Gate-All-Around Transistors: How AI is Reshaping Chip Design [2025]

We're at a crossroads in semiconductor engineering. The rule that predicted chip progress for over fifty years is hitting a wall. What used to be predictable doubling of transistor density every twenty-four months has slowed to a crawl. Meanwhile, artificial intelligence demands are skyrocketing. Data centers are drowning in power consumption. Edge devices need faster processing with less energy. Something had to give.

That something is how we fundamentally design transistors themselves.

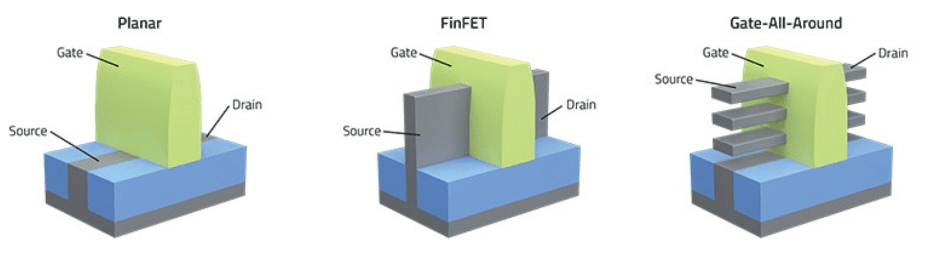

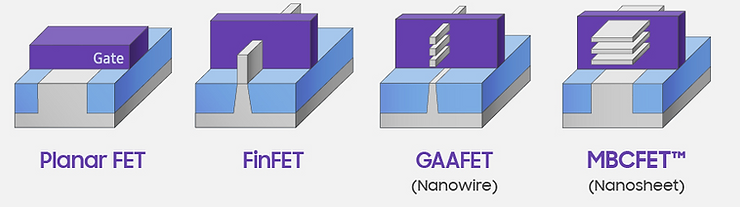

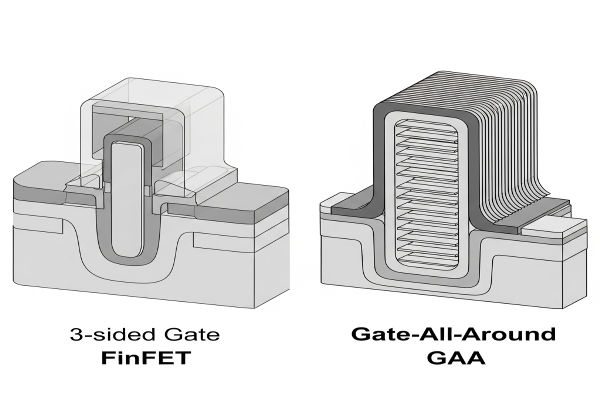

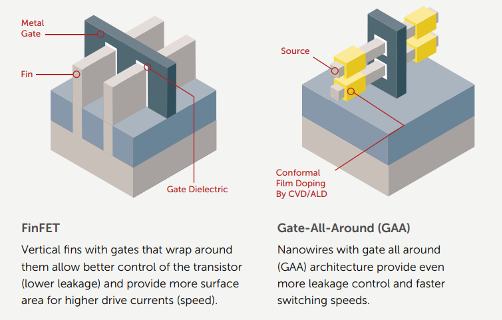

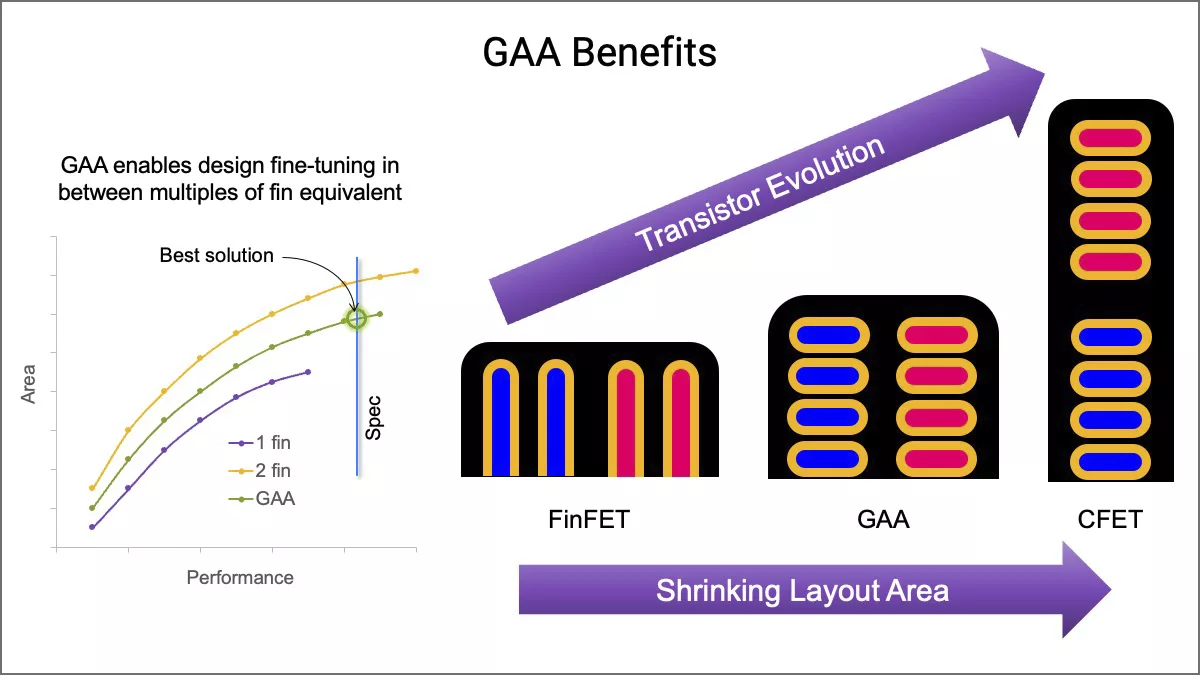

For the past decade, the industry relied on a proven approach: Fin FETs (Fin Field Effect Transistors). These tiny three-dimensional fins of silicon provided better control over current flow than their flat predecessors, and they worked well enough to push us from one technology node to the next. But Fin FETs have limits. As transistors shrink to 3 nanometers and beyond, the electrical physics breaks down. The gate loses control. Leakage increases. Variability becomes unpredictable.

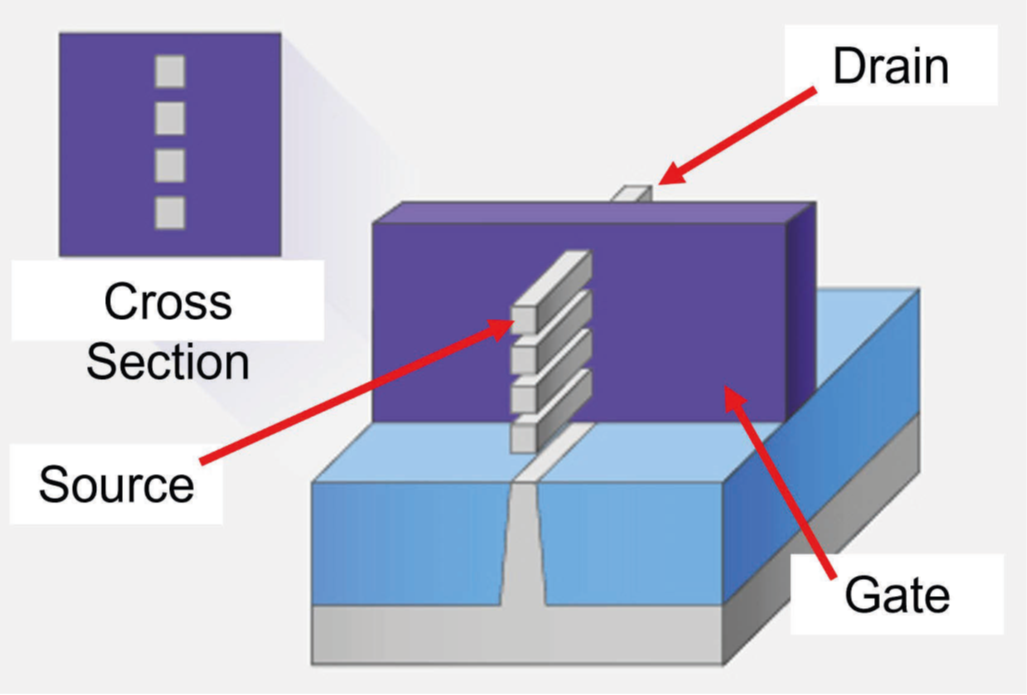

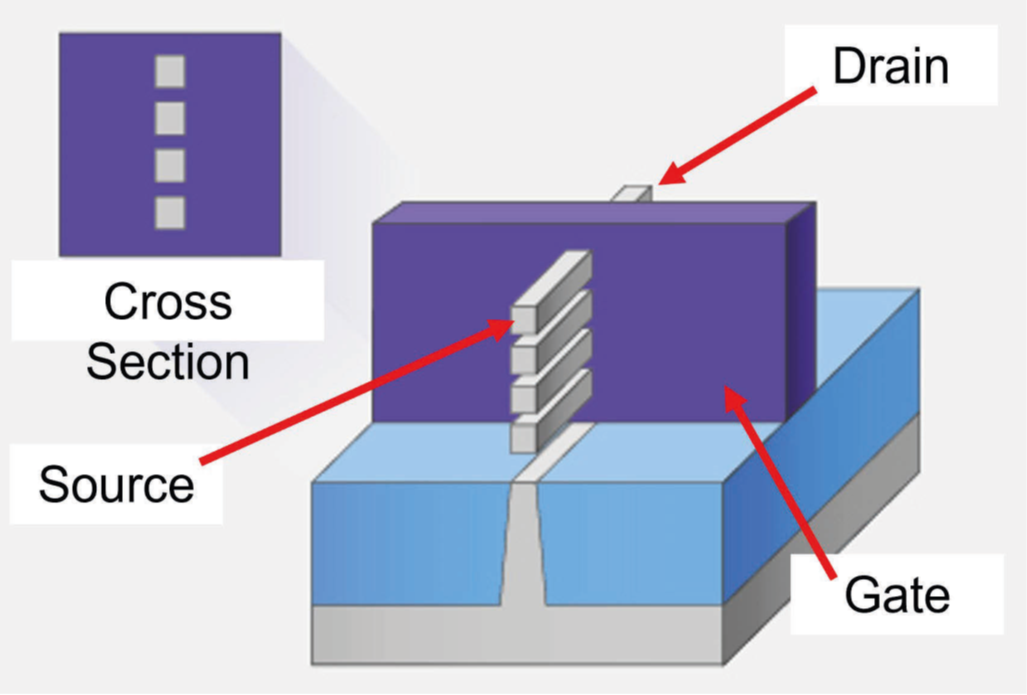

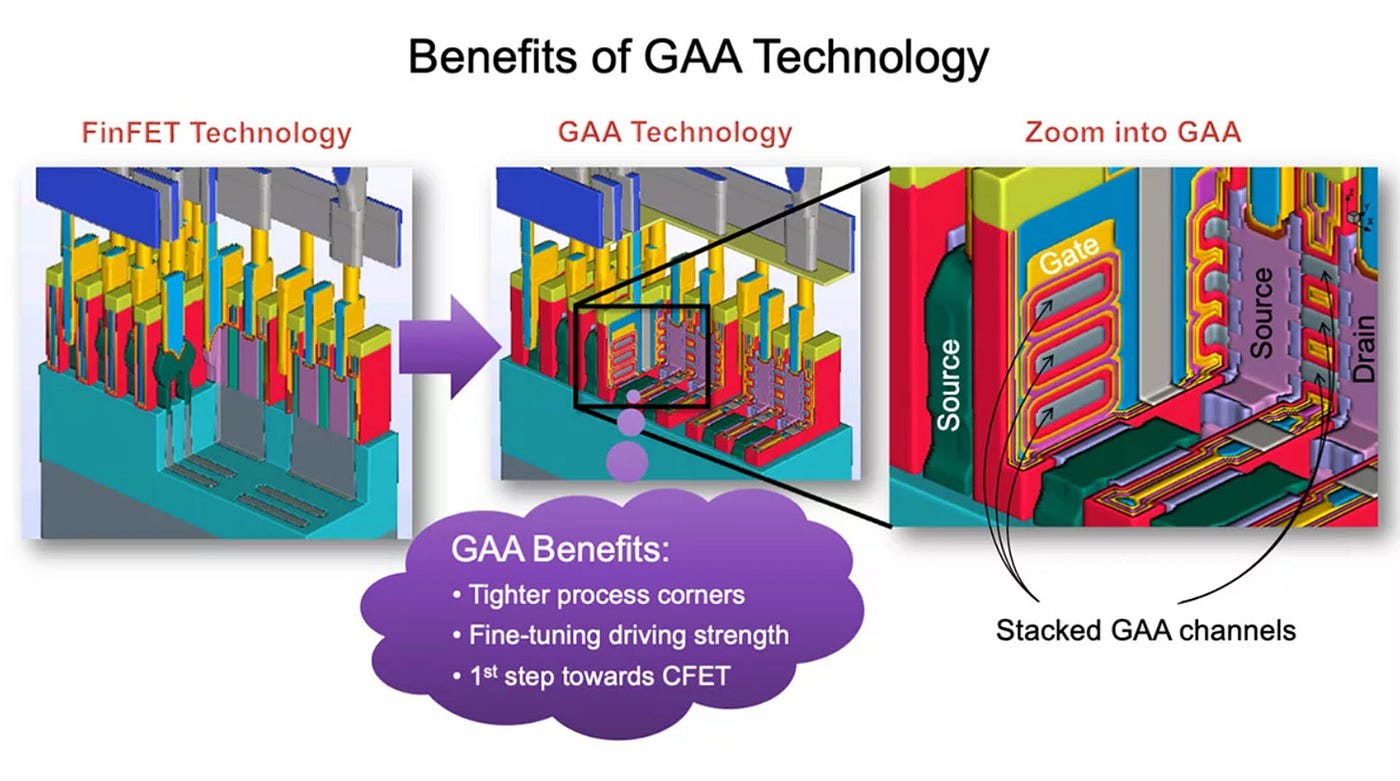

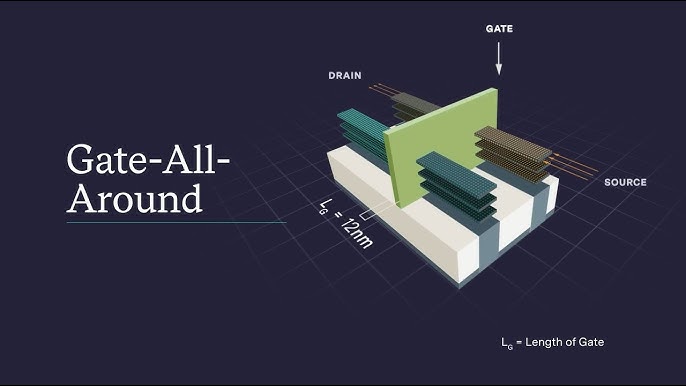

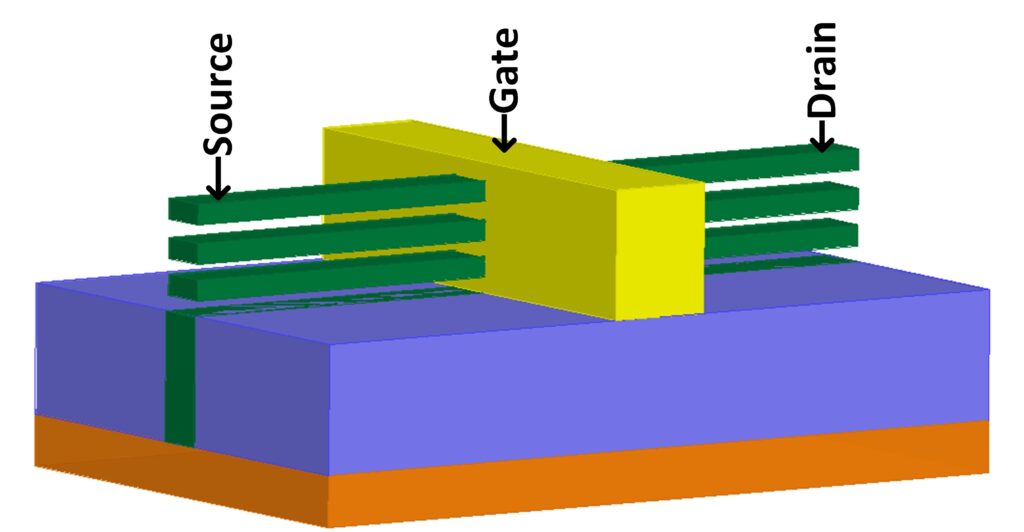

Enter gate-all-around (GAA) transistor design. Instead of a gate touching silicon from three sides, imagine wrapping the gate completely around the channel like a cylindrical sleeve. This architectural shift changes everything about how current flows and how engineers can pack more performance into the same silicon real estate.

But GAA alone isn't the solution. The real breakthrough comes from pairing it with advanced materials engineered at the atomic scale. Barrier layers that block dopant diffusion. Metal alloys that reduce contact resistance. Interface engineering that smooths carrier pathways. These aren't small tweaks. They're fundamental shifts in how semiconductor physics works.

Let's explore what's actually happening inside these next-generation chips, why it matters for AI infrastructure, and what comes after GAA pushes its limits.

TL; DR

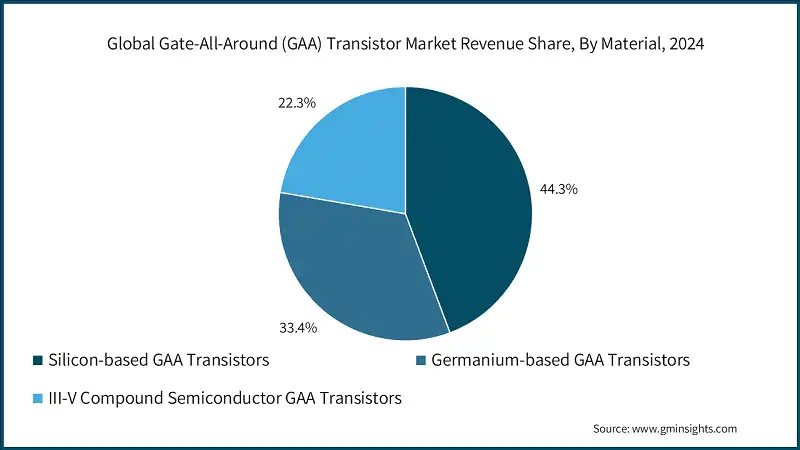

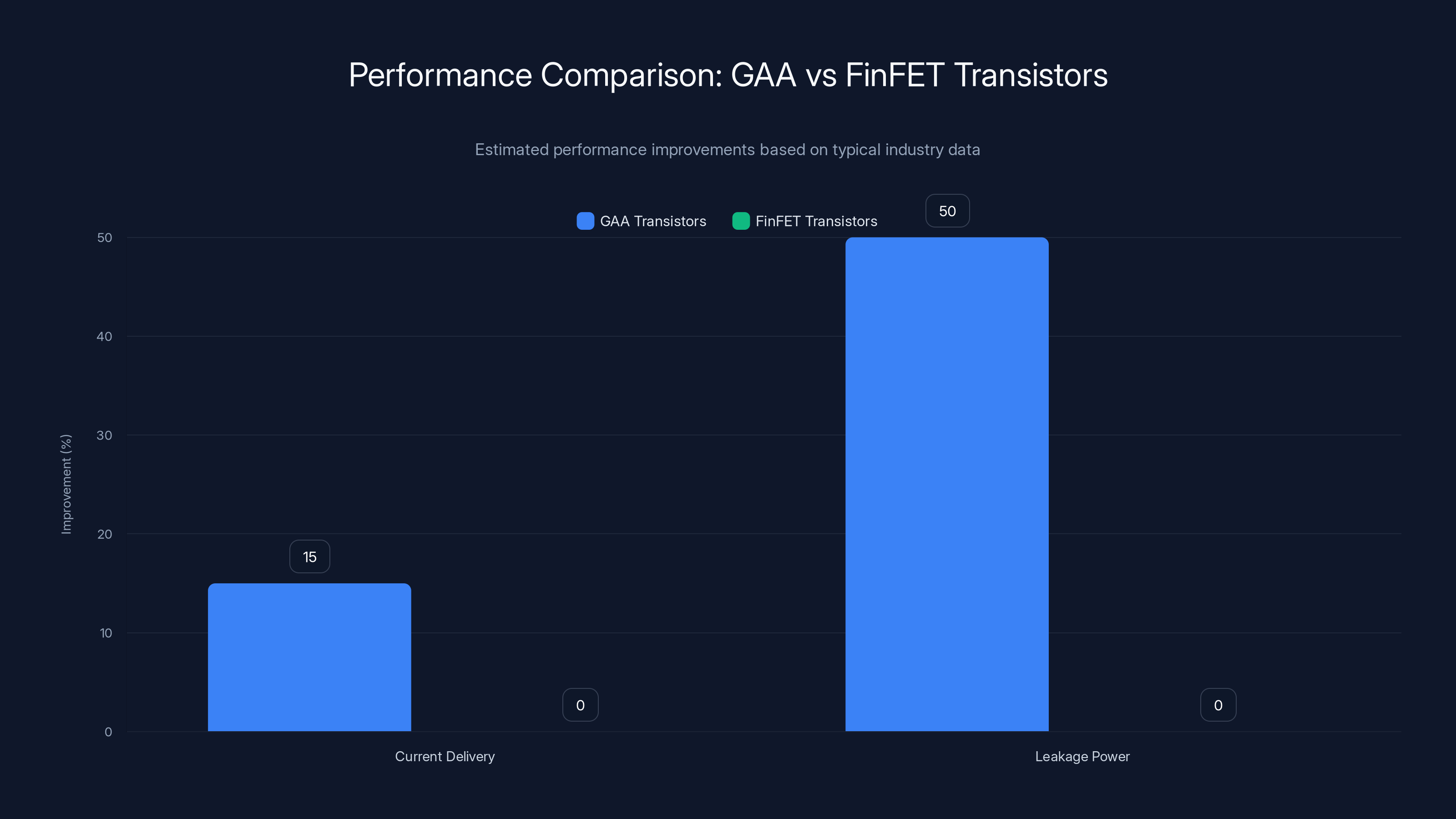

- GAA transistors wrap gates completely around the channel, giving 30-40% better gate control and enabling 10-15% current improvements without increasing chip size

- Advanced materials are the missing piece, solving new bottlenecks that GAA creates, including dopant diffusion, contact resistance, and surface roughness

- The AI boom makes this urgent: Current data center chips consume 300-400W per processor, creating pressure for energy-efficient scaling

- The path forward includes CFET structures and 3D stacking, likely arriving in the 2027-2029 timeframe, requiring completely new material systems

- Chipmakers like Intel, Samsung, and TSMC are all racing to master GAA manufacturing while managing yield challenges and cost pressures

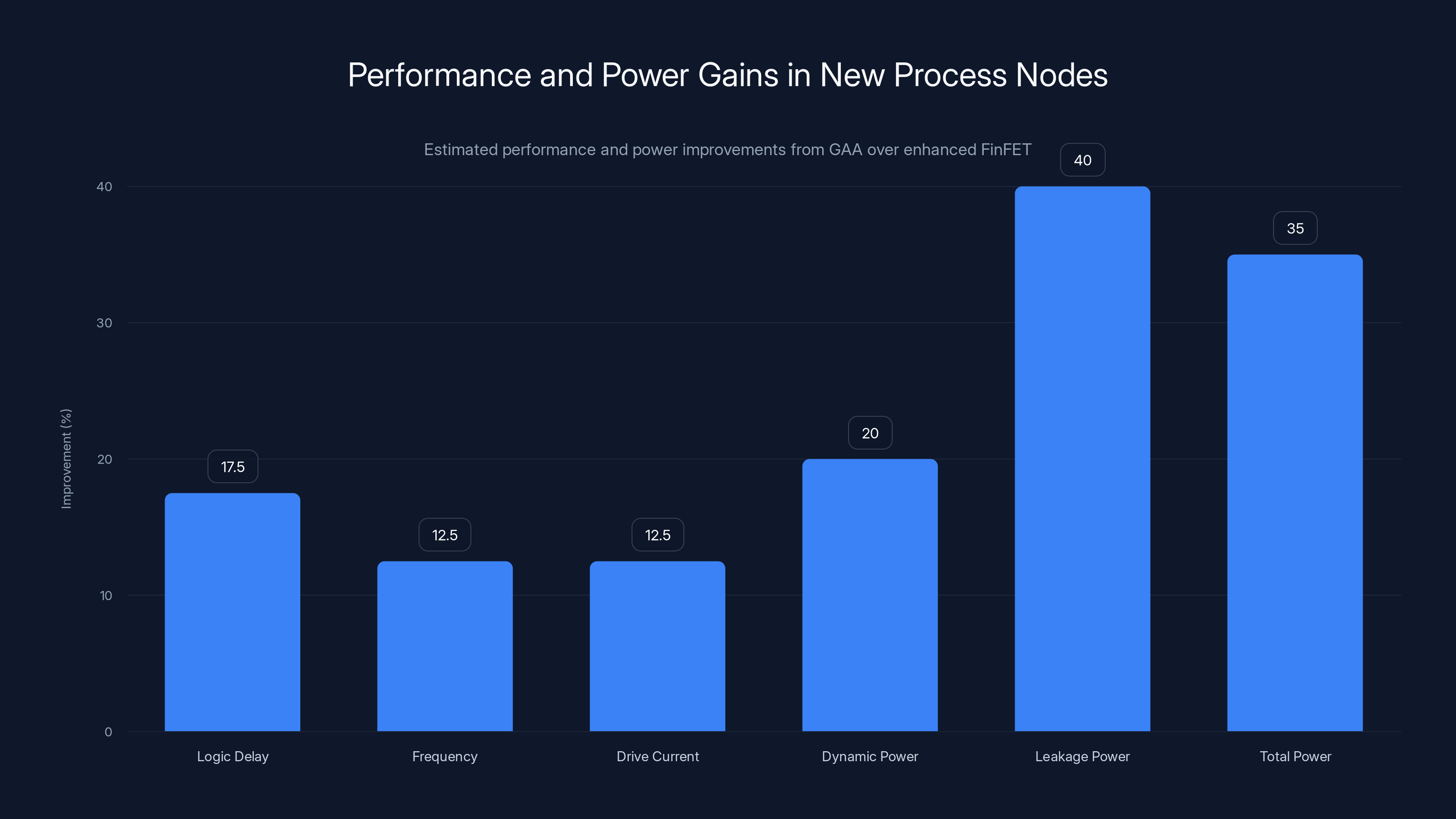

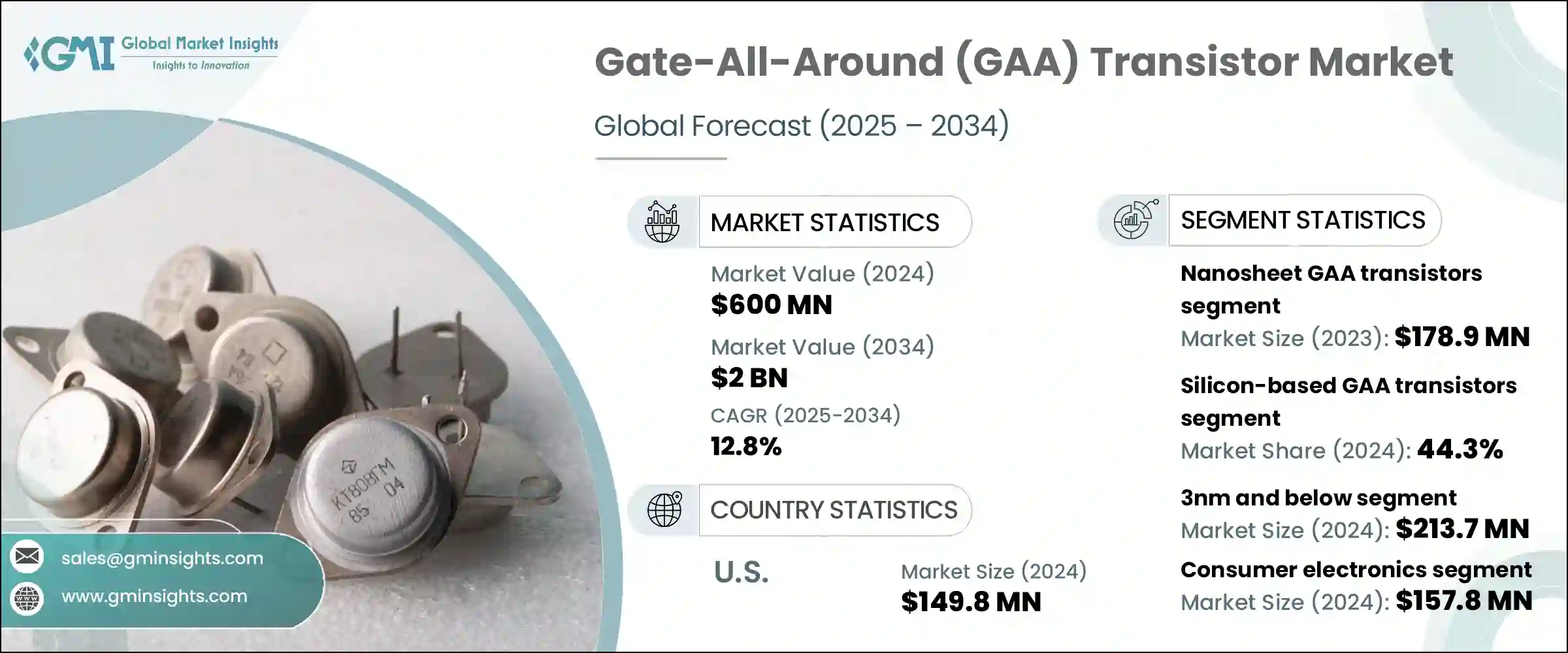

Estimated data shows significant improvements in logic delay, frequency, and power metrics with GAA technology over enhanced FinFET, highlighting the potential for substantial performance gains and power savings.

Understanding the Transistor Crisis: Why Fin FETs Hit a Wall

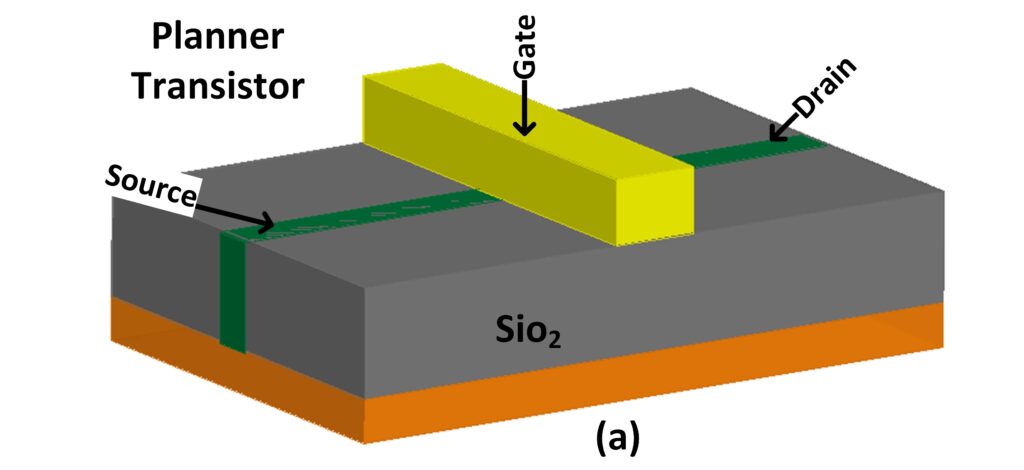

To understand why gate-all-around design matters, you need to know why conventional transistor scaling stopped working.

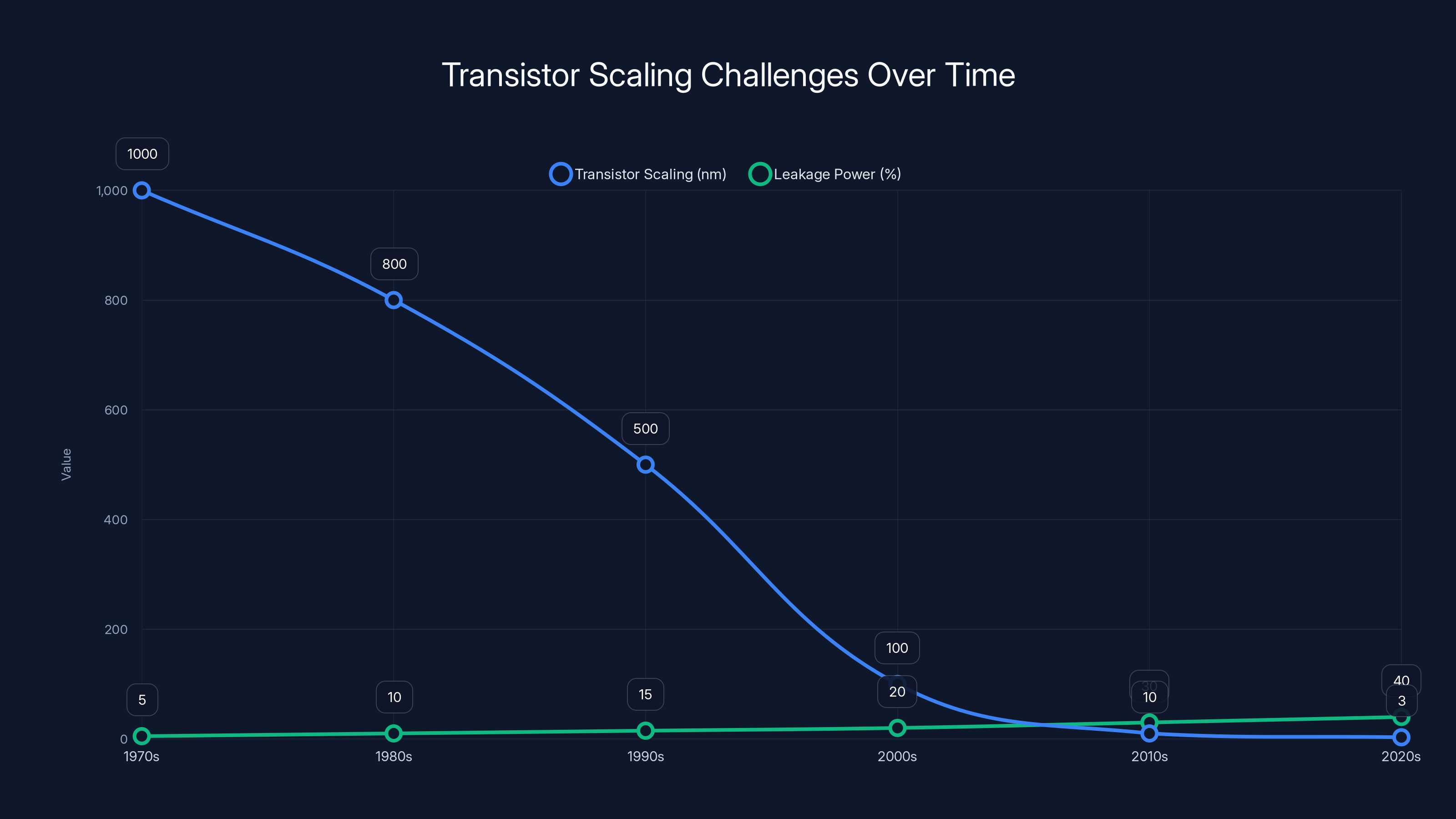

Since the 1970s, semiconductor manufacturers have followed a predictable roadmap. Shrink features. Increase density. Achieve predictable performance gains. This worked beautifully for decades because the underlying physics remained stable. A smaller transistor ran faster, consumed less power, and cost less per unit area. Simple.

But physics has limits.

When you shrink a Fin FET aggressively, the gate loses its grip. The electric field that controls current flow weakens. Electrons leak through the junction even when the transistor should be off. This isn't a design flaw—it's quantum mechanics asserting itself. At 3 nanometers, the silicon channel becomes so thin that quantum tunneling creates parasitic paths for current.

The gate itself becomes problematic. In older designs, the gate was a thin conducting layer touching the top and sides of a silicon fin. At modern dimensions, this geometry doesn't provide enough electrostatic control. The field doesn't penetrate evenly. You get hot spots. Variability increases. Some transistors behave differently from their neighbors on the same chip.

Then there's the leakage problem. A 2024 industry analysis showed that static power consumption—power drawn even when transistors aren't switching—accounts for 30-40% of total energy use in modern processors. As gate control weakens, leakage grows exponentially. This becomes a show-stopper for mobile devices and edge AI accelerators where battery life matters.

Chipmakers tried incremental solutions. Thinner gates. Higher gate dielectric constants. Strain engineering to improve mobility. These helped, but each solution only extended the timeline by a node or two. By the time 5-nanometer and 3-nanometer designs were in production, everyone knew: Fin FETs were approaching their asymptotic limit.

The AI explosion made this crisis urgent. A single high-end AI training run can cost hundreds of thousands in electricity alone. Data center operators demanded chips that could deliver more compute per watt. The time for incremental improvements had ended.

What Gate-All-Around Actually Does: The Architectural Shift

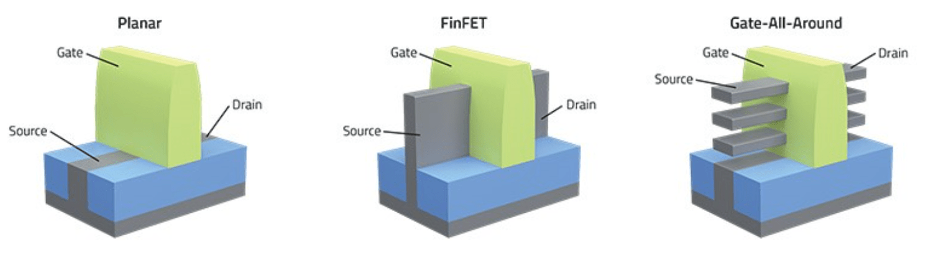

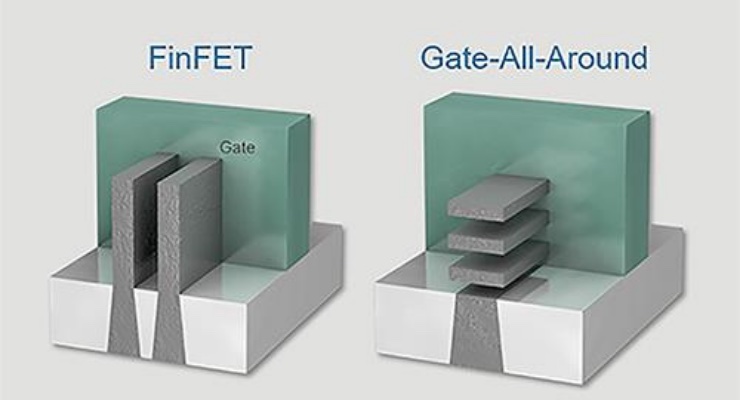

Gate-all-around transistor design sounds complex, but the core concept is elegant: instead of a gate controlling current from three sides, wrap it around all sides simultaneously.

In traditional Fin FET designs, the gate is a conductor layer that touches the top of the silicon fin and its two outer sidewalls. Three sides of contact. The fourth side (the bottom) sits on the substrate. Current flows through the uncontrolled bottom region, and the gate field doesn't penetrate evenly.

In GAA design, the channel itself becomes cylindrical or nearly cylindrical. The gate material completely surrounds it, like a hollow tube of conductor running through the silicon. This creates a few critical advantages.

First, electrostatic control improves dramatically. Because the gate touches the channel on all sides, the electric field penetrates uniformly. When you apply a voltage to the gate, it affects the entire channel diameter consistently. This uniformity reduces variability. You get more predictable behavior from transistor to transistor across the chip.

Second, you can operate with better gate control at lower voltages. The stronger coupling between gate and channel means you don't need to push as much current to get the same switching speed. This translates to lower dynamic power consumption. Measurements from prototype chips showed 10-15% improvements in current delivery at the same voltage, or alternatively, the same current at 10-15% lower voltage.

Third, GAA enables what the industry calls "gate length scaling." In Fin FETs, you can only shrink the gate length (the direction of current flow) so much before electrostatic effects dominate. GAA's superior coupling allows smaller gates while maintaining control. This means you can pack more transistors into the same area.

Here's the problem nobody talks about publicly: GAA moves the bottleneck, not eliminates it.

When gate control improves, other resistance mechanisms become the limiting factor. Specifically, the resistance in the channel itself, and the contacts where current enters and exits the transistor. These weren't problems before because the gate was the bottleneck. Now they're front and center.

In a GAA transistor, the channel resistance comes from two sources. First, the intrinsic resistance of the silicon itself as current flows through it. This can be reduced through doping (adding impurities to increase conductivity). Second, the parasitic resistance from imperfect crystal structure, defects, and scattering of charge carriers. You can't eliminate this without engineering the material itself.

Then come the contacts. Metal (typically tungsten or cobalt) needs to connect to the silicon channel at specific points. At the metal-silicon interface, you have a barrier. Current has to tunnel or hop over this barrier. As contacts shrink along with transistor dimensions, this resistance becomes a larger percentage of total transistor resistance.

This is where conventional material science fails. You can't simply shrink everything proportionally and expect the same physics to apply. The contact resistance doesn't scale the way gate length does. You need new materials and new interface engineering.

As transistor sizes have decreased from the 1970s to the 2020s, leakage power has increased significantly, highlighting the challenges faced by FinFETs at smaller scales. Estimated data.

The Material Challenge: New Physics at the Atomic Scale

Once engineers understood that GAA created new bottlenecks, the solution wasn't redesigning the transistor shape again. It was engineering the materials themselves at the atomic level.

Consider dopant diffusion, which sounds technical but has practical implications. When you're building a GAA transistor, you need heavily doped regions (called source and drain) to improve conductivity, and lightly doped or undoped channels. The doping process involves heating the silicon and allowing dopant atoms to diffuse in from the surface. It's essentially controlled contamination.

But diffusion isn't perfectly controllable. Dopant atoms don't respect boundaries. They keep diffusing, bleeding into regions where you don't want them. In a Fin FET, this was annoying. In a GAA transistor with tight dimensions, it's catastrophic. Extra dopants in the channel increase resistance, shift the threshold voltage (the gate voltage needed to turn the transistor on), and create variability from one transistor to the next.

The solution: barrier materials inserted at atomic precision. These are ultrathin layers of specialized compounds—often carbon-doped or nitrogen-doped variants of silicon dioxide—that block dopant diffusion while still allowing current flow. Getting these thin enough (sometimes just a few atomic layers) while keeping them uniform across an entire wafer is a manufacturing miracle that few companies have achieved.

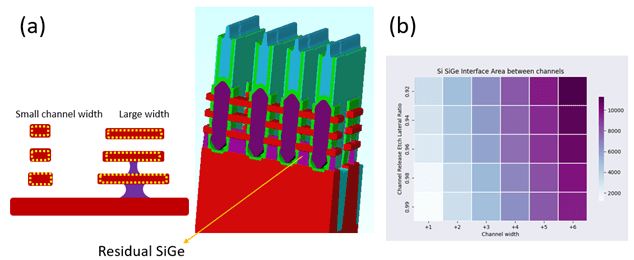

Next, consider surface roughness. When GAA transistor channels are fabricated, one step involves removing silicon-germanium (Si Ge) layers that act as a placeholder. This "spacer removal" process creates the cylindrical channel. But if you're not careful with the chemistry and process timing, you leave behind a microscopically rough surface.

At the atomic scale, a rough surface scatters electrons. Imagine electrons trying to flow through a channel with nanoscale hills and valleys. Every irregularity deflects them, reducing mobility (the ability of electrons to move quickly). In older transistors, surface roughness cost you 5-10% in performance. In GAA transistors with very small channels, the same roughness costs you 15-25%.

Advanced surface treatment—sometimes using plasma processes, sometimes using selective deposition of crystalline materials—can smooth these surfaces. The goal is creating atomically smooth channels where electrons can flow unobstructed. When successful, you recover 10-15% of the performance lost to scattering.

Contact resistance deserves its own focus. As metal contacts to silicon shrink below 20 nanometers in cross-section, the contact resistance becomes a dominant factor. You can't just use the same tungsten contacts that worked at larger dimensions.

Engineers are experimenting with several material approaches. First, modifying the silicon surface before metal deposition. Techniques like selective germanium enrichment or fluorine implantation create a more favorable interface for metal-silicon contact. Second, using different metals or metal alloys that have better contact properties with silicon—cobalt silicides, nickel alloys, even exotic materials like molybdenum.

Third, and most advanced, inserting ultra-thin intermediate layers between metal and silicon that facilitate electron transport. These might be monolayer materials, doped oxide layers, or crystalline compounds specifically engineered to minimize the contact barrier height.

The catch: each of these requires new processing steps, new tools, and new expertise in material characterization. You need to understand these materials' properties at the atomic level, predict how they'll behave when deposited, predict how they'll age and change, and control them across a 300-millimeter wafer with zero defects.

The AI Acceleration Context: Why This Matters Now

GAA wouldn't be so urgent if AI demand were static. But it's not. It's accelerating exponentially.

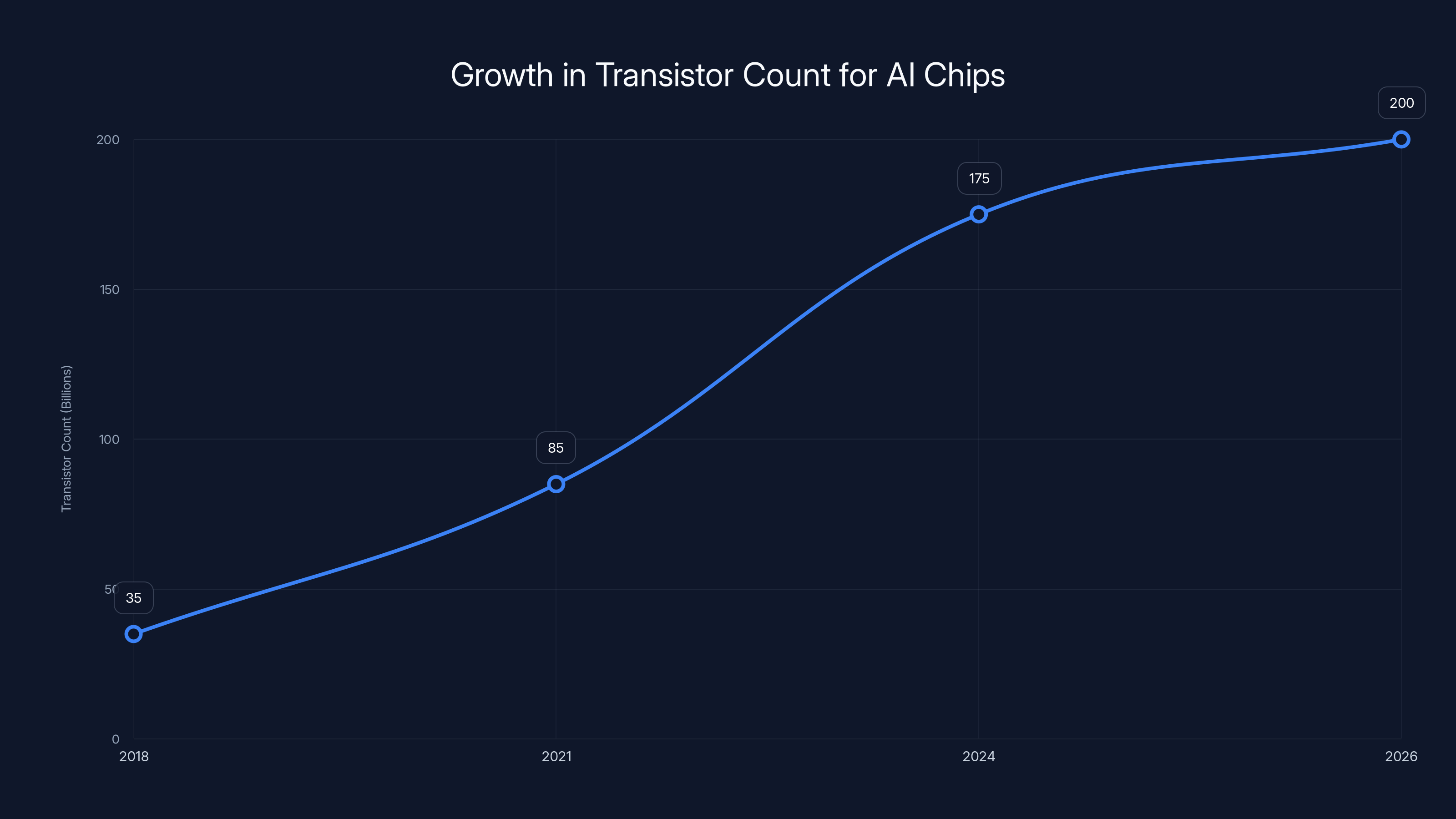

Consider what's happening in data centers. Five years ago, the standard GPU accelerator for AI had around 20-50 billion transistors. Today's flagship chips have 70-100 billion transistors. Within three years, the industry expects 150-200 billion transistor devices to become standard. This density increase would be impossible with Fin FET technology.

Moreover, AI workloads are energy-intensive. A single inference on a large language model can consume 10-50 joules of energy depending on model size and precision. Data centers running millions of inferences per day need aggressive power management.

There's also the matter of training costs. A single training run of a frontier model—training GPT-4 scale or larger—can take weeks on thousands of GPUs. The electricity bill can exceed $10 million. Every 5% improvement in efficiency translates to hundreds of thousands of dollars saved.

This creates enormous economic pressure on chipmakers to extract maximum performance from every layer of silicon. GAA with advanced materials is the only realistic path to continue delivering the 15-20% generation-over-generation improvements that the industry expects.

But there's a secondary driver: edge AI. Smartphones, industrial cameras, autonomous vehicles, and Io T devices need AI processing without the luxury of a power outlet. These devices run on batteries or scavenged power. Energy efficiency at the transistor level directly determines whether a device can do useful AI computation or just consume the battery uselessly.

A smartphone So C (system-on-chip) from 2025 might dedicate 20-30% of its transistors to AI acceleration. That's 2-3 billion transistors focused purely on inference. With Fin FET technology, fitting that much AI capability would require excessive power. With GAA, the same capability fits in a realistic power envelope (roughly 1-2 watts for the AI block).

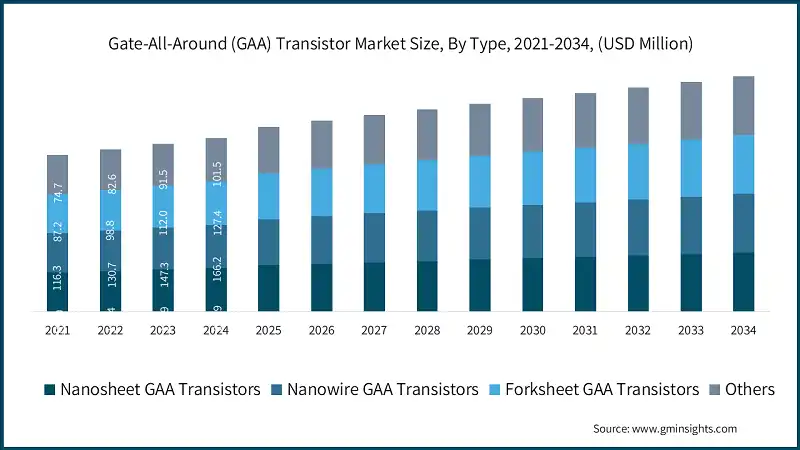

Chipmakers see this clearly. Intel, AMD, ARM, TSMC, Samsung, and others have all publicly committed to GAA as their primary transistor architecture for the 3nm node and beyond. This isn't speculation—it's happening now in production. Chips based on GAA are already shipping in consumer products.

The Manufacturing Reality: Getting Yield and Cost Right

Here's where theory meets practical engineering: actually manufacturing GAA transistors at scale is harder than the design looks.

A Fin FET manufacturing process requires roughly 400-500 photolithography steps (masking, etching, deposition, and patterning). GAA requires additional steps, sometimes pushing toward 600+ steps for mature processes. More steps mean more opportunities for defects. Each step needs to be controlled to atomic precision.

The spacer removal step (creating the cylindrical channel) is particularly tricky. You need to selectively remove silicon-germanium without damaging the gate or the surrounding structures. Use the wrong etch chemistry or the wrong timing, and you either leave too much Si Ge (creating a thicker channel and shifting the threshold voltage) or etch too far (damaging the gate oxide and reducing device reliability).

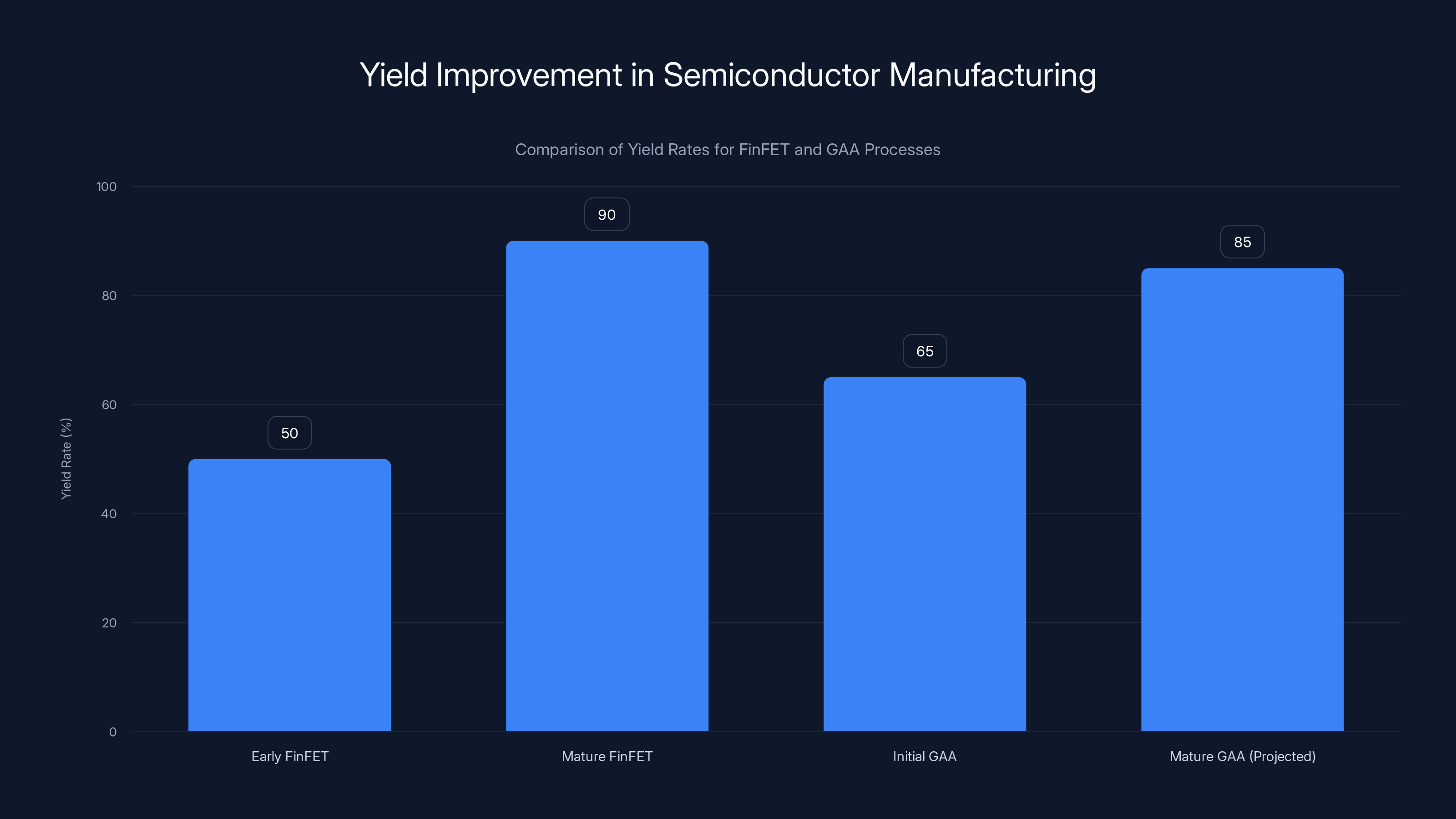

Yield—the percentage of working chips from a production wafer—is the practical metric that matters. In the early days of Fin FET, yield was around 40-60%. Today, it approaches 90%+ for mature processes. With GAA's complexity, expect initial yields of 60-70%, gradually improving as the process matures.

Lower initial yields mean higher costs. A 5-nanometer GAA wafer might cost

This is why chipmakers are strategically deploying GAA. TSMC's N3 (3 nanometer) process uses GAA, but N5 (5 nanometer) still uses enhanced Fin FETs. Intel's Intel 4 uses GAA, but Intel 7 doesn't. Samsung's 3GAE uses GAA. This tiered approach lets them optimize cost and performance for different products.

There's also the integration challenge. GAA transistors don't exist in isolation. They need to connect to metal interconnects, capacitors, inductors, and power distribution networks. All these elements need to scale proportionally. A breakthrough in transistor design means nothing if the interconnects become the bottleneck.

What's actually happening in advanced fabs: simultaneous innovation across every layer. Intel talks about "process-device-co-design"—the idea that you can't optimize transistors and interconnects separately. You need to design them together, making trade-offs that benefit the overall chip.

This is fundamentally different from how the industry worked ten years ago. Back then, you'd design a transistor, publish papers about it, and once it was proven, you'd work on interconnect optimization separately. Now, top-tier fabs have teams working on transistors, materials, interconnects, and power delivery as a unified system.

The result is chips that are dramatically more efficient than the design rules would predict. A 3nm GAA chip might deliver 40-50% more performance than a Fin FET chip at the same power level, while using only 2x the transistor count. That efficiency gain is the whole point of the advanced materials and architectural changes.

The transistor count in AI chips is projected to grow from 35 billion in 2018 to 200 billion by 2026, reflecting the exponential demand for AI processing power. Estimated data.

Beyond GAA: The Next Architectural Transitions

GAA is powerful, but it has limits. Chipmakers are already designing for what comes next.

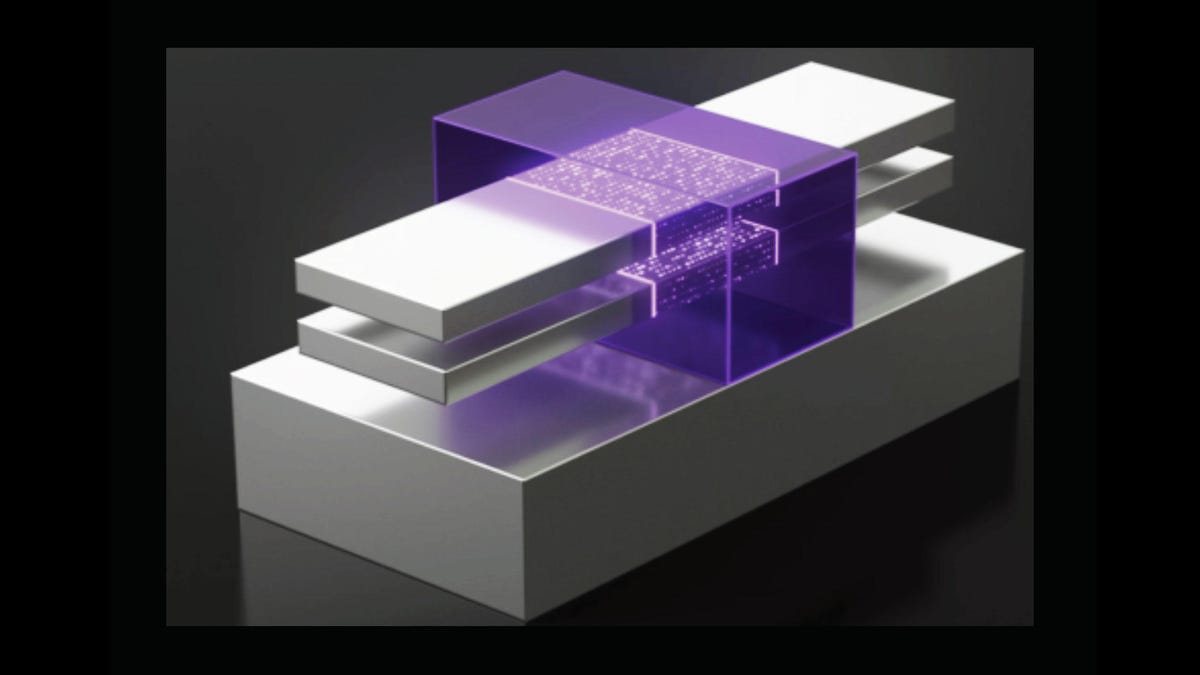

The leading candidate is CFET (complementary FET). Instead of one transistor that either conducts or blocks, you stack two complementary transistors vertically: an n-channel (electrons) on top of a p-channel (holes). Both can be optimized for their specific role. You can tune one for speed and the other for power efficiency. The device footprint stays roughly the same, but you get more functionality.

CFET enables what's called "monolithic 3D" integration—stacking transistors vertically without using separate dies. This is different from traditional 3D chip stacking (chiplets soldered together). Monolithic 3D means multiple layers of transistors integrated on a single piece of silicon, with their metallization layers tightly coupled.

The density advantage is massive. Instead of 2D scaling (shrinking horizontal dimensions), you scale vertically. You can achieve 2-3x improvement in transistor density without shrinking the smallest feature size. This buys the industry 2-3 more generations of Moore's Law without hitting physical limits as aggressively.

But CFET introduces new engineering challenges. You're stacking transistors separated by just 5-10 nanometers of insulation. Heat management becomes critical—the upper layers run hotter because the lower layers don't conduct heat as effectively. You need thermal optimization throughout the structure.

There's also the question of which transistor type goes on top. Current thinking favors putting p-channel on top (for speed, relying on lower carrier mobility being acceptable in upper tiers), but this will evolve as designs mature.

After CFET comes stacked CFET, where you have multiple vertical layers of complementary pairs. This could enable 10x density improvements compared to 2D transistors, but requires solving even harder thermal and reliability challenges.

The timeline: CFET is expected to appear in production around the 2027-2029 window. Stacked CFET might be 2029-2032. These are aggressive predictions, but chipmakers are confident because the physics is well-understood—it's an engineering problem, not a science problem.

The material requirements for CFET are even more demanding than for GAA. You need materials that work at multiple vertical levels. Thermal conductivity becomes critical—you'll need engineered phononic structures that guide heat efficiently without allowing crosstalk between layers. You'll need new dielectric materials with specific properties that don't currently exist in volume production.

This is why advanced materials research is happening now, years before CFET enters production. Chipmakers are betting billions on material innovation because architectural innovation alone won't deliver the needed improvements.

Advanced Materials Deep Dive: The Specific Solutions

Let's get specific about the material solutions that are enabling GAA and will enable CFET.

Dopant Barriers and Diffusion Control

The most advanced production GAA processes use engineered dopant barriers—ultra-thin layers inserted between source/drain regions and the channel. These barriers have several requirements:

- Conductivity high enough to not add significant series resistance

- Atomic-scale thickness (typically 2-5 nm) to minimize impact on device dimensions

- Perfect integrity—even pinholes can allow dopant diffusion

- Thermal stability—the barrier must survive thermal cycles without degrading

Current solutions include carbon-doped oxide (CDO) layers, nitrogen-infused Si O₂, and proprietary metal-based barriers used by specific chipmakers. These are deposited using atomic layer deposition (ALD), a technique that adds material one atomic layer at a time, providing extraordinary precision.

The yield challenge with barriers is achieving perfect coverage. On a 300mm wafer, a single pinhole in a barrier layer affecting just 0.001% of transistors creates a defect. You need 99.999%+ coverage uniformity. This is why only the most advanced fabs have reliable barrier deposition.

Surface Roughness Mitigation

Smoothing atomic-scale surface irregularities requires several coordinated approaches:

- Selective epitaxy: Growing crystalline silicon or germanium specifically on rough surfaces to fill in valleys

- Plasma smoothing: Using carefully controlled plasma etch processes that preferentially remove peaks

- Chemical mechanical polishing optimization: Tuning slurries and pressures to smooth without over-removing material

- Post-etch annealing: Thermal treatment that allows atoms to rearrange and reduce surface energy

Each technique has trade-offs. Epitaxy is very precise but slow. Plasma smoothing is fast but hard to control. The state-of-the-art combines multiple approaches, applying the right technique at each step of the process.

The measurement challenge: you can't actually see atomic-scale roughness in production—it's too small. Instead, fabs use indirect measurements: electrical testing (mobility measurements), transmission electron microscopy on sample wafers, and modeling based on process parameters. This is where the partnership between process engineers and materials scientists becomes critical.

Contact Engineering

Contact resistance reduction is actively being attacked from multiple directions:

-

Metal selection: Moving from tungsten (W), which has high contact resistance, to cobalt (Co) and beyond. Cobalt-germanium (Co Ge) and cobalt-molybdenum (Co Mo) alloys show promise for lower contact resistance.

-

Interface modification: Adding monolayers of germanium or other elements at the metal-silicon interface before metal deposition. These seeds create better lattice matching between metal and semiconductor.

-

Silicide engineering: Creating metal-silicide layers (tungsten silicide, cobalt silicide) with optimized stoichiometry and doping. Slight variations in composition can change contact resistance by 20-30%.

-

Graphene and novel materials: Research labs are experimenting with single-layer carbon (graphene) and similar 2D materials as contact facilitators. These are still experimental but show promise.

-

Dopant tuning: Adjusting the doping profile right at the metal-silicon interface to create better band alignment. This can reduce the contact barrier height, allowing easier electron transport.

Production GAA processes typically use aggressive dopant concentrations right at the metal interface (10²⁰ atoms/cm³ or higher) combined with carefully engineered metal alloys. This combination reduces contact resistance from ~10⁻⁵ Ω·cm² (standard tungsten contacts) to ~10⁻⁶ Ω·cm² (advanced co-integrated contacts).

The Interconnect Challenge: Wiring Gets Harder

While transistor optimization gets the headlines, interconnects are equally challenging and less publicized.

At the 3nm node, the smallest metal wires are about 24nm wide. Current must flow through these nanoscale conductors. At these dimensions, surface scattering becomes dominant—electrons colliding with the wire surface lose energy, creating resistance.

Bulk resistivity of copper is about 1.7 µΩ·cm. But a 24nm copper wire doesn't behave like bulk copper. The effective resistivity is 3-4x higher due to surface scattering. This is why advanced fabs are experimenting with surface-treated copper (with atomically smooth surfaces and specific crystal orientations), and even alternative materials like ruthenium and cobalt alloys.

Manganese cobalt (Mn Co) shows interesting properties: lower surface scattering than copper and better diffusion barriers. Ruthenium offers even lower resistivity than copper in narrow dimensions. But both materials have challenges: ruthenium is expensive, and cobalt has reliability issues when used in certain configurations.

Then there's the interconnect isolation problem. Copper wires are surrounded by insulation (dielectrics). The dielectric must have low permittivity (low "k") to minimize capacitive coupling between adjacent wires. Lower capacitance means less energy to charge and discharge the wires, which is a big part of the power budget in modern chips.

Traditional silicon dioxide (Si O₂) has a dielectric constant of about 3.9. Advanced nodes use materials with k values of 2.5-3.0: organosilicates, porous oxide, and exotic fluorinated compounds. Getting k lower than 2.5 is challenging because you lose mechanical stability and thermal properties.

The real cutting-edge work involves ultra-low-k materials with k values around 2.0-2.2. These require innovative material chemistry: graphene-based dielectrics, boron-nitride composites, and other 2D-material hybrids. None of these are in high-volume production yet, but they're being prototyped.

Estimated data shows AI training costs could reduce by 32x over a decade due to efficiency improvements, highlighting the compounding effect of technological advancements.

Yield, Reliability, and Manufacturing Reality

Though it's not glamorous, yield and reliability are what separate viable technology from interesting research.

A GAA transistor's reliability depends on several factors:

- Oxide integrity: The gate oxide and other insulating layers must prevent current leakage for years of operation

- Dopant stability: Dopants must stay where you put them—dopant migration due to electrical stress or thermal cycling is death

- Contact stability: Metal-silicon contacts can degrade, increasing resistance over time

- Electromigration: At high current densities, metal atoms migrate, potentially breaking wires

- Negative bias temperature instability (NBTI): Transistor threshold voltage shifts over time under stress

Advanced materials help with most of these, but introduce new challenges:

- Barrier materials prevent dopant diffusion but can themselves migrate

- Smooth surfaces are more robust than rough ones (fewer defect sites) but more sensitive to damage

- New metal alloys have unknown long-term reliability—there's limited historical data

Chipmakers test these issues aggressively: accelerated life tests at elevated temperature and voltage, electrical stress tests (running transistors hard to see what breaks), and deep analysis of device failures. When a device fails, failure analysis engineers dissect it (literally, slicing it open at microscopic thickness) to understand why.

The current state: GAA reliability is equivalent to mature Fin FET technology. Chips using GAA show the same failure rates and long-term stability. This is a testament to chipmakers' maturity in understanding and controlling these complex systems.

But this parity came at a cost. The yield learning curve for GAA was steep. Early production at TSMC N3 started at 60-70% yield. After process optimization lasting 12-18 months, it reached 85-90%. Getting to 95%+ (the industry target) required another year.

Compare this to Fin FET, where mature processes achieve 95%+ yield routinely. The economic math: you accept lower early yields on new architectures because the performance gain justifies the cost. But there's a time limit—if yields don't improve to 90%+ within 18-24 months, the node becomes commercially unviable.

The Competitive Landscape: Who's Winning the Material Race

There are only a handful of companies with the capability to design and optimize advanced material systems for semiconductor manufacturing. Understanding the competitive dynamics matters because these companies' decisions determine what's possible in future chips.

TSMC leads in production volume. Their N3 process (3nm equivalent) entered production in 2022 and is now high-volume. They've disclosed using selective epitaxy for surface roughness reduction, advanced dopant barriers, and proprietary contact engineering. Their main competitive advantage is the cumulative optimization from shipping millions of wafers. They learn fast and improve quickly.

Samsung is aggressive with material innovation, particularly in metal contacts. They've published extensively on cobalt-based contacts and are exploring molybdenum tungsten alloys. Their 3GAE process uses aggressive material engineering, though it's less proven in volume than TSMC's N3.

Intel, now primarily a design company since outsourcing manufacturing, has partners (TSMC, Samsung, Global Foundries) implementing their process designs. But Intel still does extensive research on next-generation materials through their Portland Technology and Development organization. They're focused on CFET and monolithic 3D, which require new material systems.

Global Foundries and UMC serve customers who can't access cutting-edge TSMC, but their material innovation is more incremental. They optimize existing approaches rather than pioneering new ones.

China's semiconductor ambitions include SMIC and Huawei's Hi Silicon, but neither has demonstrated GAA production at scale. They're focused on catching up to 7nm-5nm equivalents, several generations behind the leading edge.

The material supply chain is surprisingly concentrated. Most advanced precursor chemicals (materials used to deposit new compounds) come from a handful of vendors: Entegris, Cabot, Adeka, and Merck. These companies maintain the highest purity standards and work closely with chipmakers to develop new precursors for new materials.

Evaporation and deposition equipment comes from Applied Materials, Lam Research, and Tokyo Electron. These tool vendors invest heavily in understanding how their equipment interacts with new materials. When a chipmaker develops a new barrier material or contact alloy, the equipment vendor needs to optimize the deposition process to make it viable at scale.

This is why material breakthroughs often require collaboration between chipmakers, equipment vendors, and precursor suppliers. One company can't solve it alone.

Performance Metrics: Quantifying the Gains

When chipmakers announce a new process node, they typically claim 15-20% performance improvements or 40-50% power reductions. What do these numbers actually mean?

Performance improvement is measured in several ways:

-

Logic delay: How fast a signal propagates through a chain of transistors. GAA reduces this by 15-20% compared to enhanced Fin FET at the same voltage.

-

Frequency: Maximum clock speed. At the same power, a GAA chip runs 10-15% faster.

-

Transistor drive current: Current the transistor can provide. This is where the 10-15% improvement shows up—same size transistor, better current.

Power reduction is more nuanced:

-

Dynamic power: Energy consumed while transistors switch. This scales with frequency and voltage squared. Lower voltage means quadratic power reduction. A 10% voltage reduction saves roughly 20% in dynamic power.

-

Leakage power: Energy lost to unwanted current flow. This varies exponentially with voltage and temperature. Leakage improvement from GAA to Fin FET is typically 30-50%.

-

Total power: The combination. Moving to a new process node typically offers 30-40% total power reduction at the same frequency, or 20-30% more performance at the same power.

These aren't trivial gains. In data center chips, a 30% power reduction translates to $100 million+ in electricity savings across the entire data center fleet (for major hyperscalers) over the product's lifetime.

But there's complexity in how these gains are realized. A chip designer can:

- Keep voltage the same and harvest frequency/performance gain

- Keep frequency the same and reduce voltage for power savings

- Use a hybrid approach

Most designs do the hybrid: they reduce voltage by 5-8% (saving roughly 10-15% in dynamic power) and increase frequency by 10-15% (maintaining or slightly increasing performance per watt).

Yield rates for semiconductor manufacturing improve significantly as processes mature. Initial GAA yields are expected to start at 65% and improve to 85% as the process matures. Estimated data.

The AI Training Amplification Effect

Here's something less talked about: the compounding effect of efficiency improvements on AI development costs.

An AI training run consuming X watts of electricity over Y hours has a fixed cost. When you improve chip efficiency by 30% (measured in performance per watt), you can run that same training job in 30% less time, or with 30% less total power. The economic impact is direct and measurable.

But there's a secondary effect: money saved on training infrastructure can fund more training jobs. If a data center operator spends $50 million on training runs per year and can suddenly run 30% more jobs with the same budget, they'll invest in more training. This accelerates AI model development.

This is why chipmakers focus so intently on efficiency: it's not just about power bills, it's about enabling more experimentation, larger models, and faster iteration in AI development.

Consider the math: if training efficiency improves 30% every 18 months (roughly matching transistor-level improvements), then training costs halve every 3 years. Halving costs every 3 years compounded over a decade is a 32x reduction in cost for equivalent training. This is why AGI timelines are frequently revised upward—the capability is improving much faster than expected.

This feedback loop is crucial to understand. Transistor-level improvements → Better chip efficiency → Lower AI training costs → More training → Faster progress → Demand for even better chips. It's self-reinforcing.

Chipmakers are aware they're enabling this acceleration. Whether they view that as good or concerning varies, but the physical reality is undeniable: making transistors more efficient makes AI progress more affordable.

Cost and Accessibility: Who Can Use This Technology

GAA chips are expensive relative to older technology. A 3nm GAA wafer costs roughly 2x what a 7nm Fin FET wafer costs (per unit of useful silicon, accounting for defects).

This has implications for who can access the technology:

Who benefits immediately:

- Cloud providers (Amazon, Microsoft, Google) running AI workloads: efficiency saves millions per year

- Mobile chip companies (Apple, Qualcomm): efficiency enables better performance in power-limited devices

- High-performance computing companies (NVIDIA, AMD) building AI accelerators: performance-per-watt is existential

Who waits for yield improvements:

- Mainstream consumer electronics (TVs, laptops): cost matters more than cutting-edge efficiency

- Automotive chips: reliability matters, so they use proven mature processes

- Industrial chips: cost and availability matter more than performance

Who can't access it:

- Budget smartphone makers: can't afford premium costs

- Developing market manufacturers: don't have access to advanced foundries

- Specialty chip companies: volumes too low to justify the tooling cost

This creates a technology stratification. High-performance chips (servers, flagship phones, data center accelerators) advance quickly with latest nodes. Everything else lags by 2-3 years, using previous-generation nodes or optimized older architectures.

From an AI accessibility perspective, this is significant. The most capable AI chips (using GAA and advanced materials) are concentrated in the hands of major cloud providers. Smaller organizations train models on older chips, which is slower and more expensive per compute unit. This creates a cost advantage for large players.

Future Material Innovations: What's on the Horizon

Beyond the immediate GAA and contact improvements, chipmakers and research institutions are investigating radical material shifts.

Gallium Nitride (Ga N): Already used for power electronics, Ga N offers higher carrier mobility than silicon and better high-frequency properties. Some research groups are exploring Ga N for logic (computing) transistors, not just power management. The challenge: Ga N has a wider bandgap than silicon, which changes how transistors work. It's not a drop-in replacement.

Silicon Carbide (Si C): Similar to Ga N, offers interesting properties for high-speed, high-temperature applications. But again, it's not directly compatible with silicon-based processes. You'd need to develop entirely new manufacturing processes.

2D Materials (Graphene, Mo S₂, etc.): Single or few-layer materials with exotic electronic properties. Graphene has extraordinary conductivity and carrier mobility. Molybdenum disulfide (Mo S₂) can be a semiconductor with a tuneable bandgap. The challenge: controlling these materials at manufacturing scale and integrating them with silicon infrastructure remains unsolved.

III-V Semiconductors (Ga As, In P): Used in specialized RF (radio frequency) and optical applications. Some researchers propose using them for general-purpose logic, but they're difficult to manufacture at scale and don't integrate well with silicon.

The practical reality: radical material shifts are 10+ years away at the earliest. The industry invests billions annually in silicon because they've mastered it. Moving to a fundamentally different material requires overcoming enormous engineering and economic hurdles.

What's more likely in the next 5-7 years: continued optimization within the silicon framework. Better dopant barriers. More exotic contact materials. Improved interconnect alloys. Graphene or 2D materials used in specific applications (perhaps high-frequency interconnects or heat sinks) rather than transistor channels.

The boring reality is often where progress actually happens: incremental, relentless optimization of what already works.

GAA transistors deliver up to 15% better current delivery and reduce leakage power by up to 50% compared to FinFETs. Estimated data based on typical improvements.

Environmental Considerations: The Energy Angle

There's an irony in semiconductor efficiency: making chips more efficient requires building larger, more sophisticated fabs with more complex processes.

A modern 3nm fab costs $20 billion to build and requires enormous amounts of water (for cooling), electricity, and rare materials. The environmental footprint of building and operating such a fab is substantial.

But the flip side: if that fab produces chips that reduce global electricity consumption by 1-2%, the environmental savings quickly exceed the fab's own impact.

Consider: global data center electricity consumption is roughly 1-2% of world electricity usage. A 30% efficiency improvement in data center chips saves roughly 0.3-0.6% of global electricity. That's equivalent to taking 50-100 million cars off the road.

Advanced materials play a direct role here. Each efficiency improvement—from better dopant barriers to smoother surfaces to optimized contacts—directly reduces energy consumption. From a carbon perspective, investing in advanced material research has enormous upside.

There's also the resource angle. Each new generation requires fewer transistors to deliver the same computing power, which means less silicon, less water, less rare materials (though some advanced materials do use rare-earth elements). The trajectory of semiconductor manufacturing is toward using less material while getting more capability.

This doesn't mean the industry is suddenly green. Semiconductor manufacturing is one of the most resource-intensive industrial processes. But the direction is clearly toward efficiency, which has environmental benefits beyond just the end products.

Timeline to the Next Major Shift

Based on current roadmaps and research progress, here's what the next 5-7 years likely holds:

2025-2026: GAA becomes mainstream at the leading edge. All major fabs (TSMC, Samsung, Intel) have mature GAA processes. Yields exceed 90%. Costs remain premium but justified by performance.

2026-2027: First CFET prototypes move to pilot production. Chipmakers begin public announcements about success. Research groups publish papers on next-generation materials for CFET (better thermal conductivity, lower contact resistance at small scale).

2027-2028: CFET enters limited production. Not all chipmakers adopt it immediately. Some stay with optimized GAA for one more generation due to manufacturing risk. New advanced materials (cobalt-based contacts, novel dielectrics) become routine.

2028-2029: CFET becomes primary architecture at the leading edge. Monolithic 3D (stacking multiple transistor layers) reaches proof-of-concept. The industry starts discussing what comes after CFET.

2029-2030: Stacked CFET research accelerates. Material requirements become even more demanding. Industry conferences overflow with papers on thermal management, reliability, and material engineering for 3D structures.

Beyond that: too uncertain. The physics is known, but the engineering hasn't been proven. What's certain: continued reliance on advanced materials, continued focus on efficiency, and continued pressure from AI driving demand for higher performance and lower power.

The Human Element: Materials Science is a Talent Challenge

Here's something rarely discussed: all this material innovation requires people. Specialists in materials characterization, process chemistry, device physics, and failure analysis.

These are difficult roles to fill. Materials science is no longer a core academic discipline—most universities don't have strong materials programs. Engineers trained in materials physics often move to other industries (aerospace, automotive, pharmaceuticals) where there's less pressure and more flexibility.

Chipmakers have responded by creating intensive in-house training programs. TSMC runs one of the world's largest semiconductor university programs. Samsung invests heavily in R&D talent. Intel maintains research partnerships with leading universities.

But there's a brain drain happening. As chip manufacturing moves beyond raw processing to materials engineering, the talent requirement shifts from process engineering (relatively common) to materials science (much rarer). Companies compete aggressively for the same small pool of experienced materials scientists.

This is a genuine constraint on how fast the industry can innovate. You can build fabs, you can design transistors, but you can't easily find or train enough experts in exotic materials to deploy them at scale.

China is aware of this. Part of their semiconductor strategy involves recruiting materials science talent globally (sometimes through controversial means). The US has responded with restrictions on hiring foreign talent and technology transfer. This geopolitical dimension affects semiconductor progress more than most observers realize.

Synthesis: Why This All Matters Together

GAA transistor design is elegant, but it's not the whole story. The real breakthrough is the systems approach: marrying architectural innovation (gate-all-around) with material science breakthroughs (dopant barriers, contact engineering, interconnect improvements) and manufacturing optimization (yield, reliability, thermal management).

When all these elements work together, you get chips that are 30-40% more efficient than the previous generation. This efficiency isn't distributed equally—you get massive gains in power efficiency (30-50% reduction), decent gains in performance (10-15% increase), and modest improvements in density (10-20% more transistors per unit area).

For AI specifically, this matters enormously. Training costs decrease. Inference costs decrease. More experiments become economically viable. Progress accelerates.

For consumers, it means better battery life in phones, better gaming performance in laptops, and more capable AI features in everyday devices—all without proportional increases in heat or power consumption.

For industry, it means the path forward is clear: continue down the road of advanced materials, continue optimizing transistor architecture, continue perfecting manufacturing. There are no easy paths, no silver bullets, but the direction is well-defined.

Moore's Law didn't die. It transformed. Instead of just shrinking transistors, we're architecting them better and filling them with better materials. The results are similarly impressive, just achieved through different means.

The next few years will determine who leads this next wave of semiconductor progress. TSMC is executing well. Samsung is innovating aggressively. Intel is reorganizing to stay competitive. Smaller fabs are making strategic choices about which nodes to support. And the material supply chain is humming with activity to support it all.

The age of gate-all-around design isn't a single breakthrough. It's a system. And systems are harder to understand but more powerful than any single innovation.

FAQ

What is gate-all-around (GAA) transistor design?

Gate-all-around transistor design is an architecture where the gate material completely surrounds the silicon channel on all sides, rather than contacting it from just three sides as in Fin FETs. This cylindrical gate geometry provides superior electrostatic control, allowing the gate electric field to penetrate the channel uniformly. The result is better performance at lower power levels compared to conventional Fin FET designs.

How does GAA improve performance compared to Fin FET?

GAA improves performance primarily through stronger electrostatic coupling between the gate and the channel. With better gate control, engineers can operate transistors at lower voltages while maintaining the same switching speed, or increase speed at the same voltage. In practice, GAA transistors deliver 10-15% better current delivery and 30-50% lower leakage power compared to optimized Fin FETs at similar dimensions.

Why are advanced materials necessary for GAA technology?

While GAA solves gate control problems, it moves the bottleneck to channel resistance and contact resistance. Advanced materials address this through several mechanisms: dopant barriers prevent unwanted diffusion that degrades performance, engineered surfaces reduce electron scattering, and specialized metal alloys reduce resistance at metal-silicon contacts. Without these material innovations, the performance gains from GAA architecture alone would be 50% smaller.

What role does dopant diffusion play in transistor performance?

Dopants are impurities added to silicon to improve conductivity in source and drain regions. However, dopants can diffuse beyond their intended regions, seeping into the channel where they increase resistance and create performance variability. In GAA transistors with tight dimensions, this problem is much worse. Advanced barrier materials inserted between source/drain and channel prevent this unwanted diffusion, maintaining device performance and consistency across the chip.

How do advanced materials reduce contact resistance?

Contact resistance appears where metal connects to silicon. As transistors shrink, this resistance becomes proportionally larger. Advanced materials address this through three mechanisms: selective dopant engineering at the interface to improve band alignment, using metal alloys with better contact properties than traditional tungsten, and inserting intermediate layers that facilitate electron transport. These approaches can reduce contact resistance by 40-60% compared to conventional contacts.

What is CFET and when will it appear in production?

CFET (complementary FET) is the next architectural evolution, stacking n-channel and p-channel transistors vertically rather than placing them side-by-side. This provides 2-3x density improvement without shrinking horizontal dimensions. CFET is expected to appear in limited production around 2027-2029, depending on the manufacturer and their risk tolerance. TSMC and Samsung have both demonstrated working prototypes.

How does AI demand affect semiconductor material innovation?

AI workloads are extraordinarily energy-intensive, driving economic pressure for more efficient chips. Training a state-of-the-art AI model can cost millions in electricity alone. Each percentage point of efficiency improvement translates to millions in cost savings at scale. This directly funds material science research and justifies the investment in complex manufacturing processes needed to deploy new materials at scale.

What are the yield and reliability challenges with GAA technology?

GAA introduces manufacturing complexity that impacts yield (the percentage of working chips from a wafer). Early GAA production achieved 60-70% yield, improving to 85-90% after 12-18 months of optimization. New advanced materials add additional variability—some materials can migrate over time, and long-term reliability data is limited. Current data suggests GAA reliability matches mature Fin FET technology, but this required extensive testing and process optimization.

Why do contact materials matter for future chip performance?

As transistors shrink, contact resistance becomes the dominant limiting factor in device performance. A single transistor might have contact resistance of 50-70% of total resistance. Moving from tungsten contacts (~10⁻⁵ Ω·cm²) to advanced cobalt-based contacts (~10⁻⁶ Ω·cm²) provides 10x reduction in contact resistance, enabling better current delivery and lower power consumption. This directly translates to 5-10% performance improvements in end products.

What environmental benefits do more efficient chips provide?

Data centers consume 1-2% of global electricity. A 30% efficiency improvement in data center chips reduces that consumption by 0.3-0.6% globally—equivalent to removing 50-100 million cars from roads in terms of carbon impact. At the device level, more efficient chips mean longer battery life and lower heat generation, reducing cooling requirements. These environmental benefits exceed the manufacturing impact of advanced fabs within 2-3 years of operation.

How is the semiconductor material supply chain organized?

The supply chain involves three key layers: chipmakers (TSMC, Samsung, Intel) design and produce chips using new materials; equipment vendors (Applied Materials, Lam Research) develop tools to deposit and pattern new materials; and precursor suppliers (Entegris, Cabot) provide ultra-high-purity chemical inputs. Breakthroughs typically require collaboration between all three layers, as a new material requires compatible deposition processes and precursor chemicals that don't yet exist at manufacturing scale.

Conclusion: The Material Future of Computing

We've reached an inflection point in semiconductor history. The era of predictable, incremental shrinking is over. What's replacing it is more sophisticated, more materially complex, but ultimately more powerful.

Gate-all-around transistor design is real, it's in production, and it's working. Chips based on GAA are shipping in billions of devices. But GAA alone would deliver underwhelming results without the material innovations that accompany it.

The real story is the marriage of architectural innovation with materials science. Dopant barriers, engineered contacts, optimized interconnects, and novel dielectrics aren't supporting actors. They're essential to making the whole system work.

For AI, this matters profoundly. Every efficiency improvement compounds. Lower training costs enable more experimentation. More experimentation accelerates progress. The feedback loop is self-reinforcing. Transistor-level improvements directly enable AI capability growth.

The next five years will be defined by chipmakers mastering GAA manufacturing and beginning the transition to CFET. For materials scientists and process engineers, this is the best time in decades to work on semiconductor advancement. The industry is investing billions. The problems are solvable. The timeline is compressed.

For companies building AI systems, the implication is clear: next-generation chips will deliver transformative efficiency improvements. Plan for it. The hardware you design with today will feel slow and inefficient in three years as new material-driven optimizations hit production.

The age of material science in semiconductors isn't beginning—it's already here. But it's far from peak. The discoveries ahead will dwarf what we've done so far. And unlike the era of pure silicon scaling, the potential appears nearly unlimited.

That's the real story behind the gate-all-around revolution.

Key Takeaways

- Gate-all-around transistors wrap gates completely around the silicon channel, providing 30-40% better electrostatic control than FinFETs

- Advanced materials are essential: dopant barriers prevent diffusion, engineered surfaces reduce scattering, specialized metal alloys minimize contact resistance

- GAA delivers 10-15% better current delivery and 30-50% lower leakage power compared to optimized FinFET designs

- The AI boom drives chip efficiency innovation, creating economic pressure for lower power consumption and better performance-per-watt

- CFET (complementary FET) and monolithic 3D stacking represent the next major architectural shift, expected 2027-2029

- Manufacturing maturity and material supply chain talent are the real bottlenecks limiting speed of innovation, not physics

- Efficiency improvements compound: lower training costs enable more AI experimentation, accelerating progress in a self-reinforcing cycle

Related Articles

- US 25% Tariff on Nvidia H200 AI Chips to China [2025]

- Trump's 25% Advanced Chip Tariff: Impact on Tech Giants and AI [2025]

- RAM Price Hikes & Global Memory Shortage [2025]

- OpenAI's $10B Cerebras Deal: What It Means for AI Compute [2025]

- AMD Instinct MI500: CDNA 6 Architecture, HBM4E Memory & 2027 Timeline [2025]

- Lenovo Tech World at CES 2026: Live Coverage from Las Vegas [2026]

![Gate-All-Around Transistors: How AI is Reshaping Chip Design [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/gate-all-around-transistors-how-ai-is-reshaping-chip-design-/image-1-1768660959921.jpg)