The Quiet Exodus: How Venture Capital's Power Structures Are Shifting

When a 15-year veteran of one of Silicon Valley's most influential firms decides to walk away, it's worth paying attention. Niko Bonatsos, the investor behind Discord and Mercor, just left General Catalyst to start his own venture capital firm. On the surface, it's a single personnel move. But it's actually a window into something much bigger happening in venture capital right now.

For the past decade and a half, Bonatsos built a reputation at General Catalyst as someone who could spot talent before anyone else noticed them. He backed Discord when it was a scrappy gaming chat app. He invested in Mercor when most people hadn't heard the name. These weren't lucky bets. They were the result of a specific investment philosophy: finding brilliant founders early, betting on them hard, and letting them build.

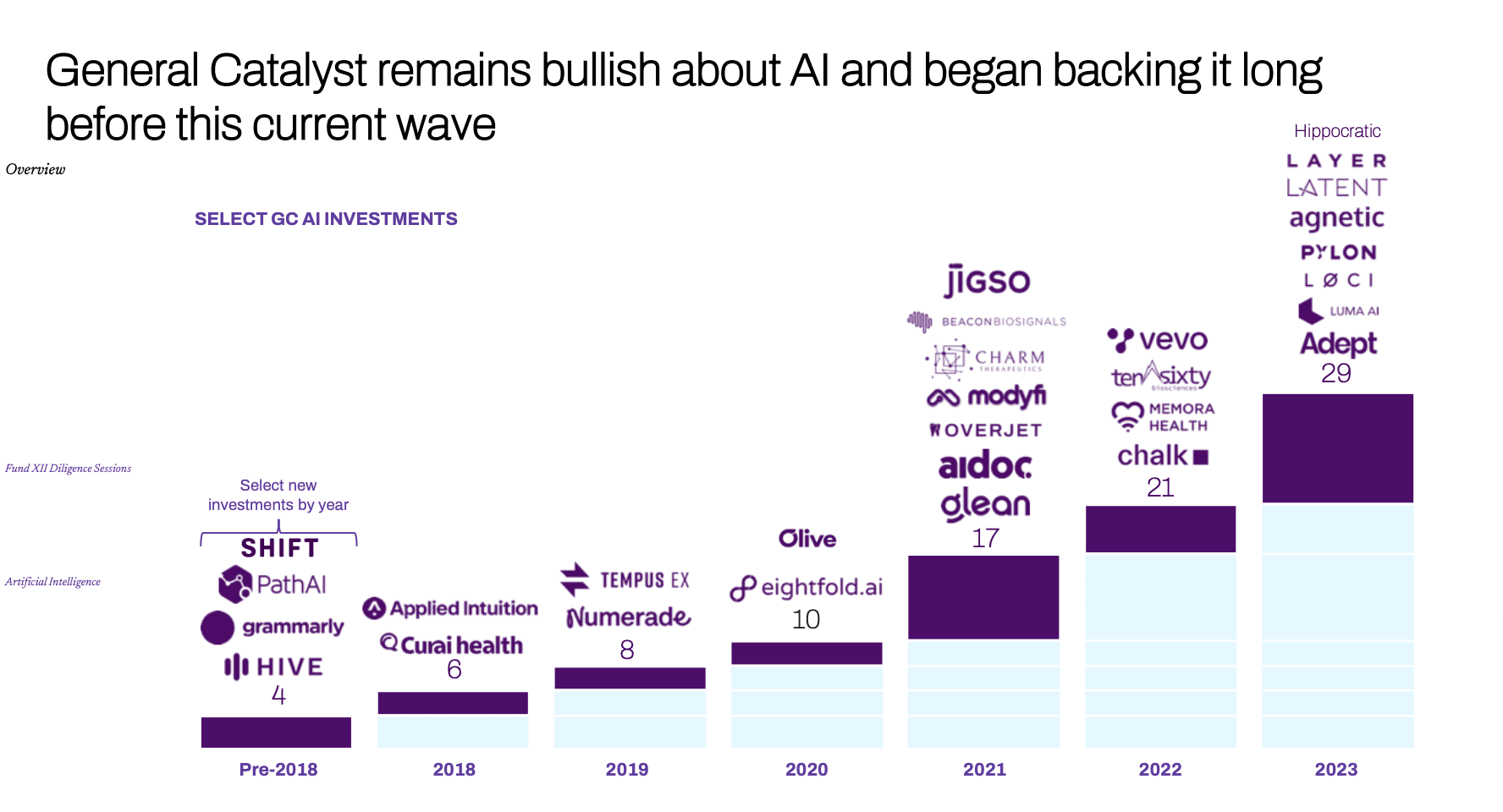

But here's the thing. The venture capital industry is transforming in ways that make those kinds of bets harder to make at mega-firms like General Catalyst. The firm has diversified into wealth management, private equity roll-ups, and customer value financing. It's become what it calls an "investment and transformation company." That transformation is efficient, profitable, and smart. It's also not the place where a dedicated seed investor wants to spend the next 15 years.

Bonatsos is one of several senior investors leaving General Catalyst. Deep Nishar and Kyle Doherty, who led the firm's late-stage "Endurance" strategy, departed. Adam Valkin, who co-led early-stage investing alongside Bonatsos, also left. These aren't disgruntled employees quitting under pressure. These are proven investors making calculated decisions about where they can do their best work.

What makes Bonatsos's move particularly significant is his thesis for his new firm. He's explicitly focusing on young founders, a demographic he was backing years before it became fashionable. He's also interested in consumer AI, a sector he views as underappreciated while the market floods with enterprise tools. These aren't experimental bets. They're the accumulated wisdom of someone who spent 15 years learning how venture capital actually works.

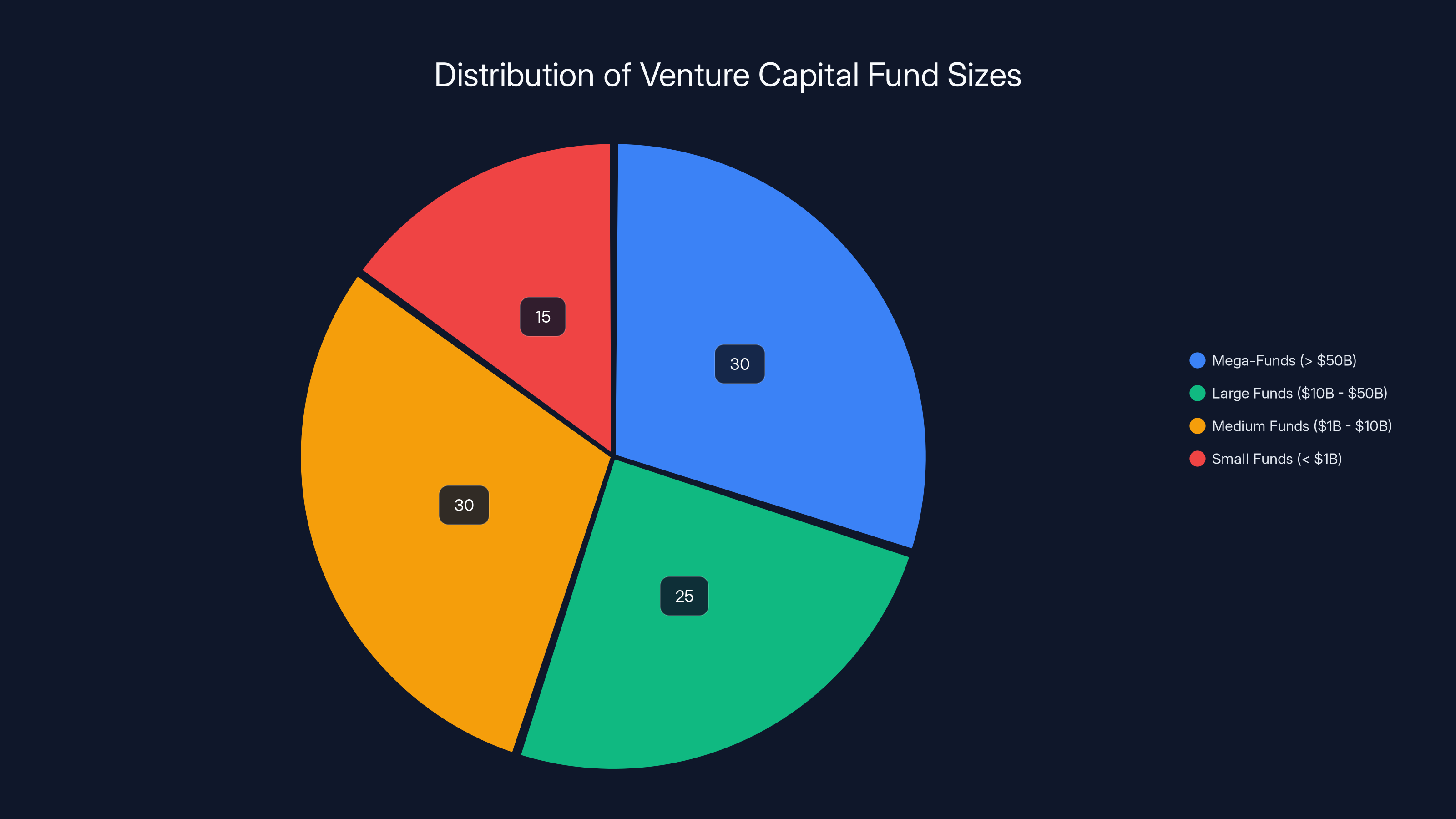

The venture capital industry loves to talk about disruption and change. It's less comfortable with the disruption happening within itself. Over the last few years, the traditional VC model has been under pressure. Fund sizes have ballooned. Average check sizes have increased. The economics have shifted in ways that make seed investing less profitable than growth investing. When mega-firms expand into new financial services, they're making rational decisions about future returns. When investors like Bonatsos leave to start new firms focused on seeds and early stage, they're making a different kind of decision. They're choosing expertise over scale.

This matters because it affects how startups get funded, which investors get heard at board meetings, and ultimately, which technologies get built. When the best investors at the best firms leave to start smaller, more specialized operations, the capital markets fragment. That fragmentation can be good or bad depending on your perspective. It creates opportunities for specialized expertise. It also means that smaller firms are competing with mega-funds for the same early-stage deals. The playing field isn't leveling. It's just becoming more complicated.

Bonatsos has yet to name his firm, secure a team, or begin fundraising. But based on everything we know about his track record and his stated priorities, his new operation will focus on early-stage founders, particularly those under 30, particularly those building in consumer spaces. That's a specific thesis. And if his history is any guide, it's one he's thought about carefully.

General Catalyst's Evolution: From Pure Venture to "Investment and Transformation Company"

General Catalyst didn't wake up one day and decide to become a conglomerate. The transformation happened gradually, responding to market conditions and investor demand. The firm started as a traditional venture capital operation. Like most VCs in the 2000s and 2010s, it raised money, picked companies, added value, and got returns. It was good at it too. The firm backed successful companies, built strong relationships, and earned the trust of founders.

But the venture capital industry was changing. As fund sizes increased and deal complexity grew, pure venture investing became less appealing to large institutional investors. They wanted more. They wanted diversified revenue streams. They wanted ways to deploy capital that weren't dependent on the 7-10 year exit cycle. General Catalyst saw this shift and adapted.

The firm's wealth management business came first. That makes sense. If you're managing large sums for institutional investors, they want access to your best opportunities. A wealth management arm lets General Catalyst offer privileged access to its portfolio companies at earlier stages, or at better valuations. It's a natural extension of existing relationships.

Then came the AI roll-up strategy. This is where things get interesting. Roll-ups are traditionally a private equity move. You buy a fragmented industry, consolidate operations, cut costs, and sell for a multiple. Applied to AI, the thesis is that while everyone's building AI tools, few are building the infrastructure and operational backbone that tie them together. General Catalyst's AI roll-up strategy targets this gap. It's profitable because it creates operational leverage. It's also very different from betting on founders.

The Customer Value Fund (CVF) came next. This is arguably the most clever innovation. The CVF takes successful SaaS and software companies with predictable recurring revenue and provides non-dilutive financing secured by that revenue. It's not venture capital. It's more like a hybrid between debt and equity. The company keeps its cap table clean. General Catalyst gets returns based on cash flow. Everyone wins, at least in theory. In practice, this product attracts companies that are past the seed stage, past Series A, sometimes even past Series B. Those companies don't need someone betting on them. They need capital and operational help. That's what General Catalyst provides.

Each of these business lines is smart. Each one is profitable. Each one has attracted sophisticated investors and proven capital. But each one also requires a different kind of investor. Someone who can spot a young founder and take a risk on them is not the same person who can structure a roll-up or manage a recurring revenue financing vehicle. The skills are different. The time commitment is different. The kind of relationships you need are different.

When Bonatsos left General Catalyst, he was heading the firm's seed strategy. That meant he was one of the few people in the organization whose primary focus was on young founders and early-stage companies. As the firm evolved, that became a smaller and smaller part of the overall operation. It wasn't that General Catalyst stopped making seed bets. The firm did, in fact, hire Yuri Sagalov, a former YC partner, to lead seed investing in the US. But the organizational attention and incentive structures shifted. Seed became one line item in a much larger portfolio.

For an investor like Bonatsos, whose entire identity and track record is built on seed investing, that shift creates a dilemma. You can stay at the firm and adapt to its new structure. Or you can leave and build something aligned with your expertise. Bonatsos chose the latter. That decision tells you something important about how successful investors think about their own careers. They're not chasing the biggest firm or the highest salary. They're seeking alignment between their skills and their role.

Discord reached over 150 million users and a valuation exceeding

The Bonatsos Track Record: From Discord to Mercor

It's hard to overstate how good Niko Bonatsos is at picking young founders. His investment thesis isn't complicated. Find smart people. Believe in them early. Back them with real capital and real support. The results speak for themselves.

Discord might be his most famous bet. The platform launched in 2015 as a chat app for gamers. At the time, voice communication tools were fragmented. Gamers used Skype, Team Speak, and a dozen other solutions. None of them were particularly good. Discord was purpose-built for gaming communities, with low latency, reliable servers, and a clean interface. It sounds simple. Building it was anything but.

Bonatsos saw Discord when it was still finding its footing. The founders had good instincts, but they weren't guaranteed to succeed. The gaming communication space was crowded. There were well-funded competitors. The risk was real. Bonatsos bet on the team and the vision anyway. Discord went on to reach 150+ million users. The company sought an IPO in 2021 and is now worth significantly more. That single investment generated returns that would justify an entire fund.

Mercor is another example. The startup was founded by Brendan Foody, a college dropout who believed that AI agents could fundamentally change how work gets done. At the time Bonatsos backed Mercor, the AI agent space was nascent. Everyone was talking about it. Few companies had found genuine product-market fit. Foody had a vision for how AI agents could be deployed at scale, integrated with existing software, and trained by individual developers.

Mercor reached a $10 billion valuation in a relatively short time. That's not luck. That's pattern recognition. Bonatsos saw something in Foody and his vision that others missed or undervalued. He made the bet. The bet paid off spectacularly. Now Bonatsos is attempting to replicate that success systematically through a new fund.

What's interesting about Bonatsos's track record is that he succeeds not because he picks hot categories, but because he picks exceptional founders. Discord wasn't special because gaming was a huge market. Gaming was already huge. Discord was special because Jason Citron and Stan Vishnevskiy built something better than what existed. Mercor wasn't special because AI was hot. AI was already hot. Mercor was special because Brendan Foody had a unique vision about how AI agents would be deployed.

Bonatsos's approach to founder selection appears to be pattern-matching on founder quality rather than category selection. This is counterintuitive to how many VCs operate. Many investors start with a thesis about what categories will be big, then search for founders to bet on within those categories. Bonatsos seems to work backwards. He identifies exceptional founders, understands their vision deeply, and then makes a bet based on his confidence in their execution.

This approach has advantages and disadvantages. The advantage is that you're not constrained by category predictions. You're betting on people who might surprise you in unpredictable ways. The disadvantage is that it requires deep founder relationships and exceptional pattern recognition. You can't systematize it. You can't scale it with junior analysts. You have to do the work yourself.

For a new founder-led VC firm, this is actually ideal. Bonatsos is explicitly planning a small operation with "friends" who are themselves "at the top of their game." That's not a traditional VC firm structure. That's more like an investment syndicate or a partnership. Multiple great investors, each with their own networks and instincts, collaborating to back exceptional founders. It's the opposite of the mega-fund model. And based on Bonatsos's track record, it might actually work better for early-stage investing.

Estimated data shows a balanced departure across different investment focus areas, indicating a broad shift in venture capital leadership strategies.

The Founder-First Philosophy: Why Young Founders Matter

Bonatsos has stated that his new firm will focus on backing young founders, a trend he identified years before it became fashionable. This isn't a recent revelation. It's a long-standing conviction that shaped his investment decisions at General Catalyst. Now, with his own firm, he can pursue that conviction without compromise.

Why young founders? There are several practical reasons. Young founders often have less to lose. They haven't built careers that they might be risking. They haven't accumulated significant assets that require protecting. They're willing to take bigger risks because they have a different risk calculus. That willingness often translates to bolder product decisions and faster iteration.

Young founders also tend to think about problems differently. Someone who grew up with the internet as an assumed fact approaches technology problems differently than someone who remembers the pre-internet world. Someone who's experienced AI as a normal part of computing approaches AI integration differently than someone who remembers when AI was science fiction. This perspective difference is valuable because it often leads to novel solutions.

There's also a network effects benefit to backing young founders early. When you invest in a 22-year-old founder with an unconventional idea, and that founder builds something successful, they remember who believed in them when everyone else was skeptical. That founder becomes part of your network. Their future companies, their investments, their advice and introductions, all flow through your network. Over time, that creates a flywheel effect.

Mercor's Brendan Foody is the perfect example. Foody was young when he founded Mercor. He had the conviction to drop out of college to pursue his vision. Those weren't reckless decisions. They were calculated risks taken by someone with exceptional confidence in his ability to execute. Bonatsos recognized that quality and backed him. Now Foody is building one of the most valuable AI companies of this generation. The relationship compounds in value over time.

The "young founders" thesis also has a counterintuitive advantage in capital efficiency. When you back a young founder with a big vision but minimal track record, you do it at a low valuation. A typical Series A for a young founder might value the company at 20-50 million dollars. If that company becomes a multi-billion dollar enterprise, the return multiple is extraordinary. Compare that to backing a founder with a strong track record. That founder can probably raise at a higher valuation, which means lower return multiples for early investors. Young founders create better return opportunities for early-stage VCs.

Bonatsos's focus on young founders also signals something about his values. He's not saying he only wants to back Gen Z or that age is the only factor. He's saying he sees structural advantages in backing founders early in their careers, before conventional success and social proof have constrained their thinking. That's a philosophy. And it's one that's been validated by his track record.

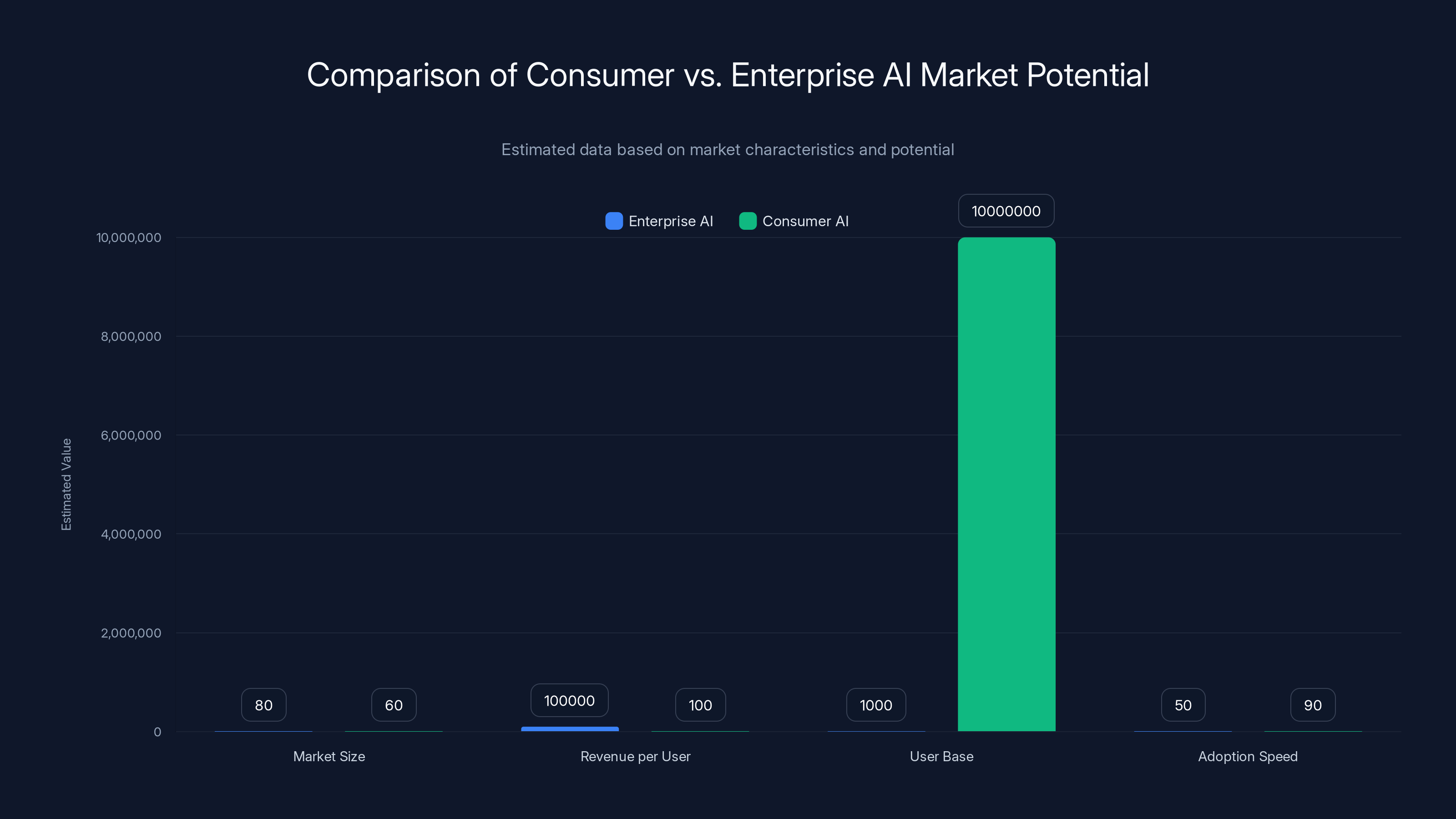

Consumer AI: The Underappreciated Category

Bonatsos also stated that he views consumer AI as underappreciated relative to enterprise AI. This is interesting because enterprise AI has gotten almost all the attention and capital in the recent AI boom. Companies building enterprise AI tools have raised enormous sums. The enterprise market is bigger, purchasing cycles are longer, and customer lifetime value is higher. From a pure financial perspective, enterprise makes sense.

But Bonatsos sees an opportunity in consumer AI that others are missing or ignoring. Consumer AI products are different. They have to be delightful, not just functional. They have to create genuine value that users understand and appreciate. They have to be easy to use, not just capable. These constraints are harder to satisfy. But when you get it right, the results are different too.

Consumer AI also has different unit economics. An enterprise AI product might sell for 10,000 or 100,000 dollars per year per customer. A consumer AI product might sell for 10 or 100 dollars per year per user. But the consumer product can have tens of millions of users. The scaling is different. The network effects are different. The cultural impact is often different too.

Look at what happened with Chat GPT. That was a consumer product. It was a simple interface to an underlying AI model. Users could interact with it for free or pay a monthly subscription. The simplicity and accessibility created massive adoption. That adoption created network effects through sharing and word of mouth. It also created a data and feedback flywheel that helped improve the underlying model.

Bonatsos is betting that the next generation of successful AI companies will include consumer-facing products. Not consumer versions of enterprise products, but genuinely consumer-first AI applications. Things that solve real problems for real people, that create delight, that are worth paying for or worth using even with ads or other business models.

This contrarian position also reflects market dynamics. Enterprise AI is saturated. Every major company is building it. Every VC is chasing it. The returns are getting compressed as more capital floods the category. Consumer AI has received less attention and capital relatively speaking. That means better opportunities for new entrants. It also means founders building consumer AI might get better terms and fewer competitive pressures than founders in the enterprise space.

Bonatsos's conviction about consumer AI also suggests something about his market view. He's not saying enterprise AI is bad or won't be successful. He's saying that the best opportunities and the least crowded field exists in consumer applications of AI. That's a thesis he can test through his new fund.

Estimated data suggests that Niko Bonatsos's new fund will primarily focus on young founders and consumer AI products, with a smaller portion dedicated to other consumer-focused businesses.

Why Venture Capital's Mega-Fund Model Is Struggling

Bonatsos's decision to leave General Catalyst and start his own firm needs context. It's not just about Bonatsos. It's about structural problems in the mega-fund model that's dominated venture capital for the past decade.

Venture capital has experienced massive fund growth. The top 20 firms manage hundreds of billions of dollars. Some firms manage over 100 billion dollars. That scale creates problems, not solutions. With that much capital to deploy, firms have to make bigger checks. Instead of writing 2 million dollar checks to promising seed companies, they're writing 20 million dollar Series A checks. That's a different business. You're not taking as many risks. You're not backing founders as early. You're competing on operational value and network, not founder relationships and instinct.

Mega-funds also create pressure to diversify. If you have 100 billion dollars, you can't put it all in venture capital. You need other asset classes. You need different revenue streams. You need to be a platform. That's not inherently bad. But it changes incentives. A portfolio manager at a mega-fund has to think about the fund as a whole, not about whether backing this particular young founder is the best use of his or her time. There's organizational overhead and decision-making complexity.

There's also the problem of investor power consolidation. When a few mega-funds control most of the capital, they have outsized influence. They can dictate terms to companies. They can influence board composition. They can shape how industries develop. For founders, this is both good and bad. Good because it's easier to raise money from mega-funds. Bad because you're giving up more control and influence to a much larger organization.

Bonatsos's departure, combined with others leaving General Catalyst, suggests that exceptional investors are reaching a breaking point with the mega-fund model. They're realizing that being part of a large, diversified platform comes at the cost of focus and expertise. Megafunds are good at many things. They're not always good at backing young founders with early-stage ideas.

The startup of new, smaller, more focused VC firms is a natural market response to this problem. It creates differentiation. It allows exceptional investors to pursue their specific theses without organizational constraints. It also creates a different competitive dynamic. Instead of competing head-to-head with mega-funds for the same companies at the same stages, smaller firms can pursue different founders, different categories, different geographies.

This fragmentation of venture capital actually creates opportunities for founders. If you're a young founder with an unconventional idea, you might find a better fit at a specialized seed fund run by someone like Bonatsos than at a mega-fund. The mega-fund might be faster with a larger check. But the specialized fund might provide better advice, more aligned incentives, and genuine conviction in your long-term vision.

The Team Question: Building the Right Partnership

Bonatsos has said he's building his new firm with "friends" and people "at the top of their game." He hasn't specified team size or named specific partners. But this phrasing tells you something important about how he's approaching fund building.

He's not trying to build a traditional VC firm with a hierarchy. There's a general partner, junior partners, associates, and analysts. Instead, he seems to be building a partnership. Multiple equals, each bringing their own expertise and network, collaborating on investment decisions.

This approach has trade-offs. The advantage is alignment. If everyone is a partner and everyone has skin in the game, everyone cares about the fund's performance. There's no political hierarchy or jockeying for position. The disadvantage is that partner alignment is hard. You need people with compatible working styles, similar risk tolerances, and overlapping but not identical theses. Finding and keeping that team together requires deliberate effort.

Bonatsos is probably well-positioned to pull this off. By nature of his track record, he has relationships with other exceptional investors. People who've worked with him at General Catalyst or before would understand his approach. People who've followed his investments or crossed paths with him in the industry know his quality. He can probably call people at the top of their game and they'd take the conversation seriously.

The other interesting implication of the partnership approach is that it suggests smaller fund size. A partnership of 4-6 exceptional investors managing 200-500 million dollars makes sense. A partnership of the same size trying to manage a billion dollars would be unwieldy. This suggests Bonatsos's fund will be smaller and more focused than mega-funds. That's intentional. Smaller funds can make faster decisions. They can back smaller rounds. They can take more risks because losing one or two investments doesn't sink the fund.

General Catalyst's evolution shows a gradual shift from pure venture capital to diversified strategies including wealth management, AI roll-ups, and the Customer Value Fund. Estimated data.

Naming the Fund: Branding and Identity

Bonatsos hasn't chosen a name for his fund yet. That might seem like a minor detail, but it's actually significant. A fund's name signals its thesis, its identity, and its culture.

Some VCs use their own names. Khosla Ventures. Founders Fund. That signals that the fund is built around the founder's reputation and expertise. Some VCs use thematic names. Andreessen Horowitz chose a name that invokes its founding partners. Y Combinator chose a name that's memorable and somewhat whimsical.

Bonatsos's decision to not yet have a name suggests he's thinking carefully about what the fund should represent. He's probably testing different names with potential partners and potential founders. He wants something that's memorable, that signals his thesis, and that's available as a domain and on social media.

The naming process also reflects something about Bonatsos's approach. He's not rushing. He's building deliberately. Before he raises money, before he announces his fund publicly, he's making sure all the pieces are in place. The name, the team, the thesis, the operational infrastructure. That's the sign of someone who's thought carefully about what can go wrong.

The Fundraising Timeline: Building in Stealth

Bonatsos has also said he hasn't begun fundraising for the new fund. That's interesting because it means he's still in the planning phase. He's probably having conversations with potential limited partners. He's probably testing ideas with potential founders. But he's not out there raising money yet.

This is strategic. When you announce a new fund publicly, you start a clock. Limited partners expect you to deploy capital within a certain timeframe. Founders start sizing you up. Other VCs start watching you. You're no longer flying under the radar. You're a announced competitive force.

Bonatsos is probably building his fund in relative stealth. He's securing commitments from people he trusts. He's identifying founders and categories he wants to focus on. He's building operational infrastructure. When he does announce the fund and formally begin fundraising, he'll be ready. He'll have a clear thesis, a proven team, and probably some founders ready to take money.

The timing also matters. Venture capital fundraising is cyclical. Sometimes LPs are eager to deploy capital. Sometimes they're cautious. Bonatsos is probably watching the market and looking for the optimal window to raise. He might wait until macro conditions are better, or until he has a specific achievement that makes his fund more compelling to LPs.

Mega-funds, managing over $50 billion, constitute 30% of the top venture capital firms, highlighting the concentration of capital and influence. Estimated data.

The Broader VC Exodus: A Pattern Emerges

Bonatsos is not alone. As mentioned, Deep Nishar and Kyle Doherty left General Catalyst. Adam Valkin also departed. These are not anomalies. There's a clear pattern of senior investors leaving mega-funds to start new ventures.

This pattern reflects several things. First, it reflects the limitations of the mega-fund model for exceptional investors. At a certain level of skill and reputation, you want to do things your way, not the organization's way. You want to pursue your specific thesis without organizational constraints.

Second, it reflects generational dynamics. Many of the investors leaving mega-funds are now in their 40s, 50s, or even older. They've spent decades at large firms. They've accumulated capital and reputation. They can now do something they couldn't do 10 or 20 years ago. They can raise their own fund and maintain full control over strategy and operations.

Third, it reflects market opportunities. The venture capital market is big enough now that there's room for specialized operators. You don't have to be a mega-fund to be successful. You can be a focused, specialized fund with a clear thesis and a strong track record. Limited partners will back you if they believe in your approach.

This exodus also creates instability at mega-funds. When your best investors leave, what does that mean for the fund? It probably means they've lost faith in the organizational approach. It probably means other senior investors are considering their options. It probably means the fund needs to rebuild its investment capabilities and rebuild founder relationships.

For founders, this exodus is probably positive. It means more capital is available from specialized investors with deep expertise. It means more competition for great founders from multiple sources. It means better terms and better alignment might be available outside mega-funds.

The Market for Early-Stage Capital: Structural Changes

Bonatsos's new fund is entering a market for early-stage capital that's undergoing structural change. The traditional seed round used to be 250,000 to 2 million dollars. Now, seed rounds are often 5-20 million dollars or more. That's changed the market. It's created room for super-seed funds and growth funds that are larger than traditional seed funds but smaller than traditional Series A funds.

It's also created room for specialized early-stage funds. If super-seed funds are focused on 5-20 million dollar rounds, there's still capital needed for smaller rounds. Pre-seed rounds, micro-seed rounds, founder-led funding rounds. Those categories are now being filled by angel investors, syndicate platforms, and emerging fund managers.

Bonatsos's new fund will probably focus on this market. Series A sized rounds for young founders. 2-10 million dollar checks to exceptional teams building novel things. That's a market that mega-funds have increasingly abandoned because it's not efficient given their fund sizes.

This market is also increasingly global. While US venture capital still dominates, there's growing capital from international sources. European funds are building global practices. Asian funds are expanding into the US. This creates more competition but also more capital overall.

Enterprise AI dominates in market size and revenue per user, but Consumer AI excels in user base and adoption speed. Estimated data highlights potential of Consumer AI.

Consumer AI: Specific Opportunities

When Bonatsos says he's interested in consumer AI, what specifically might he be backing? There are several categories where consumer AI could have meaningful impact.

Personal productivity AI is one. Tools that help individuals manage their time, their tasks, their information. These could be AI assistants, AI search tools, AI writing assistants, or AI planning tools. The market is large and growing as people realize AI can genuinely help them do things better.

Creative tools are another. AI for image generation, video generation, music generation, writing generation. These tools are becoming more accessible and more useful. Creators are starting to adopt them. There's genuine revenue potential in tools that help creators be more productive or more creative.

Education and learning is a third category. AI tutors, AI learning assistants, AI study tools. These create personalized learning experiences at scale. They're not perfect, but they're improving, and they address a real market need.

Health and wellness is another. AI fitness coaches, AI nutrition advisors, AI sleep tools. These create personalized recommendations at scale. They're becoming increasingly effective as they're trained on more data.

Social and community tools are yet another. AI-powered social networks, AI community management tools, AI for matchmaking or introductions. These take advantage of AI's ability to understand patterns in human behavior and preferences.

The key characteristic all of these have in common is that they're consumer-facing, they solve real problems, and they create genuine value for users. They're not just wrapper products on top of Chat GPT's API. They're thoughtfully designed experiences that use AI as a tool, not as the product itself.

The AI Age and Founder Demographics

Bonatsos's focus on young founders becomes even more relevant in the context of AI. The AI boom has created a new category of founder: young AI engineers and researchers who are starting companies to implement their ideas.

Brendan Foody at Mercor is exactly this type. He's a talented engineer with a specific vision about AI agents. He didn't wait to get permission. He didn't build a career at another company first. He saw an opportunity and built it.

This pattern is becoming more common. Young AI engineers are starting companies at earlier ages than previous generations. They're getting funded at higher amounts. They're reaching significant valuations more quickly. This is not a temporary phenomenon. It's a structural shift in how startups get founded and funded.

For an investor like Bonatsos, this shift is perfect. His thesis about young founders aligns precisely with what's happening in the market. Young founders are proving themselves as the driving force of the current wave of technology. Betting on them is not contrarian. It's actually reading the market correctly.

Operational Value vs. Capital: The New Competition

As venture capital has evolved, the primary value proposition has shifted. 20 years ago, capital was scarce. The primary value a VC provided was money. Now, capital is abundant. Every good founder can raise capital. The primary value a VC needs to provide is operational value and network.

This creates an opportunity for specialized operators. General Catalyst brings operational value through its "transformation company" services. But that operational value is general. Bonatsos brings operational value that's specific: experience with founder dynamics, growth stages, product strategy, and capital raising. That's more valuable for a young founder than generic transformation services.

Similarly, network effects matter more. A young founder doesn't need introductions to every company in the world. They need introductions to the right people: potential hires, potential customers, potential future investors. Bonatsos's network in the startup ecosystem is extremely valuable. His network includes successful founders, downstream investors, and strategic operators. That's a network a young founder can actually use.

This competition on operational value and network, rather than capital, favors specialized operators. A mega-fund can provide capital and generic services. A specialized fund like Bonatsos's can provide capital, specialized operational advice, and a highly relevant network.

The Role of Trust and Relationships

At the heart of early-stage venture capital is trust. Founders need to trust their investors. They're giving up equity and accepting operational input. They're putting their careers in the hands of people who may or may not deliver value. Trust is everything.

Bonatsos has built trust through his track record. Founders know about Discord. They know about Mercor. They know that Bonatsos bet on these founders when the outcomes were uncertain. They know he provided value beyond capital. That track record creates trust with potential founders.

Trust also flows the other way. Limited partners need to trust the fund manager. They're giving capital for 10 years with no control and uncertain returns. They're betting on the fund manager's judgment. Bonatsos's track record creates that trust. LPs know he's backed successful companies. They know he has conviction. They're likely to fund him.

The relationship-based nature of early-stage venture capital actually makes it harder to scale than mega-funds suggest. You can't systematize trust. You can't hire people to build relationships. Trust has to be earned through consistent performance and genuine alignment of interests. That's why smaller, specialized funds sometimes outperform mega-funds in early-stage investing. The smaller fund manager actually has to maintain personal relationships with founders. There's no organizational buffer.

Timing: When Bonatsos Started Vs. Now

It's worth noting that Bonatsos's timing is interesting. He's starting his new fund amid uncertainty and change in venture capital. The interest rate environment is changing. The mega-fund model is showing cracks. Founder expectations are evolving. This is not necessarily the easiest time to start a new fund.

But it might actually be the best time for the right fund manager with the right thesis. When markets are uncertain, differentiated approaches matter more. A mega-fund with a generic approach might underperform. A specialized fund with a clear thesis might outperform dramatically. This is when track record and conviction matter most.

Bonatsos also has the advantage of being a known entity. He's not a first-time fund manager trying to convince people he has the right thesis. He's a proven investor with a decade and a half of successful bets. That makes fundraising easier even in uncertain times.

The AI market is also at an interesting inflection point. The initial wave of AI adoption is happening. Companies are figuring out how AI fits into their products. Early adopters are getting value. Second and third waves of products are being built. For an investor focused on this moment, there's a window of opportunity. That window will eventually close as AI becomes commoditized. Bonatsos's timing, arriving at this moment with a focused fund and a clear thesis, is probably intentional.

Building Institutional Knowledge: From Seed to Scale

One thing that makes Bonatsos valuable is his experience across the full arc of company building. He's backed Discord from seed. He's watched it grow from a small startup to a major platform. He's seen what works and what doesn't at each stage.

That institutional knowledge is invaluable. A young founder making Series A decisions can benefit from Bonatsos's understanding of what happened to his other companies in the same situation. What worked? What didn't? What should we focus on? This is experience that can't be learned from books or case studies. It's learned by doing.

Bonatsos can also provide continuity. If he's backing a founder at seed stage, and the founder grows the company successfully, Bonatsos might be there again at Series A or even later rounds through General Catalyst's various funds. That continuity and long-term relationship is valuable. Founders benefit from investors who understand their trajectory and their long-term vision.

The Future of Venture Capital: Fragmentation or Consolidation?

Bonatsos's move, combined with the moves of other investors leaving mega-funds, raises a question about the future of venture capital. Will the industry continue consolidating into larger and larger mega-funds? Or will it fragment into more specialized, focused operators?

The answer is probably both. Some capital will continue consolidating. Large LPs will continue backing mega-funds because of the operational scale and diversification they provide. But some capital will also migrate toward specialized operators. LPs are realizing that mega-funds, while convenient, don't always deliver the best returns in every category. Specialized funds focused on specific stages, categories, or geographies often outperform.

This suggests a future where venture capital is increasingly a bifurcated market. Mega-funds playing a larger, longer-term game focused on later-stage investments and operational transformation. Specialized funds playing a more focused game, capturing value in specific niches.

Bonatsos's new fund represents this specialized approach. It won't compete directly with mega-funds on later-stage capital. It will compete on early-stage, seed, and Series A investments in categories where Bonatsos has conviction. That's a viable market. It's a growing market. And it's one where track record and expertise matter more than sheer capital size.

What's Next: The First Bet

Bonatsos's first investment will be symbolically important. It will signal what he actually believes about his thesis. Will he back a young AI engineer? A young founder in consumer AI? A founder building in a completely new category? The first bet will tell you a lot about what Bonatsos is actually looking for versus what he's saying in interviews.

That first bet also creates momentum. A successful early investment creates track record for the new fund. It attracts other founders. It attracts other investors as LPs. It signals that the thesis is real and the execution is happening.

Bonatsos will also be watching market conditions. He'll be considering when to announce his fund publicly, when to begin formal fundraising, when to deploy capital. These timing decisions matter. A fund announced at the wrong time, during a market downturn, might struggle to raise. A fund announced at the right time, when LPs are looking for differentiated bets, might raise easily.

The next 6-12 months will probably be quiet for Bonatsos in terms of public announcements. He'll be building the fund, securing team and capital commitments, identifying founders. When he does emerge publicly, the fund will be ready to operate.

FAQ

Who is Niko Bonatsos?

Niko Bonatsos is a venture capital investor who spent 15 years at General Catalyst, where he led the firm's seed investing strategy. He's known for early investments in Discord, the popular gaming and communication platform, and Mercor, an AI startup that reached a $10 billion valuation. His track record of backing successful young founders established him as one of the more respected seed-stage investors in the industry.

Why did Bonatsos leave General Catalyst?

Bonatsos left General Catalyst to start his own venture capital firm focused on early-stage investments. While the departure was mutual and he characterized his time at General Catalyst as positive, the firm's evolution into an "investment and transformation company" with multiple business lines beyond traditional venture capital likely meant less focus on the seed-stage investing that Bonatsos specializes in. His new fund allows him to pursue his specific investment thesis without organizational constraints.

What will Bonatsos's new fund focus on?

Bonatsos's new fund will focus on backing young founders, particularly those under 30, and companies building consumer AI products. He views consumer AI as underappreciated relative to the market attention on enterprise AI tools. He's also interested in builders launching consumer-focused businesses across other categories. He intends to build his fund as a partnership with other exceptional investors rather than a traditional hierarchical venture capital firm structure.

Why does Bonatsos believe in young founders?

Bonatsos believes young founders have structural advantages including lower risk aversion, different perspectives on technology problems, and willingness to pursue unconventional solutions. Young founders also often command lower valuations for early rounds, creating better return multiples for early-stage investors. Additionally, Bonatsos has observed that major AI companies including those with young founder teams are defining the current generation of technology companies.

What does General Catalyst's transformation mean for venture capital?

General Catalyst's evolution into an investment and transformation company reflects broader trends in venture capital where mega-funds are diversifying beyond traditional venture investing into wealth management, private equity roll-ups, and recurring revenue financing. While this diversification creates operational efficiencies and new revenue streams, it also means that traditional seed investing becomes a smaller part of the overall operation, potentially creating opportunities for more specialized, focused venture capital firms like the one Bonatsos is starting.

Is Bonatsos's departure part of a broader trend?

Yes, Bonatsos is one of several senior investors who have recently left General Catalyst. Deep Nishar and Kyle Doherty, who led the firm's late-stage "Endurance" strategy, and Adam Valkin, who co-led the early-stage fund, also departed. This pattern reflects a broader phenomenon in venture capital where exceptional investors with specific expertise are choosing to leave mega-funds to start more focused operations aligned with their investment theses. This reflects limitations of the mega-fund model for achieving deep specialization and individual investor conviction.

What is the consumer AI opportunity Bonatsos sees?

Bonatsos views consumer AI as underappreciated relative to enterprise AI, which has captured most venture capital attention and funding. Consumer AI includes personal productivity tools, creative applications, education platforms, health and wellness products, and community tools that serve individual users. Unlike enterprise AI, consumer AI products must create genuine delight and immediate utility, and while individual customer values are lower, the potential user bases are vastly larger. This category has received less venture capital attention than enterprise AI despite significant market potential.

How will Bonatsos's new fund differ from General Catalyst?

Bonatsos's new fund will be smaller, more specialized, and focused exclusively on early-stage investing in young founders and consumer AI. It will operate as a partnership of exceptional investors rather than a hierarchical firm with multiple business lines. This allows for faster decision-making, more aligned incentives, and deeper focus on founder relationships than is possible in a mega-fund managing hundreds of billions across multiple investment strategies.

What should founders know about Bonatsos's investment approach?

Bonatsos is a thesis-driven investor focused on founder quality over category selection. He makes bets based on exceptional founders and vision rather than chasing hot categories. He provides long-term relationships and continuity across funding stages. His track record includes both extreme successes and presumably some unsuccessful bets, suggesting he takes real risks on early-stage teams. Founders considering his firm should understand that he values founder conviction and bold thinking.

Key Takeaways

- Niko Bonatsos, who backed Discord and the $10B startup Mercor, is leaving General Catalyst after 15 years to launch a new early-stage VC firm

- His departure reflects broader trends of senior investors leaving mega-funds to start specialized, focused operations aligned with their specific investment theses

- Bonatsos's new fund will focus on young founders (particularly under 30) and consumer AI, categories he views as underappreciated and underweighted by mega-funds

- General Catalyst's evolution into an 'investment and transformation company' with multiple business lines means seed investing receives less organizational focus despite continued activity

- The venture capital market is increasingly bifurcating between mega-funds focused on later-stage and operational transformation, and specialized funds focused on early-stage investing expertise

Related Articles

- Where AI Startups Win Against OpenAI: VC Insights 2025

- The 32 Top Enterprise Tech Startups from TechCrunch Disrupt [2025]

- Articul8 Series B: Intel Spinoff's $70M Funding & Enterprise AI Strategy

- CES 2026: Everything Revealed From Nvidia to Razer's AI Tools

- Why Navan's IPO Flopped While AI Companies Soar: The B2B SaaS Reckoning [2025]

- European Deep Tech Spinouts: How 76 University Companies Became Unicorns [2025]