Introduction: The Power Problem That's About to Change Everything

There's a problem brewing in every major AI data center on the planet, and nobody's really talking about it publicly. Not because it's secret, but because the solution seemed impossible until very recently.

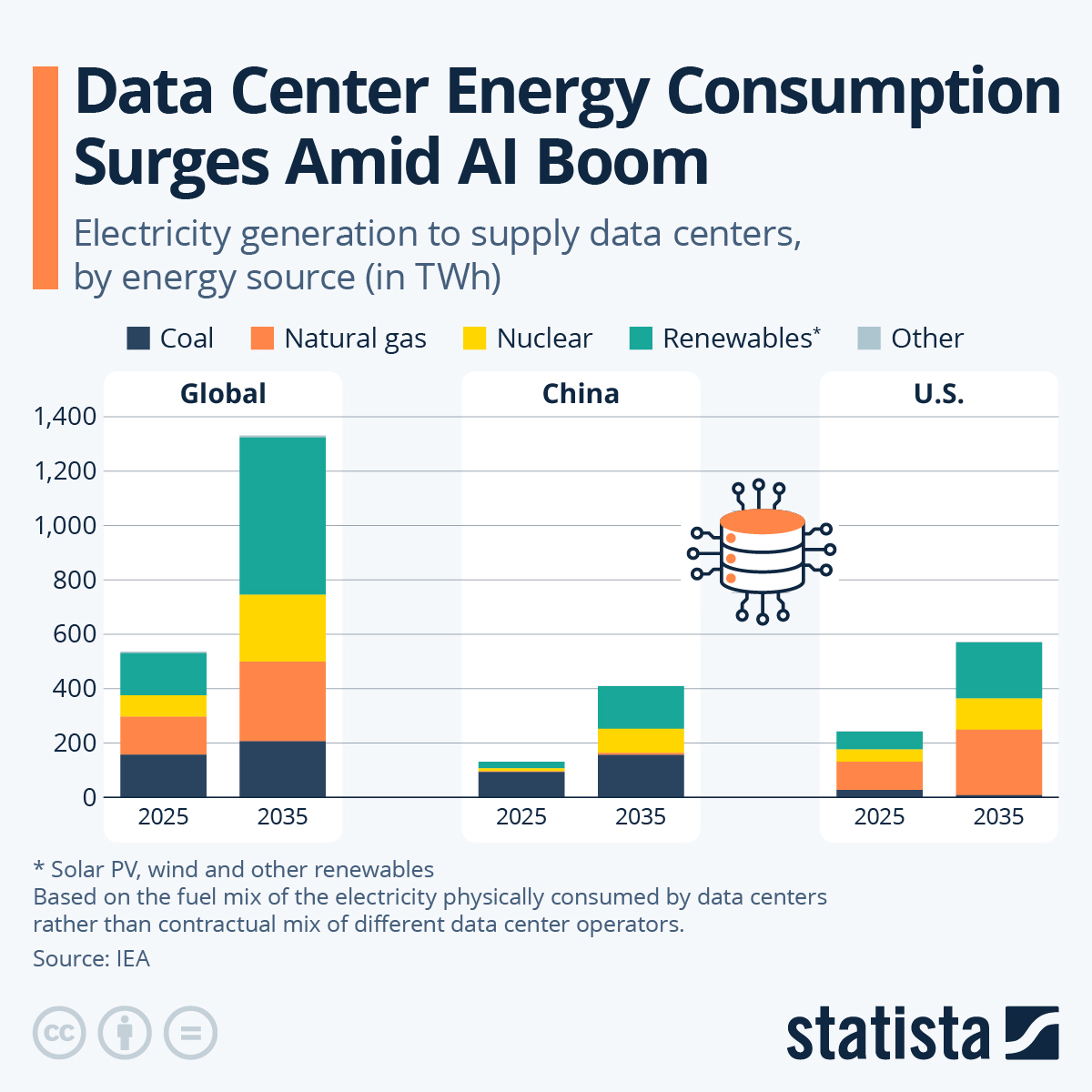

Nvidia dominates the AI chip market with over 90% market share, and their GPUs are genuinely impressive. But here's the uncomfortable truth: they're becoming victims of their own success. As AI models grow larger and more complex, the power consumption at hyperscale data centers is becoming unsustainable. We're talking about facilities that consume as much electricity as small cities, with cooling systems that cost millions of dollars to operate annually.

The fundamental physics problem is this: traditional silicon-based processors rely on electrons flowing through transistors to perform calculations. Electrons generate heat. Heat requires cooling. Cooling requires energy. It's a vicious cycle that's hitting hard limits as we scale up model inference workloads.

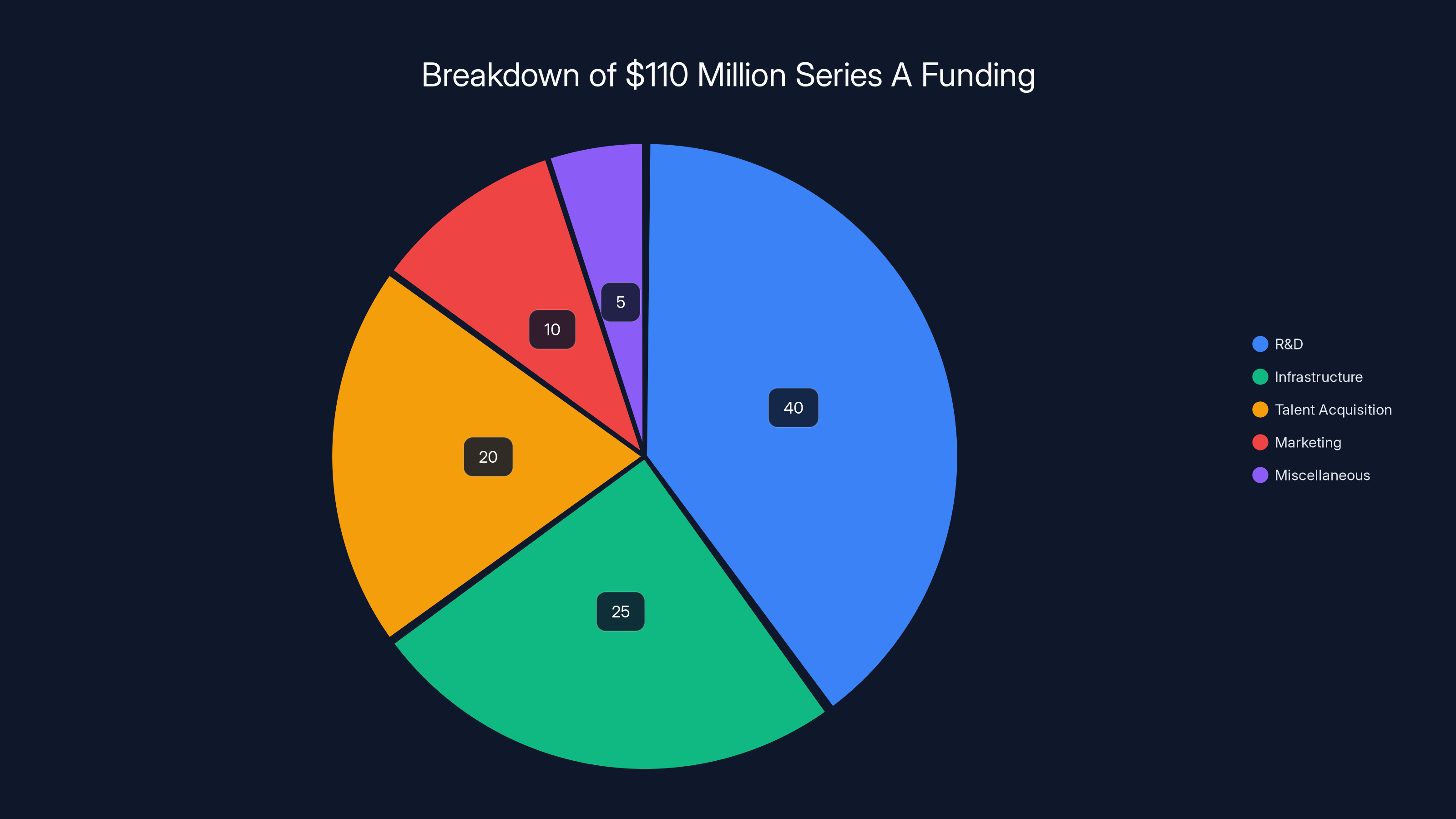

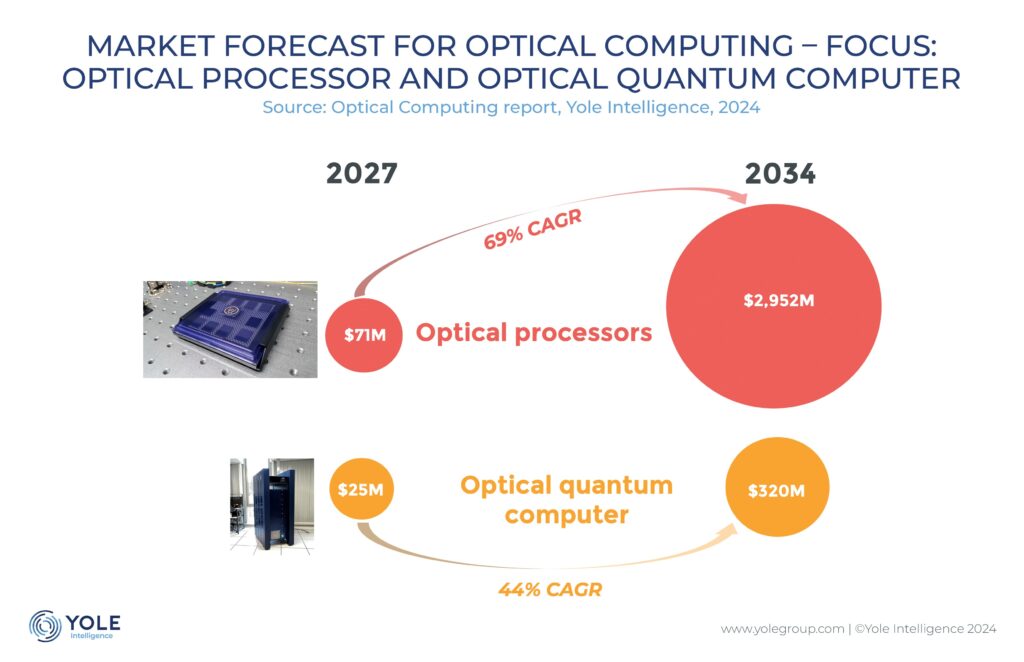

Enter Neurophos, an Austin-based startup that just raised $110 million in Series A funding to pursue a completely different approach to the problem. Instead of pushing silicon further down the road of miniaturization and incremental improvement, they're switching the medium entirely: from electrons to photons.

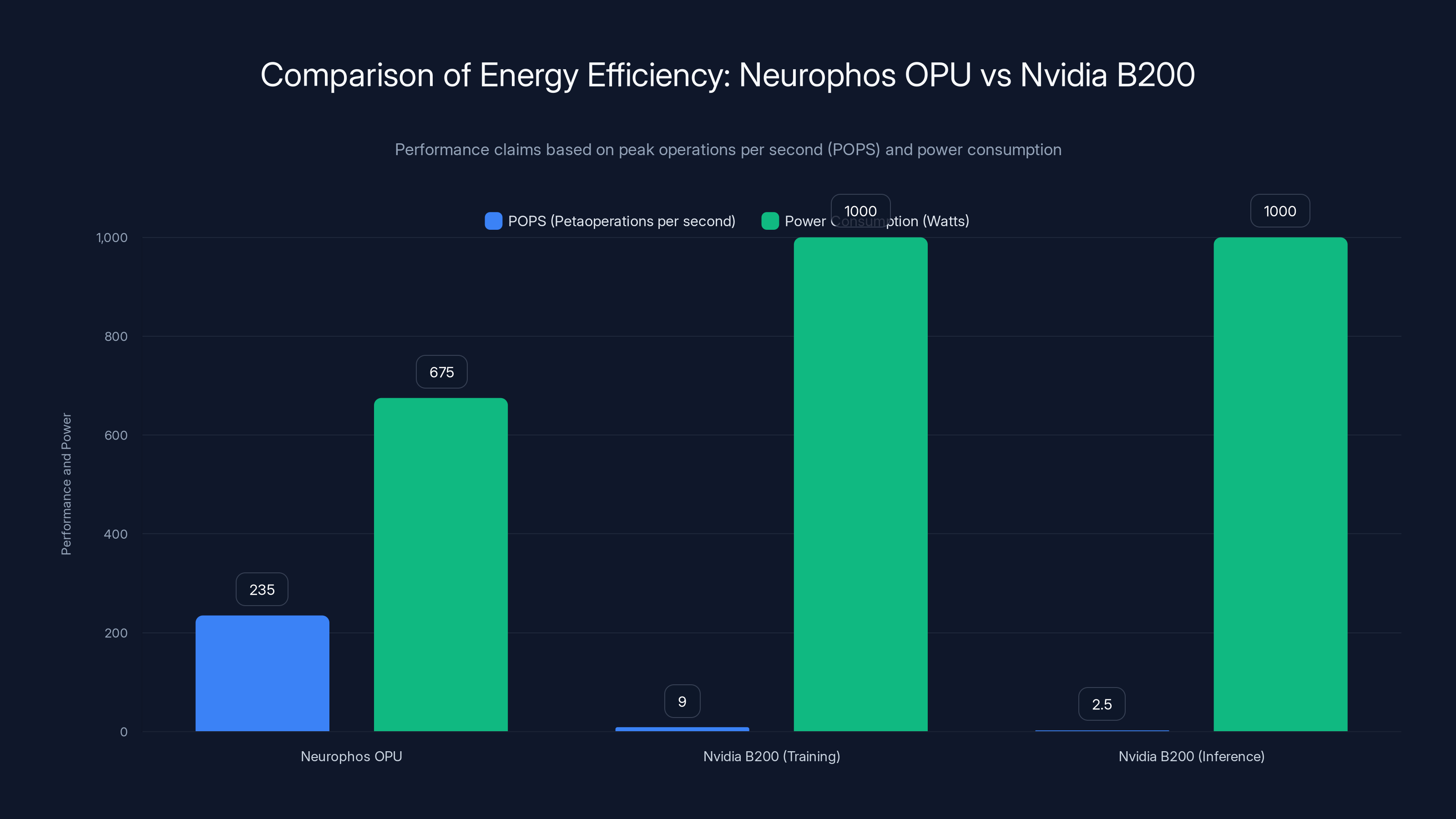

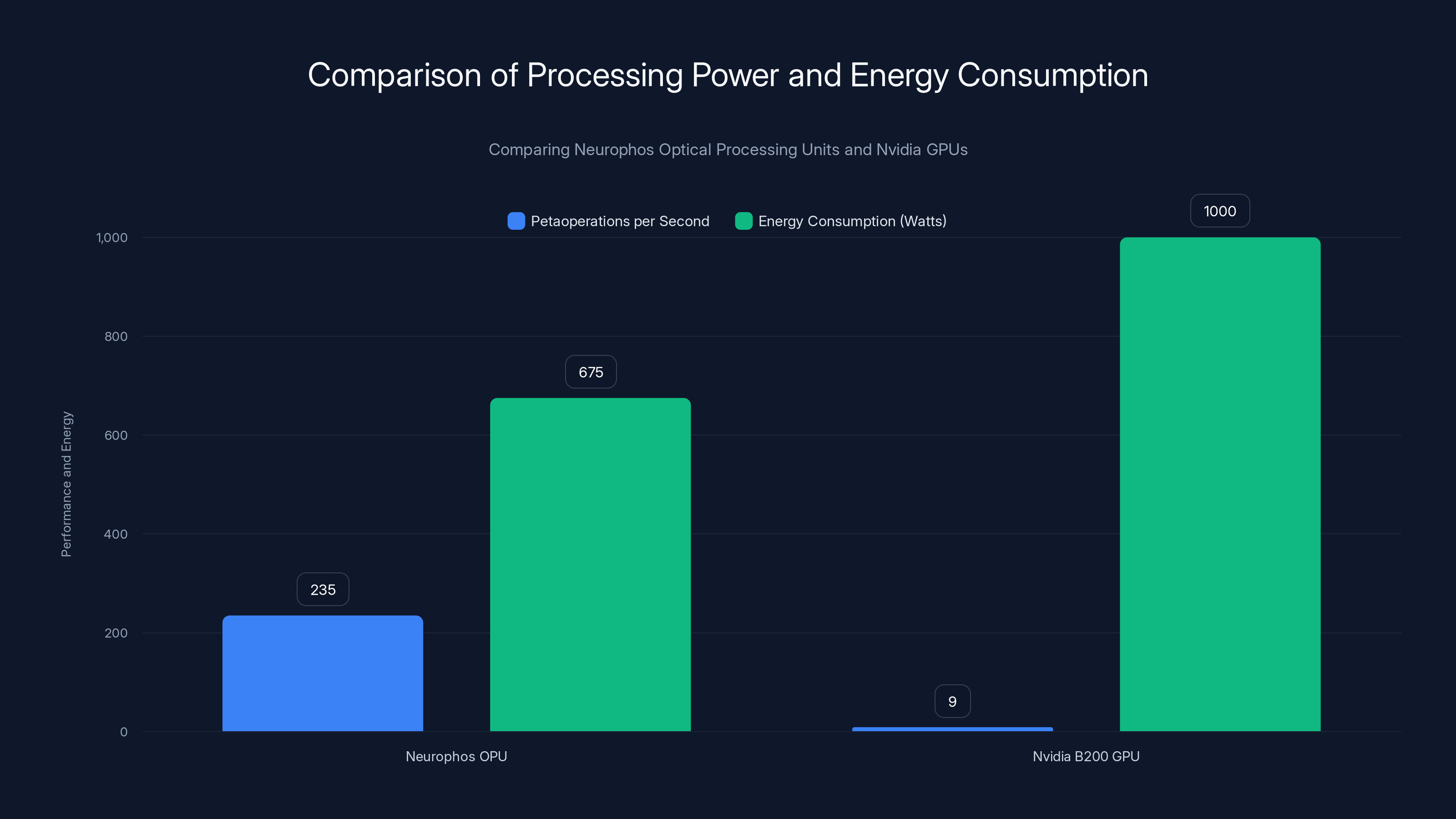

The company's bet is audacious but grounded in real physics. By using optical components called metasurface modulators, Neurophos claims their optical processing units can deliver 235 petaoperations per second while consuming just 675 watts. For context, Nvidia's flagship B200 GPU delivers around 9 petaoperations per second at 1,000 watts. That's not just a marginal improvement. That's a fundamental shift in what's possible.

But this isn't science fiction. The technology traces back to real research conducted by Duke University professor David R. Smith, who famously used metamaterials to create an invisibility cloak for microwave frequencies. Twenty years later, that academic work is being translated into something far more pragmatic and commercially viable: processors that could reshape the entire data center infrastructure supporting the AI revolution.

The funding round tells you everything you need to know about how seriously the market is taking this. Gates Frontier, Bill Gates' venture vehicle, led the round. Microsoft's corporate VC arm participated. So did Saudi Aramco Ventures, Bosch, and a roster of other institutional players betting on the future of computing infrastructure. This isn't a bet on a single application or a speculative technology. This is major institutional capital saying: optical computing for AI is the future.

Here's what's at stake, and why Neurophos' technology matters more than a typical "new chip company" story.

Understanding the AI Power Crisis: Why Current Solutions Are Reaching Their Limits

The AI industry is facing a constraint that most people don't realize is approaching critical mass. It's not a software problem. It's not an algorithmic problem. It's a pure physics problem that Silicon Valley's iterative approach to chip design simply can't solve anymore.

Let's start with the basics. Training and running large language models requires performing matrix multiplication operations at massive scale. A single inference pass through GPT-4 or Claude involves billions of these calculations. When you're running millions of inference requests per day across thousands of GPUs, the math becomes staggering.

Nvidia's H100 and B200 GPUs have dominated this space because they're optimized specifically for these matrix operations. But optimization within the silicon paradigm has clear physical limits. The fundamental bottleneck isn't the speed of individual transistors anymore. It's the energy required to move electrical signals around the chip and dissipate the heat those signals generate.

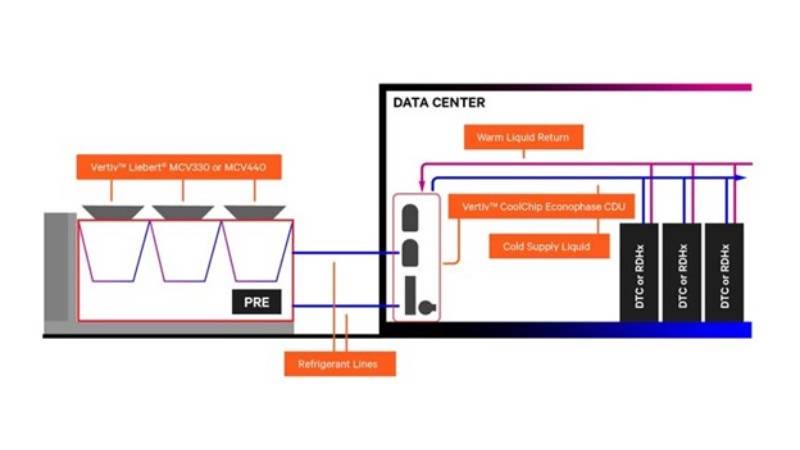

Consider the cooling infrastructure required to support a modern AI data center. A single large facility might have hundreds of thousands of GPUs running continuously. Each GPU dissipates hundreds of watts. You need water cooling, redundant cooling systems, backup power systems, facilities designed from the ground up to handle this thermal load. The operational cost of cooling at scale can rival the cost of the hardware itself.

There's also the physics of electron movement itself. As transistors get smaller (we're now at 3-nanometer sizes), electrons start exhibiting quantum effects that make them harder to control and more prone to leakage. Heat becomes increasingly difficult to manage. Power density becomes a constraint that no amount of clever engineering can fully overcome.

Major hyperscalers have started experimenting with different cooling approaches. Some are using liquid cooling. Others are exploring immersion cooling or even putting data centers in cold climates. But these are all band-aids on a fundamental problem: the electron-based approach has diminishing returns.

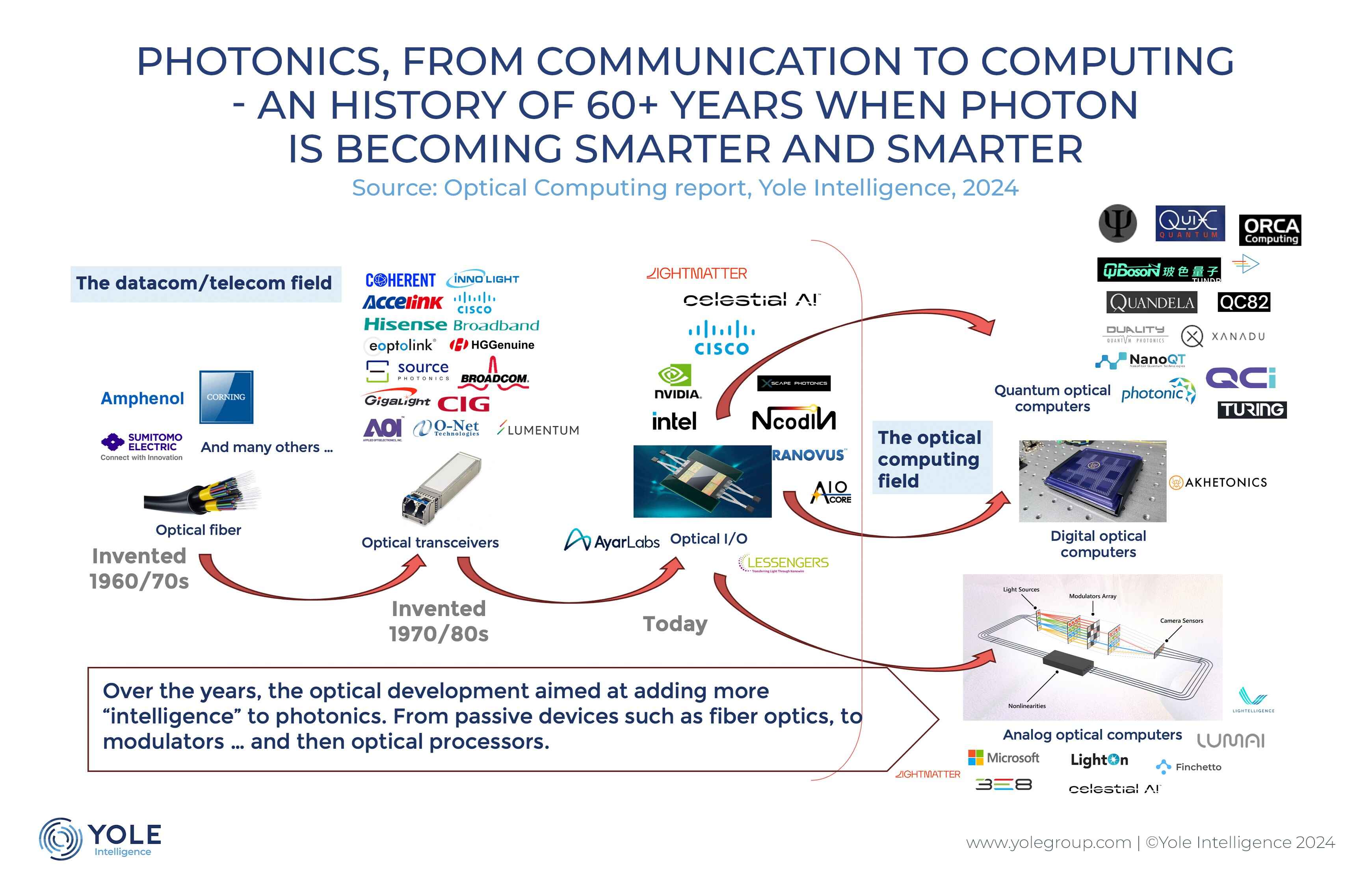

This is where the photonic approach becomes interesting. Light (photons) has very different properties from electrons. Photons travel at the speed of light by definition. They generate negligible heat. They're not susceptible to electromagnetic interference. They can be packed much more densely in optical fiber and waveguides. From a pure physics standpoint, optical computing has always been the theoretically superior approach to electronic computing.

The problem wasn't the physics. It was implementation. Optical components have traditionally been large, difficult to manufacture, and required expensive converters to transform data between electrical and optical domains. Those converters themselves consume significant power and introduce latency. The overhead of optical systems has historically outweighed their theoretical advantages.

Neurophos is betting that metasurface technology solves this implementation problem in a way that previous approaches couldn't.

Neurophos OPU claims to deliver 26x more operations than Nvidia B200 in training, while consuming 33% less power. However, real-world performance may vary due to different workload conditions.

What Are Metasurface Modulators and Why They're Different

This is where the technology gets genuinely interesting, and where Duke University's invisibility cloak research becomes relevant to data center infrastructure.

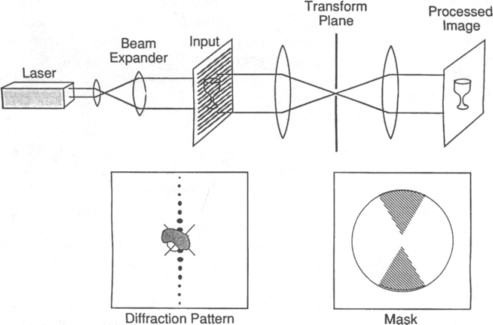

Metamaterials are engineered composite materials designed to have properties not found in nature. David R. Smith's famous work demonstrated that by arranging these materials in specific patterns, you could bend light in ways that seemed impossible according to conventional understanding. His invisibility cloak worked for microwave frequencies, but the principle was profound: the arrangement and composition of material fundamentally determines how it interacts with electromagnetic radiation.

Neurophos has taken this research and applied it to a different problem: creating optical modulators that are dramatically smaller and more efficient than traditional optical components.

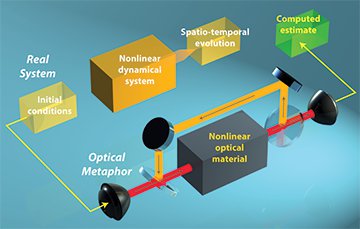

A metasurface modulator is essentially a thin layer of engineered material that can control light with extraordinary precision. Traditional optical modulators work by physically moving components or changing the properties of crystals to alter light paths. These are bulky and power-hungry. Metasurface modulators work differently.

Instead of moving physical components, the metasurface uses its engineered structure to modify how light behaves as it passes through. By controlling the electric field applied to the metasurface, you can change how light propagates, essentially using the material itself as the computing element.

Here's why this matters for AI chips: matrix multiplication can be performed optically. If you encode numbers as the intensity or phase of light beams, and pass those beams through specially designed optical structures, the mathematical operations happen in the optical domain. No electronic transistors needed. No heat generation from electron movement. Just photons doing physics.

Neurophos claims its metasurface modulators are about 10,000 times smaller than traditional optical transistors. This size reduction is critical. If you can fit thousands of these modulators on a single chip, you can perform thousands of parallel optical calculations simultaneously.

But here's the clever part that makes this commercially viable: Neurophos says it can manufacture these chips using standard silicon foundry processes and materials. You don't need exotic equipment or completely new manufacturing infrastructure. You can use the same fabs that produce traditional silicon chips.

This is crucial for feasibility. If Neurophos required entirely new manufacturing plants and processes, the technology would likely remain academic. Instead, the company is saying: take existing manufacturing infrastructure, apply our metasurface designs to it, and you get optical computing in production timelines.

The optical processing unit Neurophos is developing doesn't eliminate the need for electronic components entirely. You still need electronic interfaces to convert input data from digital to optical formats, and output data from optical back to digital. But Neurophos is designing its architecture so that the vast majority of computation happens in the optical domain, where the efficiency gains are most significant.

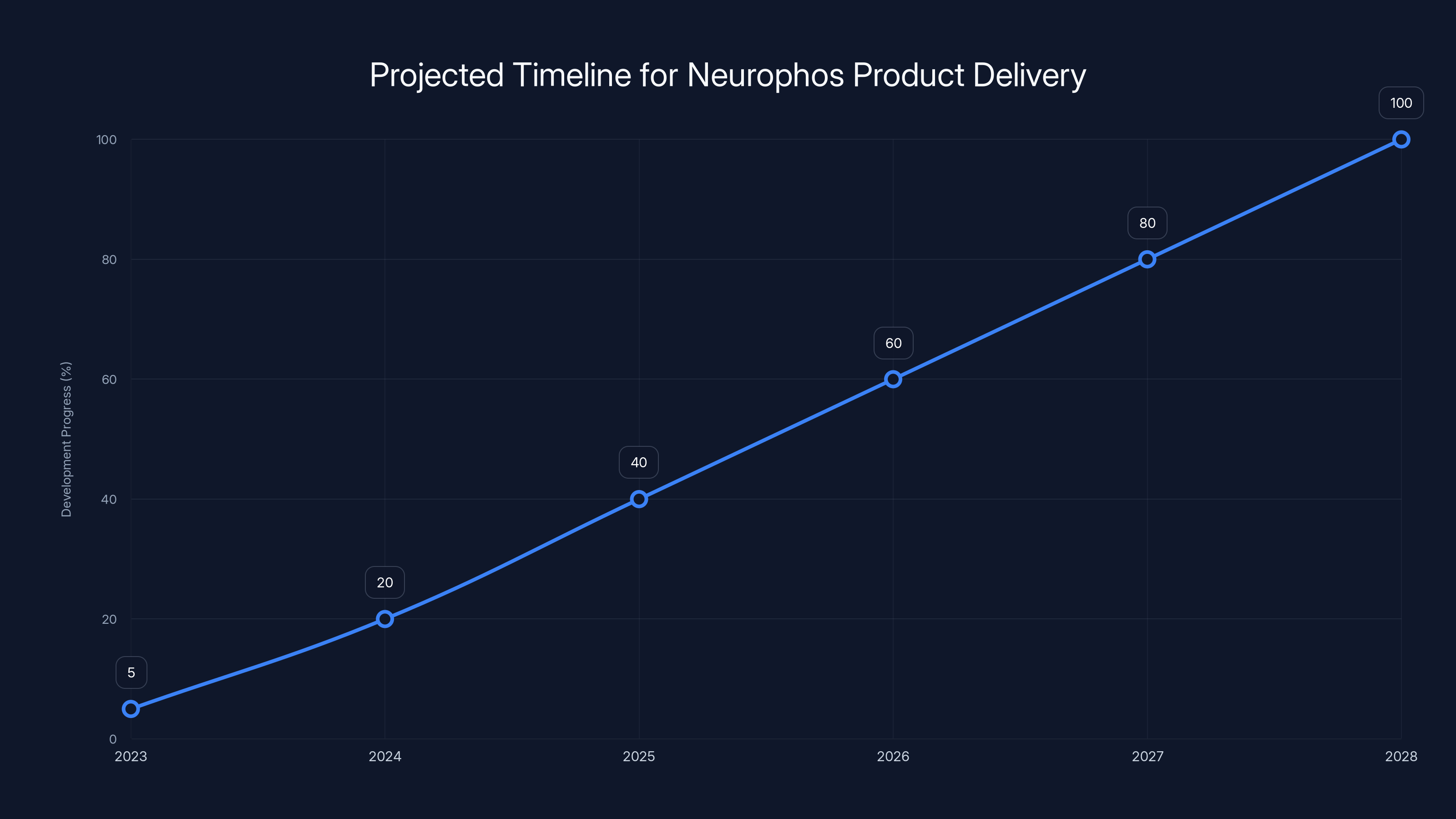

Neurophos aims for product delivery by mid-2028, with incremental progress in development phases. Estimated data based on typical industry timelines.

The Neurophos Optical Processing Unit: Architecture and Design

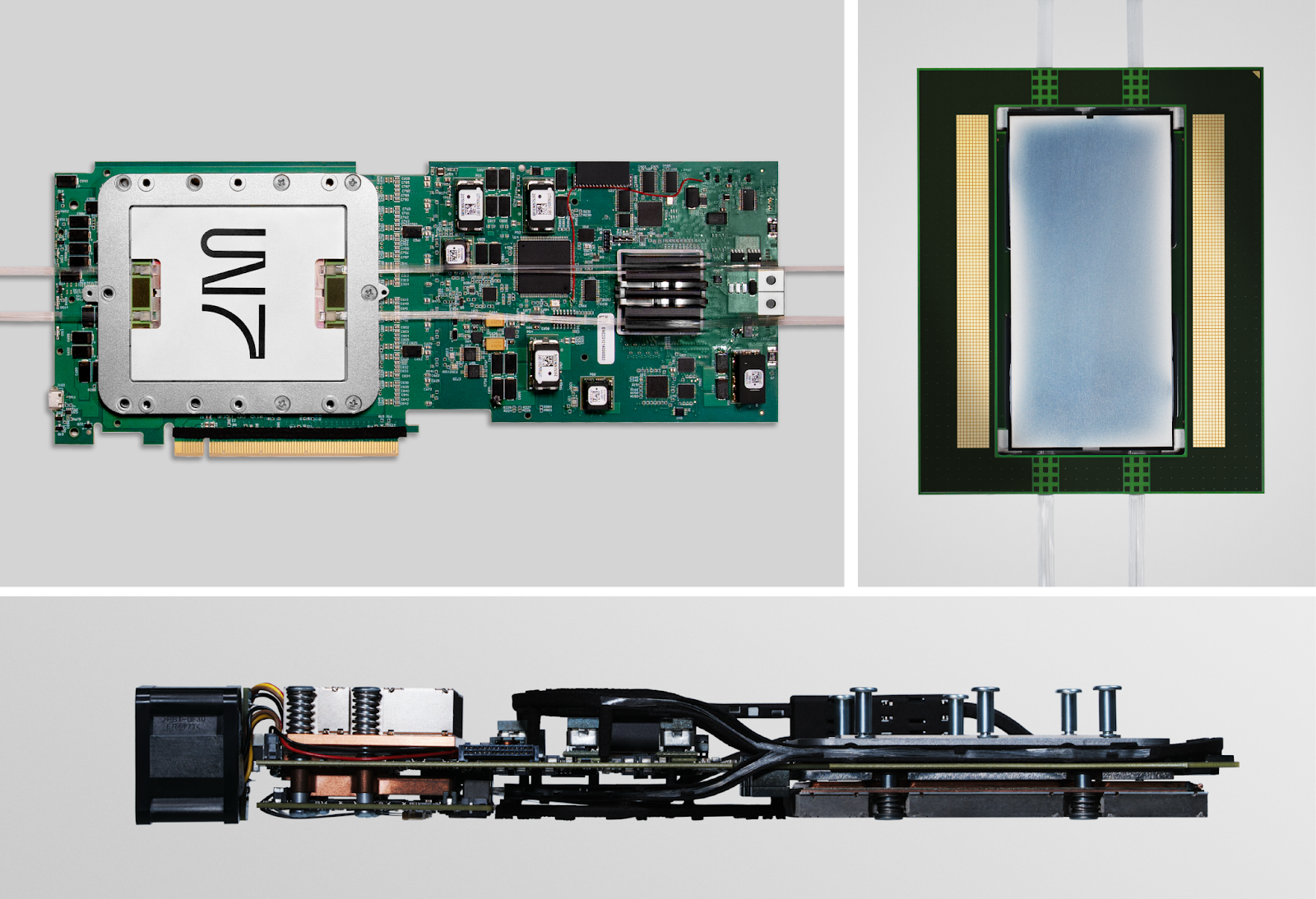

The OPU (Optical Processing Unit) that Neurophos is building isn't a direct replacement for a GPU in the way you might swap out one chip for another. It's more fundamentally different than that.

A GPU is fundamentally an electronic processor. It has transistors, gates, memory, caches. These are all electronic components arranged in complex patterns. The Neurophos OPU, by contrast, is architected differently from the ground up.

The core processing happens in the optical domain. Information enters as optical signals. Matrix multiplication happens through the propagation of light through metasurface modulators. The results emerge as optical signals that are then converted back to electronic format for downstream processing or communication.

This architecture has several important implications. First, the optical computation is inherently parallel. Light doesn't have the sequential bottlenecks that electronic systems face. Different beams of light can carry different computations simultaneously, all passing through the same optical hardware without interference.

Second, the power consumption profile is completely different. Traditional GPUs consume power continuously as electrons move through circuits. Optical systems consume power only when converting between electrical and optical domains. The actual computation uses photons, which don't dissipate energy the way moving electrons do.

Third, the thermal characteristics are dramatically different. Electronic processors generate heat proportional to their power consumption. Optical processors generate minimal heat during the actual computation phase. This has cascading benefits: you need less cooling, less facility design focused on thermal management, lower operational costs.

The target specifications are ambitious. Neurophos claims the OPU can operate at 56 GHz frequency, reaching 235 petaoperations per second while consuming 675 watts. For inference workloads, the company claims this represents approximately 50 times the energy efficiency of Nvidia's Blackwell architecture.

To put that in perspective, if a hyperscaler currently runs a million inference requests per day using Nvidia GPUs, they're spending a certain amount on electricity, cooling, facility overhead, and hardware amortization. If they could do the same workload with 50 times better efficiency, they'd reduce their costs by roughly 50% (accounting for hardware costs that don't scale linearly with energy). For a large hyperscaler, that's billions of dollars annually.

The software stack is equally important. Neurophos isn't just building hardware in isolation. The company is developing a complete software ecosystem that allows developers to work with the OPU without needing to understand the underlying optical mechanics. The goal is for the OPU to integrate into existing AI frameworks like PyTorch and TensorFlow, with compilation tools that automatically optimize code for optical execution.

This is critical for adoption. Even if the hardware is technically superior, if developers have to completely rewrite their code to use it, adoption will be slow. Neurophos is taking the approach of making the OPU as transparent as possible, with software abstractions that handle the complexity automatically.

Series A Funding: What $110 Million Really Signals

Funding rounds are signals. They tell you who believes in a technology and how much they're willing to bet on it. The Neurophos Series A is a particularly interesting signal.

Gates Frontier, Bill Gates' venture firm, led the round. This matters because Gates Frontier focuses on climate-related technologies and global development. The investment signals that major institutional players view optical AI computing not just as a commercial opportunity, but as a potential solution to real environmental problems. The energy efficiency gains from optical processors could meaningfully reduce the carbon footprint of AI computation globally.

Microsoft's participation through M12 (their corporate VC arm) is equally significant. Microsoft is building Copilot infrastructure, running massive amounts of inference at scale through their Azure cloud platform, and integrating AI features into Windows and Office. They have direct visibility into the energy costs and infrastructure challenges of operating at that scale. Their decision to invest suggests they see the Neurophos approach as viable and worth exploring.

Aramco Ventures' participation is interesting for a different reason. Saudi Aramco is investing in future energy infrastructure and technology. They likely see optical computing as part of a broader shift in how computing infrastructure works, with energy efficiency being a fundamental driver.

The $110 million valuation implicitly places Neurophos in a specific category. This is pre-revenue funding (the company doesn't plan to ship production chips until 2028), yet it's raising at valuations typically reserved for companies with proven technology and strong revenue trajectories. This tells you investors believe in the core technology and the team's ability to execute.

But let's be clear about what this funding covers and what it doesn't cover. The $110 million is earmarked for:

Developing the first integrated photonic compute system - This is the hardware engineering and physical prototype development.

Building a complete software stack - This includes compilers, optimization tools, and frameworks for making the hardware usable by developers.

Creating datacenter-ready modules - Not just lab prototypes, but systems actually designed to integrate into operational data centers.

Developing early-access developer hardware - The company is planning to get hardware into the hands of early partners before mass production, allowing them to write real software against real hardware.

This is a substantial engineering effort. Optical systems are fundamentally different from electronic systems. Getting a complex optical processor from prototype to production involves solving manufacturing challenges, reliability challenges, integration challenges, and support infrastructure challenges.

The $110 million sets Neurophos up for a 3-4 year runway at a well-funded startup burn rate. The company is deliberately planning to ship production chips by mid-2028. That timeline is realistic for a hardware company but aggressive for one developing fundamentally new manufacturing processes. Missing that timeline wouldn't necessarily doom the company, but hitting it would be a major validation point.

Neurophos's optical processing units deliver significantly higher processing power at lower energy consumption compared to Nvidia's B200 GPU. Estimated data based on current technology claims.

The Competitive Landscape: Nvidia, Lightmatter, and the Optical Computing Opportunity

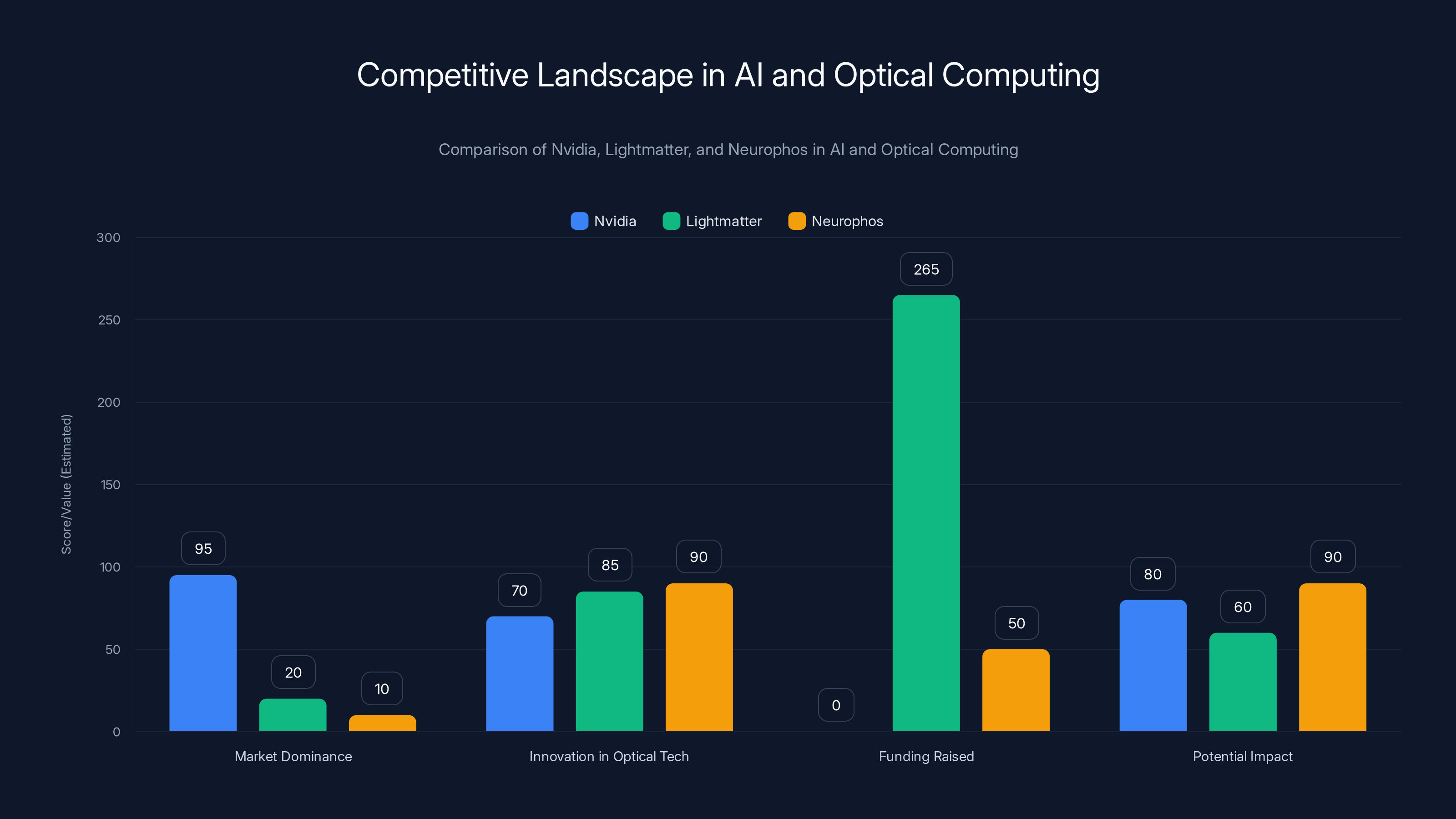

Nvidia's dominance in AI chips is almost total. Their GPU architecture became the de facto standard for AI workloads almost by accident. GPUs were originally designed for graphics processing, which requires massive parallelism and heavy matrix multiplication. When researchers realized that the same hardware excels at training neural networks, Nvidia had a five-year head start on competitors. That lead has only widened.

But dominance isn't invulnerability. If optical computing actually delivers on its efficiency promises, and if developers can actually use that hardware without completely rewriting their code, the competitive dynamics shift. Nvidia understands this, which is why they've begun investing in optical interconnect technology themselves.

Lightmatter, another photonics startup, raised substantial funding ($265 million as of 2024) with a similar vision. But Lightmatter has been pursuing interconnects as the primary use case—essentially using optical technology to improve how data moves between chips and within systems. That's a valuable problem to solve, but it's less fundamental than replacing the processors themselves.

Neurophos is pursuing the more ambitious path: optical processors that do the actual computation, not just the interconnects. This is harder technically but potentially more impactful commercially.

There are other optical computing efforts scattered throughout academia and industry, but most remain at the research stage. The challenges are real:

- Integration complexity: Optical and electronic components need to work together seamlessly.

- Manufacturing maturity: Optical components are less standardized and harder to mass-produce than silicon.

- Software ecosystem: Most AI frameworks assume electronic processors with specific architectures. Retrofitting them for optical processors is non-trivial.

- Latency: Converting between electrical and optical domains introduces latency that can offset efficiency gains if not managed carefully.

- Reliability and serviceability: Optical systems have different failure modes than electronic systems.

Nvidia isn't standing still, of course. The company's architecture has evolved continuously, with new versions improving energy efficiency incrementally. But Neurophos CEO Patrick Bowen makes an important point: silicon improvements follow Moore's Law, which has slowed. Nvidia might achieve 15-20% efficiency improvements with each new node, taking 18-24 months. Neurophos claims a 50x advantage out of the gate, which would take Nvidia decades of incremental improvement to match (if they could at all within the silicon paradigm).

The reality is that the optical computing space is genuinely interesting because the addressable market is enormous. If Neurophos can deliver even half of what they're claiming, the market opportunity is in the tens of billions of dollars. That's enough to support multiple successful companies and genuinely disrupt the current Nvidia-dominated landscape.

Manufacturing and Scale: The Real Challenge Ahead

Here's where the rubber meets the road, and where many promising semiconductor startups have stumbled: manufacturing at scale.

Neurophos has made specific claims about manufacturing feasibility. They say the metasurface modulators can be produced using standard silicon foundry processes and materials. No exotic equipment. No new fabs required. Just applying their designs to existing infrastructure.

If that's true, it's a game-changer. If it's not, the company faces a much longer path to commercialization.

The semiconductor industry has decades of accumulated knowledge about manufacturing silicon chips at scale. TSMC, Samsung, and Intel run some of the most complex manufacturing operations on the planet, with fab facilities costing $15-25 billion each. Those fabs can produce millions of chips per month once optimized.

Optical components are fundamentally different. You're working with materials that interact with light in specific ways. You need to control structures at scales smaller than the wavelength of light. You need precision that's often harder to achieve than traditional silicon lithography.

Neurophos' claim about using standard silicon foundry processes suggests they've designed their metasurfaces to work within the constraints of existing manufacturing. This would be a significant achievement, but it needs independent validation. The company hasn't made their designs public, so we can't verify whether the manufacturing claims are realistic.

Assuming the manufacturing works as claimed, scaling from prototype to production still involves substantial work. You need to qualify the manufacturing process with a foundry partner. You need to establish supply chains. You need to build quality assurance processes for a completely new type of component. You need to train technicians and engineers who understand both the optical properties and the manufacturing requirements.

This is why Neurophos is planning multiple facilities and partnerships. The company will likely need to work with multiple foundries to achieve the production volumes required by hyperscalers. Getting from one fab producing test quantities to multiple fabs producing millions of units requires solving many non-obvious engineering and logistical challenges.

There's also the question of yield. In semiconductor manufacturing, yield refers to the percentage of chips that come out of the fab fully functional. A yield of 70% is pretty good. Anything below 50% makes a process uneconomical. With optical components, achieving good yields on a new process is particularly challenging because the optical properties are sensitive to subtle manufacturing variations.

If Neurophos' metasurfaces have tight manufacturing tolerances, yields could be a limiting factor. The company would need to either perfect their manufacturing process to achieve good yields, or accept higher defect rates and higher costs per chip.

None of this is impossible. But it's the gap between a promising prototype and actual commercial production. This is why the company's timeline to ship in 2028 is aggressive. They're essentially saying: in the next three years, we'll finish hardware design, qualify manufacturing, work with partners to establish production capacity, and prepare for commercial shipments. That's a lot of work for a company that's currently focused on development.

Estimated data: Majority of the $110 million Series A funding is allocated to R&D, highlighting the focus on developing optical AI computing technology.

The Software Stack: Making Optical Processors Practical for Developers

You can build the most efficient processor on the planet, but if nobody can use it, it's worthless. This is why Neurophos' software strategy is almost as important as the hardware.

Most AI development today happens through frameworks like PyTorch (developed by Meta) and TensorFlow (developed by Google). These frameworks abstract away the underlying hardware, allowing developers to write code that can run on GPUs, TPUs, or other accelerators without fundamentally rewriting everything.

Neurophos is building a compiler and runtime infrastructure that allows PyTorch and TensorFlow code to run on their optical processors. The goal is to make the OPU appear as another accelerator option, similar to how you can currently choose between running on CPU, GPU, or TPU.

This is harder than it sounds. The fundamental computation models are different. GPUs are fundamentally electronic processors with specific architectural characteristics. Optical processors have completely different performance profiles, memory hierarchies, and computational patterns.

The compiler needs to:

- Analyze the computation graph - Understand what operations the neural network is performing

- Identify optical-friendly operations - Determine which parts of the graph can run efficiently in the optical domain

- Generate optimal optical routines - Convert the computation into sequences of optical operations

- Handle electro-optical conversion - Manage the boundaries between electrical and optical domains

- Optimize for the specific hardware - Tune the code for the particular OPU configuration

- Maintain numerical accuracy - Ensure that optical computation produces results equivalent to electronic computation

This is a massive software engineering effort. Neurophos is likely recruiting experienced compiler engineers and has probably partnered with universities or other research institutions for foundational compiler research.

Beyond the compiler, the company needs to build debugging tools, profiling tools, and documentation. When things go wrong—and they will—developers need ways to understand what's happening in the optical domain and fix their code. Traditional GPU profiling tools won't work. New tools need to be built from scratch.

Neurophos is likely planning a tiered software strategy. Early access partners (probably companies like Microsoft, OpenAI, Anthropic) will get direct access to the hardware and lower-level APIs. They'll help identify bugs, performance issues, and missing features. Once the software stabilizes, the company will release more complete frameworks and documentation for broader adoption.

The company is also planning developer hardware through their early-access program. This serves multiple purposes: it lets developers experiment with the hardware before production, identifies software issues early, and builds community and momentum for when the product launches commercially.

Energy Efficiency Claims: Separating Theory from Reality

Let's dig into the specific performance claims, because they're where skepticism is warranted.

Neurophos claims their OPU can deliver 235 POPS (petaoperations per second) at 675 watts, compared to Nvidia's B200 delivering approximately 9 POPS at 1,000 watts.

The ratio looks extraordinary: 235 POPS / 9 POPS = 26x more operations, consuming 33% less power. That's not just better. That's world-changing.

But let's think carefully about these numbers. "POPS" is peak operations, measured under ideal conditions. In real-world inference workloads, peak performance is rarely achieved. Networks have sequences of operations that don't map cleanly to peak performance. Memory access patterns create bottlenecks. Latency costs accumulate.

Further, the B200's peak specifications are measured in training scenarios with massive batch sizes. For inference—which is what hyperscalers care about most—the performance profile is different. Single-request latency matters more than throughput. The B200 might achieve 9 POPS in training; in inference it might achieve 2-3 POPS depending on batch size.

Neurophos' claims are also measured under assumptions about how the optical processor would actually be used. If you can't saturate the processor with inference requests, those peak numbers become academic.

That said, the theoretical advantages of optical processing are real. Photons truly do generate less heat than moving electrons. The speed of light is fundamentally fast. If you can actually build a processor that does meaningful computation in the optical domain, the efficiency advantages should be substantial.

The question isn't whether optical computing can be efficient in theory. The question is whether Neurophos' specific metasurface approach can deliver that efficiency in practice, at scale, with acceptable numerical accuracy.

This is why third-party validation will be critical. Once Neurophos delivers developer hardware, independent researchers and engineers at tech companies will be able to benchmark the actual performance. That's when the real story emerges.

It's also worth noting that Neurophos is comparing itself to the B200 (Blackwell architecture). But the semiconductor industry doesn't stand still. By the time Neurophos ships in 2028, Nvidia will likely have released newer architectures. The comparison window shrinks with time. Neurophos would need to maintain a performance advantage across multiple generations of competition to justify its market position.

Nvidia leads in market dominance with its established AI chip technology, while Lightmatter and Neurophos are strong in optical innovation. Lightmatter has raised significant funding, but Neurophos is seen as having higher potential impact due to its focus on optical processors. (Estimated data)

Customer Interest and Early Adoption Signals

Neurophos CEO Patrick Bowen has stated that the company has already signed multiple customers, though he hasn't disclosed them. This is a significant claim that suggests real interest beyond theoretical possibilities.

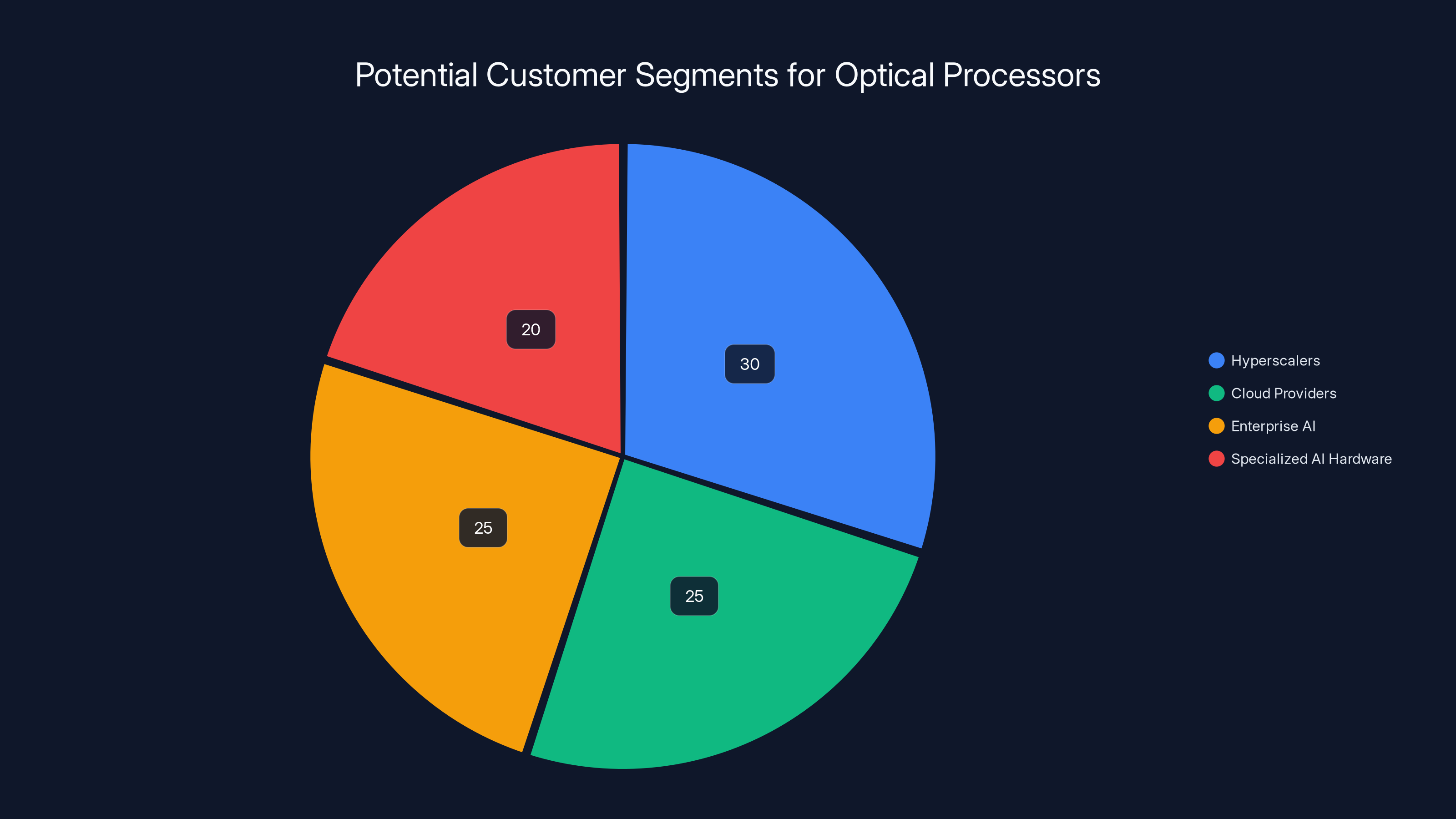

Think about who would be interested in optical processors for AI inference:

Hyperscalers like Microsoft, Google, Meta - These companies operate massive data centers running billions of inference requests daily. Energy efficiency directly translates to cost savings measured in hundreds of millions annually. If optical processors truly deliver better energy efficiency, they'd be high-value customers.

Cloud providers like AWS, Azure, Google Cloud - Similar logic. Lower operational costs mean they can offer better pricing or higher margins to customers.

Enterprise AI deployments - Companies deploying AI at scale in their own data centers (rather than using cloud providers) face similar cost pressures.

Specialized AI hardware providers - Companies like NVIDIA might even be interested in using optical processors as complementary technology, incorporating them into broader accelerator lineups.

The fact that multiple customers have reportedly signed on suggests either: (a) the technology has been vetted by serious companies who believe in its feasibility, or (b) customers are hedging their bets by exploring alternatives to sole reliance on Nvidia.

Microsoft's stated interest in looking "very closely" at the technology is noteworthy. Microsoft has the capital, the data center infrastructure, and the motivation to experiment with novel chip architectures. Their interest suggests the technology passes basic credibility tests with sophisticated engineers.

But signed customers and interest don't guarantee success. Many promising startups have had significant customer interest, only to encounter manufacturing challenges, performance shortfalls, or market shifts that prevented commercial viability. The real test comes when actual hardware starts shipping and performance claims meet reality.

The Path to 2028: What Needs to Happen for Success

Neurophos is targeting mid-2028 for the first commercial shipments. This timeline implies a specific sequence of milestones that need to be hit:

2026: Hardware engineering and manufacturing qualification - The company needs to move from concept and prototypes to production-ready designs. This involves iterating on the optical processor design, validating it with early partners, and working with manufacturing partners to establish production processes.

2027: Small-scale production and early deployments - The company likely needs to produce limited quantities of hardware for early customers to test in real data center environments. This involves scaling the manufacturing process, solving reliability and quality issues, and gathering real-world performance data.

Mid-2028: Commercial availability - The company would begin selling production units, with software support, warranties, and technical support infrastructure in place.

Missing any of these milestones by significant amounts makes 2028 harder to hit. Semiconductor development is notoriously difficult to schedule because problems that seem simple can hide substantial complexity.

There are also market-timing considerations. AI inference demand in 2028 will likely be different from today. If the pace of AI adoption slows, or if other innovations reduce the demand for inference acceleration, the market opportunity could be smaller. Conversely, if AI adoption accelerates and hyperscalers become even more focused on energy efficiency, the market could be larger.

Neurophos also needs to consider competitive responses. Nvidia won't stay still. By 2028, they'll likely have released multiple new architectures. They might incorporate optical interconnects or even optical components. They might release entirely new product lines targeting efficiency rather than pure performance. Neurophos' advantage window is probably time-limited.

The company also needs to execute flawlessly on the software side. Hardware advantages mean nothing if nobody can actually use the hardware effectively. Building a software ecosystem that makes optical processors transparent to developers is a multi-year effort.

Estimated data suggests that hyperscalers and cloud providers are the largest segments interested in optical processors, driven by potential cost savings and energy efficiency.

Broader Implications for the AI Hardware Landscape

Neurophos' existence and funding matter beyond just whether they personally succeed. The technology signals something important about where the AI computing infrastructure landscape is heading.

The current paradigm—dominated by Nvidia, built on silicon GPUs—became dominant because it was the best available solution for the problem at a specific time. But dominance doesn't mean it's optimal or eternal. The energy efficiency crisis is real, and it's going to force rethinking of how we build AI compute infrastructure.

Optical computing is one answer to that rethinking. But it might not be the only one. Other startups are pursuing different approaches:

Neuromorphic chips - Companies like Intel and Cerebras are building chips that mimic how brains process information, potentially offering better efficiency for certain workloads.

FPGA-based accelerators - Field-programmable gate arrays offer flexibility and can be optimized for specific workloads, though they're more complex to program.

Analog processors - Some research is exploring processors that use analog computation directly rather than digital computation, potentially reducing power requirements.

Domain-specific architectures - Chips designed specifically for transformer models or other common AI architectures, optimizing for the actual workloads rather than general-purpose computation.

The diversity of approaches being pursued suggests the industry recognizes that silicon dominance, while current, isn't inevitable. Multiple technologies will likely coexist, with different strengths for different use cases.

Hyperscalers are actively hedging their bets by investing in research partnerships and early-stage companies exploring these alternatives. This makes sense: if a new technology could reduce their energy costs by 50%, the payoff is enormous. Even a 10% probability of success justifies investment in exploration.

This creates a fertile environment for companies like Neurophos. The market is actively looking for alternatives to pure silicon. Energy efficiency is a major driver of cost. There's sufficient capital available for risky bets. The timing, in other words, is favorable.

But favorable timing isn't guarantee of success. Execution matters. Technical feasibility matters. The ability to build a business around the technology matters.

Integration Challenges: Getting Optical Processors Into Real Data Centers

Let's talk about the practical challenges of actually deploying optical processors in production data centers. This is where many hardware innovations stumble.

Data centers are complex ecosystems. They're not just rows of computers. They have:

Power distribution systems - Designed around specific power characteristics and requirements Cooling infrastructure - Sized and configured for particular thermal loads Network connectivity - Optimized for specific bandwidth and latency profiles Software infrastructure - Operating systems, container runtimes, cluster management, monitoring, logging Security systems - Physical security, network security, data isolation Operational processes - Procedures for deployment, updates, failure handling, scaling

Introducing a completely new type of processor requires rethinking many of these systems.

The power distribution system might need to change. Optical processors have different power draw profiles than GPUs. If the processor operates at lower total power but requires different electrical characteristics, the power delivery system might need redesign.

The cooling system definitely needs to change. Optical processors generate much less heat, which seems like a win. But data center cooling is designed around baseline thermal loads. If one type of processor generates significantly less heat, you can either: (a) operate less cooling, saving energy, or (b) run more processors in the same space, gaining more computation. Either way, the baseline assumptions change.

Network connectivity might need adjustment. Optical processors might have different I/O interfaces or bandwidth requirements than GPUs. Getting data in and out efficiently could require network changes.

Software integration is complex. Data center software assumes certain processor characteristics. Cluster management systems need to understand how to allocate optical processors to workloads. Monitoring systems need to understand how to observe optical processor behavior. Container runtimes need to support the software stack the optical processor uses.

This is where partnerships with companies like Microsoft matter. Microsoft has extensive data center expertise and can work with Neurophos to solve integration challenges. They can help design software interfaces that make optical processors fit naturally into existing data center infrastructure.

There are also questions about standardization. GPUs have become standardized because they follow NVIDIA's CUDA framework and similar software models. Optical processors would need equivalent standardization. The industry would need to agree on interfaces, software models, and operational procedures for optical processors to become truly mainstream.

Neurophos can't create that standardization alone. They need industry partners, participation from other hardware vendors, and eventual adoption by standards bodies. This is a years-long process, even if the technology itself is technically sound.

Economic Model: How Neurophos Actually Makes Money

Let's think about the business model. Neurophos is building a semiconductor company, which means:

High capital requirements - Developing and manufacturing chips is expensive. Billions of dollars in total investment might be needed before profitability.

Thin margins on hardware - Semiconductor companies typically operate on 30-50% gross margins. It's a high-volume business with tight cost control.

Long product development cycles - Multiple years between product concept and revenue.

Competitive pressure - Competing against Nvidia and other established and emerging competitors.

For Neurophos to build a successful business, they likely need to:

Achieve significant volume - Selling thousands or tens of thousands of units to generate meaningful revenue.

Maintain pricing power - If the technology is genuinely superior, customers will pay a premium. But that premium erodes over time as competition emerges.

Build a software and services business - High-margin revenue beyond just selling hardware. Software support, optimization services, and technical consulting could significantly improve margins.

Establish partnerships - Working with cloud providers and systems integrators to bundle optical processors with services creates stickiness.

The semiconductor business is unforgiving. Companies that can't achieve both technical excellence and economic viability don't survive. Many promising semiconductor startups have failed despite having good technology, because they couldn't achieve sufficient volume or pricing to be economically viable.

Neurophos' funding is sufficient for development, but they'll likely need additional capital rounds to fund manufacturing scale-up. The question is whether they can demonstrate sufficient customer interest and performance advantages to justify that additional investment.

Future of Optical Computing: Beyond Neurophos

Neurophos is one of several companies pursuing optical computing for AI, but the broader question is: what does the future of optical computing actually look like?

In the near term (2-3 years), we're likely to see optical interconnects become more common. This is where Lightmatter is focused. Optical connections between chips can move data faster and with less power than electrical connections. This is a lower-risk bet than building entire optical processors.

In the medium term (3-7 years), optical processors for specific workloads might emerge. Rather than trying to be a general-purpose processor like a GPU, optical processors might specialize. For example, optical processors optimized specifically for transformer inference could be very efficient for that specific task.

In the longer term (7-15 years), optical computing could become a mainstream approach to accelerators. You might see data centers with a mix of processors: traditional CPUs for general computing, optical processors for AI inference, quantum processors for specific problems, and other specialized hardware for particular workloads.

This heterogeneous computing future is already starting to happen. AWS offers multiple processor options. Google Cloud has TPUs alongside GPUs. The market is moving toward a diverse ecosystem rather than a single dominant architecture.

Optical computing fits naturally into this diversification. It solves specific problems (energy efficiency for inference) particularly well, which could justify its cost and complexity.

But adoption would require all the pieces to come together: the hardware needs to work as claimed, the software needs to be usable, the manufacturing needs to scale, the economics need to make sense, and customers need to be willing to add another processor type to their infrastructure.

Conclusion: The Bet That Could Reshape Computing Infrastructure

Neurophos' $110 million Series A funding and their mission to build optical processors for AI represents a genuine technological bet that could matter. It's not a sure thing. Many promising startups fail. Many impressive prototypes never become viable products.

But the bet is worth taking seriously for several reasons:

The problem being addressed is real and increasingly urgent. AI data centers are becoming energy bottlenecks. Current silicon-based approaches have diminishing returns. Something will eventually replace them as the dominant paradigm.

The technology has legitimate physics advantages. Optical computing isn't vaporware or science fiction. It's based on real scientific principles that have been validated in labs. The question isn't whether optical computing can work. It's whether Neurophos can make it work at scale, with acceptable costs and manufacturing complexity.

The team has relevant expertise. The company spun out of Duke University and is built on real scientific research. The CEO has articulated a clear technical vision. The company has attracted serious investors and partners.

The market timing is favorable. Energy efficiency is a major driver of AI infrastructure investment. Hyperscalers are actively looking for alternatives to sole reliance on Nvidia. There's enough capital in the ecosystem to fund long-term bets on new technologies.

If Neurophos executes successfully and delivers optical processors that actually offer 50x better energy efficiency for AI inference, the impact would be enormous. Billions of dollars in energy costs could be reduced. Carbon footprints of AI compute could shrink substantially. The economics of building and operating AI systems could change fundamentally.

If the company stumbles—if manufacturing proves harder than expected, or if performance claims don't hold up under real-world testing, or if integration challenges prove insurmountable—the impact is limited to learning what doesn't work.

Either way, Neurophos represents a genuine attempt to rethink how we build computing infrastructure for the AI age. That attempt matters, regardless of whether this specific company ultimately succeeds. The existence of credible alternatives to Nvidia's dominance pushes the entire ecosystem toward innovation.

The real story will emerge between now and 2028, when Neurophos begins shipping products and real-world performance data becomes available. Until then, the claims are promising but unvalidated. The technology is theoretically sound but practically unproven. The opportunity is potentially enormous but far from guaranteed.

What we do know is this: the energy efficiency problem in AI computing is real, growing, and unsustainable on the current trajectory. Something will eventually solve it. Neurophos might be it. Or optical computing might ultimately prove to be a dead end, with the solution coming from a different approach entirely. Either way, the problem ensures that innovation in this space will continue.

TL; DR

- Metasurface technology: Neurophos uses engineered optical materials 10,000 times smaller than traditional optical components, enabling optical computation on a single chip using photonic processes instead of electronic transistors.

- Efficiency claims: The company claims its optical processor delivers 235 petaoperations per second at 675 watts, compared to Nvidia's B200 at 9 petaoperations at 1,000 watts, representing roughly 50x better energy efficiency for AI inferencing.

- Manufacturing promise: Neurophos asserts that metasurface modulators can be manufactured using standard silicon foundry processes and materials, solving the traditional optical computing challenge of requiring exotic manufacturing infrastructure.

- Serious funding backing: Gates Frontier, Microsoft's M12 venture arm, and Aramco Ventures' participation signals institutional confidence in both the technology's feasibility and the global importance of AI energy efficiency.

- Path to market: The company plans to ship first production chips by mid-2028, with immediate focus on datacenter-ready modules, complete software stacks, and developer early-access hardware to validate real-world performance claims.

FAQ

What exactly is a metasurface modulator?

A metasurface modulator is a thin, engineered material layer designed to control light propagation using specially structured surfaces. Unlike traditional optical components that physically move to alter light paths, metasurface modulators achieve this control through their material structure itself, allowing extremely compact optical computation without heat-generating electron movement.

How does Neurophos' optical processor perform matrix multiplication differently than GPUs?

Traditional GPUs perform matrix multiplication using electronic transistors and electrical signals, which generate substantial heat. Neurophos' optical processing unit encodes numbers as the intensity or phase of light beams, passes them through metasurface structures, and lets the physics of light propagation perform the mathematical computation in the optical domain, producing results with minimal heat generation.

Why does energy efficiency matter so much for AI data centers?

AI inference at hyperscale requires running billions of inference requests daily through trained models. This demands enormous electrical power that generates proportional heat, requiring expensive cooling infrastructure and constant energy input. A 50x improvement in energy efficiency directly reduces operational costs by billions of dollars annually and significantly lowers the carbon footprint of AI computation.

What's the realistic timeline for Neurophos to actually deliver products?

The company targets mid-2028 for first production shipments. This timeline requires successfully completing hardware engineering, manufacturing qualification with foundry partners, solving reliability and integration challenges, and establishing production capacity. History suggests semiconductor companies often face delays, though Neurophos' experienced team and substantial funding improve execution odds.

Can Neurophos actually compete with Nvidia's dominance?

Nvidia has insurmountable advantages in market position and installed software ecosystem. However, if Neurophos delivers substantially better energy efficiency specifically for inference workloads, they could capture significant market share in that specific application domain. Hyperscalers are actively seeking alternatives to reduce energy costs and dependence on single suppliers.

What's the biggest risk to Neurophos' success?

The largest risk isn't the core science, which has been validated. It's executing complex hardware and software engineering at scale, manufacturing the metasurface modulators with acceptable yields and costs, integrating optical processors into existing data center infrastructure, and ultimately demonstrating that real-world performance matches theoretical claims. Any significant failure in these areas could prevent commercial viability.

How does manufacturing optical processors compare to manufacturing traditional silicon chips?

Optical components have traditionally been difficult to mass-produce compared to silicon. Neurophos claims their metasurfaces can be manufactured using standard silicon foundry tools and processes, which would be transformative. However, this claim requires independent validation—optical systems typically have tighter manufacturing tolerances than electronic systems, and even small variations can affect performance.

Will existing AI software work on optical processors without modification?

Neurophos is building compilers and software tools that automatically optimize existing PyTorch and TensorFlow code for optical execution. The goal is to make optical processors appear as another accelerator option, similar to how GPUs work today. However, some applications might require tuning for optimal optical processor performance, particularly for inference workloads with unique characteristics.

What happens if Neurophos' energy efficiency claims don't hold up in real deployment?

If real-world performance is significantly below claims, adoption would likely be limited. However, even modest efficiency improvements would be valuable to hyperscalers. The technology would probably find applications in specific inference scenarios, and the company could pivot toward optical interconnects or other components rather than full processors.

Could optical computing eventually replace silicon for all computing tasks?

Optical computing excels at specific tasks involving parallel matrix operations with limited state management. It's less suited for tasks requiring rapid branching, conditional execution, or complex state management that traditional processors handle efficiently. The future likely involves heterogeneous computing with different processor types optimized for different workloads, rather than optical computing entirely replacing traditional processors.

This article explores the technology, market dynamics, and realistic prospects for optical computing in AI infrastructure. The statements and performance comparisons reflect the company's claims and represent possibilities rather than validated achievements. Independent verification of Neurophos' performance claims will become possible as the company begins delivering developer hardware and production systems.

Key Takeaways

- Metasurface modulators enable optical computation 10,000 times smaller than traditional optical transistors, solving previous manufacturing bottlenecks

- Neurophos claims 235 petaoperations per second at 675 watts versus Nvidia B200's 9 POPS at 1,000 watts, representing theoretical 50x efficiency advantage for inference workloads

- Gates Frontier, Microsoft's M12, and Aramco Ventures' participation signals institutional validation of optical computing's viability for commercial AI applications

- Production timeline targets mid-2028, requiring successful hardware engineering, manufacturing qualification, software development, and integration with existing datacenter infrastructure

- Optical computing addresses energy efficiency crisis in AI data centers, where cooling and electricity costs now rival hardware amortization expenses

- Success depends not just on hardware performance but on building complete software ecosystem making optical processors transparent to existing AI frameworks like PyTorch

Related Articles

- Robot Swarms That Bloom: The Future of Adaptive Architecture [2025]

- Best Winter Tech for 2026: Must-Have Gear to Beat the Cold [2026]

- AI Data Centers & Carbon Emissions: Why Policy Matters Now [2025]

- AI Storage Demand Is Breaking NAND Flash Markets [2025]

- Gate-All-Around Transistors: How AI is Reshaping Chip Design [2025]

- US Government 25% Tariff on AI Chip Exports to China [2025]

![Neurophos Optical AI Chips: How $110M Unlocks Next-Gen Computing [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/neurophos-optical-ai-chips-how-110m-unlocks-next-gen-computi/image-1-1769096479988.png)