The Biggest Week in Northwood Space's History

Sometimes in startups, everything clicks at once. You're grinding for years, building something nobody fully appreciates, and then suddenly the market catches up. That's what happened to Northwood Space in late January 2026. In one week, the El Segundo, California-based company announced two massive wins that would reshape the trajectory of the entire business: a

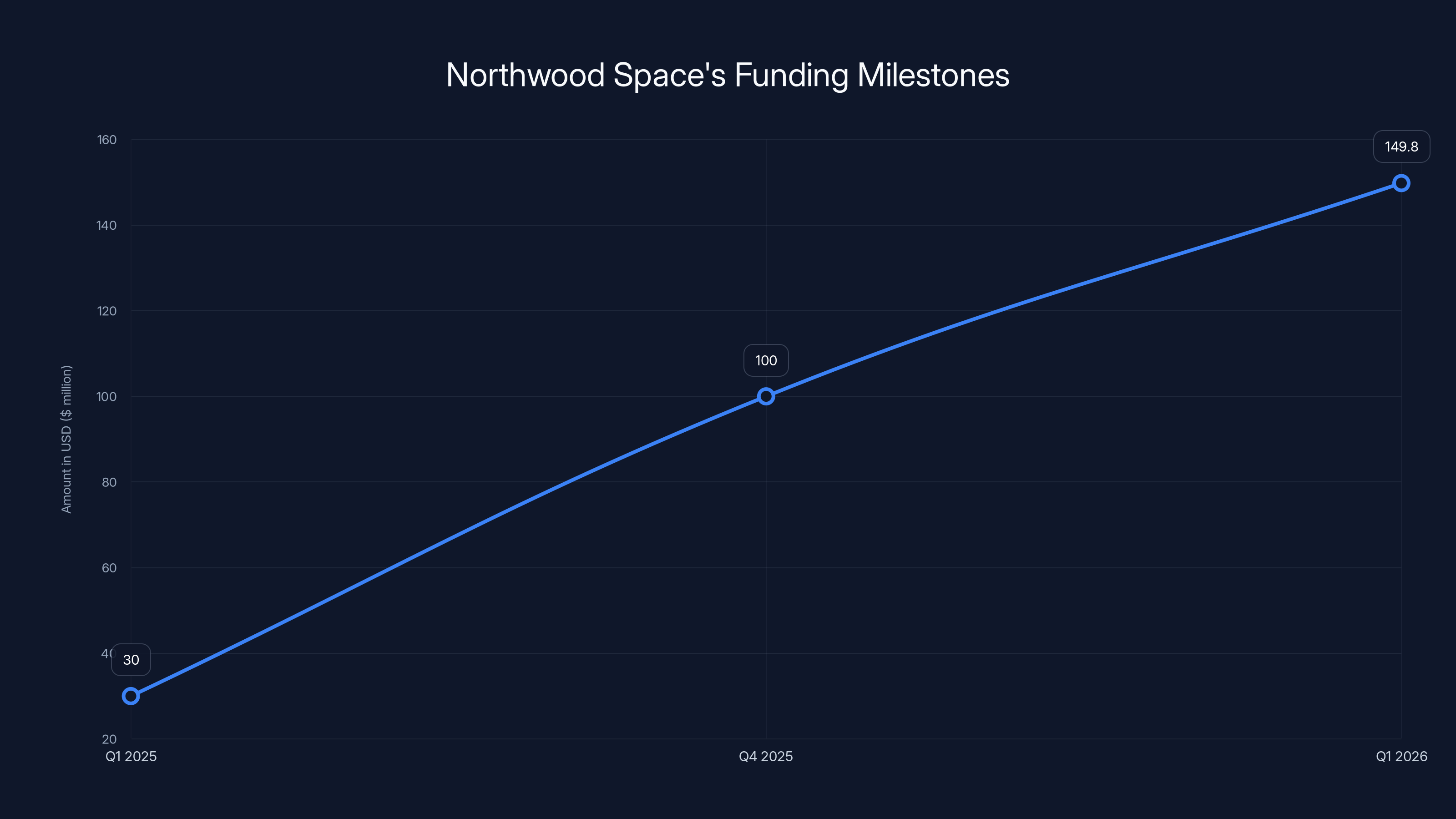

For context, this wasn't some quiet, slow build. Just under a year earlier, Northwood had closed a $30 million Series A. Two major rounds in twelve months. Two entirely separate sources of validation—one from the venture capital world, the other from the U.S. military apparatus. For a company that's still technically in its early growth phase, this was extraordinary.

But here's the thing: it wasn't accidental. Northwood's leadership had been building toward this moment for years. The company's founder and CEO, Bridgit Mendler, framed it perfectly during conversations with reporters at the time. "Yes, this is happening faster than we thought," she said. "You know, two fundraises in the same year and large sums of capital." But then came the crucial caveat: "That's really what we're ready for from a production standpoint."

That distinction matters enormously. Too many startups raise money before they're ready to execute. Northwood wasn't doing that. The capital infusion was coming because the market demand was already there—customers knocking on the door, waiting times extending, the company hitting real constraints. This funding round wasn't about creating demand. It was about satisfying demand that already existed.

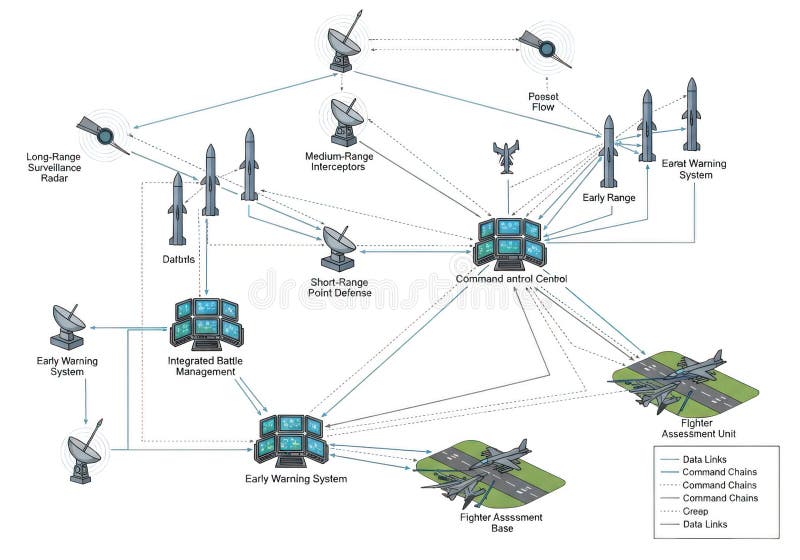

What makes Northwood's story especially compelling is that it's not just about venture capital momentum. It's about a company solving a genuinely hard technical problem that the U.S. military has been wrestling with for over a decade.

Understanding the Satellite Infrastructure Challenge

Before we can fully appreciate what Northwood Space is doing and why it matters, we need to understand the infrastructure problem they're solving. And it's not obvious to most people because it happens entirely on the ground.

When you think about satellites, you picture them in orbit, collecting data or transmitting signals back to Earth. That part is straightforward enough. But here's what most people don't think about: those satellites need to be controlled, monitored, and communicated with constantly. They need to send data down to Earth. They need to receive instructions. They need to be tracked. They need their health monitored.

All of that happens through ground stations.

For decades, the U.S. Space Force relied on what's known as the Satellite Control Network, or SCN. This network includes ground stations equipped with large dish antennas—the kind you might see in Cold War movies, massive physical structures designed to transmit powerful signals to and from satellites in orbit. These systems were impressive engineering achievements for their time. They worked reliably for their intended purpose.

But they have limitations, and those limitations have become increasingly problematic.

First, there's the capacity issue. The SCN was designed to support a certain number of satellites and a certain volume of data flow. But the space industry has undergone a dramatic transformation. Companies like SpaceX, Amazon, and others are deploying massive satellite constellations—not dozens of satellites, but thousands. Meanwhile, Earth observation companies, weather services, communications providers, and military programs all need ground station access. The demand has exploded far beyond what the legacy SCN was designed to handle.

Second, there's the modernization problem. These large dish antenna systems are physically enormous, expensive to build, and difficult to upgrade. They're also vulnerable to single points of failure. If a major ground station goes down, suddenly you've lost all communication and control capability for every satellite it serves.

Third, there's the geographic problem. Building large ground stations requires significant capital investment and real estate. You can't just put them everywhere. This creates bottlenecks where satellite operators need to queue up to use available ground station time, or they have to invest in building their own private infrastructure.

For commercial operators like SpaceX and Amazon, this is manageable because they can afford to build their own ground stations. SpaceX has invested heavily in its own network of stations to support Starlink. Amazon has done the same for Project Kuiper. But for smaller operators, government agencies with different missions, and research organizations, this becomes a significant constraint.

Enter Northwood Space.

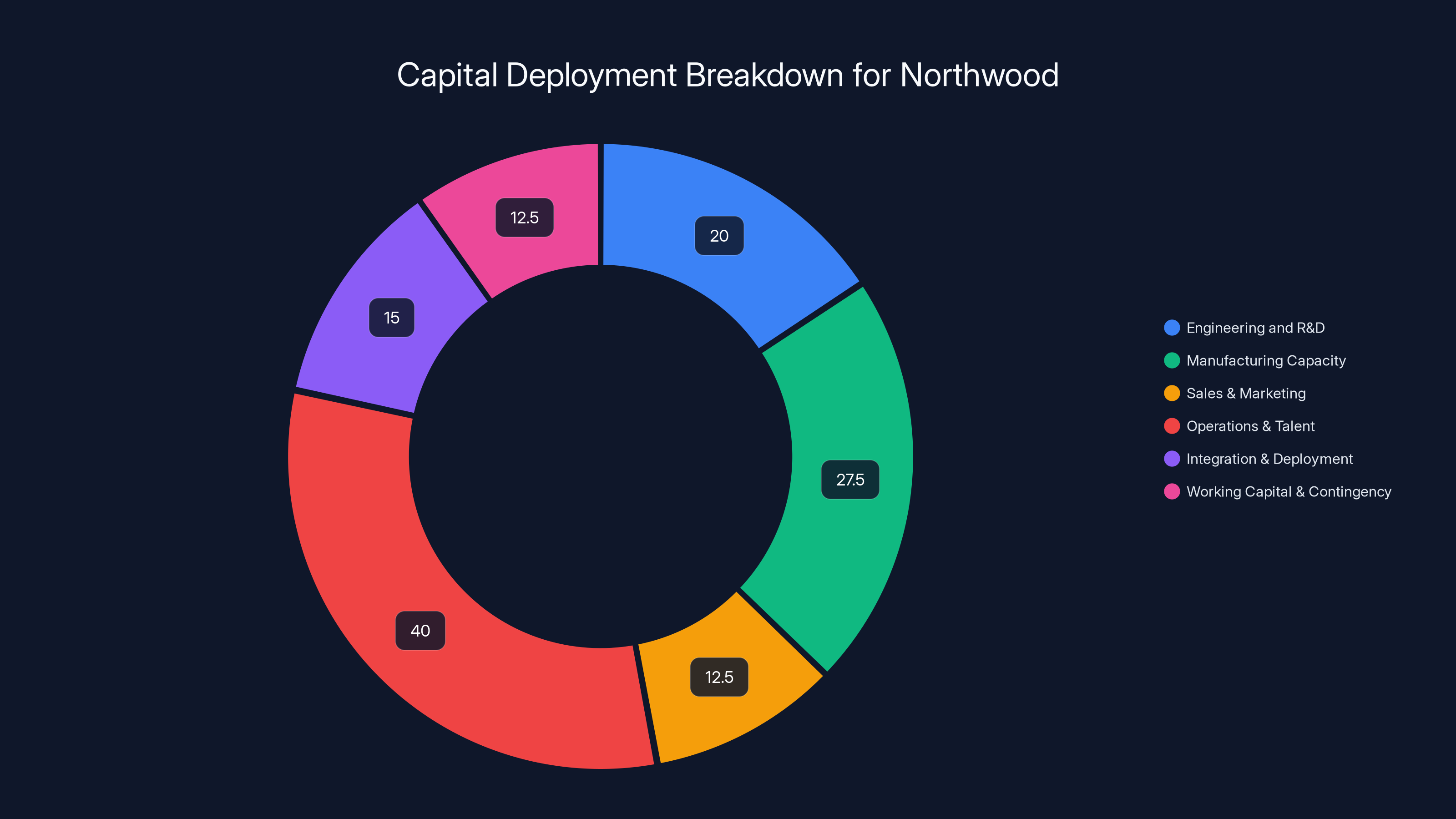

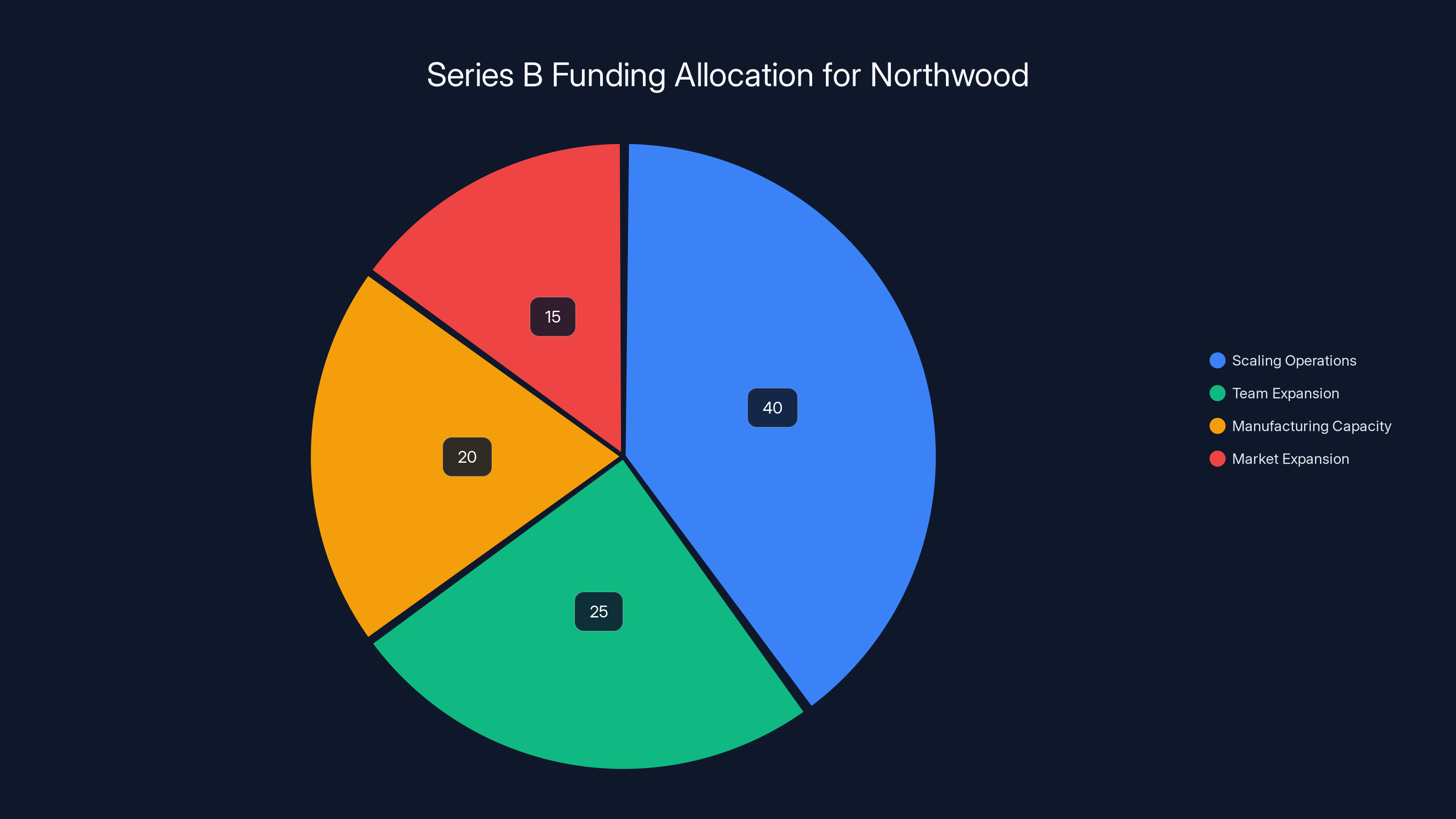

Estimated data shows Operations & Talent acquisition as the largest capital allocation at

The Northwood Approach: Phased Array Antennas

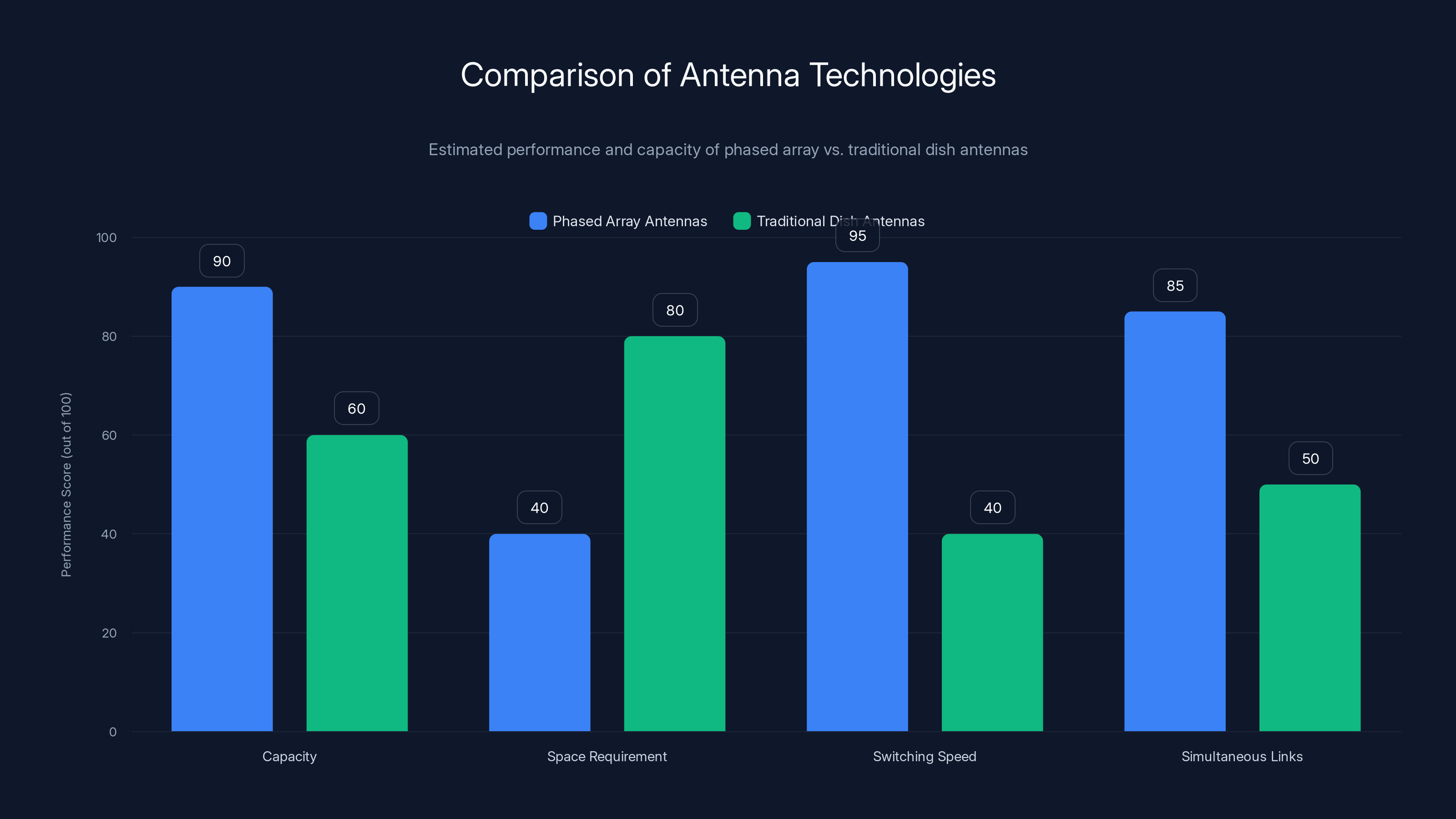

Instead of building giant dish antennas, Northwood Space is deploying what's called phased array antenna technology for ground stations. This is a fundamentally different architectural approach, and understanding why it matters requires digging into some signal processing basics.

A phased array antenna consists of thousands of small antenna elements arranged in a grid pattern. By electronically controlling the phase of the signal sent to each element, you can steer the beam of the antenna without moving any physical structure. It's elegant, really. Instead of a massive rotating dish that must mechanically point toward a satellite, you have a flat array that electronically points the beam wherever it needs to go.

The advantages are significant. First, the physical footprint is much smaller. A phased array system can be deployed in a much more compact space than a traditional dish antenna. Second, it can operate significantly faster than mechanical systems. You can switch between satellites almost instantaneously instead of waiting for a dish to mechanically rotate. Third, it can be modular. You can build a system with a certain capacity and then scale it up by adding more array elements.

For the satellite industry, this is powerful. If you can deploy many smaller ground stations with phased array technology, you suddenly have much more geographic distribution. You're not constrained by a few massive facilities in specific locations. You can build stations wherever it makes sense.

But here's the catch: phased array antenna technology for satellite communications is genuinely hard to implement. It's not impossible, but it requires serious engineering expertise. You need people who understand electromagnetic propagation, signal processing, radio frequency engineering, electronics, mechanical design, software architecture, and systems integration. You need the ability to manufacture components to tight tolerances. You need testing and validation infrastructure.

Most importantly, you need to think about the entire ground station as a system, not just build a radar or communications system in isolation.

This is exactly what attracted venture investors and the U.S. military to Northwood. CEO Bridgit Mendler has been explicit about this advantage: "It's a hard thing to do. It requires a lot of risk, a lot of capital. It requires a lot of diverse skill sets to come together, to be able to really wrap your head around the entire ground station problem."

That's not marketing speak. That's an accurate description of why there's been so little competition in this space. The barrier to entry is genuinely high. It's not a software problem you can solve with the right algorithm. It's not a business problem you can solve with the right marketing. It's an engineering problem that requires substantial capital, time, and expertise.

The Series B Funding Round: Backing Up Rapid Growth

Let's talk about the funding itself. Northwood's Series B was led by Washington Harbour Partners, a Washington D.C.-based venture firm that has been particularly active in space technology investments. The round was co-led by Andreessen Horowitz, one of the most prominent venture firms in the world.

The $100 million raise is substantial. For context, that's larger than the entire A-B combined raises for many startups. But for Northwood, it makes sense given where they are in their growth trajectory.

Mendler was direct about the capital's purpose. This wasn't money to build the product or figure out product-market fit. Northwood had already achieved that. The capital was for rapid scaling. "We get customers coming to us all the time requiring a ground solution, wanting us to help think through a ground problem with them, and we don't want there to be a resource constraint that blocks us from being able to support that mission," she explained.

This is the inflection point many venture-backed companies are chasing. You've validated that customers want your product. You've proven you can build it and deliver it. Now you need to scale operations, expand your team, add manufacturing capacity, and reach new customers before a competitor does. This is when large capital infusions make sense. This is when you can deploy money effectively and see direct returns on that capital.

Washington Harbour Partners' involvement is particularly meaningful. The firm has carved out a niche investing in space technology companies. By backing Northwood, they're signaling confidence not just in the company, but in the entire sector's momentum. This matters for narrative and momentum.

Andreessen Horowitz's participation is equally significant, though perhaps for different reasons. A16z has a history of backing ambitious technical founders solving hard problems. Ben Horowitz and Marc Andreessen have been explicit that they're interested in "the real stuff," not just consumer apps or software-as-a-service plays. Northwood fits that thesis perfectly.

The timing of the raise is also notable. This happened in late January 2026, which means the funding was likely secured before the end of 2025. This was during a period of renewed optimism in venture capital, particularly around deep tech, defense technology, and space applications. The venture market had started moving past some of the AI hype and was looking for genuine hardware plays with defensible moats and real customers.

Northwood hit that sweet spot perfectly.

Northwood Space experienced significant growth with a

The Space Force Contract: Government Validation at Scale

Now let's talk about the other major announcement: the $49.8 million Space Force contract. In many ways, this is even more significant than the venture funding, though they're different types of validation.

The Space Force awarded Northwood a contract to help modernize the Satellite Control Network. This is a big deal for several reasons, and understanding them requires knowing something about how government defense procurement works.

First, getting a government contract at this scale is genuinely difficult. The process is slow, complex, and involves layers of evaluation. You can't just pitch an idea and close a deal like you might with a venture-backed customer. There are statutory requirements, procurement regulations, security clearances, and competing proposals. The fact that Northwood won this contract means they cleared all those hurdles.

Second, the SCN is mission-critical infrastructure for the U.S. Space Force. It's not just any satellite system. The SCN handles tracking and controlling GPS satellites, which are fundamental to military operations, precision timing, navigation, and countless other critical systems. It handles Earth observation satellites that provide intelligence. It handles communications satellites. This is some of the most important space infrastructure the U.S. operates.

Third, the Space Force has been aware of the SCN's capacity problems since at least 2011. That's not a criticism of the Space Force. It's a recognition of how difficult this problem is to solve. You can't just rip out forty-year-old infrastructure and replace it overnight. You need to maintain continuity of operations while modernizing. You need to ensure new systems integrate with legacy systems. You need to validate that new infrastructure is reliable enough for mission-critical operations.

The fact that the Space Force is now contracting with a commercial startup to modernize this infrastructure represents a significant shift in how the military approaches space. Rather than solely relying on traditional defense contractors, they're opening the door to innovative commercial companies. This is the kind of shift that creates entire new markets.

The contract size—$49.8 million—is substantial but not enormous in government contracting terms. For a startup in Northwood's position, it's validation that they can execute at scale. It's proof that their technology works and meets military standards. It's a foundation for much larger contracts down the road.

Importantly, this contract isn't unique. The Space Force has been steadily increasing its acquisition of commercial space services. This is part of a broader shift toward what's called "commercial space integration," where military space operations increasingly rely on commercial providers rather than solely on government-owned systems.

For Northwood, this contract does several things. It provides immediate revenue and profitability acceleration. It gives the company military credentials and operational validation. It demonstrates to other commercial customers that Northwood's technology meets the most rigorous standards (since if it can meet Space Force requirements, it can certainly meet commercial requirements). And it creates a reference customer that makes future sales easier.

The Technical Details: What Northwood Actually Built

Let's get into the specifics of what Northwood Space has actually engineered. This is where the company's differentiation becomes clear.

Northwood has deployed what they call "portal" sites—ground stations equipped with phased array antennas. Each current generation portal site can handle eight satellite links simultaneously. That means you can maintain continuous communication with eight different satellites at the same time. To put that in context, legacy dish antenna systems typically handle one or two satellite links per station. This is a substantial improvement in capacity per physical location.

But Northwood's roadmap is even more ambitious. Griffin Cleverly, the company's Chief Technology Officer, indicated that by the end of 2027, the next generation of Northwood's ground stations would be able to handle 10 to 12 simultaneous satellite links per station. Furthermore, Northwood's overall distributed network—with multiple portal sites in different locations—would be capable of maintaining communication with hundreds of satellites across the entire network.

This matters because it fundamentally changes the economics of satellite operations. If you can build modular ground station infrastructure that can be deployed in multiple locations and scaled as needed, you're no longer constrained by the scarcity of ground station access. You've solved a real bottleneck.

The technology stack behind this is complex. It includes:

- Phased array antenna design and manufacturing: Creating thousands of antenna elements and integrating them into a functional array

- Radio frequency and microwave engineering: Building the systems that generate, transmit, receive, and process signals at these frequencies

- Signal processing software: Algorithms that manage beam steering, signal filtering, and data extraction

- Network infrastructure: Connecting multiple portal sites and managing communication with satellite operators

- Control systems and automation: Software that manages which satellites are being tracked, when handoffs occur between stations, and how resources are allocated

- Security and encryption: Ensuring that sensitive military and commercial communications are protected

Each of these is a substantial engineering challenge on its own. Integrating them into a cohesive, reliable, production-grade system is where Northwood's value lies.

Market Dynamics: Why This Matters Now

Northwood Space's recent success isn't random. It's the result of specific market dynamics that have been developing over the past five to ten years.

The satellite industry is in the middle of a dramatic transformation. For most of the space age, satellites were scarce and expensive. You launched a few satellites at enormous cost, and they served for decades. The economics were simple: total number of satellites in orbit was measured in hundreds.

That's changed completely. We're now in an era of massive satellite constellations. SpaceX's Starlink has deployed thousands of satellites and plans to deploy many thousands more. Amazon's Project Kuiper is building a constellation of thousands of satellites. Multiple other companies are doing the same. The total number of active satellites in orbit is now measured in tens of thousands and growing.

This creates several downstream effects:

1. Increased data volume: More satellites means vastly more data flowing from space to Earth. All that data has to be received and processed somewhere. Ground station capacity becomes a genuine constraint.

2. More operators needing ground access: It's not just the constellation operators themselves. They have customers: internet service providers, governments, enterprises. Those customers need access to ground stations to send commands and receive data.

3. Geographic distribution becomes critical: With thousands of satellites in orbit, you can't afford to have a few centralized ground stations. You need distributed access. This is particularly true for low Earth orbit satellites, which have limited visibility windows from any given location.

4. Faster pace of innovation: The commercial space industry is moving much faster than legacy government space programs. Companies expect ground station infrastructure to be upgraded and improved constantly, not every forty years.

All of this creates ideal market conditions for a company like Northwood. They're not just selling technology to one specific customer. They're addressing a fundamental infrastructure gap that multiple market segments need to solve.

The customers Northwood is pursuing include:

- Satellite constellation operators who need to command and control their fleets

- Government agencies (like the Space Force) who operate their own satellite missions

- Commercial space companies who need to downlink data from satellites they operate

- Research institutions who use satellites for scientific missions

- International partners who need satellite communication capability

Each of these segments has slightly different requirements, but they all need the same fundamental capability: reliable, high-capacity ground station infrastructure. Northwood is building the infrastructure layer that serves all of them.

Estimated data: Northwood's $100 million Series B funding is primarily allocated to scaling operations (40%), followed by team expansion (25%), manufacturing capacity (20%), and market expansion (15%).

The Competitive Landscape: Why Northwood Has an Advantage

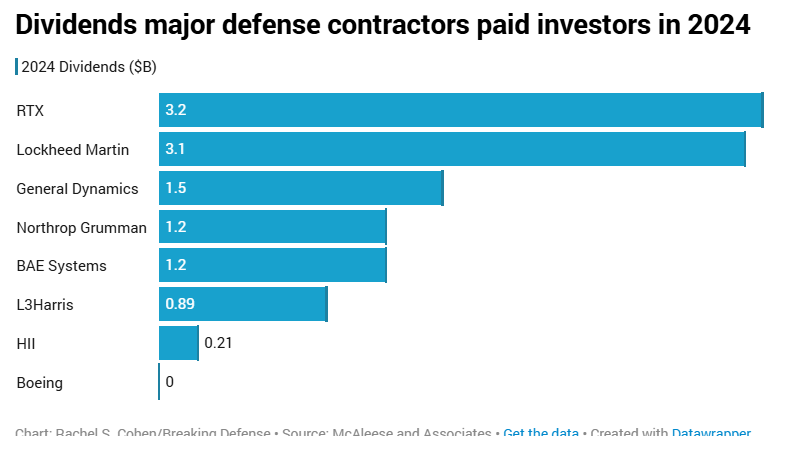

You might ask: why isn't anyone else doing this? Why doesn't a large defense contractor like Lockheed Martin or Raytheon offer this solution?

The answer is interesting and reveals something important about how large incumbents operate.

Traditional defense contractors built their satellite control infrastructure around legacy systems. They have billions of dollars invested in existing ground stations, expertise built around traditional antenna systems, and deeply embedded relationships with government customers based on the current infrastructure. They have incentives to maintain the status quo because that's where they make money.

Introducing a radically new approach means admitting that your existing infrastructure is becoming obsolete. It means investing in entirely new capabilities. It means potentially cannibalizing your existing business. Most large companies find these incentives too strong to overcome. They'd rather optimize within the existing paradigm than disrupt their own cash flows.

Smaller startups don't have these legacy constraints. Northwood doesn't have billions invested in old ground stations. They don't have a customer base that demands compatibility with forty-year-old systems. They can build optimized from scratch around modern technology and modern needs.

This is a classic innovator's dilemma situation. The incumbents are stuck defending the old paradigm, while the startup can innovate freely. Eventually, if the startup's solution is good enough (and more cost-effective), it becomes the new standard, and the incumbent's old infrastructure becomes a liability rather than an asset.

Northwood is in that position. They're not trying to replace legacy infrastructure for legacy's sake. They're building for the future satellite industry, and the future is going to look very different from the past.

Manufacturing and Scale: From Prototype to Production

One of the most underrated aspects of deep tech companies is manufacturing and scaling. Northwood needs to do more than just design phased array antennas and control systems. They need to manufacture these systems at scale, reliably, with consistent quality.

This is where the capital infusion becomes crucial. Building manufacturing capacity isn't cheap. You need facility space, equipment, test infrastructure, and trained personnel. You need supply chain relationships with component suppliers. You need quality control processes.

Bridgit Mendler was explicit that Northwood felt ready for this challenge. "We're ready for from a production standpoint," she said. This means the company has likely already been running small-scale production, learning what bottlenecks exist, and building the expertise needed to scale.

The $100 million Series B is partly about accelerating this scaling. Northwood needs to build multiple portal sites simultaneously. Each site requires engineering, installation, testing, and validation. Each site also becomes a training ground for the next generation of equipment.

Additionally, the company needs to develop next-generation products. CTO Griffin Cleverly talked about moving from the current generation (8 simultaneous satellite links per station) to the next generation (10-12 links per station). That's not a trivial upgrade. It requires redesign of antenna arrays, new signal processing algorithms, potentially new electronics and cooling systems. It's a full engineering cycle that needs to happen while the current generation is being deployed.

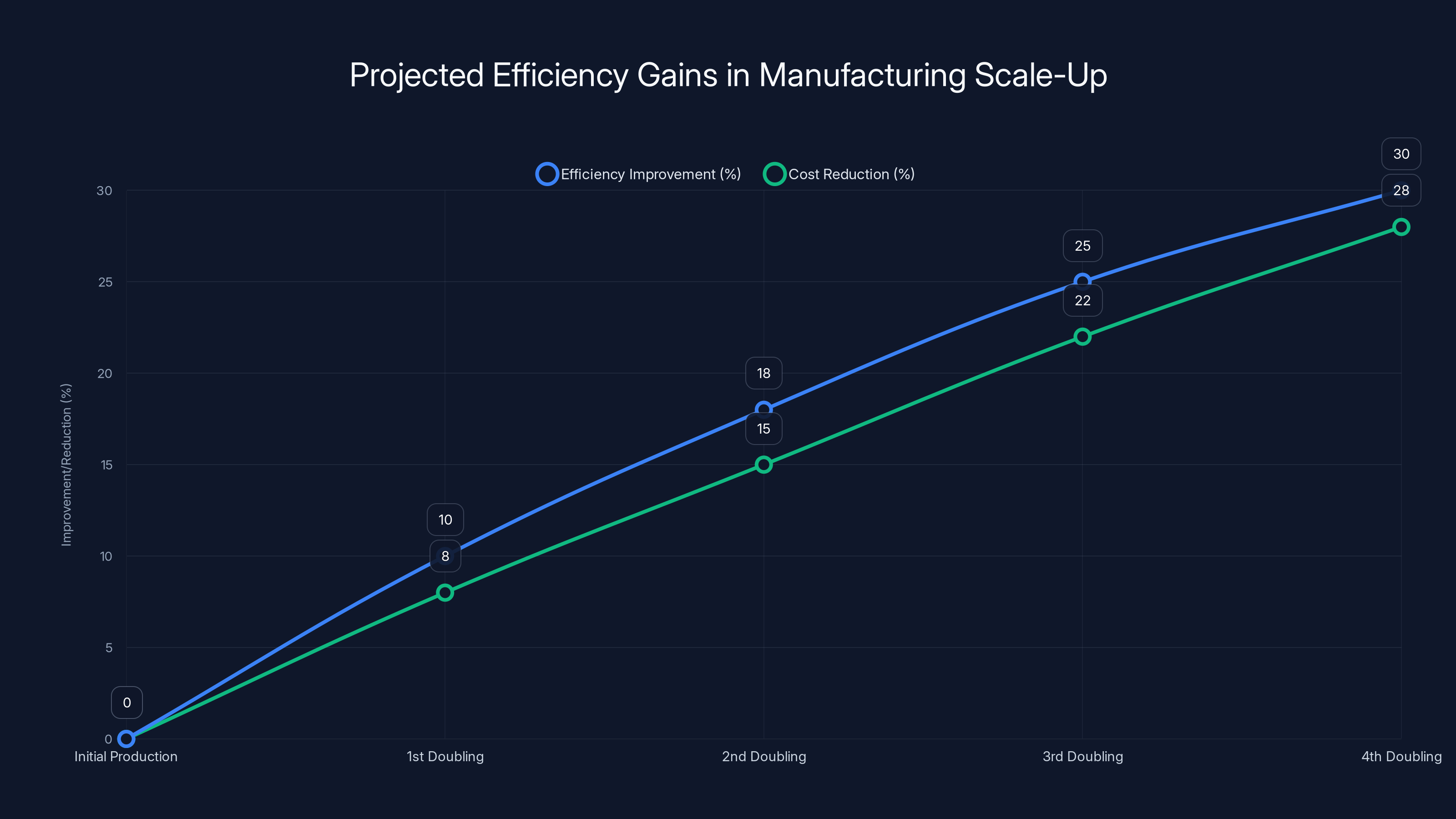

Manufacturing at scale also creates what economists call "learning by doing" benefits. As you manufacture more units, your process becomes more efficient. Your yield improves. Your costs decrease. Your team develops expertise. These improvements are typically captured as a predictable percentage improvement per doubling of cumulative production, known as the learning curve.

For Northwood, each portal site they build creates learning that makes the next one cheaper and faster. By the time they've built, say, twenty sites, their manufacturing process will be dramatically more efficient than it was for the first one. The capital deployed now will compound into efficiency improvements down the line.

The Space Force Contract: What It Really Means

Let's circle back to the Space Force contract with more detail about what the contract actually entails and why it matters strategically.

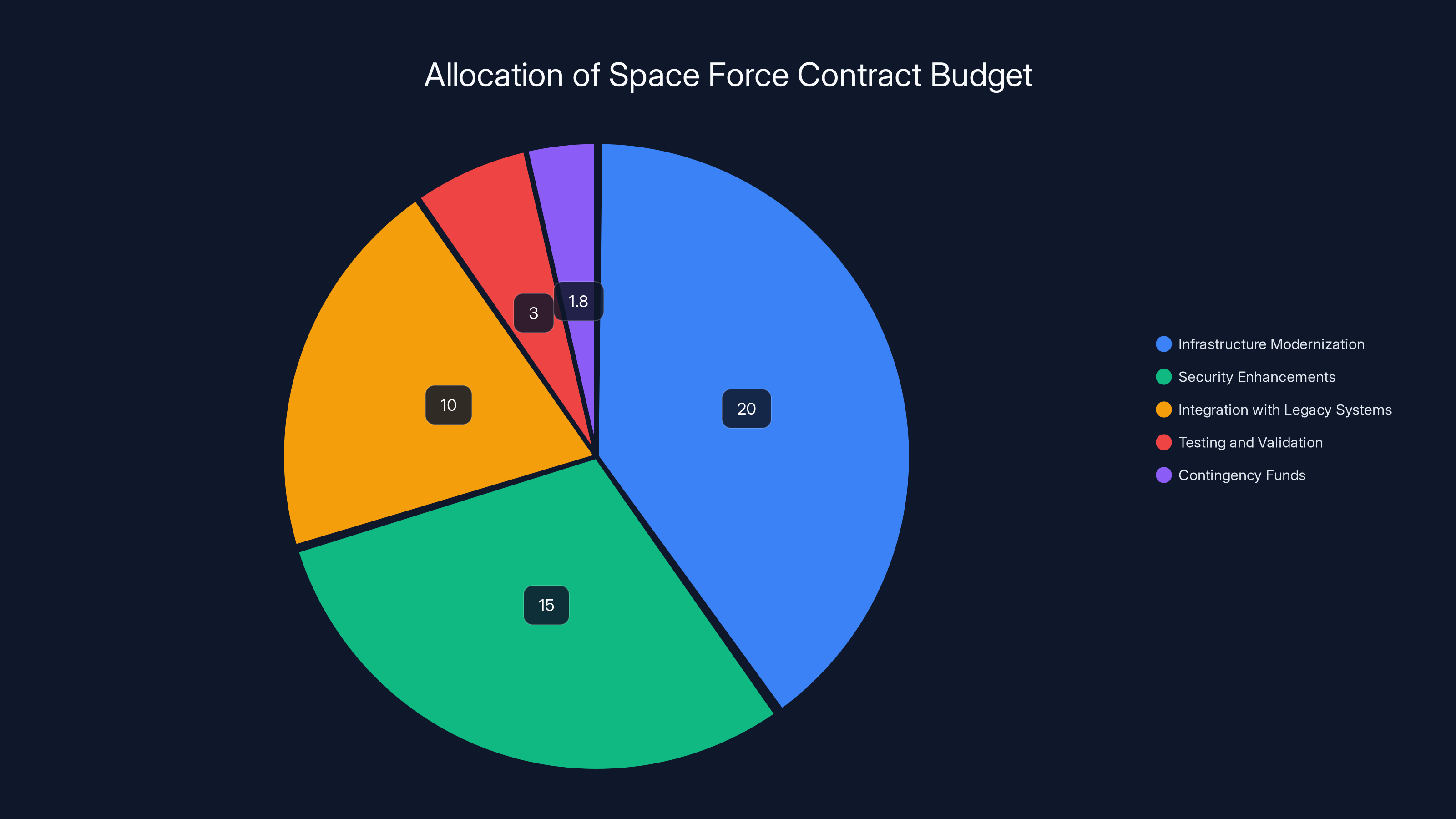

The contract was to help upgrade the Satellite Control Network. This could mean several things, and without access to the contract details, we can make educated guesses based on what we know about the SCN and what Northwood does.

Likely, Northwood is being contracted to:

- Deploy new ground stations at strategic locations to increase the overall capacity of the SCN

- Integrate with existing infrastructure to ensure new phased array systems work alongside legacy dish antenna systems

- Provide operational support to help the Space Force understand how to use the new infrastructure

- Develop software and control systems that tie new and old infrastructure together

- Perform testing and validation to ensure the new systems meet military requirements

Each of these elements requires engineering work, and that's where the $49.8 million is going.

But here's what's equally important: this contract is likely the first of many. Once Northwood has successfully modernized a portion of the SCN, the Space Force will likely expand the program. Successful government contracts often lead to additional funding, expanded scope, and longer-term relationships.

Moreover, success with the Space Force creates a reference customer for other government agencies. The National Reconnaissance Office, the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, and other federal agencies all operate satellites. If Northwood proves it can meet Space Force standards, they become credible vendors for these other organizations.

The timing of announcing both the Series B and the Space Force contract together is also strategic. Northwood is signaling to the market that they have both venture backing and government validation. This is the combination that makes a defense tech startup credible to institutional investors, commercial customers, and potential partners.

Phased array antennas offer higher capacity and faster switching speeds compared to traditional dish antennas, while requiring less space. Estimated data.

Implications for the Satellite Industry

So what does Northwood's success mean for the broader satellite industry? The implications are substantial.

First, ground station infrastructure is becoming a competitive advantage. For years, the assumption was that satellite operators would handle ground stations as a secondary concern. The real value was in the satellites themselves. Northwood's success suggests that's changing. Having access to reliable, high-capacity ground infrastructure is becoming a primary competitive factor. This will drive investment in ground systems across the industry.

Second, modular, distributed ground infrastructure is the future. The era of massive, centralized ground stations is ending. The future is modular systems that can be deployed in multiple locations and scaled independently. This changes the real estate, capital, and operational requirements for everyone in the industry.

Third, commercial companies are reshaping government space infrastructure. The Space Force contracting with a venture-backed startup to help modernize critical military infrastructure represents a significant shift. It suggests the military is willing to move faster and adopt newer approaches if they solve real problems. This opens doors for other innovative companies.

Fourth, the defensibility of space tech startups improves with scale. Northwood is building an increasingly difficult-to-replicate advantage. As they deploy more portal sites, integrate with more customers, and accumulate operational experience, their moat deepens. A competitor starting from scratch today would have a much harder time catching up than they would have two years ago.

Fifth, there's validation for the broader deep tech thesis. Northwood's success shows that there's real venture capital and real government commitment to funding ambitious hardware startups solving genuine technical problems. This encourages other founders to start companies in similar spaces.

The Capital Deployment Challenge: Making $100 Million Count

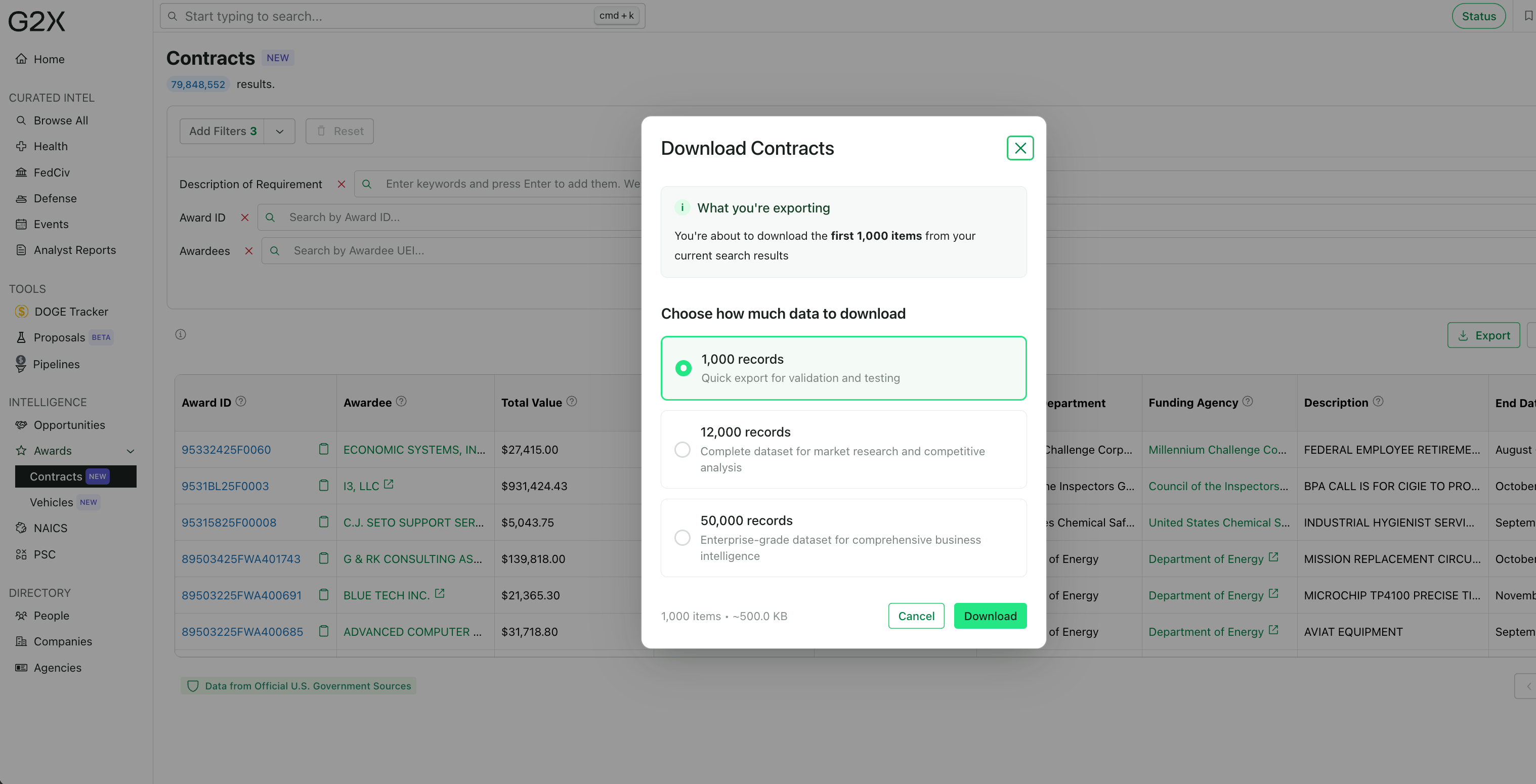

Having $100 million in capital is great. Deploying it effectively is where many startups struggle. It's worth thinking through what Northwood likely needs to spend this capital on and whether the amount makes sense.

Engineering and R&D: Building next-generation systems, improving manufacturing processes, and developing new features. Estimated: $15-25 million. Northwood needs to continuously improve the product or competitors will catch up.

Manufacturing capacity and equipment: Building out facilities to scale production. This includes lease or purchase of space, installation of manufacturing equipment, and test infrastructure. Estimated: $20-35 million. This is capital-intensive but necessary to serve customers.

Sales, marketing, and business development: Bringing on senior business development people, establishing sales channels, and building partnerships. Estimated: $10-15 million. You can have the best product in the world, but people need to know about it.

Operations and talent acquisition: Recruiting engineers, operations staff, and management. Salaries and benefits for a growing team. Estimated: $30-50 million over two years. A startup typically needs to roughly double its team to effectively deploy a Series B.

Integration and deployment work: Actually building and deploying ground stations for customers. This is partly customer revenue, but some development work might be partly funded by capital. Estimated: $10-20 million.

Working capital and contingency: Inventory, accounts receivable, unexpected costs. Estimated: $10-15 million.

Adding this up, the $100 million budget makes sense. It's not excessive for what Northwood needs to do, and it's not inadequate either. It's the right order of magnitude to fund roughly 18-24 months of aggressive growth, during which time the company should be generating meaningful revenue from customer deployments and the Space Force contract.

This is actually a really important point. One of the reasons Northwood was able to raise at this valuation and this amount is that the capital is clearly deployable. The company isn't raising money speculatively. It's raising money to do specific things that customers and government agencies have already validated they need.

What Could Go Wrong: Risks and Challenges

Northwood's success isn't guaranteed, and it's worth thinking through what could go wrong. Even well-capitalized companies with strong customers face genuine risks.

First, execution risk. Northwood needs to actually build, deploy, and operate these ground stations reliably. If they have manufacturing problems, or if deployed systems don't perform as promised, they lose credibility. This is deep tech, where small engineering problems can cascade into big failures.

Second, competitive risk. Even though entry barriers are high, they're not insurmountable. Well-funded competitors could emerge. Traditional defense contractors could decide to modernize their offerings more aggressively. A well-financed startup could be founded with experienced talent from Northwood or similar companies.

Third, technology risk. The phased array antenna approach Northwood is betting on is proven technology, but applying it to this specific problem at this scale is relatively new. There could be unexpected challenges that emerge as they scale. For example, environmental factors (weather, temperature) might affect performance in ways not fully anticipated in testing.

Fourth, customer concentration risk. Right now, Northwood has a limited customer base. Much of their near-term revenue is likely from the Space Force contract and a handful of commercial customers. If one of these customers significantly reduces their demand, or if there's a contract dispute, it could create near-term challenges. This risk will decrease as they add more customers, but it's real right now.

Fifth, government and regulatory risk. The Space Force contract could be modified, reduced, or cancelled by future administrations or budget decisions. International regulations around satellite communications could change. These are outside Northwood's control but could significantly impact their business.

Sixth, supply chain risk. Like all hardware companies, Northwood depends on suppliers for components. If key suppliers face disruptions or increase prices significantly, it could impact margins or delivery timelines.

Seventh, talent retention risk. In a hot market, competitors will actively recruit Northwood's experienced engineers. Retaining the technical talent that makes the company work is critical and ongoing.

None of these risks are existential if managed well, but they're all real. Successful execution over the next 18-24 months will significantly de-risk Northwood and strengthen their position. Poor execution could create openings for competitors.

Estimated data shows that as Northwood scales production, efficiency could improve by up to 30% and costs could reduce by 28% over several production doublings.

The Broader Space Tech Ecosystem Context

Northwood Space's success has to be understood within the broader context of the space tech ecosystem. There's been a massive influx of capital and attention to space-related companies over the past five to ten years.

SpaceX revolutionized orbital launch costs and proved that a private company could achieve what previously only governments could do. That success inspired an entire generation of founders to start companies solving different parts of the space problem. Blue Origin, Axiom Space, Relativity Space, and dozens of other companies emerged to tackle everything from satellite manufacturing to space tourism to in-space manufacturing.

Many of these companies benefited from what we might call the "space tech halo effect." Because SpaceX succeeded and made space seem like a promising domain for entrepreneurship, venture capitalists became more willing to fund other space companies. Government agencies became more willing to work with commercial partners. This created a favorable environment for startups.

But this also meant a lot of capital was deployed to space companies that didn't necessarily have the validation that Northwood has. Many of those companies have since faced challenges, restructuring, or failure. The venture market has become somewhat more disciplined about space tech investments, focusing on companies with real customers and path to profitability.

Northwood is well-positioned within this environment. Unlike some space startups that are betting on a hoped-for future market, Northwood is addressing problems that customers have today. They have revenue. They have contracts. They have paying customers. This is increasingly the type of space company that can raise venture capital at premium valuations.

Leadership and the Team Factor

Bridgit Mendler, Northwood's founder and CEO, deserves some attention because leadership matters enormously in deep tech companies. Success is never just about the technology. It's about having someone who can navigate the incredibly complex requirements of deep tech entrepreneurship.

Mendler has positioned herself and her company as the answer to a long-standing government problem. She's been able to articulate the technical challenge in ways that resonate with venture capitalists, government procurement officials, and commercial customers. That's not easy to do. It requires both deep technical credibility and business acumen.

Similarly, Griffin Cleverly, the CTO, represents the kind of technical depth that's required to actually execute on phased array antenna systems. You don't just hire someone to fill the CTO role and execute on something this complex. You need someone with deep expertise in the specific domain.

The broader team at Northwood presumably includes signal processing experts, RF engineers, software architects, operations people, and others with deep space and communications experience. Building this team is probably one of Northwood's biggest accomplishments to date.

As they scale, they'll need to continue building this team without diluting the culture or losing sight of the technical vision. This is often where growth-stage companies stumble. They bring in people who are experts in scaling, but those people don't have the deep domain expertise that created the company in the first place. Managing that balance is crucial.

Investment Implications and Valuation Questions

Although Northwood hasn't disclosed its valuation, we can make some educated guesses based on the funding details and market context.

A

Is this valuation justified? That depends on several factors:

Revenue and path to profitability: If Northwood is already generating meaningful revenue and the Space Force contract represents

Market size: The total addressable market for ground station infrastructure is substantial. The satellite industry is growing rapidly, and every satellite operator needs ground station access. If Northwood can capture even a modest share of this market, the market opportunity is multi-billion dollars.

Competitive position and defensibility: As we discussed, Northwood has built significant defensibility through technology, customer relationships, and operational experience. The company is not easy to compete with, which justifies a valuation premium.

Exit potential: If Northwood executes well, what's the exit potential? Likely acquisitions could be larger defense contractors wanting to modernize their satellite infrastructure. Or the company could eventually go public if it reaches substantial size and profitability. Either way, the exit potential seems genuine.

Based on these factors, the valuation seems reasonable but not excessively high. Northwood will need to execute on multiple fronts over the next two to three years, but the company has the capital and the customers to do so.

Estimated budget allocation for the Space Force contract highlights the focus on infrastructure modernization and security enhancements. Estimated data.

Future Roadmap: What's Next for Northwood

Based on what we know about Northwood's current position, we can speculate on their likely roadmap over the next few years.

2026-2027 (Next 12-18 months):

- Deploy multiple new portal sites for Space Force SCN modernization

- Begin expanding commercial customer base beyond initial customers

- Bring next-generation phased array systems to initial production

- Expand manufacturing capacity and team

- Likely start thinking about strategic partnerships with established space companies

2027-2028 (18-36 months out):

- Transition to next-generation systems with improved capacity

- Achieve profitability or near-profitability

- Expand to international markets (with appropriate government approvals)

- Begin planning Series C or alternative capital raises

- Potentially expand into adjacent markets (like space-to-ground communications infrastructure)

2028-2030 (3-5 years out):

- Establish Northwood as the dominant player in modern phased array ground stations

- Pursue strategic partnerships or acquisition discussions with larger players

- Continue expanding served customers and markets

- Potentially consider IPO path if company has reached substantial profitability and market presence

This is speculative, but it's grounded in what works for successful hardware startups that have achieved product-market fit and real customers.

The Bigger Picture: Space as Infrastructure

Why does Northwood's success matter beyond just the company itself? Because it represents a fundamental shift in how we think about space.

For decades, space was exotic. It was a domain for governments and a handful of well-capitalized companies. Most people thought of space as something distant and irrelevant to their daily lives.

That's changed. Space is becoming infrastructure, like transportation or communications networks. Satellites provide internet connectivity. They provide weather data. They provide navigation and timing. They provide Earth observation. They provide everything from financial market data to climate monitoring.

As space becomes infrastructure, it attracts the kinds of companies and capital that build and operate infrastructure. Hardware companies. Operations specialists. Integration firms. Security companies. It's becoming professionalized and capital-intensive in a different way than it was before.

Northwood is part of this trend. The company isn't building the most exciting part of the space industry (that would be the rockets or the satellites). But they're building the decidedly unglamorous but utterly essential plumbing that makes everything else work. That's the sign of a maturing industry.

When an industry matures and consolidates around infrastructure, the companies that win are often not the ones that are loudest about their innovation. They're the ones that are most reliable, most integrated, most trusted. Northwood is positioning itself to be that kind of company.

Lessons for Founders and Investors

Northwood Space's journey offers several lessons for founders and investors thinking about deep tech companies:

1. Solve a real problem that people are willing to pay for. Northwood isn't building something speculative. They're solving a problem that the U.S. military has been struggling with for fifteen years. Customers need this. That's powerful validation.

2. Build a moat that's hard to replicate. Phased array antenna systems for satellite control aren't trivial to engineer. The expertise required, the testing needed, the manufacturing complexity—these create defensibility. As you scale, that moat deepens.

3. Don't be afraid to be unglamorous. Northwood isn't building cool rockets or flashy satellite services. They're building ground infrastructure. That's not exciting, but it's valuable. Don't get seduced by the need to be exciting. Solve real problems.

4. Government is a real customer. Founders often assume venture capital is the only way to validate a business. Government contracts can be just as valuable, especially if they represent real purchasing power and real problems.

5. Capital deployment matters as much as capital amount. It's not just about raising money. It's about having a clear plan for how to deploy that capital effectively. Northwood's Series B seems thoughtfully deployed rather than sprayed across random initiatives.

6. Integration is often where the differentiation lives. Most of Northwood's advantage isn't in any single technology. It's in integrating multiple technologies into a coherent ground station system. Don't underestimate the value of good systems thinking.

The Space Force's Strategic Thinking

It's also worth thinking about why the Space Force made this move. Contracting with a venture-backed startup is a deliberate strategic choice, and it signals something about how the military is thinking about its future.

The Department of Defense has been moving toward what's called "agile acquisition" and greater reliance on commercial solutions. The Satellite Control Network modernization represents exactly this kind of thinking. Instead of following a traditional defense contractor path (which might take a decade and cost vastly more), the Space Force is working with a commercial startup that can move faster and innovate more quickly.

This suggests the military is comfortable with a certain amount of risk in exchange for faster innovation and lower costs. It also suggests they trust that venture-backed companies can meet the highest standards for reliability and security (which, to be clear, they can—military requirements are rigorous, and companies that meet them have demonstrated serious competence).

For future founders and investors, this signals that the military is willing to fund innovative approaches to solving real problems. If you're building something that solves a genuine defense need, the Space Force and other military branches are potential customers, not just venture capital.

Closing Thoughts: Why This Moment Matters

Northwood Space's

The company has demonstrated something crucial: you can build a venture-backed company solving a genuinely hard technical problem, acquire real customers with real money, and attract world-class capital and partners. You don't need to be a glamorous consumer app. You don't need to be a hype-driven AI company. You need to solve real problems that people need solved.

Bridgit Mendler and the team at Northwood have done exactly that. They've built technology that works, found customers who need it, executed well enough that those customers are happy, and attracted the attention of venture capital and government alike.

Over the next few years, Northwood's execution will determine whether this momentum continues. But the foundation they've built—the technology, the customers, the capital, the team—gives them a strong position to succeed.

For the space industry, the implications are clear: ground infrastructure matters, and modernizing that infrastructure is a viable business. For the venture capital world, it's a reminder that patient capital invested in hard problems can generate outsized returns. For the government, it's validation that working with commercial partners can accelerate innovation and modernization.

Northwood's success is a win for everyone in the space industry, not just Northwood itself.

FAQ

What is Northwood Space?

Northwood Space is a California-based startup that develops phased array antenna technology for satellite ground stations. The company provides modernized, modular ground-based communications infrastructure that allows operators to maintain simultaneous links with multiple satellites. Founded just a few years ago, Northwood is positioning itself as the next-generation alternative to traditional large dish antenna systems that have dominated satellite control infrastructure for decades.

How does phased array antenna technology work for satellite communications?

Phased array antennas use thousands of small antenna elements arranged in a grid, with electronic systems that control the phase of signals sent to each element. This allows the antenna beam to be electronically steered without any mechanical movement, enabling rapid switching between satellites and instantaneous directional changes. Unlike traditional dish antennas that must physically rotate to track satellites, phased arrays can maintain communication with multiple satellites simultaneously by electronically directing different beams to different targets.

Why did Northwood Space receive a Space Force contract?

The U.S. Space Force awarded Northwood a $49.8 million contract to help modernize the Satellite Control Network, which has faced capacity constraints since at least 2011. Northwood's phased array technology offers significantly greater capacity than legacy dish antenna systems while requiring less physical space. The contract represents the Space Force's recognition that Northwood's solution solves a genuine operational problem that has persisted in government infrastructure for over a decade.

What is the Satellite Control Network and why does it matter?

The Satellite Control Network is the U.S. military's ground-based infrastructure for commanding, controlling, and communicating with satellites in orbit. It's used to track and manage GPS satellites, Earth observation systems, communications satellites, and other critical space assets. The SCN has capacity limitations that constrain the number of satellites it can manage simultaneously, creating bottlenecks for military space operations. Modernizing the SCN is essential as the number of satellites in orbit increases dramatically.

How much funding did Northwood Space raise and who are the investors?

Northwood Space closed a

What is a phased array antenna and how is it different from traditional satellite antennas?

A phased array antenna consists of many small radiating elements whose combined signals are controlled by computers to create specific radiation patterns. Traditional satellite antennas (dish antennas) must mechanically rotate to point toward satellites, are much larger physically, handle fewer simultaneous connections, and are more expensive and difficult to upgrade. Phased arrays offer smaller physical footprints, electronic steering (no moving parts), ability to handle multiple simultaneous satellite links, and modular scalability.

What does "portal site" mean in the context of Northwood Space?

Portal sites are Northwood's ground stations equipped with phased array antenna systems. Current generation portal sites can maintain simultaneous communication with eight different satellites. Northwood's next generation (planned for 2027) is expected to handle 10-12 simultaneous links per site. When distributed across multiple portal sites in different geographic locations, Northwood's network will be capable of communicating with hundreds of satellites simultaneously.

Why did Northwood need this much capital and what will they spend it on?

Northwood needed capital to scale manufacturing of ground stations, expand deployment across multiple geographic locations, accelerate R&D on next-generation systems, build sales and business development teams, and expand operations. The company is experiencing rapid customer demand and needed capital to avoid resource constraints. The $100 million is allocated to roughly 18-24 months of aggressive growth, after which the company expects to generate sufficient revenue to sustain growth with limited additional capital needs.

How many satellites can Northwood's ground network handle compared to traditional systems?

Traditional dish antenna ground stations typically handle one to two satellite links per site. Current Northwood portal sites handle eight simultaneous links per site, representing a 4-8x improvement in capacity per location. By 2027, next-generation Northwood sites are expected to handle 10-12 links per site. When multiple portal sites are networked together, the cumulative capacity extends to maintaining communication with hundreds of satellites across the entire network.

What other companies compete with Northwood Space in ground station infrastructure?

Traditional defense contractors like Lockheed Martin and Raytheon have legacy satellite control systems, but they're built on older technologies and business models. Newer competitors could emerge, but the high barriers to entry (significant capital, specialized expertise, manufacturing complexity, regulatory hurdles) make competition challenging. Northwood's current lack of direct, venture-backed competitors is notable and reflects how difficult this space is to enter.

What does Northwood Space's success mean for the satellite industry?

Northwood's success signals that ground infrastructure modernization is a viable business opportunity and that venture capital and government agencies view advanced ground stations as critical infrastructure. This validation is likely to attract more investment to space infrastructure companies and encourage established players to modernize their offerings. It also demonstrates that commercial startup approaches can outcompete legacy government and defense contractor solutions for solving real infrastructure problems.

Key Takeaways

- Northwood Space raised 49.8 million Space Force contract for satellite control network modernization

- The company's phased array antenna technology offers 4-8x capacity improvement over traditional dish antenna systems, handling 8 simultaneous satellite links per current-generation portal site

- U.S. Space Force has recognized decade-long capacity constraints in the Satellite Control Network since 2011, validating Northwood's solution as mission-critical infrastructure

- Northwood represents a new paradigm where venture-backed startups are modernizing legacy government infrastructure faster and more cost-effectively than traditional defense contractors

- The company has achieved genuine product-market fit with real customers and government validation, deploying capital purposefully to scale manufacturing and expand customer base

Related Articles

- AI Chip Startups Hit $4B Valuations: Inside the Hardware Revolution [2025]

- Palantir's ICE Contract: The Ethics of AI in Immigration Enforcement [2025]

- When VCs Clash: Inside the Khosla Ventures ICE Controversy [2025]

- Obvious Ventures Fund Five: The $360M Bet on Planetary Impact [2026]

- TechCrunch Disrupt 2026: Your Complete Guide to Early Bird Deals & Networking [2025]

- Tech Workers Demand CEO Action on ICE: Corporate Accountability in Crisis [2025]

![Northwood Space Lands $100M Series B and $50M Space Force Contract [2026]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/northwood-space-lands-100m-series-b-and-50m-space-force-cont/image-1-1769512053910.jpg)