Introduction: The AI Infrastructure Arms Race Gets Real

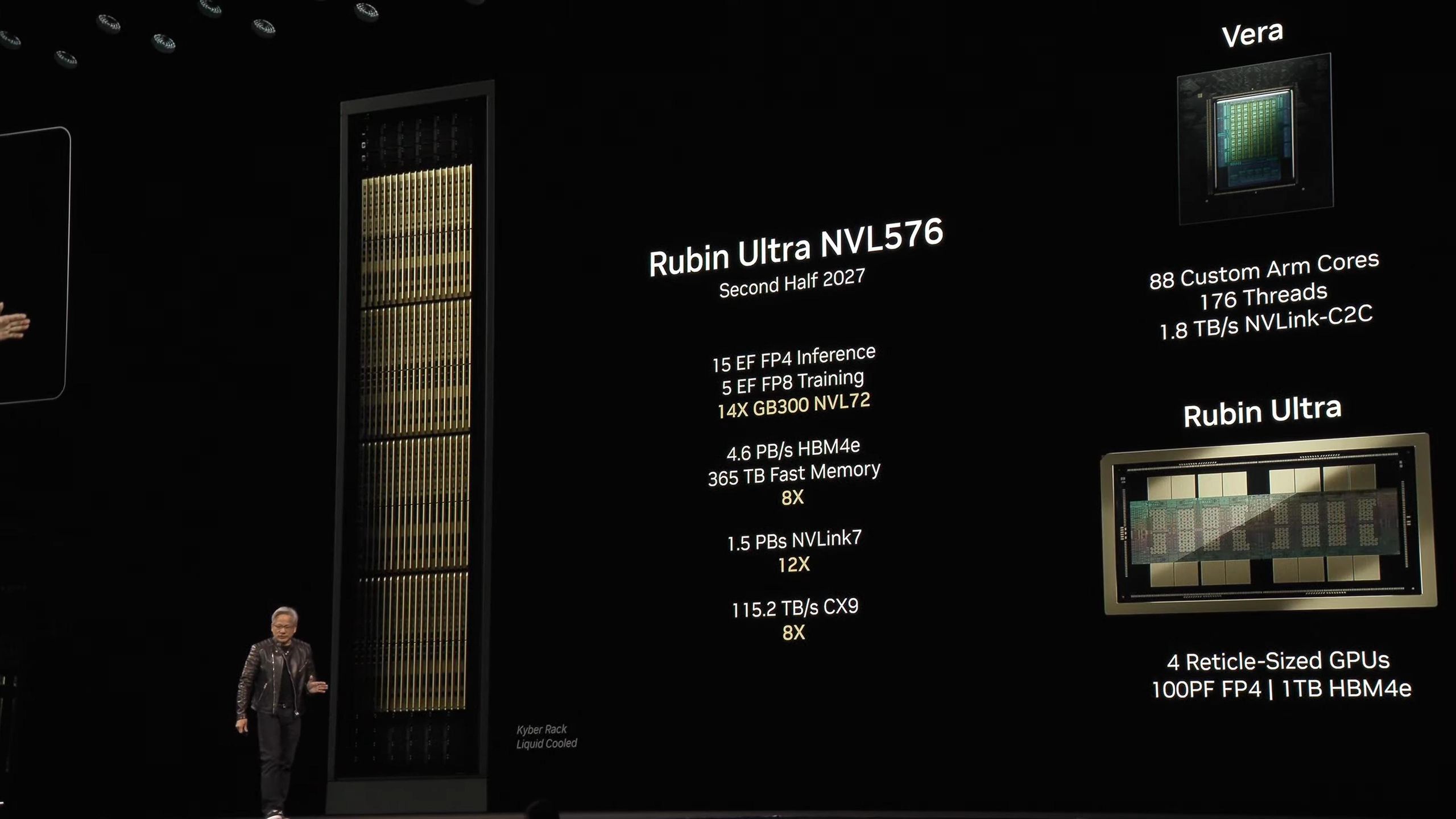

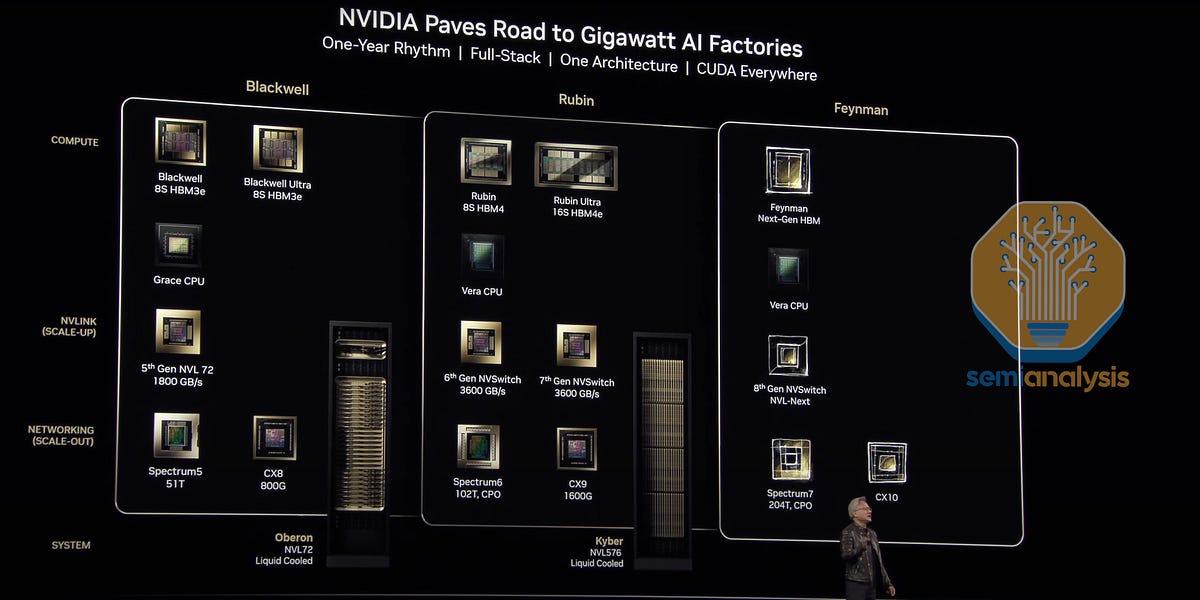

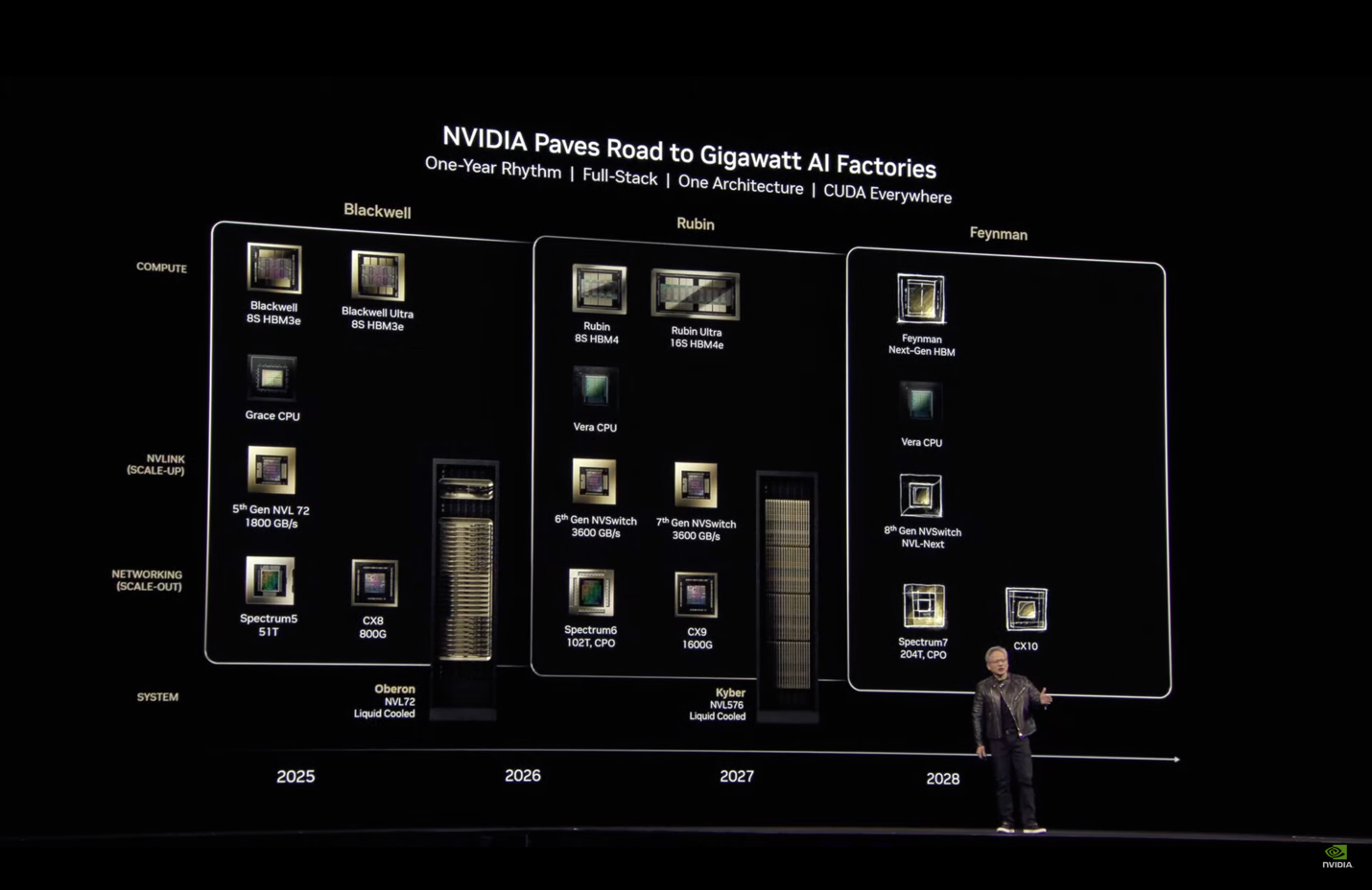

When Jensen Huang took the stage at CES 2026, the tech industry was already holding its breath. Nvidia doesn't announce chip architectures casually anymore—every launch matters, reshapes entire data center strategies, and moves billions in capital allocation decisions. The Rubin architecture was supposed to be the future of AI computing, and after months of speculation, it finally arrived.

But here's what's important to understand: this isn't just another incremental chip upgrade. Rubin represents a fundamental rethinking of how AI infrastructure should work. Named after astronomer Vera Florence Cooper Rubin, the architecture attacks the most pressing problem facing everyone building large-scale AI systems right now: the computational requirements are exploding faster than we can supply them.

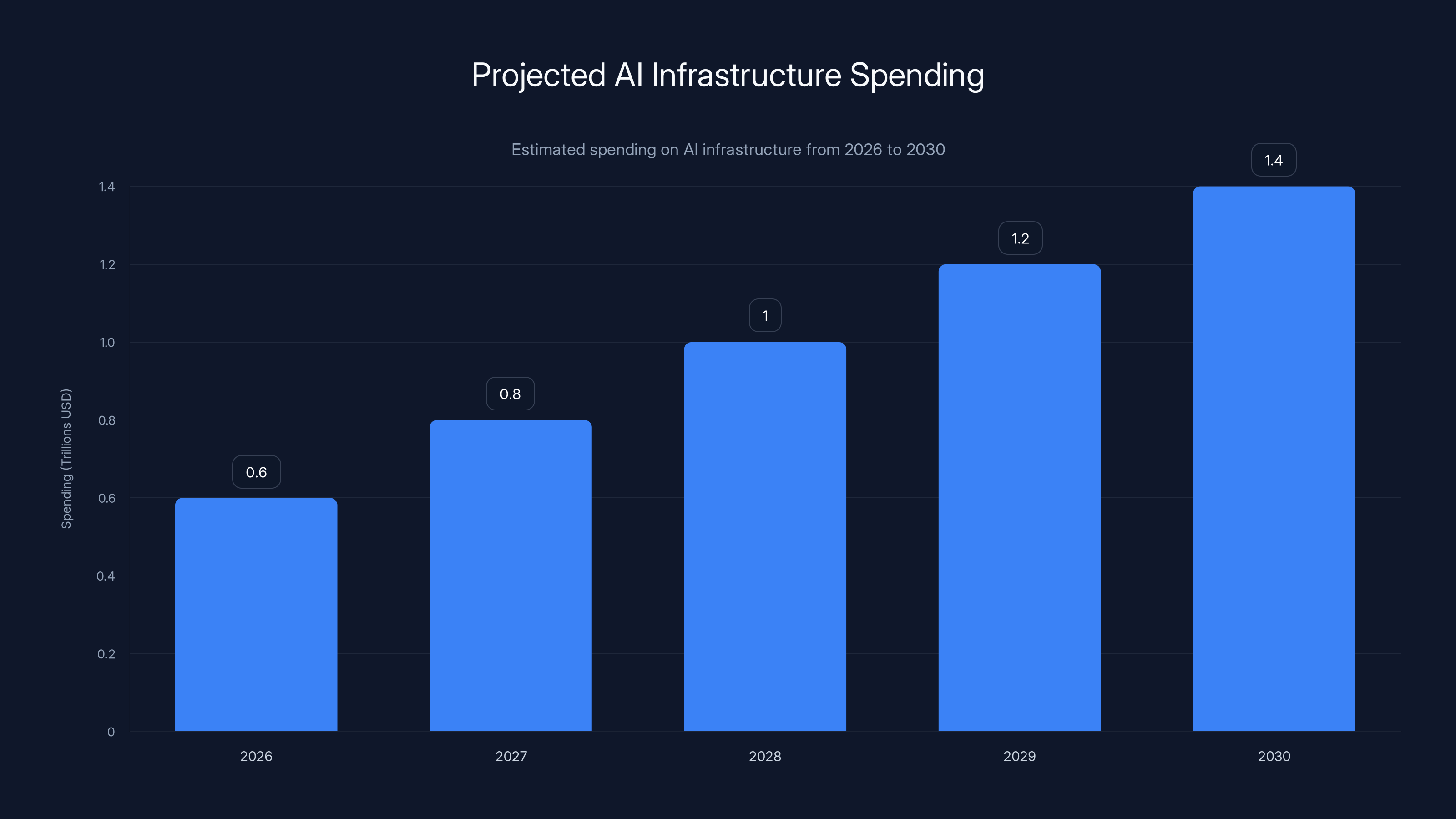

We're talking about companies needing to spend billions on data centers just to keep up with model training and inference demands. The AI infrastructure spending is predicted to reach

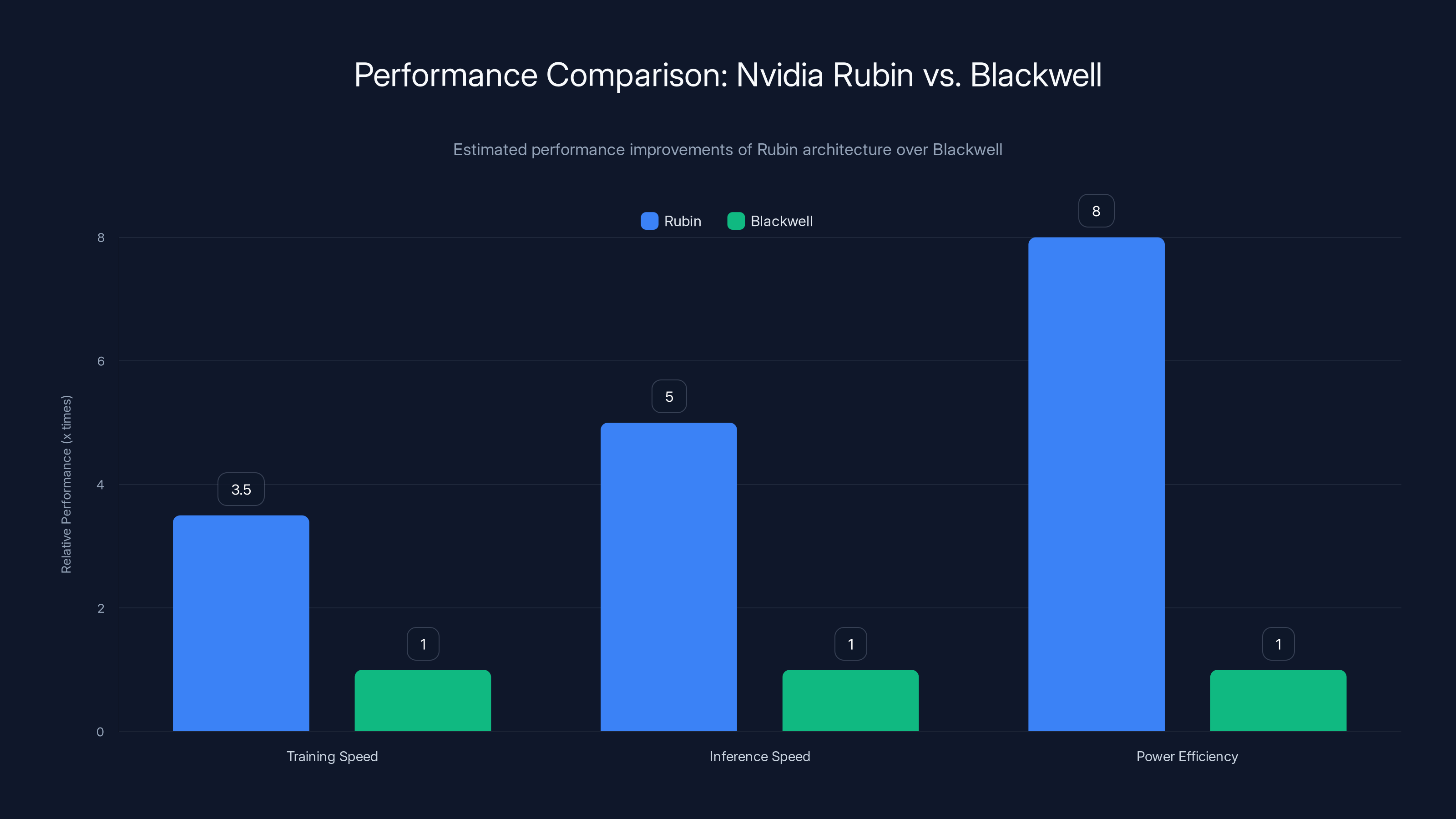

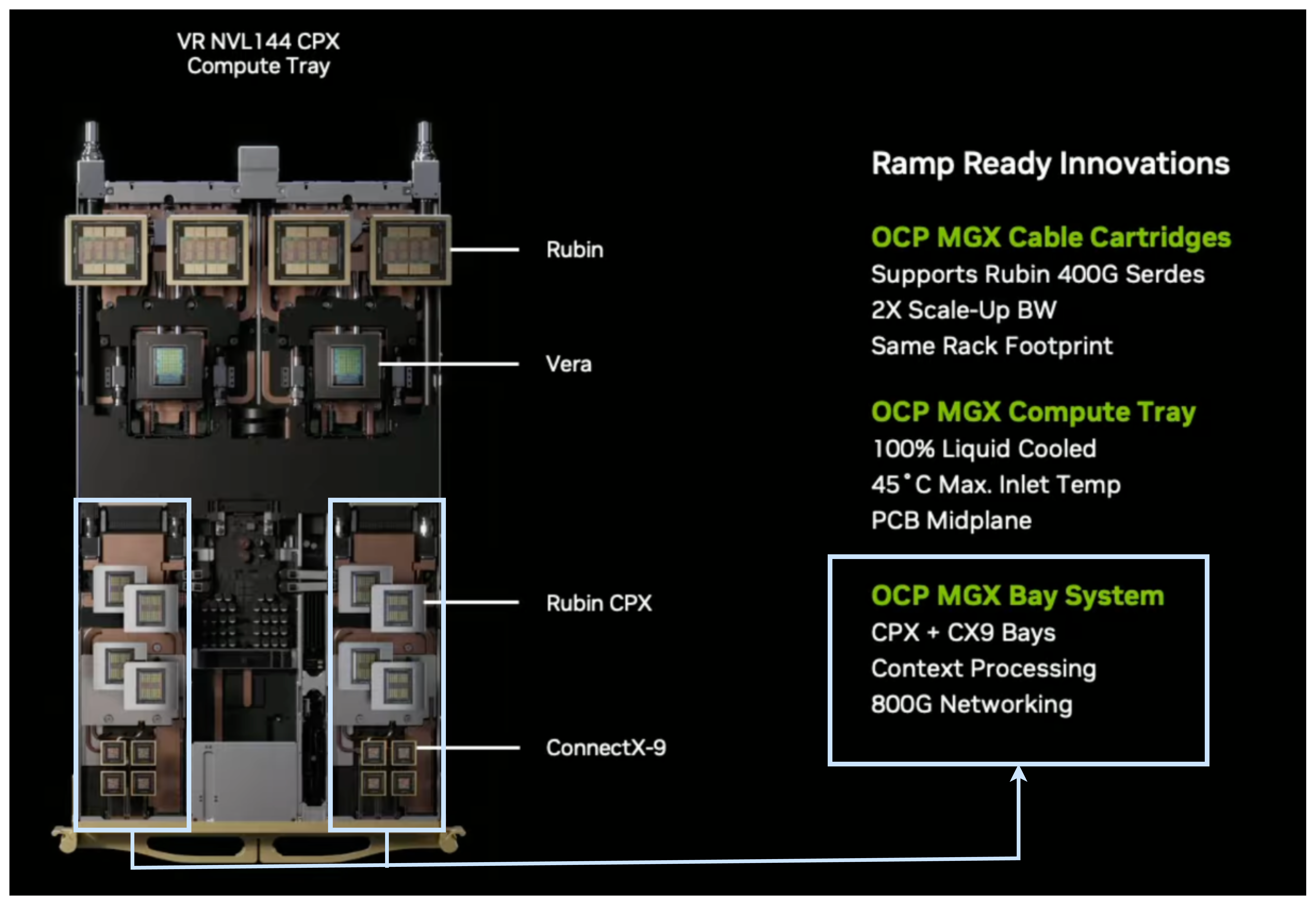

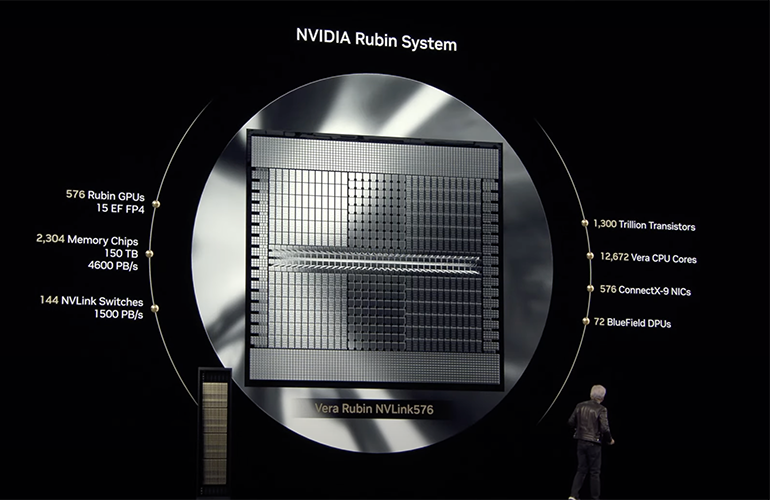

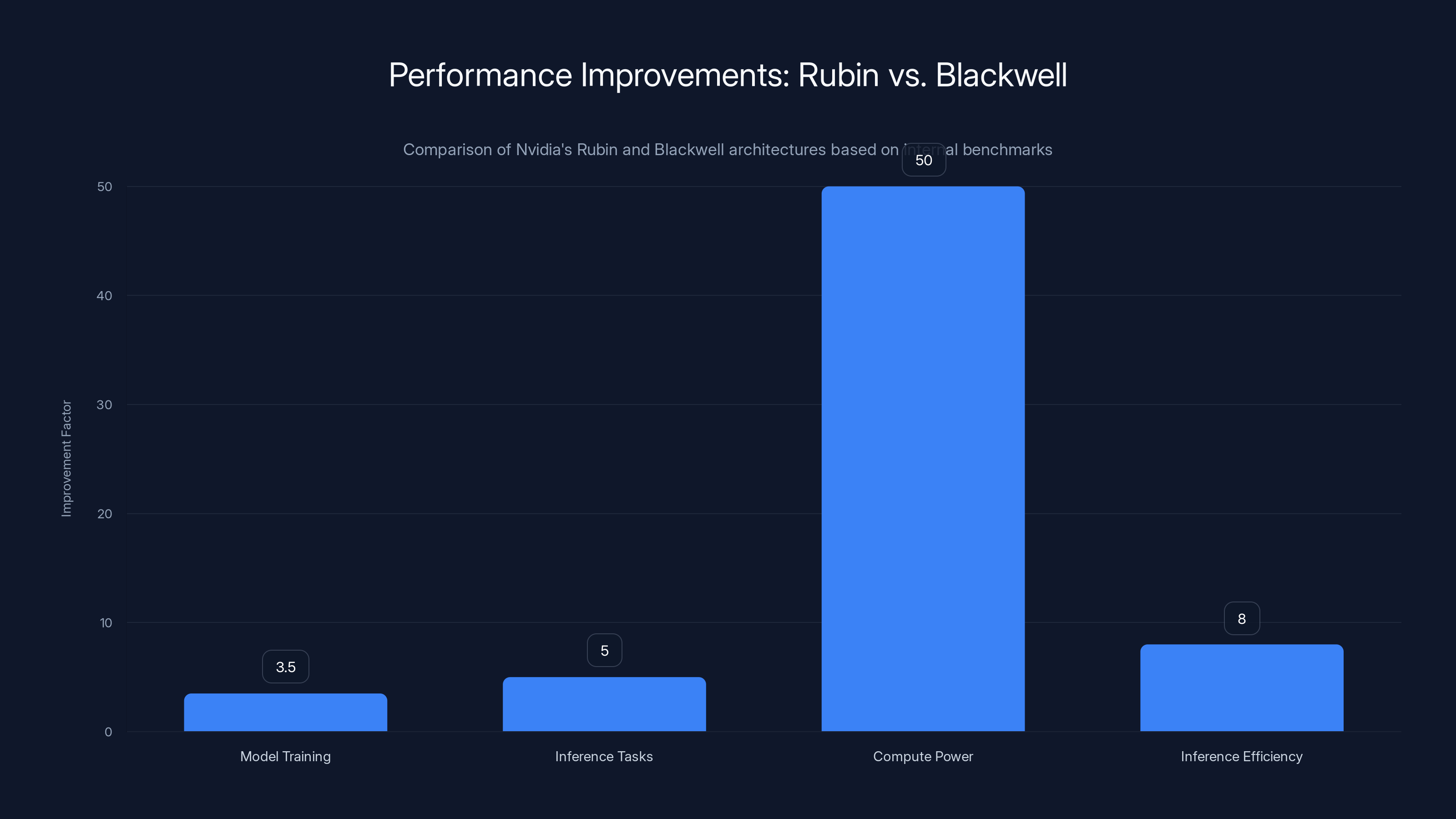

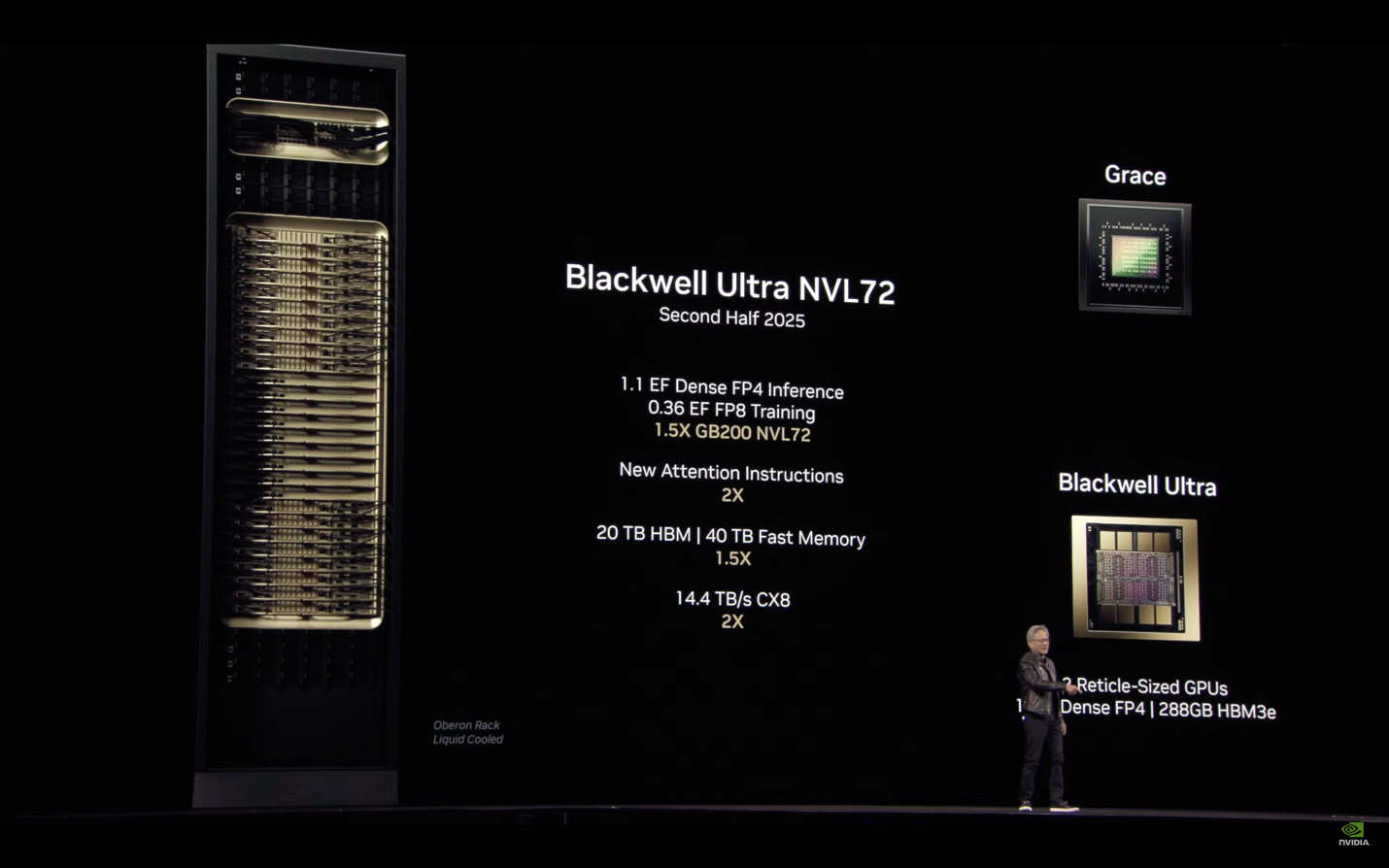

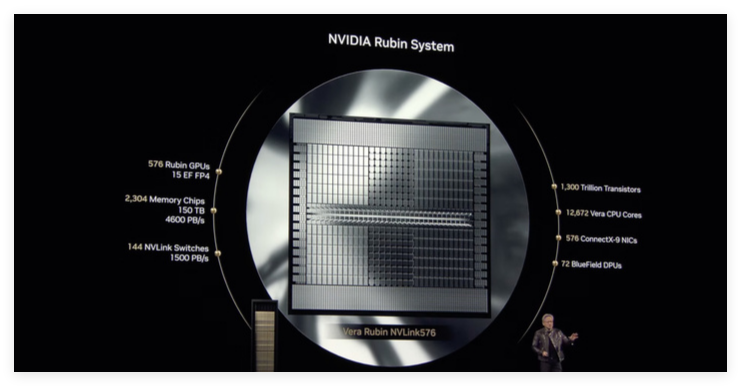

The new architecture isn't a single chip. It's a six-chip ecosystem designed to work together, addressing every bottleneck that's been crushing data center operators. Storage limitations? Fixed. Interconnection bottlenecks? Solved. CPU limitations for agentic workflows? There's now a dedicated Vera CPU for that. And the raw performance numbers are staggering: 3.5x faster for training, 5x faster for inference, reaching up to 50 petaflops of compute.

But performance numbers are only part of the story. What really matters is understanding why Rubin exists, how it works, and what it means for the future of AI infrastructure. Because if you're building anything with AI, you care about this. It affects cost, speed, latency, and what's even possible to build.

TL; DR

- Six-chip architecture: Rubin isn't a single processor but a complete ecosystem including GPU, CPU, and storage components designed to work in concert

- Massive performance gains: 3.5x faster training, 5x faster inference, and 8x more inference compute per watt compared to Blackwell

- Production ready: Already in full production as of early 2026, with adoption planned by major cloud providers and AI labs

- Addresses real bottlenecks: New storage tier and improved interconnection solve KV cache demands, memory bandwidth issues, and interconnect constraints

- Enterprise adoption path: Being deployed in supercomputers like HPE's Blue Lion and Lawrence Berkeley's Doudna system, plus partnerships with OpenAI, Anthropic, and AWS

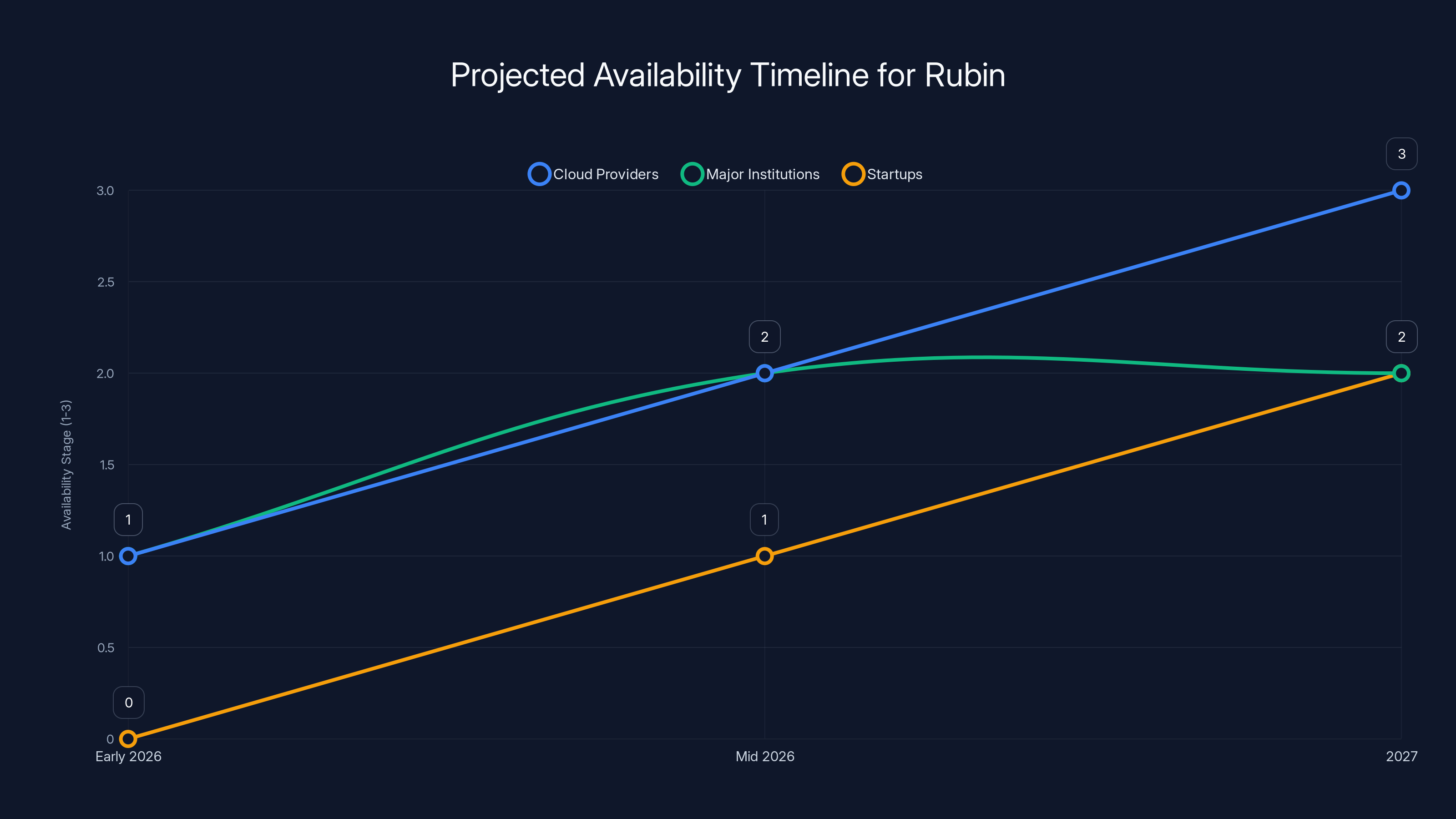

Rubin is expected to be available to cloud providers and major institutions by mid-2026, with startups gaining access by 2027. Estimated data.

The Problem Rubin Solves: Why We Need Better AI Infrastructure

To understand why Rubin matters, you need to understand the constraint it's attacking. AI compute demand isn't just growing—it's growing exponentially. We're not talking about incremental increases. We're talking about scenarios where a new AI model requires 10x the compute of the previous generation.

When you're training or running massive language models, you hit several critical bottlenecks. The first is obvious: raw compute. You need GPU cores doing matrix multiplications at insane speeds. But the second bottleneck is way less obvious to most people: memory. Specifically, the KV cache, which stores key and value vectors that AI models use to understand context.

Here's the practical problem: when you're running inference on a large model serving thousands of concurrent users, your KV cache can explode in size. If you're doing agentic AI—where the model reasons for longer periods, makes decisions, takes actions, and reasons again—the cache grows even more. You need to store more data, faster, and you need to access it with lower latency.

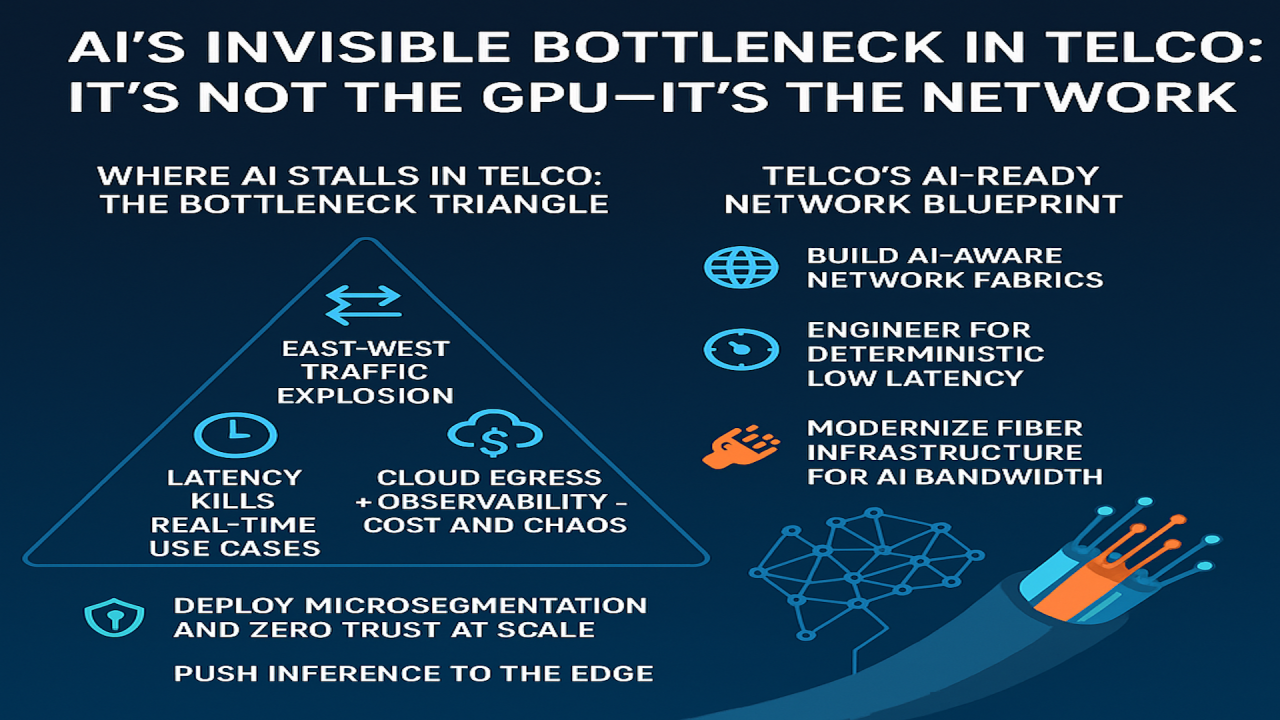

The third bottleneck is interconnection. When you're building a supercomputer with thousands of GPUs, they need to talk to each other incredibly fast. If the connection between chips becomes a bottleneck, you've wasted all your compute power. It's like building a 10-lane highway and then connecting it to a single-lane road.

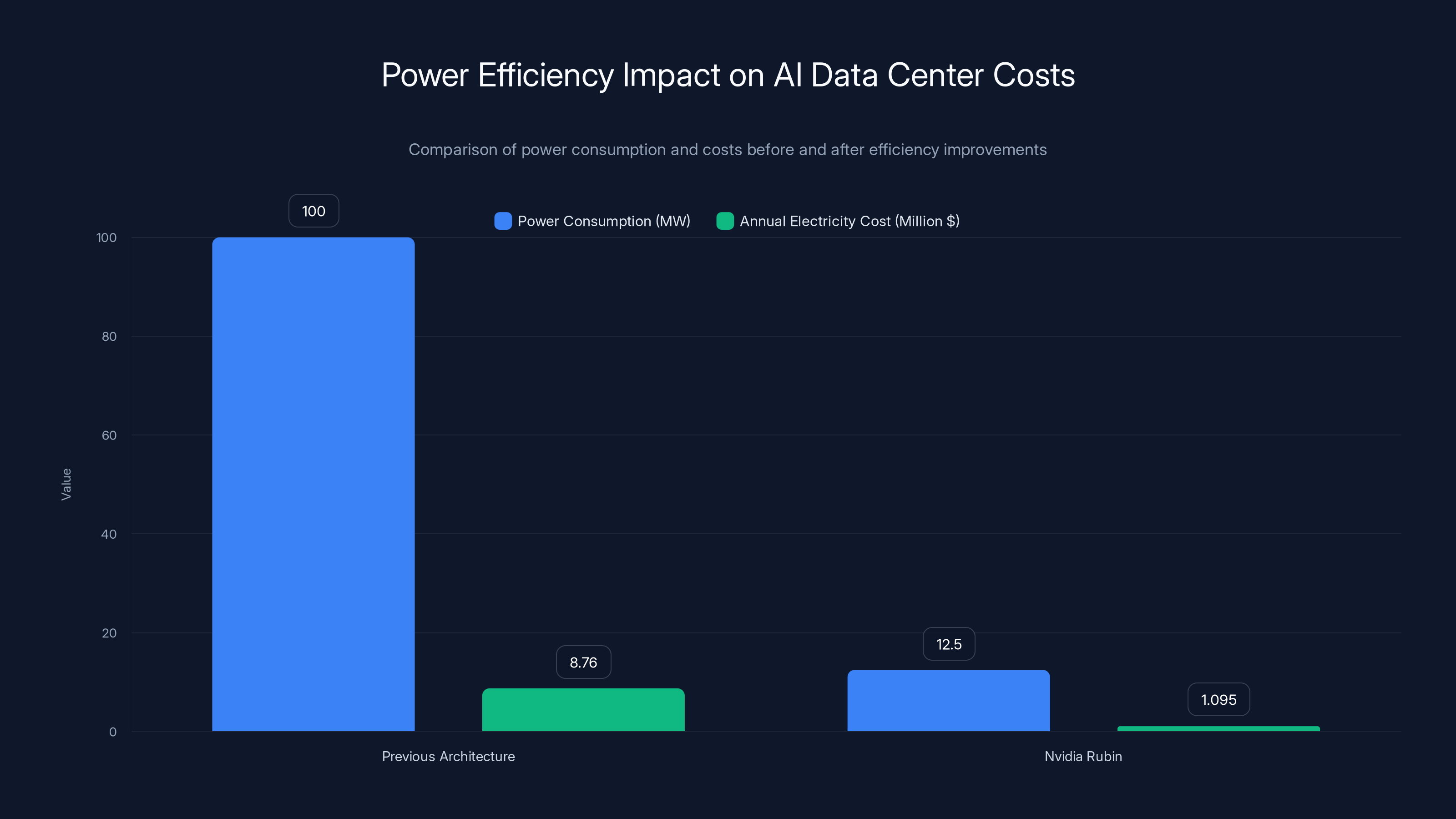

The fourth bottleneck is power efficiency. Data centers are running out of power. Literally. The electrical grid in some areas can't support more massive AI infrastructure. So every watt matters. If Nvidia can do the same work with less power, that's not just a nice optimization—it's a requirement for continued growth.

Previous architectures like Blackwell made progress on these problems, but Rubin attacks them head-on with a completely different approach. Instead of trying to solve everything with a better GPU, Rubin builds an entire system where each component is optimized for its specific role.

The Six-Chip Architecture: How Rubin Works

Here's where Rubin gets interesting. It's not a monolithic design. It's six separate chips working together:

The Vera GPU sits at the center—this is what most people think of when they imagine a high-end AI processor. It's where the actual neural network computations happen. But unlike previous generations, the Vera GPU isn't trying to do everything. It's been optimized specifically for transformer models and the specific workloads that are actually running in production.

The Vera CPU is new, and it's specifically designed for agentic reasoning. Why does this matter? Because when you run an AI agent—a system that reasons, makes decisions, and takes actions—you need fast CPU performance for control flow, decision logic, and orchestration. You can't just throw a GPU at that problem. You need a real CPU that can handle branching logic, conditional execution, and rapid decision-making.

The Bluefield processors handle networking and storage, and they've been significantly upgraded. This is where the real innovation happens for many use cases. Bluefield can now handle more complex networking tasks without burdening the main GPU, and it can manage the new storage tier that's been added to the architecture.

The new storage tier is perhaps the most important practical innovation. It's not traditional VRAM and it's not main memory. It's a new category of high-bandwidth, high-capacity storage that sits between the GPU's cache and system memory. For KV cache workloads, this is transformative. Instead of cramming everything into limited GPU memory or spilling to main memory (which is slow), you have a sweet spot that's fast enough and large enough for modern AI demands.

The NVLink interconnect has been improved for better GPU-to-GPU communication. When you're building systems with dozens or hundreds of GPUs, the ability to move data between them quickly and efficiently is critical. The improved NVLink reduces latency and increases bandwidth compared to previous generations.

Finally, the integration between all these components is what makes it work. These aren't six independent chips bolted together. They're designed to work as a unified system, with optimized data paths and communication protocols.

Rubin architecture offers 3.5x faster training, 5x faster inference, and 8x better power efficiency compared to Blackwell. Estimated data based on reported improvements.

Performance Numbers: What the Benchmarks Actually Mean

Nvidia released specific performance metrics for Rubin compared to Blackwell. Here's what they actually mean:

3.5x faster on model training tasks - This is significant but also important to understand the context. Nvidia likely tested this on large-scale transformer training at specific precision levels. Your actual speedup will depend on your specific workload, batch sizes, and model architecture. Some workloads might see different results, but 3.5x is in the ballpark of what we'd expect from a generational improvement.

5x faster on inference tasks - This is even more meaningful for production systems because inference is what most users care about. Faster inference means lower latency, better user experience, and fewer GPUs needed to serve the same number of concurrent users. At 5x improvement, you could potentially serve five times more traffic with the same hardware.

50 petaflops of compute - A petaflop is one quadrillion floating-point operations per second. For context, the entire internet's data centers combined couldn't do 50 petaflops a few years ago. This gives you a sense of the absolute scale of these machines. The largest supercomputers in the world are now measured in tens of petaflops, and having a single architecture capable of 50 petaflops is remarkable.

8x more inference compute per watt - This is perhaps the most important metric for data center economics. If you can do the same inference with one-eighth the power consumption, you've just made AI infrastructure 8x more economical. That changes the entire business model for AI services. It means more companies can afford to run AI, and it means the environmental impact of AI drops significantly.

These numbers are impressive, but context matters. Nvidia's benchmarks are internal tests on their own systems, using their own software optimizations. Real-world results in production systems might be different. But the gap between benchmarks and reality has historically been smaller with Nvidia's hardware compared to competitors, so these numbers are probably reasonably representative.

The KV Cache Problem: Why This Matters for Long-Context AI

Let's dig deeper into one specific problem that Rubin solves, because it's crucial for understanding why this architecture exists: the KV cache explosion.

When a language model processes text, it doesn't process the entire input at once. Well, technically it does through parallel processing, but conceptually, it builds up a cache of "keys" and "values" that represent the information it's seen so far. This cache is essential for attention mechanisms, which are what allow transformers to understand relationships between distant parts of the input.

For a 4,000-token input (roughly 3,000 words), you need to store keys and values for all 4,000 tokens. For a 100,000-token input (75,000 words), you need 25x more cache. And here's where it gets brutal: when you're serving multiple users concurrently, each user has their own KV cache. If you're serving 1,000 concurrent users with 100,000-token contexts, you need to store 1,000 separate caches simultaneously.

With previous architectures, you'd have to choose: either use smaller context windows and waste the potential of your model, or accept terrible memory efficiency. Rubin's new storage tier solves this by providing a large, fast memory pool specifically for this use case.

Nvidia's Dion Harris explained it directly: the new tier lets you "scale your storage pool much more efficiently" without constraining the compute device. In practical terms, this means you can run longer-context models, serve more concurrent users, and not have to spend a fortune on extra GPUs just to handle memory requirements.

For companies building AI applications, this is genuinely transformative. It means you can offer 100,000-token context windows to users without the memory bottleneck killing your economics.

Production Status and Timeline: It's Actually Happening Now

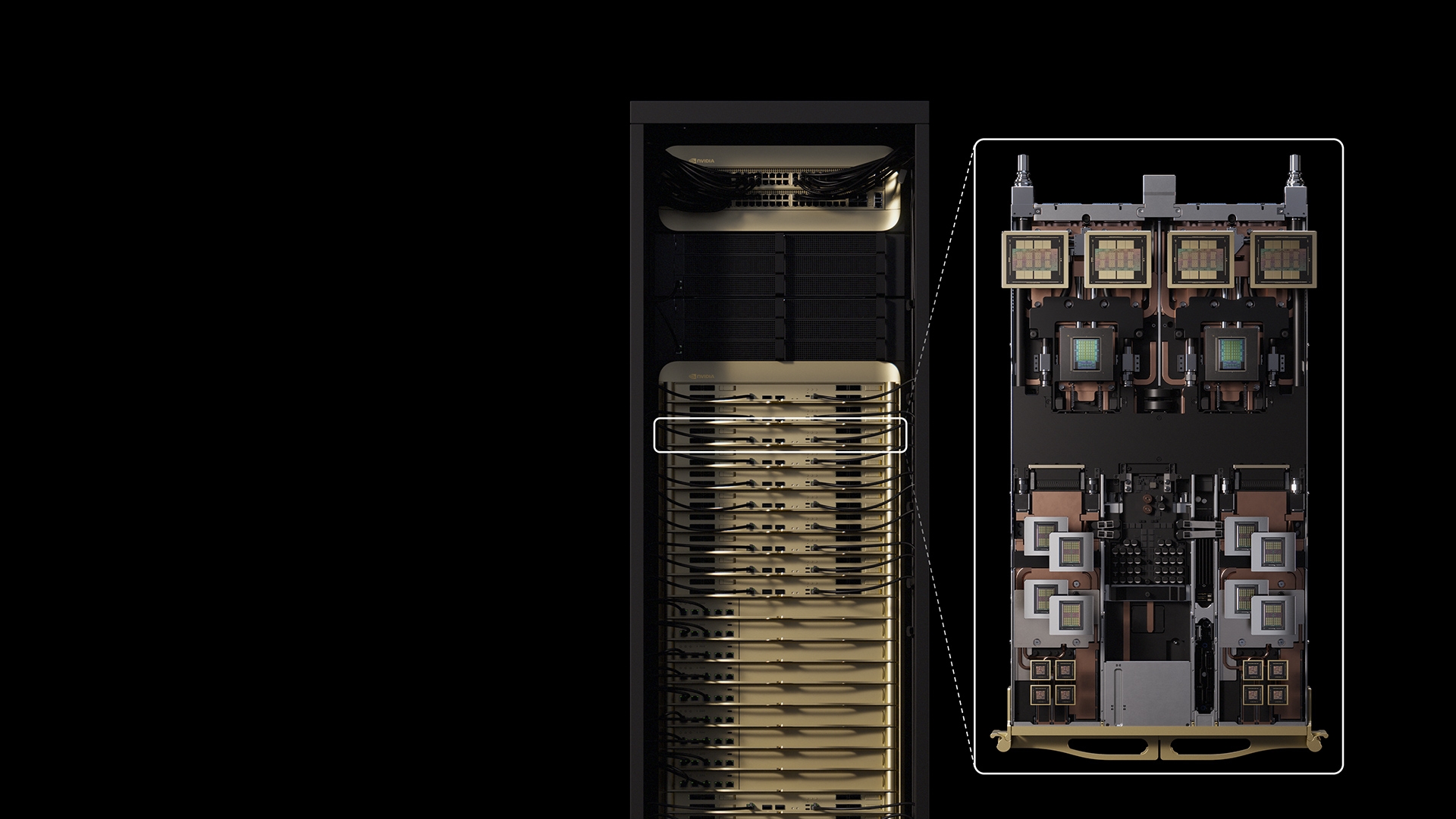

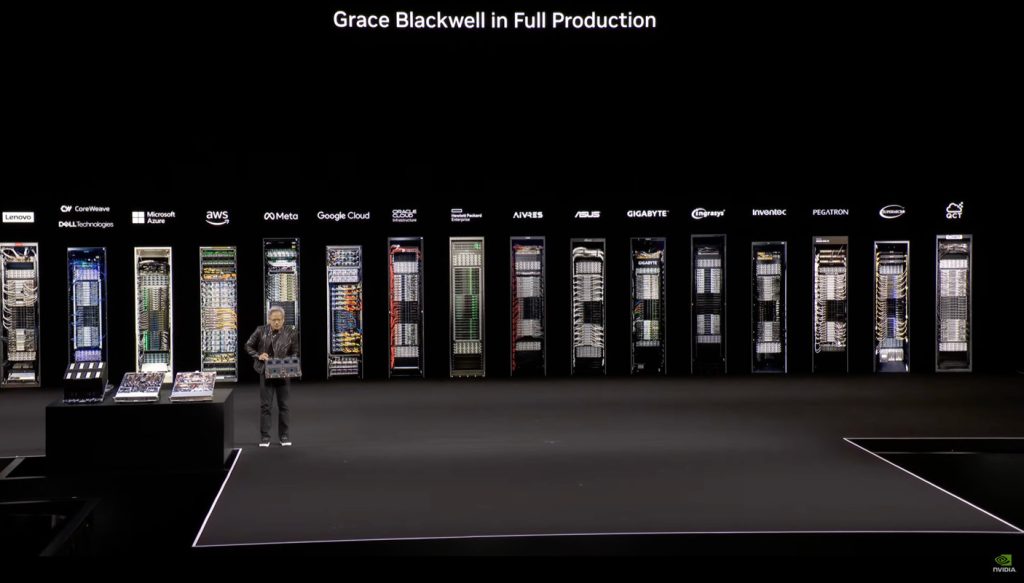

One of the most important announcements wasn't the performance numbers—it was the statement that Rubin is already in full production. Jensen Huang didn't say "coming soon" or "planned for later this year." He said Rubin is actively being manufactured right now.

This matters because in the semiconductor industry, there's always a gap between announcement and availability. With Blackwell, that gap was significant—it was announced but then supply was constrained for months. With Rubin, the company seems to have learned that lesson. They're not announcing without being ready to deliver.

The ramp-up is expected to accelerate in the second half of 2026. This means systems are already being built and tested, just not yet shipping to customers in massive volumes. But by mid-2026, expect to see Rubin-based systems becoming available in cloud providers and supercomputers.

Already, major institutions are lining up. HPE's Blue Lion supercomputer will be Rubin-based. Lawrence Berkeley National Lab's Doudna supercomputer will be Rubin-based. These are significant commitments from major players, which signals confidence in the architecture.

Estimated data shows that by adopting Rubin, companies could see a 20-40% reduction in infrastructure costs and up to 5x performance improvement by 2029.

Enterprise Adoption: Who's Actually Using This

The real story of Rubin isn't in the technical specifications—it's in who's adopting it and why.

Open AI needs Rubin. As they scale from GPT-4 to newer generations, their compute requirements keep exploding. Every improvement in efficiency and performance directly translates to faster research iteration and faster model improvement. Open AI has been one of Nvidia's most important partners, and that relationship continues with Rubin.

Anthropic, which makes Claude, is also planning Rubin adoption. The same calculus applies—better compute efficiency means faster research, better models, and lower operational costs. For a company competing with Open AI, every architectural advantage matters.

Amazon Web Services (AWS) is integrating Rubin into their infrastructure. AWS doesn't just use Nvidia chips—they design custom systems around them. The fact that they're planning major Rubin integration suggests they see genuine advantages for their customers. AWS customers will eventually be able to use Rubin-based instances, which will offer better performance and lower costs compared to Blackwell-based instances.

The supercomputer angle is equally important. Lawrence Berkeley's Doudna supercomputer will be one of the world's fastest machines, built entirely around Rubin. That's not a small thing—that tells you the world's top research institutions trust Rubin enough to build their next-generation systems around it.

These aren't hypothetical partnerships. These are actual institutional commitments. Companies don't change their infrastructure strategy lightly, especially when it involves billions of dollars and multi-year commitments.

Storage Architecture: The Real Innovation

While the GPU performance improvements are impressive, the real architectural innovation is in storage. Rubin introduces a new tier between high-speed GPU memory and main system memory.

Traditionally, you have two tiers: GPU VRAM (very fast, expensive, limited capacity) and main memory (slower, cheaper, more capacity). If your working set doesn't fit in VRAM, you spill to main memory, and everything slows down. This is terrible for KV cache problems because the cache is often larger than VRAM.

Rubin adds a middle ground: a new storage tier that's connected externally to the compute device but still much faster than main memory. It's optimized for the specific access patterns that KV cache systems need. It's not as fast as GPU VRAM, but it's fast enough. It's not as slow as main memory. It's the Goldilocks zone.

This might sound like a minor technical detail, but it's huge for practical AI systems. It means you can build data center configurations that are much more efficient. You don't need to over-provision GPUs just to handle memory requirements. You don't need to constrain your model's context window just to fit everything in VRAM. You can actually match your infrastructure to your workload efficiently.

The Interconnection Story: NVLink Evolution

The improved NVLink is the other critical infrastructure piece. When you're building a supercomputer with hundreds or thousands of GPUs, they need to communicate with each other incredibly fast.

Previous NVLink versions already provided impressive bandwidth—enough to move data between GPUs much faster than alternatives. But there's always room for improvement. Better interconnection means less waiting, more efficient all-reduce operations (critical for distributed training), and overall higher system efficiency.

The specific improvements in Rubin's NVLink implementation aren't as well-documented as the GPU performance numbers, but the general principle is clear: as GPU compute power increases, interconnection bandwidth needs to increase too, or the GPUs become bottlenecked waiting for data. Rubin scales the interconnect appropriately.

This is the kind of thing that's invisible to end users but absolutely critical for data center operators. A data center architect building a new supercomputer will evaluate interconnection bandwidth carefully, because it determines how efficiently they can use all those GPUs.

Nvidia's Rubin architecture shows substantial improvements over Blackwell: 3.5x faster in model training, 5x in inference tasks, 50 petaflops of compute power, and 8x more inference compute per watt. Estimated data based on internal benchmarks.

Power Efficiency: The Economics of AI Infrastructure

The 8x improvement in inference compute per watt is arguably the most important metric from a practical business perspective.

Data centers consume enormous amounts of power. A single large AI data center can consume 100+ megawatts of electricity. That's comparable to a small city. The electricity bill for that data center is millions of dollars per month. Power consumption directly impacts:

- Operating costs: Every watt consumed is a cost that goes straight to the utility bill

- Capital costs: More power consumption requires more cooling infrastructure, more electrical infrastructure, more backup generators

- Environmental impact: Every watt is electricity that has to be generated somewhere, with associated carbon emissions

- Geographical constraints: Some locations simply don't have enough electrical capacity for massive data centers

- Sustainability goals: Major cloud providers have committed to carbon neutrality, and power consumption is a big part of that

When Nvidia delivers 8x better power efficiency, they're not just making systems faster. They're making them more economically viable, more environmentally responsible, and more deployable globally. A data center that would have required 100 megawatts with previous architecture might now require only 12.5 megawatts with Rubin.

At electricity rates of roughly

The Vera CPU: Why Agentic AI Needs Different Hardware

Here's something most people miss: the addition of a dedicated Vera CPU in Rubin. This isn't just cosmetic. It represents a fundamental acknowledgment that AI workloads are changing.

For the past decade, the focus has been on GPU performance. Larger models, faster training, better inference. But agentic AI—where an AI system takes actions, observes results, reasons about them, and adjusts—has different requirements.

When an AI agent is reasoning and making decisions, it doesn't need massive matrix multiplication throughput (that's what GPUs do). It needs fast, responsive CPU performance for control flow. It needs good branch prediction and quick context switching between different reasoning tasks.

A traditional GPU is actually terrible at these tasks. GPUs excel at throughput, not latency. They're optimized for doing millions of the same operation in parallel, not for fast, complex decision-making.

By including a dedicated CPU, Rubin acknowledges that the future of AI isn't just about running bigger models through bigger matrices. It's about building systems that reason, decide, act, and learn. Those systems need a CPU that's good at that. Historically, data centers would use generic server CPUs for this. But a Vera CPU specifically optimized for agentic workloads will do it better.

This might seem like a small detail, but it signals a shift in how the industry thinks about AI infrastructure. It's not just "bigger GPU is better." It's "match the hardware to the workload."

Comparison to Predecessors: How Rubin Stacks Against Blackwell, Hopper, and Lovelace

Understanding Rubin requires understanding its predecessors and what each generation solved.

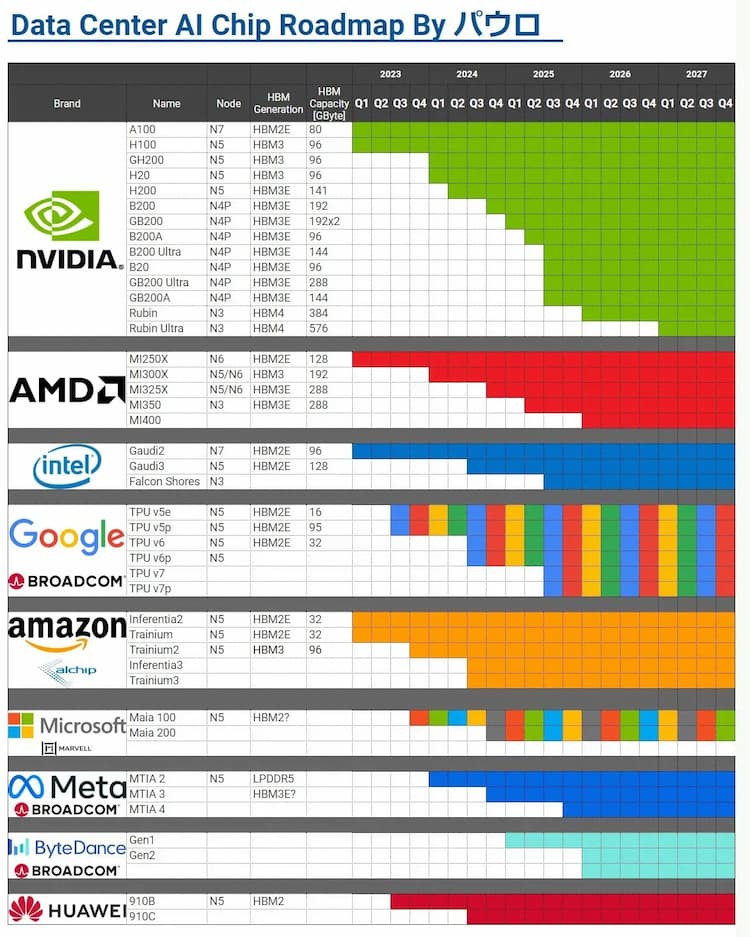

Lovelace (released 2022) was the first Nvidia architecture optimized for transformer-based AI. It introduced significant improvements in tensor operations and memory bandwidth. But it hit early limitations with large-scale model training—models were getting bigger faster than Lovelace could keep up.

Hopper (released 2023) solved some of those limitations. It added transformer-engine hardware for more efficient mixed-precision training, improved memory systems, and better interconnects. Hopper became the default for AI labs building large language models. But as models got even bigger and inference workloads exploded, Hopper started showing bottlenecks.

Blackwell (released 2024) was supposed to be the breakthrough. It offered 2-3x performance improvements over Hopper, which was significant. But Blackwell was also the first architecture where the gap between theoretical performance and practical, achievable performance became apparent. Supply constraints meant early customers couldn't get as many Blackwell GPUs as they wanted. Also, Blackwell was already showing signs that the old approach—just making the GPU bigger and faster—had limits.

Rubin (2026) represents a different philosophy. Instead of just cranking up GPU performance, Rubin thinks about the entire system. It adds dedicated components for storage, CPU, networking. It optimizes for specific workloads rather than trying to be everything to everyone. The performance improvements over Blackwell (3.5x training, 5x inference) are significant, but arguably more important is the architectural approach—addressing fundamental bottlenecks rather than just adding more raw compute.

This progression shows Nvidia's evolution in thinking about AI infrastructure. The company has moved from "GPU performance is everything" to "system efficiency is everything."

Nvidia's 8x power efficiency improvement reduces power consumption from 100 MW to 12.5 MW, saving approximately $7 million annually in electricity costs (Estimated data).

Market Impact: What This Means for the AI Infrastructure Industry

Rubin doesn't exist in isolation. It affects the entire ecosystem of AI infrastructure.

For cloud providers like Google Cloud, and Azure, Rubin means they can offer better-performing instances at lower costs. This improves their competitive position and makes AI services more accessible to customers. The improved power efficiency is particularly important because it reduces their infrastructure costs, which they can pass on to customers.

For AI labs like Open AI, Anthropic, and others, Rubin means their research iteration cycles can accelerate. Faster training means they can experiment more. Better inference performance means they can deploy models to more users with the same infrastructure. Lower power costs means their operational budgets go further.

For startups building AI applications, Rubin means the barrier to entry drops. If AI inference costs drop significantly due to better efficiency, more startups can afford to build AI-powered products. This democratizes AI infrastructure to some extent.

For enterprises deploying AI internally, Rubin means they can build more efficient systems. The improved performance per watt is particularly important for companies with limited data center capacity or power budgets.

The competitive landscape also shifts. Nvidia's main competitors in AI hardware—AMD (with their MI-series), Intel (with Gaudi), and others—will need to respond. AMD's next-generation chips need to narrow the gap with Rubin or fall further behind. This competition is healthy and will drive innovation across the industry.

Long-Context and Multimodal: The Workloads That Benefit Most

Not every AI workload benefits equally from Rubin. Some workloads see massive improvements, others see moderate improvements.

Long-context workloads benefit enormously. Any use case involving 100K+ token contexts—which includes document processing, code analysis, multi-book analysis—sees dramatic improvements from Rubin's storage architecture. The KV cache no longer becomes the limiting factor.

Multimodal workloads (text + image + video processing together) also benefit significantly. These workloads are memory-intensive and compute-intensive simultaneously. Rubin's balanced approach to compute and memory bandwidth makes it well-suited.

Real-time inference workloads (chatbots, voice assistants, recommendation systems) benefit from the 5x inference improvement. Lower latency means better user experience. For every millisecond of latency saved, the perceived quality improves.

Training large models still benefits, with 3.5x improvement. But training workloads are already optimized in many ways, and the improvements are somewhat incremental compared to inference improvements.

Small, efficient models might not see proportional improvements. If you're running a small quantized model on consumer GPUs, Rubin's advances might not matter. Rubin is built for scale, not for efficiency at the edge.

The Carbon Question: Is More Compute Actually More Efficient?

Here's a tricky question: Rubin lets us do more AI compute faster and with better power efficiency. But we're still talking about massive amounts of electricity consumption. Is this actually good for the environment?

The honest answer is complicated. On a per-operation basis, Rubin is 8x more efficient, which is genuinely better for the environment. But AI infrastructure spending is projected to reach trillions of dollars, which likely means absolute electricity consumption will continue growing despite efficiency improvements.

It's the rebound effect: when something becomes more efficient, people use more of it. Efficient AI infrastructure means more companies will deploy AI, more AI models will be built, more inference will happen. The efficiency gains might be completely offset by the increase in usage.

That said, efficiency is still important. We should absolutely build efficient AI infrastructure. The alternative—inefficient infrastructure—would be worse. And there's genuine research momentum on AI efficiency improvements beyond just hardware, including techniques like quantization, distillation, and pruning that can make AI models more efficient.

But Rubin should be understood for what it is: it's a significant efficiency improvement for AI computing, which is genuinely valuable. But it's not a silver bullet for the environmental impact of AI. The real solution requires continued improvements across many dimensions.

AI infrastructure spending is projected to grow significantly, potentially reaching

Availability and Pricing: When Can You Actually Use Rubin?

This is where things get practical. Cool architecture doesn't matter if you can't get it. Impressive specs don't matter if it's prohibitively expensive.

For availability: Rubin is in full production now (early 2026), with ramp-up expected in H2 2026. If you're a cloud provider like AWS, you can probably start integrating Rubin systems now and offering them to customers mid-2026. If you're a researcher at a major institution, you might get access to a Rubin-based supercomputer in 2026. If you're a regular startup, you might not get access to Rubin-specific infrastructure until 2027 or later, once cloud providers build it into their standard offerings.

For pricing: Nvidia doesn't publicly disclose GPU pricing—that's negotiated per customer. But based on historical patterns, Rubin GPUs will probably be priced similar to high-end Blackwell GPUs, maybe 10-20% more if Nvidia thinks customers are willing to pay for the improvements. For enterprise customers, that likely means Rubin instances cost maybe 5-15% more than Blackwell instances on cloud providers, but offer significantly better performance per dollar when you account for the performance improvements.

For cloud provider pricing: AWS, Google Cloud, and Azure will eventually offer Rubin-based instances. Current AI instance prices on AWS range from

The practical timeline: if you're planning AI infrastructure in 2026, start requesting Rubin availability from your cloud provider. If they don't have a timeline, keep asking. Most enterprises and startups will transition to Rubin by 2027 for new workloads.

Looking Forward: What Comes After Rubin?

There's always a next generation. Nvidia has already announced that Rubin will be followed by other architectures (codenamed Hyperion and beyond), continuing the tradition of naming architectures after famous scientists.

Based on historical patterns and current trends, we can expect:

Improved memory systems: The storage tier in Rubin works well, but it's still constrained by physics. Future architectures will likely have even more sophisticated memory hierarchies, possibly with optical connections or other exotic technologies.

Better CPU integration: The Vera CPU in Rubin is a start, but agentic AI workloads might demand even more sophisticated CPU components in future architectures. We might see heterogeneous computing taken even further.

Improved power efficiency: The 8x improvement from Blackwell to Rubin is huge, but it won't last forever. We'll hit physical limits eventually. Future architectures will need new techniques—possibly photonic computing, analog computing for specific workloads, or quantum computing for specific problems.

Specialized processors: While Rubin is generalist (handles training, inference, agentic), future might go more specialized. You might buy a Rubin-based system specifically for training, a different system specifically for inference, etc.

Competing architectures: AMD, Intel, and others won't rest. They'll continue improving their architectures. AMD's MI series is competitive, and as these companies mature their AI offerings, the competitive landscape might change.

The broader pattern is clear: AI infrastructure is becoming more sophisticated, more specialized, and more carefully engineered. The days of "bigger GPU is better" are ending. The era of "right hardware for the right workload" is beginning.

Implementation Strategies: How Organizations Should Think About Rubin

If you're a decision-maker at a company that uses significant AI infrastructure, how should you think about Rubin?

Short term (2026): Start testing Rubin when it becomes available through your cloud provider. Compare performance and costs to your current Blackwell-based infrastructure. For many workloads, you'll see 20-40% reduction in infrastructure costs due to better efficiency, even if Rubin instances cost slightly more per unit.

Medium term (2026-2027): Plan to migrate inference workloads to Rubin. Inference is where the 5x performance improvement is most impactful. Consider retraining models on Rubin infrastructure if you're doing any training, but don't feel pressured—retraining is a smaller priority than inference optimization.

Long term (2027+): As Rubin becomes standard, you'll probably stop thinking about it as special. It'll just be the hardware you use, like Blackwell is now.

Key principle: don't assume the performance improvements apply equally to all workloads. Benchmark your specific workloads on Rubin. Some applications might see 5x improvement, others might see 2x. Use actual performance data for your specific use cases, not aggregate numbers.

Competitive Landscape: Where Do AMD, Intel, and Others Stand?

Nvidia's dominance in AI infrastructure is substantial. But it's not absolute, and competition is intensifying.

AMD's MI300 and MI325 are competitive offerings. They're not quite at Nvidia's level in terms of performance-per-watt or ecosystem maturity, but they're improving rapidly. For some workloads, AMD might be cheaper, and for customers concerned about vendor lock-in, AMD is a viable alternative.

Intel's Gaudi is further behind but improving. Intel has the advantage of deep pockets and x 86 expertise, but they're starting from a less mature position in AI accelerators.

Custom silicon from cloud providers (Google's TPUs, Amazon's Trainium/Inferentia) serve specific workloads well. These are cost-effective for those specific uses but less general-purpose than Nvidia.

Startups like Graphcore (now acquired), Samba Nova, and others are developing specialized architectures. Most have struggled to compete with Nvidia's combination of performance and ecosystem, but a few might find niches.

Nvidia's advantages are:

- CUDA ecosystem: Decades of software optimization for Nvidia hardware

- Performance: Rubin genuinely is faster and more efficient

- Partnership momentum: Major AI labs, cloud providers, and enterprises are all standardized on Nvidia

Nvidia's risks are:

- Specialization: As workloads become more specialized, general-purpose GPUs might become less attractive

- Regulatory pressure: U. S. export controls limit Nvidia's sales to China, reducing addressable market

- Cost: As AI infrastructure becomes more competitive, cheaper alternatives become more attractive

For most organizations, Nvidia dominance in AI infrastructure will continue for at least 2-3 years. But competition will intensify, and niches will open up for competitors.

Integration with Automation and Developer Tools

As AI infrastructure becomes more sophisticated, integration with developer tools and automation platforms becomes increasingly important. Runable represents the kind of platform where Rubin's capabilities can be efficiently leveraged. For teams building AI applications or infrastructure-as-code solutions, being able to automate deployment, testing, and optimization on Rubin-based infrastructure through tools like Runable makes a significant difference. The faster your infrastructure, the faster your iteration cycle—and automation platforms let you exploit that speed advantage fully.

Developers working with Rubin-based systems will need robust tooling for:

- Infrastructure provisioning: Spinning up Rubin systems quickly and efficiently

- Monitoring and optimization: Understanding how your workloads are using the hardware

- Model deployment: Getting models onto Rubin systems reliably

- Performance analysis: Identifying bottlenecks in your AI pipeline

Use Case: Automate the deployment of AI models to Rubin infrastructure, generating deployment documentation and configuration files automatically.

Try Runable For FreeAutomatic deployment generation, configuration management, and infrastructure documentation become valuable when you're managing Rubin systems at scale. The architecture's complexity means good automation tools aren't optional—they're necessary for operational efficiency.

FAQ

What is the Nvidia Rubin chip architecture?

Rubin is Nvidia's latest AI computing architecture released in early 2026, named after astronomer Vera Florence Cooper Rubin. Unlike previous single-GPU designs, Rubin is a six-chip ecosystem comprising a GPU, CPU, storage components, and networking processors all optimized to work together. The architecture delivers 3.5x faster training and 5x faster inference compared to the previous Blackwell generation, while offering 8x better power efficiency for inference workloads.

How does Rubin compare to Blackwell?

Rubin significantly outperforms Blackwell in nearly every dimension. Training workloads run 3.5x faster, inference runs 5x faster, and power efficiency for inference is 8x better. Beyond raw performance, Rubin introduces architectural innovations including a dedicated storage tier optimized for KV cache management, a specialized CPU for agentic reasoning, and improved interconnection systems. These differences make Rubin more practical for modern AI workloads rather than just theoretically faster.

When will Rubin be available for general use?

Rubin entered full production in early 2026 with expected ramp-up in the second half of 2026. Major cloud providers including AWS, Google Cloud, and Azure will offer Rubin-based instances, likely becoming available to general users between mid-2026 and early 2027. Early adoption will be from large enterprises, research institutions, and AI labs. Startup and small business access will come later as cloud providers standardize their offerings.

What workloads benefit most from Rubin?

Rubin excels with long-context AI applications (processing documents with 100K+ tokens), multimodal workloads combining text and images, and real-time inference applications. The new storage tier specifically addresses KV cache bottlenecks that plague long-context models. Agentic AI workloads benefit from the dedicated Vera CPU. Training new models benefits from the 3.5x improvement, though established large-scale training infrastructure might take time to migrate.

Why does Rubin have separate storage architecture?

The new storage tier sits between GPU memory (fast but limited) and main system memory (large but slow), creating an optimal zone for KV cache requirements in modern AI systems. As context windows expanded to 100K+ tokens and concurrent user counts increased, KV cache became a major bottleneck. Rubin's storage tier eliminates this constraint without requiring excessive GPU memory, making long-context models practical at scale and improving overall system efficiency significantly.

How much will Rubin infrastructure cost?

Nvidia doesn't publicly disclose GPU pricing, which is negotiated per customer and volume. Based on historical patterns, Rubin GPUs will be priced comparably to high-end Blackwell GPUs. Cloud providers will likely price Rubin instances similarly to current AI instances (ranging from

Will Rubin require retraining my existing models?

No, Rubin can run existing models trained on older architectures (Hopper, Blackwell, etc.) without modification. Models will automatically benefit from Rubin's performance improvements without retraining. However, if you're training new models from scratch, training on Rubin infrastructure from the start lets you take full advantage of the architecture's capabilities and optimize hyperparameters specifically for Rubin's characteristics.

What makes Rubin different from just a faster GPU?

Rubin isn't simply a faster GPU—it's a complete system redesign. By including specialized components (CPU, storage tier, networking), Rubin addresses specific bottlenecks that a faster GPU alone can't solve. The architecture recognizes that AI workloads have diverse requirements: compute throughput, memory bandwidth, fast decision-making, and low-latency interconnection. Rather than optimizing for one metric, Rubin balances multiple performance axes.

How does Rubin support agentic AI?

The dedicated Vera CPU in Rubin is specifically designed for agentic reasoning workloads. While GPUs excel at matrix multiplication throughput, CPUs are better for control flow and rapid decision-making that agentic systems require. The Vera CPU handles the reasoning, decision logic, and orchestration components of agentic AI systems while the GPU handles the neural network computations, creating an efficient division of labor.

What about power consumption and environmental impact?

Rubin delivers 8x better power efficiency for inference compared to Blackwell, meaning significantly lower electricity consumption for the same computational work. However, improved efficiency typically leads to increased usage (rebound effect), so absolute power consumption across data centers might still grow. True environmental progress requires combining hardware efficiency improvements with software optimizations like model quantization and distillation, plus sustainable energy sourcing for data centers.

Will Rubin become the standard for AI infrastructure?

Rubin will likely become the default choice for new AI infrastructure deployments throughout 2026-2027. Existing Blackwell and Hopper systems will continue running, but organizations planning new projects will standardize on Rubin due to superior performance and efficiency. The transition won't be instantaneous—large existing systems take time to migrate—but within 2-3 years, Rubin-based infrastructure will be the dominant choice for most applications.

Conclusion: The Future of AI Infrastructure Is Here

Nvidia's Rubin architecture represents more than just an incremental performance improvement. It's a philosophical shift in how to build AI infrastructure. Instead of endlessly chasing bigger, faster GPUs, Rubin recognizes that modern AI workloads have diverse, sophisticated requirements that demand a thoughtfully designed ecosystem.

The 3.5x training improvement and 5x inference improvement are impressive, but they're not the real story. The real story is that Rubin solves specific, concrete problems that have been plaguing data center operators and AI teams. The KV cache bottleneck that constrains long-context models? Solved. The power consumption that's making data center expansion difficult? Dramatically improved. The agentic AI workloads that don't fit traditional GPU acceleration? Now accommodated.

For organizations building AI infrastructure, Rubin is not optional anymore. It's the standard you'll be compared against. Cloud providers will offer Rubin instances. Competitors will be evaluated based on Rubin performance. New projects will be architected for Rubin from the start.

The practical implications are significant. If you're responsible for AI infrastructure decisions, you should be planning your Rubin transition now. If you're a developer building AI applications, you should be understanding how Rubin will affect your deployment options and costs. If you're a founder building an AI company, Rubin's improved efficiency affects your unit economics directly.

And for the broader AI industry, Rubin signals that we're moving from a era of raw compute scaling to an era of sophisticated, specialized infrastructure. The era where "bigger GPU is better" is ending. The era where "right architecture for the right workload" is beginning.

That shift has profound implications for where AI development happens, who can afford to build AI systems, and what kinds of AI applications become economically viable. Rubin won't immediately transform the world. But it's a significant step on that path. And in the fast-moving world of AI infrastructure, significant steps happen frequently. The question isn't whether you should pay attention to Rubin. The question is whether you can afford not to.

Use Case: Generate AI-powered documentation for your Rubin infrastructure deployment, automatically creating deployment guides and architecture documentation from your infrastructure code.

Try Runable For FreeKey Takeaways

- Rubin is a six-chip architecture ecosystem, not a single GPU, addressing compute, memory, storage, networking, and reasoning workloads

- Performance improvements are massive: 3.5x faster training, 5x faster inference, 8x better power efficiency per watt

- The new storage tier between GPU VRAM and main memory solves the KV cache bottleneck plaguing long-context AI models

- Already in production with expected ramp-up in H2 2026 through AWS, Google Cloud, Azure, and major supercomputers

- Architectural innovation matters more than raw compute—Rubin addresses specific bottlenecks rather than just scaling performance

Related Articles

- Photonic AI Chips: How Optical Computing Could Transform AI [2025]

- Airloom's Vertical Axis Wind Turbines for Data Centers [2025]

- NVIDIA CES 2026 Keynote: Live Watch Guide & AI Announcements

- AI Predictions 2026: What's Next for ChatGPT, Gemini & You [2025]

- AI's Impact on Enterprise Labor in 2026: What Investors Are Predicting [2025]

- AI Budget Is the Only Growth Lever Left for SaaS in 2026 [2025]

![Nvidia Rubin Chip Architecture: The Next AI Computing Frontier [2025]](https://tryrunable.com/blog/nvidia-rubin-chip-architecture-the-next-ai-computing-frontie/image-1-1767652844440.jpg)