Introduction: When Politics Meets Science

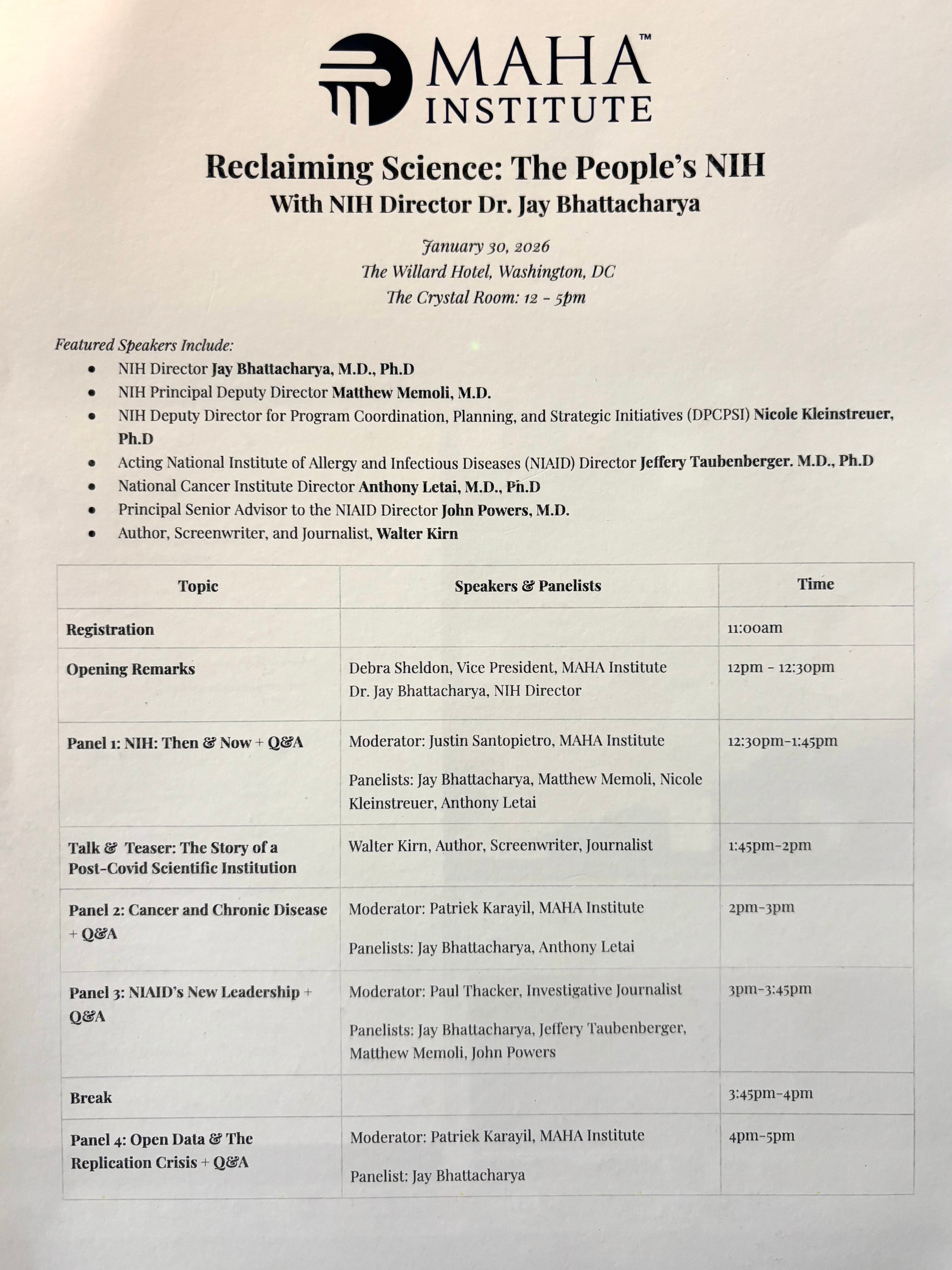

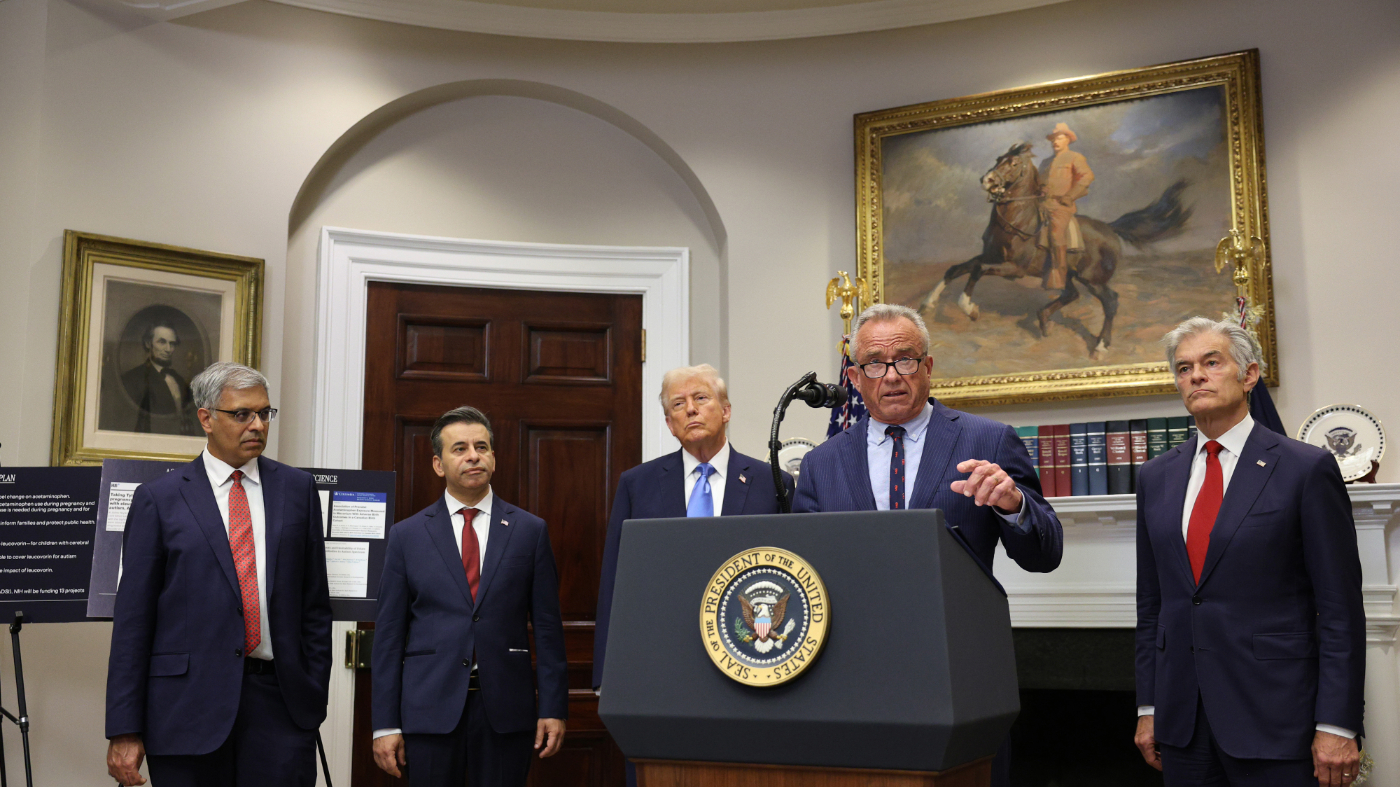

Imagine walking into a room where the nation's top scientific organization sits down with advocates of controversial health ideas, and nobody walks out angry. That actually happened in late January 2025 in Washington, DC. The National Institutes of Health—the world's best-funded scientific organization with an annual budget north of $47 billion—sent its leadership to an event hosted by the MAHA Institute, short for Make America Healthy Again.

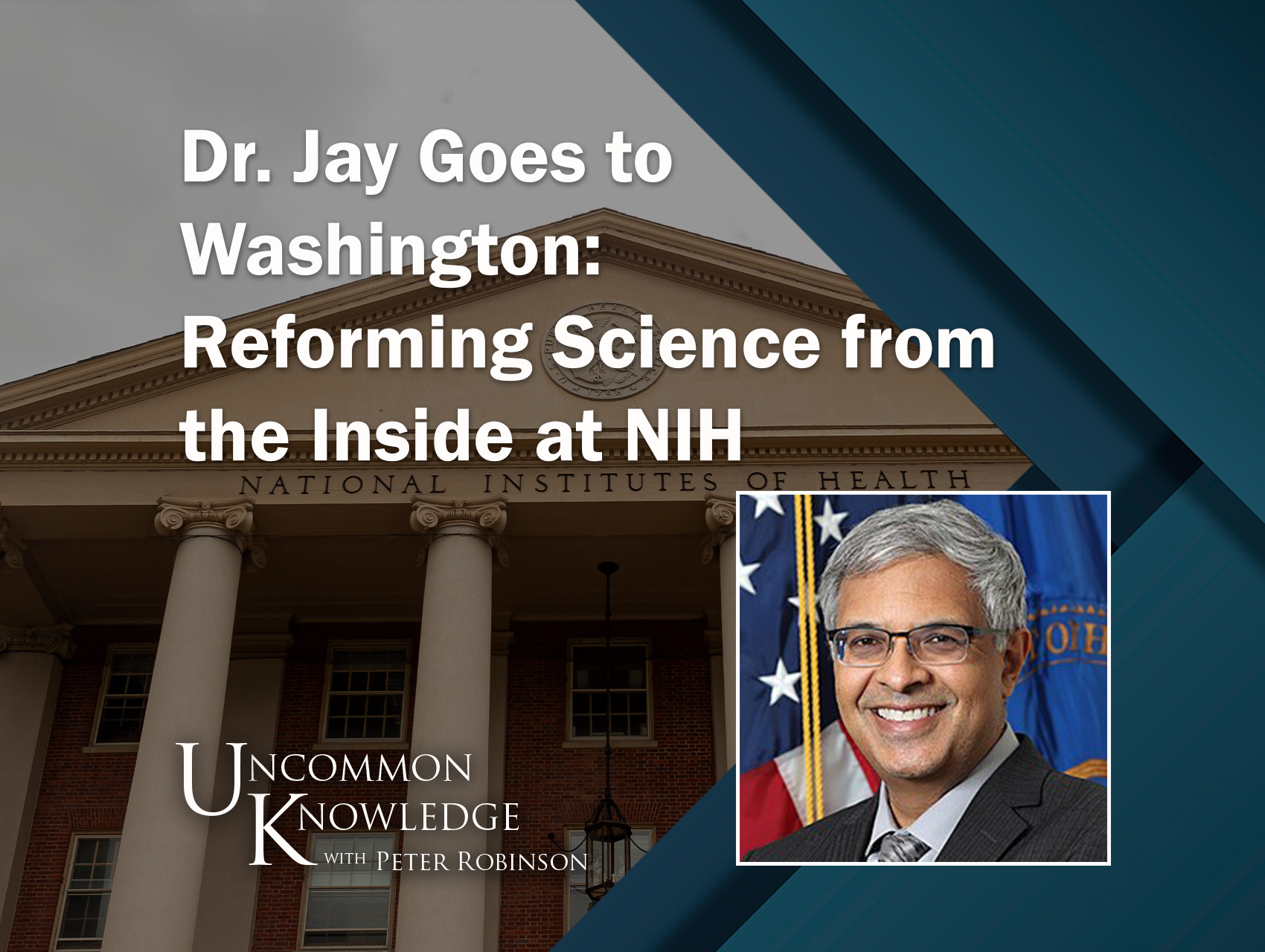

On the surface, it sounds absurd. The MAHA movement has become synonymous with vaccine skepticism, alternative medicine promotion, and revisionist claims about the pandemic. Yet Jay Bhattacharya, the newly appointed NIH director, received a partial standing ovation from this audience. Senior NIH staff sat beside him, including the directors of the National Cancer Institute and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

What happened at that event wasn't just political theater. It was a window into something much bigger: a fundamental reshaping of how America's scientific establishment plans to operate. Bhattacharya came with a vision he's calling a "second scientific revolution." The pitch sounds noble in theory. The execution? That's where things get complicated.

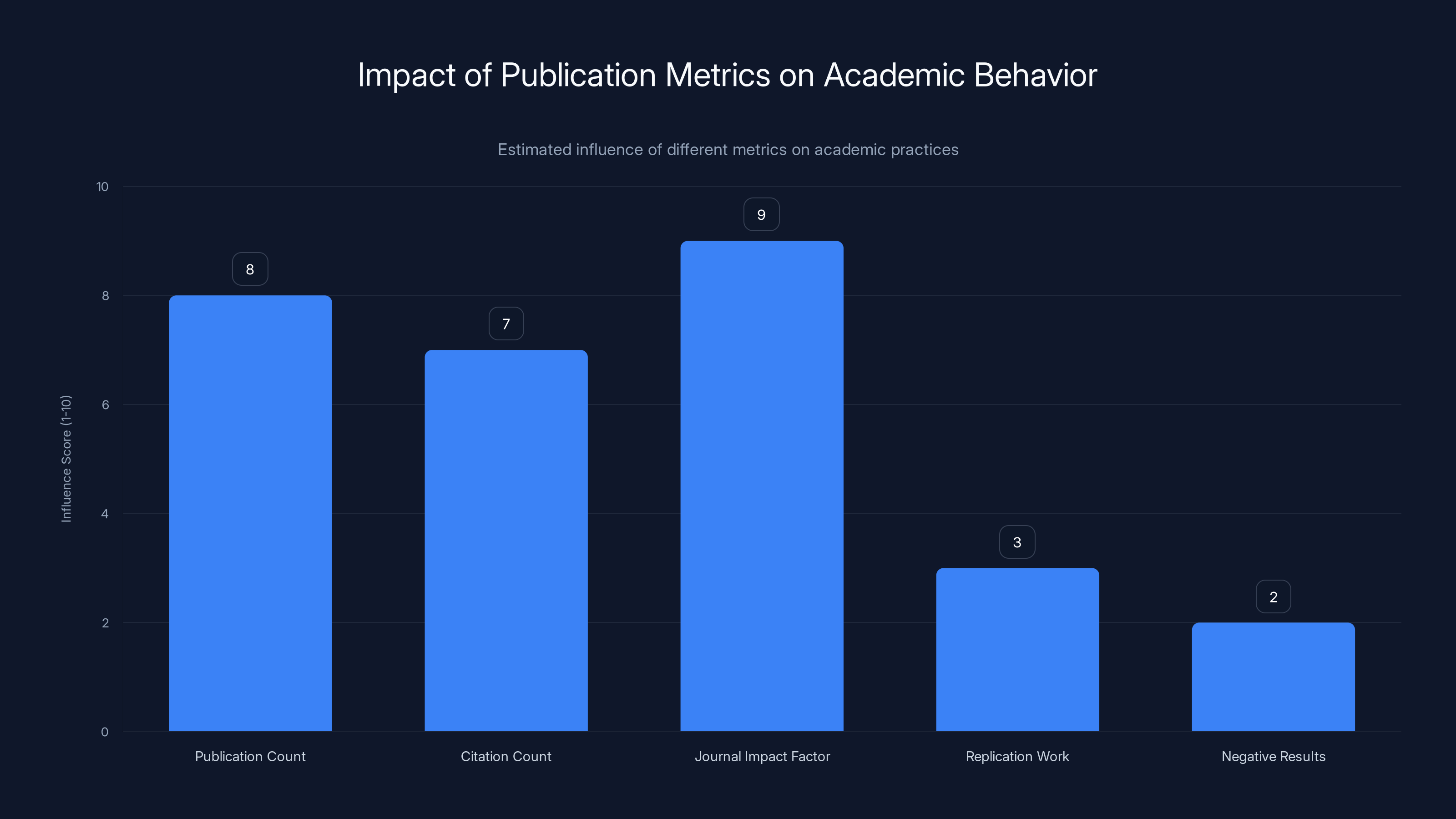

The stated goal is to refocus science on replication and reproducibility rather than publication counts. To democratize truth-making. To rebuild public trust in institutions that many Americans now view with deep skepticism. These aren't inherently bad ideas. In fact, the scientific community has been wrestling with reproducibility problems for over a decade, as highlighted by a recent study.

But here's the problem: Bhattacharya's revolution is inseparable from his personal grievances about the pandemic response. His willingness to court MAHA—an organization that actively promotes ideas contradicting mountains of scientific evidence—reveals the inconsistencies at the heart of his agenda. You can't claim to want better science while simultaneously platforming people who reject the scientific method itself.

This article breaks down what's actually happening at the NIH, what a "second scientific revolution" would look like in practice, and why the gap between Bhattacharya's rhetoric and reality matters for science funding, public health, and your tax dollars.

TL; DR

- The NIH director frames his agenda as scientific reform: Focus on replication over publication metrics, rebuilding public trust, and questioning pandemic-era decisions.

- The politics complicate the messaging: His courting of MAHA Institute audiences and willingness to entertain vaccine skepticism undermine claims about improving rigorous science.

- Real reproducibility problems exist: But solutions require more funding and institutional change, not political realignment.

- The stakes are enormous: The NIH distributes roughly $47 billion annually to researchers across the country, making the director's vision consequential.

- Consistency matters: Scientific reform doesn't work when it's selectively applied based on political allegiance.

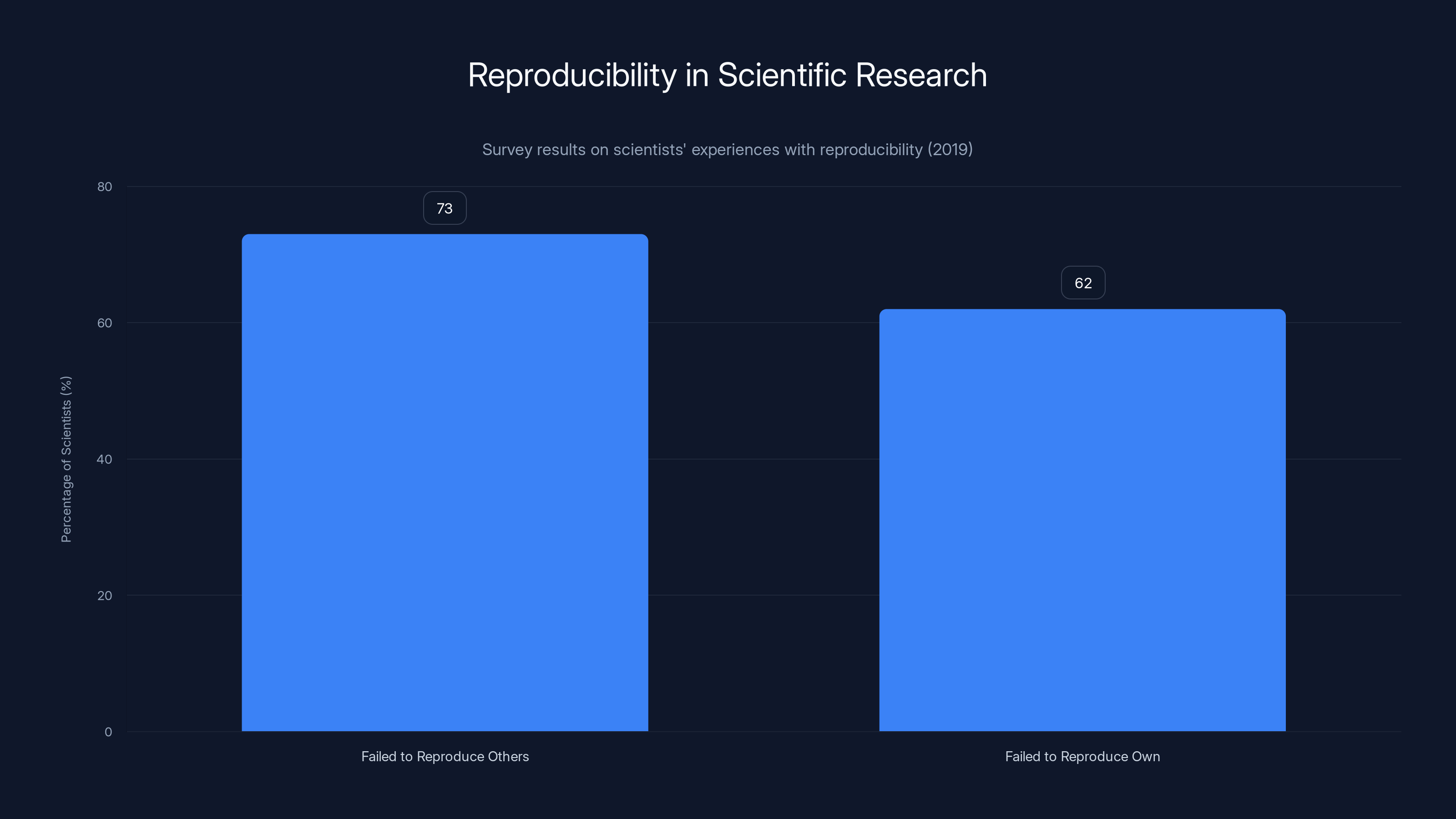

A 2019 survey revealed that 73% of scientists failed to reproduce others' results, while 62% struggled with their own, highlighting the reproducibility crisis in science.

The Strange Alliance: NIH Leadership at a MAHA Event

Let's start with what actually happened that day, because the details reveal everything about the contradictions at play.

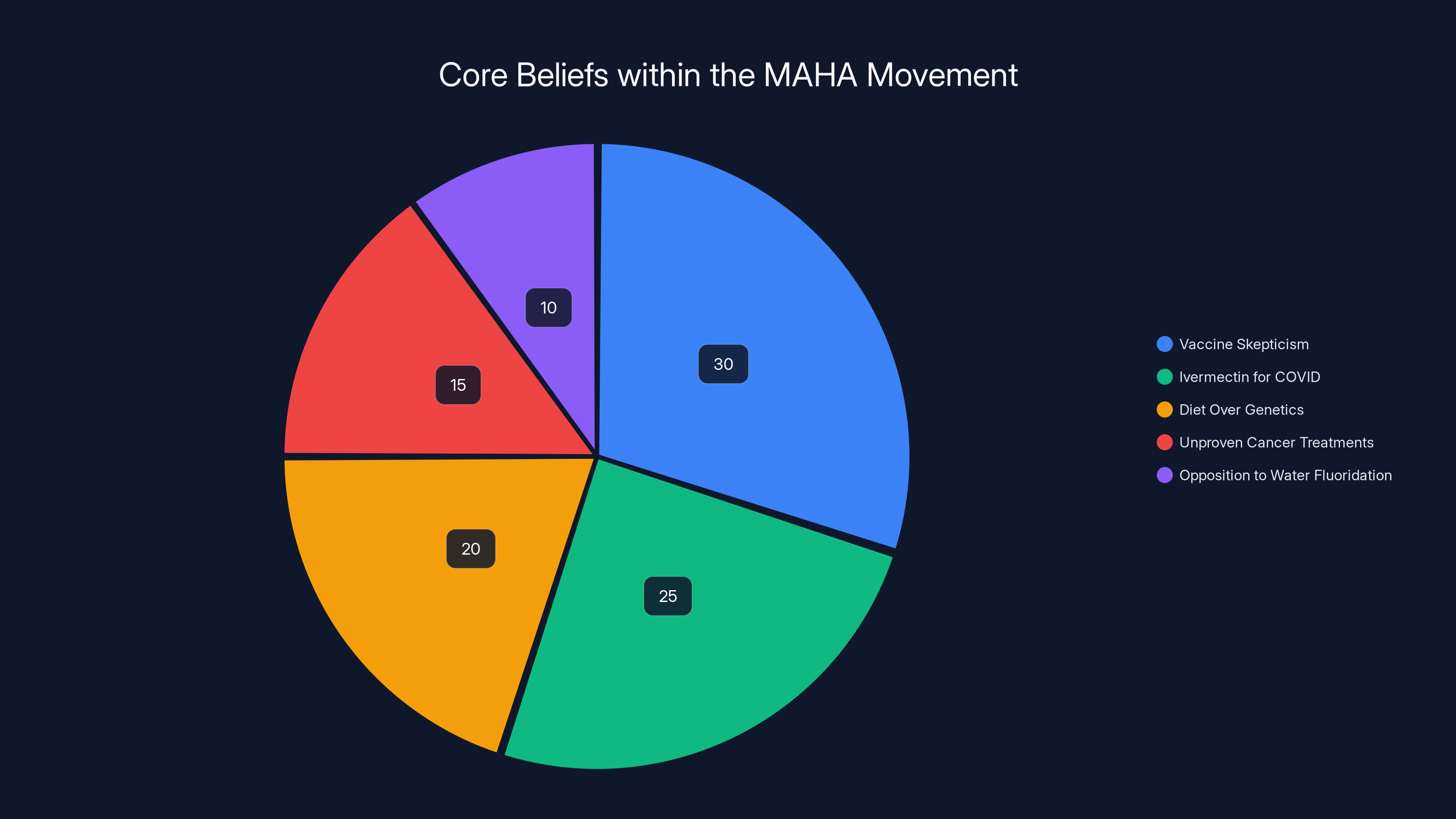

The MAHA Institute, for those unfamiliar, isn't some fringe internet community. It's the institutional arm of a political movement that gained significant influence during the 2024 election cycle. Its advisory board includes prominent figures who've questioned vaccine safety, promoted alternative medicine, and claimed that chronic disease epidemics are primarily driven by processed food rather than genetics, environment, and behavior.

Now, there's a kernel of truth buried in there. American chronic disease rates are genuinely alarming. Diet absolutely matters. The healthcare system has real failures. These are legitimate topics for discussion.

But here's where it gets weird. At the January event, MAHA moderators explicitly asked NIH leadership whether COVID vaccines could cause cancer. The question wasn't framed skeptically—it was posed as something worth investigating. An audience member asked why alternative treatments for serious diseases aren't being researched more. A speaker who announced his family had never received a COVID vaccine received applause from the room.

One MAHA Institute vice president introduced the event by describing the NIH as "discredited" and calling for its "reclamation" from people like Anthony Fauci. She framed this reclamation as something ordinary Americans wanted, positioning science itself as something that had been "weaponized."

And Bhattacharya didn't push back on any of this. He leaned in.

Reporters from Nature and Science were denied entry to the event. Think about that for a second. An event featuring the head of the National Institutes of Health, the world's largest public funder of biomedical research, was deliberately kept away from mainstream science journalists. If the goal was genuine scientific dialogue, why exclude the people who cover science for a living?

The event included 15 minutes devoted to funding a satirical film that portrayed Anthony Fauci as an egomaniacal lightweight, vaccines as placebos, and Bhattacharya as the hero who could restore sanity to science. This wasn't a serious scientific discussion. It was political theater with a scientific veneer.

Yet Bhattacharya and his team spent the afternoon defending this approach, arguing not just that the NIH needed to change, but that nothing less than a fundamental revolution in how science itself works was necessary.

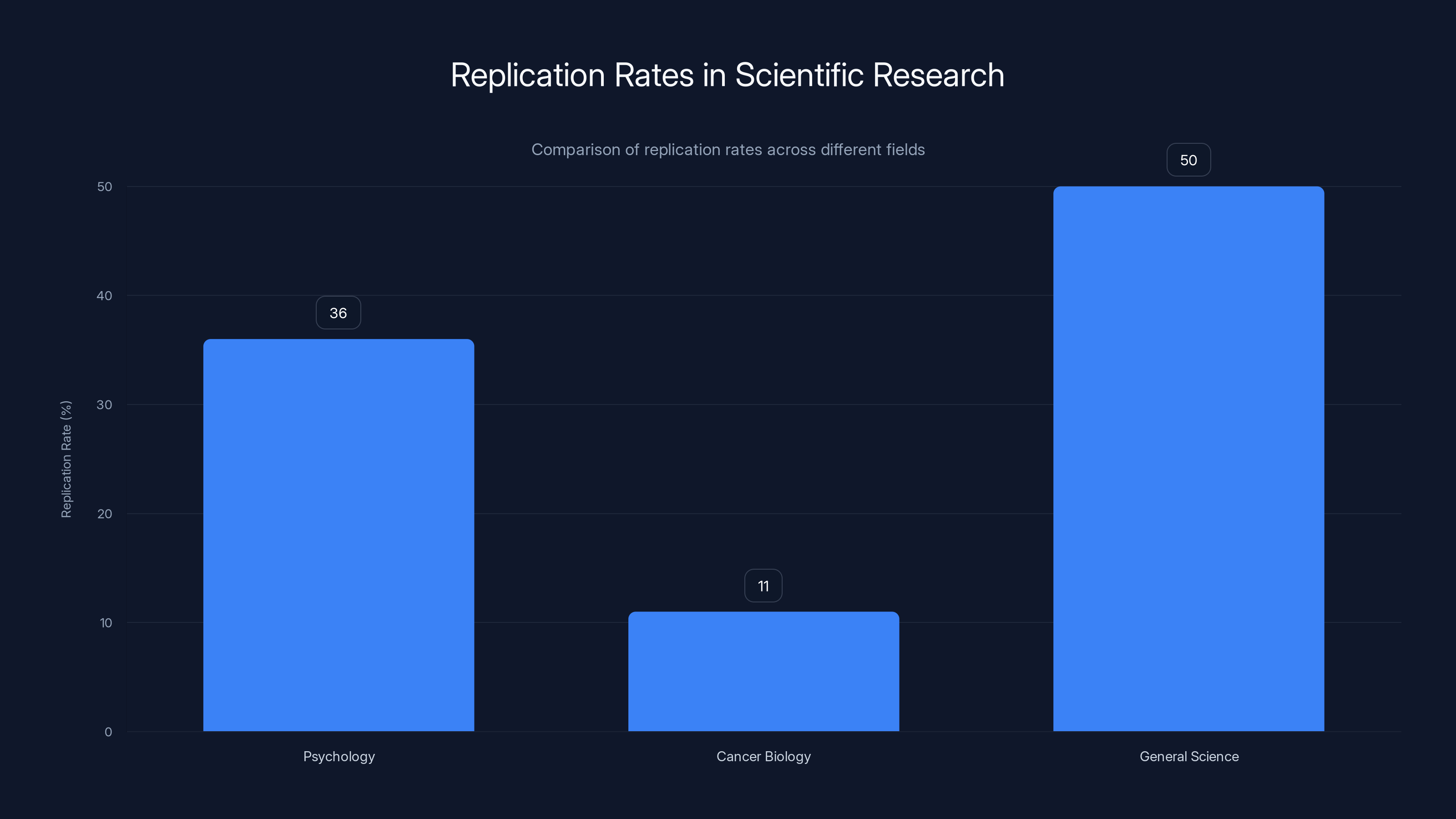

Replication success rates are critically low in psychology (36%) and oncology (11%), highlighting the reproducibility crisis in science. Estimated data based on studies from 2015 and 2012.

The Second Scientific Revolution: Grand Vision, Fuzzy Details

Bhattacharya's framing is worth examining closely because it's genuinely clever rhetorically, even if it doesn't hold up under scrutiny.

He compares his proposed "second scientific revolution" to the original scientific revolution of the 16th and 17th centuries. In that era, he argues, the Catholic Church held monopolistic power to decide what was true. The scientific revolution "democratized science fundamentally," transferring truth-making from church authorities to people with telescopes and empirical methods.

His argument: We need a similar revolution now, because COVID showed us that scientific authority became monopolistic in a different way. Experts decided not just what was scientifically true, but also how we should treat our neighbors, how society should function, and how we should live.

The core of his proposed solution is the "replication revolution." Instead of measuring scientific success by publication count—how many papers does a researcher publish?—measure it by replication success. Can other scientists independently verify the findings? Do multiple groups studying the same question arrive at similar conclusions?

Here's the thing: There's actually something legitimate here. The scientific community has spent years discussing exactly this problem. Researchers have become increasingly incentivized to publish novel findings rather than replicate existing work. Journals prefer surprising results. Universities and funding agencies reward publication volume over verification. This creates a system where false positives accumulate and get cited thousands of times before anyone discovers they don't replicate.

So far, Bhattacharya is describing a real problem that many serious scientists have identified independently.

But then he starts talking about what this revolution should look like in practice, and the proposal gets vaguer. It's not just narrow replication of single papers, he says. It includes "reproduction," which he defines as something vaguely connected to disagreement between scientists leading to new ideas.

Translated into English: When two scientists disagree about results, let's call that part of the replication revolution, because maybe they'll generate new ideas from the disagreement.

That's not quite the same thing as rigorously reproducing someone else's work, is it?

This is where the fuzzy thinking becomes evident. A real reproducibility revolution would involve major structural changes: funding mechanisms that reward replication studies, journal editorial policies that prioritize verification, hiring and promotion decisions that value rigorous science over flashy novelty, and honest reckoning with which fields and findings have reproducibility problems.

Bhattacharya's version sounds good but remains frustratingly vague about implementation.

The Reproducibility Crisis: A Real Problem That Needs Real Solutions

Before we go further, let's establish that the reproducibility problem in science is absolutely genuine and consequential.

Consider what researchers actually spend their time on. Getting funding means impressing grant agencies. Getting hired and promoted means impressive publication records. Getting published in top journals means your work needs to be novel and significant. The entire incentive structure points toward publishing surprising findings, not confirming boring ones.

Who wants to spend two years carefully repeating someone else's experiment? It doesn't make your career. It doesn't attract funding. It doesn't get published in prestigious journals. But if those experiments were wrong, and thousands of subsequent researchers build on that false foundation, the cost to the field is enormous.

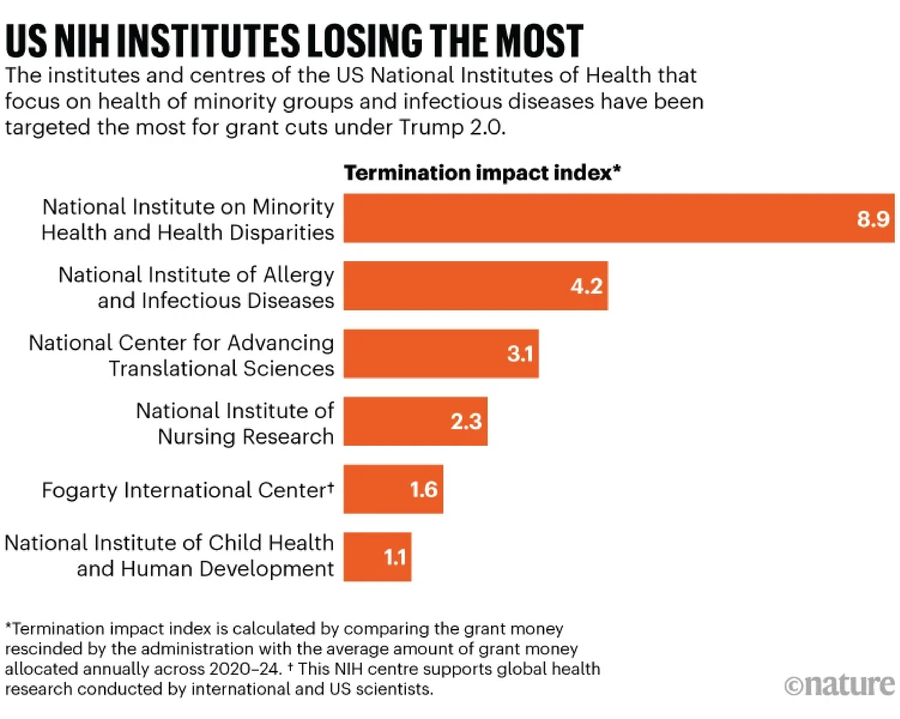

In fields like psychology, the replication crisis has been particularly acute. A 2015 project that attempted to replicate 100 published psychology studies found that only 36% of them replicated when tested with similar methods. In other words, nearly two-thirds of these published, peer-reviewed studies didn't actually show what they claimed to show.

This isn't because psychologists are dishonest. It's because the system incentivizes novelty over verification. Researchers run many statistical tests looking for significant results. They design studies in ways they think will work. They publish successes and forget about failures (publication bias). They p-hack—run multiple analyses until something looks significant.

Other fields face similar issues. In oncology, a 2012 Amgen study found that researchers in their company could only replicate about 11% of published cancer biology studies. In drug development, high failure rates in clinical trials often trace back to preclinical studies that couldn't be reproduced.

These are trillion-dollar problems. Bad science wastes research funding, sends patients down ineffective treatment paths, and delays real cures.

So what would actually fix this? Several things, none of which are truly revolutionary:

Funding for replication studies: Make it possible for scientists to get grants specifically for reproducing important work. Right now, replication is treated as part of normal science, not as funded research. That's backwards.

Journal policy changes: Journals could reserve space for replication studies. They could publish null results. They could change review processes to reward careful work over flashy novelty.

Institutional incentives: Universities and funding agencies could count replication contributions more heavily in hiring and promotion decisions. They could be explicit that rigorous work matters more than publication volume.

Pre-registration: For some research, registering hypotheses and analysis plans before conducting the study can reduce p-hacking and other questionable practices.

Statistical transparency: Making raw data publicly available, publishing statistical code, and being clear about how many tests were run would help identify problematic analyses.

None of this requires a revolution. It requires sustained effort to change incentive structures. It requires funding. It requires willingness from prestigious journals and institutions to prioritize quality over novelty.

Bhattacharya talks about this general direction. But he doesn't explain how he'll actually implement it at the NIH, which controls research funding but not university hiring practices, journal policies, or the broader culture of science.

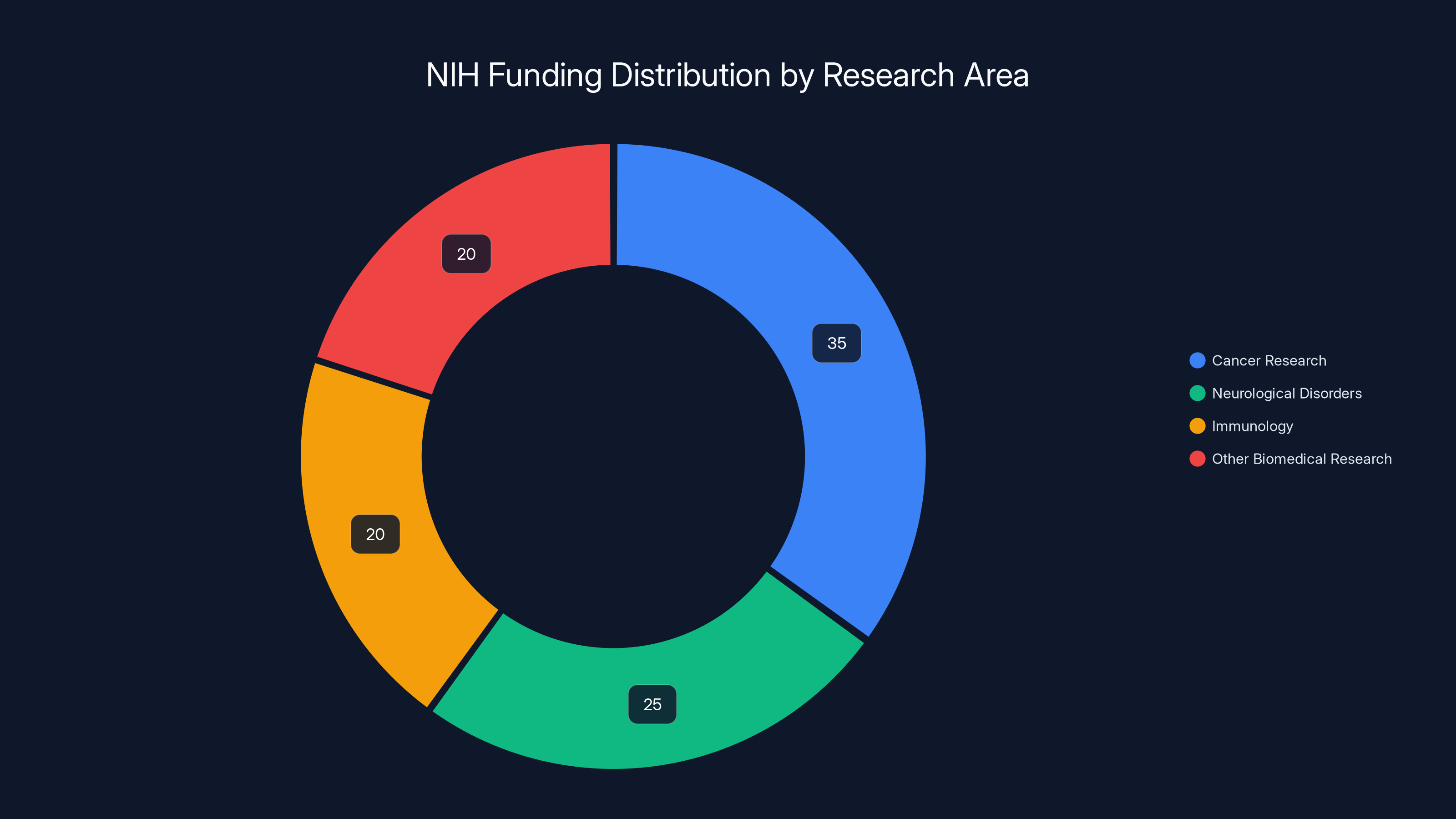

Estimated data: NIH funding is primarily allocated to cancer research, followed by neurological disorders and immunology, reflecting its priorities in advancing biomedical research.

COVID, Trust, and Selective Anger

Now we get to the emotional core of Bhattacharya's position, and why his credibility suffers from it.

Bhattacharya frames the pandemic response as the origin story for his revolution. According to his rhetoric, scientific authorities used COVID to make decisions that went beyond their legitimate domain. They decided not just what was scientifically true, but also how people should live, whom they should see, and what spiritual or existential meaning they should derive from public health.

In his framing, this represents a catastrophic failure of scientific humility. Science should answer narrow questions: Does this medicine work? Is this virus circulating? Can this intervention reduce transmission? But it overreached. It tried to answer bigger questions about how society should function.

Here's the problem with this argument: Much of what happened during the pandemic wasn't driven by science overreach. It was driven by policy decisions made by politicians, based on some scientific input but also shaped by politics, economics, and competing values.

Did scientific advisors sometimes overstate certainty? Absolutely. Did policies sometimes persist longer than evidence supported? Yes. Did public health experts sometimes communicate poorly about uncertainty? Definitely.

But the claim that scientific authorities decided our spiritual relationships or how we should treat our neighbors misunderstands how policy works. Those decisions came from mayors, governors, presidents, and federal agencies that balanced scientific input against other considerations.

Moreover—and this is crucial—Bhattacharya's anger about pandemic decisions is selective in ways that undermine his universalizing claims about scientific revolution.

He's angry about lockdowns, school closures, vaccine mandates, and mask guidance. He's angrier about these than about the 1.1 million Americans who died from COVID, most of them preventable with available vaccines.

He's skeptical of vaccine safety claims while being uncritical of alternative medicine claims that lack robust evidence.

He's critical of scientific authorities who overstepped while being comfortable in rooms where alternative practitioners make sweeping health claims backed by cherry-picked data.

This isn't revolutionary science thinking. This is politics dressed up in scientific language.

A genuine revolution in scientific practice would include uncomfortable truths from every direction: that vaccines work despite potential side effects being real but rare, that lockdowns had real costs alongside real benefits, that scientific uncertainty is genuine even when policies must be made, that some public health measures persisted past their utility, and that denialism about fundamental questions (does the virus cause illness? do vaccines prevent infection?) represents rejection of evidence-based thinking.

Bhattacharya's proposed revolution doesn't grapple with any of this complexity. It uses real problems with pandemic communication to justify a selective skepticism of science that conveniently excludes ideas he apparently agrees with.

MAHA, Anti-Science, and the Trust Problem

Let's be direct about what the MAHA movement actually represents, because this matters for understanding Bhattacharya's strategy.

MAHA emerged from anti-vaccine activism, particularly the claim that vaccines cause autism (they don't—this has been studied extensively and repeatedly disproven). It expanded to include broader skepticism of vaccines, pharmaceutical medicine more generally, and scientific institutions.

There are legitimate critiques of pharmaceutical companies, medical institutions, and health authorities embedded within MAHA messaging. They're surrounded, though, by claims that contradict well-established evidence.

Vaccine skepticism. Ivermectin as a COVID treatment (it doesn't work for COVID). Claims that chronic disease is primarily driven by diet rather than genetics and environment. Promotion of unproven cancer treatments. Opposition to water fluoridation based on now-debunked concerns about mass medication.

These aren't minority positions within MAHA circles. They're central to the movement's identity.

So when Bhattacharya sits in a room where these ideas are treated as legitimate questions for scientific investigation, he's not advancing scientific rigor. He's signaling that certain politically comfortable forms of anti-scientific thinking deserve a seat at the table.

Trust in scientific institutions is genuinely damaged. This is a real problem that deserves serious attention. But rebuilding that trust doesn't happen by delegitimizing the institutions while giving platforms to ideas that contradict evidence. It happens through transparency, humility about uncertainty, willingness to acknowledge past mistakes, and consistent application of evidence-based standards regardless of whether findings are politically convenient.

Bhattacharya's approach does the opposite. It uses justified skepticism about pandemic overreach to justify unjustified skepticism about vaccine efficacy.

Estimated data shows significant variation in replication rates across fields, with psychology at 36% and cancer biology at only 11%. General science is estimated at 50% for broader context.

What the NIH Actually Funds and Why It Matters

To understand the stakes of Bhattacharya's "revolution," you need to understand what the NIH actually does.

The NIH isn't a research institute that employs thousands of scientists in government labs, though it does have intramural research programs. Primarily, it's a funding agency. It distributes roughly $47 billion annually to researchers at universities, medical centers, and private research organizations across the United States.

If you go to a major research hospital and see cutting-edge cancer research, neurological research, immunology work, or basically any biomedical research program, there's a decent chance it's at least partially funded by NIH grants.

The NIH operates through 27 different institutes and centers, each with its own budget and research priorities. The National Cancer Institute funds cancer research. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke funds neuroscience. And so on.

How does this funding actually work? Scientists write grant proposals. These go through a peer review process where other scientists in the same field evaluate them for scientific merit. Proposals that score well get funded. Proposals that don't, don't.

The system isn't perfect. Reviewers sometimes miss important work. Political considerations sometimes influence which institutes get budget increases. Established researchers have advantages over newcomers. But the peer review process generally works reasonably well at identifying scientifically sound proposals.

Now, Bhattacharya controls what his leadership does within this system. He can't directly change how universities hire scientists or how journals operate. But he can change NIH priorities, funding mechanisms, peer review criteria, and what kinds of research get emphasized versus deprioritized.

If he genuinely wanted to implement a "replication revolution," he could:

- Create a new funding mechanism specifically for replication studies, with dedicated budget

- Change NIH peer review criteria to explicitly reward replication and reproducibility

- Fund research investigating which fields have the worst reproducibility problems

- Partner with journals to publish NIH-funded replication studies

- Make data sharing and analytical transparency requirements for NIH grants

He could also do the opposite: use his authority to deprioritize research he disagrees with based on political rather than scientific grounds.

Given his public statements and the audiences he's courting, there's reason for concern about which direction he'll actually go.

The Tension Between Reform and Politics

This is the core contradiction that defines Bhattacharya's position.

On one hand, his diagnosis of problems with scientific incentives is basically correct. Scientists are incentivized to publish novel findings. This creates perverse incentives. Reproducibility suffers. Public trust declines when spectacular findings don't hold up.

On the other hand, his solution is vague, and his coalition is explicitly anti-science in ways that contradict his stated reform goals.

You cannot simultaneously argue that:

- Science needs to return to rigorous evidence-based standards and away from political influence

- Vaccine skeptics deserve platforms in scientific institutions

- Alternative medicine should be researched more

- Scientists overstepped during the pandemic by making moral claims beyond their expertise

Because the third and fourth points aren't about evidence-based reform. They're about which evidence you find politically comfortable.

Fluoridation of water supplies has been extensively studied. It works. It's safe. Every major scientific organization supports it. When MAHA advocates oppose it, they're not engaging in rigorous science. They're engaging in the same kind of politics-over-evidence thinking Bhattacharya claims to oppose.

Ivermectin as a COVID treatment has been tested rigorously. It doesn't work. The studies are robust. The evidence is clear. When people in rooms Bhattacharya frequents promote ivermectin, they're not advancing a minority scientific opinion. They're rejecting evidence.

Vaccine-autism link? Studied repeatedly, across millions of children. No link. Every major study confirms this. Promoting this idea isn't brave contrarianism. It's misrepresenting evidence.

A genuinely revolutionary approach would acknowledge that pandemic responses involved both legitimate public health measures and legitimate criticisms. It would preserve funding for vaccines that work. It would also acknowledge that lockdown costs were real and sometimes exceeded benefits. It would fund rigorous research on pandemic policies—what worked, what didn't, how to do better next time—without pre-deciding that political grievances about lockdowns should drive scientific priorities.

Instead, Bhattacharya seems to be offering something narrower: scientific reform packaged as revolutionary language, deployed to justify skepticism of research findings he personally dislikes, and softened by platforming people who reject evidence when it contradicts their priors.

That's not a revolution. That's a power struggle.

Estimated data suggests that publication count, citation count, and journal impact factor heavily influence academic behavior, often at the expense of replication work and publishing negative results.

Publication Metrics: Why They're Bad, But Not for the Reasons Bhattacharya Implies

Let's dig deeper into one specific claim Bhattacharya makes: that scientists shouldn't be evaluated primarily by publication counts.

He's right about this. It's one of the clearest areas where his diagnosis of a real problem is accurate.

The problem: Academic hiring, promotion, and funding decisions increasingly rely on metrics like publication count, citation count, and journal impact factor. This creates incentives to publish a lot, publish in prestigious journals, and get cited frequently.

The perverse outcomes: Scientists maximize for these metrics rather than for actual truth-seeking. They publish multiple papers from slightly different analyses of the same data (salami slicing). They chase trendy topics that will get cited. They avoid replication work. They avoid publishing negative results. They become incentivized to report surprising findings, even if the evidence is fragile.

So far, Bhattacharya is describing a genuine problem that serious scientists agree is serious.

But here's where his framing gets problematic. He presents this as a recent failure of scientific institutions. Actually, the problem has been growing for decades. It accelerated in the 1980s and 1990s as academia increasingly adopted business-school thinking about metrics and rankings.

Scientists have been complaining about this for years. In 2012, a group of scientists published the San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment (DORA), explicitly critiquing reliance on journal impact factor. The declaration has been signed by thousands of scientists and hundreds of organizations.

This isn't new thinking. This is decades-old, widely-acknowledged reform that hasn't been implemented because the incentive structures are powerful and changing them requires coordination across universities, journals, funders, and tenure committees.

What would actually help? Institutions valuing thoughtful, careful, rigorous work even if it's not flashy. Universities adopting hiring practices that consider depth over volume. Journals allocating space for replication studies. Funders explicitly including replication and rigor in evaluation criteria.

The NIH could do some of this. Not all of it. And Bhattacharya's vague calls for a "replication revolution" don't spell out which specific changes he'll implement using his actual authority.

Moreover, his framing as revolutionary obscures the fact that serious scientists have been pushing for exactly this for years. He's not discovering a new problem. He's weaponizing an existing problem to justify political changes to scientific priorities.

If his goal is genuinely to fix publication incentives, his approach should be technocratic and consistent: propose specific changes, implement them, measure outcomes, adjust. Instead, his approach is political: court constituencies that view the scientific establishment with suspicion, use vague revolutionary language, and avoid making specific commitments that might be measured against actual outcomes.

The Trust Crisis: Real, But Not Solved By This Approach

Underlying everything Bhattacharya says is a genuine insight: Americans have lost trust in scientific institutions.

This is real. Polling confirms it. A 2024 Gallup survey found that only 36% of Americans have a great deal of confidence in the scientific community. That's down significantly from decades past.

Why? Multiple factors:

Pandemic-related communication was often poor. Experts changed guidance as evidence accumulated, which is how science works but which the public sometimes interpreted as lying. Messaging sometimes masked genuine uncertainty. In some cases, political considerations influenced scientific guidance.

There's legitimate anger about this. If public health authorities said something with false certainty when they should have said "we're not sure," they damaged trust. When they later changed their minds, they confirmed that the certainty was false.

But trust doesn't get rebuilt by:

- Platforming people who reject evidence on the grounds that this represents democratic truth-making

- Using justified criticism of pandemic overreach to justify unjustified skepticism about vaccines

- Replacing one set of authorities with another set rather than making institutions more transparent and democratic

- Allowing political considerations to shape scientific priorities

Trust gets rebuilt through:

- Clear, honest communication about what we know and don't know

- Accountability for past failures

- Transparent processes for decision-making

- Willingness to acknowledge mistakes

- Consistent application of evidence-based standards regardless of political convenience

- Being humble about the limits of expertise

Bhattacharya's approach does some of the right thing language-wise while potentially undermining the actual mechanisms that rebuild institutional trust.

Estimated data shows vaccine skepticism as the largest component of MAHA beliefs, highlighting the movement's focus on challenging established medical science.

What a Real Scientific Revolution Would Look Like

Let's imagine what Bhattacharya's stated goals would actually require if taken seriously.

If the goal is to rebuild public trust while improving scientific rigor, the first step would be honest reckoning with pandemic decisions. What worked? What didn't? Which policies persisted past their evidence base? Which were justified by evidence we have now but that evidence was uncertain at the time? How do we make decisions better next time when evidence is incomplete?

This would require letting go of using "scientific authority overreach" as a club to beat specific research areas (vaccines, epidemiology) while leaving others untouched. It would require applying rigorous standards uniformly.

Second, actual implementation of the replication revolution would mean:

- Proposing specific mechanisms, not just rhetoric

- Allocating actual resources to replication studies

- Changing NIH peer review criteria explicitly

- Publishing detailed metrics on implementation and outcomes

- Willingness to measure success against explicit benchmarks

Third, rebuilding trust would mean:

- Being transparent about how scientific guidance gets produced

- Making clear distinctions between scientific knowledge and policy decisions

- Acknowledging when science can't answer certain questions and policies must involve other considerations

- Being clear about who decides what (what's a scientific question vs. what's a policy question) and why

None of this is as rhetorically powerful as calling for a "revolution." But it would actually work.

Instead, what we're seeing is revolutionary rhetoric paired with political pragmatism. Bhattacharya wants to satisfy his MAHA coalition by signaling skepticism of scientific institutions while also maintaining his authority within those institutions. He wants to appear to be improving scientific rigor while selectively applying skepticism based on political comfort.

This creates a fundamental instability. You can't simultaneously argue for better science and give platforms to people rejecting evidence on grounds that amount to politics.

How NIH Funding Decisions Will Actually Change

Here's the concrete question that matters: How will Bhattacharya's leadership actually change which research gets funded?

We don't know yet, because he's been vague. But his statements and alliances suggest some possibilities:

Epidemiology and vaccine research: Likely to face increased scrutiny. This isn't stated explicitly, but his willingness to entertain vaccine skepticism in public forums suggests he might deprioritize or scrutinize funding in these areas more carefully.

Alternative medicine and nutrition: Likely to see increased interest. Again, not stated explicitly, but his framing suggests openness to funding research on dietary interventions and alternative approaches that mainstream science has largely found ineffective.

Pandemic research: Likely to face political pressure. Investigating pandemic response might be framed as a higher priority, but likely in ways that presume the response was misguided rather than investigating what worked and what didn't.

Basic science: Could face pressure toward more applied, commercially-relevant research. This has been a trend across government science funding for years, and nothing suggests Bhattacharya opposes it.

The wildcard is whether he actually implements structural changes to how peer review works or whether his "revolution" remains mostly rhetorical.

If he's serious about changing publication incentives and replication standards, that requires changing how grants are evaluated and what criteria matter. That's doable. It would require explicit instructions to NIH grant officers about what they should prioritize.

If he's mostly interested in shifting funding priorities toward research areas he finds congenial, that's also doable, but it's not a scientific revolution. It's a political reorientation.

The Problem of Scientific Authority Without Scientific Humility

There's a paradox embedded in Bhattacharya's position that's worth exploring.

He argues that scientific authorities overstepped during the pandemic by making claims beyond their legitimate domain. Fair point in some cases. But then he positions himself as an authority who will lead a scientific revolution. He's not arguing for less scientific authority. He's arguing for his version of scientific authority to replace the previous version.

This is true of much anti-establishment scientific thinking. It presents itself as anti-authority while actually proposing a different authority. It's not "let's make decisions through democratic processes that balance scientific input with other values." It's "let's make decisions through democratic processes that balance scientific input with values I agree with."

When MAHA advocates claim that vaccines cause problems, they're not appealing to democratic process. They're making factual claims about how vaccines work. Those claims are either true or false. They happen to be false. Appealing to democracy doesn't make false claims true.

Similarly, when Bhattacharya argues that we need to democratize science, what he seems to mean is "we need to let people with different political views have more influence over scientific institutions." That's not inherently wrong, but it's not the same as improving scientific rigor.

A humble approach to scientific authority would acknowledge: Some questions are scientific questions. Some are policy questions. Scientists can inform policy but shouldn't make policy. Policy requires balancing scientific input against other values. That balance is a democratic decision, not a scientific one.

But when scientists disagree about whether vaccines cause autism, that's not a policy question where we balance values. That's a scientific question with a clear answer. Scientists who reject that answer aren't being appropriately humble about the limits of their expertise. They're simply being wrong.

Bhattacharya's framing conflates these two different issues. It uses legitimate humility about scientific authority in policy contexts to justify unjustified skepticism about well-established facts.

Institutional Inertia and the Limits of What One Director Can Change

One thing worth noting: The NIH director has significant authority, but not absolute authority over how science works in America.

Bhattacharya can change:

- Which institutes get budget increases or decreases

- Explicit instructions to NIH officers about review criteria

- Which research areas get emphasized in funding announcements

- Who serves on advisory committees

- How intramural research is organized

- Public statements about scientific priorities

He cannot directly change:

- How universities hire and promote scientists

- How journals decide what to publish

- How scientists in other countries do research

- How private funding organizations decide to fund research

- The fundamental incentives that drive academic careers

This matters because a real revolution in scientific incentives would require coordination across all these actors. A director who only controls NIH funding can shift priorities, but can't fundamentally change the system.

So even if Bhattacharya is completely sincere about wanting a replication revolution (and the evidence suggests he isn't), he would face severe limitations in implementation.

What he can do is use his authority to deprioritize research areas he dislikes and prioritize ones he favors. That's not a scientific revolution. That's politics.

The Question of Integrity: Courting Movements That Reject Evidence

Here's what troubles me most about Bhattacharya's approach, and it's something worth thinking carefully about.

Scientific institutions are imperfect. They make mistakes. They sometimes overstep. They sometimes perpetuate false ideas longer than they should. They sometimes make decisions based on politics rather than evidence.

All of that is true. All of it deserves criticism.

But at the core of science is a commitment to following evidence even when it's inconvenient. A scientist who finds that their hypothesis is wrong should report that. A researcher whose replication attempt finds that prior work was flawed should publish that. An institution that discovers it made a mistake should acknowledge and correct it.

When Bhattacharya courts movements that start with political conclusions and then look for science to justify them, he's abandoning that core commitment. He's signaling that truth is negotiable. That scientific findings can be evaluated based on whether they align with political preferences.

That's not reform. That's corruption.

You can believe that NIH is too large, too bureaucratic, and in need of change. You can believe that publication metrics are bad. You can believe that pandemic policies were overreach. You can believe that some alternative approaches deserve more research attention.

But you can't simultaneously claim to want better science while platforming people who reject evidence on political grounds. Those positions are in fundamental tension.

A leader serious about scientific reform would draw a clear line: We will improve scientific rigor across the board, including in areas that are politically uncomfortable. We will increase funding for replication studies, even if replication studies sometimes confirm things the current administration dislikes. We will apply evidence-based standards uniformly.

Bhattacharya hasn't done that. Instead, he's signaled that his standards are selective. That's the fundamental integrity problem with his position.

What This Means for Research Funding Going Forward

If you're a researcher dependent on NIH funding, you should care about all of this because it directly affects what you can study.

Scenario one: Bhattacharya actually implements specific, measurable changes to improve reproducibility. This involves funding replication studies, changing peer review criteria explicitly, and measuring outcomes. This would be genuinely positive, though not revolutionary.

Scenario two: Bhattacharya uses his authority to shift funding away from research areas he dislikes (vaccines, epidemiology, climate-adjacent health research) and toward areas he favors (alternative medicine, nutrition-focused approaches). This would represent a political reorientation of NIH priorities disguised as scientific revolution.

Scenario three: Some combination of both, where genuine improvements to reproducibility standards are paired with selective application of skepticism based on politics.

The smart money is on scenario three.

Researchers in fields that align with MAHA politics will probably find funding easier. Researchers in epidemiology, vaccine science, and related areas will probably find funding harder. The rhetoric will be about "rigor" and "replication" while the actual effect will be shifting the portfolio toward politically-comfortable research.

This isn't unprecedented in government science funding. The politicization of NIH funding around climate change research, stem cell research, and other politically contentious topics is real and documented. But it's usually more subtle than what Bhattacharya seems to be proposing.

For research areas, the question becomes: How do you navigate an environment where leadership is selective about which evidence-based claims it supports?

The answer, unfortunately, is that you adapt. You emphasize findings that align with the political environment. You downplay findings that don't. You navigate around the politics while trying to maintain scientific integrity.

That's how institutional corruption happens. Not through dramatic events, but through thousands of individual decisions to work within a corrupted system.

The Bigger Picture: What Happens to Science When Politics Intrudes

Bhattacharya's rise represents something larger in American politics: the increasing willingness to treat scientific institutions as legitimate targets for political restructuring.

This isn't unique to the right. The left has also pushed scientific institutions in politically-motivated directions around climate policy and other issues.

But it's worth noting that there's something different about the current moment. Previous politicization of science usually involved arguing about which research areas should be funded or how evidence should be interpreted for policy. The institutions themselves remained committed to evidence-based standards.

What's happening now is more fundamental. It's a challenge to the claim that evidence-based evaluation should be the standard at all.

When Bhattacharya signals openness to vaccine skepticism, he's not arguing that we should fund vaccine research differently based on new evidence. He's signaling that vaccine skeptics have a legitimate place in discussions about vaccine science, regardless of what the evidence shows.

That's different. That's institutional corruption.

Historically, when scientific institutions lose commitment to evidence-based standards, the results are predictable. The institutions become less effective at their core mission. They lose credibility with the public. They become more obviously political. The corruption accelerates.

You don't have to predict the future very far to see where this leads. If NIH leadership prioritizes politics over evidence, researchers will adapt by emphasizing political palatability. The quality of research funded will decline. Replication problems will worsen, not improve. Public trust will continue to decline because people will sense that the institutions aren't actually committed to truth.

The irony is that Bhattacharya's actual goals—rebuilding public trust in science, improving research quality, democratizing truth-making—are legitimate goals that could be achieved through evidence-based institutional reform. But he seems committed to a path that undermines those goals.

FAQ

What exactly is Bhattacharya proposing with the "second scientific revolution"?

Bhattacharya proposes focusing scientific evaluation on replication and reproducibility rather than publication counts. Instead of measuring scientific success by how many papers someone publishes, measure it by whether other scientists can independently verify the findings. The concept is sound, but his specific proposals for implementation remain vague, and his selective application of skepticism based on political comfort undermines claims that this is about rigorous science across the board.

Is the reproducibility crisis in science actually real?

Yes, absolutely. Studies show that a significant percentage of published research doesn't replicate when tested independently. In psychology, one major project found that only 36% of published studies replicated. In cancer biology, an industry study found only 11% replication. This is a serious problem driven by incentive structures that reward novel findings over verification. However, the reproducibility problem has been recognized and discussed by serious scientists for years—Bhattacharya isn't discovering something new.

Why did Bhattacharya appear at a MAHA Institute event?

The MAHA Institute represents a politically important constituency for Bhattacharya's agenda. MAHA advocates are skeptical of scientific institutions and broadly supportive of challenging NIH priorities. By appearing at their event, Bhattacharya signals alignment with vaccine skepticism, skepticism of the pandemic response, and openness to alternative medicine—even though these positions contradict evidence-based science. It's a political calculation, not a scientific one.

What authority does the NIH director actually have?

The NIH director controls approximately $47 billion in annual research funding distributed through 27 different institutes and centers. They can set priorities, influence peer review criteria, decide budget allocations, and shape NIH messaging. However, they cannot directly control how universities hire scientists, how journals publish, or how other funding organizations operate. This limits how much change one director can actually implement unilaterally.

Could an NIH director use their authority to deprioritize research they dislike?

Yes. A director could subtly or explicitly signal that certain research areas are lower priorities for funding. They could change how grant proposals are evaluated. They could make funding announcements that favor certain research directions. This would represent a political reorientation of NIH priorities, though it would probably be justified using scientific language. This is distinct from implementing genuine structural reforms to improve reproducibility.

How does this situation reflect broader trends in science politics?

There's an increasing willingness across the political spectrum to treat scientific institutions as legitimate targets for political restructuring. What makes the current moment distinctive is the degree to which it challenges the fundamental commitment to evidence-based standards itself. Rather than arguing about which research should be funded based on evidence, there's an argument about whether evidence-based evaluation should be the standard at all. This represents a more fundamental form of institutional corruption.

Conclusion: The Choice Between Reform and Corruption

Bhattacharya's "second scientific revolution" presents itself as a genuine attempt to improve how science works. The diagnosis of real problems—publication metrics driving perverse incentives, public trust eroded by pandemic overreach, scientific authorities sometimes overstepping legitimate bounds—is largely accurate.

But the proposed solution is fundamentally compromised by its political context. A revolution genuinely aimed at improving reproducibility and rigor would apply standards uniformly. It would fund replication studies in all fields, including ones with uncomfortable findings. It would be transparent about implementation and measurable outcomes. It would rebuild trust through honest reckoning with past mistakes, not by platforming people who reject evidence.

Bhattacharya's approach does the opposite. It uses legitimate criticism of scientific overreach to justify selective skepticism based on political preference. It signals that vaccine skeptics deserve platforms in scientific institutions. It courts constituencies explicitly hostile to evidence-based science while claiming to improve scientific rigor.

This isn't institutional reform. It's institutional capture disguised as revolution.

The stakes matter. The NIH distributes the funding that enables much of American biomedical research. If leadership uses that power to deprioritize evidence-based research and prioritize politically comfortable work, the effects will ripple through the entire research ecosystem.

Researchers adapt to incentives. Universities and journals adapt to shifting funding patterns. Training programs shift to reward valued research directions. Within a decade, you don't have better science. You have different science, shaped by political considerations rather than evidence.

That's how institutions decline. Not through dramatic failures, but through thousands of incremental decisions to work within a corrupted system.

The good news is that genuine scientific reform is possible. It requires specific mechanisms: funding for replication studies, changed peer review criteria, institutional commitment to rigor regardless of political comfort, transparency about decision-making. These are implementable changes that don't require revolutionary rhetoric or courting constituencies hostile to evidence.

The question is whether the NIH leadership will choose that path or the one Bhattacharya seems to be signaling. Based on the evidence so far—the MAHA event, the vague rhetoric, the selective skepticism—the omens aren't encouraging.

For researchers, research institutions, and the public that depends on quality science, this matters profoundly. Institutions built on commitment to evidence-based standards do better work than institutions corrupted by politics. It's not close.

The second scientific revolution Bhattacharya is proposing doesn't seem to be about making science more rigorous or more trustworthy. It seems to be about making science more politically aligned with a particular constituency. That's a different project entirely, and the honest name for it isn't revolution. It's realignment.

Science will survive this moment, as it has survived previous politicization. The question is whether NIH leadership will choose to strengthen evidence-based standards or selectively apply skepticism based on politics. Everything Bhattacharya has said and done so far suggests the latter.

That should worry everyone who cares about the quality of science or the integrity of institutions.

Key Takeaways

- The NIH director positions his agenda as scientific revolution while courting constituencies explicitly skeptical of evidence-based science

- Real reproducibility problems exist in science, but they require structural institutional changes, not just revolutionary rhetoric

- Bhattacharya's selective application of skepticism based on political comfort undermines claims about improving rigor across the board

- The NIH controls $47 billion in annual research funding, making leadership decisions about priorities consequential for entire research ecosystem

- Genuine scientific reform would require transparent mechanisms, measurable outcomes, and consistent application of standards—which Bhattacharya's approach appears to avoid

Related Articles

- NIH Institute Directorships Politicization: The Power Struggle [2025]

- DOE Climate Working Group Ruled Illegal: What the Judge's Decision Means [2025]

- Flapping Airplanes and Research-Driven AI: Why Data-Hungry Models Are Becoming Obsolete [2025]

- The Fake War on Protein: Politics, Masculinity & Nutrition [2025]

- Pharma Execs Strike Back: RFK Jr.'s Vaccine Agenda Under Fire [2025]

- Appeals Court Blocks Trump's Research Funding Cuts: What It Means [2025]

![NIH's Second Scientific Revolution: COVID Anger, MAHA Politics, and Real Reform [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/nih-s-second-scientific-revolution-covid-anger-maha-politics/image-1-1770664130043.jpg)