Introduction: The Structural Shift Nobody Wanted to Talk About

Your next SSD won't be cheaper. In fact, you should probably buy one now if you've been procrastinating. And I'm not talking about the typical seasonal price swings that tech enthusiasts obsess over. This is different.

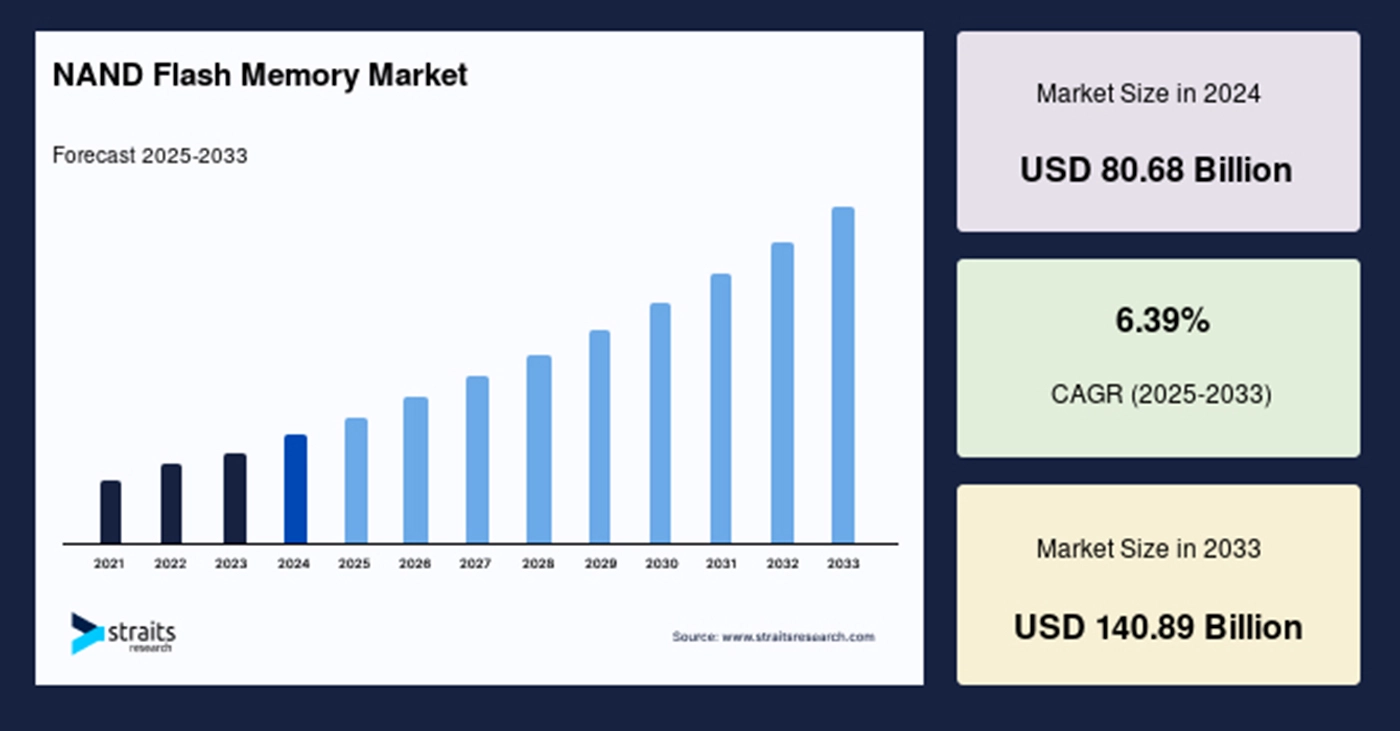

The storage industry is experiencing something that doesn't happen often: a structural market shift. Not a temporary shortage, not a cyclical downturn—but a fundamental reordering of how storage components are manufactured, supplied, and priced. The culprit? Artificial intelligence. Specifically, the insatiable appetite of AI data centers for high-capacity SSDs with premium NAND components.

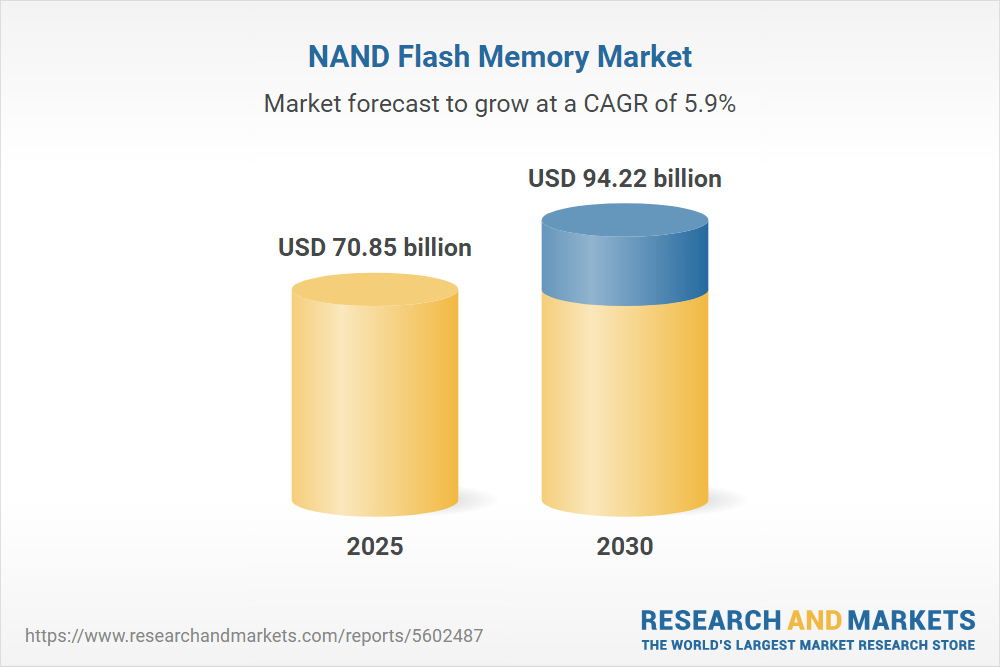

For years, NAND flash pricing followed predictable patterns. Oversupply would tank prices. Undersupply would spike them. But the market would eventually normalize. That playbook is breaking down. Recent analysis from TrendForce, one of the semiconductor industry's most reliable forecasters, reveals something startling: inventory levels no longer control NAND pricing. Supply strategies do.

Memory manufacturers have fundamentally altered their approach to NAND production. They're not racing to expand capacity anymore. Instead, they're deliberately limiting bit output growth while investing in higher-layer architectures, QLC technology, and advanced manufacturing processes. This isn't a temporary adjustment. It's a strategic pivot that's likely to persist for years.

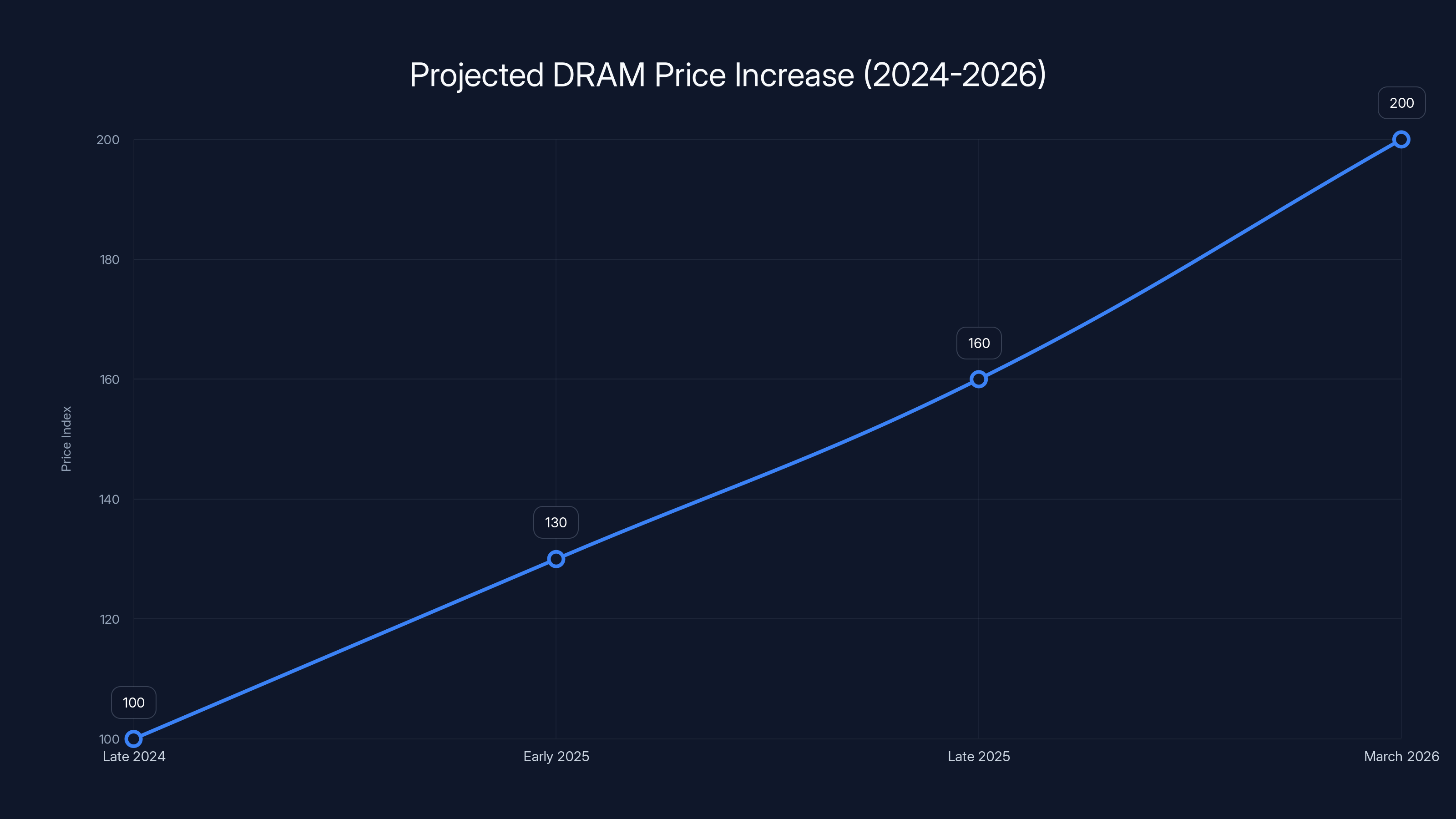

What does this mean for you? Whether you're building a workstation, upgrading your gaming rig, or provisioning enterprise storage, SSD prices are entering a phase of sustained elevation. The days of waiting for prices to bottom out are over. Worse, this mirrors the DRAM market disruption that started in late 2024, except the storage market dynamics suggest the pressure could be even more durable.

Let's break down why this is happening, what it means for the industry, and what you should actually do about it.

TL; DR

- NAND pricing is structurally broken: Inventory management no longer controls prices; supply strategy and manufacturing capacity do

- AI is the culprit: Enterprise storage for AI infrastructure and data centers is absorbing massive volumes of high-capacity SSDs

- Bit growth is deliberately limited: Manufacturers are investing in higher-layer NAND and QLC rather than raw capacity expansion

- Consumer markets are weakening: Smartphone and notebook demand is declining, removing the offsetting demand that historically stabilized pricing

- Expect sustained price elevation: Unlike previous cycles, prices may not normalize downward even when temporary imbalances fade

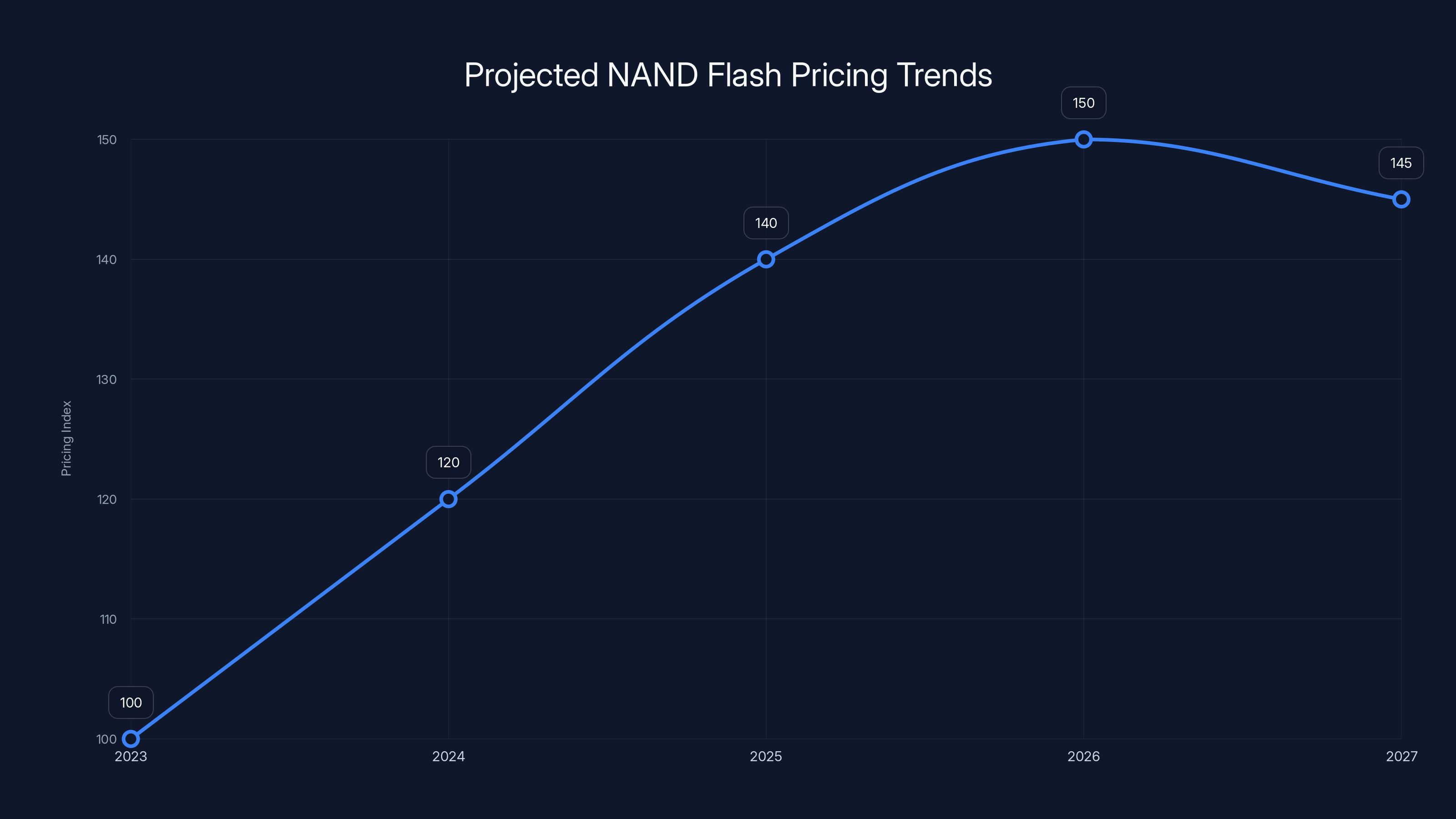

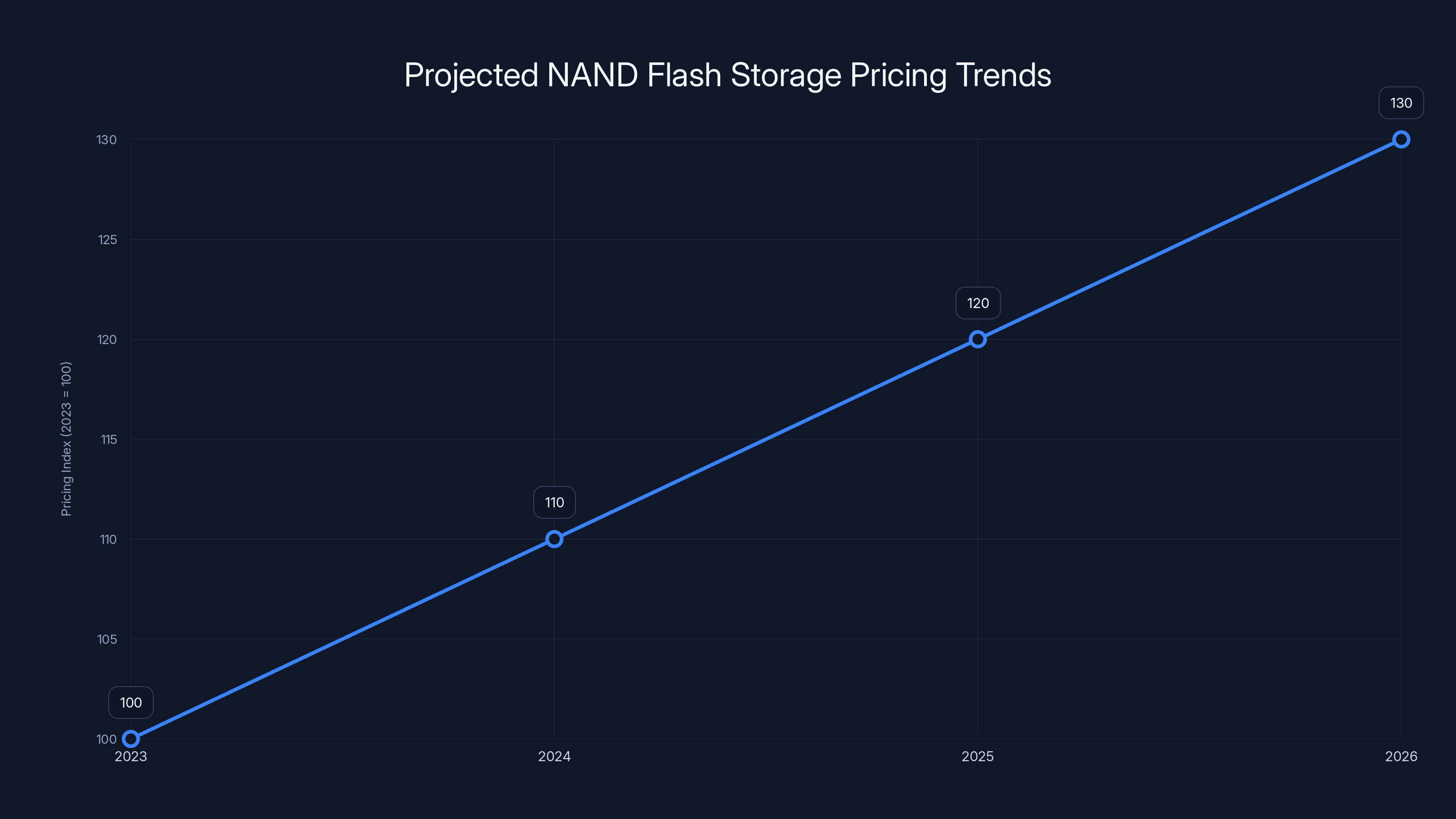

NAND flash prices are projected to rise through 2026 due to AI infrastructure demand and manufacturing constraints, with potential slight normalization by 2027. Estimated data.

Understanding NAND Flash Technology and Market Structure

What Exactly Is NAND Flash and Why Should You Care?

NAND flash is the memory technology powering every solid-state drive you've ever used. It's not the RAM in your laptop or the cache in your processor. It's persistent storage, meaning it retains data even when powered off.

The architecture matters more than you'd think. NAND flash is arranged in layers—think of it like apartment buildings stacked on top of each other. Single-layer cells (SLC) are like penthouses with one apartment per floor: incredibly fast and reliable, but expensive. Multi-layer cells (MLC, TLC, QLC) cram more units into the same footprint. QLC is the current frontier, fitting four bits of data into each cell. Each generation allows manufacturers to squeeze more storage into the same physical space.

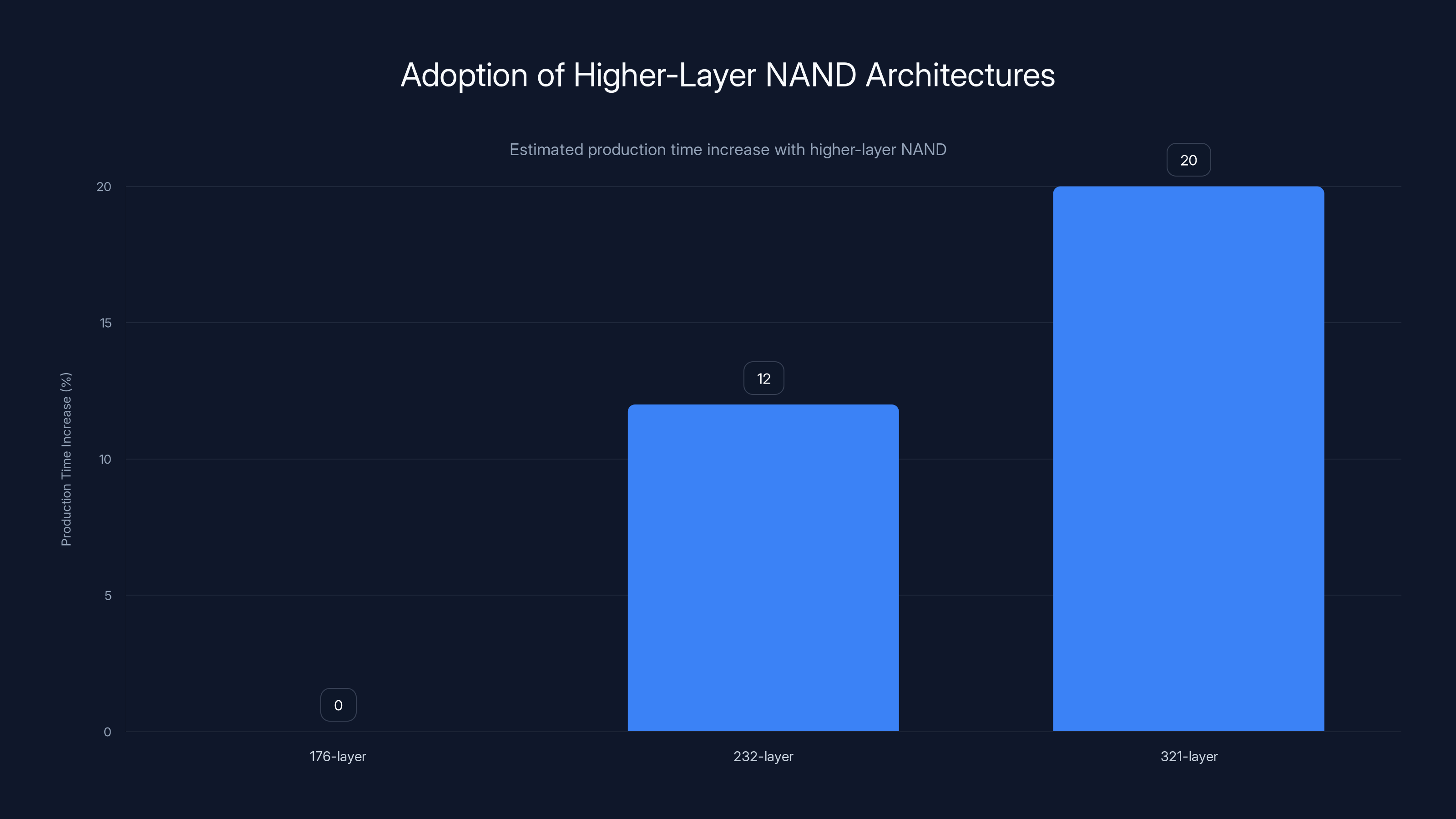

But here's what's crucial: higher-layer NAND requires more complex manufacturing processes. It's slower to produce. It demands more precision. When manufacturers shift from, say, 176-layer TLC to 232-layer QLC, they're not just upgrading their equipment—they're fundamentally restructuring their production workflow.

The Traditional NAND Pricing Cycle

Historically, NAND pricing worked like this: when demand outpaced supply, prices spiked. Manufacturers saw the margin opportunity and expanded capacity aggressively. New fabs came online. Production ramped up. Oversupply crashed prices. Margins compressed. Manufacturers cut capex. Supply tightened. Demand recovered. Cycle repeats.

It was predictable enough that industry participants could model it, hedge against it, and plan around it. Consumers actually benefited. When you waited six months to buy an SSD, you'd often save 15-20% just by letting the cycle run its course.

That dynamic is evaporating.

How AI Fundamentally Changed Storage Demand

The Unprecedented Appetite for Enterprise Storage

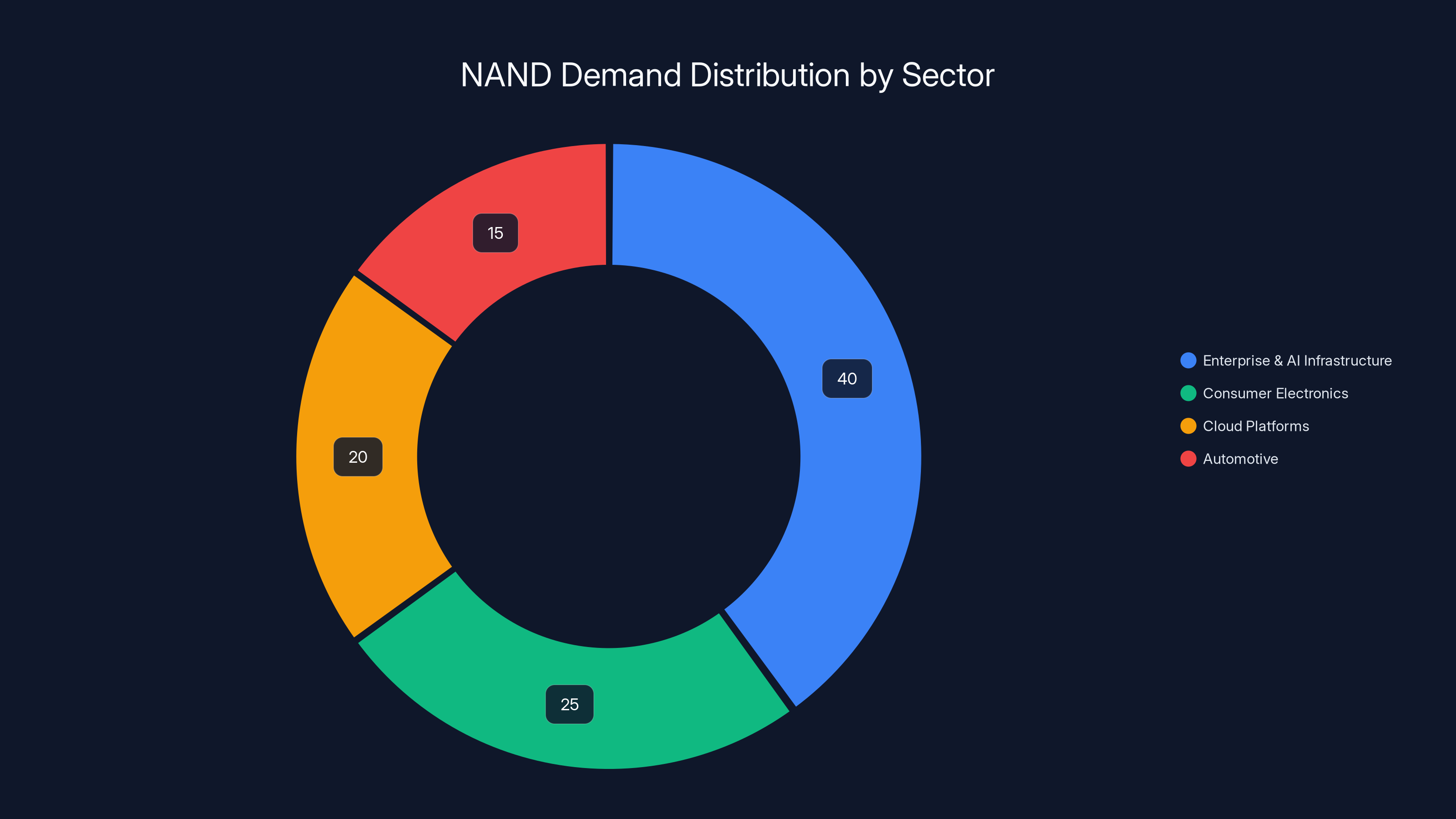

AI data centers don't buy a few SSDs. They buy them by the thousands. A single large language model training facility might consume petabytes of storage. Inference clusters need fast, reliable storage for model weights and intermediate computations. Retrieval-augmented generation systems require massive vector databases. Every major cloud provider is racing to expand their storage capacity to support AI workloads.

What makes this different from previous demand surges? Traditional enterprise storage cycles were spread across multiple quarters or years. Individual organizations would upgrade gradually. AI infrastructure buildout is happening at scale across dozens of companies simultaneously.

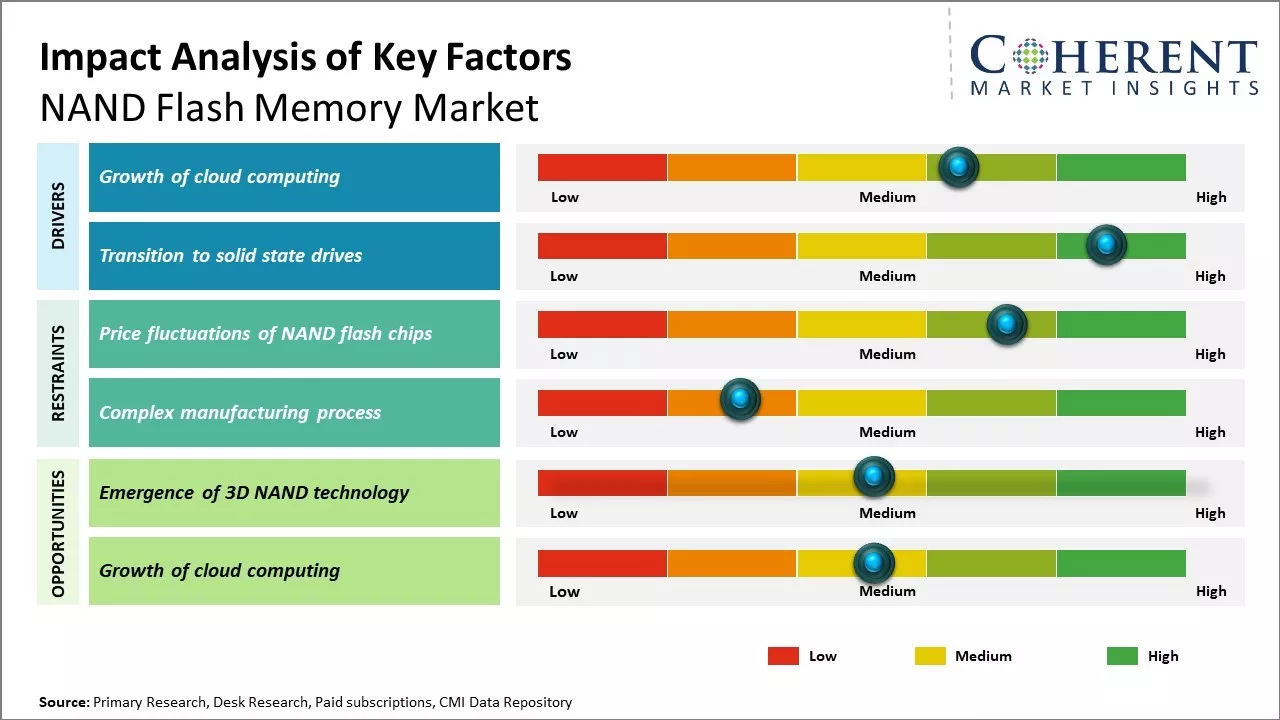

According to industry analysis, AI infrastructure is now the primary driver of NAND flash demand revisions. Companies like OpenAI, Anthropic, Meta, Google, and countless enterprise customers are all provisioning storage at the same time. This doesn't behave like normal demand elasticity. It's structural.

Why AI Workloads Demand Different Storage

AI training and inference clusters have specific storage requirements that differ from traditional servers. Models are constantly being updated. New training runs require rapid access to massive datasets. Fine-tuning operations need parallel I/O throughput that conventional storage can't provide.

This drives demand toward higher-capacity SSDs with premium NAND components. You can't train models efficiently on older, slower storage technologies. The entire economic model of AI compute relies on high-bandwidth storage that keeps GPUs and TPUs fed with data. Storage becomes a bottleneck quickly, so infrastructure builders overprovision intentionally.

The result? AI data centers are absorbing disproportionate volumes of the highest-quality NAND available. The enterprise server market, cloud storage platforms, and edge computing deployments are all competing for the same supply pool. Consumer markets—smartphones, laptops, budget SSDs—are deprioritized.

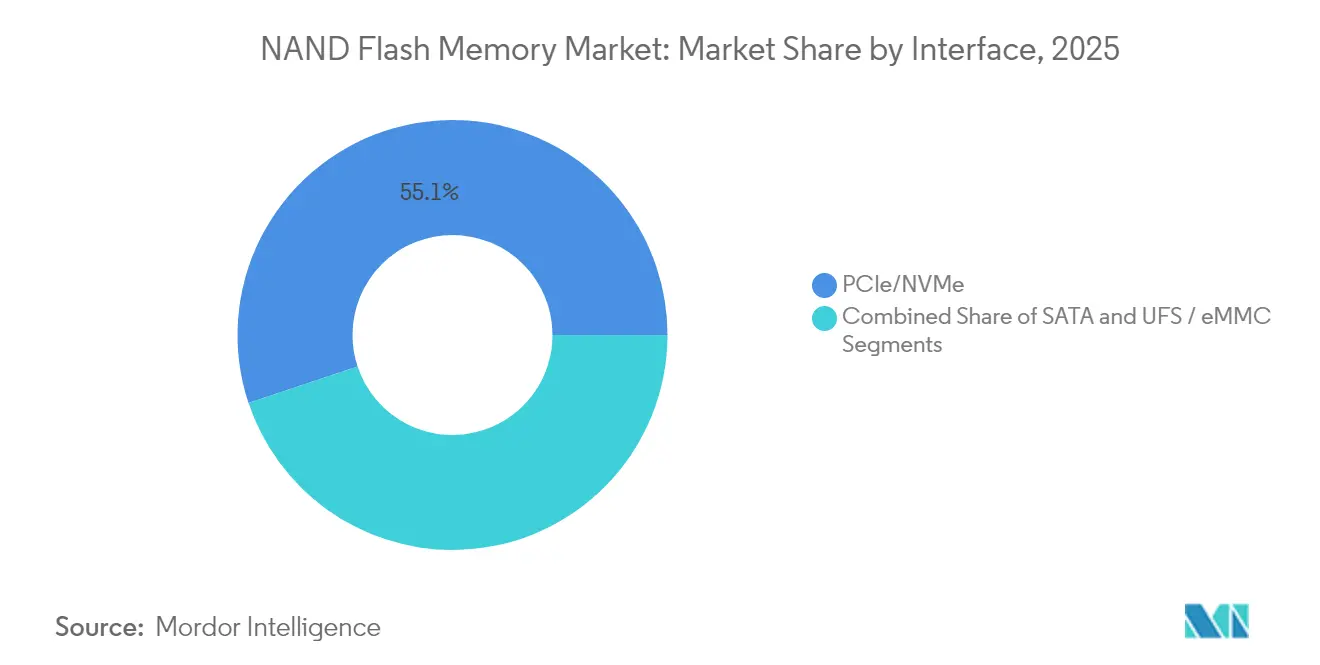

Enterprise and AI infrastructure sectors dominate NAND demand, accounting for 40% of the market, while consumer electronics face declining demand. Estimated data.

The Supply Strategy Pivot: Why Manufacturers Aren't Just Building More

Capital Expenditure Without Capacity Growth

Here's what's counterintuitive: memory manufacturers are investing more money than ever. Their capex budgets are historically high. Yet they're producing fewer total bits.

This seems backwards until you understand where the money is going. Most new investment is flowing into advanced manufacturing technologies: hybrid bonding techniques, higher-layer architectures, next-generation process nodes. These technologies improve efficiency and enable denser storage, but they don't directly translate to higher bit output.

Manufacturers are making a strategic calculation. They could build more conventional fabs, expand cleanroom space, and churn out additional NAND capacity. But the return on investment would be questionable. If demand eventually softens—as it inevitably does in technology cycles—they'd be sitting on excess capacity with depressed margins.

Instead, they're betting on premium NAND commanding premium prices. Higher-layer NAND. QLC adoption across enterprise products. Process optimization that improves yields without multiplying capacity. This strategy maximizes profit per bit, not profit per fab.

The Cleanroom Constraint Nobody Talks About

Physical constraints matter more than most people realize. Building a semiconductor fab isn't like opening a factory. It requires specialized cleanroom infrastructure that takes years to construct. The supply of experienced fab operators is limited. Equipment manufacturers have bottlenecks in their own production.

Even when capex budgets are unlimited, manufacturers hit hard walls. You can't magically produce more cleanroom space. You can't instantly train thousands of new process engineers. These constraints exist independent of demand or pricing signals.

What manufacturers can do is optimize existing capacity. Run longer shifts. Implement more aggressive yield improvements. Shift product mix toward higher-margin components. Gradually migrate to next-generation processes that fit more bits into existing fabs.

This is precisely what's happening now. Capacity expansion is constrained not by capital but by physical and human infrastructure limits. Suppliers are hitting those walls simultaneously, which means the supply growth rate won't increase meaningfully even if pricing incentives soar.

Demand Divergence: Where NAND Growth Is Actually Happening

Enterprise and AI Infrastructure: The New Demand Anchor

Demand patterns across NAND markets are fractured. Enterprise storage, AI infrastructure, and cloud platforms are absorbing inventory voraciously. Meanwhile, consumer demand is softening.

Smartphone shipments are declining. Notebook sales are weak. Gaming laptop demand, historically a steady NAND consumer, is depressed. These segments are facing downward revisions precisely because rising memory costs are pressuring device margins. A manufacturer can't raise smartphone prices 15% to offset higher NAND costs without losing market share to competitors.

But enterprise customers? They don't have the same price elasticity. If your data center needs 10,000 SSDs to support AI infrastructure, you can't defer the purchase or switch to a cheaper alternative. You need the storage to function. Pricing flexibility is minimal.

This creates a seller's market in enterprise NAND. Manufacturers can direct premium components toward enterprise customers first, knowing consumer demand will take whatever remains. This structural imbalance reinforces pricing power in the high-end segments while depressing pricing in consumer segments.

The divergence matters because historically, consumer demand provided a counterweight. During enterprise cycles, consumer demand would eventually stabilize pricing. That stabilizing force is weakening.

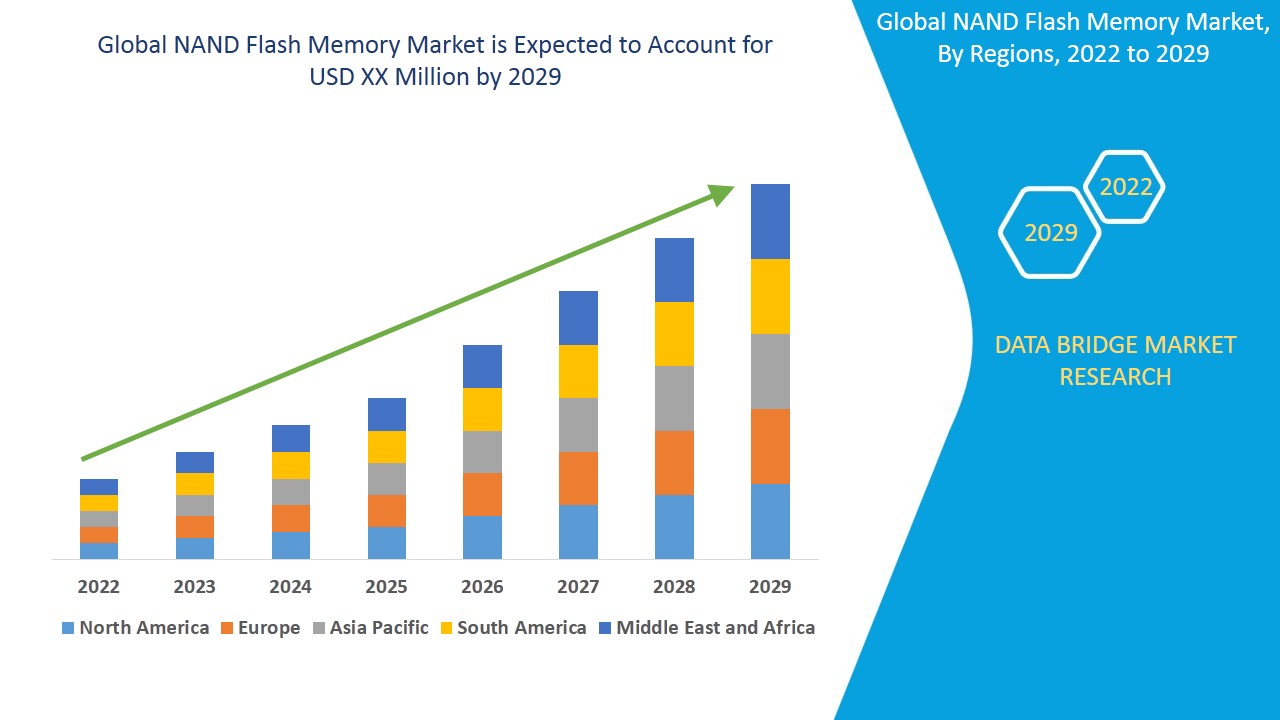

Geographic and Sectoral Variation

Not all storage demand is equal. Chinese smartphone manufacturers face different cost pressures than Apple. Japanese automotive manufacturers have different supply chain priorities than North American cloud providers. European enterprises have different compliance and supply chain requirements.

But the AI infrastructure buildout is notably global and concentrated among a handful of dominant players. This concentration actually increases pricing power. When demand comes from a diverse, fragmented customer base, individual sellers have less leverage. When demand comes from a small number of well-capitalized customers who must upgrade on similar timelines, pricing can move significantly.

DRAM as the Cautionary Tale: What Happened and What It Means

The 2024-2025 DRAM Price Spike

If you want to understand where NAND is headed, watch the DRAM market. Starting in late 2024, DRAM prices began accelerating upward. Industry analysis predicted prices could nearly double by March 2026. This wasn't caused by supply shortages in the traditional sense. It was caused by the same structural shift we're seeing with NAND: manufacturers deliberately limiting capacity expansion despite rising demand.

DRAM manufacturers discovered that investing in HBM (high-bandwidth memory) and advanced nodes is more profitable than expanding conventional memory capacity. HBM is essential for AI accelerators. Advanced nodes are essential for data center processors. So manufacturers shifted focus from commoditized DRAM toward premium, high-margin products.

Consumer and midmarket customers faced a dilemma. DRAM prices weren't temporary spikes they could wait out. Prices kept rising because supply growth remained constrained. System builders eventually passed costs to end users. Some did it explicitly. Others absorbed margin compression. Either way, the dynamics were permanent.

Why NAND Could Follow the Same Path

The DRAM playbook is replicating in the NAND market, but with even more structural pressure. Here's why NAND could experience even more durable price elevation:

First, NAND is more capital-intensive than DRAM. Building fab capacity is more expensive and time-consuming. The barriers to rapid scaling are higher.

Second, the technical complexity of advanced NAND is increasing faster. Transitioning to next-generation processes requires new equipment, new materials, new manufacturing techniques. Suppliers of fab equipment can't keep up with demand. This creates genuine supply bottlenecks on the equipment side, independent of manufacturer strategy.

Third, NAND markets are more fragmented than DRAM. There are more suppliers, more product variants, more niche use cases. This fragmentation actually makes pricing more durable because there's less direct price competition in specific segments.

If DRAM prices were elevated by 50-100% through 2026, and NAND experiences similar dynamics, we're looking at a multi-year period of sustained pricing pressure. Unlike previous cycles, waiting for prices to normalize might not work.

DRAM prices are projected to nearly double by March 2026 due to strategic shifts in manufacturing priorities. Estimated data based on industry trends.

Higher-Layer NAND and QLC Adoption: The Strategic Shift

Why Manufacturers Are Investing in Higher Layers

The industry is shifting from conventional three-dimensional NAND toward four-dimensional NAND with dramatically increased layer counts. Current production includes 176-layer, 232-layer, and emerging 321-layer architectures. This vertical stacking allows manufacturers to fit exponentially more storage into the same footprint.

But here's the trade-off: higher-layer NAND is slower to produce. Each layer adds process complexity, yield challenges, and time to completion. Moving from 176 layers to 232 layers doesn't just increase output by 31 percent. It typically increases production time by 10-15 percent while also requiring process optimization work that consumes engineering resources.

Manufacturers are accepting this trade-off because higher-layer NAND commands premium prices. Enterprise customers pay more for denser, more efficient storage. Data centers optimize for capacity per watt and capacity per rack unit, making higher-layer NAND valuable even at price premiums.

QLC as a Strategic Lever

QLC (quad-layer cell) technology stores four bits per cell instead of three (TLC). Theoretically, this should reduce per-gigabyte costs. In practice, QLC is slower and degrades faster than TLC. Consumer SSDs using QLC require sophisticated error correction and thermal management.

QLC adoption is increasing, but not as rapidly as it could. Why? Because manufacturers and system designers recognize that flooding the market with cheap QLC SSDs would collapse margins. Instead, QLC is being positioned strategically: enterprise SSDs where performance requirements can be met with existing QLC technology, consumer drives where QLC offers acceptable performance, and avoiding segments where TLC is still optimal.

This segmentation strategy maintains pricing power. Rather than cannibalizing TLC with cheaper QLC, manufacturers use QLC to improve overall profitability by selling the right technology to the right segment.

Market Inventory Dynamics: The New Reality

Why Inventory No Longer Controls Pricing

Traditional NAND markets operated on inventory-driven pricing. When channel inventory rose above historical norms, prices fell. When inventory depleted, prices rose. This relationship was fairly predictable. Distributors and system builders could forecast pricing by tracking inventory levels from industry reports.

That relationship has weakened substantially. Current analysis shows inventory levels are a poor predictor of forward pricing. Why? Because supply strategies have changed. Manufacturers are controlling output deliberately, independent of inventory signals. When inventory is high, they simply reduce production further. When inventory is low, they increase prices without expanding output.

This is a shift from capacity-driven to demand-driven market dynamics. Instead of inventory equilibrating price through supply and demand mechanics, pricing is set through direct negotiation and contract terms between manufacturers and large enterprise customers.

Small customers—retail buyers, mid-sized businesses, small OEMs—are left with whatever supply remains after enterprise customers take their allocation. This segregated market structure prevents traditional inventory-based pricing mechanisms from functioning.

Contract Pricing and Its Implications

Large enterprise customers lock in pricing through quarterly or annual contracts. These contracts typically specify volume, pricing, and delivery schedules. Current contracts reflect the structural shift: pricing is higher and likely to remain elevated, with limited downside risk for manufacturers.

When contracts are renegotiated, do prices fall? Historically, yes. Manufacturers would offer lower prices to secure volume commitments for the next quarter. Current dynamics suggest that won't happen this cycle. Demand is too strong, supply is too constrained, and manufacturers have too much leverage.

For retail buyers and smaller customers, this matters profoundly. Pricing at your local retailer reflects whatever spot market pricing is available after enterprise allocations. In a supply-constrained market with strong enterprise demand, spot pricing stays elevated.

The Divergence Between Consumer and Enterprise Demand

Why Consumer Markets Are Struggling

Personal computer markets have matured. Upgrade cycles have lengthened. Storage capacity per device has increased, so total demand growth is slower than historical rates. Meanwhile, memory costs (both NAND and DRAM) have risen substantially.

Consumer device manufacturers—laptop makers, gaming companies, OEMs building prebuilts—face a margin squeeze. They can't raise prices 20% because storage costs rose 30%. Consumers won't accept that. So they either absorb margin compression or reduce storage capacity.

Many have done both. Cheaper laptops now ship with smaller SSDs. Gaming laptops include larger drives but are increasingly expensive. Budget devices sacrifice storage speed to hit price points.

This demand destruction is deliberate, in a sense. The market is reallocating storage to higher-value segments rather than increasing overall consumption. Enterprise and AI infrastructure represent higher-value uses of NAND. Consumer electronics represent lower-value uses. Market forces push production toward higher-value segments.

The Smartphone Storage Plateau

Smartphones hit a painful inflection point. Base storage capacity in flagship phones is 256GB or 512GB. Users rarely need more. Upgrade motivation is weak. Meanwhile, smartphone shipment growth has flattened globally.

This removes a historical demand anchor. Smartphones once consumed enormous volumes of NAND. Annual smartphone shipments in the 1.2-1.5 billion unit range meant consistent, growing demand for storage. That growth has stopped.

Manufacturers historically balanced weak PC demand with strong smartphone demand. That cushion is gone. When PC demand slumps, overall NAND demand is genuinely constrained.

Projected data indicates a steady increase in NAND flash storage pricing due to persistent demand from AI infrastructure and limited supply growth. Estimated data.

Manufacturing Complexity and Equipment Constraints

The Fab Equipment Bottleneck

Building NAND capacity requires specialized equipment: lithography systems, etch tools, deposition systems, and testing equipment. These tools are manufactured by a handful of suppliers—ASML, Applied Materials, and a few others. These equipment suppliers have their own capacity constraints.

When multiple NAND manufacturers want to expand simultaneously, equipment suppliers can't meet demand. Lead times on new lithography equipment stretch to 18-24 months. Customization delays add further time. This creates a hard ceiling on how fast manufacturers can scale production, independent of capital availability.

Current dynamics show equipment suppliers are already running at near-maximum capacity. NAND manufacturers are ordering equipment for future deployments, but delivery is constrained. This suggests capacity expansion will be paced by equipment availability, not by capital or market demand.

Process Optimization vs. Capacity Expansion

When manufacturers can't easily expand capacity, they optimize existing processes. Improved yields mean more usable bits from the same fab floor. Faster cycle times mean more complete production runs per unit time. Better thermal management improves reliability.

These optimizations are real and valuable, but they have limits. You can't achieve 30% yield improvement indefinitely. You can't continuously reduce cycle times without hitting physical limitations. At some point, further optimization requires new equipment or new manufacturing techniques.

Manufacturers are currently in the "optimization" phase. They're wringing efficiency gains from existing fabs. But this strategy has a limited runway before hitting diminishing returns.

Investment Priorities: HBM, Advanced Nodes, and Higher-Layer NAND

HBM as the Strategic Priority

High-bandwidth memory is essential for AI accelerators and high-performance computing. It's also expensive and difficult to manufacture. DRAM manufacturers are prioritizing HBM capacity over conventional memory because it commands premium pricing and enables AI infrastructure buildout.

This shift is deliberate. Manufacturers could produce more conventional DRAM or standard NAND. Instead, they're prioritizing technologies with the highest margin and greatest strategic importance. This reinforces pricing pressure on conventional products.

The same dynamic is playing out in NAND. Advanced process nodes (3D NAND with higher layer counts, hybrid bonding technologies) are priorities. Conventional capacity expansion is secondary.

Capital Allocation and Its Limits

Memory manufacturers are capital-constrained not by financial resources but by execution capacity and equipment availability. They have cash. What they lack is the ability to build fabs faster, train engineers faster, and deploy equipment faster.

This execution bottleneck means capex increases don't translate linearly to capacity increases. A 20% increase in capex might yield only a 5-10% increase in bit output. The returns diminish because underlying physical constraints can't be overcome with capital alone.

This reality is critical to understanding why pricing pressure is durable. Even with virtually unlimited capex, manufacturers can't expand supply fast enough to relieve pricing pressure in the near term.

Forward-Looking Analysis: When Will Prices Normalize?

The Multi-Year Outlook

Based on current manufacturing strategies and demand trajectories, structural pricing pressure likely persists through 2026 at minimum. AI infrastructure demand shows no signs of weakening. Enterprise storage buildouts are accelerating. Consumer demand remains depressed.

For prices to meaningfully decline, several things would need to happen simultaneously:

- AI data center buildouts would need to slow significantly

- Consumer demand would need to recover materially

- Manufacturers would need to complete capacity expansion projects currently underway

- Inventory levels would need to rise above historical norms

None of these are imminent. AI infrastructure expansion is accelerating, not decelerating. Consumer demand recovery would require PC refresh cycles (not happening until 2025-2026 at earliest) and smartphone storage growth (which remains flat). Capacity expansion is multi-year projects. Inventory levels currently reflect constrained supply.

Asymmetric Risk

The pricing risk is asymmetric. Upside is limited. Prices are unlikely to fall 30-40% because supply growth is constrained. But downside risk—prices rising another 20-30%—is material if AI demand accelerates beyond expectations or if DRAM-like dynamics take hold.

This asymmetry counsels buying storage sooner rather than later. Waiting for prices to fall risks overpaying for storage that doesn't improve at lower prices.

As manufacturers move to higher-layer NAND architectures, production time increases due to added complexity. Estimated data shows a 12% increase for 232-layer and 20% for 321-layer architectures.

Implications for Different Market Segments

Enterprise and Data Center Markets

Enterprise customers should anticipate sustained premium pricing for enterprise-class SSDs. QLC adoption might offer some per-gigabyte savings, but not at scale that materially shifts total cost of ownership. Lock in capacity commitments early if possible. Negotiate multi-year contracts to avoid renegotiating at even higher prices.

Data center buildouts for AI infrastructure face a permanent cost adjustment. The $X per terabyte model that worked in 2023 no longer applies. Budget accordingly.

Consumer and Small Business Markets

Consumer SSD pricing will remain elevated relative to 2023 levels. Don't expect to find 1TB SSDs at

For small businesses provisioning storage, the calculus has shifted. In-house NAS and storage server costs have increased. Cloud storage alternatives are worth re-evaluating because the economics have changed.

Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs)

OEMs building systems with integrated storage face margin pressure. Absorbing full cost increases isn't viable. Passing them to customers is risky. Smart manufacturers are segmenting products—premium models with advanced storage, budget models with adequate but not excessive storage—to navigate pricing pressure.

What You Should Do About It

Immediate Actions

If you've been planning a storage upgrade, accelerate the timeline. Buy now rather than waiting. Current pricing likely represents the low end of the range for the next 12-18 months. Waiting for sales that might not materialize isn't worth the risk.

For enterprise customers, this means finalizing procurement plans and locking in supplier commitments. The cost of delaying storage deployment now is higher than the cost of overprovisioning slightly.

For consumers, this means being strategic about capacity. Buy the storage you actually need for the next three years, not just the next six months. You'll use it. You won't regret having the capacity.

Medium-Term Strategies

For small businesses and mid-market enterprises, evaluate cloud storage alternatives. As onsite storage costs increase, cloud storage pricing becomes more competitive. The economics might favor outsourcing storage to cloud providers rather than building internal infrastructure.

For individuals with large storage requirements (video creators, photographers, researchers), prioritize external storage over internal upgrades. Portable SSDs and NAS devices offer flexibility and are easier to upgrade later.

Consider longer-term storage strategies rather than optimizing for current pricing. If you're deploying infrastructure that will last five years, make purchasing decisions based on total cost of ownership over that period, not on today's spot pricing.

Technical Approaches

Where feasible, adopt storage efficiency technologies. Deduplication, compression, and tiered storage reduce the total capacity you need. A dollar saved on avoiding unnecessary storage is more valuable than waiting for that dollar to cost less.

For AI and machine learning workloads, carefully evaluate storage requirements. Training jobs have intensive I/O requirements. Inference jobs typically have lower requirements. Tier your storage accordingly rather than provisioning premium storage for all workloads.

Competitive Positioning and Market Consolidation

Manufacturer Positioning

NAND manufacturers are acutely aware that pricing power is temporary. Competitors are all executing similar strategies: investing in advanced technologies, limiting bit growth, and optimizing margins. This doesn't create competitive advantage. It creates industry alignment around higher prices.

Individual manufacturers might offer better terms or faster delivery for enterprise customers. They might provide technical support or custom firmware for OEM partners. But fundamental pricing relief isn't coming from competition. It's coming from supply and demand dynamics, and those dynamics favor manufacturers right now.

Market Consolidation Risks

Smaller NAND manufacturers might struggle with pricing pressure if they lack the scale of Samsung, SK Hynix, or Kioxia. Smaller players might exit the market or consolidate. This reduces supply diversity and potentially reinforces pricing power for remaining suppliers.

This consolidation risk hasn't manifested dramatically yet, but it's a tail risk worth monitoring. A market dominated by three suppliers has fewer competitive pressures than a market with six or eight suppliers.

Estimated data shows that SSD prices are expected to remain elevated across all market segments, with enterprise and data center markets facing the highest costs.

Industry and Regulatory Context

Geopolitical Supply Chain Factors

NAND manufacturing is concentrated in Taiwan (TSMC, Kioxia), South Korea (Samsung, SK Hynix), and Japan (Kioxia, smaller players). Supply chain resilience and geopolitical risk are relevant to long-term pricing.

Recent tensions around Taiwan and semiconductor manufacturing have prompted policy discussions about onshoring. Some governments are subsidizing domestic NAND production. These efforts take years to materialize and represent only a small fraction of total capacity. They're not an immediate relief valve for pricing pressure, but they're worth monitoring long-term.

Environmental and Sustainability Considerations

NAND manufacturing is energy-intensive and water-intensive. Environmental regulations and sustainability demands are gradually increasing manufacturing costs. This contributes to structural pricing pressure independent of market dynamics.

Manufacturers investing in more efficient processes are partially motivated by sustainability. This is positive long-term but doesn't reduce near-term pricing pressure.

Comparing This Cycle to Historical Precedents

The 2017-2019 NAND Spike

The last major NAND price spike occurred in 2017-2019. Oversupply had crashed prices through 2016. When demand recovered, manufacturers ramped production aggressively. Prices spiked temporarily but fell again as new capacity came online.

The current cycle is fundamentally different. The demand driver (AI infrastructure) is structural, not cyclical. The supply constraint (equipment bottlenecks, manufacturing complexity) is physical, not financial. Pricing is less likely to retrace dramatically.

The 2021-2022 Shortage

Supply chain disruptions in 2021-2022 caused temporary NAND shortages and price spikes. Prices normalized once supply chains stabilized. That cycle lasted 12-18 months.

The current cycle could persist 24-36 months or longer because it's not driven by temporary disruption. It's driven by structural shifts in demand and supply strategy.

Real-World Examples and Case Studies

Enterprise Data Center Buildout Example

A mid-market cloud provider provisioning infrastructure for AI services faces approximately 40% higher storage costs than they budgeted two years ago. They can't defer the buildout—competition demands timely deployment. They absorb the cost increase, then pass some of it to customers through premium pricing for AI-intensive services.

Result: enterprise customers of cloud services see 15-25% price increases for AI infrastructure services. Those increases didn't come from compute costs. They came from storage.

OEM Strategic Response

A major laptop manufacturer building budget and mid-range systems faces SSD cost increases that would compress margins by 8-12%. They respond by:

- Reducing storage capacity in budget models (256GB instead of 512GB)

- Increasing prices on mid-range models by 5-7%

- Shifting aggressive promotions to budget models to maintain volume

Result: consumers buying budget laptops get less storage. Consumers buying mid-range models pay more. Storage costs are partially absorbed, partially passed through, partially avoided through reduced capacity.

Smartphone Manufacturer Impact

Flagship smartphone base storage capacity shifts from 128GB to 256GB—not because of user demand, but because lower capacities become uncompetitive at higher price points. Margins compress. The manufacturer introduces a lower-priced model with reduced storage to capture budget-conscious buyers.

Result: smartphone market fragments into smaller segments with differentiated storage, and overall NAND consumption per smartphone actually declines despite higher costs.

The Investment Perspective

For Technology Investors

NAND manufacturers' stock valuations should reflect sustained margin expansion through 2026. Capital returns to shareholders might exceed new capacity investment. This is historically unusual—manufacturers are typically reinvesting profits into growth. This cycle resembles oligopoly pricing power more than growth investment.

Equipment suppliers benefit from sustained capex spending even without proportional capacity growth. The complexity of advanced NAND requires more equipment per bit of capacity produced.

For Infrastructure Investors

Data center assets with built-in storage capacity should appreciate as replacement costs rise. Early infrastructure deployments made when storage was cheaper become more valuable relative to new deployments facing higher costs.

Cloud storage companies might face margin pressure if they're locked into contracts that don't reflect rising storage costs. New contracts should incorporate cost escalation clauses.

Putting It All Together: The Structural Shift Explained

NAND flash pricing is undergoing a structural transformation driven by converging forces:

Demand Side: AI infrastructure is consuming enormous volumes of premium NAND components simultaneously. This demand is structural—AI deployments don't defer or reduce storage requirements based on cost. Enterprise customers must buy capacity.

Supply Side: Manufacturers are deliberately limiting bit growth while investing in higher-margin technologies. Equipment constraints prevent rapid scaling. Manufacturing complexity increases faster than capacity expansion. Physical constraints (cleanrooms, skilled labor) create genuine bottlenecks.

Market Structure: Inventory no longer controls pricing. Contract negotiations and direct sales to enterprise customers set pricing. Consumer demand is weak and doesn't provide offsetting price pressure. Supply fragmentation between enterprise and consumer segments removes historical equilibrating mechanisms.

Competitive Dynamics: All manufacturers are executing similar strategies. Competition isn't driving prices down. It's reinforcing industry alignment around constrained bit growth and premium pricing.

The result is sustained, structural pricing elevation with limited downside risk. Prices could rise further if AI demand accelerates. Prices are unlikely to fall meaningfully because supply constraints are durable. The sweet spot for buying storage is now, before further increases occur.

This isn't a temporary crisis. It's a new reality. Plan accordingly.

FAQ

What is NAND flash and why does it matter?

NAND flash is the persistent storage technology powering all solid-state drives, USB drives, and smartphone storage. Unlike RAM, NAND retains data when powered off. It matters because SSD costs have increased structurally due to AI infrastructure demand and manufacturing constraints, directly impacting PC, server, and smartphone economics.

Why is AI driving up SSD prices?

AI data centers need enormous volumes of high-capacity storage for training datasets, model weights, and inference operations. A single large language model training facility might consume petabytes of storage. Unlike traditional enterprise upgrades spread over time, AI buildouts are happening simultaneously across multiple companies, creating concentrated demand that exceeds available supply.

How does DRAM pricing predict NAND pricing?

DRAM pricing spiked in 2024-2025 because manufacturers deliberately limited capacity expansion while investing in premium technologies like HBM. NAND pricing is following the same pattern: manufacturers are prioritizing higher-layer NAND and QLC adoption over raw capacity expansion. This strategy prioritizes margins over volume and creates sustained pricing elevation rather than temporary spikes.

Will SSD prices come down if I wait?

Unlikely in the near term. Historical cycles showed prices normalizing after 6-12 months. Current structural constraints suggest sustained elevation through 2026 or longer. Equipment bottlenecks, manufacturing complexity, and strong enterprise demand create genuine supply limits independent of pricing signals. Waiting risks overpaying; buying now likely offers better value.

What's the difference between TLC and QLC NAND, and which should I buy?

TLC stores three bits per cell; QLC stores four bits. QLC is cheaper per gigabyte but slower and degrades faster. For consumer general-purpose use, QLC is fine. For high-speed video editing, content creation, or database workloads, TLC offers better performance and longevity. Match technology to your workload rather than assuming cheaper is worse.

What should enterprise customers do about storage costs?

Lock in capacity commitments and pricing with suppliers now. Renegotiate multi-year contracts to avoid price renegotiations at even higher levels. Evaluate cloud storage alternatives as relative costs have shifted. Consider whether in-house storage infrastructure makes economic sense versus outsourcing to cloud providers with better economies of scale.

How much higher will SSD prices go?

Prices could rise another 20-30% if AI demand accelerates or if DRAM-like dynamics take hold across the NAND market. Downside risk is limited because supply constraints are durable. The asymmetry suggests buying sooner rather than later, as waiting risks paying more without prices normalizing downward.

Is storage still a good investment despite higher costs?

Yes, but with caveats. Storage is essential for modern computing and business operations. Higher costs are unavoidable. The optimization is buying what you need sooner at current prices rather than waiting for lower prices that may not materialize. Focus on storage efficiency (deduplication, compression, tiering) to reduce required capacity.

What about secondhand or refurbished SSDs?

Secondhand SSDs are worth considering if you're cost-conscious, but verify remaining lifespan through SMART data (S. M. A. R. T. reporting shows wear and health status). A used 500GB SSD at 60% of new price isn't a bargain if it has only 10% of its life remaining. New SSDs with warranty protection are safer despite higher costs.

How will this affect laptop and gaming PC prices?

OEMs will absorb some cost increases through margin compression, but expect 3-7% price increases on systems with larger storage. Budget systems might see reduced storage capacity (256GB instead of 512GB) to maintain price points. Premium systems will maintain capacity but increase prices. Gaming PC prices will rise more than mainstream laptops because gamers demand larger storage.

Should I upgrade my storage right now?

If you've planned an upgrade, yes—accelerate the timeline. Current pricing likely represents the low end of the range. If your current storage is adequate for 12-18 months, you can wait. But if you're at capacity limits or approaching them, buying now prevents paying 15-25% more in 6 months. This is one of the rare times when the optimal financial decision aligns with practical need.

Conclusion: A New Era of Storage Economics

The NAND flash market is entering a new phase. For three decades, storage pricing followed predictable cycles: supply imbalances caused temporary spikes, excess capacity caused price crashes, and markets normalized. That playbook is obsolete.

Artificial intelligence has fundamentally altered storage demand patterns. Data centers building AI infrastructure need massive, reliable, high-capacity storage immediately. They can't defer purchases. They can't accept alternative solutions. They need premium NAND components, and they need them in quantities that exceed available supply.

Simultaneously, manufacturers have shifted strategy. Rather than racing to expand capacity when demand rises, they're optimizing margins by investing in advanced technologies with higher price tags. Physical constraints on equipment, facilities, and skilled labor prevent rapid scaling even when incentives exist. Supply growth is deliberately limited.

The result is a market where inventory levels no longer drive pricing. Where demand divergence (strong enterprise, weak consumer) removes historical equilibrating mechanisms. Where structural constraints mean shortage conditions persist for years rather than quarters.

For end users, this means a simple truth: buy storage sooner rather than later. Current pricing likely represents the best value available for the next 18-24 months. Waiting for prices to normalize is a losing bet. The structural changes driving elevated pricing are durable.

For enterprises and infrastructure builders, this means incorporating higher storage costs into long-term planning. The economics of data center deployments have shifted. Storage budgets need 25-40% increases relative to 2023 baselines. This is the new normal.

For technology investors, this means recognizing that memory manufacturers have moved from growth strategies to margin optimization. Capital returns might exceed growth investment. Competitive dynamics might tighten if smaller suppliers exit the market. The industry is consolidating around sustainable, profitable pricing rather than growth-at-any-cost dynamics.

The NAND market has shifted from a commodity market with predictable cycles to a constrained market with structural pricing power. Recognizing and adapting to that shift is essential for anyone depending on storage capacity. The days of waiting for prices to fall are over. Plan accordingly, buy strategically, and accept that storage is entering a more expensive era.

Key Takeaways

- NAND pricing is structurally elevated due to AI infrastructure demand and manufacturer strategy, not temporary imbalances

- Inventory levels no longer control pricing; supply strategy and manufacturing capacity constraints dominate

- Equipment bottlenecks and fab capacity limits prevent rapid scaling even with unlimited capital

- Consumer demand is weakening while enterprise demand remains strong, removing historical price equilibration

- Similar to DRAM pricing dynamics, NAND elevation is likely to persist 18-24+ months

- Enterprise customers should lock in capacity commitments early; retail buyers should purchase storage sooner rather than later

- Manufacturers prioritizing higher-layer NAND and QLC adoption limits bit growth despite increased capex

Related Articles

- Micron's AI Memory Pivot: What It Means for Consumers and PC Builders [2025]

- Ultrafast Laser Nanoscale Chip Cooling: Revolutionary Heat Management [2025]

- DRAM Prices Surge 60% as AI Demand Reshapes Memory Market [2026]

- DDR5 RAM Prices Stabilize at $900: What It Means [2025]

- Why Premium SSDs Cost More Than Gold: Storage Price Crisis [2025]

- TSMC's AI Chip Demand 'Endless': What Record Earnings Mean for Tech [2025]

![AI Storage Demand Is Breaking NAND Flash Markets [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/ai-storage-demand-is-breaking-nand-flash-markets-2025/image-1-1768743364449.jpg)