in 2026.

Meanwhile, Blue Moon Mark 1 is undergoing vacuum chamber testing at NASA's Johnson Space Center. That testing will probably take several months. Blue Origin needs to get through the testing phase, address any issues that come up, and get NASA approval.

The next launch opportunity for Blue Moon would probably be sometime in 2026 or 2027, depending on how the testing goes and when launch opportunities align.

Blue Origin is also working on Blue Ring, their orbital service vehicle. This is a different kind of capability. Blue Ring is designed to carry and deploy payloads for other companies. It's a spacecraft-as-a-service model.

And there's TeraWave. Starting deployment in late 2027 means design, manufacturing, and launch cadence planning are all happening now.

The roadmap suggests Blue Origin is playing a long game. They're not trying to win every race. They're building capabilities systematically and positioning for long-term success.

Implications for the Space Economy

When Blue Origin flies its third New Glenn with a reused booster carrying commercial satellites, what does that mean for the broader space economy?

It means launch is becoming commodity. Not in the sense that it's simple or cheap in absolute terms, but in the sense that it's reliable, repeatable, and increasingly predictable.

When something becomes commodity, it enables downstream industries. Companies can build businesses that depend on regular, affordable access to space. AST Space Mobile's satellite internet plans depend on reliable launch capacity. New space infrastructure companies depend on being able to get hardware to orbit affordably.

The space economy is limited by launch capacity and cost. As launch becomes more reliable and cheaper, the economy can grow.

This is similar to what happened with aviation. When aircraft became reliable enough for regular commercial service, the airline industry emerged. That enabled tourism, business travel, freight, etc.

We're at a similar inflection point with space. Launch is becoming reliable and affordable enough that new business models become viable. That's the significance of Blue Origin flying New Glenn regularly.

FAQ

What is Blue Origin's New Glenn rocket?

New Glenn is Blue Origin's heavy-lift orbital launch vehicle that took over a decade to develop. It can carry approximately 13 metric tons to geostationary orbit, putting it in a similar class to SpaceX's Falcon Heavy. The rocket is designed for regular commercial and scientific missions, marking Blue Origin's transition from suborbital (New Shepard) to orbital launch services.

Why did Blue Origin delay the Blue Moon lander mission?

Blue Origin postponed the Blue Moon Mark 1 lunar lander launch to conduct thorough vacuum chamber testing at NASA's Johnson Space Center in Texas. This testing validates the lander's systems in space-like conditions before sending it to the moon. Testing delays are normal in spaceflight and help prevent catastrophic failures, as the lunar surface offers no opportunity for recovery or repair missions.

What is AST Space Mobile and why is it using New Glenn?

AST Space Mobile is developing satellite-based cellular broadband that works directly with standard smartphones, providing coverage to remote and underserved areas globally. The company uses New Glenn for heavy-lift launch capacity because AST Space Mobile satellites require significant payload mass to reach their operational orbits. Blue Origin has signed a multi-launch contract with the company.

How does booster reuse improve rocket economics?

Reusing rocket boosters dramatically reduces per-launch costs by spreading design, manufacturing, and testing expenses across multiple flights instead of one. The third New Glenn launch reuses the booster from the second mission, similar to SpaceX's Falcon 9 strategy. This approach can reduce launch costs by 30-50% compared to expendable rockets, making space access more economical and enabling new business models in the space economy.

What is Blue Origin's TeraWave satellite internet constellation?

TeraWave is Blue Origin's planned satellite internet constellation announced in early 2026, with deployment starting in late 2027. This positions Blue Origin as a vertical player controlling both launch services and satellite operations, similar to SpaceX's model with Starlink and Falcon launches. The constellation will compete with existing services like Starlink and Amazon's Kuiper.

When will Blue Origin's lunar lander actually go to the moon?

Blue Moon Mark 1's launch timeline hasn't been officially set by Blue Origin, but it will likely occur sometime in 2026 or 2027 depending on vacuum chamber testing outcomes. The lander is part of NASA's lunar development program and must meet all safety and performance requirements before flight. Blue Origin is prioritizing reliability over speed to ensure successful deployment of this expensive and complex spacecraft.

How does New Glenn compare to other heavy-lift rockets?

New Glenn can lift approximately 13 metric tons to geostationary orbit, comparing favorably to SpaceX's Falcon Heavy (8.3 metric tons to GEO). SpaceX's Starship will have vastly greater capacity once operational, potentially 100+ metric tons to orbit. NASA's SLS rocket is more powerful but far more expensive per launch. New Glenn positions itself as a reliable, economical option for heavy-lift missions using reusable booster technology.

What does the third New Glenn launch mean for commercial spaceflight?

The third New Glenn launch with booster reuse demonstrates that commercial spaceflight has transitioned from experimental to operational phase. Blue Origin's ability to maintain launch cadence, recover hardware, and secure repeat commercial customers shows the industry is maturing. This reliability enables downstream space businesses and industries to build long-term plans, accelerating growth across the entire space economy.

Conclusion: The Quiet Significance of Routine Spaceflight

Blue Origin's third New Glenn launch might not grab headlines the way a lunar landing would. There's no drama here. No historic first. Just a commercial mission launching satellites to orbit using a recovered booster.

But that's exactly the point.

We've reached a moment where routinely flying rockets with reused hardware is normal. Commercial customers confidently book launch slots years in advance. Space companies are building constellations and plans that assume regular launch access.

This is the infrastructure layer of the space economy solidifying underneath all the more visible developments.

The delayed Blue Moon mission might seem like a setback, but it's actually a sign of maturity. Blue Origin is willing to delay for testing because they understand that success matters more than speed. They're playing a long game.

Meanwhile, they're building multiple pieces of infrastructure: New Glenn for launch, TeraWave for satellite internet, Blue Ring for orbital services, and Blue Moon for lunar presence. None of these are revolutionary individually, but together they represent a comprehensive vision for Blue Origin's place in the space economy.

February 2026 will be a busy month in space. Artemis II, Starship IFT-3, Crew-12, and New Glenn flying together. It might seem like just another month, but it's evidence of how far we've come.

A decade ago, having this many major space missions in a single month was unthinkable. Now it's Tuesday in the space industry.

Blue Origin's third New Glenn launch with AST Space Mobile's satellites and a recovered booster is part of that normalization. It's progress measured not in historic firsts but in operational reliability and sustained execution.

Watch February 2026. You'll see the future of spaceflight in action.

Key Takeaways

- Blue Origin's third New Glenn launch in late February 2026 will carry AST SpaceMobile satellites to orbit using a recovered booster, demonstrating operational reusability

- The delayed Blue Moon Mark 1 lunar lander is undergoing vacuum chamber testing at NASA's Johnson Space Center to ensure mission success before lunar deployment

- Booster reuse reduces launch costs by 30-50% compared to expendable rockets, enabling new commercial space business models and sustainable access to orbit

- Blue Origin is building comprehensive space infrastructure including New Glenn launches, TeraWave satellite internet, Blue Moon lunar landers, and Blue Ring orbital services

- Commercial spaceflight has transitioned from experimental phase to operational phase, evidenced by multiple major missions clustered in February 2026 alone

Related Articles

- Blue Origin's TeraWave Megaconstellation: The 6Tbps Satellite Internet Game Changer [2025]

- The Space Launch Race Heats Up: Ariane 6, India's Falcon 9 Clone, and the Future [2025]

- SpaceX IPO 2025: Why Elon Musk Wants Data Centers in Space [2025]

- Haven-1 Commercial Space Station: Assembly, Launch Timeline & Future Impact 2027

- The Search for Alien Artifacts Is Coming Into Focus [2025]

- NASA's Pandora Telescope: Finding Earth 2.0 [2025]

![Blue Origin's New Glenn Third Launch: What's Really Happening [2026]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/blue-origin-s-new-glenn-third-launch-what-s-really-happening/image-1-1769094391345.jpg)