Nvidia and Meta's AI Chip Deal: What It Means for the Future

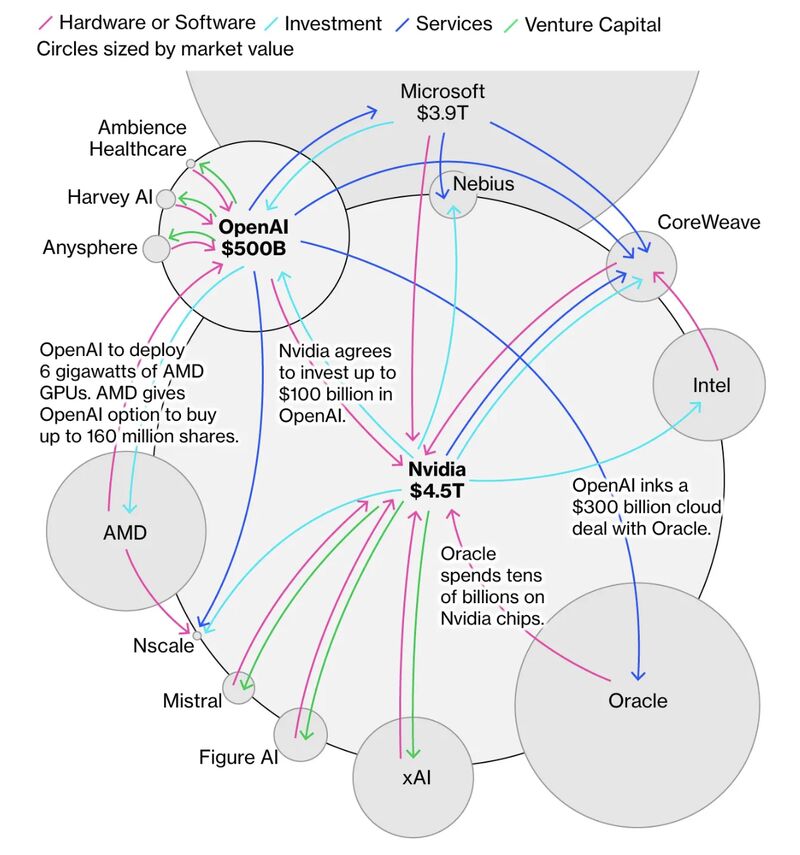

When you think about Nvidia, you probably picture graphics processing units. That's what made the company famous, and that's what turned it into a $3 trillion behemoth during the AI boom. But something fundamental is shifting in how tech giants build and power their infrastructure, and Nvidia's recent moves reveal what's actually happening underneath all the hype.

Nvidia's deal with Meta isn't just about buying more GPUs. It signals something far more important: the era of one-size-fits-all compute is over. Tech companies are no longer just chasing raw power. They're building intricate, customized computing ecosystems that blend GPUs, CPUs, and custom chips optimized for specific workloads. And Nvidia, recognizing this, is racing to become the company that sells everything, not just the GPUs everyone's obsessed with.

What makes this moment different? Two years ago, companies needed Nvidia GPUs for training. Today, they need a complete stack: chips for inference, chips for serving requests, chips that talk to each other seamlessly, and the software glue holding it all together. Meta's decision to make a "large-scale deployment" of Nvidia's Grace CPUs as a standalone product signals that the compute landscape has fundamentally changed.

This isn't just corporate news. It reshapes what matters in AI infrastructure, what companies will spend billions on, and ultimately, which vendors win the next decade of computing. Let's break down what's actually happening, why it matters, and what it means for the future of AI.

TL; DR

- Meta's multibillion-dollar deal with Nvidia includes CPUs, not just GPUs, signaling a shift toward diversified compute stacks for AI workloads

- Agentic AI demands efficient CPUs that can handle general-purpose tasks without bottlenecking GPU processing

- Tech giants are now building custom chips or diversifying suppliers, reducing Nvidia's lock-in on high-end compute

- Inference computing is now as important as training, requiring different hardware optimization strategies

- The "soup-to-nuts" approach wins: Companies that can sell integrated chip ecosystems, networking, and software will dominate the next phase

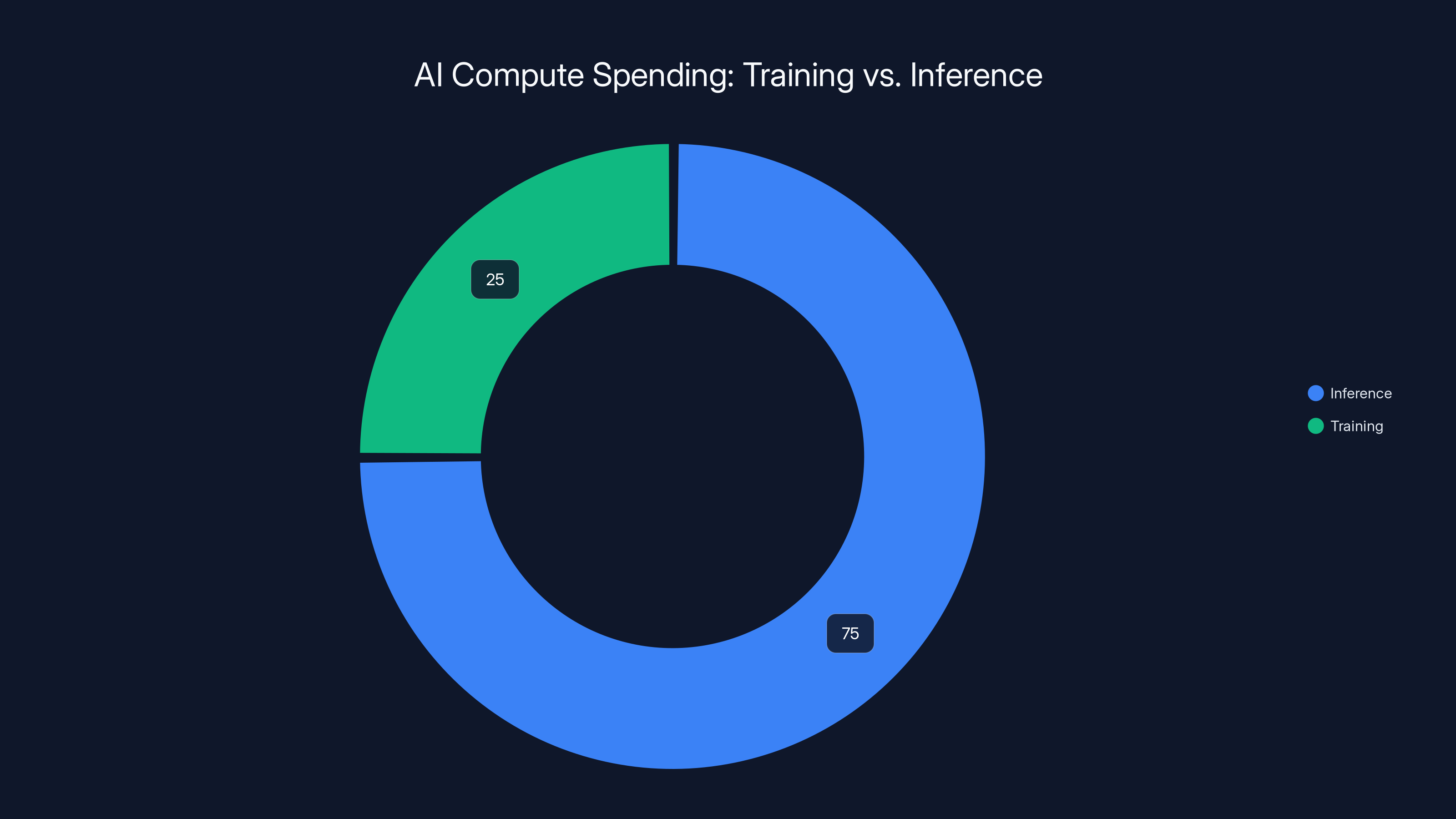

Estimated data shows a significant shift towards inference, now accounting for approximately 75% of AI compute spending, highlighting its growing importance over training.

The Traditional GPU Business Model Is Dying

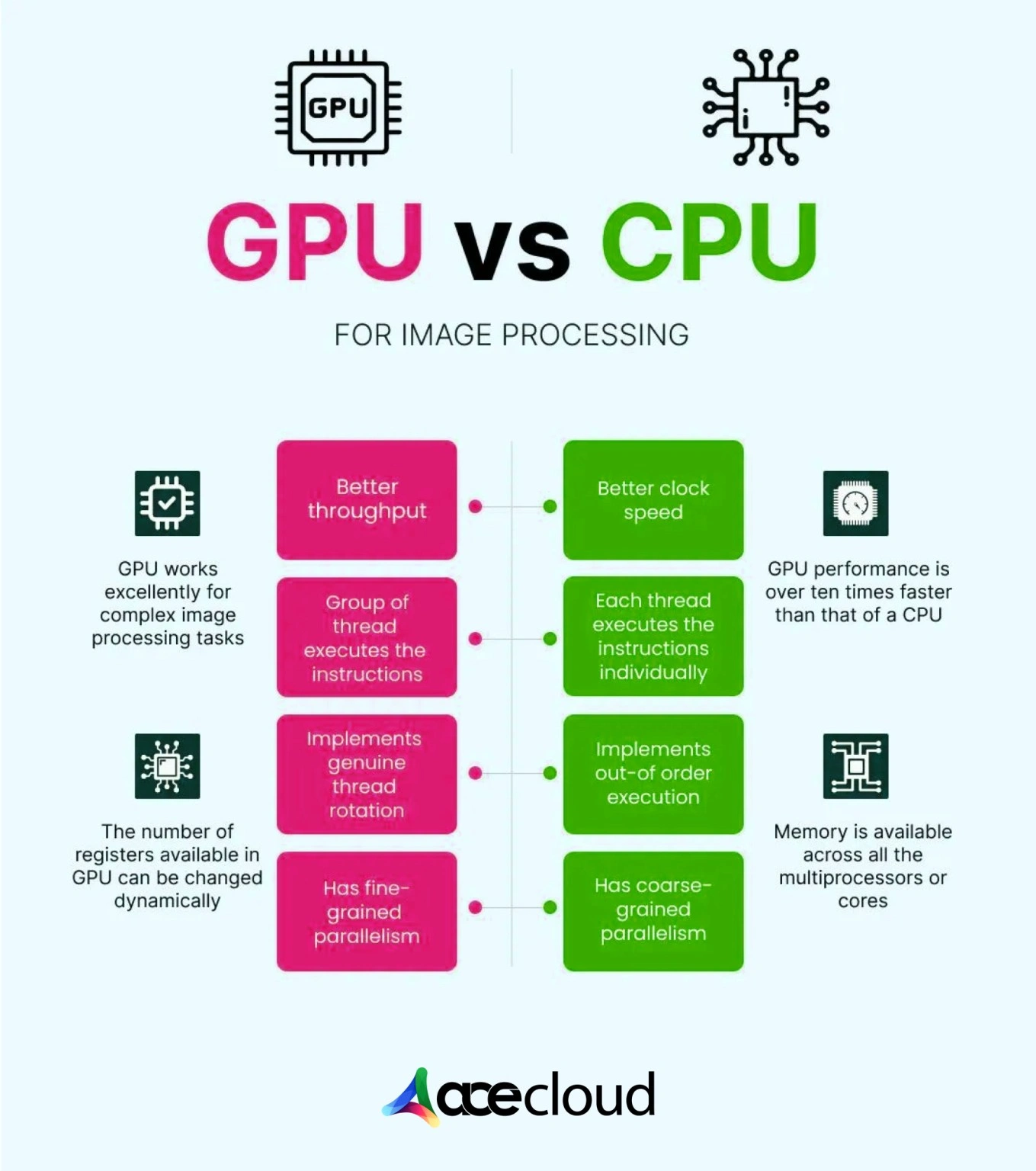

Let's be honest: Nvidia's GPU dominance was almost accidental. The company didn't originally design GPUs for machine learning. GPUs existed for gaming, rendering, graphics processing. Then machine learning researchers realized that the massively parallel architecture that made GPUs great at rendering pixels was equally great at performing matrix multiplications. And that's what neural networks do at scale.

For about two decades, that worked beautifully for Nvidia. Gaming pushed innovation. ML researchers and datacenters piggybacks on those innovations. Nvidia's data center business exploded.

But you can't run an entire AI infrastructure on just GPUs anymore. Here's why: modern AI systems don't just train models. They run them. They serve them to users. They handle requests, manage memory, route traffic, cache results. All that stuff happens on CPUs in traditional cloud infrastructure. It still needs to happen in AI datacenters.

The problem is acute: if your CPU is a bottleneck, it delays the GPU from getting its next batch of work. If your CPU takes 50 milliseconds to prepare inference requests, and your GPU can process them in 5 milliseconds, you've wasted GPU cycles. That's expensive. At scale, across millions of requests, that's billions of dollars in wasted hardware.

But here's the catch: CPUs are becoming critical for a different reason now. Agentic AI requires something GPUs weren't optimized for. When an AI system needs to make decisions, take actions, reason through multi-step problems, that work often runs on general-purpose CPUs, not specialized AI accelerators.

Nvidia spent decades making the best GPUs on earth. But it didn't make many CPUs. That was Intel and AMD's playground. Suddenly, Nvidia needed to play in that sandbox too, or risk losing access to compute spending at exactly the moment when spending became unimaginably large.

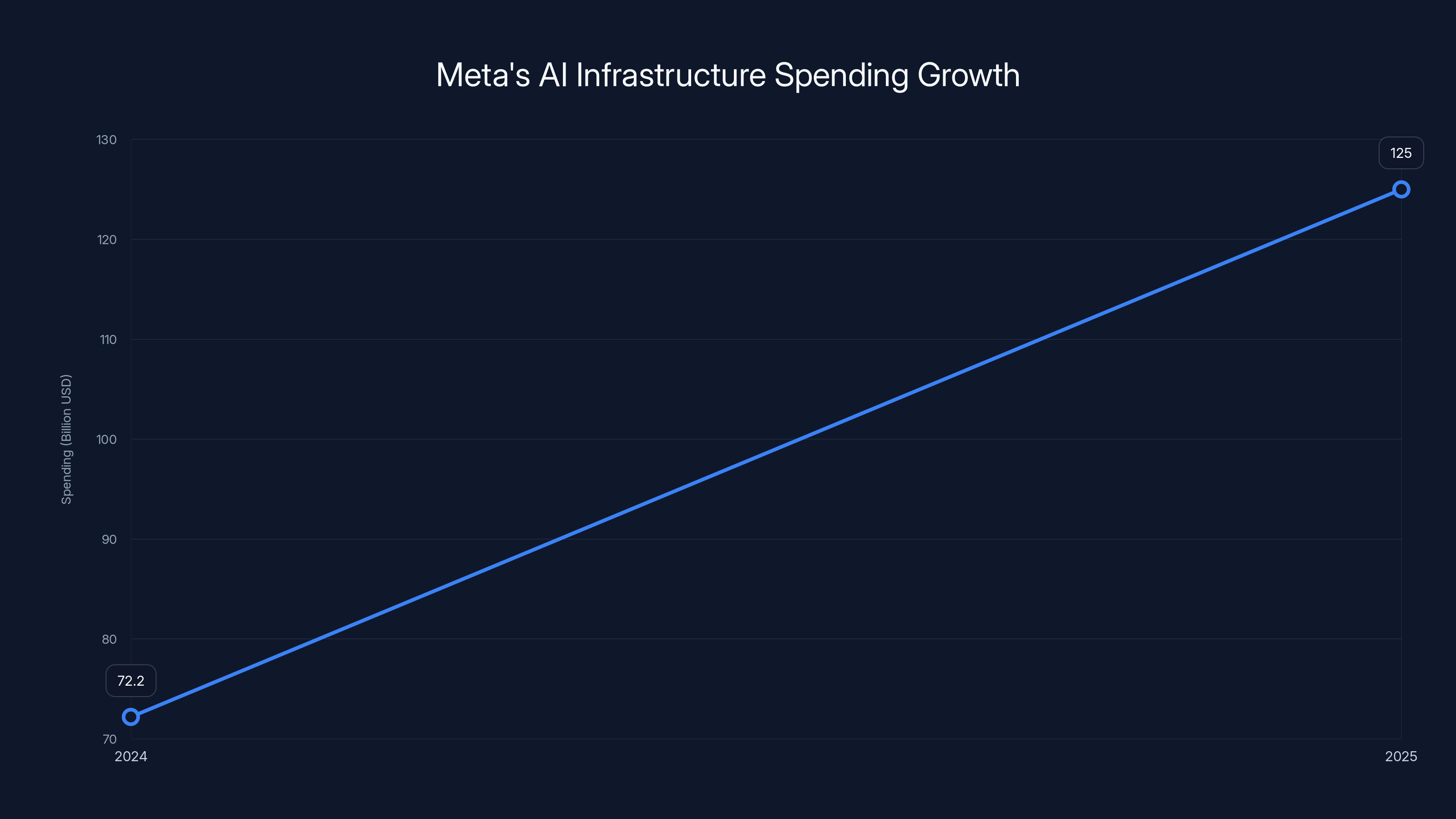

Meta's AI infrastructure spending is projected to nearly double from

The "Soup-to-Nuts" Strategy: From Chips to Software

Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang didn't get rich by making great hardware in isolation. He got rich by understanding that computing is a system. GPUs are useless without drivers. Drivers are useless without libraries. Libraries are useless without frameworks. The whole stack matters.

That's why Nvidia's recent moves go far beyond just selling more chips. The company is building what analysts call a "soup-to-nuts" approach to AI compute. It means: we'll sell you the GPUs, the CPUs, the interconnect technology that links them, the software that manages everything, and the ecosystem that makes it all work together.

Meta's deal exemplifies this. The announcement specifically mentioned that Meta would deploy "millions of Nvidia Blackwell and Rubin GPUs" alongside "large-scale deployments" of Nvidia's Grace CPUs. Not just one or the other. The entire stack.

Why? Because integrated systems work better. When you design a datacentre architecture around one vendor's philosophy, the pieces fit. The CPU and GPU communicate efficiently. The network adapters know how to handle the traffic patterns. The software stack understands the bottlenecks. It's like buying a car where every part was engineered together, versus bolting together parts from five different manufacturers.

Nvidia understood something crucial that its competitors didn't: in the AI era, the vendor that owns the entire stack wins. Google realized this with TPUs. Apple realized it with custom silicon. Amazon realized it and built Trainium and Inferentia chips. Microsoft realized it and started building custom chips for Azure.

But Nvidia had an advantage all these companies lacked: it already had market share. It already had developer mindshare. Every AI researcher, every startup, every company building AI had Nvidia experience. That's not easy to displace.

The soup-to-nuts strategy also protects Nvidia from the rising threat of custom silicon. Every major AI lab now either has a custom chip division or is actively building one. Open AI is working with Broadcom. Meta has been developing its own inference chips. Google, Amazon, Microsoft all have custom silicon. These chips threaten Nvidia's dominance in specific workloads.

But here's what Nvidia realized: you can't build a complete AI infrastructure stack with just custom chips. You need integration. You need software. You need to sell into the ecosystem. So instead of fighting custom chips, Nvidia is saying, "Fine, use your custom chips, but use our CPUs for the CPU-intensive parts. Use our interconnect for the networking. Use our software to manage it all."

It's a brilliant defensive move. It turns potential competition into an argument for bundling.

Why CPUs Suddenly Matter for AI

For years, the AI narrative was simple: GPUs train models, then you deploy them. But that mental model broke down when companies started building agentic AI systems that operate continuously, making decisions, taking actions, reasoning through problems.

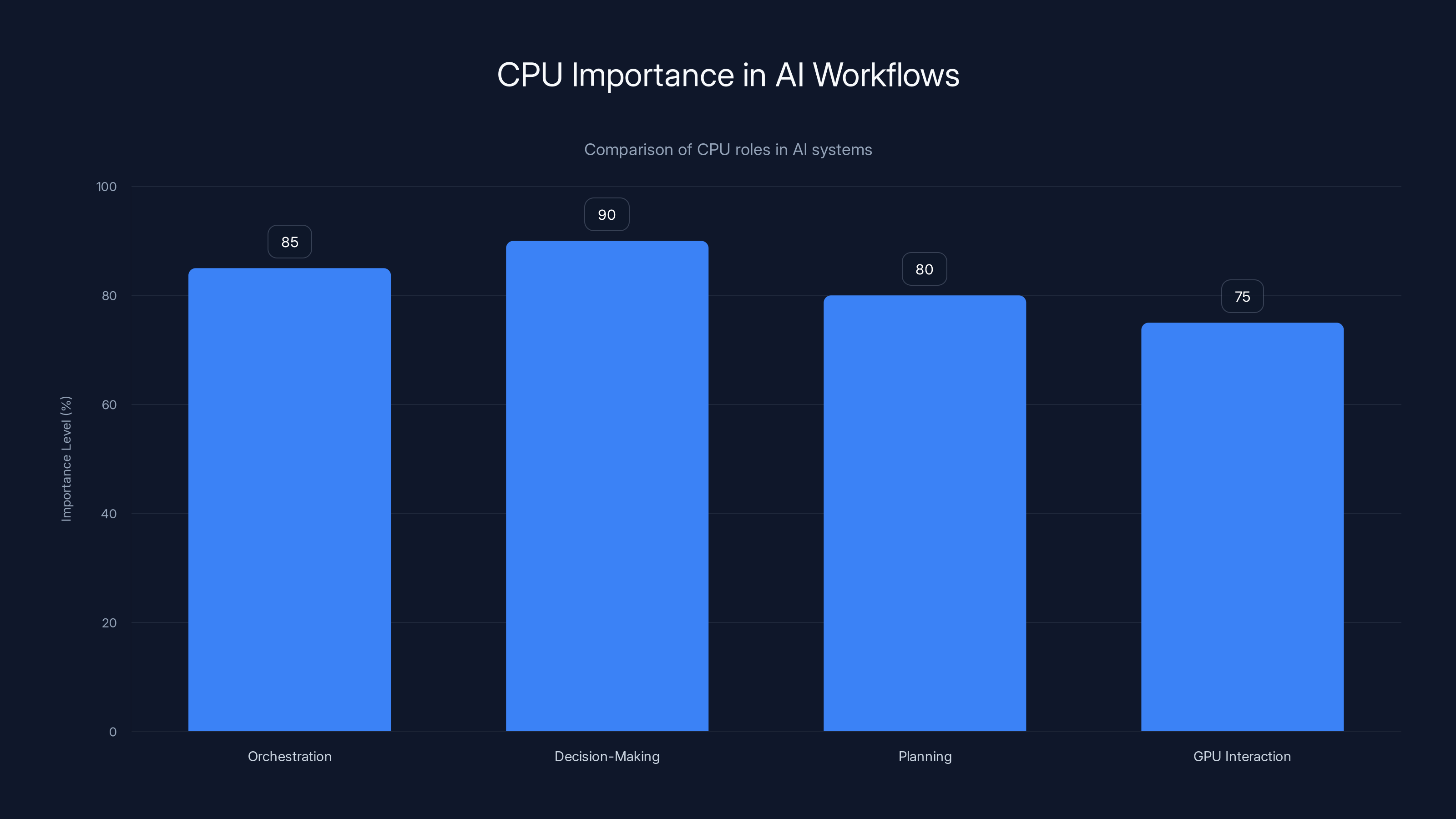

Agentic AI is fundamentally different from the chatbot paradigm we've been obsessed with. A chatbot responds to a prompt. An agent pursues goals. It might break a problem into steps. It might call different tools. It might iterate on solutions. All that orchestration, planning, and decision-making? That's not GPU work. That's CPU work.

Consider a real example: an AI system that manages your calendar, responds to meeting requests, checks conflicts, and proposes alternatives. The reasoning, planning, and decision-making happens on a CPU. The system might call a large language model for specific tasks—that's GPU work. But the overall orchestration is general-purpose computing.

Scale that to enterprise applications. An AI system managing a supply chain. Another optimizing manufacturing. Another handling customer service escalations. All of those require substantial CPU cycles for non-neural-network work.

This is why Ben Bajarin's comment about CPU bottlenecks is so insightful: "If you're one of the hyperscalers, you're not going to be running all of your inference computing on CPUs. You just need whatever software you're running to be fast enough on the CPU to interact with the GPU architecture that's actually the driving force of that computing."

In other words: CPUs have to be good enough to feed GPUs without stalling them. That sounds simple, but it means CPUs need to be very, very good. And they need to integrate seamlessly with the GPU architecture.

Intel's Xeon processors and AMD's EPYC CPUs are general-purpose. They're not optimized for this AI-centric workflow. They're built for web servers, databases, general cloud workloads.

Nvidia's Grace CPUs are different. They're designed from the ground up for datacenters. They're optimized for the specific memory patterns and workload characteristics of AI infrastructure. They're built to work with Nvidia's GPU ecosystem.

When Meta announced it was buying Grace CPUs as a standalone product, it was essentially saying: "We've tested these in our datacenters. They work. They integrate with our GPU infrastructure better than anything else. We're committing to this."

That's a massive vote of confidence from one of the world's largest datacenter operators.

CPUs play a crucial role in AI systems, especially in orchestration, decision-making, and planning, with high importance levels across these areas. Estimated data.

Meta's Infrastructure Ambitions: The Real Story

Meta's announcement of a multibillion-dollar Nvidia chip deal sounds straightforward. But understanding what Meta is actually building reveals something profound about the future of AI infrastructure.

Meta doesn't want to be an AI company. Meta wants to be an AI-native company. That means every product, every service, every internal system should be powered by AI. That's not a marketing line. That's the organizing principle for their entire infrastructure spending.

Mark Zuckerberg has been explicit about this. Meta is committing

What do you do with that much money? You're not buying equipment for the next two quarters. You're building for the next decade. You're building datacenters that don't yet exist. You're optimizing for workloads you're still inventing.

The structure of Meta's deal with Nvidia tells you something about their thinking. They're not just buying GPUs. They're explicitly buying a mix of training and inference hardware. They're deploying CPUs. They're thinking about the complete pipeline: training models, serving them, running inference at scale, integrating those models into every product.

Meta's own research suggests they'll need 1.3 million GPUs by the end of 2025. That's not training GPUs. That's the full complement: training, inference, experimentation, testing, everything.

For context: that's more GPU compute than existed in the entire world five years ago.

Meta is also notably one of the first companies to publicly commit to buying Nvidia's Grace CPUs at scale. That's not accidental. It signals that Meta's infrastructure team has tested these CPUs, integrated them into their architecture, and confirmed they solve real problems.

This is important because it legitimizes Grace in ways marketing never could. If Meta's infrastructure team says "these CPUs work and we're betting billions on them," other companies pay attention.

Nvidia knew this. That's why they partnered with Meta so closely. Meta's infrastructure choices influence the entire industry. When Meta chooses a vendor, startups, enterprises, and other tech giants take notice. That's worth billions in downstream business.

The Inference Computing Revolution

For the first few years of the generative AI boom, everyone talked about training. Training is where the compute intensity lives. Training GPT-4 or Claude or Gemini consumes absurd amounts of electricity and hardware.

But a profound shift is happening. Inference is now the dominant workload. It's the revenue driver. It's where the money is actually spent.

Here's the math: training happens once. Inference happens millions of times. A company trains a model once, maybe updates it monthly. But that model serves millions of queries, each one requiring inference computation.

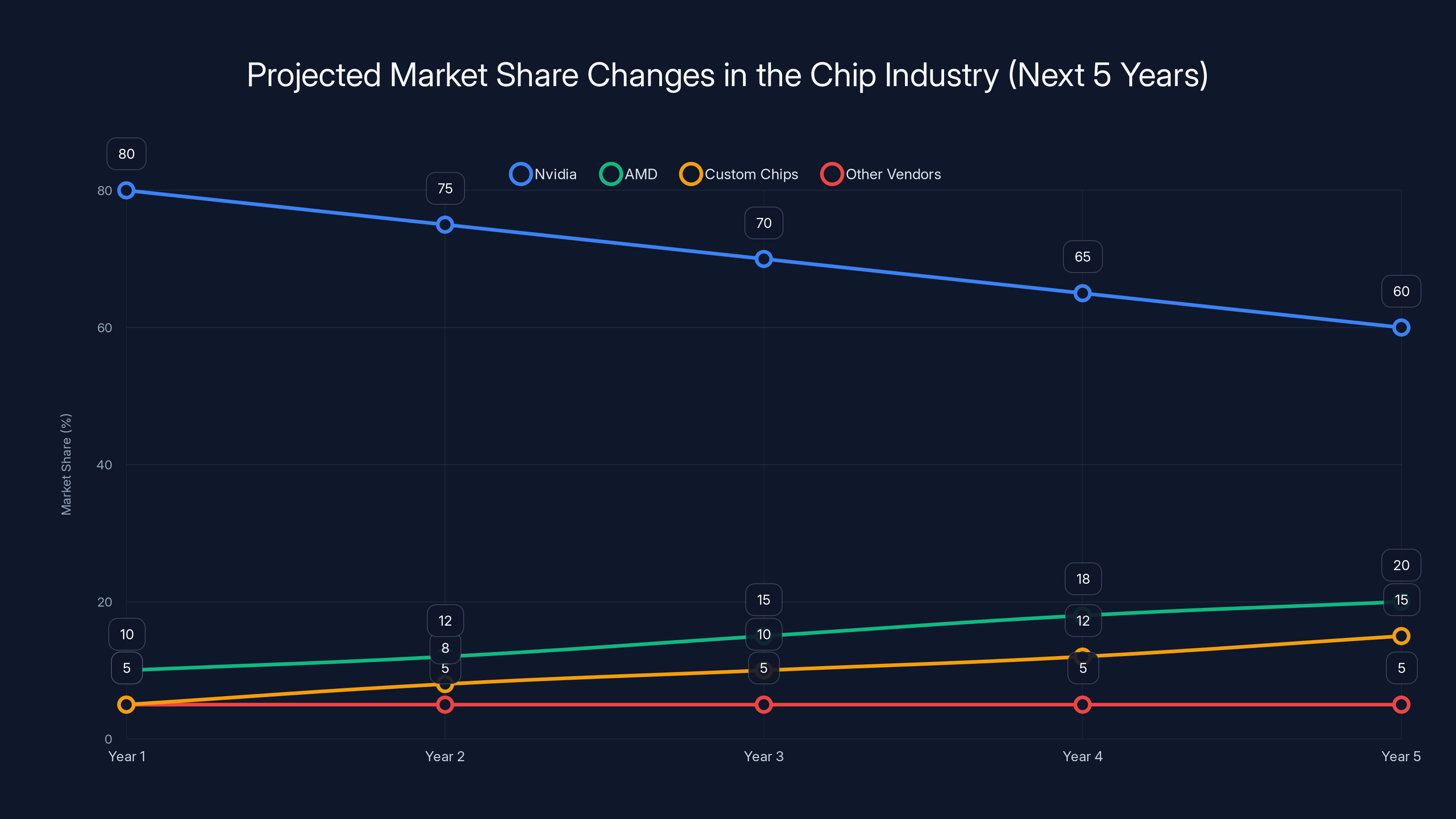

Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang said it clearly two years ago: his estimate was that Nvidia's business was "40 percent inference, 60 percent training." That ratio has almost certainly flipped by now. Some analysts estimate inference is now 70-80% of AI compute spending.

Inference is also fundamentally different from training. Training wants raw compute power and massive memory bandwidth. Inference wants latency, throughput, and efficiency.

A training workload cares about getting to results as fast as possible. An inference workload cares about serving requests within latency budgets—usually milliseconds. A user querying Chat GPT expects a response in under a second. That entire request, from API hit to final token, needs to complete in less time than a human eye blink.

That changes everything about hardware optimization.

GPUs are still important for inference, but they're not the only game in town anymore. CPUs can handle some inference workloads. Specialized inference chips can handle others. TPUs work great for certain problems. The landscape has diversified.

Nvidia recognized this and adjusted strategy accordingly. Instead of saying "buy more GPUs," they started saying "buy our inference solutions," which might include GPUs, CPUs, or specialized inference accelerators.

The Groq acquisition is particularly telling. Groq built specialized chips for low-latency inference. Their whole value proposition is "faster inference than GPUs." That's not theoretical. For certain workloads, Groq's LPUs genuinely outperform Nvidia's H100s on latency.

Nvidia spent $20 billion to acquire Groq, partly for the technology, partly for the talent, but fundamentally because it needed to own the inference story. Nvidia couldn't allow a competitor to own the narrative that "Nvidia is for training, but Groq is for inference."

By acquiring Groq, Nvidia can now say: "We offer the best training solutions and the best inference solutions. Use our complete stack."

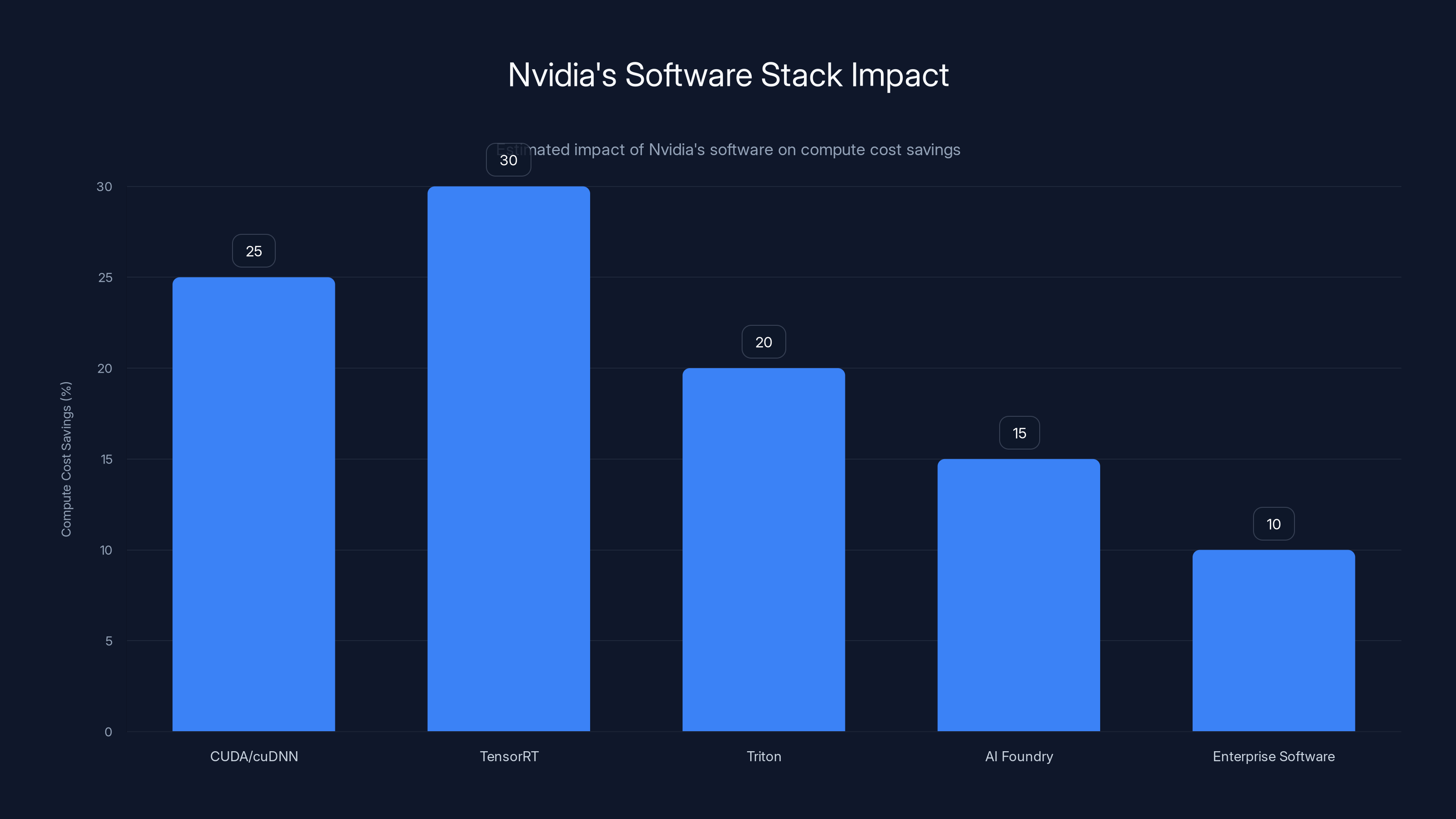

Nvidia's software stack, particularly TensorRT, can lead to significant compute cost savings, estimated at 30% for inference optimization. Estimated data.

The Custom Chip Threat and Nvidia's Response

The scariest thing happening to Nvidia isn't AMD or Intel. It's custom chips built by the companies that actually use the hardware.

Google built TPUs and used them instead of Nvidia GPUs for much of their AI work. Google saves billions by not buying Nvidia hardware.

Amazon built Trainium and Inferentia chips. Meta has its own inference chip efforts. Microsoft is building custom silicon for Azure. Even Open AI, one of Nvidia's biggest customers, is designing its own chips with Broadcom.

This is existential threat to Nvidia's business. If every major AI company builds its own chips and uses them instead of buying Nvidia hardware, Nvidia's growth story collapses.

Nvidia's response has been smart: you can't build a complete ecosystem. You can build training chips. You can build inference chips. But you can't build the entire stack: CPUs, GPUs, networking, software frameworks, developer tools, ecosystem support. That's too hard.

So Nvidia is positioning itself as the company that provides everything else. You want to build custom chips? Fine. Use our CPUs for general-purpose work. Use our interconnect technology (like NVLink) to link your chips together. Use our software (CUDA, cu DNN, and the entire ecosystem). Use our support.

It's a classic defensive strategy: if you can't prevent the threat, absorb it. If companies are building custom chips anyway, Nvidia will make sure those chips integrate with Nvidia's ecosystem.

That's why the "soup-to-nuts" approach matters. It's not just about selling more hardware. It's about making Nvidia indispensable regardless of whether companies use Nvidia GPUs or custom silicon.

But there's a time limit on this strategy. If custom chips get good enough, and companies figure out how to build complete software ecosystems around them, Nvidia's leverage decreases. The next five years will determine whether Nvidia maintains dominance or becomes just one vendor among many.

Agentic AI: The New Compute Frontier

We've been talking about training and inference like they're the only workloads that matter. But something new is emerging that changes the equation entirely: agentic AI.

A chatbot answers a question. An agent pursues goals. That's a profound difference.

An agent might spend hours reasoning through a problem, trying different approaches, learning from failures, iterating toward solutions. That's not continuous GPU utilization. That's orchestration, planning, decision-making, tool use, memory management.

Consider a practical example: an AI agent that manages a company's customer support. The agent receives a ticket. It needs to understand the problem, search the knowledge base, check policies, draft responses, and escalate to humans when necessary.

That workflow isn't pure neural network inference. It's mostly logic, memory access, and decision-making with occasional calls to LLMs or other models. It's the kind of work CPUs excel at.

Scale that across thousands of concurrent agents, each managing different tasks, and you see why CPUs become critical. You need enormous CPU capacity to orchestrate all these agents, even if each individual agent makes relatively light use of GPUs.

This is why Meta is explicitly optimizing for "agentic AI." They understand that the next generation of AI workloads requires a different hardware stack than the current generation.

Agentic AI also requires different software. You need orchestration frameworks. You need memory management systems. You need tools for monitoring, debugging, and controlling agents. You need security systems to ensure agents don't do harmful things.

Nvidia sees this evolution coming. That's why they're not just selling hardware. They're building software ecosystems. They're partnering with companies building agent frameworks. They're creating tools that make it easy to build agents on Nvidia hardware.

The companies that dominate agentic AI won't necessarily be the ones with the most powerful GPUs. They'll be the ones with the best integrated stacks: hardware, software, tools, frameworks, ecosystem support.

Nvidia's betting it can be that company. Meta's deal signals that bet is working.

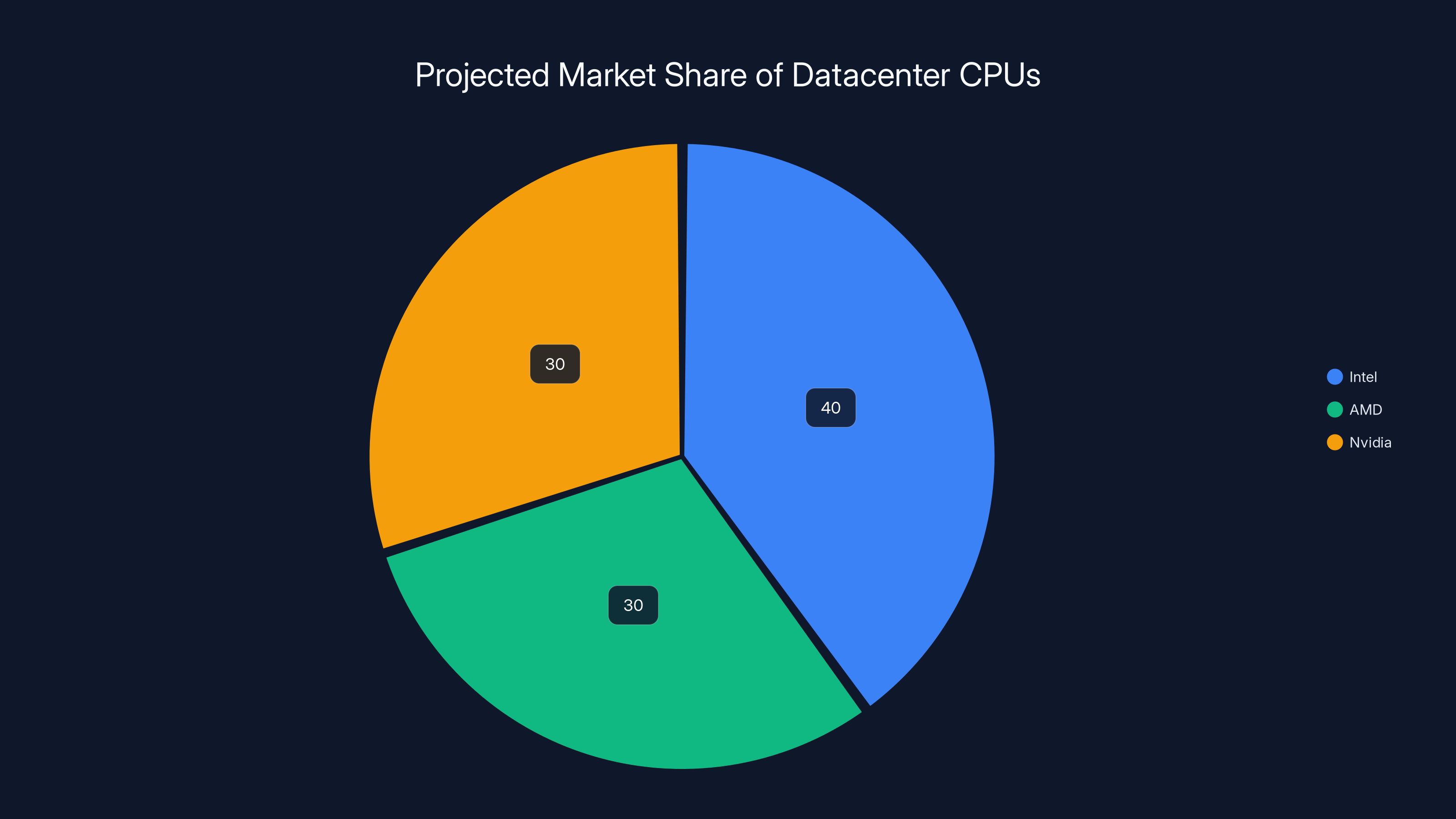

Estimated data suggests Nvidia could capture a significant share of the AI-optimized CPU market by 2025, challenging Intel and AMD's dominance.

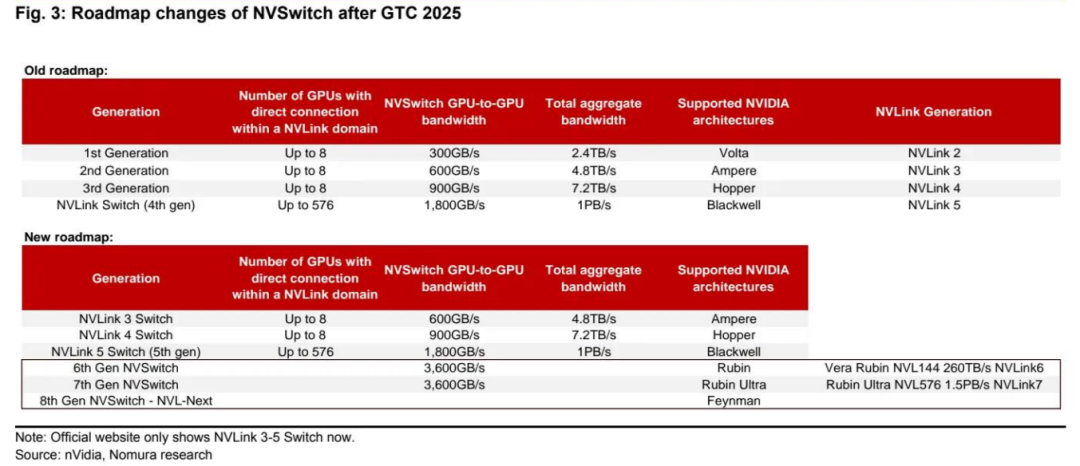

The Interconnect Wars: Why NVLink Matters

Here's something that doesn't get enough attention: the technology connecting chips is becoming more important than the chips themselves.

When you have millions of GPUs working together, the speed and efficiency of the connections between them matters profoundly. A single GPU is useless. A thousand GPUs connected by slow interconnect is almost useless. A thousand GPUs connected by fast, efficient interconnect is incredibly powerful.

Nvidia's NVLink is their proprietary high-speed interconnect. It connects GPUs to each other and to CPUs with much higher bandwidth and lower latency than industry-standard connections like PCIe or Ethernet.

This matters because it creates lock-in. If you design your datacentre around NVLink, you're locked into Nvidia hardware for that entire cluster. You can't mix in custom chips without losing efficiency. You can't switch to AMD or Intel without rebuilding your entire datacenter architecture.

Nvidia understands this deeply. That's why they invest so heavily in interconnect technology. It's not sexy. It doesn't get headlines. But it's the moat that protects them from competition.

When Meta commits to deploying "millions of Nvidia GPUs," they're not just buying processors. They're building infrastructure optimized around NVLink. They're making a decade-long bet on Nvidia's architecture.

That's powerful for Nvidia. It means Meta's datacenters become Nvidia strongholds. Competing vendors have a much harder time getting in because the architecture is optimized for Nvidia.

The interesting dynamic is that as AI workloads become more distributed and complex, interconnect technology becomes more important. This plays to Nvidia's strength. AMD and Intel make good CPUs and GPUs, but their interconnect technology isn't as mature. That gap gives Nvidia protection.

The Price of Dominance: Supply Chain Risks

Here's an uncomfortable truth about Nvidia's dominance: it's fragile in unexpected ways.

Nvidia doesn't actually manufacture chips. Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) does. TSMC manufactures the vast majority of advanced chips in the world, including Nvidia's GPUs.

If TSMC has problems, Nvidia has problems. If geopolitical tensions affect Taiwan, supply chains break. If there's a natural disaster at TSMC's facilities, the entire AI industry suffers.

This isn't theoretical. We saw this play out with GPU shortages in 2021-2023. Demand exceeded supply for months. Prices skyrocketed. The bottleneck was manufacturing capacity, not Nvidia's ability to design great chips.

Nvidia is trying to address this by diversifying manufacturing partners. But TSMC still makes their most advanced chips. That dependency is a strategic vulnerability.

Meta's diversification strategy makes sense in this context. By committing to custom chips, custom CPUs, and working with multiple vendors, Meta reduces its dependency on any single supplier. If Nvidia can't deliver, Meta has alternatives.

This is driving some of the custom chip efforts across the industry. It's not just about having the most optimized hardware. It's about supply chain security and vendor independence.

Over the next five years, expect more companies to build custom chips, not necessarily because they're more efficient, but because they're necessary for supply chain resilience.

Estimated data suggests Nvidia's market share will decrease from 80% to 60% over the next five years as AMD and custom chips gain traction.

The Software Moat: Why CUDA Matters More Than Hardware

If you asked most people what Nvidia's real competitive advantage is, they'd say GPUs. That's wrong.

Nvidia's real competitive advantage is CUDA.

CUDA is Nvidia's parallel computing platform and programming model. It's how developers write code that runs on Nvidia GPUs. It's been the de facto standard for GPU computing for nearly two decades.

Every major ML framework—Py Torch, Tensor Flow, JAX—is optimized for CUDA. Every datacentre engineer knows CUDA. Every AI researcher has CUDA experience.

Switching to competing hardware means rewriting code. It means retraining teams. It means redoing optimization work. The switching cost is enormous.

This is why competitors like AMD struggle despite having good hardware. AMD's ROCm platform is technically capable, but it's not CUDA. It's not as mature. It's not as well-supported. Developers don't want to switch.

Nvidia knows this is their real moat. That's why they invest heavily in CUDA ecosystem support. They make CUDA easier to use. They optimize CUDA for new hardware. They fund developers building tools on CUDA.

The company essentially created a lock-in mechanism that's legal, technical, and cultural. You can't compete with Nvidia just by building better hardware. You have to build better software and ecosystem support simultaneously. That's hard.

This is why Nvidia's acquisition of Groq is interesting strategically. Nvidia got Groq's engineers, expertise, and customer relationships. But Nvidia also got to study Groq's approach to software and inference optimization. That intelligence helps Nvidia improve their own software stack.

Over the next decade, the software moat will be more important than the hardware moat. Companies that can build better developer tools, frameworks, and ecosystem support will win.

Nvidia has a massive head start. But it's not insurmountable. If a competitor builds a genuinely better programming model and ecosystem, developers will eventually migrate. The question is whether that competitor can achieve critical mass before Nvidia builds its moat even thicker.

The CPU Wars: Nvidia vs. Intel vs. AMD

Grace CPUs are Nvidia's entry into a market dominated by Intel and AMD. This is a high-stakes competition because CPUs, unlike GPUs, are everywhere. Every datacenter has CPUs. CPUs matter as much as GPUs for total infrastructure costs.

Intel has been the datacenter CPU king for decades. But Intel's recent struggles are well-documented. Their latest generations have faced delays. Their leadership team has been unstable. Their market share has eroded.

AMD stepped in aggressively. AMD's EPYC CPUs are competitive with Intel's Xeon line. AMD has gained significant market share by offering better performance and better prices.

Now Nvidia is entering with Grace CPUs. Grace is specifically designed for AI workloads in datacenters. It's not a general-purpose CPU like Xeon or EPYC. It's optimized for the specific memory patterns and workload characteristics of AI infrastructure.

Grace isn't trying to compete head-to-head with Intel and AMD on general-purpose computing. It's trying to own the AI-optimized CPU space.

The question is whether that's a large enough market. If most AI datacenters need CPUs specifically optimized for AI work, Grace wins. If general-purpose CPUs work fine, then Grace's advantages don't matter much.

Meta's decision to buy Grace CPUs in large quantities suggests the former. Meta's engineers determined that Grace CPUs solve problems that Xeon or EPYC don't solve well. That's validation from one of the world's most sophisticated datacenter operators.

Over the next few years, expect more companies to follow Meta's lead. When one hyperscaler commits to a hardware choice, others pay attention. If Grace becomes the standard AI CPU, Nvidia has an enormous new business line.

Intel and AMD aren't sitting still. Both are investing heavily in AI-optimized CPUs. Intel has Xeon Scalable processors with AI enhancements. AMD has EPYC with vector processing improvements.

But Nvidia has advantages: it already owns the GPU ecosystem, so CPUs that integrate well with Nvidia GPUs are valuable. It has software expertise in optimization. It has relationships with datacenters.

The CPU market is large enough for multiple players. But Nvidia's integration strategy—selling a complete stack—might give it the edge.

Beyond Chips: The Software Stack Revolution

We've focused a lot on hardware, but the real revolution is happening in software.

Nvidia's recent announcements revealed something profound: the company is becoming a full-stack AI infrastructure vendor. They're not just selling chips. They're selling software, frameworks, tools, and ecosystem support.

This includes:

- CUDA and cu DNN: Programming models and libraries for GPU computing

- Tensor RT: Inference optimization framework that dramatically speeds up model serving

- Triton Inference Server: Production-grade inference platform supporting multiple hardware backends

- Nvidia's AI Foundry: Consulting and optimization services for datacenters

- Enterprise software: Monitoring, management, and orchestration tools

These software offerings are becoming as important as the hardware. A company might buy Nvidia GPUs, but if they use Tensor RT for inference optimization, they save 30% on compute costs. That translates to billions of dollars across a large datacentre.

This is why Nvidia's strategy of acquiring companies like Groq and Mellanox (for networking) makes sense. It's not about the hardware those companies make. It's about absorbing their software expertise and customer relationships.

The software moat is stickier than the hardware moat. You can swap out GPUs. Rewriting software is hard. If your entire inference pipeline is optimized around Tensor RT, switching to a different vendor means reoptimizing everything.

This is also why custom chips built by other companies might not actually threaten Nvidia that much. Google built TPUs, but they still use Nvidia GPUs for many workloads. Meta is building custom chips, but they're committing billions to Nvidia. Amazon built Trainium and Inferentia, but they still use Nvidia for much of their business.

Why? Because Nvidia's software ecosystem is too valuable to abandon, even if the hardware is less than optimal for certain workloads.

Over the next decade, expect Nvidia to invest even more in software. Expect them to build more tools, more frameworks, more ecosystem support. The company that owns the software layer owns the compute layer, regardless of whose hardware runs underneath.

The Broad Market Implications: What This Means for the Industry

Meta and Nvidia's deal is important not because of the dollars involved, but because of what it signals about the future of AI infrastructure.

First, it signals that inference is now as important as training. Companies are optimizing their entire infrastructure around serving models efficiently, not just training them.

Second, it signals that custom chips are inevitable. Every major company will either build custom chips or use them extensively. Nvidia can't prevent this, so it's adapting by making sure custom chips integrate well with Nvidia's ecosystem.

Third, it signals that integrated stacks win. The vendor that sells GPUs, CPUs, interconnect, software, frameworks, and ecosystem support will dominate. Nvidia understands this better than competitors.

Fourth, it signals that datacentre optimization matters more than raw compute. Companies are spending money not just on chips, but on the systems that connect them, manage them, and optimize them.

Fifth, it signals that agentic AI requires different hardware. The next generation of AI workloads will look different from today's LLMs. Companies are preparing infrastructure for that shift.

These signals have implications across the industry:

- For chip vendors: You need a complete stack, not just GPUs or CPUs. Being good at hardware isn't enough anymore.

- For cloud providers: You need to offer AI-optimized infrastructure, not just general-purpose compute. AWS, Azure, and GCP are all building specialized AI offerings.

- For startups: Building infrastructure for agentic AI is the next frontier. Companies are willing to spend enormous money to optimize for this.

- For enterprises: AI infrastructure is capital-intensive. You need to plan for multiple years of increasing spending, optimized for your specific workload patterns.

- For software vendors: Integration with AI infrastructure is critical. Tools that plug into the Nvidia ecosystem have advantages.

The Competitive Landscape: Who Wins, Who Loses

Nvidia is clearly in the strongest position, but competition is fierce and the landscape is shifting.

Intel's Situation: Intel is struggling. Their CPUs were once unbeatable. But leadership missteps, manufacturing delays, and competitive pressure from AMD have eroded their position. Intel's AI offerings (GPUs and specialized chips) exist but lack market traction. Intel needs a decisive win in AI infrastructure. Their Path to change their trajectory in the next 2-3 years.

AMD's Position: AMD is in a better position than Intel. Their EPYC CPUs are competitive. Their MI300 GPUs are gaining traction. But AMD's software ecosystem doesn't match Nvidia's. AMD's challenge is building developer mindshare and ecosystem support fast enough to compete with Nvidia's ten-year head start in CUDA.

Google's Play: Google builds TPUs and uses them extensively internally. But Google's TPUs are optimized for Google's workloads. They're not easily available to others. Google's strategy seems to be: build the best chips for internal use, offer some cloud services, but don't compete directly with Nvidia on general-purpose AI hardware.

Custom Chip Builders: Groq, Cerebras, Graphcore, and others built specialized chips for specific workloads. Some are good. But they've all struggled to achieve mainstream adoption. Nvidia's acquisition of Groq might end the dream of independent specialized chip makers. If Nvidia can absorb them faster than they can build momentum, it reduces the threat.

Open-Source Momentum: Open source frameworks like Py Torch are vendor-agnostic. That's good for competition. But these frameworks still run best on Nvidia hardware. Improving support for AMD, Intel, and custom chips is ongoing, but Nvidia's head start in optimization is huge.

The most likely outcome: Nvidia maintains dominance, but competition increases. Market share erodes slightly as companies build custom chips and AMD gains traction. But Nvidia's software moat keeps it ahead.

Looking Forward: The Next Five Years

Here's what we're likely to see in the next five years:

Year 1-2: Continued Nvidia dominance. Meta and other hyperscalers continue massive infrastructure spending. Grace CPUs gain traction. Custom chip efforts accelerate across the industry.

Year 2-3: AMD's MI300 and next-gen chips start gaining real market share. Custom chips from Meta, Amazon, and others show up in production workloads. Software interoperability improves, making chip switching easier.

Year 3-4: The GPU market becomes less concentrated. Nvidia still dominates, but AMD, custom chips, and specialized vendors capture 20-30% of market share. CPUs and interconnect become competitive differentiators.

Year 4-5: Agentic AI dominates workloads. CPU and general-purpose compute become more important relative to GPUs. Nvidia's software ecosystem is even more entrenched. New competitors emerge focused on specific workload categories (inference, training, agent orchestration).

The wildcard is geopolitics. If US-China relations deteriorate further, chip export restrictions could reshape the entire industry. Nvidia's international business could be affected. Custom chip efforts might accelerate as companies fear supply interruptions.

Another wildcard is breakthroughs in chip efficiency. If someone develops a new architecture that's dramatically more efficient than GPUs, everything changes. But breakthroughs in silicon efficiency are getting harder. Moore's Law is slowing. Physics is stubborn.

Most likely: Nvidia maintains clear leadership, but the gap narrows. The market becomes more competitive, more diverse, and more specialized. Success requires offering integrated stacks, not just individual components.

FAQ

What exactly does Nvidia's Grace CPU do?

Nvidia's Grace CPU is a datacentre-grade processor specifically optimized for AI workloads and integrated infrastructure. Unlike general-purpose CPUs like Intel's Xeon or AMD's EPYC, Grace is designed to handle the specific computational patterns of AI applications while integrating seamlessly with Nvidia's GPU ecosystem through technologies like NVLink, ensuring CPUs don't become a bottleneck when feeding GPUs intensive workloads.

Why is Meta buying CPUs instead of just more GPUs?

Meta is building agentic AI systems that require orchestration, decision-making, and general-purpose computing alongside GPU-intensive inference. CPUs handle the coordination, routing, and logic that GPUs aren't optimized for. Buying both GPUs and CPUs ensures the datacentre can handle complete AI workflows efficiently without CPUs becoming the limiting factor.

How does Nvidia's "soup-to-nuts" strategy protect it from custom chip competition?

Nvidia's strategy acknowledges that custom chips are inevitable, but argues that companies still need Nvidia's CPUs, interconnect technology (NVLink), software frameworks, and ecosystem tools to build complete solutions. Even if a company builds custom training chips, they might use Nvidia GPUs for inference, Nvidia CPUs for orchestration, and Nvidia Tensor RT for optimization, maintaining Nvidia's central position.

What's the difference between training and inference compute?

Training requires massive parallel processing to adjust billions of model parameters through many iterations, favoring raw compute power. Inference serves already-trained models to users, prioritizing low latency and efficiency. Training happens once per model; inference happens millions of times. This fundamental difference explains why companies are now diversifying hardware strategies beyond just buying high-end GPUs.

Why is the CUDA ecosystem so important for Nvidia's dominance?

CUDA is the programming model and software platform that developers use to write code for Nvidia GPUs. After nearly two decades of development, every major AI framework is optimized for CUDA, every engineer knows it, and every datacentre uses it. Switching to competing hardware means rewriting code and retraining teams, creating a massive switching cost that insulates Nvidia from competition more effectively than hardware advantages alone ever could.

Could AMD or Intel actually displace Nvidia in AI infrastructure?

Unlikely in the short term. AMD has competitive hardware but lacks Nvidia's software ecosystem and developer mindshare. Intel is currently struggling with leadership and execution. For either company to displace Nvidia, they'd need 5-10 years of flawless execution building software ecosystems, gaining developer adoption, and establishing new standards. Nvidia's lead is too substantial to overcome quickly, though both companies will capture market share as alternatives mature.

The Bottom Line: Why This Deal Matters

Nvidia's partnership with Meta isn't just about selling more chips. It's a statement about the future of AI infrastructure and a defensive move against rising competition.

The deal signals that the era of single-vendor dominance is ending. But it also signals that Nvidia is positioning itself as the vendor that controls the full stack: GPUs for training and inference, CPUs for orchestration, interconnect for communication, software for optimization.

Meta's choice to commit billions to this integrated stack—including the explicitly unusual decision to buy Grace CPUs at scale—suggests that integrated approaches actually work better than piecing together best-of-breed components.

For the next decade, success in AI infrastructure will belong to the company that can sell not just the fastest hardware, but the most coherent, integrated, well-supported complete system. Nvidia is currently ahead on that dimension, and the Meta deal extends that lead.

But the competition is coming. AMD is improving. Custom chips are proliferating. Open-source software is advancing. The CPU wars are intensifying.

The real test for Nvidia isn't whether they maintain dominance—they probably will. It's whether they can stay far enough ahead that competitors never catch up. Given Nvidia's execution to date, that seems likely. But technology is humbling, and the next five years will test Nvidia's ability to innovate faster than the rising competition.

One thing is certain: the days of companies buying GPUs in isolation are over. The future belongs to integrated stack providers. And Nvidia has a commanding lead in building that stack.

Key Takeaways

- Meta's commitment to large-scale Grace CPU deployments signals CPU efficiency is now critical for AI infrastructure beyond just GPUs

- Agentic AI requires diverse compute: GPUs for inference, CPUs for orchestration, custom chips for specialized workloads

- Nvidia's 'soup-to-nuts' strategy bundles hardware, software, interconnect, and ecosystem support to defend against custom chip competition

- Inference workloads now represent 60-80% of AI compute spending, fundamentally changing hardware requirements from training-centric models

- CUDA's software moat is more defensible long-term than hardware advantages, explaining why ecosystem support matters more than raw compute

Related Articles

- AI Memory Crisis: Why DRAM is the New GPU Bottleneck [2025]

- Alibaba's Qwen 3.5 397B-A17: How Smaller Models Beat Trillion-Parameter Giants [2025]

- Agentic AI & Supply Chain Foresight: Turning Volatility Into Strategy [2025]

- GPU Price Hikes Hit Hard: Nvidia Faces Brutal Global Markup Reality [2025]

- MSI Vector 16 HX AI Laptop: Local AI Computing Beast [2025]

- AI Replacing Enterprise Software: The 50% Replatforming Shift [2025]

![Nvidia and Meta's AI Chip Deal: What It Means for the Future [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/nvidia-and-meta-s-ai-chip-deal-what-it-means-for-the-future-/image-1-1771443498171.jpg)